Abstract

Introduction

The feedback and public reporting of PROMs data aims to improve the quality of care provided to patients. Existing systematic reviews have found it difficult to draw overall conclusions about the effectiveness of PROMs feedback. We aim to execute a realist synthesis of the evidence to understand by what means and in what circumstances the feedback of PROMs data leads to the intended service improvements.

Methods and analysis

Realist synthesis involves (stage 1) identifying the ideas, assumptions or ‘programme theories’ which explain how PROMs feedback is supposed to work and in what circumstances and then (stage 2) reviewing the evidence to determine the extent to which these expectations are met in practice. For stage 1, six provisional ‘functions’ of PROMs feedback have been identified to structure our review (screening, monitoring, patient involvement, demand management, quality improvement and patient choice). For each function, we will identify the different programme theories that underlie these different goals and develop a logical map of the respective implementation processes. In stage 2, we will identify studies that will provide empirical tests of each component of the programme theories to evaluate the circumstances in which the potential obstacles can be overcome and whether and how the unintended consequences of PROMs feedback arise. We will synthesise this evidence to (1) identify the implementation processes which support or constrain the successful collation, interpretation and utilisation of PROMs data; (2) identify the implementation processes through which the unintended consequences of PROMs data arise and those where they can be avoided.

Ethics and dissemination

The study will not require NHS ethics approval. We have secured ethical approval for the study from the University of Leeds (LTSSP-019). We will disseminate the findings of the review through a briefing paper and dissemination event for National Health Service stakeholders, conferences and peer reviewed publications.

Keywords: Realist Synthesis, Patient Reported Outcome Measures, PROMs, feedback, service delivery

Strengths and limitations of this study.

Our realist synthesis will clearly articulate the different ideas and assumptions underlying how the different functions of patient reported outcome measures (PROMs) feedback are intended to work.

The synthesis will identify how, why and in what circumstances the feedback of PROMs data leads to the intended service improvements.

The synthesis will integrate qualitative and quantitative evidence.

The synthesis will provide actionable guidance for policymakers to improve the implementation of PROMs feedback to take account of local circumstances.

The synthesis is very ambitious and the literature in this area is large but uneven, with many more studies of PROMs feedback at an individual level compared to the aggregate level.

There are time constraints that may result in the team focusing on or prioritising some areas of the literature over others.

Background

Policy context and definitions

PROMs are questionnaires that measure patients’ perceptions of the impact of a condition and its treatment on their health.1 Many of these measures were originally designed for use in research to ensure that the patient's perspective was integrated into assessments of the effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of care and treatment.2 These perceptions are now taken to be a key indicator of the quality of care patients receive. Through the introduction of the National PROMs programme in England, the feedback and public reporting of these data aims to improve the quality of care provided to NHS patients.3 4

Alongside the use of PROMs data at an aggregate level, the routine collection and use of PROMs data at the individual patient level has also become more widespread but in a less coordinated way, with individual clinicians using them on an ad hoc basis, often with little guidance.5–7 At the individual level, the intention of PROMs feedback is to enhance communication between patients and clinicians, improve the detection of patient problems, support clinical decision-making about treatment through ongoing monitoring and to empower patients to become more involved in their care.8 9 There are inherent tensions between the different uses of PROMs data that may influence how it is collated and interpreted and thus its success. There is a significant need for research that clarifies the different functions of PROMs feedback and delineates more clearly the processes through which they are expected to achieve their intended outcomes.

Existing evidence

PROMs feedback is a complex intervention and reviewing the evidence of its impact is challenging. PROMs feedback is unavoidably heterogeneous and varies by PROM used, purpose of feedback, patient population, setting, format and timing of feedback, recipients of the information and level of aggregation of the data.8 Systematic reviews using traditional methodologies have found it difficult to draw overall conclusions about the effectiveness of PROMs feedback or to isolate the precise combination of factors that make for its success.10 11 The implementation chain from feedback to improvement has many intermediate steps and may only be as strong as its weakest link.12 At individual and aggregate levels there are many organisational, methodological and logistical challenges to the collation, interpretation and then utilisation of PROMs data.13 For example, at an aggregate level, these include reducing the risk of selection bias as older, sicker patients are less likely to complete PROMs,14 reducing the variation in recruitment rates in PROMs data collection across NHS trusts,15 ensuring that procedures are in place to adequately adjust for casemix,16 17 collecting the data at the right point in the patient's pathway and summarising this information in a way that is interpretable to different audiences.18

Furthermore the success of PROMs feedback is context dependent and these contextual differences influence the precise mechanisms through which it works and its impact on patient care. For example, using PROMs data as an indicator of service quality for surgical interventions in acute care is very different from its use as a quality indicator of general practitioners’ management of long-term conditions within primary care.19 The impact of surgery on disease-specific PROMs and knowledge of the natural variability of scores has been well documented20 but this knowledge is lacking regarding the impact of primary care on EQ-5D scores.

