Abstract

Objectives

Left heart disease (LHD) is the main cause of pulmonary hypertension (PH), but little is known regarding the predictors of adverse outcome of PH associated with LHD (PH-LHD). We conducted a systematic review to investigate the predictors of hospitalisations for heart failure and mortality in patients with PH-LHD.

Design

Systematic review.

Data sources

PubMed MEDLINE and SCOPUS from inception to August 2013 were searched, and citations identified via the ISI Web of Science.

Study selection

Studies that reported on hospitalisation and/or mortality in patients with PH-LHD were included if the age of participants was greater than 18 years and PH was diagnosed using Doppler echocardiography and/or right heart catheterisation. Two reviewers independently selected studies, assessed their quality and extracted relevant data.

Results

In all, 45 studies (38 from Europe and USA) were included among which 71.1% were of high quality. 39 studies were published between 2003 and 2013. The number of participants across studies ranged from 46 to 2385; the proportion of men from 21% to 91%; mean/median age from 63 to 82 years; and prevalence of PH from 7% to 83.3%. PH was consistently associated with increased mortality risk in all forms of LHD, except for aortic valve disease where findings were inconsistent. Six of the nine studies with data available on hospitalisations reported a significant adverse effect of PH on hospitalisation risk. Other predictors of adverse outcome were very broad and heterogeneous including right ventricular dysfunction, functional class, left ventricular function and presence of kidney disease.

Conclusions

PH is almost invariably associated with increased mortality risk in patients with LHD. However, effects on hospitalisation risk are yet to be fully characterised; while available evidence on the adverse effects of PH have been derived essentially from Caucasians.

Keywords: Pulmonary hypertension, left heart disease, outcome, mortality, predictors, hospitalization

Strengths and limitations of this study.

Our search strategy was likely limited by its focus on a full-report article published in English and French, and traceable via PubMed MEDLINE and/or SCOPUS.

Important heterogeneity in the included studies precluded the pooling of data to perform a meta-analysis.

This is the first systematic review on determinants of hospitalisations and mortality in patients with pulmonary hypertension associated with left heart disease, which presents the available up-to-date and high-quality evidence on the subject matter.

Introduction

Pulmonary hypertension (PH) describes a group of disorders resulting from an increase in pulmonary vascular resistance, pulmonary blood flow, pulmonary venous pressure or a combination of these features.1 Based on shared pathological and haemodynamic characteristics, and therapeutic approaches, five clinical groups of PH have been distinguished2 with PH associated with left heart disease (PH-LHD) or PH group 2 credited to be the most frequent form of PH in contemporary clinical settings.3 Indeed, PH is common in patients with LHD, where it often reflects the background LHD, but has also been reported to be a maker of disease severity and unfavourable prognosis. Patients with PH-LHD have more severe symptoms, worse tolerance to effort, experience higher hospitalisation rates and are more likely to receive an indication of the need for cardiac transplant3 with major implications for the quality of life of patients and healthcare costs. Several studies have reported PH-LHD to be associated with increased mortality, both in patients with systolic dysfunction and those with preserved left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF).3–6 Furthermore, the presence of preoperative PH has been associated with poor outcomes in patients with valve disease undergoing valve replacement.7 However, there are still several gaps in the existing evidence, including the prevalence of PH-LHD and measurement of the true impact of PH on symptoms and outcome of various LHDs. Equally, little is known regarding the effect of the severity of PH on hospitalisations, rehospitalisations and death, and their co-factors in patients with LHD. Considering the number of recent advances in the management of PH, it is likely that a better understanding of the impact of PH-LHD on major outcomes might assist the clinical management of patients with PH.

We performed a systematic review of the existing literature to determine the predictors of hospitalisation and mortality in patients with PH secondary to LHDs including systolic dysfunction, diastolic dysfunction and/or valve disease. Additionally, we aimed to assess whether the severity of PH affects the risk of the two outcomes.

Methods

We searched MEDLINE via PubMed and SCOPUS from inception to August 2013 for all published studies on PH-LHD, using a combination of key words described in the online supplementary box 1. All searches were restricted to studies in humans published in ‘English’ or ‘French’ languages. In addition, we manually searched the reference lists of eligible studies and relevant reviews, and traced studies that had cited them through the ISI Web of Science for any relevant published and unpublished data. Two independent reviewers (AD and APK) performed the study selection, data extraction and quality assessment; and disagreements were resolved by consensus or consulting a third reviewer (KS).

Studies that reported on hospitalisation and/or mortality in patients with PH-LHD were included if the following criteria were met: (1) age of participants greater than 18 years; (2) Right ventricular systolic pressure (RVSP) measured by transthoracic Doppler echocardiography (DE) and calculated from the maximum tricuspid regurgitation jet velocity using the modified Bernoulli equation (4v2) and adding right atrial pressure (RAP). RAP could be a fixed value from 5 to 10 mm Hg, could have been estimated clinically using the jugular venous pressure (JVP), or estimated by measuring the inferior vena cava size and change with spontaneous respiration using echocardiography; and/or (3) mean pulmonary artery pressure (mPAP) measured by right heart catheterisation (RHC) or by DE. We excluded narrative reviews and case series. Studies on persistent PH following heart transplantation were not included because of the complexity of the classification of PH in this population.

The following variables were extracted from each study: publication year, country of origin of the study, study design, study population's demographics, the mean/median follow-up duration, the outcome predicted, the proportion of measurable RVSP, the mean/median baseline RVSP or mPAP, the prevalence of PH, the readmission rate, the mortality rate with odds ratio (OR) or hazard ratio (HR) for PH where reported and the predictors of outcome including the tricuspid annular plan systolic excursion (TAPSE). One study8 reported the effect of PH in relation with survival. Effects on mortality were obtained by taking the inverse of the HR for survival.

Quality assessment

The methodological quality of the selected studies was assessed using the Quality In Prognosis Studies (QUIPS) tool, designed for systematic reviews of prognostic studies through an international expert consensus (table 1).52 The QUIPS contains six domains assessing the following: (1) bias due to patient selection; (2) attrition; (3) measurement of prognostic factors; (4) outcome measurement; (5) confounding on statistical analysis and reporting results; and (6) confounding on presentation. In prognosis studies designed to predict a specific outcome based on a combination of several possible prognostic factors, confounding is not an issue. Therefore, the items on confounding were considered irrelevant for our quality assessment. The remaining 17 items of the five categories each were scored to assess the quality of the included studies. For each study, the five domains were scored separately as high (+), moderate (±) or low (−) quality (ie, presenting a low, moderate or high risk of bias, respectively). To strengthen the discriminative capacity of the QUIPS, we used the scoring algorithm developed by de Jonge et al,53 as explained, described in detail in the online supplementary table.

Table 1.

Results of quality assessment of studies on mortality and readmissions for heart failure in patients with pulmonary hypertension associated with left heart disease

| N | Study | Country/ethnicity | Design | Statistical methods | Study participation | Study attrition | Measurement of prognostic factors | Assessment of outcomes | Statistical analysis and presentation | Quality score (points) | Quality: +=high ±=moderate −=low |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Merlos et al9 | Spain | Prospective hospital based cohort | KM, Cox regression | 13.5 | 15 | 10 | 15 | 15 | 68.5 | + |

| 2 | Agarwal et al10 | USA—ethnicity data in 98 patients (63% whites) | Retrospective hospital based cohort | KM, Cox regression | 13.5 | 7.5 | 12.5 | 15 | 15 | 63.5 | + |

| 3 | Agarwal11 | USA—96% blacks | Prospective hospital based cohort | KM, Cox regression | 12 | 10 | 10 | 15 | 15 | 62 | + |

| 4 | Aronson et al12 | USA | Prospective hospital based cohort | Cox regression | 15 | 15 | 15 | 15 | 12.5 | 72.5 | + |

| 5 | Bursi et al13 | USA Caucasians and blacks |

Prospective population based cohort study | KM, Logistic regression | 15 | 12.5 | 12.5 | 12.5 | 15 | 65 | + |

| 6 | Strange et al14 | Armadale-Australia | Retrospective population based cohort | KM, Logistic and Cox regression | 15 | 7.5 | 10 | 12.5 | 12.5 | 58.5 | ± |

| 7 | Mutlak et al15 | USA | Prospective hospital based cohort | KM, Logistic and Cox regression, KM |

