Abstract

Background

Risk stratification of ambulatory heart failure (HF) patients has relied upon peak VO2 (pVO2) <14 mL/min/kg. We investigated whether additional clinical variables might further specify risk of death, ventricular assist device (VAD) implantation (INTERMACS<4) or heart transplantation (HTx; Status 1A or 1B) within one-year after HTx evaluation. We hypothesized that right ventricular stroke work index (RVSWI), pulmonary capillary wedge pressure (PCWP) and the Model for End-stage Liver Disease-Albumin score (MELD-A) would be additive prognostic predictors.

Methods

We retrospectively collected data on 151 ambulatory patients undergoing HTx evaluation. Primary outcomes were defined as HTx, LVAD or death within one-year following evaluation.

Results

Our cohort was 54.9±11.1 year-old, 79.1% male, 37.6% with ischemic etiology (LVEF 21±11% and pVO2 12.6±3.5ml/min/kg). Fifty outcomes (33.1%) occurred (27 HTx, 15 VAD, and 8 deaths). Univariate logistic regression showed significant association of RVSWI (mmHg-L/m2) (OR0.47, p=0.036), PCWP (mmHg) (OR2.65, p=0.007), and MELD-A (OR2.73, p=0.006) with one-year events. Stepwise regression showed independent correlation of RVSWI<5 (OR6.70; p<0.01), PCWP>20 (OR5.48; p<0.01), MELD-A>14 (OR3.72; p<0.01) and pVO2<14 (OR3.36; p=0.024) with one-year events. A scoring system was composed with MELD-A>14 and pVO2<14, 1 point each, and PCWP>20 and RVSWI<5, 2 points each. A cutoff at 4 demonstrated a 54% sensitivity and 88% specificity for one-year events.

Conclusions

Ambulatory HF patients have significant one-year event rates. Risk stratification based on exercise performance, left-sided congestion, right ventricular dysfunction and liver congestion allows prediction of one-year prognosis. This study endorses early and timely referral for VAD and/or transplant.

Keywords: heart failure, prognosis, risk stratification

INTRODUCTION

Heart transplantation (HTx) is the only curative treatment for patients with advanced heart failure (HF); however, its use is severely limited due to organ donor shortage and the increasing number of patients on the HTx waiting list (1, 2). Therefore, selection of transplant candidates requires constant reconsideration of objective assessments of mortality risk in patients with advanced HF who have had the benefit of maximal medical, resynchronization and defibrillator therapy. There have been several validated risk stratification models predicting prognosis of ambulatory patients with HF, such as the Heart Failure Survival Score (HFSS) and the Seattle Heart Failure Model (SHFM) (3, 4). Peak oxygen consumption (peak VO2) has been consistently used to guide optimal timing of listing for HTx in ambulatory patients who are on optimal medical therapy (5-7). A peak VO2 less than 12-14 ml/kg/min has been reported to be an independent predictor for 1-year mortality and is widely used as a cutoff for HTx listing even in the era of β blocker therapy (5-9). However, it has been recognized that peripheral mechanisms, including micro-vascular and/or skeletal muscle function, also contribute to exercise incapacity in patients with HF (10, 11). Further, there have been no risk-stratification models applied for HTx evaluation which combined the factors indicating severity of pulmonary congestion, right ventricular (RV) failure and liver dysfunction in ambulatory patients, although these factors are always considered by clinicians when they estimate when advanced therapies may be indicated. In our present study, we sought to determine whether measurement of pulmonary congestion, RV dysfunction and impaired liver function could strengthen the risk-stratification power of peak VO2 to further identify ambulatory referred patients whom should be listed quickly and also evaluated for device therapy.

METHODS

Study design

A total of 151 stage C/D, NYHA class III ambulatory HF patients presenting to our institution for HTx evaluation between February 2007 and May 2010 were retrospectively analyzed. Patients were included if they were able to perform an exercise test and whom underwent trans-thoracic echocardiogram, right heart catheterization and laboratory testing within a time frame of 30 days. In addition, all patients were on maximal medical therapy and resynchronization therapy and/or a defibrillator, if appropriate, prior to initiation of the HTx evaluation. Patients with inotropic support or on renal replacement therapy were excluded. Patients with a peak VO2 of 18 ml/kg/min or higher were not included in the study to increase homogeneity of the patient cohort and to screen out NYHA Class II subjects. Date of right heart catheterization was considered the entry time point of observation. Our primary outcome was a significant cardiac event; HTX as United Network of Organ Sharing (UNOS) status 1A or 1B, implantation of mechanical circulatory support at the Interagency Registry for Mechanically Assisted Circulatory Support (INTERMACS) level of 4 or higher, or death, within the first year of their initial evaluation.

Our data collection protocol was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Columbia University. The protocol complied with the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act and all ethical guidelines outlined by the 1975 Declaration of Helsinki.