Differences in context can also result in the intervention not working through the intended mechanisms, leading to unintended consequences.21 For example, the feedback and public release of performance data may lead to surgeons refusing to treat the sickest patients to avoid poor outcomes and lower publicly reported ratings.22 Data from the national PROMs programme has been misinterpreted by some as indicating that a significant proportion of varicose vein, hernia and hip and knee replacement should not take place.23 Public reporting of performance data may not improve patient care, as intended, through informing patient choice.24 Rather, patients are often ambivalent about performance data and rely on their GP's opinion when choosing a hospital.25 Finally, research coverage of PROMs feedback is uneven, with more studies (trials and qualitative case studies) examining PROMs feedback at an individual level and few studies examining their use as a performance indicator at a group level.26

In summary, we have identified a number of gaps in our knowledge that this review seeks to address:

How can the tensions between the different purposes of PROMs data collection and their use by different stakeholders be resolved?

Through what processes or mechanisms are the different applications of PROMs feedback supposed to work?

For each application of PROMs data, what are the potential obstacles or unintended consequences of PROMs feedback that may prevent, limit of constrain the intervention improving patient care?

For each application of PROMs data, what are the implementation processes that enable, facilitate or support PROMs feedback to improve patient care?

Aims and objectives

As the applications of PROMs data continue to multiply, our first aim is to identify and classify the various ambitions of PROMs feedback. Our objectives are to:

Produce a comprehensive taxonomy of the ‘programme theories’ underlying these different functions, capture their subtle differences and the tensions that may lie between them and;

Produce logical models of the organisational logistics, social processes and decision-making sequences that underlie the collation, interpretation and utilisation of PROMs data.

We will use these models to identify the potential blockages and unintended consequences of PROMs feedback which may prevent the intervention achieving its intended outcome of improving patient care. This will provide a framework for the review.

To inform the future implementation of PROMs feedback, our second aim is to test and refine these programme theories about how PROMs feedback is supposed to work against existing evidence of how it works in practice. The specific objectives of this synthesis are to:

Identify the implementation processes that support or constrain the successful collation, interpretation and utilisation of PROMs data and;

Identify the mechanisms and circumstances through which the unintended consequences of PROMs data arise and those where they can be avoided.

Our third aim is to use the findings from this synthesis to identify what support is needed to optimise the impact of PROMs feedback and distinguish the circumstances or contexts (eg, settings, patient populations, nature and format of feedback) where PROMs feedback might work best. We will produce guidance to enable NHS decisionmakers to tailor the collection and utilisation of PROMs data to local circumstances and maximise its impact on the quality of patient care.

Review methodology

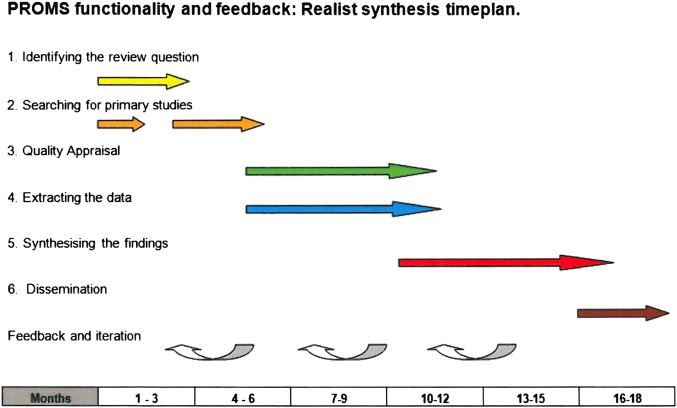

We have chosen to use realist synthesis (RS) as the methodology for this review because it is specifically designed to manage the uneven body of evidence such as is available on PROMs feedback. RS is designed to disentangle the heterogeneity and complexity of the intervention and to make sense of the various contingencies, blockages and unintended consequences that may influence its success. The methodology was developed by one of the coauthors (RP).27 28 Explanation building through theory development, testing and refinement is an iterative process that occurs throughout the review. This can be broken down into six-stages as outlined in figure 1.

