Summary

The mechanisms of tissue convergence and extension (CE) driving axial elongation in mammalian embryos, and in particular, the cellular behaviors underlying CE in the epithelial neural tissue, have not been identified. Here we show that mouse neural cells undergo mediolaterally biased cell intercalation and exhibit both apical boundary rearrangement and polarized basolateral protrusive activity. Planar polarization and coordination of these two cell behaviors is essential for neural CE, as shown by failure of mediolateral intercalation in embryos mutant for two proteins associated with planar cell polarity signaling: Vangl2 and Ptk7. Embryos with mutations in Ptk7 fail to polarize cell behaviors within the plane of the tissue, while Vangl2 mutant embryos maintain tissue polarity and basal protrusive activity, but are deficient in apical neighbor exchange. Neuroepithelial cells in both mutants fail to apically constrict, leading to craniorachischisis. These results reveal a cooperative mechanism for cell rearrangement during epithelial morphogenesis.

Keywords: neural tube, cell intercalation, convergent extension, planar cell polarity, mouse embryo, morphogenesis

Introduction

Neurulation is the process by which the prospective central nervous system is formed. In amniote embryos, this process begins with the formation of the neural plate, a flat sheet of neural ectoderm which undergoes a series of complex shape changes that result in a narrow and elongated structure with a medial neural groove and lateral neural folds (Schoenwolf, 1991). Many of these tissue-level changes are facilitated by changes in cell shape: cells of the lateral neural plate increase their apical-basal height while cells at the midline become wedgeshaped, thus creating a hinge point (Schoenwolf, 1985; Schoenwolf and Franks, 1984). The neural folds must then come together medially and fuse in order to close the neural tube. Neural fold apposition is largely facilitated by the hinge points and the surface ectoderm (Alvarez and Schoenwolf, 1992; Hackett et al., 1997), and as the folds elevate to meet medially, the neural plate also narrows significantly (Jacobson and Gordon, 1976; Schoenwolf, 1985). This narrowing (convergence) may serve to bring the neural folds closer together (Wallingford and Harland, 2002), and is associated with a concomitant extension of the tissue, which contributes to elongation of the neural plate (Jacobson and Gordon, 1976; Schoenwolf, 1985). While much is understood about the cellular mechanisms that result in the formation of the neural groove and hinge points (Schoenwolf and Powers, 1987; Shum and Copp, 1996; Smith and Schoenwolf, 1987; Smith et al., 1994), much less is known about the process of neural convergence and extension (CE) in amniote embryos.

In amphibian embryos, mediolateral cell intercalation drives CE of the neural plate (Jacobson, 1994; Keller et al., 2000) and is accomplished by polarized protrusive activity and intercalation of deep neural cells (Davidson and Keller, 1999; Elul and Keller, 2000; Elul et al., 1997). Similar cell behaviors underlie CE of the neural keel in zebrafish embryos (Harrington et al.; Warga and Kimmel, 1990), as well as mesoderm intercalation in frogs, fish, and mice (Glickman et al., 2003; Heisenberg et al., 2000; Keller et al., 2000; Shih and Keller, 1992; Yen et al., 2009; Yin et al., 2008). In all of these examples, the polarity of intercalation is determined by planar cell polarity (PCP) signaling (Ciruna et al., 2006; Goto and Keller, 2002; Jessen et al., 2002; Wallingford and Harland, 2001; Yen et al., 2009).

PCP signaling is one mechanism that links the processes of neural CE and neural tube closure, and both fail when PCP signaling is perturbed. In Xenopus embryos, loss of PCP signaling leads to failure of neural CE and an open neural tube (Goto and Keller, 2002; Wallingford and Harland, 2002). Defects in PCP signaling are also associated with neural tube closure defects in mice. Indeed, all mouse models of craniorachischisis, a failure of nearly the entire length of the neural tube to close, result from homozygous mutations in PCP components (Curtin et al., 2003; Gerrelli and Copp, 1997; Greene et al., 1998; Hamblet et al., 2002; Kibar et al., 2001; Lu et al., 2004; Murdoch et al., 2003; Wang et al., 2006b). These include Looptail (Lp) mice, which carry a point mutation in Vangl2, a homolog of the Drosophila PCP gene Van Gogh/Strabismus (Kibar et al., 2001). This mutation prevents delivery of the Vangl2 protein to the plasma membrane (Merte et al., 2010), and may also act in a dominant negative fashion by affecting distribution of other proteins, such as Vangl1 and Pk2 (Song et al., 2010; Yin et al., 2012). PCP phenotypes are also found in mice mutant for Ptk7, a gene that is involved in planar polarity, but whose Drosophila homolog is not a core member of the PCP pathway (Lu et al., 2004; Peradziryi et al., 2011). How these and other PCP genes regulate neural tube morphogenesis in amniotes is largely unknown. Unlike the neural plate of Xenopus and the neural keel of the zebrafish, in which radial and mediolateral intercalation of deep mesenchymal cells drive CE (Davidson and Keller, 1999; Elul et al., 1997; Harrington et al.), the neural plate of amniote embryos is a singlelayered pseudo-stratified epithelium. We hypothesize that the cellular mechanisms driving elongation of an epithelial tissue likely differ significantly from those of a mesenchymal cell population.

Epithelial intercalation has been best characterized in non-neural epithelia, where a variety of cellular mechanisms have been found to drive CE. Cells in the Drosophila germ band, for example, rearrange via oriented neighbor exchange and the formation/resolution of multicellular rosette structures (Bertet et al., 2004; Blankenship et al., 2006; Zallen and Blankenship, 2008). In contrast, the epidermal cells of the C. elegans embryo rearrange via large basolateral protrusions which invade between adjacent cells (Williams-Masson et al., 1998). The sea urchin archenteron and the notochord of the ascidian embryo also elongate via intercalation driven by polarized protrusive activity (Hardin, 1989; Munro and Odell, 2002). Drosophila imaginal discs elongate and evaginate by a combination of several mechanisms, including cell intercalation, cell shape change, and cell division (Condic et al., 1991; Fristrom, 1976; Taylor and Adler, 2008). Epithelial tubules in the mouse postnatal kidney elongate by polarized cell divisions (Carroll and Das, 2011; Fischer et al., 2006), while embryonic kidney tubules elongate by cell intercalations around the circumference of the tube (Karner et al., 2009), driven (at least in part) by polarized formation and resolution of epithelial rosettes (Lienkamp et al., 2012).

Thus there are a number of mechanisms that can facilitate elongation of epithelial sheets and tubes, some of which may be conserved in the neural plate of amniote embryos. Indeed, the neural plate of the chick embryo is believed to elongate through a combination of several of these mechanisms; including cell intercalation, cell shape changes, and oriented division (Sausedo et al., 1997; Schoenwolf, 1991; Schoenwolf and Alvarez, 1989; Schoenwolf and Powers, 1987; Schoenwolf and Yuan, 1995). Mediolateral cell boundary shortening in the chick forebrain neural plate drives both narrowing of the neural plate and apical constriction of neural epithelial cells, but does not appear to result in appreciable cell intercalation (Nishimura et al., 2012). While it has been demonstrated that the mouse neural tube undergoes CE (Ybot-Gonzalez et al., 2007), the underlying cellular mechanism(s) remain unknown.

Here we have identified the cellular mechanisms of neural plate elongation in mouse embryos by direct observation of live, whole embryos using time-lapse confocal microscopy. We have found that the neural epithelium undergoes mediolateral cell intercalation and exhibits both apical boundary rearrangement and mediolaterally biased basolateral protrusive activity. Both of these mechanisms contribute, perhaps equally, to mediolateral cell intercalation. We also demonstrate that Ptk7 and Vangl2, two regulators of planar cell polarity, regulate neural cell intercalation and CE. Ptk7 mutant embryos fail to polarize intercalation events within the plane of the tissue, affecting both apical and basal cell behaviors, while Vangl2 Lp mutant embryos maintain tissue polarity but are deficient in apical neighbor exchange, thus affecting only apical cell behavior. Observation of these distinct cell behavior phenotypes has allowed us to functionally separate mechanisms in both the apical and basal domains of intercalating epithelial cells.

Results

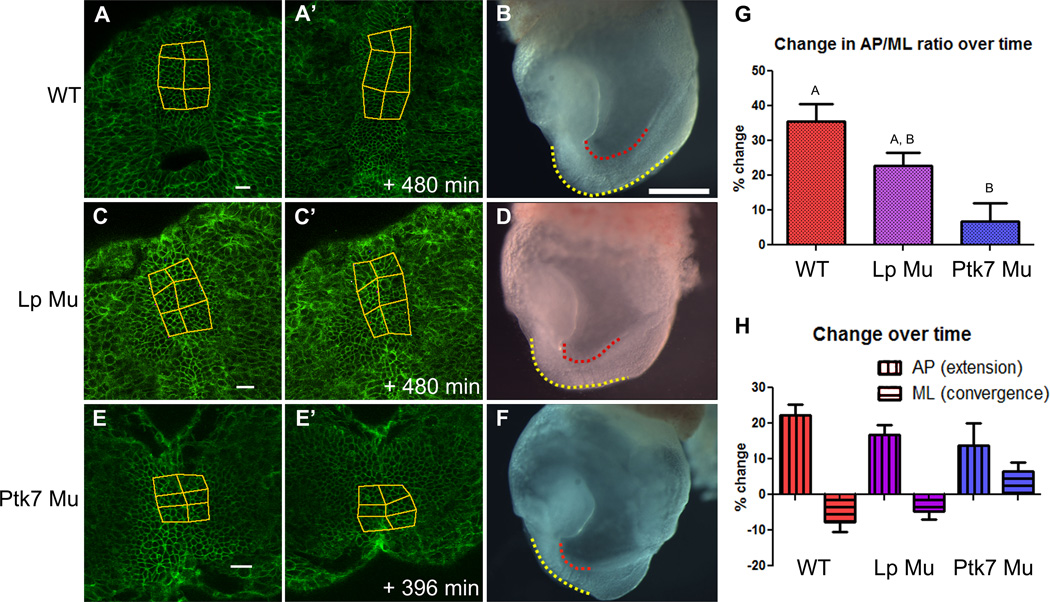

The mouse neural plate undergoes convergent extension

Eight hour time-lapse confocal movies were made of e8.0 mT/mG:ZP3 cre embryos in which every cell expresses membrane-targeted eGFP (mG). These time-lapse series focus on the ventral neural plate beginning at approximately 2 to 4 somite stage (see movie S1). To quantify the normal progress of neural CE, tissue shape changes were measured using distortion diagrams. Diagrams overlying wild type (WT) neural plates undergo substantial elongation and modest narrowing (Fig. 1A–A’), which is indicative of CE. The extent of CE was determined by measuring the change in average anterior-posterior (AP) length and mediolateral (ML) width of distortion diagrams over time. WT neural plates elongate by an average of 22.3% and narrow by an average of 7.7%, resulting in a 35.4% average increase in overall AP to ML ratio, or CE index (Fig. 1G,H).

