Abstract

Inappropriate or excessive guilt is listed as a symptom of depression by the American Psychiatric Association (1994). Although many measures of guilt have been developed, definitional and operational problems exist, especially in the application of such measures in childhood and adolescence. To address these problems, the current study introduces the Inappropriate and Excessive Guilt Scale (IEGS), assesses its validity for use with children and adolescents, and tests its relation to depression across development. From a sample of 370 children between 7 and 16 years old, results provided (1) evidence that items designed to assess inappropriate and excessive guilt converged onto a single underlying factor, (2) support for the convergent, discriminant, and construct validity of the IEGS in a general youth population, and (3) evidence of incremental validity of the IEGS over-and-above other measures of guilt. Results also supported the hypothesis that inappropriate and excessive guilt as well as negative cognitive errors become less normative and more depressotypic with age.

Keywords: Depression, Guilt, Child, Adolescent, Developmental psychopathology, Assessment, Inappropriate and excessive

The DSM-IV includes inappropriate or excessive guilt as a symptom of depression (American Psychiatric Association, 1994); nevertheless, the measurement of this construct remains problematic, especially in child and adolescent populations. Despite the fact researchers and theoreticians talk about the possibility of guilt being excessive or inappropriate (Harder et al. 1992; Kochanska et al. 1994; O’Connor et al. 1999; Zahn-Waxler et al. 1990), these aspects of guilt are not explicitly assessed by most measures. Among the few measures that attempt to assess the inappropriate aspect of guilt most are embedded in larger instruments that give relatively short shrift to the construct. For example, most diagnostic interviews (e.g., Hamilton 1960; Poznanski et al. 1979; Puig-Antich and Chambers 1978; Spitzer et al. 1992) include very few questions (sometimes only one) about inappropriate guilt. In other measures (like the Guilt and Shame Scale; Cheek and Hogan 1983), item endorsement does not reflect guilt that is necessarily inappropriate. For example, the Guilt and Shame Scale, (Cheek and Hogan 1983) asks respondents to rate how guilty they would feel after, “Buying something I can’t afford.” Although many measures purport to assess the excessive aspect of guilt, what actually qualifies as “excessive” is unclear. For example, the Personal Feelings Questionaire-2 (Harder and Greenwald 1999) assesses the extent to which an individual currently feels guilty, but without norms for this measure it is difficult to determine how high a score must be to qualify as excessive.

When we focus on children, at least four additional problems emerge. First, many attempts to measure guilt in children have focused on the development of morality (Kochanska et al. 2009; Cornell and Frick 2007; Ferguson and Stegge 1995; Kochanska et al. 1994; Williams and Bybee 1994). In these studies, guilt is conceived as a positive construct related to the emergence of moral thinking and behavior. Such measures do not reflect the kind of inappropriate and excessive guilt that is characteristic of depression. Second, childhood is a time when certain kinds of unrealistic or excessive self-blame can be normative (Leitenberg et al. 1986). Nevertheless, many studies of guilt in youths have relied either on adult measures of the construct or upon downward extensions of adult measures without assessing developmental differences in the underlying construct (Harder et al. 1992; Rohleder et al. 2008; Tilghman-Osborne et al. 2008). Third, many guilt researchers have emphasized the contextual nature of guilt and strongly suggested that the assessment of guilt be appropriately contextualized (Tangney 1996). This has typically translated into the use of hypothetical scenarios in the measurement of guilt. Clearly, such scenarios must be age-appropriate. In the same way that the assessment of adaptive guilt has been conducted using age-appropriate scenarios (Tangney et al. 1991; 1990), assessments of maladaptive or depressive guilt should also be conducted using developmentally appropriate contexts. And fourth, popular measures such as the Children’s Negative Cognitive Error Questionnaire (CNCEQ; Leitenberg et al. 1986) or the Children’s Attributional Style Questionnaire (Seligman et al. 1984) do not measure guilt per se. Although they contain subscales that assess children’s tendency to blame themselves for things not necessarily their fault, they only assess the cognitive aspect of guilt, not the affective component that is central in most theoretical definitions of the construct (Tilghman-Osborne et al. 2008). Consequently, the overarching purposes of this study were to create and validate a new measure of inappropriate and excessive guilt for use with children and adolescents.

The measurement of inappropriate and excessive guilt should begin with clear definitions. Unfortunately, Tilghman-Osborne et al.’s (2010) review of guilt definitions and measures found very little theoretical discussion of what constitutes either inappropriate or excessive guilt, and what does emerge varies substantially with the age of the target population. As a starting point, researchers tend to agree that the broader concept of guilt inherently includes a sense of responsibility (Barrett et al. 1993; Caprara et al. 1992; O’Connor et al. 1999; Zahn-Waxler et al. 1990). They define guilt as a combination of negative affect and the belief that one is responsible for a particular outcome. They suggest that guilt becomes inappropriate when it involves “preoccupations or ruminations over minor failings,” with indications that people “have an exaggerated sense of responsibility for untoward events” (DSM-IV TR; APA 2000, p. 350). One such manifestation of guilt occurs when people assume responsibility for outcomes over which they have little or no control.

According to Beck (1967), the incorrect assumption of responsibility for negative events constitutes one of four types of cognitive errors often associated with depression. Leitenberg and colleagues also focused on these kinds of cognitive error. Using the Children’s Negative Cognitive Error Questionnaire, they (and others) found that such cognitive errors were correlated with depression, low self-esteem, anxiety, eating disorders, and poor coping with divorce (Leitenberg et al. 1986; see also Epkins 1996; Mazur et al. 1992; Ostrander et al. 1995; Weems et al. 2001). Based on this work, we define the inappropriate aspect of guilt as the negative cognitions associated with the erroneous assumption of responsibility and the excessive aspect of guilt as the disproportionate negative affect in response to a mishap for which one has assumed such responsibility.

The measurement of inappropriate and excessive guilt in children and adolescents should also be sensitive to developmental changes. Evidence suggests that the relation of depression to inappropriate and excessive guilt may change across development. According to Leitenberg et al. (1986), the negative cognitive errors associated with inappropriate and excessive guilt may be normative for children under 10 years of age. As children’s reasoning abilities mature, cognitive errors become less frequent. They also found that age and negative cognitive errors interact to predict depression, with the relation being stronger among older than younger children. These findings might be explained by cognitive development, in that children’s ability to think hypothetically and take others’ perspectives into consideration matures rapidly during adolescence (Hoffman 1972; Piaget 1964). At younger ages, children tend to view the world in more concrete and less abstract ways. For example, children younger than 10 may perceive a single event as a cause of a single outcome; e.g., “I scribbled on the wall” is a sufficient cause for “Daddy left.” Once formal operational thought develops, children can understand more complicated causal connections, potentially reasoning, “I scribbled on the wall, and daddy and mommy argued which they do a lot. Their arguing is why daddy left” (Grave and Blissett 2004). This developmental shift happens at about the same time as Leitenberg et al. found age-related decreases in negative cognitive error scores, suggesting cognitive errors are less common in older children (1986). We hypothesized that inappropriate and excessive guilt will become less normative with age as children’s capacity for abstract reasoning, information retention, and perspective-taking increase. That is, adolescents will experience less inappropriate and excessive guilt than will children. Further, we hypothesized that the relation of inappropriate and excessive guilt to depression will strengthen with age.

In our development of a new instrument for use with children and adolescents, we had four overarching goals. Our first goal was to avoid the accidental confounding of guilt with other closely related constructs such as depression. Our review of guilt measures (Tilghman-Osborne et al. 2010) found that many existing measures contain items that confound guilt with other constructs, including depression. For example, the Interpersonal Guilt Questionnaire-67 (O’Connor et al. 1997) contains the item, “If I make a mistake I get very depressed.” Differential confounding across measures of guilt may be responsible for the mixed findings among studies that have examined the relation of guilt to depression and other forms of psychopathology. Although some research suggests that guilt is an adaptive construct related to positive outcomes (Tangney et al. 1992), other studies report that guilt is a maladaptive construct associated with negative outcomes (Gullone et al. 2010; Harder and Greenwald 1999). Consequently, one goal of the current study was to design a measure that assessed guilt per se, and not variables with which guilt is presumed to be associated.