Data acquisitions

All subjects underwent symptom-limited exercise testing on a bicycle or treadmill. Exercise protocol using the bicycle consisted of a 3-minute rest period followed by 3-minute stages starting at 0 watts and increasing by 25 watts every stage until test termination. Treadmill tests used either a modified Bruce or modified Naughton protocol. Ventilatory oxygen uptake was measured and gas exchange data were acquired by breath-by-breath analysis. The peak VO2 was defined as the highest value of oxygen uptake attained in the final 20 seconds of exercise. A 12-lead electrocardiogram was monitored continuously and recorded every minute. All subjects were encouraged to provide a maximal effort, as verbal feedback was given to continue exercising until anaerobic threshold had been reached, as defined by a respiratory exchange ratio > 1 (12). The VE/VCO2 slope was calculated as the slope of the regression line relating VE to VCO2 during exercise.

Echocardiograms were performed using the Sonos-5500® or Sonos-7500® machines (Philips Healthcare Corp, Andover, MA, USA). Conventional echocardiographic parameters were obtained, and the LV ejection fraction (LVEF) was calculated by biplane Simpson’s method. Because of the retrospective nature of the study, we could not obtain quantitative echocardiographic parameters of right ventricular (RV) function from all patients. Therefore, we used the qualitative assessments of RV dysfunction shown in our institutional echo reports, which we classified into normal (RV dysfunction=0), mildly decreased (RV dysfunction=1), moderately decreased (RV dysfunction=2) and severely decreased RV function (RV dysfunction=3).

Right heart catheterization was performed using a 7F triple-lumen Swan-Ganz catheter (Baxter Healthcare, Deerfield, IL, USA) with the patient in the supine position. Pulmonary vascular resistance (PVR) was calculated as: PVR (Woods units) = [mean pulmonary artery pressure (mean PA) − mean right arterial pressure (mean RA)] / cardiac output. Transpulmonary gradient was calculated as: TPG (mmHg) = mean PA −pulmonary capillary wedge pressure (PCWP in mmHg). The RV stroke work index (RVSWI in mmHg-L/m2) was calculated by the following equation: RVSWI (mmHg-L/m2) = (mean PA− mean RA) * stroke volume index*0.0136.

As an indicator of the severity of liver dysfunction, we calculated the Model for End-Stage Liver Disease-with Albumin level (MELD-A). We utilized MELD-A in the present study rather than conventional MELD score to exclude the impact of oral anti-coagulation on international normalized ratio (INR) by replacing INR with albumin levels (13). This modification is identical to the standard score to assess liver dysfunction, except for substitution of the INR component with albumin (13, 14). MELD-A is calculated by the following equation: MELD-A = 3.78 (Ln serum bilirubin, mg/dL) + 11.2[Ln (1+(4.1-albumin, mg/dL))] + 9.57(Ln serum creatinine, mg/dL) + 6.43. Any variable with a value less than one is assigned a value of one. Albumin is capped at 4.1 to avoid negative scores; thus, the minimum possible MELD-A score is 6.43.

Comparison of our risk model with Heart Failure Survival Score (HFSS)

In order to compare the power of the risk-stratification model derived from our analysis, we also evaluated whether the Heart Failure Survival Score (HFSS) was predictive in multi-variate analysis, with peak VO2 not added to the regression model, as it is included in the HFSS. The HFSS is calculated as the absolute value of the sum of the products of the prognostic components, which are (i) presence or absence of coronary artery disease (ii) resting heart rate (iii) mean arterial blood pressure (iv) left ventricular ejection fraction (v) presence or absence of interventricular conduction defect (biventricular pacing constitutes presence of) (vi) peak VO2 and (vii) serum sodium. Categorical variables were graded as 1 if present or 0 if absent. Low-risk patients are identified as those with a score >8.1; medium- and high-risk patients have risk scores <8.1(3).

Statistical analysis

All data were analyzed using the Statistical Analysis Systems software JMP 7.0 (SAS Institute Inc. Cary, NC, USA). Continuous variables are presented as a mean±standard deviation, while categorical and binary data are presented as counts and frequency distributions. Comparison of continuous variables relied upon two-tailed, unpaired Student’s t-tests or Analysis of Variance, while categorical data was compared through chi-squared testing or Fischer’s exact tests for low frequency outcomes. All analysis assumed a p value <0.05 as significant.

Correlation of significant cardiac events within the first year to predictive values relied upon univariate and multivariate logistic regression. Significant univariate values were dichotomized at clinically relevant and statistically significant cutoffs derived from receiver operator characteristic (ROC) curve before inclusion in stepwise backward logistic regression to arrive at our final model of independent predictors. Score creation was based upon the relative coefficients of each covariate. A cutoff value was chosen with the highest correct classification and specificity through ROC curve analysis. Using the cutoff value of our scoring system, the event-free ratio of patients with a higher cut-off value and those with a lower cut-off value was compared using Kaplan-Meier methods with log-rank test.

We then substituted the HFSS for peak VO2 in our final logistic model to validate the independence of each predictive covariate.

