Abstract

MenB, the 1,4-dihydroxy-2-naphthoyl-CoA synthase from the bacterial menaquinone biosynthesis pathway, catalyzes an intramolecular Claisen condensation (Dieckmann reaction) in which the electrophile is an unactivated carboxylic acid. Mechanistic studies on this crotonase family member have been hindered by partial active site disorder in existing MenB X-ray structures. In the current work the 2.0 Å structure of O-succinylbenzoyl-aminoCoA (OSB-NCoA) bound to the MenB from Escherichia coli provides important insight into the catalytic mechanism by revealing the position of all active site residues. This has been accomplished by the use of a stable analogue of the O-succinylbenzoyl-CoA (OSB-CoA) substrate in which the CoA thiol has been replaced by an amine. The resulting OSB-NCoA is stable and the X-ray structure of this molecule bound to MenB reveals the structure of the enzyme-substrate complex poised for carbon-carbon bond formation. The structural data support a mechanism in which two conserved active site Tyr residues, Y97 and Y258, participate directly in the intramolecular transfer of the substrate α-proton to the benzylic carboxylate of the substrate, leading to protonation of the electrophile and formation of the required carbanion. Y97 and Y258 are also ideally positioned to function as the second oxyanion hole required for stabilization of the tetrahedral intermediate formed during carbon-carbon bond formation. In contrast, D163, which is structurally homologous to the acid-base catalyst E144 in crotonase, is not directly involved in carbanion formation and may instead play a structural role by stabilizing the loop that carries Y97. When similar studies were performed on the MenB from Mycobacterium tuberculosis, a twisted hexamer was unexpectedly observed, demonstrating the flexibility of the interfacial loops that are involved in the generation of the novel tertiary and quaternary structures found in the crotonase superfamily. This work reinforces the utility of using a stable substrate analogue as a mechanistic probe in which only one atom has been altered leading to a decrease in α-proton acidity.

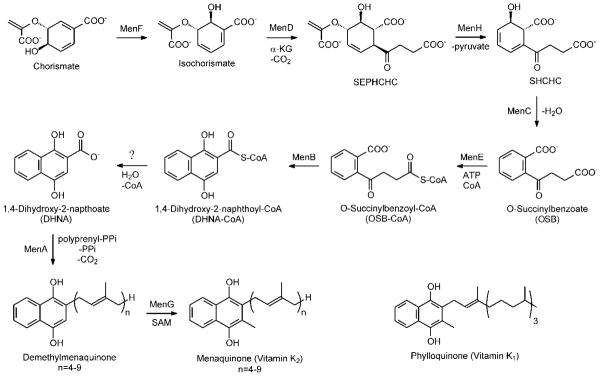

Menaquinone (vitamin K2; Figure 1) is a polyisoprenylated naphthoquinone that functions as a redox active cofactor in the electron transport chain of most Gram positive and some Gram negative bacteria (1–2). Although humans utilize menaquinone and the related naphthoquinone vitamin K1 (phylloquinone; Figure 1) for the γ-carboxylation of glutamate residues (3–4), mammalian cells are unable to undertake the de novo synthesis of menaquinone, and thus bacterial enzymes in the menaquinone biosynthesis pathway are potential targets for antibacterial drug discovery (5–8).

Figure 1.

The menaquinone biosynthesis pathway and the structure of phylloquinone

The biosynthesis of menaquinone from chorismate was originally elucidated in Escherichia coli, Bacillus subtilis and Mycobacterium phlei (9–10) and recently refined by Jiang et al. (11–12) (Figure 1). A key step in this pathway is the reaction catalyzed by the 1,4-dihydroxynaphthoyl-CoA synthase (MenB) in which the second naphthoquinone aromatic ring is formed through an intramolecular Claisen (or Dieckmann) condensation involving the succinyl side chain of O-succinylbenzoate (OSB) (8, 13–14). In Claisen condensations, such as that catalyzed by the β-ketoacyl-ACP synthases, normally both nucleophile and electrophile are activated through the formation of thioesters (15–16). However, the MenB reaction is an unusual one since only the nucleophile is activated (8).

MenB is a member of the crotonase superfamily in which a common theme is the stabilization of a CoA thioester oxyanion intermediate by an oxyanion hole (16–20). This structural feature is conserved in MenB where it plays a critical role by acidifying the OSB-CoA α-protons and promoting carbanion formation (8). However the identity of the base that abstracts the α-proton has still not been fully resolved. The mechanism originally proposed by our group involved an intramolecular proton transfer from C2 to the OSB carboxylate resulting in carbanion formation and also leading to protonation of the acid, thus making it a better electrophile (8). In contrast, more recently it has been suggested that an active site Asp or a bicarbonate cofactor functions as the base (21). In addition, by analogy with enzymes such as the β-ketoacyl-ACP synthases (16), a second oxyanion hole must be present in the active site to stabilize the tetrahedral oxyanion intermediate formed by carbon-carbon bond formation. However the identity of this second oxyanion hole, which is not normally a feature of crotonase superfamily members, is an open question.

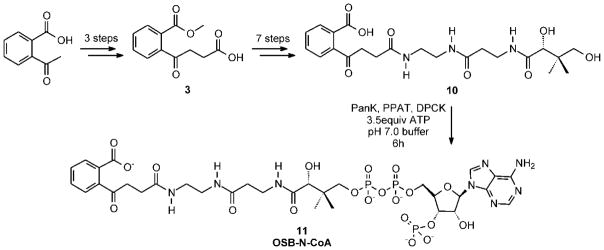

Our ability to fully elucidate the mechanism of MenB and address the questions raised above has been hindered by the lack of structural data in which the MenB active site is intact. Currently structures exist of the MenB enzymes from Mycobacterium tuberculosis (mtMenB, 1Q51, 1RJN; (8, 22)), Staphylococcus aureus (saMenB, 2UZF; (23)), Salmonella typhimurium (stMenB 3H02; (24)) and Geobacillus kaustophilus (gkMenB, 2IEX; (25)). However in each case a portion of the MenB active site is disordered. This region displays variability in sequence even within the MenB family and also little conservation in structure throughout the crotonase superfamily, which has hindered our attempts to use sequence homology to predict the function of amino acids in this part of the active site. Although several of these enzymes were crystallized in the presence of acyl-CoA ligands, including the product of the reaction, only in the case of acetoacetyl-CoA can the acyl group be visualized. We hypothesized that a stable analogue of the substrate that retained all enzyme-substrate interactions would make an ideal structural probe and consequently we used a chemoenzymatic approach to synthesize OSB-aminoCoA (OSB-NCoA) in which the thioester sulfur is replaced by a nitrogen. The resulting decrease in α-proton acidity resulting from conversion of the CoA thioester into an amide reduces the stability of the carbanion sufficiently so that the Claisen condensation reaction is prevented. Subsequent structural studies revealed that the OSB-NCoA successfully traps the previously disordered active site region in a well-defined conformation, providing valuable information on substrate recognition and the catalytic mechanism of this intriguing reaction.

Experimental Procedures

Chemicals were purchased from commercial suppliers (Sigma-Aldrich, Acros Organics, Alfa Aesar) and used without further purification. All solvents were purchased from Fisher Scientific. 1H-NMR spectral data were recorded on a Varian Gemini-2300 or Varian Inova-400 NMR spectrometer. Mass spectral data were obtained using an Agilent 1100 LS-MS electrospray ionization single quadrupole mass spectrometer. HPLC analysis was performed using a Shimadzu LC-10AVP chromatography system with an XTerra MS C18 reverse-phase column (4.6×100 mm, 3.5 μm) and by running a linear gradient of 0–100% solvent B (acetonitrile) in solvent A (5% acetic acid/H2O) over 20 min at a flow rate of 1ml/min.

Ligand synthesis

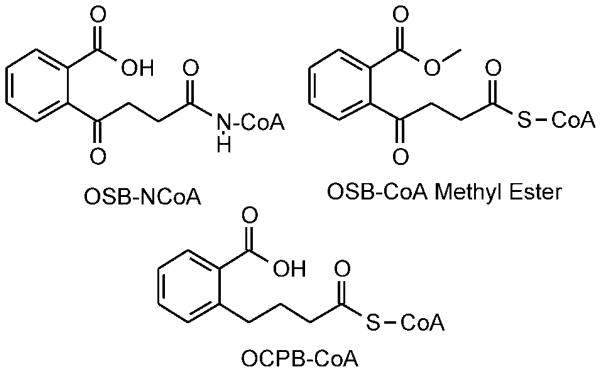

OSB-aminoCoA (OSB-NCoA; Figure 2) was synthesized chemoenzymatically according to the route shown in Scheme 1 (Figure S1). This method is based on the strategy employed for the synthesis of acyl-CoA analogues initially described by Drueckhammer (26–27) and employed by us for the synthesis of crotonyl-oxyCoA (28) in which the OSB-aminopantetheine is initially synthesized chemically and then converted to the final product using enzymes from the CoA biosynthetic pathway. OSB-CoA methyl ester and OCPB-CoA (Figure 2) were synthesized from the respective acids and CoA. A detailed description of the synthetic methods together with compound characterization is given in the supplementary information.

Figure 2.

OSB-CoA analogues

Scheme 1.

