Abstract

Introduction

Activated protein C (aPC) plays a pivotal role in modulating a severe inflammatory response and is thought to be beneficial for patients with sepsis. However, several meta-analyses of randomised controlled trials (RCTs) show that aPC is not significantly associated with improved survival in critically ill patients with sepsis. One suggestion is that these analyses simply ignored observational evidence. The present study aims to quantitatively demonstrate how observational data can alter the findings derived from synthesised evidence from RCTs by using a Bayesian approach.

Methods and analysis

RCTs and observational studies investigating the effect of aPC on mortality outcome in critically ill patients with sepsis will be included. The quality of included RCTs will be assessed by using the Delphi list. Publication bias will be quantitatively analysed by using the traditional Egger regression test and the Begg rank correlation test. Observational data will be used as the informative prior for the distribution of OR. A power transformation of the observational data likelihood will be considered. Observational evidence will be down-weighted by a power of α which takes values from 0 to 1. Trial sequential analysis will be performed to quantify the reliability of data in meta-analysis adjusting significance levels for sparse data and multiple testing on accumulating trials.

Trial registration number

PROSPERO (CRD42014009562).

Keywords: IMMUNOLOGY

Introduction

Sepsis is defined as systematic inflammatory response syndrome (SIRS) caused by infection.1 Levels of severity vary widely depending on the presence of shock and organ failure. Sepsis is a leading cause of morbidity and mortality in intensive care units. In the USA alone, there were over 750 000 estimated cases in 1995,2 and sepsis accounts for over 25% of admissions to ICUs in Europe.3 Due to its significant impact on global health, every effort has been made to improve the survival of patients with sepsis. One such initiative is the Surviving Sepsis Campaign (SSC) with the objective of reducing mortality from sepsis by 25%.4 Various strategies have been implemented to achieve this aim, such as early goal directed therapy, early use of broad spectrum antibiotics, source control and low tidal volume ventilation. Although the sepsis mortality rate has subsequently declined, the SSC goal is far from being achieved.5

Activated protein C (aPC) has pleiotropic biological effects and plays a pivotal role in modulating the severe inflammatory response which occurs in sepsis. Its biological effects include, but are not limited to, reduction of thrombin production by inactivating factors Va and VIII, and inhibition of IL-1, IL-6 and TNF-α production by monocytes.6 Many observational studies (OS) have shown significantly improved survival outcomes in patients with sepsis treated with aPC compared with controls. Furthermore, these encouraging results have been confirmed in the milestone clinical trial PROWESS. However, the findings have not been replicated in subsequent randomised clinical trials, and thus enthusiasm for aPC has declined.

Randomised controlled trials (RCT) are designed to test the biological efficacy of a particular treatment, while observational studies test the effectiveness of that treatment in the real world setting.7 Differences in efficacy and effectiveness may result from issues related to trial design, patient selection and therapeutic implementation. Some systematic reviews exploring the effect of aPC on sepsis exclusively focused on RCTs while ignoring evidence from OS, and consistently showed that aPC had a neutral effect on survival outcomes.8 9 We propose that although RCTs are the ‘gold standard’ for the definite determination of the clinical efficacy of an intervention, OS cannot simply be ignored in evidence synthesis. Kalil and LaRosa provided a frequentist analysis of both observational and randomised studies, but no Bayesian analyses were performed.10 From the Bayesian perspective, OS can be incorporated into the analysis and an informative prior distribution on the treatment effect derived from the observational data.11 In contrast to previous meta-analysis, we will incorporate observational data into analysis using the Bayesian approach. Furthermore, additional RCTs will be incorporated in order to update the systematic review.

Methods

Search strategy

We will search electronic databases including the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL), PubMed, EBSCO, EMBASE and ISI Web of Science from inception to January 2014. Our core search consists of terms related to aPC and sepsis (see table 1 for the detailed search strategy to be used in PubMed). Strategies will be adapted to other databases. There will be no language restriction. The references of systematic reviews will be reviewed to identify additional eligible articles.

Table 1.

