Abstract

Does compassion feel pleasant or unpleasant? People tend to categorize compassion as a pleasant or positive emotion, but laboratory compassion inductions, which present another’s suffering, may elicit unpleasant feelings. Across two studies, we examined whether prototypical conceptualizations of compassion (as pleasant) differ from experiences of compassion (as unpleasant). Following laboratory-based neutral or compassion inductions, participants made abstract judgments about compassion relative to various emotion-related adjectives, thereby providing a prototypical conceptualization of compassion. Participants also rated their own affective states, thereby indicating experiences of compassion. Conceptualizations of compassion were pleasant across neutral and compassion inductions. Following exposure to others’ suffering, however, participants felt increased levels of compassion and unpleasant affect, but not pleasant affect. Following neutral inductions, participants reported more pleasant than unpleasant affect, with moderate levels of compassion. Thus, prototypical conceptualizations of compassion are pleasant, but experiences of compassion can feel pleasant or unpleasant. The implications for emotion theory in general are discussed.

Keywords: emotion, subjective experience, multidimensional scaling, affective circumplex, Conceptual Act Theory

In most scientific models of emotion, fear, disgust, and sadness are categorized as unpleasant or “negative” emotions; gratitude, joy, and pride are categorized as pleasant or “positive” emotions. But human experience is more varied. There are times when negative emotions like fear can feel pleasant (e.g., riding a roller coaster), and positive emotions like happiness can feel unpleasant (e.g., after verbalizing a retort at a difficult person). These examples appear to violate traditional understandings of emotion, but they are common in everyday life (Condon, Wilson-Mendenhall, & Barrett, in press). Although labels provide an emotion category with a dedicated valence, these categories appear to contain multiple instances that vary from pleasant to unpleasant.

Compassion is of particular interest as empirical findings leave the question about compassion’s valence unresolved (e.g., Lazarus, 1991). Although scientists and laypeople typically characterize compassion as a positive emotion (Keltner & Lerner, 2010; Shaver, Schwartz, Kirson, & O’Connor, 1987), reports of compassion experiences indicate that compassion can feel unpleasant. Images depicting poverty and vulnerable infants, for example, simultaneously elevated reports of compassion and distress (Simon-Thomas et al., 2012). The valence of compassion appears illusive, but a scientific account depends on a greater understanding of the subjective experience of compassion.

A newer perspective views an emotion’s valence in more nuanced terms. The Conceptual Act Theory defines emotions as situated conceptualizations accompanied by shifts in core affective states (Barrett, 2006; Wilson-Mendenhall, Barrett, Simmons, & Barsalou, 2011). Emotion categories are abstract concepts, much like truth or justice, which integrate sensory information from the world, the body, and conceptual information from past experience to create a single gestalt. Over time, a person experiences various sensations in a situational context and learns to pair them with an emotion word, like “compassion.” As a person encounters and learns different instances of the emotion, instances become stored in memory across modalities, thereby creating variation in the concept. Activating different situated conceptualizations of the emotion in the present moment will result in different feelings, some pleasant and some unpleasant depending on the context.1

Neuroimaging data support the view that affect can vary among instances within an emotion category. When participants immersed themselves in different scenarios to induce feelings of fear, sadness, and happiness that varied in valence (e.g., pleasant fear of riding a roller coaster; unpleasant fear of giving an unprepared speech), brain regions tracked with the valence (orbitofrontal cortex) and arousal (amygdala) of the instance within and across categories (Wilson-Mendenhall, Barrett, & Barsalou, 2013). From this perspective, different instances of compassion might feel pleasant or unpleasant.

