Abstract

Aging can lead to immunosenescence, which dramatically impairs the hosts’ ability to develop protective immune responses to vaccine antigens. Reasons for this are not well understood. This topic’s importance is reflected in the increases in morbidity and mortality due to infectious diseases among elderly persons, a population growing in size globally, and the significantly lower adaptive immune responses generated to vaccines in this population. Here, we endeavor to summarize the existing data on the genetic and immunologic correlates of immunosenescence with respect to vaccine response. We cover how the application of systems biology can advance our understanding of vaccine immunosenescence, with a view toward how such information could lead to strategies to overcome the lower immunogenicity of vaccines in the elderly.

Introduction

The cellular, genetic, and other aspects of aging result in a phenomenon known as “immunosenescence.” While immunosenescence has protean effects on the health of the organism, it can particularly impair the host’s ability to defend itself against microbial invasion by pathogens such as bacteria and viruses. This results from defects in innate and adaptive humoral and cellular immunity (see Figure 1). Such defects in immune response are readily apparent in humoral and cellular responses to vaccine antigens. Here, we will provide an overview of genetic variation in aging and evidence for impaired immune responses to common vaccines. We highlight how researchers are approaching a deeper understanding of immunosenescence and vaccine response from a systems biology point of view.

Figure 1.

Immunologic Changes Due to Immunosenescence

Systems biology and immunological response

Complex biological processes such as the immune response, or aging, are not the result of isolated events, single proteins, chemicals, enzymes, or even individual cell types; rather, they are the coordinated result of interacting cell types, tissues, alterations in gene regulation and expression, signaling pathways, and biological networks. It is the combined, synergistic effect of the individual parts that leads to immunity, aging, and immunosenescence. Although reductionist approaches have delivered valuable information regarding individual components (proteins, genes, single pathways, metabolites), a fundamental understanding of the whole picture will require a comprehensive examination of all the respective pieces of the puzzle.

