Abstract

HIV disproportionately affects women, which propagates the disparities gap. This study was designed to (a) explore the personal, cognitive, and psychosocial factors of intimate partner violence (IPV) among women with HIV, (b) explore the perceptions of male perpetrators’ roles in contributing to violence, and (c) determine the implications for methodological and data source triangulation. A concurrent mixed methods study design was used including 30 African American male and female participants. Quantitative data were analyzed using descriptive statistics. Eleven themes were identified in the qualitative data from the female (n = 15) and 9 themes from the male (n = 15) participant interviews using Giorgi’s technique. Data sources and methodological approaches were triangulated with relative convergence in the results. Preliminary data generated from this study could inform gender-based feasibility research studies. These studies could focus on integrating findings from this study in HIV/IPV prevention interventions and provide clinical support for women.

Keywords: AIDS, African-American women, health disparities, HIV, intimate partner violence, male perpetrators, mixed methods study

Disparities in health access and outcomes are global challenges, particularly affecting people of African origin irrespective of country of residence. In the United States, African Americans (AAs) make up 13% of the population; however, 45% of those living with HIV are AA. AA women make up 55.7 per 100,000 of those living with HIV, and AA men make up 115.7 people living with HIV (PLWH) per 100,000 population (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [CDC], 2010). Women are disparately affected by HIV because of myriad vulnerabilities such as social norms, resource access inequality and inequity, and other gender-based inequities with subsequent power imbalances (Tillerson, 2008). Studies have demonstrated that these vulnerabilities encompass contextual and structural determinants of HIV infection similar to determinants of intimate partner violence (IPV). Substantive pathways for HIV infection and IPV demonstrate bidirectional relationships (Gielen et al. 2007; Sareen, Pagura, & Grant, 2009).

To address these problems, intervention studies have focused on factors and vulnerabilities such as gender inequities, harmful social norms, power imbalances, and interrelationship dynamics with a primary male partner (CDC, 2011; Wyatt et al., 2011). However, more effective and sustainable gender-based interventions are needed. Furthermore, men’s perceptions of their roles in violence against women and potentially placing women at risk for HIV are important in the relationship dynamic, and this needs to be systematically investigated. No research study was found that simultaneously investigated women’s violence experiences and the perceptions of male perpetrators’ roles in a mixed methods study, which is the focus of this study. Relationship dynamics cannot be fully examined and effectively addressed without exploring the male perspective. Although studies have investigated these concepts separately, the need for female and male data sources and quantitative and qualitative triangulation study is warranted. This study will generate preliminary data to inform the design of more effective and sustainable prevention interventions tailored to the unique needs of AA women who are survivors of IPV. These interventions could be applied in clinical practice to support women survivors as well as to help male perpetrators address vulnerabilities and propensities for abusive behaviors through behavioral intervention programs.

To address this research gap, a mixed methods study was conducted that included both female and male participants. The purposes of this study were to (a) examine and explore the personal (demographic characteristics and substance use), cognitive (HIV knowledge and self-efficacy), and psychosocial (sexual power relationships, IPV, intention to use condoms) factors of IPV among AA women with HIV; (b) explore the perceptions of male perpetrators’ roles in contributing to abuse against female partners; and (c) determine the implications of methodological and data source triangulation.

Background

HIV Prevalence: United States and Baltimore

There are approximately 1.1 million people living with HIV in the United States with AAs being disproportionately affected. HIV and related complications are the leading causes of death for AAs, who also have a shorter life span than their White counterparts because of health care disparities (CDC, 2010). In Baltimore, HIV prevalence showed a decline of as much as 10% in the last 10 years, yet AAs continue to be disproportionately affected by HIV. AAs are eight times more likely to die of the disease as compared to Whites. As of 2008, 16,532 persons in Baltimore were living with HIV, of whom 88.5% were of the AA racial group, and 38.7% of those were women (Baltimore City, 2008; Maryland Department of Health & Mental Hygiene, 2008). Compared to their White counterparts, AA women are at increased HIV risk due to gender norms, low economic status leading to behaviors such as transactional sex, and multiple sexual partners (Sareen et al., 2009). IPV is a critical component of HIV risk and infection. Researchers have addressed these factors in HIV prevention interventions with some effect (Wyatt et al., 2011). However, integrating information gained from understanding male perpetrators’ roles in propagating violence against women is critically needed to ensure effective, culturally-relevant, and sustainable interventions.

Intimate Partner Violence and HIV Infection

The CDC has defined IPV as “abuse that occurs between two people in a close relationship and includes physical, sexual, threats, and emotional abuse” (CDC, 2009). In a systemic review of evidence, Campbell et al. (2008) reported that the prevalence rate for physical IPV was as high as 61% in a population-based study. AA have the highest prevalence of IPV even after socioeconomic status has been adjusted (Bent-Goodley, 2007). Gender roles and inequity have been shown to be pervasive given the perceptions of the traditional male dominant role and behaviors that lead to violence (Rosenthal & Levy, 2010).

AA women face numerous risks and vulnerabilities, and IPV is one of the critical risk factors for HIV infection in this population. For example, power imbalances inherent in IPV relationships are strongly associated with an inability to negotiate safe sex and/or use condoms for protection (Wingood & DiClemente, 2000). The long-term negative personal, psychosocial, and emotional health consequences of IPV may lead to limited access to the essential health care services needed to avert complications, promote health, and prevent diseases (Campbell et al., 2002). Researchers have reported positive correlations between IPV and HIV risk behaviors and HIV infection (El-Bassel, Gilbert, Wu, Go, & Hill, 2005), which highlight global and public health prevention efforts (Silverman, Decker, Saggurti, Balaiah, & Raj, 2008). In addition, HIV risk behaviors such as drug use and childhood sexual abuse have been associated with lifetime domestic violence (Aaron, Criniti, Bonacquisti, & Geller, 2013) . HIV infection and IPV bidirectional relationships have led to continuing disproportionate HIV prevalence rates for women globally (Sareen et al., 2009). Furthermore, it has been demonstrated that beliefs, attitudes, perceived HIV risk, intention to use condoms, and knowledge influence the IPV and HIV dynamic (Mattson & Ruiz, 2005).

Beliefs and HIV Infection

Beliefs and knowledge are related to people’s perceptions of gender roles in IPV relationships. For example, one belief is that men are justified to perform sexual acts on women without their consent (Mattson & Ruiz, 2005). Researchers investigating gender attitudes and beliefs related to traditional roles found that having negative attitudes toward women was significantly associated with HIV risk behaviors (Pulerwitz, Gortmaker, & Dejong, 2000). In addition, intention to change behavior may not lead to actual change if barriers such as power imbalances hinder this change. Specifically, it has been shown that women intend to use condoms but that intent fails to translate to actual use because of fear of violence from partners and inability to negotiate safe sex (Wingood & DiClement, 2000). This underscores the notion that power imbalance is central to IPV, risks, and other vulnerabilities for HIV infection. It is also concerning that women may not perceive themselves to be at risk even though their partners may be engaged in risky behaviors (Njie-Carr, Sharps, Campbell, & Callwood, 2012).