Preparation of wild-type and mutant MenB enzymes

The MenB enzyme from Mycobacterium tuberculosis (mtMenB) was expressed and purified as described previously (8). In order to obtain the corresponding enzyme from Escherichia coli (ecMenB), the E. coli menb gene b2262 (858 bp) was cloned into the pET-15b plasmid (Novagen) and placed in frame with an N-terminal His-tag sequence. Protein expression was performed using BL21 (DE3) E. coli cells essentially as described for mtMenB. A 1 l culture of cells was induced with 1 mM isopropyl-β-D-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG) at an OD600 of 0.8 and harvested by centrifugation after shaking for 12 h at 25°C. The cell pellet was then resuspended in 30 ml of His binding buffer (5 mM imidazole, 0.5 M NaCl, 20 mM Tris HCl, pH 7.9) and lysed by 3 passages through a French Press cell (1000 psi). Cell debris was removed by centrifugation at 33,000 rpm for 60 min at 4 °C. ecMenB was purified using His-tag affinity chromatography. The supernatant was loaded onto a His-bind column (1.5 cm × 15 cm) containing 4 ml of His-bind resin (Novagen) that had been charged with 9 ml of charge buffer (Ni2+). The column was washed with 60 ml of His-binding buffer and 30 ml of wash buffer (60 mM imidazole, 0.5 M NaCl, 20 mM Tris HCl, pH 7.9). Subsequently, the protein was eluted using a gradient of 20 ml elution buffer (60–500 mM imidazole, 0.5 M NaCl, 20 mM Tris HCl, pH 7.9). Fractions containing ecMenB were collected and the imidazole removed using a Sephadex G-25 chromatography column (1.5 cm × 55 cm) with a buffer containing 20 mM NaH2PO4, 0.1 M NaCl at pH 7.0 as eluent. The protein was found not to be stable with the His-tag, and therefore it was removed by treating the protein with biotinylated thrombin overnight at RT. After the biotinylated thrombin was captured with streptavidin agarose, the protein was concentrated using a Centricon-30 (Amicon) concentrator and stored at −80 °C. The concentration of ecMenB was determined by measuring the absorption at 280 nm and using an extinction coefficient of 36,040 M−1cm−1 calculated from the primary sequence. The purified protein was >95% pure on SDS-PAGE which gave an apparent MW of ~30 kDa.

Quikchange mutagenesis was used to prepare the D185E, D185G and S190A mutants of mtMenB and the Y97F and G156D mutants of ecMenB. These mutant proteins were expressed, purified and stored as described for the wild-type enzymes. The primers used to generate the mutants are given in the supporting information.

Crystallization, data collection and structure determination

apo-ecMenB and OSB-NCoA:ecMenB

Apo-ecMenB was crystallized using the sitting drop vapor diffusion technique. 0.5 μl of 350 μM protein solution was mixed with 0.5 μl of reservoir solution (200 mM sodium malonate at pH 7.0 and 20% PEG 3350, Hampton Research) and equilibrated against 75 μl of reservoir solution. Plates of 0.3 mm length in the longest dimension appeared in one day. The crystals were cryo-protected using a solution that contained 200 mM sodium malonate at pH 7.0, 21% PEG 3350, 25% glycerol and 20 mM NaH2PO4 at pH 7 and cryo-cooled in liquid nitrogen.

ecMenB in complex with OSB-NCoA was crystallized similarly using a sitting drop comprising 0.5 μl of 350 μM protein solution containing 1.7 mM of OSB-NCoA and 0.5 μl of reservoir solution (100 mM Bis-tris at pH 6.5, 200 mM NaCl and 25% PEG 3350, Hampton Research). Small bipyramids appeared in one day, and a long rod (0.6 mm in the long dimension) with a hollow core appeared in two days. The bipyramids did not improve and were not used for the diffraction experiment. A portion of the long rod was cryo-protected in a solution containing 100 mM Bis-Tris at pH 6.5, 200 mM NaCl, 26% PEG 3350, 25% glycerol, 20 mM NaH2PO4 at pH 7 and 200 μM OSB-NCoA, and cryo-cooled in liquid nitrogen.

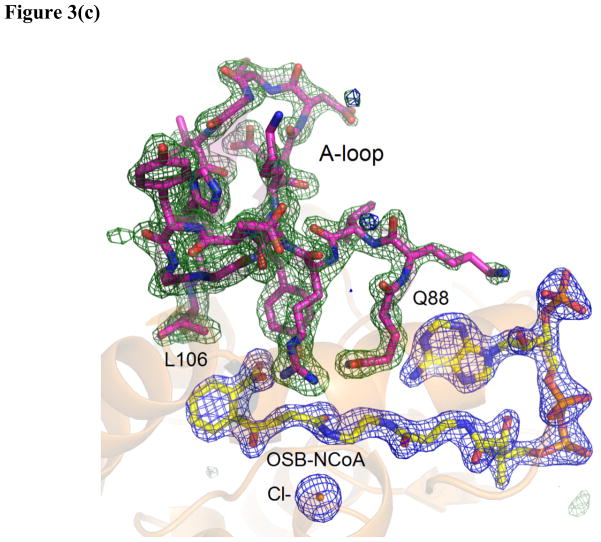

Data were collected at beamline X29 at the National Synchrotron Light Source (NSLS) in Brookhaven National Laboratory, indexed, integrated and scaled using HKL2000 (29). The binary structure was solved by MolRep (30) using the structure of MenB from Salmonella typhimurium (stMenB) as a search model (PDB code 3H02). Clear densities for OSB-NCoA and the missing residues 89–103 in the search model were revealed and built into the model. Residues in ecMenB inconsistent with the stMenB structure were fixed. Restraints for OSB-NCoA were generated by eLBOW (31) using the appropriate SMILES string (32) (see Supporting Information), and coordinates were refined in Phenix (33). Manual model building was performed in Coot (34). The density adjacent to G156 and the succinyl group of OSB-NCoA could not be simply accounted for by water. Modeling of a chloride ion present in the crystallization buffer eliminated the majority of the difference density. Several cycles of refinement followed by manual model building reduced both the working and free R factors significantly to below 20%. Densities for part of a PEG 3350 molecule (essentially three units of ethylene glycol) and glycerol from the cryo solution were found on the surface and were included in the structure. Protein geometry and all-atom contacts including added hydrogens were analyzed by MolProbity (35). Some Asn, Gln and His residues were subsequently flipped following this analysis. Although MolProbity suggested clashes between the OSB C2 and the oxygen attached to C7 in some monomers, the density map suggests that these atoms are indeed brought into close proximity. Statistics from diffraction data processing, model refinement and validation are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Data collection and refinement statistics

| ecMenB:OSB-NCoA | apo-ecMenB | mtMenB:OSB-NCoA | apo-mtMenB | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| PDB ID | 3T88 | 3T89 | 3T8A | 3T8B |

| Data Collection | ||||

| Space group | P21212 | P212121 | P6122 | R3 |

| Unit cell dimensions a, b, c (Å) | 140.49, 141.79, 89.12 | 76.51, 134.00, 153.36 | 87.13, 87.13, 414.84 | 132.23, 132.23, 71.14 |

| α, β, γ (°) | 90.00, 90.00, 90.00 | 90.00, 90.00, 90.00 | 90.00, 90.00, 120.00 | 90.00, 90.00, 120.00 |

| Redundancy | 6.9 (6.0) | 6.8 (6.5) | 15.2 (9.5) | 5.7 (5.6) |

| Completeness (%) | 99.8 (99.1) | 98.2 (95.8) | 99.6 (95.2) | 100.0 (100.0) |

| No. unique reflections | 120517 | 113570 | 45905 | 55893 |

| I/σI | 18.5 (2.4) | 17.1 (2.6) | 26.1 (3.4) | 21.2 (2.2) |

| Rmerge | 0.163 (0.674) | 0.101 (0.537) | 0.113 (0.542) | 0.083 (0.681) |

| Refinement | ||||

| Resolution range (Å) | 44.8-2.00 | 42.9-1.95 | 46.6-2.25 | 37.0-1.65 |

| No. atoms | 14295 | 12315 | 6066 | 3703 |

| Protein | 13004 | 11770 | 5883 | 3417 |

| Water | 811 | 449 | 107 | 280 |

| Ligands/ions | 480 | 96 | 76 | 6 |

| Average B factors | 22.4 | 27.1 | 37.9 | 21.9 |

| Protein | 21.9 | 27.0 | 37.7 | 21.2 |

| Waters | 26.6 | 29.3 | 34.3 | 31.2 |

| Ligands/ions | 28.4 | 31.6 | 62.2 | 21.7 |

| Rwork/Rfree | 0.155/0.195 | 0.186/0.219 | 0.194/0.237 | 0.141/0.187 |

| RMSD from ideal values in | ||||

| bond length (Å) | 0.008 | 0.005 | 0.007 | 0.004 |

| bond angle (°) | 1.2 | 0.84 | 0.95 | 0.83 |

Values for the highest resolution shell are given in parentheses.

mtMenB

A solution of 280 μM mtMenB was incubated with 3.7 mM OSB-NCoA for 1 h on ice. One μl of this protein solution was then mixed with 1 μl of reservoir solution containing 100 mM HEPES pH 8.0, 300 mM NaCl and 19% PEG 6000 and set up for hanging drop, vapor diffusion crystallization against 500 μl of reservoir solution at RT. The crystal grew into an irregular rod, 0.2 mm in the long dimension, and was cryo-cooled in liquid nitrogen on day 6 after stepwise transfer into a cryo solution containing 100 mM HEPES pH 8.0, 20 mM NaH2PO4 pH 7.0, 1 mM OSB-NCoA, 100 mM NaCl, 20% PEG 6000, and 22% glycerol. In a separate setup, 280 μM mtMenB was incubated with 1 mM OSB-NCoA for 40 min at RT after which 1 μl of this solution was mixed with 1 μl of reservoir solution containing 100 mM Tris pH 8.0, 200 mM Li2SO4 and 19% PEG 3350 and set up for hanging drop, vapor diffusion crystallization against 500 μl of reservoir solution at RT. Crystals of various shapes were obtained and cryo-cooled in liquid nitrogen on day 14 after soaking in a cryo solution containing 100 mM Tris pH 8.0, 200 mM Li2SO4, 23% PEG 3350, 22% glycerol, 20 mM NaH2PO4 pH 7.0 and 1 mM OSB-NCoA.

