Abstract

DNA polymerase η (pol η) synthesizes past cyclobutane pyrimidine dimer and possibly 7,8-dihydro-8-oxoguanine (8-oxoG) lesions during DNA replication. Loss of pol η is associated with an increase in mutation rate, demonstrating its indispensable role in mutation suppression. It has been recently reported that β-strand 12 (amino acids 316–324) of the little finger region correctly positions the template strand with the catalytic core of the enzyme. The authors hypothesized that modification of β-strand 12 residues would disrupt correct enzyme–DNA alignment and alter pol η’s activity and fidelity. To investigate this, the authors purified proteins containing the catalytic core of the polymerase, incorporated single amino acid changes to select β-strand 12 residues, and evaluated DNA synthesis activity for each pol η. Lesion bypass efficiencies and replication fidelities when copying DNA-containing cis-syn cyclobutane thymine-thymine dimer and 8-oxoG lesions were determined and compared with the corresponding values for the wild-type polymerase. The results confirm the importance of the β-strand in polymerase function and show that fidelity is most often altered when undamaged DNA is copied. Additionally, it is shown that DNA–protein contacts distal to the active site can significantly affect the fidelity of synthesis.

Keywords: DNA damage, lesion bypass, mutagenesis, replication fidelity

INTRODUCTION

DNA polymerase η (pol η) functions to suppress mutations after exposure to ultraviolet light [Masutani et al., 1999a,b]. This is remarkable because its fidelity is low when copying DNA and bypassing the cyclobutane pyrimidine dimers (CPDs) created by UV exposure [Johnson et al., 2000; Matsuda et al., 2000, 2001; Washington et al., 2001; McCulloch et al., 2004b]. In addition to CPDs, biochemical studies demonstrate that pol η can bypass a variety of other lesions, for which the fidelity is varied and poor compared with that of replicative polymerases copying undamaged DNA [Masutani et al., 2000; Zhang et al., 2000]. For example, the in vitro error rate of pol η approaches 50% when replicating past 7,8-dihydro-8-oxoguanine (8-oxoG), a ubiquitous oxidative lesion, despite in vivo evidence that it suppresses mutations caused by the lesion [Zhang et al., 2000; Maga et al., 2007; Lee and Pfeifer, 2008; McCulloch et al., 2009].

High-quality crystal structures of yeast and human pol η bound to undamaged DNA as well as DNA-containing cis-syn thymine dimers or cisplatin adducts have recently been described and provide a basis for the proclivity of pol η to bypass lesions that stall other polymerases. Specifically, two structural attributes of pol η may contribute to the highly efficient bypass observed [Vaisman et al., 2000; McCulloch et al., 2004b]. First, the polymerase possesses a large catalytic center capable of accommodating two template bases simultaneously [Biertümpfel et al., 2010; Silverstein et al., 2010; Ummat et al., 2012a; Zhao et al., 2012]. High-fidelity polymerases are unable to accomplish this as they kink the phosphate backbone of template DNA 3′ to the template base [Beese et al., 1993; Sawaya et al., 1997; Doublie et al., 1998]. This action is impossible with the adjacent bases of CPDs and 1,2-intrastrand cisplatin lesions due to their crosslinked nature. Therefore, although these lesions are unsuitable substrates for the high-fidelity polymerases, they can be proficiently copied by pol η because of its expansive catalytic site. Second, several intramolecular and intermolecular forces throughout the catalytic core exist that provide pol η with the unique ability to straighten and maintain DNA in B-form conformation [Biertümpfel et al., 2010]. This buttressing action positions the 3′ hydroxyl so that it is ready for catalysis despite the presence of distortion-inducing lesions. Appropriately, Biertümpfel et al. described pol η as a “molecular splint” and linked several xeroderma pigmentosum variant (XPV) mutations to the disruption of this binding surface.

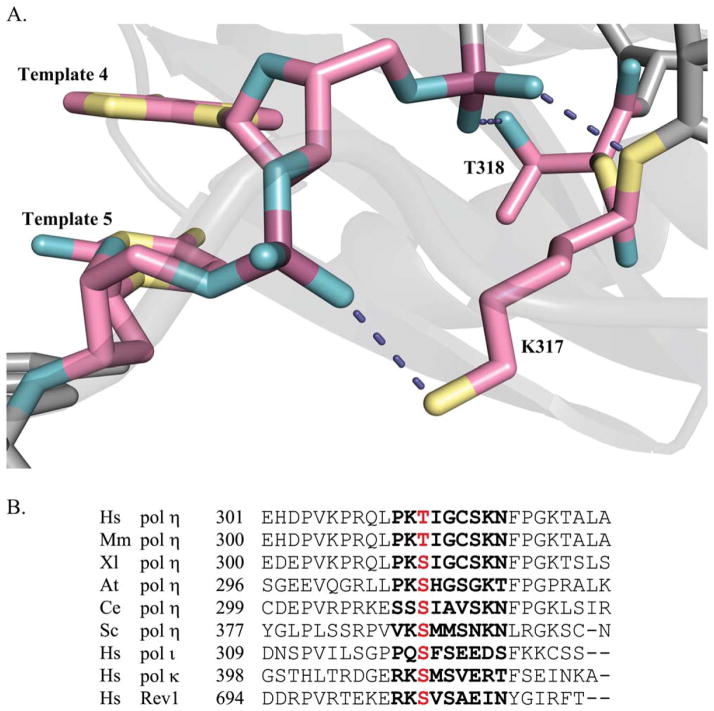

Human pol η β-strand 12, comprising amino acids 316–324, provides several important contacts that contribute to the splinting action of pol η [Boudsocq et al., 2002; Biertümpfel et al., 2010]. Located in the Y-family polymerase-specific little finger domain (also called the polymerase-associated domain) [Trincao et al., 2001], this β-strand is situated almost parallel to the template strand and helps to orient the DNA into the active site by extensively interacting with template strand DNA. Hydrogen bonds extend from both the hydroxyl group of Thr 318 and the amine group of Lys 317, as well as from main chain amide groups to DNA template phosphate residues [Biertümpfel et al., 2010]. These interactions reach to template strand DNA that has already been copied (Fig. 1A). In total, the pol η little finger β-strand has direct contact with five template strand bases of newly synthesized DNA downstream of the active site, indicating that it would interact with damaged bases even when the active site is 1–4 nucleotides upstream. We have previously shown the polymerase to preferentially dissociate from DNA two to four bases beyond a thymine dimer site after lesion bypass and proposed that this dissociation could be the result of a conformational change [McCulloch et al., 2004b]. This is now supported by structural data demonstrating that when the CPD is located at the -3 position, lesion-induced DNA distortion leads to steric clashing and hydrogen bond loss that may be responsible for the release of polymerase from DNA. These unpropitious interactions provide a mechanism for limiting the activity of such a low-fidelity enzyme during replication.

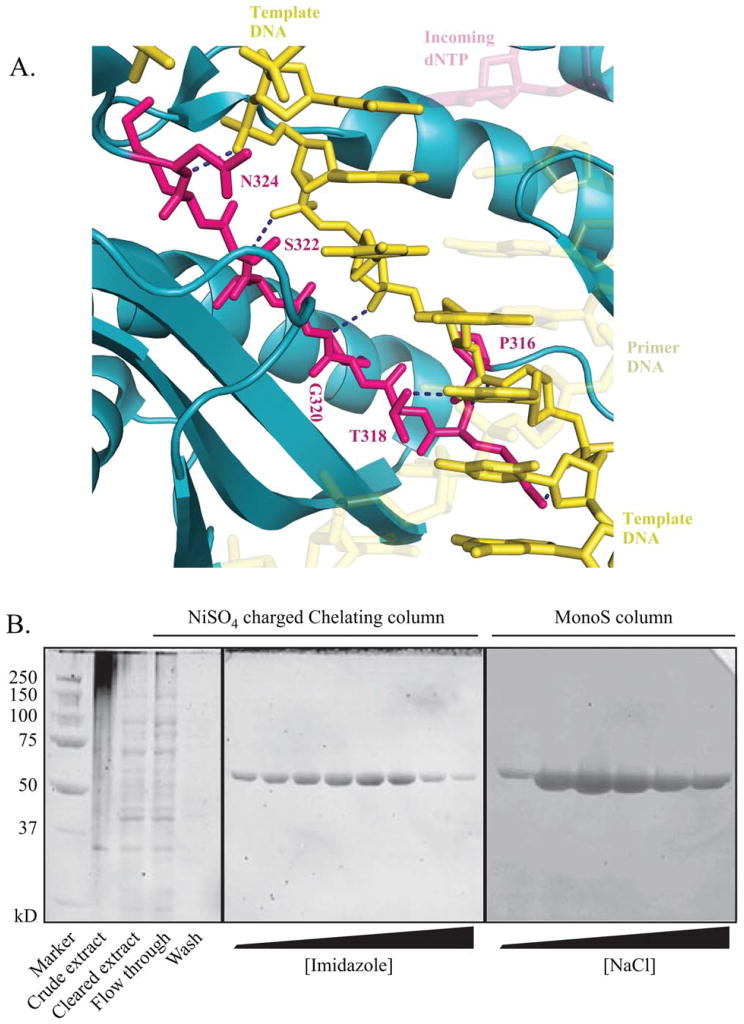

Fig. 1.