13.5 | 15 | 10 | 15 | 15 | 69 | + |

| 8 | Tatebe et al 16 | Japan | Prospective hospital based cohort | KM, Logistic and Cox regression | 15 | 10 | 15 | 15 | 15 | 72.5 | + |

| 9 | Adhyapak et al8 | India | Prospective hospital based cohort | Cox regression | 13.5 | 10 | 10 | 12.5 | 5 | 53.5 | ± |

| 10 | Stern et al17 | USA | Retrospective hospital based cohort | KM, Cox regression | 13.5 | 15 | 12.5 | 12.5 | 12.5 | 66 | + |

| 11 | Lee et al18 | Korea | Prospective hospital based cohort | KM, Cox regression | 15 | 15 | 15 | 12.5 | 15 | 72.5 | + |

| 12 | Møller et al19 | USA | Prospective hospital based cohort | KM, Logistic regression | 13.5 | 15 | 12.5 | 15 | 15 | 71 | + |

| 13 | Cappola et al20 | USA, 35% blacks and 65% whites | Prospective hospital based cohort | KM, Cox regression | 13.5 | 7.5 | 12.5 | 15 | 15 | 62.5 | + |

| 14 | Szwejkowski et al21 | UK | Retrospective hospital based cohort | KM, Cox regression | 13.5 | 10 | 10 | 15 | 15 | 61 | + |

| 15 | Abramson et al22 | USA | Prospective hospital based cohort | KM, Cox regression | 12 | 15 | 10 | 15 | 12.5 | 64.5 | + |

| 16 | Kjaergaard et al23 | Denmark | Prospective hospital based cohort | KM, Cox regression | 13.5 | 15 | 12.5 | 15 | 15 | 71 | + |

| 17 | Shalaby et al24 | USA, 95% Caucasians | Retrospective hospital based cohort | KM, Cox regression | 13.5 | 12.5 | 15 | 15 | 15 | 71 | + |

| 18 | Damy et al25 | UK | Prospective hospital based cohort | KM, Logistic and Cox regression | 15 | 10 | 15 | 15 | 15 | 70 | + |

| 19 | Ristow et al26 | USA | Prospective hospital based cohort | Logistic regression | 13.5 | 12.5 | 10 | 15 | 5 | 48.5 | ± |

| 20 | Grigioni et al27 | Italy | Retrospective cohort | KM, Logistic regression | 13.5 | 12.5 | 12.5 | 15 | 15 | 68.5 | ± |

| 21 | Levine et al28 | USA, mainly Caucasians (78.3%) | Retrospective cohort | No Logistic regression, no KM analysis | 12 | 10 | 10 | 7.5 | 2.5 | 42 | − |

| 22 | Lam et al29 | USA | Prospective observational community based cohort | KM, Logistic regression | 12 | 15 | 10 | 15 | 12.5 | 68 | + |

| 23 | Khush et al30 | Multicentric USA and Canada | Prospective cohort in the ESCAPE trial | KM | 15 | 10 | 15 | 15 | 12.5 | 68.5 | + |

| 24 | Ghio et al31 | Italy | Prospective cohort | KM, Cox regression | 13.5 | 12.5 | 12.5 | 12.5 | 12.5 | 63.5 | + |

| 25 | Wang et al32 | China | Retrospective cohort | KM | 12 | 12.5 | 12.5 | 12.5 | 5 | 54.5 | ± |

| 26 | Ghio et al33 | Italy | Prospective cohort | KM, Cox and Logistic regression | 13.5 | 10 | 10 | 15 | 15 | 63.5 | + |

| 27 | Naidoo et al34 | South Africa, Blacks | Retrospective cohort | No Logistic regression, no Kaplan Meier analysis | 12 | 7.5 | 10 | 5 | 7.5 | 42 | − |

| 28 | Fawzy et al35 | Saudi Arabia | Prospective cohort | No Logistic regression, no Kaplan Meier | 12 | 10 | 12.5 | 15 | 7.5 | 57 | ± |

| 29 | Roseli et al36 | USA | Retrospective hospital based cohort | KM, Cox regression | 13.5 | 10 | 10 | 15 | 12.5 | 63.5 | ± |

| 30 | Melby et al37 | USA | Retrospective hospital based cohort | KM, Cox regression | 13.5 | 12.5 | 10 | 15 | 15 | 66 | + |

| 31 | Le Tourneauet al 38 | France, mainly Caucasians | Prospective hospital based cohort | KM, Cox regression | 13.5 | 10 | 10 | 15 | 15 | 63.5 | + |

| 32 | Parker et al7 | USA | Retrospective hospital based cohort | KM, Cox regression | 12 | 15 | 12.5 | 15 | 15 | 71 | + |

| 33 | Kainuma et al39 | Japan, Asians | Retrospective hospital based cohort | KM, Cox regression | 10.5 | 10 | 12.5 | 12.5 | 10 | 55.5 | ± |

| 34 | Barbieri et al40 | Multicentric (Europe and USA) | Prospective hospital based cohort | KM, Cox regression | 13.5 | 15 | 12.5 | 15 | 15 | 71 | + |

| 35 | Manners et al41 | United Kingdom | Retrospective hospital based cohort | No regression analysis, no KM estimation | 10.5 | 7.5 | 5 | 5 | 2.5 | 30.5 | − |

| 36 | Malouf et al42 | USA | Prospective hospital based cohort | KM, Cox and Logistic regression | 10.5 | 10 | 10 | 15 | 12.5 | 58 | + |

| 37 | Khandhar et al43 | USA | Retrospective hospital based cohort | KM, Cox regression | 13.5 | 10 | 10 | 15 | 12.5 | 61 | ± |

| 38 | Zuern et al44 | Germany | Prospective hospital based cohort | KM, Cox regression | 15 | 7.5 | 10 | 15 | 15 | 62.5 | + |

| 39 | Ben-Dor et al45 | USA | Prospective hospital based cohort | KM, Logistic regression | 15 | 10 | 10 | 15 | 15 | 68 | + |

| 40 | Yang et al46 | USA | Retrospective hospital based cohort | KM, Cox and logistic regression | 15 | 7.5 | 15 | 12.5 | 15 | 65 | + |

| 41 | Nozohoor et al47 | Sweden | Retrospective cohort | KM, Cox and Logistic regression | 13.5 | 10 | 10 | 15 | 12.5 | 61 | + |

| 42 | Ward and Hancock48 | UK | Retrospective cohort | No KM, no Logistic or Cox regression | 12 | 5 | 2.5 | 7.5 | 2.5 | 29.5 | − |

| 43 | Ghoreishi et al49 | USA | Retrospective cohort | KM, Cox and Logistic regression | 15 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 15 | 60 | + |

| 44 | Cam et al50 | USA | Retrospective cohort | KM, Cox and Logistic regression | 13.5 | 15 | 10 | 10 | 12.5 | 61 | + |

| 45 | Pai et al51 | USA | Retrospective cohort | KM, Cox and Logistic regression | 15 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 15 | 60 | + |

KM, Kaplan Meier.

Data synthesis

Hospitalisations or rehospitalisations for heart failure and mortality identified by multivariable analysis in individual studies are presented (table 2), including their estimated effect size (eg, OR or HR) and 95% CI. Quantitative analysis of results was not done due to important heterogeneity in study design, study population, PH definition and measurement, outcome definitions in the studies and confounding or other types of prognostic factors. We have therefore presented a narrative summary of the available evidence (table 2).

Table 2.

Study characteristics of studies on mortality and readmissions for heart failure in patients with pulmonary hypertension associated with left heart disease

| Author, year published | Diagnostic criteria (RVSP by echocardiography or mPAP by echocardiography or RHC) | Study population (sample size, heart disease, NYHA class, type of HF) | Mean/median follow-up (months) | Age—years/male sex—% | Definition of outcomes predicted | Proportion (%) of measurable RVSP | Median/mean (mm Hg) baseline RVSP (echo) or mPAP (RHC) | Prevalence of PH at baseline (%) | HF readmission rate or adjusted ORs/HRs and CI | Mortality (all-cause) rate at 6, 12, 24 and 36 months or at mean duration of follow-up |

Adjusted ORs/HRs and CI (or p value) for all-cause mortality, outcome | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 6 | 12 | 24 | 36 or at mean/median follow-up | |||||||||||

| Studies in patients with heart failure and cardiomyopathies | ||||||||||||||

| Merlos et al, 20139 | RVSP >35 mm Hg | 1210 consecutive patients with HF, stratified into normal (RVSP <35), mild (RVSP 36–45), moderate (RVSP 46–60) and severe PH (RVSP >60 mm Hg) | 12 | 72.6 54.1% |

All-cause mortality Cardiovascular deaths |

41.5 | 46 | 35.2 | NR | NR | 4.89/10 persons-year in severe PH | NA | NR | OR for mild PH 1.6 (0.7 to 3.74), moderate PH 1.34 (0.54 to 3.16) and severe PH 2.57 (1.07 to 6.27) |

| Agawal et al, 201210 | RHC with mPAP >25 mm Hg | 339 patients with PH and LHD, 90% with HFpEF, NYHA class NR | 54.2 | 63 / 21% | All-cause mortality | NA | 43 | NA | NR | NR | 2.9% | 4.4% | 6.8% | UTSW cohort HR 1.4 (1.1 to 1.9) and NU cohort HR 1.4 (1.1 to 1.7) |

| Agawal, 201211 | RVSP >35 | 288 patients undergoing haemodialysis stratified into PH and NPH- based on RVSP | 25.8 | 56.5 vs 53.1 / 65 vs 63% | All-cause mortality | NA | 44.7 vs 27.2 | 38 | NR | NR | 26.4 vs 24.5 | 48.3 vs 46.3 | 62.9 vs 56.3 | HR 2.17 (1.31 to 3.61) |

| Aronson et al, 201112 | RHC with mPAP ≥25 mm Hg and mPCWP >15 mm Hg | 242 patients with acute HF, divided in 3 groups, NPH, passive PH and reactive PH, NYHA class IV | 6 | 61; 42% | All-cause mortality | NA | 34 vs 38 vs 44 | 76.0 | NR | 8.6 vs 21 vs 48.3 | NR | NR | NR | HR for passive PH 1.7 (0.6 to 4.5) and reactive PH 4.8 (2.1 to 17.5) |

| Bursi et al, 201213 | RVSP >35 mm Hg | 1049 patients with HF stratified into tertiles of RVSP (<41, 41–54 and >54 mm Hg) | 81 | 76; 49.3% | All-cause mortality | NR | 48 | 79 | NA | NR | 4, 10, and 17% for tertiles 1, 2, and 3, respectively | 8 vs 19 vs 28 | 46 | HR for tertile 2: 1.45 (1.13 to 1.85) and tertile 3: 2.07 (1.62 to 2.64) |

| Strange et al, 201214 | RVSP >40 mm Hg | 15633 echo screening, 636 PH group 2 stratified into 3 groups (group 1 RVSP <40 mm Hg, group 2 between 41 and 60 and group 3 >60 mm Hg) | 83 | 79; 48% | All-cause mortality | NR | 52 | NR | NA | NR | NR | NR | Mean survival 4.2 years | NR |

| Mutlak et al, 201215 | RVSP >35 mm Hg | 1054 patients with acute myocardial infarction divided into NPH and PH groups | 12 | 60 vs 69; 77 vs 64% |

