Abstract

AM14 rheumatoid factor (RF) B cells in the MRL/lpr mice are activated by dual BCR and TLR7/9 ligation and differentiate into plasmablasts via an extrafollicular (EF) route. It was not known whether this mechanism of activation of RF B cells applied to other lupus-prone mouse models. We investigated the mechanisms by which RF B cells break tolerance in the NZM2410-derived B6.Sle1.Sle2.Sle3 (TC) strain in comparison to C57BL/6 (B6) controls, each expressing the AM14 HC transgene (tg) in the presence or absence of the IgG2aa autoAg. The TC, but not B6, genetic background promotes the differentiation of RF B cells into Ab-forming cells (AFCs) in the presence of the autoAg. Activated RF B cells preferentially differentiated into plasmablasts in EF zones. Contrary to the MRL/lpr strain, TC RF B cells were also located within germinal centers (GC), but only the formation of EF foci was positively correlated with the production of RF AFCs. Immunization of young TC.AM14 HC tg mice with IgG2aa anti-chromatin immune complexes (IC) activated RF B cells in a BCR and TLR9-dependent manner. However, these IC immunizations did not result in the production of RF AFCs. These results show that RF B cells break tolerance with the same general mechanisms in the TC and the MRL/lpr lupus-prone genetic backgrounds, namely the dual activation of the BCR and TLR9 pathways. There are also distinct differences, such as the presence of RF B cells in GCs and the requirement of chronic IgG2aa anti-chromatin ICs for full differentiation of RF AFCs.

Keywords: B cell, AM14, Rheumatoid factor, Extrafollicular foci, Lupus

Introduction

The breakdown in tolerance of autoreactive B cells is a hallmark of systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) that results in the secretion of pathogenic autoantibodies (autoAb). Unraveling the mechanisms by which B cell tolerance is breached is central to understanding lupus pathogenesis. Autoreactive B cells are eliminated in the bone marrow, largely through receptor editing. A large number of autoreactive B cells escape to the periphery, but humoral tolerance is maintained by a variety of mechanisms that prevent the activation of these B cells in healthy individuals (1). To the contrary, peripheral autoreactive B cells are activated in SLE patients and lupus-prone mice through mechanisms that are not well understood. The analysis of B cell receptor (BCR) transgenic (tg) mice has been an essential tool to study these mechanisms. In general, mice expressing BCR tg specific for lupus-related Ags (DNA-, RNA-, or Ig) have been more informative in characterizing the stage and site of the tolerance breakdown, as well as identifying some of the triggers than BCR-tg directed to foreign Ag.

In particular, the AM14 heavy chain (HC) tg produces anti-IgG2aa rheumatoid factor (RF) when paired with endogenous Vκ8 light chains (2). This autoreactive B cell model combines a disease relevant autoAb (3), RF, with the ability to control for the presence of the autoantigen (autoAg), IgG2aa complexed with chromatin (referred to as IgG2aa throughout the paper). In the BALB/c non-autoimmune background, AM14 B cells are clonally ignorant, i.e. they are present in the periphery with a seemingly normal phenotype, but they do not produce autoAbs (4). However, AM14 B cells are activated in an Ag-dependent manner to secrete RF in the Fas-deficient lupus-prone MRL/lpr mice (5). Further characterization showed that AM14 B cells are activated by anti-chromatin or RNA IgG2aa immune complexes (IC) in a TLR9- or TLR7- dependent manner both in vitro (6–8) and in vivo in MRL lupus-prone mice (9). For these reasons, the AM14 model is ideal to investigate the mechanisms by which B cells are activated in SLE, an autoimmune disease characterized by the production of Abs directed at nucleic acid-containing ICs.

Furthermore, when autoAg is present, MRL/lpr AM14 B cells undergo somatic hypermutation (SHM) while bypassing the germinal center (GC) reaction (10), and differentiate into short-lived plasmablasts (PBs) at the red pulp/T cell zone border (11). Exogenous administration of anti-chromatin IgG2aa ICs led to the differentiation of AM14 B cells into RF secreting Ab-forming cells (AFCs) in both young MRL+/+ and BALB/c mice. This suggested that the primary role of the MRL/lpr lupus-prone background is the production of anti-chromatin IgG2aa, leading to the activation of the clonally ignorant AM14 B cells (9). While these studies have identified a mechanism for the breakdown of AM14 RF B cell tolerance in the lupus-prone MRL/lpr mouse, it is not known whether the results are strain-specific. Indeed it is controversial whether, once activated, autoreactive B cells differentiate via a GC or EF pathway (12–14). Although Fas deficiency in MRL/lpr mice is not entirely responsible for the lupus phenotype (15, 16), it plays a significant role in the disease pathogenesis of these mice. Therefore, given that Fas deficiency is not common to SLE (17), it is of interest to understand whether the same mechanisms are involved in a different lupus-prone genetic background.

Here, we used the AM14 HC RF tg system in the NZM2410-derived B6.Sle1.Sle2.Sle3 (TC) lupus-prone strain to address these questions. TC mice contain the NZM2410-derived lupus susceptibility loci Sle1, Sle2, and Sle3 in the non-autoimmune B6 background. The presence of these three loci is necessary and sufficient to induce a lupus phenotype with the same penetrance as that of the NZM2410 strain (18). The advantage of using the TC model is that it contains only 6% of the NZM2410 genome and that B6 mice can be used as true genetic controls. Furthermore, characterization of the individual Sle loci has identified their contribution to lupus pathogenesis and towards B cell tolerance. The Sle1 locus induces the production of anti-nuclear Abs (19) and promotes a loss of tolerance to endogenously expressed HEL, with Sle1b/Ly108 regulating the transitional 1 (T1) checkpoint (20). Sle2 induces polyclonal B cell activation (21) and accelerates the breach of tolerance in anti-DNA 56R Tg B cells by inhibiting receptor editing (22). Finally, Sle3 affects multiple immune cell subsets (23, 24) and regulates IgH CDR3 sequences, SHM, and receptor editing (25). These studies, however, were designed to identify the role of the Sle loci in central/transitional tolerance and thus the impact of the loci in the activation of mature autoreactive B cells is not known. Therefore, here the TC lupus model is used to study the effects of both autoimmune genetic factors and the cognate Ag in the tolerance mechanisms of mature RF AM14 B cells.

In this study, we found that in the TC lupus background RF B cells break tolerance in the presence of the autoAg. Significant differences in the distribution of RF B cells in the peripheral, transitional, and marginal zone B cell subsets were found in TC mice in the presence of IgG2aa autoAg, suggesting that the TC autoimmune genetic background induces a response to autoAg in the early stages of peripheral differentiation. Activated AM14 B cells differentiated into short-lived PBs that were found preferentially in the extrafollicular (EF) zone. Contrary to the MRL/lpr model, the TC lupus background also revealed significant RF B cell localization to the GC when the autoAg was expressed. However, RF B cells were relatively excluded from GCs as compared to non-RF B cells, and the presence of EF but not GC RF clusters was associated with the production of RF antibody. In addition, we showed that the in vivo dual ligation of the BCR and TLR9 activates RF B cells in the TC background but not in the non-autoimmune B6 background, suggesting B cell intrinsic differences in activation susceptibility. Overall, these results showed the existence of TC specific features for AM14 B cell activation and differentiation, such as the presence of seemingly bystander RF B cells in the GCs, and the requirement of chronic prolonged autoAg/TLR stimulation. However, we demonstrate that similarly to the MRL/lpr model, the TC lupus background breaks tolerance in RF B cells in an Ag-dependent manner by stimulating a PB extrafollicular response.

Materials and Methods

Mice

The B6.NZM-Sle1NZM2410/Aeg Sle2NZM2410/Aeg Sle3NZM2410/Aeg/LmoJ (TC in this paper) congenic strain has been previously described (18). B6.TC.IgHa (TCa) mice were obtained by breeding TC to C57BL/6J-Cg-IghaThy1aGpila/J (B6a) mice, and the presence of the IgHa allele was determined by ELISA for serum IgG2aa and IgG2ab in mice of at least 2 months of age. B6.AM14.lpr mice (5) were bred to B6 and to B6a mice to produce B6.AM14 and B6.AM14.IgHa (B6.AM14a), respectively. The AM14 HC tg was detected by PCR as previously described (2). B6.AM14 and B6.AM14a mice were bred to TC and TCa to produce TC.AM14 and TC.AM14.IgHa (TC.AM14a) mice, respectively. The IgHa allotype was maintained as heterozygous in B6.AM14a and TC.AM14a mice. B6.Rag1−/− mice were obtained from Jackson Laboratories and BALB/c.Rag2−/− mice were obtained from Taconic. Only female mice were used in this study. All mice were bred and maintained at the University of Florida in specific pathogen-free conditions. Animal protocols were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of the University of Florida.

