Abstract

Objectives

Rescreen a large community cohort to examine the progression to heart failure over time and the role of natriuretic peptide testing in screening.

Design

Observational longitudinal cohort study.

Setting

16 socioeconomically diverse practices in central England.

Participants

Participants from the original Echocardiographic Heart of England Screening (ECHOES) study were invited to attend for rescreening.

Outcome measures

Prevalence of heart failure at rescreening overall and for each original ECHOES subgroup. Test performance of N Terminal pro-B-type Natriuretic Peptide (NT-proBNP) levels at different thresholds for screening.

Results

1618 of 3408 participants underwent screening which represented 47% of survivors and 26% of the original ECHOES cohort. A total of 176 (11%, 95% CI 9.4% to 12.5%) participants were classified as having heart failure at rescreening; 103 had heart failure with reduced ejection fraction (HFREF) and 73 had heart failure with preserved ejection fraction (HFPEF). Sixty-eight out of 1232 (5.5%, 95% CI 4.3% to 6.9%) participants who were recruited from the general population over the age of 45 and did not have heart failure in the original study, had heart failure on rescreening. An NT-proBNP cut-off of 400 pg/mL had sensitivity for a diagnosis of heart failure of 79.5% (95% CI 72.4% to 85.5%) and specificity of 87% (95% CI 85.1% to 88.8%).

Conclusions

Rescreening identified new cases of HFREF and HFPEF. Progression to heart failure poses a significant threat over time. The natriuretic peptide cut-off level for ruling out heart failure must be low enough to ensure cases are not missed at screening.

Keywords: EPIDEMIOLOGY

Strengths and limitations of this study.

The study represents a rescreen of one of the largest well-phenotyped cohorts screened for heart failure in the world.

Contemporary echocardiographic equipment and techniques were used to diagnose heart failure.

The high interval death and non-responder rates limit the generalisability to participants surviving 10 years and willing to be rescreened.

Introduction

Chronic heart failure is a clinical syndrome, which occurs following significant pathological insult to the heart acutely or over a period of time, and is associated with poor outcomes for patients.1–3 In many cases, symptoms are insidious in onset and overlap with other conditions meaning diagnosis can be difficult.4 Timely diagnosis is important since early intervention can improve quality of life and survival rates.5 Epidemiological studies have focused on the point prevalence of heart failure, which is around 1–1.5% in the general population rising with age to 10% of those over 75 years in some studies,6 and particularly on the development of heart failure following myocardial infarction7; yet the progression to heart failure in the general community population over time is less well understood. Natriuretic peptides are increasingly being used to determine whether heart failure is more or less likely in patients presenting with symptoms in clinical practice. An N-Terminal-pro-B-type Natriuretic Peptide (NT-proBNP) level less than 400 pg/mL is the current threshold suggested by the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence in England for ruling out a diagnosis of heart failure.8 The European Society of Cardiology recommend a lower cut-off with NT-proBNP level less than 125 pg/mL used to exclude heart failure.5 The role of natriuretic peptide testing, and appropriate cut-off levels, in screening has not been fully established.

The Echocardiographic Heart of England Screening (ECHOES) study was one of the largest community heart failure screening studies in the world and identified an overall prevalence of 2.3% in participants over the age of 45 years in the general population.9 The ECHOES-extension (ECHOES-X) study started 10 years after the ECHOES study completed, to rescreen participants from the original cohort. The aim of the ECHOES-X study was to determine the progression to heart failure over time and to examine the role of natriuretic peptide testing in screening for heart failure in a community population.

Methods

The ECHOES-X study was an observational longitudinal study with the aim of rescreening all surviving participants from the original ECHOES study to determine the prevalence of heart failure and performance of NT-proBNP testing at rescreen.

