Abstract

Objectives

The Sight Loss and Vision Priority Setting Partnership aimed to identify research priorities relating to sight loss and vision through consultation with patients, carers and clinicians. These priorities can be used to inform funding bodies’ decisions and enhance the case for additional research funding.

Design

Prospective survey with support from the James Lind Alliance.

Setting

UK-wide National Health Service (NHS) and non-NHS.

Participants

Patients, carers and eye health professionals. Academic researchers were excluded solely from the prioritisation process. The survey was disseminated by patient groups, professional bodies, at conferences and through the media, and was available for completion online, by phone, by post and by alternative formats (Braille and audio).

Outcome measure

People were asked to submit the questions about prevention, diagnosis and treatment of sight loss and eye conditions that they most wanted to see answered by research. Returned survey questions were reviewed by a data assessment group. Priorities were established across eye disease categories at final workshops.

Results

2220 people responded generating 4461 submissions. Sixty-five per cent of respondents had sight loss and/or an eye condition. Following initial data analysis, 686 submissions remained which were circulated for interim prioritisation (excluding cataract and ocular cancer questions) to 446 patients/carers and 218 professionals. The remaining 346 questions were discussed at final prioritisation workshops to reach agreement of top questions per category.

Conclusions

The exercise engaged a diverse community of stakeholders generating a wide range of conditions and research questions. Top priority questions were established across 12 eye disease categories.

Keywords: Sight loss, Vision, Research, Priorities, Partnership, James Lind Alliance

Strengths and limitations of this study.

Wide ranging and comprehensive coverage.

Substantial response.

The hardest to reach and those with the least opportunity to be heard may indeed have not been heard.

Any such groups now feeling excluded should have an opportunity to redress this.

Introduction

In the UK, it is estimated that almost two million people are affected by sight loss and this number is expected to double by 2050.1 Currently 50% of sight loss in the UK is avoidable, but there are also many unavoidable sight loss conditions. Whether it is to address childhood eye conditions or those affecting adults, research is needed to inform us about prevention, to develop new techniques for early diagnosis, and to develop new and more effective treatments for many eye conditions.

The Sight Loss and Vision Priority Setting Partnership (SLV-PSP) was developed from earlier work by the Eye Research Group (ERG) of VISION 2020 UK whose mission is the elimination of avoidable sight loss and the amelioration of the effects of sight loss when it cannot be avoided.2 The UK Vision Strategy sets out ways of addressing avoidable sight loss in the UK. There is much that can be done to improve the nation's eye health, and to eliminate avoidable sight loss. There are however gaps in the evidence base regarding eye health interventions and the best way to deliver services. Research is needed to support the UK Vision Strategy. In key areas, research is urgently required to enable the Vision Strategy to be implemented in an evidence-based way that ensures efficient and effective development.

Despite on-going research in the UK and other countries, there are still many questions about the prevention, diagnosis and treatment of sight loss and eye conditions that remain unanswered. Given that resources for research are limited, it is important for research funders to understand how patients, carers and eye health professionals prioritise these unanswered questions so that future research can be consolidated and targeted accordingly.3

The purpose of this project was to undertake a comprehensive, UK-wide, survey of patients, carers and clinicians to identify research questions and priorities to inform decisions of funding bodies and enhance the case for additional research funding.

The priority setting process has been well established by the James Lind Alliance (JLA) (http://www.lindalliance.org/) which has supported partnerships on a range of topics since 2004. This partnership initiated by Fight for Sight, the UK's leading eye research charity was established with support, financial and in kind, from the College of Optometrists, the Royal College of Ophthalmologists, the NIHR Moorfields Biomedical Research Centre, the RNIB, UK Vision Strategy and the Cochrane Eyes and Vision Group. A representative from the JLA convened meetings of the steering committee and provided independent chairmanship for this and the priority setting workshops. Their extensive experience in this process ensured no single voice exerted undue influence over the prioritisation process and that the views of patients, their carers and clinicians were paramount. The views of researchers with no clinical involvement with patients and views of commercial organisations were not included in the prioritisation.