Search strategy performed in PubMed

| Items | Search terms | Number of citations |

|---|---|---|

| 1# | ((activated protein C[Title/Abstract]) OR xigris[Title/Abstract]) OR drotrecogin alfa[Title/Abstract] | 4460 |

| 2# | (sepsis[Title/Abstract]) OR septic shock[Title/Abstract] | 72 635 |

| 3# | (((mortality[Title/Abstract]) OR safety[Title/Abstract]) OR adverse events[Title/Abstract]) OR bleeding[Title/Abstract] | 875 580 |

| 1# AND 2# AND 3# | 531 |

Studies to be included

We will include RCTs and OS for analysis. OS will include: (1) cohort studies using multivariable analysis with aPC treatment as one of the covariates; (2) cohort studies using propensity analysis; (3) case–control studies; (4) studies with both prospective and retrospective designs; and (5) all OS irrespective of their methodological design quality.

Studies to be excluded

We will exclude studies that: (1) do not report mortality as an endpoint; (2) are a secondary analysis of a primary study whose data have been published elsewhere; and (3) only include a single arm so that no comparison can be made between different treatment strategies (eg, such as analysis of risk factors).

Data extraction

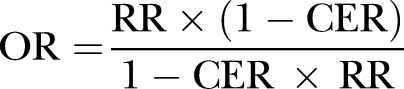

A custom-made form will be used to extract the following data from eligible studies: name of the first author, year of publication, sample size, illness severity scores (APACHE II, SOFA and SAPS), number of deaths in each arm, total number of participants in each arm, bleeding or haemorrhage events in each arm, OR of treatment versus non-treatment for mortality, the method used for covariate adjustment (propensity score analysis, logistic regression model) and the design of the OS (prospective vs retrospective). The adverse event of bleeding will be divided into two categories: major bleeding (terms consist of combinations of ‘massive’, ‘major’ and ‘bleeding’, ‘haemorrhage’) and any bleeding (terms consist of combinations of ‘minor’ and ‘bleeding’, ‘haemorrhage’). If only the risk ratio (RR) is reported, we will transform it into the OR by using standard formula (described elsewhere12):

|

where CER indicates control event rate (same as control group risk). Mortality is defined variably across studies (eg, 28-day, in-hospital, 60-day or 90-day) and we will include all types of definitions for analysis.

Quality assessment of RCTs and OS

Quality assessment of included RCTs will be performed by using the Delphi list, which consists of nine items: sequence generation, allocation concealment, baseline characteristics, eligibility criteria, blindness to outcome assessor, blindness to care provider, blindness to patient, use of point estimate and variability for outcome measures, and use of intention to treat analysis.13 The explanation and rating for each item are given in table 2. Quality assessment of OS will be performed by using the modified Newcastle–Ottawa scale which has been described elsewhere (table 3).14

Table 2.

Quality assessment of randomised controlled trials using tools adapted from the Delphi list

| Items | Explanation | Rating |

|---|---|---|

| Sequence generation | Is the method of sequence generation clearly reported? | Yes/no/unclear |

| Allocation concealment | Is treatment allocation concealment (using an opaque envelope, central allocation) performed? | Yes/no/unclear |

| Baseline characteristics | Are the groups similar at baseline regarding the most important prognostic factors? | Yes/no/unclear |

| Eligibility criteria | Are eligibility criteria clearly specified? | Yes/no/unclear |

| Blindness to outcome assessor | Is the outcome (mortality) assessor blinded? | Yes/no/unclear |

| Blindness to care provider | Is the allocation unknown to the treating physician? | Yes/no/unclear |

| Blindness to patient | Is the patient blinded? | Yes/no/unclear |

| Point estimate and variability | Are the point estimate and variability reported for the outcome measure? | Yes/no/unclear |

| Intention-to-treat | Does the analysis include intention to treat analysis? | Yes/no/unclear |

Table 3.

Quality assessment of included observational studies using the modified Newcastle–Ottawa scale

| Selection | Representativeness of the exposed cohort | This item will be assigned a ‘⋆’ when all eligible patients with severe sepsis or septic shock are included in the analysis during the study period |

| Selection of the non-exposed cohort | This item will be assigned a ‘⋆’ when all eligible patients without aPC treatment are included in the analysis during the study period | |

| Ascertainment of exposure | This item will be assigned a ‘⋆’ when aPC administration is directly obtained from a medical chart, not from reporting by the patient | |

| Outcome of interest is not present at the start of the study | This item will be assigned a ‘⋆’ when the subject is alive at the time of enrolment | |

| Comparability | Comparability of cohorts on the basis of design or analysis | Baseline characteristics of aPC and control groups are comparable. Usually this can be found in table 1 of the original article. |

| Outcome | Assessment of outcome | This item will be assigned a ‘⋆’when mortality is assessed by the investigator, not by the report of the patient's family or next-of-kin |

| Is follow-up long enough for outcome to occur? | Adequate follow-up is carried out during hospital stay, ICU stay or redefined study time | |

| Adequacy of follow-up of the cohort | This item will be assigned a ‘⋆’ when the follow-up rate is >80% |

aPC, activated protein C.