Original ECHOES study population

Participants in ECHOES-X were derived from the original ECHOES study cohort, which screened 6162 participants from 16 socioeconomically diverse general practices in central England between March 1995 and February 1999.9 A full clinical assessment, combined with echocardiography and ECG, was used to determine the presence of heart failure or left ventricular systolic dysfunction (LVSD; defined as an ejection fraction less than 40%). The European Society of Cardiology criteria published in 1995 were used to determine a diagnosis of heart failure.10 A subgroup of the study population also had a natriuretic peptide level recorded. The ECHOES study comprised four subgroups: general population over age 45; participants with risk factors (hypertension, history of myocardial infarction, angina and diabetes); participants with a prior diagnosis of heart failure; and a group prescribed diuretics. The 5 and 10 year survival rates of the overall cohort and subgroups have been published.11

ECHOES-X study population

All participants involved in the original ECHOES study had their medical record ‘flagged’, to enable the Office for National Statistics to report all deaths to the study team. A total of 2754 participants of the original ECHOES study had died prior to recruitment to the ECHOES-X study. All 3408 surviving participants were eligible to take part in the ECHOES-X study. All 16 practices included in the original ECHOES study agreed to participate in the follow-up. All eligible patients were sent written information about the study prior to screening. Those willing to take part provided written informed consent prior to assessment.

Screening assessment

All participants underwent clinical assessment by a general practitioner with an interest in cardiovascular disease, or a trained research nurse. ECG and echocardiography were carried out by an echocardiographer accredited by the British Society of Echocardiography. A full echocardiographic assessment was performed using a GE Vivid-I machine with spectral Tissue Doppler to assess diastolic function via measurement of E:e′ ratio. In addition, participants had a blood test to measure NT-proBNP levels using a Roche near patient testing device. All participants were also invited to complete a quality-of-life questionnaire. Data collection was carried out between October 2008 and June 2011.

Heart failure diagnostic criteria

The revised 2012 European Society of Cardiology (ESC) chronic heart failure guideline was used to provide a contemporary definition of heart failure.5 Participants with symptoms and an ejection fraction of 50% or less were categorised as heart failure with reduced ejection fraction (HFREF) and those with symptoms, ejection fraction above 50% and evidence of diastolic dysfunction, significant valve disease or arrhythmia were categorised as heart failure with preserved ejection fraction (HFPEF) using a diagnostic algorithm. Of note, natriuretic peptide level was not included in the diagnostic algorithm to allow subsequent calculation of test performance. Where the diagnosis was in doubt, cases were reviewed by a panel of three clinicians with expertise in heart failure. The criteria for objective evidence, and corresponding type of heart failure, are shown in table 1.

Table 1.

ECHOES-X criteria for objective evidence of heart failure

| Abnormality | Criteria | Type of heart failure |

|---|---|---|

| Left ventricular systolic dysfunction | Ejection fraction 40% | HFREF |

| Borderline left ventricular systolic dysfunction | Ejection fraction 41–50% | HFREF |

| Diastolic dysfunction | Diastolic dysfunction defined as E:e′ >13 or E:e′ 8–13 with LV hypertrophy (IVS >1.2 cm) or LA enlargement (>4 cm (males); >3.8 cm (females)) | HFPEF |

| Significant valvular disease | Moderate to severe (grade 2–3) | HFPEF |

| Atrial fibrillation | Diagnosed on ECG | HFPEF |

HFPEF, heart failure with preserved ejection fraction; HFREF, heart failure with reduced ejection fraction; IVS, interventricular septum; LA, left atrium.

Statistical methods

The overall prevalence rate of heart failure, subdivided into HFREF and HFPEF, was calculated for the ECHOES-X cohort. Prevalence of objective abnormalities for participants with and without heart failure was also calculated. The prevalence of heart failure by original diagnostic group was also determined. The general population subgroup was considered alone to determine the progress to new heart failure at rescreening. Finally, the median values of NT-proBNP were calculated for participants with and without heart failure, and performance characteristics for diagnosing heart failure, including sensitivity, specificity, and positive and negative predictive values, were calculated for a NT-proBNP threshold of 125 and 400 pg/mL. No data were available for those who did not attend for rescreening. CIs were calculated using the binomial exact method. Statistical analyses were undertaken using SAS V.9.2 and Stata V.12.1.