A: Magnified view of the little finger domain β-strand of human pol η in complex with undamaged DNA. The image was prepared from PDB entry 3MR2 [Biertümpfel et al., 2010] using the PyMOL Molecular Graphics System, Version 1.3 Schrödinger, LLC. Amino acid residues 316–324 are displayed in magenta, with remaining polymerase ribbon displayed in cyan. DNA template is displayed in yellow, incoming dNTP in transparent magenta, and the newly synthesized primer strand in transparent yellow. Hydrogen bonds are represented by dark blue dashed lines. B: Representative SYPRO-RED-stained SDS-PAGE gels from purification of E. coli-expressed proteins. Peak fractions eluted from a HiTrap™ Chelating HP (GE Healthcare (Little Chalfont, United Kingdom)) column using an imidazole gradient and from a Mono S™ (GE Healthcare (Little Chalfont, United Kingdom)) column using a NaCl gradient are shown. Protein fractions analyzed in gels were selected based on absorbance readings at 280 nm.

In addition to the interactions between the β-strand and template DNA, hydrogen bonds between Pro 316 and Arg 361 secure the position of the β-strand within the protein. The identification of an R361S missense mutation in a XPV patient highlights the significance of this interaction [Broughton et al., 2002]. Because of the apparent importance of β-strand 12 to polymerase function, we performed site-directed mutagenesis to modify several amino acids within this section of the pol η little finger domain. We studied the effect of these changes on polymerase activity and determined the lesion bypass efficiencies and fidelities of the mutated versions of the polymerase. We have used the results of these biochemical experiments to further characterize the relationship between the structure and function of pol η as well as to impart insight into the molecular mechanism by which pol η performs translesion synthesis (TLS).

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Materials

Reaction buffer for all assays consisted of 40 mM Tris (pH 8.0), 250 μg/mL bovine serum albumin, 10 mM dithiothreitol, 10 mM magnesium chloride, 60 mM potassium chloride, and 1.25% glycerol. Polymerase activity, lesion bypass efficiency, and reversion mutation assays were supplemented with all four dNTPs to a final concentration of 0.1 mM each. The gap-filling forward mutation assay was supplemented with each dNTP to a final concentration of 1.0 mM. All cell lines, bacteriophage, and reagents for lesion bypass fidelity and forward mutation assays have been previously described [Bebenek and Kunkel, 1995; McCulloch and Kunkel, 2006]. DNA sequencing was performed by Genewiz (South Plainfield, NJ). Oligonucleotides were purchased from Integrated DNA Technologies (Coralville, IA) and The Midland Certified Reagent Company (Midland, TX). Nucleotides and restriction enzymes were obtained from New England Biolabs (Ipswich, MA).

Expression and Purification of Pol η Little Finger β-Strand Mutants

The seven forms of pol η (wild type, P316A, T318A, G320A, G320P, S322A, and N324A) were overexpressed and purified as previously detailed [Suarez et al., 2013]. Briefly, the vector pET21b-XPV, which codes for the catalytic core amino acids 1–511 of human pol η and includes a C-terminal 6× histidine tag, was used. The truncated pol η catalytic core has been shown to retain the same TLS activity as the full-length polymerase [Kusumoto et al., 2002; Biertümpfel et al., 2010]. Amino acid substitutions were introduced by use of a QuikChange II XL Site-Directed Mutagenesis Kit (Agilent Technologies, Inc (Santa Clara, CA)) and targeted changes were validated by sequencing. Proteins were overexpressed in E. coli BL21(DE3) cells, and the protein product was purified by affinity chromatography using NiSO4-charged HiTrap™ Chelating HP (GE Healthcare (Little Chalfont, United Kingdom)) with subsequent application of pol η-enriched fractions to Mono S™ (GE Healthcare (Little Chalfont, United Kingdom)) as described [Suarez et al., 2013].

Measurement of Polymerase Activity

Polymerase activity assays were performed as previously described [McElhinny et al., 2007]. All reagents were prechilled to 4°C and maintained at 4°C throughout the assay. Reaction mixtures (60 μL) containing 1.5 μg-activated calf thymus DNA (GE Healthcare (Little Chalfont, United Kingdom)) and ~10 μCi 32P-α-dCTP (Perkin Elmer Inc. (Waltham, Massachusetts)) were initiated by the addition of 150 nM polymerase and incubated at 37°C for 30 min. About 11 μL aliquots of reaction mixture were terminated by the addition of an equal volume of 50 mM EDTA and 20 μg glycogen (Roche Diagnostics Corp. (Indianapolis, Indiana)). About 10 μL of stopped reaction mixture was processed in duplicate by the addition of 40 μL ultrapure water and 500 μL 10% trichloroacetic acid (TCA). After incubating on ice for 15 min, 500 μL of 5% TCA, 1% sodium pyrophosphate (NaPPi) solution was added, and the precipitate was collected by vacuum filtration through Whatman GF/C glass fiber filters that were presoaked in cold 5% TCA, 1% NaPPi. The precipitate was subsequently washed three times with 5 mL cold 5% TCA, 1% NaPPi and one time with 5 mL 95% cold ethanol by passing the wash solutions through the filters. The filters were removed and dried under a heat lamp. Liquid scintillation counting was used to quantify the amount of 32P-α-dCTP incorporated.

Measurement of Lesion Bypass Efficiency

Lesion bypass efficiency assays have been previously described in detail [Kokoska et al., 2003]. Two DNA lesions were assayed: cis-syn cyclobutane thymine–thymine dimer (TT dimer/TTD) and 8-oxoG. Substrates used for the bypass efficiency analysis were created by annealing a Cy5-labeled primer strand to a template strand (5′-Cy5-AATTTCTG-CAGGTCGACTCCAAAGGC-3′ to 5′-CCAGCTCGGTACCGGGTT AGCCTTTGGAGTCGACCTGCAGAAATT-3′ for TT/TT dimer reactions where the underlined TT is either a thymine pair or a TT dimer and 5′-Cy5-GCAGGTCGACTCCAAAG-3′ to 5′-TCGGTACCGGGTTAxCC TTTGGAGTCGACCTGC-3′ for G/8-oxoG reactions, where x represents either guanine or 8-oxoG). Reaction mixtures (30 μL) containing 670 nM DNA substrate were initiated by the addition of polymerase and incubated at 37°C. Concentration of polymerase in reaction mixtures varied from 1.7 to 67 nM in G/8-oxoG reactions and 2.2 to 110 nM in TT/TT dimer reactions. About 6 μL aliquots of reaction were removed at 2, 4, and 6 min, quenched by adding an equivalent volume of 95% formamide, 25 mM EDTA (formamide loading dye) and separated by electrophoresis on a denaturing 10% polyacrylamide gel. Products were imaged with a Storm™ 865 imager (GE Healthcare (Little Chalfont, United Kingdom)) and quantified using Image Quant™ TL software (GE Healthcare (Little Chalfont, United Kingdom)). Values for termination probabilities, bypass probabilities and efficiencies, and primer utilization were calculated as described elsewhere [Kokoska et al., 2003].