Publication bias

Publication bias will be quantitatively analysed by using the traditional Egger regression test and Begg rank correlation test.15 16 The Begg rank correlation test investigates the relationship between the standardised OR and sample size or variance by using the Spearman rank correlation.17 In the Egger regression test, the standard normal deviate (the OR divided by its SE) is regressed against the estimates precision. The intercept of the regression line is an estimate of asymmetry: the larger its deviation from origin, the more significant the asymmetry.18 A contour enhanced funnel plot will be used to visually assess the presence of publication bias. OR is plotted on the horizontal axis, and precision is plotted on the vertical axis, with asymmetric distribution of component studies representing potential publication bias. Contour lines are added to the plot at conventional statistical significance levels of <0.01, <0.05 and <0.1. A funnel contour enhanced plot can aid interpretation of the funnel plot. If studies are missing in the non-significance area, it is likely that the asymmetry is caused by publication bias. Conversely, if studies are in the significance area, the asymmetry is more likely caused by factors other than publication bias, such as study quality.19

Sensitivity or subgroup analysis

Sensitivity analysis will be performed by excluding studies with poor methodological design. Subgroup analysis will be performed to explore confounding factors such as shock versus non-shock, and the effect of aPC modified by disease severity. If there are enough studies with the same definition of mortality (n>5), subgroup analysis will be performed by different mortality definitions.

Statistical analysis

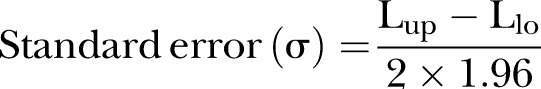

Three key components of Bayesian analysis are prior, likelihood and posterior. The quantity of interest in our study is the OR for mortality. Observational data are used as the informative prior for the distribution of OR. For studies using a logistic regression model for risk adjustment, we will extract adjusted OR and relevant 95% CI for analysis. For studies using propensity matched analysis, the OR from matched samples are calculated. Random effects meta-analysis will be performed to combine the results obtained from OS, by using a Bayesian approach.20 The WinBUGS code for performing the calculation is shown in table 3. The pooled OR will be transformed by natural log to ln(OR) to improve normality. The SE in the natural log scale can be transformed from the 95% credible interval by using the equation:

|

where Lup and Llo represent the upper and lower limits of the 95% credible interval. The precision is the reciprocal of SE.

The framework to incorporate observational data as informative prior is presented by Chen and Ibrahim.11 Model development has been described elsewhere but we repeat it here for the reader's benefit. Let the data from RCTs be denoted by D, and the likelihood of RCTs be denoted by L(θ|D). Suppose we have data from OS which are denoted by D0. Furthermore, let P(θ) denote the prior distribution for θ before OS are incorporated. P(θ) is the initial prior distribution for θ. Given α, the power prior distribution of θ is defined as:

where c0 is the hyperparameter for initial prior, and α is used to weight observational evidence relative to the likelihood of RCT evidence. The value of α controls the impact of observational evidence on P(θ|D0, α). When evidence from RCTs is added to the model, a power transformation of the observational data likelihood is considered:

where P(θ|Data) is the posterior distribution for model quantities, [L(θ|Obs)] is the likelihood function derived from observational data, and L(θ|RCTs) is the likelihood function from RCT data. The weight of observational data is counted by the power α. The power takes values from 0 to 1. If α=0, the observational data are essentially removed from analysis and only RCTs are used for evidence synthesis; if α=1, observational data are taken at their ‘face value’ and not discounted at all. Traditional meta-analyses such as those done in The Cochrane Collaboration included only RCTs that actually render α=0. In our analysis, α will take 12 values ranging between 0 and 1 (0.000001, 0.001, 0.1, 0.2, 0.3, 0.4, 0.5, 0.6, 0.7, 0.8, 0.9, 1.0), resulting in a series of posterior distributions for OR. As shown in table 4, the WinBUGS code is composed of three parts. Part (1) is to repeat meta-analysis of RCTs 12 times, once for each value of α to discount the observational evidence. Part (2) is the meta-analysis model. In this section, i represents the component studies and k indices each of the 12 meta-analyses. These meta-analyses differ from each other only in the prior distribution for the overall pooled effect d, which is represented by:

Table 4.

