Abstract

The present paper is concerned with radiochemical methodology to furnish the trifluoromethyl motif labelled with 18F. Literature spanning the last four decades is comprehensively reviewed and radiochemical yields and specific activities are discussed.

1. Introduction

Substantial interest has been given lately to the trifluoromethyl group in the context of radiotracer development for positron emission tomography (PET). PET imaging of radiotracer distribution in living systems provides noninvasive insights into biochemical transactions in vivo. PET relies on molecular probes labelled with positron emitting radionuclides that participate in the process of interest. Coincident detection of 511 keV photons originating from positron-electron annihilation allows for spatial localisation and quantification of the decaying radionuclide in tissue with some accuracy [1–4]. Application of PET in biomedical research, drug development, and clinical imaging creates an immanent need for radiotracers for a variety of biological targets.

The neutron-deficient fluorine isotope 18F is the most frequently employed PET nuclide [5]. This is due to an expedient half-life of 109.7 min, which facilitates commercial distribution of 18F-radiotracers and permits convenient handling of the tracer in multistep reactions and imaging studies [1–3]. Almost exclusive decay via the β + decay branch (97%), paired with a very low positron energy (638 keV), effectively limits the linear range of the emitted positron in water and makes up for the highest image resolution compared to most other PET nuclides. 18F readily forms stable bonds to carbon atoms, which promotes the straightforward introduction of F atoms into most organic molecules. Using the 18O(p,n)18F nuclear reaction, batch production of 370 GBq [18F]fluoride ion (103 human doses) is routinely achievable by irradiation of H2 18O liquid targets. High specific radioactivity (A s; [A s] = Bq/mol; >150 MBq/nmol) is a realistic expectation for radiotracers prepared from [18F]fluoride ion. Likewise, high specific activity (>100 MBq/nmol) is inevitable to maintain genuine tracer conditions for PET-imaging of saturable biological systems [1, 4–7], particularly in small animals but even so in human subjects [8]. As such, high specific activity is a cornerstone of the tracer principle, first introduced by George de Hevesy [1, 6, 9]. In theory, PET may provide the means for noninvasive observation of chemical processes in tissues, exemplified here for receptor binding, as long as the injected amount of the radiotracer does not lead to significant receptor occupation (RO). Receptor occupation is closely linked to pharmacodynamic efficacy and a pharmacological effect can be omitted in cases when the RO is negligible. Figures for insignificant RO have been specified to <1%–5%; nevertheless, it has to be kept in mind that RO is a specific characteristic of a receptor-ligand system and thus may vary from target to target [6, 7, 9]. Hence, the specific activity of each individual radiotracer has to meet the requirements for noninvasive PET imaging. For these reasons, the A s is the most important quality measure for a labelling reaction rather than chemical or radiochemical yield.

Evidently, an abundant motif such as the trifluoromethyl group and its presence in a large number of agrochemicals and biologically active drug molecules is of tremendous interest for the PET community. Consequently, earliest attempts to access this group by nucleophilic and electrophilic radiofluorination protocols date back into the very beginnings of the field of PET chemistry (see Table 1 for an overview).

Table 1.

Survey of radiosynthetic approaches towards the radiosynthesis of [18F]trifluoroalkyl groups.

| Method | Year | Yield/% | As (reported value) comment | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) 18F-19F exchange | 1979 | 0.5–15 | Low—carrier added | Ido et al. [10] |

| (2) Sb2O3 catalysed 18F-Cl substitution | 1986 | 20–50 | Low—carrier added | Angelini et al. [11, 12] |

| (3) 18F-19F exchange | 1990 | 85 | Low—(0.00002–0.002 MBq/nmol) carrier added | Kilbourn and Subramanian [13] |

| (4) 18F-19F exchange | 1993 | 78 | Low—carrier added | Aigbirhio et al. [14] |

| (5) 18F-19F exchange | 1994 | 15–99 | Low—(0.2–16.6 MBq/nmol) [15] carrier added | Satter et al. [16] |

| (6) 18F-Br substitution | 1990 | 17–28 | Low—(0.037 MBq/nmol) precursor separation | Kilbourn et al. [17] |

| (7) 18F-Br substitution | 1993 | 1–4 | Low—(1.5–2.5 MBq/nmol) side reaction | Das and Mukherjee [15] |

| (8) 18F-Br substitution | 1995 | 45–60 | Low—(0.040–0.800 MBq/nmol) side reactions | Johnstrom and Stone-Elander [18] |

| (9) 18F-fluorodesulfurisation | 2001 | 40 | Low—(0.000002 MBq/nmol) carrier added | Josse et al. [19] |

| (10) 18F-Br substitution | 2007 | 10 ± 2 | Low—(4.4 ± 1.5 MBq/nmol) side reactions | Prabhakaran et al. [20] |

| (11) 18F-19F exchange | 2011 | ~60 | Low—carrier added | Suehiro et al. [21] |

| (12) H18F addition | 2011 | 52–93 | Moderate (86 MBq/nmol)—side reaction | Riss and Aigbirhio [22] |

| (13) 18F-I substitution | 2013 | 60 ± 15 | Not given | Van der Born et al. [23] |

| (14) Nucleophilic trapping of difluorocarbene formed in situ and Cu(I) mediated trifluoromethylation with Cu-[18F]CF3 | 2013 | 5–87 | Low—(0.1 MBq/nmol) side reactions | Huiban et al. [24] |

| (15) 18F-I substitution, in situ formation of Cu-[18F]CF3 | 2014 | 12–93 | Low—(0.15 MBq/nmol) side reactions | Ruehl et al. [25] |

| (16) 18F-F2 addition | 2001 | 10–17 | Low—carrier added | Dolbier et al. [26] |

| (17) 18F-F2 disproportionation | 2003 | 22–28 | Low—(0.015–0.020 MBq/nmol) carrier-added | Prakash et al. [27] |

| (18) 18F-selectfluor bis-triflate | 2013 | 9–18 | Low—(3.3 MBq/nmol) carrier-added | Mizuta et al. [28] |

