Abstract

Objective

This study examined the risk factors associated with failure of enhanced recovery protocol after major hepatobiliary and pancreatic (HBP) surgery.

Setting and participants

A retrospective cohort of 194 adult patients undergoing major HBP surgery at a university hospital in Hong Kong was followed up for 30 days. The patients were from a larger cohort study of 736 consecutive adults with preoperative urinary cotinine concentration to examine the association between passive smoking and risk of perioperative respiratory complications and postoperative morbidities.

Outcome measures

The primary outcome was failure of enhanced recovery protocol. This was defined as a composite measure of the following events: intensive care unit (ICU) stay more than 24 h after surgery, unplanned admission to ICU within 30 days after surgery, hospital readmission, reoperation and mortality.

Results

There were 25 failures of enhanced recovery after HBP surgery (12.9%, 95% CI 8.5% to 18.4%). After adjusting for elective ICU admission, smokers (relative risk (RR ) 2.21, 95% CI 1.10 to 4.46), high preoperative alanine transaminase/glutamic-pyruvic transaminase (RR 3.55,95% CI 1.68 to 7.49) and postoperative morbidities (RR 2.69, 95% CI 1.30 to 5.56) were associated with failures of enhanced recovery in the generalised estimating equation risk model. Compared with those managed successfully, failures stayed longer in ICU (median 19 vs 25 h, p<0.001) and in hospital for postoperative care (median 7 vs 13 days, p=0.003).

Conclusions

Smokers and patients having high preoperative alanine transaminase/glutamic-pyruvic transaminase concentration or have a high risk of postoperative morbidities are likely to fail enhanced recovery protocol in HBP surgery programmes.

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This is the first study to identify risk factors associated with the failure of enhanced recovery protocol in major hepatobiliary and pancreatic surgery.

Instead of using length of hospital stay as an end point, failure was defined as a composite measure of slow recovery: length of stay in the intensive care unit (ICU) more than 24 h after surgery, unplanned admission to ICU within 30 days, readmission to the hospital within 30 days after surgery, reoperation for complications and 30-day mortality.

Smokers (defined by self-reported history and adjusted urinary cotinine concentration) and patients having high preoperative alanine transaminase/glutamic-pyruvic transaminase concentration or who have a high risk of postoperative morbidities are likely to fail clinical pathways in fast-track hepatobiliary and pancreatic surgery. Similar results were found in a sensitivity analysis using adjusted urinary cotinine concentrations.

We did not consider the compliance rate of individual components of the early recovery after the hepatobiliary pancreatic surgery programme.

High-risk patients at risk of failing enhanced recovery protocols in major hepatobiliary pancreatic surgery may benefit from additional care to minimise perioperative morbidities and length of stay.

Introduction

Enhanced recovery after major hepatobiliary and pancreatic surgery (ERAHBPS) is a complex intervention that includes many of the following components: patient and family education, no bowel preparation, no preanaesthetic medication, preoperative carbohydrate loading, thromboembolic prophylaxis, antiemetic prophylaxis, epidural analgaesia, intraoperative normothermia, prophylactic antibiotics, no systemic opioids, fluid restriction, no surgical drains, no standard postoperative nasogastric tubes, postoperative nutritional care and early mobilisation.1

Recent systematic reviews1 2 of several observational studies of ERAHBPS programmes suggest that it is safe and feasible. Compared with traditional clinical pathways, fast-track hepatobiliary and pancreatic (HBP) surgery programmes have similar risks of readmission, morbidity and mortality,1–3 and reduced the duration of postoperative length of stay and overall hospital cost.3 However, compliance with core components of enhanced recovery after liver surgery programme varies between high-volume European centres, with a median adoption of 9 (range 7–12) of 22 core elements.4

As with all enhanced recovery after surgery (ERAS) programmes, a small proportion of patients will fail fast-track HBP surgery and require additional intensive care unit (ICU) resources. Although not all fast-track HBP surgical patients are routinely admitted to ICU after their procedure,5 6 ICU care after liver resection was associated with a decreased risk in hospital mortality (OR=0.26, 95% CI 0.10 to 0.71) and a reduction in total hospital costs (13%).7 These results suggest that careful selection of patients for ERAHBPS is crucial for maximising the efficiency of perioperative care pathways.

Fast-track failure risk models after cardiac surgery have been developed8 and externally validated9 to facilitate the planning of perioperative care pathways, but factors associated with failure of enhanced recovery protocol after HBP surgery are unknown. The objectives of this study were to estimate the incidence of and identify the risk factors associated with failure of enhanced recovery protocol after HBP surgery. With such information, we can identify a subgroup of patients at risk of failure to provide additional care to minimise perioperative morbidities and length of stay.

