Abstract

Objectives

The aim of this study was to assess the prevalence and determinants of post-tuberculosis chronic respiratory signs, as well as the clinical impact of a low forced expiratory flow between 25% and 75% (FEF25–75%) in a group of individuals previously treated successfully for pulmonary tuberculosis.

Design

This was a cross-sectional study involving individuals in their post-tuberculosis treatment period. They all underwent a spirometry following the 2005 criteria of the American Thoracic Society/European Respiratory Society. Distal airflow obstruction (DAO) was defined by an FEF25–75% <65% and a ratio forced expiratory volume during the first second (FEV1)/forced vital capacity (FVC) ≥ 0.70. Logistic regression models were used to investigate the determinants of persisting respiratory symptoms following antituberculous treatment.

Setting

This study was carried out in the tuberculosis diagnosis and treatment centre at Yaounde Jamot Hospital, which serves as a referral centre for tuberculosis and respiratory diseases for the capital city of Cameroon (Yaounde) and surrounding areas.

Participants

All consecutive patients in their post-tuberculosis treatment period were consecutively enrolled between November 2012 and April 2013.

Results

Of the 177 patients included, 101 (57.1%) were men, whose median age (25th-75th centiles) was 32 (24–45.5) years. At least one chronic respiratory sign was present in 110 (62.1%) participants and DAO was found in 67 (62.9%). Independent determinants of persisting respiratory signs were the duration of symptoms prior to tuberculosis diagnosis higher than 12 weeks (adjusted OR 2.91; 95% CI 1.12 to 7.60, p=0.029) and presence of DAO (2.22; 1.13 to 4.38, p=0.021).

Conclusions

FEF25–75%<65% is useful for the assessment and diagnosis of post-tuberculous DAO. Mass education targeting early diagnosis of pulmonary tuberculosis can potentially reduce the prevalence of post-tuberculosis respiratory signs and distal airflow obstruction.

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This is a cross-sectional study, which precludes making any inference about the direction of the relationships found in the study.

It is most likely that the distal airflow obstruction in our study was the consequence of pulmonary tuberculosis, considering that all patients with known chronic bronchitis prior to tuberculosis occurrence were excluded.

The relatively large number of patients included is a major strength.

This study uses robust methods to assess the relation between post-tuberculosis chronic respiratory symptoms and distal airflow obstruction.

Introduction

Pulmonary tuberculosis, the most common form of tuberculosis, is an important public health challenge worldwide.1 The clinical presentation of pulmonary tuberculosis usually combines general signs with chronic respiratory signs including cough and expectoration.2 The presence of dyspnoea during pulmonary tuberculosis usually indicates the extensive nature of the pulmonary lesions.2 Radiographic and functional sequels are very frequent following tuberculosis treatment, and ad-integrum restitution of the lungs is rather less frequent.3–5 While functional sequels are mostly due to restrictive or mixed functional disorders,6–8 post-tuberculosis airflow obstruction is also present in an important number of patients.8–11 The prevalence of post-tuberculosis airflow obstruction ranges between 5% and 30% across published studies.12–15 Furthermore, pathophysiological studies suggest that lesions affecting exclusively the distal respiratory pathways are possible during pulmonary tuberculosis.10

We are not aware of published studies on post-tuberculosis distal airflow obstruction (DAO) and the possible connection with persistence of respiratory signs following treatment for pulmonary tuberculosis. The assessment of DAO in routine practice is still a challenge with regard to the indices to be used; however, many have suggested mean median expiratory flow or forced expiratory flow between 25% and 75% (FEF25–75%) to be useful for this purpose. The wide variability of this index limits the possibility of defining a reliable optimal threshold for diagnosing DAO.16 Thresholds of 65% or 60% have been applied in children to characterise distal airflow obstruction.17 18 The aim of this study was to determine the prevalence and factors associated with post-tuberculosis chronic respiratory signs, and to assess the clinical impact of a low FEF25–75% in a group of patients successfully treated for pulmonary tuberculosis.

Materials and methods

Study setting and participants

This study was conducted in the Centre for Diagnosis and Treatment of tuberculosis (CDT) of the Yaounde Jamot Hospital (YJH) between November 2012 and April 2013 (6 months duration). This centre has been described in detail previously.19 20 In short, YJH is the reference centre for tuberculosis and chest diseases for the capital city of Cameroon (Yaounde) and surrounding areas. Over the past 5 years, the centre has diagnosed and treated an average of 1600–1800 patients with tuberculosis every year.