Classical organic chemistry has seen a surge in the development of novel trifluoromethylation strategies and protocols [29–35], owed to the high relevance of the trifluoromethyl motif [36, 37]. However, translation of these most useful and often robust and versatile protocols into radiochemistry is not without difficulties. Indeed, straightforward translation of known organic reactions under stoichiometric conditions into no-carrier-added nucleophilic radiosynthesis often precipitates in adverse findings. Polyfluorinated, organic moieties complicate nucleophilic radiofluorination using 18F-fluoride ion. Under the common conditions used, there is an inherent vulnerability for isotopic dilution of the labelled product with its nonradioactive analogue. Inherently unproblematic exchange processes between carbon-bound 19F and 19F anions in the reaction mixture, which do not confound the final quality of a nonradioactive product, can devastate the specific activity of PET radiotracers [38].

2. Nucleophilic Radiosynthesis

Nucleophilic radiofluorination remained rarely a successful protocol prior to the advent of supramolecular chemistry and the development of potassium selective cryptands. The latter, when combined with mild organic potassium bases and aqueous solutions of 18F− proved to be key to improve the inherently low solubility and reactivity of fluoride ion in dipolar aprotic solvents [39, 40].

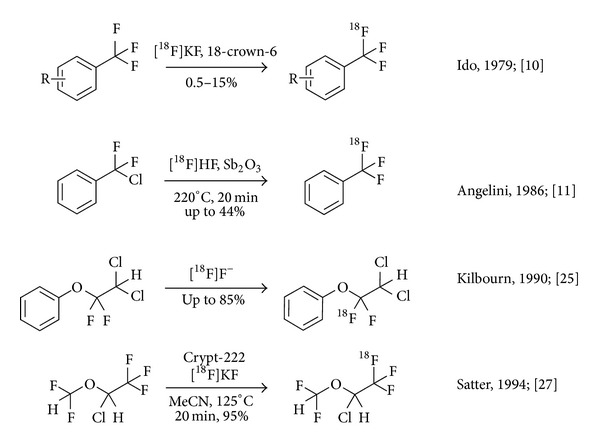

Earliest attempts of developing suitable methodology for the synthesis of the [18F]CF3 group involved transient incorporation of an 18F label into trifluoromethylated scaffolds via 18F-19F isotopic exchange at high temperature as devised by Ido et al. [10]. Shortly thereafter, Lewis acid catalysed dechlorofluorination of chlorodifluoromethyl groups via a straightforward protocol using H18F and Sb2O3 was utilised in the synthesis of 18F-labelled trifluoromethyl arenes [11, 12]. Both of these procedures afforded the desired products in only moderate yields and low specific activity. Nevertheless, isotopic exchange protocols were soon found to be reliable protocols to achieve radiofluorination of di and tri-fluorinated carbon centres, somewhat tolerant to the presence of water [13], albeit with strict limitation for the achievable specific activity, governed by the fact that only a fraction of the obtained carrier-added product will actually contain the radiolabel (see Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Nucleophilic radiosynthesis of 18F-labelled trifluoroalkyl groups using isotopic exchange and antimony mediated 18F-for-Cl substitution.

However, low specific activity may not be an issue in PET studies targeting physical or metabolic processes in vivo, for example, in the case of the mechanisms of action of fast-acting aerosols for anaesthesia. Similarly, radiolabelling of chlorofluorocarbon (CFC) replacement agents such as 1,1,1,2-tetrafluoroethane (HFA 134a) for radiotracer studies does not require particularly high specific radioactivities. This fact was exploited by Satter et al. and Aigbirhio et al. who labelled the CFC replacement agent HFA 134a using an isotopic exchange reaction on the nonradioactive analogue [14, 16, 41, 42]. Satter et al. studied the isotopic exchange between 18F and 19F as a means for the synthesis of ten inhalation anaesthetics, including isoflurane and halothane, all of which possess a trifluoromethyl group. Labelling was achieved by heating the corresponding inhalants with potassium-4,7,13,16,21,24-hexaoxa-1,10-diazabicyclo[8.8.8]hexacosane (crypt-222) cryptate 18F complex in dimethyl sulfoxide or acetonitrile in high yields.

Various reported products were subsequently studied in man, dog, and one compound; namely, [18F]HFA-134a was studied in rat using PET (Figure 1) [42].

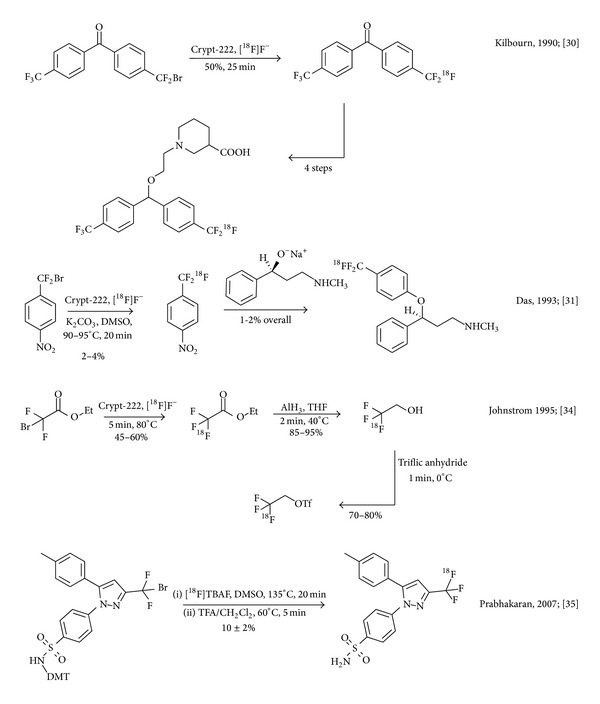

Kilbourn et al. then resorted to a classical 18F-for-Br nucleophilic substitution procedure to obtain [18F]trifluoromethyl arenes under no-carrier-added conditions in an elaborate multistep protocol. These researchers successfully established direct nucleophilic radiofluorination of a suitable difluorobenzylic bromide, which was subsequently employed as a building block in the radiosynthesis of an 18F-labelled GABA transporter ligand. The [18F]trifluoromethylated product was obtained in 17–28% radiochemical yield; decay corrected to the end of bombardment after a synthesis time of 150 minutes over 5 steps. In the original publication, the authors describe that the specific activity in this procedure is confounded by the presence of inseparable labelling precursor which is surmised to act as a biologically active pseudocarrier (Figure 2) [17].

