Abstract

Objectives

Acquired severe aplastic anaemia is a rare and potentially fatal disease. The aim of this Cochrane review was to evaluate the effectiveness and adverse events of first-line allogeneic haematopoietic stem cell transplantation of human leucocyte antigen (HLA)-matched sibling donors compared with first-line immunosuppressive therapy.

Setting

Specialised stem cell transplantations units in primary care hospitals.

Participants

We included 302 participants with newly diagnosed acquired severe aplastic anaemia. The age ranged from early childhood to young adulthood. We excluded studies on participants with secondary aplastic anaemia.

Interventions

We included allogeneic haematopoietic stem cell transplantation as the test intervention harvested from any source of matched sibling donor and serving as a first-line therapy. We included immunosuppressive therapy as comparator with either antithymocyte/antilymphocyte globulin or ciclosporin or a combination of the two.

Primary and secondary outcome measures planned and finally measured

The primary outcome was overall mortality. Secondary outcomes were treatment-related mortality, graft failure, graft-versus-host disease, no response to immunosuppressive therapy, relapse after initial successful treatment, secondary clonal disease or malignancies, health-related quality of life and performance scores.

Results

We identified three prospective non-randomised controlled trials with a study design that was consistent with the principle of ‘Mendelian randomisation’ in allocating patients to treatment groups. All studies had a high risk of bias due to the study design and were conducted more than 15 years. The pooled HR for overall mortality for the donor group versus the no donor group was 0.95 (95% CI 0.43 to 2.12, p=0.90).

Conclusions

There are insufficient and biased data that do not allow any firm conclusions to be made about the comparative effectiveness of first-line allogeneic haematopoietic stem cell transplantation of HLA-matched sibling donors and first-line immunosuppressive therapy of patients with acquired severe aplastic anaemia.

Keywords: CHEMOTHERAPY, STATISTICS & RESEARCH METHODS, TRANSPLANT MEDICINE

Strengths and limitations of this study.

We conducted a comprehensive literature search and strictly adhered to the projected methodology.

We restricted the study design to randomised controlled trials and prospective non-randomised controlled trials and the studies had to be compatible with ‘Mendelian randomisation’ to avoid excess risk of bias.

The included data are too scarce and too biased to allow any conclusion on the comparative effectiveness of matched sibling donor-haematopoietic stem cell transplantation and immunosuppressive therapy.

The included data were collected 15 to more than 30 years ago. Thus, the results may not be applicable to current modern standard care.

Introduction

Acquired severe aplastic anaemia (SAA) is a rare1 and potentially fatal disease which is characterised by hypocellular bone marrow and pancytopenia; it mainly affects young adults. The estimated incidence rate of SAA ranges from 0.7 to 4.1 per million people per year.2 The underlying pathophysiology is thought to be an aberrant immune response involving the T-cell-mediated destruction of haematopoietic stem cells.3 Major signs and symptoms are severe infections, bleeding and exhaustion and patients may experience paleness, weakness, fatigue and shortness of breath.

According to the 2009 Guidelines for the diagnosis and management of aplastic anaemia of the British Committee for Standards in Haematology,4 first-line allogeneic haematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT) from the bone marrow of an human leucocyte antigen (HLA)-matched sibling donor (MSD) is regarded as the initial treatment of choice for newly diagnosed patients with SAA. Graft failure may lead to early death and the conditioning regimen may lead to severe non-haematological organ toxicities.

According to the 2009 Guidelines for the diagnosis and management of aplastic anaemia of the British Committee for Standards in Haematology,4 first-line immunosuppressive therapy (IST) is a combination of antithymocyte globulin (ATG) and ciclosporin. First-line IST is indicated for patients where no MSD is available, which can be expected for 70% of patients with SAA.3 Ciclosporin is an immunosuppressant drug that is not lymphocytotoxic but has specific inhibitory effects on T-lymphocyte function.5 In the past, antilymphocyte globulin (ALG) was reported interchangeably in the literature alongside ATG, therefore, ALG is reported in the present study on equal terms. ATG as well as ALG are polyclonal antibodies that recognise a variety of human lymphocyte cell surface antigens, reduce the number of lymphocytes and induce an immunosuppressive effect. They originate in animals immunised with either normal human thymocytes, collected at paediatric cardiac surgery or thoracic duct lymphocytes, collected during therapeutic cannulation.5 Concerning the haematological response and the survival of patients after a first treatment for SAA, it may be crucial in what type of animal ATG originates, as a randomised study showed that rabbit ATG was inferior in this respect to horse ATG.6 The currently recommended combination of ciclosporin with ATG in the treatment of SAA is based on their separate and potentially complementary modes of action.5 Some patients do not respond well to IST or show no response at all. Frequent transfusions increase the risk of adverse events such as iron overload and early death. If a diagnosis of SAA is established at an early patient age, then it is crucial to know which treatment promises more benefit and less harm in the long run. We aimed to evaluate the effectiveness and severe adverse events of MSD-HSCT compared with IST in patients with SAA.