Methods

Study cohort

The patients were from a larger cohort study of 736 consecutive adult patients with preoperative urinary cotinine concentration to examine the association between passive smoking and risk of perioperative respiratory complications and postoperative morbidities.10 All patients gave written informed consent before surgery. Patients undergoing other types of surgery, unable to give written informed consent, having chronic renal failure, younger than 18 years or with urine cotinine samples collected more than 48 h before surgery were excluded.

The types of surgery included were laparoscopic liver resection (non-anatomical wedge resections, or resection of one or two segments), minor open liver resection (fewer than three segments including multiple non-anatomical resections), major open liver resections (three or more segments), liver resection with biliary reconstruction11 12 and pancreatic surgery. Pancreatic surgery included Whipple's procedure, double bypass (hepaticojejunostomy and gastrojejunostomy in unresectable cancer of the head of pancreas) and distal pancreatectomy.

Typical management

The typical clinical care pathway for HBP surgical patients involved the following: admission to surgical ward 1 day before surgery, patient education, no preanaesthetic medication, mechanical prophylaxis for deep vein thrombosis, intraoperative prophylactic antibiotics, normothermia during surgery, ICU or surgical ward for first 24 h after surgery, surgical ward, early mobilisation and hospital discharge (table 1). The use of epidural anaesthesia/analgaesia is not routine because of concerns about postoperative coagulopathy in patients with cirrhosis of liver.13 Patients were given patient-controlled morphine analgesia.

Table 1.

Enhanced recovery elements in liver and pancreatic resectional surgery

| Liver resection | Pancreatic resection | |

|---|---|---|

| Preoperatively | Information given to patient and patient education No premedication |

Information given to patient and patient education No premedication |

| Day 0 | Normothermia during surgery Mechanical prophylaxis for deep vein thrombosis Intraoperative prophylactic antibiotics No nasogastric tube No routine abdominal drain |

Normothermia during surgery Mechanical prophylaxis for deep vein thrombosis Intraoperative prophylactic antibiotics Routine nasogastric and abdominal drain only for Whipple's operation |

| Day 1 | Patient-controlled morphine analgesia Oral fluid Moving patient to chair |

Patient-controlled morphine analgesia Oral fluid Moving patient to chair |

| Day 2 | Fluid diet Enhanced mobilisation Removal of urinary catheter |

Enhanced mobilisation |

| Day 3 | Soft diet Removal of drain |

Removal of urinary catheter Removal of nasogastric tube if draining <300 mL |

| Day 4 | Normal diet | Fluid diet Removal of drain |

| Day 5 | Discharge if no fever, pain can be controlled with oral analgesics and patient has adequate mobilisation | Soft diet |

| Day 6 | Normal diet | |

| Day 7 | Discharge if no fever, pain can be controlled with oral analgesics and patient has adequate mobilisation |

Although there was no formalised extubation protocol, extubation at the end of liver resection surgery or within 1 h after admission to ICU was expected; for pancreatic surgery where most patients went to ICU, extubation within 4 h was expected. There is no surgical high dependency unit at the Prince of Wales Hospital, Hong Kong.

Drains were removed as soon as possible when there was no biliary or pancreatic anastomotic leakage. In patients undergoing liver surgery, gradual resumption of diet from liquid to solid food was expected during the first 3 days after surgery. For Whipple's operation, the diet resumption was slower, starting from the fifth postoperative day, and a normal diet was expected by the seventh. For patients who could not tolerate oral intake by the seventh day after surgery, parenteral nutrition was given with a target of 25–30 kcal/kg.

Outcome measure

For the purposes of this study, we define failure of enhanced recovery protocol after HBP surgery as a composite measure of the following events: length of ICU stay more than 24 h after surgery, unplanned admission to ICU within 30 days after surgery, readmission to the hospital within 30 days after surgery, reoperation for complications and 30-day mortality. These events were chosen as markers of slow recovery and are common quality of care indicators. Unlike previous ERAS studies, we did not choose length of stay as a primary outcome as it has been shown that reductions in length of stay up to a median of 2 days may be related to changes in organisation of care and not to the effect of the ERAS programme.14

We collected patient demographics, smoking status, preoperative urinary cotinine concentration that was adjusted for creatinine level, American Society of Anesthesiologists’ Physical Status, Surgical Apgar Score,15 duration of surgery, ICU admission details, APACHE II (severity of illness score in patients admitted to ICU),16 preoperative liver function tests, indocyanine green test and coagulation tests, and failure events from the hospital electronic Clinical Management System database. The research staff collected postoperative morbidities (pulmonary, infectious, renal, gastrointestinal, cardiovascular, neurological, haematological, wound and severe pain) on the third day after surgery using a reliable and valid Postoperative Morbidity Survey questionnaire.17 The EQ-5D index, a health-related quality of life using a US set of reference weights, was measured on the third day after surgery,18 as the greatest difference in EQ-5D index between ERAHBPS and standard care occurs between postoperative days 2 and 5.19 Current smoking was defined as no smoking cessation within 2 months before surgery or if the patient had an adjusted urinary cotinine concentration ≥5 50 ng/mL within 48 h before surgery.10 The research staff was blinded to the urinary cotinine concentration results.