Figure 2.

18F-for-Br nucleophilic substitution protocols yielding the [18F]CF3 motif.

Further insights into the nucleophilic radiofluorination of bromodifluoromethyl-precursors were obtained by Mukherjee and Das in 1993, when the team studied radiolabelling of the selective serotonin uptake inhibitor (S)-N-methyl-γ-[4-(trifluoromethyl)phenoxy]benzenepropanamine (fluoxetine) to obtain [18F]fluoxetine as a potential radiotracer for serotonin transporter binding sites. Radiolabeling of α-bromo-α,α-difluoro-4-nitrotoluene with no-carrier-added [18F]fluoride ion was described in low 2–4% yields and low specific activity of 2.59 MBq/nmol. A strong effect of the reaction temperature on the radiochemical yield and specific activity of the product were studied and a negative correlation between temperature and specific activity was observed. At higher temperatures, products were found to contain a larger amount of nonradioactive carrier, which had been formed in the reaction. Overall decay-corrected yields over 2-steps spanning a total radiosynthesis time of 150–180 min were 1-2%. The specific activity of the product was 1.48 MBq/nmol (Figure 2) [15, 43].

In parallel, Hammadi and Crouzel investigated radiosynthesis of [18F]fluoxetine with [18F]fluoride ion for PET imaging studies [44]. Radiosynthesis was achieved in a decay-corrected radiochemical yield of 9-10% and a specific radioactivity of 3.70–5.55 MBq/nmol within 150 min from the end of bombardment. A competing isotopic exchange reaction was demonstrated, which the authors suspected to reduce the specific activity of the final 18F-labelled product.

Contrary to isotopic exchange reactions, wherein the factors limiting specific activity are evidently linked to the deliberate addition of nonradioactive carrier, the A s limiting factors in the studied nucleophilic substitution reaction are less apparent. Given that a temperature dependency of specific activity was observed by Das and Mukherjee, two principle mechanisms come to mind: (a) dilution through isotopic exchange with the precursor, which would effectively sacrifice 18F to a labelled precursor molecule and yield a 19F fluoride ion that could in itself react with the precursor and (b) degradation of a fluorinated component in the reaction mixture to afford a nonradioactive degradation product and free nonradioactive fluoride ion. However, we refrain from hypothesizing about nonvalidated theories within this paper.

Nevertheless, Johnström and Stone-Elander encountered what appeared to be an example of case (b) during attempts to synthesize the alkylating agent 2,2,2-[18F]trifluoroethyl triflate via the nucleophilic reaction of [18F]F− with ethyl bromodifluoroacetate [18]. These researchers were alerted by the observation of unlabeled ethyl trifluoroacetate produced from ethyl 2-bromo-2,2-difluoro-acetate which reduced the specific activity of the product to only about 0.04 MBq/nmol [38]. Ethyl [18F]trifluoroacetate was synthesized from [18F]F− and ethyl bromodifluoroacetate in DMSO (45–60%, 5 min, 80°C) followed by distillation in a stream of nitrogen. Despite the use of no-carrier-added [18F]F−, the specific activity of the final product was found to be 0.037 MBq/nmol.

Attempts to mitigate the amount of 19F released from the substrate during the reaction were only partially successful. Even under optimised conditions, the specific activity remained below 1 MBq/nmol, which is roughly two to three orders of magnitude below routinely achievable figures associated with direct nucleophilic substitution reactions with [18F]fluoride ion on aliphatic or aromatic carbon centres (Figure 2).

Bromodifluoromethyl precursors were reconsidered in a more recent radiosynthesis of the selective COX-2 inhibitor 4-[5-(4-methylphenyl)-3-([18F]trifluoromethyl)-1H-pyrazol-1-yl]benzenesulfonamide ([18F]celecoxib). [18F]celecoxib was obtained using [18F]TBAF in DMSO at 135°C in 10 ± 2% yield with >99% radiochemical purity and a specific activity of about 4.4 ± 1.5 MBq/nmol (EOB). Although the CNS distribution of [18F]celecoxib mirrored COX-2 expression in the primate brain, the radiotracer was found to be susceptible to defluorination in vivo in rodent and baboon PET studies [20].