Although instances within an emotion category vary in valence, the prototypical conceptualization of the emotion links the category to a dedicated valence. The most well-known organization of emotion categories—within the affective circumplex structured by valence and arousal—is driven by prototypical episodes (Russell & Barrett, 1999). Fear, for example, is prototypically unpleasant and highly arousing. The prototype of compassion appears to be pleasant and low arousal (Shaver et al., 1987). Nevertheless, the prototype of a category like compassion is not the one that is most frequently encountered, but rather the instance that maximally achieves the goal that the category is organized around (Barsalou, 2003). Humans develop categories to guide action and support specific goals. The goal lose weight, for example, is supported by the category foods to eat on a diet (Barsalou, 1985). Instances that maximally support that goal (i.e., foods with less calories) are most typical of the category, even if they are not the most frequently encountered (Barsalou, 1985). We hypothesize that emotion categories are likewise organized around goals, such as escape threat (fear) or reduce suffering (compassion) with specific instances varying in the degree to which they serve such goals. The current studies compared prototypical conceptualizations of compassion to experiences of compassion. We predicted that prototypical conceptualizations would link compassion with pleasant affect, but witnessing another’s suffering would induce an unpleasant compassion experience.

Pilot Study

We conducted a pilot study to assess conceptualizations and experiences of compassion across different emotion inductions. This study involved procedures similar to the main study with minor exceptions.2 Twenty-eight students (19 female; Mage=20.71, SDage=1.44) received $10 and were randomly assigned to a neutral or compassion emotion induction. Following the induction, participants rated the similarity of emotion-related adjectives that sampled all parts of the affective circumplex, thereby providing conceptualizations of various states. Finally, participants rated their own state in reaction to the induction. To test whether the effects of the inductions influence either conceptualizations or experience, we induced emotional states prior to both similarity ratings and state ratings.

Participants in the compassion condition reported feeling more compassion (M=4.14, SD=0.66) than in the neutral condition (M=3.21, SD=1.05), t(26)=2.80, p<.01. We next submitted the similarity ratings to multidimensional scaling (MDS). This analysis assessed prototypical conceptualizations as determined by compassion’s location along arousal and valence dimensions (Barrett, 2004). Following both inductions, compassion fell into the pleasant-low arousal quadrant (see Figure S1), indicating that all participants conceptualized compassion as pleasant.

In contrast, self-reports indicated that experiences of compassion varied. To compare feelings of compassion with feelings of pleasant and unpleasant states, we created a pleasant state index (the average rating of awed, excited, grateful, happy, loving, proud, tender, warm; α=.62) and an unpleasant state index (the average rating of afraid, angry, distressed, guilty, sad, sorrowful, troubled, upset; α=.90). A mixed 2 (condition: neutral, compassion) X 2 (emotion rating: pleasant, unpleasant) ANOVA with emotion rating as the repeated factor revealed a significant interaction, F(1,26)=30.44, p<.001. Those in the compassion condition felt more unpleasant (M=3.13, SD=0.59) compared with those in the neutral condition (M=1.44, SD=0.55), t(26)=7.85, p<.001, but no difference emerged for pleasant ratings, (Mneutral=2.80, SDneutral=0.74, Mcompassion=2.66, SDcompassion=0.57), t(26)=0.54, p>.59.

These findings provided the first evidence that experiences of compassion (as unpleasant) differed from prototypical conceptualizations of compassion (as pleasant). To provide a more stringent test of the mismatch between conceptualizations and experiences of compassion, we conducted a second study and induced neutral and compassion states within participants and compared results with those who received only neutral inductions. We expected all participants to conceptualize compassion as pleasant, but only those who received a compassion induction to experience compassion as unpleasant.

Method

Participants

Twenty-six students (20 female; Mage=20.50, SDage=2.10) participated in exchange for $10. Each was randomly assigned to a control (containing two neutral inductions) or compassion condition (containing one neutral and one compassion induction).

Materials

Emotion inductions

Audio clips were selected from StoryCorps (www.storycorps.org). In all clips, real people described events from their lives for approximately 2 minutes. A picture of the person accompanied each clip. Neutral-baseline clips consisted of: 1) a man talking about the time he met J.D. Salinger; and 2) a doorman talking about making others happy through his job at the Plaza Hotel. Neutral-critical clips consisted of: 1) an owner of a pest-control company talking about the satisfaction he gets from helping others; and: 2) a man talking about his experience as an announcer for the New York Yankees. Compassion clips consisted of: 1) a man and wife discussing the man’s experience with Alzheimer’s, the man’s love for his grandson, and the wife’s gratefulness for being able to take care of the man; and 2) a woman telling about her sister’s death in a subway accident and her most prized possession—a voicemail left by her sister that said “I love you!”