Antibody and antibody forming cell measurement

Serum anti-IgG1 and anti-IgG2ab RF was measured in non-Tg mice with plates coated with IgG1/λ or IgG2a/λ and detected with an anti-κ-alkaline phosphatase (AP) secondary Ab (all from Southern Biotech), as previously described (2). 4-44 idiotype-specific IgM was detected in Immulon 4 plates (Thermo Scientific) coated with 5 ug/ml goat anti-mouse μ chain (Millipore). Culture supernatants were diluted 1:10 while serum samples were diluted 1:100. 4-44-Biotin was used as the secondary Ab followed by Streptavidin-AP (Southern Biotech). Total IgM was measured from culture supernatant diluted 1:100 or in the sera of B6.Rag1−/− mice diluted 1:10 in Immulon 2 plates coated with goat anti-μ chain (Millipore) and detected with anti-IgM-AP as the secondary Ab (Southern Biotech). IgG2aa-specific IgM RF was quantified in Immulon 2 plates coated with 25 ug/ml TNP-BSA (Biosearch Technology) followed by anti-TNP IgG2aa (BD Biosciences). Sera were diluted 1:100 and the secondary Ab was anti-IgM-AP (Southern Biotech). To quantify anti-chromatin Abs, Immulon 2 plates (Thermo Scientific) were coated with 50 ug/ml dsDNA (Sigma) followed by 10 ug/ml of total histone (Roche). Serum samples were diluted 1:100 and specific isotypes were detected with the following secondary Ab: anti-IgG2b conjugated with alkaline phosphatase (AP) (Southern Biotech), rabbit anti-IgG2aa or IgG2ab (Nordic Immunological Labs) followed by goat anti-rabbit IgG-AP (Sigma). For both anti-chromatin and the IgG2aa specific IgM RF ELISA, pooled TC.IgHa sera were used to standardize results into relative units. To quantify anti-TNP IgG2aa and IgG2ab, serum samples diluted 1:100 were applied to Immulon 2 plates coated with TNP-BSA. Rabbit anti-IgG2aa or IgG2ab (Nordic Immunological Labs) followed by goat anti-rabbit IgG-AP (Sigma) were used as secondary Abs. 4-44 idiotype-specific AFCs were quantified by ELISPOT in multiscreen filter plates (Millipore) coated overnight with 5 ug/ml goat anti-μ chain. The plates were then washed and blocked for 1 h with RPMI 1640 (Cellgro) supplemented with 5% FBS. Serially diluted splenocytes were cultured in duplicate and incubated overnight at 37°C. Bound Ab was detected with 4-44-Biotin (2) and Streptavidin-HRP (Vector). Plates were developed with 3-amino-9-ethylcarbazole (Sigma) and AFCs were counted using a Bioreader 4000 Pro-x (Bio-Sys).

Flow Cytometry

Single cell suspensions of splenocytes were treated with 155 mM of NH4Cl for 5 min to lyse red blood cells and were passed through a pre-separation filter (Miltenyi Biotec) to remove debris. Cells were blocked on ice for 30 min with 10% rabbit serum and anti-CD16/32 (2.4G2) in staining buffer (2.5% FBS, 0.05% sodium azide in PBS). Cells were then stained for 30 min on ice with predetermined amounts of the following fluorophore-conjugated or biotinylated Abs: B220 (RA3-6B2), CD19 (1D3), CD21 (4E3), CD23 (B3B4), CD44 (IM7), CD93 (AA4.1), CD138 (281-2), CD184 (2B11/CXCR4), FcγRIIb (2.4G2), I-Ab (AF6-120.1), IgM (II/41), IgMa (DS-1), and IgMb (AF6-78). For the detection of AM14 idiotype-positive B cells, membrane staining with 4-44-biotin followed by intracellular staining with 4-44-Alexa647 using the Cytofix/Cytoperm Kit (BD Biosciences) was performed as previously described (2). The NIM-R6 Ab (26), which recognizes both CD22a and CD22b alleles (27) was revealed with either FITC-labeled mouse anti-rat IgG1 (eBioscience) or PE-labeled mouse anti-rat-IgG1 (Southern Biotech). For detection of biotinylated Abs, streptavidin conjugated to Phycoerythrin (PE) or Allophycocyanin (APC)-CY7 was used. Live cells were identified with Fixable Viability Dye eFluor 660 (eBioscience) following primary Ab staining. BrdU incorporation into Id+ cells was measured with the BrdU Flow kit (BD Biosciences) after mice were injected i.p. with 2 mg BrdU 12 h prior to sacrifice. Stained cells were analyzed on CyAn flow cytometer (Beckman Coulter) and at least 100,000 cells were acquired per sample.

Cell Transfers and Cell Cultures

Splenocytes or bone marrow (BM) cells from 7 months old TC.AM14a mice were treated with 50 ug/ml mitomycin C (Sigma) in PBS for 20 min at 37°C. The cells were then washed and 20 × 106 viable cells were transferred i.v. into B6.Rag1−/− recipients. Serum Abs were analyzed by ELISA two weeks post-transfer. For the TLR9 stimulation experiment, 2 ×106 splenocytes from 7 months old mice were cultured with 1ug/ml of CpG (Invivogen) for 5 d at 37°C in RPMI media supplemented with 10% FBS, HEPES, 2-Mercaptoethanol, L-Glutamine, and penicillin-streptomycin. Culture supernatants were collected to measure Id+ RF production by ELISA.

Histology and Immunofluorescence

Frozen spleen sections prepared as previously described (28) were stained with 4-44-biotin, B220 (anti-CD45R)-Alexa 488, GK1.5 (anti-CD4)-DyLight649, 1D3.2 (anti-CD19)-Alexa 647, 30H12 (anti-CD90.2)-Alexa 647, BM8 (anti-F4/80)-Alexa 647 (Caltag), and PNA-FITC (Vector). Unless purchased as indicated, Abs were prepared in our laboratory as previously described (2). Streptavidin-Alexa 555 (Molecular Probes) was used to detect 4-44-biotin. Nuclei were identified with 4′,6′-diamidino-2-phenylindole (Molecular Probes). Fluorescent images were captured on a Nikon Eclipse Ti-U microscope and processed in Adobe Photoshop. The presence or absence of AM14+ cells in GCs was noted. The AM14 cell patterns in follicular or EF foci were scored on a 0–3 scale as illustrated in Fig. 5 and described in the legend, without knowledge of the genotype of the mice from which the sections were derived. One section was scored per mouse, with additional sections performed on selected mice showing staining patterns consistent with the ones that were originally scored (data not shown).

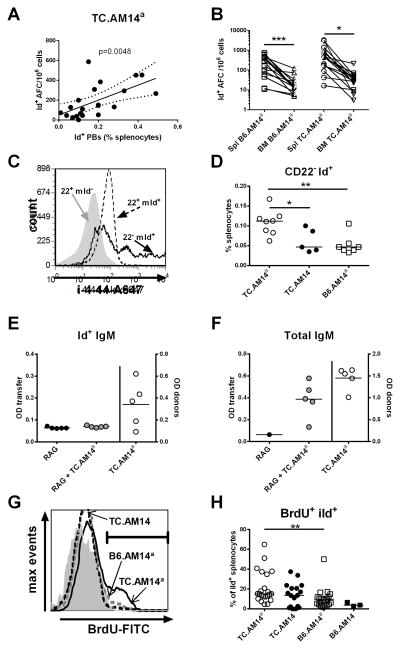

Figure 5. AM14 RF is produced by plasmablasts in TC.AM14a mice.

A. The percentage of Id+ PBs was correlated with the proportion of Id+ AFCs in the spleen of 7 months old TC.AM14a mice (Pearson’s R = 0.5913). B. Frequency splenic (Spl) and BM Id+ AFCs in B6.AM14a and TC.AM14a 7 months old mice. Linked data points were obtained in the same mouse. The significance levels correspond to 2-tailed paired t tests. C. iId expression relative to CD22 expression in Tg B cells gated as either CD22+ (22+ mId+, dotted line histogram) or CD22− (22− mId+, plain line histogram) in a representative TC.AM14a mouse. Non-tg B cells (22+ mId−, filled gray histogram) are shown as control. D. Percentages of CD22− Id+ splenocytes in TC.AM14a, TC.AM14 and B6.AM14a 7 months old mice. E–F. TC.AM14a splenocytes were treated with mitomycin C before transfer into B6.Rag1−/− mice. Serum Id+ IgM (E) and total IgM (F) were measured before (RAG) and 2 weeks after transfer (RAG + TC.AM14a), as well as in the donor mice (TC.AM14a, right axes). These data are representative of two independent sets of transfers. G. Representative histograms of BrdU content in iId+ gated splenocytes in B6.AM14a (grey dash), TC.AM14 (black dash) and TC.AM14a (black line) mice. The grey filled histogram shows the isotype control. H. Percentage of BrdU+ iId+ splenocytes in 7 months old mice. Significance levels of Dunn’s Multiple Comparison tests are shown (D and H).

Hybridoma Immunizations

The hybridoma clones PL2-3 (anti-chromatin IgG2aa), PL2-8 (anti-chromatin IgG2b), Hy1.2 (anti-TNP IgG2aa) and C4010 (anti-TNP IgG2ab) have been previously described (9). Two months old mice were first injected i.p. with 250 ul of pristane (Sigma) on d0 and d7, then with 107 hybridoma cells on d10, and sacrificed on d17. For TLR9 inhibition studies, 100 ug of the TLR9 inhibitor ODN 2088 (Invivogen) was co-injected with the hybridoma cells. This dose of TLR9 inhibitor was sufficient to suppress a humoral immune response for up to 4 weeks (29). Other mice were immunized i.p. with 1 mg/ml of purified PL2-3 Ab on d10, d12, and d15 following pristane injection and sacrificed on d18. To obtain purified PL2-3 Ab, BALB/c.Rag2−/− mice were injected with 200 ul pristane and 107 hybridoma cells 5 d later. The mice were euthanized when their body weight had increased by 15 %. Ascitic fluid was spun down and the supernatant was filtered using a 0.45 μm SFCA syringe filter (Corning). Purified PL2-3 antibody was quantified in Immulon 2 plates coated with 5 ug/ml rat anti-mouse IgG2a (BD Pharmingen). Both samples and mouse IgG2a standard (Southern Biotech) were serially diluted threefold and goat anti-mouse IgG2a-AP (Southern Biotech) was used as the secondary Ab.

Statistics

Data analysis was performed with GraphPad Prism 5.0 software. Unless indicated, graphs show median values and statistical significance between strains was determined by two-tailed Mann-Whitney tests or t tests when the data were normally distributed. Multiple test corrections were applied when several strains were compared. Comparisons between time course data were performed using non-linear regression fit comparisons. Significance levels in figures were labeled as * for p<0.05, ** for p<0.01, and *** for p<0.001.