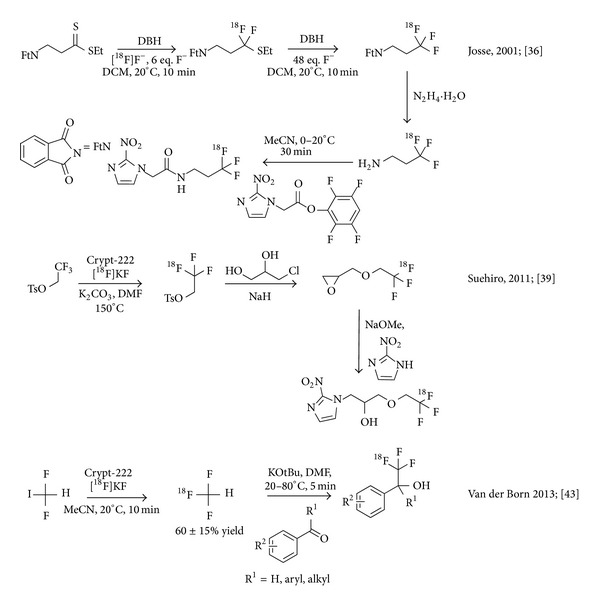

A new approach to obtain the title motif of 18F-labelled trifluorinated carbon centres was introduced by Josse et al. in 2001 and utilized in the synthesis of 18F-labelled 2-(2-nitroimidazol-1-yl)-N-(3,3,3-trifluoropropyl)-acetamide ([18F]EF3), a prospective PET radiotracer for tissue hypoxia. [18F]EF3 was prepared in 3 steps from [18F]fluoride ion via 3,3,3-[18F]trifluoropropylamine. This 18F-labelled building block was obtained in 40% overall chemical yield by oxidative 18F-fluorodesulfurization of ethyl N-phthalimido-3-aminopropane dithioate, subsequent deprotection of the intermediate followed by coupling with 2,3,5,6-tetrafluorophenyl 2-(2-nitroimidazol-1-yl) acetate in 5% radiochemical yield within 90 min from cyclotron produced [18F]fluoride ion [19]. Specific activity of the final product was limited due to the involvement of a stoichiometric fluoride source in the original desulfurization protocol. Later on the protocol was extended to accommodate a wider spectrum of substrates, namely, triethyl orthothioesters and dithioorthoesters (Figure 3) [45].

Figure 3.

Carrier-added radiosynthesis of 18F-labelled hypoxia imaging agents using 18F-fluoro-desulfurisation and 18F-for-19F isotopic exchange and no-carrier-added nucleophilic radiosynthesis of [18F]CHF3.

2-nitroimidazoles, such as [18F]EF3, are used to detect hypoxia, based on the bioreductive metabolism of the nitroimidazole pharmacophore. This metabolism pathway leads to the formation of covalent bioconjugates between intracellular proteins and the imidazole core, which trap the radiotracer within the metabolizing cells. Even though the target compound was obtained in fairly low specific activity, this is not a concern in the study of hypoxia. Indeed, hypoxic tissues can accumulate considerable amounts of substance of nitroimidazoles via an oxygen-level dependent reductive mechanism [46].

Trifluoromisonidazole (1-(2-nitro-1H-imidazol-1-yl)-3-(2,2,2-trifluoroethoxy) propan-2-ol, TFMISO) has been considered as a nuclear magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) agent to visualize hypoxic tissues. TFMISO was successfully labelled with 18F in an attempt to obtain a bimodal PET/MRI probe. In this report, 18F-labeling was achieved via 2,2,2-[18F]trifluoroethyl p-toluenesulfonate prepared by 18F-19F exchange. This reagent was used for O-18F-trifluoroethylation of 3-chloropropane-1,2-diol sodium salt to obtain 1,2-epoxy-3-(2,2,2-[18F]trifluoroethoxy)propane. [18F]TFMISO was obtained in approximately 40% conversion by ring-opening of the epoxide with 2-nitroimidazole. The researchers “identified 2,2,2-[18F]trifluoroethyl tosylate as an excellent [18F]trifluoroethylating agent, which can convert efficiently an alcohol into the corresponding [18F]trifluoroethyl ether” (Figure 3) [21]. Evidently, the isotopic exchange mechanism limited specific activity in congruence with the amount of added carrier.

The utility of an 18F-labelled reagent that could be used as an [18F]trifluoromethyl source for a wide variety of different reactions was recognised by Herscheid et al. who reported several nucleophilic approaches to obtain [18F]trifluoromethyl iodide and [18F]trifluoromethane, respectively, at the biannual symposium of the International Society of Radiopharmaceutical Sciences [47, 48]. This research ultimately resulted in a new strategy towards [18F]trifluoromethyl-containing compounds via [18F]trifluoromethane developed by van der Born et al. Gaseous [18F]trifluoromethane was synthesised in solution at room temperature and trapped in a second reaction vessel. Two further applications of the reagent have been described; [18F]trifluoromethane was subsequently used in a reaction with carbonyl compounds to obtain [18F]trifluoromethyl carbinols in good yields. Unfortunately, the authors did not report a specific activity in their communication. The reagent was furthermore successfully employed in a preliminary study of Cu-mediated 18F-trifluoromethylation; however, no details are available other than a conference abstract (Figure 3) [23, 49].

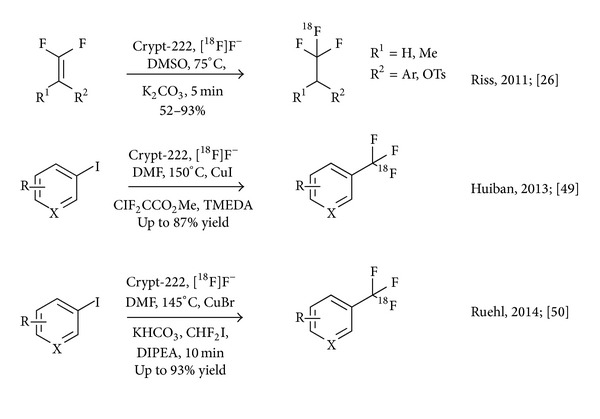

We devised a procedure for the radiosynthesis of aliphatic [18F]trifluoromethyl groups involving the reaction of 1,1-difluorovinyl precursors with [18F]fluoride ion, which results in the equivalent of direct nucleophilic addition of H[18F]F. In theory, this protocol could make a large pool of trifluoroethylated compounds accessible for the straightforward development of PET radiotracers [22, 50, 51]. The protocol was optimised and applied to a set of substrates with moderate to good outcomes, showing that the method is widely applicable for the synthesis of novel radiotracers. Most notably, 2,2,2-[18F]trifluoroethyl p-toluenesulfonate was obtained in high radiochemical yields of up to 93% and good specific activity of 86 MBq/nmol starting from a 5 GBq batch of 18F. Nevertheless, the reaction requires meticulous control of the reaction conditions and the influence of competing elimination reactions has to be mitigated (Figure 4) [50].