Figure 1.

Flow diagram for realist synthesis.

Identifying the review question

The basic unit of analysis in RS is not the intervention but the ideas and assumptions or programme theories that underpin it. Thus, the starting point of RS is to catalogue and build logical models of the different ideas and assumptions about how interventions are supposed to work. In developing the protocol, we have already begun to engage with this process and have identified six functions of PROMs data that will provide an initial structure for the review: At the individual level, PROMs data are utilised to improve patient care by (1) screening for undetected problems; (2) monitoring patients’ problems over time and (3) activating patients and involving the patient in decisions about their care. At the group level, PROMs data may improve patient care by (4) improving the appropriateness of the use of interventions; stimulating quality improvement activities through (5) benchmarking provider performance or (6) through informing decision-making about choice of provider. These are provisional and will be extended and refined during the first phase of the review.

Search strategies: theory

Searching in RS occurs in two main stages: searches to identify the theories underlying the intervention and then searches to identify empirical evidence to test these theories. We will provide detailed elaboration of the different programme theories that underlie these different functions of PROMs data through (1) electronic searching and (2) discussion with the NHS stakeholders and topic experts on our team and a patient group. All search strategies will be tested and refined further during the review.

To identify theories underlying PROMs feedback, we will conduct electronic searches of the grey literature to identify guidance documentation and policy documents and electronic searches of the peer reviewed literature to identify position pieces, comments, letters, editorials and critical pieces which explain how the different applications of PROMs feedback are intended to work. The search strategy for electronic databases will comprise three search concepts A (PROMs), B (improvement and impact resulting from PROMs feedback including the six recognised theories) and C (publication types valuable in eliciting theories). Table 1 lists a small number of potential search terms to illustrate the structure of the theories search. Further terms and synonyms will be tested and added to each concept before the final search combination (A AND B AND C) is run to retrieve papers discussing theories underpinning the impact of PROMs feedback.

Table 1.

Theory search concepts and example search terms

| Search Concepts |

|||

|---|---|---|---|

| A—PROMs | B—PROMs related Impact or Improvement | C—Publication types valuable in eliciting ‘theories’ | |

| Example index terms | Outcome Assessment (Health Care)/Patient Satisfaction/ | Feedback/Quality Improvement/ | Comment/Letter/Editorial/ |

| Example text word terms | Public* reported measure* Patient* outcome* measure* |

Improve* Impact* Implement* |

Comment on Opinion* View* |

*indicates truncation.

Further searches of Google will explore citations of key references found in the electronic database searches, and grey literature. We will also conduct electronic manual searches of Pulse, the Health Service Journal and the BMJ.

Prioritising theories for review

To express each programme theory, we will develop a logical model of how the mobilisation of PROMs data is intended to improve patient care for each function of PROMs data. For each application, we will identify the potential blockages and unintended consequences of PROMs feedback which may prevent or limit the achievement of its intended outcome of improving patient care.

For example, one programme theory hypothesises that the use of PROMs as an indicator of hospital quality will improve patient care by refocusing provider organisational priorities on areas of poor performance and initiating quality improvement activities.27 However, this requires a number of organisational logistics and social processes to be in place to be successful. The data must be collected and collated in a valid way, providers must be able to interpret the data and must accept the data as a valid reflection of the quality of care.13 In order to initiate quality improvement activities, organisations and the individuals within them require the capability and resources to control, improve and design processes for performance to improve. Furthermore, for change to occur organisations require several resources—a reliable flow of useful information; education and training in the techniques of process improvement; investment in the time and change management required to alter core work processes; alignment of organisational incentives with care improvement objectives; leadership to inspire and model care improvement.28

It is likely that we will unearth many different ideas about how each function of PROMs data is supposed to work, their potential blockages and unintended consequences. It will not be possible to review them all thus we will prioritise which programme theories to review in two workshops with NHS decisionmakers, including clinicians, NHS managers, policymakers and patients.