Methods

This article is based on a Cochrane Systematic Review published in The Cochrane Library.7 Publication of this work is in agreement with the policy of The Cochrane Collaboration.8 While preparing this systematic review and meta-analysis, we endorsed the PRISMA statement, adhered to its principles and conformed to its checklist.9

Study inclusion criteria

We included randomised controlled trials (RCTs) and prospective non-RCTs as long as the study design was consistent with the principle of ‘Mendelian randomisation’ in allocating patients to treatment groups. We required a minimum of 80% of relevant patients per group and we set a minimum sample size of five participants per group. We set no limits on language, year of publication or year of treatment. We included participants with newly diagnosed acquired SAA.4 We did not set any age limits for participants. We excluded studies on participants with secondary aplastic anaemia. We included HSCT as the test intervention harvested from any source of MSD and serving as a first-line therapy.10 That means, no other HSCT or IST has been offered to the patients before. We included IST as comparator with ciclosporin combined with ATG as the current mode of IST.10 To accommodate former modes of IST, we also included ciclosporin combined with ALG, cyclosporine alone, ATG alone and ALG. Other agents such as corticosteroids and androgens were not considered. The primary outcome was overall mortality. Secondary outcomes were treatment-related mortality, graft failure, graft-versus-host disease, no response to IST, relapse after initial successful treatment, secondary clonal disease or malignancies, health-related quality of life and performance scores.

Principle of ‘Mendelian randomisation’

There are ethical concerns around randomisation of patients with SAA to transplantation versus non-transplantation because the risk of early death is expected to be higher in the transplantation group than in the non-transplantation group. The reason is the potentially life-threatening graft-versus-host disease occurring only in the transplanted patients. Gray11 and Wheatley12 described the potential of ‘Mendelian randomisation’ to minimise bias when comparing MSD-HSCT with an alternative therapy. The base concept has been ascribed to Katan.13 ‘Mendelian randomisation’ means the view that nature itself has already ‘randomised’ the paternal and maternal part of a gene given that donor and recipient are siblings. Thus, ‘Mendelian randomisation’ by definition accepts only siblings as transplant donors and these sibling donors are required to have ‘identical’ or matched features of specific transplant-relevant HLA sites when compared with the transplant recipient. Therefore, patients with an HLA-matched sibling will be allocated to the MSD-HSCT group. On the other hand, patients with siblings that are not HLA compatible will be allocated to the IST group. The term ‘Mendelian randomisation’ refers to the fact that the genetic distribution of paternal and maternal alleles follows a random process and is determined before birth. This concept takes advantage of an instrumental variable for allocating the patients to treatment groups and, at the same time, this variable is neither associated with the treatment nor associated with the outcome.

Search strategy and selection of studies

We conducted an electronic literature database search in MEDLINE (Ovid), EMBASE (Ovid), and Cochrane Library CENTRAL (Wiley) including articles published from inception to 22 April 2013. The corresponding search strategies are depicted in the original Cochrane Review.7 We retrieved all titles and abstracts by electronic searching and downloaded them to the reference management database EndNote Version X3.14 Two authors assessed the eligibility of retrieved papers independently. We considered studies written in languages other than English. We judged studies to be prospective if an explicit statement was reported or there were clues suggesting a prospective design (eg, prior approval of treatment and informed consent). We judged studies to be retrospective if an explicit statement was reported or it was implied by description that data were reviewed from an existing source. We regarded each of the following items as an indication of a retrospective design: registry reports and reviewing of medical records. We judged studies as consistent with the principle of ‘Mendelian randomisation’ if all transplant donors were clearly siblings and if the allocation of patients to treatment groups was not based on age. We regarded studies as not consistent with the principle of ‘Mendelian randomisation’ if age was not balanced between groups, indicating that age played a role in the group assignment. Example for imbalance: distribution of age categories was statistically not comparable (p value less than 0.05).

