Abstract

Syk is a cytoplasmic protein-tyrosine kinase well known for its ability to couple immune cell receptors to intracellular signaling pathways that regulate cellular responses to extracellular antigens and antigen-immunoglobulin complexes of particular importance to the initiation of inflammatory responses. Thus, Syk is an attractive target for therapeutic kinase inhibitors designed to ameliorate symptoms and consequences of acute and chronic inflammation. Its more recently recognized role as a promoter of cell survival in numerous cancer cell types ranging from leukemia to retinoblastoma has attracted considerable interest as a target for a new generation of anticancer drugs. This review discusses the biological processes in which Syk participates that have made this kinase such a compelling drug target.

Keywords: protein kinase inhibitor, tyrosine-phosphorylation, fostamatinib, allergic asthma, rheumatoid arthritis, leukemia

Spleen tyrosine kinase

The central role played by Syk (spleen tyrosine kinase) in the immune system in mediating inflammatory responses, coupled with its more recently identified association with malignancy, has made this kinase a popular target for the development of therapeutic agents. A search of the patent literature reveals over 70 filings describing the development of small molecular inhibitors of Syk for the treatment of multiple disease states ranging from arthritis and asthma to leukemia and lymphoma.

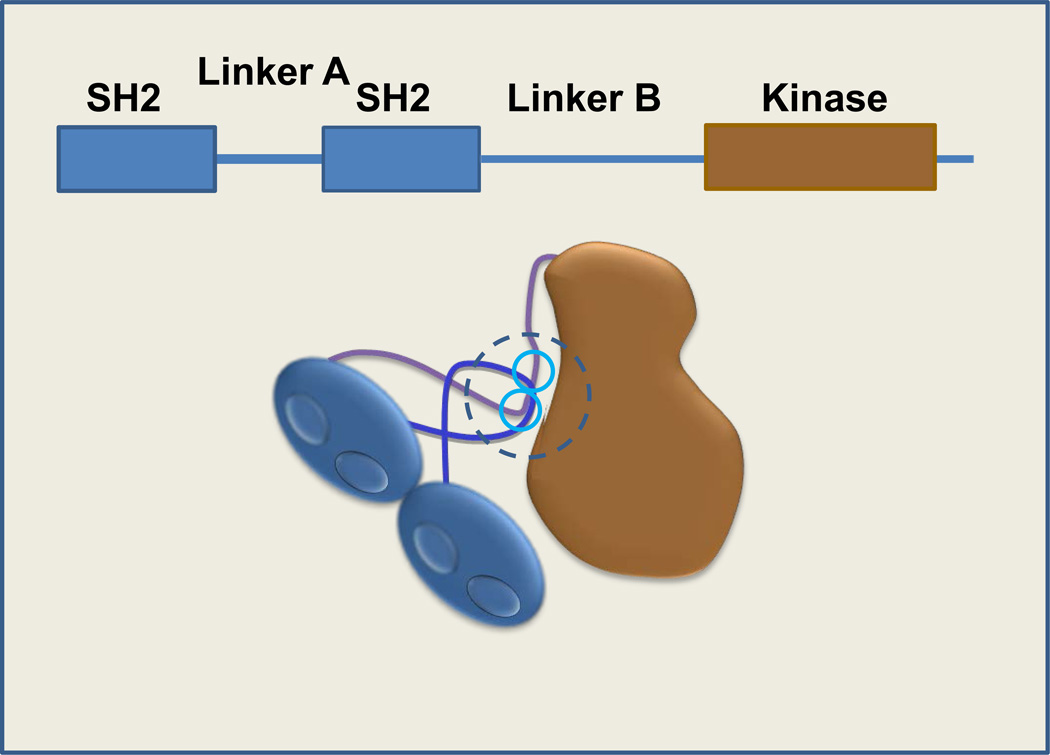

Syk catalyzes the phosphorylation of proteins on tyrosines located at sites rich with acidic amino acids [1]. Interestingly, at least two substrates, CD79a [2] and the Ikaros transcription factor [3], have been reported to be phosphorylated by Syk on serine, suggesting that Syk may access a wider distribution of substrates than originally thought. The Syk protein comprises a pair of Src homology 2 (SH2) domains at the N-terminus that are joined to each other by linker A and are separated by a longer linker B from the catalytic domain [4, 5] (Figure 1). Aromatic amino acids in linker A, linker B, the catalytic domain and the extreme C-terminus participate in the formation of a “linker-kinase sandwich” (as first identified in the Syk-family member, Zap-70 [6]) that maintains the enzyme in an autoinhibited conformation [7]. Activation of Syk occurs when the tandem SH2 domains are engaged or when tyrosines participating in the linker-kinase sandwich become phosphorylated.

Figure 1.

Domain organization of Syk. Syk contains an N-terminal, tandem pair of SH2 domains connected by linker A and separated by a linker B region from the catalytic (kinase) domain. Aromatic residues present in linker A, linker B (tyrosines 348 and 352; blue circles), and the catalytic domain interact to form a “linker-kinase sandwich” (dotted circle) that stabilizes the inactive form of the kinase.

SH2 domains are structural motifs that bind phosphotyrosine to promote protein-protein interactions [8]. Each of the SH2 domains of Syk binds proteins containing the sequence pYXXL/I, where pY is phosphotyrosine and X denotes any amino acid. These SH2 domains are juxtaposed in an orientation that allows them to engage simultaneously a linear sequence that contains two of these pYXXL/I cassettes separated by 6-10 amino acids [9]. These high affinity Syk-binding sites are known as immunoreceptor tyrosine-based activation motifs or ITAMs as they are present in many receptors that are important in immune cells [10]. In general, these receptors oligomerize upon engagement by ligand. This is followed by phosphorylation of the two ITAM tyrosines in a reaction that is initiated by a member of the Src-family of tyrosine kinases [4, 5]. Syk physically docks to the doubly phosphorylated ITAM via its tandem SH2 domains in a head-to-tail orientation. Conformational changes disrupt the “linker-kinase sandwich” and activate the enzyme [7]. Syk is then rapidly phosphorylated on tyrosines located in linkers A and B, the activation loop of the catalytic domain, and the extreme C-terminus through both autophosphorylation and phosphorylation in trans by Src-family kinases [4, 5]. These phosphotyrosines serve a variety of purposes including maintenance of the activated state, promotion of signaling complex formation, and release of kinase from the receptor [4, 5]. Signals are further transmitted from the Syk-receptor complex through the phosphorylation of adapter proteins such as BLNK/SLP-65, SLP-76, and LAT [5, 11] (Figure 2). When phosphorylated, these proteins serve as scaffolds to which effectors dock with SH2 or other related phosphotyrosine-binding motifs. Effectors include members of the Tec-family of tyrosine kinases, lipid kinases, phospholipases, and guanine nucleotide exchange factors that further propagate the signal allowing for the activation of multiple pathways including PI3K/Akt, Ras/ERK, PLCγ/NFAT, Vav-1/Rac and IKK/NFκB [4, 5].