All patients aged 18 years and above, successfully treated for bacteriologically proven pulmonary tuberculosis (new case or retreatment), were invited to take part in the study. Bacteriological proofs of pulmonary tuberculosis were based on the presence of acid-fast bacillary (AFB) on at least one direct sputum smear examination,21 or a positive sputum culture for Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Sputum culture and drugs susceptibility test (DST) were performed for all retreatment cases. Patients with any of the following conditions were excluded: patients with treatment failure, patients with resistance to at least one antituberculosis drug, ongoing bacterial pneumonia or within the 4 weeks preceding inclusion, chronic respiratory condition before TB diagnosis, ongoing treatment with β-blockers, physical or mental inability to perform the spirometry test.

Pulmonary tuberculosis treatment

Tuberculosis treatment at the CDT follows the guidelines of the Cameroon National Tuberculosis Control Programme (NTCP) and the WHO recommendations.22 23 Antituberculosis drugs are dispensed free of charge, and treatment regimens used are standard regimens of category I for new patients and of category II for retreatment cases. New cases are treated with a regimen that includes an intensive phase of 2 months duration with rifampicin (R), isoniazid (H), ethambutol (E) and pyrazinamide (Z), followed by a 4-month continuation phase with rifampicin and isoniazid (2RHEZ/4RH). During retreatment, category I medications (R, H, E, Z) are completed with streptomycin (S). Therefore, retreatment cases are treated with RHEZS for 2 months, followed by 1 month on RHEZ and 5 months on RHE (2RHEZS/1RHEZ/5RHE). During the intensive phase, adherence is directly monitored by the healthcare team for patients admitted, and during weekly drug collection in those treated as outpatients. The continuation phase is conducted on the outpatient basis and adherence assessed during monthly visits for scripts renewal and drugs collection.

Monitoring and outcomes of pulmonary tuberculosis treatment

During treatment, sputum smear positive patients are re-examined for AFB at the end of months 2, 5 and 6 for new cases, and at the end of months 3, 5 and 8 for retreated patients. At the end of the treatment, patients are ranked into mutually exclusive categories22 23 as: (1) cured—patient with a negative smear at the last month of treatment and atleast one of the preceding; (2) treatment completed—patient who has completed the treatment and for whom the smear result at the end of the last month is not available; (3) failure—patient with a positive smear at the 5th month or later during treatment; (4) death—death from any cause during treatment; (5) defaulter—patient whose treatment has been interrupted for atleast two consecutive months and (6) transfer—patient transferred to complete his treatment in another centre and whose treatment outcome is unknown.

Procedures

Baseline data collection

In this cross-sectional study, baseline data were collected on sociodemographic, clinical, radiological and biological characteristics of patients. Sociodemographic data collected included age, sex, residence (urban vs rural) and formal level of education. The medical history data included current or former smoking (yes vs no), history of tuberculosis and comorbidities (diabetes mellitus). Clinical details included: duration of symptoms prior to tuberculosis diagnosis, persistent of respiratory symptoms (cough, expectoration, dyspnoea). Patients whose symptoms continued at the end of TB treatment were considered as having persistent respiratory symptoms. Radiographic data were collected on the extension of lungs involvement (number of fields affected), the type of lung lesions (cavities, fibrotic lesions), the presence of pleural effusion and mediastinal or hilar lymph nodes. Biological data included the results of the HIV test result. The study was approved by the administrative authorities of the YJH and institutional review board of the Faculty of Medicine and Biomedical Sciences of the University of Yaounde I.