RESULTS

Baseline characteristics and patients outcome within a year after evaluation

Clinical characteristics of all studied patients are summarized in Table 1. The mean age of patients was 55 year-old, 79% male, 39% patients with ischemic heart disease. We were able to obtain detailed information about medications from 90 % of patients and from 100% regarding device therapy. Among those, 93% patients were on β-blocker therapy and 57% patients received cardiac resynchronization therapy. Mean peak VO2 at the time of HTx evaluation was 12.5 ml/kg/min, and the mean LVEF was 21%. More than 70% of patients had some degree of RV dysfunction by echocardiogram. The mean HFSS of our cohort was 7.95 (median-high risk).

Table 1.

Clinical characteristics of patients at the time of transplant evaluation

| Total Number of patients | n=151 |

|---|---|

| Clinical Characteristics | |

|

| |

| Age (year-old) | 55.0±11.0 |

| Male (n, %) | 119 (78.8%) |

| Body mass index (kg/m2) | 27.5±5.3 |

| Ischemic etiology (n, %) | 59 (39%) |

|

| |

| Diabetes Mellitus (n, %) | 15 (9.9%) |

|

| |

| Medications (n, %) * n=136 | |

|

| |

| ACEI/ARB or Isosrbide dinitrate/Hydralazine | 97 (71.3%) |

|

| |

| β-blockers | 126 (92.6%) |

|

| |

| Aldosterone antagonist | 84 (61.8%) |

|

| |

| Pacing Devices (n, %) | |

|

| |

| AICD | 99 (65.6%) |

|

| |

| CRT | 86 (57.0%) |

|

| |

| Hemodynamic Data | |

|

| |

| Mean RA (mmHg) | 9.7±6.2 |

|

| |

| Mean PA (mmHg) | 29.9±10.6 |

|

| |

| PCWP (mmHg) | 20.2±9.2 |

| TPG (mmHg) | 9.9±5.9 |

| PVR (wood) | 3.3±2.2 |

| Cardiac index (L/min/m2) | 1.7±0.5 |

| Mixed venous oxygen saturation (%) | 57.8±9.0 |

| RVSWI (g·m2/beat) | 6.9±4.0 |

|

| |

| Cardiopulmonary Exercise Test | |

| Peak VO2 (mL/min/kg) | 12.5±3.5 |

| VE/VCO2 | 37.3±9.6 |

|

| |

| Echo Data | |

|

| |

| LV end-diastolic dimension (mm) | 67.2±12.0 |

| LV Ejection Fraction (%) | 21.1±10.8 |

| RV function (n, %) | |

|

| |

| Normal | 36 (27.9%) |

|

| |

| Mildly decreased | 24 (18.6%) |

|

| |

| Moderately deceased | 46 (35.7%) |

|

| |

| Severely decreased | 23 (17.8%) |

|

| |

| Laboratory Examinations | |

|

| |

| AST (U/L) | 26.7±13.9 |

| ALT (U/L) | 28.5±20.3 |

| Total Bilirubin (mg/dL) | 1.10±0.71 |

| Na (mEq/L) | 137.5±3.3 |

| BUN (mg/dL) | 28.7±149 |

| Creatinine (mg/dL) | 1.5±1.2 |

| MELD-A | 12.7±4.5 |

|

| |

| HFSS | 7.95±0.82 |

Abbreviations not defined in text: ACEI, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor; ARB, Angiotensin II receptor blocker; AICD, automatic implantable cardioverter defibrillator; CRT, cardiac resynchronization therapy; Na, sodium; BUN, blood urea nitrogen.

We could not obtain medication information on 15 patients (10%of cohort).

Among 151 patients, 27 patients (18%) required HTx as UNOS status 1A or 1B, 15 patients (9.9%) required mechanical circulatory support as INTERMACS <4 (14), and 8 patients (5.3%) died within one year following HTx evaluation. Therefore, a total of 50 patients (33.1%) reached the endpoint of a one-year event.

Factors associated with one-year event after HTx evaluation

The results of the association of factors with one-year events are shown in Table 2. As continuous variables, higher PCWP, higher mean RA pressure, lower mixed venous oxygen saturation, lower RVSWI, higher VE/VCO2 ratio, and higher MELD-A score were found to be significantly associated with one-year events following HTx evaluation. Lower peak VO2 showed a tendency of association with one-year events. Lower HFSS was also associated with one-year event. As a categorical value, moderate-severe RV dysfunction on echocardiogram was also associated with one-year events. The cutoff value of those variables to discriminate patients who developed any event within one-year from those who did not were calculated by ROC curve, and the values are also shown in Table 2. Among those variables, PCWP, RVSWI, peak VO2 and MELD-A were included into the subsequent multivariate logistic regression analysis. Peak VO2 was not statistically associated with one-year events by univariate analysis, but VE/VCO2 was; however, we include peak VO2 instead of VE/VCO2 in the present study because it has been more generally and traditionally used to evaluate HTx candidacy than VE/VCO2. We did not include RV dysfunction on echocardiogram, because the RV functional assessment in this study was not quantitatively performed.

Table 2.