Conceptual Framework - The Integrated Model

The Integrated Model (IM; Fishbein, 2000) provided the conceptual background for the study. The IM integrates constructs from the Health Belief Model (HBM), Theory of Planned Behavior (TPB), and Social Cognitive Theory (SCT) to explain HIV risk behaviors. The IM is based on the belief that intentions directly influence behaviors, which in turn are influenced by attitudes, normative beliefs, and self-efficacy. Normative beliefs such as social, spiritual, and cultural beliefs are found in all three theories. Self-efficacy skills and knowledge, as well as environmental constraints not in the TPB, are addressed in the SCT, rendering the IM comprehensive in targeting important factors of HIV in AA women (Fishbein, 2000). Specific to this study, abused AA women experience unequal power in their relationships, thereby limiting their abilities to negotiate safe sex, make decisions to prevent HIV infection, or seek access to care (Lichtenstein, 2006; Wingood & DiClemente, 2000). Important study variables such as sexual power relationships (relationship control and decision-making dominance), substance use, current and lifetime abuse, were integrated into the IM. Wyatt et al. (2011) have suggested that gender-based, culturally-specific HIV prevention programs that address AA women will be helpful and supportive.

Methods

Study Design

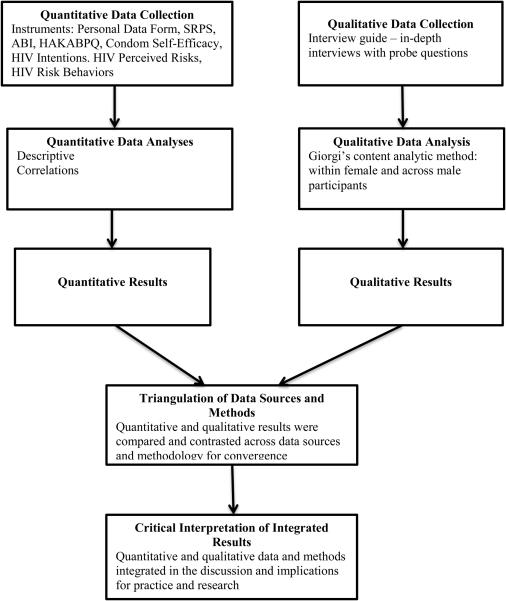

A concurrent mixed methods study design was used. The goal of the mixed methods design was to adequately capture multiple dimensions of male and female participant experiences by comparing and contrasting qualitative and quantitative results. The qualitative component was guided by Giorgi’s method. This phenomenological descriptive approach was thought to be appropriate because it would help gain a better understanding of AA women’s lived experiences of abuse and AA men’s perceptions of their roles as perpetrators of violence (Dowling & Cooney, 2012).

In this study, it was important to capture unique contributions of each methodological approach in the context of the participants’ cultural and social relationship experiences in order to triangulate the findings. Data triangulation serves to increase validity and complement findings (Creswell & Tashakkori, 2007), which was an important goal of this study. Findings from this study could help to comprehensively explain and provide clearer understanding of HIV-infected women’s experiences and male perpetrators roles in increasing violence. Figure 1 illustrates the steps in the study.

Figure 1.

Illustration of steps conducted in this mixed methods triangulation study.

Note: SRPS = Sexual Relationship Power Scale; ABI = Abusive Behavior Inventory; HAKABPQ = HIV/AIDS Knowledge, Attitudes, and Beliefs Patient Questionnaire

Study Sample

A purposive sample of 15 AA male and 15 AA female participants took part in the study. Qualitative research scholars suggest that 12 to 15 participants are adequate to reach data saturation (Sandelowski, 2000). In this study, data saturation was reached with 15 participants as demonstrated by recurring themes.

Inclusion criteria for all participants were: (a) ages 18 and older, (b) living in Baltimore, and (c) able to read and write English. Additional inclusion criteria for females were: (a) medically diagnosed with HIV (self-reported and validated using electronic medical records from a desktop computer), and (b) had experienced IPV physical or sexual violence, or threat of physical or sexual violence in the previous 12 months. An additional inclusion criterion for males was having perpetrated IPV against past or current female partners in the previous 12 months. Participants were excluded if (a) they failed to meet the above inclusion criteria, or (b) had any disability or illness/disease that prevented them from completing the interviews and questionnaires. All male participants self-reported not having HIV, which could not be validated because no medical records were available for review.

Settings

AA female participants were recruited from a comprehensive HIV clinic that included a multidisciplinary team of physicians, nurse practitioners, case managers, and psychiatrists who provided holistic care to patients. AA male participants were recruited from a court-mandated rehabilitation program that provided conflict and anger management skills to domestic abuse offenders. Both data collection sites were located in Baltimore.

Procedure and recruitment

Institutional Review Board (IRB) approval was obtained from the Johns Hopkins University prior to data collection, which began April 6, 2010, and ended July 14, 2010. The study protocol included an evidence-based safety protocol specific to abused women (Langford, 2000) to ensure safety during and after the data collection process. Prior to the start of data collection, the investigator and research assistants met with staff at the HIV clinic and the rehabilitation program site. They provided staff with the study objectives and data collection process and solicited best strategies to recruit participants. This step was important to gain support and confidence for a smooth recruitment and data collection process. Further, a meeting was held with potential male participants during one of their classes to inform them about the study. Next, flyers were posted at both sites. Other recruitment strategies included the snowball technique. The investigator asked potential female participants to contact her by phone if they were interested in joining the study. Male participants were asked to place their initials on a flyer that was posted on their bulletin board to maintain anonymity. Potential participants were enrolled in the study after meeting study criteria and receiving study information. Female participants provided signed informed consent, and male participants provided verbal consent.

Data Collection for all Phases

Female and male participants completed the interview and instruments in one office visit. To ensure consistency across the research team (project investigator and research assistants), a data collection guide was included as a cover sheet that itemized the sequence of activities during the data collection process: (a) introductions and brief overview of the study, (b) consent with either a signed form (female) or verbal agreement (male), (c) personal data form/review of medical records, (d) interview using interview guide, (e) completion of eight survey instruments, and (f) provision of health information brochure.

All interviews were tape-recorded using a digital tape recorder, and each lasted approximately 75 minutes. Participants were then asked to complete the instruments. The research team made sure that participants completed all instruments before they left the room to minimize missing data. Participants were provided with a $40 incentive for completing the interview and the research instruments. A Verification of Confidential Nature form was completed for the male participants prior to the study, as required by the IRB. Female participants signed the petty cash voucher form to validate receipt of the $40 incentive.

