Abstract

Objectives

The purpose of this systematic literature review is to examine the current state of knowledge regarding the return-to-work outcomes of sickness absences related to mental disorders that increase costs borne by employers. We address two questions: (1) Based on the existing literature, from the employer's perspective, what are the relevant economic return-to-work outcomes for sickness absences related to mental disorders? and (2) From the employer's economic perspective, are there gaps in knowledge about the relevant return-to-work outcomes for sickness absences related to mental disorders?

Setting

The included studies used administrative data from either an employer, insurer or occupational healthcare provider.

Participants

Studies included working adults between 18 and 65 years old who had a sickness absence related to a mental disorder.

Primary and secondary outcome measures

The studies considered two general return-to-work outcome categories: (1) outcomes focusing on return-to-work and (2) outcomes focusing on sickness absence recurrence.

Results

A total of 3820 unique citations were identified. Of these, 10 studies were identified whose quality ranged from good to excellent. Half of the identified studies came from one country. The studies considered two characteristics of sickness absence: (1) whether and how long it took for a worker to return-to-work and (2) sickness absence recurrence. None of the studies examined return-to-work outcomes related to work reintegration.

Conclusions

The existing literature suggests that along with the incidence of sickness absence related to mental disorders, the length of sickness absence episodes and sickness absence recurrence (ie, number and time between) should be areas of concern. However, there also seems to be gaps in the literature regarding the work reintegration process and its associated costs.

Keywords: MENTAL HEALTH, OCCUPATIONAL & INDUSTRIAL MEDICINE

Strengths and limitations of this study.

Few studies have examined the current state of knowledge about sickness absence outcomes from the employer perspective; this paper examines the current state of knowledge regarding the return-to-work outcomes of sickness absences related to mental disorders that increase workplace burdens from the perspective of the employer.

This systematic literature review employed a broad search of five electronic databases: (1) Medline Current, (2) Medline In-process, (3) PsycINFO, (4) Econlit and (5) Web of Science. A manual search was also conducted. In total, 3820 unique citations were identified and reviewed by two reviewers.

All included studies were based on data from complete populations of people who had a sickness absence; this minimises the potential for selection bias within populations.

The results of this review suggest that along with the incidence of sickness absence related to mental disorders, the length and sickness absence recurrence (ie, frequency of sickness absence recurrence and time between sickness absence episodes) of these sickness absences should be areas of concern and future research. This highlights the importance of evaluating interventions with respect to these two aspects of sickness absences rather than focusing solely on whether or not a worker returns to work.

The results of the search identified 10 papers that met inclusion criteria; this suggests that we are in the early stages of understanding the aspects of sickness absences that contribute to their burden and the areas to target to effectively decrease their costs.

Around the world, there is increasing awareness about the economic costs of mental disorders. Estimates suggest that a large share of the burden of mental disorders can be attributed to work productivity losses. Between 30% and 60% of depression's cost is related to losses associated with decreased work productivity.1 2 Decreased work productivity has been measured as work absences or an unproductive work day.

Owing to the fact that they take a societal perspective, most of the economic burden estimates for mental disorders rely on survey data (eg, 1 3 4). One of the most identifiable types of work absences is related to sickness absences. Yet, few estimates specifically have taken sickness absences into account. Sickness absences are defined as work absences that require a medical certification and have an associated income replacement benefit. The costs of these specific types of absences are not only borne by society but employers in particular. Furthermore, because they involve the workplace, employers often assume the costs and responsibilities for implementing the interventions to address sickness absences. Thus, to effectively build the business case for employers to invest in interventions that target sickness absences related to mental disorders, it is important to identify the costs that employers recognise and directly bear. By using a comprehensive estimate of costs in economic evaluations and economic models we could more accurately estimate the types of cost savings that employers can expect with an intervention.

The concern among employers regarding mental disorders has been fuelled by the recognition that sickness absence episodes related to a mental disorder are costly and their incidence is steadily rising.5 Estimates suggest that an episode related to a mental disorder can be double the cost of one related to a physical disorder.6 The calculation of the cost of sickness absences related to mental disorders is comprised of two types of factors: (1) the number of days absent and (2) the total number of sickness absences. It can be expected that the more sickness absence days, the greater the total cost of the sickness absence. In addition, high costs could be incurred with short sickness episodes if there are many repeat sickness episodes.

One approach to addressing the costs of sickness absence related to mental disorders could be to decrease the impact of the number of episodes and their lengths. This suggests that interest should extend beyond merely whether or not a worker returns-to-work. Rather, it is also important to understand the length and the frequency of sickness absence related to mental disorders. Few studies have examined the current state of knowledge about sickness absence outcomes from the employer perspective. To fill this gap, we conducted a systematic literature review to examine the sickness absence outcomes reported in the literature. These outcomes could help to identify the aspects of sickness absences that contribute to employer economic burdens.

Purpose of the paper

The purpose of this paper is to examine the current state of knowledge regarding the return-to-work (RTW) outcomes of sickness absences related to mental disorders that increase workplace burdens from the perspective of the employer. The question that we addressed in this systematic review was, ‘Based on the existing literature, from the employer's perspective, what are the relevant economic return-to-work outcomes for sickness absences related to mental disorders?’ Answers to this question can highlight the aspects of sickness absences related to mental disorders that could escalate the costs that employers face. Results of this review can point to areas that sickness absence interventions could target. They can also suggest dimensions along which future intervention effectiveness could be evaluated.

A secondary question we asked was, ‘From the employer's economic perspective, are there gaps in knowledge about the relevant return-to-work outcomes for sickness absences related to mental disorders?’ In answering this question, this review takes a first step in understanding where the knowledge in this area is and is not being produced. It also suggests areas where additional study is needed to more accurately estimate the costs of sickness absences borne by employers.

Methods

This systematic literature review used publically available peer-reviewed studies. It neither involved the collection of nor the use of primary data. As such, it was not subject to research ethics board review.