Methods and materials

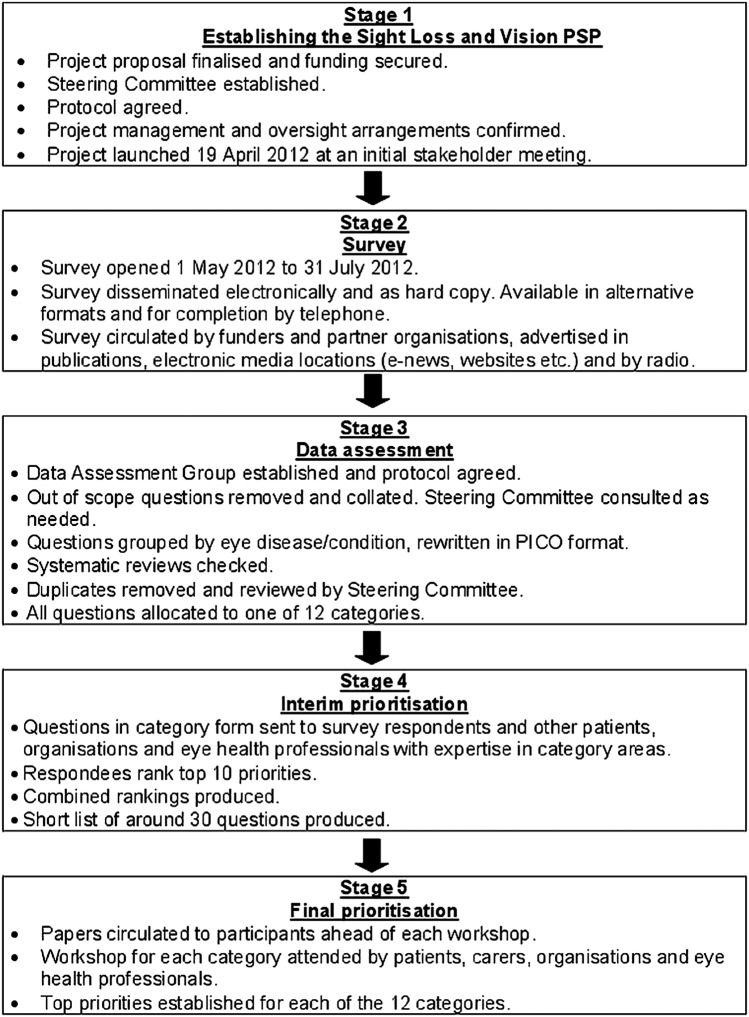

The detailed methods for this prioritisation process have been described in detail elsewhere.4 In brief, the process comprised five stages (figure 1). Our study did not require ethical approval or consent from participants. JLA priority setting partnerships do not require ethical approval. Dissemination of the survey was via open communications through professional bodies, charities and related organisations. The survey was not undertaken through Higher Education Institutes or through National Health Service (NHS) organisations and does not recruit NHS patients. The survey contained clear information on the aims of the priority setting partnership, how the process works and how data will be used. In addition, submission of questions was anonymised. For the workshops in which priorities were discussed and agreed, participants choose to voluntarily attend and consent was not required for this. We followed the ethical guidance for participation, information and evaluation from the JLA guidebook (http://www.jlaguidebook.org/jla-guidebook.asp?val=56).

Figure 1.

Flow chart showing the steps of the process from stage 1 when establishing the Priority Setting Partnership (PSP) through to stage 5 at the final prioritisation (PICO, Population, Intervention, Comparison, Outcome).

Establishing the SLV-PSP

A steering committee and data assessment group comprising the authors of this article oversaw the process. Each member was responsible for contributing to and managing a part of the process and was selected for their expertise and association with eye research. The steering committee also included patient representatives and eye health professionals. In April 2012, an initial stakeholder meeting was held to engage the groups and organisations with member bases and community influence. This was to ensure that the initial survey would be disseminated and completed by as many patients, relatives, carers and eye health professionals as possible in the UK.

Main survey

The SLV-PSP survey was launched on 1 May 2012 and was open until 31 July 2012. The aim of the survey was to identify patients’, carers’ and eye health professionals’ unanswered questions about sight loss and eye conditions. The survey's primary question was “What question(s) about the prevention, diagnosis and treatment of sight loss and eye conditions would you like to see answered by research?”

