Abstract

This study predicted all-cause mortality based on physical activity level (active or inactive) and waist circumference (WC) in 8208 Canadian adults in Alberta, Manitoba, Nova Scotia, and Saskatchewan, surveyed between 1986–1995 and followed through 2004. Physically inactive adults had higher mortality risk than active adults overall (hazard ratio, 95% confidence interval = 1.20, 1.05–1.37) and within the low WC category (1.51, 1.19–1.92). Detrimental effects of physical inactivity and high WC demonstrate the need for physical activity promotion.

Keywords: physical activity, inactivity, waist circumference, obesity, mortality

Introduction

Physical inactivity and excess adiposity contribute to premature all-cause mortality in adult men and women (Katzmarzyk et al. 2003). An inverse dose–response relationship between physical activity and mortality risk is established: increased levels of physical activity protect against mortality from cardiovascular disease (CVD) and certain cancers (Blair et al. 2001; Lee and Skerrett 2001). Conversely, excess abdominal adiposity increases the risk of cardiovascular and cancer death (Pischon et al. 2008) and may modify the protective effect of physical activity against premature mortality.

Physical activity was associated with lower mortality rates across all body mass index categories (underweight, normal weight, overweight, and obese) in Puerto Rican men (Crespo et al. 2002) and in middle-aged Swedish men (Rosengren and Wilhelmsen 1997). In contrast, a study of American adults found that physical activity was associated with lower mortality in non-obese men but not in obese men, and with lower mortality among younger women regardless of adiposity status (Dorn et al. 1999). Similarly, obese men had a higher mortality rate than normal-weight men regardless of physical activity level (sedentary, moderate, or intermediate–intense leisure-time physical activity) in a study from Norway (Meyer et al. 2002). It is therefore unclear how physical activity is associated with mortality risk across all levels of adiposity. Although waist circumference (WC) and body mass index are similarly highly correlated with total body fat (Bouchard 2007), few studies have examined physical activity level (active or inactive) and mortality across WC levels. The present study investigates the effects of physical activity on mortality across levels of WC among Canadian adults.

Materials and methods

Participants and survey design

The Canadian Heart Health Surveys (CHHS) were administered in Canadian provinces from 1986–1992 (MacLean et al. 1992), with a second survey administered in Nova Scotia in 1995, to measure CVD risk factors in a random sample of non-institutionalized adults. Of the original 8700 adults in the sample with full anthropometric data, participants were sequentially excluded based on the following criteria: older than 75 years (n = 434), missing physical activity information (n = 2), missing education level (n = 34), or missing alcohol consumption status (n = 3). Participants were also excluded if death occurred within 6 months of survey (n = 19) to limit bias from preexisting disease that may alter relevant risk factors (Joffres et al. 1990). Analyses were thus limited to 8208 participants who were 18–74 years old (4074 men) and resided in Alberta (n = 1966), Manitoba (n = 2258), Nova Scotia (n = 2258), and Saskatchewan (n = 1726).

Anthropometrics

WC was measured horizontally at the level of noticeable waist narrowing and at the end of a normal expiration among participants wearing light-weight clothing. When narrowing could not be determined, WC was measured at the estimated lateral level of the 12th or lower floating rib. Measurements were taken with an inelastic tape measure and rounded to the nearest centimetre. Participants were categorized into low, moderate, and high WC groups (for men, italic>94 cm, 94 to 101.9 cm, ≥102 cm, respectively; for women, bold>80 cm, 80 to 87.9 cm, ≥88 cm, respectively) (Lean et al. 1995).

Survey responses

During an in-home interview, participants reported whether or not they exercised regularly (1+ times a week) and whether or not their occupation required strenuous physical activity. Participants were classified as active or inactive. Active participants reported engagement in leisure-time or occupational activity at least once per week. Inactive participants were those participants who did not engage in leisure-time physical activity at least once per week and who did no strenuous physical activity at work.

Covariate information was also collected using an interviewer-administered questionnaire and included smoking status, alcohol consumption, and education. Smoking status was classified as (i) nonsmoker, (ii) former smoker, or (iii) current smoker; alcohol consumption was classified as (i) never, (ii) former, or (iii) current drinker; and educational attainment was coded as (i) elementary school or less, (ii) some secondary school, (iii) secondary school completed, or (iv) university degree completed.

