Abstract

Background: The search to identify genes for the susceptibility to alcohol dependence (AD) is generating interest for genetic risk assessment. The purpose of this study is to examine the level of interest and concerns for genetic testing for susceptibility to AD. Methods: Three hundred four African American adults were recruited through public advertisement. All participants were administered the Genetic Psycho-Social Implication (GPSI) questionnaire, which surveyed their interests in hypothetical genetic testing for AD, as well as their perception of ethical and legal concerns. Results: Over 85% of participants were interested in susceptibility genetic testing; however, persons with higher education (p=0.002) and income (p=0.008) were less willing to receive testing. Perception of AD as a deadly disease (48.60%) and wanting to know for their children (47.90%) were the strongest reasons for interest in testing. Among those not interested in testing, the belief that they were currently acting to lower their risk was the most prevalent. The most widely expressed concern in the entire sample was the accuracy of testing (35.50%). Other notable concerns, such as issues with the method of testing, side effects of venipuncture, falsely reassuring results, and lack of guidelines on “what to do next” following test results, were significantly associated with willingness to receive testing. Conclusion: Although an overwhelming majority of participants expressed an interest in genetic testing for AD, there is an understandable high level of methodological and ethical concerns. Such information should form the basis of policies to guide future genetic testing of AD.

Introduction

Advances in the search for susceptibility genes of alcohol dependence (AD) are generating interest for possible genetic risk assessment. A consideration before developing genetic testing is determination of the level of interest for the test and the concerns about the ethical, legal, and social implications of such tests to the potential users or consumers. It is this information that may provide the basis for policies and education to guide future genetic testing of AD and other similar multifactorial diseases.

AD is a common multifactorial disease (Cloninger et al., 1981). The Diagnostic Statistical Manual IV (DSM-IV) criteria for AD specifies three or more of the following symptoms over a 1-year period: tolerance, symptoms of alcohol withdrawal, drinking more than intended, unsuccessful attempts to cut down on use, excessive time related to activities necessary to obtain alcohol, use alcohol or recover from its effects, impaired social or work activities, and continued to use alcohol despite physical or psychological consequences (American Psychiatric Association, 2000). The newly published DSM-V criterion for alcohol use disorder encompasses alcohol abuse and AD in a continuum of severity (American Psychiatric Association, 2013).

Family studies have documented a three- to fivefold increased risk of AD among first-degree relatives (Schuckit, 2000) of AD probands. Based on estimates from twin studies, genetic factors could explain 40–60% of the variance in the risk for alcoholism (Heath et al., 1997). Approximately 40% of the general population has a family history of AD (Grant, 2000).

Molecular genetic studies have identified some genes with known biological plausibility to mechanisms of alcohol metabolism or central nervous system effects. Notable among these are alcohol dehydrogenase (Murayama et al., 1998), aldehyde dehydrogenase (Wall and Ehlers, 1995), serotonin transporter gene (Sander et al., 1997), γ-aminobutyric acid (Dick et al., 2004), and bitter taste receptor (Hinrich et al., 2006).

There are a number of studies that investigate the public interest and concerns in genetic testing for multifactorial disorders. However, the majority of the studies examine susceptibility genetic testing for cancer, either specified cancer, such as breast, colon, or prostate cancer, or for cancer risk in general (Smith and Croyle, 1995; Andrykowski et al., 1996; Bottorff et al., 2002; Bunn et al., 2002). Interest in genetic testing was reported to be high between both the clinical and general population cohorts (Kinney et al., 2000; Kash and Dabney, 2001).

Laegsgaard et al. (2009) examined public attitude toward and interest for predictive genetics of psychiatric conditions—anxiety, bipolar disease, schizophrenia, and depression—and observed substantial interests in testing among participants. Findings from this study revealed that interest was positively associated with having children, trusting the investigators, and perceived optimism that awareness of their genetic status will better prepare them to fight the disorder.

While stigma associated with major psychiatric conditions influences interests for genetic testing (Smith et al., 2009), similar relationship with respect to AD is not clear.

