Abstract

Objectives

To further identify the single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) that contribute to the genetic susceptibility to sarcoidosis, we examined the potential association between sarcoidosis and 15 SNPs of the ANXA11 gene.

Design

A case–control study.

Setting

A tuberculosis unit in a hospital of the university in China.

Participants

Participants included 412 patients with sarcoidosis and 418 healthy controls.

Methods

The selected SNPs were genotyped using the MALDI-TOF in the MassARRAY system.

Results

Statistically significant differences were found in the allelic or genotypic frequencies of the rs2789679, rs1049550 and rs2819941 in the ANXA11 gene between patients with sarcoidosis and controls. The rs2789679 A allele (p=0.00004, OR=1.42, 95% CI 1.17 to 1.73) and rs2819941 T allele (p=0.0006, OR=1.41, 95% CI 1.16 to 1.71) were significantly more frequent in patients with sarcoidosis compared with controls. The frequency of the rs1049550 T allele (p=0.000002, OR=0.61, 95% CI 0.49 to 0.74) in patients with sarcoidosis was significantly lower than that in controls. The multi-SNP model reveals that rs1049550 is the only independent SNP association effect after accounting for the other two marginally associated SNPs. In block 2 (rs1049550–rs2573351), the T–C haplotype occurred significantly less frequently (p=0.001), whereas the C–C haplotypes occurred more frequently (p=0.0001) in patients with sarcoidosis than controls. Furthermore, genotype frequency distribution revealed that, in rs1049550, the CC genotype was significantly more in patients with chest X-ray (CXR) stage I sarcoidosis than in patients with CXR stage II–IV sarcoidosis (p=0.012).

Conclusions

These findings point to a role for the polymorphisms of ANXA11 in sarcoidosis in a Chinese Han population, and may be informative for future genetic studies on sarcoidosis.

Keywords: GENETICS, IMMUNOLOGY, INFECTIOUS DISEASES

Strengths and limitations of this study.

A systematical screening of the functional single-nucleotide polymorphisms in the promoter region, 5′-UTR (untranslated region) and 3′-UTR, exons of the ANXA11 gene, and the homogeneity of study participants representing the Chinese Han are the main strengths of this study.

The lack of data proving the positive association observed for rs2789679 and rs1049550 is a potential limitation of this study. Furthermore, the association of the serum level of ANXA11 with sarcoidosis still needs to be investigated.

Furthermore, the deficient study that investigates the association of the protein level of ANXA11 with sarcoidosis is a potential limitation of this study.

Introduction

Sarcoidosis is a systemic autoimmune disease characterised by destructive, non-caseating epithelioid granulomatous lesions, with accumulated phagocytes and activated CD4 T helper type 1 lymphocytes.1 2 The typical manifestations of sarcoidosis include bilateral hilar lymphadenopathy, pulmonary infiltration and ocular and skin lesions. The clinical course and prognosis of sarcoidosis are variable. In most cases, the acute type of sarcoidosis such as Löfgren’s syndrome can resolve spontaneously. However, chronic pulmonary sarcoidosis may progress to lung fibrosis, which eventually causes respiratory failure. Recent studies have demonstrated that sarcoidosis can occur in a pattern of family clustering, and its racial incidence is also different, suggesting that some genetic factors may contribute to the risk and severity of sarcoidosis.1 3

The Annexin gene family is involved in the aetiology of several autoimmune and chronic diseases.4 5 One member of the Annexin gene family, ANXA11, located on chromosome 10q22.3, is involved in calcium signalling, apoptosis, vesicle trafficking, cell growth and the terminal phase of cell division.5–7 In this context, the development and maintenance of the granulomatous inflammation in sarcoidosis have been repeatedly associated with the impaired apoptosis of activated inflammatory cells.8 9 Most of the early-stage sarcoidosis is characterised by mononuclear cell alveolitis dominated by activated CD4 T cells and macrophages. Between these cells, the uncoordinated interplay results in the formation of typical non-caseating granulomas. The mechanism by which the granulomas resolve has not been fully elucidated. However, it is generally assumed that apoptosis and the withdrawal of inflammatory cytokines are involved in the disappearance of granulomas.10 11 In patients with sarcoidosis, their peripheral blood monocytes were characterised by apoptosis.9