Mortality ascertainment

To determine mortality status, the CHHS data were linked with the Canadian Mortality Database’s (CMDB’s) 1986–2004 files at Statistics Canada (Statistics Canada 2007). Computerized probabilistic matching was used to link CHHS observations with death registrations supplied by the provinces of residence, which yields a very small potential (ranging from 3% to 7%) for missed deaths (Schnatter et al. 1990; Shannon et al. 1989). All deaths that occurred between 6 months after CHHS survey completion and December 31, 2004, were included in the analyses. Cause of death was classified based on the International Classification of Diseases (ICD) code in effect at the time of death, including deaths from CVD (ICD-9: 390–448; ICD-10: I00-I78) and from cancer (ICD-9: 140–239; ICD-10: C00-D48). The institutional review boards of participating institutions provided ethics approval to link the CHHS data to the CMDB.

Statistical analyses

Baseline group differences between survivors and decedents were determined using t tests for continuous variables and χ2 tests for categorical variables. Cox proportional hazards models were used to estimate hazard ratios and 95% confidence (CIs) intervals for all-cause mortality overall and within WC categories for all respondents, then separately by sex. All models included age, and multivariate models also included examination year, smoking status, alcohol consumption, and education level. Analyses compared all-cause mortality rates across all activity-by-adiposity groups (active or inactive with low, moderate, or high WC) to the referent active-low WC group. Statistical tests were 2-sided, and statistical significance was accepted at p < 0.05. Analyses were conducted using SAS software (version 9.2; SAS Institute Inc., Cary, N.C., USA).

Results

There were 913 deaths among the 8208 participants during the follow-up period. There were 563 deaths in men (207 CVD, 202 cancer) and 350 deaths in women (115 CVD, 129 cancer). Average follow-up was 12.8 years for men (52 166 total person-years) and 13.2 years (54 545 total person-years) for women. As depicted in Table 1, for both men and women, decedents were older, less active, and had larger WC than survivors.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics (1985–1995) of 8208 adults in the Canadian Heart Health Surveys Follow-Up Study by survival status in 2004.

| Men

|

Women

|

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Survivors, n = 3511 | Decedents, n = 563 | pa | Survivors, n = 3784 | Decedents, n = 350 | pa | |

| Follow-up time, y | 13.5 (2.5) | 8.4 (4.0) | <0.0001 | 13.6 (2.5) | 9.0 (4.1) | <0.0001 |

| Age, y | 41.6 (16.1) | 64.7 (10.2) | <0.0001 | 42.3 (16.2) | 65.2 (10.0) | <0.0001 |

| Waist circumference, cm | 92.6 (12.2) | 98.8 (11.7) | <0.0001 | 79.9 (13.2) | 88.5 (14.9) | <0.0001 |

| WC category, %b | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | ||||

| Low | 55.5 | 34.3 | 56.5 | 29.1 | ||

| Moderate | 22.9 | 29.0 | 18.7 | 20.0 | ||

| High | 21.7 | 36.8 | 24.9 | 50.9 | ||

| Activity levelc | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | ||||

| Inactive | 30.8 | 39.4 | 30.2 | 41.4 | ||

| Active | 69.2 | 60.6 | 69.8 | 58.6 | ||

| Smoking status, % | <0.0001 | 0.699 | ||||

| Nonsmoker | 29.5 | 12.8 | 43.1 | 43.4 | ||

| Former smoker | 39.4 | 57.2 | 30.2 | 28.3 | ||

| Current smoker | 31.1 | 30.0 | 26.7 | 28.3 | ||

| Alcohol consumption, % | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | ||||

| Never drink | 1.8 | 1.8 | 4.3 | 14.6 | ||

| Former drinker | 11.3 | 21. 7 | 13.1 | 24.6 | ||

| Current drinker | 86.9 | 76.6 | 82.6 | 60.9 | ||

| Education, % | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | ||||

| Elementary school or less | 3.6 | 9.1 | 2.4 | 9.7 | ||

| Some elementary school | 26.3 | 52.0 | 25.9 | 46.9 | ||

| Secondary school completed | 49.6 | 30.2 | 54.0 | 32.3 | ||

| University degree completed | 20.5 | 8.7 | 17.8 | 11.1 | ||

Note: Data are means (SD) for continuous variables or percentages for nominal variables.

Difference in baseline characteristics between survivors and decedents, calculated by t test for continuous variables and χ2 test for categorical variables.