Reversion Mutation Assay and Analysis for Fidelity of Lesion Bypass

Analysis of lesion bypass fidelity was carried out as reported previously [McCulloch and Kunkel, 2006]. Two DNA lesions were assayed: TT dimer and 8-oxoG. Substrates used for the lesion bypass assay were created by annealing a primer strand to a template strand (5′-Cy5-AATTTCTGCAGGTCGACTCCAAAGGC-3′ to 5′-AGGAAACAGCTA TGACCATGATTACGAATTCCAGCTCGGTACCGGGTTAGCCTTTG GAGTCGACCTGCAGAAATT-3′ for TT/TT dimer reactions where the underlined TT is either a thymine pair or a TT dimer and 5′-Cy5-AATTTCTGCAGGTCGACTCCAAAG-3′ to 5′-CCAGCTCGGTACCG GGTTAxCCTTTGGAGTCGACCTGCAGAAATT-3′ for G/8-oxoG reactions, where x represents either guanine or 8-oxoG). Reaction mixtures (30 μL) containing 330 nM DNA and ~50 μCi 32P-α-dCTP were initiated with 170 nM polymerase and incubated for 30 min at 37°C. The 75-mer reaction products (TT/TT dimer) were digested with PstI and EcoRI, and the 45-mer reaction products (G/8-oxoG) were digested with PstI. An equal volume of formamide loading dye was added to prepare the samples for separation by electrophoresis on a denaturing 10% polyacrylamide gel. Newly synthesized strand was recovered and annealed to M13 gapped circular DNA. Annealed DNA was transformed into E. coli strain MC1061 cells and plated in a soft agar overlay atop a layer of CSH50 cells. The lesions are located within an amber stop codon in the lacZα gene sequence. Correct synthesis results in preservation of the amber stop codon, and thus complementation of the N-terminally truncated lacZ gene in CSH50 does not occur, which generates plaques with a light blue phenotype. Errors generated when copying the stop codon result in a functional lacZα gene and dark blue plaques are produced. Plaques were counted and assessed for color phenotype to determine mutant frequencies, and DNA from individual colonies was amplified using Illustra™ TempliPhi (GE Healthcare (Little Chalfont, United Kingdom)) and sequenced to determine the spectrum of changes. Error rates were calculated as described [Kokoska et al., 2003; McCulloch and Kunkel, 2006].

Gap-Filling Forward Mutation DNA Synthesis Reactions

The creation of the M13mp2 (WT2) gapped DNA and the gap-filling assay were carried out as detailed previously [Bebenek and Kunkel, 1995]. Reactions (20 μL) contained 3.9 nM M13mp2 (WT2) gapped DNA. Polymerase concentrations varied from 75 nM to 1.3 μM. Reactions were incubated at 37°C for 1 hr and products were separated by 0.8% agarose gel electrophoresis to verify complete filling. DNA from reactions was transformed into E. coli strain MC1061 cells and plated as described above. Errors in synthesis by pol η result in the inability of the lacZα-translated gene product to provide complementation to the LacZα-deficient cells, causing a change from dark blue to light blue or colorless plaques. Resultant plaques were counted and scored for color phenotype to determine mutant frequency. DNA from individual plaques was amplified and sequenced as described above. Error rates were calculated as described [Bebenek and Kunkel, 1995].

RESULTS

Generation of Pol η Little Finger β-Strand Mutants

Amino acids in the β-strand (β-strand 12; residues 316–324) in the little finger region of pol η were selected for mutation based on the observation that this region of the polymerase is important to correctly position the DNA template strand with the catalytic core of the enzyme [Biertümpfel et al., 2010; Ummat et al., 2012b]. This β-strand interacts extensively and assumes a nearly parallel alignment with the DNA template strand via hydrogen bonds including those that extend from amide hydrogen atoms in the protein backbone to oxygen atoms of DNA template phosphate groups [Biertümpfel et al., 2010] (Fig. 1A). To study the role of this β-strand in polymerase function, we purified a truncated fragment of human pol η (amino acids 1–511) that was overexpressed in E. coli. We generated wild-type enzyme and individual single amino acid substitutions at residues Pro 316, Thr 318, Gly 320, Ser 322, and Asn 324. At each position, alanine was substituted for the wild-type residue. We also generated a sixth variation in which Gly 320 was replaced with proline, hypothesizing that such a drastic change in the middle of the β-strand would significantly affect polymerase function. In each case, the protein purification resulted in the production of an abundantly pure protein (Fig. 1B). All seven protein preparations were assayed for both polymerase and exonuclease activity. As pol η is an exonuclease-deficient polymerase, uncontaminated purifications should not exhibit any exonuclease activity. As expected, none of the purified samples displayed any detectable mismatched (A:G) primer terminus exonuclease activity (data not shown).

Activity of Pol η Little Finger β-Strand Mutants

The overall polymerase activity of each preparation of pol η was measured using incorporation of 32P-α-dCTP during in vitro DNA synthesis on activated calf thymus DNA, followed by TCA precipitation and scintillation counting. Although most of the mutated forms of pol η retained ample activity, we observed a decrease relative to that of wild type in all cases (Table I). The activities of P316A, G320A, S322A, and N324A were 56–66% of the wild-type value. The activity of T318A was further diminished (33% activity when compared with wild type), whereas the activity of G320P was nearly abolished (7% activity when compared with wild type). Because of the exceedingly low activity of G320P, the results of further analysis of this mutant are not presented.

TABLE I.

Activity and Lesion Bypass Efficiency of β-Strand Mutants of Human Pol η

| Mutant | Relative polymerase activity (%) | Bypass efficiency (%)

|

|

|---|---|---|---|

| TTD | 8-OxoG | ||

| Wild type | 100 | 140 ± 8 | 93 ± 29 |

| P316A | 57 | 240 ± 53 (1.7×) | 150 ± 54 (1.6×) |

| T318A | 33 | 150 ± 47 (1.1×) | 75 ± 20 (0.8×) |

| G320A | 56 | 140 ± 43 (1.0×) | 80 ± 21 (0.9×) |

| G320P | 7.1 | ND | ND |

| S322A | 66 | 110 ± 16 (0.8×) | 180 ± 78 (2.0×) |

| N324A | 61 | 160 ± 16 (1.1×) | 92 ± 15 (1.0×) |

Activity values in comparison with wild type (average of two experiments). Variability in relative values between experiments was less than 15%. Incorporation of 32P-α-dCTP into activated calf thymus DNA was determined by scintillation counting of TCA precipitable material after a 30-min incubation. Wild-type polymerase activity was 7.9 nmol dCTP incorporated/fmol polymerase/min. Bypass efficiencies are the average of three time points (2, 4, and 6 min) ± standard deviation. Substrate:-polymerase ratios for TTD-containing template varied from 60:1 (T318A) to 300:1 (S322A and N324A) and 100:1 (T318A) to 400:1 (wild type) for 8-oxoG containing template. Values in parentheses are relative to wild type.

ND, not determined.

Bypass Efficiency of Pol η Little Finger β-Strand Mutants Past TTD and 8-OxoG

Next, we measured the efficiencies with which the wild type and mutated forms of pol η bypassed both TTD and 8-oxoG lesions. To do this, we used an in vitro primer extension assay (Fig. 2A) in which the substrate was in sufficient excess to ensure that when a given substrate molecule was extended by polymerase, additional extension events on the same substrate did not occur. Thus, the assay allows for analysis of a single interaction between substrate and polymerase. By performing running-start reactions with both undamaged and damaged templates, we can determine the efficiency with which pol η copies damaged DNA. Pol η exhibits very low processivity. At the 6-min time point, all forms evaluated had incorporated no more than 5–8 nucleotides when bypassing the TTD and 7–12 nucleotides when bypassing 8-oxoG (Figs. 2B and 2C). The efficiency with which wild-type pol η was able to bypass the TTD lesion was 140% (Table I). These data indicated that wild-type pol η was more likely to bypass the lesion than it was to copy equivalent undamaged DNA. This is similar to published results for full-length pol η [McCulloch et al., 2004b]. All the β-strand mutants also bypassed the TTD lesion with greater than 100% efficiency (Table I). To consider a lesion bypass efficiency value materially different from that of wild type, we require, at minimum, a twofold change. None of our mutants were significantly different from wild type by this measure. Thus, although these mutants do have reduced overall activity, their ability to bypass a TT dimer remains unaffected.

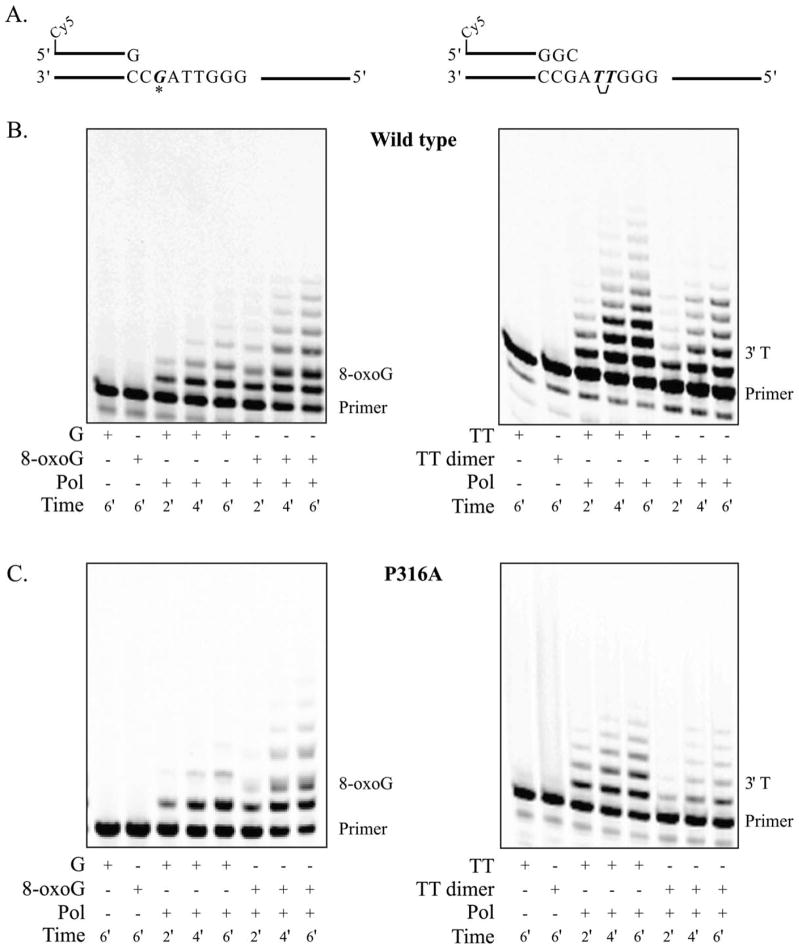

Fig. 2.