Gamm et al. (2004b) investigated interest and concerns about hypothetical testing for AD in an at-risk population based on family history. Findings from this study suggest that participants' interest was moderate (63%). Of the participants who indicated that they would be interested in testing, there were a wide range of reasons from curiosity to perceived benefit. Of the participants who indicated that they would not be interested in testing, the main reason for their decision was that the results would not be useful. Many thought they were already doing everything to reduce their risk and the results of the test would not change their drinking behavior. Some of the common concerns regarding testing were privacy fears, genetic determinism, what the next steps would be, and sensitivity of testing. The most anticipated benefit of testing was an increase in monitoring one's own alcohol consumption as well as an increase in public education about alcohol use disorders (Gamm et al., 2004b). However, this study was conducted in a small (n=27) at-risk population of European descent. Limited studies have investigated the perceptions of hypothetical genetic testing for the susceptibility to AD among African Americans (Marshall et al., 2012). Marshall et al. (2012) evaluated the perceived importance of genetic testing for AD compared with other multifactorial diseases among African Americans. This study divided respondents into two groups, including those who perceived testing for AD to be equally important as testing for cancer and those who did not. Results showed that nearly 86% of respondents believed that genetic testing for alcoholism was equally important as testing for cancer. Moreover, it noted there is limited research that specifically investigates the level of interest and concerns for genetic testing susceptibility to AD and the methodological characteristics associated with the willingness to undergo genetic testing among African American populations.

Important predictors, such as beliefs, perceptions, interest and concerns, play a major role of whether persons will actively pursue any genetic risk services. There remains underutilization of genetic risk services among ethnic minority populations. Moreover, there is limited literature that has assessed ethical concerns about genetic testing with the cultural, social, and environmental context for alcohol use problems. Unfortunately, much of what is known about barriers and perceptions of genetic testing is based upon persons of European descent for other heredity disorders. There is a dearth of literature examining genetic testing for the susceptibility to alcohol use disorders in diverse populations. The purpose of this study was to examine the interest and concerns of hypothetical genetic testing for the susceptibility to AD in a community sample of African Americans. This study is novel because it aims to address various factors, specifically, the normative underpinnings of beliefs, interest and concerns regarding hypothetical genetic testing for AD, as well as the implications of genomics for how ethnic minorities conceptualize and understand its impact with health and testing decisions. Understanding of the factors associated with both interest and concerns for predictive genetic testing will provide an important foundation for developing education, counseling, genetic services, and policies.

Materials and Methods

Recruitment of participants

Participants were recruited from local hospitals, health fairs, colleges, and community settings such as hairdressers, barbershops, and restaurants in the Washington, DC area. The study was approved by the Howard University Institutional Review Board. African American adults without a previous history of AD were eligible.

Participant interview and instruments

The Genetic Psycho-Social Implication (GPSI) questionnaire was developed specifically for this study based on the results from Gamm et al. (2004a,b) and Kessler et al. (2005). The sections used for this article reviewed interest in genetic testing for the susceptibility to AD, belief about the impact of this type of testing, and concerns about genetic susceptibility testing for AD. A pilot test of the questionnaire was conducted using a convenient sample that was representative of the study population. The questionnaire was readministered to the same group of 10 individuals within 7 days, later as a test–retest measure of the internal consistency of individuals' responses. The overall reliability coefficient for the questionnaire was 0.76.

Heavy drinking and AD were assessed using a brief telephone general screener and the Alcohol Use Disorder Identification Test (AUDIT). Heavy drinking was defined as consuming 7 or more drinks a week (if female), or 14 or more drinks a week (if male). Participants who drank at these levels weekly were also screened to rule out AD using the AUDIT. Participants who were not alcohol dependent based on the AUDIT were invited to participate in the study. Finally, demographic data were collected along with a detailed family history of AD.

Statistical analysis

All data were analyzed using SPSS 16.0 software (2007; SPSS, Inc., Chicago, IL). Cross-sectional analysis explored the relationship between characteristics of study participants and willingness to test (primary outcome) and concerns about testing (secondary outcome). The independent samples t-test and Pearson's chi-square were used to compare demographic variables across the primary outcome variables. Binary logistic regression models were used to examine the relationships between willingness to test and various concerns for testing, privacy or confidentiality, effect of testing on insurance, method of testing, side effect of obtaining blood, accuracy of test, false reassurance by a low risk, what to do next, and labeling from family, friends, or doctors. Significance was established at p<0.05.

Results

Interest in genetic testing

A total of 304 African American participants (113 men and 191 women) with an age range of 18–83 years completed this study. Table 1 represents the demographics of the sample categorized by willingness to take a genetic test for the susceptibility to AD. More than 85% (n=259) of the participants expressed willingness to test. Differences existed across willingness to test and the level of education, personal income, and heavy drinking. Interestingly, participants with more education (p=0.002) and higher income (p=0.008) were less willing to be tested. Finally, a history of heavy drinking was positively associated with interest (p=0.038).