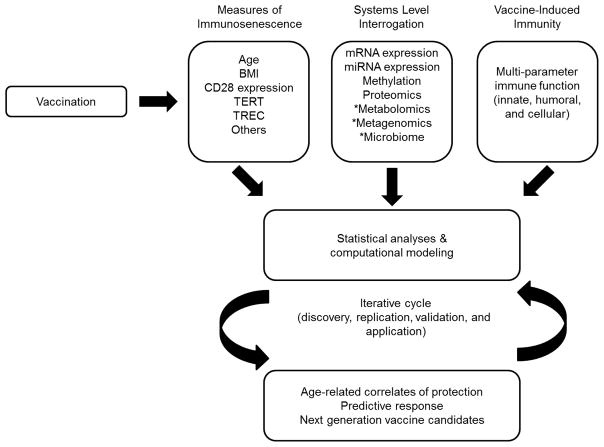

Systems biology seeks to characterize, in a comprehensive or high-throughput manner, the behavior of each part of a biological system. It applies computational models to the data to predict and/or influence the system’s behavior. As applied to immunology and vaccine response, it aims to define the mechanisms leading to immunity, and predict the resulting immune response after vaccination [1,2]. This can also be applied to immune alterations in the elderly (see Figure 2). Multiple groups have applied elements of systems biology, advanced bioinformatics, computer algorithms, and high dimensional assays to probe immune function and labeled their approaches as vaccinomics [3], systems vaccinology [2], systems immunogenetics [4], vaccine informatics/computational immunology [5,6], and reverse vaccinology [7,8]. Common to each approach is the application of appropriate tools (biological and computational) toward the understanding of immune function at a systems level. These studies revealed unexpected insights into the development of immune responses to vaccines. Querec et al. used a systems biology approach to discover that expression of the complement C1qB protein and the eukaryotic translation initiation factor 2 alpha were highly predictive of CD8+ T cell responses to yellow fever vaccine [9]. The same study identified a different signature, involving TNFRS17, which predicted neutralizing antibody responses to the same vaccine. Another group applied a gene-set enrichment analysis to influenza vaccine recipients and identified a set of genes involved in B cell proliferation and immunoglobulin production, which predicted influenza vaccine responses with 88% accuracy. One group integrated genome-wide polymorphism analysis and eQTL to identify genes involved in antigen expression and intracellular trafficking as important determinants of influenza vaccine immunogenicity [10,11]. Other groups have used blood transcriptome analysis to identify an IFN-inducing gene signature associated with tuberculosis disease susceptibility[12]. This neutrophil-driven IFN signature correlated with pulmonary disease and vanished with successful treatment. Systems biology approaches have greatly enhanced our understanding of tuberculosis infection and immunity, and may provide biomarkers for diagnosis and treatment of tuberculosis infections as well as the development of new vaccines [12,13]. Systems immunology approaches have allowed us to identify important differences in innate and adaptive immune responses to different vaccines. For example, innate responses after pneumococcal vaccine administration are dominated by an inflammatory response detectable ~7 hours after vaccination, while influenza vaccine induces a delayed (15-hour) IFN response [14]. Both vaccines elicit a Day 7 plasmablast response (defined by: gene expression [CD38, TNFRSF17]; elevated pathogen-specific serum Ab; and increases in circulating plasmablasts). Elements of this plasmablast signature have also been seen with yellow fever vaccine, perhaps indicating a key pathway activated by multiple viral vaccines. Many of these approaches are being employed with malaria and HIV vaccines in the early stages of research and development [15–18]. Variations of these approaches can be applied toward understanding, predicting, and eventually overcoming immunosenescence.

Figure 2.

The Incorporation of Immunosenescence Markers into a Predictive Vaccine Response and Systems Biology Model. There is a diminished immune response to vaccines in the elderly. Specific factors that have been shown to be associated with this response (for example: chronological age, body mass index (BMI), CD28 expression on CD8 T-cells; telomerase reverse transcriptase (TERT); and T-cell receptor excisions circles (TREC)). Current systems biology approaches focus on incorporating these immunosenescence markers into a predictive vaccine response model in hopes of better understanding the complex intricacies of the aging immune system. [1] *Novel insights will be gained by new research approaches aimed at studying metabolomics, metagenomics, and the host microbiome.

The immunogenetics of aging and vaccine response offer insight into the effect of aging on the immune system, and offer possibilities for identifying and repairing or overcoming such defects through systems biology approaches in an attempt to induce protective immune responses to pathogens that threaten health and well-being of a large segment of the population.

Genetic Variation and Aging

Immunosenescence is generally defined as age-related changes to the immune system that result in increased susceptibility to infectious diseases and a decreased response to vaccination [19]. The identification of genetic determinants of immunosenescence could transform aging research, including vaccine and adjuvant development in the elderly, and development of novel approaches to overcoming aging defects [20]. Although immunosenescence can be attributed to many factors, recent data have demonstrated that there is host genetic variation related to aging. In a study of 423 healthy Icelandic individuals (17 to 89 years of age), an age-associated decrease in the frequency of the C4B*Q0 allele of the complement C4B gene was found to be associated with a negative effect on health or survival in subjects with coronary artery disease [21]. Several studies reported the relationship between polymorphisms of adipokine genes and age-associated diseases [22,23]. In a study of 110 elderly subjects (>85 years old), genetic variation in the adiponectin (SNP rs1501299) and leptin (SNP rs7799039) genes is linked to the gender-specific longevity phenotype [24]. A protective role of the longevity-associated D2S1338-18 allele established in a comparison between deceased and living populations is also suggested [25], which indicates genetic polymorphisms may play a role in immunosenescence-related phenotypes.

Antiviral immunity against pathogens, including influenza virus, is greatly reduced in the elderly. A heritable contribution to predisposition to a fatal outcome from influenza infection has been proposed [26,27]. One important gene for the anti-inflammatory response to influenza virus infection is the heme oxygenase-1 gene (HO-1) [28]. A decline in antibody production after influenza vaccination has been linked to the HO-1 and HO-2 gene polymorphisms [29]. Decreased antibody production in response to influenza vaccine was observed in an aged HO-1-deficient mouse model, suggesting that HO gene expression is an important element of the impaired age-related response to influenza vaccine [29].