Five electronic databases were searched for this systematic literature review: (1) Medline Current (an index of biomedical research and clinical sciences journal articles), (2) Medline In-process (an index of biomedical research and clinical sciences journal articles awaiting indexing into Medline Current), (3) PsycINFO (an index of journal articles, books, chapters and dissertations in psychology, social sciences, behavioural sciences and health sciences), (4) Econlit (an index of journal articles, books, working papers and dissertations in Economics) and (5) Web of Science (an index of journal articles, editorially selected books and conference proceedings in life sciences and biomedical research). A search strategy was developed and executed for each database with a professional health science librarian (SB) (see online supplementary File 1—Search Strategy). Medline Current, Medline In-process and PsychINFO were searched using the OVID platform. Econlit and Web of Science were searched using the ProQuest and Thomson Reuters search interface, respectively. The search was completed between February 2013 and March 2013 and was limited to English language journals published between 2002 and 2013.

Eligibility criteria

The systematic literature search focused on the RTW outcomes of sickness absences of workers with medically certified sickness absences related to mental disorders. Sickness absence encompassed sick leave, short-term disability leave and long-term disability leave. These sickness absence benefits could be either publicly or privately sponsored. Their receipt was conditional on employment and the absence benefit was claimed with the intention of continued employment. We included studies that looked at ‘no cause’ sickness absences such that it was not compulsory that the absence was work-related. The search focused on identifying articles about working adults between 18 and 65 years old who had a sickness absence related to a mental disorder. Sickness absence outcome terms (ie, length of sickness absence, RTW, etc) were not included in the search strategy. This was performed to ensure all reported sickness absence outcomes in the literature would be captured. The reference lists of relevant studies were manually searched. Intervention studies, review articles and commentaries were excluded.

A multiphase screening process was employed. The first phase involved screening titles. Citations that passed the first phase were evaluated for relevance based on their abstracts. Finally, those that passed the abstract screen were evaluated for content based on the full-text. The multiphase screening process was completed independently by two reviewers, CSD and DL. The chance agreement corrected inter-rater reliability was 0.92. Articles for which there were rater disagreements were discussed until consensus was reached.

The following eligibility criteria were used in each phase:

The study reported on medically certified sickness absences due to mental disorders.

The study sample is not from a select (ie, clinical trial) population.

The study analysed data that were collected in the year 2000 or later.

The study reported on sickness absence outcomes directly related to a specific absence.

Sickness absence outcomes considered for this review included length of sickness absence, not returning to work (ie, quitting, retiring), transitioning to long-term disability, RTW and sickness absence recurrence.

Owing to the fact that the 1990s was a period of global change in disability policies and accounting for publication lag, the year 2002 was used as an inclusion starting point.7 We focused on the last decade because there were relatively fewer policy changes related to workers during this time. Studies using pre-2000 data were excluded because pre-2000 data were collected within systems that existed before many of the 1990s policy changes.

Quality assessment

Articles that passed the three-stage screening process were then assessed for quality using the following criteria:

The study population is well described.

The data source is well described.

The study sample is representative of all workers in the context.

Mental disorders are included and reported.

The system of diagnosis/classification is described.

The sickness absence criteria are reported (ie, presickness absence days to qualify for sickness absence).

Sickness absence outcome measures are defined.

Analytical methods are described.

Uncertainty of estimates are reported.

The stated research objective is met.

One point was awarded for each criterion that was met; the maximum score was 10. Total scores between 1 and 4 points were categorised as fair/weak quality, those between 5 and 8 points were good and those between 9 and 10 points were excellent quality.

Results

Description of inclusion and exclusion

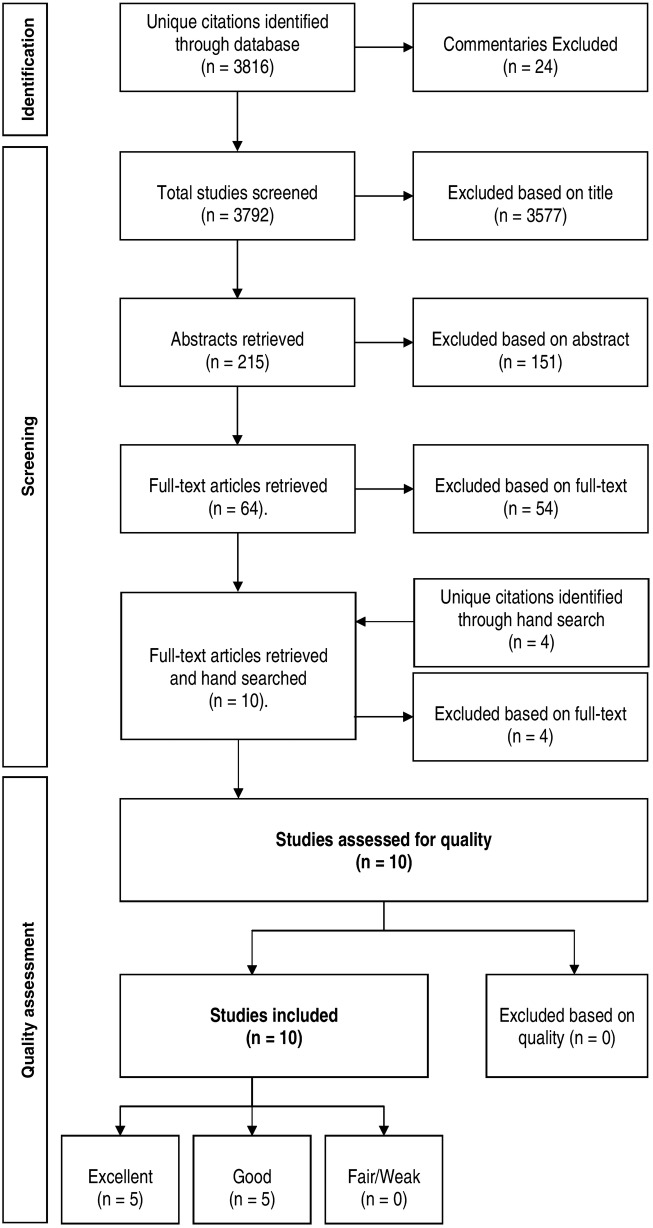

The electronic literature search resulted in the identification of 3820 unique citations (figure 1). From these, 24 entries that were commentaries were excluded. Based on the title review, 3577 citations were excluded. During the abstract review, another 151 citations were excluded; this left 64 articles for full-text review. After the full-text review, 10 articles remained and their reference lists were manually searched for relevant studies. Four articles were identified in the manual search process but all were excluded during full-text review. Reasons for article exclusions were because they: (1) used pre-2000 data (n=11), (2) did not report sickness absence outcomes directly related to a specific absence (n=3), (3) were based on select populations (n=44).