Data analysis

Following closure of the survey, all submissions were examined. Out-of-scope submissions were removed including those not related to the topic and uncertainties better suited to social research. In-scope uncertainties were allocated into disease-specific groups and reworded in PICO format (Population, Intervention, Comparison, Outcome). Searches were then undertaken to ascertain whether each uncertainty could be answered by an up-to-date systematic review. All unanswered uncertainties were then allocated to 1 of 12 eye disease categories, with duplicates removed and similar questions combined. Checks were also made to identify any on-going trials, which might address the uncertainty. The 12 categories were formed following discussions by the steering group on the most logical and pragmatic way to organise the data within the time and resources available.

Interim prioritisation

In order to start reducing the number of uncertainties, an interim prioritisation exercise was conducted over email and by post. Patients, carers and eye health professionals were invited to examine the long lists and then choose and rank 10 of the uncertainties.

Final prioritisation

The remaining uncertainties were ranked by patients, carers, relatives, organisation representatives and eye health professionals in 1-day workshops facilitated by the JLA, using Nominal Group Technique—a mix of discussion and ranking. For each category, the top 10/11 questions were agreed.

Results

Main survey

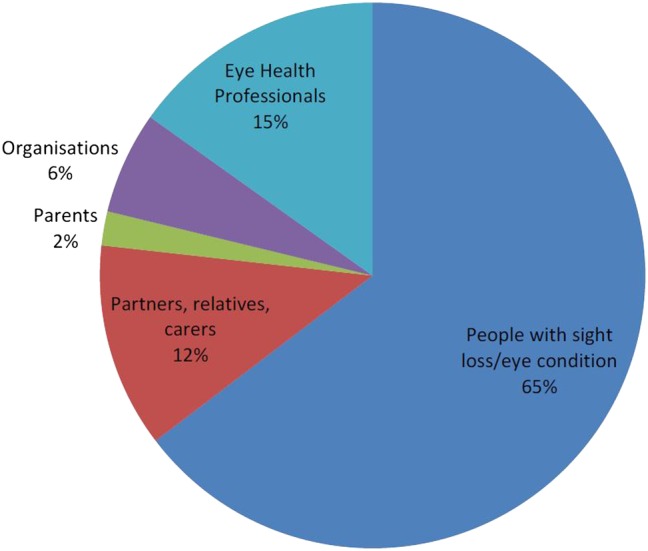

In response to the survey, 2220 people generated 4461 submissions. Of these respondents, 17% identified themselves as healthcare professionals including primarily ophthalmologists, optometrists, orthoptists, ophthalmic nurses, opticians and people working in social care and rehabilitation services (figure 2). Over 60% were people with sight loss or an eye condition. The average age of survey participants was 65.7 years old (range 16 months (proxy completion of survey by adult carer) to 105 years). Just under two-thirds (62%) of the respondents were female. The geographical split was England 89%, Scotland 6%, Wales 4% and Northern Ireland 1%.

Figure 2.

Background of respondents showing that questions were largely received from people who have sight loss or an eye condition, but also including eye health professions, organisations, parents, family and carers.

Data analysis

Following data analysis to remove duplicate/answered/out of scope uncertainties, 686 uncertainties remained. These were divided into 12 eye disease categories. Table 1 shows each category with the initial number of submissions received after the survey responses were submitted, the number of uncertainties sent to interim prioritisation, the number of participants at interim prioritisation and the number of uncertainties considered at the final prioritisation workshops.

Table 1.

