Abstract

Typical characteristics of chronic congestive heart failure (HF) are increased sympathetic drive, altered autonomic reflexes, and altered body fluid regulation. These abnormalities lead to an increased risk of mortality, particularly in the late stage of chronic HF. Recent evidence suggests that central nervous system (CNS) mechanisms may be important in these abnormalities during HF. Exercise training (ExT) has emerged as a nonpharmacological therapeutic strategy substitute with significant benefit to patients with HF. Regular ExT improves functional capacity as well as quality of life and perhaps prognosis in chronic HF patients. The mechanism(s) by which ExT improves the clinical status of HF patients is not fully known. Recent studies have provided convincing evidence that ExT significantly alleviates the increased sympathetic drive, altered autonomic reflexes, and altered body fluid regulation in HF. This review describes and highlights the studies that examine various central pathways involved in autonomic outflow that are altered in HF and are improved following ExT. The increased sympathoexcitation is due to an imbalance between inhibitory and excitatory mechanisms within specific areas in the CNS such as the paraventricular nucleus (PVN) of the hypothalamus. Studies summarized here have revealed that ExT improves the altered inhibitory pathway utilizing nitric oxide and GABA mechanisms within the PVN in HF. ExT alleviates elevated sympathetic outflow in HF through normalization of excitatory glutamatergic and angiotensinergic mechanisms within the PVN. ExT also improves volume reflex function and thus fluid balance in HF. Preliminary observations also suggest that ExT induces structural neuroplasticity in the brain of rats with HF. We conclude that improvement of the enhanced CNS-mediated increase in sympathetic outflow, specifically to the kidneys related to fluid balance, contributes to the beneficial effects of ExT in HF.

Keywords: central nervous system, sympathetic activity, paraventricular nucleus

this article is part of a collection on Cardiovascular Response to Exercise. Other articles appearing in this collection, as well as a full archive of all collections, can be found online at http://ajpheart.physiology.org/.

Introduction

Typical characteristics of chronic congestive heart failure (HF) are increased sympathetic drive, altered autonomic reflexes, and altered body fluid regulation (50, 52, 83). These abnormalities lead to an increased risk of mortality, particularly in the late stage of chronic HF. Although there has been considerable progress in elucidating the peripheral mechanisms involved in these abnormalities, these findings do not totally account for the elevated neurohumoral drive and altered fluid volume regulation in the late stage of chronic HF. Evidence suggests that central nervous system (CNS) mechanisms may be important in these abnormalities during HF (52, 83).

Exercise training (ExT) has been demonstrated to be beneficial to patients with HF (8, 72). The majority of existing data support an improvement of quality of life after ExT in patients with HF (22, 57). The mechanism(s) by which ExT improves the clinical status of patients with HF is not fully understood. ExT has been shown to significantly reduce muscle sympathetic nerve activity (60) and enhance endothelial function in patients with HF (25). In patients with ischemic heart disease, ExT produces a decrease in plasma norepinephrine concentration, an index of neurohumoral drive (5). ExT in animal models of HF improves baroreflex function and also brings the basal renal nerve activity and plasma levels of norepinephrine and angiotensin II (ANG II) back down to normal (38). These improvements may be partially responsible for abatement/attenuation of the increased neurohumoral drive typically observed in HF. This review highlights and describes recent studies that examine various central pathways involved in autonomic outflow that are altered in HF and provide evidence for implicating ExT as a viable therapeutic modality for changes in the CNS, particularly the paraventricular nucleus (PVN) of the hypothalamus in the regulation of sympathetic outflow specifically to the kidney.

PVN Involved in Increased Sympathetic Nerve Activity in Animals With HF

The myocardial infarct model in rats mimics the most common cause of HF in humans (9, 27, 53). Using this model of HF, our studies and work by others have revealed that 1) the volume reflex is blunted (9), 2) the baroreflex is blunted (27), and 3) turnover of norepinephrine is increased in various discrete peripheral tissues such as the kidney, heart, and skeletal muscle but not changed in other visceral tissues such as the intestine and liver (53). Esler et al. (14) have shown that there is increased spillover of norepinephrine from the kidney and heart but not from the mesenteric circulation. In accord with the increase in turnover of norepinephrine from the kidney, renal sympathetic nerve activity (RSNA) in conscious and anesthetized rats is also reported to be elevated in HF (10, 16).

Rats with coronary artery ligation-induced HF have increased catecholamine turnover and lower levels of serotonin metabolism in the CNS (64, 65). Subsequently, in rats with HF, specific central areas have been examined and norepinephrine is increased in several forebrain and brain stem cell groups, including the PVN of the hypothalamus (64). We have found significantly increased hexokinase activity (an index of neuronal activity) in the parvocellular PVN (pPVN) and magnocellular PVN (mPVN) of rats with HF (56). We also have shown that there is increased c-Fos staining in the PVN of rats with HF (54), consistent with increased FosB staining observed previously (68). This finding has been confirmed in the same model by direct recording of increased firing of rostral ventrolateral medulla (RVLM) projecting PVN neurons (unpublished data) and PVN neurons in general (78). Cell bodies in pPVN neurons are known to receive information from the volume receptors as well as the myocardium, particularly from chemically sensitive vagal afferents (6, 40). Therefore, it seems likely that pPVN would receive input from these afferents. These changes may lead to the altered baroreflex, volume reflex, and increased sympathetic activity observed in HF.

We have proposed that the increase in activation of the PVN neurons that drives the sympathoexcitation in HF is a result of the imbalance between the inhibitory nitric oxide (NO∙) and GABA mechanisms, and the excitatory glutamatergic and angiotensinergic mechanisms. This review highlights these CNS mechanisms in HF and the effects of ExT in alleviating the influences of these opposing mechanisms that result in the detrimental sympathoexcitation and altered fluid balance of HF.

ExT and General Hemodynamic and Neurohumoral Characteristics in HF

The data present here are mostly obtained from the coronary artery ligation model of HF used extensively by this laboratory (34, 74) and others (19, 28). The utility of this model as a simulation of HF is demonstrated by increased left ventricular end-diastolic pressure (LVEDP), decreased rate of change in pressure (dP/dt) in the left ventricle, decreased ejection fraction, and >30% infarct size at the time of the experiment, 6–8 wk after the coronary artery ligation procedure. The advantage of using this model, as opposed to other models of HF, such as ventricular pacing, is that ligation of the coronary artery mimics blockage of the artery, commonly seen in patients with HF. However, it is recognized that this does not precisely mimic the human HF condition, which is a consequence of a long process of blood vessel alteration leading to myocardial infarction.