Figure 1.

Flowchart of literature search results and inclusions/exclusions.

Quality assessment

On quality assessment, 5 of the 10 studies were rated as excellent and the remaining 5 as good (see online supplementary File 2—Quality assessment). The identified limitations of these studies included: non-representativeness of the working population (n=10), outcome measure not defined (n=4), and uncertainty of the estimate not reported (n=3).

Overview of the studies

Table 1 contains the descriptions of the included studies. All of the included studies used administrative data from either an employer, insurer or occupational healthcare provider. As a result, none of the studies relied on self-report. They were based on objective data to identify populations of people with a sickness absence.

Table 1.

Overview of studies

| Author(s) | Country | Study population | Data source(s) | Years of data | Diagnostic classification system used | Sickness absence benefit definition | Outcomes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Barbosa-Branco et al14 | BR | All employees in registered private sector jobs in 2008 who had a sickness absence | Brazilian National Social Security Administrative Databases: National Benefits System and National Social Information Database | 2008 | International Classification of Diseases,10th edition (ICD-10) | Sickness absence = ≥15 medically certified consecutive days absent | Duration of sickness benefit claim (calendar vs work days not specified) |

| Board and Brown13 | UK | Study sample consisted of all employees of one police force who had ≥1 episode of long-term sickness absence (LTSA) between Nov 1, 2000 and Oct 31, 2002 | Employer electronic absenteeism record administrative data | 2000–2002 | International Classification of Diseases,8th edition (ICD-8) | Long-term sickness absence = medically certified sickness absence episodes ≥28 consecutive calendar days | Return to work by type of sickness absence episode (subacute or chronic) |

| Dewa et al6 | CA | Employees from one large resource sector company from 2003–2006 who had a sickness absence | Employer administrative sickness absence data | 2003–2006 | ICD-10 | Sickness absence = medically certified sickness absence of ≥5 continuous work days | Mean work days per sickness absence episode |

| Dewa et al12 | CA | Employees from one large resource sector company from 2003–2006 who had a sickness absence | Employer administrative sickness absence data | 2003–2006 | ICD-10 | Sickness absence = medically certified sickness absence of ≥5 continuous work days | Sickness absence free days |

| Koopmans et al15 | NL | Employees of firms who were clients of one occupational health services provider from April 2002—November 2005 who had a sickness absence | Administrative sickness absence data from one occupational health service provider (ArboNed) | 2002–2005 | Not described | Not described | Return to work Duration of absence calendar days |

| Koopmans et al9 | NL | Dutch Post and Telecommunication employees from 2001–2007 who had a sickness absence due to a common mental disorder since Jan 1 2001 or date of employment | Administrative sickness absence data from one occupational health service provider (ArboNed) | 2001–2007 | ICD-10 | Sick leaves of >3 weeks require a medical certificate from an occupational physician | Duration of sickness absence days (calendar vs work days not specified) Days to sickness absence recurrence |

| Koopmans et al8 | NL | Dutch Post and Telecommunication employees from 2001–2007 who had a sickness absence due to a common mental disorder | Administrative sickness absence data from one occupational health service provider (ArboNed) | 2001–2007 | ICD-10 | Sick leaves of >3 weeks require a medical certificate from an occupational physician |

Duration of sickness episodes Median duration in months until recurrence of sickness absence Days to sickness absence recurrence Recurrence = the start of at least one new episode of sickness absence after complete return to work for ≥28 days |

| Reis et al11 | BR | Workers who worked ≥20 h/week from one university hospital who were employed from 2000–2007 who had at least 1 sickness absence | Administrative data from employer human resources department | 2000–2007 | ICD-10 | Not described | Median calendar days per sickness absence Recurrence density of sickness absence episodes/100 worker-months |

| Roelen et al16 | NL | Employees of firms who were clients of an occupational health services provider from 2001–2007 who had a sickness absence | Administrative sickness absence data from one occupational health service provider (ArboNed) | 2001–2007 | ICD-10 | Sickness absence: absence of ≥28 sick days requiring a medical certificate from an occupational physician | Median number of calendar days of sickness absence episodes/100 employees |

| Roelen et al10 | NL | Dutch Post and Telecommunication employees from 2001–2007 who had a sickness absence | Administrative sickness absence data from one occupational health service provider (ArboNed) | 2001–2007 | ICD-10 | Sick leaves of >3 weeks require a medical certificate from an occupational physician |

Median duration of sickness absence in days (type of day not specified) Recurrence density of sickness absence/1000 worker-years Days to recurrence |

Of the 10 included studies, five were from the Netherlands. Two were from Brazil, two were from Canada and another from the UK. Seven of the studies used data from single employers. The employers in the studies represented a variety of sectors in several countries including a Dutch national postal service and a telecommunication company,8–10 a Brazilian hospital,11 a Canadian resource sector organisation6 12 and a British police force.13 The four exceptions were Barbosa-Branco et al14 whose study included all Brazilian workers in registered private sector companies. In addition, Koopman et al15 and Roelen et al16 based their studies on data from an occupational health provider representing a broad spectrum of firms across the Netherlands.

All of the studies except one indicated that they used the International Classification of Diseases (ICD) to identify type of disorder. Of those that used the ICD, eight of the studies were based on the 10th edition and one on the 8th edition. One study15 did not describe the disorder classification system it employed. However, because it used ArboNed data that were also used by Roelen et al,16 it might be assumed that ICD codes were also used in this study.