Univariate analysis of factors associated with an event within one year following evaluation

| Variables | OR | 95%CI | p-value | Cutoff |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 0.9786 | 0.9492-1.0089 | 0.165 | |

| Gender (Male=1, Female=0) | 0.8761 | 0.3900-1.9682 | 0.749 | |

| Mean PA (mmHg) | 1.8733 | 0.9302-3.7725 | 0.079 | |

| PCWP (mmHg) | 2.6500 | 1.3024-5.3921 | 0.007 | 20 |

| Mean RA (mmHg) | 4.2424 | 1.8663-9.6438 | 0.001 | 14 |

| TPG (mmHg) | 0.8358 | 0.4253-1.6438 | 0.603 | |

| PVR (wood) | 1.4376 | 0.7285-2.8371 | 0.295 | |

| Mixed venous oxygen saturation (%) | 0.2811 | 0.1225-0.6450 | 0.003 | 50 |

| RVSWI (g·m2/beat) | 0.4701 | 0.2323-0.9514 | 0.036 | 5 |

| Peak VO2 (mL/min/kg) | 0.4462 | 0.1916-1.0392 | 0.061 | 14 |

| VE/VCO2 | 3.6401 | 1.3558-9.7731 | 0.010 | 34 |

| RV dysfunction on echocardiogram* | 2.3821 | 1.1076-5.1231 | 0.026 | 2 |

| MELD-A | 2.7283 | 1.3391-5.5592 | 0.006 | 14 |

| HFSS | 0.893 | 0.7821-0.9820 | 0.007 | 8.1 |

According to the institutional echo report, normal RV function is graded as 0, mildly decreased as 1, moderately decreased as 2, and severely decreased as 3.

Abbreviations not defined in text: OR, odds ratio; CI, confidence interval.

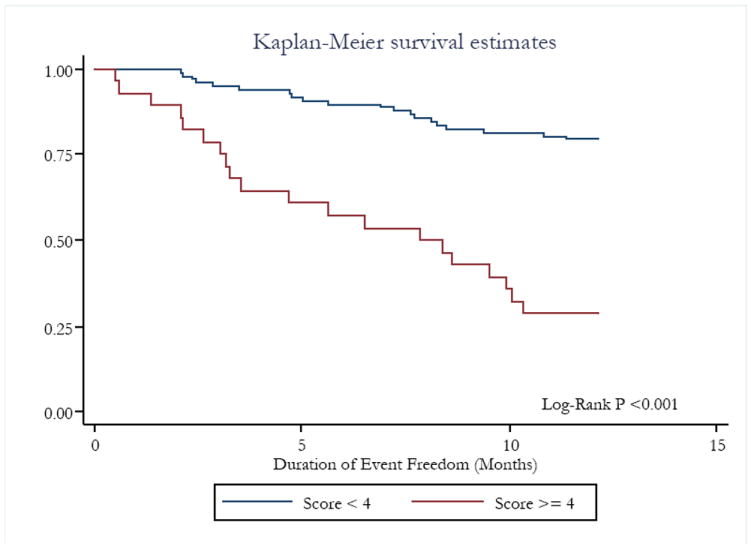

Multivariate logistic regression analysis using the cutoff value of each variable to dichotomize patients with and without risk for one-year events (peak VO2<14 ml/kg/min, MELD-A>14, PCWP>20 mmHg, and RVSWI< 5 mmHg-L/m2) revealed that all included variables were significantly associated with one-year events (Table 3-A). Considering the relative coefficients of each covariate, the peak VO2 and MELD-A were each weighted with one point, while PCWP and RVSWI were both weighted with two points to create a risk-stratification model (Table 4). The ROC curve analysis using this model showed that the cutoff of point of 4 yielded a sensitivity of 53.7%, a specificity of 88.2% and a highest predictive accuracy of 77.0% for association with one-year events following HTx evaluation (Table 4). The event-free rate from the time of HTx evaluation of patients with score ≥4 and those <4 is shown in Figure 1. When we used VE/VCO2 >34 in the risk model instead of peak VO2 (VE/VCO2 >34, MELD-A>14, PCWP>20 mmHg, and RVSWI< 5 mmHg-L/m2), the cutoff point of 4 yield a sensitivity of 39.6% and a specificity of 89.8%, and a predictive accuracy of 71.2%. In addition, when we use peak VO2<12 ml/kg/min instead of <14 ml/kg/min, the cutoff point of 3 yielded a sensitivity of 73.6% and specificity of 61.2%, with a predictive accuracy of 65.1%. Therefore, our risk-stratification model using peak VO2<14 ml/kg/min, MELD-A>14, PCWP>20 mmHg, and RVSWI< 5 mmHg-L/m2 yielded the highest predictive accuracy.

Table 3.

