Abstract

Aim

Evaluate the effectiveness of self-management training in community-dwelling adults with schizophrenia.

Methods

A total of 201 individuals with chronic schizophrenia (mean duration of illness of 17.4 years) were recruited and randomized into the self-management intervention group (n=103) and treatment-as-usual control group (n=98). The self-management training involved weekly group sessions for 6 months in which basic self-management skills were discussed and modelled followed by monthly group booster sessions for 24 months in which a community health worker reviewed patients’ self-management checklist journals. Two psychiatrists who were blind to group assignment evaluated the symptoms and social functioning of participants at baseline and 6 months and 30 months after enrollment using the Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale (BPRS), Social Disability Screening Schedule (SDSS), and Morningside Rehabilitation Status Scale (MRSS). A total of 194 individuals (99 from the intervention group and 95 from the control group) completed the 2.5-year follow-up. Intention-to-treat analysis with the last observation carried forward method was used for analysis.

Results

Compared to the control group, the intervention group had lower mean scores in the BPRS, SDSS and MRSS at both follow-up points. The scores in the intervention group continued to improve during the maintenance phase of the treatment from 6 months to 30 months after enrollment.

Conclusion

Self-management training is an effective method to improve symptoms and social functioning among individuals with chronic schizophrenia living in the community. After six months of weekly training in self-management skills, monthly booster sessions reviewing patients’ daily checklist of illness-related symptoms events are sufficient to maintain the beneficial effects of the training. Further study of the long-term cost-effectiveness of this method is needed.

Keywords: schizophrenia, community mental health services, self-care, rehabilitation, randomized controlled trial, blind assessment

Abstract

目标

评估自我管理训练对社区精神分裂症成年患者的效果。

方法

总共招募了201 例慢性精神分裂症患者(平均病程17.4 年),并随机分为自我管理干预组(n=103)和常规治疗对照组(n=98)。自我管理训练包括每周一次小组会议,为期6 个月,讨论和模拟基本的自我管理能力,然后进行24 个月的每月小组助推会议,社区卫生工作人员回顾患者的自我管理清单。两名对分组单盲的精神科医生评估参与者基线和登记后6 个月、30 个月的症状和社会功能,采用简明精神病评定量表(BPRS) ,社会功能缺陷筛选量表(SDSS)和Morningside 康复状态量表(MRSS) 。总共有194人(干预组99 人和对照组95 人)完成2.5 年的随访。使用末次观察结转法的意向性治疗分析进行分析。

结果

相较于对照组,干预组在两个随访时间点的BPRS,SDSS 和MRSS 平均分较低。在入组后6 个月到30 个月的治疗维持阶段,干预组的评分持续改善。

结论

自我管理训练是一种能改善社区慢性精神分裂症患者的症状和社会功能有效的方法。在6 个月的每周自我管理技能训练后,每月的助推会议检查患者记录中与疾病相关的症状事件的日常清单,足以维持培训的有效性。将来研究应注意该方法的长期成本效益。

1. Introduction

Schizophrenia is a severe mental disorder that results in substantial disease burden. The degree of disability associated with schizophrenia in China is higher than that of any other mental disorder.[1] Psychiatric rehabilitation can reduce the severity of disability and, thus, improve social functioning among individuals with schizophrenia, but relatively few individuals with schizophrenia use rehabilitation services, despite their wide availability in urban parts of China. For example, a previous study found that only 2.2% of all individuals with a serious mental disorder who are registered in the monitoring system of persons with mental disorders in Shanghai used rehabilitation services provided by the 245 rehabilitation and community daycare centers across the municipality.[2] This low service-utilization makes it difficult to achieve the goal of reducing the disability and disease burden associated with schizophrenia. One approach to addressing this issue is to develop ‘chronic disease self-management’ (CDSM) programs. These programs promote skills that help individuals with chronic diseases deal with their physical and emotional problems and, thus, improve and maintain their psychological well-being.[3] CDSM is a patient-centered intervention strategy requiring few resources that has been shown to achieve sustainable improvements in functioning, making it a feasible community-based chronic disease control method.[4] Huang and colleagues[5] found that the integration of self-management training about treatment among 26 inpatients with schizophrenia effectively improved their self-care skills, social interaction skills and overall social functioning; but the effectiveness of CDSM training among community-dwelling individuals with mental disorders in China has not yet been assessed. The randomized controlled trial reported in this paper evaluated the effectiveness of CDSM training among a sample of individuals with schizophrenia living in one of Shanghai’s 19 districts.