Figure 1. The neural plate of e8 mouse embryos undergoes CE, which is reduced in Lp and Ptk7 mutant embryos.

A,C,E) Snapshots from eight hour live time-lapse movies of fluorescently labeled e8 mouse embryos. Distortion diagrams overlying neural plates represent changes in the relative position of cells over time. Anterior is up, scale bars are 25µm. A, A’) Wild type embryo (N= 12). C, C’) Vangl2 Lp mutant embryo (N=4). E, E’) Ptk7 mutant embryo (N=4). B,D,F) Images of whole e8 embryos, genotype indicated at left. Dotted lines represent length of AP axis, which is conspicuously shorter in Ptk7 mutants (F). Anterior is left. G) Graph summarizing the percent change in AP/ML ratio of distortion diagrams overlying neural plates of each embryo type over approximately eight hours. Bars labeled with the same letter are not statistically different (Kruskal-Wallis, p>.05). H) Graph summarizing the percent change in the AP (vertical striped bars) and ML dimensions (horizontal striped bars) of distortion diagrams overlying neural plates of each embryo type. All bars are means with SEM. See also Fig. S2; movie S1.

Mouse neural tissue is highly proliferative, and oriented division may contribute to the overall elongation and shaping of the neural tube (Sausedo et al., 1997). We measured the orientation of both the division plane and final position of daughter cells relative to the A–P axis in dividing cells observed within four WT time-lapse movies. No bias in the orientation of either was observed (Fig. S1). It is conceivable, however, that oriented cell divisions may play a more substantial role in neural elongation at later stages of development. Because our analysis encompasses neural plate morphogenesis only at early somite stages, we cannot exclude this possibility. Regardless of their orientations, in the mouse, cell cycles include growth and increase the volume of the tissue. The amount of convergence observed (7.7%) is relatively modest compared with the amount of extension (22.3%), suggesting that elongation of the neural plate likely occurs by a combination of increased tissue volume and convergence, with the increase in volume being channeled into extension.

Neural CE is disrupted in embryos mutant for Vangl2 and Ptk7

Embryos homozygous for mutations in Vangl2 or Ptk7 exhibit dramatic defects in axial elongation. Both are born with severely shortened A/P body axes and exhibit craniorachischisis, a failure of the neural tube to close posterior to the midbrain (Greene et al., 1998; Lu et al., 2004). To determine how neural CE is affected by mutations in these genes, 8 hour time-lapse sequences were made of homozygous mutant embryos (movie S1), and overall tissue distortions were analyzed. The CE index of Vangl2Lp/Lp mutant (Lp mutant) neural plates was 20.7% on average, compared to 35.4% in WT embryos (Fig. 1C–C’, G), consistent with the reduction of CE reported previously in Lp mutant embryos (Wang et al., 2006a; Ybot-Gonzalez et al., 2007). The CE index of Ptk7XST87/XST87 mutant (Ptk7 mutant) neural plates was only 6.7% (Fig. 1E-E’, G), which is significantly smaller than that of WT. A similar reduction in CE is detected when tissue distortion is measured according to the number of cells along the AP and ML aspects of distortion diagrams (Fig. S2). The decrease in overall CE in Lp mutant embryos is due to proportionate decreases in both convergence and extension, while the additional decrease in Ptk7 mutant embryos compared to Lp mutants is due to a further decrease in convergence alone when measured directly (Fig. 1H). However, when considered on the basis of cell number, the further decrease in the Ptk7 mutants is also proportionate (Fig. S2).

Neural plate cell morphology is altered in Vangl2 and Ptk7 mutants

The cell behaviors driving neural tube closure have been well described in chick and mouse, and include apical constriction (or wedging) of neural epithelial cells (Smith and Schoenwolf, 1987; Smith et al., 1994). Failure of neural tube closure has been attributed to failure of CE in the prospective floor plate (Wallingford and Harland, 2002). However, it is possible that failure of cell wedging could be a contributing factor in neural tube defects in mice. To examine cell shape within the mouse neural plate, whole e8.5 WT, Lp mutant, and Ptk7 mutant embryos were stained with rhodamine phalloidin to visualize cell outlines through the full thickness of the ventral neural plate. Measurements of the resulting z-stacks indicate that the apical surface of Vangl2 Lp and Ptk7 mutant neural plate cells have a significantly larger apical surface area and are significantly shorter than WT neural plate cells (Fig. S3). These aberrant cell morphologies are associated with abnormal actin organization at the medial hinge point (Fig. S3), suggesting that aberrant cell morphology contributes, along with decreased CE, to failure of neural tube closure seen in these embryos.

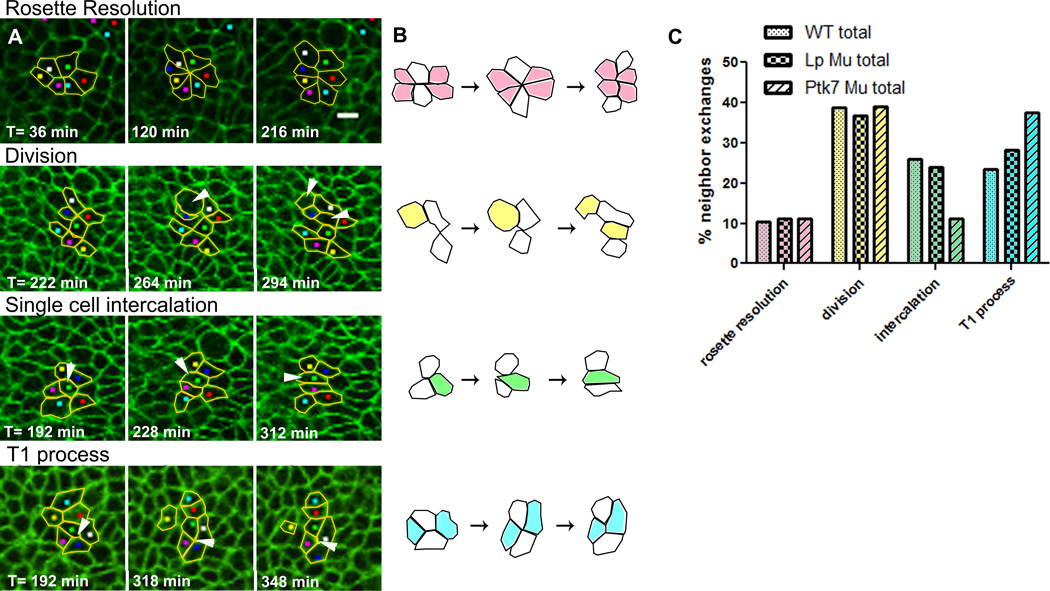

The neural plate exhibits mediolaterally biased apical neighbor exchange

To characterize the cell behavior underlying neural CE, the time-lapse movies described above were analyzed again by tracking several clusters of 6 to 8 cells within each neural plate near their apical ends to determine the extent of neighbor exchange that occurs within them. A neighbor exchange is defined as a pair of adjacent cells that are separated from one another, as illustrated by white cells in Fig. 2B. We found that neighbor exchange is associated with a number of different types of apical boundary rearrangement (Fig. 2A, B): rosette resolution, division, single cell intercalation, or T1 processes. Rosette resolution (Blankenship et al., 2006) involves a group of cells that transitions from a ML oriented array to a rosette-shaped structure with a common vertex, and then resolves to an AP oriented array via coordinated elongation of new cell-cell boundaries. Division is any neighbor exchange that results from a cell division either within or near the cluster. Single cell intercalation describes a cell moving in between two of its immediate neighbors, thereby separating them. Finally, a T1 process (Bertet et al., 2004; Weaire and Rivier, 1984; Zallen and Zallen, 2004) involves a cluster of four cells which transition from AP neighbor contact to ML neighbor contact by shortening their AP boundary to produce a 4-cell-vertex intermediate and subsequently elongating the ML boundary, Single cell intercalation, similar to “cell shuffling” (Honda et al., 2008), is distinct from the T1 process in that it is not driven by symmetric boundary shortening to a central vertex, and the final position of the intercalating cell is fully between its two neighbors. To appreciate this, compare the final positions of the green cell in the single cell intercalation illustrated in Fig. 2B with that of the two blue cells in the T1 process illustrated in Fig. 2B. Figure 2C shows the frequency of each type of neighbor exchange within WT, as well as Lp and Ptk7 mutant, neural plates. The types of neighbor exchanges exhibited do not differ between WT and mutant embryos (Fig. 2C).

Figure 2. Epithelial rosettes, among other types of apical rearrangement, occur within the neural plate.

Clusters of 6 to 8 cells were tracked within the neural plate of each of 8 WT, 4 Lp Mu, and 4 Ptk7 Mu embryos. A) Snapshots from WT time-lapse movies. Each series represents one type of neighbor exchange observed in the neural epithelium, as indicated by yellow outlines and arrowheads. Anterior is up, scale bar is 10µm. B) Schematic summary of each type of neighbor exchange. White cells represent an adjacent cell pair that is separated. C) Graph shows the frequency of each type of neighbor exchange within WT (light bars), Lp Mu (checked bars), and Ptk7 Mu (striped bars) neural plates. Bars indicate the percent of total neighbor exchanges, color of bars correspond to diagrams in (B). All bars represent the percent of the total number evaluated. The distribution of neighbor exchanges is not different between groups (chi-square, p=0.118). See also Fig. S4.