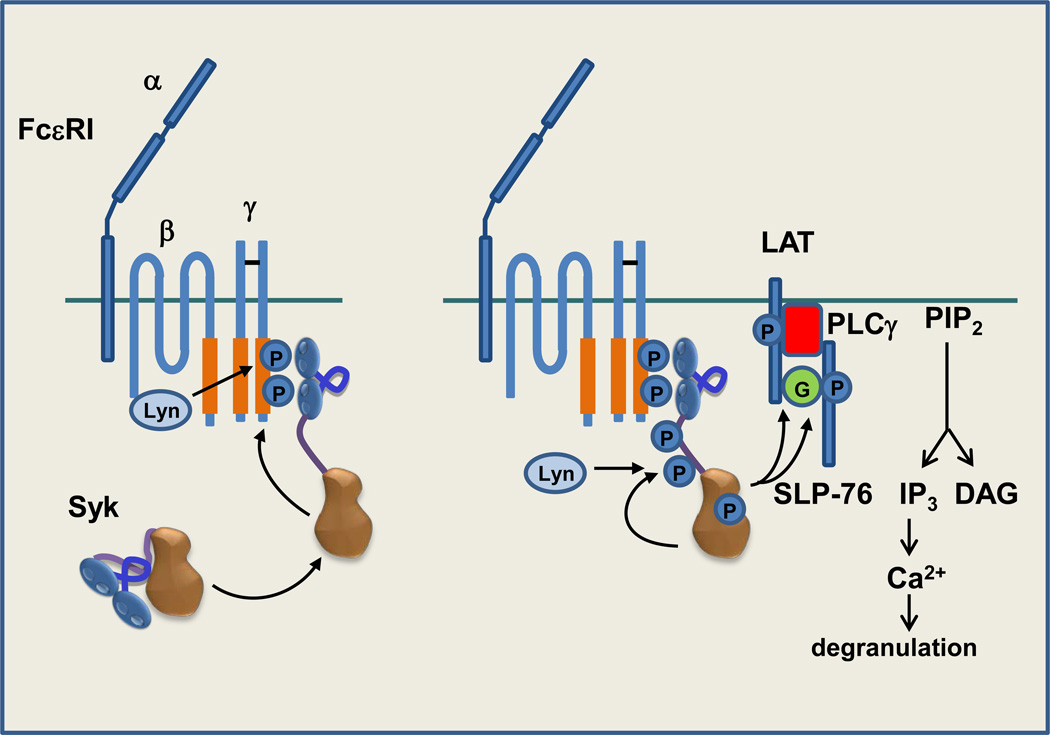

Figure 2.

Syk couples FcεRI, the high affinity receptor for IgE, to degranulation in mast cells. Following aggregation of FcεRI by IgE-antigen complexes (not pictured), Lyn initiates the phosphorylation of ITAM tyrosines leading to the recruitment of Syk to the receptor in an interaction mediated by its tandem pair of SH2 domains. Syk becomes phosphorylated in trans by Lyn and by other Syk molecules recruited to the clustered receptor. Active Syk phosphorylates adaptor proteins LAT and then SLP-76, recruited to LAT via GADS (G), to generate binding sites for PLCγ and Btk (not pictured). The phosphorylation of PLCγ by Btk and Syk leads to its activation and the hydrolysis of phosphoinositide 4,5-bisphosphate (PIP2) to generate the second messengers diacylglycerol (DAG) and inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate (IP3). The binding of IP3 to IP3 receptors on the ER triggers the release of calcium from intracellular stores leading to the entry of extracellular calcium to trigger the release of inflammatory mediators stored in intracellular granules.

It is the nature and function of the receptors in the immune system with which Syk interacts that make it a compelling drug target. Notably, Syk often associates with receptors that bind substances that are foreign to the body (e.g., pathogens or allergens) or that bind antigen- immunoglobulin complexes [5, 10, 12]. Thus, these receptors are prominent among those responsible for discriminating between self and non-self, the sine qua non of the immune system. Unfortunately, when these receptors inappropriately recognize self antigens or harmless environmental antigens, damaging hypersensitivity reactions can result leading to tissue damage and disease.

High affinity receptor for immunoglobulin E (IgE)

Type I hypersensitivity reactions occur when environmental antigens bind to IgE to activate mast cells and basophils to release inflammatory mediators [13]. IgE is produced when dendritic cells that have encountered allergens present peptides on MHC class II molecules to activate naïve CD4+ T cells. These helper T cells support the proliferation of allergen-recognizing B cells and secrete cytokines that promote class switching, resulting in the production of IgE. The Fc region of IgE is bound directly by the α-chain of the mast cell receptor FcεRI with high affinity (Kd = 0.1 nM) via an interaction characterized by an exceptionally slow off-rate driven by conformational changes in the bound immunoglobulin [14]. Consequently, IgE is pre-bound to receptors even in the absence of cognate antigen. Mast cells even extend processes into the vasculature to “fish” for circulating IgE [15]. The binding of allergen to the preformed IgE-FcεRI complex clusters the receptor, initiating the phosphorylation by Lyn of ITAM tyrosines in the cytoplasmic tails of the β- and γ-chains of the FcεRI complex. This results in the recruitment and activation of Syk [16]. Syk phosphorylates adaptors including LAT and SLP-76 to recruit both Btk and phospholipase C-γ leading to calcium mobilization and the immediate release of pre-packaged inflammatory mediators (Figure 2). Syk-dependent activation of PKC and the Erk pathway activates phospholipase A2 to initiate the biosynthesis of leukotrienes and prostaglandins. The activation of nuclear factor of activated T cells (NFAT) and NF-κB promotes the expression of a wide array of cytokines and chemokines that precipitate the late phases of an immediate hypersensitivity reaction.