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

Two review authors independently assessed the risk of bias in the included studies using six criteria. We have used four criteria from The Cochrane Collaboration’s tool for assessing risk of bias15: blinding of outcome assessment, complete outcome data such as missing data, selective reporting such as not reporting prespecified outcomes and other sources of bias such as bias related to the specific study design and competing interest. We extended the Cochrane tool for assessing risk of bias with two additional criteria that are specific to the inclusion criteria for the present review and critical for confidence in results: comparable baseline characteristics and concurrent control. We applied The Cochrane Collaboration’s criteria for judging risk of bias.16

Data synthesis

One review author entered the data into Review Manager.17 Another review author checked the entered data. We synthesised data on mortality for the donor group (MSD-HSCT) versus the no donor group (IST) by using the HR for time-to-event data as the primary effect measure with a random-effects model. If the HR was not directly given in the publication, we estimated HRs according to methods proposed by Parmar et al18 and Tierney et al.19

Results

Search results

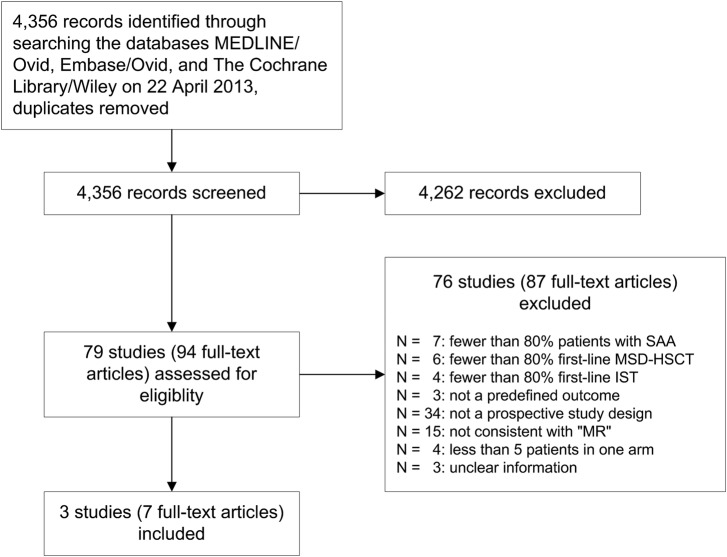

We identified three non-randomised, prospective, parallel and controlled clinical trials (figure 1). Bayever et al20 and Gratwohl et al21 reported their results in a single original article, respectively. Führer et al22 reported five publications including one original article, a follow-up article, 23 one protocol 24 and two abstracts. 25 26 We did not identify any RCTs.

Figure 1.

Study flow (IST, first-line immunosuppressive therapy; MSD-HSCT, first-line allogeneic haematopoietic stem cell transplantation of bone marrow of HLA-matched sibling donors; ‘MR’, ‘Mendelian randomisation’; SAA, acquired severe aplastic anaemia.

Characteristics of included articles

The main study, patients and interventions characteristics are shown in table 1. The patients were treated and observed between 1976 and 1997. Thus, the reported data were collected more than 15 years ago. Median follow-up was not reported. Median age, fraction of males and median days of time interval between diagnosis and begin of treatment were roughly comparable between the treatment groups within each study. The age ranged from early childhood to young adulthood. In the study by Führer et al,22 all patients were less than 17 years old by definition of the inclusion criteria. Bone marrow was used as the source for all transplants. All three included studies had a high risk of bias due to the study design (table 2). We judged a low risk of bias for blinding the assessment of overall mortality. Blinding or lack of blinding is not expected to make a difference concerning overall mortality. The authors of all included studies did not report that ‘Mendelian randomisation’ was planned and the authors did not report the size of the involved families. The authors did not report the numbers of siblings and the results of the individual genetic analyses.

Table 1.

