Abstract

Negative symptoms are present in the psychosis prodrome. However, the extent to which these symptoms are present prior to the onset of the first episode of psychosis remains under-researched. The goal of this study is to examine negative symptoms in a sample of individuals at clinical high risk (CHR) for psychosis and to determine if they are predictive of conversion to psychosis. Participants (n=138) were all participants in the North American Prodrome Longitudinal Study (NAPLS 1) project. Negative symptoms were assessed longitudinally using the Scale of Prodromal Symptoms. The mean total negative symptom score at baseline was 11.0, with 82.0% of the sample scoring at moderate severity or above on at least one negative symptom. Over the course of 12 months, the symptoms remained in the above moderate severity range for 54.0% of participants. Associations between individual symptoms were moderate (r= 0.31 to r= 0.57, P<0.001) and a factor analysis confirmed that all negative symptoms loaded heavily on one factor. Negative symptoms were more severe and persistent over-time in those who converted to psychosis, predicting the likelihood of conversion (χ2 = 17.63, df= 6, P< 0.01, R2 = 0.21). Thus, early and persistent negative symptoms may represent a vulnerability for risk of developing psychosis.

Keywords: psychosis prodrome, negative symptoms, conversion to psychosis, longitudinal study, NAPLS1 project

1. Introduction

Recent advances in research in early detection of psychosis have led to the development of reliable criteria to identify individuals who may be at risk of developing psychosis and thus potentially experiencing a prodrome for psychosis (Yung and McGorry, 1996b; McGlashan et al., 2010). These prospective studies rely primarily on the presence of attenuated positive symptoms and decreased functioning (Yung and McGorry, 1996b; McGlashan et al., 2010). However, significant proportions of these individuals have non-specific symptoms (e.g. depression and anxiety) as well as negative symptoms, such as social isolation/withdrawal, and reduced motivation (Lencz et al., 2004). This finding pertaining to the construct of amotivation or avolition is in agreement with findings from patients with schizophrenia (Faerden et al., 2009). Interestingly it is these behavioural and functional changes that are often the first reasons for seeking help (Yung and McGorry, 1996a; Lencz et al., 2004). Relative to attenuated positive symptoms the prevalence of negative symptoms is high (Yung et al., 2003; Lencz et al., 2004; Velthorst et al., 2009) of which social isolation and deterioration in role (school) functioning are most frequently reported (Lencz et al., 2004). Furthermore, negative symptoms, especially increased social isolation and withdrawal, have been reported to be predictive of transition to psychosis (Kwapil, 1998; Mason et al., 2004; Yung et al., 2005; Velthorst et al., 2009). In the Edinburgh longitudinal study of individuals at genetic high risk of psychosis (Johnstone et al., 2005), social withdrawal and isolation, as measured on the Structural Interview for Schizotypy, emerged as the strongest discriminator between those who converted and those who did not.

Typically, negative symptoms are examined as one construct, although there are reports of negative symptoms clustering into two domains of diminished expression (i.e. affective flattening and poverty of speech) and amotivation (i.e. avolition/apathy and anhedonia/asociality) (Mueser et al., 1994; Sayers et al., 1996). More recently there has been a focus on differences among individual negative symptoms with suggestions that “avolition” is a core negative symptom with a direct impact on both functional outcome and cognitive function (Foussias and Remington, 2010).

Previous studies of the psychosis prodrome that explored the predictive value of negative symptoms to psychosis conversion have done so using different instruments to assess prodromal symptoms. Whereas some studies used scales designed to rate the severity of sub-psychotic level symptoms (Yung et al., 2005; Velthorst et al., 2009) others used conventional rating scales for psychotic-level symptoms (Mason et al., 2004) or a scale designed to assess a single symptom (Kwapil, 1998). Furthermore, none of the studies included longitudinal examination of negative symptoms. Thus, the goal of the present investigation was to examine in more detail negative symptoms in a sample of individuals described as being at clinical high risk (CHR) of developing psychosis. The specific aims were: 1) to determine the prevalence of individual negative symptoms; 2) to determine the stability of negative symptoms, 3) to explore the factor structure of positive and negative symptoms of the SOPS, and 4) to explore longitudinally the role of negative symptoms in conversion to psychosis.