Bypass efficiency of TTD and 8-oxoG DNA lesions by human pol η. A: Schematic diagrams for G/8-oxoG (33-mer template and 17-mer primer) and TT/TT dimer (45-mer template and 26-mer primer). All substrates cause a “running start” reaction, with the 3′ end of the primer at the −2 position with respect to the damaged base (3′ crosslinked thymine for the TT dimer substrate). B: Wild-type polymerase lesion bypass efficiency reaction product separation by denaturing polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis. Analysis of band intensity (Image Quant™ TL software from GE Healthcare (Little Chalfont, United Kingdom)) verified reactions to be under single interaction conditions as judged by having constant termination probability over time in reactions that contain a large substrate excess with respect to polymerase (TT dimer: 250:1 for wild type, 150:1 for P316A; 8-oxoG: 400:1 for wild type, 200:1 for P316A) [Kokoska et al., 2003]. Lesion bypass efficiency values were calculated as previously described [Kokoska et al., 2003]. C: Representative β-strand mutant (P316A) lesion bypass efficiency reaction product separation.

The efficiency with which wild-type pol η was able to bypass an 8-oxoG lesion was 93% (Table I). This is only slightly lower than published results using full-length pol η [McCulloch et al., 2009]. The efficiencies of P316A and S322A were 150 and 180%, respectively (1.6- and 2.0-fold increases when compared with wild type), which would suggest that these forms bypass this lesion better than wild-type polymerase. N324A bypassed 8-oxoG with approximately the same efficiency as wild type (92%; no change), and T318A and G320A showed slightly decreased bypass efficiencies when compared with wild type (75 and 80%; 0.8- and 0.9-fold changes, respectively). These values indicate that bypass efficiencies of 8-oxoG by the mutated forms of pol η remain essentially equivalent to that of the wild-type polymerase. Thus, bypass remains robust despite overall reduced polymerase activity. Taken together, we find that none of the pol η mutants presented in this bypass efficiency analysis displayed any significant change in their TTD or 8-oxoG lesion bypass ability when compared with wild-type polymerase.

Fidelity of Pol η Little Finger β-Strand Mutants When Copying TTD and 8-OxoG

To determine the fidelities with which the mutated forms of pol η bypass TTD and 8-oxoG lesions, we used an in vitro reversion mutation assay. The substrate sequence matched that used in the efficiency assay and corresponded to a portion of the lacZα gene. A premature stop codon that contained the lesion under investigation was present within the sequence. Insertion of the correct nucleotide opposite the lesion preserved the stop codon, whereas an incorrect insertion at the lesion resulted in reversion to a viable lacZα sequence. After extension by the polymerase, the synthesized strand was recovered, annealed to M13mp18 gapped DNA, and transformed into E. coli. Resultant M13 phage plaques containing DNA in which replication errors were made at the stop codon were identified by their dark blue phenotype. DNA from these plaques was then amplified and sequenced to determine polymerase error rates and spectrums.

The error rates calculated for the bypass of both TTD and 8-oxoG indicate that the mutated forms of pol η can be broadly categorized into two distinct groupings (Figs. 3A–3D). The first includes mutants that showed no appreciable difference in fidelity when copying either lesion and also had error rates essentially the same as wild type when copying the corresponding undamaged DNA sequence. For this assay, we define an error rate as unchanged when the rate of the mutated polymerase exhibits a fold change of less than 2 when compared with that of wild type (i.e., 50–200% the rate of wild type). In contrast, a second group of pol η β-strand mutants had error rates unchanged from wild type when bypassing either lesion; however, their fidelities were substantially altered when copying the comparable undamaged sequence. Surprisingly, all of these mutants had better fidelities than the wild-type protein. Thus, modification of certain amino acid residues in the little finger β-strand did in fact affect the fidelity of the polymerase; however, the effect was limited to the replication of undamaged DNA and surprisingly resulted in an increase in fidelity.

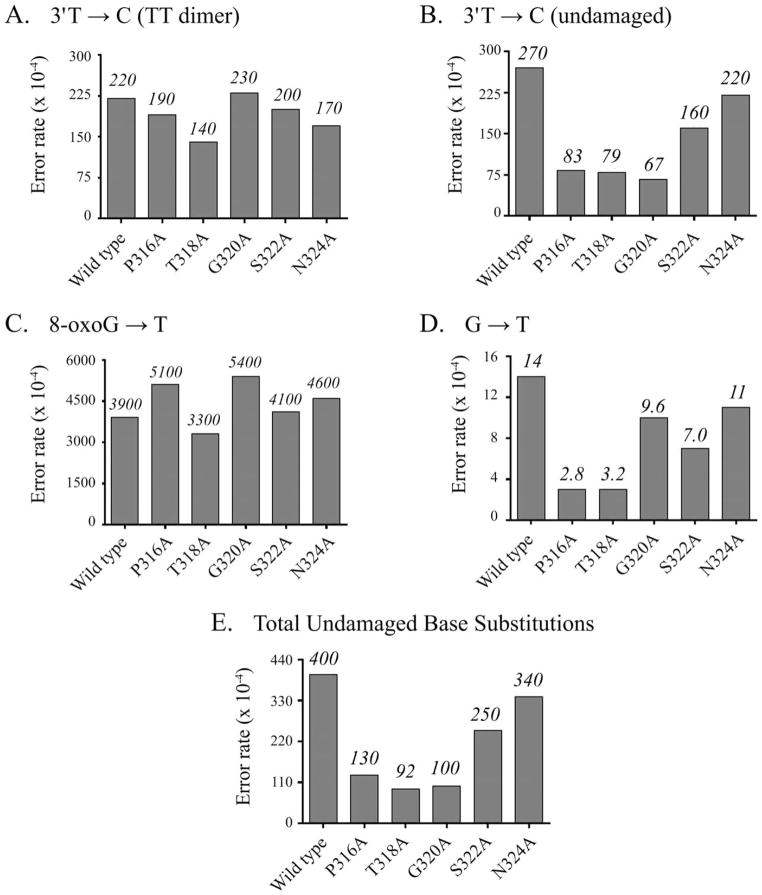

Fig. 3.

Mutating pol η differentially affects fidelity. A: TTD 3′T → C error rates for reversion mutation assay. B: T → C error rates for reversion mutation assay. C: 8-oxoG → T error rates for reversion mutation assay. D: G → T error rates for reversion mutation assay. E: Total detectable single-base substitution error rates at stop codon for reversion mutation assay. Although a significant change in fidelity was not observed for any of the mutated forms of pol η when copying either TTD or 8-oxoG lesions, the error rates opposite the corresponding undamaged bases were repeatedly observed as markedly suppressed for certain mutated forms of pol η.

T → C Transitions at the 3′T of TTD

Misincorporation of dGMP opposite thymine (either as part of a TT dimer or as undamaged DNA) causing a T → C mutation is the most frequent error made by pol η [Johnson et al., 2000; Matsuda et al., 2000, 2001; McCulloch et al., 2004b]. The error rates for T → C at the 3′T of the dimer sequence by wild-type polymerase for either TTD or corresponding undamaged templates were comparable (220 and 270 × 10−4, respectively; Figs. 3A and 3B), in agreement with the values observed using full-length pol η [McCulloch et al., 2004b]. The mutated forms of pol η with amino acid changes proximal to the active site, S322A and N324A, exhibited error rates that were not appreciably different when copying past either damaged or undamaged thymine bases (Figs. 3A and 3B). The error rates for S322A copying TTD and undamaged templates were 0.9- and 0.6-fold the rate of wild type, whereas for N324A, they were 0.8- and 0.8-fold the rate of wild type (TTD and undamaged templates, respectively).

