Abstract

Objectives

The aim of this study was to assess the possible mismatch of obstetrical skills between the training offered in Ecuadorian medical schools and the tasks required for compulsory rural service.

Setting

Primary care, rural health centres in Southern Ecuador.

Participants

A total of 92 recent graduated medical doctors during their compulsory rural year.

Primary and secondary outcomes measures

A web-based survey was developed with 21 obstetrical skills. The questionnaire was sent to all rural doctors who work in Loja province, Southern Ecuador, at the Ministry of Health (n=92).

We measured two categories

‘importance of skills in rural practice’ with a five-point Likert-type scale (1= strongly disagree; 5= strongly agree); and ‘clerkship experience’ using a nominal scale divided in five levels: level 1 (not seen, not performed) to level 5 (performed 10 times or more). Spearman's rank correlation coefficient (r) was used to observe associations.

Results

A negative correlation was found in the skills: ‘episiotomy and repair’, ‘umbilical vein catheterisation’, ‘speculum examination’, ‘evaluation of cervical dilation during active labour’, ‘neonatal resuscitation’ and ‘vacuum-assisted vaginal delivery’. For instance ‘Episiotomy and repair’ is important (strongly agree and agree) to 100% of respondents, but in practice, only 38.9% of rural doctors performed the task three times and 8.3% only once during the internship, similar pattern is seen in the others.

Conclusions

In this study we have noted the gap between the medical needs of populations in rural areas and training provided during the clerkship experiences of physicians during their rural service year. It is imperative to ensure that rural doctors are appropriately trained and skilled in the performance of routine obstetrical duties. This will help to decrease perinatal morbidity and mortality in rural Ecuador.

Keywords: MEDICAL EDUCATION & TRAINING, PUBLIC HEALTH, PRIMARY CARE

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This study is the first that assess the perception of obstetrical skills training in recent graduates doing a compulsory rural year in Ecuador.

Possible effects of memory recall of the clerkships experience affects the results even the recent graduates are now facing the problems of doing rural service.

Introduction

Generally, it is assumed that physicians acquire relevant knowledge, skills and attitudes in medical school. After the undergraduate level, graduates must be prepared to work as trainees in a specialty. Some countries include compulsory programmes of various lengths to perform medical services outside of the medical campus or hospitals.1

In Ecuador recent graduates are required to work for the public health system in order to help distribute the medical workforce to rural communities. The rural health facilities are located between 30 min and 2 h from the capital of each province. They vary in size but the majorities are small. They are open 5 days a week and should serve as referral link to the hospitals.2 The recent graduate médico básico serves 1 year in a rural health centre to obtain the license to practice and to apply for further residency training.3 4 This compulsory year exposes them to the realities of providing rural health services and should improve their skills.5

As in most other Latin American countries, in Ecuador, undergraduate medical training is provided in large cities by public and private universities.6 Medical education is still based on Flexner’s pedagogical principles where the hospitals are the foundation of medical teaching and learning during clinical training. This focus on hospital diseases often excludes the common health problems of the general population.6 7

The 6-year undergraduate curriculum comprises of 2 years of mainly lecture-based basic science courses, and 4 years of clinical education, consisting of clerkship rotations, most in hospital settings, between 1 and 3 months of length. During their final year or internship, medical students practice in five rotations in training hospitals in the following areas: internal medicine, surgery, obstetrics and gynaecology, paediatrics and pre-rural.8 9 The traditional teaching of procedural skills is described as ‘see one, do one, teach one’. Tutors teach residents and students according to their own personal experiences.10

After graduation and the lottery for the rural year, all new rural doctors receive a 5-day course to prepare them for the rural service experience. In this training they learn the Ministry of Health administrative process and clinical guidelines.11

Recent data show that in these rural areas, the medical needs of the population are often unmet. For instance, in Ecuador the maternal mortality rate increased from 52.5 in 2007 to 92.6 maternal deaths per 100 000 live births in 2010. Postpartum haemorrhage remains the leading preventable cause of maternal death.12 13 One explanation could be that young, rural doctors are not trained according to the tasks they must perform in those areas, and may pose a potential risk for their patients.14 15

This study was performed to examine if rural doctors are adequately prepared to perform well in rural settings. The purpose is to assess the possible mismatch of obstetrical skills between the training offered in Ecuadorian medical schools and the tasks required of rural service physicians.

