Abstract

Introduction

A survey conducted by the German Federal Centre for Health Education in 2012 showed that 35.2% of all young adults (18–25 years) and 12.0% of all adolescents (12–17 years) in Germany are regular cigarette smokers. Most smoked their first cigarette in early adolescence. We recently reported a significantly positive short-term effect of a physician-delivered school-based smoking prevention programme on the smoking behaviour of schoolchildren in Germany. However, physician-based programmes are usually very expensive. Therefore, we will evaluate and optimise Education against Tobacco (EAT), a widespread, low-cost programme delivered by about 400 medical students from 16 universities in Germany.

Methods and analysis

A prospective quasi-experimental study design with two measurements at baseline (t1) and 6 months post-intervention (t2) to investigate an intervention in 10–15-year-olds in grades 6–8 at German secondary schools. The intervention programme consists of two 60-min school-based medical-student-delivered modules with (module 1) and without the involvement of patients with tobacco-related diseases and control groups (no intervention). The study questionnaire measuring smoking status (water pipe and cigarette smoking), smoking-related cognitions, and gender, social and cultural aspects was designed and pre-tested in advance. The primary end point is the prevalence of smokers and non-smokers in the two study arms at 6 months after the intervention. The percentage of former smokers and new smokers in the two groups and the measures of smoking behaviour will be studied as secondary outcome measures.

Ethics and dissemination

In accordance with Good Epidemiologic Practice (GEP) guidelines, the study protocol was submitted for approval by the responsible ethics committee, which decided that the study does not need ethical approval (Goethe University, Frankfurt-Main, Germany). Findings will be disseminated in peer-reviewed journals, at conferences, within our scientific advisory board and through medical students within the EAT project.

Keywords: smoking prevention, schools, tobacco prevention, medical students, adolescent smoking, school-based prevention

Strengths and limitations of this study.

No medical-student-delivered school-based tobacco prevention programme has been evaluated for its primary preventive effect until now.

It is imperative to sensitise prospective physicians to tobacco prevention.

The quasi-experimental design of this study might cause a selection bias due to the lack of randomisation.

Cluster effects cannot be excluded entirely as the control classes are located in the same schools and pupils could exchange what they have learnt.

As our research is not multinational, it might not be useful for persons of all ethnic and cultural backgrounds.

Since our study relies on self-reports obtained from adolescents via a questionnaire for data collection, there is a risk that the actual prevalence of smoking may be different from the reported prevalence, for example, due to the social desirability bias.

Our follow-up data are only collected 6 months after the intervention due to organisational reasons. Thus, we will not be able to determine which effects the intervention might have at 1 year follow-up.

Background

Tobacco consumption is a risk factor for various diseases and leads to the highest number of avoidable deaths worldwide.1 Despite warning labels and public interventions, smoking was responsible for almost 107 000 deaths in Germany alone in 2007.2 There are high costs associated with smoking. One study estimated the smoking-related costs for acute hospital care, inpatient rehabilitation care, ambulatory care and prescription drugs in Germany to be €7.5 billion in 2003.3

Most smokers started smoking in early adolescence.4 In a survey conducted by the German Federal Centre for Health Education (BZgA) in 2012, 35.2% of all young adults (18–25 years) and 12.0% of all adolescents (12–17 years) in Germany described themselves as regular cigarette smokers.5 A 2006 survey that quantified nicotine dependence in Germany using the Fagerström test reported that 50.8% of the 15–17-year-old smokers and 41.8% of the 18–24-year-old smokers were dependent on nicotine.6 Laucht and Schmid7 reported a correlation between the number of cigarettes smoked by 15-year-olds and the starting age of smoking; moreover, those adolescents who had started smoking earlier in life were more likely to be still consuming tobacco and to consume more cigarettes and have a higher degree of dependence than their peers.

Furthermore, the use of water pipes has increased in the past few years.8 According to a 2011 survey by the Federal Centre for Health Education, 8.7% of adolescents and 11.2% of young adults surveyed had smoked a water pipe at least once in the 30 days leading up to the survey.8 Male respondents smoked a water pipe more frequently than women respondents.8 According to Maziak,9 water pipes lead the way to cigarette smoking and have similarly deleterious effects on human health. Early primary prevention of smoking is thus of crucial importance and should be promoted, evaluated and optimised.