When the amino acid changes were distal to the active site, the mutated polymerases exhibited error rates that were comparable with wild type for TTD bypass. The TTD 3′T → C error rates were essentially unchanged when compared with wild type for P316A, T318A, and G320A (0.9-, 0.7-, and 1.1-fold changes, respectively), with the greatest effect on TTD bypass fidelity for any of the mutated forms of pol η occurring when residue T318 was altered. However, unlike S322A and N324A, when copying undamaged DNA, the error rates for these mutants were decreased when compared with wild type. Thus, their fidelities were much better. The undamaged 3′T → C error rates for P316A (83 × 10−4), T318A (79 × 10−4), and G320A (67 × 10−4) were all reduced at least threefold when compared with wild type (Figs. 3A and 3B).

G → T Transversions at 8-OxoG

Although T → C changes are common with pol η, G → T (misinsertion of dAMP opposite G) changes when copying undamaged DNA are much less frequent, but increase markedly when copying 8-oxoG [Zhang et al., 2000; McCulloch et al., 2009]. The rate of dAMP misin-corporation opposite G was 14 × 10−4 for wild-type polymerase (Fig. 3D). When bypassing the corresponding oxidized base, 8-oxoG, the error rate increased to 3,900 × 10−4 (Fig. 3C). The overall trend in error rates observed for the bypass of 8-oxoG by the mutated forms of pol η was very similar to that observed for TTD bypass. Changes in amino acid residues closest to the active site did not have a significant effect on the fidelity of the polymerase when copying either the damaged or the undamaged base. In the case of 8-oxoG bypass, this included not only S322A and N324A but also G320A. When bypassing 8-oxoG, we observed only a slight increase in error rates for these forms of pol η (1.4-, 1.1-, and 1.2-fold changes for G320A, S322A, and N324A, respectively). The rates of misincorporation opposite guanine did not differ significantly from that of wild type (0.7-, 0.5-, and 0.8-fold changes for G320A, S322A, and N324A, respectively). Similar to what we observed with TTD bypass, amino acid changes distal to the active site resulted in no change in fidelity when copying 8-oxoG, but did affect synthesis of undamaged DNA. The error rate for P316A opposite 8-oxoG was slightly increased (5,100 × 10−4, 1.3-fold change when compared with wild type) and slightly decreased for T318A (3,300 × 10−4, 0.8-fold change). However, when copying G, the error rates for both forms of pol η were distinctly decreased (3.0 × 10−4, 0.2 times the the rate of wild type for both).

Single-Base Substitutions at Undamaged Stop Codon

Because of the unexpected increase in fidelity on undamaged DNA by certain pol η mutants, we also calculated error rates for total single-base substitutions at the undamaged TAG stop codon as well as all for other individual single-base substitutions detectable by this assay. The total overall base substitution error rate for wild-type pol η was 400 × 10−4 (Fig. 3E). The mutated forms of pol η exhibited a similar trend as was observed for the T → C and G → T single-base substitutions. Thus, S322A and N324A had error rates that were not significantly different from wild type (0.6- and 0.9-fold changes, respectively). However, significant changes in fidelities were observed for the forms of pol η that possessed amino acid residue changes distal to the active site. The overall error rates for P316A, T318A, and G320A were 130, 92, and 100 × 10−4 (0.3, 0.2, and 0.3 the rate of wild type, respectively). It is interesting that while changes in pol η fidelity were not observed when bypassing either lesion, we did consistently observe changes when the polymerase was acting on undamaged DNA. Furthermore, the effect was most remarkable when the changes in amino acid residues were located in the region of the DNA that stabilizes the newly synthesized duplex, rather than the region stabilizing the template near the incoming dNTP.

This trend in error rates for the mutated forms of pol η when compared with wild type was generally held for all other possible single-base substitutions. The error rates for P316A, T318A, and G320A were reduced by 50% or more when compared with wild type for all combined nucleotide mispairs at A, G, and T (G–dTMP mispairs are not detected by this assay as they result in a TAA ochre stop codon). The error rates for the remaining forms, S322A and N324A, did not deviate significantly from wild type. We did observe that the change in fidelity was most often the greatest for T318A (Table II). The T318A error rate for all combined mispairs at A was 0.2 that of the wild type rate, 0.1 for mispairs at G, and, as previously noted, 0.2 for total overall single-base substitutions. For combined mispairs at T, G320A had the greatest decrease; the error rate was 0.2 that of the rate of wild type. For the same changes, the error rate for T318A was 0.3 times the rate of wild type.

TABLE II.

Error Rates When Copying Undamaged Template by Little Finger β-Strand Mutants of Human Pol η

| Template base | Wild type | Fold change in error rate relative to wild type orientation="landscape" | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| P316A | T318A | G320A | S322A | N324A | ||

| A | 1.0 | 0.5× | 0.2× | 0.3× | 1.3× | 1.8× |

| G | 1.0 | 0.5× | 0.1× | 0.3× | 0.5× | 0.6× |

| T | 1.0 | 0.3× | 0.3× | 0.2× | 0.6× | 0.8× |

| Total | 1.0 | 0.3× | 0.2× | 0.3× | 0.6× | 0.9× |

Total base substitutions at the three template bases of the stop codon (eight of nine possible errors) are detected in this assay. G → A changes generate an ochre stop that cannot be detected by plaque phenotype). The error rates for wild type are as follows: A, 47 × 10−4; G, 51 × 10−4; T, 300 × 10−4; and Total, 400 × 10−4. Each value comes from sequence analysis of a minimum of 103 mutant plaques. Error rates were expressed as fold change when compared with wild type. Values less than one represent error rates less than wild type (i.e., higher fidelity); values greater than one represent error rates greater than wild type (i.e., lower fidelity). Values in bold indicate the β-strand mutant for which the greatest suppression in error rate was observed.

Generation of Single-Base Substitutions During Gap-Filling DNA Synthesis

To further understand how mutating residues in β-strand 12 of the little finger region of pol η affects fidelity, we used a forward mutation assay that can evaluate all possible single-base substitutions as well as insertions, deletions, and other complex errors made by the polymerase. In this assay, the polymerase replicates a 407-base gap located in the lacZα complementation sequence present in bacteriophage M13 DNA. On transformation into E. coli containing nonfunctional N-terminally deleted LacZ protein, faithful replication of the template sequence results in dark blue plaques, whereas low-fidelity replication results in a light blue or colorless phenotype. A colorless phenotype is usually the result of frameshift mutations, but can also correspond to multiple mutations made by the polymerase during synthesis of a single gapped molecule. By selecting mutant plaques for sequencing, we are able to observe the types of mutations created by the polymerase and to calculate error rates. Although the overall differences observed between the mutated forms of pol η and wild type were not as great as those from the reversion assay, the same trends appear. Thus, when changes in amino acid residues in the β-strand occur farther away from the active site, a greater decrease in error rate was generally observed. Of the five mutated forms of pol η that were able to fill the gap, P316A and T318A had the greatest decreases in overall single-base substitution error rate (0.7- and 0.6-fold changes, respectively; Fig. 4A). G320A, S322A, and N324A had fold changes of 0.8, 0.9, and 0.9, respectively. T318A exhibited the greatest decrease in error rate at each individual template base when compared with wild type in nearly all cases. The error rate at A was 0.5 times the rate of wild type, 0.8 times at G, and 0.7 times at T. For mispairs at C, P316A had the greatest decrease (0.4 times the rate of wild type).