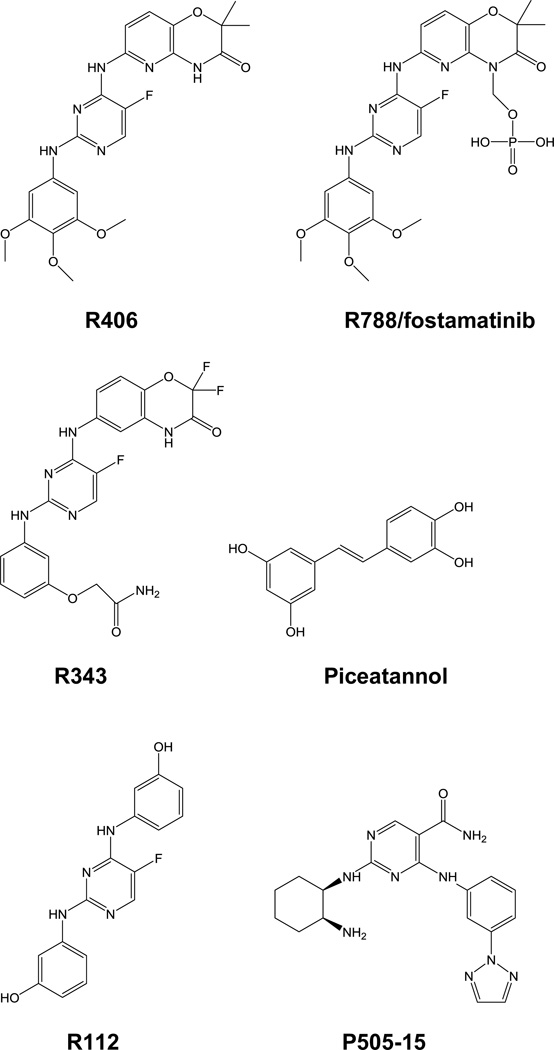

Syk is essential for FcεRI-triggered mast cell activation. Syk-deficient mast cells generated from Syk-knockout mice fail to degranulate in response to FcεRI engagement [17]; and signaling can be restored by the re-expression of Syk [18]. Similarly, mast cells from mice in which a floxed Syk gene has been inducibly excised fail to respond to FcεRI clustering as measured by calcium flux or secretion of histamine [19]. Thus, Syk is an attractive target for therapeutic intervention in mast cell-mediated inflammatory diseases. The disease of most interest to the pharmaceutical industry has been allergic asthma. Mast cells are present at elevated levels in the airway epithelia of asthmatic patients [20, 21] and their activation in bronchopulmonary tissues underlies much of the pathology of allergic asthma [20–22]. Several approaches have been conceived for the generation of drugs that target Syk [23, 24]. These fall into two general categories: small molecule inhibitors of catalytic activity and oligonucleotide-based inhibitors of protein expression. Most small molecule Syk inhibitors, with the exception of the substrate-site inhibitor piceatannol, target the ATP-binding site; several have proven efficacious in blocking inflammation in mouse models of asthma [25–27]. Similarly, inhibitors based on both antisense oligonucleotides and small interfering RNAs (siRNAs) designed to inhibit Syk expression have proven effective in animal models of ovalbumin-induced asthma [28, 29]. For both classes of inhibitors, investigators have explored directed delivery to the lung to avoid side effects associated with systemic drug delivery. The most well developed drug candidate, R343 (Figure 3), although promising in Phase I clinical trials, did not achieve expected endpoints in a recent Phase II trial. However, the exploration of Syk inhibitors for the treatment of asthma is still in its infancy and other inhibitors are in the early stages of clinical trials. Indeed, there are many conditions associated with mast cell-mediated inflammation that could benefit from the use of therapeutic Syk inhibitors. In a particularly interesting example, the intranasal delivery of the Syk inhibitor R112 (Figure 3) provided rapid relief from allergic rhinitis in human volunteers exposed to environmental allergens [30].

Figure 3.

Examples of Syk kinase inhibitors. R788/fostamatinib is the produrg form of R406 and is the best characterized of the Syk inhibitors in patient studies. R343 is an inhaled Syk inhibitor designed for the treatment of allergic asthma and R112 an intranasal inhibitor tested for the alleviation of seasonal allergies. P505-15 is an orally available, highly selective Syk inhibitor. R788, R406, R343 and R112 were developed by Rigel Pharmaceuticals and P505-15 by Portola Pharmaceuticals. All are ATP-binding site inhibitors. Piceatannol, a natural stilbene, is a relatively low affinity inhibitor of Syk, but one that binds competitively with the phosphoacceptor substrate.

Receptors for IgG and arthritis

Type II and type III hypersensitivity reactions are mediated by IgG that interacts with bound or soluble antigens, respectively, and are responsible for the inflammation that accompanies many autoimmune diseases. IgG-antigen complexes are recognized by Fcγ receptors on cells of the innate immune system. Three of these, FcγRI, FcγRIIA and FcγRIIIA, are coupled to the activation of Syk through ITAMs present either as part of the Fc-binding component itself (FcγRIIA) or found on the accessory protein FcRγ (FcγRI, FcγRIIIA) [31]. Receptor engagement triggers the phagocytosis of IgG-opsonized particles and the generation of nitric oxide and reactive oxygen species, which is useful for the killing of microbes but can cause unnecessary tissue damage when triggered by environmental or self-antigens. Syk-deficient macrophages fail to phagocytose IgG-coated particles and neutrophils from Syk-deficient mice fail to undergo an oxidative burst in response to the engagement of FcγRs [32, 33]. The oxidative burst of neutrophils is largely adhesion dependent due to an additional requirement for integrins, heterodimeric receptors that mediate the adhesion of cells to extracellular matrix proteins. In neutrophils, integrins signal through an association with either FcγR or DAP12, another ITAM-containing accessory protein; and Syk is required for adhesion-dependent activation [34]. This makes Syk an attractive target for anti-inflammatory therapeutics.

IgGs that form complexes with self-antigens are important contributors to the pathology of rheumatoid arthritis (RA) [35], a major disease target of therapeutic Syk inhibitors. Immune complexes become deposited in joints and activate macrophages and neutrophils through Fcγ receptors. The resulting production of reactive oxygen species and the secretion of pro- inflammatory cytokines promote severe joint damage. Engineered mice that lack FcRγ or FcγRIII fail to develop arthritis induced by immunization with collagen [36]. Similarly, the transfer of serum from K/BxN mice, which induces arthritis in recipient mice with wild-type immune systems, fails to do so in mice with reconstituted immune systems that lack Syk [37]. In this model, the elimination of Syk from neutrophils alone is sufficient to block joint inflammation [38]. The direct injection of naked Syk siRNA into joints ameliorates swelling and inflammation in a mouse model of arthritis [29], supporting a direct role for Syk inhibition in alleviating RA pathology.

Strategies for the inhibition of Syk in RA patients by small molecules are similar to those for the treatment of asthma although the route of administration is necessarily different. Consequently, considerable effort has been focused on the development of orally available, small molecule, ATP-competitive inhibitors [39]. Of these, the most extensively explored is fostamatinib (R788), a more soluble pro-drug form of the Syk inhibitor R406 (Figure 3). The administration of fostamatinib to whole animals blocks the IgG-mediated Arthus reaction and inhibits collagen-antibody induced arthritis (CIA) [40, 41]. Additional Syk inhibitors also have shown encouraging activity in animal models of RA [42–44]. Fostamatinib has exhibited a promising ability to decrease joint inflammation in Phase II clinical trials in human patients [45–47], however, phase III trials were reportedly disappointing. Clearly, results using other, perhaps more highly selective, Syk inhibitors are anxiously awaited.

As a side-benefit, Syk inhibitors also have the potential to ameliorate other RA-associated pathologies. Osteoclasts, which cause bone damage in patients with RA, are activated through the binding of receptor activator of NF-κB ligand (RANKL) to its receptor RANK. RANK signaling is attenuated by the downregulation of FcRγ and DAP12, RANKL-mediated osteoclast activation is Syk-dependent [48], and Syk inhibitors reduce bone damage in mouse models of RA [41]. The TNFα-induced activation of synoviocytes, which secrete inflammatory cytokines and degradative enzymes that can cause matrix destruction in patients with RA, also is Syk- dependent [49]. Finally, much of the morbidity associated with RA is due to an increased risk of heart failure secondary to atherosclerosis, an inflammatory disease of the vasculature. Damaged endothelial cells attract multiple immune cell types including macrophages, mast cells and platelets that combine to generate atherosclerotic lesions that contain elevated levels of activated Syk and to which are recruited neutrophils. Syk is required for the recruitment of monoctyes and macrophages to endothelial cells expressing fractalkine (CX3CL1) in response to inflammatory cytokines [50]. Syk also mediates integrin-dependent, slow neutrophil rolling and adherence to inflamed endothelial cells expressing L- or P-selectin. The cytoplasmic tail of L-selectin is associated with P-selectin glycoprotein ligand (PSGL-1) and is coupled to the ITAM-containing proteins DAP12 and FcRγ [51]. In mice deficient in the low density lipoprotein receptor, a high cholesterol diet results in the formation of atherosclerotic plaques containing high levels of activated macrophages. The administration of fostamatinib impairs the migration of inflammatory cells into these plaques and also inhibits M-CSF-induced macrophage differentiation [52].