A. Multivariate logistic regression analysis of factors associated with an event within one year following evaluation

| Parameters | OR | 95%CI | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| PCWP > 20mmHg | 5.4824 | 1.9856-15.1364 | 0.001 |

| RVSWI <5 mmHg-L/m2 | 6.7020 | 2.3221-19.3437 | <0.0001 |

| MELD-A >14 | 3.7224 | 1.4802-9.3605 | 0.005 |

| Peak VO2 <14 mL/min/kg | 3.3553 | 1.1722-9.6047 | 0.024 |

|

| |||

|

B. Multivariate logistic regression analysis of factors associated with an event within one year following evaluation by replacing peak VO2 with HFSS

| |||

| Parameters | OR | 95%CI | p-value |

|

| |||

| PCWP > 20mmHg | 2.830 | 1.1247-7.1234 | 0.027 |

| RVSWI <5 mmHg-L/m2 | 5.6937 | 1.9774-16.3942 | 0.001 |

| MELD-A >14 | 5.8264 | 2.0400-16.6410 | 0.001 |

| HFSS<8.1 | 2.7622 | 1.0880-7.0123 | 0.033 |

Abbreviations not defined in text: OR, odds ratio; CI, confidence interval.

Table 4.

The point of each co-variable for risk scoring model and the association with one-year event following evaluation

| Variables | Cutoff value | Points |

|---|---|---|

| Peak VO2 (mL/min/kg) | <14 | 1 |

| MELD-A | >14 | 1 |

| PCWP (mmHg) | >20 | 2 |

| RVSWI (mmHg- L/m2) | <5 | 2 |

| Total points of each patients and association with one-year events following evaluation | ||

| Sensitivity | Specificity | |

| ≥0 | 100.0% | 0.00% |

| ≥1 | 100.0% | 10.6% |

| ≥2 | 97.6% | 24.7% |

| ≥3 | 82.9% | 52.9% |

| ≥4 | 53.7% | 88.2% |

| ≥5 | 29.3% | 97.7% |

| ≥6 | 17.1% | 98.8% |

Figure 1. Kaplan-Meier curves of patients undergoing HTx evaluation with our risk-stratification model score ≥4 and <4.

The end-point was set as death/HTx as Status 1A o 1B /mechanical circulatory support requirement as INTERMACS Level < 4.

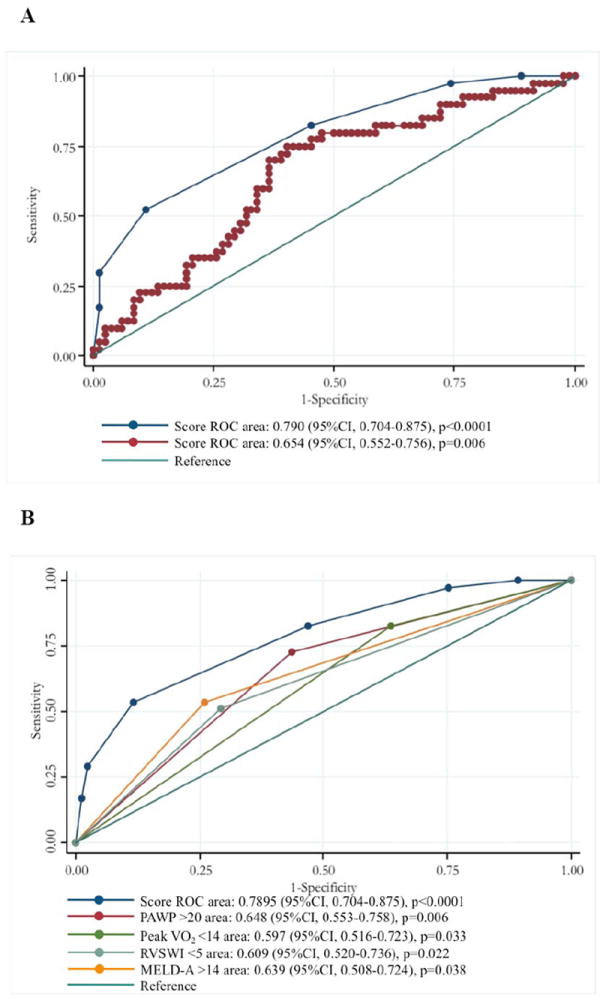

When we substituted the HFSS for peak VO2 in our multivariate logistic model to validate the independence of each covariate, each remained as independently associated factors (Table 3-B). The association of our score based on peak VO2, RVSWI, MELD-A and PCWP, or using the HFSS (using a cutoff value of 8.1) and dropping peak VO2, with one-year event was evaluated (Table 5). Both scores showed a significant association with one-year event following HTx evaluation; however, the odds ratio was higher and the p value was smaller in our original score model (using peak VO2 instead of HFSS). The area under the curves of ROC analysis for our original risk-stratification model, or with HFSS substitution, were 0.7895 and 0.6540, respectively (Figure 2A). Further, the area under the curves of ROC analysis for our risk-stratification model was higher than any other single variable included in our risk-stratification model (Figure 2B).

Table 5.

Risk-stratification model and its association with one-year events following HTx evaluation

| Risk stratification model | OR | 95%CI | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Our score (≥4) * | 9.3953 | 3.3954-25.9970 | <0.001 |

| HFSS (≤8.1) | 2.9771 | 1.1862-7.4722 | 0.020 |

Patient with peak VO2<14 mL/min/kg receive 1 point, MELD-A>14 receive 1 point, RVSWI<5 mmHg-L/m2 receive 2 points and PCWP>20 mmHg receive 2 points.

Abbreviations not defined in text: OR, odds ratio; CI, confidence interval.