A second goal was to avoid the presumption that children inherently know what is inappropriate when it comes to guilt. Simply asking “Do you feel guilty when you should not?” presupposes that the respondent has sufficient perspective to distinguish appropriate from inappropriate guilt (a dubious assumption if one is truly experiencing inappropriate guilt). This type of question will successfully assess guilt only in those who are aware that their guilt is inappropriate. Truly inappropriate guilt may feel very real and justified to children who either have not yet reached a certain level of cognitive development or are so depressed that they are convinced of their inherent guiltiness. Assessing the excessive nature of guilt poses similar challenges. Children’s ability to determine the excessiveness of their guilt experiences may depend on insight and cognitive abilities not yet developed. Likewise, depressed individuals may lack sufficient perspective to judge what is or is not excessive. In creating our measure, we did not rely heavily on a respondent’s ability to recognize the inappropriateness or excessiveness of their guilt experiences. The job of determining the inappropriate and excessive nature of guilt should fall on the researcher, not the respondent.

A third goal was to respect the contextual nature of guilt and yet assess a construct that generalizes across situations. According to Tangney (1996) the assessment of guilt should take into consideration both the within-situation intensity and the across-situation generalizability of guilt by using scenario-based measures. She suggested that each specific question about guilt should be embedded in a situational context; however, the overall assessment should aggregate responses from multiple questions spanning a diversity of such situations. Therefore, in the construction of our measure, we pooled across a wide range of hypothetical scenarios.

Our fourth goal was to avoid social desirability response bias. Robinson et al. (1991) discussed the need to evaluate instruments to counteract respondents’ desire to “appear good.” Social desirability can introduce systematic errors into instruments that can affect what scores on the measure actually represent. Furthermore, as children age, what it means to “appear good” may change, potentially complicating the interpretation of guilt measures at different ages. Robinson et al. suggested that new instruments be evaluated against measures of social desirability. In the current study, we assessed the correlation of our measure with a child social desirability measure.

Our new measure, called the Inappropriate and Excessive Guilt Scale (IEGS), was created with input from both clinicians and researchers whose work involved the assessment of depression and guilt. We designed the measure for use with children ages 7 to 16 with items assessing both the inappropriate and excessive aspects of guilt. With regard to the IEGS, we had eight specific goals. First, we examined the factor structure of the instrument to ascertain whether inappropriate and excessive aspects of guilt constituted one factor or two. Second, we tested whether the IEGS correlated positively with other measures of guilt, negative cognitive errors, and depression. Third, we tested whether the IEGS correlated more highly with maladaptive than adaptive guilt. Fourth, we examined whether the IEGS accounted for unique variance in depressive symptoms over-and–above extant measures of guilt and negative cognitive errors. Fifth, we examined the relation of IEGS to age; expecting inappropriate and excessive guilt to be more normative for younger children than adolescents; i.e., IEGS scores will correlate negatively with age. Sixth, we tested whether the relation of depression to inappropriate and excessive guilt increases with age. Seventh, we sought to replicate Leitenberg et al.’s 1986 findings that depression is more strongly related to negative cognitive errors in adolescents than younger children. Eighth, we examined the relation between IEGS scores and social desirability.

Instrument Creation

To create a measure that assesses the inappropriate and excessive aspects of guilt using multiple questions and a variety of contexts, our approach was to aggregate across a variety of hypothetical, specific scenarios that may elicit inappropriate and excessive aspects of guilt. In the creation of this instrument we focused explicitly on the guilt experience and attempted to avoid contamination from social desirability and other constructs such as depression, anxiety, and somatization. This assessment procedure follows suggestions by Tangney (1996) and Tilghman-Osborne et al. (2010).

Item Generation

Hypothetical scenarios and inappropriate and excessive guilt statements were solicited from clinical psychologists, doctoral candidates in clinical psychology, and other depression assessment experts. The experts were asked to provide thoughts and scenarios reflective of inappropriate and excessive guilt that they had heard from clients and research participants. They were also asked which questions they use when trying to assess inappropriate and excessive guilt in children. This process generated over 50 statements. A team of doctoral candidates in clinical psychology selected 24 hypothetical scenarios that reflected a broad range of situations. For each scenario, they constructed two statements, one reflecting inappropriate guilt and the other reflecting excessive guilt. Each statement was paired with a 3-point Likert scale (0= Not at All, 1= A Little, 2= A Lot).

Piloting the Measure

We piloted the full measure with 25 children between 7 and 14 years of age seeking treatment in an outpatient mental health faculty treating children with internalizing and externalizing disorders. We selected a clinical sample for the pilot to be sure that our measure was sensitive to the more extreme forms of inappropriate and excessive guilt that can arise in various disorders. Participants were asked to read each scenario and corresponding statements of guilt and rate each statement on its 3-point scale. To check the developmental appropriateness of the items, the principal investigator reviewed each scenario with the child asking several questions to ascertain whether they understood the words and thought that the scenarios were realistic. We used this feedback about the clarity of items as well their response frequencies of each item to identify potentially problematic items. We then altered the wording of items for greater clarity, plausibility, and developmental appropriateness of the items. The final instrument, called the Inappropriate and Excessive Guilt Scale (IEGS), is described below.

The IEGS begins with the instructions, “Read these situations carefully and think about how you have been feeling for the last 2 weeks. Imagine that each of these things happened to you. Then mark how you would think or feel if these things did happen to you. There are no right or wrong answers. Just be as honest as possible.” The measure consists of 24 scenarios with negative outcomes and ambiguous fault. An example scenario is, “You are late getting home. Your little brother falls and hurts himself.” Each scenario is followed by two responses that participants are asked to rate: one about inappropriate guilt (e.g., “Would you think: I was late and he got hurt. It is my fault”); the other about excessive guilt (e.g., “Just thinking about what I did would make me want to cry”). Responses are made on 3-point scales with 0= Not at all, 1= A little, and 2= A lot.

Instrument Validation

Participants

A total of 370 children and adolescents participated in this study. Participants attended elementary, middle, or high school (grades 3–10) near a midsize southeastern city. In this school district, most families were of middle to medium-low socio-economic status; approximately 25% of students received free or partially free lunch because of socio-economic need. To recruit students, we distributed 760 consent forms and letters to students to bring home to their parents. Of these, 416 (55%) yielded parent permission. Of the 416 students, 370 (89%) were present on the day of the testing and gave their assent to participate. Participants’ ages were relatively evenly distributed between 7 and 16 years with 21.4% 7–8 years old, 20.0% 9–10 years old, 25.9% 11–12 years old, 15.7% 13–14 years old, and 17.0% 15–16 years old years (M=11.3, SD=3.0). Approximately 58% of the participants were females. The sample was 94% White, 3% Hispanic, 2% African-American, and 1% other, closely reflecting the ethnic distribution of the surrounding county.

Measures

In addition to the IEGS we administered five other instruments. These measures included two measures of guilt, one measure of negative cognitive errors, one measure of depression, and one measure of social desirability.