Ventilatory variables measurement

Spirometric measurements were performed in the month following the completion of TB treatment. They were acquired with a digital turbine pneumotachograph (Spiro USB, Care fusion, Yorba Linda, California USA) following the 1994 American Thoracic Society (ATS) standards.24 All the pulmonary volumes and flow rates were automatically corrected for body temperature and pressure saturated. Measurements were performed under the direct supervision of an experienced pneumologist who is also certified in lung function testing (EWP-Y). The different respiratory indices were measured without bronchodilators and included: forced vital capacity (FVC), forced expiratory volume during the first second (FEV1), forced expiratory flow between 25% and 75% of vital capacity (FEF25–75%) and the ratio FEV1/FVC. The acceptability and reproducibility criteria recommended by the ATS and European Respiratory Society (ERS) guidelines (ATS/ERS guidelines) were respected.16 At least three manoeuvres up to a maximum of eight were performed as required to obtain the flow rate curve (FVC curve). A 1 min resting period was observed between consecutive manoeuvres. Satisfactory exhalation was considered in the presence of any of the following: (1) no change in exhaled volume (plateau on the volume-time curve) for 1 s after an exhalation time of at least 6 s; (2) the presence of a reasonable duration or plateau in the volume–time curve; (3) inability of the subject to continue to exhale.16 24 The largest values for FEV1 and FVC from three acceptable manoeuvres were retained. The authorised difference between the largest values of FVC or FEV1 of the three acceptable manoeuvres was inferior or equal to 0.150 L or 5%. The manoeuvre with the largest sum of FEV1 plus FVC was used to determine FEF25–75%. Predicted values were calculated using reference values based on the Global Lung Initiative (GLI) reference spirometric equations for black.25 Included participants were categorised according to their FEF25–75% into three mutually exclusive groups: normal (FEF25–75%≥80%), intermediate (65%≤FEF25–75%<80%) and low (FEF25–75%<65%). DAO was based on FEF25–75%<65%.

Statistical analysis

Data were analysed with the use of SPSS V.17 for Windows. We have presented categorical variables as count (percentages) and quantitative variables as mean (SD) or median (25th−75th centiles). The group's comparison used χ2 tests for categorical variables and Student t test or non-parametric equivalents for quantitative variables. Logistic regressions were then used to investigate the determinants of persisting chronic respiratory signs. Potential candidate determinants were first investigated in univariate analysis. Significant predictors (based on a threshold probability <0.1) were entered all together in the same multivariable model. A p value <0.05 was used to characterise statistically significant results.

Results

General characteristics of the study population and prevalence of chronic respiratory signs

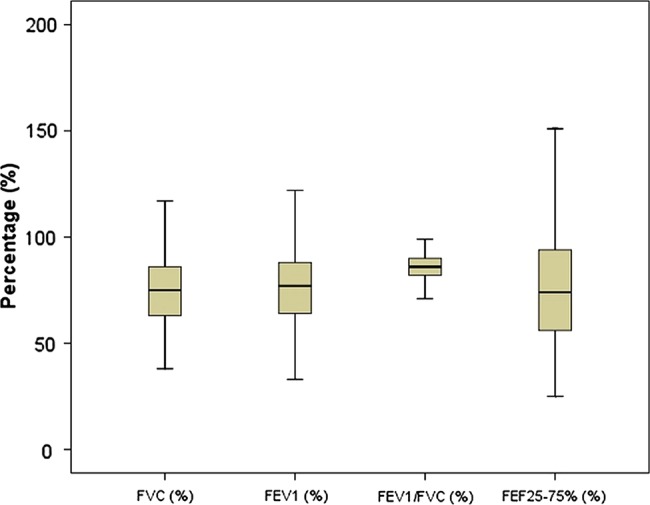

A total of 189 patients were invited to take part in the study. One refused to consent, 10 had incorrect spirometry records (not acceptable and/or not reproducible manoeuvres) while one had an FEV1/FVC <0.70. Of the 177 participants included, 101 (57.1%) were men, whose median age (25th-75th centile) was 32 (24–45.5) years. Thirty-five (19.8%) patients were current or ex-smokers, 23 (13%) had a prior history of pulmonary tuberculosis and 47 (26.6%) had coincident HIV infection. At least one chronic respiratory sign (CRS) was found in 110 (62.1%) patients at the completion of the antituberculosis treatment. Furthermore, 87 (49.2%), 62 (35%) and 99 (55.9%) patients had persisting cough, expectoration and dyspnoea, respectively, at treatment completion (table 1 and figure 1).

Table 1 .

