Abstract

Objectives

This study compared the profile of intentional drug overdoses (IDOs) presenting to emergency departments in Ireland and in the Western Trust Area of Northern Ireland between 2007 and 2012. Specifically the study aimed to compare characteristics of the patients involved, to explore the factors associated with repeated IDO and to report the prescription rates of common drug types in the population.

Methods

We utilised data from two comparable registries which monitor the incidence of hospital-treated self-harm, recording data from deliberate self-harm presentations involving an IDO to all hospital emergency departments for the period 1 January 2007 to 31 December 2012.

Results

Between 2007 and 2012 the registries recorded 56 494 self-harm presentations involving an IDO. The study showed that hospital-treated IDO was almost twice as common in Northern Ireland than in Ireland (278 vs 156/100 000, respectively).

Conclusions

Despite the overall difference in the rates of IDO, the profile of such presentations was remarkably similar in both countries. Minor tranquillisers were the drugs most commonly involved in IDOs. National campaigns are required to address the availability and misuse of minor tranquillisers, both prescribed and non-prescribed.

Keywords: PUBLIC HEALTH, EPIDEMIOLOGY

Strengths and limitations of this study.

Intentional drug overdose (IDO) is the most common form of hospital-treated suicidal behaviour and the most common type of drug involved is psychotropic medication, in particular benzodiazepines/minor tranquillisers. The prevalence of drugs taken in IDOs has been shown to reflect their prescription and availability in the population.

There have been few comparative studies of countries in relation to the incidence of IDOs, the profile of patients, the types of drugs involved and the availability of these drugs in the populations.

This study has, for the first time, compared the profile of hospital-treated IDO in two countries (Ireland and Northern Ireland).

While the profile of these presentations is similar across both samples, a higher incidence of IDOs is being observed in Northern Ireland.

This study further raises the question that is there a higher prevalence of mental disorders in Northern Ireland, or is this a difference due to increased help-seeking behaviour. Further research is required to establish a clearer picture of the circumstances and psychological background of IDO presentations in both countries.

Introduction

Intentional drug overdose (IDO) is the most common form of hospital-treated suicidal behaviour,1 2 accounting for 65–85%2 3 of self-harm presentations to emergency departments and 1–2% of all hospital admissions.4–6 The most common type of drug taken in IDOs is psychotropic medication, in particular benzodiazepines/minor tranquillisers.7–11 Analgesics such as paracetamol are also common, particularly in England.12 It has been shown that the vast majority of IDO patients take their own medication whether prescribed or available over the counter.11 13 14 The prevalence of drugs taken in IDOs has been shown to reflect their prescription and availability in the population.6 15

Studies of the drugs taken in IDO have led to effective changes in policy and legislation. In Ireland and the UK, paracetamol pack sizes were reduced and co-proxamol/distalgesic was withdrawn from the market, measures which were associated with reduced suicidal behaviour.16 17

There have been few comparative studies of countries in relation to the incidence of IDOs, the profile of patients, the types of drugs involved and the availability of these drugs in the populations. We aimed to examine these differences for the Western Area of Northern Ireland and the Republic of Ireland utilising two comparable registries which monitor the incidence of hospital-treated self-harm. We compare characteristics of the patients involved, explore the factors associated with repeated IDO and report the prescription rates of common drug types in the population.

Methods

National registry of deliberate self-harm Ireland

This Registry was established in 2002 and its primary purpose is to determine and monitor the incidence and patterns of hospital-treated deliberate self-harm. Since 2006, all emergency departments in Ireland (population 4 585 500)18 have contributed data to the Registry. This study involved data from deliberate self-harm presentations involving an IDO to all hospital emergency departments for the period 1 January 2007 to 31 December 2012.