Results

The TC lupus-prone background and the expression of the autoAg promote spontaneous AM14 B cell activation

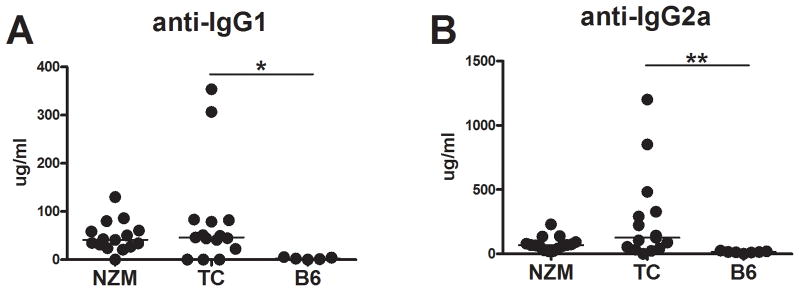

NZM2410 and TC mice produced high levels of anti-IgG1 and anti-IgG2ab RF as compared to B6 controls (Fig. 1A–B), demonstrating that RFs are part of the autoAb repertoire of the NZM2410 murine lupus model, as was previously shown for MRL/lpr (30). TC mice have a lymphoid expansion with the number of both T and B cells increasing with age (18). The presence of the AM14 HC tg significantly reduced the TC lymphoid expansion, but TC.AM14a and TC.AM14 mice still had a significantly higher number of splenocytes than B6.AM14a and B6.AM14 mice, respectively (Sup. Fig. 1A–B). More specifically for this study, AM14 HC tg expression reduced the percentage of total B cells on both the TC and B6 backgrounds. However, the percentage and number of B cells were significantly higher in TC.AM14a than in B6.AM14 a mice, showing that the autoimmune prone genetic background still promotes the relative expansion of B cells in spite of their reduced HC repertoire. Notably, a larger percentage of B cells was found in TC.AM14a than in TC.AM14 mice, suggesting that the presence of the autoAg in the autoimmune background may favor selection or expansion (Sup. Fig. 1C–D).

Figure 1. NZM2410 and TC mice spontaneously produce RF Abs.

Serum anti-IgG1 (A) and -IgG2ab (B) RF produced by 5–7 month old NZM2410 (NZM), TC and B6 mice. Significance levels of Mann-Whitney tests between TC and B6 mice are shown.

The effect of the genetic background on the expression of the IgMa HC tg relative to that of the endogenous IgMb HC could be examined only in the IgHb genetic background since the AM14 tg is of the a allotype. The percentage of B cells expressing the IgMa HC tg was significantly higher in the TC.AM14 than in B6.AM14 spleens (Sup. Fig. 2A), suggesting that the TC background favors the selection and/or expansion of the HC tg B cells. The percentage of B cells was similar in TC and TCa spleens (data not shown), indicating that the a allotype by itself does not cause B cell expansion as compared to the b allotype. IgMa expression levels were lower on B6.AM14a as compared to B6.AM14 B cells, but significantly higher on TC.AM14a than on TC.AM14 B cells (Sup. Fig. 2B–C). Downregulation of surface IgM is a marker of Ag encounter and anergy (31). Although our measurement of IgMa expression on AM14a B cells cannot distinguish between Tg and endogenous alleles, our results suggests that the TC genetic background promotes B cell expansion, HC selection, and decreased BCR expression in the presence of autoAg. The expression of the AM14 HC tg did not affect the number and activation status of CD4+ T cells in any of the four strains of mice (data not shown).

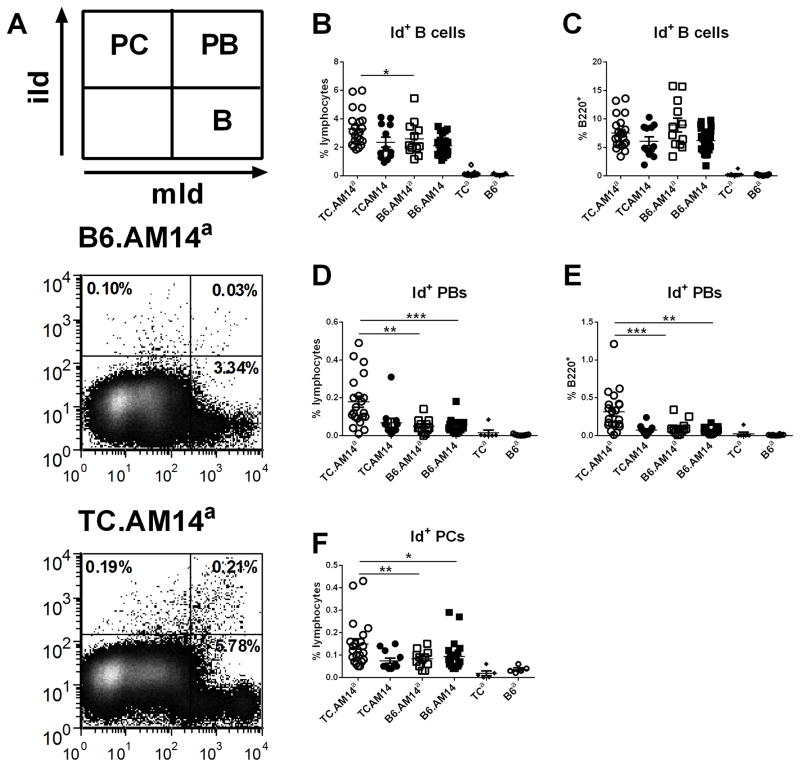

The anti-idiotype (Id) Ab, 4-44, identifies B cells in AM14 HC tg mice that express the correct Vκ8 light chains to reconstitute RF activity (2). The AM14 HC+ Vκ8+ Id+ B cell populations were characterized by flow cytometry in 7 months old mice from the four AM14 Tg strains. Id+ membrane and intracellular staining identified membrane-positive (mId+) intracellular-negative (iId−) idiotype (mId+ iId−) B cells, mId+ iId+ plasmablasts (PB), and mId− iId+ plasma cells (PC) (Fig. 2A). As in MRL and BALB/c mice (4, 5), mId+ iId− B cells were found in the spleen (Fig. 2B–C). The percentage of mId+ iId− B cells in TC.AM14a spleens, which was within the range of mId+ iId− B cells in MRL/lpr.AM14 spleens (4), was significantly higher than in the three other strains (Fig. 2B). However the percentage of Id+ among total B cells was similar between all four AM14 tg mice (Fig. 2C). Thus, this indicates that the TC background expands total B cells (Sup. Fig. 1C–D) as well as AM14 HC tg B cells (Sup. Fig. 2A), but does not expand preferentially mId+ iId− among these B cells.

Figure 2. RF B cell activation and differentiation into plasmablasts is controlled by the genetic background and autoAg expression.

A. Gating scheme and representative FACS plots from TC.AM14a and B6.AM14a mice showing the three B cell populations quantified in this study. Splenocytes were gated on live lymphocytes based on forward and side scatters characteristics. Id+ B cells (B–C), Id+ PBs (D–E) and Id+ PCs (F) were identified with membrane (mId+) and intracellular (iId+) idiotype specific (4-44) staining of splenocytes from 7 month old mice from each of the four AM14 strains, with the non-Tg TCa and B6a mice shown as controls. mId+ iId− B cells (B–C) and mId+ iId+ PBs (D–E) are shown as percentage of live lymphocytes or B220+ splenocytes. mId− iId+ PCs are only shown as percentage of live lymphocytes (F) since their B220 expression is low to negative. Horizontal lines show median value for each group. Significance levels of Dunn’s Multiple Comparison tests are shown.

TC.AM14a mice showed higher percentages (Fig. 2D and F) and numbers (data not shown) of mId+ iId+ PBs and mId− iId+ PCs than the other three strains. In addition, the percentage of mId+ iId+ PBs was expanded among TC.AM14a B cells as compared to the three other strains (Fig. 2E). Overall, these results showed that, as in the MRL/lpr mice (5), autoreactive AM14 Id+ B cells are not tolerized and eliminated on either the B6 or TC background. Furthermore, the combined presence of the lupus-prone genetic background and the autoAg leads to the differentiation and expansion of autoreactive RF Id+ B cells toward Ab producing PB and PC subsets in the spleen.