Categories of eye condition

| Initial number of survey questions | Number of questions at interim prioritisation | Number of participants at interim prioritisation | Number of questions at final prioritisation | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age-related macular degeneration | 763 | 43 | 101 PPI 25 Professionals |

29 |

| Cataract | 191 | 27 | Not required | 27 |

| Childhood-onset disorders | 125 | 69 | 12 PPI 20 Professionals |

30 |

| Corneal and external diseases | 292 | 93 | 25 PPI 38 Professionals |

30 |

| Glaucoma | 1235 | 78 | 182 PPI 25 Professionals |

30 |

| Inherited retinal diseases | 280 | 63 | 27 PPI 25 Professionals |

30 |

| Neuro-ophthalmology | 125 | 43 | 15 PPI 21 Professionals |

30 |

| Ocular cancer | 26 | 19 | Not required | 19 |

| Ocular inflammatory diseases | 472 | 66 | 27 PPI 21 Professionals |

30 |

| Refractive error and ocular motility | 188 | 70 | 21 PPI 23 Professionals |

31 |

| Retinal vascular diseases | 205 | 56 | 15 PPI 12 Professionals |

30 |

| Vitreoretinal and ocular trauma | 265 | 59 | 21 PPI 8 Professionals |

30 |

Professionals: Inclusive of eye health professions.

Patient and Public Involvement (PPI): Inclusive of patients, carers, relatives, organisation representatives.

Interim prioritisation

Respondents from the initial survey, organisations and eye healthcare professionals with expertise in the eye diseases in 10 categories were contacted to provide interim priority rankings. The smaller number of questions asked in the categories relating to cataract and ocular cancer meant that an interim prioritisation exercise was not required for either category. A large response was received for the interim exercise, with input from 446 patients, carers and relatives plus 218 eye health professionals. Uncertainties accumulated scores based on rank and frequency, resulting in short lists of around 30 uncertainties per category, which were taken to final workshops.

Final prioritisation

In April and May 2013, 12 final prioritisation workshops were held: one for each eye disease category. Balanced numbers of patients/carers/relatives and eye health professionals participated. In total, 155 participants attended across all 12 workshops: 78 patients and 77 clinicians (table 2). The topics debated at each workshop comprised between 19 and 31 questions per category. Overall, 153 questions about sight loss and vision were considered resulting in lists of 10/11 priorities for each of the 12 categories (table 3). The questions addressed the broad topics of aetiology, prevention, identification and interventions with the number 1 questions as follows:

- Age-related macular degeneration

- Can a treatment to stop dry AMD progressing and/or developing into the wet form be devised?

- Cataract

- How can cataracts be prevented from developing?

- Childhood-onset disorders

- How can cerebral visual impairment be identified, prevented and treated in children?

- Corneal and external diseases

- Can new therapies such as gene or stem cell treatments be developed for corneal diseases?

- Glaucoma

- What are the most effective treatments for glaucoma and how can treatment be improved?

- Inherited retinal diseases

- Can a treatment to slow down progression or reverse sight loss in inherited retinal diseases be developed?

- Neuro-ophthalmology

- What is the underlying cause of optic nerve damage in optic neuropathies, such as anterior ischaemic optic neuropathy, Leber's hereditary optic neuropathy, optic neuritis and other optic neuropathies?

- Ocular cancer

- What can be done to help ocular cancer sufferers?

- Ocular inflammatory diseases

- What are the most effective treatments for ocular and orbital inflammatory diseases?

- Refractive error and ocular motility

- What factors influence the development of refractive error (myopia, astigmatism, presbyopia and long-sightedness)?

- Retinal vascular diseases

- What are the best methods to prevent retinopathy of prematurity?

- Vitreoretinal and ocular trauma

- How can surgical techniques be improved to save sight for eyes damaged by injury?

Table 2.

Final workshop participants

| Category | Total number of workshop participants | Number of patients, relatives, carers, patient groups and organisations | Number of eye health professionals |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age-related macular degeneration | 17 | 9 | 8 |

| Cataract | 11 | 5 | 6 |

| Childhood-onset disorders | 16 | 7 | 9 |

| Corneal and external diseases | 12 | 5 | 7 |

| Glaucoma | 17 | 9 | 8 |

| Inherited retinal diseases | 19 | 11 | 8 |

| Neuro-ophthalmology | 10 | 6 | 4 |

| Ocular cancer | 10 | 6 | 4 |

| Ocular inflammatory diseases | 10 | 5 | 5 |

| Refractive error and ocular motility | 12 | 5 | 7 |

| Retinal vascular diseases | 11 | 3 | 8 |

| Vitreoretinal and ocular trauma | 10 | 7 | 3 |

| Total | 155 | 78 | 77 |

Table 3.