Northern Ireland Registry of Deliberate Self-Harm

The Northern Ireland Registry of Deliberate Self-Harm is part of the Northern Ireland Suicide Prevention Strategy ‘Protect Life—A Shared Vision’ and has been collecting data since 2007, using a methodology adapted from that of the National Registry of Deliberate Self-Harm Ireland. This study involved data from deliberate self-harm presentations involving an IDO to the three emergency departments in Northern Ireland's Western Trust Area (population 298 303)19 for the period 1 January 2007 to 31 December 2012. The Western Area provides representation of all settlement bands in Northern Ireland20 and has a similar incidence and pattern of hospital-treated self-harm as Northern Ireland as a whole.21

Definition of self-harm

Both registries involved in this study use the following as their definition of deliberate self-harm: ‘an act with non-fatal outcome in which an individual deliberately initiates a non-habitual behaviour, that without intervention from others will cause self-harm, or deliberately ingests a substance in excess of the prescribed or generally recognised therapeutic dosage, and which is aimed at realising changes that the person desires via the actual or expected physical consequences’.22 This definition was derived for the Euro/WHO multicentre study and it is consistent with that used in the multicentre monitoring project in England.1 The definition includes acts involving varying levels of suicidal intent and various underlying motives such as loss of control, cry for help or self-punishment.

Data collection

Data collection is carried out by data registration officers who work specifically for the registries. The data registration officers receive standard training in data collection methods and attend regular review meetings. Searches for cases of deliberate self-harm involve a combination of manually checking consecutive presentations to the emergency departments, selecting potential cases on the basis of keyword searches and triage coding by hospital staff. Flexibility in case finding is required because of differences between hospital systems of recording emergency department presentations. However, the data registration officers operate independent of the emergency department staff, with the priority of ensuring standardised case ascertainment.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

IDO cases were included in this study where it was clear that the self-harm was deliberately inflicted. The following examples are not considered to be self-harm cases: unintentional overdoses such as an individual taking excessive medication in the case of illness (without intention to harm oneself) or an individual who presents to hospital following an overdose of street drugs taken for recreational purposes. In addition, a distinction between IDO and deliberate self-poisoning is made. IDO encompasses methods of self-harm with ICD-10 code of X60-64 (overdose of drugs and medicaments), and cases with any of these codes were included in the analysis for this paper. In this study, medicinal and street drug overdoses are covered by the term IDO. Cases involving other poisons (eg, chemicals) and only alcohol, regardless of intent, are not included in this sample.

Data items

Both registries have a core data set including the following variables: gender, date of birth, date and hour of attendance at hospital, method(s) of self-harm and recommended next care. In addition, patient initials (in an encrypted format) and area of residence, coded to administrative area, are recorded. For IDO cases, the following data are also recorded: drug taken and the total number of tablets taken (by drug name). Drugs were classified into groups of drug type by consulting the WHO's anatomical-therapeutic-chemical (ATC) system of drug classification, the British National Formulatory (BNF) and the Irish Monthly Index of Medical Specialities (MIMS).

Availability of psychotropic drugs

Data on sales of psychotropic drugs to pharmacies in Ireland and Northern Ireland for the study period 2007–2012 were supplied by IMS Health Inc (http://www.imshealth.com). The number of tablets sold to pharmacies per 1000 population in Ireland and Northern Ireland was calculated to give an indication of the availability of psychotropic drugs in the communities.

Data analysis

For the years 2007–2012, the annual incidence rate of IDOs per 100 000 population was calculated for the total, male and female populations (and for age–sex subgroups) based on the number of persons who presented to hospital in the catchment area. We calculated 95% CIs for the rates using the Normal Approximation of Poisson Distribution. These intervals are displayed by error bars in the relevant chart.

Repeat acts are defined as presentation to a hospital emergency department in the catchment area due to an act of self-harm within 12 months of leaving hospital following treatment in an emergency department for an index IDO act, during the years 2007–2011.

A multivariate logistic regression model was developed to identify factors related to the index IDO that were independently associated with repeated self-harm within 12 months. ORs and their 95% CIs are reported with the associated level of significance.

Results

Characteristics of hospital-treated IDO

Between 2007 and 2012, there were 56 494 IDO presentations to emergency departments, 50 394 (89%) in Ireland and 6100 (11%) in the Western Area of Northern Ireland (henceforth referred to as Northern Ireland). The characteristics of IDO presentations were very similar in both countries (table 1). In Ireland and Northern Ireland, almost 60% of IDO presentations to hospitals were made by women and by persons under 35 years of age. The mean number of tablets taken in an IDO act was 30 and approximately one in six made a self-harm presentation to hospital within 12 months of their index IDO act.

Table 1.