The majority of cell clusters observed exhibit multiple neighbor exchanges over the course of 8 hours, and these are often associated with multiple types of boundary rearrangement in combination. Importantly, this is also true of cell clusters that form rosettes. For example, nearly half of rosettes (29 out of 61 observed in WT embryos) display at least a partial “typical” resolution (that is, by elongation of continuous cell-cell boundaries), but the component cells then rearrange by one or more of the other types of boundary rearrangement (division, intercalation, T1 process (Fig. 2C)). The result is that the majority of neighbor exchanges observed in cell clusters that form rosettes are not the “typical” rosette resolution by coordinate elongation of linear cell boundaries. Of WT rosettes that do resolve by elongating linear boundaries, however, 86% do so along the AP axis (Fig. S4). This strong preference for AP rosette resolution is similar to that observed within the Drosophila germ band (Blankenship et al., 2006).

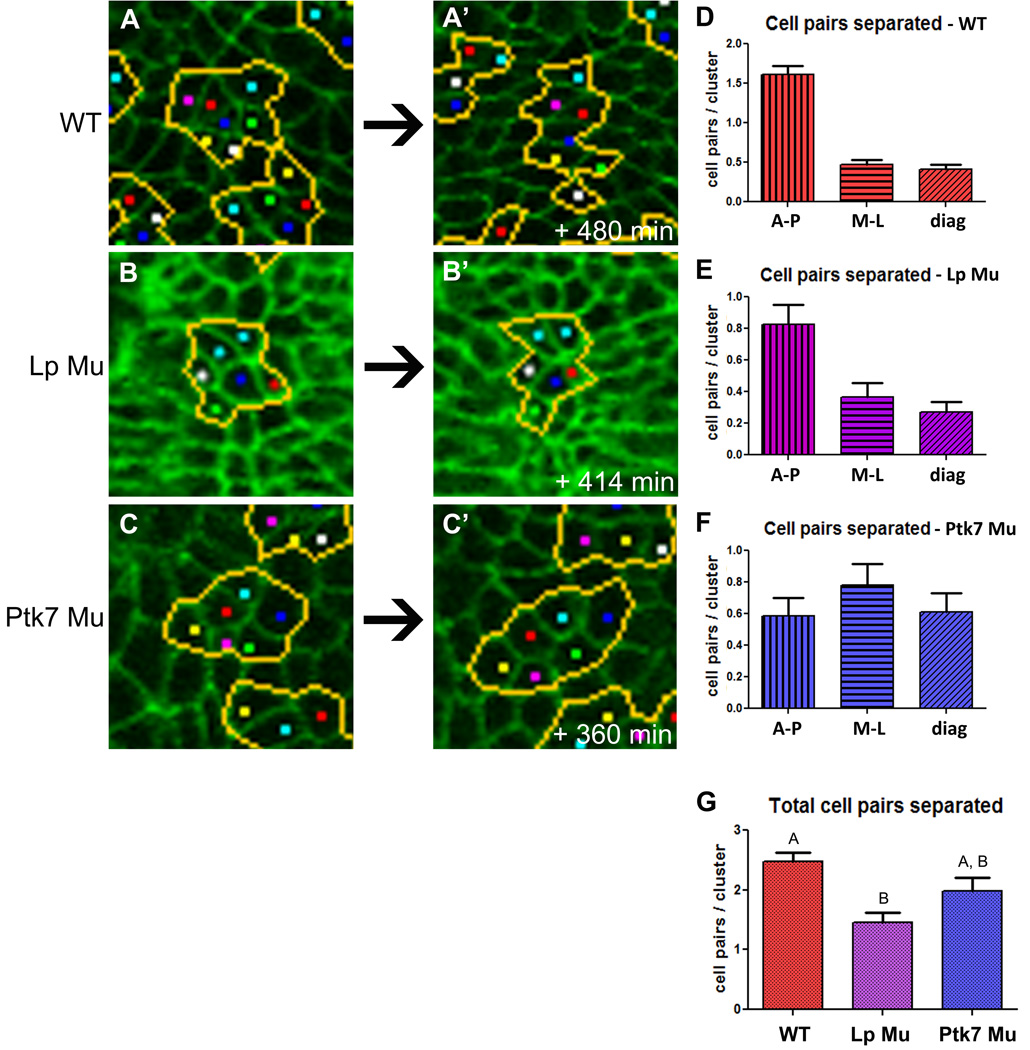

To evaluate the directionality of other types of neighbor exchange, observed neighbor exchange was scored according to the axis along which adjacent cells were separated. For example, the green and cyan cells shown in Figure 3A begin in contact with one another, but in 3A’ have been separated in the AP dimension. The majority of cell pairs within WT neural plates were found to separate along the AP axis rather than the ML or diagonal axes (Fig. 3D), demonstrating a strong bias toward mediolateral cell intercalation.

Figure 3. Neural plate cells undergo mediolateral intercalation, which is disrupted in Lp and Ptk7 mutant embryos.

A–C )Snapshots from time-lapse movies of live embryos with cell clusters outlined in WT embryos (N=118)(A,A’), Lp mutant embryos (N= 52)(B,B’), and Ptk7 mutant embryos (N=42)(C,C’). Anterior is up. D–F) Graphs shows number of cells pairs per cluster that are separated along each axis within WT (D), Lp (E), and Ptk7 mutant (F) embryos. Distribution is not significantly different between WT and Lp mutants, but is significantly different between WT and Ptk7 mutants (chi-square, p=.56, p<.0001, respectively). G) Graph indicates the total number of cell pairs separated per cluster within each embryo type. All graphs show mean with SEM. Bars labeled with the same letter are not statistically different (ANOVA, p>.05). See also Fig. S4.

Embryos mutant for Vangl2 and Ptk7 show aberrant neural epithelial intercalation

Clusters of cells were tracked within the neural plates of Lp and Ptk7 mutant embryos, and the axis of cell pair separation was quantified. Neighbor exchanges observed near the apical ends of Lp mutant neural plate cells are, like WT, biased toward AP cell pair separation, indicating a ML bias of intercalation (Fig. 3E). However, Lp mutant embryos exhibit significantly fewer total neighbor exchanges than do WT neural plates (Fig. 3G). In contrast, neighbor exchanges in Ptk7 mutant neural plates show no AP bias, but instead separate cells in random directions (Fig. 3F), indicating that cell intercalation is not mediolaterally biased in these mutants. However, the number of neighbor exchanges observed within Ptk7 mutant embryos is not significantly different from WT (Fig. 3G). These trends in neighbor exchange of pairs of cells also largely hold true for multi-cell rosettes within mutant neural plates. Of rosettes observed within WT neural plates, only 5% remain intact after 8 hours. In contrast, 31% of rosettes in Lp mutant neural plates remain intact after the same period of time (Fig. S4), consistent with the reduction in all other types of neighbor exchange. And while only 5% of rosettes in Ptk7 mutant embryos remain intact, similar to WT, those that resolve do so in random directions rather than with a strong AP preference (Fig. S4). Of note, mutant embryos exhibit a similar number of rosettes as WT, with no difference in the number of cells comprising each rosette (Fig. S4).

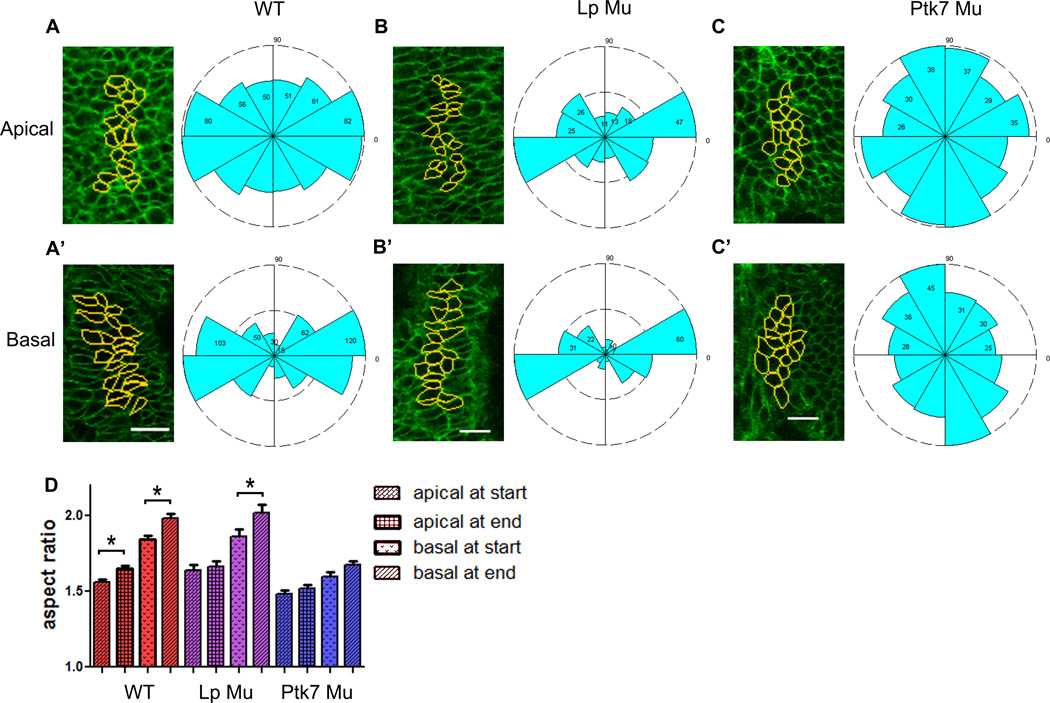

The basal ends of neural plate cells elongate and align mediolaterally

While our data support mediolaterally biased cell intercalation as a mechanism for elongation of the neural plate, other mechanisms could also contribute to this process. Cell shape change is one such mechanism that has been implicated in the elongation of many epithelial systems, including Drosophila leg imaginal discs (Condic et al., 1991) and chick neural plate (Nishimura et al., 2012; Schoenwolf and Powers, 1987). To determine the contribution of cell shape change to murine neural plate elongation, cell shape and orientation were measured at both the apical and basal ends of neural epithelial cells in WT embryos at the beginning and end of time-lapse movies. The average aspect ratio (AR) of the apical ends is significantly smaller than that of basal ends, but both ends elongate significantly over the course of 8 hours (Fig. 4D). The orientation of the apical ends of these cells is somewhat mediolaterally biased (Fig. 4A), and the basal ends are highly mediolaterally polarized (Fig. 4A’). Thus, although cells elongate significantly over time, they do so perpendicularly to the axis of tissue elongation rather than parallel to it. This shape change cannot contribute to elongation directly, but is inherent to the process of mediolateral cell intercalation (Elul et al., 1997; Harrington et al.; Hong and Brewster, 2006; Keller et al., 2000; Yen et al., 2009).