Results

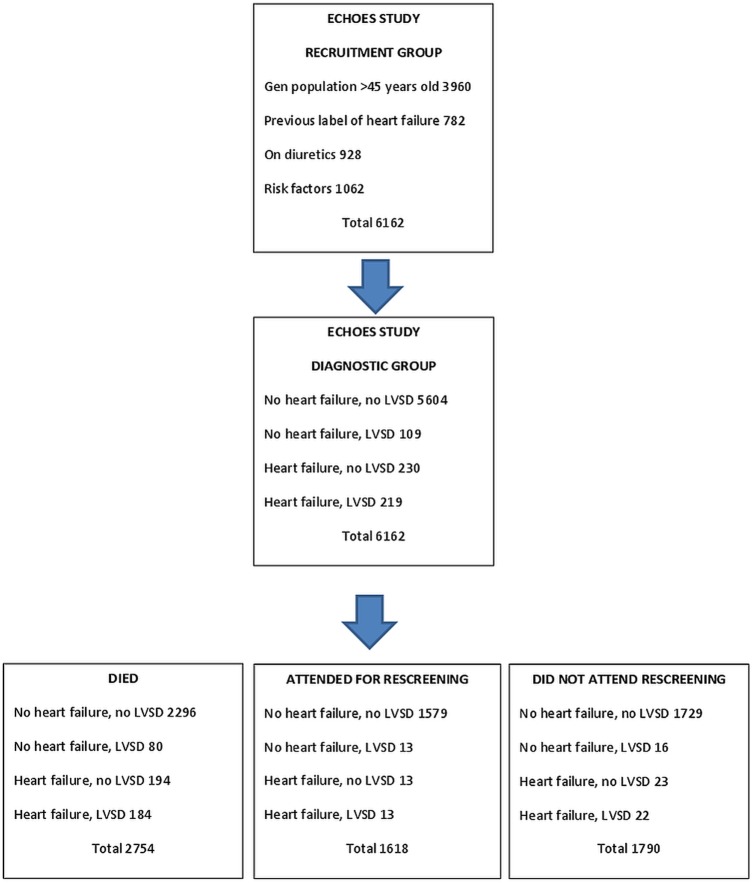

A total of 1618 of 3408 participants who were still alive at the start of the study underwent screening which represented 47% of survivors and 26% of the original ECHOES cohort. Figure 1 provides a summary showing flow and number of participants in the ECHOES and ECHOES-X studies.

Figure 1.

Summary of participant numbers in ECHOES and ECHOES-X studies.

The baseline characteristics of the ECHOES and ECHOES-X cohort are given in table 2. Average age was 64 years in ECHOES and 71 years in ECHOES-X with an equal gender mix in both studies. The mean time between screenings was 13.4 years (SD 1.3, range 10.2–15.5 years).

Table 2.

Baseline characteristics of ECHOES and ECHOES-X cohort

| Characteristic | ECHOES (%) | ECHOES-X (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 64 | 71 |

| Gender male | 3083 (50) | 803 (49.7) |

| Ethnicity | ||

| Caucasian | 5972 (96.9) | 1579 (97.8) |

| Asian | 34 (0.5) | 6 (0.5) |

| Chinese | 3 (0.1) | 1 (0.1) |

| Black | 126 (2.1) | 23 (1.5) |

| Other | 13 (0.2) | 6 (0.4) |

| Not known | 14 (0.2) | 1 (<0.1) |

The number of participants who were rescreened did not respond or had died are shown in table 3, grouped according to their original ECHOES recruitment subgroup. Eighty per cent of those in the ‘previous label of heart failure’ group in the original study had died. Those in the ‘on diuretics’ group also had a higher proportion of deaths (59%) than the general population group (36%).