Top 10 lists per category

| Age-related macular degeneration | Cataract | Childhood-onset disorders | Corneal and external diseases | Glaucoma | Inherited retinal diseases | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Can a treatment to stop dry AMD progressing and/or developing into the wet form be devised? | How can cataracts be prevented from developing? | How can cerebral visual impairment be identified, prevented and treated in children? | Can new therapies such as gene or stem cell treatments be developed for corneal diseases? | What are the most effective treatments for glaucoma and how can treatment be improved? | Can a treatment to slow down progression or reverse sight loss in inherited retinal diseases be developed? |

| 2 | What is the cause of AMD? | Can the return of cloudy or blurred vision after cataract surgery known as posterior capsule opacity (PCO) or secondary cataract be prevented? | How can treatment for visual pathway damage associated with preterm birth be developed? | What is the most effective management for dry eye and can new strategies be developed? | How can loss of vision be restored for people with glaucoma? | How can sight loss be prevented in an individual with inherited retinal disease? |

| 3 | How can AMD be prevented? | How can cataract progression be slowed down? | How do we improve screening and surveillance from the antenatal period through to childhood to ensure early diagnosis of impaired vision and eye conditions? | Can treatments to save eye sight from microbial keratitis be improved? | How can glaucoma be stopped from progressing? | Is a genetic (molecular) diagnosis possible for all inherited retinal diseases? |

| 4 | Are there ways of restoring sight loss for people with AMD? | What alternatives to treat cataracts other than cataract surgery are being developed? | Can the treatment of amblyopia be improved to produce better short-term and long-term outcomes than are possible with current treatments? | How can the rejection of corneal transplants be prevented? | What can be done to improve early diagnosis of sight-threatening glaucoma? | What factors affect the progression of sight loss in inherited retinal diseases? |

| 5 | Can the development of AMD be predicted? | What is the cause of cataract? | How can cataract be prevented in children? | Can the outcomes of corneal transplantation be improved? | What causes glaucoma? | What causes sight loss in inherited retinal diseases? |

| 6 | What is the most effective way to detect and monitor the progression of early AMD? | How can cataract surgery outcomes be improved? | What are the causes of coloboma and microphthalmia/anophthalmia and how can they be prevented? | What causes keratoconus to progress and can progression be prevented? | What is the most effective way of monitoring the progression of glaucoma? | What is the most effective way to support patients with inherited retinal disease? |

| 7 | What factors influence the progression of AMD? | How safe and effective is laser assisted cataract surgery? | Can vision be corrected in later life for people with amblyopia? | Can non-surgical therapy be developed for Fuchs’ corneal dystrophy? | How can glaucoma patients with a higher risk to progress rapidly be detected? | Can the diagnosis of inherited retinal diseases be refined so that individuals can be given a clearer idea about their specific condition and how it is likely to progress? |

| 8 | Can a non-invasive therapy be developed for wet AMD? | Should accommodative lenses be developed for cataract surgery? | How can retinoblastoma be identified, prevented and treated in children? | Can corneal infections be prevented in high-risk individuals such as contact lens wearers? | Why is glaucoma more aggressive in people of certain ethnic groups, such as those of West African origin? | What is the relationship between sight loss and mental health for people with inherited retinal diseases? |

| 9 | Can dietary factors, nutritional supplements, complementary therapies or lifestyle changes prevent or slow the progression of AMD? | What is the best measure of visual disability due to cataract? | Can better treatments for glaucoma in children be developed? | What is the cause of keratoconus and can it be prevented? | How can glaucoma be prevented? | Would having a treatment for an inherited retinal disease preclude a patient from having another treatment? |

| 10 | What are the best enablement strategies for people with AMD? | Can retinal detachment be prevented after cataract surgery? | Can a treatment be developed to improve vision for people with albinism? | What is the most effective management of ocular complications associated with Stevens Johnson Syndrome? | Is there a link between treatment adherence and glaucoma progression and how can adherence be improved? | With regard to inherited retinal diseases what is the role of prenatal and preimplantation diagnosis in helping parents make informed choices? |