Demographics of intentional drug overdose sample from Ireland and Northern Ireland

| Characteristic | Ireland n=50 394 (%) |

Northern Ireland n=6100 (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | ||

| Male | 41.5 | 43.4 |

| Female | 58.5 | 56.6 |

| Age (years) | ||

| <15 | 1.8 | 1.5 |

| 15–24 | 28.5 | 26.7 |

| 25–34 | 24.1 | 22.6 |

| 35–44 | 22.0 | 25.1 |

| 45–54 | 15.0 | 17.6 |

| 55+ | 8.3 | 6.5 |

| Number of tablets (mean) | 30 | 29 |

| Alcohol involvement | 43.2 | 59.5 |

| Rate of repetition | 15.9 | 17.9 |

| Aftercare | ||

| General ward | 36.3 | 63.6 |

| Psychiatric ward | 8.0 | 4.6 |

| Patient refused admission | 1.1 | 2.8 |

| Patient left without recommendation | 12.9 | 5.9 |

| Not admitted | 41.7 | 23.1 |

The involvement of alcohol in IDO presentations was significantly higher in Northern Ireland (60% vs 43%; χ2=586.74, df=1, p<0.001). The countries also differed in relation to recommended aftercare (χ2=1922.87, df=4, p<0.001). In Northern Ireland, patients were more often admitted to a general ward following an IDO presentation and less likely to leave before aftercare was recommended.

Incidence of IDOs

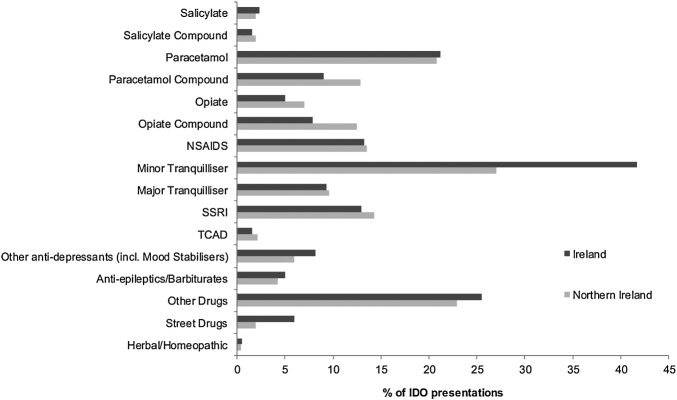

Overall, the rate of IDO presentations in Northern Ireland (278 (95% CI 271 to 286) per 100 000) was 78% higher than what it was in Ireland (156 (95% CI 155 to 158) per 100 000). Despite this difference, the pattern in the incidence rate when examined by age was similar for both countries (figure 1). The peak rate was observed among 20–24-year-olds in Ireland (328/100 000) and Northern Ireland (578/100 000). The incidence rate decreased with increasing age, with a slight secondary peak seen among those aged 35–49 years. The IDO rate was very low, and similar in both countries, among over 60-year-olds.

Figure 1.

Incidence of hospital-treated intentional drug overdose (IDO) by 5-year age–sex group.

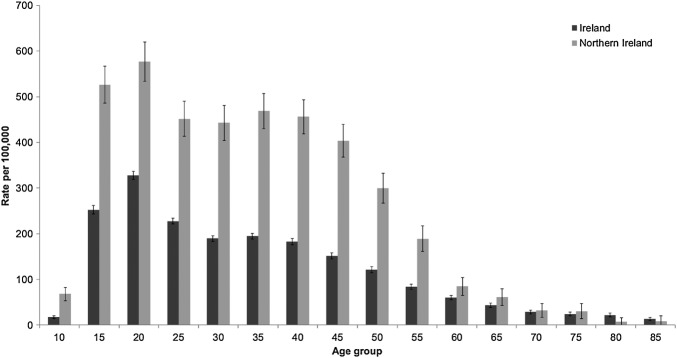

Drugs involved in IDOs

Figure 2 illustrates the categories of drugs which were used in IDOs, for both countries. A minor tranquilliser was involved in 40% of IDOs, and their use was higher in Ireland than in Northern Ireland (42% vs 27%, χ2=489.85, df=1, p<0.001). Drugs including only paracetamol were involved in 21% of IDO presentations in both countries but paracetamol-compound drugs were more common in Northern Ireland (13% vs 9%, χ2=95.86, df=1, p<0.001). The only other common drug type involved in IDOs was antidepressants (including selective serotonin re-uptake inhibitors (SSRIs), tricyclic antidepressants (TCADs) and mood-stabilisers), present in 22% of acts. SSRIs were the most common type of antidepressants (used in 13% of acts). ‘Other drugs’ were taken in 25% of cases.