Figure 4. The basolateral ends of neural plate cells elongate and align mediolaterally over time, whereas Ptk7 mutant cells mis-align.

Cell shape and orientation of the apical and basal ends of 380 neural plate cells from 19 WT embryos, 140 cells from 7 Lp embryos, and 195 cells from 10 Ptk7 mutant embryos. Yellow outlines indicate cells measured, rose diagrams indicate the orientation of major cell axes. Only the end time point is shown. Anterior is up, and corresponds to 90 degrees in diagrams. Scale bars are 20µm. A–C’) Snapshots of WT (A,A’), Lp mutant (B,B’), and Ptk7 mutant (C,C’) cells and orientations. D) Graph indicates aspect ratio of apical and basal ends of neuroepithelial cells within each embryo type at the beginning and end of time-lapse movies, bars represent the mean and SEM. The apical ends of WT, and basal ends of WT and Lp mutant cells become significantly more elongated over time (ANOVA, p<.05). WT and Lp mutant cells are significantly more elongated than Ptk7 mutant cells at both positions within the cell and at both time points (ANOVA p<.05).

Neural plate cells exhibit mediolaterally biased protrusive activity

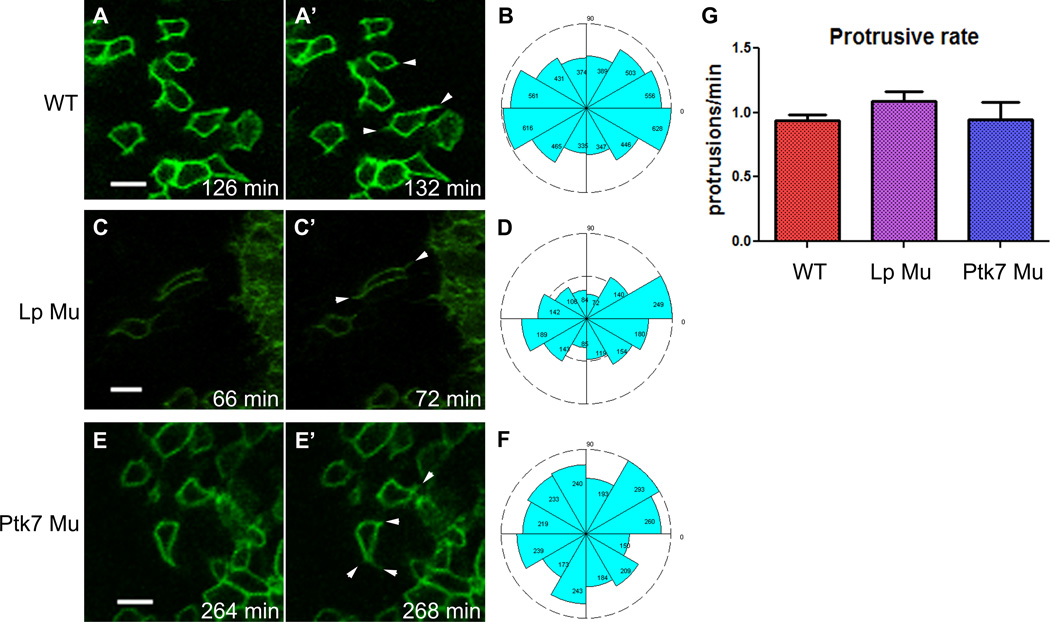

Polarized protrusive activity has been described in multiple systems that undergo mediolateral cell intercalation (Elul et al., 1997; Harrington et al.; Hong and Brewster, 2006; Keller et al., 2000; Williams-Masson et al., 1998; Yen et al., 2009), however, the best described examples are mesenchymal tissues. To determine whether basolateral protrusions occur during mediolateral intercalation within the epithelial neural plate, movies were made of mT/mG:EIIA cre embryos in which cells were scatter-labeled with mG (movie S2). In these scatter-labeled embryos, many protrusions were apparent near the basal ends of neural plate cells (Fig. 5A’, arrowheads). The largest and most frequent protrusions form at tri-cell junctions, although some smaller protrusions also form along the lateral boundaries. Individual cells generally exhibit multi-polar protrusive activity, but a strong mediolateral bias becomes apparent when all protrusions of all cells are summed (Fig. 5B). An accurate measurement of protrusions per minute was obtained by making time-lapse movies with a one-minute interval, showing an average rate of just under 1 protrusion per minute for WT embryos (Fig. 5G).

Figure 5. Cells of the neural plate exhibit polarized basal protrusive activity, for which Ptk7 is required.

A,C,E) Still shots from time-lapse movies of scatter-labeled neural plates within the indicated embryo type. Arrowheads indicate protrusions that have appeared in subsequent (4 or 6 minute) time frames. Anterior is up. Scale bars are 10 µm. B,D,F) Rose diagram indicate the direction of protrusions made by neural plate cells within the indicated embryo type (N= 5,651 protrusions, 83 cells, 10 embryos for WT; 1,663 protrusions, 26 cells, 3 embryos for Lp Mu; 2,636 protrusions, 23 cells, 3 embryos for Ptk7 Mu). Anterior corresponds to 90 degrees. G) Graph indicates the protrusive rate of neural plate cells (N= 37 WT, 11 Lp Mu, and 4 Ptk7 Mu cells), which is not different between groups (ANOVA, p=.25). Bars are means with SEM. See also movie S2.

Ptk7 mutant neural epithelial cells fail to properly elongate and orient

To determine the cellular basis of reduced ML intercalation within Lp and Ptk7 mutant embryos, cell shape and orientation were measured in the apical and basal ends of Lp and Ptk7 mutant neural plates at the beginning and end of time-lapse movies. The apical ends of cells in Lp mutant embryos do not elongate mediolaterally over time, but basal ends elongate to a similar extent as WT cells over 8 hours (Fig. 4D). In contrast, neither the apical nor basal ends of Ptk7 mutant cells elongate significantly, and at both time points are significantly less elongated than WT or Lp mutant cells (Fig. 4D). Orientation of neural epithelial cells is also different between the two mutants. Lp mutant cells are, like WT, strongly oriented along the ML axis (Fig. 4B–B’). Ptk7 mutant cells, however, orient more randomly, but with a slight bias along the AP instead of the ML axis (Fig. 4C–C’).

Time-lapse movies were made of scatter labeled Lp and Ptk7 mutant embryos to examine protrusive activity in mutant neural plate cells. Similar to WT embryos, Lp mutant neural plate cells make more protrusions in the ML direction (Fig. 5C’,D), while Ptk7 mutant neural plate cells protrude in random directions (Fig. 5E’,F). The average protrusive rate of cells within Lp mutant embryos was 1.18 protrusions per minute, and for Ptk7 mutants 0.96 protrusions per minute (Fig. 5G), neither of which is significantly different from the WT rate of protrusion. Thus the reduced rate of intercalation observed in Lp mutant embryos cannot be explained by a reduction in the protrusive rate.

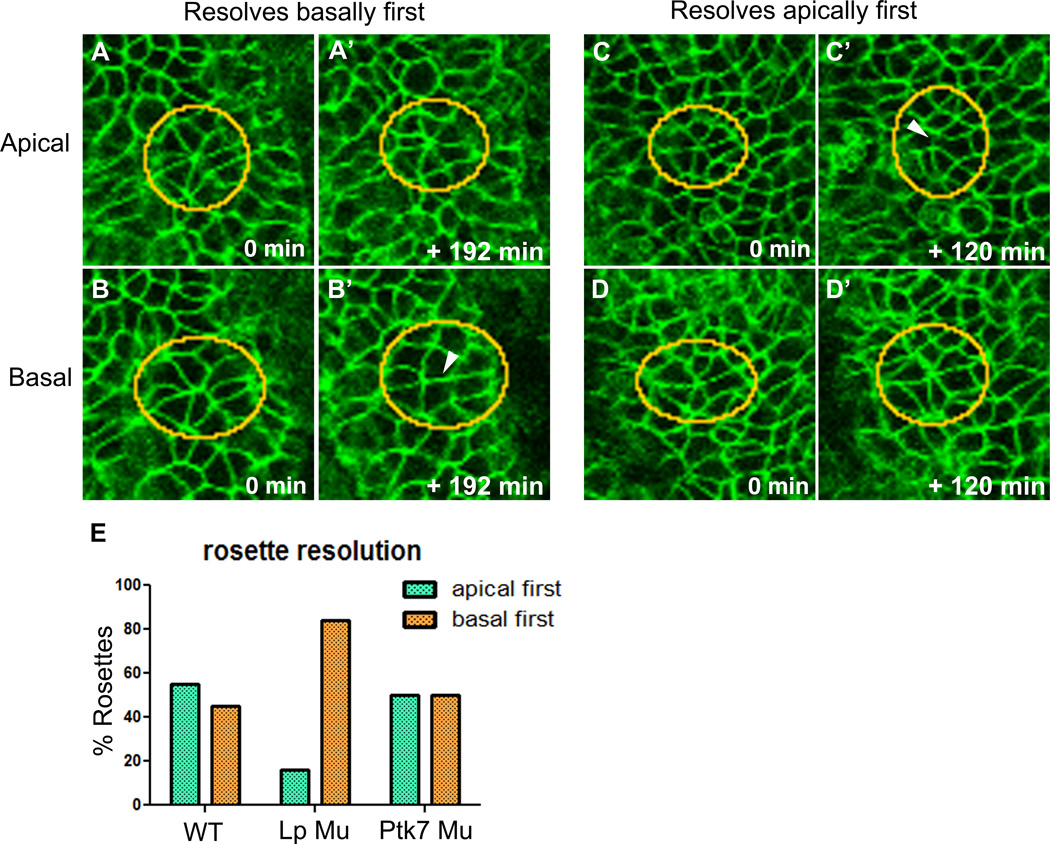

Apical boundary rearrangement and basolateral protrusive activity both contribute to mediolateral cell intercalation