Phase One: Qualitative Component

Data collection

Research questions for the qualitative component were: (a) What are the personal, cognitive, and psychosocial experiences of AA women with HIV who experience violence? and (b) What are the perceptions of AA male participants’ roles in propagating violence against AA women? A semi-structured interview guide was developed by the investigator and included questions related to HIV knowledge, attitudes, and beliefs; relationship pattern related to power and dominance; intimate partner abuse experiences; substance use; and child abuse experiences. The main components of the interview guide were related to instrument items with appropriate probe questions to direct the interview. Sample questions for the women included the following: “Tell me about the relationship with your partner (ex-partner)? Do you feel you have the power to make decisions in your relationship? Do you feel you could have stopped or prevented the violence?” For male participants, sample questions included, “Tell me about your partner’s (ex-partner’s) contribution to making decisions in your relationship. Give me examples. What do you think caused the conflict and violence with your partner (ex-partner)? Do you feel you could have stopped or prevented the conflict and violence?” To protect the participants’ identities, pseudonyms are used to report the findings.

Data analyses

A transcriptionist transcribed the tape-recorded interview data. The transcripts were analyzed by manual analysis utilizing Giorgi’s phenomenological analytic technique (Sandelowski, 2000). Giorgi’s technique is a four-step approach consistent with the philosophy of Husserl’s descriptive phenomenology. First, the research team, which included the primary investigator (PI) and two graduate research assistants (GRAs), separately read each transcript line by line, looking for patterns in content that were similar within and across female and male participant interviews. The PI, who has had experience collecting and analyzing qualitative data, trained the GRAs. The team read and re-read the transcripts, clarifying transcribed data by listening to recorded interviews. Second, similar patterns of meanings from each source (male or female) were identified and clustered into categories related to the emerging themes. Third, the research team determined meanings related to women’s abuse experiences as well as perceptions of men’s roles in perpetrating violence. Themes were also compared across male and female responses to determine convergence. Fourth, themes were synthesized and conceptualized within the context of the participants’ experiences. Analyses were conducted in an iterative process to ensure that themes were consistent with the raw data and could be identified across samples.

For trustworthiness and rigor, the following steps were taken to ensure credibility, confirmability, and auditability. To ensure credibility and confirmability: (a) The investigator developed the interview guide to ensure that data generated were related to the participants’ violence experiences as specified in the study purposes, (b) categories in the interview were consistent with quantitative instruments, (c) participants were strongly encouraged to be honest with their responses, (d) appropriate probing questions were used, (e) data collection and analyses were triangulated, (f) data collection and analyses were conducted in an iterative process, and (g) the investigator had experience conducting studies with similar key variables in this vulnerable population. Giorgi’s technique does not require investigators to return the themes to participants for validation, so member checking was not done. To ensure auditability, the transcribed interviews, raw data, and the field notes during data collection can be traced in an audit trail.

Phase Two: Quantitative Component

Data collection

Research questions that undergirded the quantitative component of the study were: (a) What are the relationships between personal, cognitive, and psychosocial factors among AA HIV-infected female participants who experience violence? and (b) What are the relationships between personal, cognitive, and psychosocial factors among AA male perpetrators of violence? Seven instruments, which had demonstrated acceptable reliability and validity in previous studies and had been used with AAs and other population groups, were used. The instruments included the following:

The Personal Data form (22 items) asked participants to provide demographic characteristics and medical information. The women’s medical information was validated from medical records.

The Sexual Relationship Power Scale (α = .84) measured power and dominance in intimate relationships (Pulerwitz et al., 2000). The tool consists of the Relationship Control (α = .86) and Decision-Making (α = .62) subscales.

The HIV and AIDS questionnaire (α = .94) measured knowledge, attitudes, and beliefs about HIV and included five subscales: Knowledge (α = .85), Attitudes (α = .75), Social Beliefs (α = .74), Spiritual Beliefs (α = .84), and Cultural Beliefs (α = .87; Njie-Carr, 2005).

The Condom Self-Efficacy Scale (α = .85; Hanna, 1999) measured skills in effective communication when planning to use condoms and safe application of condoms.

The Abusive Behavior Inventory (α = .80 - .92; Shepard & Campbell, 1992) measured psychological, sexual, emotional, and physical dimensions of abuse.

The HIV Intentions Scale (α = .75 - .81; Melendez, Hoffman, Exner, Leu, & Ehrhardt, 2003) measured intent to use condoms to protect self and others.

The Perceived HIV Risk Scale (α= .77; Harlow, 1989) measured perception of risk to get infected with HIV.

The HIV Risk Behavior Inventory (KR-20 = .74; Gerbert, Bronstone, McPhee, Pantilat, & Allerton, 1998) measured HIV risk behaviors such as multiple partners, not using protection, and diagnosis with sexually transmitted diseases.

Table 1 provides information on the number of items for each instrument, comparing the internal consistency assessments on the instruments between male and female participants.

Table 1.

Internal Consistency and Mean Results of the Instruments (N =30)

| Instrument | Female (n = 15) | Male (n = 15) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (# of items) | Alpha | M (SD) | Alpha | M (SD) |

| Total Relationship Power Scale | 45.3 (12.3) | 55.6 (5.9) | ||

| Relationship Control Sub-scale (15) | .92 | 31.8 (9.6) | .72 | 39.8 (5.5) |

| Decision-Making Dominance (8) | .89 | 13.5 (4.5) | .21 | 15.8 (1.9) |

| HIV/AIDS Questionnaire | ||||

| Attitudes (14) | .93 | 40.9 (5.6) | .83 | 39 (5.1) |

| Knowledge (12) | .91 | 46.9 (6.7) | .66 | 4.9 (3.8) |

| Social Beliefs (10) | .84 | 29.8 (5.3) | .85 | 29.9 (4.4) |

| Spiritual Beliefs (12) | .93 | 43.2 (4.8) | .96 | 41.5 (7.3) |

| Cultural Beliefs (12) | .77 | 38 (4.3) | .83 | 38.9 (4.1) |

| Condon Self-Efficacy Scale (14) | .87 | 58.1 (9.1) | .84 | 54.7 (8.9) |

| Abusive Behavior Inventory | ||||

| Psychological Abuse (18) | .94 | 29.5 (18.5) | .90 | 18 (13.7) |

| Physical Abuse (11) | .89 | 17.7 (11.5) | .85 | 5.7 (5.9) |

| HIV Intentions Scale (9) | .80 | 37.5 (10.1) | .73 | 22.9 (7.0) |

Items on the Abuse Inventory instrument were developed specifically for women respondents, so some items were modified for male participants. Internal consistency was established after the inventory was modified as reported in Table 1. Field notes were maintained to document information including questions related to difficulties completing the instruments and the length of time it took participants to complete them. Participants did not report any issues related to items on the instruments or the 20-30 minutes it took to complete all the instruments.