One of the guilt measures was the Test of Self-Conscious Affect for Children (TOSCA-C; Tangney et al. 1990), a self-report measure comprised of 15 scenarios (10 negative and 5 positive) designed for use with children aged 8–12 years. Each scenario is paired with an illustration and followed by four or five responses that assess guilt, shame, externalization, detachment, alpha pride (feelings of pride in one’s self), and beta pride (feelings of pride in one’s specific behaviors). For this study, only the guilt responses were used in analyses. For an example scenario, “You trip in the cafeteria and spill your friends drink” the guilt-proneness response is, “I would feel sorry, very sorry. I should have watched where I was going.” Responses are rated on 5-point Likert scales (1= not at all likely to 5= very likely). Previous studies of the guilt subscale have provided evidence of moderate internal consistency, test-retest reliability, convergent and discriminant validity, and predictive validity (Robins et al. 2007; Tangney et al. 1996). Although our study extends the age-range beyond the original use of the measure, other studies using have demonstrated reliability with adolescents as well as children (e.g., Ahmed and Braithwaite 2004). The TOSCA-C correlates negatively or negligibly with measures of depressive symptoms (Tangney et al. 1996). In our study, the alpha reliability for the guilt scale was 0.90.

A second guilt measure was the Shame and Guilt Scale (SGS; Alexander et al. 1999). The SGS contains a list of ten scenarios that assess guilt (5 items) and shame (5 items). Only the guilt responses were analyzed in the current study. Example guilt items are “Secretly cheating on something you know will not be found out,” and “To behave unkindly.” Respondents are prompted to “indicate the degree of upset you would experience in each situation.” Responses are rated on 5-point Likert scales. Alexander et al. (1999) reported strong evidence of internal consistency, convergent and discriminant validity, and predictive validity, as well as a clean 2-factor solution for the SGS. The SGS correlates positively with depression symptom measures (Alexander et al. 1999). In our study, the alpha reliability for the guilt scale was 0.79.

The measure of negative cognitive errors used in the present study was the Children’s Negative Cognitive Error Questionnaire (CNCEQ; Leitenberg et al. 1986). The CNCEQ contains 24 hypothetical situations and statements that assess over-generalized predictions of negative outcomes (6 items), catastrophization (6 items), incorrectly taking personal responsibility (6 items), and selectively attending to negative features of outcomes (6 items). An example scenario is, “Your cousin calls you to ask if you would like to go on a long bike ride”. You think, ‘I probably won’t be able to keep up and people will laugh at me’ (catastrophizing). For this study, responses were aggregated and the total CNCEQ scale was used for final analyses. Several studies provide evidence of internal consistency, test-retest reliability, and construct validity for the CNCEQ (Leitenberg et al. 1986; Weems et al. 2001). Leitenberg et al. also published normative data for some age groups. In our study, alpha reliability for the total scale was 0.94.

The social desirability measure was the short form of the Children’s Social Desirability scale (CDS; Tilgner et al. 2004). The CDS contains 24 true-false items. Items are worded such that each item is true for almost every child or almost no child. An example item is, “Sometimes I wish I could just mess around instead of having to go to school.” Answering “false” on the example item (and true on other items) is an indication a tendency to respond in a socially desirable direction. Tilgner et al. provided evidence of test-retest reliability, high levels of internal consistency, and convergent validity of the CDS in child samples. In our study the alpha reliability was 0.82.

To measure depression, we used the Children’s Depression Inventory (CDI; Kovacs 1981). The CDI is a 27-item self-report measure that assesses cognitive, affective, and behavioral symptoms of depression in children. Each item consists of three statements graded in order of increasing severity from 0 to 2. Children select one sentence from each group that best describes themselves for the past 2 weeks. In nonclinic populations, the measure has been shown to have relatively high levels of internal consistency, test-retest reliability, predictive, convergent, and construct validity (Blumberg and Izard 1986; Carey et al. 1987; Kazdin et al. 1983; Lobovits and Handal 1985; Mattison et al. 1990; Saylor et al. 1984; Smucker et al. 1986; Worchel et al. 1990). In our study, we did not include the item assessing suicide, as per the school’s request. The alpha reliability of the CDI without the suicide item was 0.89.

Procedures

Parent consent forms were distributed to students in their classrooms. Parents indicated their consent (or not) and returned the forms to teachers. Teachers were offered $5 per returned form, irrespective of whether the parent granted or denied consent. These monies, which were designated for the purchase of educational materials, served as an incentive for teachers to remind students and parents to return the forms. Doctoral psychology students and advanced undergraduate research assistants administered the questionnaires to consented students. One research assistant read the questionnaires aloud to small groups of 10–25 students, requiring all to proceed at the same pace, irrespective of their reading abilities. The sequence in which the questionnaires were administered was randomized by group in order to minimize the effects of order and fatigue on any instrument. Two to three additional research assistants circulated among the participants answering questions as needed. Each participants was given a $10 gift card to a local department store.

Results

Preliminary Results

Table 1 contains means and SDs for the TOSCA-C, SGS, CNCEQ, CDI, and CSD. These statistics are comparable to those obtained in other studies with similar populations (Alexander et al., Leitenberg et al. 1986; Tangney et al. 1990; Tilgner et al. 2004).

Table 1.

Descriptive statistics for study measures (N=370)

| Measure | Mean | SD |

|---|---|---|

| TOSCA-C Guilt | 49.69 | 13.63 |

| CDI | 8.31 | 7.66 |

| SGS-Guilt | 17.37 | 5.29 |

| CSD | 29.09 | 4.58 |

| CNCEQ Total | 48.55 | 19.19 |

TOSCA-C Guilt Test of Self-Conscious Affect - Child version (Guilt Scale), SGS Shame and Guilt Scale - Guilt Subscale, IEGS Inappropriate and Excessive Guilt Scale, CNCEQ Children’s Negative Cognitive Error Questionnaire, CDI Children’s Depression Inventory, CSD Children’s Social Desirability scale - Short Form

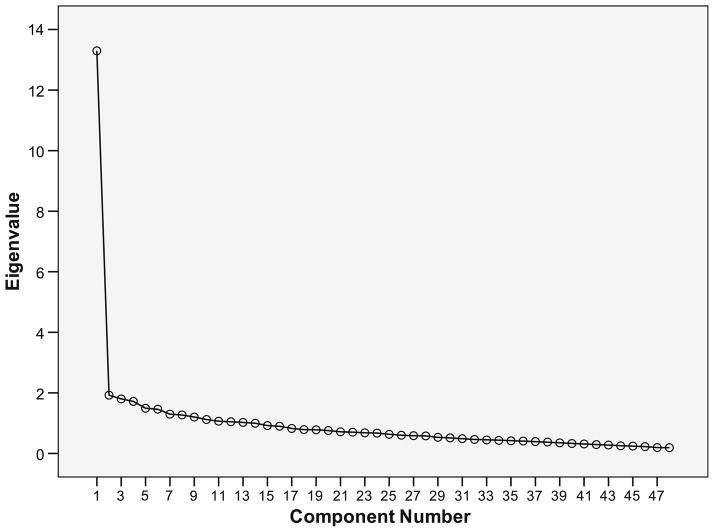

Goal 1: Factor Analysis of the IEGS

An exploratory principal axis factor analysis of the 48 IEGS items provided strong evidence of only one factor (see the scree plot in Fig. 1). Furthermore, when 2 or 3 factors were extracted, virtually all items loaded on the first factor. Taken together, these results suggested that inappropriate guilt items and excessive guilt items load onto a single underlying factor. Factor loadings appear in Table 2. Only the two items associated with scenario 1 had factor loadings less than 0.30 and were thus dropped. The 46 remaining items were used in the calculation of a single total inappropriate and excessive guilt score. The alpha reliability for the scale was 0.94.

Fig. 1.

Scree plot for the factor analysis of the IEGS

Table 2.