Both apical boundary rearrangement and basolateral protrusive activity are observed within the neural plate, but it is unclear which of these mechanisms might be responsible for mediolateral intercalation of cells. To address this, the apical and basal ends of cells within rosettes were observed over time to determine which end of the rosette resolves first; on the assumption that whichever end resolves first is the end producing the force that drives intercalation. Rosettes were chosen as an example of neighbor exchange because they are visually distinct and provide a clear read-out of apical versus basal behavior (Fig. 6A–D’). Surprisingly, apical-first and basal-first resolutions occurred with approximately equal frequency in WT embryos (Fig. 6E). These results suggest that both apical and basolateral cell behaviors contribute, perhaps equally, to mediolateral intercalation of neural plate cells. And while rosettes within Ptk7 mutant neural plates also resolve apically first and basally first with equal frequency, Lp mutant rosettes nearly always resolve basally first (Fig. 6E), further evidence that the .Lp mutation primarily affects apical cell behavior, and that basal cell behavior is playing a significant role in driving intercalation.

Figure 6. Apical and basolateral domains both contribute to neural epithelial cell intercalation.

A–D’) Still shots from live time-lapse movies of WT neural plates at both apical and basal ends of cells. Examples of rosettes are circled, resolution indicated by arrowheads, anterior is up. A–B’ illustrate a rosette that resolves at the basal end first, C–D’ illustrate a rosette that resolves at the apical end first. E) Graph illustrates the percentage of rosettes that resolve apically (teal bars) and basally (orange bars) first in WT, Lp Mu, and Ptk7 Mu neural plates (N= 40 rosettes in 6 WT embryos, 19 rosettes in 4 Lp Mu embryos, 14 rosettes in 4 Ptk7 Mu embryos). The distribution of Lp Mu resolutions are significantly different from WT, while Ptk7 Mu resolutions are not (p=.005, .766, respectively; Fisher’s exact test).

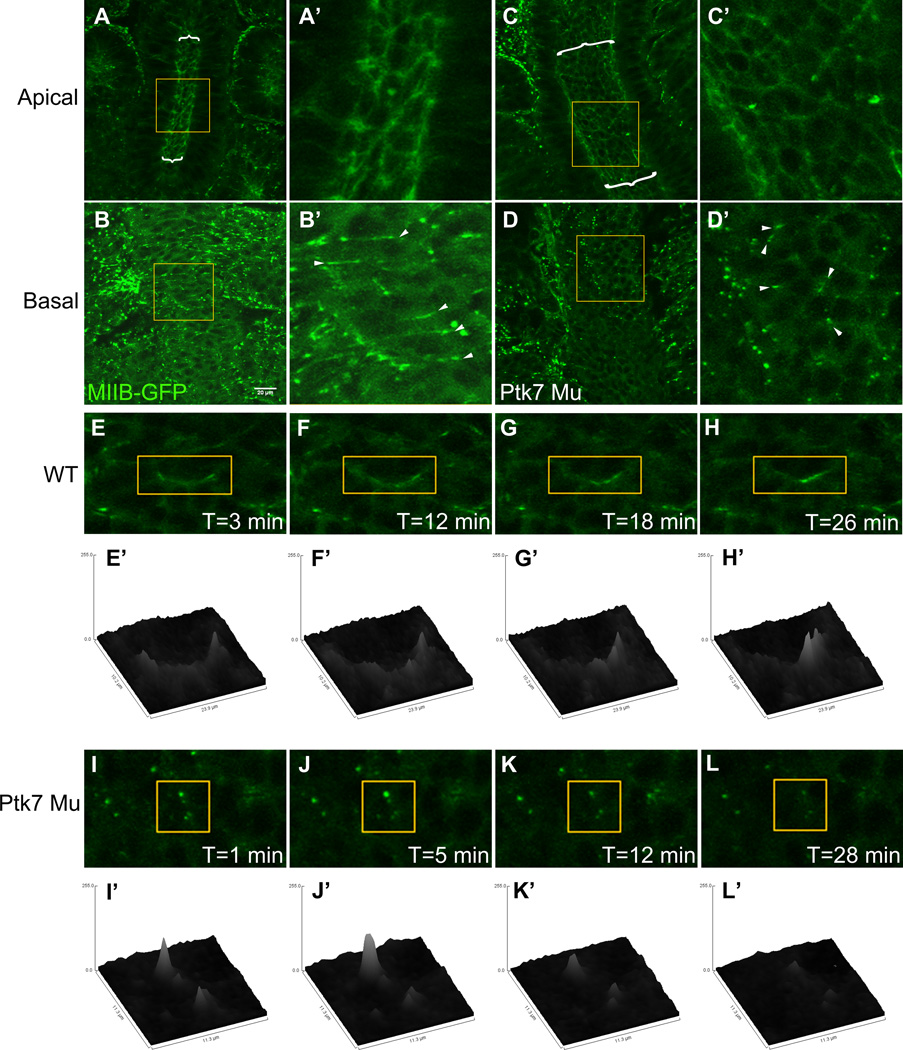

Myosin IIB localization in the neural plate implies a regulatory role for Ptk7

Polarized localization of myosin has been observed in the apices of Drosophila germ band cells, and is thought to underlie the biased cell rearrangements that drive their intercalation (Bertet et al., 2004; Blankenship et al., 2006; Rauzi et al., 2010; Zallen and Wieschaus, 2004). To determine whether a similar molecular mechanism functions during mediolateral intercalation of neural plate cells, time-lapse movies were made of the neural plates of mouse embryos expressing myosin IIB-GFP (Bao et al., 2007). Although myosin IIB is highly enriched near the apical ends of neural plate cells, it localizes equally to all apical edges rather than in a planarpolarized way (Fig. 7A, A’). Asymmetric localization was apparent, however, near the basal surface of these cells where myosin IIB is preferentially enriched at anterior and/or posterior cell boundaries (Fig. 7B, B’ arrowheads). Over a short time-course, this basally localized myosin IIB is dynamic, and changes in fluorescence intensity are apparent along the length of the myosin IIB-enriched boundary (Fig. 7E–H’). Myosin IIB localization in Ptk7 mutant embryos is likewise enriched near the apical surface of cells (Fig. 7C,C’), but fails to localize in a polarized way near basal cell ends (Fig. 7D,D’). And although basal myosin IIB is dynamic in Ptk7 mutants, changes in fluorescence intensity are not coordinated along a particular axis (Fig. 7I–L’). This lack of myosin IIB polarization is consistent with a failure of these cells to intercalate with a mediolateral bias.

Figure 7. Myosin IIB localizes anteriorly and/or posteriorly at basal cell surfaces, but fails to localize in a planar fashion in Ptk7 mutants.

A–D’) Neural plates in WT (A–B’) and Ptk7 mutant (C–D’) embryos expressing Myosin IIB-GFP. A, C show the apical surface of a WT and Ptk7 Mu neural plate, respectively; B, D show the basal surface of a WT and Ptk7 Mu neural plate, respectively. A’, B’, C’, D’ are enlarged views of the areas shown in yellow boxes. Anterior is up in all images. Arrowheads indicate areas of myosin IIB enrichment. E–H, I–L) Enlarged still shots from time-lapse movies of WT and Ptk7 Mu MIIB-GFP neural plates. E’–H’, I’–L’) Surface plots of fluorescence intensity within the regions marked by yellow boxes in E–H and I–L, respectively. See also Fig. S5.

Myosin IIB can be activated by Rho Kinase (ROCK) (Amano et al., 2000; Winter et al., 2001), which has also been implicated downstream of Vangl2, and whose activation is thought to be affected by the Lp mutation (Ybot-Gonzalez et al., 2007). Ptk7 can also activate myosin IIB via a novel pathway involving Src (Andreeva et al., this issue). To determine whether loss of ROCK and Src function is responsible for the Lp and Ptk7 phenotype, respectively, CE and cell shape/orientation were measured in live and phalloidin stained embryos treated with the ROCK inhibitor Y27632 or with SU6656, an inhibitor of Src family kinases. Y27632 treatment results in reduced neural epithelial cell height and a reduction in CE (Fig. S5), phenocopying homozygous Lp mutants. The reduction in CE, however, is not due to a reduction in neighbor exchanges as in Lp mutants, but rather appears to result from changes in cell shape (Fig. S5). SU6656 likewise recapitulates some aspects of the Ptk7 mutant phenotype; namely reduced cell height, increased apical surface area, and reduced elongation / orientation of basal cell ends (Fig. S5). However, these changes in cell shape are not accompanied by defects in CE or mediolateral cell intercalation. Taken together, these data suggested that decreased ROCK and Src activity can disrupt cell shape within the neural plate without affecting mediolateral cell intercalation..

Discussion

Similar to embryos of many species, the mammalian embryo undergoes a dramatic narrowing and elongation that defines the AP body axis. A major part of this axial elongation is neurulation, a process which involves CE of the neural plate and closure of the neural tube. Defects in neurulation, and specifically, failure of neural tube closure, are not rare, and can lead to lifelong health problems or even death, making it important to understand the fundamental underlying mechanisms. Here we have defined the cell behaviors that underlie CE of the murine neural plate, and have identified distinct apical and basolateral mechanisms that function together to drive epithelial cell intercalation. PCP signaling is critical for the spatial coordination of these mechanisms, and for proper CE of the neural plate. These observations have clarified our understanding of epithelial tissue dynamics, neural tube formation, and the role of PCP in these processes.