Methodology

Instrument and participants

A web-based survey was developed using the procedures of two medical school's curricula: Universidad Técnica Particular de Loja—UTPL and Pontificia Universidad Católica del Ecuador—PUCE. We focused on 21 obstetrical skills divided into three groups: basic obstetrical skills, delivery skills and complication management skills (table 1). The questionnaire was sent to recent graduated medical doctors during their compulsory rural year listed at the Ministry of Health (n=92). They had been working in the rural placement at least 5 months in Loja province, in the Southern Ecuador. Two reminders in a period of 2 months were sent to non-responders. The results were anonymous, but IP addresses were checked to exclude possible redundancy.

Table 1.

Rural doctors’ responses about previous clerkship experience and obstetrical skills importance during the compulsory year in Southern Ecuador

| Clerkship experience* |

Skills importance† |

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 (%) | 2 (%) | 3 (%) | 4 (%) | 5 (%) | 1 (%) | 2 (%) | 3 (%) | 4 (%) | 5 (%) | |

| Obstetrical skills | ||||||||||

| Taking blood pressure | 2 (2) | 88 (98) | 2 (2) | 88 (98) | ||||||

| Taking blood simple | 36 (40) | 54 (60) | 1 (1) | 1 (1) | 88 (98) | |||||

| Cardiotocography interpretation | 12 (13) | 12 (13) | 66 (73) | 15 (17) | 75 (83) | |||||

| Perform speculum examination during pregnancy | 1 (1) | 22 (24) | 8 (9) | 59 (66) | 2 (2) | 2 (2) | 86 (96) | |||

| Pregnancy ultrasound scans | 2 (2) | 14 (16) | 36 (40) | 38 (42) | 2 (2) | 26 (29) | 62 (69) | |||

| Delivery skills | ||||||||||

| Pudendal anaesthesia | 25 (28) | 50 (56) | 1 (1) | 2 (2) | 12 (13) | 2 (2) | 37 (41) | 24 (27) | 27 (30) | |

| Perform normal delivery | 2 (2) | 88 (98) | 4 (4) | 86 (96) | ||||||

| Episiotomy and repair | 8 (9) | 35 (39) | 47 (52) | 35 (39) | 55 (61) | |||||

| Evaluation of cervical dilation during active labour | 5 (6) | 2 (2) | 5 (6) | 78 (87) | 13 (14) | 77 (86) | ||||

| Partogram interpretation | 13 (14) | 77 (86) | 2 (2) | 88 (98) | ||||||

| Obstetrical complications skills | ||||||||||

| Neonatal resuscitation | 2 (2) | 14 (16) | 50 (56) | 24 (27) | 1 (1) | 1 (1) | 88 (98) | |||

| Foley catheterisation | 13 (14) | 13 (14) | 1 (1) | 63 (70) | 1 (1) | 45 (50) | 44 (49) | |||

| Periferic line | 14 (16) | 76 (84) | 1 (1) | 1 (1) | 88 (98) | |||||

| Umbilical line | 26 (28) | 37 (41) | 27 (30) | 1 (1) | 60 (67) | 29 (32) | ||||

| Manual placental removal | 14 (16) | 12 (13) | 24 (27) | 40 (44) | 2 (2) | 24 (63) | 64 (71) | |||

| Postpartum haemorrhage management | 13 (14) | 14 (16) | 63 (70) | 13 (14) | 13 (14) | 64 (71 | ||||

| Forceps-assisted vaginal delivery | 28 (31) | 15 (17) | 35 (39) | 12 (13) | 2 (2) | 13 (14) | 36 (40) | 35 (39) | 4 (4) | |

| Vacuum-assisted vaginal delivery | 1 (1) | 39 (43) | 25 (28) | 5 (6) | 20 (22) | 25 (28) | 37 (41) | 25 (28) | 3 (3) | |

| Emergency C-section | 13 (14) | 28 (31) | 13 (14) | 36 (40) | 2 (2) | 25 (28) | 36 (40) | 27 (30) | ||

| External cephalic versión | 37 (41) | 15 (17) | 38 (42) | 13 (14) | 36 (40) | 41 (46) | ||||

| Repair of obstetric perineal lacerations | 26 (28) | 24 (26) | 40 (44) | 2 (2) | 3 (3) | 85 (94) | ||||

*1=not seen, not performed; 2=demonstrated, but not performed; 3=performed once; 4=performed 3 times; 5=performed+10 times.