Table 1.

Demographic Characteristics of a Community Sample of African Americans Based on Whether or Not They Were Willing to Take a Test for Genetic Susceptibility to Alcohol Dependence (n=304)

| Characteristics | Willing to be tested n=259 | Not willing to be tested n=45 | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (mean±SD) | 39.34±14.61 | 39.64±15.91 | 0.900 |

| Female (%) | 61.78 | 68.89 | 0.362 |

| Education (%) | 0.002b | ||

| <High school | 11.20 | 6.67 | |

| High school/GED | 18.53 | 8.89 | |

| Some college/Tech | 45.95 | 31.11 | |

| 4-year college degree | 13.13 | 24.44 | |

| Some graduate school | 4.63 | 17.78 | |

| Graduate/advanced degree | 6.56 | 11.11 | |

| Income (%)a | 0.008b | ||

| <$10,000/year | 43.58 | 37.78 | |

| $10,000–19,999/year | 10.89 | 11.11 | |

| $20,000–29,999/year | 15.18 | 8.89 | |

| $30,000–39,999/year | 11.67 | 6.67 | |

| $40,000–49,999/year | 7.00 | 8.89 | |

| $50,000–74,999/year | 7.78 | 8.89 | |

| $75,000–99,999/year | 1.95 | 15.56 | |

| >$99,999/year | 1.95 | 2.22 | |

| Marital status (%) | 0.397 | ||

| Married | 13.51 | 17.78 | |

| Single never married | 54.83 | 55.56 | |

| Single cohabiting | 7.34 | 4.44 | |

| Separated/divorced | 20.46 | 13.33 | |

| Widow/widower | 3.86 | 8.89 | |

| Positive family history of AD (%) | 50.97 | 44.44 | 0.677 |

| Heavy drinkers (%) | 16.22 | 4.44 | 0.038b |

| Employment (%) | 0.565 | ||

| Full time | 35.14 | 40.00 | |

| Part time | 13.13 | 4.44 | |

| Not employed | 17.37 | 13.33 | |

| Student | 22.78 | 28.89 | |

| Retired | 3.09 | 4.44 | |

| Others (not previously specified) | 8.49 | 8.89 | |

| Have children | 51.94 | 55.56 | 0.654 |

Excludes two participants who were willing to be tested, but declined to provide income data.

p<0.05.

AD, alcohol dependence; GED, general education development; Tech, Technical School; SD, standard deviation.

Evaluation of reasons for willingness/nonwillingness to receive genetic test

Participants were asked to rate their level of agreement to each of the eight hypothetical reasons for interest in genetic testing. Participants who responded that they would be interested in testing were presented with a set of statements as to their motivations for testing. Figure 1 shows participants who were willing to test. With the exception of the reason to “change drinking if the results of the predictive test show a decreased risk for alcohol dependence” more than half of the participants either agreed or strongly agreed with these hypothetical reasons. Combining agree and strongly agree response categories, curiosity was the most prevalent reason for testing, followed by interest in testing because “alcoholism is a deadly disease” and “wanting to know for their children.”

FIG. 1.

Participant responses to proposed reasons for interest in testing. Listed above each segment is the percentage (%) of participants who agree strongly, agree, are uncertain, disagree, or strongly disagree with proposed reasons for willingness to take a test for genetic susceptibility to alcohol dependence (AD). Less than 2% strongly disagreed that reasons for testing included curious, improve healthcare quality, alcoholism is a deadly disease, equally important to screen for alcoholism.