Statistical analysis

Continuous data were expressed as mean and SD or median and IQR. The 95% CI was estimated around the incidence of HBP surgery failure. Appropriate Student t tests, Mann-Whitney U tests, χ2 analyses or exact tests were used to compare factors associated with failure of enhanced recovery protocol. To adjust for multiple testing of individual postoperative morbidity events, a Bonferroni correction was used so that the significance criterion was set at p<0.0063. There were no missing data.

A generalised estimating equation (GEE) model with a Poisson distribution, log-link function and exchangeable correlation20 was used to obtain a common-effect relative risk (RR) of failure of enhanced recovery protocol after HBP surgery. This GEE model was more appropriate for analysis of composite measures and assumes that there is a single common exposure effect across all components used in the failure composite end point. We included elective ICU admission in the model as we considered this factor to be clinically important with regard to postoperative bed utilisation. The calibration and discrimination of the model was assessed using the Hosmer-Lemeshow goodness-of-fit test and estimating the area under the receiver characteristic operating curve (AUROC). Internal validation of the model was performed by bootstrapping 1000 samples and estimating the AUROC and 95% CI. A sensitivity analysis of the GEE model was performed by including adjusted urinary cotinine concentration as a continuous variable instead of smoking status as a categorical independent variable. Statistical analyses were performed using STATA (V.13.1) software (STATA Corp, College Station, Texas, USA).

Using PASS (V.11) software (NCSS, Kaysville, Utah, USA), a sample size of 190 (19 failure and 171 success) patients will achieve 80% power to detect a difference of 0.2 between the AUROC under the null hypothesis of 0.7 (fair discrimination) and an AUROC under the alternative hypothesis of 0.5 (no discrimination) using a two-sided z-test at a significance level of 0.05.

Results

Of the 217 consecutive patients undergoing HBP surgery, 23 were not eligible (10 not available in the ward at time of recruitment, 5 refusals, 4 already participated in the study, 3 unable to consent and 1 had renal impairment). There were 25 failures of enhanced recovery (12.9%, 95% CI 8.5% to 18.4%) in 194 patients undergoing major HBP surgery. Of the 94 elective ICU patients, 10 (10.6%) stayed in ICU for more than 24 h after surgery. One patient was admitted to ICU unexpectedly due to surgical emphysema and stayed in ICU for 43 h after surgery. There were 2 (2.1%) readmissions to ICU within 24 h (1 for acute renal failure/atrial fibrillation and 1 for atelectasis), 2 reoperations (1%) and 11 hospital readmissions (5.6%). The reasons for hospital readmissions were abdominal complications (n=5), wound complications (n=3), fever with or without chills (n=2) and jaundice (n=1). No patient died within 30 days after surgery.

The median postoperative length of hospital stay was longer in the failure group (13 days, 7–18) than in the successful group (7 days, 6–9; p=0.003). This was mainly due to longer median length of postoperative hospital stay in patients undergoing hepatic surgery failing enhanced recovery management (12 days, 7–17) compared with those successfully managed (7 days, 6–9; p=0.001). There were 26 patients undergoing pancreatic surgery. The median duration of postoperative hospital stay in patients undergoing pancreatic surgery failing and succeeding enhanced recovery management were 16 (5–35) and 10 (8–18) days, respectively (p=0.716). The median time from initial hospital discharge to readmission was 6 days (2–13).

The demographic and preoperative characteristics associated with failure of enhanced recovery protocol are shown in table 2. Of the 137 patients with preoperative indocyanine green test results, 14 (7.2%) were classified as borderline and 4 (2.1%) were poor. There was no significant association between indocyanine green test results and failure groups (p=0.735).

Table 2.