Characteristics of the study population at the end of tuberculosis treatment

| Characteristics | n=177 (%) |

|---|---|

| Baseline clinical characteristics | |

| Male sex | 101 (57.1) |

| Age, years, median (25th–75th) | 32 (24–45.5) |

| Median duration of symptoms before diagnosis, weeks (25th-75th) | 8 (4–12) |

| Current or past smoking | 35 (19.8) |

| Previous pulmonary tuberculosis | 23 (13) |

| HIV infection | 47 (26.6) |

| Diabetes mellitus | 4 (2.3) |

| Radiological signs | |

| Extension of tuberculosis lesions >4 zones | 52/148 (35.1) |

| Cavitary disease | 81/148 (45.8) |

| Persisting respiratory symptoms | |

| Any respiratory symptoms | 110 (62.1) |

| Cough | 87 (49.2) |

| Expectoration | 62 (35.0) |

| Dyspnoea | 99 (55.9) |

| Spirometry values at the end of treatment | |

| FEV1, %, mean (SD) | 76.3 (19.0) |

| FVC, %, mean (SD) | 74.8 (18.2) |

| FEV1/FVC | 0.86 (0.07) |

| FEF25–75%, %, median (25th–75th) | 74 (56–94.5) |

FEF25–75%, forced expiratory flow between 25% and 75%, FEV1, forced expiratory volume in the first second; FVC, forced vital capacity.

Figure 1.

Spirometric indices of study population. FEF25–75%, forced expiratory flow between 25% and 75%, FEV1, forced expiratory volume in 1 s; FVC, forced vital capacity.

Relationship between FEF25–75% and chronic respiratory signs

Table 2 shows the distribution of chronic respiratory signs at treatment completion, according to FEF25–75% categories. Seventy-five patients (42.4%) had normal FEF25–75%, 35 (19.8%) had intermediate FEF25–75%, while 67 (37.9%) had low FEF25–75%. Persisting cough, expectoration and dyspnoea were significantly more frequent among patients with low FEF25–75%. The frequency of at least one persisting chronic respiratory sign was 52% in patients with normal FEF25–75% and 74.6% among those with low FEF25–75% (p=0.005). The related OR was 2.72 (95% CI 1.33 to 5.57).

Table 2.

Frequency of persistent respiratory symptoms and spirometry indices according to FEF25–75%

| Symptoms | FEF25–75%≥80%, n=75 (%) | FEF25–75% between 65% and 80%, n=35(%) | FEF25–75%<65%, n=67 (%) | p Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chronic cough | 28 (37.3) | 17 (48.6) | 42 (62.7) | 0.011 |

| Chronic expectoration | 20 (26.7) | 11 (31.4) | 31 (46.3) | 0.050 |

| Chronic dyspnoea | 38 (50.7) | 16 (45.7) | 45 (67.2) | 0.056 |

| Any chronic respiratory symptoms | 39 (52.0) | 21 (60.0) | 50 (74.6) | 0.020 |

| FEV1, %, median (25th–75th centiles) | 89 (82–100) | 73 (62–82) | 64 (52–73) | <0.001 |

| FVC, % (25th–75th percentiles) | 83 (74–92) | 72 (61–83) | 64 (53–77) | <0.001 |

| FEV1/FVC, mean (SD) | 0.89 (0.04) | 0.86 (0.05) | 0.81 (0.06) | <0.001 |

FEF25–75%, forced expiratory flow between 25 and 75%, FEF25–75%, forced expiratory flow between 25 and 75% of forced vital capacity. FEV1, forced expiratory volume in the first second; FVC, forced vital capacity.

Predictors of persisting respiratory signs at the completion of antituberculosis treatment

Univariable and multivariable adjusted determinants of persisting respiratory signs are shown in table 3. There is no association between smoking volume (pack-years) and persistent CRS (data not shown). Independent predictors of persisting signs were longer duration of symptoms prior to tuberculosis diagnosis (OR 2.91 (95%CI 1.91 to 7.60) for symptoms of duration greater than 12 weeks) and DAO (2.22 (1.13 to 4.38)).

Table 3 .

Determinants of persistent or chronic respiratory symptoms at the end of tuberculosis treatment

| Factors | Crude OR (95% CI) | p Value | Adjusted OR (95% CI) | p Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Male sex | 1.31 (0.71 to 2.44) | 0.387 | / | / |

| Age | 1.01 (0.98 to 1.03) | 0.646 | / | / |

| Duration of symptoms >12 weeks | 3.31 (1.29 to 8.50) | 0.013 | 2.91 (1.12 to 7.60) | 0.029 |

| Smoking | 1.68 (0.75 to 3.76) | 0.209 | / | / |

| Previous pulmonary tuberculosis | 1.86 (0.69 to 4.98) | 0.218 | / | / |

| HIV infection | 0.76 (0.39 to 1.51) | 0.439 | / | / |

| Extension of pulmonary lesions >4 zones | 1.48 (0.71 to 3.07) | 0.292 | / | / |

| Cavitary disease | 1.12 (0.57 to 2.20) | 0.751 | / | / |

| Fibrotic lesions | 1.24 (0.59 to 2.62) | 0.571 | / | / |

| FEF25–75% | 2.45 (1.26 to 4.77) | 0.008 | / | / |

| ≥80% | 1 (reference) | / | ||

| 65%–79% | 1.39 (0.61 to 3.13) | 0.433 | / | / |

| <65% | 2.72 (1.33 to 5.54) | 0.006 | 2.22 (1.13 to 4.38) | 0.021 |

FEF25–75%, forced expiratory flow between 25% and 75% of forced vital capacity.