Similarity judgments

For each judgment, participants rated the similarity of two feelings on a 7-point scale (1=very dissimilar, 7=very similar). Participants rated all possible pairs of the following terms: afraid, alert, angry, calm, compassionate, distressed, excited, grateful, guilty, happy, proud, quiet, sad, sorrowful, and sympathetic. Lists were constructed using the Ross ordering method (Davison, 1983).

Emotion ratings

Participants rated how well emotion terms (see Table S2 for complete list) described their feeling (1=not at all; 5=very much) in response to the audio clips for each induction (e.g., “How compassionate did you feel?”).

Procedure

Participants completed two blocks that contained an emotion induction and a set of similarity judgments. In each block, participants listened to two audio clips selected to evoke a neutral or compassionate state. All participants completed an initial neutral block, followed by a second neutral block (control condition) or compassion block (compassion condition). Participants completed 105 unique similarity judgments following the emotion induction in each block and completed emotion ratings for both inductions upon finishing both blocks. They received a five-minute break and worked on a Sudoku puzzle between blocks.

Results

Manipulation Check

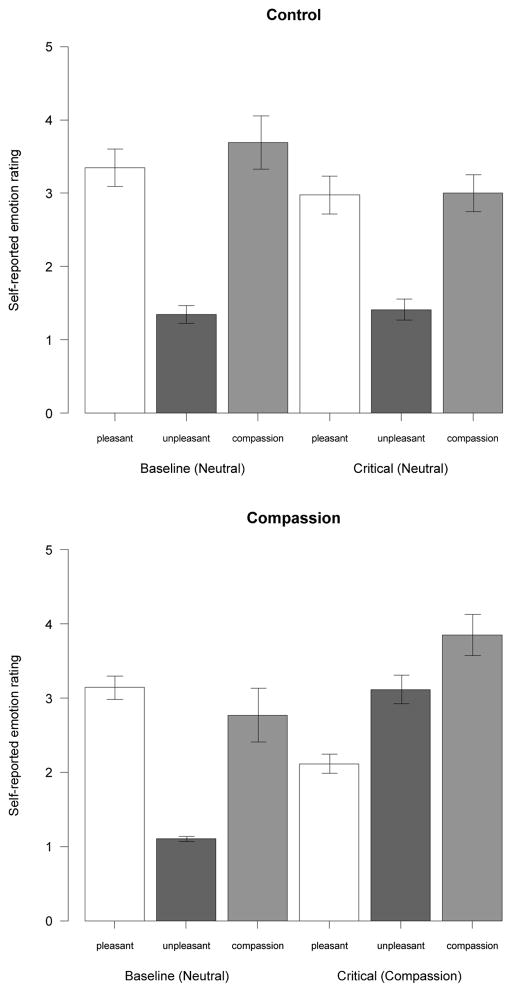

A mixed 2 (time: baseline, critical) × 2 (condition: control, compassion) ANOVA with time as the repeated factor revealed a significant interaction, F(1,24)=8.46, p<.01. Those in the compassion condition reported increased compassion following the critical compassion induction (M=3.85, SD=0.99) compared with the baseline neutral induction (M=2.77, SD=1.30), t(12)=2.34, p<.05. Those in the control condition felt slightly more compassion after the baseline neutral induction (M=3.69, SD=1.32) than the critical neutral induction (M=3.00, SD=0.91), t(12)=1.74, p<.11. The differences between conditions for baseline ratings of compassion t(24)=1.80, p>.08, unpleasant states, t(24)=1.95, p>.06, and pleasant states, t(24)=0.68, p>.50, did not reach conventional levels of statistical significance (see Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Mean (± one SE) ratings of experienced compassion, pleasant, and unpleasant states following each induction.