Demographic and preoperative factors associated with failure of enhanced recovery protocol after major hepatobiliary and pancreatic surgery

| Enhanced recovery protocol groups |

p Value | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Failure (n=25) | Success (n=169) | ||

| Mean age (SD), years | 57 (11) | 59 (11) | 0.498 |

| Males, n (%) | 19 (76) | 131 (78) | 0.866 |

| American Society of Anesthesiologists’ Physical Status, n (%) | |||

| I | 2 (8) | 25 (15) | 0.512 |

| II | 18 (72) | 121 (72) | |

| III/IV | 5 (20) | 23 (14) | |

| Current smoker, n (%) | 9 (36) | 35 (21) | 0.088 |

| Median adjusted cotinine, ng/mL (IQR) | 1.34 (0.60–265.82) | 1.07 (0.55–3.51) | 0.183 |

| Type of surgery, n (%) | |||

| Exploratory | 1 (4) | 5 (3) | 0.441 |

| Laparoscopic liver resection | 3 (12) | 28 (17) | |

| Minor open liver resection | 5 (20) | 62 (37) | |

| Major open liver±biliary reconstruction | 12 (48) | 52 (31) | |

| Whipple | 2 (8) | 15 (9) | |

| Other pancreatic surgery | 2 (8) | 7 (4) | |

| Magnitude of surgery, n (%) | |||

| Major | 4 (16) | 36 (21) | 0.541 |

| Ultramajor | 21 (84) | 133 (79) | |

| Low albumin (<35 g/L), n (%) | 2 (4) | 12 (7) | 0.698 |

| High bilirubin (µmol/L),* n (%) | 7 (28) | 27 (16) | 0.159 |

| Alkaline phosphatase (IU/L), n (%) | |||

| Normal† | 14 (56) | 123 (73) | 0.214 |

| Low | 1 (4) | 3 (2) | |

| High | 10 (40) | 43 (25) | |

| High ALT/GPT (IU/L), ‡ n (%) | 11 (44) | 23 (14) | 0.001 |

| Haemoglobin (g/dL), n (%) | |||

| Normal§ | 14 (56) | 121 (72) | 0.211 |

| Low | 10 (40) | 46 (27) | |

| High | 1 (4) | 2 (1) | |

| Platelets, n (%) | |||

| Normal (150–384×109/L) | 14 (56) | 117 (69) | 0.294 |

| Low | 10 (40) | 50 (30) | |

| High | 1 (4) | 2 (1) | |

| Prothrombin time, n (%) | |||

| Normal (9.5–12 s) | 19 (76) | 144 (85) | 0.423 |

| Low | 0 (0) | 1 (1) | |

| High | 6 (24) | 24 (14) | |

| Activated partial thromboplastin time, n (%) | |||

| Normal (28.2–37.4 s) | 22 (88) | 153 (91) | 0.914 |

| Low | 2 (8) | 10 (6) | |

| High | 1 (4) | 6 (4) | |

| High international normalised ratio, n (%) | 0 (0) | 2 (1) | 1.000 |

| Urinary creatinine (µmol/L), n (%) | |||

| Normal† | 20 (80) | 143 (85) | 0.815 |

| Low | 3 (12) | 17 (10) | |

| High | 2 (8) | 9 (5) | |

*High bilirubin defined as more than 19 µmol/L in men and more than 17 µmol/L in women.

†Age-specific and gender-specific range.

‡High ALT/GPT defined as more than 67 IU/L in men and more than 55 IU/L in women.

§Normal range is 13.2–17.2 g/dL for men and 11.9–15.1 g/dL for women.

ALT/GPT, alanine transaminase/glutamic-pyruvic transaminase.

The median duration of hepatic surgery was similar between failure (270 min, 186–336) and successful enhanced recovery groups (236 min, 180–315; p=0.348). There was no difference in the median duration of pancreatic surgery between failure (395 min, 192–641) and successful enhanced recovery groups (488 min, 291–560; p=0.933). The median Surgical Apgar Score was similar between failure (8, 6–9) and successful (8, 7–9) enhanced recovery groups (p=0.912).

Elective ICU admissions occurred in 13 (41.9%) patients undergoing laparoscopic liver resection, 19 (23.9%) minor open liver resection, 45 (70.3%) major open liver and/or biliary reconstruction, 15 (88.2%) Whipple and 2 (22.2%) other pancreatic surgery. Of the 94 elective ICU admissions, 17 (18.1%) patients failed enhanced recovery protocols after HBP surgery. Patients with elective ICU admissions were more likely to be enhanced recovery failures than patients sent to the ward after surgery (RRunadjusted=1.49, 95% CI 1.09 to 2.05). The median duration of ICU length of stay was longer in the failure group (25 h, 20–39) than in the successful enhanced recovery group (19 h, 17–22; p<0.001). However, the mean APACHE II score was similar between failure (13.6±3.8) and successful (12.3±3.5) enhanced recovery groups (p=0.150).