Some scientifically evaluated smoking prevention programmes already exist in Germany, like the Smoke-Free Class (SFC) competition which has been practically implemented in many countries of the European Union.10–12 However, the only study of the SFC competition which reported a significant effect on the prevention of smoking at the longest follow-up had multiple biases according to the recent Cochrane Database Systematic Review on incentives for preventing smoking in adolescents by Johnston et al.12 In addition, Johnston et al12 calculated the adjusted relative risk (RR) of the study and no longer detected a statistically significant difference. Finally, the authors concluded that there are no incentive programmes available until now which have shown how to prevent smoking initiation among youth.12

In addition to that, the SFC competition focuses only on cigarettes and not on water pipe smoking. Furthermore, there is no comparable beneficial effect for the instructors of the SFC programme. Education Against Tobacco (EAT) additionally sensitises prospective physicians to the importance of tobacco prevention. A recent study from Yale University suggests that tobacco addiction is undertreated by physicians in comparison to other chronic conditions.13 The authors concluded that alternative models of engagement may be needed to enhance use of effective treatments for tobacco addiction and to raise awareness among physicians.

To the best of our knowledge, medical-student-delivered school-based programmes for preventing smoking have not been evaluated until now. Little relevant data are available in scientific databases such as Medline or PubMed. The most relevant publication on the topic is the Cochrane Database Analysis on school-based programmes for preventing smoking.14 The authors analysed the data from 134 studies in 25 different countries in a total of 428 293 young people aged 5–18. Forty-nine of these studies reported smoking behaviour in adolescents who had never previously smoked. No overall effect of intervention curricula versus control was found based on the pooled results at follow-up at 1 year or less (OR 0.94; 95% CI 0.85 to 1.05).14 From our perspective, the most relevant finding of the Cochrane Analysis is that social competence and social influence curricula have a statistically significant effect of preventing the onset of smoking.14 The authors concluded that further research is required to design and test programmes that will be equally effective for people of different genders, cultural backgrounds and ethnic groups. Interventions delivered by adult educators were shown to be more effective in the longer term than peer-education programmes. Medical students belong to the group of adult educators. According to the Cochrane Analysis, cost-effectiveness plays an important role in practical implementation. As EAT is delivered by medical student volunteers, it is less expensive and more easily available than physician-delivered programmes.

Secondary school programmes that involve physicians as health educators already exist. In fact, Stamm-Balderjahn et al15 recently published data on a school-based physician-delivered programme (Students in the Hospital) in Berlin, which achieved significant positive results with a multimodal approach. From September 2007 to July 2008, they conducted an anonymous questionnaire survey with a quasi-experimental control group design 2 weeks before (t1) and 6 months after (t2) the intervention in a group of 760 participating school students in Berlin. The results indicated that 40.8% of the participants were smokers at baseline, 79% of whom stated that they also smoked water pipes. Regarding the primary prevention outcome of the study, it was found that significantly fewer students in the intervention group began smoking within 6 months of the intervention than in the control group (p<0.001). In addition, the chance of remaining a non-smoker was four times higher in the intervention group (OR 4.14; CI 1.66 to 10.36). Concerning gender, girls appeared to benefit more from the intervention than boys (OR 2.56; CI 1.06 to 6.19). In total, 16.1% of smokers in the intervention group and 17.6% in the control group stopped smoking (p>0.05). A primary preventive effect of the programme was clearly and conclusively demonstrated.

Non-smoking is Cool (NiC), another physician-delivered programme based in Hamburg, Germany, addresses grades 5–6 of all secondary school types (total sample size reported: 1359 students).16 The programme uses a social influence-based and fear-based curriculum. Multiple studies have shown that fear-based appeals are ineffective for primary tobacco prevention in the long term.17 NiC proved to be effective in grammar schools, where it reduced the onset of smoking in the intervention group by 50% compared to the control group at 3 and 9 months follow-up, but with a small effect size.16 Nevertheless, it failed to show a significant primary preventive effect in schools with a lower educational level (general, intermediate or comprehensive school).16

Considering the high cost of physician-based programmes and the lack of available physicians, it is indicated to evaluate a less expensive and widespread programme that sensitises prospective physicians to tobacco prevention.