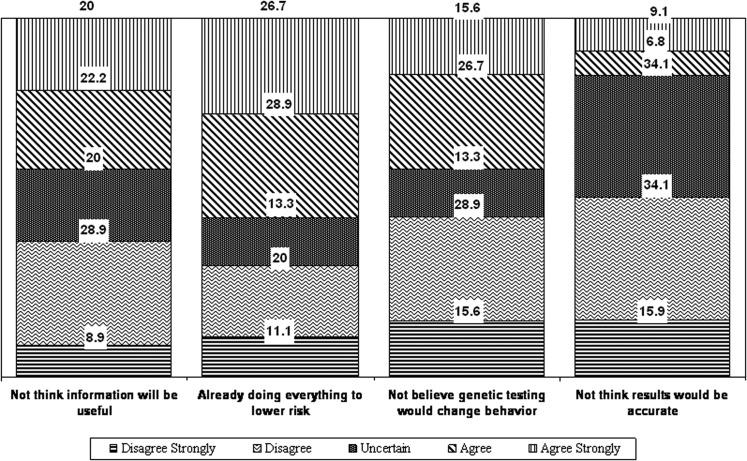

On the other hand, participants who responded that they would not be willing to test were presented with a different set of statements. Figure 2 provides the summary of level of agreement with proposed statements for decision not to test. As depicted, the statement “already doing everything to lower risk” received the most endorsement (agree and strongly agree) among those unwilling to receive predictive testing. Approximately 42% of the participants endorsed each of the statements: “information would not be useful” and “don't believe the results of the genetic testing would change behavior.” However, only 16% of the unwilling participants endorsed the inaccuracy of test results as a hypothetical reason for not testing.

FIG. 2.

Participant responses to reasons for lack of interest in testing. Listed above each segment is the percentage (%) of participants who disagree strongly, disagree, are uncertain, agree, or strongly agree with proposed reasons for nonwillingness to test for genetic susceptibility to AD.

Concerns of genetic susceptibility testing

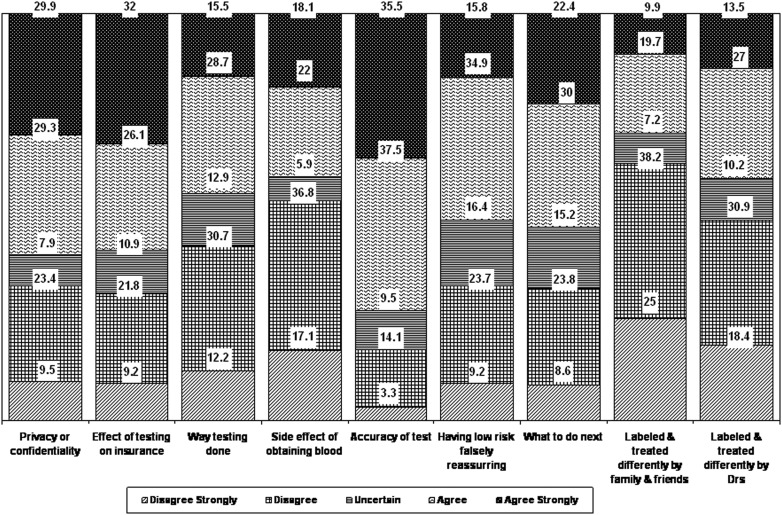

All participants, regardless of interest in genetic testing, responded to statements on methodological and ethical concerns about genetic susceptibility testing for risk of alcoholism (Fig. 3). The strongest concern about testing was the accuracy of testing (35.50%), followed by the effect of testing on insurance (32%), as well as privacy or confidentiality of testing (29.90%). The least concern was being labeled by family, friends, and doctors. Interestingly, 29% of the participants were concerned or strongly concerned about discrimination from family/friends; however, over 40% expressed corresponding concerns from discrimination by their physician.

FIG. 3.

Participant responses to concerns about genetic testing. Listed above each segment is the percentage (%) of participants who disagree strongly, disagree, are uncertain, agree, or strongly agree with proposed concerns on testing for genetic susceptibility to AD.

Relationship between perceived concerns and willingness to test

To examine the relationship between ethical, methodological concerns, and willingness to test, a multivariate analysis adjusting for sociodemographic covariates was completed. Table 2 summarizes the results of association between willingness to test (outcome variable) and degree of concern for each item, using strongly disagree as the reference level of concern. Significant associations with willingness to test were observed in four items: (1) way the testing was completed, (2) side effect of obtaining blood, (3) being falsely reassured by a low risk, and (4) what to do next. In the multivariate model, after adjusting for differences in education, income, and heavy drinking, all of the above concerns, except what to do next, remained significantly associated with willingness to test.

Table 2.