Analyses of data

Quantitative data were analyzed using the Statistical Package for Social Sciences 17.0 software. Quantitative data were analyzed using frequencies, percentages, and correlations to describe the data and examine relationships among key variables.

Triangulation of Data Sources and Research Methods

One of the goals of this concurrent mixed methods design study was to triangulate female and male data sources and the qualitative and quantitative results. Triangulation is desirable in mixed methods research because it serves as validation and confirmation of the phenomena being studied (O'Cathain, Murphy, & Nicholl, 2007). To conduct triangulation, qualitative and quantitative analyses were conducted separately. The results were then compared and contrasted to identify data convergence and divergence (see Figure 1).

Findings

Demographic Characteristics

The average age of the female participants was 46.2 years, compared to 38.9 years for male participants. More than 26% (n = 4) of female participants had more than a high school education, compared to 6.7% (n = 1) for males. However, more men (40%; n = 6) were employed compared to women (6.7%; n = 1). Mean income per week for females was $136.67 USD (SD = $98.51) and $281.33 USD (SD = $186.16) for male participants. When participants were asked about current and past substance use, 20% (n = 3) of females reported current substance use and 66.7% (n = 10) reported past use; 26.7% (n = 4) of males reported current substance use and 40% (n = 6) reported past use.

HIV Risk Behaviors

The HIV Risk Behavior Inventory is a dichotomous instrument that assessed participant risk behaviors. Table 2 presents information comparing female and male participants on specific risk behaviors. Male participants were more likely to engage in unprotected oral, vaginal, and anal sex. Two women (13.3%) reported transactional sex. Positive (yes) responses were added to obtain a total score. The higher the score, the higher the risk factors for HIV. Female participants’ scores ranged from 1- 6 in this sample with a possible maximum score of 12.

Table 2.

Comparison of Select HIV Risk Behaviorsxs

| Risk Behavior | Female (n = 15) | Male (n = 15) |

|---|---|---|

| Had sex with > 1 partner | 2 (13.3%) | 4 (26.7%) |

| Unprotected sex (includes primary | ||

| and secondary partners) | ||

| Oral | 4 (26.7%) | 14 (93.3%) |

| Vaginal | 5 (33.3%) | 14 (93.3%) |

| Anal | 0 | 5 (33.3%) |

| Condoms with primary partner | 13 (86.7%) | 6 (40%) |

| Use of alcohol and drugs with sex | 6 (40%) | 2 (13.3)% |

|

Have/had a sexually-transmitted

infection |

9 (60%) | 6 (40%) |

Phase One: Qualitative Results

Themes derived from male and female participants were included in the analyses. Additionally, unique contributions of data from both groups were discussed. However, the emphasis of the analyses was on the themes that were similar using the triangulation of sources and methods. Similar themes (convergence) and themes that were found to be different (divergence) were discussed.

Eleven themes were identified for the female participants. The 11 themes were: HIV infection from abusive partner; preventing HIV transmission; male dominant role and power dynamic in the relationship; afraid of partner because of abuse; multiple abuse experiences in the relationship; psychological effects related to abuse; perceived reasons for abuse by partner; perceived strategies that could have prevented abuse; childhood abuse experiences; the use of support systems to mitigate effects of abuse; and women’s health care needs related to abuse. The women reported that, although the injuries they sustained from abuse may have required medical care, they failed to seek care because of fear. One woman reported that she waited until it was so serious that her family members had to call an ambulance. Adele, a 34-year-old women reported:

I went to my grandmother’s house and I laid down [be]cause I was in so much pain and I wouldn’t tell them that he hit me, … and I went to the bathroom and I got dizzy … passed out. They called the ambulance.

Female participants also reported not seeking medical care because of their perceptions of health care providers’ attitudes and lack of concern to address their emotional needs.

Abuse experiences were reported in connection with a partner’s alcohol and substance abuse. There was pervasive use of alcohol and drugs among male partners (8 of 15 in this sample), which led to abusive behaviors. Cecilia and Ellen captured the experience in this way: “It was the drugs mostly, when we were doing drugs, we couldn’t agree on anything …” (Cecilia, 48 years); … I think the drugs played a part, and that’s why he lashes out” (Ellen, 53 years). Andrea (54 years) noted, “… He just went crazy. The drugs and alcohol took him over. … He tells me it wasn’t him and it was the drugs …”

Among female participants, violence experiences ranged from mild bruises to threats with guns and exposure to rape by their partners. Four women reported contracting HIV from abusive partners, suggesting a direct link between HIV infection and abuse experiences.

Eight themes were identified from the male participant interviews. These included: communication issues with female partners; decision-making roles and power; patriarchal ideology and need to control and institute power; childhood abuse experiences; abusive behaviors against female partners; perceived reasons for abusing female partners; personal reaction after abusing partner; strategies to prevent perpetrating violence; and lack of good male role models. Joseph (39 years) described it this way: “Comes from probably me growing up and watching my dad deal with women and it did rub off on me …. It created an unstable environment for me watching them fighting.” David, a 38 year old, noted, “I watched my father. My mother was scared of him – whatever he said, that’s what went. He say pour water for 2 days, she’ll pour water for 2 days. So for a long time, that’s how I thought.” (b) Male perpetrators’ thoughts about preventing abuse included reports by Gabriel (45 years): “So I figured if I was a better listener and we communicated more I think that would have helped a lot.” Both male and female participants reported that the control women had in the relationship was only related to domestic chores. The male partner, who had control and power in the relationship, made the important decisions. Male participants reported that they felt sad after they abused their partners. Andrew (23 years) told his story this way, “I felt sorry, I felt very sorry for putting my hands on her … I felt like I could have hurt her in more ways with my mouth, I didn’t have to touch her.”

Phase Two: Quantitative Results

Data from female participants were analyzed using zero-order correlations between the demographic and key study variables. Because of the number of variables, a Bonferroni correction was computed, which determined a p value ≤.003 for correlations to be deemed significant. A Bonferroni correction was appropriate to adjust for multiple variables to minimize inflating alpha, which would lead to type I error. Significant correlations were found with some of the variables. Women’s age was found to be strongly and positively correlated with education. There was also a strong, positive correlation between psychological abuse and social beliefs. A surprising finding was that women who had strong social support also demonstrated high psychological abuse experiences (r = .718, p = .003). Not surprisingly, there was a positive relationship between psychological abuse and physical abuse (r = .845, p ≤ .001). A negative relationship was found between psychological abuse and relationship control (r = − .750, p ≤ .001). The women who experienced psychological abuse reported less control in their relationships. See Table 3 for correlational analyses results.