Factor loadings of the IEGS items

| Item | Factor Loading |

|---|---|

| 1. You overhear your parents arguing, but cannot make out any of the words they are saying. | |

| In: How much would you think: “It is probably my fault that my parents are arguing.” | 0.27 |

| Ex: Would you feel sick to your stomach because it is your fault? | 0.25 |

| 2. One day when you are not at school, your group of friends gets into trouble. | |

| In: How much would you think: “I usually do the same things that got them into trouble. This is my fault too.” | 0.32 |

| Ex: Would you feel bad because you should have gotten into trouble with them? | 0.35 |

| 3. Your class plays a trivia game and your team loses. | |

| In: Would you think: “I did not get all my questions right, this whole thing is my fault.” | 0.40 |

| Ex: I would not be able to stop thinking about how it is my fault. | 0.44 |

| 4. You and a partner work on a project. You work hard, but your partner goofs off. Your project gets a bad grade. | |

| In: Would you think: “I didn’t work hard enough”. The bad grade is partly my fault. | 0.30 |

| Ex: I would feel guilty for a long time afterwards. | 0.44 |

| 5. There is a lot of traffic on the road, and you end up late for school. | |

| In: Would you think: It is partly my fault. I was late to school. | 0.40 |

| Ex: It would almost hurt to think about what I did. | 0.50 |

| 6. You are late getting home. Your little brother falls and hurts himself. | |

| In: Would you think: “I was late and he got hurt. It is my fault.” | 0.47 |

| Ex: Just thinking about what I did would make me want to cry. | 0.50 |

| 7. You guess the number your teacher was thinking of and get the last chocolate milk. | |

| In: Would you think: “Other people did not get chocolate milk and it is partly my fault.” | 0.46 |

| Ex: This would bother me the rest of the week. | 0.56 |

| 8. You are playing a board game and get a card that says, “send one player back to the beginning of the game.” | |

| In: Would you think: “Other people did not get chocolate milk and it is partly my fault.” | 0.45 |

| Ex: This would bother me the rest of the week. | 0.45 |

| 9. Your friend gets into a lot of trouble at school for talking during class. | |

| In: Would you think: “It is my fault because I was not there to help him.” | 0.38 |

| Ex: I would feel really bad for what I failed to do. | 0.54 |

| 10. You get sick, so your family cannot go to the movies. | |

| In: Would you think: “This is all my fault.” | 0.35 |

| Ex: I would feel so guilty I would have trouble thinking straight. | 0.49 |

| 11. While walking down the hallway, you see your teacher talking to the principal and looking at you. | |

| In: Would you think: “I must have done something wrong.” | 0.37 |

| Ex: I would feel too guilty to look back. | 0.43 |

| 12. You decide to sit in a different seat for class. Someone sitting in your old seat gets hurt when the chair leg breaks. | |

| In: Would you think: “Why did I switch seats? She got hurt because of me.” | 0.63 |

| Ex: It would be hard for me to stop thinking about what I did. | 0.63 |

| 13. You left your homework on the kitchen table and your parents throw it out. | |

| In: Would you think: “It is my fault.” | 0.32 |

| Ex: I would have trouble sleeping just thinking about it. | 0.41 |

| 14. You and a friend are skipping rocks on a pond. Your friend throws his rock at a tree. His rock hits a bird. | |

| In: Would you think: “The bird got hurt because of me.” | 0.45 |

| Ex: I would feel so guilty I wouldn’t want to skip rocks again. | 0.46 |

| 15. You go trick-or-treating for Halloween. You pick a candy that ends up tasting bad. | |

| In: Would you think: “It is my fault. I picked a bad candy.” | 0.30 |

| Ex: In my head, I would keep thinking about it. | 0.37 |

| 16. Your grandparents are away on vacation and forget to send you a birthday card. | |

| In: Would you think: “I did something wrong.” | 0.53 |

| Ex: I would keep thinking of all the bad things I did that might have caused it. | 0.63 |

| 17. You are mad a teacher and don’t want to take her test. You think, “I hope she gets sick” and the next day she does get sick. | |

| In: Would you think: “It is my fault she got sick.” | 0.53 |

| Ex: My heart would feel bad because of what I did. | 0.62 |

| 18. You and your friends are playing basketball and your friends get into a fight. | |

| In: Would you think: “It’s my fault they got in a fight.” | 0.38 |

| Ex: I would feel too guilty to look at my friends. | 0.46 |

| 19. Your friend gets a flat tire on his bike. He is carrying your present to your birthday party. | |

| In: Would you think: “It is my fault his tire is flat.” | 0.46 |

| Ex: My head would almost hurt thinking about how his tire is flat because of my party. | 0.54 |

| 20. Your mother says she wants a certain book for her birthday. You get her that book, but she does not like it. | |

| In: Would you think: “It is my fault, I ruined her birthday.” | 0.51 |

| Ex: I would feel bad every time I saw the book. | 0.61 |

| 21. You and a friend go for a swim, and your friend gets sick. | |

| In: Would you think: “It was my fault he got sick.” | 0.54 |

| Ex: I would be disgusted with myself. | 0.62 |

| 22. You go to a movie with a friend. Your friend got in trouble for not doing her homework. | |

| In: Would you think: “I am to blame for her getting into trouble.” | 0.47 |

| Ex: I would feel so guilty I wouldn’t be able to look at myself. | 0.55 |

| 23. Your mother made your lunch. It leaked all over your homework in your book bag. | |

| In: Would you think: “It’s my fault that my homework got ruined.” | 0.38 |

| Ex: I would think: “I’ll never pack my own bag again.” | 0.39 |

| 24. A game gets stolen from your locker. | |

| In: Would you think: “My parents should be mad at me.” | 0.47 |

| Ex: I would feel really guilty. | 0.58 |

In Inappropriate guilt response, Ex Excessive guilt response

Goal 2: Positive Relation to Other Measures

We hypothesized that the IEGS would correlate positively with other measures of guilt, negative cognitive errors, and depression. As expected, we found positive correlations between the IEGS and the TOSCA-C, SGS, CNCEQ, and CDI. Table 3 shows that the correlations ranged from 0.39 to 0.54.

Table 3.

Correlations among study measures

| Instrument | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. IEGS | 1 | |||||

| 2. TOSCA-C | 0.52** | 1 | ||||

| 3. SGS | 0.43** | 0.62** | 1 | |||

| 4. CNCEQ | 0.54** | 0.38** | 0.24** | 1 | ||

| 5. CDI | 0.39* | 0.12* | 0.05 | 0.52** | 1 | |

| 6. CSD | −0.05 | 0.03 | 0.12* | −0.27** | −0.28** | 1 |

TOSCA-C Test of Self-Conscious Affect - Child version (Guilt Scale), SGS Shame and Guilt Scale - Guilt Subscale, IEGS Inappropriate and Excessive Guilt Scale, CNCEQ Children’s Negative Cognitive Error Questionnaire, CDI Children’s Depression Inventory, CSD Children’s Social Desirability scale - Short Form

p<0.05,

p<0.01

Goal 3: The IEGS Will Be More Highly Associated with Maladaptive Guilt than Adaptive Guilt

We did not find support for the hypothesis that the IEGS would correlate more highly with the SGS (our measure of maladaptive guilt) than with the TOSCA-C (our measure of adaptive guilt). The correlation between the IEGS and SGS (r=0.43) was not significantly different from the correlation between the IEGS and the TOSCA-C (r=0.52), Fisher’s z ratio=1.63 (p>0.05).