Influence of Concerns of Genetic Testing on Willingness to Test

| Unadjusted | Adjusteda | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Concerns | Response | Not willing to test (%) | Willing to test (%) | ORb | 95% CI | ORb | 95% CI |

| Privacy or confidentiality | |||||||

| Strongly disagree | 13.33 | 8.88 | 1 | — | 1 | — | |

| Disagree | 24.44 | 23.17 | 1.42 | 0.47–4.30 | 1.22 | 0.39–3.87 | |

| Uncertain | 4.44 | 8.49 | 2.87 | 0.52–15.77 | 2.83 | 0.50–16.09 | |

| Agree | 26.67 | 29.73 | 1.67 | 0.57–4.95 | 1.58 | 0.51–4.93 | |

| Agree strongly | 31.11 | 29.73 | 1.43 | 0.05–4.16 | 1.42 | 0.47–4.31 | |

| Effect of testing on insurance | |||||||

| Strongly disagree | 11.11 | 8.91 | 1 | — | 1 | — | |

| Disagree | 24.44 | 21.32 | 1.09 | 0.34–3.48 | 1.01 | 0.30–3.41 | |

| Uncertain | 8.89 | 11.24 | 1.58 | 0.38–6.55 | 1.61 | 0.37–7.01 | |

| Agree | 33.33 | 24.81 | 0.93 | 0.30–2.84 | 1.09 | 0.34–3.53 | |

| Agree strongly | 22.22 | 33.72 | 1.89 | 0.59–6.08 | 2.32 | 0.68–7.85 | |

| Way testing done | |||||||

| Strongly disagree | 20.00 | 10.85 | 1 | — | 1 | — | |

| Disagree | 40.00 | 29.07 | 1.34 | 0.54–3.33 | 1.33 | 0.52–3.40 | |

| Uncertain | 17.78 | 12.02 | 1.25 | 0.42–3.67 | 1.09 | 0.36–3.34 | |

| Agree | 11.11 | 31.78 | 5.27 | 1.63–17.06c | 4.61 | 1.38–15.42c | |

| Agree strongly | 11.11 | 16.28 | 2.70 | 0.82–8.90 | 2.23 | 0.65–7.60 | |

| Side effect of obtaining blood | |||||||

| Strongly disagree | 28.88 | 15.06 | 1 | — | 1 | — | |

| Disagree | 46.67 | 35.14 | 1.44 | 0.66–3.17 | 1.31 | 0.58–2.96 | |

| Uncertain | 6.67 | 5.79 | 1.67 | 0.42–6.69 | 1.78 | 0.42–7.55 | |

| Agree | 6.67 | 24.71 | 7.11 | 1.91–26.54c | 5.50 | 1.43–21.19c | |

| Agree strongly | 11.11 | 19.31 | 3.33 | 1.10–10.15c | 2.47 | 0.77–7.87 | |

| Accuracy of test | |||||||

| Strongly disagree | 2.22 | 3.47 | 1 | — | 1 | — | |

| Disagree | 22.22 | 12.74 | 0.37 | 0.04–3.26 | 0.36 | 0.04–3.32 | |

| Uncertain | 20.00 | 7.72 | 0.25 | 0.03–2.25 | 0.23 | 0.02–2.23 | |

| Agree | 28.89 | 39.00 | 0.86 | 0.10–7.38 | 0.68 | 0.08–6.15 | |

| Agree strongly | 26.67 | 37.07 | 0.89 | 0.10–7.64 | 0.78 | 0.09–7.04 | |

| Being falsely reassured by a low risk | |||||||

| Strongly disagree | 17.78 | 7.72 | 1 | — | 1 | — | |

| Disagree | 28.89 | 22.78 | 1.82 | 0.66–5.02 | 1.61 | 0.57–4.59 | |

| Uncertain | 11.11 | 17.37 | 3.60 | 1.05–12.38c | 2.62 | 0.73–9.33 | |

| Agree | 37.78 | 34.36 | 2.09 | 0.79–5.53 | 1.49 | 0.54–4.10 | |

| Agree strongly | 4.44 | 17.76 | 9.20 | 1.79–47.24c | 6.66 | 1.26–35.14c | |

| What to do next | |||||||

| Strongly disagree | 15.56 | 7.36 | 1 | — | 1 | — | |

| Disagree | 26.67 | 23.26 | 1.84 | 0.63–5.35 | 1.68 | 0.56–5.04 | |

| Uncertain | 22.22 | 13.95 | 1.33 | 0.44–4.04 | 1.26 | 0.40–3.99 | |

| Agree | 24.44 | 31.01 | 2.68 | 0.92–7.82 | 1.92 | 0.62–5.89 | |

| Agree strongly | 11.11 | 24.42 | 4.64 | 1.32–16.32c | 3.32 | 0.91–12.18 | |

| Labeled & treated differently by family and friends | |||||||

| Strongly disagree | 31.11 | 23.94 | 1 | — | 1 | — | |

| Disagree | 37.78 | 38.22 | 1.31 | 0.61–2.86 | 1.26 | 0.57–2.81 | |

| Uncertain | 2.22 | 8.11 | 4.74 | 0.59–38.27 | 4.09 | 0.50–33.51 | |

| Agree | 20.00 | 19.69 | 1.28 | 0.51–3.20 | 1.06 | 0.41–2.75 | |

| Agree strongly | 8.89 | 10.04 | 1.47 | 0.44–4.88 | 1.31 | 0.38–4.51 | |

| Labeled & treated differently by doctors | |||||||

| Strongly disagree | 17.78 | 18.53 | 1 | — | 1 | — | |

| Disagree | 31.11 | 30.89 | 0.95 | 0.37–2.44 | 1.14 | 0.43–3.02 | |

| Uncertain | 13.33 | 9.65 | 0.69 | 0.22–2.22 | 0.88 | 0.26–2.96 | |

| Agree | 26.67 | 27.03 | 0.97 | 0.37–2.56 | 1.04 | 0.38–2.82 | |

| Agree strongly | 11.11 | 13.90 | 1.20 | 0.36–3.98 | 1.39 | 0.40–4.77 | |

Adjusted for education, income, and heavy drinking.

The odds ratio, interpretable as the odds of providing a response other than the reference response “Strongly disagree.”

p<0.05.

Discussion

Interest in genetic testing for susceptibility to AD