†1=strongly disagree; 2=disagree; 3=Neither agree nor disagree; 4=agree; 5=strongly agree.

Two categories were measured. First, the ‘importance of skills in rural practice’ was assessed on a five-point Likert-type scale (1=strongly disagree; 5=strongly agree). Second, participants were asked to reflect on their former ‘clerkship experience’ by using a nominal scale used in research by Peeraer et al. The scale is divided in five levels: level 1 (not seen, not performed), level 2 (demonstrated, but not performed), level 3 (performed one time), level 4 (performed approximately three times) and level 5 (performed 10 times or more). The questionnaire was pilot tested prior to administration for comprehensibility and clarity.

Data was collected using a free online survey tool (KwikSurveys, http://www.kwiksurveys.com/) that allowed checking submissions by IP address.

Ethical issues

The Universidad Técnica Particular de Loja and the research committee of Pontificia Universidad Católica de Ecuador approved the study protocol and the questionnaire. The Chief of the Dirección Provincial de Salud de Loja authorised sending the questionnaire to the rural doctors. In the survey an informed consent form was included to allow the participants to accept or decline participation.

Statistical analysis

Descriptive statistics were performed using SPSS software (V.20.0.0). Spearman's rank correlation coefficient (r) was used to observe associations. The significance level was set at 0.05 for all items.

Results

Ninety rural doctors completed the questionnaire (26 men, 64 women), two respondents did not answer (table 1).

The correlation of perceptions between skill importance in rural areas and clerkship experience of obstetrical skills are summarised in table 2.

Table 2 .

Correlation between previous clerkship experience and obstetrical skills importance perceptions by rural doctors in the Southern Ecuador

| Clerkship experience |

Skills importance |

Spearman’s correlation |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Median | Range* | Median | Range† | Rs | p Value | |

| Obstetrical skills | ||||||

| Taking blood pressure | 5 | 1 (4–5) | 5 | 1 (4–5) | −0.016 | 0.880 |

| Taking blood simple | 5 | 2 (3–5) | 5 | 3 (2–5) | 0.188 | 0.080 |

| Cardiotocography interpretation | 5 | 2 (3–5) | 5 | 1 (4–5) | 0.630‡ | 0.000 |

| Perform speculum examination during pregnancy | 4 | 4 (1–5) | 5 | 2 (3–5) | 0.211‡ | 0.048 |

| Pregnancy ultrasound scans | 4 | 3 (2–5) | 5 | 3 (2–5) | 0.066 | 0.540 |

| Delivery skills | ||||||

| Pudendal anesthesia | 2 | 4 (1–5) | 4 | 3 (2–5) | 0.553‡ | 0.000 |

| Perform normal delivery | 5 | 2 (3–5) | 5 | 1 (4–5) | −0.020 | 0.852 |

| Episiotomy and repair | 5 | 1 (3–5) | 5 | 1 (4–5) | −0.308‡ | 0.004 |

| Evaluation of cervical dilation during active labour | 5 | 3 (1–5) | 5 | 1 (4–5) | 0.284‡ | 0.007 |

| Partogram interpretation | 5 | 2 (3–5) | 5 | 2 (3–5) | −0.041 | 0.708 |

| Obstetrical complications skills | ||||||

| Neonatal resuscitation | 4 | 3 (2–5) | 5 | 2 (3–5) | 0.270‡ | 0.011 |

| Foley catheterisation | 5 | 3 (2–5) | 4 | 3 (2–5) | 0.527‡ | 0.000 |

| Periferic line | 5 | 3 (2–5) | 5 | 3 (2–5) | 0.366‡ | 0.000 |

| Umbilical line | 2 | 2 (1–3) | 4 | 2 (3–5) | −0.338‡ | 0.001 |

| Manual placental removal | 3 | 4 (1–5) | 5 | 2 (3–5) | 0.822‡ | 0.000 |

| Postpartum haemorrhage management | 5 | 2 (3–5) | 5 | 2 (3–5) | 0.931‡ | 0.000 |

| Forceps-assisted vaginal delivery | 3 | 3 (1–4) | 3 | 4 (1–5) | 0.084 | 0.441 |

| Vacuum-assisted vaginal delivery | 2 | 2 (1–5) | 3 | 3 (2–5) | 0.252‡ | 0.018 |

| Emergency C-section | 4 | 4 (1–5) | 4 | 3 (2–5) | −0.016 | 0.882 |

| External cephalic versión | 2 | 4 (1–5) | 4 | 2 (3–5) | −0.109 | 0.313 |

| Repair of obstetric perineal lacerations | 4 | 2 (3–5) | 5 | 2 (3–5) | −0.108 | 0.315 |

*1=not seen, not performed; 2=demonstrated, but not performed; 3=performed once; 4=performed 3 times; 5=performed + 10 times.