Risk status is classified as low, moderate, or high waist circumference risk (for men: <94 cm, 94 to 101.9 cm, ≥102 cm, respectively; for women: <80 cm, 80 to 87.9 cm, ≥88 cm, respectively).

Activity defined as Active = engaged in physical activity at least 1× per week during leisure-time or work; Inactive = did not engage in leisure-time physical activity at least once per week and did not engage in strenuous physical activity at work.

Multivariate-adjusted models revealed that inactive participants had a higher all-cause mortality risk than active participants (hazard ratio = 1.20 (95% CI: 1.05, 1.37)). The results of the sex-specific analyses are presented in Table 2. Inactive women had a higher all-cause mortality risk (1.28 (95% CI: 1.03, 1.59)) than active women.

Table 2.

Hazard ratio of all-cause mortality associated with activity by waist circumference category in 8208 adults in the Canadian Heart Health Surveys Follow-up Study.

| P-y | No. | Deaths | HRa | 95% CI | HRb | 95% CI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Men | |||||||

| Activityc | |||||||

| Active | 35 515 | 1408 | 340 | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||

| Inactive | 16 651 | 1302 | 222 | 1.20 | 1.01, 1.42 | 1.15 | 0.97, 1.36 |

| Low WCd | |||||||

| Active | 20 318 | 1539 | 115 | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||

| Inactive | 7 940 | 602 | 78 | 1.51 | 1.13, 2.01 | 1.42 | 1.06, 1.90 |

| Moderate WCd | |||||||

| Active | 8 004 | 640 | 103 | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||

| Inactive | 4 181 | 326 | 60 | 1.12 | 0.82, 1.54 | 1.10 | 0.80, 1.52 |

| High WCd | |||||||

| Active | 7 193 | 593 | 123 | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||

| Inactive | 4 530 | 374 | 84 | 0.99 | 0.75, 1.31 | 0.97 | 0.73, 1.28 |

| Women | |||||||

| Activityc | |||||||

| Active | 37 702 | 2847 | 205 | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||

| Inactive | 16 843 | 1287 | 145 | 1.39 | 1.12, 1.71 | 1.28 | 1.03, 1.59 |

| Low WCd | |||||||

| Active | 22 009 | 1633 | 68 | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||

| Inactive | 8 205 | 605 | 34 | 1.67 | 1.10, 2.52 | 1.59 | 1.05, 2.42 |

| Moderate WCd | |||||||

| Active | 6 866 | 520 | 45 | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||

| Inactive | 3 419 | 256 | 25 | 0.96 | 0.59, 1.56 | 0.93 | 0.56, 1.52 |

| High WCd | |||||||

| Active | 8 828 | 694 | 92 | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||

| Inactive | 5 219 | 426 | 86 | 1.33 | 0.99, 1.78 | 1.23 | 0.91, 1.66 |

Note: P-y, total person-years; CI, confidence interval; WC, waist circumference.

Hazard ratio for age-adjusted model.

Hazard ratio for multivariate model adjusted for age, smoking, alcohol consumption, and education.

Activity defined as Active = engaged in physical activity at least 1× per week during leisure-time or work; Inactive = did not engage in leisure-time physical activity at least once per week and did not engage in strenuous physical activity at work.

Low, moderate, and high WC is defined for men, <94 cm, 94 to 101.9 cm, ≥102 cm, respectively; for women, <80 cm, 80 to 87.9 cm, ≥ 88 cm, respectively.

For individuals with low WC, inactive adults had a higher all-cause mortality risk (1.51 (95% CI: 1.19, 1.92)) than active adults. The same pattern held for men and women separately. For individuals with moderate or high WC, there was no significant effect of activity status on all-cause mortality overall or within sex when compared within each WC category.