This study examined the interest and concerns of genetic testing for susceptibility to AD among African Americans. It should be noted currently that there is no clinically valid genetic test available to indicate a predisposition to AD; however, if one was available, there would be a strong interest in testing (85%). This is a higher percentage than the participants who said that they would be interested in testing (63%) in the only previously published study that evaluated hypothetical genetic testing for alcoholism (Gamm et al., 2004b). One explanation for the different response could be that participants from this current study were a general community sample, whereas the participants from the previous study were at-risk persons of European descent who have family members with AD. The results of this current study, however, are similar to a recent study on attitudes toward genetic testing for psychiatric conditions among potential consumers, in which 83% of the participants expressed an interest to test (Laegsgaard et al., 2009), and to a previous study on the interest of genetic testing for nicotine addiction susceptibility, in which 84% of the respondents indicated that they would be interested in testing (Tercyak et al., 2006).

Within our study sample, participants with higher education and income were less willing to receive testing. Previous studies on heart disease and cancer in various ethnic groups have shown that higher (Sanderson et al., 2004) and lower (Thompson et al., 2003) educational levels are associated with an interest in genetic testing; however, the majority of these studies did not assess the interest of genetic testing of preventable multifactorial disorders with a social stigma. Perhaps, persons with high educational attainment are concerned about the potential pressure of unfavorable test results to their employment and insurance.

Heavy drinkers were more interested in genetic testing than persons who were not classified as heavy drinkers. Heavy drinkers might perceive that they are at an increased risk of becoming dependent on alcohol; therefore, they may consider modifying their drinking behavior based on their genetic risk assessment. To our knowledge, there are no other published reports on genetic susceptibility testing for alcohol based on the current drinking history, but a previous study on other multifactorial diseases found that perceived susceptibility is a strong indicator of interest in genetic testing (Laegsgaard et al., 2009).

Interestingly, we found no significant association between family history of AD and interest in susceptibility testing. This result agrees with the finding by Thombs et al. (1998), in which family history of AD was not a predictor of the intention to test. Perhaps, the participants of this study perceived that they had an increased genetic risk for AD and felt they were already taking action to reduce their risk, a reason the majority of unwilling participants endorsed for lack of enthusiasm.

Reasons for interest in genetic testing for the susceptibility to AD

Consistent with the study by Gamm et al. (2004b), which as mentioned above were at-risk participants of European descent, the reasons why participants were interested in genetic testing for the susceptibility AD were varied. In addition to curiosity and the perception that AD is a deadly disease, other major reasons centered around the usefulness of the information. Usefulness of the information was one of the major explanations as to why participants were interested in genetic testing for the susceptibility of nicotine dependence (Tercyak et al., 2006). It was thought that the results would affect smoking behavior. Gamm et al. (2004b) also noted that the most often perceived benefit of genetic testing for AD was the ability to carefully monitor one's own behavior.

The main explanation that participants were not interested in testing was because they thought they were already doing everything to lower their risk of becoming alcohol dependent and they did not think genetic testing would be useful to them; once again, agreeing with the results in the study by Gamm et al.