2. Methods

2.1. Participants

The North American Prodrome Longitudinal Study (NAPLS-1) project is a consortium of eight research sites that investigated the earliest phase of psychotic illness, with the goal of improving the accuracy of prospective prediction of psychosis (Addington et al., 2007; Cannon et al., 2008). All sites recruited CHR individuals and followed them up for a period of up to 2. years during the period 2000–2006. Although initially developed as independent studies, the investigations at eight sites employed similar ascertainment and diagnostic methods (Structured Interview for Prodromal Syndromes(SIPS) (McGlashan et al., 2010) making it possible to form a standardised protocol for mapping data into a new scheme representing the common components across sites (Addington et al., 2007). The study protocols and informed consents were reviewed and approved by the ethical review boards of all eight study sites. Methods and details of the NAPLS-1 are reviewed in detail elsewhere (Addington et al., 2007; Cannon et al., 2008).

Three hundred and seventy-two participants met one of the three established criteria for a psychosis risk syndrome, namely: attenuated psychotic symptom state (APSS), brief intermittent psychotic symptom state (BIPS) and genetic risk with deterioration (GRD). Criteria for a prodromal syndrome and criteria for conversion to psychosis were determined using the Structured Interview for Prodromal Syndromes (SIPS) (McGlashan et al., 2010). Conversion meant that at least one of the five attenuated positive symptoms reached a psychotic level of intensity (rated 6) for a frequency of ≥ 1 hour/day for 4 days/week during the past month or that symptoms seriously impacting functioning (e.g. severely disorganised or dangerous to self or others) (McGlashan et al., 2010). All NAPLS sites demonstrated reliability in rating criteria (κ’s ranged from 0.80 to 1.00 across sites) (Addington et al., 2007).

The Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV (SCID-I) (First et al., 1995) was used to determine the presence of any axis I disorders. Participants were excluded if they met criteria for any current or lifetime axis I psychotic disorder, IQ< than 70 or past or current history of a clinically significant central nervous system disorder which may confound or contribute to prodromal symptoms.

For this project we only included participants who had completed the negative symptom ratings at both 6- and 12-month follow-up. Thus, participants were 50 females and 88 males. At ascertainment, the mean age was 18.6 years (SD= 4.88). On average participants had 10.7 years of education (SD=3.25) with 91 participants (66.0%) attending high school and 18 (13.0%) attending college. Twenty-six participants (19.0%) were employed full-time. Sixty-six participants (48.0 %) met DSM-IV criteria for a mood disorder, 12 (9.0%) met criteria for an anxiety disorder and 5 (3.5 %) met criteria for substance abuse disorders. All participants met the criteria for attenuated psychotic symptom syndrome (APSS). This sample of 138 did not differ on demographic or symptom variables from the 234 participants excluded from the analysis who did not have follow-up data on negative symptoms.

2.2. Assessments

The Structured Interview for Prodromal Syndromes (SIPS) (McGlashan et al., 2010) criteria were used at the study entry. Attenuated positive symptoms and negative symptoms were assessed using the Scale of Prodromal Symptoms (SOPS)1.

2.3. Statistical Analyses

Demographic variables and negative symptom ratings were summarised using descriptive statistics. Difference in prevalence of negative symptoms over time was assessed using the two-proportions Z-test. Stability of negative symptoms over time was assessed using repeated measures ANOVA with the Bonferroni correction for multiple comparisons. Principal component analysis (PCA) was used to explore the factor structure of positive and negative symptoms of the SOPS. Participants who received a diagnosis of a psychotic disorder during the course of the study were classified as converters. Group differences between converters and non-converters, as well as gender differences, were assessed using the Mann-Whitney U test (MWU). Direct logistic regression was performed to evaluate the predictive value of negative symptoms on conversion. This method was chosen because it allows evaluation of the contribution made by each negative symptom over and above contribution of other predictors (Tabachnik and Fidel, 2001). Furthermore, it was an appropriate model given that we had no specific hypotheses about the order or importance of individual negative symptoms. All assumptions for the different analysis were met prior to interpretation of the results.