Among the studies, there was variability in the scope of the primary diagnoses associated with the sickness absences that were included. However, there were similarities with respect to the inclusion of depressive and anxiety disorders and stress-related disorders. Thus, there appeared to be consistency among the studies with regard to a core set of mental disorders.

There was variation with regard to the number of absence days needed to qualify for sickness absence benefits. The number of days ranged from 1 to 3 weeks.

Sickness absence outcomes

The outcomes reported by the studies could be grouped into two general categories. The first outcome category includes studies that examined whether and when a worker returned to work. They included RTW indicators and sickness absence duration. The second category of outcomes focused on sickness absence recurrence. These recurrence outcomes reflected the rates of sickness absence recurrence as well as the time between sickness absence episodes.

Outcomes focusing on RTW

Three studies reported the rates of RTW (table 2). Koopmans et al15 observed that of workers who had sickness absences due to depression, 66% returned to work within a year. Board and Brown13 found that among their police force, 85% of police officers who had a sickness absence returned to work.

Table 2.

Return-to-work sickness absence outcomes

| Author(s) | Country | Mental disorders | Outcome measure | Number of episodes or employees | Reported outcomes of sickness absences |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Barbosa-Branco et al14 | BR | Mental and behavioural disorders: Organic disorders (ICD-10 F00-F09); psychoaffective substance use disorders (ICD-10 F10-F19); schizophrenia, schizotypal and delusional disorders (ICD-10 F20-F29); mood disorders (ICD-10 F30-F39); stress-related and somatoform disorders (ICD-10 F40-F48) | Duration of sickness benefit claim = measure not described | Number of claims due to mental and behavioural disorders: All=147 105 Males=71 195 Females=75 910 |

Median duration of disability episodes (in days) (1st and 3rd quartiles): Males: Mental and behavioural disorders=76 (47, 113) Females: Mental and behavioural disorders=65 (43, 97) |

| Board and Brown13 | UK | ICD categories used not described | Absence phase: Subacute=28–90 days Chronic phase=>90 days Return-to-Work=episode has start and finish dates before study end date |

Number of sickness absences: Police officers=4485 Civilian staff=1761 |

Among those with mental ill health: Police officers: With subacute episode=43.2% With chronic episode=56.8% Who return to work=85.2% Civilian staff: With subacute episode=59.5% With chronic episode=40.5% Who return to work=Not reported |

| Dewa et al6 | CA (Ontario) | Mental and behavioural disorders (ICD-10 F00-F99, Z502, Z503, Z561-Z566, Z630-Z639, Z729, Z733, Z738, Z864, Z915): schizophrenia, mood disorders, stress-related disorders and mental and behavioural disorders due to psychoactive substance use | Duration of episode=number of work days absent | Number of sickness absences: Due to any disorder=4791 Due to mental and behavioural disorders=698 |

Mean days per episode (in days) (95%CI): Due to any disorder=33.0 (31.3 to 34.7) Due to mental and behavioural disorders: All=64.9 (58.2 to 71.6) Males=62.1 (54.1 to 70.1) Females=70.0 (57.8 to 82.1) |

| Koopmans et al15 | NL | Depression (diagnostic classification system not descripted in paper) | Duration of episode=number of calendar days between first day of sick leave and date of return to work or disability pension received | Number of new episodes due to depression=9910 | Return to work within a year: Men=67.7% Women=64.8% Total=66.2% One year of work incapacity: Men=15.2% Women=17.4% Total=16.4% Mean duration of episode (in days) (95% CI): Men=200 (196 to 204) Women=213 (210, 217) Median duration of episode (in days) (95% CI): Men=179 (172 to 186) Women=201 (193 to 209) |

| Koopmans et al9 | NL | Common mental disorders (CMD) from medical certification: stress-related (distress and adjustment disorders) (ICD-10 R45, F43) and psychiatric (mild to moderate depressive and anxiety disorders) (ICD-10 F32.0, F32.1, F40.0, F40.1, F40.2, F41.0, F41.1, F41.2, F41.3) | Duration of sickness absence=number of calendar days between first day of sick leave and date of return to work or disability pension received | Number of employees with ≥1 sickness absence due to CMD=8951 Total number of sickness absence due to CMD=10 921 |

From 2001 to 2007, median duration of index sickness absence episode (in days) (95% CI): Men: Stress=49 (47 to 51) Psychiatric=168 (150 to 186) Total CMD=57 (54 to 60) Women: Stress=56 (53 to 59) Psychiatric=168 (151 to 185) Total CMD=67 (63 to 71) From 2001–2007, median duration of recurrent CMD sickness absence episodes (in days) (95% CI): Men: Stress=46 (41 to 51) Psychiatric=68 (39 to 97) Total CMD=48 (43 to 53) Women: Stress=60 (51 to 69) Psychiatric=73 (53 to 93) Total CMD=62 (55 to 69) |

| Koopmans et al8 | NL | Common mental disorders (CMD) from medical certification: stress-related (distress and adjustment disorders) (ICD-10 R45, F43) and psychiatric (mild to moderate depressive and anxiety disorders) (ICD-10 F32, F40, F41) | Duration of sickness absence=number of calendar days of sickness absence adjusted for partial return to work and annual worker-years | Number of employees with ≥1 sickness absence due to CMD=9904 Total number of sickness absences due to CMD=12 404 |

From 2001 to 2007, duration of sickness absence episode due to CMD (in calendar days) (95% CI): Total=62 (60 to 64) Men=57 (55 to 59) Women=68 (65 to 71) |

| Reis et al11 | BR | Mental and behavioural disorders (ICD-10 F00-F99) | Duration of episode=Number of calendar days absent from work | Number of sickness absence episodes: Due to any disorder=5138 Due to mental and behavioural disorders=324 |

