Abstract

Objective

To determine whether valproate (VPA) monotherapy influences homocysteine metabolism in patients with epilepsy.

Design

Systematic review and meta-analysis.

Data sources

We searched all articles in English through PubMed, Web of Science and EMBASE published up to August 2013 concerning the homocysteine levels in VPA monotherapeutic patients with epilepsy.

Participants

VPA-treated patients with epilepsy (n=266) and matched healthy controls (n=489).

Outcome measures

Heterogeneity between studies was assessed using I2 statistics. Pooled standardised mean difference (SMD) and 95% CIs were calculated using a random effect model.

Results

A total of eight eligible studies were enrolled in our meta-analysis. We compared the plasma levels of homocysteine in VPA-treated patients with epilepsy and healthy controls. There was significant heterogeneity in the estimates according to the I2 test (I2=65.6%, p=0.005). Plasma homocysteine levels in VPA-treated patients with epilepsy were significantly higher than in healthy controls under a random effect model. (SMD, 0.62; 95% CI 0.32 to 0.92). Further subgroup analyses suggested that no significant differences were present when grouped by ethnicity and age, but the risk of heterogeneity in the West Asian group (I2=47.4%, p=0.107) was diminished when compared with that of the overall group (I2=65.6%, p=0.005).

Conclusions

Our meta-analysis indicates that VPA monotherapy is associated with the increase in plasma homocysteine levels in patients with epilepsy. Whether this association is influenced by ethnicity needs further research.

Keywords: Clinical Pharmacology

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This study found that valproate (VPA) may play an important role in the development of hyperhomocysteinaemia in patients with epilepsy.

The number of included studies in our meta-analysis was relatively limited.

In subgroup analysis, the subgroup may be underpowered as the East Asian group had only one study.

Introduction

Homocysteine, a thiol-containing amino acid formed by the demethylation of methionine, is an intermediate product in one-carbon metabolism (OCM). Folic acid and vitamin B12 are cofactors of OCM.1 Deficiency of folic acid and vitamin B12 may lead to elevated plasma homocysteine concentrations. Karabiber et al2 reported that long-term treatment with some antiepileptic drugs (AEDs) for patients with epilepsy might lead to hyperhomocysteinaemia by affecting the blood concentrations of folate, Vitamin B12. Sener et al3 compared patients with epilepsy not receiving AEDs with healthy controls, and found that there were no significant differences in homocysteine levels. For this reason, they thought that suffering from epilepsy was unlikely to directly interfere with homocysteine metabolism. Therefore, rather than being epileptic in origin, AEDs may play an important role in the development of hyperhomocysteinaemia in patients with epilepsy.

An elevated plasma homocysteine concentration is a marker of low folate status and an independent risk factor for arteriosclerosis and fetal malformations. The relationship between hyperhomocysteinaemia and vaso-occlusive diseases is known for a long time. Recent researches have found that the long-term use of older generation AEDs with prominent effects on the enzyme system, including carbamazepine, phenytoin and valproate (VPA), may contribute to the progression of atherosclerosis in patients with epilepsy, which is due to the increase in plasma homocysteine levels.4 High concentrations of total homocysteine are also related to the potential teratogenic effects as there is a 10-fold increased risk for major congenital malformations including neural tube defects in children whose mothers receive AEDs, especially during the first trimester.5 6

VPA is one of the commonly prescribed AEDs in children, as well as in adults. The literature holds controversial views on the homocysteine status in patients under treatment with VPA.7 8 Many of these researches used relatively small sample sizes; therefore, we performed a meta-analysis of all studies published until August 2013 to elucidate whether VPA treatment could lead to the elevation of plasma homocysteine levels in patients with epilepsy.