There is evidence that age-related modifications in gene expression may play a role in the physiological changes detected with aging. To understand how transcriptomic changes may contribute to the aging process, total RNA transcripts in peripheral blood mononuclear cells were compared between healthy young (25 to 48 years of age) and old (75 to 103 years of age) individuals [30]. Of the 148 transcripts proposed to be involved in immunosenescence and stress reaction, 16 transcripts mainly related to modification of immune function (e.g., CD28, CD69, LCK, CD86, cathepsins, etc.) were differentially expressed in old subjects, suggesting that these transcriptomic biomarkers may be biomarkers of aging [30]. A recent report by Harries et al. suggested that human aging is associated with a few changes in individual gene expression (i.e., deregulation of mRNA processing pathways) [31]. Many studies have used epigenome-wide DNA methylation analysis for measurement of the methylation status at CpG sites (dinucleotides) and found multiple CpG sites associated with DNA methylation and aging [32,33]. Understanding the effect of age on DNA methylation (histone modifications and changes to chromatin structure) could improve our knowledge of the role of epigenetic variations in the process of human aging.

Preliminary data from peripheral blood mononuclear cell (PBMC) miRNAs indicate down-regulation of miR-590-5p expression three days after influenza vaccination in subjects 50–74 years old (p<0.0006) (Kennedy RB, unpublished data). In humans, miR-590-5p was found to target the expression of mRNAs involved in the transforming growth factor, beta receptor II (TGFBR2) pathway, and is predicted to affect both MED21 and SATB1 genes (which are, respectively: a transcription activator regulating expression of RNA polymerase II genes; and a transcriptional repressor, which controls gene expression through chromatin remodeling and affects IL-2, IL2RA, and Ig genes in T and B cells) (Kennedy RB, unpublished data). In addition to the findings associated with miRNAs, it has been shown that mitochondrial DNA damage, such as mtDNA deletions and point mutations, may also accumulate in human CD4+ T lymphocytes with age and may play a role in T cell aging and immunosenescence [34]. Such studies are beginning to elucidate molecular mechanisms behind immunosenescence in the elderly.

Immunosenescence and vaccine response

The complex nature of immunosenescence makes it a difficult measure to quantify. Vaccination of older adults against influenza, hepatitis, or pneumococcal disease does not induce the same level of protective immunity as that observed in a comparable, but younger, population [35–40]. To our knowledge, a definitive explanation for this has not been reported. Most studies have focused on single forms of immunosenescent-related deficiencies in vaccine response. We provide a brief summary of results from studies on age-related changes to immunity after vaccination (see Table 1). These examples highlight very specific perturbations. It is important to acknowledge that all of these—as well as yet-to-be discovered—immunosenescent factors influence immune responses in older adults.

Table 1.

Examples of age-related factors influencing vaccine response

| Innate Immunity | Adaptive Immunity | |

|---|---|---|

| Influenza Vaccine ↓ Antibody response |

↓ CD80 expression ↓ TLR-induced secretion of the inflammatory cytokines in DCs ↑ IL-10 levels * Age-related changes to gene modules involved in apoptosis |

↑ CD8+CD28null cells ↓ Plasmablasts and PPAbs |

| ↓ Cellular response | ↓ Influenza-specific CD4+ memory T-cells ↓ CD8+ T-cell cytolytic properties |

|

| Hepatitis Vaccine ↓ Cellular response |

↓ CD62L-associated decrease in CD4+ T-cell proliferation | |

| Pneumococcal Vaccine ↓ Antibody response |

↓ In antibody potency and opsonization properties |

Furman et al. deployed a systems biology approach to determine age-related changes to seasonal influenza vaccine response [52].