| 11 | What are the outcomes for cataract surgery among people with different levels of cognitive impairment (all causes excluding dementia, stroke, neurological conditions, head injuries)? | Can severe ocular surface disease in children, such as blepharokeratoconjunctivitis and vernal keratoconjunctivitis be managed better? |

| Neuro-ophthalmology | Ocular cancer | Ocular inflammatory diseases | Refractive error and ocular motility | Retinal vascular diseases | Vitreoretinal and ocular trauma | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | What is the underlying cause of optic nerve damage in optic neuropathies, such as anterior ischaemic optic neuropathy, Leber's hereditary optic neuropathy, optic neuritis and other optic neuropathies? | What can be done to help ocular cancer sufferers? | What are the most effective treatments for ocular and orbital inflammatory diseases? | What factors influence the development of refractive error (myopia, astigmatism, presbyopia and long-sightedness)? | What are the best methods to prevent retinopathy of prematurity? | How can surgical techniques be improved to save sight for eyes damaged by injury? |

| 2 | What are the most effective treatments and rehabilitation for optic neuropathies, eg, Leber's hereditary optic neuropathy and anterior ischaemic optic neuropathy? | Can gene-based targeted therapies for ocular cancers be developed? | What causes thyroid eye disease? | What is the cause of both congenital and acquired nystagmus? | How can sight loss from diabetic retinal changes be prevented and reduced? | How can the risk of losing sight for people with retinal detachment be reduced? |

| 3 | Can vision loss due to optic nerve diseases such as giant cell arteritis, Leber's hereditary optic neuropathy, optic neuritis and optic atrophy, be restored, eg, through gene therapy and stem cell treatment? | How can immunotherapy be used to fight metastatic ocular melanoma? | Can the severity of ocular and orbital inflammatory disease in an individual be predicted? | How can the development of binocular vision in young children with squint and amblyopia be promoted, and would the same approach work in older individuals without inducing intractable diplopia? | What are the predictive factors for the progression to sight threatening diabetic eye disease? | How can better interventions be developed that are effective in treating vitreous opacities/eye floaters? |

| 4 | What rehabilitation or treatment methods are most effective for vision loss following brain damage due to stroke, brain injury, cerebral vision impairment, tumours and dementias? | What are the most effective detection and screening methods for follow-up to detect metastasis of ocular melanoma? | Is it possible to prevent further occurrences of retinal damage caused by toxoplasmosis? | Would correction of refractive error have a positive impact on early life learning and development? | Is there a way to improve screening of premature babies for retinopathy of prematurity? | What causes retinal detachment and can it be prevented? |

| 5 | What is the most effective way to assess vision in patients with neurological visual impairment ie, stroke, dementia and cerebral/cortical visual impairment? | How can follow-up for ocular complications be managed in patients with ocular melanoma? | What causes birdshot retinopathy? | Does early diagnosis of refractive error improve long-term prognosis and promote faster, more effective treatment? | Can an effective long lasting treatment for diabetic macular oedema, both ischaemic and non-ischaemic, be developed? | Can more effective diagnostic tools be developed for assessing the vitreous and eye floaters? |

| 6 | Can the early stages of optic neuropathy be detected? | What is the best management of metastatic choroidal melanoma? | Why does disease burn out in patients with ocular and orbital inflammatory diseases? | What is the effect of congenital nystagmus on visual and emotional development? | Can a retinal vein occlusion be predicted and prevented? | Can a functioning prosthetic eye be developed to replace an eye damaged by injury? |

| 7 | How can optic neuropathies be prevented, for example anterior ischaemic optic neuropathy, Leber's hereditary optic neuropathy, optic neuritis and other optic neuropathies? | What activates choroidal melanoma metastasis in the liver after the primary melanoma has been treated? | Can early detection methods be developed for ocular and orbital inflammatory diseases? | What is the most effective treatment for exotropia and when should it be delivered? | Can new non-invasive treatments be developed to slow down the progression of diabetic retinopathy? | How can epiretinal membrane/fibrosis be prevented or treated? |

| 8 | Can treatments be developed for visual field and ocular motility manifestations following stroke? | Can adjuvant therapies be developed to treat ocular melanoma? | What medications best prevent the development of eye disease in Behcets? | How can the functional effects of surgical treatment for squint best be assessed? | What are the barriers that prevent diabetic patients having regular eye checks? | Can stem cells be used to regrow an eye or part of an eye? |