Concerns about genetic testing for the susceptibility to AD

The concerns about genetic testing for the susceptibility of AD can be categorized into methodological and ethical domains. Out of all the concerns, issues with testing methods, side effects of venipuncture, falsely reassuring results, and lack of guidelines on “what to do next” following test results were significantly associated with willingness to receive testing. The method of testing suggests that in this population, the offering of alternative methods of testing could affect a person's interest in testing. Determining what to do following a positive or negative result could possibly depend on the validity and predictability of the test. This was also noted by Gamm et al. (2004b), in which genetic determinism was deemed a concern if genetic risk results were high and false reassurance would be a concern if risk results were low.

Despite the prevalence of interest in susceptibility genetic testing, a significant portion of participants raised several concerns about the risk of testing. The privacy and effect of testing in insurance coverage were noted to be concerns of participants interested in testing and not interested in testing. As suggested in Hall and Olapode (2005) anxiety about possible privacy, stigmatization and discrimination may cause potential patients and physicians to avoid genetic services; therefore, the development of policies to address these issues should be considered before this testing is offered.

In summary, this current study revealed a high interest for genetic testing for the susceptibility of AD among African Americans, but also revealed reasonable concerns. Perhaps, the perceived benefits of the test outweighed the concerns in this study population.

This study can be interpreted in light of its strengths and limitations. The participants included a large community sample of African Americans from various socioeconomic levels. In addition, the survey was constructed in order that participants could answer questions posed to them, and they also had the opportunity to express further issues they considered important and the reasoning behind their answers.

There were a few limitations associated with this study. The genetic-related questions were evaluated using single items. The questions about genetic testing were very general and did not provide specific details about the test, such as the degree of certainty. In addition, since this study assessed hypothetical genetic testing for AD, the results might be an overestimation of the actual test interest once it becomes available. Previous studies on Mendelian disorders have shown that the actual uptake of testing is lower than the intention (Meiser and Dunn, 2000; Lerman et al., 2002).

Little consideration has been given to the interplay of race/ethnic variations of genetic testing for the susceptibility to AD. For instance, as mentioned above, the various race/ethnic groups presented in Gamm et al. (2004b) and our study demonstrated interest in genetic testing for the susceptibility to AD. However, further investigation is needed to assess the specificity of influence in various populations. Exploring the barriers and disadvantages of genetic testing among population will provide an understanding of factors associated with both interest and concerns. For instance, factors such as lifestyle, regional difference, medical privacy, and insurance status could be assessed in various ethnic groups. Further studies could also investigate the effect pleiotrophy might have on interest, since certain polymorphisms for the susceptibility of AD may be associated with other multifactorial disorders (bipolor disease, nicotine dependence). Finally, given that AD is a chronic disorder that evolves over a 5–10-year period and early age of onset of drinking is associated with increased risk of AD (Hingson et al., 2006; Scott et al., 2008), it would be interesting to conduct a similar study in adolescent children. The study could investigate whether personalized risk based on the genetic susceptibility could be used to dissuade young adults from experimenting with alcohol, thereby reducing their risk of becoming dependent.

In conclusion, despite the fact that genetic testing for the susceptibility to AD could raise additional ethical, legal, and social issues not associated with Mendelian disorders or other multifactioral diseases, the majority of the participants in this study were interested in testing. The results of this study could be utilized to assist healthcare professionals in developing education, counseling, genetic services, and policies.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported, in part, by the following grants from the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (NIAAA), U24AA11898, AA014643, Charles and Mary Latham Fund, and General Clinical Research Center (GCRC) grant M01-RR10284. The authors would like to acknowledge the support of Ms. Jennifer Ruchman and Dr. Verle Headings for their recommendations on the design of the study.

Author Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist.

References

- American Psychiatric Association (2000) Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (4th ed., text revision). Washington, DC. [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association (2013) Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (5th ed., text revision). Washington, DC. [Google Scholar]