Activation of the innate branch of the immune system is crucial for the production of a robust adaptive response [41]. This is, in part, accomplished through the production of inflammatory mediators (i.e., cytokines and chemokines) after activation of pattern recognition receptors (TLRs, NLRs, CLRs, RLRs) by pathogen-associated molecular patterns (PAMPs). There is an age-related decline in TLR-induced expression of the CD80 costimulatory molecule that is associated with a decrease in humoral immunity to influenza vaccine [42]. There is also a diminished level of TLR-induced secretion of the inflammatory cytokines IL-12/p40, IL-6, TNF-α, and IFN-α in DCs from older subjects, which correlates with a reduced influenza-specific antibody response [43]. An age-associated decrease in antibody response to influenza vaccine also inversely correlates with elevated levels of the anti-inflammatory, cytokine IL-10 [44]. Overall, immunosenescent factors influencing innate immunity, and the subsequent adaptive response to influenza vaccine, appear to involve altered activation of effector cells and the dysregulated release of pro- and non-inflammatory mediators.

Immunosenescence and its effect on adaptive immunity have been extensively studied. In the context of vaccine response and cellular immunity, an increase in CD8+CD28null T cells is associated with poor immunity to influenza vaccine [45,46]. The proliferative response of T-cells from older adults after vaccination against hepatitis B is diminished, which may be due to differences in expression of CD62L [47]. There is a decline in the frequency of influenza-specific CD4+ memory T-cells, and CD8+ effector and effector memory cells exhibit decreased cytolytic properties in response to influenza vaccine in older subjects [48,49]. Along with changes to cellular immunity, aging significantly impacts vaccine-induced humoral immunity. Sasaki et al. observed differences in the number of influenza vaccine-specific plasmablasts and plasmablast-derived polyclonal antibodies (PPAbs) from elderly, compared to young adults, but saw no observable difference in affinity or avidity [50]. This is not the case with pneumococcal vaccine, where older adults produce similar concentrations of antibodies as younger subjects, but with markedly lower potency and opsonic capacity [51]. These findings suggest there are differential age-associated effects that are specific to the vaccine administered. A successful vaccine candidate that elicits protective immunity against infectious diseases will incorporate factors that overcome the significant age-associated decline in the immune system over time.

Summary

Understanding mechanisms of immunosenescence and how they impact immune response to vaccines is critical to protecting aging individuals from infectious agents and other diseases. The elderly suffer disproportionate morbidity and mortality due to infectious diseases, and yet few vaccines have been developed to provide protective immunity specific to the elderly. Early research, as reviewed herein, identified age-related impacts on genes whose function is critical to innate and adaptive immune response to exogenous antigens. These early findings must be coupled with more sophisticated assays that can be utilized in a systems biology paradigm to holistically understand the simultaneous changes and interactions that together impair immune responses. Such understanding, informed by knowledge from other fields of endeavor, may allow us to identify and repair or overcome the obstacles to development of protective immune responses that aging imposes on the immune system. In turn, such understanding will lead to new vaccine approaches, new vaccine adjuvants, and perhaps new methods of vaccine administration or schedules that together may reverse the terrible burden of infectious disease threats in the aging human host.

Highlights.

Immunosenescence leads to increased susceptibility to infection and decreased vaccine response

HO gene expression may be an important element in age-related impairment of response to influenza vaccine

A systems level approach is needed to define the complex biological processes of immunosenescence

Systems biology has revealed vaccine-specific, age-related changes to apoptosis gene modules

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank Caroline L. Vitse for her editorial assistance. Research reported in this publication was supported by the National Institute of Allergy And Infectious Diseases of the National Institutes of Health under award/contract numbers U01AI089859, R37AI048793, (which recently received a MERIT Award) R01AI033144 and HHSN266200400065C (AI40065).