Materials and methods

Identification of studies

We developed a protocol prior to conducting this research. Eligible studies met the following criteria: (1) effect of VPA on homocysteine in patients with epilepsy; (2) controlled design studies, VPA compared with healthy controls; (3) data of interest (homocysteine concentration) presented as continuous (mean value and SD or SE). The studies were excluded if one of the following existed: (1) metabolic diseases: diabetes mellitus; (2) vitamin supplementation; (3) renal and hepatic impairment; (4) malignancy; (5) vascular diseases: cerebrovascular disease; (6) endocrine diseases: hypothyroidism, thyroid dysfunction; (7) psychiatric disorders: major depression and schizophrenia; (8) smoking and chronic alcohol consumption; (9) drugs: thiazide diuretics, azathioprine.9

We carried out a systematic search for studies reporting the association between plasma homocysteine and VPA monotherapy in PubMed, Web of Science and EMBASE until August 2013, using the following terms: ‘Epilepsy’, ‘Valproate’, ‘Homocysteine’ and ‘Epilep*’. The obtained articles were examined by a quick view at the titles and abstracts and inappropriate articles were rejected in the initial screening. We selected observational case–control studies that evaluated homocysteine levels in participants with epilepsy compared to controls. Any study lacking information regarding specific effects of VPA on homocysteine in patients with epilepsy was also rejected. Non-controlled design studies, reviews and animal or in vitro studies were definitely excluded. Two investigators independently reviewed full text eligibility and reached a consensus on which studies to include for review. We also checked the references of selected articles for any further relevant studies.

Data extraction

Data elements of interest in the studies were extracted by two investigators. Any discrepancies in the extracted data were resolved by a consensus conference between the two investigators. The extracted data elements were listed as: first author, publication year, ethnicity, characteristics of cases and controls (number of cases and controls, mean value and SD of homocysteine in cases and controls).

Quality appraisal of the included research

Two investigators independently assessed the methodological quality of included studies using the Newcastle–Ottawa quality assessment scale (NOS) for case–control studies, which contained nine items that were grouped into three major categories. The maximum for selection was 4, for comparability was 2 and for exposure was 3. The ultimate score of 6 or more was regarded as high quality.

Statistical analysis

The data of interest presented as continuous (mean value and SD) were analysed by using either the weighted mean difference or the standardised mean difference (SMD) as effect measures. The presence of heterogeneity was assessed using the I2 test. If there was no statistical difference about heterogeneity (p > 0.05), a fixed-effect model was applied to analyse the data. Otherwise, a random-effect model would be put into use. To explore the sources of heterogeneity, further subgroup analysis was performed according to ethnicity and age. The stability of the study was also detected by sensitivity analysis. The results of meta-analysis were shown in forest plots. All analyses were conducted using Stata software, V.12.0 (Stata Corp, College Station, Texas, USA).