Gender-specific aspects

Our recent study using the physician-based approach for school-based tobacco prevention15 showed that girls benefit from physician-delivered programmes more than boys do (OR 2.56; CI 1.06 to 6.19). We aim to assess whether this effect is also observed using the EAT medical student-based approach. If so, the programme will be modified for gender mainstreaming since both sexes need to be addressed equally.

Cultural aspects

We hypothesise that there will be a small but significant relation between water pipe smoking and cultural background since water pipe use is traditional in the Middle East region.18 Therefore, we plan to collect data on the cultural background of the students. Comprehensive information about water pipe smoking is an integral component of the EAT programme. Within the proposed optimisation process, the EAT curriculum can be tailored to the different school populations (eg, schools with or without a high percentage of pupils with a migration background) as needed.

Social aspects

According to a survey conducted by the Federal Centre for Health Education,5 the prevalence of cigarette smoking in 10–15-year-olds in Germany was significantly higher in schools with lower education levels in 2012 (16.7% vs 6.9%). Consequently, we plan to specifically address schools with lower education levels and to compare the effects of the intervention on different school types.

School-based smoking prevention programme delivered by medical students

EAT is a non-profit, medical-student-delivered school-based smoking prevention programme founded in August 2011 by Titus Brinker, a medical student at the University of Gießen, and developed in cooperation with professors from the Universities of Gießen, Frankfurt and Marburg as well as medical students from Texas A&M University. The programme takes the Cochrane Analysis into account.19 Its mission is to focus on the development of low-cost prevention programmes and their implications for research, and to combine social influence approaches with generic social competence approaches. Both of these key points were taken into account when developing the curriculum. At the time of development, there was already research available that encouraged the use of medical students in such programmes. For example, Sussman et al20 concluded that health educator-led drug prevention programmes are more effective than self-instructed programmes.

Since physician-based programmes have proven to be successful15 but usually are very expensive, we aimed to evaluate and optimise EAT, a widespread low-cost programme which is being delivered by about 400 medical students at 16 universities in Germany. It costs only about € 25 per participating class. The city of Gießen, home of the largest EAT group with the highest level of experience and the most participating EAT schools, is an adequate platform to evaluate the effects of EAT.

Objectives

- To assess the efficacy of the programme, we investigated two main questions:

- Does the EAT programme help non-smokers to remain abstinent?

- Does the EAT programme encourage smokers to take steps to stop smoking?

- To assess whether the programme is equally effective for participants of different gender, social and cultural backgrounds, we investigated the questions:

- Is the EAT programme equally effective for both genders?

- Is the EAT programme equally effective for different school types?

- Is the EAT programme equally effective for different cultural backgrounds?