Table 3.

Pearson’s Correlation Results for Female Participants

| Age | Education | Knowledge | Attitudes | Social Beliefs |

Cultural Beliefs |

Spiritual Beliefs |

Physical Abuse |

Psychological Abuse |

Relationship Control |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | - | .743** | −.375 | −.119 | −.398 | −.094 | −.120 | −.565 | −.418 | .497 |

| Education | - | −.111 | .014 | −.395 | −.109 | .038 | −.700 | −.492 | .376 | |

| Knowledge | - | .875** | .564 | .679 | .695 | .460 | .368 | −.163 | ||

| Attitudes | - | .447 | .887** | .887 | .358 | .290 | .005 | |||

| Social Beliefs | - | .450 | .442 | .718* | .718 | −.672 | ||||

| Cultural Beliefs | - | .829** | .496 | .381 | .084 | |||||

| Spiritual Beliefs | - | .431 | .439 | −.168 | ||||||

| Physical Abuse | - | .845** | −.501 | |||||||

| Psychological Abuse | - | −.750** | ||||||||

| Relationship Control | - |

p = .003;

p ≤ .001.

Data from the male participants showed significant positive relationships between age and relationship control (r = .769, p = .001), suggesting that the older the male participant, the more likely he controlled the relationship and dominated his partner(s). Positive and statistically significant results were also found between knowledge and attitudes.

Phase Three: Triangulation of Female and Male Data Sources

When female and male data sources were triangulated, data convergence was noted with similar themes expressed by male and female participants. Both groups shared the perception that males dominated relationships, resulting in power imbalances. For example, on the theme related to male dominant role and power dynamics for females, a similar theme was patriarchal ideology and the need to control and institute power. In addition, most of the male and female participants reported childhood abuse. When asked how their experiences as children impacted adulthood, participants reported that negative childhood experiences might have resulted in the use of substances and alcohol, and for males being abusive to their female partners. Female participants reported that childhood abuse might have led to the tendency to have abusive partners because they did not know or experience positive relationships. This was exemplified when a female participant reported continued abuse from a female partner after she left her male partner because of abuse. Additionally, both groups felt that the male partners’ inabilities to effectively communicate about their feelings may have contributed to the violence. Most important, perhaps, was that both groups made suggestions that they perceived could have prevented previous abuses and could prevent future ones.

Table 4 presents themes and related exemplars that converged in this study after integrating interview data from male and female participants. Although female and male participants gave reasons about why the abuse occurred, relative divergence (differences in results) was noted regarding perceived reasons for abuse experienced by women’s and men’s perceived motivations for abusing female partners. For example, female participants noted that a partner’s level of education, inability to deal with stress, and drugs may have contributed to her vulnerability to abusive experiences. Male participants reported that they were stressed and frustrated in their efforts to make a living, which resulted in abusive tendencies.

Table 4.

Integration of Female and Male Qualitative The mes With Related Exemplars

| Female Themes | Female Exemplars | Male Themes | Male Exemplars |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Male dominant

role and power dynamics in the relationship |

Probably does everything he says, go where he wants. (Patricia, 43 years) |

Patriarchal

ideology and need to control and institute power |

In my family, women had their roles and men had their roles …. (Harold, 47 years) …I had the power to make [decisions], I was the man in the relationship, I believe when you [are] in a relationship the man is supposed to be the man …” (David, 38 years) |

|

Multiple abuse

experiences in the relationship |

…if I wasn’t in the mood he would take the sex, so it was bad, it was bad. It got to the point if I didn’t agree, he would threaten my mom to me, not threaten her but he would say what he would do to the family, [be]cause he was connected with some of the high drug dealers. He would throw that in my face a lot, “You can’t run, you can’t hide. I will kill you before you leave me.” (Michelle, 41 years) |

Abusive

behaviors against female partner |

I would hit her. I would basically grab her and wrestle her. I do it on purpose because I’m stronger than her so I will do it like that and if anything I will just wrestle her for real when it got too serious. I started smacking her … (James, 23 years) I should just shoot you in your face … (Sylvester, 28 years) |

|

Perceived

reasons for abuse by partners |

… his level of education, his limited vocabulary, his inability to deal with stressful situations, I think the drugs play a part, I think he can’t express himself any other way and that’s why he lashes out. (Ellen, 53 years) |

Perceived

reasons for abusing partner |

I think the thing that caused my anger is that I’m trying to do so much to survive and seems like nothing good is happening in my life right now. (Andrew, 23 years) Small petty things like the house being out of order, company coming over too much, staying out too late, phone calls, texting a lot. Things like that actually caused both of us to start saying things to each other to make each other want to do what we were doing even more. …very aggressive, I feel very violent. I feel even more violent actually with that pill, but in my neighborhood that’s required your attitude must be that kind of way. (James, 23 years) |

|

Perceived

strategies which would have prevented abuse experience |

So I’ll just listen and maybe if I would’ve spoken up it wouldn’t have got that far. I feel as though sometimes it was my fault. I feel like if I would’ve said like, “Look, I am not taking this off of you.” (Ann, 39 years) Maybe I could’ve called the police. No, that would’ve made it worse. No, I don’t think there was anything I could’ve done. He needed to seek help for himself because I couldn’t have stopped that. That was on him. (Cynthia, 54 years) |

Strategies to

prevent abusive behaviors |

I learned a lot to [the] point where communication is key. Even if I ignore my partner and I don’t have nothing nice to say to her negative remarks. If I ignore her I’m still wrong but nonetheless I need to hear her. (Edward, 41 years) |

|

Childhood

abuse experiences |

… and pulled me by the back of my head, and pulled down my pants, and he just started touching me, up and down, with his … , and up and down on my behind. And um he was like, “Don’t you yell. Don’t you scream ….” (Ann, 39 years) |

Childhood

abuse experiences |

I never had a childhood. I watch my father beat up my mother … I did not get a chance. I ran away from my father – I switched schools like nine times – never had to go to the prom – none of that. Never made real friends at school – it was time to move on. I really do not have a childhood – my mother was running away from my father most of my childhood, so never had one. (David, 38 years) … Child abuse is crazy, makes you do crazy things, and makes you into a crazy person, if you let it. No matter how old you get or how much you grow up, you will never forget it – at least for me – I don’t. (David, 38 years) |

Triangulation of Qualitative and Quantitative Methods

Items on the instruments were used to design interview questions to ensure semantic consistency. Relatively similar results were found when quantitative and interview data were triangulated. Specifically, the contribution of relationship power on the psychological and physical abuse experiences of female participants, as noted in the quantitative analyses, were significant. Furthermore, similar findings were found with substance and alcohol abuse, childhood abuse, and increased risk for HIV infection from abusive experiences. These results demonstrated that variables and themes were cross-validated by using two data sources and two methodological approaches.