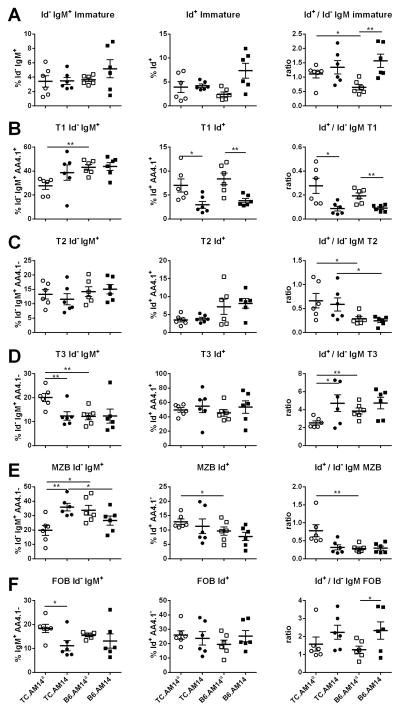

To gain a better insight into the peripheral stages at which either the TC autoimmune background or the presence of the autoAg could expand the Id+ B cells, we compared the percentages of Id+ and Id− IgM+ B cells in the spleens of 7–9 month old mice from the four AM14 Tg strains. The observed variations in splenocyte and total B cell numbers between these strains make the percentages rather than absolute numbers a more informative measure. For a given stage, the ratio between Id+ and Id− IgM+ cells indicates whether the selection of Id+ cells differs from that of Id− IgM+ cells, and whether these ratios differ among strains. Immature B cells are equally represented amongst Id+ and Id− IgM+ cells TC.AM14a spleens, but there were proportionally less Id+ immature B cells in B6.AM14a spleens (Fig. 3A). Furthermore, Id+ cells were more represented in the immature subset in B6.AM14 than in B6.AM14a spleens. Within the immature B cells, significant differences were observed for each of the transitional stages (T1, T2, and T3). Overall, Id+ B cells were found in the T1 subset at a much lower frequency than the Id− IgM+ cells (Fig. 3B). Each of the a allotype strains presented a significantly higher Id+/Id− IgM+ T1 ratio than the b allotype strain with the matched background. As the T1 subset corresponds to a stage in which many autoreactive B cells are eliminated (32), our data shows a corresponding expansion in the two strains in which the Id+ cells are autoreactive. Furthermore, our results showed that Id+ cells go through the T1 stage in a similar fashion between TC.AM14a vs. B6.AM14a spleens. Id+ cells were also found in the T2 subset relatively less frequently than the Id− IgM+ cells (Fig. 3C). There was however a significant difference between the TC and B6 stains, with relatively more T2 Id+ cells in the former, regardless of the presence of autoAg. Correspondingly, the majority of Id+ immature B cells were found in the T3 subset, regardless of the strain and presence of autoAg (Fig. 3D). However, the Id+ cell selection to T3 relative to Id− IgM+ cells was significantly lower in TC.AM14a spleens, which may indicate a lower anergy process for the autoreactive Id+ in that strain, since the T3 subset contains anergic B cells (33). Finally, Id+ B cells were recruited to the marginal zone B cell (MZB) compartment relatively less frequently than Id− IgM+ cells (Fig. 3E) and the reverse was true for follicular B cells (Fig. 3F). There were significantly more Id+ MZB cells in TC.AM14a than B6.AM14a spleens. Overall these results showed that the combination of the TC autoimmune background and the presence of the autoAg shape the peripheral differentiation of Id+ B cells. In particular, the combination of these two variables results in a relative expansion of Id+ cells in the T1 and MZB subsets and a relative decreased frequency of these cells in the T3 subset as compared to Id− B cells in TC.AM14a mice.

Figure 3. RF B cell differentiation into splenic B cell subset is controlled by the genetic background and autoAg expression.

Live splenic B cells from 7–9 month old mice from each of the four AM14 strains were gated either as Id− IgM+ (left column) or Id+ IgM+ cells (middle column). The frequency of these cells was compared among the four strains the following subsets: A CD93+ immature B cells; B. CD93+ IgMhi CD23− T1 transitional B cells; C. CD93+ IgMhi CD23+ T2 transitional B cells; D. CD93+ IgMlo CD23+ T3 transitional B cells; E. CD93− IgMhi CD23− MZB cells; F. CD93− IgM+ CD23+ FOB cells. The column on the right shows the ratio between Id+ and Id− B cells in individual mice for each subset. Graphs show means and standard deviation of the means, with significance levels of t tests.

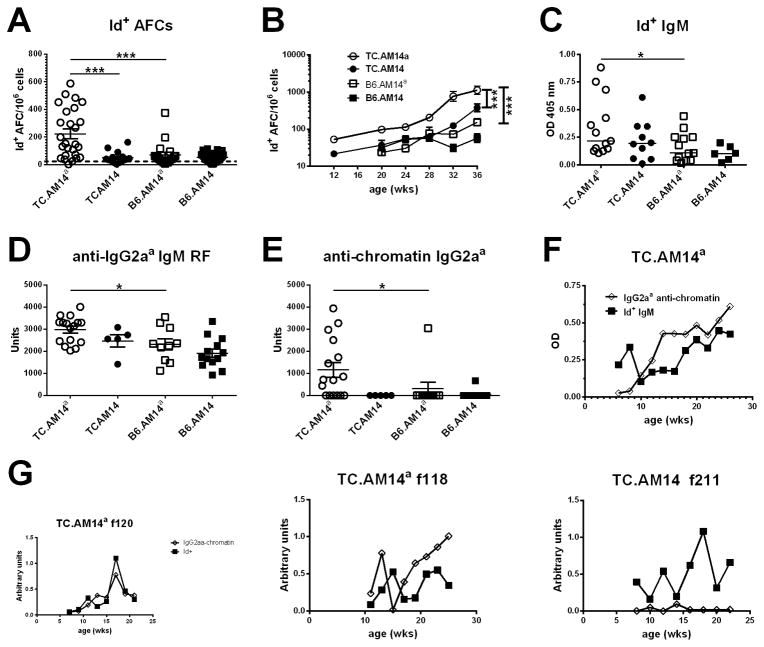

Differentiation of RF Id+ antibody forming cells in TC.AM14a mice correlates with anti-chromatin IgG2aa secretion

The activation of RF B cells in TC.AM14a mice was further analyzed for the presence of Id+ Ab. High numbers of splenic Id+ AFCs were detected only in TC.AM14a mice (Fig. 4A), confirming the results obtained by flow cytometry. Importantly, the number of Id+ AFCs was statistically higher in the presence of the autoAg in the TC mice compared to its absence (compare TC.AM14a to TC.AM14, Fig. 4A). In the presence of autoAg, the TC background also substantially increased the number of Id+ AFC (compare TC.AM14a to B6.AM14a, Fig. 4A). The TC genetic background increased the number of Id+ AFCs with age, which remained the highest in TC.AM14a mice. The number of Id+ AFCs also significantly increased (p = 0.001) in TC.AM14 mice as compared to B6.AM14 mice in spite of the absence of autoAg (Fig. 4B). In addition, Id+ ELISPOTs had a significantly larger diameter in the two TC strains than the B6 strains (data not shown). This suggested that the lupus-prone TC genetic background favors the expansion and secretory capacity of Id+ AFCs. Confirming the ELISPOT results, sera from TC.AM14a mice contained significantly higher levels of Id+ IgM (Fig. 4C). Anti-IgG2aa IgM (Fig. 4D), which is RF that include Id+ IgM but also endogenously encoded autoAbs, was also significantly higher in TC.AM14a than in B6.AM14a mice, suggesting that B cells producing endogenous anti-IgG2aa RF break tolerance in TC.AM14a mice in a similar manner as Id+ RF. As expected, the levels of Id+ IgM were positively correlated with the number of Id+ AFCs in TC.AM14a mice (data not shown).

Figure 4. The production of Id+ RF by TC.AM14a mice is correlated with the secretion of anti-chromatin IgG2aa.

A. Production of Id+ AFCs in the spleens of 7 months old mice from each of the AM14 HC tg strains. The dotted line shows the average background level found in non-Tg mice. B. The number of Id+ splenic AFCs increases with age in TC.AM14a and TC.AM14 mice. Data was compiled from 5–20 mice per strain per age-point. Statistical significance is indicated for pair-wise comparisons between non-linear regressions for each strain. There is also a significant difference between TC.AM14 and B6.AM14a (p = 0.007). Serum Id+ (C) and anti-IgG2aa (D) IgM RF in 7 months old mice. E. Serum anti-chromatin IgG2aa in 7 months old mice. F. Time-course analysis of anti-chromatin IgG2aa and Id+ IgM levels in sera collected bimonthly from a cohort of 10 TC.AM14a mice. The data points show mean values. SEM is not shown for clarity. G. Representative time course analysis of anti-chromatin IgG2aa and Id+ IgM levels in individual mice (two TC.AM14a f120 and f118, and one TC.AM14 f211 mice). Significance levels of Dunn’s Multiple Comparison tests or Mann-Whitney tests are shown in panels A, C–E.

Anti-chromatin IgG2aa, the presumptive autoAg for Id+ AM14 B cells, was detected only in TC.AM14a sera (Fig. 4E). The same result was obtained for anti-dsDNA IgG2aa (data not shown). TC.AM14 sera contained high levels of anti-chromatin and anti-dsDNA IgG2ab (data not shown), confirming the isotype-specificity of the RF autoAg. We did not find any correlation between the level of anti-chromatin IgG2aa at the time of sacrifice and the number of Id+ AFCs in individual mice (data not shown). Since the number of AFCs reflects events, such as activation of expanding RF clones (28), that most likely occurred earlier in life, we conducted a time-course experiment and found a parallel rise of serum anti-chromatin IgG2aa and Id+ IgM in TC.AM14a mice (Fig. 4F and G). Transient production of Id+ IgM was found in some TC.AM14 mice in the absence of anti-chromatin IgG2aa (Fig. 4G). These data suggest that the TC autoimmune background provides a transient antigen-independent activation of Id+ B cells, which is sustained and expanded in the presence of the autoAg.

Id+ RF are produced by plasmablasts in TC.AM14a mice

Id+ RF is produced spontaneously by short-lived proliferating PBs in MRL/lpr mice (28) and after transfer of anti-chromatin IgG2aa in BALB/c and MRL+/+ mice (9). We used several lines of investigation to address whether this was also the case in the TC model. There was a positive correlation between the number of AFCs in 7 mo old TC.AM14a mice and the percentage of Id+ PBs (Fig. 5A). However, this was not the case for PCs in the spleen TC.AM14a mice (data not shown). In addition, Id+ AFCs were found at a significantly higher level in the spleen than in the BM of either B6.AM14a or TC.AM14a mice (Fig. 5B). These results suggest that Id+ RF was predominantly produced by short-lived PBs rather than by more differentiated PCs. Cells expressing intracellular iId+ (PB and PC) in TC.AM14a mice demonstrated the same surface maker expression as described for PBs in the MRL/lpr strain, including downregulation of B220, IgM, FcγR2b, and class II MHC, but increased expression of CD138, CD44 and CXCR4 (Sup. Fig. 3A–G). This confirms that detection of iId by flow cytometry identified AM14 cells that have differentiated into AFCs. Differentiation of AM14 cells into AFCs in the MRL/lpr model also involved the downregulation of CD22 (28). We found a high concordance between iId+ expression and CD22 downregulation, with iId+ expression found at the highest level on the CD22− mId+ subset (Fig. 5C). Interestingly, CD22 expression by iId+ mId+ PBs was lower in TC.AM14a than in B6.AM14a mice (MFI: 15.62 ± 1.63 vs. 27.27 ± 6.50, p < 0.05), suggesting an acceleration of the terminal differentiation towards AFCs on the autoimmune background. Furthermore, the percentage of CD22− Id+ B cells was significantly higher in TC.AM14a than in either TC.AM14 or B6.AM14a mice (Fig. 5D). This result indicated that the differentiation toward Id+ RF production that occurred in TC.AM14a mice also involved CD22 downregulation, again in an autoAg-specific manner that was augmented by the TC background.