- Andrykowski MA, Munn RK, Studt JL. (1996) Interest in learning of personal genetic risk for cancer: a general population survey. Prev Med 25:527–536 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bottorff JL, Ratner PA, Balneaves LG, et al. (2002) Women's interest in genetic testing for breast cancer risk: the influence of sociodemographics and knowledge. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 11:89–95 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bunn JY, Bosompra K, Ashikaga T, et al. (2002) Factors influencing intention to obtain a genetic test for colon cancer risk: a population based study. Prev Med 34:567–577 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cloninger CR, Bohman M, Sigvardsson S. (1981) Inheritance of alcohol abuse. Arch Gen Psychiatry 38:861–868 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dick DM, Edenberg HJ, Xuei X, et al. (2004) Association of GABRG3 with alcohol dependence. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 28:4–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gamm JL, Nussbaum RL, Biesecker BB. (2004a) Genetics and alcoholism among at-risk relatives I: perceptions of cause, risk and control. Am J Med Genet 128A:144–150 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gamm JL, Nussbaum RL, Biesecker BB. (2004b) Genetics and alcoholism among at-risk relatives II: interest and concerns about hypothetical genetic testing for alcoholism risk. Am J Med Genet 128A:151–155 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grant BF. (2000) Estimates of U.S. Children exposed to alcohol abuse and dependence in the family. Am J Pubic Health 90:112–115 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hall M, Olopade OL. (2005) Confronting genetic testing disparities. JAMA 293:1783–1785 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heath AC, Bocholz KK, Madden PA, et al. (1997) Genetic and environmental contributions to alcohol dependence risk in a national twin sample: consistency of findings in women and men. Psychol Med 6:1381–1396 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hingson RW, Heeren T, Winter MR. (2006) Age at drinking onset and alcohol dependence. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med 160:739–746 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hinrich AL, Wang JC, Bufe B, et al. (2006) Functional variant in a bitter-taste receptor (hTASR16) influences risk of alcoholism. Am J Hum Genet 78:103–111 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kash KM, Dabney MK. (2001) Psychological aspects of cancer screening in high-risk populations. Med Pediatr Oncol 36:519–524 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler L, Collier A, Brewster K, et al. (2005) Attitudes about genetic testing intentions in African women at increased risk for breast cancer. Genet Med 7:230–238 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kinney AY, Choi YA, DeVellis B, et al. (2000) Interest in genetic testing among first degree relatives of colorectal cancer patients. Am J Prev Med 18:249–252 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laegsgaard M, Kristensen A, Mors O. (2009) Potentional consumers' attitudes toward psychiatric genetic research and testing and factors influencing their intentions to test. Genet Test Mol Biomarkers 13:57–65 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lerman C, Croyle R, Tercyak K, Hamann H. (2002) Genetic testing: psychological aspects and implications. J Consul Clin Psychol 70:784–797 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marshall VJ, Kalu N, Kwagyan J, et al. (2012) Perceptions about genetic testing for the susceptibility of alcohol dependence and other multifactorial diseases. Genet Test Mol Biomarkers 16:476–481 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meiser B, Dunn SM. (2000) Psychological impact of genetic testing for Huntington disease: an update of the literature for clinicians. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 69:574–578 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murayama M, Matsushita S, Muramatsu T. (1998) Clinical characteristics and disease course of alcoholism with inactive aldehyde dehydrogenase 2. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 22:524–527 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sander T, Harms H, Lesch KP, et al. (1997) Association analysis of a regulatory variation of the serotoin transporter gene with severe alcohol dependence. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 21:1356–1359 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanderson SC, Wardle J, Jarvis MJ, Humphries SE. (2004) Public interest in genetic testing for susceptibility to heart disease and cancer: a population-based survey in the UK. Prev Med 39:458–464 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schuckit MA. (2000) Genetics of the risk for alcoholism. Am J Addict 9:103–112 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scott DM, Bland WP, Cain GE, et al. (2008) Clinical course of alcohol dependence in African Americans. J Addict Dis 27:43–50 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith KR, Croyle RT. (1995) Attitudes toward genetic testing for colon cancer risk. Am J Public Health 85:1435–1438 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith EN, Bloss CS, Badner JA, et al. (2009) Genome-wide association study of bipolar disorder in European American and African American individuals. Mol Psychiatry 14:755–763 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tercyak KP, Peshkin BN, Wine LA, Walker LR. (2006) Interest of adolescents in genetic testing for nicotine susceptibility. Prev Med 42:60–65 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thombs DL, Mahoney CA, Olds RS. (1998) Application of a bogaus testing procedure to determine college students utilization of genetic screening. Coll Health 47:103–112 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson HS, Valdimarsdottir HB, Jandorf L, Reed W. (2003) Perceived disadvantages and concerns about abuses of genetic testing for cancer risk: differences across African American, Latina and Caucasian women. Patient Educ Couns 51:217–227 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wall TL, Ehlers CL. (1995) Genetic influences affecting alcohol use among Asians. Alcohol Health Res World 19:184–189 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]