Other IgG-mediated immune disorders

Other examples of autoimmune diseases based on type I or type II hypersensitivity reactions for which an inhibitor of Syk might prove useful are under active investigation. Systemic lupus erythrematosus (SLE) is characterized by B and T cells that are hyperresponsive to the engagement of antigen receptors, leading to the production of auto-reactive antibodies that form immune complexes that can trigger type III hypersensitivity reactions that damage joints, blood vessels and renal glomeruli [53, 54]. The B cells that produce IgG are activated through the B cell receptor for antigen (BCR), which consists of a membrane spanning immunoglobulin in association with two signaling adaptors: CD79a (Ig-α) and CD79b (Ig-β), each of which contains a single ITAM [4, 5]. B cells fail to develop in Syk-deficient immune systems due to an absence of signaling by either pre-B cell receptors or surface IgM on immature B cells resulting in a total loss of the mature B cell population [55]. Similarly, disruption of the Syk gene in DT40 B cells blocks essentially all BCR-stimulated signaling pathways [56]. Thus, B cell activation can be readily blocked by Syk inhibitors. In some patients, B cell hyperactivity is associated with decreased levels of Lyn [57]. Although Lyn is an initiating kinase for BCR signaling, it has a net negative effect on B cell activation mediated by the phosphorylation on tyrosine of inhibitory motifs (ITIMs) on FcγRIIB and CD22, which recruits the SHP-1 and SHIP-1 phosphoprotein and lipid phosphatases. Thus, the selective deletion of Lyn from B cells in mice produces a lupus-like disease [58]. The T cell receptor for antigen (TCR) in mature T cells is associated with the CD3 complex and a dimer of ζ chains, each of which contains three ITAMs [59]. Following receptor engagement, the phosphorylation of ζ chain ITAM tyrosines by Lck leads to the binding of Zap-70 in much the same way that Syk is recruited to phosphorylated ITAMs in B cells or mast cells. Interestingly, in lupus patients, the T cell repertoire is altered such that many cells lack ζ chains, have low levels of Lck, and express Syk, which is not normally found in mature T cells [54]. TCRs in these SLE T cells now signal via the phosphorylation of FcRγ, which replaces the lost ζ chains, and recruits Syk in place of Zap-70. Much of the altered gene expression that characterizes SLE T cells (e.g., increased expression of IL-21, CD44, PP2A and OAS2) can be induced by the overexpression of Syk in normal T cells [60], suggesting that the inappropriate activation of Syk is directly responsible for much of their hyperactive phenotype. Consistent with this hypothesis, Syk inhibitors block TCR-dependent mobilization of calcium in SLE T cells in vitro and fostamatinib inhibits disease progression in murine models of lupus [60–63].

Similarly, inhibitors of Syk are under investigation for the treatment of chronic immune thrombocytopenic purpura (ITP) and heparin-induced thrombocytopenia (HIT), two autoimmune diseases in which self-reactive antibodies are generated against antigens on platelets, resulting in platelet activation and the opsonization and phagocytosis of both platelets and megakaryocytes by macrophages. Syk inhibitors block both immune complex mediated platelet activation through FcγRIIA, and the resulting thrombocytopenia in a mouse model of HIT [64]. Similarly, fostamatinib blocks platelet loss induced by an antibody against integrin αIIβ in a mouse model of ITP [65]. A Phase II clinical trial in human patients showed that fostamatinib successfully restored platelets to approximately 50% of patients with ITP [65].

Type I Diabetes

Immune complexes comprising IgG bound to antigen are internalized by professional antigen presenting cells through Fcγ receptors allowing the presentation of antigen-derived peptides to naïve T cells including CD8 cells in a Syk-dependent process [66]. Thus, in type I diabetes, autoantibodies produced by B cells can facilitate the generation of self-reactive cytotoxic T cells. Deletion of the Syk gene selectively in dendritic cells blocks this generation of diabetogenic T cells [67]. Similarly, in mouse models of type I diabetes, fostamatinib blocks MHC class II- restricted presentation by antigen-specific B cells, the priming of cytotoxic T cells and the onset of diabetes [67]. Thus, Syk inhibitors also have considerable potential for the treatment of autoimmune diseases generally assumed to be mediated predominantly by T cells.

Ischemia-reperfusion injury

The presence of Syk in so many cells that play important roles in inflammatory responses to vascular damage has prompted investigations into the use of kinase inhibitors to treat ischemia- reperfusion injury, which occurs when a blood supply is returned to cells following oxygen and nutrient deprivation [68]. Fostamatinib reduces both intestinal and lung damage in a mesenteric ischemia-reperfusion model [69], potentially by inhibiting FcγR and complement-mediated signaling [70]. Similarly, piceatannol reduces neuronal damage in a mouse model of retinal ischemia-reperfusion injury attributed to the activation of toll-like receptor 4 (TLR4) [71, 72], a receptor with which Syk interacts directly in an unconventional, potentially phosphotyrosine- independent, fashion [73, 73].

Syk and cancer

Several recent studies have indicated an important, albeit enigmatic, role for Syk in tumor cell biology. Syk was first described as a tumor suppressor based on its absence from highly invasive breast carcinomas and its presence in less malignant cells [74, 75]. The ectopic expression of Syk in highly invasive carcinomas inhibits their motility and ability to form metastases [74]. A progressive loss of Syk mRNA is seen in patient samples as cells advance from normal through hyperplastic to ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS) and then on to infiltrating ductal carcinoma (IDC) [76]. Loss of Syk from breast cancer cells has been attributed to promoter methylation [77] or to allelic loss as recently observed in patient samples of IDC and DCIS [78]. Although the level of Syk expression alone is not prognostic for breast cancer survival, a signature set of Syk “interacting” genes effectively predicts patient outcomes [78]. Similarly, Syk is found in melanocytes, but is frequently absent from melanoma cell lines and tumors due to promoter methylation; and its re-expression induces senescence [79]. Decreases in Syk levels have been reported also in hepatocellular carcinoma at the level of both gene and protein expression [80, 81]. Syk also has reported tumor suppressor activity in pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma [82].

Of greater interest to drug developers, however, is the increasingly large number of examples in which Syk functions as a pro-survival factor in cancers of both hematopoietic and epithelial origins. Subsets of chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL), acute lymphoblastic leukemia, non- Hodgkin lymphoma and EBV-associated B cell lymphomas express active Syk, the knockdown or inhibition of which leads to apoptosis [83–88]. The general view is that Syk plays its pro- survival role in B cell cancers due to tonic signaling through the BCR [89]. This mechanism may parallel the role of Syk during normal B cell development, where its expression is required for cells to survive the pro- to pre-B and immature to mature B cell transitions, steps that require functional BCRs [90]. However, the repertoire of cells in which Syk functions as a pro-survival factor extends to hematological malignancies not of B cell origin (acute myeloid leukemia (AML) and a variety of T-cell lymphomas [91, 92]) in which it is likely that other ITAM- containing receptors other than the BCR are coupled to the activation of Syk. For example, in AML, a β3-integrin was identified as an essential gene for leukemia growth whose function is dependent on its downstream target, Syk [93]. Encouragingly, a Phase I/II clinical trial of fostamatinib revealed positive responses for patients with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma, follicular lymphoma, mantle cell lymphoma and small lymphocytic leukemia/chronic lymphocytic leukemia [94]. Cells from CLL patients undergoing treatment exhibited decreased expression of BCR target genes and decreased phosphorylation of Btk, a tyrosine kinase activated downstream of Syk [95].