2. Methods

2.1. Sample

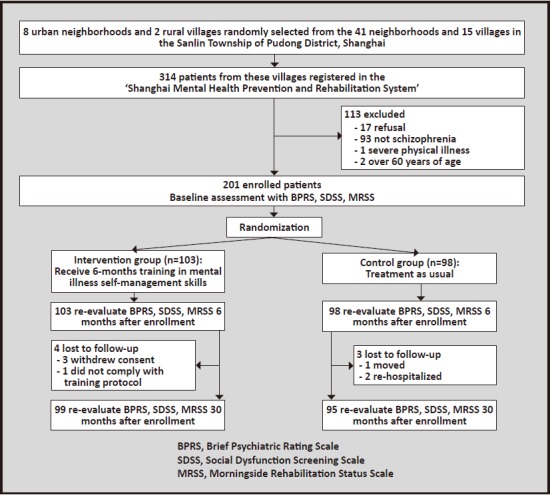

As shown in Figure 1, participants in this study were from 10 randomly selected communities, including 8 urban neighborhoods and 2 rural villages (out of 41 neighborhoods and 15 villages), in the Sanlin Township of Pudong District in Shanghai. These 10 communities have a total population of 19,203 individuals. All 314 individuals in this township enrolled in the ‘Shanghai Mental Health Prevention and Rehabilitation System’ as of July 2011 were sent a letter inviting them to participate in the study. Enrolled participants met the following inclusion and exclusion criteria: (a) met the diagnostic criteria for schizophrenia according to the Chinese Classification of Mental Disorders, 3rd edition (CCMD-3),[6] (b) 18 to 60 years of age, (c) had a middle school education or higher, (d) had relatively stable symptoms and no severe physical diseases, and (e) provided written informed consent (signed by the participant and the guardian). Among the 314 individuals registered in the rehabilitation system, 113 either refused or did not meet the above inclusion criteria. The remaining 201 individuals were randomly assigned (by the toss of a coin) to the intervention group (n=103) or the control group (n=98). Among these participants, 99 (96.1%) in the intervention group and 95 (96.9%) in the control group completed the 30-month follow-up assessment.

Figure 1. Flowchart of the study.

As shown in Table 1, most of these patients had chronic schizophrenia and multiple hospitalizations: the mean duration of illness in all 201 individuals was 17.4 years. There were no statistically significant differences between the two groups in sex, age, level of education, family history of schizophrenia, marital status, number of hospital admissions or duration of illness. During the course of this study, participants took their usual medications. There was no difference in the chlorpromazine-equivalent dosage of antipsychotic medications between the two groups at baseline.

Table 1.

Comparison of demographic characteristics of the individuals in the self-management (intervention) group and treatment as usual (control) group

| Intervention group (n=103) |

Control group (n=98) |

t or χ2 | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Male, n(%) | 55 (53.4%) | 51 (52%) | 0.03 | 0.825 |

| Age, mean (sd) | 35.3 (9.6) | 34.7 (9.9) | 0.92 | 0.334 |

| Years of schooling, mean (sd) | 9.7 (2.6) | 9.7 (2.8) | 0.06 | 0.978 |

| Marital status, n (%) | 0.96 | 0.591 | ||

| currently married | 55 (53.4%) | 50 (51.0%) | ||

| never married | 41 (39.8%) | 43 (43.9%) | ||

| no longer married | 7 (8.0%) | 5 (5.1%) | ||

| Age of onset, mean (sd) | 22 (5.4) | 23 (6.1) | 1.29 | 0.162 |

| Duration of illness in years, mean (sd) | 17 (13) | 18 (10) | 1.17 | 0.272 |

| Number of hospitalizations, mean (sd) | 2.2 (0.9) | 2.1 (0.9) | 1.57 | 0.179 |

| Chlorpromazine-equivalent daily dose of antipsychotic medications (mg), mean (sd) | 184 (27) | 192 (31) | 0.71 | 0.423 |

The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Pudong Yingbo Community Health Service Center.