Interestingly, we have found that ExT only partially improves the increased LVEDP and the decreased dP/dt. ExT fails to improve the decreased ejection fraction associated with HF, indicating that it does not normalize cardiac function per se in this model of HF. In our experience we have observed that the higher the severity of the infarct (>50%), the lower the possibility of reversal of the cardiac function parameters with ExT. In other words, the more severe the infarct of heart, the less likely the reversal of cardiac function with ExT. This combined with the relatively short duration of ExT (4 wk) leads to some changes in centrally mediated autonomic function, but the cardiac remodeling remains relatively limited (31). The HF-ACTION study done in patients with left ventricular ejection fraction of only 25% demonstrated that ExT results in nonsignificant reductions in the primary end point of all-cause mortality but improves quality of life. After adjustment for highly prognostic predictors of the primary end point, ExT was found to reduce the incidence of all-cause mortality as well (HF-ACTION trial) (48).

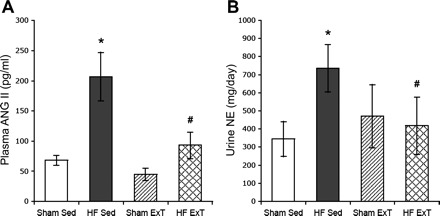

In the coronary artery ligated model of HF, there is increased neurohumoral drive that is alleviated with ExT (31). We have found urinary norepinephrine and plasma ANG II are increased in HF and are reduced by ExT (Fig. 1). Similarly, ExT reduces sympathetic nerve activity in other species and humans (18, 21). Interestingly there is clear improvement in neurohumoral drive by ExT particularly in patients with the highest activation of the sympathetic nervous system (43). This suggests that ExT normalizes the increased overall sympathetic outflow associated with HF. The beneficial effects of ExT in patients with HF may be primarily due to improvement of the neurohumoral drive and its consequent effects with regard to cardiovascular regulation and fluid balance. This improvement in circulation may lead to an enhancement of cardiac output independent of changes in cardiac function per se. It is also likely that reduced cardiac damage and increased duration of ExT may both contribute to improvement of cardiac function with ExT regimen. The rest of the review describes recent studies that elucidate specific CNS pathways/mechanisms involved in altered autonomic outflow in HF.

Fig. 1.

Plasma angiotensin II (ANG II; A) and urinary norepinephrine (NE; B) in sham-sedentary (Sed); heart failure (HF)-Sed, sham-exercise-trained (ExT), and HF-ExT rats. Values are means ± SE. *P < 0.05, significantly different from the respective sham group. #P < 0.05, significantly different from the respective sedentary group. [From Kleiber et al. (31).]

ExT and Central Inhibitory NO∙ Mechanism in HF

NO∙ acts as a nonconventional neurotransmitter/neuromodulator in the CNS (32). The distribution of the brain isoform of neuronal NO∙ synthase (nNOS) is highly localized to discrete regions of the brain. Many nNOS-containing areas are also well known for their roles in the regulation of the cardiovascular system. In the hypothalamus, nNOS-positive neurons are found primarily in the PVN (49, 62) and supraoptic nuclei (SON) (12). Generally, NO∙ in the PVN is shown to inhibit sympathetic outflow (76). Administration of NO∙ donor sodium nitroprusside decreases RSNA and arterial pressure; conversely, blocking the synthesis of NO∙ with N-monomethyl-l-arginine (l-NMMA) in the PVN increases RSNA and arterial pressure. These data suggest that NO∙ is inhibitory within the PVN.

The HF condition is known to produce attenuated vasodilation in response to agonists known to operate via a NO∙ mechanism (13). The levels of endogenous endothelial NOS (eNOS) protein and mRNA in peripheral tissues are reduced in the HF state (63). We have shown that nNOS mRNA in the hypothalamus and NOS-positive neurons (NADPH-positive neurons) are decreased in the PVN of rats with HF compared with sham-operated rats (77). We have also found that endogenous NO∙-mediated inhibition of RSNA within the PVN is blunted in rats with HF (74). This set of observations suggests that an altered endogenous NO∙ mechanism may contribute to the increased sympathetic nerve activity commonly observed in the HF state.

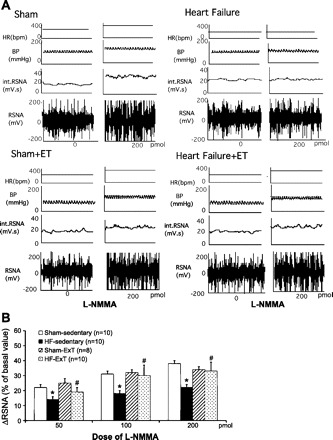

ExT reverses the alterations in the nNOS-NO∙ pathways in the carotid body responsible for chemoreceptor sensitization in HF (36). ExT in rabbits with HF (pacing-induced model of HF) has also been shown to decrease RSNA (38). Consistent with these observations, ExT in rats with HF has also been shown to decrease plasma levels of norepinephrine (31). Figure 2 shows that 3–4 wk of ExT restores the number of nNOS-positive neurons in the PVN of rats with HF. nNOS mRNA expression and protein levels in the PVN are also normalized following ExT in rats with HF (81). Furthermore, blockade of endogenous NO∙ production within the PVN with l-NMMA produces a blunted increase in RSNA, arterial pressure, and heart rate in rats with HF compared with sham-operated rats. Again, ExT normalizes the attenuated RSNA responses in rats with HF (Fig. 3). The data suggest that ExT induces an increase in the density of nNOS-positive neurons, nNOS message, and nNOS protein in rats with HF. This may lead to an increase in the synthesis of NO∙ in the PVN, which subsequently causes an increased inhibitory effect on RSNA.

Fig. 2.

A: NADPH-diaphorase-labeled neurons in the paraventricular nucleus (PVN) of sham-Sed, HF-Sed, sham-ExT, and HF-ExT rats. B: number of NADPH-diaphorase-labeled [nitric oxide synthase (NOS) positive] neuron cells in the PVN, supraoptic nucleus (SON), lateral hypothalamus (LH), and median preoptic area (MnPO). Values are means ± SE. *P < 0.05, significantly different from the respective sham group. #P < 0.05, significantly different from the respective sedentary group. [From Zheng et al. (81).]