Search strategies: evidence/reviews and primary studies

The programme theories or hypotheses will provide the backbone of the review and determine the search strategy and decisions about study inclusion into the review in order to test and refine these theories. The next stage of the review thus involves an evidence search to identify primary studies that will provide empirical tests of each component of the theory. A starting point will be existing quantitative and qualitative systematic reviews of PROMs feedback,29–31 performance reporting11 and clinician and patient interpretation of performance data.32 The results of these reviews will provide valuable information on outcome patterns (quantitative systematic reviews) and potential mechanisms (qualitative systematic reviews). However, we also anticipate the need to examine specific individual studies within the review to test hypotheses about contextual differences in the ways in which PROMs feedback works. Additional studies will be identified through searching electronic databases. We will search the Cochrane Library, Medline, Embase and the researcher’s own personal libraries for existing reviews with a focussed PROMs search (a combination of concepts A AND B AND C from table 2. Scoping searches indicate 100–200 review abstracts would be retrieved. Initial searching indicates that reviews alone will not provide current evidence that covers known (and unknown) theories. Where relevant reviews are outdated or do not adequately cover our theories we will search electronic databases for relevant studies.

Table 2.

Evidence search concepts and example search terms

| Search Concepts |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A—PROMs | B—PROMs related Impact or Improvement | C—Review publication type | D—Specific PROMS Feedback function or impact for example, Screening | E—Empirical evidence publication types or study designs | |

| Example Index terms | Outcome Assessment (Health Care)/Patient Satisfaction | Feedback/quality improvement/decision-making | Use ‘reviews (maximizes specificity)’ limit | Diagnostic errors/Incidental findings/ | Observational Study/Randomized Controlled Trial/ |

| Example text word terms | Public* reported measure* Patient* outcome* measure* |

Improve* Impact* Implement* |

Review* near to outcome* or data* or PRO | Screen* Undetected problem* Undiscover* condition* |

Evaluation study Follow-up Survey* |

Databases for the evidence search will include MEDLINE, EMBASE, HMIC (all Ovid), Health Business Elite (NHS HDAS) PsycINFO (Ovid), Science Citation Index, Science Conference Proceedings Citation Index (Thomson Reuters) and Dissertation and Theses (ProQuest). All searches will consist of two concepts from table 2 combined as follows (A AND D) but some may include a third concept (E in table 2) to limit the results to particular empirical evidence publication types or study designs (search combination A AND D AND E). Searches will include subject headings and text words. The concept D searches will be constructed individually and will each relate to a function and/or impact of PROMs identified at various points along the logical models developed in phase 1. For example, one concept D search will comprise terms for the function of PROMs feedback as a method of screening for undetected feedback using subject headings and text words such as; ‘mass screening’/, ‘undetected problem’, ‘undiscovered condition’. Initial scoping searches indicate each theory search will identify 200–800 references depending on the extent of evidence for the theory (concept 3), however, since the theories search and reviews search will inform and determine these further evidence searches it is difficult to estimate at this stage. We anticipate developing at least six ‘evidence’ searches to search for evidence on each theory identified in phase 1. Further relevant material will be sought from targeted searches of websites for example, PROQOLID, Google. We will also make extensive use of citation and reference tracking to identify relevant papers.33

Data extraction and quality appraisal

These are combined in RS. Quality appraisal will be conducted throughout the review process and go beyond the traditional approach that only focuses on the methodological quality of studies.34 In RS, assessment of study rigour occurs alongside an assessment of the relevance of the study and occurs throughout the process of synthesis. Quality appraisal is performed on a case-by-case basis, as appropriate to the method utilised in the original study. Where appropriate, we will use relevant methodological checklists (eg, CASP) to assess the methodological quality of included studies. We will also make early use of the standards and guidelines emerging from the Realist And MEta-narrative Evidence Syntheses: Evolving Standards (RAMESES) project.35

Different fragments of evidence are thus sought and utilised from each study. Each fragment of evidence needs to be appraised, as it is extracted, for its relevance to theory testing and the rigour with which it has been produced.34 Data extraction requires active engagement with each document through note taking and text annotation. Evidence will be compiled, stored and annotated using a series of working papers.

Owing to the large volume of research in this area, we anticipate the need to divide up the process of theory testing and thus selecting, abstracting and synthesising the data among the review team. Subgroups will be formed; one person will lead the process and will share and discuss the emerging synthesis with subgroup members who will also read a subsample of the papers reviewed.36 The whole project team will also review the emerging synthesis through a series of working papers shared among the group that will be discussed via face to face and virtual meetings.