Diffraction data were collected at beamline X29 at the NSLS, indexed, integrated and scaled using HKL2000. Structure solutions were found by MolRep or Phaser (36) molecular replacement using the mtMenB structure 1Q51 as the search model (8). The same hexagonal crystal form was observed from both crystallization conditions, but an additional rhombohedral crystal form was obtained from the second condition. The rhombohedral structure was solved with two monomers in the asymmetric unit, but the second monomer was found by molecular replacement only after removing the C-terminal domain from the 1Q51 search model.

Enzyme kinetics

Steady-state kinetic parameters for ecMenB and mtMenB were determined in 20 mM Na2HPO4, 150 mM NaCl, 1 mM MgCl2, pH 7.0 buffer at 25 °C using a coupled assay (8). The formation of DHNA-CoA at 392 nm was monitored using a CARY-300 spectrophotometer, and reactions were initiated by addition of MenB to solutions containing OSB, ATP (120 μM), CoA (120 μM) and ecMenE (4 μM). The final assay volume was 500 μl. Kinetic parameters were calculated by fitting the initial velocity data to the Michaelis-Menten equation and using an extinction coefficient of 4, 000 M−1cm−1 for DHNA-CoA at 392 nm.

Results and Discussion

Active site disorder

MenB catalyzes an intramolecular Claisen condensation reaction in which the electrophile is an unactivated carboxylic acid. Apart from the oxyanion hole that stabilizes the carbanion (enolate) and which is a common feature of crotonase superfamily enzymes, insight into other aspects of the mechanism including α-proton abstraction, carbon-carbon bond formation and stabilization of the resulting tetrahedral oxyanion requires specific information on how the acyl portion of the substrate interacts with active site residues. Based on previous structures of mtMenB in complex with acetoacetyl-CoA and DHNA-CoA, L134, I136 and L137 have been suggested to make hydrophobic contacts with the aromatic ring of OSB while D185, A192, S190 and Y287 are potential proton donors and acceptors involved in the MenB reaction (8, 22). However the exact role that each residue plays in the reaction is difficult to determine given the active site disorder, which is normally observed in MenB X-ray structures and which, for mtMenB, includes residues 108–125 (the A-loop). Although the acyl group for acetoacetyl-CoA can be observed, this is a poor mimic of the natural substrate. In addition, the acyl group of the product, DHNA-CoA, cannot be observed most likely due to disorder. Nevertheless, we noticed that in the saMenB structure with acetoacetyl-CoA, only 8 residues (residues 79–86) were missing from the A-loop (23) presumably due to its shorter sequence in this nonconserved region. We therefore speculated that an acyl-CoA ligand that better mimicked the native substrate combined with a MenB enzyme with a shorter loop might increase the chance of revealing an intact active site together with details of the enzyme-substrate interactions.

The OSB-NCoA substrate analogue

We speculated that replacing the thioester in OSB-CoA with an amide would reduce α-proton acidity sufficiently to prevent formation of the carbanion required for carbon-carbon bond formation. This approach has previously been utilized in structural studies of succinyltransferase (37), while an acyl-CoA amide analogue has also been used to probe the mechanism of substrate recognition and catalysis by the crotonase superfamily member dihydroxyphenylglyoxylate synthase (DpgC) (38–40). In addition the amide analogue will be more stable to hydrolysis than the thioester counterpart, and so we prepared OSB-NCoA using the chemoenzymatic route described here. As anticipated, no reaction could be detected when OSB-NCoA was incubated with ecMenB or mtMenB even at high (100 μM) enzyme concentrations. We thus used OSB-NCoA as a ligand for co-crystallization with the two enzymes.

Structure of the ecMenB:OSB-NCoA complex

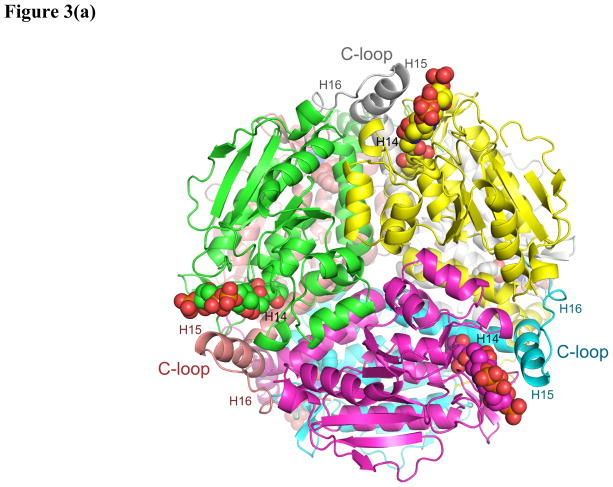

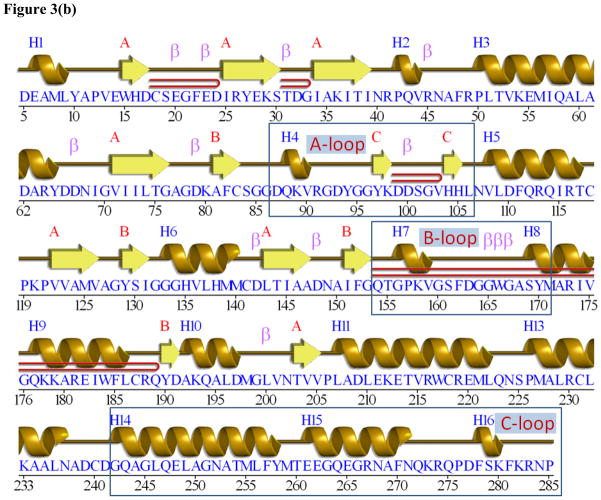

While apo-ecMenB crystallizes in the same space group (P212121) as apo-stMenB (3H02), co-crystallization of ecMenB with OSB-NCoA resulted in a different crystal form with space group P21212. Both structures were refined to a similar resolution of 2 Å with R factors below 0.2 (Table 1). The asymmetric unit contains a hexamer in both cases with the same tertiary and quaternary structure observed for other MenB enzymes. The crotonase fold and hexameric assembly are shown in Figure 3a. The three C-terminal helices (H14–H16, the C-loop) fold across the trimer-trimer interface and contribute to part of the active site in the opposing trimer, a characteristic of all known MenB hexamers (8, 22–23) (Figure 3a, 3b).

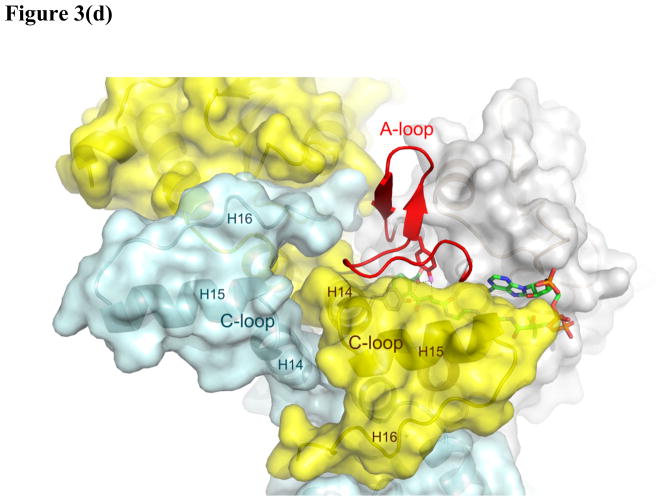

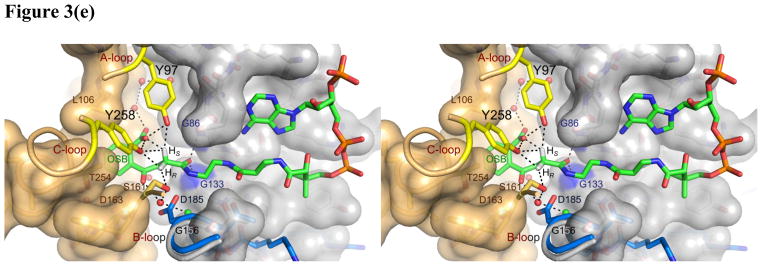

Figure 3. The X-ray structure of the OSB-NCoA:ecMenB complex.

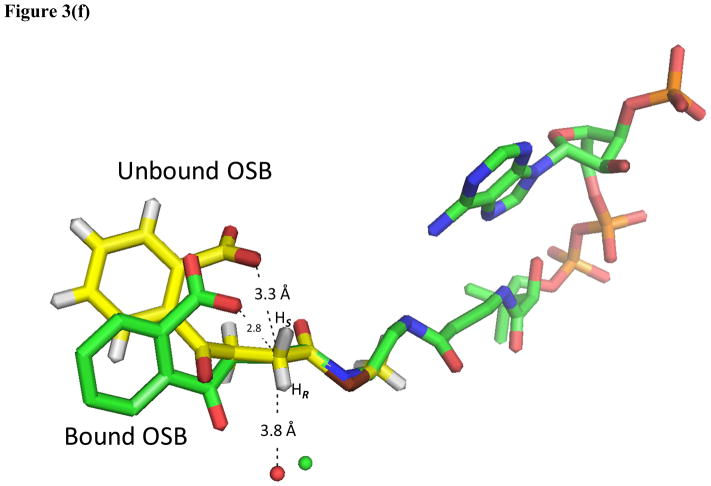

(a) Hexameric assembly of ecMenB in complex with OSB-NCoA viewed along the threefold axis of trimers. The protein is colored by chain and OSB-NCoA is shown in spheres. The C-loop comprising H14–H16 from the back trimer folds across the trimer-trimer interface and covers the active site of the front trimer. (b) Assignment of secondary structures in the ecMenB structure in complex with OSB-NCoA. The diagram was generated by PDBsum (67). The locations of the A, B and C-loops are indicated by boxes. (c) Simulated annealing fo-fc omit maps showing density of OSB-NCoA, the bound anion, and the ordered active site loop region between Q88 and L106 (A-loop). The green map is generated by omitting Q88-L106 from chain C in the model, and the blue map generated by omitting OSB-NCoA and the chloride ion from chain C. The mesh level is contoured at 4.5 σ. (d) The three monomers in grey, yellow and cyan from figure 3a are displayed. The A-loop from the grey monomer covers the active site and makes contacts with the C-terminal helices from two neighboring monomers. OSB-NCoA is shown in sticks. (e) The stereo figure showing the interactions between the OSB group and active site residues. The two hydrogen atoms have been added to the C2 carbon (white). Waters are shown as red spheres and the chloride ion as green sphere. The surface of the oxyanion hole is colored blue. The blue loop from mtMenB (PDB 1Q51) is superimposed and the side chain of D185 is displayed. (f) Overlay of energy-minimized unbound OSB (yellow) and OSB bound to ecMenB (green), showing the reactive conformation in which the distance between the C7 carboxylate oxygen and C2 carbon has decreased. The figures were made using PyMol (68).