3. Results

3.1. Baseline negative symptoms

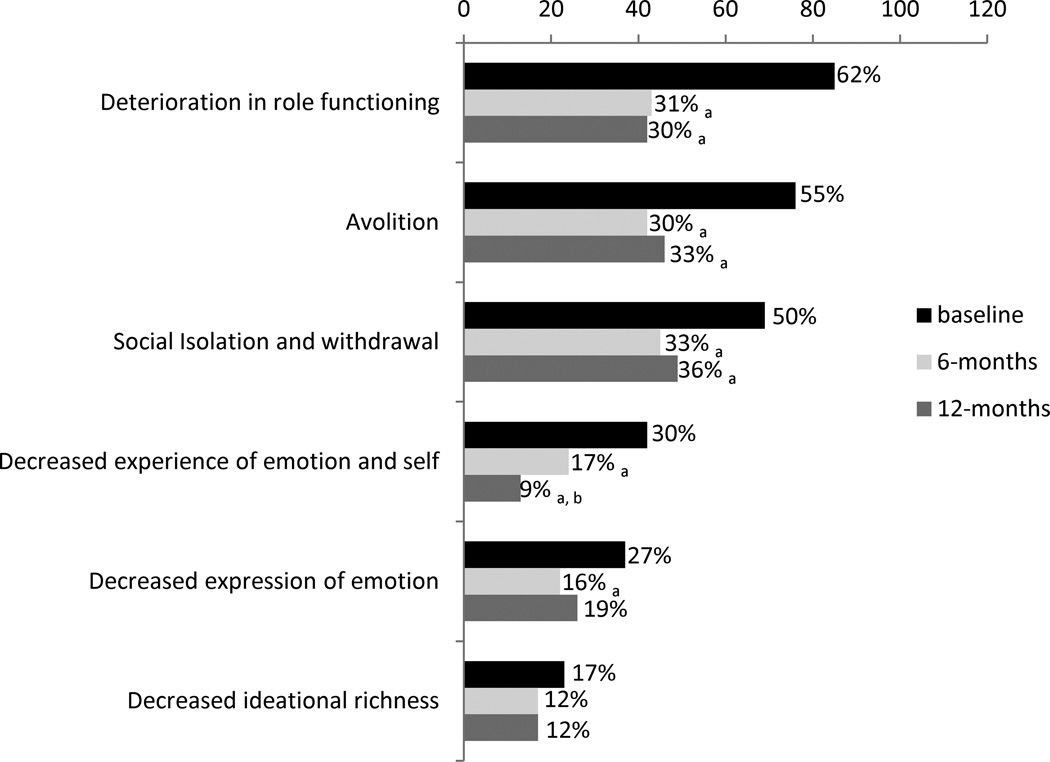

A majority of participants (82.0%) at the start of the study endorsed at least one negative symptom rated ≥ 3 on the SOPS (i.e. moderate to above moderate severity). Sixty-one (44.0%) participants reported at least one symptom in the moderate to above moderate range (i.e. SOPS ratings of 3 and 4), and 52 (38.0%) participants reported symptoms in the severe range (i.e. SOPS ratings of 5 and 6). Males had more severe negative symptoms (M = 13.60, SD= 7.25) compared to females (M = 8.86, SD= 6.58, t = −3.81, P< 0.001). Reported prevalence for specific negative symptoms of ≥ 3 severity rating at baseline 6- and 12-month follow-up are displayed in Figure 1. At baseline, “deterioration in role functioning”, “avolition” and “social withdrawal” were the most frequently reported negative symptoms whereas “decreased ideational richness” was the least reported symptom.

Figure 1.

Prevalence of reported negative symptoms rated ≥ 3 at baseline, 6 and 12 months

Note: a, significantly different from baseline at P<0.05 level

b, significantly different from 6-months at P<0.05 level

3.2. Change over time

Repeated measures ANOVAs revealed that there was a significant decrease in severity of negative symptoms over time (F (2, 274) = 43.72, P< 0.001). Table 1 displays the results of within-subjects contrasts for changes in the severity of each negative symptom over time. At 12 months, seventy-four participants (54%) continued to score in the moderate to above moderate severity (i.e. ≥ 3) on at least one negative symptom. Significant decrease in prevalence of symptoms in the moderate to above moderate severity continued through the follow-up period for some, but not all symptoms (Figure 1). For 39 participants, at least one negative symptom was in the moderate and severe range both at baseline and the follow-up. Among this group 11 participants were converters.

Table 1.