Footnotes

The content is solely the responsibility of the authors, and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Competing Interests

Dr. Poland is the chair of a Safety Evaluation Committee for novel investigational vaccine trials being conducted by Merck Research Laboratories. Dr. Poland offers consultative advice on vaccine development to Merck & Co. Inc., CSL Biotherapies, Avianax, Sanofi Pasteur, Dynavax, Novartis Vaccines and Therapeutics, PAXVAX Inc, and Emergent Biosolutions. Drs. Poland and Ovsyannikova hold two patents related to vaccinia peptide research. These activities have been reviewed by the Mayo Clinic Conflict of Interest Review Board and are conducted in compliance with Mayo Clinic Conflict of Interest policies. This research has been reviewed by the Mayo Clinic Conflict of Interest Review Board and was conducted in compliance with Mayo Clinic Conflict of Interest policies.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

* of special interest

** of outstanding interest

- 1.Oberg AL, Kennedy RB, Li P, Ovsyannikova IG, Poland GA. Systems biology approaches to new vaccine development. Current Opinion in Immunology. 2011;23:436–443. doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2011.04.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nakaya HI, Li S, Pulendran B. Systems vaccinology: learning to compute the behavior of vaccine induced immunity. Wiley Interdiscip Rev Syst Biol Med. 2012;4:193–205. doi: 10.1002/wsbm.163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3**.Poland GA, Kennedy RB, McKinney BA, Ovsyannikova IG, Lambert ND, Jacobson RM, Oberg AL. Vaccinomics, adversomics, and the immune response network theory: Individualized vaccinology in the 21st century. Seminars in Immunology. 2013;25:89–103. doi: 10.1016/j.smim.2013.04.007. This paper provides a review of issues relating to the concept and implications of vaccinomics and the immune response network theory, and its application to understanding vaccine immune responses. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mooney M, McWeeney S, Sekaly RP. Systems immunogenetics of vaccines. Seminars in Immunology. 2013;25:124–129. doi: 10.1016/j.smim.2013.06.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.De Groot AS, Sbai H, Aubin CS, McMurry J, Martin W. Immuno-informatics: Mining genomes for vaccine components. Immunol Cell Biol. 2002;80:255–269. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-1711.2002.01092.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.He Y, Rappuoli R, De Groot AS, Chen RT. Vaccine informatics. Journal of biomedicine & biotechnology. 2010;2010:765762. doi: 10.1155/2010/765762. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7*.Rappuoli R. Reverse vaccinology. Curr Opin Microbiol. 2000;3:445–450. doi: 10.1016/s1369-5274(00)00119-3. This paper provides a brilliant review of reverse vaccinology (i.e. genomic-based approaches to vaccine development) allowing for identification of novel antigen vaccine candidates. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Seib KL, Zhao X, Rappuoli R. Developing vaccines in the era of genomics: a decade of reverse vaccinology. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2012;18 (Suppl 5):109–116. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-0691.2012.03939.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9**.Querec TD, Akondy RS, Lee EK, Cao W, Nakaya HI, Teuwen D, Pirani A, Gernert K, Deng J, Marzolf B, et al. Systems biology approach predicts immunogenicity of the yellow fever vaccine in humans. Nat Immunol. 2009;10:116–125. doi: 10.1038/ni.1688. The first study for predicting immunogenicity using genome-wide profiling for yellow fever vaccine, YF-17D. This study demonstrates that systems biology approaches can be used to predict the adaptive immune response following yellow fever vaccine. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10*.Tan Y, Tamayo P, Nakaya H, Pulendran B, Mesirov JP, Haining WN. Gene signatures related to B-cell proliferation predict influenza vaccine-induced antibody response. European Journal of Immunology. 2014;44:285–95. doi: 10.1002/eji.201343657. Developed predictive models of the human immune response and identified gene signatures consistent with B cell proliferation and antibody response to influenza vaccination. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Franco LM, Bucasas KL, Wells JM, Nino D, Wang X, Zapata GE, Arden N, Renwick A, Yu P, Quarles JM, et al. Integrative genomic analysis of the human immune response to influenza vaccination. eLife. 