A model for neural plate intercalation

We have demonstrated by direct observation that WT neural epithelial cells undergo mediolateral intercalation to converge and extend the neural plate. These cells exhibit boundary rearrangement at apical ends, which display circumferential enrichment of myosin IIB. They also exhibit oriented protrusive activity in the basolateral domain. Asymmetric myosin IIB localization basally implies that these protrusions provide the directional force that biases the orientation of intercalations. Together, these results strongly implicate active mediolateral cell intercalation as a mechanism for CE. Careful examination of epithelial rosettes reveals that they can resolve at either the apical or basal ends first, suggesting that both apical and basolateral cell behaviors actively contribute to cell intercalation. Furthermore, Lp and Ptk7 mutant embryos display distinct phenotypes that allow us to functionally separate the behavior of apical and basolateral domains.

Ptk7 mutant neural epithelial cells exhibit reduced elongation and mis-alignment of their basal ends, with protrusive activity that is random rather than mediolaterally biased. Myosin IIB localization is likewise randomized near basal ends. At their apical ends, there is a corresponding loss of ML biased neighbor exchange, but no decrease in the frequency of intercalation events. Significantly, rosettes within Ptk7 mutant neural plates resolve with equal frequency at the apical and basal ends first, implying that each of these domains contributes equally to intercalation, even though it is mis-oriented. These cells appear to maintain both apical and basal behaviors required for intercalation, and can coordinate the two, but cannot execute them in an oriented way that produces CE. So while intrinsic cell polarity is maintained, they have lost their ability to recognize the tissue axis.

Neural epithelial cells within Lp mutant embryos, on the other hand, elongate, orient, and make protrusions in the ML direction just as in WT embryos. However, Lp mutant cells exchange apical neighbors at only half the rate of WT cells. Indeed, rosettes within Lp mutant neural plates nearly always resolve at the basal end first, suggesting either that the apical portion of the intercalation mechanism is not functioning normally, or perhaps that it is no longer properly coupled to the basolateral mechanism. These cells do maintain their polarity within the tissue, though. This provides evidence that the basolateral portion of the intercalation mechanism is not sufficient to drive CE alone, and that it must cooperate with the apical domain to drive efficient CE.

Taken together, these data provide us with a likely mechanism of epithelial cell intercalation and neural plate CE. The basal ends of neural epithelial cells elongate, align, and protrude in the ML direction; thereby providing directionality to intercalation events. Meanwhile, apical ends actively reorganize their boundaries to promote biased neighbor exchange, cooperatively driving mediolateral cell intercalation. If either of these cellular mechanisms is perturbed, intercalation cannot occur properly. In the case of Ptk7 mutant embryos, apical boundaries can rearrange at a normal rate, but neighbor exchanges and basolateral protrusions are mis-oriented, and CE fails. In the case of Lp embryos, basal ends align and protrude normally, but apical boundary rearrangement is reduced, and CE fails.

Mechanisms of epithelial cell rearrangement

Both basolateral protrusive activity and apical boundary rearrangements have been observed within the mouse neural plate, and both behaviors have been implicated in driving active cell intercalation in other systems. Mediolaterally polarized protrusive activity is a highly conserved mechanism demonstrated to promote cell intercalation resulting in elongation of both mesenchymal and epithelial tissues in many species, including ascidians, nematodes, frogs, fish, and mice (Heisenberg et al., 2000; Keller et al., 2000; Munro and Odell, 2002; Shih and Keller, 1992; Williams-Masson et al., 1998; Yen et al., 2009; Yin et al., 2008). Although polarized protrusive activity is best described in mesenchymal cells, it has also been documented within epithelial tissues. The epidermis of C. elegans and the notochord of the ascidian, for example, both make directed basolateral protrusions that drive cell intercalation and thus tissue elongation (Williams-Masson et al., 1998) (Munro and Odell, 2002).

Apical boundary rearrangement has also been implicated in elongation of epithelial tissues. Biased contractility of adherens junctions at apical cell ends has been suggested to be responsible for elongation of the Drosophila germ band (Bertet et al., 2004; Blankenship et al., 2006; Zallen and Blankenship, 2008), vertebrate kidney tubules (Lienkamp et al., 2012), and chick neural plate (Nishimura et al., 2012). In Drosophila, these apical rearrangements occur in the form of either T1 processes or multi-cellular rosettes. The current study describes both of these cellular mechanisms within the mouse neural plate, and while T1 processes appear similar between the two systems, multi-cellular rosettes may be functionally distinct between fly and mouse. Like rosettes in the Drosophila germ band (Blankenship et al., 2006), rosettes within WT mouse neural plates resolve with a strong AP preference. However, unlike the germ band, rosettes in the mouse neural plate often do not resolve by elongation of a common boundary, and are instead disrupted by one or more other types of boundary rearrangement. It is possible that these epithelial rosettes represent analogous structures within their respective species, but differences in the ways they are resolved may indicate functional and/or mechanistic distinctions between them. Comparisons between these two systems are difficult, however, considering that the germ band elongates over a much shorter period of time, and largely in the absence of cell divisions (Irvine and Wieschaus, 1994).

Role of planar polarity

While Vangl2 and Ptk7 have both been demonstrated to control planar polarity of many embryonic structures in mice (Lu et al., 2004; Montcouquiol et al., 2003; Ybot-Gonzalez et al., 2007), only Vangl2 possesses a homolog within the Drosophila PCP pathway (Kibar et al., 2001). Despite the well-established role of Vangl2 in planar polarity in many species (Darken et al., 2002; Goto and Keller, 2002; Jessen et al., 2002; Montcouquiol et al., 2003; Park and Moon, 2002; Wolff and Rubin, 1998), Vangl2 Lp mutant neural plate cells do not exhibit a loss of polarity. These cells elongate, align, and protrude in the ML direction just as WT cells do, implying that they maintain a sense of their position within the plane of cells. Ptk7 mutant cells, however, do appear to have lost recognition of tissue polarity entirely. They maintain intrinsic cell polarity and all of the correct cell behaviors, but fail to execute them in an oriented manner.

It is possible that tissue polarity is maintained in Lp mutant embryos because of partial redundancy with Vangl1. Indeed, Vangl1/2 double mutant mice are significantly shorter AP than Vangl2 mutants (Song et al., 2010), implying that they display more severe defects in CE. The Lp phenotype may also be related to dynamics at the apical ends of cells. The reduced ability of Lp mutant cells to exchange neighbors could suggest a reduction in the turnover of adherens junction proteins, for example. Indeed, cadherins have been implied in CE in several examples of tissue morphogenesis, often downstream of PCP signaling (Chacon-Heszele et al., 2012; Lindqvist et al., 2010; Speirs et al., 2010; Ulrich et al., 2005), and PCP components have been demonstrated to be important for cadherin recycling in Drosophila cells, including Vang/Stbm (Classen et al., 2005; Warrington et al., 2013).

Interestingly, despite the distinct cell intercalation phenotypes observed between Lp and Ptk7 mutants, they exhibit a very similar cell morphology phenotype. In both mutants, neural cells are shorter and less apically constricted than WT. Our data suggest that failure of neural tube closure may be closely related to aberrant cell morphology. Lp mutants display a less severe intercalation defect than Ptk7 mutants, and more efficient CE, but still fail to close their neural tube. Failure of apical constriction results in an abnormally shaped neural plate, as previously reported in Lp embryos (Greene et al., 1998), and it is likely that this abnormal shape prohibits neural tube closure regardless of the degree of CE that it undergoes. While it has been suggested that failure of CE alone is responsible for failed neural tube closure in Xenopus (Wallingford and Harland, 2001), we hypothesize that failure of apical constriction is a more direct cause of the open neural tube observed in Lp and Ptk7 mouse mutants.

In summary, we have found that the murine neural plate undergoes convergent extension by mediolateral intercalation of neural epithelial cells, which is driven by a combination of apical boundary rearrangement and biased basolateral protrusive activity. These behavioral mechanisms are distinct, and both are dependent on PCP signaling, providing a model for the vertebrate embryo of cooperative apical and basolateral cellular mechanisms for epithelial cell intercalation.

Experimental Methods

Animals and embryo collection

Animal use protocols were reviewed and approved by the University of Virginia Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee, and were in compliance with PHS and USDA guidelines for laboratory animal welfare. Crosses were set up between females and males of the desired strains (see Supplemental Material) and the morning a plug was identified was designated 0.5 days post-coitum (dpc). Progeny were dissected at 8 to 8.5 dpc, usually corresponding to 2–4 somite stage, in ice cold medium. For time-lapse imaging, mT/mG embryos were examined for mG expression, and mG-positive embryos were oriented with their distal tips facing down within the teeth of a rubber “comb” cut from CoverWell perfusion well gaskets and attached to a glassbottom culture dish. They were secured in this position with silicone grease and Nitex mesh and cultured in 50% rat serum (Harlan Bioproducts for Science, Indianapolis, IN), 50% whole embryo culture medium (Yen et al., 2009) on a heated stage. After imaging, embryos were lysed and genotyped by PCR.

Inhibitor treatment

For live imaging: mG positive WT embryos were set up for imaging as described above, and 10µM Y27632, 5µM SU6656 (Sigma), or an equal volume of DMSO was added to the culture medium approximately one hour prior to imaging. For immunofluorescence: WT embryos were dissected at E7.75, then cultured overnight on a roller in culture medium containing inhibitors or DMSO at concentrations described above. Embryos were removed from culture after approximately 16 hours and processed for immunofluorescence as described below.

Immunofluorescence

mG-negative embryos were fixed for 15 – 20 min in 4% paraformaldehyde, rinsed twice with PBS, and yolk sacs were removed. Embryos were blocked in 5% bovine serum albumin and 10% fetal bovine serum, then incubated in rhodamine phalloidin (Invitrogen) at 1:50 in PBS-tween. Embryos were rinsed with PBS-tween and flat mounted in glass bottom dishes for confocal imaging.