Table 3.

Number of participants in ECHOES-X from ECHOES cohort by original recruitment group

| Original ECHOES cohort | Original sample size | Number rescreened | Number of non-responders | Number died |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| General population aged 45+ | 3960 | 1242 (31%) | 1299 (33%) | 1419 (36%) |

| Previous label HF | 782 | 59 (8%) | 97 (12%) | 626 (80%) |

| On diuretics | 928 | 162 (17%) | 222 (24%) | 544 (59%) |

| High risk | 1062 | 214 (20%) | 297 (28%) | 551 (52%) |

| Total | 6162* | 1618* (26%) | 1790* (29%) | 2754* (44%) |

*Some participants are in more than one cohort.

HF, heart failure.

Prevalence of heart failure in ECHOES-X

A total of 176 (11%) participants from all four original recruitment groups were classified as having heart failure at rescreening; 103 (58.5%) participants had symptoms and an ejection fraction less than 50% and could therefore be classified as HFREF. The remaining 73 (41.4%) participants with heart failure had an ejection fraction above 50% with evidence of diastolic dysfunction, atrial fibrillation or significant valve disease and were classified as HFPEF. Eighty four participants of 176 (47.7%) with heart failure had more than one objective abnormality. Significant valve disease or atrial fibrillation was present in over one-third of heart failure cases and diastolic dysfunction was found in over 30%. In the general population group alone, there were 73 cases of heart failure out of 1242 participants rescreened giving a prevalence of 5.9% (95% CI 4.6% to 7.3%) in this group.

A total of 1442 participants did not have a diagnosis of heart failure according to the ESC definition but a significant number of this group had one or more objective abnormality of cardiac function. One hundred and five (7%) participants without heart failure had significant valvular disease and 37 (2.6%) had an ejection fraction less than 50%. Diastolic dysfunction was present in 30 (2%) of the no heart failure group. Sixty two (35%) of participants in the heart failure group had atrial fibrillation compared to 36 out of 1442 (2.5%) in the non-heart failure group. Overall the prevalence of atrial fibrillation in the ECHOES-X cohort was 6%.

Outcome of participants from the original ECHOES cohort

Participants in the original ECHOES study were categorised into four diagnostic groups following screening; no heart failure and no LVSD, heart failure and no LVSD, no heart failure and LVSD and heart failure and LVSD. Table 4 shows the ECHOES-X outcome for each group. One hundred and eighty-four out of 219 (84%) participants with heart failure and LVSD and 194 participants out of 230 (84%) with heart failure and no LVSD had died. Eighty out of 109 (73%) participants with no heart failure and LVSD had also died. The largest group was participants with no heart failure and no LVSD from the original ECHOES study and of these, 144 out of 1579 (9.1%) participants rescreened had a label of heart failure.

Table 4.

Outcome for ECHOES cohort by original diagnostic group

| Original ECHOES diagnostic group | Original sample size | Died | HF on rescreen | No HF on rescreen | Non-responders |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No HF and no LVSD | 5604 | 2296 | 144 | 1435 | 1729 |

| HF and no LVSD | 230 | 194 | 12 | 1 | 23 |

| No HF and LVSD | 109 | 80 | 7 | 6 | 16 |

| HF and LVSD | 219 | 184 | 13 | 0 | 22 |

| Total | 6162 | 2754 | 176 | 1442 | 1790 |

HF, heart failure, LVSD, left ventricular systolic dysfunction.

Progression to heart failure

When the original ECHOES study was reported, 5604 participants were assessed and found not to have heart failure or LVSD as shown in table 4. However, ECHOES-X included some participants particularly at high risk of heart failure, so to have a true baseline group to calculate heart failure progression, the general population group should be considered alone (table 5). Data collection for the original ECHOES study took place between 1995 and 1999 and for the ECHOES-X study between 2008 and 2011. On completion of the ECHOES-X study, of the 3834 participants from the general population cohort in the no heart failure, no LVSD group in the original study, 1323 participants had died, 1279 did not respond and 1232 had attended for rescreening. Of the 1232 participants rescreened, 68 (5.5%, 95% CI 4.3% to 6.9%) were found to have heart failure.