Figure 2. Receiver operating characteristic curves for our risk-stratification model and HFSS (A) and co-variable included in our risk-stratification model (B) associated with death/HTx/mechanical circulatory support requirement within one-year after HTx evaluation.

Blue line indicates the ROC curve of our risk-stratification model, and red line indicates HFSS.

DISCUSSION

In the present study, we demonstrate that: (i) ambulatory HF patients have a significant one-year event rate of 33%, including death, transplant as a UNOS Status 1A or 1B or mechanical circulatory support; (ii) the information regarding pulmonary congestion, RV dysfunction and liver dysfunction, in addition to the peak VO2, could further risk-stratify ambulatory HF patients and (iii) the novel risk-stratification model, which consisted of simple scoring system of peak VO2<14 ml/kg/min=1 point, MELD-A>14=1 point, RVSWI<5 g·m2/beat=2 points and PCWP>20 mmHg=2 points, could sufficiently discriminate patients with high risk for one-year events. In addition, adding the HFSS score to our clinical predictors was comparative to the results demonstrated using the peak VO2.

HF is a progressive disease, and the prevalence of HF is increasing throughout the world with high morbidity and mortality (16). HTx is the only curative treatment for patients with advanced HF but its use is severely limited due to donor shortage (1, 16). Therefore, risk-stratification of ambulatory patients who may acutely deteriorate is critically important. The peak VO2 derived from cardiopulmonary exercise testing has been widely used for selection of HTx candidate; however, it is influenced by multiple factors including lung function, anemia, peripheral circulation and skeletal muscles, and contains limitations when used alone (5, 10, 11). The HFSS, calculated using 7 parameters including peak VO2, has been reported to perform better than peak VO2 alone (7, 17-19). The SHFM provides an estimation of 1-, 2-, and 5-year survival rate using 20 variables of clinical, pharmacologic, device and laboratory parameters, but it uses NYHA class as a measure of functional capacity, which is a subjective parameter (4, 19).

Both the HFSS and the SHFM are strong predictors for prognosis of HF patients (4, 7, 17-19); however, we believe that our risk-stratification model also includes hemodynamic factors, which informs our ability to treat a patient e.g. manage biventricular rather than left ventricular function. Therefore, we initiated the present study to create a simple risk-stratification model, which include a smaller number of co-variables, and is calculated by adding points derived from a cut-off value of co-variables to dichotomize patients. To our knowledge, our proposal is the first attempt to create a risk-stratification model using both left- and right heart congestion markers, in addition to peak VO2 obtained in ambulatory HF patients.

It has been well known that patients with isolated LV dysfunction, including those with preserved LVEF, portends a poor prognosis (20, 21). RV dysfunction may develop in association with LV dysfunction and portends a worse prognosis compared to LV dysfunction in isolation. (22, 23). Indeed, such patients are difficult to manage, as diuresis and uptitration of oral heart failure medications is often limited by hypotension and worsening renal insufficiency. Low RVSWI is reported to be associated with RV failure after LVAD (24, 25), and may also be used to quantify RV dysfunction as an indicator that HTx should be considered earlier to avoid clinically important congestive hepatopathy and cirrhosis. In our risk-stratification model, we included hemodynamic markers for both left- and right-sided dysfunction; PCWP and RVSWI. Further, we included an indicator of liver dysfunction into our model, which was indeed found to significantly associated with one-year events by the uni- and multivariate logistic regression analysis. Liver dysfunction is known to be associated with increased short- and long-term morbidity and mortality in patients undergoing cardiac and non-cardiac surgery (26-28). The importance of quantifying liver dysfunction using a novel MELD scoring system to predict outcomes after mechanical circulatory support and HTx has been discussed recently (14). The original form of MELD score is a measure of liver dysfunction, providing an objective score based on a patient’s creatinine, total bilirubin, and international normalized ratio (INR) (27, 28); however, it may not be calculated accurately in patients on warfarin. Therefore, we utilized the MELD-A score, which excludes the effects of anti-coagulation by substituting albumin for INR in the study. We recently reported that patients with elevated modified MELD-A prior to HTx showed a poor post-transplant prognosis (12). We also reported that MELD-XI (MELD eXcluding INR), which uses only creatinine and total bilirubin for calculation, developed by Heuman et al (29), was useful to assess a post-operative prognosis of patients undergoing ventricular assist device surgery (30). Importantly, a majority of our patients in this study were on β -blockers. Due to survival benefits of medical therapies, a peak VO2 in the range of 10-14 ml/kg/min has become a more appropriate range at which to consider HTx listing (16, 31). The International Society of Heart and Lung Transplantation guidelines state that a peak VO2<12 ml/kg/min should be the listing criterion in patients on β-blockers (7). However, in our cohort, the risk-stratification model using peak VO2<14 ml/kg/min showed a higher association for one-year events than using <12 mL/min/kg. Further investigation based on larger cohort would be required to determine the cutoff value of peak VO2 in the context of the covariables, and also the role of VE/VCO2 in this model.