Microscopy

Live fluorescent embryos were positioned distal tip down on an inverted microscope to collect a Z stack (generally with a 2µm step size) through the full depth of the ventral neural plate region at every time-point (generally every 6 minutes) over 8 hours. Imaging of embryos was performed using either a BioRad Radiance 2100 or a Zeiss 510 Meta laser scanning confocal microscope. A Plan Fluor 20× NA 0.75 multi-immersion objective lens and LaserSharp2000 software were used to acquire confocal and images using the Biorad, and a plan-apochromat 25× water NA 0.8 objective lens and LSM software version 4.0 were used with the Zeiss.

Image Analysis

Image J was used to view time-lapse movies and to concatenate single optical sections across time in order to align each movie in the Z dimension and best visualize the tissue position of interest. Most time-lapse movies were also aligned in the X and Y axes prior to further analysis to eliminate whole embryo drift from tracking results. Image J was used to manually track cells, make and measure distortion diagrams, and measure orientations of protrusions. Measurements of cell clusters were made using a binding rectangle, while measurements of individual cells were made by fitting an ellipse to each cell.

Statistical analysis

PAST software was used to make rose diagrams and to analyze the associated circular statistics. Other statistical analyses were performed using Graphpad Prism 5 software, and included ANOVA with a post-hoc test for multiple comparisons of means, the Kruskal-Wallis test for non-parametric samples, and chi-square and Fisher’s exact tests for sampling distributions. The statistical analysis used to analyze the specific data is listed in each figure legend.

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

Mouse neural plate undergoes convergent extension by mediolateral cell intercalation.

Distinct apical and basolateral mechanisms drive neuroepithelial cell intercalation.

Planar polarity of neural cell motility and intercalation requires Ptk7 function.

Apical boundary rearrangement is inhibited in Vangl2 mutant neural epithelium.

Acknowledgements

We thank Dr. Raymond Keller for critical reading of the manuscript and help with data interpretation; Dr. Paul Skoglund, Dr. Dave Shook, and Katherine Pfister for helpful suggestions while interpreting results; Dr. John Wallingford for suggestions regarding experimental design; and Dr. Ammasi Periasamy and the W.M Keck Center for Cellular Imaging for assistance with live imaging. This work was supported by NSF grant IOS-1051294 to AS and by NIH grant R01 DC009238 to XL. MW was supported by NIH training grant T32 GM008136.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Alvarez IS, Schoenwolf GC. Expansion of surface epithelium provides the major extrinsic force for bending of the neural plate. J Exp Zool. 1992;261:340–348. doi: 10.1002/jez.1402610313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amano M, Fukata Y, Kaibuchi K. Regulation and functions of Rho-associated kinase. Exp Cell Res. 2000;261:44–51. doi: 10.1006/excr.2000.5046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andreeva A, Lee J, Lohia M, Wu X, Macara IG, Lu X. PTK7-Src signaling at epithelial cell contacts mediates spatial organization of actomyosin and planar cell polarity. Dev Cell. 2014 doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2014.02.008. XXX, XX-XX, this issue. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bao J, Ma X, Liu C, Adelstein RS. Replacement of nonmuscle myosin II-B with II-A rescues brain but not cardiac defects in mice. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:22102–22111. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M702731200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bertet C, Sulak L, Lecuit T. Myosin-dependent junction remodelling controls planar cell intercalation and axis elongation. Nature. 2004;429:667–671. doi: 10.1038/nature02590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blankenship JT, Backovic ST, Sanny JS, Weitz O, Zallen JA. Multicellular rosette formation links planar cell polarity to tissue morphogenesis. Dev Cell. 2006;11:459–470. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2006.09.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carroll TJ, Das A. Planar cell polarity in kidney development and disease. Organogenesis. 2011;7:180–190. doi: 10.4161/org.7.3.18320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chacon-Heszele MF, Ren D, Reynolds AB, Chi F, Chen P. Regulation of cochlear convergent extension by the vertebrate planar cell polarity pathway is dependent on p120-catenin. Development. 2012;139:968–978. doi: 10.1242/dev.065326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ciruna B, Jenny A, Lee D, Mlodzik M, Schier AF. Planar cell polarity signalling couples cell division and morphogenesis during neurulation. Nature. 2006;439:220–224. doi: 10.1038/nature04375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Classen AK, Anderson KI, Marois E, Eaton S. Hexagonal packing of Drosophila wing epithelial cells by the planar cell polarity pathway. Dev Cell. 2005;9:805–817. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2005.10.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Condic ML, Fristrom D, Fristrom JW. Apical cell shape changes during Drosophila imaginal leg disc elongation: a novel morphogenetic mechanism. Development. 1991;111:23–33. doi: 10.1242/dev.111.1.23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curtin JA, Quint E, Tsipouri V, Arkell RM, Cattanach B, Copp AJ, Henderson DJ, Spurr N, Stanier P, Fisher EM, et al. Mutation of Celsr1 disrupts planar polarity of inner ear hair cells and causes severe neural tube defects in the mouse. Curr Biol. 2003;13:1129–1133. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(03)00374-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Darken RS, Scola AM, Rakeman AS, Das G, Mlodzik M, Wilson PA. The planar polarity gene strabismus regulates convergent extension movements in Xenopus. EMBO J. 2002;21:976–985. doi: 10.1093/emboj/21.5.976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davidson LA, Keller RE. Neural tube closure in Xenopus laevis involves medial migration, directed protrusive activity, cell intercalation and convergent extension. Development. 1999;126:4547–4556. doi: 10.1242/dev.126.20.4547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elul T, Keller R. Monopolar protrusive activity: a new morphogenic cell behavior in the neural plate dependent on vertical interactions with the mesoderm in Xenopus. Dev Biol. 2000;224:3–19. doi: 10.1006/dbio.2000.9746. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elul T, Koehl MA, Keller R. Cellular mechanism underlying neural convergent extension in Xenopus laevis embryos. Dev Biol. 1997;191:243–258. doi: 10.1006/dbio.1997.8711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fischer E, Legue E, Doyen A, Nato F, Nicolas JF, Torres V, Yaniv M, Pontoglio M. Defective planar cell polarity in polycystic kidney disease. Nat Genet. 2006;38:21–23. doi: 10.1038/ng1701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fristrom D. The mechanism of evagination of imaginal discs of Drosophila melanogaster. III. Evidence for cell rearrangement. Dev Biol. 1976;54:163–171. doi: 10.1016/0012-1606(76)90296-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerrelli D, Copp AJ. Failure of neural tube closure in the loop-tail (Lp) mutant mouse: analysis of the embryonic mechanism. Brain Res Dev Brain Res. 1997;102:217–224. doi: 10.1016/s0165-3806(97)00099-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glickman NS, Kimmel CB, Jones MA, Adams RJ. Shaping the zebrafish notochord. Development. 2003;130:873–887. doi: 10.1242/dev.00314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goto T, Keller R. The planar cell polarity gene strabismus regulates convergence and extension and neural fold closure in Xenopus. Dev Biol. 2002;247:165–181. doi: 10.1006/dbio.2002.0673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greene ND, Gerrelli D, Van Straaten HW, Copp AJ. Abnormalities of floor plate, notochord and somite differentiation in the loop-tail (Lp) mouse: a model of severe neural tube defects. Mech Dev. 1998;73:59–72. doi: 10.1016/s0925-4773(98)00029-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hackett DA, Smith JL, Schoenwolf GC. Epidermal ectoderm is required for full elevation and for convergence during bending of the avian neural plate. Dev Dyn. 1997;210:397–406. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0177(199712)210:4<397::AID-AJA4>3.0.CO;2-B. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamblet NS, Lijam N, Ruiz-Lozano P, Wang J, Yang Y, Luo Z, Mei L, Chien KR, Sussman DJ, Wynshaw-Boris A. Dishevelled 2 is essential for cardiac outflow tract development, somite segmentation and neural tube closure. Development. 2002;129:5827–5838. doi: 10.1242/dev.00164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hardin J. Local shifts in position and polarized motility drive cell rearrangement during sea urchin gastrulation. Dev Biol. 1989;136:430–445. doi: 10.1016/0012-1606(89)90268-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harrington MJ, Chalasani K, Brewster R. Cellular mechanisms of posterior neural tube morphogenesis in the zebrafish. Dev Dyn. 239:747–762. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.22184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heisenberg CP, Tada M, Rauch GJ, Saude L, Concha ML, Geisler R, Stemple DL, Smith JC, Wilson SW. Silberblick/Wnt11 mediates convergent extension movements during zebrafish gastrulation. Nature. 2000;405:76–81. doi: 10.1038/35011068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Honda H, Nagai T, Tanemura M. Two different mechanisms of planar cell intercalation leading to tissue elongation. Dev Dyn. 2008;237:1826–1836. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.21609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hong E, Brewster R. N-cadherin is required for the polarized cell behaviors that drive neurulation in the zebrafish. Development. 2006;133:3895–3905. doi: 10.1242/dev.02560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Irvine KD, Wieschaus E. Cell intercalation during Drosophila germband extension and its regulation by pair-rule segmentation genes. Development. 1994;120:827–841. doi: 10.1242/dev.120.4.827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacobson AG. Normal neurulation in amphibians. [discussion 21–24];Ciba Found Symp. 1994 181:6–21. doi: 10.1002/9780470514559.ch2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacobson AG, Gordon R. Changes in the shape of the developing vertebrate nervous system analyzed experimentally, mathematically and by computer simulation. J Exp Zool. 1976;197:191–246. doi: 10.1002/jez.1401970205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jessen JR, Topczewski J, Bingham S, Sepich DS, Marlow F, Chandrasekhar A, Solnica-Krezel L. Zebrafish trilobite identifies new roles for Strabismus in gastrulation and neuronal movements. Nat Cell Biol. 2002;4:610–615. doi: 10.1038/ncb828. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karner CM, Chirumamilla R, Aoki S, Igarashi P, Wallingford JB, Carroll TJ. Wnt9b signaling regulates planar cell polarity and kidney tubule morphogenesis. Nat Genet. 2009;41:793–799. doi: 10.1038/ng.400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keller R, Davidson L, Edlund A, Elul T, Ezin M, Shook D, Skoglund P. Mechanisms of convergence and extension by cell intercalation. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 2000;355:897–922. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2000.0626. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kibar Z, Vogan KJ, Groulx N, Justice MJ, Underhill DA, Gros P. Ltap, a mammalian homolog of Drosophila Strabismus/Van Gogh, is altered in the mouse neural tube mutant Loop-tail. Nat Genet. 2001;28:251–255. doi: 10.1038/90081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lienkamp SS, Liu K, Karner CM, Carroll TJ, Ronneberger O, Wallingford JB, Walz G. Vertebrate kidney tubules elongate using a planar cell polarity-dependent, rosette-based mechanism of convergent extension. Nat Genet. 2012 doi: 10.1038/ng.2452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindqvist M, Horn Z, Bryja V, Schulte G, Papachristou P, Ajima R, Dyberg C, Arenas E, Yamaguchi TP, Lagercrantz H, et al. Vang-like protein 2 and Rac1 interact to regulate adherens junctions. J Cell Sci. 2010;123:472–483. doi: 10.1242/jcs.048074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu X, Borchers AG, Jolicoeur C, Rayburn H, Baker JC, Tessier-Lavigne M. PTK7/CCK-4 is a novel regulator of planar cell polarity in vertebrates. Nature. 2004;430:93–98. doi: 10.1038/nature02677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merte J, Jensen D, Wright K, Sarsfield S, Wang Y, Schekman R, Ginty DD. Sec24b selectively sorts Vangl2 to regulate planar cell polarity during neural tube closure. Nat Cell Biol. 2010;12:41–46. doi: 10.1038/ncb2002. sup pp 41–48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montcouquiol M, Rachel RA, Lanford PJ, Copeland NG, Jenkins NA, Kelley MW. Identification of Vangl2 and Scrb1 as planar polarity genes in mammals. Nature. 2003;423:173–177. doi: 10.1038/nature01618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Munro EM, Odell GM. Polarized basolateral cell motility underlies invagination and convergent extension of the ascidian notochord. Development. 2002;129:13–24. doi: 10.1242/dev.129.1.13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murdoch JN, Henderson DJ, Doudney K, Gaston-Massuet C, Phillips HM, Paternotte C, Arkell R, Stanier P, Copp AJ. Disruption of scribble (Scrb1) causes severe neural tube defects in the circletail mouse. Hum Mol Genet. 2003;12:87–98. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddg014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nishimura T, Honda H, Takeichi M. Planar cell polarity links axes of spatial dynamics in neural-tube closure. Cell. 2012;149:1084–1097. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.04.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park M, Moon RT. The planar cell-polarity gene stbm regulates cell behaviour and cell fate in vertebrate embryos. Nat Cell Biol. 2002;4:20–25. doi: 10.1038/ncb716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peradziryi H, Kaplan NA, Podleschny M, Liu X, Wehner P, Borchers A, Tolwinski NS. PTK7/Otk interacts with Wnts and inhibits canonical Wnt signalling. EMBO J. 2011;30:3729–3740. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2011.236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rauzi M, Lenne PF, Lecuit T. Planar polarized actomyosin contractile flows control epithelial junction remodelling. Nature. 2010;468:1110–1114. doi: 10.1038/nature09566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sausedo RA, Smith JL, Schoenwolf GC. Role of nonrandomly oriented cell division in shaping and bending of the neural plate. J Comp Neurol. 1997;381:473–488. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schoenwolf GC. Shaping and bending of the avian neuroepithelium: morphometric analyses. Dev Biol. 1985;109:127–139. doi: 10.1016/0012-1606(85)90353-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schoenwolf GC. Cell movements driving neurulation in avian embryos. Development. 1991;2(Suppl):157–168. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schoenwolf GC, Alvarez IS. Roles of neuroepithelial cell rearrangement and division in shaping of the avian neural plate. Development. 1989;106:427–439. doi: 10.1242/dev.106.3.427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schoenwolf GC, Franks MV. Quantitative analyses of changes in cell shapes during bending of the avian neural plate. Dev Biol. 1984;105:257–272. doi: 10.1016/0012-1606(84)90284-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schoenwolf GC, Powers ML. Shaping of the chick neuroepithelium during primary and secondary neurulation: role of cell elongation. Anat Rec. 1987;218:182–195. doi: 10.1002/ar.1092180214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schoenwolf GC, Yuan S. Experimental analyses of the rearrangement of ectodermal cells during gastrulation and neurulation in avian embryos. Cell Tissue Res. 1995;280:243–251. doi: 10.1007/BF00307795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shih J, Keller R. Cell motility driving mediolateral intercalation in explants of Xenopus laevis. Development. 1992;116:901–914. doi: 10.1242/dev.116.4.901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shum AS, Copp AJ. Regional differences in morphogenesis of the neuroepithelium suggest multiple mechanisms of spinal neurulation in the mouse. Anat Embryol (Berl) 1996;194:65–73. doi: 10.1007/BF00196316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith JL, Schoenwolf GC. Cell cycle and neuroepithelial cell shape during bending of the chick neural plate. Anat Rec. 1987;218:196–206. doi: 10.1002/ar.1092180215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith JL, Schoenwolf GC, Quan J. Quantitative analyses of neuroepithelial cell shapes during bending of the mouse neural plate. J Comp Neurol. 1994;342:144–151. doi: 10.1002/cne.903420113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song H, Hu J, Chen W, Elliott G, Andre P, Gao B, Yang Y. Planar cell polarity breaks bilateral symmetry by controlling ciliary positioning. Nature. 2010;466:378–382. doi: 10.1038/nature09129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Speirs CK, Jernigan KK, Kim SH, Cha YI, Lin F, Sepich DS, DuBois RN, Lee E, Solnica-Krezel L. Prostaglandin Gbetagamma signaling stimulates gastrulation movements by limiting cell adhesion through Snai1a stabilization. Development. 2010;137:1327–1337. doi: 10.1242/dev.045971. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor J, Adler PN. Cell rearrangement and cell division during the tissue level morphogenesis of evaginating Drosophila imaginal discs. Dev Biol. 2008;313:739–751. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2007.11.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ulrich F, Krieg M, Schötz EM, Link V, Castanon I, Schnabel V, Taubenberger A, Mueller D, Puech PH, Heisenberg CP. Wnt11 functions in gastrulation by controlling cell cohesion through Rab5c and E-cadherin. Dev Cell. 2005;9:555–564. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2005.08.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wallingford JB, Harland RM. Xenopus Dishevelled signaling regulates both neural and mesodermal convergent extension: parallel forces elongating the body axis. Development. 2001;128:2581–2592. doi: 10.1242/dev.128.13.2581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wallingford JB, Harland RM. Neural tube closure requires Dishevelled-dependent convergent extension of the midline. Development. 2002;129:5815–5825. doi: 10.1242/dev.00123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang J, Hamblet NS, Mark S, Dickinson ME, Brinkman BC, Segil N, Fraser SE, Chen P, Wallingford JB, Wynshaw-Boris A. Dishevelled genes mediate a conserved mammalian PCP pathway to regulate convergent extension during neurulation. Development. 2006a;133:1767–1778. doi: 10.1242/dev.02347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y, Guo N, Nathans J. The role of Frizzled3 and Frizzled6 in neural tube closure and in the planar polarity of inner-ear sensory hair cells. J Neurosci. 2006b;26:2147–2156. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4698-05.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Warga RM, Kimmel CB. Cell movements during epiboly and gastrulation in zebrafish. Development. 1990;108:569–580. doi: 10.1242/dev.108.4.569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Warrington SJ, Strutt H, Strutt D. The Frizzled-dependent planar polarity pathway locally promotes E-cadherin turnover via recruitment of RhoGEF2. Development. 2013;140:1045–1054. doi: 10.1242/dev.088724. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weaire D, Rivier N. Soap, cells and statistics - random patterns in two dimensions. Contemporary Physics. 1984;25:59–99. [Google Scholar]