In previous studies, case–control/family ‘hypothesis-driven’ studies and low density linkage scans were used to identify genetic factors conferring the genetic susceptibility to sarcoidosis.12 Notably, the first genome-wide association study (GWAS) in sarcoidosis, conducted in a German population, has recently revealed an association: the leading rs2789679 SNP (single-nucleotide polymorphism (SNP)) located in the 3′-UTR (untranslated region) and a common non-synonymous SNP (rs1049550, C>T, Arg230Cys) were associated with the increased risk of sarcoidosis.4 13 This association has recently been supported by another report from the same population.14 Thus, more studies should be performed to demonstrate the following items: whether these SNPs modulate the risk of sarcoidosis by themselves or whether they correlate with other causative SNPs and are repeated in other populations. The published studies about the association of sarcoidosis and ANXA11 are summarised in online supplementary table S1. We hypothesise that common variants in the ANXA11 gene may significantly contribute to the predisposition to develop sarcoidosis.

In this study, we investigated 15 loci in a Chinese population from the He'nan province (China) to verify the putative association between ANXA11 polymorphisms and sarcoidosis.

Subjects and methods

Subjects

Four hundred and twelve patients with sarcoidosis (mean±SD age: 53.6±4.6 years; 155 men and 257 women) were recruited from our hospital between May 2005 and March 2013. Sarcoidosis was diagnosed by the evidence of non-caseating epithelioid cell granuloma in biopsy specimens and chest X-ray (CXR) abnormalities. Chronic sarcoidosis was defined as a disease over at least 2 years or at least two episodes in a lifetime. Acute sarcoidosis was defined as one episode of acute sarcoidosis which had totally resolved at the date of the examination. The control group consisted of 418 unrelated healthy participants (mean±SD age: 54.2±5.3 years; 160 men and 258 women) who underwent health examinations in the Medical Examination Center of the First Affiliated Hospital of the Xinxiang Medical College (Xinxiang, China) between October 2009 and September 2013. None of the individuals in the control group had a history of lung diseases or showed any symptoms of the lung or other diseases by CXR or laboratory blood tests. Participants were excluded if they: were taking other prescribed medications that could affect the central nervous system; had a history of seizures, hematological diseases or severe liver or kidney impairment; or were pregnant. No familial relationship was known between the study participants.

SNP selection

Tagging SNPs were selected from the catalogues of the International HapMap Project. The rs2789679 and rs2245168 are located in 5’-UTR, rs2236558 in intron 6, rs7067644 and rs12763624 in intron 8, rs1049550 in exon 10, rs2573351 in intron 13, rs10887581, rs11201989, rs2573353, rs2789695, rs2573356, rs2819945, rs11202059 and rs2819941 in intron 14 (see online supplementary figure S1). Marker selection was based on the following criteria. (A) We used the CHB data from the HapMap (release 27) to select tagSNPs for ANXA11. (B) We restricted our search for tagSNPs from base pair 80155124 to base pair 80205677. (C) Further, we limited SNPs to tag to those with a minor allele frequency ≥0.2 in the CHB. (D) Based on these restrictions, there were a total of 29 SNPs. (e) Using HAPLOVIEW with an r2 threshold ≥0.8, 15 tagSNP were selected and used for subsequent analyses.