Conformation of the A-loop

In the structure of OSB-NCoA bound to ecMenB, the ligand can be observed in all six active sites of the hexamer. Significantly, there is no active site disorder and thus the entire active site of MenB is revealed for the first time (Figure 3c). The A-loop, comprising Q88 to L106 in ecMenB, is locked in the same conformation for all six monomers, forming an additional α coil followed by a loop leading to a β turn and a short β hairpin (the A-loop, Figure 3d). This extensive β-like secondary structure is apparently only trapped by substrate binding since secondary structure prediction in the absence of ligand only infers a disordered loop or α-helical structure (41). The A-loop not only covers the active site, but also packs against the C-terminal helices from two neighboring monomers (yellow and cyan monomers, figure 3d), contributing to the integrity of the MenB hexameric assembly. This includes the C-terminus of a monomer from the opposing trimer which, together with the A-loop, forms part of the active site (C-loop, yellow monomer, figure 3d). In contrast, the A-loop remains disordered for apo-ecMenB as observed in other known MenB structures, and part of the C-loop is also less ordered or displays higher B factors. Placing the hexamer for the enzyme-ligand complex in the lattice of the apo structure generates clashes between the A-loop and an adjacent apo hexamer, indicating incompatibility of this A-loop conformation in the apo crystal form. Apparently the crystal form is altered for the binary complex due to the change in A-loop location upon binding of OSB-NCoA.

Binding mode of the substrate

OSB-NCoA adopts the same conformation in each of the 6 active sites. The CoA portion of the ligand is bound in the U-shaped conformation that is seen in the structures of other crotonase family members (8, 38, 42–48). In addition, the OSB portion is bound in such a way that the C7 carboxylate and C4 carbonyl are clearly out of the plane of the benzene ring, which is also the case when OSB is bound in OSB synthase from Amycolatopsis sp. (1SJB; (49)) and OSB-CoA synthase from Thermobifida fusca (2QVH; (50)). In the MenB reaction carbon-carbon bond formation occurs between the OSB C2 and C7 atoms which are within 3.5 Å of each other in the OSB-NCoA structure. In contrast, the distance between the C2 and C7 atoms is > 5.3 Å in the OSB and OSB-CoA synthases where C-C bond formation does not occur (1FHV, 1SJB and 2QVH (49, 51)). The OSB-NCoA benzoate is surrounded by Y97, F48, L106, V108, L109, Q112, A163 and F162 from the same monomer, Y258 and T254 from the opposing monomer, and an array of eight ordered water molecules. The side chains of L106, V108, L109 and T254 provide favorable hydrophobic interactions with the benzene ring, while the hydroxyl groups from Y97, Y258, and an ordered water molecule provide hydrogen bonding interactions to the carboxylate (Figure 3e). Two additional water molecules extend the hydrogen bonding network to the backbone carbonyl of F48. Other ordered water molecules in the binding pocket mediate a second hydrogen bonding network that involves the backbone carbonyl groups of F162 and G133, and the side chains of T254, D163 and Q112. In addition, S161, an ordered water and a chloride ion are located adjacent to the OSB succinyl moiety. The chloride ion is modeled instead of a water molecule because the electron density is larger than that expected for water. In addition, the negatively charged chloride also interacts favorably with the side chain of Q154 and the backbone NH group of T155. The water molecule is adjacent to the OSB C2 and makes polar interactions with the chloride ion, the oxygen atom of the C4 carbonyl on OSB and the side chain of S161. Finally, the OSB-NCoA amide carbonyl oxygen is hydrogen bonded in the oxyanion hole formed by the backbone NH groups of G86 and G133 (Figure 3e), a feature that is characteristic of the crotonase superfamily. These interactions orient the OSB moiety into the conformation required for carbon-carbon bond formation, and also prevent the OSB carboxylate from attacking the OSB C-4 carbonyl, which is the first step in the uncatalyzed decomposition of OSB-CoA to spirodilactone.

Intramolecular proton transfer

Compared with the structure of OSB determined by energy minimization (52), the bound OSB in the MenB active site adopts a reactive conformation in which the C7 carboxylate is positioned significantly closer toward C2 (Figure 3f). In the unbound structure the oxygen atom on the C7 carboxylate is more than 3.3 Å away from C2 whereas in the bound OSB this distance is between 2.7 and 2.9 Å. Although this is considered an unfavorably close approach of the two atoms by MolProbity, the density map supports the observed interaction which, for the natural substrate, will facilitate the transfer of the pro-2S proton from C2 to C7. This proton transfer is likely facilitated by two nearby Tyr residues, Y97 and Y258 (Figure 3e), which are expected to have pKa values intermediate between the α-proton and the OSB-carboxylate. Instead of direct transfer from C2 to C7, it is possible that Y97 acts as a proton shuttle given its syn position with respect to the carboxylate (53) and its orientation with respect to the C2-Hs bond. In addition, the hydrogen bonding pattern in which Y97 and Y258 donate two in-plane hydrogen bonds to one oxygen atom of the C7 carboxyl group and an ordered water donates one out-of-plane hydrogen bond to the second oxygen suggests that the C7 carboxylate is deprotonated (54). Therefore the C7 carboxylate remains capable of accepting a proton in this binding environment. Thus, intramolecular proton transfer from C2 to C7 not only leads to carbanion formation but also protonates the carboxylate thus making it a better electrophile. In this regard, we note that the involvement of a substrate carboxylate as an acid/base catalyst has also been suggested for 3(S)-methylglutaconyl-CoA hydratase, another member of the crotonase superfamily (55).

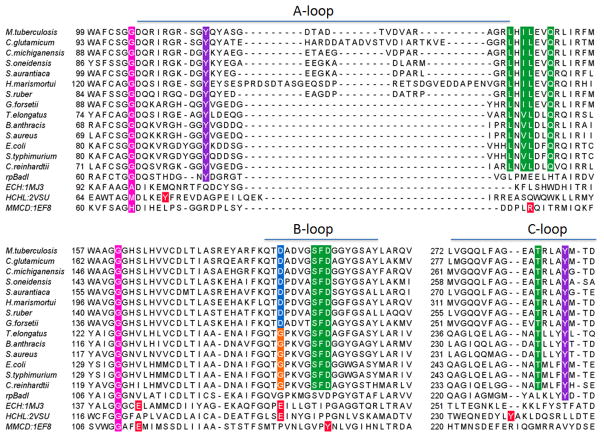

The tetrahedral oxyanion hole

By analogy to the Claisen condensation reactions catalyzed by the β-ketoacyl-ACP synthases in fatty acid biosynthesis, a second oxyanion hole is required to stabilize the tetrahedral oxyanion that results from carbanion attack on the protonated OSB carboxyl group (15–16). The two Tyr residues, Y97 and Y258, are ideally positioned to fulfill this function. Sequence alignment demonstrates that these residues are conserved in the MenB family despite significant variability in the A-loop that carries Y97 (Figure 4). The two Tyr residues are also conserved in BadI, a crotonase superfamily member that catalyzes a retro-Dieckmann condensation presumably via an analogous tetrahedral oxyanion intermediate (56). The alignment with Y97 is not straightforward without the present structure given that additional Tyr residues are present in the A-loop of other MenB enzymes and also because of the active site disorder that characterizes other MenB structures. Once Y97 is aligned properly, the conservation of G96 is also revealed. G96 is adjacent to Leu-106 in space, another conserved residue making direct hydrophobic contacts with the aromatic ring of OSB. Replacement of Y97 with a phenylalanine in ecMenB leads to an inactive enzyme (Table 2) that preserves the overall structure of the enzyme (Figure S5), and previously we demonstrated that the homologue of the second Tyr in mtMenB was essential (Y287) (8). These observations strongly suggest that the two Tyr residues play a critical role in the MenB reaction. A similar strategy is employed by hydroxycinnamoyl-CoA hydratase–lyase (HCHL), another crotonase superfamily member that uses two Tyr residues as a molecular “pincer” to recognize the substrate, initiate deprotonation and exert strain on the substrate. The two Tyr residues in HCHL are located on analogous loops to those found in MenB (Figure 4), one of which is also only observed when the analogous A-loop in HCHL becomes ordered (48).

Figure 4. Sequence alignment of MenB enzymes and other crotonase superfamily members.

MenB sequences were selected from a wide range of organisms including γ-proteobacteria, δ-proteobacteria, firmicutes, actinobacteria, bacteroidetes, cyanobacteria, plants and archaea. The alignment was performed using ClustalW and the figure generated using Jalview (69–70). Alignment of HCHL in the A-loop region was edited according to the alignment of the crystal structures. The enolate oxyanion hole is shown in magenta, the tetrahedral oxyanion hole in purple, OSB-binding residues in green, D185 of mtMenB in blue, G156 of ecMenB in orange, known or possible catalytic residues in other crotonase superfamily members are shown in red (48, 55, 62).

Table 2.