2013;2:e00299. doi: 10.7554/eLife.00299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.O’Garra A. Systems Approach to Understand the Immune Response in Tuberculosis: An Iterative Process between Mouse Models and Human Disease. Cold Spring Harbor symposia on quantitative biology; 2013; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wang CC, Zhu B, Fan X, Gicquel B, Zhang Y. Systems approach to tuberculosis vaccine development. Respirology. 2013;18:412–420. doi: 10.1111/resp.12052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14**.Obermoser G, Presnell S, Domico K, Xu H, Wang Y, Anguiano E, Thompson-Snipes L, Ranganathan R, Zeitner B, Bjork A, et al. Systems scale interactive exploration reveals quantitative and qualitative differences in response to influenza and pneumococcal vaccines. Immunity. 2013;38:831–844. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2012.12.008. This study demonstrates that influenza and pneumococcal vaccines elicit different transcriptional and cellular responses in human blood. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Le Roch KG, Chung DW, Ponts N. Genomics and integrated systems biology in Plasmodium falciparum: a path to malaria control and eradication. Parasite immunology. 2012;34:50–60. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3024.2011.01340.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gomez CE, Perdiguero B, Jimenez V, Filali-Mouhim A, Ghneim K, Haddad EK, Quakkelaar ED, Delaloye J, Harari A, Roger T, et al. Systems analysis of MVA-C induced immune response reveals its significance as a vaccine candidate against HIV/AIDS of clade C. PLos ONE. 2012;7:e35485. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0035485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zak DE, Aderem A. Overcoming limitations in the systems vaccinology approach: a pathway for accelerated HIV vaccine development. Curr Opin HIV AIDS. 2012;7:58–63. doi: 10.1097/COH.0b013e32834ddd31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Andersen-Nissen E, Heit A, McElrath MJ. Profiling immunity to HIV vaccines with systems biology. Current opinion in HIV and AIDS. 2012;7:32–37. doi: 10.1097/COH.0b013e32834ddcd9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Targonski PV, Jacobson RM, Poland GA. Immunosenescence: Role and measurement in influenza vaccine response among the elderly. Vaccine. 2007;25:3066–3069. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2007.01.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Swain SL, Blomberg BB. Immune senescence: new insights into defects but continued mystery of root causes. Current Opinion in Immunology. 2013;25:495–497. doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2013.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Arason GJ, Bodvarsson S, Sigurdarson ST, Sigurdsson G, Thorgeirsson G, Gudmundsson S, Kramer J, Fust G. An age-associated decrease in the frequency of C4B*Q0 indicates that null alleles of complement may affect health or survival. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 2003;1010:496–499. doi: 10.1196/annals.1299.091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bik W, Baranowska B. Adiponectin - a predictor of higher mortality in cardiovascular disease or a factor contributing to longer life? Neuro endocrinology letters. 2009;30:180–184. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Atzmon G, Pollin TI, Crandall J, Tanner K, Schechter CB, Scherer PE, Rincon M, Siegel G, Katz M, Lipton RB, et al. Adiponectin levels and genotype: a potential regulator of life span in humans. The journals of gerontology Series A, Biological sciences and medical sciences. 2008;63:447–453. doi: 10.1093/gerona/63.5.447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Khabour OF, Mesmar FS, Alatoum MA, Gharaibeh MY, Alzoubi KH. Associations of polymorphisms in adiponectin and leptin genes with men’s longevity. The aging male: the official journal of the International Society for the Study of the Aging Male. 2010;13:188–193. doi: 10.3109/13685531003657800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.An W, Zhang L, Gong B, Ren S, Liu H. Screening of longevity-associated genes based on a comparison between dead and surviving populations. Gene. 2014;534:379–382. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2013.08.070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Albright FS, Orlando P, Pavia AT, Jackson GG, Cannon Albright LA. Evidence for a heritable predisposition to death due to influenza. J Infect Dis. 2008;197:18–24. doi: 10.1086/524064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Horby P, Nguyen NY, Dunstan SJ, Baillie JK. The role of host genetics in susceptibility to influenza: a systematic review. PLos ONE. 2012;7:e33180. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0033180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hashiba T, Suzuki M, Nagashima Y, Suzuki S, Inoue S, Tsuburai T, Matsuse T, Ishigatubo Y. Adenovirus-mediated transfer of heme oxygenase-1 cDNA attenuates severe lung injury induced by the influenza virus in mice. Gene Ther. 2001;8:1499–1507. doi: 10.1038/sj.gt.3301540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cummins NW, Weaver EA, May SM, Croatt AJ, Foreman O, Kennedy RB, Poland GA, Barry MA, Nath KA, Badley AD. Heme oxygenase-1 regulates the immune response to influenza virus infection and vaccination in aged mice. FASEB Journal. 2012;26:2911–2918. doi: 10.1096/fj.11-190017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Vo TK, Godard P, de Saint-Hubert M, Morrhaye G, Bauwens E, Debacq-Chainiaux F, Glupczynski Y, Swine C, Geenen V, Martens HJ, et al. Transcriptomic biomarkers of human ageing in peripheral blood mononuclear cell total RNA. Experimental Gerontology. 2010;45:188–194. doi: 10.1016/j.exger.2009.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Harries LW, Hernandez D, Henley W, Wood AR, Holly AC, Bradley-Smith RM, Yaghootkar H, Dutta A, Murray A, Frayling TM, et al. Human aging is characterized by focused changes in gene expression and deregulation of alternative splicing. Aging Cell. 2011;10:868–878. doi: 10.1111/j.1474-9726.2011.00726.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Florath I, Butterbach K, Muller H, Bewerunge-Hudler M, Brenner H. Cross-sectional and longitudinal changes in DNA methylation with age: an epigenome-wide analysis revealing over 60 novel age-associated CpG sites. Human Molecular Genetics. 2013 doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddt531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bell JT, Tsai PC, Yang TP, Pidsley R, Nisbet J, Glass D, Mangino M, Zhai G, Zhang F, Valdes A, et al. Epigenome-wide scans identify differentially methylated regions for age and age-related phenotypes in a healthy ageing population. PLoS Genet. 2012;8:e1002629. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1002629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ross OA, Hyland P, Curran MD, McIlhatton BP, Wikby A, Johansson B, Tompa A, Pawelec G, Barnett CR, Middleton D, et al. Mitochondrial DNA damage in lymphocytes: a role in immunosenescence? Experimental Gerontology. 2002;37:329–340. doi: 10.1016/s0531-5565(01)00200-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Seidman JC, Richard SA, Viboud C, Miller MA. Quantitative review of antibody response to inactivated seasonal influenza vaccines. Influenza and other Respiratory Viruses. 2012;6:52–62. doi: 10.1111/j.1750-2659.2011.00268.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Goodwin K, Viboud C, Simonsen L. Antibody response to influenza vaccination in the elderly: a quantitative review. Vaccine. 2006;24:1159–1169. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2005.08.105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Vermeiren AP, Hoebe CJ, Dukers-Muijrers NH. High non-responsiveness of males and the elderly to standard hepatitis B vaccination among a large cohort of healthy employees. Journal of clinical virology: the official publication of the Pan American Society for Clinical Virology. 2013;58:262–264. doi: 10.1016/j.jcv.2013.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wolters B, Junge U, Dziuba S, Roggendorf M. Immunogenicity of combined hepatitis A and B vaccine in elderly persons. Vaccine. 2003;21:3623–3628. doi: 10.1016/s0264-410x(03)00399-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Shapiro ED, Berg AT, Austrian R, Schroeder D, Parcells V, Margolis A, Adair RK, Clemens JD. The protective efficacy of polyvalent pneumococcal polysaccharide vaccine. New England Journal of Medicine. 1991;325:1453–1460. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199111213252101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sankilampi U, Honkanen PO, Bloigu A, Leinonen M. Persistence of antibodies to pneumococcal capsular polysaccharide vaccine in the elderly. The Journal of Infectious Diseases. 