Readmission for HF All-cause mortality |

NR | 32 vs 43 | 44.6 | 2.1 vs 9.2; OR 3.1 (1.87 to 5.14) | NR | NR | NR | NR | HR for readmission 3.1 (1.87 to 5.14) |

| Tatebe et al, 201216 | RHC with mPAP ≥25 mm Hg mPCWP >15 mm Hg | 676 consecutive patients with chronic HF, NYHA class ≥2, stratified into 3 groups, NPH (mPAP <25), passive PH (PH with PVR ≥2.5 WU) or reactive PH (PH with PVR >2.5 WU) | 31.2 | 64vs 64vs 63; 63vs 48vs 66% |

All-cause mortality and readmission for HF | NR | 17 vs 30 vs 35 in NPH, passive PH and reactive PH, respectively | 23 | NR | NR | 24.5 vs 18 vs 18.9% in NPH, passive and reactive PH, respectively | 52.5 vs 50 vs 60.3% in NPH, passive and reactive PH, respectively | 71.0 vs 77 vs 79.3 in NPH, passive PH and reactive PH, respectively | HR for reactive PH group 1.18 (1.03 to 1.35) |

| Adhyapak, 20108 | Echocardiography with mPAP >25 mm Hg | 147 patients with HF stratified into: group 1, normal PASP/preserved RV function; group 2, normal PASP/RV dysfunction; group 3, high PASP/preserved RV function; and group 4, high PASP/RV dysfunction |

11.2 | 54 91.8% |

Cardiac death Readmissions |

NR | Group 1 20±5 group 2 24.8±0.4 group 3 56.8±6 and group 4 58.9±8.8 | 53.7 | 19.7, OR and CI NR | Overall 5.1 at 11.2 months, 4.5 in group 3 vs 8.8 in group 4 | NA | NA | HR in PH 2.27 (1.09 to 3.57) | |

| Stern et al, 200717 | Echocardiography but criteria for PH not reported | 68 patients needing cardiac resynchronisation stratified into group 1 (RVSP ≥ 50 mm Hg, n=27) and group 2 (RVSP <50 mm Hg, n=41) | 7.1 | 70 64.7% |

Composite of hospitalisation for HF and all-cause mortality | NR | Group 1 39.7±6.7 and group 2 60.2±9.2 | NR | NR | NR | Increased mortality in patients with RVSP ≥50 mm Hg | NR | NR | HR of 2.0 (1.2 to 5.5) for RVSP ≥50 |

| Lee et al, 201018 | RVSP >39 mm Hg | 813 patients with TR stratified into two groups based on the RVSP <39 mm Hg (group 1, n=530) and RVSP ≥39 mm Hg (group 2, n=283) | 58.8 | 64 42.5% |

All-cause mortality | NR | 37.1 in patients who survived vs 43.8 in patients who died | NR | NR | NR | NR | 10.5 vs 21.9 | 5-year survival rates 61.0 and 80.6% group 2 vs group 1 respectively |

HR of 1.024 (1.017 to 1.032) |

| Møller et al, 200519 | RVSP >30 mm Hg | 536 patients with acute myocardial infarction stratified into group 1 (RVSP <30 mm Hg), group 2 mild to moderate PH (RVSP of 31 to 55 mm Hg) and group 3 severe PH (RVSP >55 mm Hg) | 40 | 65/ 68% 74/54% 78/44% in groups 1, 2 and 3, respectively |

All-cause mortality | 69 | NR | 75 | NR | NR | NR | 5% in group 1 52% in patients with a RVSP >65 mm Hg |

NR | HR 1.22 (1.14 to 1.38) per 10 mm Hg increased |

| Cappola et al, 201220 | RHC with mPAP ≥25 mm Hg | 1134 patients with cardiomyopathy stratified according to PVR: NPH (<2.5), group 1 PH (2.5–3), group 2 PH (3–3.5), group 3 PH(3.5–4) and group 4 PH (>4) | 52.8 | 48 60% |

All-cause mortality | NA | 25 | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | 33% of patients died during the mean FU | HR 1.86 (1.30 to 2.65) for group 2, 1.78 (1.13 to 2.81) for group 3 and 2.04 (1.51 to 2.74) for group 4 |

| Szwejkowski et al, 201121 | RVSP >33 mm Hg | 1612 patients with HF stratified into 5 groups according to RVSP (<33; 33–38; 39–44; 45–52 and >52 mm Hg) | 33.6 | 75.2 57.4% |

All-cause mortality | 32 | 46 | 83.3 | NR | NR | NR | NR | 55.1% of patients died during the mean FU | HR 1.06 (1.03 to 1.08) for every 5 mm Hg increase in RVSP |

| Abramson et al, 199222 | Echocardiography with TRV >2.5 m/s | 108 patients with dilated cardiomyopathy, stratified into 2 groups: group 1 (TRV <2.5 m/s) and group 2 (>2.5 m/s), 38.9% in NYHA class III and IV, 77.3% of ischaemic HF | 28 | 67.5 81% |

All-cause mortality, mortality due to HF and re-hospitalisations for HF | NR | 5.6 m/s | 26 | 75% during the study period 5.76 (1.97 to 16.90) |

NR | NR | NR | 17% in 28 months vs 57% | OR for increased TRV 3.77 (1.38 to 10.24) |

| Kjaergaard et al, 200723 | Echocardiography but cut-off for PH not reported | 388 consecutive patients with known or presumed HF stratified into quartiles of RVSP (<31, 31–38, 39–50, >50) | 33.6 | 75 60% |

All-cause mortality | NR | 38 | 75% and 50% with RVSP >31 and 40 mm Hg, respectively | NR | 48% if COPD and 21% in HF without COPD | NR | 57% at 33.6 months | HR 1.09 (1.04 to 1.14) for every increase of RVSP per 5 mm Hg | |

| Shalaby et al, 200824 | RVSP ≥30 mm Hg | 270 patients undergoing cardiac resynchronisation stratified into 3 groups on the basis of RVSP: group 1, (22–29, n=86); group 2 (30–44, n=90) and group 3 (45–88, n=94). | 19.4 | 66.5 91% |

All-cause mortality, cardiac transplantation (primary end point) or re-hospitalisation for HF | NR | 40.4 | NR | 40% in group 3 vs 9% in group 1 (6.35 (2.55 to 15.79)) | NR | NR | NR | 12% in group 1% vs 34% in group 3 at mean follow-up | HR 2.62 (1.07 to 6.41) |

| Damy et al, 201025 | Echocardiography with RVTG >25 mm Hg | 1380 patients with congestive HF, 1026 with LVSD (EF <45%) and 324 without), further stratified into quartiles of RVSP | 66 | 72 67% |

All-cause mortality | 30% of all, 26% in patients with LVSD and 40% in those without | 25 | 46% of HFpEF,50% of HFrEF and 23% of patients without HF | NA (outpatient cohort) | NR | NR | NR | 40.3% at median follow-up of 66 months | HR 1.72 (1.16 to 2.55) for RVSP >45 mm Hg) |

| Ristow et al, 200726 | Echocardiography with TR gradient >30 mm Hg | 717 patients with coronary artery disease, 573 with measurable TR, stratified into group 1 (TR gradient ≤30 mm Hg, n=447) and group 2 (TR gradient >30 mm Hg, n=126) | 36 | 65, 74% (group 1) 69, 75% (group 2) |

Hospitalisation, CV death, all-cause death and the combined end point of all | 80 | NR | 22 | 6% (group I) vs 21% (group II) OR per each 10 mm Hg increase of TR gradient 1.5 (1.03 to 2.2) | NR | NR | NR | 11% (group 1) vs 17% (group 2) | OR for all-cause deaths 1.2 (0.85 to 1.6) per 10 mm Hg increase in TR OR for combined endpoint 1.6 (1.1 to 2.4) |

| Grigioni et al, 200627 | RHC with mPAP ≥25 mm Hg | 196 patients with HF evaluated for PH and changes in mPAP | 24 | 54 73% |

Cardiovascular deaths, acute HF and combined end point of both | NA | 25 | NR | 27% acute HF, 2.30 (1.42 to 3.73) | NR | NR | 20% cardiovascular deaths | NR | HR for PH 2.3 (1.42 to 3.73) ; HR for worsening >30% in mPAP 2.6 (1.45 to 4.67) |

| Levine et al, 199628 | RHC assessed change in PH, no definition | 60 patients with PH owing to HF awaiting heart transplantation, stratified into 2 groups: group A (persistent elevated sPAP, n=31), group B (decrease in sPAP, n=29) | 10 | 50 85% |