Kinetic Parameters for ecMenB and mtMenB

| Enzyme | kcat · 102 (s−1) | Km · 106 (M) | kcat/Km · 10−4 (s−1 · M−1) |

|---|---|---|---|

| mtMenB | |||

| wild-type | 46.2 ± 1.5 | 22.4 ± 2.1 | 2.1 ± 0.2 |

| D185E | 0.23 ± 0.02 | 4.8 ± 0.3 | 0.048 ± 0.005 |

| D185N | 0.022 ± 0.002 | 3.1± 1.1 | 0.007 ± 0.003 |

| S190A | 0.17 ± 0.02 | 40.2 ± 4.5 | 0.004 ± 0.001 |

| Y287Fa, D185Gb,c, D192Na | No activity | ||

| OCPB-CoA | 0.025 ± 0.003 | 106 ± 31 | 0.00024± 0.00007 |

| OSB-CoA methyl esterb | No activity | ||

|

| |||

| ecMenB | |||

| wild-type | 6.2 ± 0.2 | 25.9 ± 3.3 | 0.24 ± 0.03 |

| Y97F | No activity | ||

| G156Db,c | No activity | ||

Structure of the mtMenB:OSB-NCoA complex

We also attempted to co-crystallize OSB-NCoA with mtMenB which has an A-loop that is 9 residues longer than in ecMenB. The resulting structure is in space group P6122 and contains three MenB monomers in the asymmetric unit (Table 1). The same hexameric assembly observed in existing MenB structures can be generated by a symmetry operation, and the RMSD by aligning the Cα atoms in the three monomers with the equivalent monomers in the hexamer of mtMenB (1Q51) is 0.376 Å. However, in contrast to ecMenB, the A-loop is still disordered in all three monomers. Density for OSB-NCoA can be observed but is weak in chain C possibly due to disorder or low occupancy. In chain B, the density for the CoA portion is improved and there is more residual density for the acyl portion, but the conformation for OSB cannot be determined unambiguously. There is little evidence for the presence of OSB-NCoA in chain A. Instead, the CoA binding site is occupied by the N-terminus of a monomer from a neighboring MenB hexamer in the crystal lattice that prevents the ligand from binding, and hence full occupancy cannot be achieved as in the ecMenB structure. Although the longer A-loop might be responsible for the disorder in the mtMenB structure, it is also plausible that the A-loop only adopts a productive conformation when all six active sites are occupied with the substrate. Such a mechanism might exist to ensure that the MenB hexamer utilizes all its active sites efficiently in catalysis.

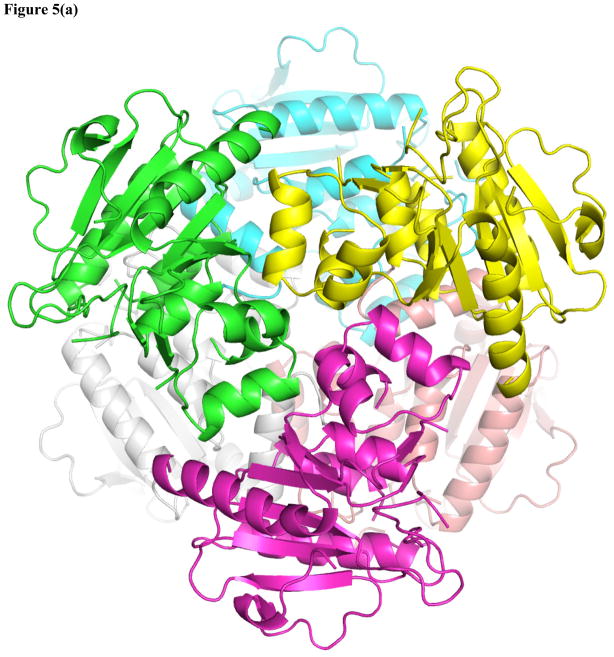

Novel mtMenB hexameric assembly

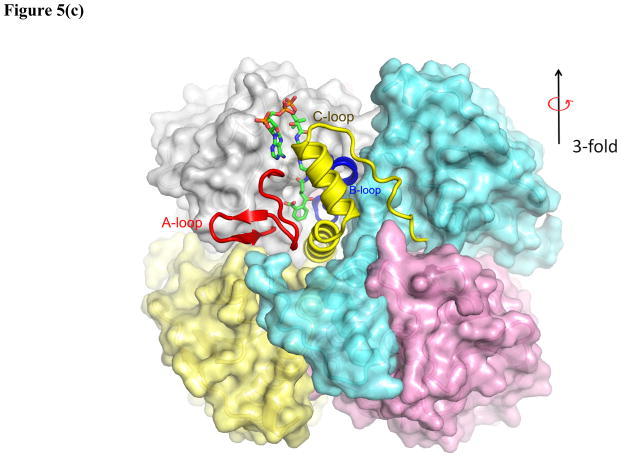

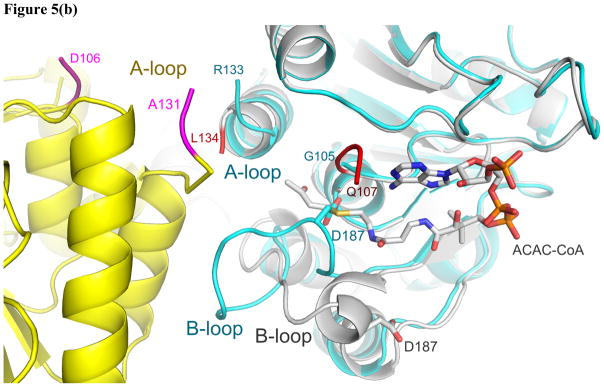

In order to improve the occupancy of OSB-NCoA in mtMenB we attempted to identify a different crystal form in which the N-terminal tail from one monomer did not block the CoA binding site in an adjacent hexamer. We subsequently found a rhombohedral crystal with high diffraction quality, which belongs to space group R3 and contains two monomers in the asymmetric unit. The RMSDs between each monomer and that in 1Q51 are 0.627 Å and 0.364 Å over 211 and 197 Cα atoms, respectively. However, upon symmetry operation the asymmetric unit generates a “staggered” hexamer in striking contrast to the eclipsed configuration in all other known MenB structures (Figure 3a). In this new crystal form, the two trimers in the hexamer are rotated 60° with respect to each other along their three-fold axis (Figure 5a). Consistent with this change in quaternary structure, there is local disruption to the tertiary structure. While the A-loop is disordered, there is also significant disorder in the C-terminal region. In chain A, the C-loop corresponding to residues 273–314 is disordered, and the six preceding residues fold in a different direction resulting in a shift of 16 Å for the Cα of L272 compared to its position in 1Q51, suggesting a large-scale dislocation of the C-loop. In addition, the B loop, which is comprised of residues 183–199 and also forms part of the active site, displays a different conformation in chain A so that D187 travels 9 Å from the protein surface into the oxyanion hole (Figure 6b). The flexibility of these loops is further reflected in chain B where the B-loop, the C-loop and the preceding helix (residues 255–314) give little electron density. As a result, the normal active site seen in other known structures is severely disrupted, and OSB-NCoA is not found in the structure.

Figure 5. The altered mtMenB hexameric assembly and flexible loop regions.

(a) The “staggered” MenB hexameric assembly in contrast to the eclipsed assembly (3(a)) normally observed in MenB enzymes. (b) New contacts at the trimer-trimer interface and the change in conformation of the B-loop that leads to occlusion of the oxyanion hole. The cyan and yellow monomers from figure 5a are displayed. The ends of the disordered A-loop are labeled. Residues 106–110 in the cyan monomer although ordered are not shown for clarity. The structure of mtMenB in complex with acetoacetyl-CoA shown in grey is superimposed with the ends of the disordered A-loop shown in red. The A-loop from yellow monomer comes into close proximity to the A- and B-loop from the cyan monomer. D187 from the B-loop binds in the oxyanion hole, preventing binding of the acyl-CoA ligand. The C-loop does not cover the same binding site as in figure 3d, 3e or 5c. (c) The three loops highlighted using the ecMenB structure correspond to the flexible regions found in MenB and the highly variable regions in the crotonase superfamily. The hexamer is viewed from the side and one set of A-, B- and C-loops is displayed in red, deep blue and yellow. The figures were made using PyMol (68).

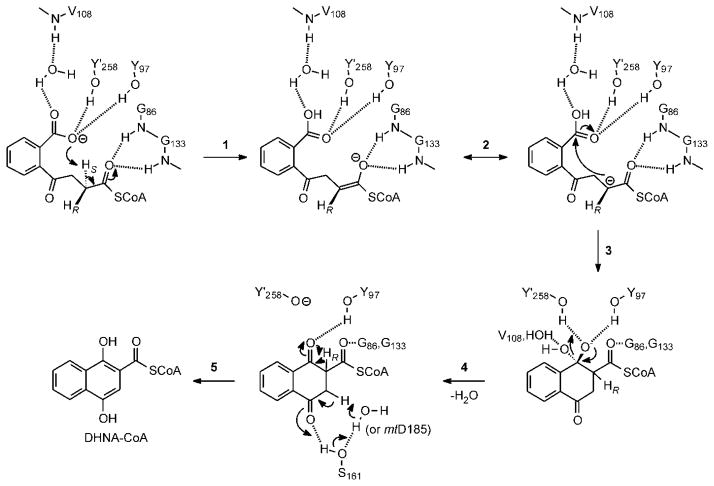

Figure 6. The MenB mechanism.