Synthesis of evidence

The goal of realist synthesis is to refine our understanding of how the programme works and the conditions and caveats that influence its success, rather than offering a verdict, descriptive summary or mean effect calculation on a family of programmes. Specifically, our synthesis is concerned with understanding the conditions in which blockages or unintended consequences occur (which may prevent or limit the impact of PROMs on patient care) and those in which these blockages can be overcome. Synthesis takes several forms. At its most basic realist synthesis is a form of ‘triangulation’, bringing together information from different primary studies and different study types to explain why a pattern of outcomes may occur. For example, systematic reviews of PROMs feedback at the individual level demonstrate a pattern of outcomes such that PROMs feedback influences communication within the consultation and increases the detection of problems but has much less impact on patient management or outcomes.29 37 This pattern of outcomes suggests there is a ‘blockage’ or ‘obstacle’ in the implementation chain between discussing PROMs findings in the consultation and subsequent action on these findings by clinicians. We can then explore potential explanations for the mechanism through which this blockage occurs and the circumstances in which it might arise.

For example, one longitudinal study exploring changes in the content of the discussion in the consultation over time following PROMs feedback found that PROMs feedback increases the number of times that clinicians discuss symptoms with patients, but not psychosocial functional issues.38 Thus, if functional issues are not discussed, they are unlikely to be addressed; but why are they not discussed? We can look to further qualitative studies for explanation. A focus group study of clinicians' and patients’ views of the utility of PROMs in clinical practice found that clinicians raised concerns that PROMs may raise issues that they cannot do anything about.39 This suggests that perhaps one reason issues are not discussed, despite the availability of PROMs data, is that clinicians perceive they cannot do anything about the problem. In line with this explanation, a qualitative study of oncology consultations in which PROMs data were available found that doctors closed down discussions or did not offer treatment if the problem identified was not perceived as a problem for the patient or perceived as outside of the remit of the clinician.40 41 Further support for this explanation comes from another qualitative study examining communication within oncology consultations which found that oncologists used a number of different strategies to close down the discussion of problems they perceived as outside of their remit to address.41 This ‘mini-synthesis’ illustrates how different studies can be brought together to understand progress (or otherwise) along the implementation chain and identify the circumstances in which blockages occur or may be overcome.

Another form of synthesis, particularly useful when there is disagreement on the merits of an intervention is to ‘adjudicate’ between the contending positions. This is not a matter of providing evidence to declare a certain standpoint correct and another one invalid. Rather adjudication assists in understanding the respects in which a particular programme theory holds and those where it does not. For example, some studies show that poor performing hospitals are more likely to engage in quality improvement activities following performance feedback,42 suggesting the feedback works through motivating hospitals to improve care. However, other studies have found that poor performing hospitals may experience lowered morale and respond by focusing on what is measured to the exclusion of other aspects of care.43 Our review aims to identify explanations for these contrasting findings to identify the circumstances in which the intended mechanism (motivation to improve) and intended outcomes occur (improved care) and those in which unintended mechanisms (lowered morale, tunnel vision) occur. Thus, it seeks to provide an explanation for the whole pattern of outcomes across studies rather than seek out an average effect.

Finally, the main form of synthesis is known as ‘contingency building’. All PROMs feedback programmes make assumptions that they will work under implementation conditions A, B, C and applied in contexts P, Q, R. The purpose of the review is to refine many such hypotheses, enabling us to say that, more probably, A, C, D, E and P, Q, S are the vital ingredients. For example, there is debate about whether the public reporting of hospital performance data is a necessary ingredient to stimulate quality improvement activities,42 or whether such improvement would occur with private feedback to hospitals alone.44 Others have argued that the public reporting and pay for performance can result in greater improvements than public reporting alone.45 Our review would seek to identify the necessary conditions under which the feedback of performance data results in improvements to the quality of care. Similarly, there is also a hypothesis that the feedback of PROMs data at an individual level is more likely to improve patient outcomes if it is accompanied by management guidelines.46 47 Our review will test and refine these hypotheses against the empirical literature to identify the conditions, or contingencies that optimise the impact of PROMs feedback on patient care.

We acknowledge that this is a complex and ambitious review. It may not be possible to produce a comprehensive review of all six of the different functions of PROMs we have so far identified. However, we will ensure that our review prioritises issues of importance to NHS decisionmakers through their involvement at key stages in the review.

