Summary

The clinical, haematological, molecular and treatment data of eight paediatric patients with polycythemia vera (PV) were collected prospectively. One patient developed PV after treatment for large-cell anaplastic lymphoma. Budd-Chiari syndrome was diagnosed in two patients, necessitating orthotopic liver transplantation in one and transjugular portosystemic shunting in the other. The remaining patients presented with non-specific symptoms. Endogenous erythroid colonies were detected in all cases examined. The JAK2V617F mutation was found in six patients; two patients displayed JAK2 exon 12 mutations, including one novel mutation (JAK2H538-K539delinsI). CD177 (PRV-1) mRNA expression was increased in three of five patients tested.

Keywords: polycythemia vera, erythrocytosis, childhood, molecular analysis, Budd-Chiari syndrome

Erythrocytoses constitute a group of extremely rare diseases in paediatric and juvenile patients. Primary erythrocytoses comprise both congenital erythrocytoses caused, for example, by erythropoietin (Epo)-receptor gene (EPOR) mutations and the acquired myeloproliferative disorder polycythemia vera (PV). PV patients present with a median age of 60 years; only about 1 in 1000 patients presenting with PV is younger than 20 years. Therefore, published data on clinical and laboratory characteristics and on treatment modalities of paediatric PV patients are sparse.

Within the framework of a collaborative registry, we collected clinical, haematological and treatment data of children and adolescents with PV. In addition, we assessed the formation of endogenous erythroid colonies (EEC), the granulocyte CD177 (PRV-1) mRNA expression and the presence of an acquired JAK2 mutation in these patients.

Design and methods

The diagnostic process and the assessment of anamnestic, clinical, haematological, biochemical and molecular data followed an algorithm based on the protocol of the registry on PV and Congenital Erythrocytoses in Childhood and Adolescence, PV-ERY-KA 03. All patients (and/or parents) gave their written informed consent to the molecular genetic analysis, data analysis and publication. The study was approved by the local University ethics committee and performed in accordance with the World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki of 1975, as revised in 2000.

Endogenous erythroid colonies assay and CD177 mRNA quantification were performed as previously described (Griesshammer et al, 2004). Allele-specific polymerase chain reactions (PCRs) to detect the JAK2V617F mutation were performed as previously reported with modifications of the allele-specific primer (Baxter et al, 2005). JAK2 exon 12.cDNA from patients 5 and 7 (JAK2V617F negative) was amplified by PCR. Amplified PCR fragments from patient 5 were cloned into pcDNA 2·1. DNA from 16 individual clones was sequenced. PCR fragments from patient 7 underwent direct sequencing analysis. Details and primer sequences are available upon request.

Results and discussion

Eight patients with PV (five female, three male) with a median age at onset of 12·5 years (range 6–17 years) were included. Some of the clinical and haematological data of two patients (patients 1 and 3) were reported previously (Cario et al, 2003; Reinhard et al, 2008). The data of these patients are summarized, included in the cohort analysis and complemented by new molecular data.

The majority of patients presented with non-specific symptoms or with an acute illness not related to PV (Table I). Patient 3 presented with ascites because of Budd-Chiari syndrome (BCS) subsequently necessitating orthotopic liver transplantation (Cario et al, 2003). At present, 7 years later, the patient is in an excellent physical condition. Patient 7 had a history of intermittent headache and was diagnosed with PV after several syncopal episodes at the age of 12 years. Two years later, the patient presented with hepatosplenomegaly and ascites caused by BCS. She was treated with streptokinase, heparin and warfarin. Because of subsequent development of esophageal varices, transjugular portosystemic shunting was performed and led to a substantial decrease of the portal vein pressure followed by regression of hepatosplenomegaly. Screening for hereditary thrombophilic risk factors revealed heterozygosity for F5 R506Q (factor V Leiden) and a heterozygous F2 G20210A mutation.

Table I.