Negative symptom severity over time

| Baseline M (SD) |

6 months M (SD) |

12 months M(SD) |

P | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| N1- social isolation/withdrawal | 2.54 (1.95) | 1.72 (1.81)a | 1.90 (1.91)a | <0.001 |

| N2- avolition | 2.51 (1.64) | 1.56 (1.69)a | 1.74 (1.71)a | <0.001 |

| N3- decreased expression of emotion | 1.37 (1.64) | 0.98 (1.38)a | 1.02 (1.40) | <0.01 |

| N4- decreased experience of emotion | 1.41 (4.65) | 0.88 (1.40)a | 0.72 (1.20)a | <0.001 |

| N5- decreased ideational richness | 1.01 (1.37) | 0.70 (1.20)a | 0.69 (1.23)a | <0.01 |

| N6- deterioration in role functioning | 3.04 (1.92) | 1.79 (1.86)a | 1.74 (1.96)a | <0.001 |

| N_total | 11.88 (7.36) | 7.62 (7.20)a | 7.81 (7.14)a | <0.001 |

Note:

significantly different from baseline at P< 0.01 after the Bonferroni correction for multiple comparisons

3.3. Factor loading and correlations between negative symptoms

All positive and negative symptoms of the SOPS were entered into a principal component analysis. According to the correlation matrix, associations between individual negative symptoms were moderate, with correlation coefficients ranging between r = 0.31 and r = 0.57 (P<0.001). Analyses of the factor extraction matrix and the scree plot indicated four components with eigenvalues exceeding one. All negative symptom items loaded heavily on the first component whereas positive symptoms were spread over the second, third and fourth components. Furthermore, components three and four were similar in terms of eigenvalues suggesting that retention of three components is justifiable. Following varimax rotation of three components, all negative symptoms within the SOPS loaded on Factor 1. See Table 2.

Table 2.

Rotated component matrix of SOPS negative and positive items (n=138)

| Symptoms | Factor |

||

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | |

| N2- Avolition | .784 | ||

| N6- Deterioration in role functioning | .763 | ||

| N3- Decreased expression of emotion | .726 | ||

| N1- Social isolation and withdrawal | .688 | .379 | |

| N4- Decreased experience of emotion and self | .657 | ||

| N5- Decreased ideational richness | .618 | .357 | |

| P1- Unusual thought content/delusional ideas | .728 | ||

| P2- Suspiciousness/persecutory ideas | .575 | ||

| P3- Grandiosity | .708 | ||

| P4- Perceptual abnormalities/hallucinations | .563 | −.636 | |

| P5- Conceptual disorganization | .516 | ||

Extraction Method: Principal Component Analysis with varimax rotation.

Primary loadings are displayed in bold typeface. Loadings < 0.35 are omitted from the table for clarity

3.4. Conversion to psychosis

By 12 months, 20 (15.0%) participants, 5 females and 15 males, converted to psychosis. Compared to participants who did not convert, converters had significantly higher severity of negative symptoms at baseline (see Table 3). However, the two groups did not differ on positive symptoms or any demographic variables, such as age, gender, ethnicity, years of education or employment status.

Table 3.

Baseline negative symptoms and transition to psychosis

| Non-converters n= 118 M (SD) |

Converters n= 21 M (SD) |

Mann- Whitney U test |

P | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| N1- Avolition | 2.36 (1.91) | 3.60 (1.90) | 760.0 | <0.05 |

| N2- Social isolation and withdrawal | 2.36 (1.62) | 3.35 (1.56) | 810.5 | <0.05 |

| N3- Decreased expression of emotion | 1.24 (1.57) | 2.15 (1.87) | 846.0 | <0.05 |

| N4- Decreased experience of emotion and self | 1.29 (1.62) | 2.15 (1.69) | 851.5 | <0.05 |

| N5- Decreased ideational richness | 0.86 (1.24) | 1.95 (1.76) | 762.5 | <0.05 |

| N6- Deterioration in role functioning | 2.86 (1.91) | 4.10 (1.68) | 749.0 | <0.001 |

| Total negative symptoms | 10.97 (6.89) | 17.30 (7.87) | 656.0 | <0.01 |

Since both groups differed significantly on all six negative symptoms at baseline, all six symptoms were entered into a direct logistic regression as possible predictors of conversion. A test of the model with all six negative symptoms as predictors against an intercept only model was statistically significant (χ2 = 14.64, df = 6, P< 0.05, Cox and Snell R2 = 0.10) indicating that negative symptoms discriminated between participants who converted to psychosis and those who did not. Assumptions of co-linearity (tolerance range: 0.51 to 0.79; VIF range: 1.26 to 1.95) and goodness of fit (Hosmer-Lemeshow χ2 = 5.84, df = 8, P = 0.66) were satisfied. No individual negative symptom emerged as a significant predictor of conversion. The model explained 10% of variance in conversion rates.