Similarity Ratings

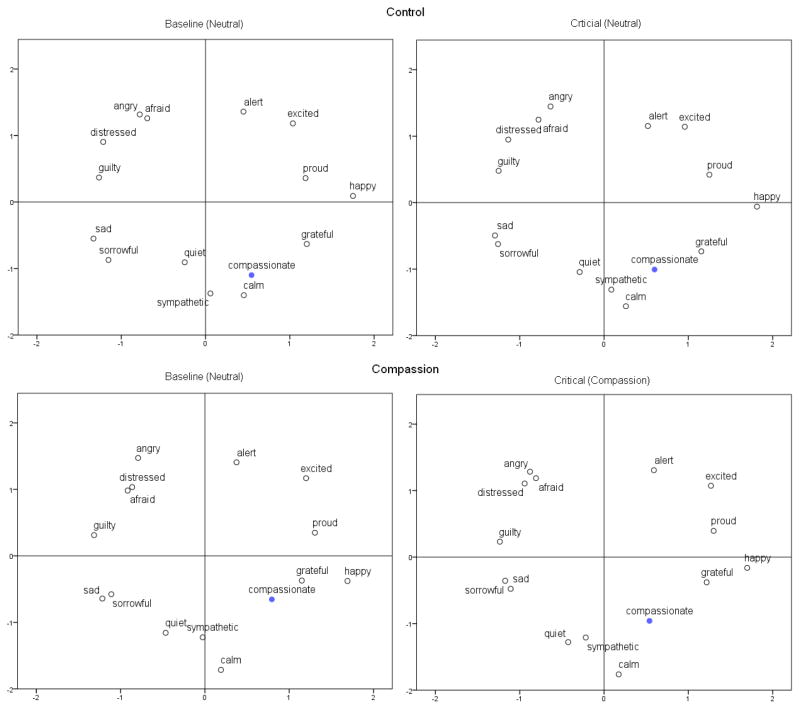

We next obtained INDSCAL MDS solutions for the similarity ratings for each induction. Stress × Dimension plots revealed a clear elbow at the two-dimensional solutions (Stress≤0.23, RSQ≥0.69; see Figure S2), indicating a two-dimensional solution best modeled the similarity ratings and accounted for a large proportion of variance in the distances between emotion-related words. A plot of the group MDS coordinates indicated the words fell in a circular order around two dimensions of valence and arousal (see Figure 1). As predicted, compassion fell into the pleasant, low arousal quadrant for all inductions, meaning all participants conceptualized compassion as pleasant.

Figure 1.

Representations of emotion concepts obtained from similarity ratings following each induction. Valence is the horizontal axis, and arousal is the vertical axis.

Self-reported Emotion Ratings

To examine the valence underlying experiences of compassion, we compared self-reported feelings of compassion (using the single item compassion) with reports of various pleasant and unpleasant states using a pleasant state index (the average rating of awed, excited, grateful, happy, loving, proud, tender, warm; α=.89) and an unpleasant state index (the average rating of afraid, angry, distressed, guilty, sad, sorrowful, troubled, upset; α=.87). Because we expected ratings of experienced compassion, pleasant, and unpleasant states to differ from each other between inductions, we treated them as levels of one factor in the following analysis. A mixed 2 (time: baseline, critical) × 3 (emotion rating: compassion, pleasant, unpleasant) × 2 (condition: control, compassion) ANOVA with time and emotion rating as repeated factors revealed a significant three-way interaction, F(2,48)=14.26, p<.001 (see Figure 2).3 Two mixed 2 (time) × 3 (emotion rating) ANOVAs separately examined each emotion condition. A significant two-way interaction emerged in the compassion condition, F(2,24)=28.02, p<.001, but not the neutral condition, F(2,24)=2.34, p>.11. We further examined differences among emotion ratings within each emotion induction using four separate repeated measures ANOVAs. Post-hoc tests with Bonferroni corrections revealed that ratings of compassion and unpleasant states exceeded ratings of pleasant states (ps<.002) following the critical compassion induction. Following all neutral inductions, ratings of compassion differed from ratings of unpleasant states (ps<.002) but not pleasant states (ps>.4).4