Methods

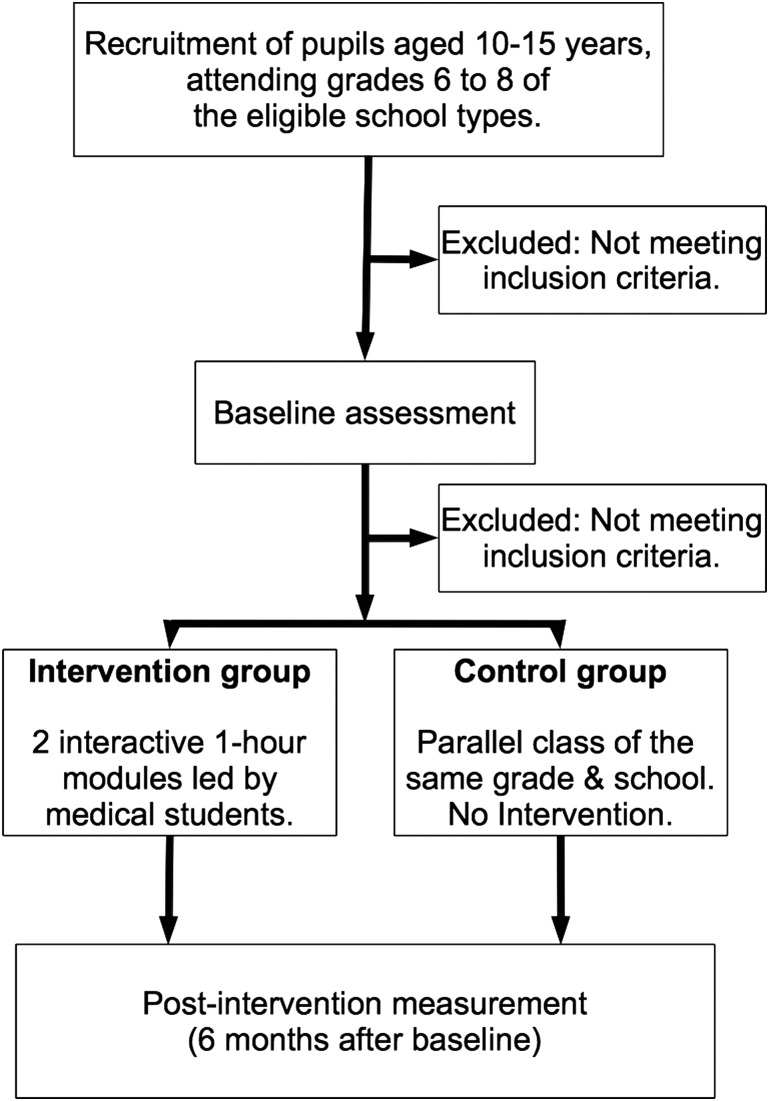

Design

The survey is designed as a quasi-experimental prospective evaluative study with two measurements (baseline and 6 months post-intervention). The planned study period is October 2013 until July of 2014. Participants in two study groups (intervention and control groups) will be questioned up to 2 weeks in advance of the intervention (t1) and 6 months thereafter (t2) (see figure 1).

Figure 1.

Study design.

Randomisation could not be performed due to the tremendous organisational and personal effort required for it. Some classes refused to participate when informed that they would be control groups. To keep confounding factors to a minimum, a parallel class in a given grade was selected as the control group. All participating schools were asked in advance to split their grades into two class-groups with the same performance levels. Schools that did not agree to the splitting procedure were excluded. A parallel class is defined as a control class in the same grade as the intervention class, with the same performance level as the intervention class, and attending the same school as the intervention class. All intervention classes had parallel classes. We chose to do the follow-up at 6 months so that the control group could receive the intervention in the same school year (after data collection is completed). This made it easier for us to convince schools to participate.

Participants

Eligibility criteria

Students aged 10–15 attending grades 6–8 of a secondary general, intermediate, grammar or comprehensive school are eligible. Older or younger students or students from other school types are not. Schools in Gießen and the surrounding area already participate in the programme each year. They know that participation is voluntary and can be ended at any time without giving a reason. The geographical area concerned (Gießen and surrounding villages) was informed about the study via the Hessian Ministry of Education and Cultural Affairs.

Intervention

The programme consists of two 60-min modules. The first part is presented by two to six medical students and a patient with a tobacco-related disease to all pupils at the same time inside a large room within the school. It consists of an interactive PowerPoint presentation in which the participants are encouraged to make their own well-informed decisions and receive relevant knowledge on handling confrontations with their peers (social competence approach). The university hospital patient with a smoking-related disease is interviewed about his reasons to start smoking and the influence tobacco consumption had on his life. The participants are encouraged to ask the patient questions. The second part takes place in an interactive classroom setting in which two medical students (usually a male and a female) tutor one class. Both modules focus on educating adolescents about the strategies of the tobacco industry to influence their decision in a non-objective manner (social influence) and on peer pressure (social influence), decision-making and skills for coping with challenges in their life in a healthy way (social competence). The participants also discuss information relevant for their age group, for example, why non-smokers usually look more attractive, have more money to buy things or are in better physical shape. The programme focuses on not scaring but educating its participants in an interactive manner. EAT uses a combined social influences and social competences approach, which was described as the most effective approach in the recently published Cochrane Analysis.14

Data collection

A written survey questionnaire is used for the collection of data. The questionnaire was developed to collect data at both time points (t1–t2). In addition to the socio-demographic data (age, gender, school type), it will capture the smoking status of the school students concerning water pipe and cigarette consumption.