Figure 4.

Recent reports on direct nucleophilic radiosynthesis of [18F]trifluoroethyl and [18F]trifluoromethyl groups.

Following the report of an indirect 18F-trifluoromethylation reaction by Herscheid and coworkers, Huiban et al. extended a published protocol for direct trifluoromethylation by Su et al. and MacNeil and Burton to 18F-radiochemistry [52, 53]. The reaction mechanism involves the formation of difluorocarbene from methyl chlorodifluoroacetate in the presence of a fluoride ion source and CuI. Under no-carrier-added conditions, trace amounts of [18F]fluoride ion may only react with a small fraction of the intermediate carbene and form the trifluoromethylating reagent Cu-[18F]CF3, whereas the bulk of the carbene intermediate degrades to side products and 19F fluoride ion. In consequence, the specific activity of the formed product is relatively low (0.1 MBq/nmol). Nevertheless, the method was found to tolerate a variety of substrates and may hence be of use for the study of nonsaturable biological systems (Figure 4) [24].

Seeking an efficient method for producing [18F]trifluoromethyl arenes starting from [18F]fluoride ion within our radiotracer development program, we have explored a route inspired by the use of [18F]fluoroform as an intermediate by van der Born et al. We surmised that reactions involving [18F]fluoroform require diligent control of the gaseous intermediate, including low temperature distillation and trapping of the product at −80°C in a secondary reaction vessel. These conditions and technical requirements are limiting factors with respect to the automated synthesis of high activity batches using automated synthesiser systems. In our eyes, widespread adoption of 18F-trifluoromethylation reactions would strongly benefit from a straightforward nucleophilic one-pot method generally applicable to the latest generation of synthetic hardware. Such methodology would furthermore feature direct installation of nucleophilic fluorine-18 in the form of no-carrier-added [18F]fluoride ion into candidate radiotracers to avoid losses of radioactivity, conserve specific radioactivity, and achieve rapid and simple radiosynthesis. Unfortunately, we were only partially successful; although we have shown that Cu(I) mediated 18F-trifluoromethylation reactions are highly efficient in the presence of a simple combination of difluoroiodomethane, DIPEA, CuBr, 18F−, and an iodo arene, we failed to overcome the known specific activity limitations. Nevertheless, the resulting [18F]trifluoromethyl arenes are obtained in sufficient yields of up to 93% in an operationally convenient protocol, suitable for straightforward automation (Figure 4) [25].

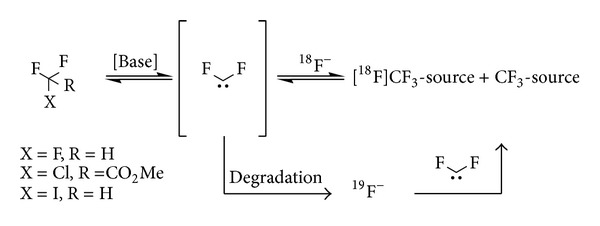

From a mechanistic point of view, the feasibility of the radiosynthesis of [18F]trifluoromethylating agents such as [18F]fluoroform or Cu-[18F]CF3 in high specific activity is questionable. In essence, the generation of the aforementioned labelling reagents would require a clean nucleophilic substitution of an appropriate leaving group, which is not likely to occur. Instead, the generic reaction mechanism involves an α-elimination in the presence of base to yield difluoromethyl carbene, which is subsequently scavenged by [18F]fluoride ion in solution. The inherent low concentration of [18F]fluoride ion, combined with the short half-life of difluorocarbene, which degrades to side products under liberation of two equivalents of 19F in this pathway directly results in isotopic dilution, which confounds achieving a high specific activity. (Figure 5) [24, 25, 52–54].

Figure 5.

Base mediated α-elimination to yield difluoromethyl carbene and subsequent conversion into an 18F-trifluoromethylating reagent.

Likewise, the intermediate organometallic reagents such as Cu-CF3 are unstable in solution; again degradation occurs via a carbenoid pathway. In consequence, several research groups have resorted to the deliberate addition of a soluble source of fluoride ion under stoichiometric conditions to stabilise the equilibrium between the carbene intermediate and the desired reagent, thus adding further indirect proof of the mechanistic difficulties [34, 35].

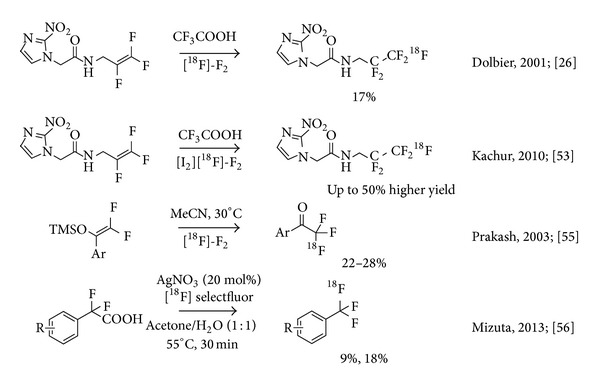

3. Electrophilic Radiosynthesis

Electrophilic methodology has been employed in the synthesis of 18F-labelled perfluoroalkyl moieties, for example, in the radiosynthesis and evaluation of the hypoxia imaging agent 2-(2-nitro-1[H]-imidazol-1-yl)-N-(2,2,3,3,3-[18F]pentafluoropropyl)-acetamide ([18F]EF-5) [26]. EF-5 is a compound belonging to the class of 2-nitroimidazoles. In this case, the requirements for specific activity are fairly forgiving and radiolabelling using electrophilic fluorine sources with low specific activity may be considered as a viable alternative to [18F]fluoride ion. Consequently, stoichiometric reaction conditions are employed and the starting materials are consumed entirely over the course of the labelling reaction. Addition of [18F]F2 to perfluoroolefins appears to be the method of choice in this context and yields up to 17% of [18F]EF-5 have been achieved using carrier-added, gaseous 18F-fluorine (Figure 5). Subsequently, Kachur et al. described an improvement of the electrophilic addition of fluorine to a fluorinated double bond, which was achieved by the addition of catalytic amounts (0.5–1%) of boron trifluoride, bromine, or iodine, to the reaction mixture. Under these conditions the conversion of the labelling precursor to [18F]EF-5 was improved by 50% [55].