Results

Literature search and characteristics of eligible studies

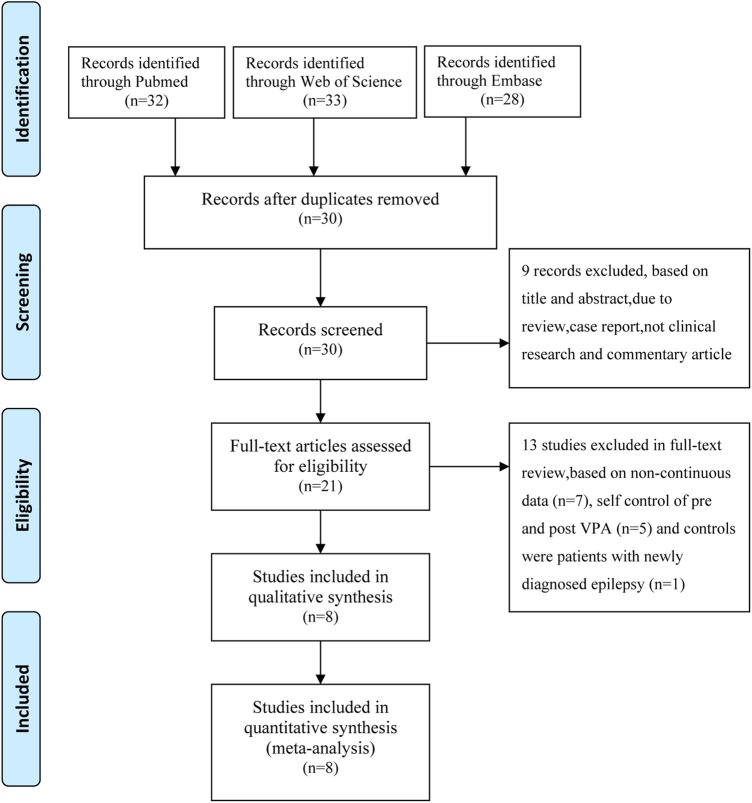

In line with our research strategy, a total of 30 potentially relevant researches were identified in our initial literature search. Finally, our research enrolled eight eligible studies that met the inclusion criteria.1–4 7 10–12 A flow chart showing the study selection is presented in figure 1. The characteristics of eligible studies including VPA therapeutic dosage, duration of VPA monotherapy and plasma homocysteine concentrations (mean±SD) are listed in table 1, which involved 266 patients with epilepsy receiving VPA monotherapy and 489 healthy controls.

Figure 1.

Search strategy for meta-analysis.

Table 1.

Summary of studies included in the meta-analysis

| VPA-treated group |

Healthy controls |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Study | Year | Ethnicity | Dose | Duration | Cases | Hcy (μmol/L) | Cases | Hcy (μmol/L) |

| Verrotti et al1 | 2000 | European | 21.7±6.8 mg/kg | 12 months | 32 | 12.7±7.1 | 63 | 7.9±4.5 |

| Karabiber et al2 | 2002 | West Asian | no | >12 months | 30 | 14±6.8 | 29 | 9.2±2.7 |

| Sener et al3 | 2006 | West Asian | no | 6.5±6.2 years | 22 | 17±8.0 | 11 | 11.5±11.4 |

| Vurucu et al7 | 2007 | West Asian | no | 27.36±21.12 months | 64 | 6.88±2.24 | 62 | 5.52±2.53 |

| Kurul et al12 | 2007 | West Asian | no | 4.78±2.07 years | 8 | 7.18±2.54 | 10 | 7.66±2.34 |

| Yildiz et al10 | 2010 | West Asian | 54.49 mg/mL | >6 months | 19 | 6.73±2.81 | 23 | 6.79±1.95 |

| Belcastro et al11 | 2010 | European | 946.4±172 mg/day | >6 months | 37 | 10.4±3.04 | 231 | 9.1±3.04 |

| Chuang et al4 | 2012 | East Asian | 750–1000 mg/day | 8.7±5.2 years | 54 | 13.84±4.29 | 60 | 9.41±2.65 |

Quality assessment of included literature

The results of quality assessment of included studies using the NOS are shown in table 2. All studies reported that diagnoses of cases and controls were based on criteria and clinical records, and thus all studies were assigned points for ‘adequate definition of cases’ and ‘definition of controls.’ Three studies reported consecutive participants. All studies reached a total quality score of 6 or higher.

Table 2.

Results of quality assessment by the Newcastle–Ottawa Scale

| Study | Selection |

Comparability |

Exposure |

Total | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adequate definition of cases | Representativeness of cases | Selection of controls | Definition of controls | Control for important factor | Control for additional factor | Ascertainment of exposure | Same method to ascertain | Non-response rate | ||