2.2. Self-management training

The training employed in this study used the Medication Management and Symptom Management modules of the ‘UCLA Social & Independent Living Skills program’.[7] These modules focus on helping participants understand the importance of adhering to medications and recognize their residual symptoms and early signs of relapse. The modules also include training sessions about the management of adverse effects, the regulation of mood and impulsive behaviors, and the development of social skills. General information about mental disorders and about how to live life to the full is also provided. The last chapter of the manual provides instructions on the ‘self-management checklist journal’.

Weekly 2-hour training sessions based on these modules were provided to groups of 20 to 25 participants from the intervention group for six months. The weekly training sessions were jointly provided by a psychiatrist, a community mental health worker and a disability worker. Skills were taught using a combination of didactic instruction, group interactions, role-played rehearsals, and group discussions. Among the 99 participants in the intervention group who completed the 30-month follow-up, attendance at the 24 weekly sessions was excellent: the mean number of sessions attended was 21.8 (2.0) and the mean participation rate was 91%.

2.3. Self-management checklist journal

Upon completion of the six-months of training sessions, all participants in the intervention group received a ‘self-management checklist journal’ (referred to as ‘journal’ hereinafter) to record their daily adherence to medications, quality of sleep, occurrence of side effects, occurrence of residual symptoms and early signs of relapse, daily activities, and general mood. The main caregiver of the participant was asked to provide supervision and guidance in this process. Participants in the intervention group attended monthly self-management group meetings where community mental health workers checked and evaluated their journals. Among the 99 participants who completed the 30-month follow-up, attendance at the 24 monthly sessions was excellent: the mean number of sessions attended was 22.4 (1.5) and the mean participation rate was 91%.

2.4. Treatment-as-usual control group

Individuals assigned to the control condition received regular outpatient treatment with medication and routine monitoring of medication adherence and clinical status by community mental health workers.

2.5. Assessment

Participants were evaluated using the Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale (BPRS)[8], Social Disability Screening Schedule (SDSS)[9] and Morningside Rehabilitation Status Scale (MRSS)[10] at baseline, 6 months after enrollment (when the intervention group completed the weekly training), and 30 months after enrollment (i.e., 24 months after completion of the training in the intervention group). BPRS was used to evaluate the severity of symptoms: it has 18 items rated on 7-point Likert scales; higher scores indicate greater severity; and previous studies have shown that the Chinese version of the scale is both reliable and valid.[8] The SDSS has 10 items rated on 3-point Likert scales: higher scores indicate poorer social functioning and a previous study found that the Chinese version of the scale has good psychometric properties when used with community-dwelling individuals with chronic mental disorders.[9] The MRSS includes 28 items that assess four dimensions: dependency, inactivity in occupation and leisure, social integration or isolation, and current symptoms and deviant behavior. Higher scores indicate poorer social functioning. A previous study found good psychometric properties of the Chinese version of the MRSS when used to assess social functioning in community-residing individuals with schizophrenia.[10]

Assessments were conducted by two psychiatrists trained in the use of the scales who were blind to the group assignment. Their inter-rater reliability on the three scales employed in the study was excellent (Kappa=0.90-0.94, p<0.001). To limit the number of outlying values, whenever an evaluation resulted in score that was more than 3 standard deviations above or below the group mean for one of the three scales, a re-assessment by the second evaluator was conducted; if the difference between the two assessments was small, the first score was retained, if the difference was large, expert opinion was sought to arrive at a final score. Scores by the first evaluator were outside these 3 standard deviation limits 31 times in the 1,788 evaluations conducted during the study (1.7%) and in only one of these instances was it necessary to request evaluation by an expert because the result of the re-evaluation by the second rater was substantially different from the original result.

2.6. Statistical analysis

All data analysis was conducted using SPSS 10.0 statistical software. Intention-to-treat was used in the analysis with the last observation carried forward method. Means and standard deviations were used to describe continuous variables; repeated measures ANOVA with LSD adjustment for post-hoc comparisons was used to estimate the overall and between-group effects. Paired t-tests were used for within-group comparisons. Categorical variables were compared using χ2 tests. The level of statistical significance was set at 0.05.