Ethics and dissemination

The study will not require NHS ethics approval. We have secured ethical approval for the study from the University of Leeds (LTSSP-019). The protocol has been registered on the PROSPERO database (CRD42013005938). The findings from our review will be used to produce a number of different outputs and disseminated through a number of different mechanisms including a briefing document containing guidance to NHS managers, presentations at national and international conferences including the Annual National PROMs Summit (for NHS staff), the Annual PROMs Research Conference (held by the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine and the King's Fund) and the International Society for Quality of Life Research (ISOQOL) conference, peer reviewed publications in academic journals (eg, BMJ) and articles in practitioner and management journals and newsletters (eg, the Health Services Journal, Pulse).

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Contributors: JG conceived the study and drafted the protocol. JW and JG devised the search strategies. RP advised on the design of the review. RP, JW, NB, JMV, DM, EG, LW, CW, SD and CM read, commented on and revised the protocol.

Funding: This research is funded by the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Health Services and Delivery Research (HS&DR) Programme (project number 12/136/31).

Competing interests: None.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1.Dawson J, Doll H, Fitzpatrick R, et al. The routine use of patient reported outcome measures in healthcare settings. BMJ 2010;340:c186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Guyatt G, Veldhuuyzen van Zanten SJO, Feeny DH, et al. Measuring quality of life in clinical trials: a taxonomy and review. CMAJ 1989;140:1441–48 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.DoH Equity and excellence: liberating the NHS. London:TSO, 2010 [Google Scholar]

- 4.Trust N. Rating providers for quality: a policy worth pursuing? London: Nuffield Trust, 2013 [Google Scholar]

- 5.Haywood K, Garratt A, Carrivick S, et al. Continence specialists use of quality of life information in routine practice: a national survey of practitioners. Qual Life Res 2009;18:423–33 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bausewein C, Simon ST, Benalia H, et al. Implementing patient reported outcome measures (PROMs) in palliative care—users’ cry for help. Health Qual Life Outcomes 2011;9:27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Snyder CF, Aaronson N, Choucair AK, et al. Implementing patient-reported outcomes assessment into clinical practice: a review of the options and considerations. Qual Life Res 2012;21:1305–14 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Greenhalgh J. The applications of PROs in clinical practice: what are they, do they work and why? Qual Life Res 2009;18:115–23 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Higginson IJ, Carr AJ. Measuring quality of life: using quality of life measures in the clinical setting. BMJ 2001;322:1297–300 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Espallargues M, Valderas JM, Alonso J. Provision of feedback on perceived health status to health care professionals: a systematic review of its impact. [see comments.]. [Review] [53 refs] Med Care 2000;38:175–86 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fung HC, Lim YW, Mattke S, et al. Systematic review: the evidence that publishing patient care performance data improves quality of care. Ann Intern Med 2008;148:111–23 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Greenhalgh J, Long AF, Flynn R. The use of patient reported outcome measures in clinical practice: lacking an impact or lacking a theory? Soc Sci Med 2005;60:833–43 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Black N. Patient reported outcome measures could help transform healthcare. BMJ 2013;346:f167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hutchings A, Neuburger J, Grosse Frie K, et al. Factors associated with non-response in routine use of patient reported outcome measures after elective surgery in England. Health Qual Life Outcomes 2012;10:34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hutchings A, Neuburger J, Van der Meulen J, et al. Estimating recruitment rates for routine use of patient reported outcome measures and the impact on provider comparisons. BMC Health Serv Res 2014;14:66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Davies HTO, Crombie IK. Interpreting health outcomes. J Eval Clin Pract 1997;3:187–99 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lilford RJ, Brown CA, Nicholl J. Use of process measures to monitor the quality of clinical practice. BMJ 2007;335:648–50 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hildon Z, Neuburger J, Allwood D, et al. Clinicians’ and patients’ views of metrics of change derived from patient reported outcome measures (PROMs) for comparing providers’ performance of surgery. BMC Health Serv Res 2012;12:171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Valderas JM, Fitzpatrick R, Roland M. Using health status to measure NHS performance: another step into the dark for health reform in England. BMJ Q Saf Healthc 2012;21:352–3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Murray D, Fitzpatrick R, Rogers K, et al. The use of the Oxford hip and knee scores. J Bone Joint Surg Br 2007;89:1010–14 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Werner RM, Asch DA. The unintended consequences of publicly reporting quality information. JAMA 2005;293:1239–44 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Schneider EC, Epstein AM. Influence of cardiac surgery performance reports on referral practices and access to care: a survey of cardiovascular specialists. N Engl J Med 1996;335:251–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.West D, West D. ‘Unpolished’ data to support patient choice. Health Serv J 2010;120:4–5 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Marshall M, McLoughlin V. How do patients use information on health providers? BMJ 2010;341:c5272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Magee H, Davis L-J, Coulter A. Public views on healthcare performance indicators and patient choice. J R Soc Med 2003;96:338–42 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Boyce M, Browne J. Does providing feedback on patient-reported outcomes to healthcare professionals result in better outcomes for patients? A systematic review. Qual Life Res 2013;22:2265–78 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pawson R, Greenhalgh T, Harvey G, et al. Realist review—a new method of systematic review designed for complex policy interventions. J Health Serv Res Policy 2005;10(Suppl 1):21–34 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pawson R. Evidence based policy: a realist perspective. London: Sage, 2006 [Google Scholar]