To directly test the hypothesis that Id+ RF is produced by short-lived PBs, splenocytes from Id+ IgM secreting TC.AM14a mice were treated with mitomycin C to deplete proliferating cells and then transferred into B6.Rag1−/− recipients. Two weeks later, the transferred non-proliferating splenocytes had failed to produce Id+ IgM (Fig. 5E). Total IgM was however detected in the sera of recipients (Fig. 5F), indicating that the transferred cells contained long-lived AFCs. Therefore, this data suggest that Id+ IgM secreting B cells are not part of the long-lived repertoire of TC.AM14a mice, although it cannot be formally excluded that Id+ RF was present below the level of detection in this experiment. Similar results were obtained with mitomycin-treated BM cells from TC.AM14a mice (data not shown).

Finally, TC.AM14a spleens contained a significantly higher percentage of proliferating BrdU+ iId+ cells than did B6.AM14a spleens (Fig. 5G–H). Collectively, these results demonstrated that, as in MRL/lpr mice, Id+ RF is primarily produced by proliferating PBs in TC.AM14a mice. The values for TC.AM14 mice were intermediate in between that of TC.AM14a and B6.AM14a, with some mice with very low percentage of proliferating iId+ cells and none with very high percentage of iId+ cells (Fig. 5H), implying a role of the autoAg in full PB differentiation. Overall, our data show that the activation of RF B cells in the TC background in the presence of the autoAg results in RF production by short-lived PBs.

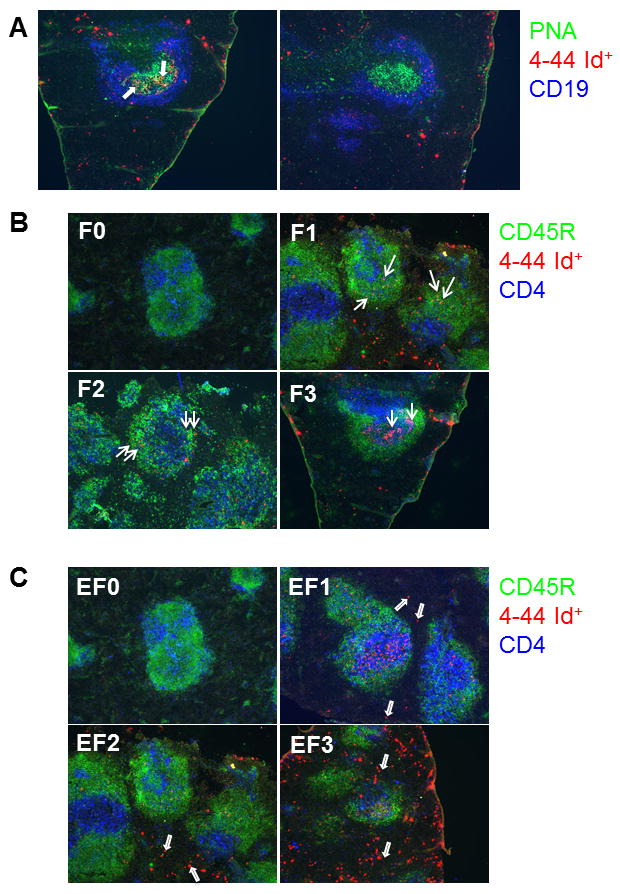

Activated AM14 B cells preferentially differentiate via an EF route

A major finding of the MRL/lpr AM14 model was that autoreactive Id+ RF splenic B cells differentiated in EF foci and bypassed the GC reaction (10, 28). We evaluated whether this finding extended to the TC model by histology and flow cytometry. Unlike the MRL/lpr model, Id+ RF B cells were found in GCs in TC.AM14a mice (Fig. 6A), which frequently presented both Id+ and Id− GCs. By histology, the total number of GCs was significantly higher in TC.AM14a than in B6.AM14a spleens and a similar trend was noted between TC.AM14 and B6.AM14 spleens (Fig. 7A). Eight out of 11 (72.7%) TC.AM14a mice presented AM14 Id+ GCs, which were also found in 2 out of 5 (40%) B6.AM14a mice, but not in any TC.AM14 or B6.AM14 mice (Fig. 7B). This suggests that the TC background expands the number of GCs, and that autoAg expression is necessary for the development of Id+ GCs. Similarly to B6.AM14a mice, AM14 RF B cells were found in very old BALB/c mice but only in the presence of autoAg (34); this could reflect a mild-degree of age-related autoimmunity in both of these nominally “normal” mouse strains.

Figure 6. Splenic RF B cells form extrafollicular clusters in TC.AM14a mice.

A. Representative immunofluorescence staining showing an Id+ (left, arrows pointing to Id+ PNA+ B cells) and Id− (right) GC. PNA is shown in green, AM14 idiotype (4-44) in red, and CD19 in blue. Immunofluorescence staining illustrating Id+ cell follicular (B) or EF (C) pattern scoring on a 0–3 scale. CD45R is shown in green, 4-44 in red, and CD4 in blue: (0) No AM14+ cells. (1) Few AM14+ cells. (2) Moderate number of AM14+ cells. (3) High number of AM14+ cells. Arrows point to representative Id+ cells for each pattern. Note that both F and EF Id+ cells may be present on a same section, such as (B) F1, in which the arrows point to a few follicular Id+ cells illustrating the F1 score, in addition to abundant EF Id+ cells in the bottom area (which correspond to an EF3 score).

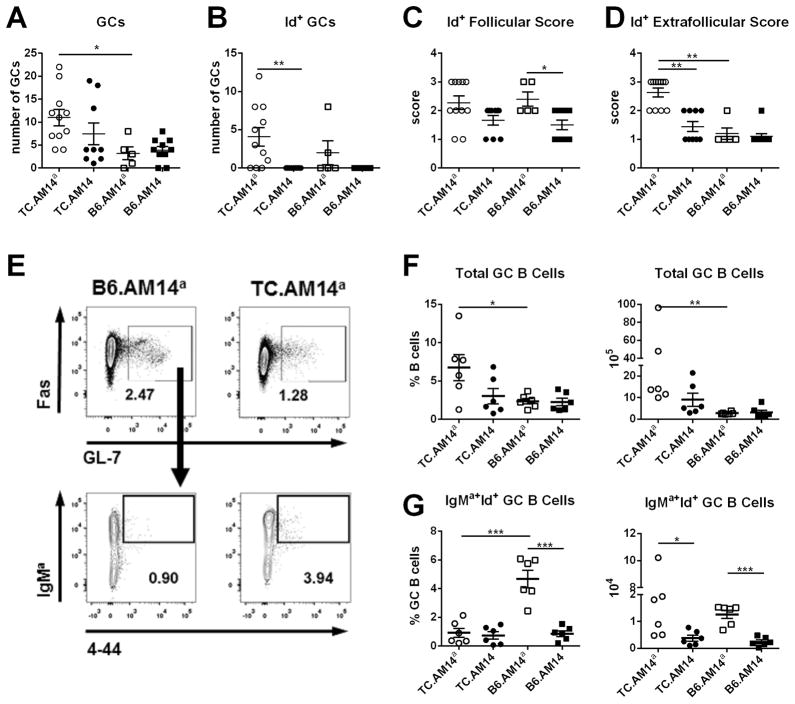

Figure 7. Id+ cells are relatively excluded from GCs in TC.AM14a spleens.

A. The number of total GCs (A) and Id+ GCs (B) were quantified from spleen sections for each of the AM14 HC tg strains. Follicular (C) and EF (D) scores for each of the 4 strains. The graphs show mean + SEM of 6–15 mice per strain at 7 month of age. E. Representative FACS plots shown B220+ gated GL7+ Fas+ total GC B cells (top), from which the percentage of IgMa+ 4-44+ Id+ GC B cells (bottom) was quantified. Percentage and absolute numbers of total (F) and Id+ (G) GC B cells in 7–9 months old mice. Significance levels of Mann-Whitney tests or Dunn’s Multiple Comparison tests (D) are shown.

More frequently than in GCs, Id+ cells were found in foci in and outside splenic follicles, which was scored on a 0–3 scale, as illustrated in Fig. 6B for follicular presence and Fig. 6C for EF foci. Follicular localization was found to a greater extent in IgG2aa-expressing strains, but there was no difference between TC.AM14a and B6.AM14a mice (Fig. 7C). In contrast, the number of EF foci was significantly higher in TC.AM14a spleens than in the three other strains (Fig. 7D). Finally, among the 31 AM14 tg mice scored by histology in this study, there was a strong correlation (Pearson’s R = 0.5173, p = 0.0005) between their EF score and the number of Id+ AFCs.

The relative participation of Id+ cells to GCs was further investigated by flow cytometry (Fig. 7E). Confirming the histology results, a significantly higher percentage and number of total GC B cells was found in TC.AM14a mice (Fig. 7F). Within these GC B cells, however, the percentage of Id+ GC B cells was significantly lower in TC.AM14a mice than in B6.AM14a mice, and the absolute numbers of Id+ GC B cells were similar between these two strains (Fig. 7G). Accordingly, the percentage of Id+ GC B cells determined by flow cytometry as PNA+ cells was significantly lower than the percentage of PNA+ Id− B cells in TC.AM14a spleens (7.13 ± 1.73 vs. 15.87 ± 3.73, p = 0.04). These results indicate that autoreactive Id+ B cells were relatively excluded from GCs as compared to Id− B cells in TC.AM14a mice. Furthermore, the number of Id+ GCs was positively correlated with the percentage of total AM14 Id+ B cells (p = 0.006) and the percentage of intracellular iId+ B cells (p = 0.01) determined by flow cytometry. There was no correlation, however, between the presence or the number of Id+ GCs (either by histology or flow cytometry) and Id+ RF production (either by ELISPOT or by ELISA). Overall, these results showed that, although some Id+ B cells reach the GCs, Id+ RF Ab production correlates with the presence of large EF foci. These results are consistent with the predominant source of RF Ab being short-lived PBs in TC.AM14a mice, as it was previously shown in the MRL/lpr mice.