3. Results

As shown in Table 2 there were no statistically significant differences at baseline between the two groups in the mean total scores of BPRS, SDSS or MRSS or in any of the four subscales scores of the MRSS. Six months after enrollment (at the time of completion of the weekly training courses in the intervention group) and 30 months after enrollment (after 24 monthly booster sessions in the intervention group) the change from baseline in the total scores of all three scales and in the four subscale scores of the MRSS were all significantly greater in the intervention group than in the control group.

Table 2.

Comparison of mean (sd) BPRS, SDSS, and MRSS scores at the baseline and at 6 months and 30 months after enrollment in the self-management (intervention) group and the treatment as usual (control) group

| Baseline | 6 months after enrollment (vs. baseline) |

30 months after enrollment (vs. baseline) |

||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| intervention | control | Fa | p | intervention | control | Fa | p | intervention | control | Fa | p | |

| BPRSb | 23.4 (1.9) | 22.1 (1.7) | 1.43 | 0.233 | 21.2 (2.0) | 21.9 (2.3) | 17.21 | <0.001 | 19.4 (1.6) | 21.4 (1.6) | 61.17 | <0.001 |

| SDSSc | 11.6 (3.0) | 11.2 (3.2) | 2.21 | 0.139 | 10.2 (3.1) | 12.6 (2.7) | 64.17 | <0.001 | 9.4 (2.6) | 12.7 (3.3) | 167.42 | <0.001 |

| MRSS | ||||||||||||

| dependencyd | 21.3 (4.7) | 21.6 (3.4) | 0.36 | 0.549 | 20.4 (3.2) | 21.4 (3.7) | 5.11 | 0.026 | 19.5 (2.8) | 22.4 (4.1) | 6.44 | 0.012 |

| activitye | 17.9 (2.9) | 18.1 (3.1) | 1.69 | 0.191 | 17.0 (2.6) | 17.9 (2.6) | 26.49 | <0.001 | 15.1 (2.9) | 18.7 (2.2) | 44.31 | <0.001 |

| social integrationf | 25.2 (3.0) | 25.5 (2.7) | 0.23 | 0.632 | 24.1 (2.8) | 25.2 (3.4) | 88.43 | <0.001 | 21.6 (3.1) | 26.4 (3.0) | 78.78 | <0.001 |

| symptomsg | 15.2 (1.9) | 15.4 (2.2) | 1.15 | 0.285 | 14.5 (2.4) | 15.2 (2.7) | 6.67 | 0.011 | 14.2 (2.5) | 15.9 (2.3) | 5.81 | 0.016 |

| total scoreh | 79.8 (14.9) | 80.6 (15.7) | 0.81 | 0.369 | 76.1 (13.8) | 79.8 (15.3) | 69.72 | <0.001 | 71.7 (14.5) | 83.7 (14.2) | 158.15 | <0.001 |

BPRS, Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale; SDSS, Social Disability Screening Schedule; MRSS, Morningside Rehabilitation Status Scale

aRepeated measures ANOVA was used to provide estimates; post-hoc comparisons were adjusted using the LSD method.

bIn intervention group paired t-test of baseline versus 6-month result was 2.14 (p=0.017) and paired t-test of 6-month vs. 30-month result was 2.46 (p=0.007)

cIn intervention group paired t-test of baseline versus 6-month result was 1.87 (p=0.032) and paired t-test of 6-month vs. 30-month result was 3.12 (p=0.001)

dIn intervention group paired t-test of baseline versus 6-month result was 2.12 (p=0.018) and paired t-test of 6-month vs. 30-month result was 2.37 (p=0.009)

eIn intervention group paired t-test of baseline versus 6-month result was 2.61 (p=0.005) and paired t-test of 6-month vs. 30-month result was 2.62 (p=0.005)

fIn intervention group paired t-test of baseline versus 6-month result was 2.87 (p=0.002) and paired t-test of 6-month vs. 30-month result was 1.74 (p=0.042)

gIn intervention group paired t-test of baseline versus 6-month result was 1.93 (p=0.028) and paired t-test of 6-month vs. 30-month result was 1.91 (p=0.029)

hIn intervention group paired t-test of baseline versus 6-month result was 2.45 (p=0.008) and paired t-test of 6-month vs. 30-month result was 4.23 (p<0.001)

In the intervention group, the total scores of the BPRS, SDSS and MRSS and the four subscale scores of the MRSS all decreased significantly from baseline to 6 months post-enrollment and also decreased significantly from 6 months post-enrollment to 30 months post-enrollment. In the control group there were no statistically significant changes in any of the seven measures between baseline and the 6-month post-enrollment evaluation or between the 6-month and 30-month post-enrollment evaluation.