Figure 2.

Drugs used intentional drug overdose (IDO).

Although the involvement of opiate-based drugs was low overall, they were more common in IDO presentations in Northern Ireland (opiate-compound drugs 13% vs 8%; χ2=149.38, df=1, p<0.001; opiate-only drugs 7% vs 5%; χ2=47.09, df=1, p<0.001). While relatively rare, street drugs were involved more often in IDOs in Ireland (6% vs 2%; χ2=175.06, df=1, p<0.001).

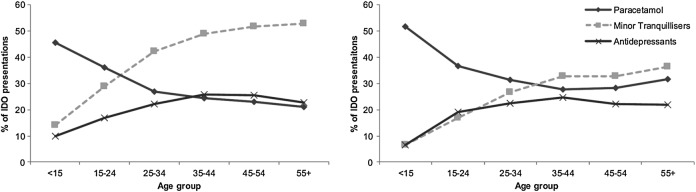

The use of minor tranquillisers increased with age, especially in Ireland (figure 3). The prevalence of antidepressant drugs was similar in IDOs by persons aged over 25 years. Paracetamol-containing drugs were most common in IDOs by young people.

Figure 3.

Drugs taken by age for Ireland (left) and Northern Ireland (right). Chart adapted from Hawton et al.1

Repeated self-harm following IDO

The rate of repetition of self-harm after an index IDO act was similar in Ireland and Northern Ireland, with 16% of individuals representing to an emergency department within 12 months (table 2). The risk of repetition was increased among those aged less than 55 years, when the initial IDO also involved self-cutting and alcohol and when 40–69 tablets were taken in the act. Patients admitted to a psychiatric ward after the index IDO were more likely to repeat. Psychotropic drugs (minor and major tranquillisers, SSRIs, antiepileptics and other antidepressants) were associated with higher rates of repetition. After adjustment for the range of factors examined, there was still an increased rate of repetition following IDO presentations in Northern Ireland.

Table 2.

Factors associated with repeated self-harm within 12 months of an intentional drug overdose presentation