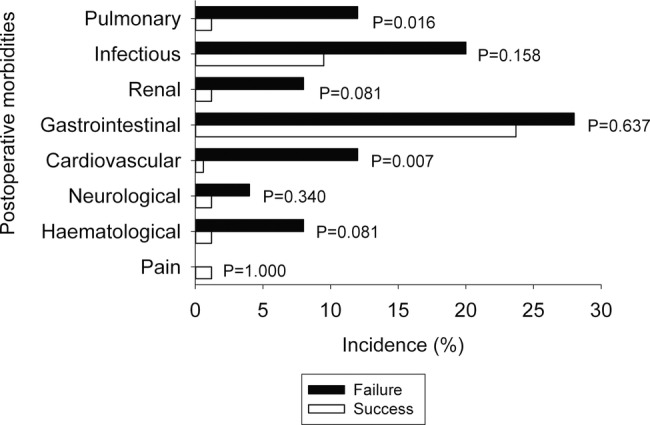

The overall incidence of postoperative morbidities was 35.1% (95% CI 28.4% to 42.2%). There was no reported wound dehiscence (requiring surgical exploration or drainage of pus from the operation wound with or without isolation of organisms)17 on the third postoperative day. There was no difference in the incidence of postoperative morbidities between groups according to the a priori Bonferroni correction p value criterion (figure 1). Patients with a postoperative morbidity were twice as likely to be a failure (RRunadjusted=2.36, 95% CI 1.13 to 4.91) than those without. There was no difference in the mean EQ-5D index between failure (0.53±0.3) and successful enhanced recovery groups (0.63±0.29; p=0.166).

Figure 1.

The incidence of postoperative morbidities on the third day after surgery by enhanced recovery protocol groups. To control for type I error at 0.05 from multiple comparisons, p<0.0063 was considered significant.

After adjusting for planned postoperative ICU care, current smoking, high preoperative alanine transaminase/glutamic-pyruvic transaminase (ALT/GPT) concentration and postoperative morbidities on the third day after surgery were significant risk factors associated with failure of enhanced recovery protocol (table 3). The GEE model had adequate calibration (Hosmer-Lemeshow goodness-of-fit χ2 8df, p=0.352) and excellent discrimination (AUROC=0.87, 95% CI 0.83 to 0.92).

Table 3.

Risk factors for failure in enhanced recovery protocol after major hepatobiliary and pancreatic surgery using the generalised estimating equation model

| Common-effect RR (95% CI) | p Value | |

|---|---|---|

| ICU admission | ||

| None | 1.00 | 0.104 |

| Elective | 0.41 (0.14 to 1.20) | |

| Smoking status | ||

| Never-smoker/ex smoker | 1.00 | 0.027 |

| Current smoker | 2.21 (1.10 to 4.46) | |

| ALT/GPT (IU/L)* | ||

| Normal | 1.00 | 0.001 |

| High | 3.55 (1.68 to 7.49) | |

| Any postoperative morbidity | ||

| None | 1.00 | 0.007 |

| Present on day 3 | 2.69 (1.30 to 5.56) | |

*High ALT/GPT defined as more than 67 IU/L in men and more than 55 IU/L in women.

ALT/GPT, alanine transaminase/glutamic-pyruvic transaminase; ICU, intensive care unit; RR, relative risk.

The results of a sensitivity analysis on the main GEE model using adjusted urinary cotinine concentration instead of smoking status are shown in table 4. Compared with patients with nil urinary cotinine concentration, the predicted adjusted risk for failure in enhanced recovery protocol in patients with urinary cotinine concentrations of 50, 500 and 1500 ng/mL were 1.04 (95% CI 1.01 to 1.07), 1.52 (95% CI 1.22 to 1.90) and 3.51 (95% CI 1.80 to 6.83), respectively. The GEE model had adequate calibration (Hosmer-Lemeshow goodness-of-fit χ2 8df, p=0.496) and excellent discrimination (AUROC=0.87, 95% CI 0.82 to 0.91).

Table 4.

Sensitivity analysis on the risk factors for failure in enhanced recovery protocol after major hepatobiliary and pancreatic surgery

| Common-effect RR (95% CI) | p Value | |

|---|---|---|

| ICU admission | ||

| None | 1.000 | 0.202 |

| Elective | 0.505 (0.176 to 1.444) | |

| Adjusted cotinine concentration (ng/mL)* | 1.001 (1.000 to 1.001) | <0.001 |

| ALT/GPT (IU/L)† | ||

| Normal | 1.000 | <0.001 |

| High | 4.626 (2.097 to 10.207) | |

| Any postoperative morbidity | ||

| None | 1.000 | 0.007 |

| Present on day 3 | 2.657 (1.312 to 5.379) | |

*Active smokers commonly defined as urinary cotinine concentration >50 ng/mL.21

†High ALT/GPT defined as more than 67 IU/L in men and more than 55 IU/L in women.