Median duration of sickness absence leave (in days): First episode: Due to any disorder=2 Due to mental and behavioural disorders=5 Recurrent episodes: Due to any disorder=2 Due to mental and behavioural disorders=7 |

| Roelen et al16 | NL | Mental and behavioural disorders (ICD-10 R45, F43, F32, F40 and F41) from medical certification: emotional disturbance, depressive disorders, anxiety disorders and stress-related disorders | Duration of sickness absence=calendar days between the first and last day of sickness absence |

Number of sickness absence episodes: Due to any disorder: 2001=90 095 2002=104 193 2003=118 926 2004=129 024 2005=128 044 2006=108 901 2007=96 482 Due to mental and behavioural disorders: 2001=21 140 2002=22 803 2003=24 917 2004=27 533 2005=22 682 2006=20 013 2007=18 513 |

Median duration of sickness absence episodes (in days) (95% CI): Due to any disorder: 2001=73 (72 to 74) 2002=63 (62 to 64) 2003=57 (56 to 58) 2004=53 (53 to 53) 2005=45 (45 to 45) 2006=49 (48 to 50) 2007=55 (54 to 56) Due to mental and behavioural disorders: 2001=119 (116 to 122) 2002=98 (96 to 100) 2003=87 (85 to 89) 2004=80 (79 to 81) 2005=79 (77 to 81) 2006=83 (81 to 85) 2007=87 (85 to 89) |

| Roelen et al10 | NL | Mental and behavioural disorders (ICD-10 F00-F99) from medical certification |

Duration of sickness absence=number of days between first day of sick leave and date of return to work or disability pension received |

Number of employees with ≥1 sickness absence=36 342 Number of employees with ≥1 sickness absence due to mental and behavioural disorders=7197 Number of employees with >1 sickness absence due to mental and behavioural disorders=1400 Worker-years=363 461 |

Median duration of sickness absence (in days) (95% CI): Mental and behavioural disorders=62 (55 to 69) Any disorder=35 (34 to 36) |

Duration of sickness absence

Duration of sickness absence was measured using three types of days—calendar days, work days and unspecified types of days. Sickness absence days were reported using two statistics—the mean days and the median days. The values of the mean and the median become equivalent when a distribution is symmetric (eg, the normal distribution). From the Netherland studies, the median days of absence duration were between 79 and 119 days.8–10 15 16 In addition, there were changes in the median number of days over time such that they seemed to decrease between 2001 and 2007.16 From Brazil, Reis et al11 reported a duration of 5–7 calendar days. Using Canadian data, Dewa et al6 reported a mean absence episode of 65 work days. From the UK, Board and Brown13 found that 43–60% of the workers they observed had a sickness absence episode that was between 28–90 days; about 41–57% had sickness absence episodes that lasted more than 90 days.

Four of the studies compared sickness absence episode duration for those related to mental disorders versus those for other disorders. The findings among the four studies were consistent; episodes for mental disorders were longer than episodes related to other types of disorders. For instance, Roelen et al10 reported that while the median duration of a mental disorder related episode was 62 days, it was 35 days for any type of episode. In addition, this pattern appeared to be consistent from 2001 to 2007.16 Among their Canadian energy sector workers, Dewa et al6 found that the mean number of work days of an episode related to a mental disorder was almost double that of an episode related to other types of disorders (65 days vs 33 days). Reis et al11 reported similar patterns among their sample of Brazilian healthcare workers.

Outcomes focusing on sickness absence recurrence

Three of the studies reported rates of sickness absence recurrence related to a mental disorder (table 3). Roelen et al10 reported recurrence rates of 80/1000 worker-years for mental and behavioural disorders as opposed to 82/1000 worker-years for any disorder. Reis et al11 found rates of 7/100 worker-months for mental and behavioural disorders and 17/100 worker-months for any disorder. In addition, Koopmans et al9 observed mental disorder sickness absence recurrence rates of 76/1000 worker-years for men and 79/1000 worker-years for women. They also found that 18% of workers with at least one sickness absence episode had a recurrent episode.9

Table 3.

Recurrence sickness absence outcomes

| Author(s) | Country | Mental disorders | Outcome measure | Number of episodes or employees | Reported outcomes of sickness absences |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dewa et al12 | CA (Ontario) |

Mental and behavioural disorders (ICD-10 F00-F99, Z502, Z503, Z561-Z566, Z630-Z639, Z729, Z733, Z738, Z864, Z915): schizophrenia, mood disorders, stress-related disorders and mental and behavioural disorders due to psychoactive substance use | Disability free days=number of between end of first episode and beginning of subsequent episode | Number of employees with ≥1 sickness absence episode: Due to mental disorders=422 Due to physical disorders= 3171 |

Median disability free days (SE): Previous episode for mental disorders=673 (79.8) Previous episode for physical disorders=1053 (48.6) |

| Koopmans et al9 | NL | Common mental disorders (CMD) from medical certification: stress-related (distress and adjustment disorders) (ICD-10 R45, F43) and psychiatric (mild to moderate depressive and anxiety disorders) (ICD-10 F32.0, F32.1, F40.0, F40.1, F40.2, F41.0, F41.1, F41.2, F41.3) | Recurrence density=number of employees with recurrent episodes by the worker-years in the subpopulation of men and women with a previous episode of sickness absence due to a CMD New episodes=>28 days apart Worker-years=years of coverage from index episode to end of employment period |

Number of employees with ≥1 sickness absence due to CMD=8951 Total number of sickness absence due to CMD=10 921 |