| Factor | Repetition N (%) |

Adjusted OR | 95% CI |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | |||

| Male | 2454 (17.3) | 1.08* | 1.01 to 1.16 |

| Female | 3014 (15.3) | 1.00 | Ref |

| Age group (years) | |||

| <15 | 119 (16.7) | 1.78*** | 1.35 to 2.35 |

| 15–24 | 1595 (14.9) | 1.44*** | 1.23 to 1.68 |

| 25–34 | 1332 (16.5) | 1.38*** | 1.18 to 1.62 |

| 35–44 | 1296 (18.5) | 1.59*** | 1.36 to 1.86 |

| 45–54 | 785 (16.8) | 1.40*** | 1.18 to 1.65 |

| 55+ | 341 (12.5) | 1.00 | Ref |

| Alcohol | 2555 (16.9) | 1.15*** | 1.07 to 1.23 |

| Self-cutting | 502 (26.3) | 1.94*** | 1.69 to 2.22 |

| Tablets taken | |||

| <10 | 586 (15.4) | 1.00 | Ref |

| 10–19 | 1019 (14.5) | 1.00 | 0.89 to 1.12 |

| 20–29 | 810 (15.1) | 1.04 | 0.92 to 1.17 |

| 30–39 | 503 (16.6) | 1.13 | 0.99 to 1.29 |

| 40–49 | 383 (18.7) | 1.30*** | 1.12 to 1.50 |

| 50–59 | 209 (17.9) | 1.20* | 1.00 to 1.44 |

| 60–69 | 161 (18.5) | 1.26* | 1.03 to 1.54 |

| 70–79 | 72 (14.5) | 0.88* | 0.67 to 1.16 |

| 80+ | 240 (17.3) | 1.12 | 0.94 to 1.33 |

| Admission | |||

| General ward | 2130 (15.7) | 1.00 | Ref |

| Psychiatric ward | 587 (25.1) | 1.75*** | 1.55 to 1.99 |

| Patient refused admission | 70 (17.8) | 1.12 | 0.82 to 1.52 |

| Patient left without recommendation | 678 (17.9) | 1.16* | 1.03 to 1.31 |

| Not admitted | 2003 (14.5%) | 0.93 | 0.86 to 1.01 |

| Drug-type | |||

| Salicylate | 98 (12.2) | 0.80 | 0.63 to 1.03 |

| Salicylate compound | 77 (12.1) | 0.92 | 0.71 to 1.19 |

| Paracetamol | 983 (13.4) | 0.98 | 0.89 to 1.07 |

| Paracetamol compound | 450 (12.9) | 0.91 | 0.68 to 1.23 |

| Opiate | 284 (16.2) | 1.10 | 0.94 to 1.29 |

| Opiate compound | 407 (13.2) | 0.97 | 0.70 to 1.33 |

| NSAID | 685 (13.6) | 0.96 | 0.86 to 1.06 |

| Minor tranquilliser | 2548 (19.5) | 1.55*** | 1.44 to 1.68 |

| Major tranquilliser | 551 (22.8) | 1.56*** | 1.38 to 1.76 |

| SSRI | 802 (18.4) | 1.16** | 1.05 to 1.28 |

| TCAD | 75 (14.5) | 0.98 | 0.73 to 1.31 |

| Other antidepressants | 469 (19.1) | 1.26*** | 1.11 to 1.42 |

| Antiepileptic/barbiturate | 291 (22.6) | 1.54*** | 1.31 to 1.81 |

| Other drugs | 1341 (15.6) | 1.06 | 0.97 to 1.16 |

| Street drugs | 374 (18.5) | 1.12 | 0.94 to 1.34 |

| Country | |||

| Ireland | 4868 (15.9) | 1.00 | Ref |

| Northern Ireland | 600 (17.9) | 1.24*** | 1.10 to 1.39 |

*p<0.05; **p<0.01; ***p<0.001.

Availability of psychotropic drugs

Antidepressants (including mood stabilisers) were by far the most available type of psychotropic drugs in pharmacies. There was greater availability of psychotropic drugs in Northern Ireland than in Ireland (table 3). This was most pronounced for antidepressants and mood stabilisers and for tranquillisers, which were almost twice as available in Northern Ireland.

Table 3.

Number of tablets of psychotropic drugs sold to pharmacies in Ireland and Northern Ireland, per 1000 population (2007–2012)

| Type of psychotropic drug | Northern Ireland | Ireland | Rate ratio (Ref Ireland) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Antidepressants and mood stabilisers | 1302 | 725 | 1.80 |

| Tranquillisers | 388 | 203 | 1.91 |

| Hypnotics and sedatives | 508 | 431 | 1.18 |

| Antiepileptics | 338 | 277 | 1.22 |

| Antipsychotics | 271 | 194 | 1.40 |

Discussion

In this study, we compared the profile of IDO presentations to emergency departments in Ireland and the Western Area of Northern Ireland. We found that the incidence rate of IDO presentations to hospital and the availability of antidepressants and tranquillisers were twice as high in Northern Ireland. Despite this, the profile of IDO presentations in terms of gender, age, the type of drug and the number of tablets taken were similar in both countries.

In both countries, minor tranquillisers were the drugs most commonly involved in IDOs. The findings of this study in relation to the overall involvement of minor tranquillisers differ from UK studies, where benzodiazepines were reported to have been involved in 14.8% of self-poisoning episodes,23 and are considerably lower than that reported by a Spanish study of deliberate overdose where benzodiazepines were involved in 65% of cases.7 Paracetamol is the most commonly used drug in IDOs in England.1 There are similar regulations in relation to pack sizes of paracetamol in England and Northern Ireland, but the proportion of IDOs in the latter is more similar to that in Ireland, where different pack sizes are available. This may be due to the overall sales of paracetamol, which is worthy of further investigation. Variations in the use of medications by age were also observed in this study, with paracetamol involvement in IDOs most common in younger age groups, while minor tranquillisers and antidepressants were more common in older adults. These findings are consistent with those reported by Townsend et al12 and Hendrix et al.9

Alcohol involvement in IDO presentations was higher than that reported by other studies9 and higher in Northern Ireland than in Ireland. However, the rate of alcohol involvement in Northern Ireland was very similar to that reported in the UK, suggesting a cultural pattern of alcohol misuse.1 3 Overall, the patterns of alcohol involvement by age and gender are consistent with those observed by Hawton et al.1

The rate of repetition following an index IDO episode was higher in Northern Ireland than in Ireland. However, both rates were similar to that reported by a previous systematic review24 and within the range of 14–23% of recent UK studies based on 1-year-person-based rates of repetition.3 25 26 Significant variation in repetition was observed across drug types. Despite having low toxicity,7 this study found that the rates of repetition involving minor tranquillisers in particular are relatively high. This is in line with Cooper et al's3 Manchester Self-Harm Rule which indicates that cases of self-harm where benzodiazepines are not involved are at a lower risk for repetition.