Characteristics of included studies

| Study ID | Duration of study | Median FU | Setting, center, country | Patients, n* | Median age, years (range)* | Fraction of males, %* | Median interval, days*† | Stem cell source | IST components | ATG source |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bayever et al20 | 1977 to 1982 | NR | Single, USA | 35 vs 22 | 17 (2–24) vs 15 (1–23) | 67 vs 68 | 60 vs 58 | Bone marrow | ATG | horse |

| Führer et al22 | 1993 to 1997 | NR | Multi, Germany, Austria | 28 vs 86 | 10.1 (2.3–15.8) vs 9.1 (0.9–15.2) | 43 vs 62 | 49 vs 23 | Bone marrow | ATG Ciclosporin |

horse |

| Gratwohl et al21 | 1976 to 1980 | NR | Single, Switzerland | 19 vs 13 | 18 (4–29) vs 23 (7–37) | 53 vs 54 | 105 vs 180 | Bone marrow | ATG Ciclosporin |

N.R. |

*Donor group (MSD-HSCT) versus no donor group (IST).

†Median time interval between diagnosis and begin of treatment.

ATG, anti-thymocyte globulin; FU, follow-up; IST, immunosuppressive therapy; MSD-HSCT, HLA-matched sibling donor haematopoietic stem cell transplantation; NR, not reported.

Table 2.

Risk of bias of included studies

| Study ID | Blinding of assessment of overall mortality | Incomplete outcome data | Selective reporting | Other bias | Comparable baseline characteristics | Concurrent control | Overall judgement of bias |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bayever et al20 | Low | Low | Unclear | High* | Low | Low | High |

| Führer et al22 | Low | High | High† | High‡ | Low | Low | High |

| Gratwohl et al21 | Low | High | Unclear | Unclear | Low | Low | High |

*Bayever et al20: the authors reported the study results at an early time point before all planned data had been gathered: ‘We present this interim report (…)’.

†Führer et al22: In the 2005 update, overall survival, secondary clonal disease or malignancies, and also relapse were not reported separately for the two distinct treatment groups. Rather, the results were presented for two subgroups according to disease severity. This was different from the earlier report of the same study published in 1998 covering the study period from 1993 to 1997. See figure 1 and table 1 of the article.

‡Führer et al22: financial support was provided by two pharmaceutical companies.

Effects of intervention

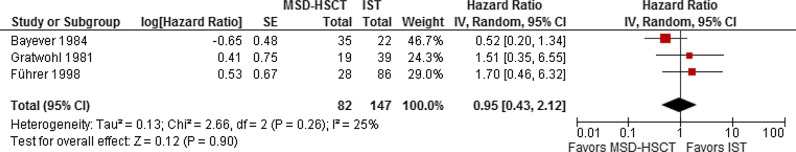

The pooled HR estimate for overall mortality was 0.95 with a 95% CI of 0.43 to 2.12 (p=0.90; figure 2). According to the meta-analysis based on data from all three included studies, overall mortality was not statistically significantly different between MSD-HSCT and IST. Overall survival ranged from 47% to 84% in the MSD-HSCT group and from 45% to 87% in the IST group (table 3). The results for the secondary outcomes including treatment-related mortality after MSD-HSCT, graft failure after MSD-HSCT, graft-versus-host-disease (GVHD) after MSD-HSCT, no response to IST and relapse after IST are shown in table 4. With respect to secondary clonal disease or malignancies, Bayever et al20 reported one patient who developed T-cell lymphoma after MSD-HSCT and Führer et al22 reported four patients who developed acute myelogenous leukaemia after IST. Health-related quality of life questionnaires were not used in any of the included studies. Bayever et al20 reported that almost all evaluable patients in the MSD-HSCT group (92%) and less than half of the patients in the IST group had a Karnofsky Performance Status of higher than 70%.

Figure 2.

Mortality in the donor group (MSD-HSCT) versus the no donor group (IST); effect: HR; random-effects model. SE calculated from data presented in the Kaplan-Meier graph of the article (MSD-HSCT, first-line allogeneic haematopoietic stem cell transplantation of bone marrow of HLA-matched sibling donors; log, logarithm; IST, first-line immunosuppressive therapy; IV, inverse variance).

Table 3.

Overall survival

| Study ID | Donor group (MSD-HSCT) |

No donor group (IST) |

FU* | p Value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | OS (95% CI), % | N | OS (95% CI), % | Year | ||

| Bayever et al20 | 35 | 72 (64 to 80) | 22 | 45 (29 to 61) | 2 | 0.18 |

| Führer et al22 | 28 | 84 (NR) | 86 | 87 (NR) | 4 | 0.43 |

| Gratwohl et al21 | 19 | 47 (NR) | 13 | 69† (NR) | 5 | 0.56‡ |

*Time point of Kaplan-Meier estimate.