Discussion

The reasons for AA women’s continued disproportionate risks and vulnerabilities to HIV are complex and multifaceted. Contextual factors, such as IPV, further complicate the risks. Better understanding of the interrelationship dynamic between AA women, IPV survivors, and AA male perpetrators are important. The purposes of this study were to: (a) examine and explore the personal, cognitive, and psychosocial factors of IPV among AA women with HIV; (b) explore perceptions of male perpetrators’ roles in contributing to abuse against female partners; and (c) determine the implications of methodological and data source triangulation. This concurrent mixed methods study provided data to increase understanding of this relationship dynamic and make preliminary contributions to nursing science in the areas of HIV and health disparities.

In addition and unique in this study, cross-validation of themes and results when data and methods were triangulated suggested that important target variables could be integrated in large studies and clinical practices. Although some interventions have been designed to address IPV/HIV interrelationships, no HIV study was found that systematically examined AA IPV female survivors and male perpetrators as well as triangulated data sources and methodological approaches as in this study. HIV prevention interventions will most likely be limited and unsustainable if gender inequity and inequality are addressed through the singular lens and perspectives of AA female victims of violence. Therefore, the perspectives of AA male perpetrators who have perpetrated violence are critical to increasing our understanding of HIV prevention in the context of IPV. Further, this study provided greater insight into understanding the IPV relationship dynamic. The preliminary data generated could help inform the design of effective and sustainable dyad and/or community-level HIV/IPV prevention interventions to support AA women.

Compared to AA male participants, more AA women had a high school education. This statistic was consistent with a similar study (Krebs, Breiding, Browne, & Warner, 2011) that reported more than 50% of female participants had obtained a high school education. In spite of this, men in the current study earned higher incomes than the women. Two women reported transactional sex to generate income. Other studies have found that abused women frequently relied on their male partners for financial support, which included trading sex for money (Johnson, Cottler, Ben, & O'Leary, 2011). In some cases, this prevented women from leaving an abusive relationship, exposing them to more violence. Thus, some interventions for abused women have focused on empowering women to gain financial independence; a 55% reduction in IPV was found after 2 years (Dworkin, Dunbar, Krishnan, Hatcher, & Sawires, 2011).

Studies have shown that substance and alcohol use propagates high-risk behaviors and HIV transmission among AA women. The current study found that AA women consistently reported abuse in their relationships, particularly if the AA male partner abused drugs. Women reported that if their partners had not been using, they might have reacted differently. Substance and alcohol abuse play important roles in increasing violence and subsequently placing women at risk for HIV (Maman et al., 2002). Among substance users, Johnson et al. (2011) found that women with a history of sexually transmitted diseases were almost two times more likely to experience sex-related trauma (p = .003). However, the timing of risk in relation to IPV experience and consumption of substances and/or alcohol remains unclear. In the current study, 40% (n = 6) of women and 13.3% (n = 2) of men reported using alcohol and/or drugs with sexual activity. It was difficult to determine their decision-making capabilities.

AA male and female participants in this study reported issues of male dominance and men’s needs to institute control over female partners. Not only did the men believe it was their right to behave in ways that promoted their masculinity but also, and more concerning, was that some women participants reported that this behavior was appropriate. As theoretical and empirical data have suggested, these “consensual ideologies” (Rosenthal & Levy, 2010; p. 26) may be attributed to societal gender norms that dictate what constitutes male/female relationships, which could further increase power imbalances and subsequent abuse against women (Rosenthal & Levy, 2010; Tilley & Brackley, 2005). Male support is needed in some contexts for effective and sustainable HIV/IPV prevention interventions for AAs. In a study that included Latinas, the authors found that women who reported a strong relationship power had a higher negotiating power, used condoms more often, and reported low to no sexual abuse experiences (Randolph, Gamble, & Buscemi, 2011). Studies have reported similar findings of male dominance in separate research studies (Purdie & Jacques-Tiura, 2010).

The current study demonstrated that AA female participants who experienced childhood violence of any type (physical, sexual, or psychological) reported risk behaviors such as substance and alcohol use and sexually transmitted infections in adulthood. Additionally, women reporting abuse as children had abusive partners, and men who were abused as children were perpetrators as adults (Panchanadeswaran et al., 2010; Wyatt et al., 2011).

Four AA women in this study reported acquiring HIV from intimate partners. One reported that she was diagnosed with HIV after her husband died of AIDS. Similar results were found in a study in the United States among male perpetrators of violence in which 53% (n = 41) coerced their partners to have sex without condoms (Purdie & Jacques-Tiura, 2010). In U.S.-based studies, women exposed to violence were more likely not to use condoms (Seth, Raiford, Robinson, Wingood, & DiClemente, 2010). These findings underscore the link between abuse, HIV risk factors, and HIV infection.

The Social Beliefs Subscale measured support that participants received from social referents such as their peers, family members, and significant others. Strong social support was positively correlated with psychological abuse in the current study. A possible explanation is that abused AA women were more receptive to seeking support from their social networks even if they failed to disclose their experiences. One of the women reported that after she was abused she failed to inform family members about the abusive partner. Another important finding in this study was the women’s hesitation to access health care services when they were injured. Most of the women in this study reported that although the injuries they sustained from the abuse may have required medical care, such as stitches for open wounds, they failed to get treatment because of fear that they would not be taken seriously by health care providers. Additionally, women reported that disclosing abusive relationships to providers might worsen their situations. Other researchers have found that abused women failed to access health care because of fear, which later led to more serious physical and psychological illnesses (Campbell et al., 2002). In another report, Zarif (2011) found that women felt their health care providers only attended to their physical injuries and failed to provide safety resources that would facilitate leaving the perpetrator. Women may be in dire need of health care and support, yet unable to gain access to these services. Abused women have also demonstrated deterioration in immunologic markers such as reduced CD4+ T cell counts and increased viral loads (Trimble, Nava, & McFarlane, 2013), which could result in life threatening conditions such as opportunistic infections and antiretroviral drug resistance, thus reducing quality of life.

Participants were asked to provide strategies that could have prevented the abuse. Both AA female and male participants provided suggestions to prevent abuse, such as anger management and more effective communication skills. Male participants acknowledged abusive behaviors and suggested preventive measures, such as controlling anger and effectively managing conflict. Such findings could be integrated as target areas for HIV/IPV prevention interventions. The importance of including men in HIV and IPV prevention interventions is evolving in the literature. Dworkin et al. (2011) suggested that although gender-focused interventions such as “Stepping Stones” and interventions for microfinance and gender equity (IMAGE) have been implemented with some effect, they were unsustainable and in some cases led to more violence against women.