ALT/GPT, alanine transaminase/glutamic-pyruvic transaminase; ICU, intensive care unit; RR, relative risk.

Discussion

Our management of patients undergoing HBP surgery incorporated a small proportion of evidence-based components described in ERAS programmes for hepatic4 and pancreatic22 surgery. For every eight patients undergoing major HBP surgery, one was at risk of failing enhanced recovery protocols in major HBP surgery. However, no patients died within 30 days after surgery. This may be due to the majority of our patients (86%) classified as American Society of Anesthesiologists’ Physical Status grades I and II, benefits of planned bundles of care in the ERAS programme or good access to postoperative ICU care. Prolonged stay in ICU (12%) and hospital readmissions (6%) were the most common failure events. Our hospital readmission rate and 30-day mortality are within the range described in studies included in recent systematic reviews of fast-track liver resection and pancreatic surgery.1 2 22 23 Our patients who failed enhanced recovery protocols after major HBP surgery had, clinically, significantly longer ICU stays and postoperative stays in hospital.

Access to ICU admission after surgery affects outcomes.24 Under half (48.5%) of our patients had elective ICU admission after surgery. Patients with elective ICU admissions after surgery were high-risk patients as suggested by the results of the univariate analysis where they were 1.5 times more likely to be failures than patients sent to the ward after surgery. However, when the elective ICU admission variable was included in the GEE models, the common-effect RR, although not significant, suggested a possible protective effect on failure. A previous study showed that intensive care physician staffing was associated with better outcomes after hepatic resection from prompt diagnosis and treatment of non-surgical complications.7 Our incidence of ICU readmission (2.1%) within 24 h appears acceptable. Previous studies included in systematic reviews of fast-track HBP surgery1 2 22 23 have not reported the rate of ICU readmissions.

There is a paucity of studies examining the effect of smoking on fast-track surgery. Compared with conventional care programmes, smoking was associated with 30-day hospital readmissions (OR=1.60, 95% CI 1.05 to 2.44), but not with prolonged length of hospital stay of more than 4 days (OR=1.34, 95% CI 0.92 to 1.95) in patients undergoing fast-track hip and knee arthroplasty.25 However, current smoking was based on self-reported smoking history up to a month before hospital admission25 and the effect of smoking on enhanced recovery failure is likely to be underestimated as many smokers (17%) deny smoking before elective surgery.26 In contrast, we used self-reported smoking history and adjusted urinary cotinine concentration to increase the accuracy of preoperative smoking status data. We have shown that current smokers were up to four times more likely to be enhanced recovery failures compared with never-smokers and former smokers in the GEE model. The results of the sensitivity analysis using adjusted urinary cotinine concentration further strengthens the association between smoking and the risk of enhanced recovery failure. Thus, smoking cessation before HBP surgery would be expected to decrease the risk of enhanced recovery failures substantially. Smoking cessation at least 4 weeks, and preferably 8 weeks, before surgery significantly reduced the risk of postoperative respiratory and wound-healing complications.27 Smoking is a modifiable risk factor that surgeons and anaesthesiologists can work on when patients are booked for surgery.

Of all the preoperative liver function and coagulation tests performed, high ALT/GPT concentration was the only independent biochemical risk factor associated with enhanced recovery failures. The strong association is indicative of the high risk of operating on an acutely inflamed liver.28 A previous study29 found that alanine aminotransferase ≥70 IU/L was an independent risk factor (OR=2.02, 95% CI 1.33 to 3.07) for postoperative complications after hepatic resection for hepatocellular carcinoma.

Fast-track open liver resection was associated with a reduction in general complications as defined by the Postoperative Morbidity Survey17 by 36% (95% CI 16% to 52%).19 A direct comparison between our incidence of postoperative morbidities on the third day after surgery and Jones et al's19 study is difficult as the timing of their postoperative morbidities was not specified. Our GEE model found that patients with any postoperative morbidity on the third day after surgery were three times more likely to be an enhanced recovery failure than patients without reported postoperative morbidity. Specifically, after adjustment for multiple testing, cardiovascular events (diagnostic tests or treatment in the past 24 h for new myocardial infarction or ischaemia, hypotension, arrhythmias, cardiogenic pulmonary oedema or thrombotic events)17 were weakly associated with the risk of failure. Early postoperative morbidities are associated with longer duration of hospital stay30 and an increased risk of hospital readmission.31

Using a minimal important difference of 0.03,32 we found that patients in the enhanced recovery failure group appeared to have a lower health-related quality of life than in the successful group. Our health-related quality of life on the third day after surgery in the successful group was similar to those reported in the standard care group by Jones et al.19 Our practice does not include carbohydrate drink up to 2 h before surgery, pharmacological prophylaxis for deep vein thrombosis or the routine use of epidural anaesthesia.