†1=strongly disagree; 2=disagree; 3=Neither agree nor disagree; 4=agree; 5=strongly agree.

‡Correlation is significant.

A positive correlation means if the perception of importance in the internship increases, the internship experience also increases. The data shows correlation levels between the perceptions. They can be divided into very high positive correlation (r =0.9–1), high positive correlation (r=0.7–0.9), moderate positive correlation (r=0.5–0.7) and low positive correlation (r=0.3–0.5).

The negative correlation means that one variable increase as another decrease. We found only a level of low negative correlation (r=−0.3 to −0.5). The negligible correlation means that there is no relationship between the two variables. It can be positive or negative correlation (r=0.0 to 0.3 or 0.0 to −0.3).

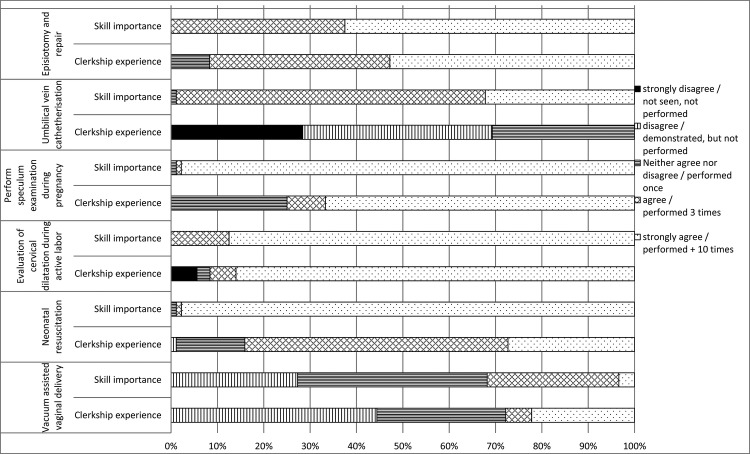

We found six skills with negligible or negative correlation. In those, we show the differences in the associations between the skill importance and clerkship experience in figure 1.

Figure 1.

Differences in the relationship between the perceptions of clerkship experience and skills importance of obstetrical skills in rural doctors with negligible or negative correlations (r=0.0 to 0.3 or −0 to −0.3 or r=−0.3 to −0.5).

As the data obtained shows the skill ‘Episiotomy and repair’ is important (strongly agree and agree) to 100% of respondents. However in practice, only 38.9% of rural doctors performed the task three times and 8.3% only once during the internship. For ‘umbilical vein catheterisation’ is important in 98.9% of respondents and 30% have practiced once, 41.1% have seen and 28.8% have not seen nor practice at all during the internship.

The skill ‘speculum examination during pregnancy’ is important to 98.8% of rural doctors; during the internship only 8.3% of rural doctors performed the task three times and 25% only once. The ‘evaluation of cervical dilation during active labour’ is important for 100% of respondents, 86% have practiced the skills more than 10 times, 5.6% at least three times, 2.8% once and 5.6% had not seen nor performed during the clerkships. The ‘neonatal resuscitation’ skill is important for 98.8% of respondents, 26.7% have performed more than 10 times, 55.6% three times and 15.5% have practiced once during the clerkships. The skill ‘vacuum-assisted vaginal delivery’ is important for 31.8% of rural doctors, 22% have practiced more than 10 times, 5.6% three times, 27.8% only once and 44.4% only seen nor practiced during the internship.

Discussion

This study shows that six skills are appropriately practiced in the internships while six other skills may not have been adequately learned. Skills rated important for rural practice have not been seen nor practiced by 6–45% of respondents while others skills, between 8% and 14%, have been practiced only once during the internship. The results indicate lack of practice for several of the most frequent and important obstetrical skills in undergraduate curriculum in Ecuador.