Since negative symptoms persisted in a sub-group of participants over time we examined whether those with persistent negative symptoms differed in rates of conversion from those who had a decrease in negative symptoms. Using chi-square we compared the number of converters in two groups, those with and those without persistent negative symptoms at 12 months. The analysis revealed that in the group of participants with persistent negative symptoms (n = 74) 17 converted to psychosis compared to only 3 participants in the group without persistent negative symptoms (n = 64). This difference in the number of converters in the two groups was significant (χ2 = 9.26, p< 0.01).

Thus, to determine if persistent negative symptoms were perhaps more likely to predict conversion in a sub group with persistent negative symptoms (n = 74), all 6 negative symptoms at 12 months were entered together into a logistic regression model against an intercept only model. The model was statistically significant (χ2 = 17.63, df = 6, P< 0.01, Cox and Snell R2 = 0.21) indicating that persistence of negative symptoms at 12 months explained 21% of variance in the conversion rates in those with persistent negative symptoms. However, no individual negative symptom emerged as a significant predictor of conversion. Once again, assumptions of co linearity (tolerance range: 0.53 to 0.67; VIF range: 1.50 to 1.90) and goodness of fit (Hosmer-Lemeshow χ2 = 12.28, df = 8, P = 0.12) were satisfied.

3.5. Medication

The impact of antipsychotics on negative symptoms at baseline and 12 months was examined using the non-parametric Mann-Whitney U test. At baseline, n= 8 were receiving antipsychotics compared to n= 60 who were not. When the two groups were compared, the analysis revealed no significant group differences at baseline, but significant group differences at 12 months. That is, those receiving antipsychotics at 12 months demonstrated higher severity of negative symptoms (n= 20; M = 10.30, SD = 6.77) compared to participants who were not on antipsychotics (n= 51; M = 6.29, SD = 7.14, MWU = 299.50, P< 0.01).

4. Discussion

In the current investigation, negative symptoms were prevalent at study admission in a majority of CHR individuals, with males having more severe symptoms than females. A majority of participants reported at least one negative symptom of moderate or high severity. The most frequently endorsed symptoms of at least moderate severity were “deterioration in role functioning”, “avolition” and “social withdrawal”, whereas the least frequently endorsed symptoms were “diminution in affective experiences” and “decreased ideational richness”. On average all of the significant improvement in negative symptoms occurred in the first 6 months. However, a subgroup of participants continued to endorse individual negative symptoms in the moderate to high severity range at follow-up. Thus, there appears to be a subsample of CHR participants for whom significant negative symptoms persist over the time period of this study. This observation has been reported in other high risk samples as well as those at the first episode and with a more established schizophrenia illness (Addington et al., 2003; Yung et al., 2003; Lencz et al., 2004; Yung et al., 2004; Blanchard et al., 2005, Velthorst et al., 2009). With respect to the observed improvements, it is possible that they reflect, at least to an extent, heterogeneity of the CHR sample which was evident in an earlier publication of this sample (Addington et al., 2011). Here it was suggested that CHR individuals represent a collection of individuals who tend to fall in the following groups: 1) those truly at risk for psychosis that are showing the first signs of disorder; 2) those who remit in terms of the symptoms used to index CHR status, and 3) those who continue to have attenuated symptoms of psychosis. Although there was evidence of apathy/avolition in these CHR individuals it did not stand out as a possible core negative symptom as has been described in samples with a more established psychotic illness (Faerden et al., 2009). In fact, our data supports the emergence of a distinct negative symptom factor, which fits with a previous report from a smaller sample of CHR participants (Hawkins et al., 2004).