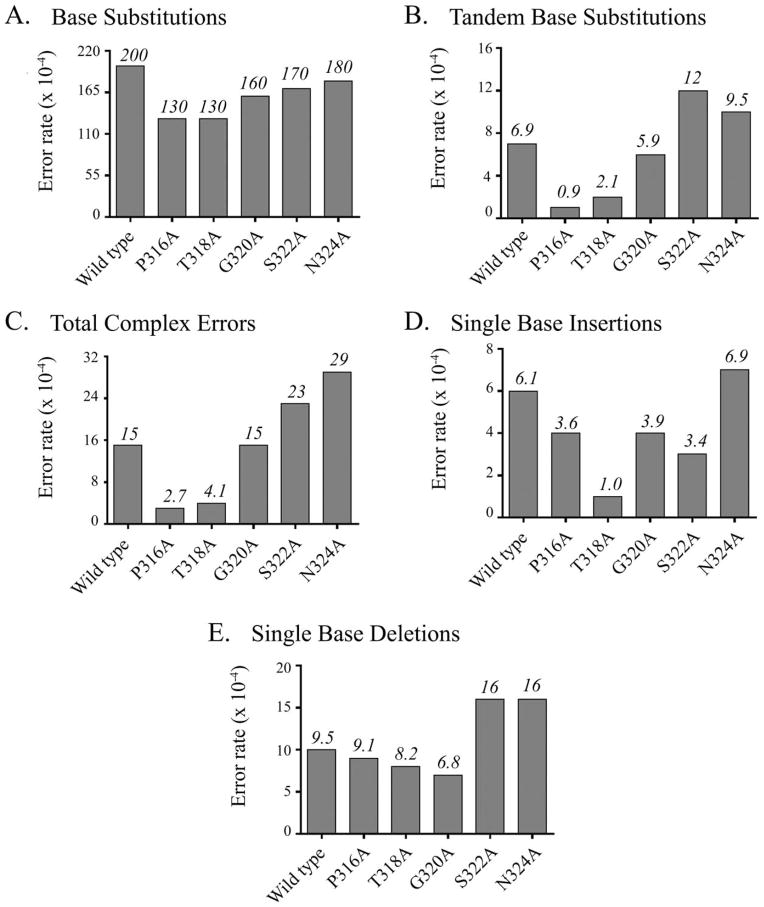

Fig. 4.

Gap-filling forward mutation results support reversion mutation assay observations. A: Total single-base substitution error rates for gap-filling forward mutation assay. B: Tandem-base substitution error rates for gap-filling forward mutation assay. C: Complex error rates for gap-filling forward mutation assay. Complex errors include insertions and deletions of two or more bases, single-base substitutions separated by one correctly copied base, two or more consecutively incorrectly copied bases, and/or any combination thereof. Amino acid substitutions in pol η little finger β-strand generally result in a suppression of erroneous base substitution when compared with wild type. When substitutions are distal to the active site, the effect is amplified. D: Insertion error rates for gap-filling forward mutation assay. E: Deletion error rates for gap-filling forward mutation assay. Significant changes for insertion and deletion fidelity were generally not observed. The only notable exception is the decrease in insertions made by T318A when compared with wild type.

Tandem-Base Substitutions, Complex Mutations, Insertions, and Deletions

The forward mutation assay also allowed us to calculate error rates for a variety of other replication errors. A common replication error made by pol η is the incorporation of two sequential mispairs resulting in a tandem-base substitution [Matsuda et al., 2000, 2001]. Like full-length pol η, we observed these types of errors in all of the mutants studied. As has already been described, we found that the greatest reductions in error rates were observed when amino acid residues distal to the active site were altered. The tandem-base error rate for the wild-type polymerase was 6.9 × 10−4 (Fig. 4B). We observed a 0.1- and 0.3-fold change in error rates for P316A and T318A, respectively, a 0.8-fold change for G320A, and a 1.7- and 1.4-fold increase for S322A and N324A, respectively, when compared with wild type. The results for other complex error rates were similar. We define complex errors to include insertions and deletions of two or more bases, single-base substitutions separated by one correctly copied base, two or more consecutively mis-paired bases, and/or any combination thereof. The complex mutation error rate for the wild-type polymerase was 15 × 10−4 (Fig. 4C). The observed error rates for P316A and T318A were significantly decreased (0.2- and 0.3-fold changes, respectively), whereas the rate for G320A was unchanged when compared with the wild-type polymerase. Surprisingly, when amino acid residues S322 and N324 were mutated, there was a nominal increase in the number of complex mutations detected. We calculated a 1.6-fold increase in the error rate for S322A and a 1.9-fold increase for N324A relative to wild-type polymerase.

In general, we did not observe any significant change in the rate of insertions or deletions made by the mutated forms of pol η when compared with wild type (Figs. 4D and 4E). The only notable observation was the insertion error rate of T318A. As noted for other types of changes made by the mutated forms of pol η, the decrease in error rate for insertions was greatest for T318A. The insertion error rate of the wild type was 6.1 × 10−4, whereas the rate of the T318A form was 1.0 × 10−4.

DISCUSSION

Mutating residues in the little finger β-strand 12 of pol η that stabilizes the DNA template strand provides clues to help understand the remarkable ability of the polymerase to bypass lesions. Specifically, our results show that the polymerase is able to tolerate minor alterations in its structure and still perform lesion bypass robustly. The observation that the fidelity of bypass is still relatively low (error frequencies of 3–5% for TT dimer; 50% for 8-oxoG) suggests that although the polymerase is ideally suited for performing bypass of these lesions because it is not rigidly constrained to a single conformation, it also possesses a propensity to introduce errors for the same reason.

Of the residues tested, Thr 318 appears to be distinct and especially important to the fidelity of pol η. It was somewhat surprising that mutating T318 and adjacent residues affected fidelity as they did, given their distant location from the polymerase active site. Considering the importance of pol η in lesion bypass, it was also unexpected to observe that mutating residues in this region had a much greater effect on polymerase fidelity when copying undamaged DNA than was observed when the polymerase bypassed either TT dimer or 8-oxoG lesions. The results may provide additional insight regarding both the behavior of pol η as well as the remarkable aptitude of pol η for DNA lesion bypass.

Thr 318 and Pol η Fidelity

Using two distinct assays for fidelity, we find that the T318A mutant consistently makes a variety of errors with less frequency than the wild-type polymerase. Thus, the fidelity is better than wild type when copying undamaged DNA, although we did see a modest increase in the bypass fidelity for both TT dimer and 8-oxoG as well. When copying A, G, or T bases, 8-oxoG, and the 3′T of TTD, T318A had the lowest error rates. Thr 318 provides a hydrogen bond from its side-chain hydroxyl group to a template phosphate oxygen imparting stability to the newly formed DNA duplex (Fig. 5A). Noting that mutations occur when a mispaired nucleotide is stable enough to be both incorporated and extended by the polymerase, it is possible that the replacement of threonine with alanine disrupts the hydrogen bonding and engenders a slight shift in the template strand position. The conformational adjustments rendered by pol η presumably destabilize the incorrect base pairing. Given that a residue residing at least three bases downstream of the active site (Fig. 1A) can so drastically alter fidelity is surprising.

Fig. 5.

A: Magnified view of pol η little finger β-strand that stabilizes the DNA template strand. Hydrogen bonds (violet dashed lines) between amino acid residues K317 and T318 are shown interacting with the template strand of recently copied DNA (the fourth and the fifth bases away from the templating base:incoming dNTP pair; light pink, carbon; dark pink, phosphorus; yellow, nitrogen; cyan, oxygen. Only hydrogen bonds from K317 and T318 are shown, with the remaining protein and DNA atoms represented in gray. The image was prepared from PDB entry 3MR2 [Biertümpfel et al., 2010] using the PyMOL Molecular Graphics System, Version 1.3 Schrödinger, LLC. B: Amino acid sequence alignment of pol η from multiple species and the other human Y-family polymerases. Hs, Homo sapiens; Mm, Mus musculus; Xl, Xenopus laevis; At, Arabidopsis thaliana; Ce, Caenorhabditis elegans; Sc, Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Letters in bold indicate β-strand 12 residues. Alignment was created using Clustal Omega [Sievers et al., 2011].

Little finger β-Strand in Other Y-Family Polymerases

Crystal structures of not only human pol η but also of S. cerevisiae pol η and the other human Y-family members ι, κ, and Rev1 have provided a wealth of information that has helped to elucidate the functional domains of these enzymes [Nair et al., 2004, 2005; Lone et al., 2007; Biertümpfel et al., 2010; Silverstein et al., 2010]. The β-strand and the way in which it interacts with the template DNA is conserved across nearly all of the Y-family polymerase structures. This suggests that β-strand 12 is essential to polymerase function. Our result that distal amino acid residue T318 appears to be particularly important to fidelity is compelling considering that T318 is not a conserved residue (Fig. 5B) [Boudsocq et al., 2002; Biertümpfel et al., 2010]. In many other Y-family polymerases, serine occupies this position, and we wonder if its modification would affect fidelity and function in a similar manner. In addition, it will be interesting to test a pol η T318S mutant using the assays described here.