Table 5.

Outcome for general population ECHOES cohort by original diagnostic group

| Original ECHOES diagnostic group | Original sample size | Died | HF on rescreen | No HF on rescreen | Non-responders |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No HF and no LVSD | 3834 | 1323 | 68 | 1164 | 1279 |

| HF and no LVSD | 54 | 43 | 2 | 1 | 8 |

| No HF and LVSD | 34 | 19 | 2 | 4 | 9 |

| HF and LVSD | 38 | 34 | 1 | 0 | 3 |

| Total | 3960 | 1419 | 73 | 1169 | 1299 |

HF, heart failure; LVSD, left ventricular systolic dysfunction.

A breakdown of progression to heart failure (including cause) according to original ECHOES recruitment subgroup is shown in table 6. Of those recruited to the original study from the general population over the age of 45, 73 out of 1242 (5.9%, 95% CI 4.6% to 7.3%) rescreened participants had a diagnosis of heart failure in the ECHOES-X study. Forty seven out of 214 (22%, 85% CI 16.6% to 28.1%) participants with risk factors at the time of the original study (hypertension, diabetes, angina or history of myocardial infarction) had heart failure at rescreening. Heart failure was more common still in patients on diuretics or with a previous label of heart failure.

Table 6.

Progression to heart failure according to original ECHOES recruitment subgroup

| Original ECHOES cohort | Original sample size | Number rescreened | Heart failure (% of rescreened group) |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HFREF | HFPEF | Total | |||

| Generation poppulation aged 45+ | 3960 | 1242 | 39 (3.1%) | 34 (2.7%) | 73 (5.9%) |

| Previous label HF | 782 | 59 | 24 (40.7%) | 11 (18.6%) | 35 (59.3%) |

| On diuretics | 928 | 162 | 24 (14.8%) | 17 (10.5%) | 41 (25.3%) |

| Risk factors | 1062 | 214 | 28 (13.1%) | 19 (8.9%) | 47 (22.0%) |

| Total | 6162 | 1618 | 103 (6.4%) | 73 (4.5%) | 176 (10.9%) |

Percentages are proportion of total number in subgroup.

HF, heart failure; HFPEF, heart failure with preserved ejection; HFREF, heart failure with reduced ejection fraction; fraction.

NT-proBNP levels in those with heart failure

All participants in ECHOES-X were invited to have a blood test to assess NT-proBNP. Two attempts were made to take blood in those who provided consent. NT-proBNP level was available for 1511 (93%) participants. The median NT-proBNP level was 772 pg/mL (IQR 454–1338 pg/mL) in those with heart failure and 135 pg/mL (IQR 72–255 pg/mL) in those without heart failure. Thirty three of 176 (18.8%) participants with heart failure had an NT-proBNP level less than 400 pg/mL, the current threshold suggested by the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence in England for ruling out a diagnosis of heart failure. A cut-off of 400 pg/mL had sensitivity for a diagnosis of heart failure of 79.5% (95% CI 72.4% to 85.5%), specificity of 87% (95% CI 85.1% to 88.8%), positive predictive value of 42.2% (95% CI 36.6% to 48.0%) and negative predictive value of 97.3% (95% CI 96.2% to 98.1%). A lower cut-off of NT-proBNP less than 125 pg/mL has a sensitivity of 96.3% (95% CI 92.1% to 98.6%), specificity of 46.8% (95% CI 44.1% to 49.5%), positive predictive value of 17.8% (95% CI 15.3% to 20.5%) and negative predictive value of 99.1% (95% CI 98.0% to 99.7%).