Transplant or all-cause death | NA | 39 vs 57 in group A and group B, respectively | NA | NR | NR | NR | NR | 90% vs 50% of death at 10months in group A and group B, respectively | NR |

| Lam al, 201029 | RVSP >35 mm Hg | 244 patients with HFpEF compared with 719 subjects with HTN. 203 patients with HFpEF and PH later stratified into: group 1 (RVSP <48 mm Hg) and group 2 (RVSP >48 mm Hg) | 33.6 | 74/47% vs 79*/41% in group 1 and group 2, respectively | All-cause mortality | 65 vs 83% in HTN and HFpEF, respectively | 28 vs 48 mm Hg in HTN and HFpEF, respectively | 8 vs 83% in HTN and HFpEF, respectively | NR | NR | 12.2 vs 25.7 in group 1 and group 2, respectively | 18.4 vs 36.2 in group 1 and group 2, respectively | 55.1 vs 63.8 in group 1 and group 2, respectively | HR 1.20 per each increase of 10 mm Hg in RVSP (p<0.001) |

| Kush et al, 200930 | RHC with mixed PH (MPH) defined as mPAP ≥25 mm Hg, PCWP >15 mm Hg, and PVR ≥3 WU | 171 patients with severe HFrEF (NYHA class IV, LVEF ≤30%,systolic BP ≤125 mm Hg) further stratified into 2 groups: MPH group (mPAP >25 mm Hg and PVR >3 WU, n=80) and non-MPH (mPAP <25 mm Hg or PVR <3WU, n=91) | 6 | 59/75% vs 54*/71% in MPH and non-MPH, respectively | Rehospitalisations and all-cause mortality | NA | mPAP: 42 vs 32 in MPH and non-MPH, respectively TPG:17 vs 7, respectively |

47 | HR for MPH 0.8 (0.59 to 1.08) | 21 vs 22 | NR | NR | NR | HR for MPH 0.89 (0.66 to 1.20) |

| Ghio et al, 200131 | RHC with mPAP ≥20 mm Hg, RV systolic dysfunction defined as RVEF <35% |

377 patients with HF stratified into: group 1, normal mPAP/preserved RVEF (n=73); group 2 normal mPAP/low RVEF (n=68); group 3, high PAP/preserved RVEF (n=21); and group 4, high PAP/low RVEF (n=215) | 17.2 | 51 85.7% |

Heart transplantation and all-cause mortality | NA | 27.9 | 62.3 | NR | NR | NR | NR | 7.3 vs 12.3 vs 23.8 vs 40 in groups 1, 2, 3 and 4,* respectively | HR 1.1 (1.0 to 1.21) per each 5-mm Hg increment |

| Wang et al, 201032 | RVSP >30 mm Hg | 93 patients with HF undergoing cardiac resynchronisation stratified into group 1 (RVSP >50 mmH, n=29); group 2 (30 <RVSP ≤50 mm Hg, n=17) and group 3 (RVSP ≤30 mm Hg, n=47) | 32 (6 to 60) | 59.6 81.7% |

All-cause mortality, HF mortality | NR | NR | 49.5 | NR | 28 vs 6 vs 17% in groups 1,2 and 3, respectively | NR | NR | NR | Non-significant increased in all-cause mortality (p=0.33), increase in HF mortality but OR/HR not reported |

| Ghio et al, 201333 | RVSP >40 mm Hg and RV dysfunction defined as TAPSE <14 mm | 658 patients with chronic HF stratified into group 1 (no PH no RVD, n=256), group 2 (RVD, no PH, n=54), group 3 (PH, no RVD, n=167), and group 4 (RVD and PH, n=67) | 38 | 63 86% |

All-cause mortality, urgent cardiac transplantation or ventricular fibrillation |

83 | 38 | 35.6 | NR | 17.5% in PH vs 4.5% in non-PH | 21.4% in PH vs 8.7% in non-PH | 42.3% in PH vs 20.3% in non-PH | 59.4% in PH vs 45.2% in non-PH | HR 1.90 (2.18 to 3.06) for group 3 and 4.27 (3.45 to 7.43) for group 4 |

| Studies in patients with heart valve disease | ||||||||||||||

| Fawzy et al, 200435 | Severe PH defined as RVSP >50 mm Hg | 559 patients with MS undergoing MBV stratified into three groups: group A (RVSP <50 mm Hg; n=345); group B (RVSP 50–79 mm Hg; n=183) and group C (RVSP ≥80 mm Hg; n=31) | 63.6 | 31/28.1% vs 30/25.1% vs 27/16.1% in groups A, B and C, respectively | Reversibility of PH following MBV | NR | 38.5 vs 59 vs 97.8 in groups A, B and C, respectively | 62% vs 33% vs 5% for groups A, B, and C, respectively | NR | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | No mortality was encountered, PH normalised over a 6 to 12 months |

| Naidoo et al, 199134 | RHC with PASP ≥30 mm Hg | 139 patients with AR (69 undergoing AVS) stratified into group 1 (normal or mild PH) and group 2 (moderate PH or marked PH) | 6 | 32.9 vs 36.2 and 69.7 vs 77.8 in group 1 and 2, respectively | Immediate and 6 months postoperative mortality | NA | 18 vs 43.7 in group 1 and 2, respectively | 63.3 | NR | 3 in group 1 vs 2.8% in group 2 | NR | NR | NR | No increased in mortality, HR not reported |

| Manners et al, 197741 | RHC with PASP >70 mm Hg | 392 patients who had undergone prosthetic valve surgery stratified into 2 PASP <70 mm Hg, n=336 or PASP >70 mm Hg, n=56) | 48 | NR | Hospital mortality | NA | Mean PASP was 93 mm Hg | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | 5.4% at 4 years in both PH and non-PH | NR |

| Roseli et al, 200236 | RVSP >35 mm Hg | 2385 patients undergoing AVR stratified into 3 groups: RVSP <35 mm Hg n=611; RVSP 35–50 mm Hg, n=1199; RVSP >50 mm Hg, n=575 | 51.6 | 74 55% |

All-cause hospital and late mortality | NR | 41 | 74 | NR | 15.8 vs 19.7 vs 25.9 | NR | NR | NR | Higher RVSP was predictor of 5 and 10 years mortality, HR not reported |

| Melby et al, 201137 | RVSP >35 mm Hg | 1080 patients with AS undergoing AVR, stratified into NPH, (RVSP <35 mm Hg, n=574) and PH group(mild PH, moderate and severe PH) | 48 | 72.3 vs 70.2 59.1 vs 57.8% in PH and non PH, respectively |

All-cause operative and long-term mortality | NR | 51 in PH group | 46.8 | NR | NR | 17.1 vs 17.6 vs 17.1 vs 23.5 for non-PH, mild, moderate and severe PH, respectively | 25.7 vs 24 vs 23.2 vs 32.3 | 25.7 vs 38.4 vs 52.7 vs 46.1 | OR 1.51 (1.16 to 1.96), persistent PH after AVR was associated with decreased survival |

| Le Tourneau et al, 201038 | RVSP ≥50 mm Hg | 256 patients with MR undergoing MVO, stratified into group 1 (RVSP <50 mm Hg, n=174) and group 2 (RVSP ≥50 mm Hg, n=82) | 49.2 | 63 66% |

All-cause mortality Cardiovascular deaths |

NR | 45±14 | 32% had RVSP ≥50 mm Hg | NR | NR | NR | 31.6 vs 31.7 in groups 1 and 2, respectively | NR | HR 1.43 (1.09 to 1.88) per 10 mm Hg increment of RVSP |

| Parker et al, 20107 | RVSP >35 mm Hg | 1156 patients with MR or AR stratified into normal (RVSP <30 mm Hg), borderline (31–34 mm Hg), mild (35–40 mm Hg) or moderate or greater (>40 mm Hg) | 87.6 | 72 51% |

All-cause mortality | 52 | 29 | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | HR for moderate or greater PH 1.95 (1.58 to 2.41) in AR and 1.48 (1.26 to 1.75) in MR |

| Barbieri et al, 201040 | RVSP >50 mm Hg | 437 patients with MR, 35% NYHA class III or IV, normal LVEF, stratified into NPH (RVSP ≤50 mm Hg) and PH (RVSP >50 mm Hg) | 57.6 | 67 66% |

All-cause mortality, cardiovascular death, heart failure | 45 | 23 | 1.70 (1.10 to 2.62) and 1.19 (1.06 to 1.35) for each 10 mm Hg increase of RVSP | NR | NR | 23% at the mean follow-up | HR 2.03 (1.30 to 3.18) and 1.16 (1.03 to 1.31) for each 10 mm Hg increase of RVSP | ||

| Kainuma et al, 201139 | Echocardiography, PH definition not specified | 46 patients undergoing MVR, NYHA III or IV, LVEF <40%, stratified into group 1 (RVSP <40 mm Hg, n=19), group 2 (moderate PH (40 <RVSP <60, n=17) and group 3 (RVSP >60, n=10) | 36 | 64 35% |

Cardiac death, myocardial infarction, endocarditis, thromboembolism, reoperation for recurrent MR, readmission for heart failure and fatal arrhythmia |