| Verrotti et al1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 7 |

| Karabiber et al2 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 6 |

| Sener et al3 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 6 |

| Vurucu et al7 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 6 |

| Kurul et al12 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 7 |

| Yildiz et al10 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 7 |

| Belcastro et al11 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 7 |

| Chuang et al4 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 7 |

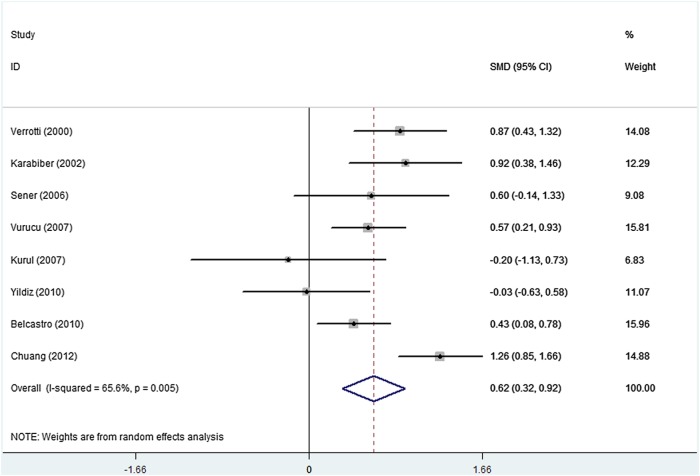

Meta-analysis of plasma homocysteine levels

There was marked heterogeneity when all comparisons were considered (I2=65.6%, p=0.005). On the basis of the comparison of plasma homocysteine levels between patients with epilepsy receiving VPA monotherapy and healthy controls, we found that the plasma homocysteine levels in VPA-treated patients with epilepsy were significantly higher than those in controls (figure 2: SMD, 0.62; 95% CI 0.32 to 0.92).

Figure 2.

Pooled estimate of standardised mean difference and 95% CI of plasma homocysteine levels in patients with epilepsy who received valproate monotherapy.

To explore the sources of heterogeneity among the studies, we performed subgroup analyses by ethnicity (European, West Asian and East Asian) and participants’ age (<18 years and ≥18 years) table 3. Although subgroup analyses suggested that no significant differences were present when grouped by ethnicity and age, the risk of heterogeneity in the West Asian group (I2=47.4%, p=0.107) was diminished as compared with that of the overall group (I2=65.6%, p=0.005). We also conducted sensitivity analysis to evaluate the stability of the meta-analysis. When any single study was deleted, the corresponding pooled SMD was not substantially altered.

Table 3.

Differences between studies by subgroup analysis

| Subgroups | Number of studies | SMD (95% CI) | I2(%) | p Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ethnicity | ||||

| European | 2 | 0.63 (0.19 to 1.06) | 58.0 | 0.005 |

| West Asian | 5 | 0.45 (0.08 to 0.81) | 47.4 | 0.016 |

| East Asian | 1 | 1.26 (0.85 to 1.66) | 0 | <0.001 |

| Age (years) | ||||

| <18 | 5 | 0.52 (0.15 to 0.89) | 58.8 | 0.006 |

| ≥18 | 3 | 0.77 (0.18 to 1.36) | 79.0 | 0.01 |

Discussion

The results of random-effects meta-analysis indicate that VPA-treated patients with epilepsy have higher levels of homocysteine than healthy controls. It suggests that the high plasma level of homocysteine seems to be an important risk factor for VPA monotherapy in patients with epilepsy. This result is in keeping with some data showing that VPA monotherapy may have harmful effects on arteriosclerosis and fetal malformations.

VPA is one of the first-line AEDs for controlling most subtypes of epileptic seizures since its antiepileptic properties were recognised in the early 1960s. As we know, long-term or lifelong VPA therapy is usually required for most patients with epilepsy. However, prolonged VPA therapy is often associated with a wide range of chronic adverse effects including metabolic and endocrine disturbances, atherosclerotic vascular diseases and major congenital malformations.4 13 As an important metabolic product in OCM, homocysteine is a risk factor for atherosclerotic vascular diseases (eg, stroke, myocardiac infarction) and major congenital malformations (eg, neural tube defects-NTDs).14 15