Clinical, haematological and molecular data of paediatric PV patients.

| Patient no. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | Median |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age at onset (years) | 9 | 6 | 11 | 13 | 16 | 13 | 12 | 17 | 10 |

| Gender | M | M | F | F | F | F | F | M | |

| Clinical symptoms at first presentation |

Appendicitis, plethora |

Gastroenteritis | BCS | Headache | Pruritus, tinnitus, dizziness |

Migraine | Headache, syncope (later BCS) |

Lassitude, loss of weight, abdominal pain |

|

| Haemoglobin (g/l) | 211 | 182 | 180 | 159 | 155 | 165 | 195 | 194 | 181 |

| Haematocrit (l/l) | 0·73 | 0·60 | 0·64 | 0·49 | 0·59 | 0·53 | 0·63 | 0·60 | 0·60 |

| Erythrocytes (× 1012/l) | 9·2 | 9T | 8·4 | 6·4 | 6·8 | 10·2 | 6·9 | 8·4 | |

| MCV (fl) | 71 | 66 | 76 | 76 | 93 | 77 | 62 | 87 | 76 |

| MCH (pg) | 23 | 20 | 21·5 | 24 | 24 | 28 | 23·5 | ||

| Reticulocytes (%) | 1·5 | 1·1 | 2·4 | 1·3 | 1·2 | 0·8 | 1·9 | 1·3 | |

| Leucocytes (× 109/l) | 8·6 | 8·8 | 22·2 | 10·3 | 5·0 | 12·8 | 8·2 | 8·3 | 8·7 |

| Thrombocytes (× 109/l) | 580 | 494 | 597 | 938 | 361 | 866 | 480 | 682 | 588 |

| Erythropoietin (U/l) | <5 | <2·5 | 10·6 | 4·3 | <3 | <2·5 | 3·1 | 1·8 | |

| EEC growth | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | ||

| CD177 mRNA | + | + | (+) | + | − | ||||

| JAK2 mutation | V617F | V617F | V617F | V617F | H538-K539delinsl | V617F | N542-E543del | V617F | |

| Bone marrow histology | |||||||||

| Cellularity | ++ | + | ++ | + | + | + | nl. | ++ | |

| Erythropoiesis | ++ | (+) | ++ | + | (+) | + | (+) | + | |

| Myelopoiesis | nl.* | nl. | + | + | (+) | nl.* | nl. | + | |

| Erythro-/Myelopoiesis | + | nl. | + | nl. | nl. | nl. | (+) | + | |

| Megakaryopoiesis | nl. | + | + | ++ | nl. | + | nl. | ++ | |

| Iron content | nl. | − | − | − | nl. | − | |||

| Treatment | MURD-SCT | Phlebotomy | HC, ASA | ASA | Phlebotomy, ASA | IFN-α, ASA | IFN-α, ASA | Phlebotomy, ASA |

BCS, Budd-Chiari syndrome; EEC, endogenous erythroid colonies; MURD-SCT, matched unrelated donor stem cell transplantation; HC, hydroxycarbamide; ASA, acetylsalicylic acid; IFN-α, interferon α.

Shifted to immature cells.

Budd-Chiari syndrome is a rare but typical complication in PV. Both the published paediatric PV cases and our cohort suggest a high prevalence of BCS in paediatric patients. In addition to the 25% affected in our cohort, five previously reported paediatric PV presented with BCS, which was the cause of death in two of them (Roth et al, 1990; Cobo et al, 1996; Melear et al, 2002; Sutherland et al, 2004). Likewise, several studies reported a comparable BCS prevalence in young adult patients (see Cario et al, 2003). BCS led to the diagnosis of PV in the majority of patients affected by this complication. One may postulate that both paediatric and young adult patients may have a particular predisposition to develop BCS.

Patient 5, a 15-year-old girl, was diagnosed with erythrocytosis during routine follow-up 2 years after treatment for large-cell anaplastic lymphoma diagnosed at 13 years of age. Treatment according to the NHL-BFM 1995 protocol led to stable complete remission. The patient presented with mild symptoms of dizziness, reported an episode of tinnitus and occasional aquagenous pruritus.

Only very few cases of ‘secondary’ PV after treatment of a haematological malignancy are published. Thus, it is remarkable that, in addition to our patient with NHL, two previously published children with PV had a history of acute lymphoblastic leukaemia (Hann et al, 1979; Sutherland et al, 2004). Regarding the huge number of surviving children and adults treated for either lymphoma or leukaemia and the very low number of patients later affected by PV, the most reasonable explanation for secondary PV in these cases is coincidence by chance. Nevertheless, the fact that this coincidence is found ‘predominantly’ in children in whom PV per se is very rare is noteworthy. Elucidation of the alteration predisposing to the development of a myeloproliferative disorder (MPD) as well as characterization of the MPD initiating change in these patients may also contribute to a better understanding of the pathogenesis of ‘sporadic PV’.