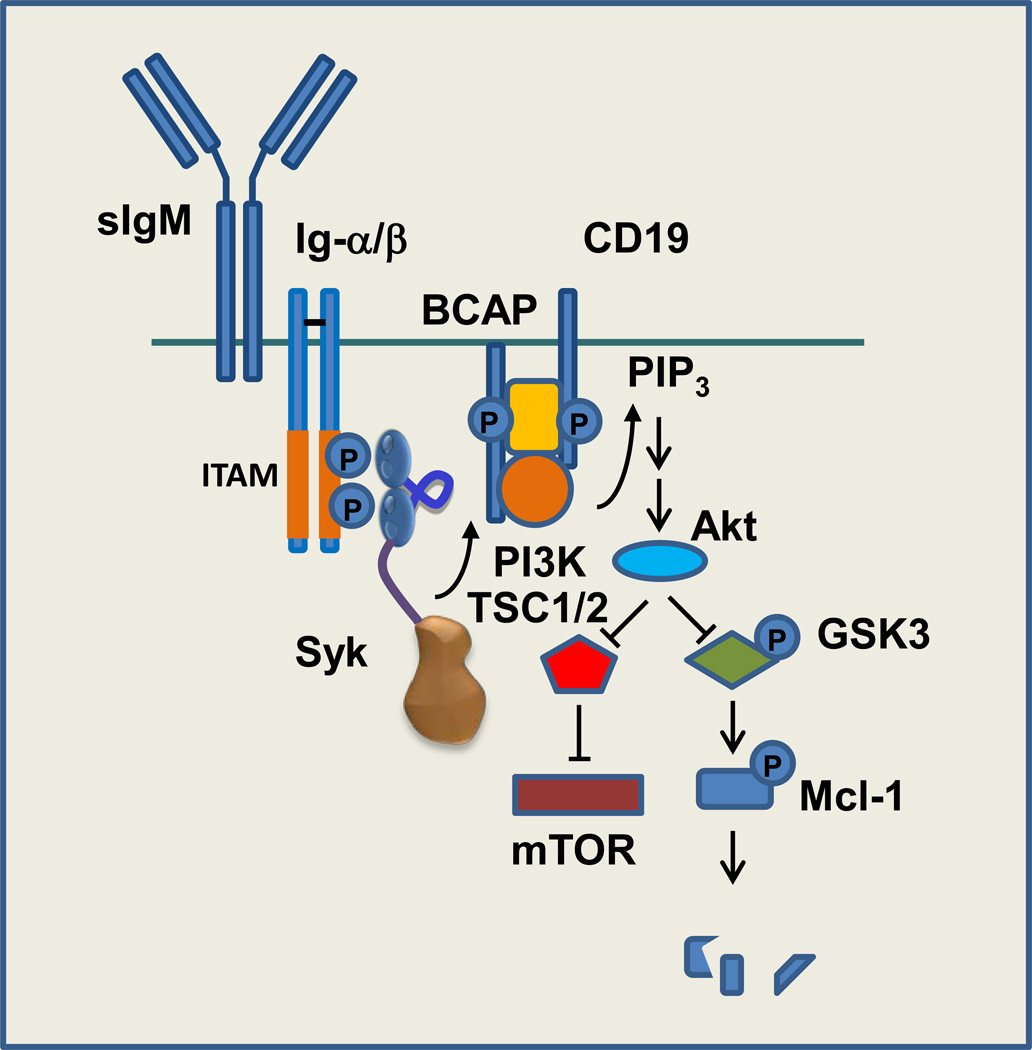

Interestingly, Syk also is a pro-survival factor for some malignancies of epithelial origin where signaling through receptors with ITAMs is more poorly understood. As examples, the expression of Syk distinguishes K-Ras "addicted" lung and pancreatic carcinomas from those not dependent on activated K-Ras for viability [96]. K-Ras addicted cells undergo apoptosis in response to Syk inhibition or knockdown. The expression of Syk is induced by epigenetic mechanisms in retinoblastoma and these cells also undergo apoptosis if the level or activity of the kinase is reduced [97]. The transformation of breast epithelial cells by MMTV requires Syk; but in this case an ITAM is furnished by the MMTV Env protein [98]. Regulation of the alternative splicing of SYK transcripts by EGF promotes expression of the long form of the kinase, which supports the survival of breast and ovarian cancer cells [99]. The downstream signaling events modulated by the presence of a tonically activated Syk are still under investigation, but activation of the PI3K/Akt pathway is a likely contributor (Figure 4). In B cell lymphomas and AML, the activation of mTOR, which lies downstream of Akt, is correlated with the presence of activated Syk [100, 101]. In both retinoblastoma and B-CLL, the level of the anti-apoptotic protein, Mcl-1, is elevated in Syk-expressing cells due to activation of PKCδ and the PI3K/Akt pathway [85, 97, 102]. Active Akt negatively regulates GSK3 to block the phosphorylation of Mcl-1, an event that triggers its ubiquitination and proteosomal degradation [103]. In diffuse large B cell lymphoma (DLBCL), Syk and Akt also repress the expression of the pro-apoptotic protein HRK and upregulate cholesterol biosynthesis, which promotes BCR signaling in lipid rafts [104]. Syk also enhances signaling through the FLT-3 receptor tyrosine kinase in AML cells, many of which express mutant, dominantly active forms of FLT-3 [105].

Figure 4.

Syk couples the BCR to the activation of mTOR and stabilization of the antiapoptotic protein Mcl-1. Binding of antigen to the surface IgM (sIgM) component of the BCR complex leads to the phosphorylation of ITAM tyrosines on the cytoplasmic tails of Igα (CD79a) and Igβ (CD79b) and the recruitment of Syk. Activated phosphorylates adaptor proteins such as CD19 and BCAP to create docking sites for the SH2 domain of the p85 subunit of phosphoinositide 3-kinase (PI3K), which is associated with the p110 catalytic subunit. PI3K catalyzes the formation within the plasma membrane of phosphoinositide 3,4,5-trisphosphate (PIP3), a ligand for the plexkstrin homology (PH) domain of Akt. Activated Akt catalyzes the phosphorylation of and inhibition of the tuberous sclerosis complex, a negative regulator of mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR). Akt also phosphorylates and inhibits glycogen synthase kinase 3 (GSK3), blocking the phosphorylation of Mcl-1 and thus enhancing its stability.

Concluding remarks

No Syk inhibitors are currently approved for therapeutic use and recent clinical failures have dampened enthusiasm for the targeting of Syk, at least for the treatment of inflammatory diseases. However, it is not yet clear if treatment failures were a consequence of the target selected (i.e., Syk) or instead derived from a lack of potency or selectivity of the inhibitors that were tested. An analysis of kinase inhibitor selectivity based on competitive binding at the ATP site of a library of kinases indicated that R406, the active metabolite of the most thoroughly tested inhibitor, fostamatinib, was highly promiscuous, binding at a concentration of 3 µM to over 60% of the kinases in the screen (and binding more tightly many kinases than to its intended target) [106]. Consequently, many recent patent filings have focused on the identification of inhibitors with both increased potency and increased selectivity. The true value of Syk as a target for immune disorders will need to wait for further testing of these more potent and specific inhibitors. Other new approaches under development include the design of inhibitors that target simultaneously two kinases (e.g., small molecules capable of inhibiting both Syk and JAK are under investigation for the treatment of hematological malignancies and inflammatory diseases such as chronic dry eye) and the use of Syk inhibitors in combination with other therapeutic agents. In is known, for example, that tumors induced in mice by the expression of active FLT-3 are much more sensitive to a combination of FLT-3 and Syk inhibitors than to either alone [105]. Synergistic growth inhibition also is observed in CLL cells upon treatment with a combination of PI3K and Syk inhibitors [107]). Finally, Syk inhibitor P505-15 attenuates the growth of non- Hodgkin lymphoma and CLL in mouse xenograft models in a manner that is synergistic with fludarabine, a purine nucleoside analog [108]. Finally, it will be important to sort out the mechanisms that govern the apparent dichotomous role of Syk in tumorigenesis where it acts in some cells as a tumor promoter and in others as a tumor suppressor to determine if prolonged administration of Syk inhibitors to patients with chronic inflammatory diseases will ameliorate or exacerbate the metastatic behavior of primary malignancies.