†Gratwohl et al21: 2 of 13 patients were eligible for MSD-HSCT but donors were not available in the first place; the two patients died after they received a second-line HSCT from the then again available MSD that was offered after the patients showed no response to IST.

‡The p value was not reported and we calculated the p value using Fisher’s exact test.

FU, follow-up; IST, immunosuppressive therapy including ciclosporin and/or antithymocyte or antilymphocyte globulin; MSD-HSCT, first-line allogeneic haematopoietic stem cell transplantation from HLA-matched sibling donor; N, number of analysed patients; NR, not reported; OS, overall survival.

Table 4.

Secondary outcomes

| Study ID| | TRM after MSD-HSCT*† | Graft failure after MSD-HSCT* | GVHD after MSD-HSCT* | No response to IST* | Relapse at 5 years after IST* |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bayever et al20 | 20% (7 of 35) | 3% (1 of 35) | 51% (17 of 33) | 64% (14 of 22) | 12.5% (1 of 8) |

| Führer et al22 | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR |

| Gratwohl et al22 | 42% (8 of 19) | 16% (3 of 19) | 26% (5 of 19) | 15% (2 of 13) | NR |

*In parenthesis: number of affected of number of evaluable patients.

†Treatment-related mortality was not reported for IST.

GVHD, graft-versus-host disease; IST, immunosuppressive therapy including ciclosporin and/or antithymocyte or antilymphocyte globulin; MSD-HSCT, first-line allogeneic haematopoietic stem cell transplantation from HLA-matched sibling donor; NR, not reported; TRM, treatment-related mortality.

Discussion

Interpretation of main results

We identified three prospective, non-RCTs20–22 including 302 participants; 121 received MSD-HSCT and 181 received IST. On the basis of these trials we found insufficient evidence to clarify whether MSD-HSCT leads to better overall survival than IST. Overall survival ranged from 47% to 84% in the MSD-HSCT group and from 45% to 87% in the IST group and in a meta-analysis, overall mortality was not statistically significantly different between the treatment groups. Treatment-related mortality in the MSD-HSCT group was considerable ranging from 20% to 42%. The graft failure rate was variable and caused the death of 3% to 16% of transplanted patients. GVHD affected a quarter to a half of transplanted patients. More than half of the patients in one study did not respond to IST. Relapse affected up to one in eight patients after IST in one study. Secondary clonal disease or malignancies were detected rarely in both treatment groups. Marsh et al4 estimated that allogeneic bone marrow transplantation from an HLA-identical sibling donor provides a 75–90% chance of long-term cure in patients younger than 40 years of age. Similarly, in a review of studies with younger patients, Guinan27 reported an overall survival between 75% and 95% at 3–5 years. Sangiolo et al28 concluded that their data favours extending MSD-HSCT to patients older than 40 years of age who are without significant comorbidities. The results of the studies included in the present systematic review appear to roughly match the recent estimates reported by others.

Recent therapeutic improvement

Bacigalupo (2008)29 reported that the outcome has improved since 1996 for HSCT but not for IST. Peinemann et al30 identified three studies that reported a statistically significant improvement of overall survival in the group of matched related donor transplants but not in the IST group. Several factors may have contributed to recent improvements in HSCT, such as detailed HLA-matching and less irradiation-based conditioning. The Third Consensus Conference on the treatment of aplastic anaemia agreed in 2010 that bone marrow should be used as the source of stem cells and that the upper age limit should be 50 years and that the combination of ATG and ciclosporin remains the gold standard for IST.31 Scheinberg32 provided an overview and update of various treatment options for SAA including IST and transplantation.