Fig. 3.

A: segments of original recordings from individual rats from each experimental group showing responses of renal sympathetic nerve activity (RSNA), integral of RSNA (int. RSNA), arterial blood pressure (BP), and heart rate (HR) to different doses of N-monomethyl-l-arginine (l-NMMA) injected into the PVN. bpm, beats/min. B: mean changes in RSNA (ΔRSNA) following injections of l-NMMA into the PVN. *P < 0.05, significantly different from the respective sham group; #P < 0.05, significantly different from the respective sedentary group. [From Zheng et al. (81).]

ExT and Central GABAergic Tone in HF

GABA is a well-known inhibitory neurotransmitter in the CNS. A large body of evidence suggests that GABA plays an important role in central cardiovascular control (4, 24). It appears that central GABA exerts its cardiovascular effect through both autonomic and humoral pathways. GABA is reported to be a dominant inhibitory neurotransmitter in the PVN. Iontophoretically applied GABA depresses the firing rate of PVN neurosecretory cells (61). Microinjection of GABA antagonist within the PVN produces an increase in RSNA, and activation of GABAA receptor with muscimol produces a decrease in RSNA in normal rats (75). Our studies in rats with HF have demonstrated that there is reduced endogenous GABA-mediated inhibition on renal sympathetic outflow in HF (75).

GABAA receptors are heterogeneously composed throughout the mammalian brain from various subunits, mainly the α-, β-, and γ-subunits. The rodent brain contains several forms of each subunit, including six α-subunits (α1–α6), three β-subunits (β1–β3), and three γ-subunits (γ1–γ3). Electrophysiological studies indicate that different subunit combinations may mediate different physiological or pharmacological properties (26). Within the PVN, the α1-, β1-, β3-, and γ2-subunits predominate. Among γ-subunits, the γ2-subunit appears to be most widely distributed, and it may play an essential role in GABAA receptor subunit clustering (69).

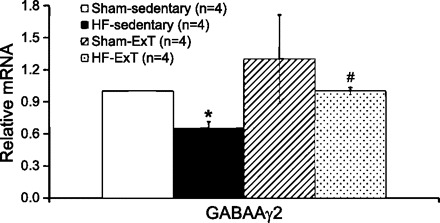

We have measured the expression of GABAAγ2 receptor mRNA from PVN tissue. GABAAγ2 mRNA of HF rats is found to decrease by 35% compared with sham rats. In exercise-trained HF rats, GABAAγ2 mRNA levels are restored back to those in the sham-sedentary group and differ significantly from those in the HF-sedentary group (Fig. 4). The increase in GABAAγ2 mRNA in the PVN of the exercise-trained HF group, compared with HF-sedentary levels, may contribute to normalization of sympathetic drive after ExT. Interestingly, a study by others shows that ExT restores GABAAγ2 levels toward control values in surrounding astrocytes of both motor pools in the spinal cord of rats (30). Since the γ2-subunit is involved with GABAA receptor trafficking and synaptic clustering, it appears that this subunit could be an important component of the activity-dependent response.

Fig. 4.

Real-time PCR data for the PVN. Relative GABAAγ2 expression was calculated using the Pfaffl method for quantification. *P < 0.05, significantly different from the respective sham group. #P < 0.05, significantly different from the respective sedentary group.

ExT ameliorates the symptom of HF via reduced sympathoexcitation, which may also be through improving central GABAergic tone. Bilateral microinjections of bicuculline into the RVLM increase lumbar sympathetic nerve activity in sedentary animals, which is blunted in exercise-trained animals (45). Bradycardic responses to bilateral microinjections of bicuculline in the nucleus tractus solitarii (NTS) are attenuated by ExT (46). These data indicate that alterations of GABAergic mechanisms within the CNS, at both the hypothalamic and brain stem level, may contribute importantly to regulation of sympathetic activity and heart rate in exercise-trained animals. The changes in autonomic outflow observed in exercise-trained animals seem to be induced or influenced by activity-dependent plasticity in the CNS at different levels of the neuroaxis. For example, ExT reduces the elevated firing rate of caudal hypothalamic neurons in spontaneous hypertensive rats (SHR) (3). The spontaneous firing rate of neurons in the posterior hypothalamic area is reduced after ExT. ExT has also been shown to upregulate the GABAergic system in the caudal hypothalamus, thus demonstrating an increased inhibitory component within the CNS to dictate general sympathetic nerve activity (37).

ExT and Central Excitatory Glutamatergic Tone in HF

As a major excitatory neurotransmitter, glutamate has been found to modulate sympathetic nerve activity in several brain areas, including the hypothalamus, specifically in the PVN and the RVLM. N-methyl-d-aspartic acid (NMDA) and α-amino-3-hydroxy-5-methyl-4-isoxazolepropionic acid (AMPA) receptors, the two major ionotropic glutamate receptors, exist in the PVN (23), which suggests that both receptors may mediate the glutamate-induced excitatory action in the PVN. Functional studies have shown that glutamate receptors within the PVN are involved in cardiovascular reflexes (1). Microinjection of NMDA into the PVN significantly increases RSNA, and this response is potentiated in HF rats (34). Additionally, blocking the NMDA receptors with AP5 produced a significantly greater decrease in RSNA and arterial pressure in rats with HF, which suggests the greater endogenous glutamatergic tone (34). The increased activity of PVN neurons associated with HF is due to an increase in glutamatergic mechanisms within the PVN (34). The increase in RSNA response to NMDA is greater in HF rats, which correlates with an increased expression of the NMDA NR1 receptor within the PVN. Together, these studies demonstrate that the glutamatergic tone is increased in the PVN of rats with HF via an upregulation of NMDA NR1 receptor.