Highlights.

Syk couples many immune recognition receptors to inflammatory responses

Syk is a pro-survival factor for several hematological and non-hematological cancers

Small molecule inhibitors of Syk are under development to treat both immune disorders and cancer

Acknowledgements

R.L.G is supported in part by National Institutes of Health (NIH) grant R01AI098132-31.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Xue L, et al. Identification of direct kinase substrates based on protein kinase assay linked phosphoproteomics. Mol. Cell. Proteomics. 2013;12:2969–2980. doi: 10.1074/mcp.O113.027722. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Heizmann B, et al. Syk is a dual-specificity kinase that self-regulates the signal output from the B-cell antigen receptor. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2010;107:18563–18568. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1009048107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Uckun FM, et al. Serine phosphorylation by SYK is critical for nuclear localization and transcription factor function of Ikaros. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2012;109:18072–18077. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1209828109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Geahlen RL. Syk and pTyr’d: Signaling through the B cell antigen receptor. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2009;1793:1115–1127. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2009.03.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mócsai A, et al. The SYK tyrosine kinase: a crucial player in diverse biological functions. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2010;10:387–402. doi: 10.1038/nri2765. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Deindl S, et al. Structural basis for the inhibition of tyrosine kinase activity of ZAP-70. Cell. 2007;129:735–746. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.03.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Grädler U, et al. Structural and biophysical characterization of the Syk activation switch. J. Mol. Biol. 2013;425:309–333. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2012.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Liu BA, et al. The human and mouse complement of SH2 domain proteins establishing the boundaries of phosphotyrosine signaling. Mol. Cell. 2006;22:851–868. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2006.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fütterer K, et al. Structural basis for Syk tyrosine kinase ubiquity in signal transduction pathways revealed by the crystal structure of its regulatory SH2 domains bound to a dually phosphorylated ITAM peptide. J. Mol. Biol. 1998;281:523–537. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1998.1964. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Abram CL, Lowell CA. The expanding role for ITAM-based signaling pathways in immune cells. Science’s STKE : Signal Transduction Knowledge Environment. 2007 doi: 10.1126/stke.3772007re2. re2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yablonski D, Weiss A. Mechanisms of signaling by the hematopoietic-specific adaptor proteins, SLP-76 and LAT and their B cell counterpart, BLNK/SLP-65. Adv. Immunol. 2001;79:93–128. doi: 10.1016/s0065-2776(01)79003-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ivashkiv LB. Cross-regulation of signaling by ITAM-associated receptors. Nat. Immunol. 2009;10:340–347. doi: 10.1038/ni.1706. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gould HJ, Sutton BJ. IgE in allergy and asthma today. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2008;8:205–217. doi: 10.1038/nri2273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Holdon MD, et al. Conformational changes in IgE contribute to its uniquely slow dissociation rate from receptor FCεRI. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2011;18:571–576. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.2044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cheng LE, et al. Perivascular mast cells dynamically probe cutaneous blood vessels to capture immunoglobulin E. Immunity. 2013;38:166–175. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2012.09.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gilfillan AM, Rivera J. The tyrosine kinase network regulating mast cell activation. Immunol. Rev. 2009;228:149–169. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065X.2008.00742.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Costello PS, et al. Critical role for the tyrosine kinase Syk in signaling through the high affinity IgE receptor of mast cells. Oncogene. 1996;13:2595–2605. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Simon M, et al. Distinct roles for the linker region tyrosines of Sky in FcεRI signaling in primary mast cells. J. Biol. Chem. 2004;280:4510–4517. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M410326200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wex E, et al. Induced Syk deletion leads to suppressed allergic responses but has no effect on neutrophil or monocyte migration in vivo. Eur. J. Immunol. 2011;41:3208–3218. doi: 10.1002/eji.201141502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Barnes PJ. Immunology of a sthma and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2008;8:183–192. doi: 10.1038/nri2254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cohn L, et al. Asthma: mechanisms of disease persistence and progression. Ann. Rev. Immunol. 2004;22:789–815. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.22.012703.104716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wu LC. Immunoglobulin E receptor signaling and asthma. J. Biol. Chem. 2011;286:32891–32897. doi: 10.1074/jbc.R110.205104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kaur M, et al. Inhibitors of switch kinase “spleen tyrosine kinase” in inflammation and immune-mediated disorders: a review. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2013;67:434–446. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmech.2013.04.070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wong WSF, Leong KP. Tyrosine kinase inhibitors: a new approach for asthma. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2004;1697:53–69. doi: 10.1016/j.bbapap.2003.11.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Penton PC, et al. Spleen tyrosine kinase inhibition attenuates airway hyperresponsiveness and pollution-induced enhanced airway response in a chronic mouse model of asthma. J. Allergy Clin. Immun. 2013;131:512–520. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2012.07.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yamamoto N, et al. The orally available spleen tyrosine kinase inhibitor 2-[7-(3,4-dimethoxyphenyl)-imidazo[1,2-c]pyrimidin-5-ylamino]-nicotinamide dihydrochloride (BAY 61-3606) blocks antigen-induced airway inflammation in rodents. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 2003;306:1174–1181. doi: 10.1124/jpet.103.052316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Seow CJ, et al. Piceatannol a Syk-selective tyrosine kinase inhibitor, attenuated antigen challenge of guinea pig airways in vitro. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2002;443:189–196. doi: 10.1016/s0014-2999(02)01534-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Stenton GR, et al. Inhibition of allergic inflammation in the airways using aerosolized antisense to Syk kinase. J. Immunol. 2002;169:1028–1036. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.169.2.1028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Huang Z-Y, et al. Effect of locally administered Syk siRNA on allergen-induced arthritis and asthma. Mol. Immunol. 2013;53:52–59. doi: 10.1016/j.molimm.2012.06.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Meltzer EO, et al. An intranasal Syk-kinase inhibitor (R112) improves the symptoms of seasonal allergic rhinitis in a park environment. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2005;115:791–796. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2005.01.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sanchez-Mejorada G, Rosales C. Signal transduction by immunoglobulin Fc receptors. J. Leukoc. Biol. 1998;63:521–533. doi: 10.1002/jlb.63.5.521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Van Ziffle JA, Lowell CA. Neutrophil-specific deletion of Syk kinase results in reduced host defense to bacterial infection. Blood. 2009;114:4871–4882. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-05-220806. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kiefer F, et al. The Syk protein tyrosine kinase is essential for Fcγ receptor signaling in macrophages and neutrophils. Mol. Cell. Biol. 1998;18:4209–4220. doi: 10.1128/mcb.18.7.4209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mócsai A, et al. Integrin signaling in neutrophils and macrophages uses adaptors containing immunoreceptor tyrosine-based activation motifs. Nat. Immunol. 2006;7:1326–1333. doi: 10.1038/ni1407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kleinau S, et al. Induction and suppression of collagen-induced arthritis is dependent on distinct Fcgamma receptors. J. Exp. Med. 2000;191:1611–1616. doi: 10.1084/jem.191.9.1611. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Díaz de Ståhl T, et al. Expression of FcgammaRIII is required for development of collagen-induced arthritis. Eur. J. Immunol. 