WinBUGS codes for performing random effects meta-analysis and meta-analysis incorporating observational data

| Random effects meta-analysis | Informative prior with observational data | |

|---|---|---|

| Model† | model { for (i in 1:N) { P[i]<-1/V[i] Y[i]∼dnorm(delta[i], P[i]) delta[i]∼dnorm(d, prec) OR[i]<-exp(delta[i]) } d∼dnorm(0, 1.0E-5) OR[13]<-exp(d) tau∼dunif(0,10) tau.sq<-tau*tau prec<-1/tau.sq } |

model { # (1) create multiple datasets for (i in 1:5) { for (k in 1:12) { rc[i, k]<- rc.dat[i] rt[i, k]<-rt.dat[i] nc[i, k]<-nc.dat[i] nt[i, k]<-nt.dat[i] } } # (2) estimate RCT meta-analysis model for each value of data for (k in 1:12) { for (i in 1:5) { rc[i,k]∼dbin(pc[i,k], nc[i,k]) rt[i,k]∼dbin(pt[i,k], nt[i,k]) logit(pc[i,k])<-mu[i,k] logit(pt[i,k])<-mu[i,k]+delta[i,k] mu[i,k]∼dnorm(0.0, 1.0E-6) delta[i,k]∼dnorm(d[k], prec[k]) or[i,k]<-exp(delta[i,k]) } d[k]∼dnorm(0.33, prec.d[k]) OR[k]<-exp(d[k]) prec[k]<-1/tau.sq[k] tau.sq[k]<-tau[k]*tau[k] tau[k]∼dunif(0,5) } # (3) calculate precision of prior (from meta-analysis of obs studies) downweighted using alpha for (k in 1:12) { prec.d[k]<-alpha[k]*271.3 } } |

| Data‡ | list(Y=c(-0.51083, -0.73397, -0.24846, -0.15082, -0.54473, -0.52763, -0.36817, -0.13926, -0.75502, -0.27444, -0.26136), V=c(1.706611, 0.01954, 0.035483, 0.021832, 0.010326, 0.033478, 0.011817, 0.005765, 0.089499, 0.004559, 0.022782), N=11) |

list(rt.dat=c(0,2,3,2,3), nt.dat=c(67,45,34,56,34), rc.dat=c(2,3,4,2,0), nc.dat=c(44,56,78,123,35), alpha=c(0.0001, 0.2, 0.8) ) |

| Initials§ | list( d = 472.0235128342391, delta = c( 470.6994400270435, 472.3980455275865, 472.201137881263, 472.0198057372273, 471.8605396435204, 470.2850099832592, 469.5829735618464, 473.0258057826344, 470.3932238143316, 469.5792223324207, 469.6419041364815), tau = 0.8303798133648838) list( d = 0, delta = c(0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0), tau = 1) |

list(d = c(0,0,0), delta = structure(.Data = c(**place 5*12=60 initial values here**), .Dim = c(5,12)), mu = structure(.Data = c(**place 5*12=60 initial values here**), .Dim = c(5,12)), tau = c(1,1,1,1,1,1,1,1,1,1,1,1) ) |

†Contents following # are not syntax used for analysis, but are used to annotate corresponding codes.

‡Data are used for illustration purpose and are not obtained from the real analysis.

§Initial values are randomly generated and do not represent the actual values used in analysis.

The mean of prior distribution (the figure 0.33 in the expression is used for illustration purposes, and is not obtained from real analysis) is the natural log of the pooled OR (LOR) estimated from observational data. The pooled OR is estimated with a Bayesian approach with a random effects model. The code for the random effects meta-analysis is shown in table 4. The precision of the prior distribution, prec.d[k], is determined in part (3). Part (3) is to calculate precision of the prior discounted by using α.21

Convergence diagnostics will be explored by running two chains. Simulated values will be compared to identify when they become similar. History plots with different chains superimposed (in different colours) will help to determine convergence. Furthermore, we will use the Brooks–Gelman–Rubin diagnostic to test convergence. The procedure will produce three coloured lines (red, blue and green). Convergence is deemed to occur when the red line settles close to 1 and the blue and green lines converge together.