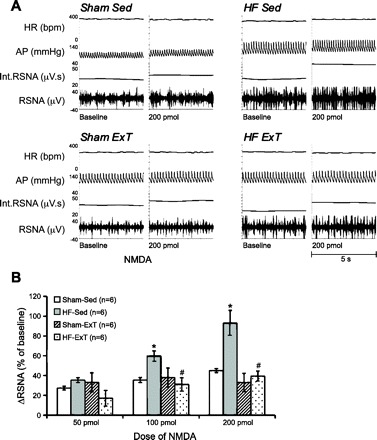

We have observed that ExT normalizes the potentiated increase in RSNA in response to NMDA microinjected into the PVN in rats with HF (Fig. 5). The subsequent results demonstrate that NR1 expression in the PVN of exercise-trained HF rats is not different from that in sham-sedentary rats or sham-ExT rats (31). Together, these results indicate that one mechanism by which ExT normalizes sympathetic outflow in HF is normalization of glutamatergic mechanism within the PVN. Other studies have also indicated the activation of the RVLM with unilateral microinjections of glutamate increases lumbar sympathetic nerve activity in sedentary animals but is also attenuated by ExT for a period of 8–10 wk (45). Bilateral microinjections of the ionotropic glutamate receptor antagonist kynurenate produce small increase in arterial pressure and lumbar sympathetic nerve activity that are similar between sedentary and ExT groups (45). These results suggest that ExT may reduce increases in lumbar sympathetic nerve activity due to reduced activation of the RVLM by a glutamatergic mechanism in an increased sympathoexcitatory condition.

Fig. 5.

A: segments of original recordings from individual rats from each experimental group showing responses of RSNA, int. RSNA, arterial blood pressure (AP), and HR to different doses of N-methyl-d-aspartic acid (NMDA) injected into the PVN. B: ΔRSNA following injections of NMDA into the PVN. *P < 0.05, significantly different from the respective sham group. #P < 0.05, significantly different from the respective sedentary group. [From Kleiber et al. (31).]

ExT and Centrally Mediated Angiotensin II on Sympathoexcitation in HF

ANG II has been found to act as a neurotransmitter in the CNS and is involved in the regulation of sympathetic activity to the cardiovascular system (33). In various autonomic areas of the brain, such as the PVN and the RVLM, ANG II has been shown to contribute as a sympathoexcitatory input under basal conditions as well to sympathoexcitatory reflexes, such as the cardiac sympathetic afferent reflex, baroreflex, and arterial chemoreflex in HF (2, 20, 71). Microinjection of ANG II into the PVN significantly increases RSNA more in rats with HF compared with sham-operated rats (82). ANG II type 1 (AT1) receptor mRNA message, protein, and immunostaining are increased in the PVN of rats with HF. There is a significant difference in the response to AT1 receptor antagonist losartan in the PVN in HF, namely, the fact that RSNA and heart rate responses to losartan in HF rats are significantly greater than the responses observed in sham rats (82). These results suggest that enhanced AT1 receptor-mediated angiotensin action in the PVN on sympathetic outflow may contribute to sympathetic dysfunction in HF. Recently, the role of nonclassical pathways of renin-angiotensin system (RAS) genes such as angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) and Mas receptor in the CNS and their participation in central sympathetic activation have also been widely addressed (11, 17, 29, 73).

Our recent study indicates that ExT normalizes the potentiated increase in RSNA in response to ANG II microinjection into the PVN in rats with HF. Furthermore, whereas expression of the AT1 receptor within the PVN is increased in HF rats, the results from exercise-trained HF rats demonstrated that AT1 expression in the PVN was significantly decreased compared with the sedentary HF rats (unpublished data). The results indicate that one mechanism by which ExT normalizes sympathetic outflow in HF is normalization of angiotensinergic mechanisms within the PVN.

Activation of the central RAS in animals with HF involves a possible imbalance of ACE and ACE2 in regions of the brain that regulate autonomic function. It is possible that ExT reverses/alters this imbalance and thus improves the ANG II-mediated sympathoexcitation in HF (29). ExT normalized the upregulation of ACE protein and mRNA in the cerebellum, medulla, hypothalamus, PVN, NTS, and RVLM of chronic HF rabbits. ExT also increased ACE2 expression in these brain sites in chronic HF (29). ExT produces a concurrent training-induced reduction of both angiotensinogen mRNA expression in brain stem cardiovascular-controlling areas and mean arterial pressure in SHR rats (15). Renin-angiotensin blockers that reduce brain renin-angiotensin conversion and/or production also decrease arterial pressure in SHR rats (15). These results suggest that ExT is as efficient as the renin-angiotensin blockers to reduce brain RAS over activity and to decrease arterial pressure.

ExT and Centrally Mediated Regulation of Fluid Balance in HF

Coexistence of HF and renal abnormality are increasingly referred to as the “cardiorenal syndrome.” The co-occurrence of cardiac and renal dysfunction has important therapeutic and prognostic implications in patients with HF. The majority of patients hospitalized for HF have advanced renal dysfunction; this comorbid renal insufficiency is associated with significantly increased morbidity and mortality risk (59). Comorbid renal dysfunction can result from intrinsic renal disease and/or inadequate renal perfusion of cardiac origin. Both HF and renal dysfunction stimulate neurohormonal activation, resulting in reduced cardiac output. Managing these patients with cardiorenal syndrome requires successful calibration of a delicate balance between adequate volume reduction and adequate renal function.

An impaired ability to excrete a sodium load is a hallmark of chronic HF. An acute volume expansion produces a blunted diuresis and natriuresis in humans and various animal models of HF (55, 66). This decrease in diuretic and natriuretic response to acute increase in volume is due to a blunted reduction in renal nerve activity. ExT normalizes the blunted diuretic and natriuretic responses in HF rats (Fig. 6, A and B). This effect of ExT is absent in renal denervated HF rats. Consistent with these results, measurement of RSNA demonstrates that acute volume expansion produces a reduced renal sympathoinhibition in the HF group compared with sham-treated rats (55). ExT improved the renal sympathoinhibition in the HF group compared with the sham-treated group (80) (Fig. 6C). This observation, combined with the observation that renal denervation normalizes the renal excretory responses to volume expansion, suggests that renal nerves are involved in the blunted renal excretory responses to volume expansion in rats with HF.

Fig. 6.

Urine flow (A), sodium excretion (B), and RSNA (C) in response to acute volume expansion [% of body weight (BW)] with isotonic saline in sham-Sed (sham), sham-ExT, HF-Sed (HF), and HF-ExT rats. Values are means ± SE for each parameter (n = 6–7). *P < 0.05, significantly different from the respective sham group. #P < 0.05, significantly different from the respective sedentary group. [Modified from Zheng et al. (80).]