The drugs taken in IDOs are generally thought to reflect ease of access or prescription patterns in that country.5 27 The results of this study indicated that the incidence of IDO presentations to hospital and the availability of psychotropic medication are significantly higher in Northern Ireland than in Ireland. The findings reflect those reported by the Irish National Advisory Committee on Drugs, where a lifetime prevalence of tranquilliser use and antidepressant use was 14% and 10% in Ireland and 21% and 22% in Northern Ireland, respectively.28 These findings indicate a higher prevalence of psychiatric disorders and mental illness in Northern Ireland. This is further supported by studies which have found a high prevalence of DSM-IV disorders in the Northern Ireland population29 and of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD).30 DSM-IV disorders are highly prevalent in the Northern Ireland population and are on the high end of the scale when compared with international figures.29 31 It is argued that the high incidence of PTSD in the Northern Ireland population indicates that the effects of chronic trauma exposure continue to impact negatively on mental health in Northern Ireland.30 However, rather than simply pointing to a higher prevalence of psychiatric disorders in Northern Ireland, the higher IDO rates found in our study could reflect better access to health services. It has been indicated that 50% patients with mood disorders sought treatment in the first year following onset and suggested that treatment adequacy among individuals seeking treatment in Northern Ireland was higher than in the USA or Europe.31 The delays between initial onset of disorders and seeking treatment (particularly in substance disorders) however reflect a lack of awareness31 and this, along with the high percentage of alcohol involved in IDOs suggests that more targeted interventions are needed to address underlying mental health disorders in the general population.

Conversely, both countries in this study have different healthcare systems. As part of the UK, Northern Ireland residents have free healthcare at the point of delivery under the National Health Service. In addition to this, all prescriptions dispensed in Northern Ireland are free of charge. In Ireland, however the Health Service Executive (HSE) operates a medical card scheme, where free access to services is means-tested. Without a medical card, there is a fee for each hospital emergency department visit. For prescription sales a small charge applies to each dispensed prescription for those with medical cards, however for those without this card the full value of the prescription is charged. This difference in emergency department visits may account for the larger rate of self-harm and IDO presentations to emergency departments in Northern Ireland, given that each visit is without charge. In addition, prescribing rates and the availing of prescription medication by residents of Northern Ireland may be partially explained by the cost of such medication. Further work is required to investigate how charges associated with prescription of medication and presentation to hospital have an impact on incidence rates.

It has been previously argued that the involvement of certain prescription medications in IDOs is related to their prescription, despite the established efficacy of psychotropic drugs in treating psychiatric conditions. Previous studies have highlighted the importance of considering risk of IDO among patients prescribed minor tranquillisers.7 11 13 A previous Irish study found that having a prescription for a minor tranquilliser increased the risk of using a psychotropic drug in an IDO, independent of any other studied factor. A high proportion of this sample had been in contact with the psychiatric services at the time of their overdose, indicating an underlying need for monitoring prescribed medication, particularly among older people.13 In addition, the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) guidelines state that the prescription of psychotropic medication should be considered a public health issue.32

Strengths and limitations

This study compared findings from two highly comparable registry systems which utilise the same definition of self-harm and drug type, and similar operating procedures. The large sample size allowed for the calculation of precise rates of IDO presentations in Ireland and the Western Area of Northern Ireland.

There are however a number of limitations due to the limited range of data recorded by the registries. We could not explore the management and treatment of presentations to emergency departments following an IDO, whether an individual's own prescribed medication was used in the act, or if the patient had a psychiatric diagnosis. The study period was also too short to observe trends in the rate of IDO presenting to emergency departments in Ireland and Northern Ireland, but further work will address this research question. Northern Ireland self-harm data for the study period were only available for the Western Area. Future work would include self-harm data from other trust regions of Northern Ireland. A further limitation is that the prescription rates are produced for Northern Ireland, and not just for the study area in this study.