Goal 4: Incremental Prediction of Depressive Symptoms

As a preliminary step we compared zero-order correlations using Fischer’s z ratios. We found that the CDI correlated more strongly with the IEGS (r=0.39) than it did with the TOSCA-C (r=0.12, z=3.42, p<0.01) and the SGS (r=0.05, z=8.20, p<0.01) but not with the CNCEQ (r=0.45, z=NS). We then conducted multiple regression analyses to test the incremental utility of the IEGS over-and-above two other guilt measures in the prediction of depressive symptoms. In step 1, we regressed depressive symptoms (CDI) onto the SGS and TOSCA-C. The R2 was not significant (p>0.05). In step 2, adding the IEGS made a significant contribution to the prediction of CDI scores over-and-above the two other guilt measures (β=0.46, ΔR2=0.15, ΔF(1,366) =63.10, p<0.001; see upper panel of Table 4). In a second set of regressions, we tested the incremental validity of the IEGS over-and-above the two guilt measures and the personalization subscale of the CNCEQ (the subscale measuring the cognitive errors most associated with inappropriate guilt). In step 1, we regressed depressive symptoms (CDI) onto the SGS, TOSCA-C, and CNCEQ subscale. The R2 was significant. In step 2, adding the IEGS contributed significantly to the prediction of CDI scores over-and-above the other three measures (β=0.29, ΔR2=0.05, ΔF(1,366) =23.48, p <0.001; see lower panel of Table 4).

Table 4.

Multiple regression: effect of IEGS on depressive symptoms controlling for TOSCA-Guilt, SGS-Guilt, and/or CNCEQ

| Step | Predictor | B | SE (B) | β | R2 | ΔR2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IEGS controlling for TOSCA and SGS | ||||||

| 1 | intercept | 5.36 | 1.59 | |||

| TOSCA-Guilt | 0.08* | 0.04 | 0.15 | |||

| SGS-Guilt | −0.07 | 0.10 | −0.05 | 0.02 | 0.02 | |

| 2 | intercept | 7.49 | 1.49 | |||

| TOSCA-Guilt | −0.02 | 0.04 | −0.04 | |||

| SGS-Guilt | −0.19* | 0.09 | −0.13 | |||

| IEGS | 0.23*** | 0.03 | 0.46 | 0.17*** | 0.15*** | |

| IEGS controlling for TOSCA, SGS, and CNCEQ | ||||||

| 1 | intercept | 2.23 | 1.47 | |||

| TOSCA-Guilt | −0.02 | 0.04 | −0.04 | |||

| SGS-Guilt | −0.08 | 0.09 | −0.05 | |||

| CNCEQ-per | 0.68*** | 0.08 | 0.48 | 0.21*** | 0.21*** | |

| 2 | Intercept | 4.34 | 1.49 | |||

| TOSCA-Guilt | −0.06 | 0.04 | −0.11 | |||

| SGS-Guilt | −0.15 | 0.09 | −0.11 | |||

| CNCEQ-per | 0.52*** | 0.08 | 0.36 | |||

| IEGS | 0.15*** | 0.03 | 0.29 | 0.26*** | 0.05*** | |

TOSCA Test of Self-Conscious Affect - Child version, SGS Shame and Guilt Scale, IEGS Inappropriate and Excessive Guilt Scale, CNCEQ-per Children’s Negative Cognitive Error Questionnaire (Personalizing subscale)

p<0.05,

p<0.01,

p<0.001

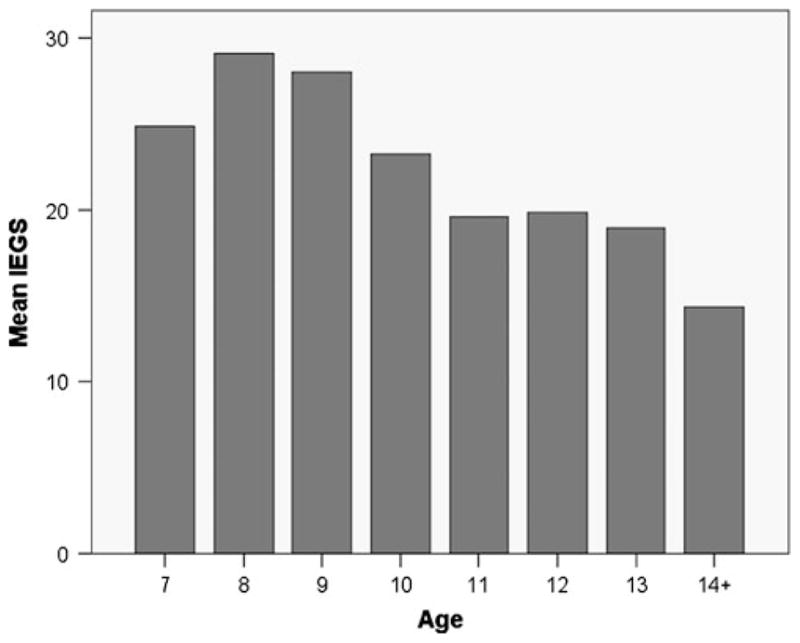

Goal 5: Inappropriate and Excessive Guilt Will Be More Normative for Younger Children

We found support for the age-related hypotheses that IEGS scores would be lower for older children. The correlation between age and IEGS was negative (r=−0.28, p<0.01). In Fig. 2, we see that the mean IEGS scores diminished with age.

Fig. 2.

Mean IEGS scores by age

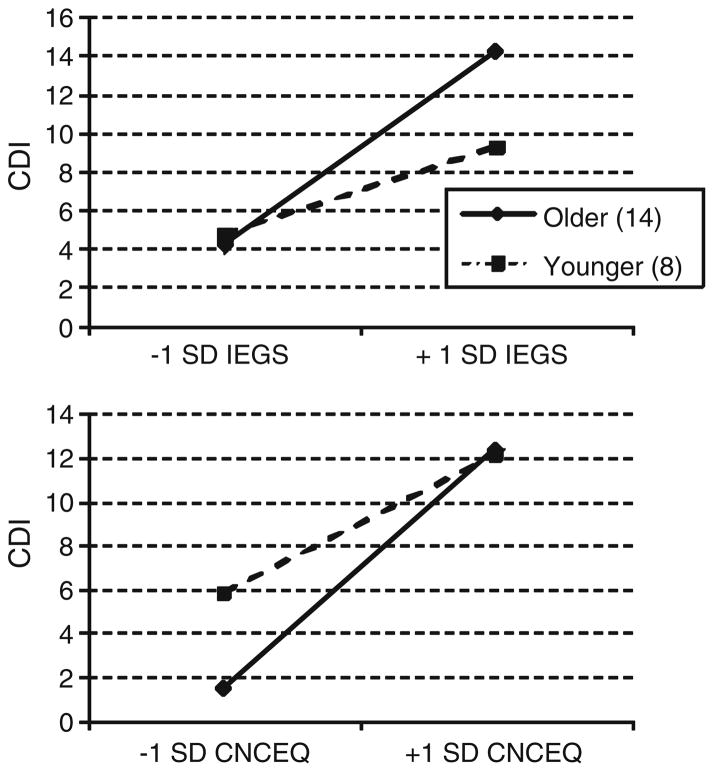

Goal 6: Interaction between Age and IEGS

We hypothesized that the IEGS would interact with age to predict CDI scores such that the strength of relation between the IEGS and the CDI would be greater for older children than younger children. We conducted a multiple regression analysis with depression (CDI) as the dependent variable, and Age (in years), IEGS, and the Age × IEGS interaction as the independent variables: CDI=β0 + β1 Age+β2 IEGS+ β3 (Age × IEGS). Controlling for the main effects of Age and IEGS, the interaction effect was significant and positive (β3 =0.58, p<0.05; see upper panel of Table 5). When plotted, the slope for the relation between the IEGS and the CDI was positive and greater for older children than for younger children (see Fig. 3). Regions of significance calculations (e.g., Aiken and West 1991; Bauer and Curran 2005; Cohen et al. 2003) revealed that the partial slope for IEGS was significant (at p<0.05) at all values of age represented in the sample (nb. the lower bound for the region of significance was 6.45, less than the lowest age in the sample).

Table 5.