It is of interest that nNOS within the PVN has been demonstrated to be an important contributor to the volume expansion-mediated renal sympathoinhibition in normal rats (35). Blocking the NO∙-mediated mechanisms/signaling pathways within the PVN of normal rats results in a blunted volume reflex. It may well be that the observed decrease in nNOS within the PVN of rats with chronic HF may be responsible for the altered volume reflex in rats with chronic HF. Interestingly, ExT restores the central nNOS levels in the PVN (81) and concomitantly improves the renal sympathoinhibition to acute volume expansion as well as the diuresis and natriuresis (80) (Fig. 6). It is postulated that ExT, by improving the central NO∙ mechanism within the PVN of rats with HF, improves the blunted RSNA response to acute volume expansion and thus the blunted diuretic and natriuretic responses to acute volume expansion.

The results of the studies summarized here show that improvement of the volume reflex due to ExT may be one contributing mechanism responsible for improving the prognosis in HF. Fluid overload is a key pathophysiological mechanism underlying both the acute decompensation episodes of HF and the progression of the syndrome. Moreover, it represents the most important factor responsible for the high readmission rates observed in these patients and is often associated with worsening of renal function, which by itself increases mortality risk. In this clinical context, the results form these studies suggest that ExT may be an excellent alternative to diuretics to obtain a quicker relief of pulmonary/systemic congestion.

ExT-Induced Structural Neuroplasticity in the Brain in HF

Brain plasticity is a phenomenon commonly limited to critical periods during development of the brain. Plasticity is an intrinsic property of the nervous system, retained throughout a lifespan, which is in fact an inherent property not only of the developing but also of the adult working brain (51). In the adult brain, vascular risk factors associated with HF, hypertension, and diabetes have been linked with signs of cerebrovascular dysfunction. Such disease states are also associated with brain abnormalities that have been linked with an increased the risk of onset of psychiatric disorder such as depression, bipolar disorder, and dementia (7).

There is an increasing body of evidence to indicate that ExT can induce significant functional and neuroanatomical plasticity in the adult brain (44, 47, 70). Exercise-induced neuroplasticity plays a crucial role in mediating important beneficial effects, including improved memory, cognitive function, and neuroprotection (44). There has been particular appeal for functional improvements, such as memory and cognitive skills that are associated with changes in the number, structure, and function of neurons. ExT may induce these changes by affecting genes involved in synaptic plasticity. Although these studies provide strong support for beneficial effects of ExT to improve cognitive function through alterations in plasticity-related genes, it is not known whether ExT produces similar changes in gene expression in regions of the brain that control sympathetic nervous system activity.

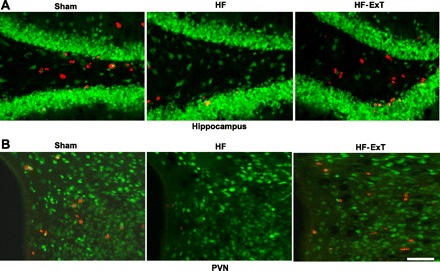

Recently, we have examined the neuroplasticity in the brain following ExT by using bromodeoxyuridine (BrdU) immunostaining (Fig. 7). BrdU is a synthetic nucleoside that is an analog of thymidine. It is commonly used in the detection of proliferating cells in living tissues. Our results indicate there are more BrdU-positive-staining neurons in the hippocampus and the PVN of exercise-trained rats with HF. This supports the possibility that neurons involved in the control of the sympathetic nervous system also undergo neural plasticity following periods of activity. One of the pioneering studies demonstrated that ExT produced neuroplastic changes in many sections of cardiorespiratory and locomotor areas including posterior hypothalamic area, NTS, and cerebral cortex (47). Most areas they have studied are reflective of potential sympathoexcitation. This may explain that the altered synaptic activity observed in HF may correlate with structural neuroplasticity in cardiorespiratory and locomotor areas.

Fig. 7.

Bromodeoxyuridine (BrdU; red) and NeuN (green)-labeled neurons in the hippocampus (A) and the PVN (B) from sham, HF, and HF-ExT rats. There are fewer BrdU-positive cells in the HF group compared with both the sham and HF-ExT groups in both the hippocampus and the PVN. Bar, 50 μm.

ExT-induced changes in the adult brain may be related to the activation of brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) (41) and/or circulating insulin-like growth factor (IGF-I) (67). Selective upregulation of BDNF in distinct subpopulations of cells in the motor nuclei may lead to changes of innervation targeting motor neurons. Exercise-induced brain uptake of blood-borne IGF-I could mediate the stimulatory effects of ExT on the adult hippocampus. Our preliminary results (Fig. 7) suggest that there are potentially critical changes in the BrdU staining in both the hippocampus and the PVN of rats with HF compared with the control rats. Although purely speculative at this time, it may well be that the changes in neuroplasticity, as we have observed in the PVN of rats with HF, may be indicative of the changes in improvement of the sympathoinhibitory and sympathoexcitatory mechanisms within the PVN. These possibilities remain to be validated/elucidated.

Summary

The effect of ExT on sympathetic nerve activity may reflect a generalized normalization of all known cardiovascular reflexes. Apart from the restoration of the volume reflex, as shown here, other investigators have previously demonstrated that baroreflex (39), chemoreflex (36), and the Bezold-Jarisch reflexes (79) are also improved in experimentally induced HF following ExT. This might imply that other mechanisms, such as increased sensitivity of the arterial chemoreceptor and/or activation of reflexes by the abnormal skeletal muscle, stimulate the sympathetic activation in HF, and that ExT appears to induce its beneficial effects by reducing activation of these sensory afferents (42, 58). Alternatively, ExT would be involved in enhancing the central component of the baroreflex and volume-mediated mechanoreceptors to reduce overall sympathetic outflow in HF.

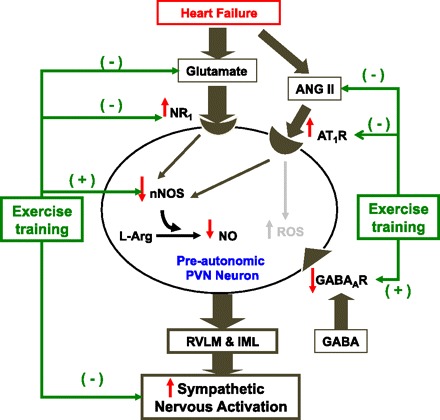

Improvement of the neurotransmitter mechanisms within the PVN by ExT provides a substrate or roadmap for tackling possible therapeutic strategies to treat and handle the complications of HF. We also provide some tantalizing new preliminary data that demonstrate ExT-induced changes in structural neuroplasticity in various specific areas of the brain of rats with HF. Such changes in neuroplasticity may be beneficial to the other co-occurring brain abnormalities such as depression commonly observed in patients with HF. We conclude that the benefit of ExT on central neural pathways involved in autonomic regulation, particularly within the PVN, contributes in a crucial way to the improvement of central neural control of sympathetic nerve activity in HF (Fig. 8).