In the circle of OCM, homocysteine participates in two metabolic pathways: the remethylation pathway and the transsulfuration pathway. Some cofactors such as folic acid and Vitamin B12 play important roles in these metabolic pathways. A significant negative correlation was found between the levels of homocysteine and folic acid in patients using AEDs.16 Data on the VPA effects on folic acid are conflicting. Most of the research indicated that VPA decreased the levels of folic acid, but other studies found that the levels of folic acid were not significantly lower in VPA-treated patients compared with healthy controls.1–3 8 In contrast to inducer AEDs that have various effects on enzyme induction in the liver with folic acid, VPA has no effect on hepatic enzyme induction. Further, VPA may impair intestinal absorption of folic acid, and directly interfere with the metabolism of folic acid coenzymes.17

Hyperhomocysteinaemia is frequently caused not only by folic acid deficiency but also by genetic polymorphisms coding for enzymes involved in the OCM. Comparing the plasma homocysteine, folate level and methylentetrahydrofolate reductase (MTHFR) C677T mutation in patients with epilepsy with those in normal controls, Yoo and Hong found that a common MTHFR C677T mutation was a determinant of hyperhomocysteinaemia in patients with epilepsy receiving AEDs, which suggests that a gene–drug interaction induced hyperhomocysteinaemia.18 MTHFR is a key enzyme in the homocysteine remethylation pathway, which plays an important role in the transmethylation of homocysteine to methionine. Ono et al19 indicated that there was a relationship between hyperhomocysteinaemia and the homozygote MTHFR gene variant in patients with epilepsy receiving multidrug therapy, but not in those receiving monotherapy. However, Vurucu et al7 found that the variations in the MTHFR gene had no significant contribution on hyperhomocysteinaemia in patients with epilepsy receiving AEDs therapy. Therefore, further studies are required to clarify the mechanism as to how the homozygous genotype of thermolabile MTHFR affects plasma homocysteine concentrations in patients with epilepsy when they receive VPA monotherapy or other AEDs treatment.

Although our meta-analysis found that the levels of plasma homocysteine were significantly higher in VPA-treated patients with epilepsy than those in controls, heterogeneity also existed. After using the subgroup analysis according to the ethnicity, the risk of heterogeneity in the West Asian group was diminished as compared with that of the overall group. MTHFR as a key enzyme in the homocysteine metabolism has been proved to correlate with the plasma levels of homocysteine. The presence of the T allele (MTHFR C677T) renders the enzyme thermolabile reducing its enzymatic activity, which may cause elevated plasma levels of homocysteine. However, the ethnic composition and the location of sampling can influence the frequency of MTHFR genotypes.20 21 One research indicated that the prevalence of the 677 T allele varied from 9.34% to 40.53% in different ethnic groups, the lowest being demonstrated for South Asians and the highest for East Asians.22 Whether the risk of heterogeneity between studies is influenced by the MTHFR polymorphism needs further research.

Elevated circulating homocysteine, irrespective of the underlying metabolic abnormality, can be detrimental to the vascular structure and function through a number of mechanisms. Hyperhomocysteinaemia is a well-established risk factor for vascular disease such as stroke, myocardiac infarction and peripheral arterial disease.23 As we know, the ultrasonographic determination of the mean common carotid artery intima media thickness (CCA IMT) is a marker to stratify the risk of atherosclerosis. Chuang et al indicated that the levels of plasma homocysteine and the mean CCA IMT were significantly increased in monotherapy with VPA. Moreover, their research demonstrated that the mean CCA IMT was correlated with the duration monotherapy with VPA. Therefore, long-term monotherapy with VPA has been associated with hyperhomocysteinaemia, which leads to an increase in risk of atherosclerosis in patients with epilepsy.4 24