- 29.Valderas JM, Kotzeva A, Espallargues M, et al. The impact of measuring patient-reported outcomes in clinical practice: a systematic review of the literature. [Review] [64 refs] Qual Life Res 2008;17:179–93 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Boyce M, Browne J, Greenhalgh J. The experiences of professionals with using information from patient-reported outcome measures to improve the quality of healthcare: a systematic review of qualitative research. BMJ Qual Saf 2013;23:508–18 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gonclaves D, Valderas JM, Ricci I, et al. The use of PROMs in clinical practice. Patients and health professionals’ perspectives: a systematic review of qualitative studies. PROSPERO CRD42012003318 2012

- 32.Hildon Z, Allwood D, Black N. Impact of format and content of visual display of data on comprehension, choice and preference: systematic review. Int J Qual Health Care 2012;24:55–64 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Greenhalgh T, Peacock R. Effectiveness and efficiency of search methods in systematic reviews of complex evidence. BMJ 2005;331:1064–65 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Pawson R. Digging for nuggets: how bad research can yield good evidence. Int J Soc Res Methodol 2006;9:127–42 [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wong CK, Greenhalgh T, Westhorp G, et al. RAMESES publication standards: realist synthesis. BMC Med 2013;11:21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rycroft-Malone J, McCormack B, Hutchinson A, et al. Realist synthesis:illustrating the methods for implementation research. Implementation Sci 2012;7:33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Marshall S, Haywood KL, Fitzpatrick R. Impact of patient-reported outcome measures on routine practice: a structured review. [Review] [46 refs] J Eval Clin Pract 2006;12:559–68 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Takeuchi EE, Keding A, Awad N, et al. Impact of patient-reported outcomes in oncology: a longitudinal analysis of patient-physician communication. J Clin Oncol 2011;29:2910–17 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Velikova G, Awad N, Coles-Gale R, et al. The clinical value of quality of life assessment in oncology practice-a qualitative study of patient and physician views. Psychooncology 2008;17:690–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Greenhalgh J, Abhyankar P, McCluskey S, et al. How do doctors refer to patient-reported outcome measures (PROMS) in oncology consultations. Qual Life Res 2013;22:939–50 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Rogers MS, Todd CJ. The ‘right kind’ of pain: talking about symptoms in outpatient oncology consultations. Palliat Med 2000;14:299–307 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hibbard JH, Stockard J, Tusler M. Does publicizing hospital performance stimulate quality improvement efforts? Health Aff 2003;22:84–94 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Mannion R, Davies H, Marshall M. Impact of star performance ratings in English acute hospital trusts. J Health Serv Res Policy 2005;10:18–24 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Guru V, Fremes SE, Naylor CD, et al. Public versus private institutional performance reporting: what is mandatory for quality improvement? Am Heart J 2006;152:573–78 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lindenauer PK, Remus D, Roman S, et al. Public reporting and pay for performance in hospital quality improvement. N Engl J Med 2007;356:486–96 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Rubenstein LV, McCoy JM, Cope DW, et al. Improving patient quality of life with feedback to physicians about functional status. J Gen Intern Med 1995;10:607–14 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Mathias SD, Fifer SK, Mazonson PD, et al. Necessary but not sufficient: the effect of screening and feedback on outcomes of primary care patients with untreated anxiety. J Gen Intern Med 1994;9:606–15 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.