| 9 | How can electronic devices improve or restore vision for people with optic neuropathies? | What are the causes of ocular cancer and how can they be prevented? | What causes scleritis? | Could the accurate testing of refractive error be made less dependent on a subjective response ie, the person's own response? | What rehabilitation programmes are best for the management of distorted vision from retinal diseases? | What causes posterior vitreous detachment/vitreous syneresis? |

| 10 | Can an alternative or new treatment be developed that will treat the sight loss caused by giant cell arteritis? | What is the most effective treatment for primary ocular melanoma? | Can diet or lifestyle changes prevent uveitis from developing? | How can myopia be prevented? | What is the efficacy and safety of anti-VEGF agents in the treatment of retinopathy of prematurity? | Are there methods to prevent and improve the treatment of macular holes? |

AMD, age-related macular degeneration; VEGF, vascular endothelial growth factor.

Discussion

About 50% of sight loss in the UK is currently avoidable.1 Recognising this and the UK's pre-eminent position in eye research, the Vision 2020UK ERG considered that any UK Research Agenda must look at addressing unavoidable sight loss for it to be credible. The challenge was to produce a coherently constructed and constituted prioritised research agenda whose methods were clear and for which there had been inclusive and widespread consultation, where everyone with an interest had been offered the opportunity to contribute and be heard. As a result of this priority setting partnership, we have established top 10 lists of research questions for a range of eye conditions.

There are a number of strengths to this study. The SLV-PSP is unique because it sought the combined views of patients, carers and eye health professionals to identify uncertainties about the prevention, diagnosis and treatment of sight loss and eye conditions and prioritise them for research to address.5 It is rare that those with direct experience of conditions are able to influence the research agenda.3 5 6 The views of patients, carers and professionals were given equal merit. All submitted questions were evaluated independently and equally. Duplicate questions and out-of-scope questions were removed. We did not encounter particular misunderstandings between laypersons and professionals or insufficient knowledge of the public. Open discussions occurred during the face-to-face workshops with good communication and facilitation to encourage respectful listening in accordance with JLA guidelines. Questions could only be pooled if this was agreed by patients, carers and professionals. Where there was no agreement, the questions remained separate. Thus, any differing perspectives of priorities between participants were acknowledged. We did not aim to compare and contrast questions from patients, carers and professionals but to represent and act on all.

This SLV-PSP provided an extensive set of unanswered questions prioritised by patients, carers and eye health professionals across 12 categories of eye conditions. These questions addressed a broad range of eye conditions and considered issues of aetiology, prevention, screening, assessment and management. Importantly, the public were as likely to propose questions in relation to aetiology, assessment and management just as professionals were as likely to raise questions regarding impact of sight loss.

In addition to the strengths of our study, we identified a number of limitations. We were unable to calculate a response rate for the survey because of the nature of its design and implementation. We did not request the views of ‘pure’ researchers (ie, scientists with no current clinical practice) as these individuals are intentionally excluded from the priority setting process by the JLA. This step is a key feature of the JLA methodology in which the remit is to provide an opportunity for patients, carers and clinicians to influence the research agenda. We acknowledge this is a different approach but do not consider their exclusion as a flaw in this process as we include clinical researchers who did take part alongside clinicians and the public.

These questions may now be used to encourage researchers to investigate what is most important to these groups. We do not know how our research questions compare with the prioritisation of research areas by scientists, government agencies or other organisation research funders. We are unaware of any systematic data collating such data.

Various organisations in the sector have set out priorities for eye health and eye research in the past, for example Vision2020UK.7 In addition, organisations representing the interests of patients/carers and eye health professionals took part in the process, both in promoting the survey and being directly involved in priority setting. Future work to review the SLV-PSP projects priorities with these organisations could be helpful in developing an understanding of how these new, patient and clinician led priorities can inform the sectors approach to commissioning research and focusing resources. Organisations in the sector are already working to review their organisational priorities with the SLV priorities, and have begun to invite researchers seeking funding to consider how their proposed research relates to the SLV priorities.