Conclusion

The results of this study have, for the first time, compared the profile of hospital-treated IDO in samples from two countries. Remarkably, the profile of these presentations is similar across both samples, particularly in relation to the type of drug used in IDOs. Despite this similarity, the incidence of IDOs in the Western Area of Northern Ireland was higher than in Northern Ireland. A first look at the rates of prescription of medication in both countries further raises the question of whether there is a higher prevalence of mental disorders in Northern Ireland, or this difference is due to increased help-seeking behaviour in Northern Ireland. Further research is required to establish a clearer picture of the circumstances and psychological background of IDO presentations in both countries.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge everyone who contributed to the development of both the Irish National Registry of Deliberate Self-Harm and the Northern Ireland Registry of Deliberate Self-Harm. Special thanks are also due to the data registration officers who collected the data and to the staff of various hospitals who facilitated the work.

Footnotes

Contributors: PC, EG, LC and AOC compiled the data. PC and EG designed and performed the data analysis, and also reviewed the literature and drafted the paper. BB facilitated interpretation of the findings and helped in drafting the paper. BB and IJP oversaw the design of the study. All authors contributed to the development of the Registry in their respective countries and approved the final draft of the paper.

Funding: The Irish National Registry of Deliberate Self-Harm is funded by the Irish Health Service Executive's National Office for Suicide Prevention. The Northern Ireland Registry of Deliberate Self-Harm is funded by the Department of Health, Social Services and Public Safety, Northern Ireland through the Public Health Agency.

Competing interests: None.

Ethics approval: Ethical approval has been granted by the Office for Research Ethics in Northern Ireland (ORECNI) for the Northern Ireland Registry in April 2007. In Ireland, ethical approval of the registry was granted by the National Research Ethics Committee of the Faculty of Public Health Medicine.2 8.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: To access data from the Irish National Registry of Deliberate Self-Harm, please contact the National Suicide Research Foundation (info@nsrf.ie). To access data from the Northern Ireland Registry of Deliberate Self-Harm, please contact the Public Health Agency (reception.pha@hscni.net).

References

- 1.Hawton K, Bergen H, Deborah C, et al. Self-harm in England: a tale of three cities. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 2007;42:513–21 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Perry IJ, Corcoran P, Fitzgerald AP, et al. The incidence and repetition of hospital-treated deliberate self harm: findings from the world's first national registry. PLoS ONE 2012;7:e31663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cooper J, Kapur N, Dunning J, et al. A clinical tool for assessing risk after self-harm. Ann Emerg Med 2006;48:459–66 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Buykx P, Dietze P, Ritter A, et al. Characteristics of medication overdose presentations to the ED: how do they differ from illicit drug overdose and self-harm cases? Emerg Med J 2010;27:499–503 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Prescott K, Stratton R, Freyer A, et al. Detailed analyses of self-poisoning episodes presenting to a large regional teaching hospital in the UK. Br J Clin Pharmacol 2009;68:260–8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wazaify M, Kennedy S, Hughes C, et al. Prevalence of over-the-counter drug-related overdoses at Accident and Emergency departments in Northern Ireland—a retrospective evaluation. J Clin Pharm Ther 2005;30:39–44 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Baca-García E, Diaz-Sastre C, Saiz-Ruiz J, et al. How safe are psychiatric medications after a voluntary overdose? Eur Psychiatry 2002;17:466–70 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Griffin E, Arensman E, Wall A, et al. National Registry of Deliberate Self Harm Annual Report 2012 Cork: National Suicide Research Foundation, 2013 [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hendrix L, Verelst S, Desruelles D, et al. Deliberate self-poisoning: characteristics of patients and impact on the emergency department of a large university hospital. Emerg Med J 2012;30:e9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Staikowsky F, Theil F, Mercadier P, et al. Change in profile of acute self drug-poisonings over a 10-year period. Hum Exp Toxicol 2004;23:507–11 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tournier M, Grolleau A, Cougnard A, et al. Factors associated with choice of psychotropic drugs used for intentional drug overdose. Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci 2009;259:86–91 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Townsend E, Hawton K, Harriss L, et al. Substances used in deliberate self-poisoning 1985–1997: trends and associations with age, gender, repetition and suicide intent. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 2001;36:228–34 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Corcoran P, Heavey B, Griffin E, et al. Psychotropic medication involved in intentional drug overdose: implications for treatment. Neuropsychiatry 2013;3:285–93 [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hawton K, Ware C, Mistry H, et al. Why patients choose paracetamol for self poisoning and their knowledge of its dangers. BMJ 1995;310:164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Crombie IK, Mcloone P. Does the availability of prescribed drugs affect rates of self poisoning? Br J Gen Pract 1998;48:1505–6 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Corcoran P, Reulbach U, Keeley H, et al. Use of analgesics in intentional drug overdose presentations to hospital before and after the withdrawal of distalgesic from the Irish market. BMC Clin Pharmacol 2010;10:6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hawton K, Townsend E, Deeks J, et al. Effects of legislation restricting pack sizes of paracetamol and salicylates on self poisoning in the United Kingdom: before and after study. BMJ 2001;322:1203–7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.CSO. StatBank Annual Population Estimates. 2011. http://www.cso.ie/px/pxeirestat/Statire/SelectVarVal/Define.asp?maintable=PEA01&PLanguage=0(accessed 17 Oct 2013).