Those who went on to develop a full blown psychotic illness had significantly more severe baseline negative symptoms, in particular “deterioration in role functioning” and “social withdrawal”, which persisted over a 12 month period in a subgroup of participants. Although, baseline negative symptoms predicted conversion, persistence of symptoms over 12 months was a better predictor of conversion than severity of baseline symptoms alone. Despite the fact that stability of negative symptoms explained one fifth of the variance in conversion rates, it is possible that other factors, such as psychosocial functioning, make a larger contribution to conversion (Cornblatt et al., in press). It was noted that those on antipsychotics had higher levels of negative symptoms. It cannot be determined if this is due to secondary effects of antipsychotic medication or simply to the possibility that individuals with more severe symptoms overall are the ones for whom the antipsychotics are prescribed.

The main strengths of this study are its longitudinal, prospective design, large sample size of CHR individuals and examination of the SOPS factor structure. There are some limitations. First, the follow-up period is short. A second limitation is that negative symptoms were rated on the negative symptom subscale of the SOPS. To the best of our knowledge we are not aware of any research that has compared the ratings of negative symptoms on the SOPS to rating negative symptoms on scales used for those with established psychotic illness such as the PANSS and the SANS. It is unknown if negative symptoms rated on the SOPS differ from negative symptoms rated on one of these other scales. Future work needs to examine the relationship of SOPS negative symptom ratings to ratings on more established scales of negative symptoms. A further concern is that N6 clearly reflects poor functioning. This would be an important area for future research particularly in light of the recent work by the NIMH task force on negative symptoms (Blanchard and Cohen, 2006; Kirkpatrick et al., 2006).

In conclusion, the current study finds that moderate and severe attenuated negative symptoms are frequently endorsed by individuals at CHR of psychosis, and all contribute to a broad single negative symptom factor. Although the severity of negative symptoms is higher at study entry and dissipates over time, there appears to be a subsample of CHR individuals for whom “deterioration in role functioning”, “avolition” and “social withdrawal” persist over a longer course. Negative symptoms are more severe and persistent in individuals who convert to psychosis, and are moderately predictive of later conversion. In conclusion, it may be that attenuated negative symptoms represent a core vulnerability placing individuals at clinical high risk of developing psychosis, and could be important targets of early intervention.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Funding

This work was supported by the National Institute of Mental Health {grant numbers U01 MH066160 to SWW, U01 MH066134 to JA, R01 MH60720 and K24 MH76191 to KSC, R01 MH065079 to TDC, R01 MH061523 to BAC, R01 MH066069 and K23 MH01905to DOP, R18 MH 43518 (MTT and LJS), R01 MH065562 and P50 MH080272 to LJS, R21MH075027 to MTT, RO1MH062066 to EFW, K05MH01654 to THM]; Donaghue Foundation {to SWW]; and Eli Lilly & Co {to THM, JA, and DOP].

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Descriptions of negative symptoms are available in the Supplementary Material