Multiple regressions testing age as a moderator of either the IEGS or CNCEQ on depressive symptoms (CDI)

| Predictor | B | SE (B) | β | R2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Testing Age as moderator of the IEGS - CDI relation | ||||

| Intercept | 6.64 | 3.52 | ||

| Age | −0.29 | 0.33 | −0.08 | |

| IEGS | −0.09 | 0.15 | −0.18 | |

| IEGS × Age | 0.03* | 0.02 | 0.58 | 0.17* |

| Testing Age as moderator of the CNCEQ - CDI relation | ||||

| Intercept | 11.51 | 5.15 | ||

| Age | −1.32** | 0.50 | −0.35 | |

| CNCEQ | 0.01 | 0.09 | 0.01 | |

| CNCEQ × Age | 0.02* | 0.01 | 0.61 | 0.28** |

IEGS Inappropriate and Excessive Guilt Scale, CNCEQ Children’s Negative Cognitive Error Questionnaire, CDI Children’s Depression Inventory

p<0.05,

p<0.01

Fig. 3.

Interactions of age with guilt (IEGS) and cognitive errors (CNCEQ) predicting depressive symptoms (CDI)

Goal 7: Interaction between Age and Negative Cognitive Errors

We hypothesized that the relation between depression and negative cognitive errors would be stronger for adolescents than younger children. To test this hypothesis, we regressed CDI scores onto Age, CNCEQ, and the Age × CNCEQ interaction. The Age × CNCEQ interaction was significant (β=0.61, p<0.01, see lower panel of Table 5). The plot was similar to that of the IEGS insofar as the CNCEQ was more strongly associated with depressive symptoms for older children than younger children (see Fig. 3). Regions of significance calculations revealed that the partial slope for the CNCEQ was significant (at p<0.05) at all values of age represented in the sample (nb. the lower bound for the region of significant was 4.83, less than the lowest age in the sample).

Goal 8: IEGS is Not Correlated with Social Desirability

We hypothesized that the IEGS scores would not be affected by social desirability response style. Toward this end, we found that the correlation between CSD and the IEGS was small and not statistically significant (r=−0.05). As a matter of comparison, the SGS and CNCEQ (but not the TOSCA) had significant correlations with the CSD (see Table 3).

Discussion

Four major findings emerged from this study. First, factor analysis revealed that IEGS items on inappropriate guilt and on excessive guilt loaded onto a single underlying factor. Second, we found evidence supporting convergent, discriminant, and construct validity of the IEGS. Third, we found evidence of incremental validity, insofar as the IEGS correlated with depressive symptoms over-and-above two commonly used measures of guilt and a measure of negative cognitive errors. Fourth, we found significant support for our developmental hypotheses that both guilt and negative cognitive errors are more normative for younger children but more highly correlated with depressive symptoms for older children. We elaborate on each of these findings below and discuss their clinical implications.

First, factor analysis revealed that items designed to assess inappropriate guilt and excessive guilt (separately) actually loaded onto a single factor. The discovery of a single underlying factor suggests that inappropriate and excessive guilt constitute two aspects of the same underlying construct. In other words, children and adolescents may not typically be able to experience inappropriate guilt without also experiencing excessive guilt and vice versa. This finding has three potential implications for practice and research. One pertains to diagnosis. For diagnosing depression, the DSM-IV TR states that either excessive or inappropriate guilt is sufficient to qualify the individual as having the cognitive symptom of depression (APA 2000). Our findings reveal that inappropriate and excessive aspects of guilt co-occur to such a degree as to obscure their distinction. Another clinical implication pertains to treatment. In treating depression, clinicians often use cognitive strategies such as cognitive behavioral therapy to identify and reduce maladaptive thoughts and cognitive errors. By helping to reduce such cognitive errors, clinicians may also effectively reduce the overall level of guilt in their clients. Finally, researchers who have examined negative and maladaptive forms of guilt generally have not distinguished between the inappropriate and excessive aspects of this construct (see Harder et al. 1992; Kochanska et al. 1994; O’Connor et al. 1999; Zahn-Waxler et al. 1990). Our results support this research approach, suggesting that children and adolescents who experience excessive guilt tend to feel guilty about things that are not truly their fault, and that people who blame themselves inappropriately tend also to feel guilt more intensely.

Second, we found evidence of convergent, discriminant, and construct validity of the IEGS. Supporting convergent validity, the IEGS significantly correlated with other measures of guilt. Supporting discriminant validity, the IEGS was not related to a measure of social desirability indicating that participants’ responses were not excessively affected by positive response bias. Supporting construct validity, the IEGS was significantly related to measures of negative cognitive errors and depression. Many theoreticians and researchers have suggested that guilt can be either adaptive (motivating positive outcomes) or maladaptive (motivating negative outcomes: Alexander et al. 1999; Harder 1995; Kugler and Jones 1992; O’Connor et al. 1999; Williams and Bybee 1994). For example, Harder and Greenwald (1999) suggested that transient feelings of “guilt facilitate adaptive self-control, prosocial behaviors, and the repair of ruptures in relationships”; however, when guilt becomes chronic, it can be maladaptive (p. 271). In their study of young children, Zahn-Waxler et al. (1990) claimed “different patterns of adaptive and maladaptive guilt already appeared to be present by the end of preschool years” (p. 57). Many of the existing measures of guilt that have been developed for use with children tend to focus more on adaptive forms of guilt (Tangney et al. 2000; Tangney et al. 1991; Tangney et al. 1990). For clinicians and researchers interested in the assessment of maladaptive guilt in young people, our IEGS warrants consideration.

Third, the IEGS demonstrated incremental utility in relation to depression. The IEGS correlated with depressive symptoms over-and-above two measures of guilt (plus one measure of negative cognitive errors). Furthermore, the IEGS did not correlate with social desirability (unlike several other measures). Most extant measures of guilt do little to distinguish healthy, appropriate, and adaptive guilt from inappropriate and maladaptive guilt. Explicitly created to assess inappropriate and excessive guilt, the IEGS appears to account for variance in depression that is not captured by more conventional measures. An important future direction would be to examine the predictive utility of the IEGS in relation to other dimensions of psychopathology as well. Because previous research has shown that cognitive errors about perceived responsibility correlate with anxiety, eating disorders, and poor coping (Epkins 1996; Leitenberg et al. 1986; Mazur et al. 1992; Ostrander et al. 1995; Weems et al. 2001), we would expect the IEGS to be useful in the prediction of a variety of child and adolescent disorders.

Fourth, our developmental findings showed that both inappropriate/excessive guilt and negative cognitive errors are more common among younger children but more depressive among older children. These findings replicate previous research (Grave and Blissett 2004; Leitenberg et al. 1986), which found (a) that mean levels of negative cognitive errors were higher for younger children than older children and (b) that the relation of negative cognitive errors to depression was stronger for older children. The current study extends previous knowledge insofar as inappropriate/excessive guilt (as measured by the IEGS) mirrored these results: (a) mean levels of inappropriate and excessive guilt were higher among younger than older children and (b) the relation of inappropriate and excessive guilt to depressive symptoms was stronger for older children than younger. Elevated levels of inappropriate and excessive guilt in younger children may be partially a function of typical development—at least in the well-socialized child. A higher threshold may be needed before taking children’s inappropriate and excessive guilt as an indication of depression. Conversely, when inappropriate and excessive guilt occurs in older children or adolescents, it may be less normative and more clearly reflective of depression.

Our finding that inappropriate and excessive guilt is more common at younger ages does not mean that this kind of thinking can be ignored in treatment. The relation between depression and inappropriate/excessive guilt may have been stronger for older children, but it was still significant for younger children. Even in younger children, inappropriate and excessive guilt was associated with depression. Although cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) may be an appropriate method for treating cognitive errors associated with depression and anxiety in children and adolescents (Harrington et al. 1998; Kendall 1994), various developmental factors must be taken into account when applying CBT to children, as noted by Grave and Blissett (2004). Key CBT goals (such as the identification of cognitive distortions, challenging them, and replacing them with more rational thinking) may require “self-reflection, perspective taking, understanding causality, reasoning and processing new information, as well as linguistic ability and memory” (Grave and Blissett 2004, p. 402). They argued that children who have not attained formal operational thought may not have reached a level of development sufficient to handle the cognitive demands required of CBT. Some researchers have addressed this problem successfully by increasing parental involvement in treatment (Creswell and O’Connor 2011; Weisz and Chorpita; 2011); however, how cognitive problems such as inappropriate and excessive guilt should be addressed in modern, developmentally-appropriate therapies remains an important area for future research.