Limitations

Although some limitations were identified, such as small sample size for the quantitative component, this study provides important preliminary information. The study may lack power to report statistically reliable findings; however, the findings from the descriptive and correlational analyses have significant clinical practice implications and warrant investigation in a larger study. The self-report instruments may present another limitation. In addition, the investigator did not have access to the male participants’ medical records and could not validate HIV status. The investigator did find that when women participants were asked about their CD4+ T cell counts, responses were similar to information in their medical records. Furthermore, interviewing females and their partners as a dyad may have provided a stronger methodological approach, but concerns for the women’s safety precluded undertaking such a design in this study.

Implications for Future Research and Practice

The current study contributes preliminary data to increase understanding of the IPV relationship dynamic and HIV. However, additional research studies identifying contextual and structural causal pathways are needed to clarify critical factors that substantially contribute to HIV infection in the context of IPV. Key factors reported when data sources and methodological approaches were triangulated were also important. With these data, future research can focus on feasibility studies integrating the findings from this study in an HIV/IPV prevention intervention dyad or community-level study. AA female participants reported their hesitancy to access medical care and treatment as a result of negative experiences with health care providers. This finding shows the need to educate health care workers about effective approaches to care for women survivors of violence. Comprehensive health care services that not only focus on women’s physical trauma, but their psychological and sexual trauma as well, are critically needed (Aaron et al., 2013).

Key Considerations.

Interpersonal violence and HIV prevention interventions for women must be designed to specifically address women’s unique needs.

Effective communication and relationship dynamic strategies should be included when providing care for women who have experienced abuse.

Gender-based content should be integrated into all HIV prevention interventions as a routine measure to help curb HIV transmission.

There is a dire need for comprehensive health care services that focus on women’s physical, psychological, and sexual traumas.

Acknowledgments

Funding Source: This research was supported by a pilot grant from the Hopkins Center for Health Disparities Solutions of the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health, a Center of Excellence in Minority Health and Health Disparities supported by grant # P60MD000214 from the National Center on Minority Health and Health Disparities of the National Institutes of Health.

The author would like to thank the following from the Johns Hopkins University School of Nursing: Her mentor, Dr. Nancy Glass, Associate Professor, for her support and guidance during the planning, IRB, and data collection processes, and for reviewing the final draft; and to the graduate research assistants, Tiffany J. Riser and Sara S. Koslosky for helping with data collection and preliminary data analyses. The author would also like to thank Dr. Paula Klemm, Professor and Assistant Director for Research and Development at the University of Delaware School of Nursing for reviewing the paper. Special thanks to Ms. Amanda Wozniak, Writer and Editor at the University of Maryland School of Nursing who reviewed the final draft. The author extends her heartfelt gratitude to the study participants, who took the time and agreed to be interviewed. Their participation made this study possible.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The author reports no real or perceived vested interests that relate to this article that could be construed as a conflict of interest.

References

- Aaron E, Criniti S, Bonacquisti A, Geller P. Providing sensitive care for adult HIV-infected women with a history of childhood sexual abuse. Journal of the Association of Nurses in AIDS Care. 2013;24(4):355–367. doi: 10.1016/j.jana.2013.03.004. doi:10.1016/j.jana.2013.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baltimore City Baltimore City HIV/AIDS statistics fact sheet. 2008 Retrieved from http://www.airshome.org/download/factsheet_baltimore.pdf.

- Bent-Goodley TB. Health disparities and violence against women: Why and how cultural and societal influences matter. Trauma, Violence, and Abuse. 2007;8(2):90–104. doi: 10.1177/1524838007301160. doi:10.1177/1524838007301160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell JC, Baty ML, Ghandour RM, Stockman JK, Francisco L, Wagman J. The intersection of intimate partner violence against women and HIV/AIDS: A review. International Journal of Injury Control and Safety Promotion. 2008;15(4):221–231. doi: 10.1080/17457300802423224. doi:10.1080/17457300802423224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell J, Jones AS, Dienemann J, Kub J, Schollenberger J, O'Campo P, Wynne C. Intimate partner violence and physical health consequences. Archives of Internal Medicine. 2002;162(10):1157–1163. doi: 10.1001/archinte.162.10.1157. doi:10.1001/archinte.162.10.1157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Definition of intimate partner violence. 2009 Retrieved from http://www.cdc.gov/violenceprevention/intimate partner violence/index.html.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention HIV and African Americans. 2010 Retrieved from http://www.cdc.gov/hiv/risk/racialethnic/aa/index.html.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention World report on violence and health: Sexual violence. 2011 Retrieved from http://www.who.int/violence_injury_prevention/violence/global_campaign/en/chap6.pdfviolence/index.html.

- Creswell J, Tashakkori A. Developing publishable mixed methods manuscripts. Journal of Mixed Methods Research. 2007;1(2):107–111. doi:10.1177/1558689806298644. [Google Scholar]

- Dowling M, Cooney A. Research approaches related to phenomenology: Negotiating a complex landscape. Nurse Researcher. 2012;20(2):21–27. doi: 10.7748/nr2012.11.20.2.21.c9440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dworkin S, Dunbar M, Krishnan S, Hatcher A, Sawires S. Uncovering tensions and capitalizing on synergies in HIV and antiviolence programs. American Journal of Public Health. 2011;101(6):995–1003. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2009.191106. doi:10.2105/AJPH.2009.191106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- El-Bassel N, Gilbert L, Wu E, Go H, Hill J. HIV and intimate partner violence among methadone-maintained women in New York City. Social Science Medicine. 2005;61(1):171–183. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2004.11.035. doi:10.1016/j.socscimed.2004.11.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fishbein M. The role of theory in HIV prevention. AIDS Care. 2000;12(3):273–278. doi: 10.1080/09540120050042918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerbert B, Bronstone A, McPhee S, Pantilat S, Allerton M. Development and testing of an HIV-risk screening instrument for use in health care settings. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 1998;15(103):103–113. doi: 10.1016/s0749-3797(98)00025-7. doi:10.1016/S0749-3797(98)00025-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gielen AC, Ghandour RM, Burke JG, Mahoney P, McDonnell KA, O'Campo P. HIV/AIDS and intimate partner violence: Intersecting women's health issues in the United States. Trauma Violence Abuse. 2007;8(2):178–198. doi: 10.1177/1524838007301476. doi:10.1177/1524838007301476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanna KM. An adolescent and young adult condom self-efficacy scale. Journal of Pediatric Nursing. 1999;14(1):59–66. doi: 10.1016/S0882-5963(99)80061-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harlow L. Young adult life expectancy survey. 1989. Unpublished manuscript.