The OSB carboxylate is positioned to abstract the pro-2S proton, assisted by Y258 and Y97. Proton transfer results in a carbanion/enolate that is stabilized by the classic crotonase oxyanion hole formed by the backbone NH groups of G86 and G133. Subsequent attack of the carbanion on the protonated OSB carboxylic acid leads to a tetrahedral intermediate that is stabilized by hydrogen bonds to Y258 and Y97, which we propose form the second oxyanion hole required for Claisen condensations. This creates a stereo center at the α-carbon and it is not clear at present whether the stereochemistry here is the same as that observed in BadI (66). Elimination of water yields a β-ketothioester which formally is the keto tautomer of the DHNA-CoA product. Subsequent tautomerization to the enol results in a thermodynamically favorable aromatization of the ring. In the Figure we show Y258 acting as the general acid, however adjacent water molecules and other nearby residues are also potential candidates especially if ring formation (step 3) leads to a rearrangement of the active site. A network of hydrogen bonds that interact with the OSB-NCoA keto group is a candidate for assisting in the keto-enol tautomerism and include S161, ordered water molecule(s) and D163. In mycobacterial MenB enzymes the side chain of D185 (mtMenB numbering) is close to S161 and could also be involved in tautomerization.

The disorder of the A-loop is a common observation among crotonase superfamily members (enoyl-CoA hydratase (ECH) (46, 57–58), methylmalonyl CoA decarboxylase (MMCD) (45), Δ3- Δ2-enoyl-CoA isomerase (ECI) (59), and hydroxycinnamoyl-CoA hydratase-lyase (HCHL) (48)), while in MenB the flexibility of the B-loop and C-loop has also been observed (8, 22). These loops together form the interface between the two trimers in the hexamer that buries more than 3450 Å, or 24% of the total surface area, and which is likely the reason for the stability of the mtMenB structure (22). However, the novel hexameric structure reported here demonstrates that the flexibility of these loops can actually lead to a trimer-trimer rotation which establishes new contacts between two A-loops and between the B-loop and A-loop from the two trimers (Figure 5b). While the functional relevance of this rotation is unclear at present, the observation is consistent with the versatility of these loops in the controlling function within the superfamily (60). These loops comprise the active site (Figure 5c), and share little similarity amongst superfamily members. The C-loop is known to be involved in domain swapping that results in variation of the hexameric assembly (8, 45, 61). However, variation of the hexameric assembly within the same enzyme is less well known. Two forms of hexamers have been observed for the yeast peroxisomal Δ3- Δ2-enoyl-CoA isomerase (Eci1p) where it was speculated that the hexamer might dissociate into trimers and associate with a different partner for entry into peroxisomes (59). While lower oligomeric states have been reported for saMenB (23), there is little evidence for the presence of trimeric mtMenB. In solution mtMenB is found exclusively as a hexamer (22), and in the present rhombohedral crystal form the mtMenB monomers clearly form discrete hexameric units. However, only 10% of the total surface area is buried upon trimer-trimer association in contrast to the 24% that is buried in the normal MenB hexamer. Thus the staggered hexamer is likely less stable than the hexameric structure usually adopted by MenB.

Active sites of mtMenB and ecMenB

Although the A-loop and acyl portion of the ligand are not observed in mtMenB, conservation of active site residues identified from the ecMenB structure, including those involved in OSB binding and the two oxyanion holes (Figure 4), indicates that mtMenB is capable of using the same catalytic mechanism as ecMenB. The non-conserved regions, including the 9 extra residues in the A-loop of mtMenB, are expected to be outside the active site while catalysis takes place. One exception, though, is D185 of mtMenB which is located next to the OSB succinyl group. This residue is replaced by G156 in ecMenB, and a water/chloride ion replaces the D185 side chain (Figure 3e). Throughout the MenB family, this residue is either an Asp or a Gly (Figure 4). Although G156 or the water molecule does not appear to play a major role during α-deprotonation or stabilization of the two oxyanion intermediates based on our ecMenB structure, a glutamate or water in a similar position has been proposed to perform acid/base catalysis in a number of crotonase superfamily members including ECH (62), dienoyl-CoA isomerase (63), ECI, (64), HCHL, (48) and DpgC (39). The bicarbonate dependence in the MenB activities of E. coli, S. aureus and B. subtilis and the presence of bicarbonate in the crystal structure of stMenB also has led to a proposal that D185 is used for α-deprotonation in mtMenB and that a bicarbonate cofactor performs the same function when the Asp is replaced by a Gly as in ecMenB, saMenB and bsMenB (21). Our structural analysis of ecMenB, however, does not support this role for bicarbonate, and bicarbonate is also not observed in the structures of saMenB and gkMenB (23, 25).

Nevertheless, both the ordered water molecule in ecMenB and D185 in mtMenB are positioned so that they could aid in the recognition of the OSB C4 carbonyl and assist in the final tautomerization step that leads to DHNA-CoA. D185 in mtMenB clearly plays a critical role in the reaction since kcat for the D185E and D185N mtMenB mutants is reduced 200 and 2000-fold, respectively (Table 2). In addition, neither the D185G mtMenB mutant nor the G156D ecMenB mutant have detectable activity, indicating that the roles of these residues in the two enzymes cannot be simply reversed. Detailed comparison of the two active sites reveals that this result can be attributed to the disruption of the respective hydrogen bonding network optimized for each enzyme when the mutation is introduced (Figures S6 and S7).

Substrate analogues as mechanistic probes

The importance of the OSB carboxylate in α-proton abstraction is substantiated by the observation that the methyl ester analogue of OSB-CoA is inactive (Table 2). If the carbanion can be generated without intramolecular proton transfer to the OSB carboxylate, the OSB-CoA methyl ester is expected to be a good substrate for MenB since methanol and water have similar leaving group abilities. In addition, the Kd for the OSB-CoA methyl ester (11.5 ± 1.2 μM; data not shown) is similar to the Km value for OSB-CoA (22.4 ± 2.1 μM), suggesting that the loss of activity for the methyl ester is not simply due to an inability to bind to MenB. In contrast, OCPB-CoA which lacks the C4 carbonyl is still able to undergo ring closure, albeit with lower efficiency than OSB-CoA, indicating that MenB retains the ability to abstract the substrate α-proton when the OSB carboxylate is not modified (Table 2). These results support our original mechanism for mtMenB in which the OSB carboxylate abstracts the C2 α-proton.

The roles of D163 and S161

ECH contains two active site glutamates, E144 and E164 (62). While E164 is the structural homologue of D185/G156, a second Asp is present in the ecMenB (D163) that is conserved amongst MenB enzymes (D192 in mtMenB) and that is in a similar location in the active site as E144 in ECH. While we have previously shown that the D192N mtMenB mutant was inactive (8), our structural data indicates that D192/D163 points away from the substrate and is involved in a conserved hydrogen bond network so that it cannot directly participate in acid/base catalysis. A similar example is found for MMCD, where E113 is hydrogen-bonded to an arginine and points away from the substrate, preventing it from direct involvement in catalysis (45). Here D192 is hydrogen-bonded to Q140 at the C-terminal end of the A-loop and is apparently important in maintaining the shape of the substrate binding pocket.

Finally, previous studies also demonstrated that S190 in mtMenB was important but not essential for catalysis (Table 2). The structures of mtMenB and ecMenB reveal that the side chain of S190 (S161 in ecMenB) can interact with Y287, D185, the sulfur atom of the thioester moiety and the oxygen atom of the C4 carbonyl group. Its location in the active site suggests that this residue is involved in the tautomerization step.

Mechanism of the MenB-catalyzed reaction

The mechanism of the MenB-catalyzed reaction based on these new observations can be described as follows (Figure 6). Two active site Tyr residues from the A-loop and C-loop play a central role in orientating the OSB C7 carboxylate group so that it can abstract the pro-2S proton in either ecMenB or mtMenB. The resulting enolate oxyanion is stabilized in the oxyanion hole formed by two backbone amides, and the C7 tetrahedral intermediate generated by C-C formation is stabilized by the second oxyanion hole formed by the two Tyr residues. The intramolecular proton transfer leads to protonation of the C7 carboxylate, which increases the electrophilicity of this group while the surrounding hydrogen bond network assists in elimination of water from the tetrahedral oxyanion. The two active site Asp residues in mtMenB or the Asp and water in ecMenB together with the active site serine are involved in correctly positioning the substrate for the reaction and are also likely involved in substrate tautomerization.

Although the X-ray structure of ecMenB in complex with OSB-NCoA strongly suggests that the substrate pro-2S proton is transferred to C7, Igbavboa et al (65) previously reported that MenB catalyzed the exchange of the pro-2R OSB-CoA proton with solvent more rapidly than the pro-2S proton. Although we cannot rationalize this discrepancy, it is possible that other enzymes could be present in the cell extract used for the labeling experiments that might catalyze the exchange of the pro-2R proton with solvent, while the instability of OSB-CoA, which decomposes readily to spirodilactone in solution, could also complicate measurements of stereospecificity. In addition, it is also plausible that the interaction between the OSB carboxylate and the pro-2S proton reduces the propensity of this proton to exchange with solvent. Interestingly, however, the pro-2S stereochemistry agrees with that determined for BadI, which catalyzes a retro-Dieckmann, ring-opening reaction, that is essentially the reverse of the MenB reaction (66). BadI is also a member of the crotonase superfamily and sequence analysis reveals that many active site residues including Y97 and Y258 are conserved between the two enzymes. If MenB and BadI share a common mechanism, then the pro-2S proton in the BadI product could be derived from the Tyr residues or from the carboxylic acid of the substrate which is generated following ring opening.

Conclusion

We have successfully trapped the ecMenB active site in a catalytically relevant conformation using OSB-NCoA, a stable substrate analogue. This structure reveals the positions of all the catalytic residues for the first time, and shows the substrate poised for proton abstraction and carbon-carbon bond formation. Coupled with site-directed mutagenesis and studies with additional substrate analogues, the mechanistic studies reveal how this crotonase superfamily member has adapted to catalyze an intramolecular Claisen condensation reaction. Common or similar strategies are likely employed by other members that catalyze Claisen-like reactions, including BadI, 6-oxocamphor hydrolase and Anabaena β-diketone hydrolase. The serendipitous finding of a novel MenB hexameric assembly also highlights the tight connection between evolution, catalysis and oligomerization within the crotonase scaffold.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grants AI058785 and AI044639 from the National Institutes of Health to PJT and through grants from the Excellence Initiative to the Graduate School of Life Sciences, University of Würzburg (GSC106) for S.M. and the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft FZ82 to C.K. We are grateful to PXRR and NSLS at Brookhaven National Laboratory for beamline access. Data for this study were measured at beamline X29, financial support for which comes principally from the Offices of Biological and Environmental Research and of Basic Energy Sciences of the US Department of Energy, and from the National Center for Research Resources of the National Institutes of Health grant number P41RR012408.