Participants’ experience of compassion during exposure to others’ suffering was associated with heightened unpleasant affective states. Compassion and empathic distress, however, are theoretically distinct constructs (Klimecki & Singer, 2012). Thus, we examined whether participants differentiated compassion from distress when reporting on their unpleasant affective state following the compassion induction. A high positive correlation between self-reported compassion and distress would indicate that participants used the terms to represent a global unpleasant state, whereas a low correlation would indicate that participants differentiated compassion from distress (see Lindquist & Barrett, 2008). Because we predicted self-reports of compassion to co-vary with unpleasant states following the compassion induction, we also examined correlations of compassion and distress with other typical unpleasant states (afraid, angry, concerned, distressed, guilty, sad, sorrowful, sympathetic, upset).

Following the compassion induction, experiences of compassion and distress did not correlate (r=.31, p>.3; see Table S3). Ratings of compassion correlated with sympathy and love (rs≥.65, ps<.05), but not angry, concerned, or troubled (rs≤.43; ps>.25). In contrast, ratings of distress correlated with angry, concerned, sympathy, troubled, and upset (rs≥.57; ps<.05). While ratings of compassion and distress converged with sympathy, ratings of distress converged with unpleasant states that compassion did not (angry, concerned, troubled), suggesting participants differentiated unpleasant compassion from distress.5

Discussion

Our results support the view that an emotion category contains a variety of instances, with one particular variety representing the prototypical conceptualization. The similarity ratings tapped prototypical conceptualizations, including compassion as pleasant (Shaver et al., 1987). Yet, experiences of compassion were unpleasant (following exposure to another’s suffering) or pleasant following neutral inductions (perhaps because they conveyed something positive that elicited a “heart-warming” compassion). These data clarify the nature of compassion’s valence and encourage further exploration of emotion heterogeneity. We expect these results to generalize to other emotion categories, such as sadness (sadness may feel pleasant, for example, when celebrating the life a passed loved one) or gratitude (which may at times feel unpleasant).

An alternative explanation suggests that participants experienced mixed affect during the compassion induction. It is more likely, however, that people only experience one phenomenological state at one moment. Conscious experience can move at great speed (estimated at 100–150 ms per conscious moment; Edelman & Tononi, 2000; Gray, 2004), so that pleasant and unpleasant experiences can come in and out of focus quickly, like different perceptions of a Necker cube. Research that limits the time window to momentary experience does not find dialectic representations at single moments (Scollon, Diener, Oishi, & Biswas-Diener, 2010). Thus, it is unlikely that pleasure and displeasure co-occur in real time, although people can quickly shift from one experience to another and summarize all of the contents in working memory (Barrett, Mesquita, Ochsner, & Gross, 2007).

Finally, these data raise questions concerning the functions of different conceptualizations of an emotion category. An emotion category, like compassion, refers to a population of instances that vary and therefore support outcomes appropriate to the situation. Similarity ratings, however, represent the prototypical experience, which is the one that maximally achieves the goal of the category (Barsalou, 2003). Just as an arousing experience of anger might best facilitate the removal of an obstacle in the environment, a pleasant, calm experience of compassion might best facilitate the reduction of another’s suffering. Calm compassion in the face of another’s suffering may in fact constitute one primary outcome of contemplative practice. Recent work found that participants reacted to others’ distress with unpleasant affect; however, after 6 hours of loving-kindness training, the same participants reacted to the same stimuli with pleasant affect (Klimecki, Leiberg, Lamm, & Singer, 2013). Future work should examine compassion conceptualizations across different demographics, contexts, and goal-states, which will ultimately advance the scientific understanding of compassionate experience and compassionate action.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by a National Institute of Health Director’s Pioneer Award (DP10D003312) to Lisa Feldman Barrett.

Footnotes

Context includes prior experience, which is culturally bound. Buddhist taxonomies, for example, conceptualize compassion as virtuous—a category that typically includes a pleasant tone (c.f., Dreyfus, 2002). Expert meditators likely have different conceptualizations and experiences of compassion relative to those in our samples, who have little to no meditation experience.

See supplementary online material (SOM) for details.