4. Discussion

4.1. Main findings

This 2.5-year randomized controlled trial compared a self-management training program to treatment as usual in a relatively large sample of clinically stable patients with chronic schizophrenia who are living in the community. Only 4 of the 103 individuals enrolled in the intervention group dropped out of the study over the follow-up – a clear indication of the feasibility and acceptability of this self-management training approach among community-dwelling individuals with schizophrenia. Blind assessment of the outcome using standardized instruments that assess clinical and social outcomes clearly demonstrated the superiority of this method, both in the initial high-intensity intervention period (six months of weekly training sessions) and during the longer low-intensity follow-up period (24 months of monthly booster sessions to reinforce the use of patients’ daily self-monitoring checklists).

These findings are in line with a previous study that reported sustained effect 12 months after self-management training in a sample of individuals with a variety of chronic diseases.[11] Our findings also support the social cognitive theory underlying the use of interventions based on self-management of chronic diseases[12] which hypothesizes that better self-care can be achieved by training patients specific self-management skills.

Over the last several years increased attention has focused on the application of self-management training to individuals with mental disorders. Several studies have found evidence of effectiveness of self-management training among inpatients with schizophrenia.[13],[14] This study extended previous evidence to community-dwelling individuals with chronic schizophrenia – where the vast majority of persons with schizophrenia reside. In this study, the 24 weekly training sessions covered a wide range of skills aimed at enhancing patients’ overall quality of life and social integration.

Another prominent feature of this study is the 24 monthly ‘booster’ meetings after the more intensive weekly training sessions. We believe that these sessions were crucial to the sustained benefit seen in the study. The use of the journal, the involvement of co-resident family members in encouraging patients to complete the journal daily, and the monthly reports to a clinician about the content of the journal reinforces behaviors that enhance patients’ well-being and help family members and professional caregivers closely monitor patients’ condition and make earlier, preemptive interventions when the patient’s condition starts to deteriorate. Two other potential values of the journal are: (a) the daily review of the journal by family members promotes interaction between patients’ and their family members, and (b) The use of the daily journal requires patients to regularly assess their condition and behavior, giving them a greater sense of control.

4.2. Limitations

The sample selected for this study were individuals with schizophrenia with a mean duration of illness of 17 years who were already registered in the municipal monitoring system of persons with severe mental disorder. The very low dropout rate in the study and the very high participation rate of patients enrolled in the intervention training is probably related to their prior registration in the municipal monitoring program. These patients may have a longer course of illness and be more adherent to treatment than community-dwelling individuals with schizophrenia who are not registered in the municipal monitoring program. Thus the study would need to be repeated with a more unselected sample to determine its generalizability to all community-dwelling individuals with schizophrenia. Similarly, the low-intensity follow-up component of the intervention depended (partly) on the participation of co-resident family members who encouraged patients to complete their daily journals; the intervention may be less effective for individuals with schizophrenia who do not have co-resident family members who can play this important role.

More detailed information about compliance with medication, about the fidelity with which family members monitored patients’ journals, about the specific content of the journal, and about how clinicians employed the content of the journal during the follow-up group booster sessions would have provided more details about the mechanism of action of the intervention. In future studies it will also be important to add a cost-effectiveness component to more concretely assess the economic benefits (if any) of the improved functioning and quality of life that occurs after self-management training.