Of note, the risk-stratification model proposed in the present study is a simple scoring system based on only 4 co-variables, the area under the curve of our model was greater as compared to using HFSS alone Furthermore, patients with score ≥ 4 on our risk-stratification model would have 3 times higher risk of developing events within a year than those with HFSS≤8.1.

Our study contains several limitations. First, due to the observational and retrospective nature of the study, the timing of pulmonary exercise testing, hemodynamic data the laboratory examination ranged up to 30 days, although the strength of the study was that all the patients were stable enough to undergo exercise tests during the evaluation periods. Importantly, we did not perform a comparison analysis of our risk-stratification model with the SHFM, because the dosage of medications, which were components of the SHFM, could be adjusted during the evaluation periods in some patients. Second, we admit that coexisting morbidities may influence the prognostic model, such as the presence of diabetes mellitus and severe chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD). We did not include Pulmonary Function Test data as an indicator of COPD. However, no patient was excluded from HTx evaluation based on a co-morbidity that was prohibitive for successful HTx. Third, our patients underwent symptom-limited CPET, with the goal of respiratory gas exchange ratio (RER) greater than 1. We admit that some patients could not reach RER > 1 but used their data, as their best effort. Furthermore, we used 2 different exercise protocols; treadmill and bicycle ergometer. The peak VO2 derived from the different exercise protocols may not be comparable, because the exercise capacity of patients with chronic heart failure has known to be greater when assessed by treadmill rather than using ergometer (32). Finally, eligibility/listing criteria for HTx itself, and any institutional changes over the past four years might have influenced results. From this point of view, we should be cautious about the findings. Irrespective of these limitations, we believe that the risk-stratification model proposed here may be of value to clinicians in estimating a patients’ risk for developing critical events sometime in the near future, and to incorporate this risk assessment into earlier HTx listing and/or earlier consideration for mechanical circulatory support device therapy.

In conclusion, we demonstrate that our novel risk-stratification model using cut-off values consisted of peak VO2<14 ml/kg/min, MELD-A>14, PCWP>20mmHg, RVSWI<5g·m2/beat may sufficiently predict one-year prognosis of ambulatory HF patients. This study endorses early and timely referral to programs with expertise in advanced cardiac care.

Acknowledgments

Maryjane Farr MD was supported by the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences, National Institutes of Health, through Grant Number UL1 TR000040, formerly the National Center for Research Resources, Grant Number UL1 RR024156. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH.