NR | 47 | NR | 30% in the severe PH but not significant, OR and CI NR | NR | 15.8 vs 11.8 vs 20% for groups 1, 2, and 3, respectively | 31.6 vs 29.4 vs 30% | 47.4 vs 82.4 vs 50% | HR for all adverse cardiac events 6.9 (1.1 to 44) in group 3 |

| Khandhar et al, 200943 | Severe PH defined as RVSP >60 mm Hg | 506 patients with severe AR stratified into group 1, severe PH with RVSP >60 mm Hg, n=83 and group 2 (RVSP <60, n=423), NYHA NR | NR | 63 47% |

All-cause mortality | 100 | NR | 16% of severe PH | NR | NR | NR | 21.6 of patients with severe PH | NR | PH was associated with increased mortality in all groups, OR and CI NR |

| Malouf et al, 200242 | Severe PH defined as peak TRV ≥4 m/s | 3171 patients with AS of whom 47 with severe PH, stratified into group 1 (no AVR, n=10) and group 2 (AVR, n=37), 79% in NYHA III and IV | 15.3 | 78 47% |

All-cause mortality | 63% of the 3171 total population of patients with aortic stenosis | 4.16 m/s | NA | NR | NR | NR | NR | 80% vs 32% in groups 1 and 2, respectively, at median FU | OR for mortality risk in severe PH and AVS 1.76 (0.81 to 3.35) |

| Zuern et al, 201244 | RVSP >30 mm Hg | 200 patients with AS undergoing AVR stratified into NPH (RVSP <30) vs mild-to-moderate PH (30 <RVSP <60) and severe PH (>60 mm Hg) | 31.2 | 72.3 52.5% |

All-cause mortality | NR | 36.3 | 61 | NR | NR | 10.2 vs 14.1 vs 30.4 | 30.7 vs 40.4 vs 60.1 | 2.6, 15.2 and 26.1% | HR for mild-to-moderate PH 4.9 (1.1 to 21.8) and severe PH 3.3 (0.6 to 19.7) |

| Ben-Dor et al, 201145 | RVSP >40 mm Hg | 509 patients with AS divided into group 1 (RVSP <40 mm Hg, n=161); group 2 (RVSP 40–59, n=175) and group 3 (RVSP >60 mm Hg, n=173) | 6.73 | 82.3 vs 82.4 vs 80.5 in groups 1, 2 and 3, respectively, >75% |

All-cause mortality | NR | 33.7 vs 49.3 vs 70.7 in groups 1, 2, and 3, respectively |

68.3 | NR | NR | NR | NR | 21.7 vs 39.3 vs 49.1 in groups 1, 2 and 3, respectively at median FU* | PH was significantly associated with increase in mortality, OR/HR not reported |

| Yang et al, 201246 |

RVSP >40 mm Hg | 845 patients who underwent valve surgery and/or CABG (444 without PH or NPH vs 401 PH), all with LVEF <40% | 39 | 65.2 vs 67.8 78.8 vs 72.6% in NPH and PH group, respectively |

Postoperative complications and mortality | NR | NR | NR | NR | 4.6 vs 13.9 in NPH vs PH group, respectively | NR |

16.7 vs 30.6* in NPH vs PH group, respectively | OR for mild/moderate PH 1.475 (1.119 to 1.943) | |

| Nozohoor et al, 201247 | RVSP >50 mm Hg | 270 patients with MR undergoing MVS, stratified into NPH group (RVSP <50 mm Hg) and PH group (RVSP ≥50 mm Hg) | 61.2 | 61.5 vs 66.5 70 vs 54% in no PH and PH group, respectively |

Perioperative complications and all-cause late mortality | NR | NR | 27 | NR | NR | 7.6 vs 8.2 in no PH and PH, respectively | 22.4 vs 17.6 in no PH and PH, respectively | 31.1 in both groups | HR 4.3 (1.1 to 17.4) during the initial 3 years after MVS |

| Ward and Hancock 197548 | RHC with extreme PH defined as SPAP >80 mm Hg and PVR >10 WU: 8.2% | Mitral valve disease (n=586), 48 extreme PH stratified into group 1 (no operation), group 2 (all surgical) and group 3 (survive after surgery) | 69.6 | 46.2 vs 42.4 43 vs 29% in group 1 and 2 respectively |

All-cause mortality | NA | 105 vs 96.6 | 8.2 | NA | NR | NR | NR | NR | Extreme PH was associated with higher mortality, and surgery improved survival |

| Ghoreishi et al, 201249 |

sPAP >40 mm Hg using RHC in 591 patients and RVSP >40 mm Hg using DE | 873 patients with MR who underwent MVS, stratified into NPH and PH group (mild, moderate, severe) NHYA not reported | 35 | 59 59% |

Hospital mortality, Late all-cause mortality |

NR | 46 (echo), and sPAP was 43 by RHC | 53 | NR | NR | 16.2 in non PH vs 32% in PH group* | 33.9 in non PH vs 48.1% in PH group* | 51.8 in non PH vs 60.9% in PH group* | HR 1.018 (1.007 to 1.028) per each 1 mm Hg increment in RVSP |

| Cam A et al, 201150 | RHC with severe PH defined as mPAP >35 mm Hg | 317 patients with AS, 35 with severe PH underwent surgery and were compared to 114 mild moderate PH and to 46 severe PH treated conservatively, NHYA not reported | 11.3 | 71/53.5 (mild-moderate PH) vs 75/51.4 (severe PH) | All-cause mortality | NA | 22.5 (mild-moderate PH) vs 45.3 (severe PH) | 47.0 | NR | NR | NR | NR | 74.5 vs 75.5 | HR 1.008 (0.9 to 1.11) and early postoperative reduction in mPAP 0.93 (1.2 to 12.5) |

| Pai et al, 200751 | Severe PH defined as RVSP >60 mm Hg | 116 patients (of 740 severe AS) with severe PH among which 36 underwent AVR and were compare to 83 remaining | 18 | 75 39% |

All-cause mortality | NR | 69 | 15.7% (severe PH) | NR | NR | NR | 30.5 (PH) vs 15.5 (NPH) | NR | AVR benefit HR 0.28 (0.16 to 0.51) independent of PH |

*p<0.05.

AS(R), aortic stenosis (regurgitation); AVS(R), aortic valve surgery (replacement); CABG, coronary artery bypass graft; DE, Doppler echocardiography; eSPAP, estimated systolic pulmonary artery pressure; HFpEF, heart failure (HF) and preserved ejection fraction; LHD, left heart disease; LVEF, left ventricular (LV) ejection fraction; MBV, Mitral Balloon Valvotomy; mPAP, mean pulmonary arterial pressure; mPCWP, mean pulmonary capillary wedge pressure; MV(R/O), mitral valve (repair/operation); NA, not applicable; NPH, non-pulmonary hypertension; NR, not reported; PH, pulmonary hypertension; PVR, pulmonary vascular resistance; RV(SP/TG), right ventricular systolic pressure/tricuspid gradient); TPG, transpulmonary gradient; TRV, tricuspid regurgitation (TR) velocity(TRV); TAPSE, tricuspid annular plan systolic excursion; UTSW, University of Texas—Southwestern; WU, wood units.

Results

Studies selection

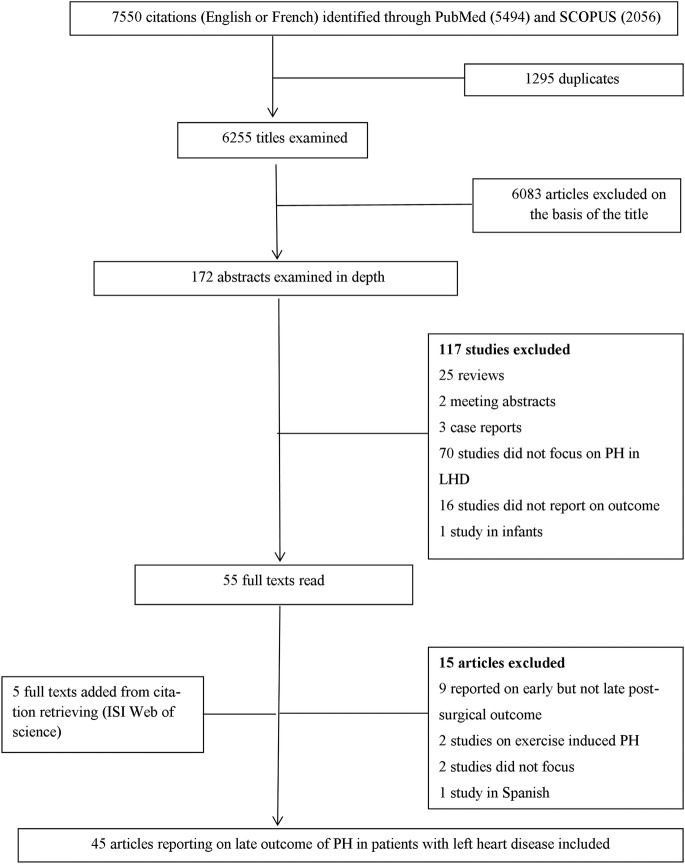

Figure 1 presents a flow diagram for the study selection process. Of the 7550 citations identified through searches, 6255 titles were examined and 6083 were excluded on the basis of the title scanning. The remaining 172 abstracts were examined and 55 articles were screened by full text of which 15 were excluded for various reasons (figure 1). Five studies were identified via citation search. Therefore, 45 articles were included in the final review among which 86.7% were published between 2003 and 2013 (see online supplementary figure S1).