Overall, the results of this study suggest that it is possible to identify a subgroup of patients requiring additional care to minimise perioperative morbidity and length of stay. Patients who are smokers, have high ALT/GPT concentration or are at a high risk of postoperative morbidities are likely to fail enhanced recovery protocol in HBP surgery. In defining who is at high risk of postoperative morbidities, the American Society of Anesthesiologists’ Physical Status grades III and IV and risk more than 50% estimated in the POSSUM-defined postoperative morbidity model may be useful as surrogate markers.17 For those patients at high risk of HBP surgery failure, elective postoperative ICU admission and measures targeted to avoid postoperative cardiorespiratory complications are warranted to reduce the risk of failure of enhanced recovery events.

There are several limitations of this study. First, we did not measure the compliance rate of individual components of the ERAHBPS programme. Recent studies suggest that better patient care and outcome can be achieved regardless of the number, combination, type and strength of evidence of the individual ERAS component.33 34 Second, the common-effect GEE analysis was influenced by the higher frequencies of prolonged ICU length of stay (12%) and hospital readmissions (6%) events than other components included in the definition of failure. Our sample size was too small for the use of an average relative-effect GEE analysis20 to address this problem. There is a potential for residual confounding despite the use of multivariate analyses in this cohort study. The applicability of the identified risk factors to select patients suitable for ERAHBPS programmes in other settings requires further validation. Finally, the failure outcomes were limited to the early to intermediate phases of recovery; we did not measure outpatient complications31 or late recovery outcomes, such as functional status and health-related quality of life beyond 1 month as recommended recently by Neville et al.35

In conclusion, patients who smoked, had elevated preoperative ALT/GPT or experienced postoperative morbidities were at risk of failing enhanced recovery protocols in major HBP surgery and may have benefited from additional care. Patients who failed enhanced recovery protocols in HBP surgery stayed in ICU and in the hospital longer.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Contributors: AL performed the statistical analyses and had full access to all the data in the study. AL drafted the manuscript and made substantial revisions. All authors were involved in the study concept and design of the study. CHC collected the data. AL, MWAC, CDG, KFL, YSC and PBSL interpreted the data. All authors made critical revisions of the manuscript for important intellectual content and approved the final version of the manuscript. AL is guarantor.

Funding: The work was substantially supported by the Health and Health Services Research Fund, Food and Health Bureau, Hong Kong SAR Government (Grant number: 08090311).

Competing interests: None.

Ethics approval: The Joint Chinese University of Hong Kong-New Territories East Cluster Clinical Research Ethics Committee approved this cohort study of patients undergoing major HBP surgery at the Prince of Wales Hospital in Hong Kong between January 2011 and November 2012 (CRE-2013.181).

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned, externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

References

- 1.Spelt L, Ansari D, Sturesson C, et al. Fast-track programmes for hepatopancreatic resections: where do we stand? HPB 2011;13:833–8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hall TC, Dennison AR, Bilku DK, et al. Enhanced recovery programmes in hepatobiliary and pancreatic surgery: a systematic review. Ann R Coll Surg Engl 2012;94:318–26 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lin DX, Li X, Ye QW, et al. Implementation of a fast-track clinical pathway decreases postoperative length of stay and hospital charges for liver resection. Cell Biochem Biophys 2011;61:413–19 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wong-Lun-Hing EM, van Dam RM, Heijnen LA, et al. Is current perioperative practice in hepatic surgery based on Enhanced Recovery After Surgery (ERAS) principles? World J Surg 2014;38:1127–40 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Schultz NA, Larsen PN, Klarskov B, et al. Evaluation of a fast-track programme for patients undergoing liver resection. Br J Surg 2013;100:138–43 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sanchez-Perez B, Aranda-Narvaez JM, Suarez-Munoz MA, et al. Fast-track program in laparoscopic liver surgery: theory or fact? World J Gastrointest Surg 2012;4:246–50 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dimick JB, Pronovost PJ, Lipsett PA. The effect of ICU physician staffing and hospital volume on outcomes after hepatic resection. J Intensive Care Med 2002;17:41–7 [Google Scholar]