Footnotes

None of other authors have anything to disclose.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Stehlik J, Edwards LB, Kucheryavaya AY, et al. The Registry of the International Society for Heart and Lung Transplantation: Twenty-eighth Adult Heart Transplant Report—2011. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2011;30:1078–94. doi: 10.1016/j.healun.2011.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jaski BE, Kim JC, Naftel DC, et al. Cardiac Transplant Research Database Research Group. Cardiac transplant outcome of patients supported on left ventricular assist device vs. intravenous inotropic therapy. J Heart and Lung Transplant. 2001;20:449–56. doi: 10.1016/s1053-2498(00)00246-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Aaronson KD, Schwartz JS, Chen TM, Wong KL, Goin JE, Mancini DM. Development and prospective validation of a clinical index to predict survival in ambulatory patients referred for cardiac transplant evaluation. Circulation. 1997;95:2660–7. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.95.12.2660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Levy WC, Mozaffarian D, Linker DT, et al. The Seattle Heart Failure Model: prediction of survival in heart failure. Circulation. 2006;113:1424–1433. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.584102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mancini DM, Eisen H, Kussmaul W, Mull R, Edmunds LH, Jr, Wilson JR. Value of peak exercise oxygen consumption for optimal timing of cardiac transplantation in ambulatory patients with heart failure. Circulation. 1991;83:778–86. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.83.3.778. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Costanzo MR, Augustine S, Bourge R, et al. Selection and treatment of candidates for heart transplantation. A statement for health professionals from the Committee on Heart Failure and Cardiac Transplantation of the Council on Clinical Cardiology, American Heart Association. Circulation. 1995;92:3593–612. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.92.12.3593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mehra MR, Kobashigawa J, Starling R, et al. Listing criteria for heart transplantation: International Society for Heart and Lung Transplantation guidelines for the care of cardiac transplant candidates--2006. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2006;25:1024–42. doi: 10.1016/j.healun.2006.06.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lund LH, Aaronson KD, Mancini DM. Predicting survival in ambulatory patients with severe heart failure on beta-blocker therapy. Am J Cardiol. 2003;92:1350–4. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2003.08.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Myers J, Gullestad L, Vagelos R, et al. Cardiopulmonary exercise testing and prognosis in severe heart failure: 14 mL/min/kg revisited. Am Heart J. 2000;139:78–84. doi: 10.1016/s0002-8703(00)90312-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Haykowsky MJ, Brubaker PH, Stewart KP, Morgan TM, Eggebeen J, Kitzman DW. Effect of endurance training on the determinants of peak exercise oxygen consumption in elderly patients with stable compensated heart failure and preserved ejection fraction. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2012;60:120–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2012.02.055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Maurer MS, Schulze PC. Exercise intolerance in heart failure with preserved ejection fraction: shifting focus from the heart to peripheral skeletal muscle. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2012;60:129–31. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2012.04.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Maurer M, Burkhoff D, Maybaum S, et al. A multicenter study of noninvasive cardiac output during symptom limited exercise. J Card Fail. 2009;15:689–699. doi: 10.1016/j.cardfail.2009.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chokshi A, Cheema FH, Schaefle KJ, et al. Hepatic dysfunction and survival after orthotopic heart transplantation: application of the MELD scoring system for outcome prediction. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2012;31:591–600. doi: 10.1016/j.healun.2012.02.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Matthews JC, Pagani FD, Haft JW, Koelling TM, Naftel DC, Aaronson KD. Model for end-stage liver disease score predicts left ventricular assist device operative transfusion requirements, morbidity, and mortality. Circulation. 2010;121:214–20. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.108.838656. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kirklin JK, Naftel DC, Kormos RL, et al. The Fourth INTERMACS Annual Report: 4,000 implants and counting. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2012;31:117–26. doi: 10.1016/j.healun.2011.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mancini D, Lietz K. Selection of cardiac transplantation candidates in 2010. Circulation. 2010;122:173–83. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.858076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lund LH, Aaronson KD, Mancini DM. Validation of peak exercise oxygen consumption and the Heart Failure Survival Score for serial risk stratification in advanced heart failure. Am J Cardiol. 2005;95:734–41. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2004.11.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Green P, Lund LH, Mancini D. Comparison of peak exercise oxygen consumption and the Heart Failure Survival Score for predicting prognosis in women versus men. Am J Cardiol. 2007;99:399–403. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2006.08.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Goda A, Williams P, Mancini D, Lund LH. Selecting patients for heart transplantation: comparison of the Heart Failure Survival Score (HFSS) and the Seattle heart failure model (SHFM) J Heart Lung Transplant. 2011;30:1236–43. doi: 10.1016/j.healun.2011.05.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bhatia RS, Tu JV, Lee DS, et al. Outcome of heart failure with preserved ejection fraction in a population-based study. N Engl J Med. 2006;355:260–269. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa051530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bursi F, Weston SA, Redfield MM, et al. Systolic and diastolic heart failure in the community. JAMA. 2006;296:2209–2216. doi: 10.1001/jama.296.18.2209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Voelkel NF, Quaife RA, Leinwand LA, et al. National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute Working Group on Cellular and Molecular Mechanisms of Right Heart Failure. Right ventricular function and failure: report of a National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute working group on cellular and molecular mechanisms of right heart failure. Circulation. 2006;114:1883–91. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.632208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.de Groote P, Millaire A, Foucher-Hossein C, et al. Right ventricular ejection fraction is an independent predictor of survival in patients with moderate heart failure. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1998;32:948–54. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(98)00337-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kato TS, Chokshi A, Singh P, et al. Markers of extracellular matrix turnover and the development of right ventricular failure after ventricular assist device implantation in patients with advanced heart failure. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2012;31:37–45. doi: 10.1016/j.healun.2011.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ochiai Y, McCarthy PM, Smedira NG, et al. Predictors of severe right ventricular failure after implantable left ventricular assist device insertion: analysis of 245 patients. Circulation. 2002;106(12 Suppl 1):I198–202. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kamath PS, Wiesner RH, Malinchoc M, et al. A model to predict survival in patients with end-stage liver disease. Hepatology. 2001;33:464–70. doi: 10.1053/jhep.2001.22172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Malinchoc M, Kamath PS, Gordon FD, et al. A model to predict poor survival in patients undergoing transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunts. Hepatology. 2000;31:864–871. doi: 10.1053/he.2000.5852. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wiesner R, Edwards E, Freeman R, et al. United Network for Organ Sharing Liver Disease Severity Score Committee. Model for end-stage liver disease (MELD) and allocation of donor livers. Gastroenterology. 2003;124:91–6. doi: 10.1053/gast.2003.50016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Heuman DM, et al. MELD-XI: a rational approach to “sickest first” liver transplantation in cirrhotic patients requiring anticoagulant therapy. Liver Transpl. 2007;13:30–7. doi: 10.1002/lt.20906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Yang JA, Kato TS, Shulman BP, et al. Liver dysfunction as a predictor of outcomes in patients with advanced heart failure requiring ventricular assist device support: Use of the Model of End-stage Liver Disease (MELD) and MELD eXcluding INR (MELD-XI) scoring system. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2012;31:601–10. doi: 10.1016/j.healun.2012.02.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Heart Failure Society of America. Lindenfeld J, Albert NM, Boehmer JP, et al. HFSA 2010 Comprehensive Heart Failure Practice Guideline. J Card Fail. 2010 Jun;16:e1–194. doi: 10.1016/j.cardfail.2010.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kim S, Yamabe H, Yokoyama M. Hemodynamic characteristics during treadmill and bicycle exercise in chronic heart failure: mechanism for different responses of peak oxygen uptake. Jpn Circ J. 1999;63:965–70. doi: 10.1253/jcj.63.965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]