- 19.Northern Ireland Statistics and Research Agency. Historial mid-year population estimate publications. Home population by sex & single year of age 2010. NISRA. http://www.nisra.gov.uk/demography/default.asp17.htm(accessed 17 Oct 2013).

- 20.Northern Ireland Statistics and Research Agency. Report of the Inter-Departmental Urban-Rural Definition Group: Statistical Classification and Delineation of Settlements Belfast: Northern Ireland Statistics and Research Agency, 2005 [Google Scholar]

- 21.Public Health Agency. Northern Ireland Registry of Self-Harm: Annual Report 2012/2013 Derry: Public Health Agency, 2013 [Google Scholar]

- 22.Schmidtke A, Bille-Brahe U, De Leo D, et al. Attempted suicide in Europe: rates, trends and sociodemographic characteristics of suicide attempters during the period 1989–1992. Results of the WHO/EURO Multicentre Study on Parasuicide. Acta Psychiatr Scand 1996;93:327–38 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bergen H, Hawton K, Waters K, et al. Epidemiology and trends in non-fatal self-harm in three centres in England: 2000–2007. Br J Psychiatry 2010;197:493–98 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Owens D, Horrocks J, House A. Fatal and non-fatal repetition of self-harm: Systematic review. Br J Psychiatry 2002;181:193–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kapur N, Cooper J, King-Hele S, et al. The repetition of suicidal behavior: a multicenter cohort study. J Clin Psychiatry 2006;67:1599–609 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lilley R, Owens D, Horrocks J, et al. Hospital care and repetition following self-harm: multicentre comparison of self-poisoning and self-injury. Br J Psychiatry 2008;192:440–5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Windfuhr K, Kapur N. International perspectives on the epidemiology and aetiology of suicide and self-harm. In: O’ Connor R, Platt S, Gordon J, eds. International handbook of suicide prevention: research, policy and practice. Oxford: John Wiley & Sons, Oxford, 2011:27–58 [Google Scholar]

- 28.National Advisory Commity on Drugs and Alcohol. Drug use in Ireland and Northern Ireland. 2010/11 Drug prevalence survey: Sedatives or tranquillisers and anti-depressants results. Dublin: National Advisory Commity on Drugs and Alcohol, 2012 [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bunting BP, Murphy SD, O'Neill SM, et al. Lifetime prevalence of mental health disorders and delay in treatment following initial onset: evidence from the Northern Ireland Study of Health and Stress. Psychol Med 2012;42:1727–39 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ferry F, Bunting B, Murphy Set al. Traumatic events and their relative PTSD burden in Northern Ireland: a consideration of the impact of the ‘Troubles’. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 2014;49:435–46 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bunting BP, Murphy SD, O'Neill SM, et al. Prevalence and treatment of 12-month DSM-IV disorders in the Northern Ireland study of health and stress. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 2013;48:81–93 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Self-harm: the short-term physical and psychological management and secondary prevention of self-harm in primary and secondary care. [CG 16]. London: National Institute for Health and Care Excellence, 2004 [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.