Strengths and limitations

One of the strengths of this review is the broadness of the search strategy such that study retrieval bias is very unlikely. We restricted the inclusion of studies to RCTs and prospective non-RCTs that were compatible with ‘Mendelian randomisation’ to avoid excess risk of bias. We assumed a possible ‘Mendelian randomisation’ in the three included studies, though, the authors did not mention this approach and did not report what proportion of patients with an MSD actually received the transplant. Thus, crucial information is lacking to judge the compliance of patients and the significance of the assumed concept of natural allocation. Nevertheless, the included data are too scarce and too biased to allow any conclusion on the comparative effectiveness of MSD-HSCT and IST. The rates of adverse events, such as treatment-related mortality, graft failure, no response to IST and GVHD, are unusually high, which may be explained by the age of the studies (starting in 1976). We did not separate horse ATG from rabbit ATG, although the type of animal as the origin of ATG was reported as a serious effect modifier.6 All data were collected about 15 up to more than 30 years ago. Thus, the results may not be applicable to current modern standard care. Use of ‘Mendelian randomisation’ is no guarantee that bias is minimised. This may be because tissue typing data may not be accurate. Patients may have only one sibling either in the donor or in the no donor group. Large families have a greater chance of finding a donor. Therefore, designing a non-RCT by applying ‘Mendelian randomisation’ requires careful thought to effectively reduce bias and control for potential confounders. There is a time lag in patients with siblings because tissue typing and readiness for assignment to treatment group may possibly take several months.12 On the other hand, patients with no siblings can be assigned immediately and are at earlier risk for adverse events. Nitsch et al33 described the limits to causal inference based on ‘Mendelian randomisation’.

Conclusions

There are insufficient and biased data that do not allow any firm conclusions to be made about the comparative effectiveness of MSD-HSCT and IST. Patients should be made aware of the early treatment-related mortality and the burden of GVHD after HSCT. Patients treated with IST should also be made aware that the disease may recur after initial successful treatment, and that life-threatening late clonal and malignant disease after IST may occur in a higher percentage compared with HSCT.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the members of the Editorial Base of the Cochrane Haematological Malignancies Group, Cologne, Germany, especially Nicole Skoetz for advice on the review.

Footnotes

Contributors: FP involved in the design, search strategy, study selection, data extraction, data analysis and writing the manuscript. AL involved in the methodological perspective, reviewing the manuscript.

Funding: Provision of full texts by the University of Cologne, Germany. The publication of this article was supported by the University of Illinois at Chicago (UIC) Research Open Access Article Publishing (ROAAP) Fund.

Competing interests: None.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

This article is based on a Cochrane Systematic Review published in the Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2013, Issue 7. Art. No.: CD006407. DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD006407.pub2. (see http://www.thecochranelibrary.com for information). Cochrane Systematic Reviews are regularly updated as new evidence emerges and in response to feedback, and the CDSR should be consulted for the most recent version of the review.

References

- 1.Genetic and Rare Diseases Information Center (GARD). Aplastic anemia. Bethesda: The Office of Rare Diseases Research (ORDR) and the National Human Genome Research Institute (NHGRI) of the National Institutes of Health (NIH), 2013 [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kaufman DW, Kelly JP, Issaragrisil S, et al. Relative incidence of agranulocytosis and aplastic anemia. Am J Hematol 2006;81:65–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brodsky RA, Jones RJ. Aplastic anaemia. Lancet 2005;365:1647–56 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Marsh JCW, Ball SE, Cavenagh J, et al. Guidelines for the diagnosis and management of acquired aplastic anaemia. Br J Haematol 2009;147:43–70 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Young NS, Shimamura A. Chapter 9: Acquired bone marrow failure syndromes. In: Handin RI, Lux SE, Stossel TP, eds. Blood: principles and practice of hematology. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2003:273–318 [Google Scholar]

- 6.Scheinberg P, Nunez O, Weinstein B, et al. Horse versus rabbit antithymocyte globulin in acquired aplastic anemia. N Engl J Med 2011;365:430–8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Peinemann F, Bartel C, Grouven U. First-line allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation of HLA-matched sibling donors compared with first-line ciclosporin and/or antithymocyte or antilymphocyte globulin for acquired severe aplastic anemia. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2013;7:CD006407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.The Cochrane Collaboration. 2.2.5 Publication of versions of Cochrane Reviews in print journals. The Cochrane Policy Manual [updated 12 July 2013]. Oxford: The Cochrane Collaboration, 2013 [Google Scholar]

- 9.Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, et al. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS Med 2009;6:e1000097–97 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Passweg JR, Marsh JCW. Aplastic Anemia: First-line treatment by immunosuppression and sibling marrow transplantation. Hematology Am Soc Hematol Educ Program 2010;2010:36–42 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gray R, Wheatley K. How to avoid bias when comparing bone marrow transplantation with chemotherapy. Bone Marrow Transplant 1991;7(Suppl 3):9–12 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wheatley K, Gray R. Commentary: Mendelian randomization: an update on its use to evaluate allogeneic stem cell transplantation in leukaemia. Int J Epidemiol 2004;33:15–17 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Katan MB. Apolipoprotein E isoforms, serum cholesterol, and cancer. Lancet 1986;327:507–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.EndNote [program] New York: Thomson Reuters, 2013 [Google Scholar]

