Much controversy surrounds equivalence and switchability between brand name and generic antiepileptic drug products or among different generic products. Clinicians are faced with conflicting publications, editorials, position statements from professional organizations, and statements from the FDA about the safety of generic substitution (1–3). The FDA has funded several ongoing trials testing bioequivalence of antiepileptic drugs in people with epilepsy (4–7). In addition, the FDA has begun implementing modified bioequivalence standards for drugs that fulfill criteria for narrow therapeutic index (NTI), and the FDA is in the process of determining which medications fulfill its criteria for NTI status (8). Further, the FDA has enumerated the following general characteristics of NTI drugs: 1) little separation between therapeutic and toxic doses (or the associated drug concentrations), 2) subtherapeutic concentrations lead to serious therapeutic failure, 3) subject to therapeutic drug monitoring, 4) possess low-to-moderate (i.e., ≤30%) within-subject variability, and 5) in clinical practice, doses often adjusted in very small increments (<20%).

The FDA collected literature, new drug application, and amended new drug application (ANDA) data to assess whether lamotrigine when used as an antiepileptic drug qualifies as an NTI drug (9). Based on these sources, the FDA could not find any data indicating that lamotrigine would qualify as an NTI drug. Specifically, there was little data that blood levels were used other than during pregnancy, and the magnitude of dose changes was rarely reported in clinical trials—if dose changing was allowed at all. We speculated that many of the NTI characteristics—especially subtherapeutic concentrations and dose adjustments—were common in general clinical practice for lamotrigine but not reported in the medical literature. We therefore enlisted the help of the Q-PULSE panel with the goal of determining from the Q-PULSE survey participants how they use therapeutic drug monitoring and the magnitude of lamotrigine dose changes that are typically used in practice.

The Q-PULSE panel was organized by the American Epilepsy Society in 2012 (10). It is a panel of epilepsy specialist physicians chosen from epilepsy centers belonging to the National Association of Epilepsy Centers representing a broad cross-section of Epilepsy Centers across the United States. The aim of the Q-PULSE program is to capture expert opinion on issues for which quality evidence is lacking by having panel members complete online surveys on specific topics.

For the lamotrigine survey, the cases and questions were created by Michael Privitera and Michel Berg (principal investigators for Equivalence Among Antiepileptic Drug Generic and Brand Products in People With Epilepsy-EQUIGEN studies), with comments from the EQUIGEN steering committee. The EQUIGEN studies are FDA-funded antiepileptic drug generic bioequivalence studies. Cases and questions were provided to the FDA Office of Generic Drugs staff, who provided comments. The Q-PULSE Steering Committee approved the final version to adhere to general rules on survey length and question types.

Questions were of two types: case scenarios with questions on concentration testing and dosing, and more general questions, for example, “In which of these situations would you obtain lamotrigine blood levels?” The survey opened on December 29, 2013, and closed with data compiled February 4, 2014. There were a total of 113 responses from the 200-member panel, a 57% response rate.

Survey Results

The first two case scenarios and then two general questions explored when respondents would obtain blood level monitoring for loss of seizure control or adverse effects and the impact that a concentration result had on their clinical thinking.

Case 1 (Figures 1 and 2)

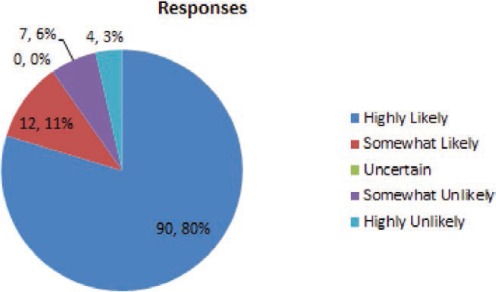

FIGURE 1.