Activation of AM14+ RF B cells in the TC genetic background requires dual BCR and TLR ligation

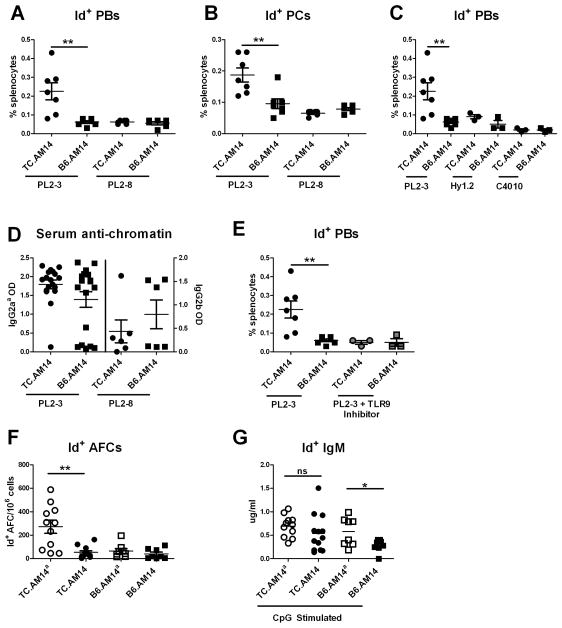

In vitro analyses have shown that AM14 Id+ B cell activation and differentiation into AFC required dual BCR and TLR7/9 ligation (8). This requirement was confirmed in vivo in the MRL and BALB/c backgrounds by direct exposure of AM14 tg mice to Abs of the a or b allotype specific for autoAg activating the TLR7/9 pathway (i.e. anti-chromatin Abs) (9). Using the same model, 2 months old TC.AM14 and B6.AM14 mice were immunized with hybridomas secreting Abs of varying specificities and allotypes, and sacrificed one week later. These young mice did not express the IgG2aa autoAg and did not show any sign of spontaneous Id+ B cell activation (data not shown). The PL2-3 clone secreting anti-chromatin IgG2aa represents a cognate Ag for the Id+ B cells and ligates TLR9 and TLR7 through the binding of endogenous chromatin which presumably also contains associated RNA (8). The PL2-8 secreting anti-chromatin IgG2b cannot bind the Id+ BCR and thus neither provides cross-linking nor the ability to internalize self-chromatin. PL2-3 hybridoma injections induced Id+ B cell differentiation to both the PB (Fig. 8A) and PC (Fig. 8B) stages in TC.AM14 mice, but not in B6.AM14 mice. PL2-8 injections, however, failed to induce the differentiation of Id+ B cells in either strain.

Figure 8. Induced AM14 Id+ B cell activation requires dual BCR and TLR ligation in the TC genetic background.

TC.AM14 and B6.AM14 mice pre-treated with pristane were injected with hybridomas. The differentiation of Id+ B cells was analyzed one week later by flow cytometry. Percentage of splenic mId+ iId+ PBs (A) and mId− iId+ (B) PCs after immunization with IgG2aa (PL2-3) or IgG2b (PL2-8) anti-chromatin secreting hybridomas. C. Percentage of splenic mId+ iId+ PBs after immunization with non-TLR activating hybridomas Hy1.2 (IgG2aa anti-TNP) and C4010 (IgG2ab anti-TNP) as compared to PL2-3. D. IgG2aa or IgG2b anti-chromatin secretion by the injected hybridomas was measured by ELISAs in the serum of recipient mice. E. Percentage of splenic mId+ iId+ PBs in mice treated with PL2-3 and a TLR9 antagonist as compared to PL2-3 alone. Id+ IgM secretion from the splenocytes of untreated 7 months old mice was evaluated ex vivo by ELISPOT (F) and by ELISA (G) following 5 d stimulation with 1 ug/ml CpG. Significance levels of Mann-Whitney tests are shown.

Injections of the anti-TNP IgG2aa Hy1.2 hybridoma, which binds the Id+ BCR (albeit without crosslinking) but does not bind nucleic acid and cannot mediate TLR7/9 activation, did not activate Id+ B cells in TC.AM14 mice (Fig. 8C), as expected. The results obtained with Hy1.2 injections were similar to those obtained with anti-TNP IgG2ab C4010 hybridoma, which cannot bind either Id+ BCR or activate TLRs (Fig. 8C). Therefore, a combination of BCR and TLR ligation in a single antigenic particle could stimulate Id+ B cells to express intracellular Id+ on the TC genetic background. However, the differentiation process was blocked before the Ab secretion stage, since we did not detect Id+ RF production in hybridoma-immunized mice either by serum ELISA or ELISPOTs (data not shown). Longer in vivo exposure to the hybridomas (up to 2 weeks) and higher numbers of hybridomas yielded similar results. Moreover, unlike in BALB/c mice (9), anti-chromatin IgG2aa hybridomas were not able to activate Id+ B cells in B6 mice. High levels of anti-chromatin IgG2aa were found in 13/14 TC.AM14 mice and in 13/18 B6.AM14 injected with PL2-3 (Fig. 8D), and there was no correlation between the amount of serum anti-chromatin IgG2aa and the expansion of iId+ B cells in any of these mice, thus excluding inadequate exposure to self-Ag as the cause of failure to respond in the B6 background. Anti-chromatin IgG2b, anti-TNP IgG2aa and IgG2ab were found at similar levels in TC.AM14 and B6.AM14 mice after PL2-8 (Fig. 8D), Hy1.2 or C4010 injections, respectively (data not shown).

Immunizing TC.AM14 mice with three doses of 1 mg/ml purified PL2-3 Ab either with or without pristane pre-treatment did not duplicate the Id+ B cell activation induced by the PL2-3 hybridoma (data not shown), although this regimen induced Id+ RF B cells to differentiate into AFCs in BALB/c mice (9). Notably, serum anti-chromatin IgG2aa was not detected in mice immunized with purified PL2-3 Ab did not produce any detectable (data not shown), as it was in mice immunized with PL2-3 hybridomas (Fig. 8D). This could be due to either that the B6 genetic background required a greater amount of purified Ab to activate Id+ RF B cells or that the hybridomas delivers the Ag in a manner that is necessary for Id+ RF B cell activation on the B6 background. In either case, this result emphasizes the role of the genetic background in Id+ RF B cell activation.

Given that chromatin is a ligand for TLR9, we blocked TLR9 signaling by co-injecting mice with PL2-3 and a TLR9 antagonist. The TLR9 antagonist inhibited RF Id+ activation in TC.AM14 mice (Fig. 8E) despite the presence of high levels of IgG2aa anti-chromatin Abs in their sera (data not shown). These results demonstrated that TLR9 activation is required for Id+ RF activation by IgG2aa anti-chromatin ICs in TC.AM14 mice. This is consistent with the known dependency of AM14 B cell activation by PL2-3 on TLR9 in the MRL strain background (9) as well as in vitro (8). Unfortunately, there is no TLR7-specific inhibitor that would allow the evaluation of this pathway in a similar experiment.

To investigate whether exogenous TLR9 could rescue the absence of autoAg, we compared ex vivo Id+ AFCs with Id+ IgM produced by splenocytes from the same 7 months old mice after in vitro stimulation with CpG. As previously shown, ex vivo Id+ AFCs were found only in TC.AM14a mice (Fig. 8F). However, RF Id+ IgM secretion could be detected in the supernatant of CpG-stimulated splenocytes for all four strains. TLR9 stimulation of TC.AM14 splenocytes could overcome the lack of autoAg and induce Ab secretion comparable to that of TC.AM14a splenocytes (Fig. 8G). In comparison, TLR9 stimulation could not overcome the absence of the autoAg in B6.AM14 splenocytes, which secreted significantly lower amount of Id+ IgM than in B6.AM14a stimulated splenocytes. Furthermore, in vitro stimulation with the TLR4 ligand LPS could not enhance RF Ab secretion in the absence of the autoAg in the TC background (data not shown). Therefore, these results support a model of dual BCR and TLR9 activation for the breakdown in tolerance of RF B cells in a lupus-prone background.

Discussion

AutoAbs of the RF specificity have been found in several autoimmune diseases such as SLE, Sjogren’s syndrome, and rheumatoid arthritis and the presence of RFs in lupus patients has been associated with active disease (3). RFs have also been found in the MRL/lpr mouse model of lupus (30). Here we show that RFs are part of the autoAb repertoire of the lupus-prone NZM2410 model, which has an entirely different genetic background than the MRL/lpr mouse, suggesting that the production of autoAbs directed at immunoglobulins is a general feature of systemic humoral immunity. Furthermore, studies showed that the AM14 tg B cells were activated in vitro and in vivo by IgG2aa anti-chromatin ICs (8, 9), extending the relevance of the AM14 model to low-affinity anti-nuclear Ab producing B cells that are characteristic of systemic autoimmune diseases such as SLE (1).