1997;176:1100–1104. doi: 10.1086/516521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Medzhitov R, Janeway CA., Jr Innate immune induction of the adaptive immune response. Cold Spring Harbor symposia on quantitative biology. 1999;64:429–435. doi: 10.1101/sqb.1999.64.429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.van Duin D, Allore HG, Mohanty S, Ginter S, Newman FK, Belshe RB, Medzhitov R, Shaw AC. Prevaccine determination of the expression of costimulatory B7 molecules in activated monocytes predicts influenza vaccine responses in young and older adults. J Infect Dis. 2007;195:1590–1597. doi: 10.1086/516788. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Panda A, Qian F, Mohanty S, van DD, Newman FK, Zhang L, Chen S, Towle V, Belshe RB, Fikrig E, et al. Age-associated decrease in TLR function in primary human dendritic cells predicts influenza vaccine response. Journal of Immunology. 2010;184:2518–2527. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0901022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Corsini E, Vismara L, Lucchi L, Viviani B, Govoni S, Galli CL, Marinovich M, Racchi M. High interleukin-10 production is associated with low antibody response to influenza vaccination in the elderly. J Leukoc Biol. 2006;80:376–382. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0306190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45*.Goronzy JJ, Fulbright JW, Crowson CS, Poland GA, O’Fallon WM, Weyand CM. Value of immunological markers in predicting responsiveness to influenza vaccination in elderly individuals. J Virol. 2001;75:12182–12187. doi: 10.1128/JVI.75.24.12182-12187.2001. This study demonstrates that influenza vaccine antibody responses decline with age and suggest the importance of including markers of immunosenescence such as CD8(+) CD28(null) T cells in immune profiles. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Saurwein-Teissl M, Lung TL, Marx F, Gschosser C, Asch E, Blasko I, Parson W, Bock G, Schonitzer D, Trannoy E, et al. Lack of antibody production following immunization in old age: association with CD8(+)CD28(−) T cell clonal expansions and an imbalance in the production of Th1 and Th2 cytokines. J Immunol. 2002;168:5893–5899. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.168.11.5893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Rosenberg C, Bovin NV, Bram LV, Flyvbjerg E, Erlandsen M, Vorup-Jensen T, Petersen E. Age is an important determinant in humoral and T cell responses to immunization with hepatitis B surface antigen. Human vaccines & immunotherapeutics. 2013;9:1466–1476. doi: 10.4161/hv.24480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kang I, Hong MS, Nolasco H, Park SH, Dan JM, Choi JY, Craft J. Age-associated change in the frequency of memory CD4+ T cells impairs long term CD4+ T cell responses to influenza vaccine. J Immunol. 2004;173:673–681. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.173.1.673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Zhou X, McElhaney JE. Age-related changes in memory and effector T cells responding to influenza A/H3N2 and pandemic A/H1N1 strains in humans. Vaccine. 2011;29:2169–2177. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2010.12.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Sasaki S, Sullivan M, Narvaez CF, Holmes TH, Furman D, Zheng NY, Nishtala M, Wrammert J, Smith K, James JA, et al. Limited efficacy of inactivated influenza vaccine in elderly individuals is associated with decreased production of vaccine-specific antibodies. J Clin Invest. 2011;121:3109–3119. doi: 10.1172/JCI57834. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Schenkein JG, Park S, Nahm MH. Pneumococcal vaccination in older adults induces antibodies with low opsonic capacity and reduced antibody potency. Vaccine. 2008;26:5521–5526. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2008.07.071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52**.Furman D, Jojic V, Kidd B, Shen-Orr S, Price J, Jarrell J, Tse T, Huang H, Lund P, Maecker HT, et al. Apoptosis and other immune biomarkers predict influenza vaccine responsiveness. Molecular systems biology. 2013;9:659. doi: 10.1038/msb.2013.15. This study identifies new candidate traits that associate with and predict the humoral response to influenza vaccine in young (20 to 30 years old) and old (60 to >89 years old) individuals. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]