The questionnaire contains numerous items which have already been included in similar investigations. The questions about the smoking status and the frequency of smoking refer to the evaluation of the school-based smoking prevention programmes in Heidelberg entitled ‘ohne kippe’ (no butts)21 and in Berlin entitled ‘Students in the Hospital’15 as well as to the results of the KiGGs child and adolescent surveys published by Lampert and Thamm.22

To test the questionnaire in accordance with the Good Epidemiologic Practice (GEP) guidelines,23 we distributed 88 copies to pupils with the lowest education level in May 2013. Eighty-five of the completed questionnaires were deemed as a useful way for evaluation, but seven had not been filled out completely. Therefore, we added a note to turn the page at the bottom of each page to fix this problem.

Class teachers will individually supervise their classes during the completion of the questionnaire. To maximise the confidentiality of the intervention, the questionnaires will be placed in envelopes that will instantly be sealed by the responsible class teachers immediately after completion. The envelopes will be opened and the data entry and analysis performed under the supervision of Prof. Dr Groneberg at the Goethe University of Frankfurt.

Outcomes

The primary outcome is the prevalence of smokers and non-smokers at 6 months after the intervention. The percentage of former smokers and new smokers in the two groups and the measures of smoking behaviour (the number of cigarettes and water pipes smoked on a daily, weekly or monthly basis) will be studied as secondary outcome measures. A smoker is defined as a pupil who claims to smoke at least ‘once a month’ within the survey. Those pupils who claim not to smoke at all are defined as non-smokers. In accordance with their answers within the survey, non-smokers will be divided into ‘former smokers’ and ‘non-smokers who have never smoked before’.

Statistical analysis

Sample size calculation

As there is no other evaluated school-based programme delivered by medical students, our study has an explorative character. Still, we decided to calculate the sample size (using the programme BiAS for Windows) on the basis of a recently published study which evaluated the ‘Non-smoking is Cool’ school-based physician-delivered programme in Hamburg.16 To calculate the sample based on effect size requirements, we used the difference in the number of persons who started smoking within 9 months between the intervention and control groups at grammar schools investigated in the reference study (6.4% in the intervention group vs 12% in the control group yields a difference of 5.6%).16 We decided to use the method of Sack et al for our calculations because ‘Students in the Hospital’ mainly included school types with a lower educational level. We used the rates for grammar school students, who will be the largest group of participants in our study. Thus, we calculated that the required sample size is 435 pupils per group (870 total), plus the loss to follow-up group at a test power of 80% (α=0.05). We took into account the loss to follow-up effect of ‘Students in the Hospital’ (17.8%), which increased our group size to n1=514 and n2=514 (total: 1028).15

Analysis

In order to examine baseline differences of pupils’ characteristics in our quasi-experimental design, we will use χ2-tests for the categorical variables and t tests for continuous variables. There must be no significant differences between the two study groups at baseline (t1). The effects of predictors (like gender, culture and social characteristics) on the smoking behaviour after 6 months (t2) will be calculated by logistic regression analysis, a state-of-the-art technique for the evaluation of the effectiveness of prevention programmes21 24 25 in longitudinal studies. The significance level is 5% for t tests (double-sided) and 95% for CIs (double-sided). The statistical analysis will be performed using the newest version of SPSS Statistics for Mac by IBM.

Legal approval

In accordance with the GEP guidelines,23 the study protocol was submitted for approval by the responsible ethics committee, which decided that the study does not need ethical approval. All legal and data protection issues were discussed with the responsible authority, the Ministry of Education and Cultural Affairs in Germany, which approved the proposed data collection within the participating schools. In addition, each school individually discussed and approved the study at a school conference. It was explained to each student that participation is voluntarily, and informed written consent was obtained from the parents of the study participants.

Discussion

No evaluation of a medical-student-delivered school-based tobacco prevention programme is available until now. It is imperative to sensitise prospective physicians to tobacco prevention.13 An additional aim of this study is to evaluate whether a medical-student-delivered smoking prevention programme has preventive effects on the smoking behaviour of secondary school pupils in Germany. The data from this study will provide a sound basis for optimising the EAT curriculum to make it optimally effective for different target groups. A promising factor of the EAT programme is that it uses a combined social influence and social competence approach, which was been shown to be effective in the recently published Cochrane Analysis.14

Our study has a quasi-experimental design. The main problem with this kind of study is selection bias due to the lack of randomisation. To minimise this problem, we will match the intervention classes with control classes (same grade and school), which corresponds to the matching procedure in field experiments.