Due to the complex nature of this disease, genetic predisposition in both humans and mice has been attributed to multiple susceptibility loci, only some of which are shared among affected individuals (35, 36). It is unknown if these different genetic backgrounds result in different mechanisms by which B cell tolerance is broken and by which autoreactive B cells are activated. The MRL/lpr and NZM2410 strains are two well-characterized models of systemic lupus that do not share an essential lupus susceptibility locus (35) Shared signaling networks have been identified in B cells among lupus prone mice, including NZM2410 and MRL/lpr (37). Whether these activation pathways lead to shared B cell tolerance and activation mechanisms has been unknown. The AM14 model was an ideal system to address the question. In addition to its high degree of relevance to SLE, it is dependent on the production of anti-chromatin IgG, which occurs at high level in both strains. We found that, as for MRL/lpr, the TC genetic background supported the activation and differentiation of AM14 B cells into Ab producing cells. The evaluation of the mechanisms by which this occurs revealed many similarities between the two genetic backgrounds, as well as some differences.

First, we showed that the TC genetic background promotes the spontaneous activation of AM14 RF B cells in the presence of the IgG2aa autoAg. Thus, the expression of Sle1, Sle2, and Sle3 is sufficient to mediate AM14 B cell activation and differentiation into AFCs, just as in the MRL/lpr genetic background. Similarly to BALB/c, the B6 genetic background does not promote AM14 B cell activation. However, the presence of the autoAg has no effect on the surface expression of IgMa in BALB/c mice (2), but not in the B6 background as IgMa expression was higher in B6.AM14 than in B6.AM14a mice. Since IgM downregulation is a characteristic of anergized cells (31), this suggests that unlike BALB/c autoreactive AM14 B cells which are clonally ignorant (4), the B6 autoreactive AM14 B cells may be somewhat anergized by the autoAg. Extensive studies of BCR activation will be needed to further characterize this. Nevertheless, this putative tolerance mechanism is disrupted by the TC autoimmune background, as IgMa expression was similar between TC.AM14a and TC.AM14 mice.

In addition, our results suggest that autoreactive AM14 B cells are not clonally ignorant in TC lupus-prone mice, and that tolerance mechanisms may be breached early in peripheral differentiation. The presence of the autoAg resulted in the accumulation of Id+ B cells in the T1 subset in both autoimmune and non-autoimmune strains. Given that the T1 subset is a tolerance checkpoint where autoreactive cells are eliminated (32), our results indicate the presence of a T1 tolerance checkpoint for autoreactive AM14 B cells in both B6 and TC mice. However, since there were relatively more Id+ B cells in the T2 stage in the TC strains, this suggests the T1 tolerance checkpoint, while present, may not be as effective in TC mice. This was further shown by the relative decreased recruitment of Id+ B cells in the T3 subset, traditionally associated with anergy (33), in the TC but not B6 background in the presence of the autoAg. Thus our results suggest the presence of active peripheral tolerance checkpoints taking place in the regulation of AM14 B cells in B6 mice that are defective in TC mice.

The second important similarity between the TC and MRL/lpr models is the utilization of the EF pathway for AM14 Id+ B cell activation. Intracellular Id+ B cells were most frequently found in foci in the red pulp, and the abundance of these foci was positively correlated with the production of Id+ RF. Furthermore, as in MRL/lpr, a combination of surface marker expression, BrdU incorporation, and adoptive transfers have shown that Id+ RF is produced by short-lived PBs in TC mice. Some Id+ AFCs were also found in the TC.AM14a BM (data not shown), but adoptive transfers showed that they were not long-lived. NZB/WF1 and TC mice produce long-lived BM anti-dsDNA AFCs in addition to numerous splenic PBs (12, 38). Detailed kinetic studies of AM14 B cell differentiation into AFCs relative to B cells with other specificities such as anti-DNA will be necessary to assess the relative contribution of the short-lived and long-lived pathways in TC.AM14a mice, as well as the factors that favor one over the other. Overall these results confirm the hypothesis that the EF/PB route is a primary differentiation pathway for autoreactive B cells that are activated in a TLR-dependent manner (1, 9–11). The generalization of this finding in vivo to a second well-characterized model of lupus is an important contribution of the work reported here.

A difference between the MRL/lpr and TC background is the presence of Id+ B cells in splenic GCs of TC mice, which was not observed in MRL/lpr spleens (10). Several results, however, suggested that the GC pathway is not involved in the production of Id+ RF. First, flow cytometry results showed that there was a lower percentage of Id+ cells than Id− cells in the GCs, indicating that Id+ B cells were relatively excluded from GCs. Second, the abundance of Id+ GC B cells was positively correlated with the abundance of total Id+ B cells, but not with the level of Id+ RF production, suggesting a non-specific GC route for Id+ B cells in TC.AM14a mice. Third, the lack of long-lived RF AFCs in the BM argues against GCs being the source of AFCs, as their typical output includes long-lived AFCs (39). Validation of this hypothesis will require careful Vκ8 sequence comparison from Id+ B cells picked from GCs and EF foci. A limitation of the AM14 HC tg model that we used here is that it only produces IgM autoAb, which are different from the class-switched autoAbs found in lupus. Recent studies have shown that a large percentage of IgM+ B cells participate in GC reactions (40), suggesting that the relative exclusion of Id+ IgM+ B cells from GCs in TC.AM14a mice may be representative of all B cells with the same specificity. We cannot exclude, however, that different results would be obtained with class-switched Id+ B cells.

Finally, as in the MRL/lpr model (9), dual ligation of BCR and TLR was required to induce RF activation for TC.AM14 mice in vivo. This was shown by the need for an anti-chromatin that could bind the AM14 BCR along with the inhibition of the positive response to PL2-3 by a TLR9 inhibitor. Therefore, a major contribution of the MRL/lpr and TC lupus backgrounds to AM14 B cell activation is the production of high levels of IgG anti-nuclear Abs (18, 41). In vitro studies have shown that either TLR7 or TLR9 receptor engagement was capable of inducing AM14 B cell activation in combination with BCR ligation (7, 42). Given that the Sle1 locus is linked to the production of anti-chromatin Abs (19) and that TC mice do not produce autoAbs with RNA specificities, we focused on the importance of TLR9 in AM14 B cell activation. In addition to the in vivo inhibitor studies, in vitro cultures with CpG compensated for the absence of the IgG2aa autoAg in TC.AM14 mice resulting in secretion of Id+ Abs to levels comparable to TC.AM14a mice. These results revealed a necessary role for TLR9 in the AM14 response in TC mice, although we cannot exclude at this point that TLR7 also plays a role in RF activation.

A major difference between our system and prior reports was that the transfers of the PL2-3 hybridoma, which ligated both BCR and TLR7/9 of TC.AM14 Id+ B cells, was not sufficient to induce full-fledged differentiation into Ab secreting cells, as it did on the MRL and BALB/c backgrounds (9); nonetheless PB and PC differentiation was observed by flow cytometry. Furthermore, B6.AM14 mice were refractory to PL2-3 activation of Id+ B cells to express intracellular immunoglobulin. As with the downregulation of IgMa expression, these results suggest a tolerogenic effect of the B6 background despite the presence of self-reactive B cells. Thus, this further highlights the role of the genetic background, including the Sle lupus susceptibility loci, in promoting the activation of autoreactive Id+ B cells in the presence of BCR/TLR dual ligation.

In summary, our results suggest a multi-step regulation for the AM14 response in TC mice in which the genetic backgrounds (independently B6 and the Sle loci), autoAg, TLR9, and chronic stimulation each play a role. First, the B6 background tolerizes the AM14 B cells to a greater extent than the BALB/c background through unknown mechanisms that may include anergy. The expression of the Sle1, Sle2, and Sle3 susceptibility loci breaks Id+ B cell tolerance in the presence of autoAg and TLR9 ligation, in a progressive process as the mice age. The expression of these susceptibility loci also favors Ab producing cell differentiation, regardless of autoAg stimulation, and on this genetic background, a strong TLR9 stimulation can compensate for the absence of autoAg. The fact that in young mice, a strong dual ligation of BCR and TLR9 ligation led the TC.AM14 Id+ B cell to an initial activation and differentiation but not to the terminal differentiation into Ab secreting cells suggest the existence of a check point that can be breached only by a chronic long-term activation that occurred in aged TC.AM14a mice. Additional work will characterize the role of individual Sle loci and identify susceptibility genes involved in the activation of AM14 B cells in the TC model.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The NIM-R6 clone of anti-CD22 Ab was a kind gift from Michael E. Parkhouse, Instituto Gulbenkian de Ciencias, Oeiras, Portugal. We would like to thank Drs. Eric Sobel, Clayton Mathews, Minoru Satoh and Jeffrey Harrison for helpful discussions, as well as Leilani Zeumer and Nathalie Kanda for the production and maintenance of the AM14 Tg mice.

Abbreviations

- Ab

antibody

- AFC

antibody forming cell

- Ag

antigen

- EF

extra-follicular

- GC

germinal center

- IC

immune complex

- HC

immunoglobulin heavy chain

- iId+

intracellular Id+

- mId+

membrane Id+

- PB

plasmablast

- PC

plasma cell

- RF

rheumatoid factor

- SHM

somatic hypermutation

- SLE

systemic lupus erythematosus

- TC

B6.NZM2410.Sle1.Sle2.Sle3

- tg

transgene

Footnotes

This research was supported by National Institutes of Health grants F31 AI094925 to AS, RO1 A058150 to LM, and RO1 AI073722 to MJS.