We did not ask the rural doctors to reflect back on their responses, although this it could diminish the subjectivity of the results. The variable perceptions could be determined by the experiences in different clerkships. This can be a reason why many respondents interpreted most of the skills as ‘important’.16

The data suggest the partial mismatch in Ecuadorian undergraduate curricula with the skills required of rural service physicians. Other studies have identified such mismatch.17––21 In Ecuador because of the use of young graduates in rural areas, these mismatches directly influence epidemiological data and may increase morbidity and even maternal or neonatal mortality.

Medical competence may be defined as the integration of knowledge, skills and attitudes to enable proper management of health problems.22––24 However, of the skills included in this study, the minimum number of procedures that needs to be performed in the undergraduate curriculum to ensure competency and adequate performance in the subsequent rural year is unknown. We found that the basic doctors did not have the possibility of training during the undergraduate period. Therefore, they may be not entirely safe in their work.

Competency is influenced by learner's proficiency, learning capacity, number practice opportunities in the clerkship and the interest to perform a skill.25 26 The skill ‘Episiotomy and repair’ is frequently required in rural practice. However, 39% of survey respondents practiced it three times and 8% only once during their internship. These figures seem inappropriate to safely manage this obstetrical problem.

Some studies attribute the lack of opportunities to practice clinical skills during the internship due to factors such as: the increasing number of students posted in training hospitals, without a proportionate increase in the practice opportunities18 ;difficulty in training during internships; 17 27 and inadequate and inappropriate supervision, feedback and assessment.22 These result in an inconsistent level of student exposure to the skills that they need to competently perform as practicing medical doctors.15

Family medicine residency programmes have been developed tiers of preparation for maternity care.28 In Ecuador the recent graduates may have to face the three tiers proposed depending on the site assigned. The questions arise as Bridge proposes: (1) what do we want the new graduate to do? And, (2) how we want them to act in real-life situations?7

Improvements in the training programmes are required. Beyond faculty development more emphasis should be given to those obstetrical skills important for practice in rural areas. Skills Labs should be incorporated as a new learning strategy for their acquisition and practice.

Methodological considerations

This study is limited to rural doctors from one province in Southern Ecuador. The inherent bias of participant's selection and the high-response rate due to a pressure to fill the survey are acknowledged. Possible effects of memory recall of the clerkships experience in the obstetrical skills should be taken into account. In the other side rural doctors are facing the real needs of its population.

The study only accounted for subjective opinions of survey respondents, and the actual dexterity of performing the skills was not assessed. At the participating Universities, we have introduced skill lab training focusing on the perinatal skills. Therefore, future research on this topic can measure knowledge, skills and behaviours with objective structured clinical examinations prior and after the internship.

The present study only investigates the perceptions of the important skills in rural areas and clerkship experiences. Other aspects such as the way that perinatal care is taught in the medical schools remains not investigated. Despite recent reforms in higher education in Ecuador, the availability of well-trained faculty at medical schools remains unstable and there are few mechanisms currently in place to ensure quality and supply of teaching staff.6

We are showing evidence among recent graduated medical doctors doing their rural service who are not in training but have an important duty in the Ecuadorian health system. The recent graduate medical doctor or basic doctor does not have the training as general practitioner or family doctor. We used some literature in postgraduate training to face the limitations of these rural doctors.29

We did not analyse internship experiences in function of the University the students graduated from. In Ecuador, the use of a standard medical curriculum is problematic. In 2008 a constitutional mandate began the evaluation of the higher education system. Those universities that did not improve and did not meet the minimum quality standards were closed in 2012. The governmental control agency continues monitoring and evaluating colleges and careers to improve higher education in Ecuador. The last assessment conducted was in 2013.30

Implications for Ecuadorian medical training

Although the effectiveness of self-assessment on identification of learner needs and learner activity may have limitations, the gap between the perceptions of skills needed and actual practice has been demonstrated. Extending the study using other sources of feedback and assessment could provide a more complete appraisal of competence in obstetrical skills required for the rural year.31

A collaborative approach between the faculty, the Ministry of Health and rural doctors is proposed with the objective to improve the undergraduate curriculum and better meet the needs of the recent graduates entering into rural service.16 21 32 One option would be to offer more exposure to rural communities in the undergraduate curriculum.33––35 This can be supplemented with virtual monitoring and materials for online or continuing medical education. The implementation of skills laboratory training can better prepare students for clerkships.36

These results also raise several questions regarding current training for the recent graduates and the improvement of rural medical care: Should all basic doctors be trained to perform a core set of obstetrical procedures, or should students be trained with a focus towards the location of the rural year? What skills are then really needed? Taking into account that after the rural year these doctors choose their specialty, not necessarily related to obstetrics, is it necessary to teach those skills? If in Ecuador we use recent graduates to cover the service: should we prepare the basic doctors in advance procedures in obstetrics and emergencies? Or, do we improve the rural placements for specialists in family medicine with these training? From the public health perspective, future work is needed to study the training of nurses and midwives and the collaboration with the rural doctors.