Fig. 8.

A schematic diagram of the PVN-mediated activation of the sympathetic nervous outflow in HF and the effect of ExT on the specific excitatory and inhibitory pathways/mechanisms that may contribute to the enhanced sympathetic activation. In the HF condition there is an overexpression of NMDA type 1 (NR1) and angiotensin II type 1 receptors (AT1R) on the preautonomic neurons within the PVN. Thus activation of these receptors leads to increased sympathetic nervous system activation. At the same time, there are decreased levels of neuronal NOS (nNOS) and consequent GABAergic activation, leading to less inhibition of the preautonomic PVN neurons. ExT reverses the changes in NR1 and AT1R changes in HF as well as the changes in nNOS and GABA mechanisms, leading to normalization of the exaggerated sympathetic activation commonly observed in HF. RVLM, rostral ventrolateral medulla; IML, intermediolateral column.

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the author(s).

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Author contributions: K.P.P. and H.Z. conception and design of research; K.P.P. and H.Z. performed experiments; K.P.P. and H.Z. analyzed data; K.P.P. and H.Z. interpreted results of experiments; K.P.P. and H.Z. prepared figures; K.P.P. and H.Z. drafted manuscript; K.P.P. and H.Z. edited and revised manuscript; K.P.P. and H.Z. approved final version of manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1. Badoer E. Hypothalamic paraventricular nucleus and cardiovascular regulation. Clin Exp Pharmacol Physiol 28: 95–99, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Barbella Y, Cierco M, Israel A. Effect of Losartan, a nonpeptide angiotensin II receptor antagonist, on drinking behavior and renal actions of centrally administered renin. Proc Soc Exp Biol Med 202: 401–406, 1993 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Beatty JA, Kramer JM, Plowey ED, Waldrop TG. Physical exercise decreases neuronal activity in the posterior hypothalamic area of spontaneously hypertensive rats. J Appl Physiol 98: 572–578, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Chiodera P, Volpi R, Capretti L, Coiro V. Gamma-aminobutyric acid mediation of the inhibitory effect of nitric oxide on the arginine vasopressin and oxytocin responses to insulin-induced hypoglycemia. Regul Pept 67: 21–25, 1996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Cooksey JD, Reilly P, Brown S, Bomze H, Cryer PE. Exercise training and plasma catecholamines in patients with ischemic heart disease. Am J Cardiol 42: 372–376, 1978 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Coote JH. A role for the paraventricular nucleus of the hypothalamus in the autonomic control of heart and kidney. Exp Physiol 90: 169–173, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. de Toledo Ferraz Alves TC, Ferreira LK, Busatto GF. Vascular diseases and old age mental disorders: an update of neuroimaging findings. Curr Opin Psychiatry 23: 491–497, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Demopoulos L, Bijou R, Fergus I, Jones M, Strom J, LeJemtel TH. Exercise training in patients with severe congestive heart failure: enhancing peak aerobic capacity while minimizing the increase in ventricular wall stress. J Am Coll Cardiol 29: 597–603, 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. DiBona GF, Herman PJ, Sawin LL. Neural control of renal function in edema-forming states. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 254: R1017–R1024, 1988 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. DiBona GF, Jones SY, Brooks VL. ANG II receptor blockade and arterial baroreflex regulation of renal nerve activity in cardiac failure. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 269: R1189–R1196, 1995 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Diz DI, Garcia-Espinosa MA, Gegick S, Tommasi EN, Ferrario CM, Tallant EA, Chappell MC, Gallagher KP. Injections of angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 inhibitor MLN4760 into nucleus tractus solitarii reduce baroreceptor reflex sensitivity for heart rate control in rats. Exp Physiol 93: 694–700, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Dobrowolski L, Badzynska B, Walkowska A, Sadowski J. Osmotic hypertonicity of the renal medulla during changes in renal perfusion pressure in the rat. J Physiol 508: 929–935, 1998 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Drexler H, Lu W. Endothelial dysfunction of hindquarter resistance vessels in experimental heart failure. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 262: H1640–H1645, 1992 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Esler MD, Hasking GJ, Willett IR, Leonard PW, Jennings GL. Noradrenaline release and sympathetic nervous system activity. J Hypertens 3: 117–129, 1985 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Felix JV, Michelini LC. Training-induced pressure fall in spontaneously hypertensive rats is associated with reduced angiotensinogen mRNA expression within the nucleus tractus solitarii. Hypertension 50: 780–785, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Feng QP, Carlsson S, Thoren P, Hedner T. Characteristics of renal sympathetic nerve activity in experimental congestive heart failure in the rat. Acta Physiol Scand 150: 259–266, 1994 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Feng Y, Yue X, Xia H, Bindom SM, Hickman PJ, Filipeanu CM, Wu G, Lazartigues E. Angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 overexpression in the subfornical organ prevents the angiotensin II-mediated pressor and drinking responses and is associated with angiotensin II type 1 receptor downregulation. Circ Res 102: 729–736, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Fraga R, Franco FG, Roveda F, de Matos LN, Braga AM, Rondon MU, Rotta DR, Brum PC, Barretto AC, Middlekauff HR, Negrao CE. Exercise training reduces sympathetic nerve activity in heart failure patients treated with carvedilol. Eur J Heart Fail 9: 630–636, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Francis J, Wei SG, Weiss RM, Felder RB. Brain angiotensin-converting enzyme activity and autonomic regulation in heart failure. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 287: H2138–H2146, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Gao L, Wang W, Li YF, Schultz HD, Liu D, Cornish KG, Zucker IH. Superoxide mediates sympathoexcitation in heart failure: roles of angiotensin II and NAD(P)H oxidase. Circ Res 95: 937–944, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Gao L, Wang W, Liu D, Zucker IH. Exercise training normalizes sympathetic outflow by central antioxidant mechanisms in rabbits with pacing-induced chronic heart failure. Circulation 115: 3095–3102, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Gottlieb SS, Fisher ML, Freudenberger R. Effects of exercise training on peak performance and quality of life in congestive heart failure patients. J Card Fail 5: 188–194, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Herman JP, Eyigor O, Ziegler RD, Jennes L. Expression of ionotropic glutamate receptor subunit mRNAs in the hypothalamic paraventricular nucleus of the rat. J Comp Neurol 422: 352–362, 2000 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Hermes MLHJ, Coderre EM, Buijs RM, Renaud LP. GABA and glutamate mediate rapid neurotransmission from suprachiasmatic nucleus to hypothalamic paraventricular nucleus in rat. J Physiol 496: 749–757, 1996 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Hornig B, Maier V, Drexler H. Physical training improves endothelial function in patients with chronic heart failure. Circulation 93: 210–214, 1996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Huang R, Dillon G. Functional characterization of GABAA receptors in neonatal hypothalamic brain slice. Neuroscience 88: 1655–1663, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Jung R, Dibner-Dunlap ME, Gilles MA, Thames MD. Cardiorespiratory reflex control in rats with left ventricular dysfunction. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 268: H218–H225, 1995 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Kang YM, Ma Y, Elks C, Zheng JP, Yang ZM, Francis J. Cross-talk between cytokines and renin-angiotensin in hypothalamic paraventricular nucleus in heart failure: role of nuclear factor-kappaB. Cardiovasc Res 79: 671–678, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Kar S, Gao L, Zucker IH. Exercise training normalizes ACE and ACE2 in the brain of rabbits with pacing-induced heart failure. J Appl Physiol 108: 923–932, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Khristy W, Ali NJ, Bravo AB, de Leon R, Roy RR, Zhong H, London NJ, Edgerton VR, Tilakaratne NJ. Changes in GABAA receptor subunit gamma 2 in extensor and flexor motoneurons and astrocytes after spinal cord transection and motor training. Brain Res 1273: 9–17, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Kleiber AC, Zheng H, Schultz HD, Peuler JD, Patel KP. Exercise training normalizes enhanced glutamate-mediated sympathetic activation from the PVN in heart failure. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 294: R1863–R1872, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Krukoff TL. Central regulation of autonomic function: no brakes? Clin Exp Pharmacol Physiol 25: 474–478, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Kumagai K, Reid IA. Angiotensin II exerts differential actions on renal nerve activity and heart rate. Hypertension 24: 451–456, 1994 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Li YF, Cornish KG, Patel KP. Alteration of NMDA NR1 receptors within the paraventricular nucleus of hypothalamus in rats with heart failure. Circ Res 93: 990–997, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Li YF, Mayhan WG, Patel KP. Role of the paraventricular nucleus in renal excretory responses to acute volume expansion: role of nitric oxide. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 285: H1738–H1746, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Li YL, Ding Y, Agnew C, Schultz HD. Exercise training improves peripheral chemoreflex function in heart failure rabbits. J Appl Physiol 105: 782–790, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Little HR, Kramer JM, Beatty JA, Waldrop TG. Chronic exercise increases GAD gene expression in the caudal hypothalamus of spontaneously hypertensive rats. Mol Brain Res 95: 48–54, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Liu JL, Irvine S, Reid IA, Patel KP, Zucker IH. Chronic exercise reduces sympathetic nerve activity in rabbits with pacing-induced heart failure—a role for angiotensin II. Circulation 102: 1854–1862, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Liu JL, Kulakofsky J, Zucker IH. Exercise training enhances baroreflex control of heart rate by a vagal mechanism in rabbits with heart failure. J Appl Physiol 92: 2403–2408, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Lovick TA, Coote JH. Electrophysiological properties of paraventriculo-spinal neurones in the rat. Brain Res 454: 123–130, 1988 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Macias M, Nowicka D, Czupryn A, Sulejczak D, Skup M, Skangiel-Kramska J, Czarkowska-Bauch J. Exercise-induced motor improvement after complete spinal cord transection and its relation to expression of brain-derived neurotrophic factor and presynaptic markers. BMC Neurosci 10: 144, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Metra M, Dei Cas L. Role of exercise ventilation in the limitation of functional capacity in patients with congestive heart failure. Basic Res Cardiol 91, Suppl 1: 31–36, 1996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Middlekauff HR, Mark AL. The treatment of heart failure: the role of neurohumoral activation. Intern Med 37: 112–122, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Mueller PJ. Exercise training and sympathetic nervous system activity: evidence for physical activity dependent neural plasticity. Clin Exp Pharmacol Physiol 34: 377–384, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Mueller PJ. Exercise training attenuates increases in lumbar sympathetic nerve activity produced by stimulation of the rostral ventrolateral medulla. J Appl Physiol 102: 803–813, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Mueller PJ, Hasser EM. Putative role of the NTS in alterations in neural control of the circulation following exercise training in rats. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 290: R383–R392, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Nelson AJ, Juraska JM, Musch TI, Iwamoto GA. Neuroplastic adaptations to exercise: neuronal remodeling in cardiorespiratory and locomotor areas. J Appl Physiol 99: 2312–2322, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. O'Connor CM, Whellan DJ, Lee KL, Keteyian SJ, Cooper LS, Ellis SJ, Leifer ES, Kraus WE, Kitzman DW, Blumenthal JA, Rendall DS, Miller NH, Fleg JL, Schulman KA, McKelvie RS, Zannad F, Pina IL, Investigators HA. Efficacy and safety of exercise training in patients with chronic heart failure: HF-ACTION randomized controlled trial. JAMA 301: 1439–1450, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Opocher G, Markro F, Rocco S, Trevisan R, Fioretto P. Atrial natriuretic factor in hypertensive and normotensive insulin-dependent diabetics. J Hypertens 7: S236–S237, 1989 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Packer M. Neurohormonal interactions and adaptations in congestive heart failure. Circulation 77: 721–730, 1988 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Pascual-Leone A, Amedi A, Fregni F, Merabet LB. The plastic human brain cortex. Annu Rev Neurosci 28: 377–401, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Patel KP. Neural regulation in experimental heart failure. Baillieres Clin Neurol 6: 283–296, 1997 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Patel KP, Zhang K, Carmines PK. Norepinephrine turnover in peripheral tissues of rats with heart failure. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 278: R556–R562, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Patel KP, Zhang K, Kenney MJ, Weiss M, Mayhan WG. Neuronal expression of Fos protein in the hypothalamus of rats with heart failure. Brain Res 865: 27–34, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Patel KP, Zhang PL, Carmines PK. Neural influences on renal responses to acute volume expansion in rats with heart failure. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 271: H1441–H1448, 1996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Patel KP, Zhang PL, Krukoff TL. Alterations in brain hexokinase activity associated with heart failure in rats. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 265: R923–R928, 1993 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Pena LL, Apstein CS, Balady GJ, Belardinelli R, Chaitman BR, Dusch BD, Fletcher BJ, Fleg JL, Myers JN, Sullivan MJ. Exercise and hear failure—a statement from the American Heart Association Committee on Exercise, Rehabilitation, and Prevention. Circulation 107: 1210–1225, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Piepoli MF, Scott AC, Capucci A, Coats AJ. Skeletal muscle training in chronic heart failure. Acta Physiol Scand 171: 295–303, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Rastogi A, Fonarow GC. The cardiorenal connection in heart failure. Curr Cardiol Rep 10: 190–197, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Roveda F, Middlekauff HR, Rondon MU, Reis SF, Souza M, Nastari L, Barretto AC, Krieger EM, Negrao CE. The effects of exercise training on sympathetic neural activation in advanced heart failure: a randomized controlled trial. J Am Coll Cardiol 42: 854–860, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Schmidt B, DiMicco JA. Blockade of GABA receptors in the periventricular forebrain of anesthetized cats: effects on heart rate, arterial pressure and hindlimb vascular resistance. Brain Res 301: 111–119, 1984 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Schuman EM, Madison DV. Nitric oxide and synaptic function. Annu Rev Neurosci 17: 153–183, 1994 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Smith CJ, Sun D, Hoegler C, Roth BS, Zhang X, Zhao G, Xu XB, Kobari Y, Pritchard K, Jr, Sessa WC, Hintze TH. Reduced gene expression of vascular endothelial NO synthase and cyclooxygenase-1 in heart failure. Circ Res 78: 58–64, 1996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Sole MJ, Hussain MN, Versteeg DHG, Ronald de Kloet ER, Adams D, Lixfeld W. The identification of specific brain nuclei in which catecholamine turnover is increased by left ventricular receptors during acute myocardial ischemia in the rat. Brain Res 235: 315–325, 1982 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Sole MJ, Versteeg DHG, Ronald de Kloet ER, Hussain MN, Lixfeld W. The identification of specific serotonergic nuclei inhibited by cardiac vagal afferents during acute myocardial ischemia in the rat. Brain Res 265: 55–61, 1983 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Stumpe KO, Zolle H, Klein H, Kruck F. Mechanism of sodium and water retention in rats with experimental heart failure. Kidney Int 4: 309–317, 1973 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Trejo JL, Carro E, Torres-Aleman I. Circulating insulin-like growth factor I mediates exercise-induced increases in the number of new neurons in the adult hippocampus. J Neurosci 21: 1628–1634, 2001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Vahid-Ansari F, Leenen FH. Pattern of neuronal activation in rats with CHF after myocardial infarction. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 275: H2140–H2146, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Vicini S, Ortinski P. Genetic manipulations of GABAA receptor in mice make inhibition exciting. Pharmacol Ther 103: 109–120, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Voss MW, Prakash RS, Erickson KI, Basak C, Chaddock L, Kim JS, Alves H, Heo S, Szabo AN, White SM, Wojcicki TR, Malley EL, Gothe N, Nlson EA, McAuley E, Kramer AF. Plasticity of brain networks in a randomized intervention trial of exercise training in older adults. Front Aging Neurosci 26: 32, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Wang HJ, Zhang F, Zhang Y, Gao XY, Wang W, Zhu GQ. AT1 receptor in paraventricular nucleus mediates the enhanced cardiac sympathetic afferent reflex in rats with chronic heart failure. Auton Neurosci 121: 56–63, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Wielenga RP, Coats AJS, Mosterd WL, Huisveld IA. The role of exercise training in chronic heart failure. Heart 78: 431–436, 1997 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Yamazato M, Yamazato Y, Sun C, Diez-Freire C, Raizada MK. Overexpression of angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 in the rostral ventrolateral medulla causes long-term decrease in blood pressure in the spontaneously hypertensive rats. Hypertension 49: 926–931, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Zhang K, Li YF, Patel KP. Blunted nitric oxide-mediated inhibition of renal nerve discharge within PVN of rats with heart failure. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 281: H995–H1004, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Zhang K, Li YF, Patel KP. Reduced endogenous GABA-mediated inhibition in the PVN on renal nerve discharge in rats with heart failure. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 282: R1006–R1015, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Zhang K, Mayhan WG, Patel KP. Nitric oxide within the paraventricular nucleus mediates changes in renal sympathetic nerve activity. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 273: R864–R872, 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Zhang K, Zucker IH, Patel KP. Altered number of diaphorase (NOS) positive neurons in the hypothalamus of rats with heart failure. Brain Res 786: 219–225, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. Zhang ZH, Francis J, Weiss RM, Felder RB. The renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system excites hypothalamic paraventricular nucleus neurons in heart failure. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 283: H423–H433, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. Zhao G, Hintze TH, Kaley G. Neural regulation of coronary vascular resistance: role of nitric oxide in reflex cholinergic coronary vasodilation in normal and pathophysiologic states. EXS 76: 1–19, 1996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80. Zheng H, Li YF, Zucker IH, Patel KP. Exercise training improves renal excretory responses to acute volume expansion in rats with heart failure. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 291: F1148–F1156, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81. Zheng H, Li YF, Cornish KG, Zucker IH, Patel KP. Exercise training improves endogenous nitric oxide mechanisms within the paraventricular nucleus in rats with heart failure. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 288: H2332–H2341, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82. Zheng H, Li YF, Wang W, Patel KP. Enhanced angiotensin-mediated excitation of renal sympathetic nerve activity within the paraventricular nucleus of anesthetized rats with heart failure. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 297: R1364–R1374, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83. Zucker IH, Wang W, Brändle M, Schultz HD, Patel KP. Neural regulation of sympathetic nerve activity in heart failure. Prog Cardiovasc Dis 37: 397–414, 1995 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]