Relationship of FEF25–75% with other spirometry indices

In this study, FEV1 and FVC were significantly low in patients with low or intermediate FEF25–75% compared to those with normal FEF25–75% (p<0.001). The ratio FEV1/FVC was higher in patients with normal FEF25–75% (0.89) than in those with intermediate (0.86) or low FEF25–75% (0.81) (table 2).

Discussion

The main findings from this study conducted among patients successfully treated for pulmonary tuberculosis in a region of medium endemicity for tuberculosis are the following: (1) the prevalence of persisting chronic respiratory signs after treatment is very high; (2) about two in five patients with normal FEV1/FVC have DAO; (3) DAO is more frequent among patients with persisting chronic respiratory signs after antituberculosis treatment and (4) long duration of symptoms prior to tuberculosis diagnosis is a predictive factor for persisting respiratory signs following successful treatment for tuberculosis.

Functional post-tuberculosis sequels have been largely characterised.4 10 11 However, few studies have reported on persisting chronic respiratory signs following the treatment of pulmonary tuberculosis. Even in the absence of functional sequels, post-tuberculous persisting chronic respiratory signs can negatively impact on the quality of life of individuals. In our series, three-fifths of patients had persisting chronic respiratory signs following treatment for pulmonary tuberculosis. In a recent review from South Africa, chronic bronchitis and dyspnoea were 2–7 times more frequent in people with a history of tuberculosis than in those who had never had tuberculosis.11

Persisting chronic respiratory signs were associated with prolonged duration of symptoms prior to tuberculosis diagnosis in our study. Lee et al13 also found that the presence of bronchial obstruction in the postpulmonary tuberculosis treatment period was influenced by the duration of symptoms prior to starting treatment. Distal bronchial obstruction was found in over a third of our participants. It was independently associated with persisting chronic pulmonary signs, and further associated with a worse profile of spirometry indices. These independent associations suggest that, in addition to confirming the bacteriological cure of the infection, people completing treatment for pulmonary tuberculosis should also be investigated for the presence of functional respiratory signs and indicators of distal airways lesions, in order to optimise their management. There are several inter-related mechanisms to explain the occurrence of post-tuberculous distal bronchial obstruction. Bronchial endothelial inflammation during pulmonary tuberculosis could lead to localised or generalised bronchial obstruction, pulmonary fibrosis and increase airways resistance. The destruction of the lung parenchyma could also reduce the pulmonary compliance and cause the small airways to collapse.10

The cross-sectional nature is the main limitation of this study, precluding any inference about the direction of the relationships found in the study. However, in a historical cohort, Hnidzo et al7 found a gradual decrease in the pulmonary function with increasing episodes of tuberculosis. It is most likely that DAO in our study was the consequence of pulmonary tuberculosis, considering that all patients with known chronic bronchitis prior to tuberculosis occurrence were excluded. The relatively large number of patients included is a major strength.

In conclusion, low FEF25–75% is a useful criterion for diagnosing distal airflow obstruction in patients treated for pulmonary tuberculosis who otherwise have a normal FEV1/FVC ratio. Persisting chronic respiratory signs following treatment for tuberculosis are very frequent and often associated with DAO. Furthermore, a prolonged duration of symptoms prior to starting treatment appears to be a major determinant of persisting post-tuberculous chronic respiratory signs. Sensitisation of the population to consult early with tuberculosis-like symptoms has a potential for improving early diagnosis/treatment and reduction of the prevalence of post-tuberculosis DAO.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Contributors: EWP-Y conceived the study, collected and coanalysed the data and drafted the manuscript. APK contributed to the study design, data analysis, drafting and critical revision of the manuscript. PET-K collected and coanalysed the data and critically revised the manuscript. EA-Z supervised the data collection and critically revised the manuscript. All authors approved the final version of the manuscript.

Funding: This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None.

Patient consent: Obtained.