β-Strand Significance to Polymerase Fidelity

In addition to the effect observed when mutating Thr 318, the error rate was also suppressed when Pro 316 was mutated and, to a lesser extent, when Gly 320 was mutated. These findings support the hypothesis that interactions between the region of the β-strand distal to the active site and the newly synthesized duplex DNA are influential to pol η fidelity. This is consistent with previous observations regarding these amino acids [Biertumpfel et al., 2010; Ummat et al., 2012a; Zhao et al., 2012], and this work extends those observations to a large number of types of errors. Crystal structures of human pol η reveal four hydrogen bonds that extend from the side chain of Arg 361. Two reach to the main chain oxygen of Pro 316 and two to the side chain of Asp 355. These construct a web of hydrogen bonds that provide additional stability to the β-strand [Biertümpfel et al., 2010]. G1083T has been established as a missense mutation in an XPV patient [Broughton et al., 2002], leading to the amino acid change R361S. The patient in whom the homozygous G1083T change was identified presented with a fairly mild XPV phenotype (at 57 years with less than 10 tumors) [Broughton et al., 2002]. It has been proposed that the disruption of the hydrogen bond between Arg 361 and Pro 316 leads to the XPV phenotype due to subsequent interruption of the polymerase–DNA interaction [Biertümpfel et al., 2010]. Because the results of our current study support the hypothesis that modification to amino acid residues contributing to the positional integrity of the little finger β-strand affect pol η function, an in vitro characterization of the R361S form of the polymerase would be insightful, as would be an investigation of the in vivo phenotype of P316A.

Lesion Bypass and Mutation Suppression

We have recently reported on other pol η mutants that affected undamaged and damaged DNA replication fidelity differentially, and we believe that these reports are the first to describe this phenomenon [Suarez et al., 2013]. In that report, two different active site residues, R61 (interacts with the incoming dNTP) and S62 (contacts the DNA one base upstream of the template base), were changed to alanine (R61 and S62) or glycine (S62). These forms displayed increased fidelity when copying undamaged G but not when copying 8-oxoG. Additionally, mutation of Q38 (interacts with the template base) to alanine resulted in an increase in fidelity when copying both G and 8-oxoG, but a decrease in fidelity when copying a TT dimer.

In this new work, the finding that the identity of amino acid residues providing hydrogen bonds from the backbone of β-strand 12 is sometimes inconsequential to pol η bypass efficiency and fidelity was not altogether unexpected as the interactions likely remain in place in the mutated forms of the polymerase. This emphasizes the importance of the β-strand main chain–DNA interactions. Nonetheless, it was somewhat unexpected that when certain residues were mutated, fidelity was affected when copying undamaged DNA but not when bypassing DNA lesions. As pol η is likely evolutionarily optimized for TLS, it is reasonable to find that fidelity of lesion bypass appears to function at a given fidelity and efficiency. However, the extent to which these properties are unyielding in addition to the fact that some mutated forms of the polymerase seem unable to accommodate undamaged DNA in the same way as damaged DNA was unanticipated. It could be suggested that under initial consideration, these results are not relevant to pol η function in vivo. Indeed, the most widely accepted role of pol η is the bypass of CPDs and other lesions [Prakash et al., 2005]. However, the exact molecular mechanism of TLS by pol η is not clear, and evidence suggests that short stretches of undamaged DNA both upstream and downstream of the lesion are also copied by the polymerase [McCulloch et al., 2004a]. It is interesting that each mutant tested displayed overall activity that was lower than that of the wild-type enzyme (Table I). This fits our hypothesis that, in vivo, it is the entire TLS process that is relevant to mutation suppression. This would include at minimum: bypass efficiency and fidelity by the polymerase, overall ability to synthesize DNA, proofreading in trans of errors, and the effects of accessory proteins. In addition, pol η has been shown to participate in multiple DNA metabolism pathways, not all of which involve damaged DNA [Rogozin et al., 2001; Zeng et al., 2001; Kawamoto et al., 2005; Kamath-Loeb et al., 2007; Bétous et al., 2009; Rey et al., 2009], making study of its properties when copying undamaged DNA relevant.

Given that modifying residues important to stabilize and align the DNA for correct nucleotide incorporation did not appreciably alter the fidelity of the polymerase opposite DNA lesions demonstrates just how exceptional pol η is as a lesion bypass polymerase. It is clearly able to accommodate slight alterations to protein–DNA alignment without affecting its TLS function. Furthermore, the fact that this was the case not only for the bypass of TT dimer but also for 8-oxoG might imply that pol η is equally suited to bypass the 8-oxoG lesion as well. Whether the same holds true for lesions not bypassed as readily (i.e., AP site and 2-hydroxyadenine) [Kokoska et al., 2003; Barone et al., 2007] will be interesting to investigate, as will the properties of lesions with crystal structure information (i.e., cisplatin adducts) [Ummat et al., 2012a; Zhao et al., 2012].

We acknowledge that the in vitro properties of the various mutated forms of pol η described here may not translate to phenotypic changes in vivo and that post-translational modifications to the polymerase and other protein–protein interactions that may affect the TLS process are not considered in this biochemical analysis. To address this, we propose to investigate whether or not these forms of pol η are able to provide complementation to XPV cells and to determine if these mutants behave similarly in vivo. We do assert, however, that even in the absence of in vivo analysis, the type of biochemical data that we have presented here provides indispensable information regarding the relationship between polymerase structure and function and molecular mechanism. Accordingly, we believe it will be valuable to characterize the forms of full-length pol η predicted to possess amino acid substitutions from the various identified XPV mutations [Broughton et al., 2002] for their properties in vitro. Compilation of such results with existing biochemical data will provide important insight to help further understand the unique aptitude of pol η for lesion bypass and its other possible functions within the cell.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Drs. Robert Smart (North Carolina State University), James Bonner (North Carolina State University), and Thomas Kunkel (National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences) for critical reading of the manuscript, helpful conversations, and materials.

Grant sponsor: National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences, National Institutes of Health; Grant numbers: R01 ES016942 and T32 ES007046; Grant sponsor: College of Agriculture and Life Sciences, North Carolina State University.