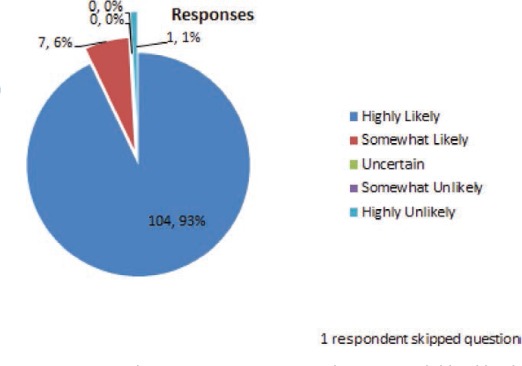

What is the likelihood that you would check a lamotrigine blood level to assess a possible drug-drug interaction?

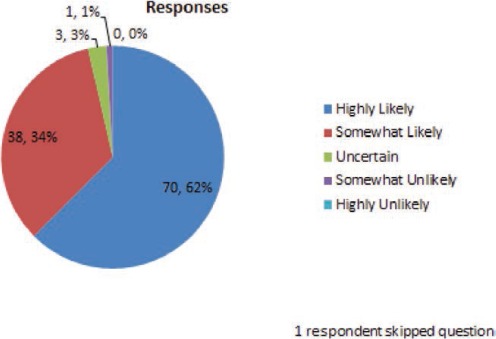

FIGURE 2.

A trough blood level is 2.5 mcg/ml. In your opinion, what is the likelihood that the seizure was related to this drop in blood level?

A 30-year-old woman has well-controlled seizures for 3 years on lamotrigine monotherapy at 300 mg daily (150 mg twice per day) with trough blood concentrations in the 4–6 mcg/ml range. She begins receiving an oral contraceptive with a combination of an estrogen and a progestin. One month later, she experiences a seizure. She assures you she has been compliant with both medications.

Case 2 (Figures 3, 4, 5 and 6)

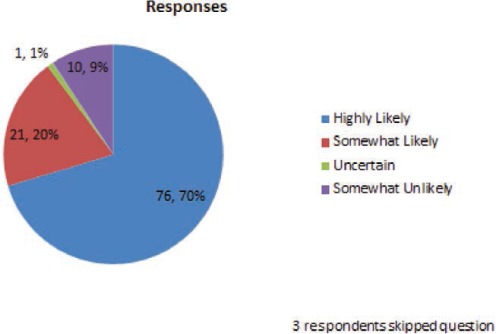

FIGURE 3.

What is the likelihood you will check a lamotigine blood level to assess for a possible drug-drug interaction?

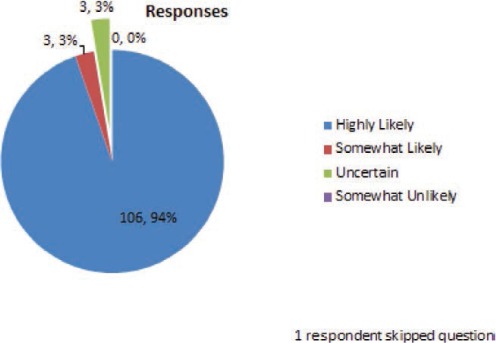

FIGURE 4.

What is the likelihood that the adverse effects the patient is experiencing are related to lamotrigine?

FIGURE 5.

For the same case scenario (#2) above, a trough blood level is checked and comes back at 16 mcg/ml. What is the likelihood that the adverse effects are related to this increase in blood level?

FIGURE 6.

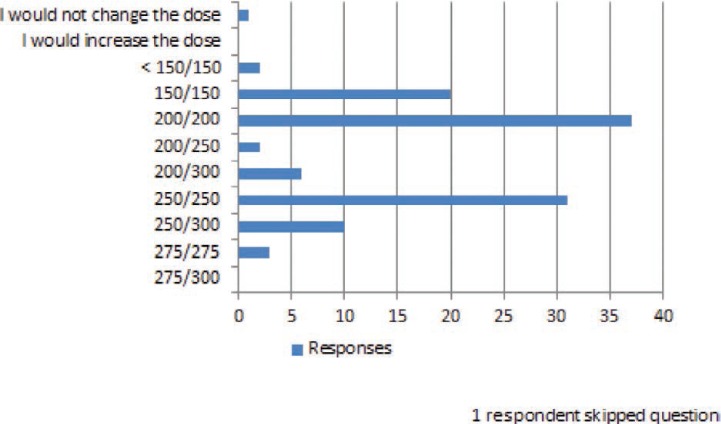

The next lamotrigine dose you would like to use is:

A 42-year-old man with idiopathic generalized epilepsy has been receiving lamotrigine 300 mg twice daily with trough levels in the 8–10 mcg/ml range. In the past several months, he has had 3 tonic–clonic seizures and frequent myoclonus. For better seizure control, his physician added valproate 250 mg twice daily. The patient has no further seizures or myoclonus, but after 2 weeks, he is experiencing dizziness and diplopia, usually maximally about 2 hours after he takes his lamotrigine.

The next two questions were general questions unrelated to a specific case scenario.

FIGURE 7.

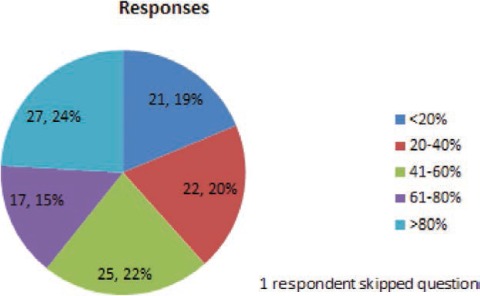

Thinking about the patients you treat with lamotrigine (excluding patients who are pregnant), what percentage of these patients have received at least once yearly lamotrigine blood level monitoring?

FIGURE 8.

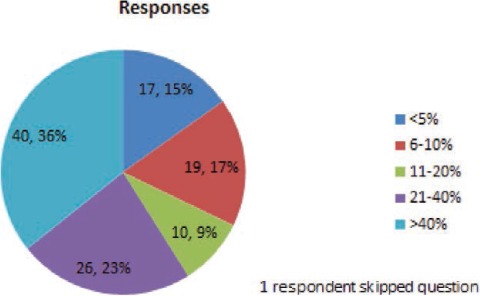

For what percent of your patients on lamotrigine (excluding patients who are pregnant) do you obtain regular blood levels and use the blood level result to help guide lamotrigine dose adjustment? (The interval between levels can be short or long).

The next two case scenarios were designed to determine the specific dose increment size in the clinical situation where symptoms of toxicity or increased seizures developed in a previously well-controlled patient.

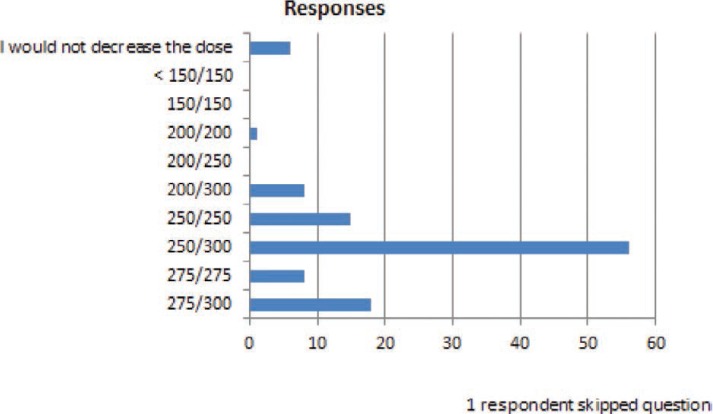

FIGURE 9.