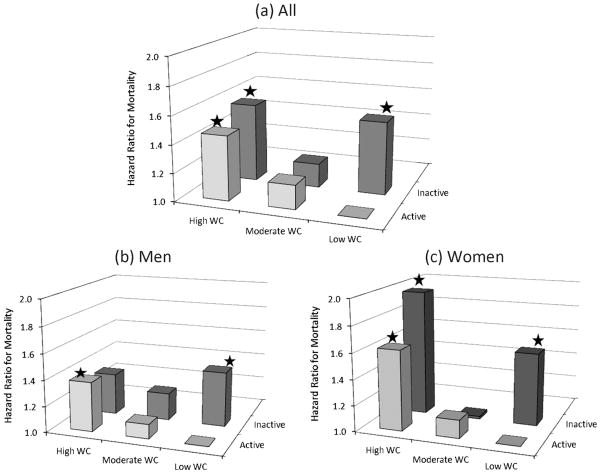

Activity-by-adiposity groups were compared against the referent active-low WC group. Overall, inactive-low WC (1.52 (95% CI: 1.20–1.92)), inactive-high WC (1.56 (95% CI: 1.26–1.93)), and active-high WC (1.46 (95% CI: 1.20–1.79)) groups had higher all-cause mortality risk than active-low WC adults. Sex-specific analyses revealed a similar pattern (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Hazard ratios for all-cause mortality by waist circumference (WC) and physical activity level for (a) all, (b) men, and (c) women. *, Significant difference from reference group, p < 0.05. Hazard ratio is adjusted for age, smoking, alcohol consumption, and education. WC is classified as low, moderate, and high (for men: <94 cm, 94 to 101.9 cm, ≥102 cm, respectively; for women: <80 cm, 80 to 87.9 cm, ≥88 cm, respectively). Activity level is defined as Active = engaged in physical activity at least 1× per week during leisure-time or work; Inactive = did not engage in leisure-time physical activity at least once per week and did not engage in strenuous physical activity at work.

Discussion

The results of this study indicate that both WC and physical activity level are related to all-cause mortality in men and women, though different relationships emerged across WC groups. Men and women with a low WC had a higher mortality risk if they were inactive than those who engaged in an active level of physical activity at least 1 time per week. In contrast, within elevated (moderate and high) WC categories, there were no significant associations between mortality and physical activity level of at least 1 time per week. Prior findings produced mixed results, with some studies demonstrating no association between physical activity level and mortality for overweight and obese men (Dorn et al. 1999; Meyer et al. 2002) and other studies finding lower mortality rates from physical activity across all body mass index (Crespo et al. 2002; Rosengren and Wilhelmsen 1997) and waist circumference (Bellocco et al. 2010) categories. The present findings reveal that for adults who have elevated WC, being physically active at least once per week did not confer protection against premature mortality compared with inactive counterparts who also had elevated WC.

Many studies have found no association between physical activity and mortality in women (Kampert et al. 1996; Lee et al. 2011). In contrast, prospective studies of Canadian women (Katzmarzyk and Craig 2006) and Swedish women (Bellocco et al. 2010) demonstrated an independent contribution of both physical inactivity and high WC for premature mortality, and a 29-year prospective study found protective effects of physical activity for women and not for men (Dorn et al. 1999). Indeed, the present findings indicate that both men and women who are active have lower mortality rates than inactive men and women. Notably, the association changed based on adiposity level, where being inactive was associated with increased mortality risk for adults within the low WC category but not for adults within elevated WC categories (Table 2).

The protective benefits of physical activity against mortality may be weakened by the detrimental health consequences of excess adiposity (Dorn et al. 1999). Results from the Aerobics Center Longitudinal Study suggest that physical fitness can negate some if not all of the effects of obesity on premature mortality (Lee et al. 1999). Although our analysis used physical activity rather than physical fitness, the hazard ratios in the inactive-low WC (1.52 (95% CI: 1.20–1.92)) and active-high WC (1.46 (95% CI: 1.20–1.79)) groups were similar in magnitude, indicating a similar result. Individuals with moderate WC did not differ in mortality risk from the active-low WC group, regardless of activity level (Fig. 1). It may be that moderate adiposity is not sufficient to increase mortality risk, whereas excessive adiposity in the high WC group did produce higher mortality risk.

There are several putative mechanisms whereby physical activity reduces the risk of mortality. For example, physical activity protects against cardiovascular disease by reducing dyslipidemia and hypertension and by improving endothelial function (Hardman and Stensel 2009). Physical activity also reduces cancer risk by systemic improvements in metabolic hormone circulation, body fat and immunity, as well as reduced sex steroid hormones and reduced bowel transit time (Hardman and Stensel 2009). Yet in the present study, physical activity only protected adults with low WC, indicating that the excess adipose tissue in adults with moderate to high WC overrides the protective effects of physical activity. Visceral fat in the abdomen is particularly associated with insulin resistance and dyslipidemia (Kuk et al. 2006). Therefore WC, as a clinical measure of total and abdominal fat, demonstrates a strong relationship with adverse health outcomes that contribute to mortality.