Abbreviations

- CPD

cyclobutane pyrimidine dimer

- NaPPi

sodium pyrophosphate, 8-oxoG, 7,8-dihydro-8-oxoguanine

- Pol η

DNA polymerase η

- TCA

trichloroacetic acid

- TLS

translesion synthesis

- TTD/TT dimer

cis-syn cyclobutane thymine–thymine dimer

- XPV

xeroderma pigmentosum variant

Footnotes

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

R.A. Beardslee designed and conducted experiments, analyzed data, and prepared the manuscript. S.C. Suarez helped design experiments and provided technical assistance and input. S.M. Toffton provided technical assistance with experiments. S.D. McCulloch designed experiments, provided intellectual input, and made edits to the manuscript. All authors approved the final manuscript. R.A. Beardslee and S.D. McCulloch had complete access to the study data. All authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Barone F, McCulloch SD, Macpherson P, Maga G, Yamada M, Nohmi T, Minoprio A, Mazzei F, Kunkel TA, Karran P, Bignami M. Replication of 2-hydroxyadenine-containing DNA and recognition by human MutSα. DNA Repair (Amst) 2007;6:355–366. doi: 10.1016/j.dnarep.2006.11.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bebenek K, Kunkel TA. Analyzing fidelity of DNA polymerases. Methods Enzymol. 1995;262:217–232. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(95)62020-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beese L, Derbyshire V, Steitz T. Structure of DNA polymerase I Klenow fragment bound to duplex DNA. Science. 1993;260:352–355. doi: 10.1126/science.8469987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bétous R, Rey L, Wang G, Pillaire M-J, Puget N, Selves J, Biard DSF, Shin-Ya K, Vasquez KM, Cazaux C, Hoffmann J-S. Role of TLS DNA polymerases η and κ in processing naturally occurring structured DNA in human cells. Mol Carcinog. 2009;48:369–378. doi: 10.1002/mc.20509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biertümpfel C, Zhao Y, Kondo Y, Ramón-Maiques S, Gregory M, Lee JY, Masutani C, Lehmann AR, Hanaoka F, Yang W. Structure and mechanism of human DNA polymerase η. Nature. 2010;465:1044–1048. doi: 10.1038/nature09196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boudsocq F, Ling H, Yang W, Woodgate R. Structure-based interpretation of missense mutations in Y-family DNA polymerases and their implications for polymerase function and lesion bypass. DNA Repair (Amst) 2002;1:343–358. doi: 10.1016/s1568-7864(02)00019-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Broughton BC, Cordonnier A, Kleijer WJ, Jaspers NG, Fawcett H, Raams A, Garritsen VH, Stary A, Avril MF, Boudsocq F, Masutani C, Hanaoka F, Fuchs RP, Sarasin A, Lehmann AR. Molecular analysis of mutations in DNA polymerase η in xeroderma pigmentosum-variant patients. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2002;99:815–820. doi: 10.1073/pnas.022473899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doublie S, Tabor S, Long AM, Richardson CC, Ellenberger T. Crystal structure of a bacteriophage T7 DNA replication complex at 2.2 A ° resolution. Nature. 1998;391:251–258. doi: 10.1038/34593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson RE, Washington MT, Prakash S, Prakash L. Fidelity of human DNA polymerase η. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:7447–7450. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.11.7447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamath-Loeb AS, Lan L, Nakajima S, Yasui A, Loeb LA. Werner syndrome protein interacts functionally with translesion DNA polymerases. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104:10394–10399. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0702513104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawamoto T, Araki K, Sonoda E, Yamashita YM, Harada K, Kikuchi K, Masutani C, Hanaoka F, Nozaki K, Hashimoto N, Takeda S. Dual roles for DNA polymerase η in homologous DNA recombination and translesion DNA synthesis. Mol Cell. 2005;20:793–799. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2005.10.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kokoska RJ, McCulloch SD, Kunkel TA. The efficiency and specificity of apurinic/apyrimidinic site bypass by human DNA polymerase η and Sulfolobus solfataricus Dpo4. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:50537–50545. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M308515200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kusumoto R, Masutani C, Iwai S, Hanaoka F. Translesion synthesis by human DNA polymerase η across thymine glycol lesions. Biochemistry. 2002;41:6090–6099. doi: 10.1021/bi025549k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee DH, Pfeifer GP. Translesion synthesis of 7,8-dihydro-8-oxo-2′-deoxyguanosine by DNA polymerase η in vivo. Mutat Res. 2008;641:19–26. doi: 10.1016/j.mrfmmm.2008.02.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lone S, Townson SA, Uljon SN, Johnson RE, Brahma A, Nair DT, Prakash S, Prakash L, Aggarwal AK. Human DNA polymerase κ encircles DNA: Implications for mismatch extension and lesion bypass. Mol Cell. 2007;25:601–614. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2007.01.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maga G, Villani G, Crespan E, Wimmer U, Ferrari E, Bertocci B, Hubscher U. 8-Oxo-guanine bypass by human DNA polymerases in the presence of auxiliary proteins. Nature. 2007;447:606–608. doi: 10.1038/nature05843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masutani C, Araki M, Yamada A, Kusumoto R, Nogimori T, Maekawa T, Iwai S, Hanaoka F. Xeroderma pigmentosum variant (XP-V) correcting protein from HeLa cells has a thymine dimer bypass DNA polymerase activity. EMBO J. 1999a;18:3491–3501. doi: 10.1093/emboj/18.12.3491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masutani C, Kusumoto R, Yamada A, Dohmae N, Yokoi M, Yuasa M, Araki M, Iwai S, Takio K, Hanaoka F. The XPV (xeroderma pigmentosum variant) gene encodes human DNA polymerase η. Nature. 1999b;399:700–704. doi: 10.1038/21447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masutani C, Kusumoto R, Iwai S, Hanaoka F. Mechanisms of accurate translesion synthesis by human DNA polymerase η. EMBO J. 2000;19:3100–3109. doi: 10.1093/emboj/19.12.3100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsuda T, Bebenek K, Masutani C, Hanaoka F, Kunkel TA. Low fidelity DNA synthesis by human DNA polymerase-η. Nature. 2000;404:1011–1013. doi: 10.1038/35010014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsuda T, Bebenek K, Masutani C, Rogozin IB, Hanaoka F, Kunkel TA. Error rate and specificity of human and murine DNA polymerase η. J Mol Biol. 2001;312:335–346. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2001.4937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCulloch SD, Kunkel TA. Measuring the fidelity of translesion DNA synthesis. Methods Enzymol. 2006;408:341–355. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(06)08021-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCulloch SD, Kokoska RJ, Chilkova O, Welch CM, Johansson E, Burgers PM, Kunkel TA. Enzymatic switching for efficient and accurate translesion DNA replication. Nucleic Acids Res. 2004a;32:4665–4675. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkh777. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCulloch SD, Kokoska RJ, Masutani C, Iwai S, Hanaoka F, Kunkel TA. Preferential cis-syn thymine dimer bypass by DNA polymerase η occurs with biased fidelity. Nature. 2004b;428:97–100. doi: 10.1038/nature02352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCulloch SD, Kokoska RJ, Garg P, Burgers PM, Kunkel TA. The efficiency and fidelity of 8-oxo-guanine bypass by DNA polymerases δ and η. Nucleic Acids Res. 2009;37:2830–2840. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkp103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McElhinny SAN, Stith CM, Burgers PMJ, Kunkel TA. Inefficient proofreading and biased error rates during inaccurate DNA synthesis by a mutant derivative of Saccharomyces cerevisiae DNA polymerase δ. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:2324–2332. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M609591200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nair DT, Johnson RE, Prakash S, Prakash L, Aggarwal AK. Replication by human DNA polymerase-ι occurs by Hoogsteen base-pairing. Nature. 2004;430:377–380. doi: 10.1038/nature02692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nair DT, Johnson RE, Prakash L, Prakash S, Aggarwal AK. Rev1 employs a novel mechanism of DNA synthesis using a protein template. Science. 2005;309:2219–2222. doi: 10.1126/science.1116336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prakash S, Johnson RE, Prakash L. Eukaryotic translesion synthesis DNA polymerases: Specificity of structure and function. Annu Rev Biochem. 2005;74:317–353. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.74.082803.133250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rey L, Sidorova JM, Puget N, Boudsocq F, Biard DS, Monnat RJ, Jr, Cazaux C, Hoffmann JS. Human DNA polymerase η is required for common fragile site stability during unperturbed DNA replication. Mol Cell Biol. 2009;29:3344–3354. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00115-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rogozin IB, Pavlov YI, Bebenek K, Matsuda T, Kunkel TA. Somatic mutation hotspots correlate with DNA polymerase η error spectrum. Nat Immunol. 2001;2:530–536. doi: 10.1038/88732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sawaya MR, Prasad R, Wilson SH, Kraut J, Pelletier H. Crystal structures of human DNA polymerase β complexed with gapped and nicked DNA: Evidence for an induced fit mechanism. Biochemistry. 1997;36:11205–11215. doi: 10.1021/bi9703812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sievers F, Wilm A, Dineen D, Gibson TJ, Karplus K, Li W, Lopez R, McWilliam H, Remmert M, Soding J, Thompson JD, Higgins DG. Fast, scalable generation of high-quality protein multiple sequence alignments using Clustal Omega. Mol Syst Biol. 2011;7:539. doi: 10.1038/msb.2011.75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silverstein TD, Johnson RE, Jain R, Prakash L, Prakash S, Aggarwal AK. Structural basis for the suppression of skin cancers by DNA polymerase η. Nature. 2010;465:1039–1043. doi: 10.1038/nature09104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suarez SC, Beardslee RA, Toffton SM, McCulloch SD. Biochemical analysis of active site mutations of human polymerase η. Mutat Res. 2013;745–746:46–54. doi: 10.1016/j.mrfmmm.2013.03.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trincao J, Johnson RE, Escalante CR, Prakash S, Prakash L, Aggarwal AK. Structure of the catalytic core of S. cerevisiae DNA polymerase η: Implications for translesion DNA synthesis. Mol Cell. 2001;8:417–426. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(01)00306-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ummat A, Rechkoblit O, Jain R, Roy Choudhury J, Johnson RE, Silverstein TD, Buku A, Lone S, Prakash L, Prakash S, Aggarwal AK. Structural basis for cisplatin DNA damage tolerance by human polymerase η during cancer chemotherapy. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2012a;19:628–632. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.2295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ummat A, Silverstein TD, Jain R, Buku A, Johnson RE, Prakash L, Prakash S, Aggarwal AK. Human DNA polymerase η is pre-aligned for dNTP binding and catalysis. J Mol Biol. 2012b;415:627–634. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2011.11.038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vaisman A, Masutani C, Hanaoka F, Chaney SG. Efficient translesion replication past oxaliplatin and cisplatin GpG adducts by human DNA polymerase η. Biochemistry. 2000;39:4575–4580. doi: 10.1021/bi000130k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Washington MT, Johnson RE, Prakash L, Prakash S. Accuracy of lesion bypass by yeast and human DNA polymerase η. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2001;98:8355–8360. doi: 10.1073/pnas.121007298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeng X, Winter DB, Kasmer C, Kraemer KH, Lehmann AR, Gearhart PJ. DNA polymerase η is an A-T mutator in somatic hypermutation of immunoglobulin variable genes. Nat Immunol. 2001;2:537–541. doi: 10.1038/88740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y, Yuan F, Wu X, Rechkoblit O, Taylor JS, Geacintov NE, Wang Z. Error-prone lesion bypass by human DNA polymerase η. Nucleic Acids Res. 2000;28:4717–4724. doi: 10.1093/nar/28.23.4717. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao Y, Biertümpfel C, Gregory MT, Hua Y-J, Hanaoka F, Yang W. Structural basis of human DNA polymerase η-mediated chemoresistance to cisplatin. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2012;109:7269–7274. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1202681109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]