Figure 1.

Flow diagram of literature search process. LHD, left heart disease; PH, pulmonary hypertension.

Study characteristics and methodological quality

The characteristics and methodological quality of the 45 included studies are described in table 1. The overall quality score ranged from 29.5 to 72.5 points with a median of 63.5. Based on the cut-offs of ≥60 and ≥45 points, respectively, we classified 34 articles as being of high quality, 7 as moderate-to-high quality and four as low-quality studies (table 1). Studies of high quality were recent and scored well on patient selection, outcome measurement, statistical analysis and presentation. Studies classified as moderate/low quality scored relatively well on patient selection, but poorly on study attrition, statistical analysis and presentation. Twenty-four (53.3%) studies were from the USA, 12 (26.6%) from Europe (four from UK, three from Italy and one each from Spain, Germany, Denmark, France and Sweden), 6 (13.3%) from Asia (two from Japan, one each from India, China, Korea and Australia) and 1 from South Africa. One study was multicentric across Europe and the USA40 and another one was multicentric across the USA and Canada.30 Only three population-based cohorts were reported including two prospective13 29 and one retrospective study.14 For the remaining 42 hospital-based cohort studies, 20 had a retrospective design. The number of participants ranged from 46 to 2385 in hospital-based and from 244 to 1049 in population-based studies. The proportion of men ranged from 21% to 91%, and mean/median age from 63 to 82 years. Twenty-six studies were in patients with heart failure (HF) and cardiomyopathies (two in heart failure with preserved ejection fraction (HFpEF)) and 19 in patients with valve disease.

Twelve studies defined PH using RHC and 32 studies using DE. One study defined PH using both RHC and DE. Studies applied variable definitions of PH using both RHC (based on mPAP >25 or 30 mm Hg, or on systolic pulmonary artery pressure (sPAP) >50 mm Hg, or sPAP >40 mm Hg, or on pulmonary vascular resistance (PVR) >2.5 wood units (WU)) and DE (based on RVSP with cut-offs varying from 35 to 50 mm Hg, or based on a mPAP >25 mm Hg8 or on a right ventricular tricuspid gradient (RVTG) >25 mm Hg).25 Prevalence of PH in HF ranged from 22% to 83.3% overall, 22–83.3% in studies of PH based on DE and 23–76% in studies of PH based on RHC (see online supplementary figure S2).

Outcome of PH

Admissions for heart failure

The duration of follow-up ranged from 6 to 87.6 months overall, 6–69.6 months in studies of PH based on RHC definition and 6–87.6 months in studies of PH based on DE definition. Readmission rates, when reported, ranged from 9.2% to 75% overall and 9.2–75% in studies of PH based on DE definition. Only one study with PH definition based on RHC reported a readmission rate of 27% (table 2). Admissions or readmissions for HF were reported in nine studies all based on DE definition among which seven reported HRs or ORs for admission/readmission in relation with PH. Effect estimates for six of the seven studies were statistically significant.

Mortality

Mortality was reported in all studies (table 2); however, not all studies provided multivariable-adjusted effect estimates of mortality risk associated with PH. PH was associated with increased all-cause mortality in 24 of 26 studies of HF, among which 6 studies were of PH based on RHC definition, while two studies failed to report an association between PH and all-cause mortality at 6 months. Of these two studies, one used PH definition based on RHC and was a multicentric trial of HF that reported effect estimates for mortality risk from PH (HR=0.89 (95% CI 0.66 to 1.20));30 while the other one32 did not. When reported, mortality rates at 12 months ranged from 0% to 32% overall, 0% to 32% in studies of PH based on DE and 2.9% to 18% in studies of PH based on RHC (see online supplementary figure S3). As summarised in table 3, over 35 potential predictors of mortality were tested across studies with variable and often inconsistent effects on the outcome of interest. Age was associated with mortality in 14 studies (among which 11 studies of PH were based on DE), male gender in 3/11 studies (all based on DE), LVEF in 6/10 studies, right ventricular (RV) function in 3/3 studies and renal disease (rising creatinine, decreasing glomerular filtration rate (GFR) or dialysis) in 6/17 studies (all based on DE), functional class (New York Heart Association (NYHA) or WHO) in 7/12 studies (five based on DE) while the 6 min walking distance was tested in only one study but was not integrated in the multivariable analysis for outcome risk.32

Table 3.

Other prognostic factors associated with mortality in patients with pulmonary hypertension associated with left heart disease

| Factor | Number of studies reporting |

Number of studies in which the factor was associated with poor outcome |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| overall | Studies based on DE | Studies of PH based on DE | Studies of PH based on RHC | |

| Age | 14 | 11 | 11 | 3 |

| Sex (male vs female) | 11 | 9 | 3 | 0 |

| Racial/ethnic group | 2 | 2 | 0 | 0 |

| HF episodes | 5 | 5 | 2 | 0 |

| Prior hypertension | 5 | 5 | 1 | 0 |

| History of diabetes | 8 | 8 | 3 | 0 |

| Smoking | 3 | 3 | 0 | 0 |

| History of cardiovascular disease | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| Functional class (NYHA/WHO) | 12 | 9 | 5 | 2 |

| Killip class for MI | 2 | 2 | 2 | 0 |

| Heart rate | 2 | 2 | 0 | 0 |

| Systolic BP | 4 | 4 | 2 | 0 |

| Diastolic BP | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| Mean BP | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| SPO2 | 3 | 3 | 1 | 0 |

| Hypotension | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| Atrial fibrillation | 5 | 5 | 5 | 0 |

| Ischaemic aetiology of HF | 4 | 4 | 0 | 0 |

| Urea | 2 | 2 | 1 | 0 |

| Kidney disease (by creatinine, GFR or haemodialysis) | 17 | 14 | 6 | 0 |

| BNP | 3 | 3 | 2 | 0 |

| Haemoglobin | 2 | 2 | 0 | 0 |

| Presence of COPD | 4 | 3 | 3 | 0 |

| Use of medications (ACEI and or beta blockers or spironolactone) | 6 | 6 | 3 | 0 |

| LVEF | 10 | 10 | 6 | NA |

| LV end-diastolic diameter/index | 6 | 6 | 3 | NA |

| Atrial diameter | 1 | 1 | 1 | NA |

| Deceleration time | 1 | 1 | 0 | NA |

| RV function (by TAPSE or other means) | 3 | 3 | 3 | NA |

| Functional mitral regurgitation | 5 | 5 | 4 | NA |

| RVSP ≥50 or >60 mm Hg | 9 | 9 | 5 | NA |

| End diastolic pulmonary regurgitation | 1 | 1 | 1 | NA |

ACEI, ACE inhibitors; BNP, brain natriuretic peptide; BP, blood pressure; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; GFR, glomerular filtration rate; HF, heart failure; LVEF, left ventricular ejection fraction; MI, myocardial infarction; NYHA, New York Heart Association; RHC, right heart catheterisation; RVSP, right ventricular systolic pressure; RV, right ventricle; TAPSE, tricuspid annular plan systolic excursion.

Discussion

An increasing number of studies have assessed the risk of readmission and mortality in patients with LHD-related PH over the last decade, and mostly in North America and Europe. Available studies are mostly consistent on the adverse effect of PH (whether assessed using DE or RHC) on mortality risk in patients with heart failure as well as those with mitral valve disease, but less unanimous in those with aortic valve disease. The consistent adverse effect of PH in this population highlights the importance of early diagnosis of PH to reduce mortality. While available studies have been overall of acceptable quality, substantial heterogeneity in the study population, PH definition and measurement, outcome definitions as well as other prognostic factors limit direct comparisons across studies. Information on readmission for heart failure was limited and the assessment of other prognostic factors in an integrated multivariable model was very heterogeneous.

Mortality in patients with PH and heart failure with reduced ejection fraction

While PH was an independent prognostic factor for mortality in fatal-outcome studies, the prevalence of PH and effects on mortality varied according to LVEF. Differences in the prevalence of PH could be explained at least in part by population heterogeneity (age, level of HF, HF centres or community study) and differences in the criteria used to define PH across studies with a variety of cut-off values. Regardless of the prevalence of PH in HFrEF, there seems to be no uniformity in the association between the magnitude of reduction in LVEF, and the presence or absence of PH and the effects of PH on mortality risk. It is possible that the small size of studies and the short duration of follow-up precluded the accumulation of a substantial number of events to allow the detection of a relationship, if any. Furthermore, although the precise haemodynamic threshold beyond which RVSP is invariably associated with mortality is subject to debate; the risk of death associated with PH seems to increase with higher RVSP.6 12 13 16 A possible pathophysiological explanation is that early and higher vascular remodelling occurs in patients with HF and severe PH, causing a reactive or ‘postcapillary PH with a precapillary component’, which in turn has a greater impact on the RV function. Equally, RV systolic function has been shown to be highly influenced by pressure overload and by vascular resistance in the pulmonary region50; and RV function assessed using RHC or echocardiography has been shown to be associated with mortality.30 31 33 It is, however, remarkable that one study30 reported no interaction between PH and RV function, with both variables being independently associated with mortality. This highlights the fact that RV function in HF does not only depend on pulmonary pressure but may also reflect intrinsic myocardial disease. As suggested by Vachiery et al6 there might be a spectrum of clinical phenotypes of RV failing in PH-LHD that might evolve from one to the other, from isolated postcapillary PH with little effect on the RV to more advanced disease where the failing RV is the key determinant of outcome.