Similar to adult patients, the haematological presentation of children and adolescents with PV is also heterogeneous (Table I). Thrombocytosis with platelets >400 × 109/l, as commonly found in previously published patients, was present in seven of our eight patients. In contrast, only two of our patients had a leucocyte count >12 × 109/l, one of them with leucocytes >20 × 109/l. Leucocytosis was likewise rare in previously reported childhood PV cases. Bone marrow histology revealed an increased erythropoiesis and myelopoiesis and an increased and partially dysmorphic megakaryopoiesis of varying degree in all patients (Table I). Cytogenetic analyses were normal in all cases.

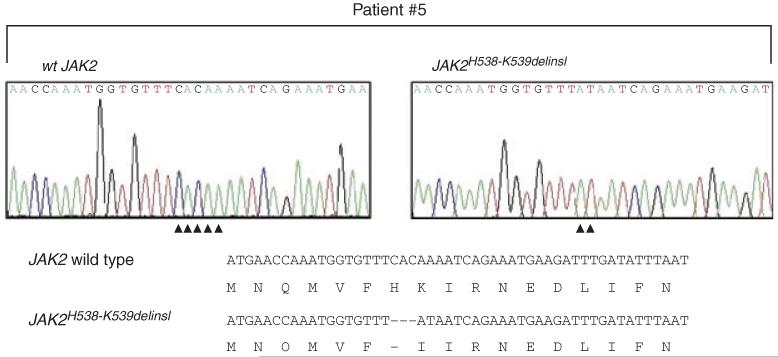

Serum erythropoietin was below the normal range in seven of eight patients. One of the patients with BCS had a normal serum Epo concentration despite a high haematocrit. Granulocyte CD177 mRNA expression was examined in five of eight untreated patients. It was significantly increased in three of five, borderline in one of five and normal in one patient. EEC growth was examined in seven of eight patients, with positive results in all cases. Molecular genetic analysis revealed a JAK2V617F mutation in six of the eight patients. A novel JAK2 Exon 12 mutation (JAK2H538-K539delinsI, Fig 1) was detected in patient 5, while in patient 7 a previously reported Exon 12 mutation (JAK2N542-E543del; Scott et al, 2007) was found.

Fig 1.

JAK2 Exon 12 sequence analysis in patient 5. Panels on the top show sequence traces of a clone displaying wild type (left) and mutant (right) JAK2 alleles. The compilation at the bottom shows the resulting alteration in the JAK2 protein sequence.

Our results are in contrast to those of a recently reported cohort of eight sporadic and five familial paediatric PV cases (Teofili et al, 2007). In this series, only three patients had a JAK2V617F mutation, none of them a JAK2 Exon 12 mutation, only four displayed EEC growth, only two had a serum Epo level below the normal range. The authors concluded that the recently proposed revised WHO diagnostic criteria (Tefferi et al, 2007) would not be applicable to children with myeloproliferative disorders. We actually found molecular changes comparable to those detectable in adult patients in all paediatric patients. Nevertheless, we agree that independent of the patient’s age, the minor diagnostic criterion of low serum Epo should be regarded with caution. Normal Epo levels were found in one of our patients, in the paediatric patients reported by Teofili et al (2007) as well as in adult PV patients, underlining that normal Epo levels do not exclude a diagnosis of PV.

Treatment of our PV patients included phlebotomy, aspirin, hydroxycarbamide and interferon-alpha (Table I). Patient 1 underwent successful stem cell transplantation from a matched unrelated donor (MURD-SCT) after treatment with phlebotomy and interferon-alpha prior to SCT (Reinhard et al, 2008). All patients are currently in a stable clinical and haematological condition.

Because of the long period over which the articles were published, treatment of previously reported patients varied enormously. Thus, it is currently not possible to treat an individual paediatric PV patient with an evidence-based regimen. However, the occurrence of BCS and other thrombotic and haemorrhagic complications in paediatric PV patients clearly indicates that PV in childhood and adolescence is a serious disorder. Thus, a close international co-operation of physicians and institutions is necessary to improve the medical care for these patients and to investigate the particular concerns of paediatric PV patients. These include the molecular event that triggers early disease manifestation, the presumed particular predisposition of young patients to BCS and the apparent predominance of children among patients with the very rare event of secondary PV cases after previous treatment for malignancy.