Discussion

Summary of findings

Most patients with heart failure and/or LVSD in the original ECHOES cohort had died in the decade before rescreening started. At rescreening, those with cardiovascular risk factors in the original cohort were more likely to have heart failure on rescreening than those from the general population group. HFPEF was not recorded at the time of the original ECHOES study but accounted for 47% of heart failure cases in the ECHOES-X cohort. This would have been partially captured in the heart failure, no LVSD group of ECHOES. Multiple objective abnormalities were found in patients with heart failure in ECHOES-X suggesting a complex and multifactorial disease. NT-proBNP levels were generally higher in patients with heart failure, yet almost 20% had levels below a 400 pg/mL cut-off for heart failure, meaning this cut-off may be inappropriate for screening in a community setting.

Strengths and weaknesses of the study

The ECHOES study provided one of the largest community heart failure screening cohorts in the world. The ECHOES-X study followed up those still alive with a comprehensive clinical assessment to establish or rule out a diagnosis of heart failure. Progression to heart failure according to baseline group and the prevalence of HFREF versus HFPEF within the cohort are important epidemiological findings which advance our understanding of heart failure in community populations. The presence of multiple echocardiographic abnormalities and the performance of natriuretic peptide testing are important considerations for future screening for heart failure in community settings.

Diagnosis was determined according to the latest guidance from the European Society of Cardiology, which was agreed by a large expert panel of specialists in the field.4 However, the definition requires symptoms to be present for a diagnosis of heart failure to be made, yet patients on known effective treatments such as ACE inhibitors, β-blockers or diuretics may have been rendered asymptomatic by therapy. The estimate of heart failure prevalence is therefore likely to be a conservative one in the ECHOES and ECHOES-X studies.

The ECHOES and ECHOES-X studies were carried out a decade apart during which time there are likely to have been incident cases of heart failure patients who subsequently died. A further limitation of the study is that half of all eligible participants did not attend for rescreening. These results, therefore, give an estimate only for those who survived and were rescreened. Screening in itself requires high attendance rates to confer benefit and this is a consideration for any future screening programme.

A range of ethnic groups and social classes were represented in the ECHOES cohort to ensure the study was generalisable to community populations in Europe.9 The proportion of white Caucasians in ECHOES-X was greater than the UK average and black Africans were under-represented; however, the E-ECHOES study, which specifically included South Asian and Black participants, found rates of heart failure which were similar to the white population.12

The original ECHOES study required a reduced ejection fraction or other structural or functional abnormality, such as valve disease or arrhythmia, for a diagnosis of heart failure and did not attempt to phenotype HFPEF.13 Participants with heart failure due to atrial fibrillation may have partly captured the HFPEF group, but it is likely that the original ECHOES study under-reported the incidence of heart failure overall according to contemporary definitions.7 Echocardiography technology has also improved significantly since the original study; for example, tissue Doppler, which is used to diagnose diastolic dysfunction, was not available in 1995 when the original ECHOES study began.

Comparison with existing literature

There are several registries which document the characteristics of patients admitted to hospital with heart failure.14 Community-based studies, such as the Framingham and Olmsted County studies in the USA or the Rotterdam study in the Netherlands, have followed up patients over a number of decades to describe the epidemiology of cardiovascular diseases, including heart failure.15–17 However, the ECHOES-X study represents the first follow-up study of a large UK cohort previously screened for heart failure. In particular, patients selected from the general population and found not to have heart failure a decade ago were rescreened to find who had developed the disease.

At the time of the original ECHOES study, HFPEF was not recorded as a separate diagnostic category,18 but the follow-up study used the latest echocardiographic definition to identify participants with HFPEF. In ECHOES-X, 73 of a total of 176 (41%) participants with heart failure were classified as HFPEF. Pooled estimates from international community-based studies found an average HFPEF prevalence of 54% (range 40–71%) among those with heart failure.19 The presence of multiple echocardiographic abnormalities was also found in ECHOES-X and has been shown in previous screening studies to be associated with a significant increase in all-cause mortality.20

HFREF and HFPEF were more common in participants with cardiovascular risk factors at baseline, compared with the general population, which is consistent with recent findings from Framingham.12 However, the onset of heart failure timing in Framingham was determined according to outpatient and hospital records. In ECHOES-X, patients were fully screened, including echocardiography and NT-proBNP testing, to actively seek out new heart failure. The ECHOES-X results therefore represent findings from an actively screened community population.