2002;32:2915–2922. doi: 10.1002/1521-4141(2002010)32:10<2915::AID-IMMU2915>3.0.CO;2-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Jakus Z, et al. Genetic deficiency of Syk protects mice from autoantibody-induced arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2010;62:1899–1910. doi: 10.1002/art.27438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Elliott ER, et al. Deletion of Syk in neutrophils prevents immune complex arthritis. J. Immunol. 2011;187:4319–4330. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1100341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bajpai M, et al. Spleen tyrosine kinase: a novel target for therapeutic intervention of rheumatoid arthritis. Expert Opin. Inv. Drug. 2008;17:641–659. doi: 10.1517/13543784.17.5.641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Braselmann S, et al. R406, an orally available spleen tyrosine kinase inhibitor blocks Fc receptor signaling and reduces immune complex-mediated inflammation. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 2006;319:998–1008. doi: 10.1124/jpet.106.109058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Pine PR, et al. Inflammation and bone erosion are suppressed in models of rheumatoid arthritis following treatment with a novel Syk inhibitor. Clin. Immunol. 2007;124:244–257. doi: 10.1016/j.clim.2007.03.543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Coffey G, et al. Specific inhibition of spleen tyrosine kinase suppresses leukocyte immune function and inflammation in animal models of rheumatoid arthritis. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 2012;340:350–359. doi: 10.1124/jpet.111.188441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Liddle J, et al. Discovery of GSK143, a highly potent, selective and orally efficacious spleen tyrosine kinase inhibitor. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2011;21:6188–6194. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2011.07.082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Liao C, et al. Selective inhibition of spleen tyrosine kinase (SYK) with a novel orally bioavailable small molecule inhibitor, RO9021, impinges on various innate and adaptive immune responses: implications for SYK inhibitors in autoimmune disease therapy. Arthritis Research & Therapy. 2013;15:R146. doi: 10.1186/ar4329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Weinblatt ME, et al. Treatment of rheumatoid arthritis with a Syk inhibitor: a twelve week, randomized, placebo-controlled trial. Arthritis Rheum. 2008;58:3309–3318. doi: 10.1002/art.23992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Weinblatt ME, et al. An oral spleen tyrosine kinase (Syk) inhibitor for rheumatoid arthritis. N. EnglJMed. 2010;363:1303–1312. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1000500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Genovese MC, et al. An oral Syk kinase inhibitor in the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis: a three month randomized, placebo controlled phase II study in patients with active rheumatoid arthritis that did not respond to biologic agents. Arthritis Rheum. 2011;63:337–345. doi: 10.1002/art.30114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Mócsai A, et al. The immunomodulatory adapter proteins DAP12 and Fc receptor gamma-chain (FcRgamma) regulate development of functional osteoclasts through the Syk tyrosine kinase. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2004;101:6158–6163. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0401602101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Cha H, et al. A novel spl een tyrosine kinase inhibitor blocks c-Jun N-terminal kinase-mediated gene expression in synoviocytes. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 2006;317:571–578. doi: 10.1124/jpet.105.097436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Gevrey J-C, et al. Syk is required for monocyte/macrophage chemotaxis to CX3CL1 (Fractalkine) J. Immunol. 2005;175:3737–3745. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.175.6.3737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Zarbock A, et al. PSGL-1 engagement by E-selectin signals through Src kinase Fgr and ITAM adapters DAP12 and FcR gamma to induce slow leukocyte rolling. J. Exp. Med. 2008;205:2339–2347. doi: 10.1084/jem.20072660. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Hilgendorf I, et al. The oral spleen tyrosine kinase inhibitor fostamatinib attenuates inflammation and atherogenesis in low-density lipoprotein receptor-deficient mice. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2011;31:1991–1999. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.111.230847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Liossis SN, et al. B cells from patients with systemic lupus erythematosus display abnormal antigen receptor-mediated early signal transduction events. J. Clin. Invest. 1996;98:2549–2557. doi: 10.1172/JCI119073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Moulton VR, Tsokos GC. Abnormalities of T cell signaling in systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis Res. Ther. 2011;13:207. doi: 10.1186/ar3251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Turner M, et al. Perinatal lethality and a block in the development of B cells in mice lacking the tyrosine kinase p72syk. Nature. 1995;378:298–302. doi: 10.1038/378298a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Takata M, et al. Tyrosine kinases Lyn and Syk regulate B cell receptor-coupled Ca2+ mobilization through distinct pathways. EMBO J. 1994;13:1341–1349. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1994.tb06387.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Liossis SN, et al. B-cell kinase lyn deficiency in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus. J. Invest. Med. 2001;49:157–165. doi: 10.2310/6650.2001.34042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Lamagna C, et al. B cell-specific loss of Lyn kinase leads to autoimmunity. J. Immunol. 2014;192:919–928. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1301979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Smith-Garvin JE, et al. T Cell Activation. Ann. Rev. Immunol. 2009;27:591–619. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.021908.132706. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Grammatikos AP, et al. Spleen tyrosine kinase (Syk) regulates systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) T cell signaling. PLoS ONE. 2013;8:e74550. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0074550. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Bahjat FR, et al. An orally bioavailable spleen tyrosine kinase inhibitor delays disease progression and prolongs survival in murine lupus. Arthritis Rheum. 2008;58:1433–1444. doi: 10.1002/art.23428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Deng GM, et al. Suppression of skin and kidney disease by inhibition of spleen tyrosine kinase in lupus-prone mice. Arthritis Rheum. 2010;62:2086–2092. doi: 10.1002/art.27452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Smith J, et al. A spleen tyrosine kinase inhibitor reduces the severity of established glomerulonephritis. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2010;21:231–236. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2009030263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Reilly MP, et al. PRT-060318, a novel Syk inhibitor, prevents heparin-induced thrombocytopenia and thrombosis in a transgenic mouse model. Blood. 2011;117:2241–2246. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-03-274969. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Podolanczuk A, et al. Of mice and men: an open-label pilot study for treatment of immune thrombocytopenic purpura by an inhibitor of Syk. Blood. 2009;113:3154–3160. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-07-166439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Sedlik C, et al. A critical role for Syk protein tyrosine kinase in Fc receptor-mediated antigen presentation and induction of dendritic cell maturation. J. Immunol. 2003;170:846–852. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.170.2.846. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Colonna L, et al. Therapeutic targeting of Syk in autoimmune diabetes. J. Immunol. 2010;185:1532–1543. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1000983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Carden DL, Granger DN. Pathophysiology of ischaemia-reperfusion injury. J. Pathol. 2000;190:255–266. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1096-9896(200002)190:3<255::AID-PATH526>3.0.CO;2-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Pamuk ON, et al. Spleen tyrosine kinase inhibition prevents tissue damage after ischemia-reperfusion. Am. J. Physiol. Gastrointest. Liver Physiol. 2010;299:G391–G399. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00198.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Shi Y, et al. Protein-tyrosine kinase Syk is required for pathogen engulfment in complement-mediated phagocytosis. Blood. 2005;107:4554–4562. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-09-3616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Ishizuka F, et al. Toll-like receptor 4 mediates retinal ischemia/reperfusion injury through nuclear factor-κB and spleen tyrosine kinase activation. Invest. Opththalmol. Vis. Sci. 2013;54:5807–5816. doi: 10.1167/iovs.13-11932. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Chaudhary A. Tyrosine kinase Syk associates with toll-like recpeotr 4 and regulates signaling in human monocytic cells. Immunol. Cell Biol. 2007;85:249–256. doi: 10.1038/sj.icb7100030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Miller YI, et al. The SYK side of TLR4: signaling mechanisms in response to LPS and minimally oxidized LDL. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2012;167:990–999. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.2012.02097.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Coopman PJ, et al. The Syk tyrosine kinase suppresses malignant growth of human breast cancer cells. Nature. 2000;406:742–747. doi: 10.1038/35021086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Coopman PJ, Mueller SC. The Syk tyrosine kinase: a new negative regulator in tumor growth and progression. Cancer Lett. 2006;241:159–173. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2005.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Moroni M, et al. Progressive loss of Syk and abnormal proliferation in breast cancer cells. Cancer Res. 2004;64:7346–7354. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-03-3520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Yuan Y, et al. Hypermethylation leads to silencing of the SYK gene in human breast cancer. Cancer Res. 2001;61:5558–5561. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Blancato J, et al. SYK allelic loss and the role of Syk-regulated genes in breast cancer survival. PloS One. 2014;9(2):e87610. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0087610. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Bailet O, et al. Spleen tyrosine kinase functions as a tumor suppressor in melanoma cells by inducing senescence-like growth arrest. Cancer Res. 2009;69:2748–2756. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-2690. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Yuan Y, et al. Frequent epigenetic inactivation of spleen tyrosine kinase gene in human hepatocellular carcinoma. Clin. Cancer Res. 2006;12:6687–6695. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-06-0921. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Hong J, et al. CHK1 targets spleen tyrosine kinase (L) for proteolysis in hepatocellular carcinoma. J. Clin. Invest. 2012;122:2165–2175. doi: 10.1172/JCI61380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Layton T, et al. Syk tyrosine kinase acts as a pancreatic adenocarcinoma tumor suppressor by regulating cellular growth and invasion. Am. J. Pathol. 2009;175:2625–2636. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2009.090543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Rinaldi A, et al. Genomic and expression profiling identifies the B-cell associated tyrosine kinase Syk as a possible therapeutic target in mantle cell lymphoma. Brit. J. Haematol. 2006;132:303–316. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2005.05883.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Chen L, et al. SYK-dependent tonic B-cell receptor signaling is a rational treatment target in diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. Blood. 2008;111:2230–2237. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-07-100115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Baudot AD, et al. The tyrosine kinase Syk regulates the survival of chronic lymphocytic leukemia B cells through PKCdelta and proteasome-dependent regulation of Mcl-1 expression. Oncogene. 2009;28:3261–3273. doi: 10.1038/onc.2009.179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Buchner M, et al. Spleen tyrosine kinase is overexpressed and represents a potential therapeutic target in chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Cancer Res. 2009;69:5424–5432. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-4252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Young RM, et al. Mouse models of non-Hodgkin lymphoma reveal Syk as an important therapeutic target. Blood. 2009;113:2508–2516. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-05-158618. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Hatton O, et al. Syk activation of phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase/Akt prevents HtrA2-dependent loss of X-linked inhibitor of apoptosis protein (XIAP) to promote survival of Epstein-Barr virus+ (EBV+) B cell lymphomas. J. Biol. Chem. 2011;286:37368–37378. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.255125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Rickert RC. New insights into pre-BCR and BCR signalling with relevance to B cell malignancies. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2013;13:578–591. doi: 10.1038/nri3487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Monroe JG. ITAM-mediated tonic signalling through pre-BCR and BCR complexes. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2006;6:283–294. doi: 10.1038/nri1808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Hahn CK, et al. Proteomic and genetic approaches identify Syk as an AML target. Cancer Cell. 2009;16:281–294. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2009.08.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Feldman A, et al. Overexpression of Syk tyrosine kinase in peripheral T-cell lymphomas. Leukemia. 2008;22:1139–1143. doi: 10.1038/leu.2008.77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Miller PG, et al. In vivo RNAi screening identifies a leukemia-specific dependence on integrin beta 3 signaling. Cancer Cell. 2013;24:45–58. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2013.05.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Friedberg JW, et al. Inhibition of Syk with fostamatinib disodium has significant clinical activity in non-Hodgkin lymphoma and chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Blood. 2010;115:2578–2585. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-08-236471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Herman SEM, et al. Fostamatinib inhibits B-cell receptor signaling, cellular activation and tumor proliferation in patients with relapsed and refractory chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Leukemia. 2013;27:1769–1773. doi: 10.1038/leu.2013.37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Singh A, et al. A gene expression signature associated with “K-Ras addiction” reveals regulators of EMT and tumor cell survival. Cancer Cell. 2009;15:489–500. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2009.03.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Chen X, et al. A novel retinoblastoma therapy from genomic and epigenetic analyses. Nature. 2012;481:329–334. doi: 10.1038/nature10733. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Katz E, et al. MMTV Env encodes an ITAM responsible for transformation of mammary epithelial cells in three-dimensional culture. J. Exp. Med. 2005;201:431–439. doi: 10.1084/jem.20041471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Prinos P, et al. Alternative splicing of SYK regulates mitosis and cell survival. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2011;18:673–679. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.2040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Carnevale J, et al. SYK regulates mTOR signaling in AML. Leukemia. 2013;27:2118–2128. doi: 10.1038/leu.2013.89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Leseux L, et al. Syk-dependent mTOR activation in follicular lymphoma cells. Blood. 2006;108:4156–4162. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-05-026203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Gobessi S, et al. Inhibition of constitutive and BCR-induced Syk activation downregulates Mcl-1 and induces apoptosis in chronic lymphocytic leukemia B cells. Leukemia. 2009;23:686–697. doi: 10.1038/leu.2008.346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Ding Q, et al. Degradation of Mcl-1 by beta-TrCP mediates glycogen synthase kinase 3-induced tumor suppression and chemosensitization. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2007;27:40006–4017. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00620-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Chen L, et al. SYK inhibition modulates distinct PI3K/AKT- dependent survival pathways and cholesterol biosynthesis in diffuse large B cell lymphomas. Cancer Cell. 2013;23:826–838. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2013.05.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Puissant A, et al. SYK is a critical regulator of FLT3 in acute myeloid leukemia. Cancer Cell. 2014;25:226–242. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2014.01.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Davis MI, et al. Comprehensive analysis of kinase inhibitor selectivity. Nature Biotech. 2011;29:1046–1051. doi: 10.1038/nbt.1990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Burke RT, et al. A potential therapeutic strategy for chronic lymphocytic leukemia by combining Idelalisib and GS-9973, a novel spleen tyrosine kinase (Syk) inhibitor. Oncotarget. 2014;5:908–915. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.1484. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Spurgeon SE, et al. The selective SYK inhibitor P505-15 (PRT062607) inhibits B cell signaling and function in vitro and in vivo and augments the activity of fludarabine in chronic lymphocytic leukemia. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 2013;344:378–387. doi: 10.1124/jpet.112.200832. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]