Conclusion

In this study we have noted the gap between the medical needs of populations in rural areas and training provided during the clerkship experiences of physicians during their rural service year.

The universities have to check their curriculum to meet the needs of rural doctors and improve their skills.

It is imperative to ensure that rural doctors are appropriately trained and skilled in the performance of routine obstetrical duties. This will help to decrease perinatal morbidity and mortality in rural Ecuador.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Contributors: GSdH conceptualised the study, developed the proposal and wrote the report. RR participated in the design of the study, coordinated the conduct of the project and assisted in writing the report. VV provided substantial contributions to analysis and interpretation of data and assisted in writing the report. PVR provided substantial contributions to conception and design of the proposal and revising the article critically for important intellectual content and final approval of the version to be published. KH participated in the design of the study, coordinated the conduct of the project and revising the article critically for important intellectual content and final approval of the version to be published.

Funding: The work is supported by VLIR-UOS Project ZEIN2010PR377 ‘Improving and strengthening quality for Family Medicine training in Ecuador, using capacity building and distant learning’ developed between University of Antwerp, Belgium and Universidad Técnica Particular de Loja, Ecuador.

Competing interests: None.

Ethics approval: The Universidad Técnica Particular de Loja and the research committee of Pontificia Universidad Católica de Ecuador approved the study protocol and the questionnaire.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

References

- 1.Frehywot S, Mullan F, Payne PW, et al. Compulsory service programmes for recruiting health workers in remote and rural areas: do they work? Bull World Health Organ 2010;88:364–70 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cavender A, Albán M. Compulsory medical service in Ecuador: the physician's perspective. Soc Sci Med 1998;47:1937–46 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Ley Orgánica de Salud. Registro Oficial 2006;Nro 423.

- 4. Decreto Supremo No 44. Ecuador: 1970.

- 5.Health systems profile . Ecuador. Monitoring and analysis health systems change/reform.3rd edn Washington, DC: USAID, Pan American Health Organization, 2008. http://www2.paho.org/hq/dmdocuments/2010/Health_System_Profile-Ecuador_2008.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 6.Joffre CP, Delgado B, Kosik RO, et al. Medical education in Ecuador. Med Teach 2013;35:979–84 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Borrell RM. La educación médica en América Latina: debates centrales sobre los paradigmas científicos y epistemológicos. In: Proceso de transformación Curricular: otro paradigma es posible. UNR Editora, Ed. Rosario, Argentina: Universidad Nacional de Rosario, 2005:1–32 [Google Scholar]

- 8.Universidad Técnica Particular de Loja. Pensum Carrera de Medicina. 2010. http://www.utpl.edu.ec/academia/pregrado/area-biologica

- 9.Pontificia Universidad Católica del Ecuador. Malla Curricular de la carrera de Medicina. 2008. http://www.puce.edu.ec/documentos/mallas-curriculares/vigentes/PUCE-MED-Medicina.pdf

- 10.Sanders CW, Edwards JC, Burdenski TK. A survey of basic technical skills of medical students. Acad Med 2004;79:873–5 http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/15326014 (accessed 26 Apr 2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ministerio de Salud Pública. Año de Salud Rural. 2013. http://www.salud.gob.ec/ano-de-salud-rural/

- 12.Instituto Nacional de Estadísticas y Censos. Indicadores básicos de salud. Ecuador 2009. Quito: 2009. http://new.paho.org/ecu/index.php

- 13.Instituto Nacional de Estadísticas y Censos. Indicadores básicos de salud. Ecuador 2011. Quito: 2011