Several shortcomings of this study suggest still other possibilities for future research. First, the IEGS did not correlate more highly with the SGS (a measure of maladaptive guilt), than it did with the TOSCA-C (a measure of adaptive guilt). This result may reflect the possibility that the SGS does not actually tap a highly maladaptive form of guilt. One possible issue with the SGS is that the items focus on how upset one might feel in situations that probably should induce guilt (e.g., “You behave unkindly,” “You hurt someone’s feelings”). Consequently, high scores on the instrument may not necessarily reflect guilt feelings that are highly inappropriate. Interestingly, Alexander et al. (1999) did report a positive correlation between the SGS and measures of depression; however, their work focused on a relatively depressed clinical sample. In such a sample, scores on the SGS would likely be elevated despite the use of scenarios for which guilt would not be an inappropriate response. Additionally, the SGS correlated positively with social desirability, indicating that its items may be subject to positive response bias. Extending use of the IEGS into clinical samples is an important direction for future research.

Second, we validated our instrument of inappropriate and excessive guilt against other paper-and-pencil measures of guilt, depression, and negative cognitive errors. Future research should validate the measure against qualitatively different methods such as semi-structured interviews or even behavioral observation methods (e.g., Barrett et al. 1993; Kochanska et al. 1994). High correlations among such dissimilar methods for measuring inappropriate and excessive guilt would provide stronger evidence of convergent validity.

Third, our findings were based on cross-sectional correlations and regression analyses. Longitudinal studies could explore the predictive relations between depressive symptoms and inappropriate and excessive guilt. Cole et al. (1998) found weak longitudinal support for the hypothesis that negative cognitive errors predicted depression. Focusing on inappropriate and excessive guilt (not just cognitive errors) and assessing these constructs with multiple measures could yield stronger longitudinal results.

Finally, when the current study revealed age to be a moderator of the relation between depression and guilt, we suggested that the results might be due to age-related changes in cognitive development. Age, however, is a relatively crude proxy for other aspects of cognitive development (Siegler 1996). Similarly, other demographics could also moderate some of the current effects, a possibility that was impossible to explore in the current study (94% Caucasian). An important avenue for future research would be to measure cognitive development (as well as other developmental variables) more directly, and to sample a greater diversity of participants, in order to clarify what processes may underlie and moderate the age effects revealed in the current study.

In conclusion, this study introduced the first instrument that clearly and explicitly measures inappropriate and excessive guilt in children and adolescents. This measure will enhance researchers’ ability to investigate the mal-adaptive side of guilt and help clinicians to understand more about depressive guilt in children and adolescents. We found significant evidence supporting the validity of the IEGS and empirical support for age-related changes in the relation of depression to inappropriate and excessive guilt.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by a gift from Patricia and Rodes Hart, by support from the Warren Family Foundation, and by NICHD 1R01HD059891

References

- Ahmed E, Braithwaite V. “What me ashamed?” Shame management and school bullying. Journal of Research in Crime and Delinquency. 2004;41:269–292. [Google Scholar]

- Aiken LS, West SG. Multiple regression: Testing and interpreting interactions. Thousand Oaks: Sage; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Alexander B, Brewin CR, Vearnals S, Wolff G, Leff J. An investigation of shame and guilt in a depressed sample. The British Journal of Medical Psychology. 1999;72:323–338. doi: 10.1348/000711299160031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- APA. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders: DSM-IV. Washington: American Psychiatric Association; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- APA. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders: DSM-IV TR. 4. Washington: American Psychiatric Association; 2000. Text Revision. [Google Scholar]

- Barrett KC, Zahn-Waxler C, Cole PM. Avoiders vs. amenders: Implications for the investigation of guilt and shame during toddlerhood. Cognition and Emotion. 1993;7:481–505. [Google Scholar]

- Bauer DJ, Curran PJ. Probing interactions in fixed and multilevel regression: Inferential and graphical techniques. Multivariate Behavioral Research. 2005;40:373–400. doi: 10.1207/s15327906mbr4003_5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beck AT. Depression: Clinical, experimental, and theoretical aspects. New York: International Universities Press; 1967. [Google Scholar]

- Blumberg SH, Izard CE. Discriminating patterns of emotions in 10- and 11-yr-old children’s anxiety and depression. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1986;51:852–857. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.51.4.852. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caprara GV, Manzi J, Perugini M. Investigating guilt in relation to emotionality and aggression. Personality and Individual Differences. 1992;13:519–532. [Google Scholar]

- Carey MP, Faulstich ME, Gresham FM, Ruggiero L, Enyart P. Children’s depression inventory: Construct and discriminant validity across clinical and nonreferred (control) populations. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1987;55:755–761. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.55.5.755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheek JM, Hogan R. Self-concepts, self-presentations, and moral judgments. In: Suls J, Greenwald AG, editors. Psychological perspectives on the self. Vol. 2. Hillsdale: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; 1983. pp. 249–273. Cole, J. Preston. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen J, Cohen P, West SG, Aiken LS. Applied multiple regression/correlation analysis for the behavioral sciences. 3. Hillsdale: Erlbaum; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Cole DA, Martin JM, Peeke LG, Seroczynski AD, Hoffman K. Are cognitive errors of underestimation predictive or reflective of depressive symptoms in children: A longitudinal study. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1998;107:481–496. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.107.3.481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cornell AH, Frick PH. The moderating effects of parenting styles in the association between behavioral inhibition and parent-reported guilt and empathy in preschool children. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychopathology. 2007;36:305–318. doi: 10.1080/15374410701444181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Creswell C, O’Connor TG. Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy for children and adolescents. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2011;265 [Google Scholar]

- Epkins CC. Cognitive specificity and affective confounding in social anxiety and dysphoria in children. Journal of Clinical Psychology. 1996;18:83–101. [Google Scholar]

- Ferguson TJ, Stegge H. Emotional states and traits in children: The case of guilt and shame. In: Tangney JP, Fischer KW, editors. Self-conscious emotions the psychology of shame, guilt, embarrassment, and pride. New York: The Guilford Press; 1995. pp. 174–197. [Google Scholar]

- Grave J, Blissett J. Is cognitive behavior therapy developmentally appropriate for young children. Clinical Psychology Review. 2004;24:399–420. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2004.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gullone E, Hughes EK, King NJ, Tonge B. Shame and guilt in preschool depression: Evidence for eleveations in self-consciouis emtoins in depression as early as age 3. Journal of Child Pscyhology and Psychiatry. 2010;51:567–574. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2009.02183.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamilton M. A rating scale for depression. Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery, and Psychiatry. 1960;12:56–62. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.23.1.56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harder DW. Shame and guilt assessment, and relationships of shame- and guilt-proneness to psychopathology. In: Tangney JP, Fischer KW, editors. Self-conscious emotions the psychology of shame, guilt, embarrassment, and pride. New York: The Guilford Press; 1995. pp. 368–392. [Google Scholar]

- Harder DW, Greenwald DF. Further validation of the shame and guilt scales of the harder personal feelings questionnaire-2. Psychological Reports. 1999;85:271–281. doi: 10.2466/pr0.1999.85.1.271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harder DW, Cutler L, Rockart L. Assessment of shame and guilt and their relationship to psychopathology. Journal of Personality Assessment. 1992;59:584–604. doi: 10.1207/s15327752jpa5903_12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harrington R, Wood A, Verduyn C. Clinically depressed adolescents. In: Graham P, editor. Cognitive–behavior therapy for children and families. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 1998. pp. 156–188. [Google Scholar]