List of Abbreviations

- MenB

1,4-dihydroxy-2-naphthoyl-CoA synthase

- mtMenB

Mycobacterium tuberculosis MenB

- ecMenB

Escherichia coli MenB

- bsMenB

Bacillus subtilis MenB

- stMenB

Salmonella typhimurium MenB

- saMenB

Staphylococcus aureus MenB

- gkMenB

Geobacillus kaustophilus MenB

- ECH

enoyl-CoA hydratase

- MMCD

methylmalonyl CoA decarboxylase

- ECI

Δ3- Δ2-enoyl-CoA isomerase

- HCHL

hydroxycinnamoyl-CoA hydratase-lyase

- DpgC

dihydroxyphenylglyoxylate synthase

- OSB-NCoA

O-succinylbenzoyl-aminoCoA

Footnotes

Supported by NIH grants AI058785 and AI044639 to PJT.

Supporting Information Available

Supporting information includes a detailed description of compound synthesis together with further details of the structure determination and analysis. This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

References

- 1.Bishop DHL, Pandya KP, King HK. Ubiquinone and Vitamin K in Bacteria. Biochem J. 1962;83:606–614. doi: 10.1042/bj0830606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Collins MD, Goodfellow M, Minnikin DE, Alderson G. Menaquinone composition of mycolic acid-containing actinomycetes and some sporoactinomycetes. J Appl Bacteriol. 1985;58:77–86. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2672.1985.tb01431.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dowd P, Ham SW, Naganathan S, Hershline R. The Mechanism of Action of Vitamin K. Annu Rev Nutr. 1995;15:419–440. doi: 10.1146/annurev.nu.15.070195.002223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Olson RE. The function and metabolism of vitamin K. Annu Rev Nutr. 1984;4:281–337. doi: 10.1146/annurev.nu.04.070184.001433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kurosu M, Narayanasamy P, Biswas K, Dhiman R, Crick DC. Discovery of 1,4-dihydroxy-2-naphthoate prenyltransferase inhibitors: new drug leads for multidrug-resistant gram-positive pathogens. J Med Chem. 2007;50:3973–3975. doi: 10.1021/jm070638m. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Li X, Liu N, Zhang H, Knudson SE, Slayden RA, Tonge PJ. Synthesis and SAR studies of 1,4-benzoxazine MenB inhibitors: novel antibacterial agents against Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2010;20:6306–6309. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2010.08.076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lu X, Zhang H, Tonge PJ, Tan DS. Mechanism-based inhibitors of MenE, an acyl-CoA synthetase involved in bacterial menaquinone biosynthesis. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2008 doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2008.07.130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Truglio JJ, Theis K, Feng Y, Gajda R, Machutta C, Tonge PJ, Kisker C. Crystal Structure of Mycobacterium tuberculosis MenB, a Key Enzyme in Vitamin K2 Biosynthesis. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:42352–42360. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M307399200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bentley R, Meganathan R. Biosynthesis of vitamin K (menaquinone) in bacteria. Microbiol Rev. 1982;46:241–280. doi: 10.1128/mr.46.3.241-280.1982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Meganathan R. Biosynthesis of menaquinone (vitamin K2) and ubiquinone (coenzyme Q): a perspective on enzymatic mechanisms. Vitam Horm. 2001;61:173–218. doi: 10.1016/s0083-6729(01)61006-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jiang M, Cao Y, Guo ZF, Chen M, Chen X, Guo Z. Menaquinone biosynthesis in Escherichia coli: identification of 2-succinyl-5-enolpyruvyl-6-hydroxy-3-cyclohexene-1-carboxylate as a novel intermediate and re-evaluation of MenD activity. Biochemistry. 2007;46:10979–10989. doi: 10.1021/bi700810x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jiang M, Chen X, Guo ZF, Cao Y, Chen M, Guo Z. Identification and characterization of (1R,6R)-2-succinyl-6-hydroxy-2,4-cyclohexadiene-1-carboxylate synthase in the menaquinone biosynthesis of Escherichia coli. Biochemistry. 2008;47:3426–3434. doi: 10.1021/bi7023755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bryant RW, Jr, Bentley R. Menaquinone biosynthesis: conversion of o-succinylbenzoic acid to 1,4-dihydroxy-2-naphthoic acid and menaquinones by Escherichia coli extracts. Biochemistry. 1976;15:4792–4796. doi: 10.1021/bi00667a007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Meganathan R, Bentley R. Menaquinone (vitamin K2) biosynthesis: conversion of o-succinylbenzoic acid to 1,4-dihydroxy-2-naphthoic acid by Mycobacterium phlei enzymes. J Bacteriol. 1979;140:92–98. doi: 10.1128/jb.140.1.92-98.1979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Heath RJ, Rock CO. The Claisen condensation in biology. Nat Prod Rep. 2002;19:581–596. doi: 10.1039/b110221b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zhang H, Machutta CA, Tonge PJ. Fatty Acid Biosynthesis and Oxidation. In: Mander L, Lui H-W, editors. Comprehensive Natural Products Chemistry II Chemistry and Biology. 2010. pp. 231–275. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gerlt JA, Babbitt PC. Divergent evolution of enzymatic function: mechanistically diverse superfamilies and functionally distinct suprafamilies. Annu Rev Biochem. 2001;70:209–246. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.70.1.209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Holden HM, Benning MM, Haller T, Gerlt JA. The crotonase superfamily: divergently related enzymes that catalyze different reactions involving acyl coenzyme a thioesters. Acc Chem Res. 2001;34:145–157. doi: 10.1021/ar000053l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hamed RB, Batchelar ET, Clifton IJ, Schofield CJ. Mechanisms and structures of crotonase superfamily enzymes--how nature controls enolate and oxyanion reactivity. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2008;65:2507–2527. doi: 10.1007/s00018-008-8082-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bell AF, Wu J, Feng Y, Tonge PJ. Involvement of glycine 141 in substrate activation by enoyl-CoA hydratase. Biochemistry. 2001;40:1725–1733. doi: 10.1021/bi001733z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jiang M, Chen M, Guo ZF, Guo Z. A bicarbonate cofactor modulates 1,4-dihydroxy-2-naphthoyl-coenzyme a synthase in menaquinone biosynthesis of Escherichia coli. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:30159–30169. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.147702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Johnston JM, Arcus VL, Baker EN. Structure of naphthoate synthase (MenB) from Mycobacterium tuberculosis in both native and product-bound forms. Acta Crystallogr Sect D Biol Crystallogr. 2005;61:1199–1206. doi: 10.1107/S0907444905017531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ulaganathan V, Agacan MF, Buetow L, Tulloch LB, Hunter WN. Structure of Staphylococcus aureus 1,4-dihydroxy-2-naphthoyl-CoA synthase (MenB) in complex with acetoacetyl-CoA. Acta Crystallographica Section F-Structural Biology and Crystallization Communications. 2007;63:908–913. doi: 10.1107/S1744309107047720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Minasov G, Wawrzak Z, Skarina T, Onopriyenko O, Peterson SN, Savchenko A, Anderson WF. Center for Structural Genomics of Infectious Diseases (CSGID) 2009. 2.15 Angstrom Resolution Crystal Structure of Naphthoate Synthase from Salmonella typhimurium. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jeyakanthan J, Kanaujia SP, Vasuki Ranjani C, Sekar K, BaBa S, Ebihara A, Kuramitsu S, Shinkai A, Shiro Y, Yokoyama S. Crystal structure of dihydroxynapthoic acid synthetase (GK2873) from Geobacillus kaustophilus HTA426. RIKEN Structural Genomics/Proteomics Initiative (RSGI) 2006 [Google Scholar]