More recently, a simplified procedure for radiosynthesis of [18F]EF5 in trifluoroacetic acid (TFA) was devised. This new protocol allowed for straightforward automation of the production using a commercially available radiosynthesis module for routine synthesis of [18F]EF-5 in sufficient amounts and purity for clinical PET studies. An evaluation of the radiotracer was conducted in HCT116 xenografts with small animal PET [56].

Another example of the use of low specific activity 18F-F2 under stoichiometric conditions for the synthesis of the CF3-motif is the syntheses of several 18F-labelled α-trifluoromethyl ketones reported by Prakash et al. [27]. Reactions of 2,2-difluoro-1-aryl-1-trimethylsiloxyethenes with [18F]F2 at low temperature were reported to afford 18F-labelled α-trifluoromethyl ketones in moderate to good yields within 35–40 min from the end of bombardment. Decay-corrected, isolated yields (>99% radiochemical purity) were reported to fall between 22–28% for radiolabeled model compounds. Specific activities ranged from 0.015–0.020 MBq/nmol at the end of synthesis. This method may be of use for the radiochemical synthesis of biologically active 18F-labelled α-trifluoromethyl ketones, however, with strict limitations since such low specific activities may confound tracer conditions for PET imaging of saturable biological processes (Figure 6).

Figure 6.

Electrophilic approaches for the radiosynthesis of the title function.

Nevertheless, electrophilic fluorination may be the key approach to overcome the issues observed with nucleophilic fluorination attempts. This is owed to the availability of somewhat higher specific activity electrophilic labelling reagents derived from [18F]fluoride ion in selected PET centres. A recent report on the reaction of readily available α,α-difluoro- and α-fluoroarylacetic acids with [18F]selectfluor bis(triflate) makes accessible the corresponding [18F]tri- and [18F]difluoromethylarenes in two orders of magnitude higher specific activity compared to [18F]F2.

This straightforward silver(I) catalyzed decarboxylative fluorination reaction afforded a broad range of [18F]trifluoromethyl arenes in moderate to good yields. These researchers reported a specific activity of about 3 MBq/nmol which is about twofold higher than the reported values for nucleophilic fluorination reactions (Figure 6) [28].

4. Conclusion

In conclusion, the trifluoromethyl motif has attracted a veritable interest from PET chemists as a relatively abundant fluorinated functional group, which has precipitated in a variety of novel labelling methods, some of which have been used to synthesise radiotracers for PET imaging studies. The major shortcoming of the available methodology is the low specific activity, which impedes PET imaging of saturable processes and may confound widespread application of these methods. Hence, continued effort may be warranted to overcome the limited scope of the available protocols and extend the knowledge base in PET chemistry with new methodology suitable for the radiosynthesis of 18F-labelled trifluoromethyl groups in high specific activity.

Conflict of Interests

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interests regarding the publication of this paper.