Repeated measures MANOVAs revealed the same results. All ANOVAs met the assumption of sphericity except for one on the baseline ratings within the compassion condition. This effect remained significant using a Greenhouse-Geisser correction, F(1.26,15.12)=22.53, p<.001.

See Table S2 for all emotion ratings.

A similar pattern emerged in the pilot study (see SOM).

References

- Barrett LF. Feelings or words? Understanding the content in self-report ratings of experienced emotion. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2004;87:266–281. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.87.2.266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barrett LF. Solving the emotion paradox: Categorization and the experience of emotion. Personality and Social Psychology Review. 2006;10:20–46. doi: 10.1207/s15327957pspr1001_2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barrett LF, Mesquita B, Ochsner KN, Gross JJ. The experience of emotion. Annual Review of Psychology. 2007;58:373–403. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.58.110405.085709. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barsalou LW. Ideals, central tendency, and frequency of instantiation as determinants of graded structure in categories. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory, and Cognition. 1985;11:629–654. doi: 10.1037//0278-7393.11.1-4.629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barsalou LW. Situated simulation in the human conceptual system. Language and Cognitive Processes. 2003;18:513–562. [Google Scholar]

- Condon P, Wilson-Mendenhall CD, Barrett LF. What is a positive emotion? The psychological construction of pleasant fear and unpleasant happiness. In: Tugade M, Shiota MN, Kirby L, editors. Handbook of Positive Emotions. New York: Guilford Press; in press. [Google Scholar]

- Davison ML. Multidimensional Scaling. New York: Wiley; 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Dreyfus G. Is compassion an emotion? A cross-cultural exploration of mental typologies. In: Davidson RJ, Harrington A, editors. Visions of Compassion: Western Scientists and Tibetan Buddhists Examine Human Nature. New York: Oxford University Press; 2002. pp. 31–45. [Google Scholar]

- Edelman GM, Tononi G. A Universe of Consciousness. New York: Basic; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Gray JA. Consciousness. New York: Oxford University Press; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Keltner D, Lerner JS. Emotion. In: Gilbert DT, Fiske ST, Lindsay G, editors. The Handbook of Social Psychology. New York: Wiley; 2010. pp. 317–352. [Google Scholar]

- Klimecki O, Singer T. Empathic distress fatigue rather than compassion fatigue? Integrating findings from empathy research in psychology and social neuroscience. In: Oakley B, Knafo A, Madhavan G, Wilson DS, editors. Pathological altruism. New York: Oxford University Press; 2012. pp. 368–383. [Google Scholar]

- Klimecki OM, Leiberg S, Lamm C, Singer T. Functional neural plasticity and associated changes in positive affect after compassion training. Cerebral Cortex. 2013;23:1552–1561. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhs142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lazarus R. Emotion and adaptation. New York: Oxford University Press; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Lindquist KA, Barrett LF. Emotional complexity. In: Lewis M, Haviland-Jones JM, Barrett LF, editors. Handbook of emotions. New York: Guilford Press; 2008. pp. 513–530. [Google Scholar]

- Scollon CN, Diener E, Oishi S, Biswas-Diener R. An experience sampling and cross-cultural investigation of the relation between pleasant and unpleasant affect. Cognition & Emotion. 2005;19:27–52. [Google Scholar]

- Shaver P, Schwartz J, Kirson D, O’Connor C. Emotion knowledge: Further explorations of a prototype approach. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1987;52:1061–1086. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.52.6.1061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simon-Thomas ER, Godzik J, Castle E, Antonenko O, Ponz A, Kogan A, Keltner D. An fMRI study of caring vs. self-focus during induced compassion and pride. Social Cognitive and Affective Neuroscience. 2012;7:635–648. doi: 10.1093/scan/nsr045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson-Mendenhall CD, Barrett LF, Barsalou LW. Neural evidence that human emotions share core affective properties. Psychological Science. 2013;24:947–956. doi: 10.1177/0956797612464242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson-Mendenhall CD, Barrett LF, Simmons WK, Barsalou LW. Grounding emotion in situated conceptualization. Neuropsychologia. 2011;49:1105–1127. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2010.12.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.