- 14.Clack GB. Medical graduates evaluate the effectiveness of their education. Med Educ 1994;28:418–31 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Remmen R, Denekens J, Scherpbier A, et al. An evaluation study of the didactic quality of clerkships. Med Educ 2000;34:460–4 http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/10792687 (accessed 3 Oct 2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wenrich M, Jackson MB, Scherpbier AJ, et al. Ready or not? Expectations of faculty and medical students for clinical skills preparation for clerkships. Med Educ Online 2010;15:1–8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Remmen R, Derese A, Scherpbier A, et al. Can medical schools rely on clerkships to train students in basic clinical skills? Med Educ 1999;33:600–5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lai NM, Sivalingam N, Ramesh JC. Medical students in their final six months of training: progress in self-perceived clinical competence, and relationship between experience and confidence in practical skills. Singapore Med J 2007;48:1018–27 http://smj.sma.org.sg/4811/4811a7.pdf [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lyss-Lerman P, Teherani A, Aagaard E, et al. What training is needed in the fourth year of medical school? Views of residency program directors. Acad Med 2009;84:823–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Galli A, de Gregorio MJ. Competencias adquiridas en la carrera de Medicina: Comparación entre egresados de dos universidades, una pública y otra privada. Educación Médica 2006;9:21–6 [Google Scholar]

- 21.Moercke AM, Eika B. What are the clinical skills levels of newly graduated physicians? Self-assessment study of an intended curriculum identified by a Delphi process. Med Educ 2002;36:472–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Daelmans HEM, Hoogenboom RJI, Donker AJM, et al. Effectiveness of clinical rotations as a learning environment for achieving competences. Med Teach 2004;26:305–12 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ireland J, Bryers H, van Teijlingen E, et al. Competencies and skills for remote and rural maternity care: a review of the literature. J Adv Nurs 2007;58:105–15 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Van der Vleuten CPM, Schuwirth LWT, Scheele F, et al. The assessment of professional competence: building blocks for theory development. Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol 2010;24:703–19 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kelly BF, Sicilia JM, Forman S, et al. Advanced procedural training in family medicine: a group consensus statement. Fam Med 2009;41:398–404 http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/19492186 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sicaja M, Romić D, Prka Z. Medical students’ clinical skills do not match their teachers’ expectations: survey at Zagreb University School of Medicine, Croatia. Croat Med J 2006;47:169–75 http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?artid=2080370&tool=pmcentrez&rendertype=abstract [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.De Villiers MR, De Villiers PJT. The knowledge and skills gap of medical practitioners delivering district hospital services in the Western Cape, South Africa. S Afr Fam Pract 2006;48:2–5 [Google Scholar]

- 28.Coonrod RA, Kelly BF, Ellert W, et al. Tiered maternity care training in family medicine. Fam Med 2011;43:631–7http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/22002774 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rodney WM, Martinez C, Collins M, et al. OB fellowship outcomes 1992–2010: where do they go, who stops delivering, and why? Fam Med 2010;42:712–16 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Consejo Nacional de Evaluación y Acreditación de Educación Superior del Ecuador. Mandato 14. Modelo de evaluación de desempeño institucional de las instituciones de educación superior. 2009. http://www.ceaaces.gob.ec/images/stories/documentacion/mandato_14/informe_2009/2_modelo_evaluacion/Descripción_Modelo_Final.pdf

- 31.Colthart I, Bagnall G, Evans A, et al. The effectiveness of self-assessment on the identification of learner needs, learner activity, and impact on clinical practice: BEME Guide no. 10. Med Teach 2008;30:124–45 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Peeraer G, De Winter BY, Muijtjens AMM, et al. Evaluating the effectiveness of curriculum change. Is there a difference between graduating student outcomes from two different curricula? Med Teach 2009;31:e64–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zink T, Halaas GW, Finstad D, et al. The rural physician associate program: the value of immersion learning for third-year medical students. J Rural Health 2008;24:353–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Young L, Rego P, Peterson R. Clinical location and student learning: outcomes from the LCAP program in Queensland, Australia. Teach Learn Med 2008;20:261–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Worley P, Strasser R, Prideaux D. Can medical students learn specialist disciplines based in rural practice: lessons from students'self reported experience and competence. Rural Remote Health 2004;4:338 http://www.rrh.org.au/publishedarticles/article_print_338.pdf [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Remmen R, Scherpbier A, van der Vleuten C, et al. Effectiveness of basic clinical skills training programmes: a cross-sectional comparison of four medical schools. Med Educ 2001;35:121–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.