You are treating a patient who is taking lamotrigine 300 mg bid for medical refractory epilepsy who has had a >50% improvement in seizure frequency since adding lamotrigine. More than 6 months after being on unchanged therapy, the patient develops what you believe are peak level side effects of ~30 minutes of dizziness starting 1.5–2 hours after the morning dose ~2 times per week. You attribute side effects to the lamotrigine and you decide to decrease the lamotrigine dose. The next dose you would most likely use is:

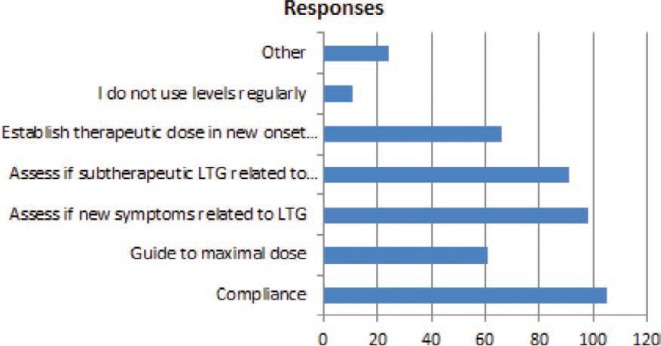

The final general question used a multi-answer format to assess the circumstances where lamotrigine concentrations were useful in clinical care.

Discussion

This Q-PULSE survey provides a snapshot of how a group of neurologists who provide specialized care for people with epilepsy use lamotrigine in clinical practice. The survey response was strong at 57%. Data on use of lamotrigine blood levels and magnitude of lamotrigine dose adjustments were obtained, which can inform decisions about whether a drug qualifies for NTI categorization.

The combination of case-related and general questions indicate that this group of epileptologists uses lamotrigine blood levels frequently to guide the therapy with lamotrigine. More than 90% of respondents answered that they are highly or somewhat likely to use lamotrigine blood levels to check for a drug–drug interaction, whether the interacting drug was suspected of inhibiting (80% highly likely) or inducing (70% highly likely) lamotrigine metabolism.

Nineteen percent of respondents answered that they get yearly levels on less than 20% of their patients, whereas 24% of respondents get yearly levels on more than 80% of their patients. More than one-third (36%) of respondents answered that they obtain regular blood levels and use the results to guide dose adjustments for more than 40% of their patients. Fewer than 10% of respondents indicated that they do not use blood levels regularly. These findings show that there is incomplete consensus among epileptologists on the routine use of blood level monitoring to guide dose adjustments, but most of the survey respondents will use blood level monitoring in specific clinical situations.

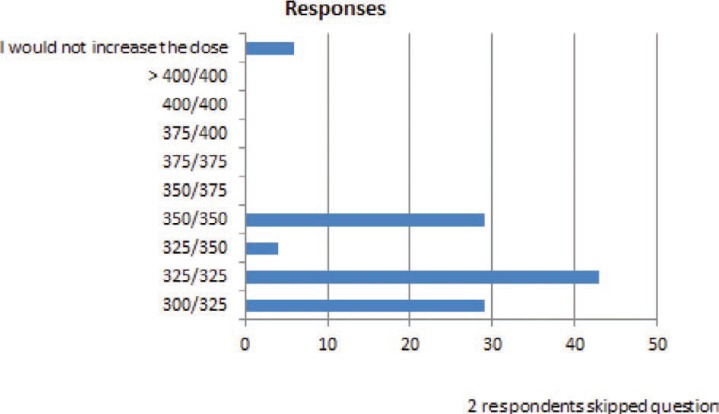

In several common clinical situations where small dose changes might occur, many respondents indicated that they would make dose changes of <20% of the total daily dose. When a dose reduction was required because of a presumed drug–drug interaction (figure 6), almost 50% of respondents answered that they would have reduced the lamotrigine dose by less than 20% of the total daily dose. In the question in Figure 10, a patient who had previously experienced adverse effects on the current dose of lamotrigine required in increased dose because of loss of seizure control. For this patient, over 90% of the responders would increase the dose, and all of these responders stated that they would have increased it by <20% of the total daily dose. Of importance, the doses used for these questions were specifically selected to be within the range of doses used for lamotrigine in clinical practice.

FIGURE 10.