As the intervention and control groups attend the same schools, the pupils could exchange what they learn about smoking in the intervention during school breaks. Therefore, cluster effects cannot be excluded entirely.

Also, as our research is not multinational, it might not be useful for persons of all ethnic and cultural backgrounds.

Since our study relies on self-reports obtained from adolescents via a questionnaire for data collection, there is a risk that the actual prevalence of smoking may be different from the reported prevalence, for example, due to the social desirability bias. This bias can only be excluded by using expensive methods like testing for cotinine (a metabolite of nicotine) in the saliva, blood or urine of the students. Other alternatives described by Kentala et al26 include the measurement of thiocyanate in saliva or carbon monoxide in exhaled air. This group reported 95% agreement between the results of these biochemical tests and the results of questionnaires. Conversely, Connor Gorber et al27 found high differences between the biochemically assessed and self-reported smoking status in pregnant women and patients with tobacco-related diseases. In our study, there might be social desirability bias in both study groups, which might make the intervention look less effective than it actually is.

The first measurement at baseline occurs while the intervention group is anticipating the intervention. Therefore, more intervention group students might feel compelled to behave in a socially desirable way and falsely declare that they are non-smokers. In contrast, the control group students know that they will not see the medical students again anytime soon, so they might be inclined to answer the items on the questionnaire more honestly. At the second measurement time point, the situation is reversed: since the intervention group students know that the medical students will not come back, they might feel less social desirability pressure and be more likely to admit that they are smokers. In contrast, the control group students will be awaiting the next intervention in the coming weeks, so they might reply to the questionnaires in a more socially desirable way (declaring that they are non-smokers even if they smoke).

Consequently, the study could be compromised by social desirability bias at both time points, which could make the intervention look less effective.

In order to measure the long-term effects of school-based programmes, follow-up data are usually collected 6 months and 1 year after an intervention. However, we will only be able to collect data 6 months post-intervention because the schools insisted on us providing an intervention for the control group in the same school year. Thus, we will not be able to determine which effects the intervention might have at 1 year follow-up.

Conclusion

We expect that our research will find general acceptance because the investigated programme provides many medical students and even more medical interns (eg, in the elective period known) a great opportunity to deliver prevention programmes not only in inpatient secondary prevention, but also and in particular in primary prevention in schools and communities. Health systems worldwide could benefit from the development of such novel and low-cost primary smoking prevention programmes.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Contributors: TJB contributed to the design and conduct of the study, drafted the manuscript and performed the statistical analysis. WS supported the coordination of the study. SS-B contributed to the design of the study, participated in the writing process and proofread the manuscript. DAG contributed to the design of the study and proofread the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript. This study is part of a thesis project (TJB).

Funding: Each participating school pays a small fee for the copies of the questionnaire that are being distributed to every participating student.

Competing interests: None.

Ethics approval: Ethics committee of the Goethe University, Frankfurt am Main, Germany.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1.World Health Organization. WHO report on the global tobacco epidemic. 2011. http://whqlibdocwhoint/publications/2011/9789240687813_engpdf

- 2.Mons U. [Tobacco-attributable mortality in Germany and in the German Federal States—calculations with data from a microcensus and mortality statistics]. Gesundheitswesen 2011;73:238–46 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Neubauer S, Welte R, Beiche A, et al. Mortality, morbidity and costs attributable to smoking in Germany: update and a 10-year comparison. Tob Control 2006;15:464–71 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Haustein K-O, Groneberg D. Tobacco or health? Physiological and social damages caused by tobacco smoking. Springer, 2009 [Google Scholar]

- 5.2013. Bundeszentrale für gesundheitliche Aufklärung (BZgA): Der Tabakkonsum Jugendlicher und junger Erwachsener in Deutschland 2012. (Bericht). Teilband Rauchen, Bericht.