From 2001 to 2007, episodes per worker with ≥ 1 sickness absence related to CMD: 1 episode = 82% 2 episodes= 14% 3 episodes= 3% ≥ 4 episodes = 1% From 2001 to 2007, CMD recurrence densities/1000 worker-years (95% CI): Men: Stress=74.4 (72.9 to 76.0) Psychiatric=83.8 (71.9 to 95.7) Total CMD=75.6 (70.7 to 80.4) Women: Stress=78.4 (75.9 to 80.9) Psychiatric=78.9 (64.1 to 93.7) Total CMD=78.5 (72.4 to 84.6) From 2001 to 2007, CMD sickness absence median time to onset recurrence (in months) (95% CI): Men: Stress=11 (11 to 13) Psychiatric=12 (8 to 15) Total CMD=11 (10 to 13) Women: Stress=11 (9 to 12) Psychiatric=10 (8 to 12) Total CMD=10 (9 to 12) |

| Koopmans et al8 | NL | Common mental disorders (CMD) from medical certification: stress-related (distress and adjustment disorders) (ICD-10 R45, F43) and psychiatric (mild to moderate depressive and anxiety disorders) (ICD-10 F32, F40, F41) | Recurrence density=number of employees with recurrent episodes by the worker-years in the subpopulation of men and women with a previous episode of sickness absence due to a CMD Worker-years=years of coverage from index episode to end of employment period |

Number of employees with ≥1 sickness absence due to CMD=9904 Total number of sickness absences due to CMD=12 404 |

From 2001 to 2007, CMD sickness absence median time to onset recurrence (in months) (95% CI): Total=10 (10 to 11) Distress symptoms=11 (10 to 12) Adjustment disorder=11 (9 to 12) Depressive symptoms=10 (7 to 12) Anxiety symptoms=10 (7 to 14) Other CMD disorders=8 (6 to 9) |

| Reis et al11 | BR | Mental and behavioural disorders (ICD-10 F00-F99) | Duration of episode=Number of calendar days absent from work Recurrence density=number of recurrent sickness absences divided by total worker-time at risk for the subsequent sickness absences |

Number of sickness absence episodes: Due to any disorder=5138 Due to mental and behavioural disorders=324 |

Recurrence density/100 worker-months: Due to any disorder =17.37 Due to mental and behavioural disorders=6.72 |

| Roelen et al10 | NL | Mental and behavioural disorders from medical certification (ICD-10 F00-F99) |

Recurrence density=number of employees with recurrent episodes by the worker-years in the subpopulation of men and women with a previous episode of sickness absence |

Number of employees with ≥1 sickness absence=36 342 Number of employees with ≥1 sickness absence due to mental and behavioural disorders=7197 Number of employees with >1 sickness absence due to mental and behavioural disorders=1400 Worker-years=363 461 |

From 2001 to 2007, Recurrence density/1000 worker-years (95% CI): Mental and behavioural disorders=80.4 (74.9 to 86.0) Any disorder=81.6 (79.1 to 84.0) Median days to recurrence (in days) (95% CI): Mental and behavioural disorders=328 (284 to 372) Any disorder=384 (367 to 401) |

Time between sickness absence episodes

Four studies reported the time between episodes related to mental disorders. Koopmans et al8 found that the median time was 10 months. In addition, Koopmans et al9 observed the median lengths of episode free-months were similar for men (11 months) and women (10 months).

Roelen et al10 compared lengths of episode free-days for those related to mental disorders versus those related to any disorder. They found the median length of episode free days was longer for workers who had a previous sickness absence episode for any disorder (384 days) versus those who had a previous episode related to a mental disorder (328 days). Dewa et al12 also observed a longer period of sickness absence free days for workers who had a previous sickness absence episode related to a physical disorder (1053 days) than those who had a previous sickness absence episode related to a mental disorder (673 days).

Discussion

Based on the existing literature, from the employer's perspective, what are the relevant economic RTW outcomes for sickness absences related to mental disorders? The results of the 10 studies could be grouped into two general outcome categories: (1) outcomes focusing on RTW and (2) outcomes focusing on sickness absence recurrence.

Two of the included studies that looked at RTW outcomes indicated that the majority of workers who have a sickness absence RTW at the end of the absence.13 15 This trend is consistent with early studies that indicated a large proportion of workers RTW at the end of their absence.17 18 This suggests that retention of workers may not be one of the major burdens associated with sickness absence. It also raises the question of what happens to workers who do not RTW at the end of their sickness absence. This is particularly salient for North American (ie, USA and Canada) employers who offer long-term work disability benefits to their workforces. Although a small group, workers who receive long-term disability benefits after reaching the limits of their sickness absence benefits could represent high costs. One estimate suggested that it could cost $C80 000 per long-term disability claim.5

The results of the studies suggest that sickness absence duration ranges from 5 to 119 days. The variation among the estimates may reflect the variation among the sickness benefit schemes of the jurisdictions in which the studies were conducted. However, there were consistencies among a number of reported patterns. For example, the numbers of sickness absence days related to mental disorders were greater than those for physical disorders in the four studies that reported them.6 9 14 15 In addition, compared to absences related to physical disorders, those related to mental disorders may be of greater length and in turn, burden.

With regard to sickness absence recurrence, the studies that calculated sickness absence recurrence rates reported rates that ranged from 7/100 worker months to 80/1000 worker-years. While there is variation in the magnitudes of the reported rates, two studies also indicated that the time between a sickness absence recurrence is consistently longer for workers who had a past sickness absence related to a physical disorder versus a mental disorder. However, while the pattern seemed to be consistent, the median numbers of sickness absence free days were two to three times greater in Dewa et al's12 study than Roelen et al's.10 Owing to the fact that workers within the respective studies are exposed to the same sickness benefit scheme, the differences within the studies suggest there may be other potential contributors to the differences than solely the sickness benefit scheme. There is an opportunity for future research to explore the role that individual (eg, the chronic nature of mental disorders), occupational (eg, job characteristics) and environmental (eg, workplace stigma) factors play in the differences in the recurrence of physical versus mental disorder-related sickness absences.

These results also suggest that although most workers RTW, they also may be at risk of a repeat sickness absence episode. Indeed, the literature suggests that mental disorders such as depression are chronic in nature and have a high recurrence rate.19–21 However, does symptom relapse automatically necessitate an accompanying sickness absence? Given that work disability is not solely a medical problem, there have been suggestions that the prognosis need not be fatalistic; sickness absence is not always required. For example, workplace accommodations could help workers experiencing an episode of mental illness continue to work during an episode.22 23 In addition, there is an emerging literature looking at the effectiveness of interventions in decreasing sickness absence recurrence for mental disorders.24 25 That is, although there have been arguments for treating mental disorders as chronic illnesses, there have been few intervention studies that have focused on decreasing sickness absence recurrence for mental disorders.