Trial sequential analysis (TSA) is performed to quantify the reliability of data in meta-analysis adjusting significance levels for sparse data and multiple testing on accumulating trials.22 Trial sequential monitoring boundaries are used to control the risks for type I and II errors and to indicate whether additional trials are needed. A zero-event trial will be handled by the constant continuity correction method with a correction factor of 0.5, that is, 0.5 is added to each cell of the 2×2 table.23 The information size calculation requires the mortality rate in the control group and the minimal effect size for the intervention. We predefined that the mortality in the control group is 30%, and the intervention is able to reduce the relative risk by 10%. The conventional α and β are 0.05 and 0.2, respectively. Meta-analysis will be updated by adding component studies sequentially in the order of publication.

Statistical analysis will be performed by using WinBUGS (Imperial College and MRC, UK) and Stata V.12.0 (College Station, Texas, USA). TSA will be performed by using the software TSA V.0.9 Beta (Copenhagen Trial Unit, 2011).

Results to be reported

Search results will be displayed in a flowchart. Pooled results from conventional meta-analysis techniques will be displayed in forest plots separately for RCTs and OS. Publication bias as shown in funnel plots will also be displayed, again separately for RCTs and OS. The results of TSA will be reported graphically. Random effects meta-analysis using a Bayesian approach will be used to pool summary effects for observational evidence and the results will be reported by using a caterpillar plot. Summary OR will also be plotted against different values of α to examine how observational evidence influences the summary effect. The Brooks–Gelman–Rubin plot will be used to display convergence diagnostics.

Discussion

aPC was once the only approved drug for the treatment of sepsis. However, it was withdrawn from the market after the large clinical trial PROWESS-SHOCK failed to identify any beneficial effect in patients with sepsis. However, in the first place, aPC was approved for use in patients with sepsis because the PROWESS study demonstrated a significant beneficial effect, with the study being stopped early because of its efficacy.24 Furthermore, a large number of OS also showed a large beneficial effect with the use of aPC. Clinicians may be confused by these seemingly differing results. It is still largely unknown whether aPC is beneficial for specific subgroups of patients with sepsis. In this situation, the synthesis of evidence for decision making may help to address these conflicting findings. As a result, a few study groups have conducted systematic reviews and meta-analyses to provide comprehensive and up-to-date evidence for clinical use. The Cochrane Collaboration has also published the results of an updated meta-analysis on the effectiveness of aPC for sepsis, which however showed a neutral effect.8 However, this meta-analysis only included RCTs. There is no doubt that the RCT is the gold standard for supplying evidence for medical decision making and can provide high level evidence on the comparative effectiveness of interventions. However, there are some circumstances where non-randomised evidence should be incorporated in order to estimate effectiveness. These include situations where there are concerns about internal and external validity (only effective in specialised centres or highly selected subjects) and size (estimates are imprecision). Many RCTs in critically ill patients showed a neutral effect of the intervention under investigation. In other situations, initial trials showed a beneficial effect of the intervention which, however, was refuted by a subsequent meta-trial. Reasons for these negative results include timing of enrolment, endpoint selection and heterogeneous subjects.25 26

When both RCTs and OS are available, common practice is to combine data by equally weighting these two types of studies. When evaluating protective ventilation for non-acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) patients, Serpa Neto et al27 combined both RCTs and observational data with equal weights. The use of such a practice is partly due to difficulties in model building under the conventional statistical framework. However, there will be more flexibility for model building under the framework of a Bayesian perspective. The advantages of Bayesian analysis include but are not limited to: (1) it allows for evidence derived from a variety of sources including RCTs and observational data; (2) it enables a direct probability statement regarding the quantity of interest; and (3) all parameter uncertainties can be automatically accounted for.28 We believe that the present study will provide new evidence for the effectiveness of aPC on mortality in patients with sepsis.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Competing interests: None.