You are treating a patient who is taking a lamotrigine 300 mg twice daily and has been seizure free for almost a year. When this dose was first reached, the patient experienced dizziness, but this resolved after several weeks. The patient has experienced two seizures in the last 2 months without obvious triggers, denies missing medications, and blood levels are in the same range (8–10 mcg/ml) they have been for the past year. You decide to increase the dose. The next dose you would most likely use is:

This survey is not an exhaustive exploration of the clinical management approaches for lamotrigine use in epilepsy, but it does represent common clinical situations of people with epilepsy treated with lamotrigine at epilepsy centers. The survey is limited in its generalizability because the cases are hypothetical. However, the goal of the survey was neither to precisely define appropriate lamotrigine dose changes nor to establish guidelines for when to measure lamotrigine blood levels. The survey is valuable because it demonstrates that practicing epileptologists report a standard of care that commonly uses lamotrigine blood levels to guide therapy and often adjust the dose of lamotrigine in small increments (less than 20% of the daily dose) in several frequently encountered clinical situations. This type of data cannot be ascertained by a review of the published medical literature or medication prescribing information. We believe the data gathered in this survey should help inform the decision about the NTI status of lamotrigine; and similar data should be sought for other antiepileptic drugs.

FIGURE 11.

In which of the following circumstances do you use lamotrigine blood levels (the interval between levels can be short or long):

Acknowledgments

The authors appreciate the comments of Jacqueline French, MD, who initiated the Q-PULSE project, as well as the EQUIGEN investigators, Jerzy Szaflarski, MD, PhD, Barbara Dworetzky, MD and Lebron Paige, MD.

Footnotes

Editor's Note: Authors have a Conflict of Interest disclosure which is posted under the Supplemental Materials (209KB, docx) link.

References

- 1.Liow K, Barkley GL, Pollard JR, Harden CL, Bazil CW, American Academy of Neurology Position statement on the coverage of anticonvulsant drugs for the treatment of epilepsy. Neurology. 2007;68:1249–1250. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000259400.30539.cc. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Davit BA, Nwakama PE, Buehler GJ, Conner DP, Haidar SH, Patel DT, Yang Y, Yu LX, Woodcock J. A review of 12 years of bioequivalence data from the United States Food and Drug Administration. Ann Pharmacother. 2009;43:1583–1597. doi: 10.1345/aph.1M141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Privitera M. Generic substitution of antiepileptic drugs: What's a clinician to do? Neurol Clin Pract. 2013;3:161–164. doi: 10.1212/CPJ.0b013e31828d9fc9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.University of Cincinnati. Equivalence among antiepileptic drug generic and brand products in people with epilepsy: Chronic-dose 4-period replicate design (chronic dose) [Clinical trial] http://www.clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT01713777?term=privitera+and+ generic&rank=1. Accessed May 11, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 5.University of Cincinnati. Equivalence among antiepileptic drug generic and brand products in people with epilepsy: Single-dose 6-period replicate design (EQUIGEN single-dose study) [Clinical trial] http://www.clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT01733394?term=privitera+and+generic&rank=2. Accessed May 11, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Vince & Associates Clinical Research. A study in stable epilepsy patients comparing brand and generic divalproex sodium extended release tablets [Clinical trial] http://www.clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT01898676?term=valproate+generic&rank=1. Accessed May 11, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 7.University of Maryland. Lamotrigine bioequivalence [Clinical trial] http://www.clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT01995825?term=lamotrigine+generic&rank=3. Accessed May 11, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Davit BM, Chen ML, Conner DP, Haidar SH, Kim S, Lee CH, Lionberger RA, Makhlouf FT, Nwakama PE, Patel DT, Schuirmann DJ, Yu LX. Implementation of a reference-scaled average bioequivalence approach for highly variable generic drug products by the US Food and Drug Administration. AAPS J. 2012;14:915–924. doi: 10.1208/s12248-012-9406-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cai W, Ting T, Polli J, Berg M, Privitera M, Jiang W. Lamotrigine, a Narrow Therapeutic Index Drug or Not? American Academy of Neurology; Philadelphia: April 2014. Abstract P4.267. [Google Scholar]

- 10.French JA. Taking the “Pulse” of our society with Q-PULSE. Epilepsy Curr. 13:304. doi: 10.5698/1535-7597-13.6.304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]