References

- 1.Shlomchik MJ. Sites and stages of autoreactive B cell activation and regulation. Immunity. 2008;28:18–28. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2007.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Shlomchik M, Zharhary D, Saunders T, Camper S, Weigert M. A rheumatoid factor transgenic mouse model of autoantibody regulation. Int Immunol. 1993;5:1329–1341. doi: 10.1093/intimm/5.10.1329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kessel A, Rosner I, Halasz K, Grushko G, Shoenfeld Y, Paran D, Toubi E. Antibody clustering helps refine lupus prognosis. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2009;39:66–70. doi: 10.1016/j.semarthrit.2008.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hannum LG, Ni D, Haberman AM, Weigert MG, Shlomchik MJ. A disease-related rheumatoid factor autoantibody is not tolerized in a normal mouse: implications for the origins of autoantibodies in autoimmune disease. J Exp Med. 1996;184:1269–1278. doi: 10.1084/jem.184.4.1269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wang H, Shlomchik M. Autoantigen-specific B cell activation in Fas-deficient rheumatoid factor immunoglobulin transgenic mice. J Exp Med. 1999;190:639–649. doi: 10.1084/jem.190.5.639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Busconi L, Bauer J, Tumang J, Laws A, Perkins-Mesires K, Tabor A, Lau C, Corley R, Rothstein T, Lund F, Behrens T, Marshak-Rothstein A. Functional outcome of B cell activation by chromatin immune complex engagement of the B cell receptor and TLR9. J Immunol. 2007;179:7397–7405. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.179.11.7397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lau CM, Broughton C, Tabor AS, Akira S, Flavell RA, Mamula MJ, Christensen SR, Shlomchik MJ, Viglianti GA, Rifkin IR, Marshak-Rothstein A. RNA-associated autoantigens activate B cells by combined B cell antigen receptor/Toll-like receptor 7 engagement. J Exp Med. 2005;202:1171–1177. doi: 10.1084/jem.20050630. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Leadbetter EA, I, Rifkin R, Hohlbaum AM, Beaudette BC, Shlomchik MJ, Marshak-Rothstein A. Chromatin-IgG complexes activate B cells by dual engagement of IgM and Toll-like receptors. Nature. 2002;416:603–607. doi: 10.1038/416603a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Herlands R, William J, Hershberg U, Shlomchik M. Anti-chromatin antibodies drive in vivo antigen-specific activation and somatic hypermutation of rheumatoid factor B cells at extrafollicular sites. Eur J Immunol. 2007;37:3339–3351. doi: 10.1002/eji.200737752. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.William J, Euler C, Christensen S, Shlomchik M. Evolution of autoantibody responses via somatic hypermutation outside of germinal centers. Science. 2002;297:2066–2070. doi: 10.1126/science.1073924. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.William J, Euler C, Shlomchik MJ. Short-lived plasmablasts dominate the early spontaneous rheumatoid factor response: differentiation pathways, hypermutating cell types, and affinity maturation outside the germinal center. J Immunol. 2005;174:6879–6887. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.174.11.6879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hoyer BF, Moser K, Hauser AE, Peddinghaus A, Voigt C, Eilat D, Radbruch A, Hiepe F, Manz RA. Short-lived plasmablasts and long-lived plasma cells contribute to chronic humoral autoimmunity in NZB/W mice. J Exp Med. 2004;199:1577–1584. doi: 10.1084/jem.20040168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Vinuesa CG, Sanz I, Cook MC. Dysregulation of germinal centres in autoimmune disease. Nat Rev Immunol. 2009;9:845–857. doi: 10.1038/nri2637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Thien M, Phan TG, Gardam S, Amesbury M, Basten A, Mackay F, Brink R. Excess BAFF rescues self-reactive B cells from peripheral deletion and allows them to enter forbidden follicular and marginal zone niches. Immunity. 2004;20:785–798. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2004.05.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kelley VE, Roths JB. Interaction of mutant lpr gene with background strain influences renal disease. Clin Immunol Immunopath. 1985;37:220–229. doi: 10.1016/0090-1229(85)90153-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Vidal S, Kono D, Theofilopoulos A. Loci predisposing to autoimmunity in MRL-Fas lpr and C57BL/6-Faslpr mice. J Clin Invest. 1998;101:696–702. doi: 10.1172/JCI1817. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Teachey D, Seif A, Grupp S. Advances in the management and understanding of autoimmune lymphoproliferative syndrome (ALPS) Br J Haematol. 2010;148:205–216. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2009.07991.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Morel L, Croker BP, Blenman KR, Mohan C, Huang G, Gilkeson G, Wakeland EK. Genetic reconstitution of systemic lupus erythematosus immunopathology with polycongenic murine strains. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2000;97:6670–6675. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.12.6670. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mohan C, Alas E, Morel L, Yang P, Wakeland E. Genetic dissection of SLE pathogenesis. Sle1 on murine chromosome 1 leads to a selective loss of tolerance to H2A/H2B/DNA subnucleosomes. J Clin Invest. 1998;101:1362–1372. doi: 10.1172/JCI728. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kumar K, Li L, Yan M, Bhaskarabhatla M, Mobley A, Nguyen C, Mooney J, Schatzle J, Wakeland E, Mohan C. Regulation of B cell tolerance by the lupus susceptibility gene Ly108. Science. 2006;312:1665–1669. doi: 10.1126/science.1125893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mohan C, Morel L, Yang P, Wakeland E. Genetic dissection of systemic lupus erythematosus pathogenesis: Sle2 on murine chromosome 4 leads to B cell hyperactivity. J Immunol. 1997;159:454–465. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Liu Y, Li L, Kumar K, Xie C, Lightfoot S, Zhou X, Kearney J, Weigert M, Mohan C. Lupus susceptibility genes may breach tolerance to DNA by impairing receptor editing of nuclear antigen-reactive B cells. J Immunol. 2007;179:1340–1352. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.179.2.1340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sobel E, Morel L, Baert R, Mohan C, Schiffenbauer J, Wakeland E. Genetic dissection of systemic lupus erythematosus pathogenesis: evidence for functional expression of Sle3/5 by non-T cells. J Immunol. 2002;169:4025–4032. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.169.7.4025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mohan C, Yu Y, Morel L, Yang P, Wakeland E. Genetic dissection of Sle pathogenesis: Sle3 on murine chromosome 7 impacts T cell activation, differentiation, and cell death. J Immunol. 1999;162:6492–6502. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wakui M, Kim J, Butfiloski E, Morel L, Sobel E. Genetic dissection of lupus pathogenesis: Sle3/5 impacts IgH CDR3 sequences, somatic mutations, and receptor editing. J Immunol. 2004;173:7368–7376. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.173.12.7368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Torres RM, Law CL, Santos-Argumedo L, Kirkham PA, Grabstein K, Parkhouse RM, Clark EA. Identification and characterization of the murine homologue of CD22, a B lymphocyte-restricted adhesion molecule. J Immunol. 1992;149:2641–2649. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nitschke L, Lajaunias F, Moll T, Ho L, Martinez-Soria E, Kikuchi S, Santiago-Raber ML, Dix C, Parkhouse RM, Izui S. Expression of aberrant forms of CD22 on B lymphocytes in Cd22a lupus-prone mice affects ligand binding. Int Immunol. 2006;18:59–68. doi: 10.1093/intimm/dxh349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.William J, Euler C, Leadbetter E, Marshak-Rothstein A, Shlomchik M. Visualizing the onset and evolution of an autoantibody response in systemic autoimmunity. J Immunol. 2005;174:6872–6878. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.174.11.6872. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Martino AT, Herzog RW, Anegon I, Adjali O. Measuring immune responses to recombinant AAV gene transfer. Methods Mol Biol. 2011;807:259–272. doi: 10.1007/978-1-61779-370-7_11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wolfowicz CB, Sakorafas P, Rothstein TL, Marshak-Rothstein A. Oligoclonality of rheumatoid factors arising spontaneously in lpr/lpr mice. Clin Immunol Immunopathol. 1988;46:382–395. doi: 10.1016/0090-1229(88)90057-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Goodnow CC, Crosbie J, Adelstein S, Lavoie TB, Smith-Gill SJ, Brink RA, Pritchard-Briscoe H, Wotherspoon JS, Loblay RH, Raphael K. Altered immunoglobulin expression and functional silencing of self-reactive B lymphocytes in transgenic mice. Nature. 1988;334:676–682. doi: 10.1038/334676a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tussiwand R, Bosco N, Ceredig R, Rolink AG. Tolerance checkpoints in B-cell development: Johnny B good. Eur J Immunol. 2009;39:2317–2324. doi: 10.1002/eji.200939633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Merrell KT, Benschop RJ, Gauld SB, Aviszus K, Cote-Ricardo D, Wysocki LJ, Cambier JC. Identification of anergic B cells within a wild-type repertoire. Immunity. 2006;25:953–962. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2006.10.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.William J, Euler C, Primarolo N, Shlomchik M. B cell tolerance checkpoints that restrict pathways of antigen-driven differentiation. J Immunol. 2006;176:2142–2151. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.176.4.2142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Morel L. Genetics of SLE: evidence from mouse models. Nat Rev Rheumatol. 2010;6:348–357. doi: 10.1038/nrrheum.2010.63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Deng Y, Tsao BP. Genetic susceptibility to systemic lupus erythematosus in the genomic era. Nat Rev Rheumatol. 2010;6:683–692. doi: 10.1038/nrrheum.2010.176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wu T, Qin X, Kurepa Z, Kumar KR, Liu K, Kanta H, Zhou XJ, Satterthwaite AB, Davis LS, Mohan C. Shared signaling networks active in B cells isolated from genetically distinct mouse models of lupus. J Clin Invest. 2007;117:2186–2196. doi: 10.1172/JCI30398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Niu H, Sobel ES, Morel L. Defective B-cell response to T-dependent immunization in lupus-prone mice. Eur J Immunol. 2008;38:3028–3040. doi: 10.1002/eji.200838417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Shlomchik MJ, Weisel F. Germinal center selection and the development of memory B and plasma cells. Immunol Rev. 2012;247:52–63. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065X.2012.01124.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Taylor JJ, Jenkins MK, Pape KA. Heterogeneity in the differentiation and function of memory B cells. Trends Immunol. 2012;33:590–597. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2012.07.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Izui S, Kelley V, Masuda K, Yoshida H, Roths J, Murphy E. Induction of various autoantibodies by mutant gene lpr in several strains of mice. J Immunol. 1984;133:227–233. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Viglianti G, Lau C, Hanley T, Miko B, Shlomchik M, Marshak-Rothstein A. Activation of autoreactive B cells by CpG dsDNA. Immunity. 2003;19:837–847. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(03)00323-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.