The high prevalence of AF and other cardiac abnormalities in patients from high-risk groups in the ECHOES cohort has been previously reported.21 The ECHOES-X data confirm a high rate of AF and other echocardiographic abnormalities in the heart failure group. The role of NT-proBNP in predicting prognosis of patients with heart failure has also been explored in ECHOES, but only 10% of the original cohort had a recorded natriuretic peptide level.22 A subsequent follow-up of the ECHOES-X cohort (with >90% having a baseline NT-proBNP level recorded) to further assess the value of NT-proBNP in predicting prognosis may be warranted.

Further research and recommendations

Screening highlighted a significant number of patients with heart failure in a population aged 55 and over, and may provide a window of opportunity to intervene early and prevent heart failure progression, ultimately improving quality of life and survival. Screening of the high-risk groups, where prevalence of heart failure is highest, would seem most effective and indeed data from the high-risk groups in the original ECHOES study helped inform the UK Cardiovascular Disease National Service Framework23 and other guidelines,24 recommending that echocardiography be undertaken in all patients following myocardial infarction, but how frequently patients should be rescreened is still unknown.

Other structural and functional abnormalities can also be discovered in asymptomatic patients, which may provide further opportunities to provide timely treatment. For example, operating on patients with significant valvular disease who are well at the time of surgery substantially reduces their perioperative risk.25 Further investigation into the clinical and cost effectiveness of optimal intervention for LVSD is also warranted. The level of natriuretic peptides currently used to rule out heart failure may be too high for a screened population. Nearly 20% of participants in the heart failure group had an NT-proBNP level less than the current threshold in some national guidelines.8

Conclusion

Progression to heart failure is more common in high risk groups but even in the general population is significant over time and screening provides an opportunity to identify new cases. The natriuretic peptide cut-off level for ruling out heart failure must be low enough to ensure cases are not missed in a screened population.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge the contribution of Professor M Frenneaux, Professor G Lip and Dr M K Davies for their support in securing funding for the study.

Footnotes

Contributors: AKR undertook the statistical analysis. LT project managed the study. FDRH was principal investigator. RCD provided clinical cardiology expertise. MD carried out echocardiography. CJT carried out data collection, provided clinical input, developed the diagnostic algorithm and statistical analysis plan (with AKR) and drafted the manuscript.

Funding: The study received competitive funding from the NIHR School for Primary Care Research, NHS Service Support Costs, and complimentary assays from Roche Diagnostics. CJT is funded by an NIHR Doctoral Research Fellowship. None of the funders were involved in study design, analysis, or interpretation of the data or been involved in neither writing the manuscript nor commenting on any drafts. This paper presents independent research funded by the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR). The views expressed are those of the author(s) and not necessarily those of the NHS, the NIHR or the Department of Health.

Competing interests: None.

Disclaimer: The views expressed are those of the author(s) and not necessarily those of the NHS, the NIHR or the Department of Health.

Ethics approval: Full ethical approval was gained from the South Birmingham Local Research Ethics Committee.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