- Hoffman ML. Empathy, role-taking, guilt, and development of altruistic motives. Paper presented at the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development Workshop; Elkridge, MD. 1972.1972. [Google Scholar]

- Kazdin AE, French NH, Unis AS. Child, mother, and father evaluations of depression in psychiatric inpatient children. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 1983;11:167–180. doi: 10.1007/BF00912083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kendall PC. Treating anxiety disorders in children: Results of a randomized clinical trial. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1994;62:100–110. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.62.1.100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kochanska G, DeVet K, Goldman KM, Murray K, Putnam SP. Maternal reports of conscience development and temperament in young children. Child Development. 1994;65:852–868. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kochanska G, Barry RA, Jiminez NB, Hollatz JW, Woodard J. Guilt and effortful control: two mechanisms that prevent disruptive developmental trajectories. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2009;97:322–333. doi: 10.1037/a0015471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kovacs M. Rating scales to assess depression in school aged children. Acta Paedopsychiatrica. 1981;46:305–315. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kugler K, Jones WH. On conceptualizing and assessing guilt. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology. 1992;62:318–327. [Google Scholar]

- Leitenberg H, Yost LW, Carroll-Wilson M. Negative cognitive errors in children: Questionnaire development, normative data, and comparisons between children with and without self-reported symptoms of depression, low self-esteem, and evaluation anxiety. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1986;54:528–536. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.54.4.528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lobovits DA, Handal PJ. Childhood depression: Prevalence using DSM-III criteria and validity of parent and child depression scales. Journal of Pediatric Psychology. 1985;10:45–54. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/10.1.45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mattison RE, Handford HA, Kales HC, Goodman AL, McLaughlin RE. Four-year predictive value of the children’s depression inventory. Psychological Assessment. 1990;2:169–174. [Google Scholar]

- Mazur E, Wolchik SA, Sandler IN. Negative cognitive errors and positive illusions for negative divorce events: Predictors of children’s psychological adjustment. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 1992;20:523–542. doi: 10.1007/BF00911238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Connor LE, Berry JW, Weiss J, Bush M, Sampson H. Interpersonal guilt: The development of a new measure. Journal of Clinical Psychology. 1997;53:73–89. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-4679(199701)53:1<73::aid-jclp10>3.0.co;2-i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Connor LE, Berry JW, Weiss J. Interpersonal guilt, shame, and psychological problems. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology. 1999;18:181–203. [Google Scholar]

- Ostrander R, Nay WR, Anderson D, Jensen J. Developmental and symptom specificity of hopelessness, cognitive errors, and attributional bias among clinic-referred youth. Child Psychiatry and Human Development. 1995;26:97–112. doi: 10.1007/BF02353234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piaget J. Part I: Cognitive development in children: Piaget development and learning. Journal of Research in Science Teaching. 1964;2:176–186. [Google Scholar]

- Poznanski EO, Cook SC, Carroll BJ. A depression rating scale. Pediatrics. 1979;64:442–450. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Puig-Antich J, Chambers W. The Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia for School-age Children (Kiddie-SADS) New York State Psychiatric Institute; New York: 1978. Unpublished manuscript. [Google Scholar]

- Robins RW, Noftle EE, Tracy JL. Assessing self-conscious emotions. In: Tracy JL, Robins RW, Tangney JP, editors. The self conscious emotions. New York: The Guilford Press; 2007. pp. 443–467. [Google Scholar]

- Robinson JP, Shaver PR, Wrightsman LS. Criteria for scale selection and evaluation. In: Robinson JP, Shaver PR, Wrightsman LS, editors. Measures of personality and social psychological attitudes. San Diego: Academic; 1991. pp. 1–16. [Google Scholar]

- Rohleder N, Chen E, Wolf JM, Miller GE. The psychobiology of trait shame in young women: Extending the social self preservation theory. Health Psychology. 2008;5:523–532. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.27.5.523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saylor CF, Finch AJ, Spririto A, Bennett B. The children’s depression inventory: A systematic evaluation of psychometric properties. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1984;52:955–967. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.52.6.955. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seligman MEP, Peterson C, Kaslow NJ, Tannenbaum RL, Alloy LB, Abramson LY. Attributional style and depressive symptoms among children. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1984;83:235–238. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.93.2.235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siegler RS. Emerging minds: The process of change in children’s thinking. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Smucker MR, Craighead WE, Craighead LW, Green BJ. Normative and reliability data for the Children’s Depression Inventory. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 1986;14:25–39. doi: 10.1007/BF00917219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spitzer RL, Williams JB, Gibbon M, First MB. The structured clinical interview for DSM-III-R (SCID). I: history, rationale, and description. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1992;49:624–629. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1992.01820080032005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tangney JP. Conceptual and methodological issues in the assessment of shame and guilt. Behavior Research and Therapy. 1996;34:741–754. doi: 10.1016/0005-7967(96)00034-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tangney JP, Wagner PE, Gramzow R, Fletcher C. The Test of Self-Conscious Affect for Children (TOSCA-C) Fairfax, VA: 1990. Unpublished manuscript. [Google Scholar]

- Tangney JP, Wagner PE, Gavlas J, Gramzow R. The test of self-conscious affect for adolescents (TOSCA-A) Fairfax: George Mason University; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Tangney JP, Wagner PE, Gramzow R. Proneness to shame, proneness to guilt, and psychopathology. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1992;101(3):469–478. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.101.3.469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tangney JP, Wagner PE, Hill-Barlow D, Marschall DE, Gramzow R. Relation of shame and guilt to constructive versus destructive responses to anger across the lifespan. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1996;70:797–809. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.70.4.797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tangney JP, Dearing RL, Wagner PE, Gramzow R. The Test of self-conscious afffec-3 (TOSCA-3) Fairfax, VA: George Mason University; 2000. Unpublished manuscript. [Google Scholar]

- Tilghman-Osborne C, Cole DA, Felton JW, Ciesla JA. Relation of guilt, shame, behavioral and characterological self-blame to depressive symptoms in adolescents over time. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology. 2008;27:809–842. doi: 10.1521/jscp.2008.27.8.809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tilghman-Osborne C, Cole DA, Felton JW. Definition and measurement of guilt: Implications for clinical research practice. Clinical Psychology Review. 2010;30:536–546. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2010.03.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tilgner L, Wertheim EH, Paxton SJ. The effect of social desirability on adolescent girls’ responses to an eating disorders prevention program. International Journal of Eating Disorders. 2004;35:211–216. doi: 10.1002/eat.10239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weems CF, Berman SL, Silverman WK, Saavedra LM. Cognitive errors in youth with anxiety disorders: The linkages between negative cognitive errors and anxious symptoms. Cognitive Therapy and Research. 2001;25:559–575. [Google Scholar]

- Weisz JR, Chorpita BF. “Mod Squad” for youth psychotherapy: restructuring evidence-based treatment for clinical practice. In: Kendall PC, editor. Child and adolescent therapy, fourth edition: Cognitive-behavioral procedures. New York: The Guilford Press; 2011. pp. 379–397. [Google Scholar]

- Williams C, Bybee J. What do children feel guilty about? Development and gender differences. Developmental Psychology. 1994;30:617–623. [Google Scholar]

- Worchel FF, Hughes JN, Hall BM, Stanton SB. Evaluation of subclinical depression in children using self-, peer-, and teacher-reported measures. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 1990;18:271–282. doi: 10.1007/BF00916565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zahn-Waxler C, Kochanska G, Krupnick J, McKnew D. Patterns of guilt in children of depressed and well mothers. Developmental Psychology. 1990;26:51–59. [Google Scholar]