References

- 1.Ametamey SM, Honer M, Schubiger PA. Molecular imaging with PET. Chemical Reviews. 2008;108(5):1501–1516. doi: 10.1021/cr0782426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Miller PW, Long NJ, Vilar R, Gee AD. Synthesis of 11C, 18F, 15O, and 13N radiolabels for positron emission tomography. Angewandte Chemie—International Edition. 2008;47(47):8998–9033. doi: 10.1002/anie.200800222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cai L, Lu S, Pike VW. Chemistry with [18F]fluoride ion. European Journal of Organic Chemistry. 2008;(17):2853–2873. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pike VW. PET radiotracers: crossing the blood-brain barrier and surviving metabolism. Trends in Pharmacological Sciences. 2009;30(8):431–440. doi: 10.1016/j.tips.2009.05.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Meyer G-J, Waters SL, Coenen HH, Luxen A, Maziere B, Langstrom B. PET radiopharmaceuticals in Europe: current use and data relevant for the formulation of summaries of product characteristics (SPCs) European Journal of Nuclear Medicine. 1995;22(12):1420–1432. doi: 10.1007/BF01791152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hume SP, Gunn RN, Jones T. Pharmacological constraints associated with positron emission tomographic scanning of small laboratory animals. European Journal of Nuclear Medicine. 1998;25(2):173–176. doi: 10.1007/s002590050211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hume SP, Myers R. Dedicated small animal scanners: a new tool for drug development? Current Pharmaceutical Design. 2002;8(16):1497–1511. doi: 10.2174/1381612023394412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Virdee K, Cumming P, Caprioli D, et al. Applications of positron emission tomography in animal models of neurological and neuropsychiatric disorders. Neuroscience and Biobehavioral Reviews. 2012;36(4):1188–1216. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2012.01.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jagoda EM, Vaquero JJ, Seidel J, Green MV, Eckelman WC. Experiment assessment of mass effects in the rat: implications for small animal PET imaging. Nuclear Medicine and Biology. 2004;31(6):771–779. doi: 10.1016/j.nucmedbio.2004.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ido T, Irie T, Kasida Y. Isotope exchange with 18F on superconjugate system. Journal of Labelled Compounds and Radiopharmaceuticals. 1979;16(1):153–154. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Angelini G, Speranza M, Shiue C-Y, Wolf AP. H18F + Sb2O3: a new selective radiofluorinating agent. Journal of the Chemical Society, Chemical Communications. 1986;(12):924–925. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Angelini G, Speranza M, Wolf AP, Shiue C-Y. Synthesis of N-(α,α,α-tri[18F[fluoro-m-tolyl)piperazine. A potent serotonin agonist. Journal of Labelled Compounds and Radiopharmaceuticals. 1990;28(12):1441–1448. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kilbourn MR, Subramanian R. Synthesis of fluorine-18 labeled 1,1-difluoro-2,2-dichloroethyl aryl ethers by 18F-for-19F exchange. Journal of Labelled Compounds and Radiopharmaceuticals. 1990;28(12):1355–1361. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Aigbirhio FI, Pike VW, Waters SL, Makepeace J, Tanner RJN. Efficient and selective labelling of the CFC alternative, 1,1,1,2-tetrafluoroethane, with 18F in the 1-position. Journal of the Chemical Society, Chemical Communications. 1993;(13):1064–1065. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Das MK, Mukherjee J. Radiosynthesis of [F-18]fluoxetine as a potential radiotracer for serotonin reuptake sites. Applied Radiation and Isotopes. 1993;44(5):835–842. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Satter MR, Martin CC, Oakes TR, Christian B, Nickles RJ. Synthesis of the fluorine-18 labeled inhalation anesthetics. Applied Radiation and Isotopes. 1994;45(11):1093–1100. doi: 10.1016/0969-8043(94)90189-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kilbourn MR, Pavia MR, Gregor VE. Synthesis of fluorine-18 labeled GABA uptake inhibitors. Applied Radiation and Isotopes. 1990;41(9):823–828. doi: 10.1016/0883-2889(90)90059-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Johnstrom P, Stone-Elander S. The 18F-labelled alkylating agent 2,2,2-trifluoroethyl triflate: synthesis and specific activity. Journal of Labelled Compounds and Radiopharmaceuticals. 1995;36(6):537–547. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Josse O, Labar D, Georges B, Grégoire V, Marchand-Brynaert J. Synthesis of [18F]-labeled EF3 [2-(2-nitroimidazol-1-yl)-N-(3,3,3-trifluoropropyl)-acetamide], a marker for PET detection of hypoxia. Bioorganic and Medicinal Chemistry. 2001;9(3):665–675. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0896(00)00279-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Prabhakaran J, Underwood MD, Parsey RV, et al. Synthesis and in vivo evaluation of [18F]-4-[5-(4-methylphenyl)-3-(trifluoromethyl)-1H-pyrazol-1-yl]benzenesulfonamide as a PET imaging probe for COX-2 expression. Bioorganic and Medicinal Chemistry. 2007;15(4):1802–1807. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2006.11.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Suehiro M, Yang G, Torchon G, et al. Radiosynthesis of the tumor hypoxia marker [18F]TFMISO via O-[18F]trifluoroethylation reveals a striking difference between trifluoroethyl tosylate and iodide in regiochemical reactivity toward oxygen nucleophiles. Bioorganic and Medicinal Chemistry. 2011;19(7):2287–2297. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2011.02.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Riss PJ, Aigbirhio FI. A simple, rapid procedure for nucleophilic radiosynthesis of aliphatic [18F]trifluoromethyl groups. Chemical Communications. 2011;47(43):11873–11875. doi: 10.1039/c1cc15342k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Van Der Born D, Herscheid JDM, Orru RVA, Vugts DJ. Efficient synthesis of [18F]trifluoromethane and its application in the synthesis of PET tracers. Chemical Communications. 2013;49(38):4018–4020. doi: 10.1039/c3cc37833k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Huiban M, Tredwell M, Mizuta S, et al. A broadly applicable [18F]trifluoromethylation of aryl and heteroaryl iodides for PET imaging. Nature Chemistry. 2013;5(11):941–944. doi: 10.1038/nchem.1756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ruehl T, Rafique W, Lien VT, Riss P. Cu(I)-mediated 18F-trifluoromethylation of arenes. Chemical Communications. 2014;50:6056–6059. doi: 10.1039/c4cc01641f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Dolbier WR, Jr., Li A-R, Koch CJ, Shiue C-Y, Kachur AV. [18F]-EF5, a marker for PET detection of hypoxia: synthesis of precursor and a new fluorination procedure. Applied Radiation and Isotopes. 2001;54(1):73–80. doi: 10.1016/s0969-8043(00)00102-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Prakash GKS, Alauddin MM, Hu J, Conti PS, Olah GA. Expedient synthesis of [18F]-labeled α-trifluoromethyl ketones. Journal of Labelled Compounds and Radiopharmaceuticals. 2003;46(11):1087–1092. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mizuta S, Stenhagen ISR, O’Duill M, et al. Catalytic decarboxylative fluorination for the synthesis of Tri- and difluoromethyl arenes. Organic Letters. 2013;15(11):2648–2651. doi: 10.1021/ol4009377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nagib DA, Macmillan DWC. Trifluoromethylation of arenes and heteroarenes by means of photoredox catalysis. Nature. 2011;480(7376):224–228. doi: 10.1038/nature10647. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Deb A, Manna S, Modak A, Patra T, Maity S, Maiti D. Oxidative trifluoromethylation of unactivated olefins: an efficient and practical synthesis of α-trifluoromethyl-substituted ketones. Angewandte Chemie—International Edition. 2013;52(37):9747–9750. doi: 10.1002/anie.201303576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mizuta S, Engle KM, Verhoog S, et al. Trifluoromethylation of allylsilanes under photoredox catalysis. Organic Letters. 2013;15(6):1250–1253. doi: 10.1021/ol400184t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Furuya T, Kamlet AS, Ritter T. Catalysis for fluorination and trifluoromethylation. Nature. 2011;473(7348):470–477. doi: 10.1038/nature10108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mizuta S, Verhoog S, Engle KM, et al. Catalytic hydrotrifluoromethylation of unactivated alkenes. Journal of the American Chemical Society. 2013;135(7):2505–2508. doi: 10.1021/ja401022x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lishchynskyi A, Novikov MA, Martin E, Escudero-Adán EC, Novák P, Grushin VV. Trifluoromethylation of aryl and heteroaryl halides with fluoroform-derived CuCF3: scope, limitations, and mechanistic features. Journal of Organic Chemistry. 2013;78(22):11126–11146. doi: 10.1021/jo401423h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tomashenko OA, Grushin VV. Aromatic trifluoromethylation with metal complexes. Chemical Reviews. 2011;111(8):4475–4521. doi: 10.1021/cr1004293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Yale HL. The trifluoromethyl group in medicinal chemistry. Journal of Medicinal and Pharmaceutical Chemistry. 1959;1(2):121–133. doi: 10.1021/jm50003a001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kirsch P. Modern Fluoroorganic Chemistry: Synthesis, Reactivity, Applications. Weinheim, Germany: John Wiley & Sons; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Johnstrom PS, Stone-Elander S. Strategies for reducing isotopic dilution in the synthesis of 18F-labeled polyfluorinated ethyl groups. Applied Radiation and Isotopes. 1996;47(4):401–407. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hamacher K, Coenen HH, Stocklin G. Efficient stereospecific synthesis of no-carrier-added 2-[18F]-fluoro-2-deoxy-D-glucose using aminopolyether supported nucleophilic substitution. Journal of Nuclear Medicine. 1986;27(2):235–238. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Irie T, Fukushi K, Ido T, Nozaki T, Kasida Y. 18F-Fluorination by crown ether-metal fluoride: (I) on labeling 18F-21-fluoroprogesterone. The International Journal Of Applied Radiation And Isotopes. 1982;33(12):1449–1452. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Nickles RJ, Satter MR, Votaw JR, Sunderland JJ, Martin CC. The synthesis of 18F-labeled potent anesthetics. Journal of Labelled Compounds and Radiopharmaceuticals. 1989;26(1–12):448–449. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Finch JR, Banks WR, Hwang D-R, et al. Synthesis and in vivo disposition studies of 18F-labeled HFA-134a. Applied Radiation and Isotopes. 1995;46(4):241–248. doi: 10.1016/0969-8043(94)00129-n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hammadi A, Crouzel C. Synthesis of [18F]-(S)-fluoxetine: a selective serotonine uptake inhibitor. Journal of Labelled Compounds and Radiopharmaceuticals. 1993;33(8):703–710. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Mukherjee J, Das MK, Yang Z-Y, Lew R. Evaluation of the binding of the radiolabeled antidepressant drug, 18F-fluoxetine in the rodent brain: an in vitro and in vivo study. Nuclear Medicine and Biology. 1998;25(7):605–610. doi: 10.1016/s0969-8051(98)00043-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Cheguillaume A, Gillart J, Labar D, Grégoire V, Marchand-Brynaert J. Perfluorinated markers for hypoxia detection: synthesis of sulfur-containing precursors and [18F]-labelling. Bioorganic and Medicinal Chemistry. 2005;13(4):1357–1367. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2004.11.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Koch CJ, Evans SM. Non-invasive pet and spect imaging of tissue hypoxia using isotopically labeled 2-nitroimidazoles. Advances in Experimental Medicine and Biology. 2003;510:285–292. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4615-0205-0_47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Koolen CL, Herscheid JDM. Approaches towards the radiosynthesis of [18F]trifluoromethyl iodide. Journal of Labelled Compounds and Radiopharmaceuticals. 2001;44(supplement S1):S993–S994. [Google Scholar]