Genotyping

Peripheral blood was collected from a vein into a sterile tube coated with EDTA. Plasma samples were stored at −20°C. Genomic DNA was extracted from the frozen peripheral blood samples using a QIAmp Blood Mini Kit (Qiagen Inc., Valencia, California, USA) according to the manufacturer's protocols. The selected SNPs were genotyped in cases and controls by using the MALDI-TOF in the MassARRAY system (Sequenom Inc., San Diego, California, USA). Probes and primers were designed using the Assay Design Software (Sequenom, San Diego, California, USA). The completed genotyping reactions were spotted onto a 384 well spectroCHIP (Sequenom) using the MassARRAY Nanodispenser (Sequenom) and determined by the matrix-assisted laser desorption ionisation time-of-flight mass spectrometer. Genotype calling was performed in real time with the MassARRAY RT software V.3.0.0.4 and analysed using the MassARRAY Typer software V.3.4 (Sequenom).

Statistical analysis

All data were analysed using the SPSS V.17.0 software (SPSS Inc., Chicago, Illinois, USA). The Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium was evaluated by χ2 tests. Differences between cases and controls in the frequency of the alleles, genotypes and haplotypes were evaluated by Fisher's exact test or the Pearson χ2 test. Unconditional logistic regression was used to calculate the OR and 95% CI in independent association between each locus and the presence of sarcoidosis. Gender and age of participants were treated as covariants in binary logistic regression. p Values were calculated based on codominant, dominant for the rare allele, heterosis and recessive for the rare allele models of inheritance. Models of multiple logistic regression were used to test the independence of individual allelic effect. In detail, the most significant SNP was chosen to be the conditional SNP (covariate in the regression model) when testing other significant SNPs; Meanwhile, a multi-SNP model including all significant SNPs was also performed. The Bonferroni correction was used to adjust the test level when multiple comparisons were conducted, and the p value was divided by the total number of loci. Haplotype blocks were defined according to the criteria developed by Gabriel et al15 Pairwise LD statistics (D′ and r2) and haplotype frequency were calculated, and haplotype blocks were constructed using the Haploview 4.0.16 To ensure that the LD blocks most closely reflect the population level LD patterns, the definition of blocks was based on the control samples alone. The haplotype frequencies were estimated using GENECOUNTING, which computes maximum-likelihood estimates of haplotype frequencies from unknown phase data by utilising an expectation-maximisation algorithm.17–20 The significance of any haplotypic association was evaluated using a likelihood ratio test, followed by permutation testing that compared estimated haplotype frequencies in cases and controls.17 19

Results

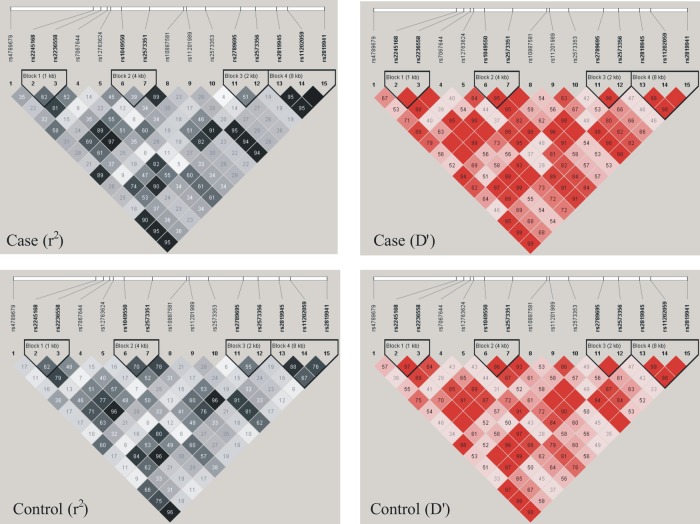

The genotype distribution of the 15 polymorphisms was consistent with the Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium (p>0.05). The analysis of strong LD in patients with sarcoidosis and healthy controls revealed that 2 SNPs (rs2245168, rs2236558), 2 SNPs (rs1049550, rs2573351), 2 SNPs (rs2789695, rs2573356) and 3 SNPs (rs2819945, rs11202059, rs2819941) were located in haplotype block 1, block 2, block 3 and block 4 (D′>0.9, figure 1). The genotype distribution, allelic frequencies and haplotypes in patients with sarcoidosis and healthy controls are showed in tables 1–3 and online supplementary table S2.

Figure 1.