A major strength of this study is the use of directly measured WC. WC is highly correlated with both total and abdominal adiposity (Bouchard 2007) and is a robust predictor of all-cause mortality (Katzmarzyk et al. 2003). Future research employing magnetic resonance imaging or computed tomography would provide more precise analysis of how body fat in specific depots predicts mortality. Other strengths of this study include the large population-based sample of men and women followed for an average of 13 years, and the reliable link to the CMDB to determine the outcomes.

An important limitation of this study is the lack of detailed information on physical activity. The CHHS survey assessed strenuous activity at least once per week but did not quantify number of days per week of physical activity. Therefore, it is not possible to determine if individuals with an elevated WC were more likely to be active only once per week versus those with a low WC. Additionally, the physical activity level of at least once per week may not meet current Canadian Physical Activity Guidelines for adults, which are at least 150 min of moderate- to vigorous-intensity physical activity per week (Canadian Society for Exercise Physiology 2011). Studies that employ more specific characterizations of typical physical activity levels and patterns are needed, including how frequency and duration of physical activity level contribute to risk for mortality. Potential misclassification may reduce the chances of detecting significant associations related to physical activity. Different classification schemes for physical activity may also impact comparisons between studies. Despite the broad definition for physical activity employed in this study, any amount of activity still protected low WC adults.

In conclusion, the results of this study demonstrated that physical inactivity and higher WC relate to all-cause mortality in men and women. Inactive adults had a higher risk of mortality than active adults among individuals with low WC. The association of physical activity level and WC with mortality risk has clinical and public health implications and reinforces the need to promote increased physical activity in the population.

Acknowledgments

Special thanks to Alison Edwards for assistance with data management. This research was supported by a New Emerging Team grant from the Heart and Stroke Foundation of Canada and the Canadian Institutes of Health Research. P.T.K. is partially supported by the Louisiana Public Facilities Authority Endowed Chair in Nutrition. The funding source had no involvement in the study design; in the collection, analysis, and interpretation of data; in the writing of the report; or in the decision to submit the paper for publication. Necessary ethics committee approval was secured for the study reported.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Contributor Information

Amanda E. Staiano, Pennington Biomedical Research Center, 6400 Perkins Road, Baton Rouge, LA 70808-4124, USA

Bruce A. Reeder, Department of Community Health and Epidemiology, University of Saskatchewan, Saskatoon, SK S7N 5E5, Canada

Susan Elliott, Faculty of Applied Health Sciences, University of Waterloo, Waterloo, ON N2L 3G1, Canada.

Michel R. Joffres, Faculty of Health Sciences, Simon Fraser University, Burnaby, BC V5A 1S6, Canada

Punam Pahwa, Department of Community Health and Epidemiology, University of Saskatchewan, Saskatoon, SK S7N 5E5, Canada.

Susan A. Kirkland, Department of Community Health and Epidemiology, Dalhousie University, Halifax, NS B3H 1V7, Canada

Gilles Paradis, Department of Epidemiology, Biostatistics and Occupational Health, McGill University, Montreal, QC H3A 1A2, Canada.

Peter T. Katzmarzyk, Pennington Biomedical Research Center, 6400 Perkins Road, Baton Rouge, LA 70808-4124, USA

References

- Bellocco R, Jia C, Ye W, Lagerros YT. Effects of physical activity, body mass index, waist-to-hip ratio and waist circumference on total mortality risk in the Swedish National March Cohort. Eur J Epidemiol. 2010;25(11):777–788. doi: 10.1007/s10654-010-9497-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blair S, Cheng Y, Holder S. Is physical activity or physical fitness more important in defining health benefits? Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2001;33(6 Suppl):S379–S399. doi: 10.1097/00005768-200106001-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bouchard C. BMI, fat mass, abdominal adiposity and visceral fat: Where is the ‘beef’? Int J Obes. 2007;31(10):1552–1553. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0803653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Canadian Society for Exercise Physiology. [Accessed 22 February 2012];Canadian Physical Activity Guidelines. 2011 Available from www.csep.ca/guidelines.