Increased levels of homocysteine are associated with NTD-affected pregnancy, which is regarded as a major risk factor for NTDs.25 As an important intermediate product in OCM, homocysteine may be a better indicator of methyl group supply and therefore more accurately reflects functional transmethylation in genome-wide methylation. Hyperhomocysteinaemia is usually associated with the genome-wide hypomethylation as assessed using the mean long interspersed nucleotide element-1 (LINE-1) methylation in humans. Wang et al found that the reduction in LINE-1 methylation was accompanied by an increased risk of NTDs, indicating that LINE-1 hypomethylation was likely to contribute to the development of NTDs. Since aberrant genomic methylation underlies the complex pathogenesis of NTDs, a high level of homocysteine may interfere with genome wide methylation, which further induces NTDs.26 27 Although a recent study confirmed a specific increase in the risk of NTDs associated with the maternal use of VPA, the mechanism VPA initiating the molecular and biochemical events was still unclear.28 It is probable that therapy with VPA during pregnancy is associated with hyperhomocysteinaemia, which leads to an increase in risk of NTD-affected pregnancy.

Some limitations of this meta-analysis should be considered. First, the number of published studies in our meta-analysis is relatively limited. Second, a significant heterogeneity is found in our study. In subgroup analyses, the subgroup may be underpowered as the East Asian group has only one study. Third, the characteristics of eligible studies have incomplete information about the dosage of VPA monotherapy. Finally, only studies in English are considered.

Conclusions

In conclusion, this meta-analysis suggests that VPA monotherapy is associated with an increase in plasma homocysteine levels in patients with epilepsy. Hyperhomocysteinaemia is an independent risk factor for thrombosis, atherosclerosis and neural tube defects in the offspring of affected women. Therefore, we advise measuring plasma homocysteine in all patients with epilepsy receiving VPA treatment. In addition, folate supplementation to reduce homocysteine levels may be useful in VPA-treated patients with epilepsy.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Contributors: GN and LZ contributed to the conception and design of the experiments. GN, JQ, ZF and YC contributed to the data acquisition and analysis of the data. GN, ZC and JZ contributed the reagents/materials/analysis tools. GN, JQ and LZ wrote the manuscript.

Funding: This work was funded by grants from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (81071050) and the Natural Science Foundation of Guangdong Province of China (S2011020005483).

Competing interests: None.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: All original data extraction are available from the corresponding author at lmzhou56@163.com