4.3. Implications

Bilsker[15] has pointed out similarities in the rehabilitation process of persons with mental disorders to that of persons with other chronic conditions. Although many require inpatient treatment during the acute phase of the illness due to impaired cognitive functioning, most people with mental disorders are capable of self-care once the acute symptoms subside. This study provides encouraging information about the feasibility and effectiveness of this relatively simple intervention. We found that self-management training with monthly follow-up monitoring of patients’ daily journals can produce a substantial and sustained improvement in the quality of life and social functioning of community-resident individuals with chronic schizophrenia. In settings like China were mental health personnel and resources are very limited (particularly in rural areas), the development of an effective self-management intervention like this could potentially make a major contribution to the quality of life and social functioning of the large numbers of persons with severe mental illnesses who currently receive inadequate treatment. If confirmed in further studies, the findings of this study would merit widespread application. Supplementary studies with patients who have less chronic forms of schizophrenia, with patients in both urban and rural settings and for even longer follow-up periods should be conducted to determine the potential range of individuals for whom this intervention would be beneficial. Cost-effectiveness studies could show the economic benefits of this low-tech intervention, information that would help attract government support for up-scaling this self-monitoring approach to care.

Biography

Dr. Bin Zhou obtained an associate degree in Preventive Medicine from Tongji University in 2003 and a bachelor’s degree in Family Medicine from Fudan University in 2010. He is an attending public health doctor at the Department of Preventive Health Care of Yingbo Community Health Service Center where he has been working since 2010. His main research interest is the community rehabilitation of mental disorders.

Funding Statement

This study was funded by the Shanghai Municipal Health Bureau Young Investigator Grant (20114y028).

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest: The authors declare no conflict of interest related to this manuscript.

References

- 1.Wang SC. [Functional Psychiatry Rehabilitation] Changsha: Hunan Science and Technology Press; Chinese. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zhang SJ, Wang JG. [Survey on the community mental health services in Shanghai] Lin Chuang Jing Shen Yi Xue Za Zhi. 2010;20(2):138–139. Chinese. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lorig K, Gonzalez VM, Ritter P. Community-based Spanish language arthritis education program: a randomized trial. J Med Care. 1999;37:957–966. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199909000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zhang LL, Dong JQ. [Advances in patient self-management of chronic disease] Zhongguo Man Xing Bing Yu Fang Yu Kong Zhi. 2010;8(2):207–211. Chinese. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Huang ZH. [Talking about the importance of self-management of mental illness in the recovery of social function] Xian Dai Zhen Duan Yu Zhi Liao. 2013;24(4):900–901. Chinese. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Society of Psychiatry, Chinese Medical Association. [Chinese Classification of Mental Disorders, 3rd edition (CCMD-3)] Shandong Province: Shangdong Science and Technology Publishing House; 2001. Chinese. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Liberman RP. Dissemination and adoption of social skills training: Social validation of an evidence-based treatment for the mentally disabled. J Ment Health. 2007;16(5):595–623. doi: 10.1080/09638230701494902. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zhang MY. [Brief psychiatric rating scale (BPRS)] Shanghai Jing Shen Yi Xue. 1984;2:58–59. Chinese. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wu WY. [Social dysfunction screening scale] In: Zhang MY, editor. Manual of Psychiatric Rating Scales 2nd. Hunan Changsha: Hunan Science and Technology Press; 1998. pp. 163–166. Chinese. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Liu QF, Zhu ZQ, Meng GR, Huang BK, Wang GB. [The study of reliability and validity of the Morningside rehabilitation state scale] Shanghai Jing Shen Yi Xue. 1998;10(3):147–149. Chinese. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Barlow JH Wright CC, Turner AP. A 12-month follow-up study of self-management training for people with chronic disease: Are changes maintained over time. Br J of Health Psychol. 2005;10:589–599. doi: 10.1348/135910705X26317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lorig KR, Sobel DS, Ritter PL, Laurent D, Hobbs M. Effect of a Self-management program on patients with chronic disease. Effect Clin Pract. 2001;4:256–262. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zhang L, Xie Y, He FL, Zhang JX, Jiang CL. [The impact of medication self-management module on treatment compliance, social function and quality of life for patients with schizophrenia] Zhongguo Shen Jing Jing Shen Ji Bing Za Zhi. 2010;36(10):603–607. doi: 10.3969/j.issn.1002-0152.2010.10.009. Chinese. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zhen HX. [The role of self-management in the social functional recovery of mental illness] Zhong Wai Yi Xue Yan Jiu. 2011;9(14):162. doi: 10.3969/j.issn.1674-6805.2011.14.139. Chinese. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bilsker D. Self management in the mental health field. BCs Mental Health Journal: Visions. 2003;18:4–5. [Google Scholar]