The LD plot of the 15 SNPs in the ANXA11 gene. Values in squares are the pairwise calculation of r2 (left) or D′ (right). Black squares indicate r2=1 (ie, perfect LD between a pair of (single-nucleotide polymorphisms SNPs)). Empty squares indicate D′=1 (ie, complete LD between a pair of SNPs).

Table 1.

Genotypic and allelic frequencies of ANXA11 polymorphisms in controls and patients with sarcoidosis

| Variable | Controls (n=418) |

Sarcoidosis (n=412) |

p Value* | OR, 95% CI | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No | Per cent | No | Per cent | |||

| rs2789679 | 0.0007 | |||||

| TT | 114 | 27.3 | 94 | 22.8 | 0.140 | 1.27, 0.93 to 1.74 |

| AT | 225 | 53.8 | 186 | 45.2 | 0.012 | 1.42, 1.08 to 1.87 |

| AA | 79 | 18.9 | 132 | 32.0 | 0.0002 | 0.49, 0.36 to 0.68 |

| Per A allele | 383 | 45.8 | 450 | 54.6 | 0.00004 | 1.42, 1.17 to 1.73 |

| rs1049550 | 0.0002 | |||||

| CC | 154 | 36.8 | 208 | 50.5 | 0.0007 | 0.57, 0.43 to 0.75 |

| CT | 190 | 45.5 | 170 | 41.3 | 0.221 | 1.19, 0.90 to 1.56 |

| TT | 74 | 17.7 | 34 | 8.3 | 0.0008 | 2.39, 1.55 to 3.68 |

| Per T allele | 338 | 40.4 | 238 | 28.8 | 0.000002 | 0.61, 0.49 to 0.74 |

| rs2819941 | 0.0002 | |||||

| CC | 114 | 27.3 | 94 | 22.8 | 0.141 | 1.27, 0.93 to 1.74 |

| CT | 226 | 54.1 | 190 | 46.1 | 0.021 | 1.38, 1.05 to 1.81 |

| TT | 78 | 18.7 | 128 | 31.1 | 0.0004 | 0.51, 0.37 to 0.70 |

| Per T allele | 382 | 45.7 | 446 | 54.1 | 0.0006 | 1.41, 1.16 to 1.71 |

*p Value was calculated by 2×3 and 2×2 χ2 tests based on codominant, dominant for the rare allele, heterosis and recessive for the rare allele models of inheritance.

α Value is adjusted by Bonferroni correction and statistically significant results (p<0.003).

Table 2.

ANXA11 haplotype in block 2 frequencies and the results of their associations with risk of sarcoidosis

| Haplotype |

Genecounting (frequency %) |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ID | rs1049550 | rs2573351 | Cases | Controls | p Value* | Global p value† |

| HAP1 | T | C | 27.7 | 39.7 | 0.001 | 0.003 |

| HAP2 | C | C | 19.9 | 7.4 | 0.0001 | |

| HAP3 | C | T | 50.5 | 51.0 | 0.892 | |

*Based on 10 000 permutations.

†Based on a comparison of frequency distribution of all haplotypes for the combination of SNPs.

Table 3.

ANXA11 haplotype in block 3 frequencies and the results of their associations with risk of sarcoidosis

| Haplotype |

Genecounting (frequency %) |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ID | rs2789695 | rs2573356 | Cases | Controls | p Value* | Global p Value† |

| HAP1 | C | T | 33.7 | 34.9 | 0.718 | 0.045 |

| HAP2 | T | T | 15.3 | 14.1 | 0.632 | |

| HAP2 | T | T | 15.6 | 14.1 | 0.565 | |

*Based on 10 000 permutations.

†Based on a comparison of frequency distribution of all haplotypes for the combination of SNPs.

A comparison of genotype and allele frequency distribution revealed significant differences between patients with sarcoidosis and healthy controls for 3 SNPs: rs2789679, rs1049550 and rs2819941. The frequency of the rs1049550 T allele (p=0.000002, OR=0.61, 95% CI 0.49 to 0.74) in patients with sarcoidosis was significantly lower than that in the controls. These differences remained statistically significant after Bonferroni corrections. The rs1049550 was the most significant of the three. A multi-SNP model revealed rs1049550 to be the only significant independent SNP association with sarcoidosis risk.