This also points to one of the gaps in the literature. Few studies have estimated the components of the cost of work reintegration and accommodation for workers with mental disorders. None of the studies identified in this review examined the time it took for a worker to completely reintegrate back into work. For example, how long is the work accommodation period? Furthermore, how is productivity affected during the reintegration period? There is evidence suggesting that there may be costs to the employer related to the process of reintegrating a worker who has been absent because of a sickness episode.22 26 27 There also is evidence to suggest that employers and workers have identified work sustainability without sickness absence recurrence as an important work outcome.28 Given that work sustainability without sickness absence recurrence seems to be a preference of workers and employees and there are potential costs related to reintegration and accommodation, it may be important to consider the number of episodes (ie, recurrence rates) as well as total number of absence days alone. Few burden of illness studies for mental disorders have included the costs of recurrent sickness absence in their estimates. However, recurrent sickness absence episodes seem to be a cost that warrants consideration for inclusion in cost estimates as well as for intervention outcomes.

In addition, five of the 10 studies identified are from one country (the Netherlands) and two population groups within that country. At the same time, the databases that were used represented between 10 000 and 100 000 claims. Thus, the findings that emerge from these databases build a compelling case that the length of sickness absence and its recurrence is a burden on employers. However, the fact that the majority of the evidence is being generated by one country raises interesting questions. Is the reason that the Netherlands and Northern Europe are the sources of most of the intervention studies for sickness absences related to mental disorders because they have compelling data to make the case about the costs to employers? Are the results from the Netherlands generalisable to other countries?

In addition to the Dutch studies, there were five other studies identified. However, these studies actually represented a total of four population groups. Three of the datasets each represented about 5000 claims from single organisations (the studies from the UK, Canada and one Brazilian study). The exception was the one Brazilian study that represented 140 000 claims (all workers in registered private sector jobs). This suggests that there is an opportunity for the evidence base to grow in these countries. It also begs the question, ‘What is known about the sickness absence burden in other countries that were not represented in this search (ie, the USA, the missing European Union countries and Asia)?’ Does the absence of studies from other countries indicate that it is not a concern in the other countries? Or, is it an indication that awareness is yet to be raised?

Strengths and limitations related to interpreting the literature

There were a number of strengths of the current body of literature reviewed. First, all of the data from the included studies used data from complete populations of people who had a sickness absence. This minimises the potential for selection bias within populations. However, selection bias related to the population chosen is still a possibility. Indeed, there was variation in the populations covered ranging from multiple to single organisations. Consequently, it will be important for future work to examine whether the results are generalisable to different populations.

An additional strength of the included studies was that they used standardised diagnostic classification systems. All included depressive and anxiety disorders as well as stress-related disorders. However, there was variability in the other types of mental disorders considered. This could have affected some of the reported results. At the same time, it should be noted that the majority of sickness absences related to mental disorders are attributable to depression, anxiety and stress-related disorders.29 30 This suggests that inclusion of these disorders would capture a large proportion of the sickness absences related to mental disorders.

A limitation of the studies was the variation in the years from which the data were taken. Although all studies used post-2000, there could have been changes within systems that could have affected incidence rates. For example, in the Netherlands, extensive legislative changes occurred between 2000 and 2013 which affected rates.7 31 In fact, the changes are reflected in the results reported by Roelen et al16 Similarly, changes could have been implemented in other countries such that results may not currently be generalisable.

Another limitation was variability in the sickness absence benefit schemes. That is, the variation in the length of sickness absence episodes in part could be related to the length of sickness absence coverage. The longer the coverage, the longer the absence may be. The frequency of sickness absence recurrence also could be affected by the benefit scheme. If there are limits on the number of sickness absence days that a worker is allowed annually, those workers could have fewer episodes than workers for whom limits do not exist.

Strengths and limitations of the search strategy

Although five databases were used in the search, articles that did not appear in any of the databases could have been overlooked. This possibility was decreased due to the broad scope of each of the searched databases and the manual search. Another limitation is related to the fact that the search focused on articles published in English-language journals. However, despite the English-language constraint, the identified studies originated in European, North American and Latin American countries. This indicates that although they are not in countries where English is the first language, at least some of these researchers publish in English-language journals.

It should be noted that the sickness absence outcomes that have been studied are related to the potential direct costs to employers. That is, because of the effect on work productivity, employers will be interested in the length of sickness absences as well as recurrence of sickness absence. However, from a societal perspective, this presents only part of picture. What happens to workers who do not RTW? This is a question governments may want answered especially if it means that those workers become enrolled in the public disability programmes.32 Thus, future work should also examine this group of workers particularly if factors can be identified that retain them in the labour market.

Conclusions

This systematic literature review identified only 10 studies published in the last decade. The results of these existing studies suggest that along with the incidence of sickness absence related to mental disorders, the length and recurrence (ie, frequency of recurrence and time between recurrence) of these sickness absences should be areas of concern.

This systematic review also highlights gaps in the literature. For instance, half of the existing studies are from the Netherlands. That is, most of the literature in this area is based on the Netherland's experience. This suggests that in other parts of the world, this area of research is in its infancy. It will be important for research in other countries to look at the length and sickness absence recurrence (ie, frequency of recurrence and time between recurrences) of sickness absences. This basic knowledge will help with understanding to what extent it should be a concern for employers in other countries. In turn, it could also help to build the business case for increased resources towards the development of more sickness absence interventions in these other countries.