- Williams-Masson EM, Heid PJ, Lavin CA, Hardin J. The cellular mechanism of epithelial rearrangement during morphogenesis of the Caenorhabditis elegans dorsal hypodermis. Dev Biol. 1998;204:263–276. doi: 10.1006/dbio.1998.9048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winter CG, Wang B, Ballew A, Royou A, Karess R, Axelrod JD, Luo L. Drosophila Rho-associated kinase (Drok) links Frizzled-mediated planar cell polarity signaling to the actin cytoskeleton. Cell. 2001;105:81–91. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(01)00298-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolff T, Rubin GM. Strabismus, a novel gene that regulates tissue polarity and cell fate decisions in Drosophila. Development. 1998;125:1149–1159. doi: 10.1242/dev.125.6.1149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ybot-Gonzalez P, Savery D, Gerrelli D, Signore M, Mitchell CE, Faux CH, Greene ND, Copp AJ. Convergent extension, planar-cell-polarity signalling and initiation of mouse neural tube closure. Development. 2007;134:789–799. doi: 10.1242/dev.000380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yen WW, Williams M, Periasamy A, Conaway M, Burdsal C, Keller R, Lu X, Sutherland A. PTK7 is essential for polarized cell motility and convergent extension during mouse gastrulation. Development. 2009 doi: 10.1242/dev.030601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yin C, Kiskowski M, Pouille PA, Farge E, Solnica-Krezel L. Cooperation of polarized cell intercalations drives convergence and extension of presomitic mesoderm during zebrafish gastrulation. J Cell Biol. 2008;180:221–232. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200704150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yin H, Copley CO, Goodrich LV, Deans MR. Comparison of phenotypes between different vangl2 mutants demonstrates dominant effects of the Looptail mutation during hair cell development. PLoS One. 2012;7:e31988. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0031988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zallen JA, Blankenship JT. Multicellular dynamics during epithelial elongation. Semin Cell Dev Biol. 2008;19:263–270. doi: 10.1016/j.semcdb.2008.01.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zallen JA, Wieschaus E. Patterned gene expression directs bipolar planar polarity in Drosophila. Dev Cell. 2004;6:343–355. doi: 10.1016/s1534-5807(04)00060-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zallen JA, Zallen R. Cell-pattern disordering during convergent extension in Drosophila. Journal of Physics: Condensed Matter. 2004;16:S5073–S5080. doi: 10.1088/0953-8984/16/44/005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.