- Crespo CJ, Palmieri MR, Perdomo RP, Mcgee DL, Smit E, Sempos CT, et al. The relationship of physical activity and body weight with all-cause mortality: Results from the Puerto Rico Heart Health Program. Ann Epidemiol. 2002;12(8):543–552. doi: 10.1016/S1047-2797(01)00296-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dorn JP, Cerny FJ, Epstein LH, Naughton J, Vena JE, Winkelstein W, Jr, et al. Work and leisure time physical activity and mortality in men and women from a general population sample. Ann Epidemiol. 1999;9(6):366–373. doi: 10.1016/S1047-2797(99)00025-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hardman AE, Stensel DJ. Physical activity and health: The evidence explained. Routledge; New York, N.Y., USA: 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Joffres MR, MacLean CJ, Reed DM, Yano K, Benfante R. Potential bias due to prevalent diseases in prospective studies. Int J Epidemiol. 1990;19(2):459–465. doi: 10.1093/ije/19.2.459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kampert JB, Blair SN, Barlow CE, Kohl HW., III Physical activity, physical fitness, and all-cause and cancer mortality: A prospective study of men and women. Ann Epidemiol. 1996;6(5):452–457. doi: 10.1016/S1047-2797(96)00059-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katzmarzyk PT, Craig CL. Independent effects of waist circumference and physical activity on all-cause mortality in Canadian women. Appl Physiol Nutr Metab. 2006;31(3):271–276. doi: 10.1139/h05-038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katzmarzyk PT, Janssen I, Ardern CI. Physical inactivity, excess adiposity and premature mortality. Obes Rev. 2003;4(4):257–290. doi: 10.1046/j.1467-789X.2003.00120.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuk JL, Katzmarzyk PT, Nichaman MZ, Church TS, Blair SN, Ross R. Visceral fat is an independent predictor of all-cause mortality in men. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2006;14(2):336–341. doi: 10.1038/oby.2006.43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lean ME, Han TS, Morrison CE. Waist circumference as a measure for indicating need for weight management. BMJ. 1995;311(6998):158–161. doi: 10.1136/bmj.311.6998.158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee CD, Blair SN, Jackson AS. Cardiorespiratory fitness, body composition, and all-cause and cardiovascular disease mortality in men. Am J Clin Nutr. 1999;69(3):373–380. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/69.3.373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee DC, Sui X, Ortega FB, Kim YS, Church TS, Winett RA, Ekelund U, et al. Comparisons of leisure-time physical activity and cardiorespiratory fitness as predictors of all-cause mortality in men and women. Br J Sports Med. 2011;45(6):504–510. doi: 10.1136/bjsm.2009.066209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee IM, Skerrett PJ. Physical activity and all-cause mortality: What is the dose-response relation? Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2001;33(6 Suppl):S459–S471. doi: 10.1097/00005768-200106001-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacLean DR, Petrasovits A, Nargundkar M, Connelly PW, MacLeod E, Edwards A, Hessel P Canadian Heart Health Surveys Research Group. Canadian Heart Health Surveys: A profile of cardiovascular risk. Survey methods and data analysis. CMAJ. 1992;146(11):1969–1974. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyer HE, Søgaard AJ, Tverdal A, Selmer RM. Body mass index and mortality: The influence of physical activity and smoking. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2002;34(7):1065–1070. doi: 10.1097/00005768-200207000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pischon T, Boeing H, Hoffmann K, Bergmann M, Schulze MB, Overvad K, et al. General and abdominal adiposity and risk of death in Europe. N Engl J Med. 2008;359(20):2105–2120. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0801891. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosengren A, Wilhelmsen L. Physical activity protects against coronary death and deaths from all causes in middle-aged men. Evidence from a 20-year follow-up of the primary prevention study in Goteborg. Ann Epidemiol. 1997;7(1):69–75. doi: 10.1016/S1047-2797(96)00106-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schnatter AR, Acquavella JF, Thompson FS, Donaleski D, Theriault G. An analysis of death ascertainment and follow-up through Statistics Canada’s Mortality Database System. Can J Public Health. 1990;81(1):60–65. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shannon HS, Jamieson E, Walsh C, Julian JA, Fair ME, Buffet A. Comparison of individual follow-up and computerized linkage using the Canadian Mortality Data Base. Can J Public Health. 1989;80(1):54–57. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Statistics Canada. Vital statistics – death database: Detailed information for 2005. Statistics Canada; Ottawa, Ont., Canada: 2007. [Accessed 7 February 2011]. Available from www.statcan.gc.ca/ [Google Scholar]