References

- 1.Verrotti A, Pascarella R, Trotta D, et al. Hyperhomocysteinemia in children treated with sodium valproate and carbamazepine. Epilepsy Res 2000;41:253–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Karabiber H, Sonmezgoz E, Ozerol E, et al. Effects of valproate and carbamazepine on serum levels of homocysteine, vitamin b12, and folic acid. Brain Dev 2003;25:113–15 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sener U, Zorlu Y, Karaguzel O, et al. Effects of common anti-epileptic drug monotherapy on serum levels of homocysteine, vitamin b12, folic acid and vitamin b6. Seizure 2006;15:79–85 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chuang YC, Chuang HY, Lin TK, et al. Effects of long-term antiepileptic drug monotherapy on vascular risk factors and atherosclerosis. Epilepsia 2012;53:120–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hernandez-Diaz S, Smith CR, Shen A, et al. Comparative safety of antiepileptic drugs during pregnancy. Neurology 2012;78:1692–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zhao W, Mosley BS, Cleves MA, et al. Neural tube defects and maternal biomarkers of folate, homocysteine, and glutathione metabolism. Birth Defects Res A Clin Mol Teratol 2006;76:230–6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Vurucu S, Demirkaya E, Kul M, et al. Evaluation of the relationship between c677t variants of methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase gene and hyperhomocysteinemia in children receiving antiepileptic drug therapy. Prog Neuropsychoph 2008;32:844–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Apeland T, Mansoor MA, Strandjord RE. Antiepileptic drugs as independent predictors of plasma total homocysteine levels. Epilepsy Res 2001;47:27–35 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hu XW, Qin SM, Li D, et al. Elevated homocysteine levels in levodopa-treated idiopathic Parkinson's disease: a meta-analysis. Acta Neurol Scand 2013;128:73–82 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yildiz M, Simsek G, Uzun H, et al. Assessment of low-density lipoprotein oxidation, paraoxonase activity, and arterial distensibility in epileptic children who were treated with anti-epileptic drugs. Cardiol Young 2010;20:547–54 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Belcastro V, Striano P, Gorgone G, et al. Hyperhomocysteinemia in epileptic patients on new antiepileptic drugs. Epilepsia 2010;51:274–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kurul S, Unalp A, Yis U. Homocysteine levels in epileptic children receiving antiepileptic drugs. J Child Neurol 2007;22:1389–92 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tomson T, Battino D, Bonizzoni E, et al. Dose-dependent risk of malformations with antiepileptic drugs: an analysis of data from the EURAP Epilepsy and Pregnancy Registry. Lancet Neurol 2011;10:609–17 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gu Q, Li Y, Cui ZL, et al. Homocysteine, folate, vitamin b12 and b6 in mothers of children with neural tube defects in Xinjiang, China. Acta Paediatr 2012;101:e486–490 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Castro R, Rivera I, Blom HJ, et al. Homocysteine metabolism, hyperhomocysteinaemia and vascular disease: an overview. J Inherit Metab Dis 2006;29:3–20 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Semmler A, Moskau-Hartmann S, Stoffel-Wagner B, et al. Homocysteine plasma levels in patients treated with antiepileptic drugs depend on folate and vitamin b12 serum levels, but not on genetic variants of homocysteine metabolism. Clin Chem Lab Med 2013;51:665–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tumer L, Serdaroglu A, Hasanoglu A, et al. Plasma homocysteine and lipoprotein (a) levels as risk factors for atherosclerotic vascular disease in epileptic children taking anticonvulsants. Acta Paediatrica 2002;91:923–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yoo JH, Hong SB. A common mutation in the methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase gene is a determinant of hyperhomocysteinemia in epileptic patients receiving anticonvulsants. Metabolism 1999;48:1047–51 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ono H, Sakamoto A, Mizoguchi N, et al. The c677t mutation in the methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase gene contributes to hyperhomocysteinemia in patients taking anticonvulsants. Brain Dev 2002;24:223–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Albert MA, Pare G, Morris A, et al. Candidate genetic variants in the fibrinogen, methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase, and intercellular adhesion molecule-1 genes and plasma levels of fibrinogen, homocysteine, and intercellular adhesion molecule-1 among various race/ethnic groups: data from the women's genome health study. Am Heart J 2009;157:777–83 e771 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Stevenson RE, Schwartz CE, Du YZ, et al. Differences in methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase genotype frequencies, between whites and blacks. Am J Hum Genet 1997;60:229–30 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Xuan C, Bai XY, Gao G, et al. Association between polymorphism of methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase (mthfr) c677t and risk of myocardial infarction: a meta-analysis for 8,140 cases and 10,522 controls. Arch Med Res 2011;42:677–85 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Graham IM, Daly LE, Refsum HM, et al. Plasma homocysteine as a risk factor for vascular disease. The European concerted action project. JAMA 1997;277:1775–81 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tan TY, Lu CH, Chuang HY, et al. Long-term antiepileptic drug therapy contributes to the acceleration of atherosclerosis. Epilepsia 2009;50:1579–86 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Felkner M, Suarez L, Canfield MA, et al. Maternal serum homocysteine and risk for neural tube defects in a Texas-Mexico border population. Birth Defects Res A Clin Mol Teratol 2009;85:574–81 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wang L, Wang F, Guan J, et al. Relation between hypomethylation of long interspersed nucleotide elements and risk of neural tube defects. Am J Clin Nutr 2010;91:1359–67 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Fryer AA, Nafee TM, Ismail KM, et al. Line-1 DNA methylation is inversely correlated with cord plasma homocysteine in man: a preliminary study. Epigenetics 2009;4:394–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Alsdorf R, Wyszynski DF. Teratogenicity of sodium valproate. Expert Opin Drug Saf 2005;4:345–53 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.