- Johnson SD, Cottler LB, Ben AA, O'Leary CC. History of sexual trauma and recent HIV-risk behaviors of community-recruited substance using women. AIDS and Behavior. 2011;15(1):172–178. doi: 10.1007/s10461-010-9752-6. doi:10.1007/s10461-010-9752-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krebs C, Breiding M, Browne A, Warner T. The association between different types of intimate partner violence experienced by women. Journal of Family Violence. 2011;26:487–500. doi:10.1007/s10896-011-9383-3. [Google Scholar]

- Langford DR. Developing a safety protocol in qualitative research involving battered women. Qualitative Health Research. 2000;10(1):133–142. doi: 10.1177/104973200129118192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lichtenstein B. Domestic violence in barriers to health care for HIV-positive women. AIDS Patient Care and STDS. 2006;20(2):122–132. doi: 10.1089/apc.2006.20.122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maman S, Mbwambo JK, Hogan NM, Kilonzo GP, Campbell JC, Weiss L, Sweat MD. HIV-positive women report more lifetime partner violence: Findings from a voluntary counselling and testing clinic in Dar es Salaam, Tanzania. American Journal of Public Health. 2002;92(8):1331–1337. doi: 10.2105/ajph.92.8.1331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maryland Department of Health and Mental Hygiene Baltimore City HIV/AIDS Epidemiological Profile. 2008 Retrieved from http://phpa.dhmh.maryland.gov/OIDEOR/CHSE/Shared%20Documents/Baltimore%20City%20HIV%20AIDS%20Epidemiological%20Profile%2012-2011.pdf.

- Mattson S, Ruiz E. Intimate partner violence in the Latino community and its effects on children. Health Care for Women International. 2005;26(6):523–529. doi: 10.1080/07399330590962627. doi:10.1080/07399330590962627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Melendez RM, Hoffman S, Exner T, Leu CS, Ehrhardt AA. Intimate partner violence and safer sex negotiation: effects of a gender-specific intervention. Archives of Sexual Behavior. 2003;32(6):499–511. doi: 10.1023/a:1026081309709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Njie-Carr VP, Sharps P, Campbell D, Callwood G. Experiences of HIV positive childbearing women: A qualitative study. Journal of the National Black Nurses Association. 2012;23(1):21–28. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Njie-Carr VP. The HIV/AIDS Knowledge, Attitudes, and Beliefs Patient Questionnaire (HAKABQ) The Catholic University of America; Washington, DC: 2005. Unpublished manuscript. [Google Scholar]

- O'Cathain A, Murphy E, Nicholl J. Integration and publications as indicators of "yield" from mixed methods studies. Journal of Mixed Methods Research. 2007;1(2):147–163. [Google Scholar]

- Panchanadeswaran S, Frye V, Nandi V, Galea S, Vlahov D, Ompad D. Intimate partner violence and consistent condom use among drug-using heterosexual women in New York City. Women's Health. 2010;50(2):107–124. doi: 10.1080/03630241003705151. doi:10.1080/03630241003705151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pulerwitz J, Gortmaker SL, DeJong W. Measuring sexual relationship power in HIV/STD research. Sex Roles. 2000;42(7/8):637–660. [Google Scholar]

- Purdie MP, Jacques-Tiura AJ. Perpetrators of intimate partner sexual violence: Are there unique characteristics associated with making partners have sex without a condom? Violence Against.Women. 2010;16(10):1086–1097. doi: 10.1177/1077801210382859. doi:10.1177/1077801210382859. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Randolph M, Gamble H, Buscemi J. The influence of trauma history and relationship power on Latinas' sexual risk for HIV/STI. International Journal of Sexual Health. 2011;23:111–119. doi: 10.1080/19317611.2011.566306. doi:10.1080/19317611.2011.566306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenthal L, Levy S. Understanding women's risk for HIV infection using social and dominance theory and the four bases of gendered power. Psychology of Women Quarterly. 2010;34:21–35. [Google Scholar]

- Sandelowski M. Combining qualitative and quantitative sampling, data collection, and analysis techniques in mixed methods. Research in Nursing & Health. 2000;23:246–255. doi: 10.1002/1098-240x(200006)23:3<246::aid-nur9>3.0.co;2-h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sareen J, Pagura J, Grant B. Is intimate partner violence associated with HIV infection among women in the United States? General Hospital Psychiatry. 2009;31:274–278. doi: 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2009.02.004. doi:10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2009.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seth P, Raiford JL, Robinson SL, Wingood GM, DiClemente RJ. Intimate partner violence and other partner-related factors: Correlates of sexually transmissible infections and risky sexual behaviours among young adult African American women. Sex Health. 2010;7(1):25–30. doi: 10.1071/SH08075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shepard MF, Campbell JA. The Abusive Behavior Inventory - a measure of psychological and physical abuse. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 1992;7(3):291–305. [Google Scholar]

- Silverman JG, Decker MR, Saggurti N, Balaiah D, Raj A. Intimate partner violence and HIV infection among married Indian women. Journal of the American Medical Association. 2008;300(6):703–710. doi: 10.1001/jama.300.6.703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tillerson K. Explaining racial disparities in HIV/AIDS incidence among women in the U.S.: A systematic review. Statistics in Medicine. 2008;27(20):4132–4144. doi: 10.1002/sim.3224. doi:10.1002/sim.3224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tilley D, Brackley M. Men who batter intimate partners: A grounded theory study of the development of male violence in intimate partner relationships. Issues in Mental Health Nursing. 2005;26:281–297. doi: 10.1080/01612840590915676. doi:10.1080/01612840590915676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trimble D, Nava A, McFarlane F. Intimate partner violence and antiretroviral adherence among women receiving care in an urban Southeastern Texas HIV clinic. Journal of the Association of Nurses in AIDS Care. 2013;24(4):331–340. doi: 10.1016/j.jana.2013.02.006. doi:10.1016/j.jana.2013.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wingood GM, DiClemente RJ. Application of the theory of gender and power to examine HIV-related exposures, risk factors, and effective interventions for women. Health Education & Behavior. 2000;27(5):539–565. doi: 10.1177/109019810002700502. doi:10.1177/109019810002700502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wyatt GE, Hamilton A, Myers HF, Ullman J, Chin D, Sumner L, Liu H. Violence prevention among HIV positive women with histories of violence: Healing women in their communities. Women's Health Issues. 2011;21(6S):S255–S260. doi: 10.1016/j.whi.2011.07.007. doi:10.1016/j.whi.2011.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zarif M. Feeling shame: Insights on intimate partner violence. Journal of Christian Nursing. 2011;28(1):40–45. doi: 10.1097/cnj.0b013e3181fe3d14. doi:10.1097/CNJ.06013e3181fe3d14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]