Similar to other PSP processes, we have provided information on our research priorities openly to national funding organisations and it is envisaged that research funders will be able to use the list to inform commissioned calls for research and identify which research applications to response mode funding opportunities can answer questions that these groups have agreed are a priority. Furthermore, any questions or uncertainties not prioritised in this process were submitted to and are currently available in the UK Database of Uncertainties about the Effects of Treatments (UK DUETs). Thus, individuals looking for uncertainties for their research can access such information directly from the UK DUETs. This sharing of information contributes to the quality assurance process of avoiding waste in research.

The SLV-PSP will also help to increase awareness of why research on sight loss and vision is necessary and important. It will be used to campaign for the major funders to invest in sight loss and eye conditions, all of which are placing increased emphasis on researchers demonstrating how they have consulted and involved the public and patients in the process of developing their research.

These remain as significant goals. For a sector with around 700 organisations to arrive at any kind of consensus for research priority areas, a process that was genuinely consultative, open and engaging to the individuals whose interests these organisations represent as well as at an organisational level was recognised as being critical. For a prioritisation exercise to be useful to the sector it needs to make sense to funders and statutory bodies, with responsibilities and interests in these areas, and to researchers. It was recognised that a prioritisation of research areas produced by a small group within the sector would not be credible and would never engage the support required for it to achieve the goals listed above.

Conclusions

Following a systematic process of national consultation and widespread survey of patients, carers and clinicians, 2220 individuals generated 4461 questions. Through a process of data analysis, interim prioritisation and final workshops, a top 10 or 11 research questions have been identified for 12 categories of eye conditions. This is the first time, to our knowledge, that an exercise like this has been carried out anywhere in the world for sight loss and vision. Not only is this the most wide ranging and ambitious JLA priority setting partnership, it also engaged a diversity of participants and enabled them to reach consensus together. For the first time, we have a clear idea of what the consumers of eye research—the patients and the people who care for and treat them—believe research money should be spent on. It has provided a focus for research in sight loss and vision and it is intended that these priorities are used to inform funders, researchers, clinicians and the public.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Contributors: All the authors contributed to the conduct of the survey. FR, RW, RC, MA, MB, DC and KC were involved in the drafting of the paper. KB, CBr, CBu, KE, MF, HG, IG, LH, RH, AL, MV, HW and AZ contributed to proofing of the paper.

Funding: This work was supported through funding and/or in-kind support by College of Optometrists, Fight for Sight, James Lind Alliance, NIHR Moorfields BRC, RNIB, Royal College of Ophthalmologists and UK Vision Strategy.

Competing interests: RW is funded by financial support from the UK's Department of Health through the award made by the National Institute for Health Research to Moorfields Eye Hospital NHS Foundation Trust and UCL Institute of Ophthalmology for a Specialist Biomedical Research Centre for Ophthalmology. The views expressed in this presentation are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the Department of Health. The Cochrane Eyes and Vision Group is also funded by the National Institute for Health Research through a grant held at the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: All original data are held by Fight for Sight. Extra data is available from: http://www.library.nhs.uk/duets/SearchResults.aspx?catID=14501. The additional unpublished data includes research questions not included in the final top 10 lists of research priorities.

References

- 1.Access Economics. Future Sight Loss UK 1: The economic impact of partial sight and blindness in the UK adult population, RNIB, 2009

- 2. http://www.vision2020uk.org.uk/ [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chalmers I, Glasziou P. Avoidable waste in the production and reporting of research evidence. Lancet 2009;374:86–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sight Loss and Vision Priority Setting Partnership. Setting priorities for eye research. Final report; 2013. http://www.sightlosspsp.org.uk

- 5.Stewart R, Oliver S. A systematic map of studies of patients’ and clinicians’ research priorities. London: James Lind Alliance, 2008 [Google Scholar]

- 6.Caron-Flinterman J, Broerse JE, Teerling J, et al. Patients prioritiesconcerning health research: the case of asthma and COPD research in the Netherlands. Health Expect 2006;8:253–63 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. UK Vision Strategy 2013–2018. http://www.vision2020uk.org.uk.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.