The multi-SNP model showed that only rs1049550 presented a significant effect on disease phenotype (p<0.001). No independent effect was found for rs2789679 or rs2819941 when adjusting for the effect of rs1049550. Individual SNP and multi-SNP analysis supported rs1049550: T allele was an important protective factor for affecting sarcoidosis (OR around 0.6). In words, carriers of rs1049550: the C allele has higher susceptibility to sarcoidosis in our Chinese Han population (see online supplementary table S3).

We performed an association analysis to determine whether the haplotype was associated with the risk of sarcoidosis (Global p<0.05 in block 2 and block 3). Compared with controls, the T–C haplotype occurred significantly less frequently (p=0.001) but C–C haplotypes occurred more frequently (p=0.0001) in block 2 (rs1049550–rs2573351) in patients with sarcoidosis.

To assess particular disease phenotypes, patients with sarcoidosis were divided into subgroups according to their CXR stage. CXR stage I (isolated bilateral hilar lymphadenopathy): N=196; CXR stages II–IV (infiltration of parenchyma): 167; CXR stage 0 (absence of pulmonary disease): N=28; the information on CXR stage was not available for 21 patients. Genotype frequency distribution revealed that, in rs1049550, the CC genotype was significantly more in patients with CXR stage I sarcoidosis than in patients with CXR stages II–IV sarcoidosis (p=0.012; table 4).

Table 4.

Chest X-ray stages of patients with sarcoidosis by genotype of rs2789679, rs1049550 and rs2819941

| Stages | rs2789679 (n, %) |

rs1049550* (n, %) |

rs2819941 (n, %) |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AA | AT | TT | CC | CT | TT | CC | CT | TT | |

| Stage I | 59 (30.1) | 92 (47.0) | 45 (23.0) | 101 (51.5) | 82 (41.8) | 13 (6.6) | 47 (25.0) | 88 (44.9) | 61 (31.1) |

| Stages II−IV | 46 (27.6) | 75 (44.9) | 46 (27.6) | 72 (43.1) | 68 (40.7) | 27 (16.2) | 41 (24.6) | 73 (43.7) | 53 (31.7) |

| χ2, p value | 1.041, 0.594 | 8.807, 0.012 | 0.052, 0.975 | ||||||

*p Values for genotype frequency distribution (p<0.05).

Discussion

A key step in linkage and association studies is to identify common risk variants in different populations. To determine if common risk variants exist in distinct populations, 15 SNPs which span approximately 0.53 Mb of the ANXA11 gene were genotyped in samples from patients with sarcoidosis and healthy controls in a Chinese Han population. Recently, new sarcoidosis loci have been identified by GWASs.4 14 With the fast development of GWAS, an increasing number of susceptibility loci for sarcoidosis have been found in different populations.4 14 21 However, these observations should be confirmed in other genetically independent populations. In this study, we conducted the first large genetic association study of the ANXA11 gene in a Chinese Han population. The evidence of markers associated with sarcoidosis was presented, and these markers were mapped to different locations in the ANXA11 gene (81897864–81951001). The association signals in the region were identified, and some significantly associated haplotypes also appeared in this region.