Acknowledgements

The authors are very grateful to Melanie Percy, Department of Haematology, Belfast City Hospital, Belfast and Elisabeth Kohne, Department of Paediatrics, University Hospital Ulm, for continuous close and fruitful cooperation and support. The authors also like to thank Jana Markova, Institute of Haematology and Blood Transfusion, Prague, for the genetic analysis in the Czech patient and Marina Jans, Institute for Clinical Transfusion Medicine and Immunogenetics, Ulm, for her excellent laboratory work.

The work of DP was supported by the Ministry of Health of the Czech Republic (Grant NR9471-3). H.L.P. is a member of the MPD Research Consortium and was supported by a grant from the National Cancer Institute (1 PO1 CA108671) and by the DFG (Pa611/5-1).

Footnotes

Conflict of interest

The authors have no conflict of interest to disclose.

References

- Baxter EJ, Scott LM, Campbell PJ, East C, Fourouclas N, Swanton S, Vassiliou GS, Bench AJ, Boyd EM, Curtin N, Scott MA, Erber WN, Green AR. Acquired mutation of the tyrosine kinase JAK2 in human myeloproliferative disorders. Lancet. 2005;365:1054–1061. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)71142-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cario H, Pahl HL, Schwarz K, Galm C, Hoffmann M, Burdelski M, Kohne E, Debatin K-M. Familial polycythemia vera with Budd-Chiari syndrome in childhood. British Journal of Haematology. 2003;123:346–352. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2141.2003.04591.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cobo F, Cervantes F, Garcia-Pagan JC, Bosch J, Rozman C, Montserrat E. Budd-Chiari syndrome associated with chronic myeloproliferative syndromes: analysis of 6 cases. Medicina Clinica (Barcelona) 1996;107:660–663. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Griesshammer M, Klippel S, Strunck E, Temerinac S, Mohr U, Heimpel H, Pahl HL. PRV-1 mRNA expression discriminates two types of essential thrombocythemia. Annals of Hematology. 2004;83:364–370. doi: 10.1007/s00277-004-0864-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hann HW, Festa RS, Rosenstock JG, Cifuentes E. Polycythemia vera in a child with acute lymphocytic leukemia. Cancer. 1979;43:1862–1865. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(197905)43:5<1862::aid-cncr2820430540>3.0.co;2-k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Melear JM, Goldstein RM, Levy MF, Molmenti EP, Cooper B, Netto GJ, Klintmalm GB, Stone MJ. Hematologic aspects of liver transplantation for Budd-Chiari syndrome with special reference to myeloproliferative disorders. Transplantation. 2002;74:1090–1095. doi: 10.1097/00007890-200210270-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reinhard H, Klingebiel T, Lang P, Bader P, Niethammer D, Graf N. Stem cell transplantation for polycythemia vera. Pediatric Blood Cancer. 2008;50:124–126. doi: 10.1002/pbc.20906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roth M, Haag K, Krause T, Blum U, Hellerich U. Aszites und Splenomegalie im Kindesalter. Medizinische Klinik (Munich) 1990;85:529–532. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scott LM, Tong W, Levine RL, Scott MA, Beer PA, Stratton MR, Futreal PA, Erber WN, McMullin MF, Harrison CN, Warren AJ, Gilliland DG, Lodish HF, Green AR. JAK2 exon 12 mutations in polycythemia vera and idiopathic erythrocytosis. New England Journal of Medicine. 2007;356:459–468. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa065202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sutherland ND, Gonzalez-Peralta R, Douglas-Nikitin V, Hunger SP. Polycythemia vera in a child following treatment for acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Journal of Pediatric Hematology and Oncology. 2004;26:315–319. doi: 10.1097/00043426-200405000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tefferi A, Thiele J, Orazi A, Kvasnicka HM, Barbui T, Hanson CA, Barosi G, Verstovsek S, Birgegard G, Mesa R, Reilly JT, Gisslinger H, Vannucchi AM, Cervantes F, Finazzi G, Hoffman R, Gilliland DG, Bloomfield CD, Vardiman JW. Proposals and rationale for revision of the World Health Organization diagnostic criteria for polycythemia vera, essential thrombocythemia, and primary myelofibrosis: recommendations from an ad hoc international expert panel. Blood. 2007;110:1092–1097. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-04-083501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teofili L, Giona F, Martini M, Cenci T, Guidi F, Torti L, Palumbo G, Amendola A, Leone G, Foa R, Larocca LM. The revised WHO diagnostic criteria for Ph-negative myeloproliferative diseases are not appropriate for the diagnostic screening of childhood polycythemia vera and essential thrombocythemia. Blood. 2007;110:3384–3386. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-06-094276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]