- 8.Constantinides VA, Tekkis PP, Fazil A, et al. Fast-track failure after cardiac surgery: development of a prediction model. Crit Care Med 2006;34:2875–82 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lee A, Zhu F, Underwood MJ, et al. Fast-track failure after cardiac surgery: external model validation and implications to ICU bed utilization. Crit Care Med 2013;41:1205–13 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lee A, Chui PT, Chiu CH, et al. Risk of perioperative respiratory complications and postoperative morbidity in a cohort of adults exposed to passive smoking. Ann Surg 2014. [Epub ahead of print 6 Feb 2014]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lee KF, Cheung YS, Chong CN, et al. Laparoscopic versus open hepatectomy for liver tumours: a case control study. Hong Kong Med J 2007;13:442–8 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lee KF, Cheung YS, Wong J, et al. Randomized clinical trial of open hepatectomy with or without intermittent Pringle manoeuvre. Br J Surg 2012;99:1203–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Shontz R, Karuparthy V, Temple R, et al. Prevalence and risk factors predisposing to coagulopathy in patients receiving epidural analgesia for hepatic surgery. Reg Anesth Pain Med 2009;34:308–11 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Maessen JM, Dejong CH, Kessels AG, et al. Length of stay: an inappropriate readout of the success of enhanced recovery programs. World J Surg 2008;32:971–5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Reynolds PQ, Sanders NW, Schildcrout JS, et al. Expansion of the surgical Apgar score across all surgical subspecialties as a means to predict postoperative mortality. Anesthesiology 2011;114:1305–12 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Knaus WA, Draper EA, Wagner DP, et al. APACHE II: a severity of disease classification system. Crit Care Med 1985;13:818–29 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Grocott MP, Browne JP, Van der Meulen J, et al. The Postoperative Morbidity Survey was validated and used to describe morbidity after major surgery. J Clin Epidemiol 2007;60:919–28 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Shaw JW, Johnson JA, Coons SJ. US valuation of the EQ-5D health states: development and testing of the D1 valuation model. Med Care 2005;43:203–20 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jones C, Kelliher L, Dickinson M, et al. Randomized clinical trial on enhanced recovery versus standard care following open liver resection. Br J Surg 2013;100:1015–24 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mascha EJ, Sessler DI. Statistical grand rounds: design and analysis of studies with binary-event composite endpoints: guidelines for anesthesia research. Anesth Analg 2011;112:1461–71 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.SRNT Subcommittee on biochemical verification. Biochemical verification of tobacco use and cessation. Nicotine Tob Res 2002;4:149–59 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Coolsen MM, van Dam RM, van der Wilt AA, et al. Systematic review and meta-analysis of enhanced recovery after pancreatic surgery with particular emphasis on pancreaticoduodenectomies. World J Surg 2013;37:1909–18 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Coolsen MM, Wong-Lun-Hing EM, van Dam RM, et al. A systematic review of outcomes in patients undergoing liver surgery in an enhanced recovery after surgery pathways. HPB 2013; 15:245–51 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pearse RM, Moreno RP, Bauer P, et al. Mortality after surgery in Europe: a 7 day cohort study. Lancet 2012;380:1059–65 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jorgensen CC, Kehlet H. Outcomes in smokers and alcohol users after fast-track hip and knee arthroplasty. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand 2013;57:631–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lee A, Gin T, Chui PT, et al. The accuracy of urinary cotinine immunoassay test strip as an add-on test to self-reported smoking before major elective surgery. Nicotine Tob Res 2013;15:1690–5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wong J, Lam DP, Abrishami A, et al. Short-term preoperative smoking cessation and postoperative complications: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Can J Anaesth 2012;59:268–79 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Schroeder RA, Marroquin CE, Bute BP, et al. Predictive indices of morbidity and mortality after liver resection. Ann Surg 2006;243:373–9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Taketomi A, Kitagawa D, Itoh S, et al. Trends in morbidity and mortality after hepatic resection for hepatocellular carcinoma: an institute's experience with 625 patients. J Am Coll Surg 2007;204:580–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Davies SJ, Francis J, Dilley J, et al. Measuring outcomes after major abdominal surgery during hospitalization: reliability and validity of the Postoperative Morbidity Survey. Perioper Med (Lond) 2013;2:1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lucas DJ, Sweeney JF, Pawlik TM. The timing of complications impacts risk of readmission after hepatopancreatobiliary surgery. Surgery 2014;155:945–53 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Barton GR, Sach TH, Doherty M, et al. An assessment of the discriminative ability of the EQ-5D index, SF-6D, and EQ VAS, using sociodemographic factors and clinical conditions. Eur J Health Econ 2008;9:237–49 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gianotti L, Beretta S, Luperto M, et al. Enhanced recovery strategies in colorectal surgery: is the compliance with the whole program required to achieve the target? Int J Colorectal Dis 2014;29:329–41 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Nicholson A, Lowe MC, Parker J, et al. Systematic review and meta-analysis of enhanced recovery programmes in surgical patients. Br J Surg 2014;101:172–88 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Neville A, Lee L, Antonescu I, et al. Systematic review of outcomes used to evaluate enhanced recovery after surgery. Br J Surg 2014;101:159–71 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.