References

- Addington J, Cadenhead KS, Cannon TD, Cornblatt B, McGlashan TH, Perkins DO, Seidman LJ, Tsuang M, Walker EF, Woods SW, Heinssen R. North American Prodrome Longitudinal Study: a collaborative multisite approach to prodromal schizophrenia research. Schizophrenia Bulletin. 2007;33:665–672. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbl075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Addington J, Cornblatt BA, Cadenhead KS, Cannon TD, McGlashan TH, Perkins DO, Seidman LJ, Tsuang MT, Walker EF, Woods SW, Heinssen R. At clinical high risk for psychosis: outcome for nonconverters. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2011;168(8):800–805. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2011.10081191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Addington J, Young J, Addington D. Social outcome in early psychosis. Psychological Medicine. 2003;33(6):1119–1124. doi: 10.1017/s0033291703007815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blanchard JJ, Horan WP, Collins LM. Examining the latent structure of negative symptoms: is there a distinct subtype of negative symptom schizophrenia? Schizophrenia Research. 2005;77:151–165. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2005.03.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blanchard JJ, Cohen AS. The structure of negative symptoms within schizophrenia: implications for assessment. Schizophrenia Bulletin. 2006;32:238–245. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbj013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cannon TD, Cadenhead K, Cornblatt B, Woods SW, Addington J, Walker E, et al. Prediction of psychosis in youth at high clinical risk: a multisite longitudinal study in North America. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2008;65:28–37. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2007.3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cornblatt BA, Carrion RE, Addington J, Seidman L, Walker EF, Cannon TD, et al. Risk Factors for Psychosis: Impaired Social and Role Functioning. Schizophrenia Bulletin. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbr136. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faerden A, Friis S, Agartz I, Barret EA, Nesvag R, Finset A, Melle I. Apathy and functioning in first-episode psychosis. Psychiatric Services. 2009;60:1495–1503. doi: 10.1176/ps.2009.60.11.1495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- First M, Spitzer R, Gibbon M, Williams B, Williams J. Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis I Disorders, Patient Edition. New York: New York State Psychiatric Institute; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Foussias G, Remington G. Negative symptoms in schizophrenia: avolition and Occam's razor. Schizophrenia Bulletin. 2010;36:359–369. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbn094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hawkins KA, McGlashan TH, Quinlan D, Miller TJ, Perkins DO, Zipursky RB, Addington J, Woods SW. Factorial Structure of the Scale of Prodromal Symptoms. Schizophrenia Research. 2004;68:339–347. doi: 10.1016/S0920-9964(03)00053-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnstone EC, Ebmeier KP, Miller P, Owens DG, Lawrie SM. Predicting schizophrenia: findings from the Edinburgh High-Risk Study. British Journal of Psychiatry. 2005;186:18–25. doi: 10.1192/bjp.186.1.18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirkpatrick B, Fenton WS, Carpenter WT, Jr, Marder SR. The NIMH-MATRICS consensus statement on negative symptoms. Schizophrenia Bulletin. 2006;32:214–219. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbj053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kwapil TR. Social anhedonia as a predictor of the development of schizophrenia spectrum disorders. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1998;107:558–565. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.107.4.558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lencz T, Smith CW, Auther A, Correll CU, Cornblatt B. Nonspecific and attenuated negative symptoms in patients at clinical high-risk for schizophrenia. Schizophrenia Research. 2004;68:37–48. doi: 10.1016/S0920-9964(03)00214-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mason O, Startup M, Halpin S, Schall U, Conrad A, Carr V. Risk factors for transition to first episode psychosis among individuals with 'at-risk mental states'. Schizophrenia Research. 2004;71:227–237. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2004.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGlashan T, Walsh B, Woods S. The Psychosis-Risk Syndrome: Handbook for Diagnosis and Follow-up. New York: Oxford University Press; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Mueser KT, Sayers SL, Schooler NR, Mance RM, Haas GL. A multisite investigation of the reliability of the Scale for the Assessment of Negative Symptoms. American Journal of Psychiatry. 1994;151:1453–1462. doi: 10.1176/ajp.151.10.1453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sayers SL, Curran PJ, Mueser KT. Factor structure and construct validity of the scales for the assessment of negative symptoms. Psychological Assessment. 1996;8:269–280. [Google Scholar]

- Tabachnik BG, Fidel LS. Using Multivariate Statistics. 4th ed. Needham Heights, MA: 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Velthorst E, Nieman DH, Becker HE, van de Fliert R, Dingemans PM, Klassenn R, de Haan L, van Amelsvoort T, Linszen DH. Baseline differences in clinical symptomatology between ultra high risk subjects with and without a transition to psychosis. Schizophrenia Research. 2009;109:60–65. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2009.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yung AR, McGorry PD. The initial prodrome in psychosis: descriptive and qualitative aspects. Australia and New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry. 1996a;30:587–599. doi: 10.3109/00048679609062654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yung AR, McGorry PD. The prodromal phase of first-episode psychosis: past and current conceptualizations. Schizophrenia Bulletin. 1996b;22:353–370. doi: 10.1093/schbul/22.2.353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yung AR, Phillips LJ, Yuen HP, Francey SM, McFarlane CA, Hallgren M, McGorry PD. Psychosis prediction: 12-month follow up of a high-risk ("prodromal") group. Schizophrenia Research. 2003;60:21–32. doi: 10.1016/s0920-9964(02)00167-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yung AR, Phillips LJ, Yuen HP, McGorry PD. Risk factors for psychosis in an ultra high-risk group: psychopathology and clinical features. Schizophrenia Research. 2004;67:131–142. doi: 10.1016/S0920-9964(03)00192-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yung AR, Yuen HP, McGorry PD, Phillips LJ, Kelly D, Dell’Olio M, Francey SM, Cosgrave EM, Killackey E, Stanford C, Godfrey K, Buckby J. Mapping the onset of psychosis: the Comprehensive Assessment of At-Risk Mental States. Australia and New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry. 2005;39:964–971. doi: 10.1080/j.1440-1614.2005.01714.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.