- 48.van der Mey M, Herscheid JDM. [18F]CF3H, a versatile synthon for the preparation of [18F]trifluoromethylated radiopharmaceuticals. Journal of Labelled Compounds and Radiopharmaceuticals. 2007;50(supplemen S1):p. S3. [Google Scholar]

- 49.van der Born D, Herscheid JDM, Vugts DJ. Aromatic trifluoromethylation using [18F]fluoroform. Journal of Labelled Compounds and Radiopharmaceuticals. 2013;56(supplement S1):p. S2. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Riss PJ, Ferrari V, Brichard L, Burke P, Smith R, Aigbirhio FI. Direct, nucleophilic radiosynthesis of [18F]trifluoroalkyl tosylates: improved labelling procedures. Organic and Biomolecular Chemistry. 2012;10(34):6980–6986. doi: 10.1039/c2ob25802a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Riss PJ, Brichard L, Ferrari V, et al. Radiosynthesis and characterization of astemizole derivatives as lead compounds toward PET imaging of τ-pathology. Medicinal Chemistry Communications. 2013;4(5):852–855. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Su D-B, Duan J-X, Chen Q-Y. A simple, novel method for the preparation of trifluoromethyl iodide and diiododifluoromethane. Journal of the Chemical Society—Series Chemical Communications. 1992;(11):807–808. [Google Scholar]

- 53.MacNeil JG, Jr., Burton DJ. Generation of trifluoromethylcopper from chlorodifluoroacetate. Journal of Fluorine Chemistry. 1991;55(2):225–227. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Kirmse W. Carbene Chemistry. 2nd edition. Vol. 1. New York, NY, USA: Academic Press; 1971. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Kachur AV, Dolbier WR, Jr., Xu W, Koch CJ. Catalysis of fluorine addition to double bond: an improvement of method for synthesis of 18F PET agents. Applied Radiation and Isotopes. 2010;68(2):293–296. doi: 10.1016/j.apradiso.2009.10.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Chitneni SK, Bida GT, Dewhirst MW, Zalutsky MR. A simplified synthesis of the hypoxia imaging agent 2-(2-Nitro-1H-imidazol-1-yl)-N-(2,2,3,3,3-[18F]pentafluoropropyl)-acetamide ([18F]EF5) Nuclear Medicine and Biology. 2012;39(7):1012–1018. doi: 10.1016/j.nucmedbio.2012.05.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]