- 15.Higgins JPT, Altman DG, Sterne JAC. Table 8.5.a The Cochrane Collaboration's tool for assessing risk of bias. Chapter 8: Assessing risk of bias in included studies. In: Higgins JPT, Green S, eds. Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions version 510 [updated March 2011]. The Cochrane Collaboration, 2011. http://wwwcochrane-handbookorg [Google Scholar]

- 16.Higgins JPT, Altman DG, Sterne JAC. Table 8.5.d Criteria for judging risk of bias in the ‘Risk of bias’ assessment tool. Chapter 8: Assessing risk of bias in included studies. In: Higgins JPT, Green S, eds. Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions version 510 [updated March 2011]. The Cochrane Collaboration, 2011. http://wwwcochrane-handbookorg [Google Scholar]

- 17.Review Manager (RevMan) [program] Copenhagen: The Nordic Cochrane Centre, The Cochrane Collaboration, 2011 [Google Scholar]

- 18.Parmar MK, Torri V, Stewart L. Extracting summary statistics to perform meta-analyses of the published literature for survival endpoints. Stat Med 1998;17:2815–34 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tierney JF, Stewart LA, Ghersi D, et al. Practical methods for incorporating summary time-to-event data into meta-analysis. Trials 2007;8:16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bayever E, Champlin R, Ho W, et al. Comparison between bone marrow transplantation and antithymocyte globulin in treatment of young patients with severe aplastic anemia. J Pediatr 1984;105:920–5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gratwohl A, Osterwalder B, Nissen C, et al. Treatment of severe aplastic anemia. Schweiz Med Wochenschr 1981;111:1520–2 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Führer M, Burdach S, Ebell W, et al. Relapse and clonal disease in children with aplastic anemia (AA) after immunosuppressive therapy (IST): the SAA 94 experience. Klin Padiatr 1998;210: 173–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Führer M, Rampf U, Baumann I, et al. Immunosuppressive therapy for aplastic anemia in children: a more severe disease predicts better survival. Blood 2005;106:2102–4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Führer M, Bender-Götze C, Ebell W, et al. Treatment of aplastic anemia—aims and development of the SAA 94 pilot protocol. Klin Padiatr 1994;206:289–95 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Führer M, Rampf U, Burdach S. Immunosuppressive therapy (IST) and bone marrow transplantation (BMT) for aplastic anemia (AA) in children. Blood 1998;92:156a, abstract 631–156a, abstract 631 [Google Scholar]

- 26.Führer M, Rampf U, Niemeyer CM, et al. Bone marrow transplantation and immunosuppressive therapy in children with aplastic anemia: data from a prospective multinational trial in Germany, Austria and Switzerland. Blood 2004;104:abstract 1439-abstract 39 [Google Scholar]

- 27.Guinan EC. Acquired aplastic anemia in childhood. Hematol Oncol Clin North Am 2009;23:171–91 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sangiolo D, Storb R, Deeg HJ, et al. Outcome of allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation from HLA-identical siblings for severe aplastic anemia in patients over 40 years of age. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant 2010;16:1411–18 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. doi: 10.1038/bmt.2008.113. Bacigalupo A. Treatment strategies for patients with severe aplastic anemia. Bone Marrow Transplant 2008;42(Suppl 1):S42–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Peinemann F, Grouven U, Kroger N, et al. First-line matched related donor hematopoietic stem cell transplantation compared to immunosuppressive therapy in acquired severe aplastic anemia. PLoS ONE 2011;6:e18572–72 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kojima S, Nakao S, Young N, et al. The Third Consensus Conference on the treatment of aplastic anemia. Int J Hematol 2011;93:832–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Scheinberg P. Aplastic anemia: therapeutic updates in immunosuppression and transplantation. Hematology Am Soc Hematol Educ Program 2012;2012:292–300 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Nitsch D, Molokhia M, Smeeth L, et al. Limits to causal inference based on Mendelian randomization: a comparison with randomized controlled trials. Am J Epidemiol 2006;163:397–403 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.