References

- 1.Jhund PS, MacIntyre K, Simpson CR, et al. Long-term trends in first hospitalization for heart failure and subsequent survival between 1986 and 2003: a population study of 5.1 million people. Circulation 2009;119:515–23 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Taylor CJ, Hobbs FDR. Heart failure therapy in patients with coronary artery disease. Curr Opin Pharmacol 2013;13:205–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Stewart S, MacIntyre K, Hole DJ, et al. More ‘malignant’ than cancer? Five-year survival following a first admission for heart failure. Eur J Heart Fail 2001;3:315–22 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jemtel THL, Padaletti M, Jelic S. Diagnostic and therapeutic challenges in patients with co-existent chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and chronic heart failure. J Am Coll Cardiol 2007;49:171–80 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.European Society of Cardiology. Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure 2012. Eur Heart J 2012;33:1787–847 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bleumink GS, Knetsch AM, Sturkenboom MCJM, et al. Quantifying the heart failure epidemic: prevalence, incidence rate, lifetime risk and prognosis of heart failure. Eur Heart J 2004;25:1614–19 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Torabi A, Cleland JGF, Khan NK, et al. The timing of development and subsequent clinical course of heart failure after myocardial infarction. Eur Heart J 2008;29:859–70 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence. Chronic heart failure—management of chronic heart failure in adults in primary and secondary care. NICE, 2010 [Google Scholar]

- 9.Davies M, Hobbs FDR, Davis R, et al. Prevalence of left-ventricular systolic dysfunction and heart failure in the Echocardiographic Heart of England Screening study: a population-based study. Lancet 2001;358:439–44 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.The task force on heart failure of the European Society of Cardiology. Guidelines for the diagnosis of heart failure. Eur Heart J 1995;16:741–51 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Taylor CJ, Roalfe AK, Iles R, et al. Ten-year prognosis of heart failure in the community: follow-up data from the Echocardiographic Heart of England Screening (ECHOES) study. Eur J Heart Fail 2012;14:176–84 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gill PS, Calvert M, Davis R, et al. Prevalence of heart failure and atrial fibrillation in minority ethnic subjects: the Ethnic-Echocardiographic Heart of England Screening Study (E-ECHOES). PLoS ONE 2011;6:e26710. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Borlaug BA, Paulus WJ. Heart failure with preserved ejection fraction: pathophysiology, diagnosis and treatment. Eur Heart J 2011;32:670–9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fonarow GC, Stough WG, Abraham WT, et al. Characteristics, treatments, and outcomes of patients with preserved systolic function hospitalized for heart failure: a report from the OPTIMIZE-HF Registry. J Am Coll Cardiol 2007;50:768–77 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lee DS, Gona P, Vasan RS, et al. Relation of disease pathogenesis and risk factors to heart failure with preserved or reduced ejection fraction. Insights from the Framingham Heart Study of the National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute. Circulation 2009;119:3070–7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Roger VL, Weston SA, Redfield MM, et al. Trends in heart failure incidence and survival in a community-based population. JAMA 2004;292:344–50 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Roger VL. Epidemiology of heart failure. Circ Res 2013;113:646–59 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Westermann D, Kasner M, Steendijk P, et al. Role of left ventricular stiffness in heart failure with normal ejection fraction. Circulation 2008;117:2051–60 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lam CSP, Donal E, Kraigher-Krainer E, et al. Epidemiology and clinical course of heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. Eur J Heart Fail 2011;13:18–28 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Redfield M, Jacobsen SJ, Burnett JC, et al. Burden of systolic and diastolic ventricular dysfunction in the community. JAMA 2003;289:194–202 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Davis RC, Hobbs FDR, Kenkre JE, et al. Prevalence of atrial fibrillation in the general population and in high-risk groups: the ECHOES study. Europace 2012;14:1553–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Taylor CJ, Roalfe AK, Iles R, et al. The potential role of NT-proBNP in screening for and predicting prognosis in heart failure: a survival analysis. BMJ Open 2014;4:e004675. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Department of Health. National Service Framework for Coronary Heart Disease. March 2000. https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/quality-standards-for-coronary-heart-disease-care

- 24.National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence. Myocardial infarction: secondary prevention. NICE, 2007 [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gillinov AM, Mihalijevic T, Blackstone EH, et al. Should patients with severe mitral regurgitation delay surgery until symptoms develop? Ann Thorac Surg 2010;90:481–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.