Hofmann et al4 reported an association between the T allele of the non-synonymous SNP rs1049550 and significantly decreased risk of sarcoidosis in a German population. Similar results were also obtained in other two European populations.14 21 As a part of the sarcoidosis GWAS done in Americans,22 we further confirmed this association in a Chinese Han population. In this study, the frequency of the ANXA11 rs1049550 T allele was significantly lower in patients with sarcoidosis than in healthy controls. Genotype frequency distribution revealed that, in rs1049550, the CC genotype was significantly more in patients with stage I sarcoidosis than in patients with stage II–IV sarcoidosis. The ‘protective’ effect of the ANXA11 T allele increased with the number of its copies in the genotype, which is consistent with the result obtained in patients with sarcoidosis in a German population4 Furthermore, the T allele carriers among patients were protected from infiltration of lung parenchyma (radiographic stages II–IV).21 We have also demonstrated that rs1049550 is significant cross-ethnically at the gene level after adjustment for the single SNP association tests performed. The mechanism by which rs1049550 affects the susceptibility to sarcoidosis is that the SNP may affect the function of the ANXA11 protein rather than its expression. In humans, the ANXA11 protein consists of an N-terminal proline-tyrosine-glycine rich region, followed by four annexin core domains. The rs1049550 leads to an amino-acid exchange (basic arginine to a polar cysteine) at the evolutionarily conserved position 230 (R230C) in the first annexin domain, which is responsible for the Ca2+-dependent trafficking of the protein in the cell.23

In the GWAS conducted by Hofmann et al4, the strongest association signal was observed for rs2789679. This marker is located in the 3′-(untranslated region) UTR of the ANXA11 gene. The T allele had a frequency of 35% among patients with sarcoidosis and 44% in healthy controls, with 13% of patients with sarcoidosis and 19% of controls being TT homozygous. Fine-mapping in the Black Women's Health Study (BWHS) revealed rs2819941 to be the top SNP, associated with a non-significant (p=0.06) reduction in the risk of sarcoidosis (17% reduction per copy of the C-allele). In this case–control association study, the frequency of the A allele in rs2789679 and the rs2819941 T allele frequency in patients with sarcoidosis were significantly higher than they were in healthy controls. Several lines of evidence suggest that the observed association is unlikely to be an artefact. First, the single-SNP and the haplotype-based association analyses support the current finding. Second, our samples were from the same geographical region. Finally, consistent results were obtained from two genetically independent populations (Chinese Han and Europeans). Collectively, our results confirmed the strong association between ANXA11 polymorphisms and sarcoidosis, suggesting that ANXA11 represents a strong genetic risk factor for sarcoidosis. Since causal SNP in ANXA11 was not known, all the SNPs significantly associated with sarcoidosis were actually indirect associations through the real causal one. Though rs2789679 and rs2819941 were not in LD with rs1049550, it may not tag the causal SNP as well as rs1049550. Hence, their individual effects were eliminated when controlling for the effect of rs1049550.

We further investigated the interaction among polymorphisms and observed strong LD. The haplotype analysis revealed that significantly more C–C (block 2, rs1049550–rs2573351) and significantly fewer T–C haplotypes (block 2) were found in patients with sarcoidosis. These results indicated that patients with C–C (block 2) haplotypes of the ANXA11 gene were more prone to sarcoidosis. Significantly higher frequencies of T–C haplotypes were detected in healthy controls than in patients with sarcoidosis, suggesting that they may show protective effects against sarcoidosis. Our sample size can detect SNP and haplotype associations with 90% and 85% power, respectively, at a false positive rate of 5%, disease prevalence of 1‰, disease allele/haplotype frequency of 0.05/0.03, and a presumed OR of 1.5. To some extent, this finding further supports a role of ANXA11 polymorphisms in sarcoidosis, while ethnic group difference may exist.

In conclusion, our study suggests a potential role of ANXA11 SNPs and their related haplotypes in the genetic susceptibility to sarcoidosis. Further studies are needed to investigate how these SNPs affect the function of ANXA11. A broader examination of the genetic variation in ANXA11 in the Han Chinese may reveal other variants associated with disease risk.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Contributors: LGZ was involved in the conception and design of the study, acquisition of patient data, genotyping and drafting of the paper. ZJX and GCS were involved in the design of the study, genotyping and interpretation of results. JH and CXZ were involved in the design of the study, acquisition of patient data and interpretation of results. All authors revised the draft paper.

Funding: The project was supported by the Research and Development Foundation of Science and Technology of Henan Province (2012k15).

Competing interests: None.

Patient consent: Obtained.