The results of this review also indicate that we are in the early stages of understanding the aspects of sickness absences that contribute to employer burden and along the same vein, areas to target to effectively decrease costs. For example, more research is needed regarding the costs of recurrence including the cost of reintegration and time to full reintegration. This suggests that current cost estimates may underestimate the costs of sickness absences from the employer's perspective. To effectively build the business case for employers to invest in interventions that target sickness absences related to mental disorders, it will be important to develop a more comprehensive picture of the costs associated with sickness absence that employers directly bear. Only in this way can economic evaluations and economic models accurately estimate the types of cost savings that employers can expect with an intervention.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Contributors: CSD led the conception, design, data acquisition, analysis and interpretation of the data; she also led the writing of the overall manuscript. DL collaborated on the design, data acquisition and analysis; he contributed to the writing of the overall manuscript and led the writing of the Methods section. SB collaborated on the design and data acquisition and contributed to the writing of the manuscript. All authors are guarantors of the final manuscript.

Funding: This work was funded by CSD's Canadian Institutes of Health Research/Public Health Agency of Canada Applied Public Health Chair (FRN#:86895).

Competing interests: None.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

References

- 1.Greenberg PE, Leong SA, Birnbaum HG, et al. The economic burden of depression with painful symptoms. J Clin Psychiatry 2003;64(Suppl 7):17–23 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Stephens T, Joubert N. The economic burden of mental health problems in Canada. Chronic Dis Can 2001;22:18–23 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Greenberg PE, Sisitsky T, Kessler RC, et al. The economic burden of anxiety disorders in the 1990s. J Clin Psychiatry 1999;60:427–35 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Stewart WF, Ricci JA, Chee E, et al. Cost of lost productive work time among US workers with depression. [Erratum appears in JAMA. 2003 Oct 22;290(16):2218]. JAMA 2003;289:3135–44 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sairanen S, Matzanke D, Smeall D. The business case: collaborating to help employees maintain their mental well-being. Healthc Pap 2011;11:78–84 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dewa CS, Chau N, Dermer S. Examining the comparative incidence and costs of physical and mental health-related disabilities in an employed population. J Occup Environ Med 2010;52:758–62 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development. Transforming disability into ability: policies to promote work and income security for disabled people. OECD Publishing, 2003 [Google Scholar]

- 8.Koopmans PC, Bultmann U, Roelen CA, et al. Recurrence of sickness absence due to common mental disorders. Int Arch Occup Environ Health 2011;84:193–201 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Koopmans PC, Roelen CA, Bultmann U, et al. Gender and age differences in the recurrence of sickness absence due to common mental disorders: a longitudinal study. BMC Public Health 2010;10:426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Roelen CA, Koopmans PC, Anema JR, et al. Recurrence of medically certified sickness absence according to diagnosis: a sickness absence register study. J Occup Rehabil 2010;20:113–21 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Reis RJ, Utzet M, La Rocca PF, et al. Previous sick leaves as predictor of subsequent ones. Int Arch Occup Environ Health 2011;84:491–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dewa CS, Chen MC, Chau N, et al. Examining factors associated with the length of short-term disability-free days among workers with previous short-term disability episodes. J Occup Environ Med 2011;53:669–73 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Board BJ, Brown J. Barriers and enablers to returning to work from long-term sickness absence: part I-A quantitative perspective. Am J Ind Med 2011;54:307–24 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Barbosa-Branco A, Bultmann U, Steenstra I. Sickness benefit claims due to mental disorders in Brazil: associations in a population-based study. Cad Saude Publica 2012;28:1854–66 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Koopmans PC, Roelen CAM, Groothoff JW. Sickness absence due to depressive symptoms. Int Arch Occup Environ Health 2008;81:711–19 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Roelen CA, Koopmans PC, Hoedeman R, et al. Trends in the incidence of sickness absence due to common mental disorders between 2001 and 2007 in the Netherlands. Eur J Public Health 2009;19:625–30 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Conti DJ, Burton WN. The economic impact of depression in a workplace. J Occup Med 1994;36:983–8 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dewa CS, Goering P, Lin E, et al. Depression-related short-term disability in an employed population. J Occup Environ Med 2002;44:628–33 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Andrews G. Should depression be managed as a chronic disease? BMJ 2001;322:419–21 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Burcusa SL, Iacono WG. Risk for recurrence in depression. Clin Psychol Rev 2007;27:959–85 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kessler RC, Zhao S, Blazer DG, et al. Prevalence, correlates, and course of minor depression and major depression in the National Comorbidity Survey. J Affect Disord 1997;45:19–30 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gates LB. Workplace accommodation as a social process. J Occup Rehabil 2000;10:85–98 [Google Scholar]

- 23.Allen S, Carlson G. To conceal or disclose a disabling condition? A dilemma of employment transition. J Vocational Rehabil 2003;19:19–30 [Google Scholar]

- 24.Arends I, van der Klink JJ, van Rhenen W, et al. Prevention of recurrent sickness absence in workers with common mental disorders: results of a cluster-randomised controlled trial. Occup Environ Med 2014;71:21–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Martin MH, Nielsen MB, Madsen IE, et al. Effectiveness of a coordinated and tailored return-to-work intervention for sickness absence beneficiaries with mental health problems. J Occup Rehabil 2013;23:621–30 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Freeman D, Cromwell C, Aarenau D, et al. Factors leading to successful workplace integration of employees who have experienced mental illness. Employee Assistance Q 2004;19:51–8 [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tse S. What do employers think about employing people with experience of mental illness in New Zealand workplaces? Work 2004;23:267–74 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hees HL, Nieuwenhuijsen K, Koeter MWJ, et al. Towards a new definition of return-to-work outcomes in common mental disorders from a multi-stakeholder perspective. PLoS ONE 2012;7:e39947. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Henderson M, Glozier N, Holland Elliott K. Long term sickness absence. BMJ 2005;330:802–3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Roelen CA, Norder G, Koopmans PC, et al. Employees sick-listed with mental disorders: who returns to work and when? J Occup Rehabil 2012;22:409–17 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Schene A, Hees H, Koeter M, et al. Work, mental health and depression. Wiley-Blackwell, 2013 [Google Scholar]

- 32.Dewa CS, McDaid D, Ettner SL. An international perspective on worker mental health problems: who bears the burden and how are costs addressed? Can J Psychiatry 2007;52:346–56 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.