Mortality in patients with PH and heart failure with preserved ejection fraction

Over the past decades, the increasing prevalence of HFpEF51 has been paralleled by an increasing presence of PH in patients with HFpEF.5 6 When compared to heart failure with reduced ejection fraction (HFrEF), patients with HFpEF have their subset of risk factors; but finally, PH conveys similar morbidity and mortality risk in the two subgroups of patients.13 17 The current incomplete understanding of HFpEF limits our ability to explain why these patients develop PH. However, it is estimated that over time left atrium and ventricular filling pressure from compromised left ventricle and, in some, left atrium relaxation and distensibility can lead to elevated pulmonary venous pressure, triggering vasoconstriction and arterial remodelling.4 5 In total, the finding of PH as an independent prognostic factor for mortality in patients with HF tends to support the suggestion that PH should be considered as a potential therapeutic target at least in the group of patients with HF who exhibit persisting PH after optimisation of HF therapy. In this line, targeting both pulmonary vasculature and the heart would probably be more beneficial.

Mortality in patients with PH related to valvular heart disease

PH due to valvular heart disease (VHD) was not always related to mortality risk,38 39 45 which is in contrast with PH in patients with heart failure. A simple explanation of this difference could be that the prevalence and severity of PH correlates with the severity and type of VHD. Although mitral stenosis (MS) has been the classical disease associated with PH-LHD and reactive PH was initially described in these patients4; it is, however, noticeable that PH due to MS has received little attention over the last decade, probably because of the progressive decline in RHD in Western countries. Interestingly, the two studies included showed that surgery was safe and improved survival in patients with PH due to MS35 48 with PH regressing to normal levels over 6–12 months after successful Mitral Balloon Valvotomy (MBV).35 In mitral regurgitation (MR), nearly all cohort studies on outcomes of severe PH reported increased mortality.38 39 40 46 49 The relevance of this finding is that PH can serve both as an indication for proceeding to surgical or catheter-based interventions, and also as an operative risk factor for mitral valve interventions.54 By contrast, PH is not as common in the aortic valve surgical cohort. Mortality rates in different studies of patients with VHD depends on comorbidities, exclusion criteria and definition for PH. Studies that also evaluated changes in PH following valve surgery showed a decline in pulmonary pressures following surgery.35 45 50 55 It is worth noting that the pathophysiology of the pulmonary vasculature in PH due to VHD is similar to that in patients with HF.1

Hospitalisations and other prognostic factors

The paucity of information on the effect of PH-LHD on hospitalisations or rehospitalisations as has been shown in this study highlights the need for more evidence on this outcome. Such information is important to fully characterise and quantify the contribution of PH-LHD to the global burden of disease, and assess future improvement from treating the underlying LHD and/or controlling PH in patients with LHD.

Of the 35 other potential prognostic factors of mortality in patients with PH that were tested in multivariable models across studies, investigations on echocardiographic parameters suggested that PH >60 mm Hg was associated with worse mortality in seven of the nine studies. Similarly, a greater degree of MR, deceleration time when reported26 and RV function were almost constantly associated with adverse outcome while LVEF was associated with adverse outcome in 6 of the 10 studies. In the evolution of LHD, RV dysfunction usually occurs as a turning point. It shall be noted that PH incorporates information on diastolic function, MR and pulmonary vascular disease, and this might explain the pivotal role of PH in gauging the prognosis of patients with HF.

Strengths and limitations of the studies included in the review

The first limitation of the studies included in our review is the possibility of study population bias. The majority of studies originated from Western countries and included predominantly Caucasians and reported mostly on PH-LHD in a population with high prevalence of ischaemic heart disease. This precludes the generalisability of our findings to developing countries where aetiologies of LHDs are less of ischaemic origin and are more dominated by systemic hypertension, dilated cardiomyopathies and RHD in a younger population.56 Therefore, PH-LHD may have a different prognosis in developing countries. Second, studies included in this review were defined PH based either on DE or RHC. RHC remains the gold standard to diagnose and confirm PH, but performing RHC on all patients with dyspnoea would bear excessive risks and be impractical in resource-limited settings. DE on the other hand is widely available, safe and relatively cheap for diagnosing PH, although the reproducibility of the approach in some circumstances has been questioned. However, a systematic review on the diagnostic accuracy of DE in PH by Janda et al57 has shown that the correlation of pulmonary artery systolic pressure by DE compared to RHC was good with a pooled correlation coefficient of 0.70 (95% CI 0.67 to 0.73). However, studies to date examining the prognostic impact of PH in LHD have been performed in heterogeneous populations, using variable definitions of PH based both on RHC and echocardiography parameters, thus limiting any possibility of pooling. Finally, readmissions were not frequently reported and multivariable analysis when performed was characterised by a great heterogeneity in the number and range of candidate predictors included in the models, thus limiting interpretation and generalisability. Therefore, findings on these other prognostic factors must be interpreted with caution. For studies that performed only univariate analysis, we cannot rule out the possibility that the reported factors may not preserve a significant association with the outcome once adjusted for the effect of other extraneous factors. In spite of these limitations, the majority of studies included were recent and all reported on the relation of PH-LHD with all-cause mortality, making the conclusions on this relation appropriate for contemporary Western populations.

Strengths and limitations of the review

First, by restricting our search strategy to full-report articles published in English and French, and in journals available in the used electronic databases, we cannot rule out the possibility of language or publication bias. Second, we used the QUIPS instrument, designed for prognosis studies, to address common sources of bias. The QUIPS, however, lacks discriminative power; we addressed this by using the scoring algorithm suggested by de Jonge et al.6 This scoring algorithm can still be subject to criticisms, especially because the cut-off points used to determine the quality of the studies are quite arbitrary. Third, because of important heterogeneity in the included studies, we were not able to pool data to perform a meta-analysis or to stratify data by clinically important subgroups (such as mild, moderate or severe PH). However, to the best of our knowledge, this is the first systematic review on determinants of hospitalisations and mortality in patients with PH-LHD, and the search strategy used allowed us to present the results of several recent and high-quality publications on the topic.

Conclusion

The majority of studies included in this review showed that PH is an independent predictor of mortality in patients with LHD, with the more consistent evidence being in those with HF and MR. Information on readmission for heart failure was somehow very limited. The majority of this information derives from studies in Western and developed countries, and may not apply to populations in other settings. All together, these findings suggest that the hypothesis of targeting PH to improve the outcomes of patients with LHD s should be actively investigated.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Contributors: AD and APK conceived and designed the protocol. AD, APK and KS performed the literature search, selection and quality assessment of the articles and extraction of the data. AD, APK, FT and KS interpreted the data. AQ wrote the first draft of the manuscript. AD, APK, KS and FT contributed to the writing of the manuscript and agreed with manuscript results and conclusions. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding: This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