Ethics approval: Ethics approval was provided by the Institutional Review Board of the Yaounde Jamot Hospital.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

References

- 1.World Health Organisation. Global tuberculosis report 2013. http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/75938/1/9789241564502_eng.pdf (accessed 29 Mar 2014).

- 2.Aït-Khaled N, Alarcón E, Armengol R, et al. Prise en charge de la tuberculose. Guide des éléments essentiels pour une bonne pratique. Sixième édn. Paris: Union Internationale Contre la Tuberculose et les Maladies Respiratorires, 2010:P10 [Google Scholar]

- 3.Al-Hajjaj MS, Joharjy IA. Predictors of radiological sequelae of pulmonary tuberculosis. Acta Radiol 2000;41:533–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sivaranjini S, Vanamail P, Eason J. Six minute walk test in people with tuberculosis sequelae. Cardiopulm Phys Ther J 2010;21:5–10 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pasipanodya JG, Miller TL, Vecino M, et al. Pulmonary impairment after tuberculosis. Chest 2007;131:1817–24 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chung KP, Chen JY, Lee CH, et al. Trends and predictors of changes in pulmonary function after treatment for pulmonary tuberculosis. Clinics (Sao Paulo) 2011;66:549–56 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hnizdo E, Singh T, Churchyard G. Chronic pulmonary function impairment caused by initial and recurrent pulmonary tuberculosis following treatment. Thorax 2000;55:32–8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ramos LM, Sulmonett N, Ferreira CS, et al. Functional profile of patients with tuberculosis sequelae in a university hospital. J Bras Pneumol 2006;32:43–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lee EJ, Lee SY, In KH, et al. Routine pulmonary function test can estimate the extent of tuberculous destroyed lung. ScientificWorldJournal 2012;2012:835031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chakrabarti B, Calverley PM, Davies PD. Tuberculosis and its incidence, special nature, and relationship with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis 2007;2:263–72 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ehrlich RI, Adams S, Baatjies R, et al. Chronic airflow obstruction and respiratory symptoms following tuberculosis: a review of South African studies. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis 2011;15:886–91 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lee SW, Kim YS, Kim DS, et al. The risk of obstructive lung disease by previous pulmonary tuberculosis in a country with intermediate burden of tuberculosis. J Korean Med Sci 2011;26:268–73 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lee CH, Lee MC, Lin HH, et al. Pulmonary tuberculosis and delay in anti-tuberculous treatment are important risk factors for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. PLoS ONE 2012;7:e37978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Menezes AM, Hallal PC, Perez-Padilla R, et al. Tuberculosis and airflow obstruction: evidence from the PLATINO study in Latin America. Eur Respir J 2007;30:1180–5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Akkara SA, Shah AD, Adalja M, et al. Pulmonary tuberculosis: the day after. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis 2013;17:810–13 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Miller MR, Hankinson J, Brusasco V, et al. Standardisation of spirometry. Eur Respir J 2005;26:319–38 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ciprandi G, Capasso M, Tosca M, et al. A forced expiratory flow at 25–75% value <65% of predicted should be considered abnormal: a real-world, cross-sectional study. Allergy Asthma Proc 2012;33:e5–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rao DR, Gaffin JM, Baxi SN, et al. The utility of forced expiratory flow between 25% and 75% of vital capacity in predicting childhood asthma morbidity and severity. J Asthma 2012;49:586–92 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pefura Yone EW, Kengne AP, Kuaban C. Incidence, time and determinants of tuberculosis treatment default in Yaounde, Cameroon: a retrospective hospital register-based cohort study. BMJ Open 2011;1:e000289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yone EW, Kuaban C, Kengne AP. HIV testing, HIV status and outcomes of treatment for tuberculosis in a major diagnosis and treatment centre in Yaounde, Cameroon: a retrospective cohort study. BMC Infect Dis 2012;12:190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Programme National de Lutte contre la Tuberculose. Guide technique pour le personnel de santé. Yaounde, 2012

- 22.National Tuberculosis Control Program. Manual for health personnel. Yaounde, 2006

- 23.World Health Organisation. Treatment of tuberculosis guidelines. Geneva, 2009

- 24.Standardization of Spirometry, 1994 Update. American Thoracic Society. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 1995;152:1107–36 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Quanjer PH, Stanojevic S, Cole TJ, et al. Multi-ethnic reference values for spirometry for the 3–95-yr age range: the global lung function 2012 equations. Eur Respir J 2012;40:1324–43 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.