Ethics approval: The study was approved by the ethics committee of Jinhua Municipal Central Hospital.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1.Jawad I, Luksic I, Rafnsson SB. Assessing available information on the burden of sepsis: global estimates of incidence, prevalence and mortality. J Glob Health 2012;2:010404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Angus DC, Linde-Zwirble WT, Lidicker J, et al. Epidemiology of severe sepsis in the United States: analysis of incidence, outcome, and associated costs of care. Crit Care Med 2001;29:1303–10 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Vincent JL, Sakr Y, Sprung CL, et al. Sepsis in European intensive care units: results of the SOAP study. Crit Care Med 2006;34:344–53 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Slade E, Tamber PS, Vincent JL. The Surviving Sepsis Campaign: raising awareness to reduce mortality. Crit Care (London, England) 2003;7:1–2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Levy MM, Dellinger RP, Townsend SR, et al. The Surviving Sepsis Campaign: results of an international guideline-based performance improvement program targeting severe sepsis. Crit Care Med 2010;38:367–74 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Christiaans SC, Wagener BM, Esmon CT, et al. Protein C and acute inflammation: a clinical and biological perspective. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 2013;305:L455–66 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nallamothu BK, Hayward RA, Bates ER. Beyond the randomized clinical trial: the role of effectiveness studies in evaluating cardiovascular therapies. Circulation 2008;118:1294–303 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Marti-Carvajal AJ, Sola I, Gluud C, et al. Human recombinant protein C for severe sepsis and septic shock in adult and paediatric patients. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2012;12:CD004388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lai PS, Matteau A, Iddriss A, et al. An updated meta-analysis to understand the variable efficacy of drotrecogin alfa (activated) in severe sepsis and septic shock. Minerva Anestesiol 2013; 79:33–43 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kalil AC, LaRosa SP. Effectiveness and safety of drotrecogin alfa (activated) for severe sepsis: a meta-analysis and metaregression. Lancet Infect Dis 2012;12:678–86 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chen MH, Ibrahim JG. Power prior distributions for regression models. Stat Sci 2000;15:46–60 [Google Scholar]

- 12.Prasad K, Jaeschke R, Wyer P, et al. Tips for teachers of evidence-based medicine: understanding odds ratios and their relationship to risk ratios. J Gen Intern Med 2008;23:635–40 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Verhagen AP, de Vet HC, de Bie RA, et al. The Delphi list: a criteria list for quality assessment of randomized clinical trials for conducting systematic reviews developed by Delphi consensus. J Clin Epidemiol 1998;51:1235–41 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zhang Z, Xu X, Chen K. Lactate clearance as a useful biomarker for the prediction of all-cause mortality in critically ill patients: a systematic review study protocol. BMJ Open 2014;4:e004752-e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Macaskill P, Walter SD, Irwig L. A comparison of methods to detect publication bias in meta-analysis. Stat Med 2001;20:641–54 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Peters JL, Sutton AJ, Jones DR, et al. Comparison of two methods to detect publication bias in meta-analysis. JAMA 2006;295:676–80 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Begg CB, Mazumdar M. Operating characteristics of a rank correlation test for publication bias. Biometrics 1994;50:1088–101 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Egger M, Davey Smith G, et al. Bias in meta-analysis detected by a simple, graphical test. BMJ 1997;315:629–34 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Peters JL, Sutton AJ, Jones DR, et al. Contour-enhanced meta-analysis funnel plots help distinguish publication bias from other causes of asymmetry. J Clin Epidemiol 2008;61:991–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Warn DE, Thompson SG, Spiegelhalter DJ. Bayesian random effects meta-analysis of trials with binary outcomes: methods for the absolute risk difference and relative risk scales. Stat Med 2002;21:1601–23 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Welton NJ, Sutton AJ, Cooper NJ, et al. Generalized evidence synthesis. Evidence synthesis for decision making in healthcare. 1st edn Wiley, 2012:227–33 [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wetterslev J, Thorlund K, Brok J, et al. Trial sequential analysis may establish when firm evidence is reached in cumulative meta-analysis. J Clin Epidemiol 2008;61:64–75 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sweeting MJ, Sutton AJ, Lambert PC. What to add to nothing? Use and avoidance of continuity corrections in meta-analysis of sparse data. Stat Med 2004;23:1351–75 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Angus DC. Drotrecogin alfa (activated)…a sad final fizzle to a roller-coaster party. Crit Care 2012;16:107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Vincent J-L. We should abandon randomized controlled trials in the intensive care unit. Crit Care Med 2010;38:S534–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Han S-H, Sevransky J. Another “negative” acute lung injury trial. Crit Care Med 2012;40:315–16 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Serpa Neto A, Cardoso SO, Manetta JA, et al. Association between use of lung-protective ventilation with lower tidal volumes and clinical outcomes among patients without acute respiratory distress syndrome: a meta-analysis. JAMA 2012;308:1651–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sutton AJ, Abrams KR. Bayesian methods in meta-analysis and evidence synthesis. Stat Methods Med Res 2001;10:277–303 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.