References

- 1.Fang JC, DeMarco T, Givertz MM, et al. World Health Organization Pulmonary Hypertension group 2: pulmonary hypertension due to left heart disease in the adult—a summary statement from the Pulmonary Hypertension Council of the International Society for Heart and Lung Transplantation. J Heart Lung Transplant 2012;31:913–33 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Simonneau G, Gatzoulis MA, Adatia I, et al. Updated clinical classification of pulmonary hypertension. J Am Coll Cardiol 2013;62(25 Suppl):D34–41 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Guazzi M, Borlaug BA. Pulmonary hypertension due to left heart disease. Circulation 2012;126:975–90 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Haddad F, Kudelko K, Mercier O, et al. Pulmonary hypertension associated with left heart disease: characteristics, emerging concepts, and treatment strategies. Prog Cardiovasc Dis 2011;54:154–67 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Segers VF, Brutsaert DL, De Keulenaer GW. Pulmonary hypertension and right heart failure in heart failure with preserved left ventricular ejection fraction: pathophysiology and natural history. Curr Opin Cardiol 2012;27:273–80 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Vachiery JL, Adir Y, Barbera JA, et al. Pulmonary hypertension due to left heart diseases. J Am Coll Cardiol 2013;62(25 Suppl):D100–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Parker MW, Mittleman MA, Waksmonski CA, et al. Pulmonary hypertension and long-term mortality in aortic and mitral regurgitation. Am J Med 2010;123:1043–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Adhyapak SM. Effect of right ventricular function and pulmonary pressures on heart failure prognosis. Prev Cardiol 2010;13:72–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Merlos P, Nunez J, Sanchis J, et al. Echocardiographic estimation of pulmonary arterial systolic pressure in acute heart failure. Prognostic implications. Eur J Intern Med 2013;24:562–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Agarwal R, Shah SJ, Foreman AJ, et al. Risk assessment in pulmonary hypertension associated with heart failure and preserved ejection fraction. J Heart Lung Transplant 2012;31:467–77 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Agarwal R. Prevalence, determinants and prognosis of pulmonary hypertension among hemodialysis patients. Nephrol Dial Transplant 2012;27:3908–14 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Aronson D, Eitan A, Dragu R, et al. Relationship between reactive pulmonary hypertension and mortality in patients with acute decompensated heart failure. Circ Heart Fail 2011;4:644–50 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bursi F, McNallan SM, Redfield MM, et al. Pulmonary pressures and death in heart failure: a community study. J Am Coll Cardiol 2012;59:222–31 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Strange G, Playford D, Stewart S, et al. Pulmonary hypertension: prevalence and mortality in the Armadale echocardiography cohort. Heart 2012;98:1805–11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mutlak D, Aronson D, Carasso S, et al. Frequency, determinants and outcome of pulmonary hypertension in patients with aortic valve stenosis. Am J Med Sci 2012;343:397–401 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tatebe S, Fukumoto Y, Sugimura K, et al. Clinical significance of reactive post-capillary pulmonary hypertension in patients with left heart disease. Circ J 2012;76:1235–44 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Stern J, Heist EK, Murray L, et al. Elevated estimated pulmonary artery systolic pressure is associated with an adverse clinical outcome in patients receiving cardiac resynchronization therapy. Pacing Clin Electrophysiol 2007;30:603–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lee WT, Peacock AJ, Johnson MK. The role of per cent predicted 6-min walk distance in pulmonary arterial hypertension. Eur Respir J 2010;36:1294–301 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Moller JE, Hillis GS, Oh JK, et al. Prognostic importance of secondary pulmonary hypertension after acute myocardial infarction. Am J Cardiol 2005;96:199–203 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cappola TP, Felker GM, Kao WH, et al. Pulmonary hypertension and risk of death in cardiomyopathy: patients with myocarditis are at higher risk. Circulation 2002;105:1663–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Szwejkowski BR, Elder DH, Shearer F, et al. Pulmonary hypertension predicts all-cause mortality in patients with heart failure: a retrospective cohort study. Eur J Heart Fail 2012;14:162–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Abramson SV, Burke JF, Kelly JJ, Jr, et al. Pulmonary hypertension predicts mortality and morbidity in patients with dilated cardiomyopathy. Ann Intern Med 1992;116:888–95 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kjaergaard J, Akkan D, Iversen KK, et al. Prognostic importance of pulmonary hypertension in patients with heart failure. Am J Cardiol 2007;99:1146–50 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Shalaby A, Voigt A, El-Saed A, et al. Usefulness of Pulmonary Artery Pressure by Echocardiography to Predict Outcome in Patients Receiving Cardiac Resynchronization Therapy Heart Failure. Am J Cardiol 2008;101:238–41 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Damy T, Goode KM, Kallvikbacka-Bennett A, et al. Determinants and prognostic value of pulmonary arterial pressure in patients with chronic heart failure. Eur Heart J 2010;31:2280–90 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ristow B, Ali S, Ren X, et al. Elevated pulmonary artery pressure by Doppler echocardiography predicts hospitalization for heart failure and mortality in ambulatory stable coronary artery disease: the Heart and Soul Study. J Am Coll Cardiol 2007;49:43–9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Grigioni F, Potena L, Galie N, et al. Prognostic implications of serial assessments of pulmonary hypertension in severe chronic heart failure. J Heart Lung Transplant 2006;25:1241–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Levine TB, Levine AB, Goldberg D, et al. Impact of medical therapy on pulmonary hypertension in patients with congestive heart failure awaiting cardiac transplantation. Am J Cardiol 1996;78:440–3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lam CSP, Roger VL, Rodeheffer RJ, et al. Pulmonary hypertension in heart failure with preserved ejection fraction: a community-based study. J Am Coll Cardiol 2009;53:1119–26 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Khush KK, Tasissa G, Butler J, et al. Effect of pulmonary hypertension on clinical outcomes in advanced heart failure: Analysis of the Evaluation Study of Congestive Heart Failure and Pulmonary Artery Catheterization Effectiveness (ESCAPE) database. Am Heart J 2009;157:1026–34 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ghio S, Gavazzi A, Campana C, et al. Independent and additive prognostic value of right ventricular systolic function and pulmonary artery pressure in patients with chronic heart failure. J Am Coll Cardiol 2001;37:183–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wang D, Han Y, Zang H, et al. Prognostic effects of pulmonary hypertension in patients undergoing cardiac resynchronization therapy. J Thorac Dis 2010;2:71–5 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ghio S, Temporelli PL, Klersy C, et al. Prognostic relevance of a non-invasive evaluation of right ventricular function and pulmonary artery pressure in patients with chronic heart failure. Eur J Heart Fail 2013;15:408–14 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Naidoo DP, Mitha AS, Vythilingum S, et al. Pulmonary hypertension in aortic regurgitation: early surgical outcome. Q J Med 1991;80:589–95 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Fawzy ME, Hassan W, Stefadouros M, et al. Prevalence and fate of severe pulmonary hypertension in 559 consecutive patients with severe rheumatic mitral stenosis undergoing mitral balloon valvotomy. J Heart Valve Dis 2004;13:942–7; discussion 47–8 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Roselli EE, Abdel Azim A, Houghtaling PL, et al. Pulmonary hypertension is associated with worse early and late outcomes after aortic valve replacement: implications for transcatheter aortic valve replacement. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2012;144:1067–74 e2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Melby SJ, Moon MR, Lindman BR, et al. Impact of pulmonary hypertension on outcomes after aortic valve replacement for aortic valve stenosis. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2011;141:1424–30 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Le Tourneau T, Richardson M, Juthier F, et al. Echocardiography predictors and prognostic value of pulmonary artery systolic pressure in chronic organic mitral regurgitation. Heart 2010;96:1311–17 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kainuma S, Taniguchi K, Toda K, et al. Pulmonary hypertension predicts adverse cardiac events after restrictive mitral annuloplasty for severe functional mitral regurgitation. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2011;142:783–92 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Barbieri A, Bursi F, Grigioni F, et al. Prognostic and therapeutic implications of pulmonary hypertension complicating degenerative mitral regurgitation due to flail leaflet: a multicenter long-term international study. Eur Heart J 2011;32:751–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Manners JM, Monro JL, Ross JK. Pulmonary hypertension in mitral valve disease: 56 surgical patients reviewed. Thorax 1977;32:691–6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Malouf JF, Enriquez-Sarano M, Pellikka PA, et al. Severe pulmonary hypertension in patients with severe aortic valve stenosis: clinical profile and prognostic implications. J Am Coll Cardiol 2002;40:789–95 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Khandhar S, Varadarajan P, Turk R, et al. Survival benefit of aortic valve replacement in patients with severe aortic regurgitation and pulmonary hypertension. Ann Thorac Surg 2009;88:752–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Zuern CS, Eick C, Rizas K, et al. Prognostic value of mild-to-moderate pulmonary hypertension in patients with severe aortic valve stenosis undergoing aortic valve replacement. Clin Res Cardiol 2012;101:81–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ben-Dor I, Goldstein SA, Pichard AD, et al. Clinical profile, prognostic implication, and response to treatment of pulmonary hypertension in patients with severe aortic stenosis. Am J Cardiol 2011;107:1046–51 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Yang C, Li D, Mennett R, et al. The impact of pulmonary hypertension on outcomes of patients with low left ventricular ejection fraction: a propensity analysis. J Heart Valve Dis 2012;21:767–73 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Nozohoor S, Hyllen S, Meurling C, et al. Prognostic value of pulmonary hypertension in patients undergoing surgery for degenerative mitral valve disease with leaflet prolapse. J Card Surg 2012;27:668–75 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ward C, Hancock BW. Extreme pulmonary hypertension caused by mitral valve disease. Natural history and results of surgery. Br Heart J 1975;37:74–8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ghoreishi M, Evans CF, DeFilippi CR, et al. Pulmonary hypertension adversely affects short- and long-term survival after mitral valve operation for mitral regurgitation: implications for timing of surgery. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2011;142:1439–52 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Cam A, Goel SS, Agarwal S, et al. Prognostic implications of pulmonary hypertension in patients with severe aortic stenosis. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2011;142:800–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Pai RG, Varadarajan P, Kapoor N, et al. Aortic valve replacement improves survival in severe aortic stenosis associated with severe pulmonary hypertension. Ann Thorac Surg 2007;84:80–5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Hayden JA, Cote P, Bombardier C. Evaluation of the quality of prognosis studies in systematic reviews. Ann Intern Med 2006;144:427–37 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.de Jonge RC, van Furth AM, Wassenaar M, et al. Predicting sequelae and death after bacterial meningitis in childhood: a systematic review of prognostic studies. BMC Infect Dis 2010;10:232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Vahanian A, Alfieri O, Andreotti F, et al. [Guidelines on the management of valvular heart disease (version 2012). The Joint Task Force on the Management of Valvular Heart Disease of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) and the European Association for Cardio-Thoracic Surgery (EACTS)]. G Ital Cardiol (Rome) 2013;14:167–214 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Goldstone AB, Chikwe J, Pinney SP, et al. Incidence, epidemiology, and prognosis of residual pulmonary hypertension after mitral valve repair for degenerative mitral regurgitation. Am J Cardiol 2011;107:755–60 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Damasceno A, Mayosi BM, Sani M, et al. The causes, treatment, and outcome of acute heart failure in 1006 Africans from 9 countries. Arch Intern Med 2012;172:1386–94 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Janda S, Shahidi N, Gin K, et al. Diagnostic accuracy of echocardiography for pulmonary hypertension: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Heart 2011;97:612–22 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.