- 26.Martin DP, Drueckhammer DG. Combined Chemical and Enzymatic Synthesis of Coenzyme A Analogs. J Am Chem Soc. 1992;114:7287–7288. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mishra PK, Drueckhammer DG. Coenzyme A analogues and derivatives: Synthesis and applications as mechanistic probes of coenzyme-A ester utilizing enzymes. Chem Rev. 2000;100:3283–3310. doi: 10.1021/cr990010m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Dai M, Feng Y, Tonge PJ. Synthesis of crotonyl-oxyCoA: a mechanistic probe of the reaction catalyzed by enoyl-CoA hydratase. J Am Chem Soc. 2001;123:506–507. doi: 10.1021/ja003406k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Otwinowski Z, Minor W. Processing of X-ray diffraction data collected in oscillation mode. Meth Enzymol. 1997;276:307–326. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(97)76066-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Vagin A, Teplyakov A. MOLREP: an automated program for molecular replacement. J Appl Crystallogr. 1997;30:1022–1025. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Moriarty NW, Grosse-Kunstleve RW, Adams PD. electronic Ligand Builder and Optimization Workbench (eLBOW): a tool for ligand coordinate and restraint generation. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 2009;65:1074–1080. doi: 10.1107/S0907444909029436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Weininger D. SMILES. 3 DEPICT Graphical depiction of chemical structures. J Chem Inf Comput Sci. 1990;30:237–243. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Adams PD, Afonine PV, Bunkoczi G, Chen VB, Davis IW, Echols N, Headd JJ, Hung LW, Kapral GJ, Grosse-Kunstleve RW, McCoy AJ, Moriarty NW, Oeffner R, Read RJ, Richardson DC, Richardson JS, Terwilliger TC, Zwart PH. PHENIX: a comprehensive Python-based system for macromolecular structure solution. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 2010;66:213–221. doi: 10.1107/S0907444909052925. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Emsley P, Cowtan K. Coot: model-building tools for molecular graphics. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 2004;60:2126–2132. doi: 10.1107/S0907444904019158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Chen VB, Arendall WB, Headd JJ, Keedy DA, Immormino RM, Kapral GJ, Murray LW, Richardson JS, Richardson DC. MolProbity: all-atom structure validation for macromolecular crystallography. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 2010;66:12–21. doi: 10.1107/S0907444909042073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.McCoy AJ, Grosse-Kunstleve RW, Adams PD, Winn MD, Storoni LC, Read RJ. Phaser crystallographic software. J Appl Crystallogr. 2007;40:658–674. doi: 10.1107/S0021889807021206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Beaman TW, Vogel KW, Drueckhammer DG, Blanchard JS, Roderick SL. Acyl group specificity at the active site of tetrahydrodipicolinate N-succinyltransferase. Protein Sci. 2002;11:974–979. doi: 10.1110/ps.4310102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Widboom PF, Fielding EN, Liu Y, Bruner SD. Structural basis for cofactor-independent dioxygenation in vancomycin biosynthesis. Nature. 2007;447:342–345. doi: 10.1038/nature05702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Fielding EN, Widboom PF, Bruner SD. Substrate recognition and catalysis by the cofactor-independent dioxygenase DpgC. Biochemistry. 2007;46:13994–14000. doi: 10.1021/bi701148b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Liu Y, Bruner SD. Rational manipulation of carrier-domain geometry in nonribosomal peptide synthetases. Chem Bio Chem. 2007;8:617–621. doi: 10.1002/cbic.200700010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kelley LA, Sternberg MJE. Protein structure prediction on the Web: a case study using the Phyre server. Nat Protocols. 2009;4:363–371. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2009.2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Benning MM, Taylor KL, Liu RQ, Yang G, Xiang H, Wesenberg G, DunawayMariano D, Holden HM. Structure of 4-chlorobenzoyl coenzyme A dehalogenase determined to 1.8 angstrom resolution: An enzyme catalyst generated via adaptive mutation. Biochemistry. 1996;35:8103–8109. doi: 10.1021/bi960768p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Engel CK, Mathieu M, Zeelen JP, Hiltunen JK, Wierenga RK. Crystal structure of enoyl-coenzyme A (CoA) hydratase at 2.5 angstrom resolution: A spiral fold defines the CoA-binding pocket. EMBO J. 1996;15:5135–5145. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wu WJ, Anderson VE, Raleigh DP, Tonge PJ. Structure of hexadienoyl-CoA bound to enoyl-CoA hydratase determined by transferred nuclear Overhauser effect measurements: mechanistic predictions based on the X-ray structure of 4-(chlorobenzoyl)-CoA dehalogenase. Biochemistry. 1997;36:2211–2220. doi: 10.1021/bi962549+. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Benning MM, Haller T, Gerlt JA, Holden HM. New reactions in the crotonase superfamily: Structure of methylmalonyl CoA decarboxylase from Escherichia coli. Biochemistry. 2000;39:4630–4639. doi: 10.1021/bi9928896. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Bell AF, Feng YG, Hofstein HA, Parikh S, Wu JQ, Rudolph MJ, Kisker C, Whitty A, Tonge PJ. Stereoselectivity of enoyl-CoA hydratase results from preferential activation of one of two bound substrate conformers. Chem Biol. 2002;9:1247–1255. doi: 10.1016/s1074-5521(02)00263-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hall PR, Wang YF, Rivera-Hainaj RE, Zheng XJ, Pustai-Carey M, Carey PR, Yee VC. Transcarboxylase 12S crystal structure: hexamer assembly and substrate binding to a multienzyme core. EMBO J. 2003;22:2334–2347. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdg244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Bennett JP, Bertin L, Moulton B, Fairlamb IJS, Brzozowski AM, Walton NJ, Grogan G. A ternary complex of hydroxycinnamoyl-CoA hydratase-lyase (HCHL) with acetyl-CoA and vanillin gives insights into substrate specificity and mechanism. Biochem J. 2008;414:281–289. doi: 10.1042/BJ20080714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Thoden JB, Ringia EAT, Garrett JB, Gerlt JA, Holden HM, Rayment I. Evolution of enzymatic activity in the enolase superfamily: Structural studies of the promiscuous o-succinylbenzoate synthase from Amycolatopsis. Biochemistry. 2004;43:5716–5727. doi: 10.1021/bi0497897. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Sugadev R, Burley SK, Swaminathan S. New York SGX Research Center for Structural Genomics (NYSGXRC) 2007. Crystal structure of O-succinylbenzoate synthase complexed with O-succinyl benzoate (OSB) [Google Scholar]

- 51.Thompson TB, Garrett JB, Taylor EA, Meganathan R, Gerlt JA, Rayment I. Evolution of enzymatic activity in the enolase superfamily: structure of o-succinylbenzoate synthase from Escherichia coli in complex with Mg2+ and o-succinylbenzoate. Biochemistry. 2000;39:10662–10676. doi: 10.1021/bi000855o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Schuttelkopf AW, van Aalten DMF. PRODRG: a tool for high-throughput crystallography of protein-ligand complexes. Acta Crystallogr Sect D-Biol Crystallogr. 2004;60:1355–1363. doi: 10.1107/S0907444904011679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Gandour RD. On the importance of orientation in general base catalysis by carboxylate. Bioorg Chem. 1981;10:169–176. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Ramanadham M, Jakkal VS, Chidambaram R. Carboxyl group hydrogen bonding in X-ray protein structures analysed using neutron studies on amino acids. FEBS Lett. 1993;323:203–206. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(93)81339-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Wong BJ, Gerlt JA. Evolution of function in the crotonase superfamily: (3S)-methylglutaconyl-CoA hydratase from Pseudomonas putida. Biochemistry. 2004;43:4646–4654. doi: 10.1021/bi0360307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Pelletier DA, Harwood CS. 2-Ketocyclohexanecarboxyl coenzyme A hydrolase, the ring cleavage enzyme required for anaerobic benzoate degradation by Rhodopseudomonas palustris. J Bacteriol. 1998;180:2330–2336. doi: 10.1128/jb.180.9.2330-2336.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Bahnson BJ, Anderson VE, Petsko GA. Structural mechanism of enoyl-CoA hydratase: Three atoms from a single water are added in either an E1cb stepwise or concerted fashion. Biochemistry. 2002;41:2621–2629. doi: 10.1021/bi015844p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Engel CK, Kiema TR, Hiltunen JK, Wierenga RK. The crystal structure of enoyl-CoA hydratase complexed with octanoyl-CoA reveals the structural adaptations required for binding of a long chain fatty acid-CoA molecule. J Mol Biol. 1998;275:847–859. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1997.1491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Mursula AM, Hiltunen JK, Wierenga RK. Structural studies on Delta(3)-Delta(2)-enoyl-CoA isomerase: the variable mode of assembly of the trimeric disks of the crotonase superfamily. FEBS Lett. 2004;557:81–87. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(03)01450-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Xiang H, Luo L, Taylor KL, Dunaway-Mariano D. Interchange of Catalytic Activity within the 2-Enoyl-Coenzyme A Hydratase/Isomerase Superfamily Based on a Common Active Site Template. Biochemistry. 1999;38:7638–7652. doi: 10.1021/bi9901432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Bennett MJ, Schlunegger MP, Eisenberg D. 3D Domain swapping - a mechanism for oligomer assembly. Protein Sci. 1995;4:2455–2468. doi: 10.1002/pro.5560041202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Hofstein HA, Feng Y, Anderson VE, Tonge PJ. Role of Glutamate 144 and Glutamate 164 in the Catalytic Mechanism of Enoyl-CoA Hydratase†. Biochemistry. 1999;38:9508–9516. doi: 10.1021/bi990506y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Modis Y, Filppula SA, Novikov DK, Norledge B, Hiltunen JK, Wierenga RK. The crystal structure of dienoyl-CoA isomerase at 1.5 A resolution reveals the importance of aspartate and glutamate sidechains for catalysis. Structure. 1998;6:957–970. doi: 10.1016/s0969-2126(98)00098-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Muller-Newen G, Stoffel W. Site-directed mutagenesis of putative active-site amino acid residues of 3,2-trans-enoyl-CoA isomerase, conserved within the low-homology isomerase/hydratase enzyme family. Biochemistry. 1993;32:11405–11412. doi: 10.1021/bi00093a018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Igbavboa U, Leistner E. Sequence of proton abstraction and stereochemistry of the reaction catalyzed by naphthoate synthase, an enzyme involved in menaquinone (vitamin K2) biosynthesis. Eur J Biochem. 1990;192:441–449. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1990.tb19246.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Eberhard ED, Gerlt JA. Evolution of function in the crotonase superfamily: the stereochemical course of the reaction catalyzed by 2-ketocyclohexanecarboxyl-CoA hydrolase. J Am Chem Soc. 2004;126:7188–7189. doi: 10.1021/ja0482381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Laskowski RA, Hutchinson EG, Michie AD, Wallace AC, Jones ML, Thornton JM. PDBsum: a Web-based database of summaries and analyses of all PDB structures. Trends Biochem Sci. 1997;22:488–490. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0004(97)01140-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Delano WL. The PyMOL Molecular Graphics System. 2002 http://www.pymol.org.

- 69.Clamp M, Cuff J, Searle SM, Barton GJ. The Jalview Java alignment editor. Bioinformatics. 2004;20:426–427. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btg430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Waterhouse AM, Procter JB, Martin DMA, Clamp M, Barton GJ. Jalview Version 2-a multiple sequence alignment editor and analysis workbench. Bioinformatics. 2009;25:1189–1191. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.