- 6.Kraus L, Rosner S, Baumeister SE, et al. Epidemiologischer Suchtsurvey 2006. Repräsentativerhebung zum Gebrauch und Missbrauch psychoaktiver Substanzen bei Jugendlichen und Erwachsenen in Berlin. IFT-Bericht Band 167, München, 2008

- 7.Laucht M, Schmid B. Early onset of alcohol and tobacco use – indicator of enhanced risk of addiction? Z Kinder Jugendpsychiatr Psychother 2007:35:137–43 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.2012. Bundeszentrale für gesundheitliche Aufklärung (BZgA): Die Drogenaffinität Jugendlicher in der Bundesrepublik Deutschland 2011. Teilband Rauchen, Bericht.

- 9.Maziak W. The global epidemic of waterpipe smoking. Addict Behav 2011;36:1–5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Isensee B, Morgenstern M, Stoolmiller M, et al. Effects of Smokefree Class Competition 1 year after the end of intervention: a cluster randomised controlled trial. J Epidemiol Community Health 2012;66:334–41 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hoeflmayr D, Hanewinkel R. Do school-based tobacco prevention programmes pay off? The cost-effectiveness of the ‘Smoke-free Class Competition’. Public Health 2008;122:34–41 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Johnston V, Liberato S, Thomas D. Incentives for preventing smoking in children and adolescents. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2012;10:CD008645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bernstein SL, Yu S, Post LA, et al. Undertreatment of tobacco use relative to other chronic conditions. Am J Public Health 2013;103:e59–65 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Thomas RE, McLellan J, Perera R. School-based programmes for preventing smoking. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2013;4:CD001293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Stamm-Balderjahn S, Groneberg DA, Kusma B, et al. Smoking prevention in school students: positive effects of a hospital-based intervention. Dtsch Arztebl Int 2012;109:746–52 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sack P-M, Hampel J, Bröning S, et al. Was limitiert schulische Tabakprävention? Prävention und Gesundheitsförderung 2013;8:246–51 [Google Scholar]

- 17.2008. Springfield IPF: Ineffectiveness of fear appeals in youth Alcohol, Tobacco and Other Drug (ATOD) Prevention. Prevention First.

- 18.Akl EA, Gunukula SK, Aleem S, et al. The prevalence of waterpipe tobacco smoking among the general and specific populations: a systematic review. BMC Public Health 2011;11:244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Thomas R, Perera R. School-based programmes for preventing smoking. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2006;(3):CD001293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sussman S, Sun P, McCuller WJ, et al. Project Towards No Drug Abuse: two-year outcomes of a trial that compares health educator delivery to self-instruction. Prev Med 2003;37:155–62 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Maier B, Bau AM, James J, et al. Methods for evaluation of health promotion programmes. Smoking prevention and obesity prevention for children and adolescents. Bundesgesundheitsblatt Gesundheitsforschung Gesundheitsschutz 2007;50:980–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lampert T, Thamm M. [Consumption of tobacco, alcohol and drugs among adolescents in Germany. Results of the German Health Interview and Examination Survey for Children and Adolescents (KiGGS)]. Bundesgesundheitsblatt Gesundheitsforschung Gesundheitsschutz 2007;50:600–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Epidemiologie DAfr: Leitlinien und Empfehlungen zur Sicherung von Guter Epidemiologischer Praxis (GEP). BMBF Gesundheitsforschung. 2004. http://wwwgesundheitsforschung-bmbfde/_media/Empfehlungen_GEPpdf.

- 24.Pbert L, Flint AJ, Fletcher KE, et al. Effect of a pediatric practice-based smoking prevention and cessation intervention for adolescents: a randomized, controlled trial. Pediatrics 2008;121:e738–747 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sloboda Z, Stephens RC, Stephens PC, et al. The Adolescent Substance Abuse Prevention Study: a randomized field trial of a universal substance abuse prevention program. Drug Alcohol Depend 2009;102:1–10 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kentala J, Utriainen P, Pahkala K, et al. Verification of adolescent self-reported smoking. Addict Behav 2004;29:405–11 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Connor Gorber S, Schofield-Hurwitz S, Hardt J, et al. The accuracy of self-reported smoking: a systematic review of the relationship between self-reported and cotinine-assessed smoking status. Nicotine Tob Res 2009;11:12–24 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.