Ethics approval: The study was performed according to the Guidelines of the Medical Ethical Committee of Xinxiang Medical College (Xinxiang, China).

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

References

- 1.Iannuzzi MC, Rybicki BA, Teirstein AS. Sarcoidosis. N Engl J Med 2007;357:2153–65 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Baughman RP, Lower EE, du Bois RM. Sarcoidosis. Lancet 2003;361:1111–18 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Grunewald J. Review: role of genetics in susceptibility and outcome of sarcoidosis. Semin Respir Crit Care Med 2010;31:380–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hofmann S, Franke A, Fischer A, et al. Genome-wide association study identifies ANXA11 as a new susceptibility locus for sarcoidosis. Nat Genet 2008;40:1103–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gerke V, Moss SE. Annexins: from structure to function. Physiol Rev 2002;82:331–71 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Farnaes L, Ditzel HJ. Dissecting the cellular functions of annexin XI using recombinant human annexin XI-specific autoantibodies cloned by phage display. J Biol Chem 2003;278:33120–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tomas A, Futter C, Moss SE. Annexin 11 is required for midbody formation and completion of the terminal phase of cytokinesis. J Cell Biol 2004;165:813–22 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Petzmann S, Maercker C, Markert E, et al. Enhanced proliferation and decreased apoptosis in lung lavage cells of sarcoidosis patients. Sarcoidosis Vasc Diffuse Lung Dis 2006;23:190–200 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dubaniewicz A, Trzonkowski P, Dubaniewicz-Wybieralska M, et al. Comparative analysis of mycobacterial heat shock proteins-induced apoptosis of peripheral blood mononuclear cells in sarcoidosis and tuberculosis. J Clin Immunol 2006;26:243–50 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Agostini C, Trentin L, Facco M, et al. Role of IL-15, IL-2, and their receptors in the development of T cell alveolitis in pulmonary sarcoidosis. J Immunol 1996;157:910–18 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jullien D, Sieling PA, Uyemura K, et al. IL-15, an immunomodulator of T cell responses in intracellular infection. J Immunol 1997;158:800–6 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Muller-Quernheim J, Schurmann M, Hofmann S, et al. Genetics of sarcoidosis. Clin Chest Med 2008;29:391–414 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Morais A, Lima B, Peixoto M, et al. Annexin A11 gene polymorphism (R230C variant) and sarcoidosis in a Portuguese population. Tissue Antigens 2013;82:186–91 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Li Y, Pabst S, Kubisch C, et al. First independent replication study confirms the strong genetic association of ANXA11 with sarcoidosis. Thorax 2010;65:939–40 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gabriel SB, Schaffner SF, Nguyen H, et al. The structure of haplotype blocks in the human genome. Science 2002;296:2225–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Barrett JC, Fry B, Maller J, et al. Haploview: analysis and visualization of LD and haplotype maps. Bioinformatics 2005;21:263–5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Curtis D, Knight J, Sham PC. Program report: GENECOUNTING support programs. Ann Hum Genet 2006;70:277–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zhao JH, Curtis D, Sham PC. Model-free analysis and permutation tests for allelic associations. Hum Hered 2000;50:133–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zhao JH, Lissarrague S, Essioux L, et al. GENECOUNTING: haplotype analysis with missing genotypes. Bioinformatics 2002;18:1694–5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zhao JH, Sham PC. Generic number systems and haplotype analysis. Comput Methods Programs Biomed 2003;70:1–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mrazek F, Stahelova A, Kriegova E, et al. Functional variant ANXA11 R230C: true marker of protection and candidate disease modifier in sarcoidosis. Genes Immun 2011;12:490–4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Levin AM, Iannuzzi MC, Montgomery CG, et al. Association of ANXA11 genetic variation with sarcoidosis in African Americans and European Americans. Genes Immun 2013;14:13–18 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tomas A, Moss SE. Calcium- and cell cycle-dependent association of annexin 11 with the nuclear envelope. J Biol Chem 2003;278: 20210–16 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.