Abstract

BACKGROUND

Randomized controlled trials have demonstrated the efficacy of selected beta blockers for preventing cardiovascular (CV) events in patients following myocardial infarction (MI) or with heart failure (HF). However, the effectiveness of beta blockers for preventing CV events in patients with hypertension has been questioned recently, but it is unclear whether this is a class effect.

METHODS

Using electronic medical record and health plan data from the Cardiovascular Research Network Hypertension Registry, we compared incident MI, HF, and stroke in patients who were new beta blocker users between 2000–2009. Patients had no history of CV disease and had not previously filled a prescription for a beta blocker. Cox proportional hazards regression was used to examine the associations of atenolol and metoprolol tartrate with incident CV events using both standard covariate adjustment (N=120,978) and propensity matching methods (N=22,352).

RESULTS

During follow-up (median 5.2 years), there were 3,517 incident MI, 3,272 incident HF, and 3,664 incident stroke events. Hazard rate ratios for MI, HF and stroke in metoprolol users were 0.99 (95% confidence interval 0.97–1.02), 0.99 (95% CI 0.96–1.01), and 0.99 (95% CI 0.97–1.02), respectively. An alternative approach using propensity score matching yielded similar results in 11,176 new metoprolol tartrate users who were similar to 11,176 new atenolol users with regard to demographic and clinical characteristics.

CONCLUSIONS

There were no statistically significant differences in incident CV events between atenolol and metoprolol tartrate users with hypertension. Large registries similar to the one used in this analysis may be useful for addressing comparative effectiveness questions that are unlikely to be resolved by randomized trials.

INTRODUCTION

Beta blockers are widely used in the treatment of hypertension and are one of the drug classes recommended as initial treatment in hypertension guidelines based on reduction of morbidity and mortality in placebo-controlled trials.1–5 However, following the publication of two large trials that found atenolol-based regimens less effective than other antihypertensive drugs for prevention of cardiovascular (CV) events in patients with hypertension,6–7 the first-line status of beta blockers has increasingly been called into question.3, 8–11 A recent meta-analysis including these studies found that beta blockers were inferior to other agents primarily with regard to stroke prevention, but the authors and editorialist pointed out that data on beta blockers other than atenolol were sparse enough that it is unclear whether this conclusion applies to the entire beta blocker class.9, 12 A second meta-analysis and editorial echoed these findings and concerns.11, 13

Within the drug class of beta-blockers, there are differences in pharmacokinetic properties.14–15 Differences in lipophilicity, bioavailability, and metabolism between atenolol and metoprolol may have relevance for protecting the heart.10–11 Despite these differences, it is unlikely that they will be compared head-to-head in a randomized controlled trial. Therefore, we sought to compare the effectiveness of two commonly used beta blockers, using data from a hypertension registry from 3 large integrated health care delivery systems. We compared the incidence of myocardial infarction (MI), stroke, and heart failure in adult hypertensive patients who were new users of atenolol and metoprolol tartrate.

METHODS

Study Setting and Registry Population

This report is derived from the Hypertension Registry of the Cardiovascular Research Network (CVRN). The registry includes all adult patients identified with hypertension between 2000 and 2009 at 3 large integrated healthcare delivery systems: HealthPartners of Minnesota, Kaiser Permanente Colorado, and Kaiser Permanente Northern California. Electronic data on longitudinal blood pressure measurements, prescription drugs, laboratory test results, diagnoses, and healthcare utilization was available from electronic health records (EHR) and administrative databases at all sites. Data from each of the health plans were restructured into a common, standardized format with identical variable names, definitions, labels, and coding.

We defined hypertension using criteria adapted from previous CVRN studies16–20 based on outpatient blood pressure readings, diagnostic codes from outpatient and hospital records, pharmacy prescriptions, and laboratory results. Patients entered the registry on the date they first met one (or more) of the following criteria: 1) two consecutive elevated blood pressure measurements (i.e., ≥ 140 mm Hg systolic and/or ≥90 mm Hg diastolic, or ≥130/80 mm Hg in the presence of diabetes mellitus or chronic kidney disease); 2) two diagnostic codes for hypertension (ICD-9-CM codes: 401.x – 405.x) recorded on separate dates; 3) one diagnostic code for hypertension plus prescription for an antihypertensive medication; or 4) one elevated blood pressure measurement plus one diagnostic code for hypertension. Blood pressure readings from emergency and urgent care settings were excluded because they were found to be consistently higher than other ambulatory measurements in the same patients in similar time periods. In order to confirm that the algorithms designed to identify hypertensive patients were valid and that the analytic data accurately reflected the source data, we conducted a chart review of 450 randomly selected charts (150 from each site). We confirmed that hypertension was in fact incident on the date assigned by the algorithm in 96% of cases and agreement on blood pressure values between the electronic database and chart records was 98%.

Variables Used in Analysis

Patient age and sex were available for all patients from membership databases. Race/ethnicity was obtained from outpatient registration data, hospital discharge records, member satisfaction surveys, and other research survey datasets, and was available for 85% of cohort members. Systolic and diastolic blood pressures measured within 2 months prior to the initiation of a beta blocker and approximately 6 months (+/− 60 days) after the initiation of a beta blocker were included. Pharmacy records were used to identify dates of treatment with beta blockers and other antihypertensive drug classes used within 90 days of starting the beta blocker.

Cardiovascular disease was identified using diagnoses and procedure codes from inpatient and ambulatory records. These included ischemic heart disease (ICD-9-CM diagnosis codes 410.xx–414.xx); stroke (diagnosis codes 430.xx–434.xx, 436.xx, 852.0, 852.2. 852.4, 853.0); peripheral vascular disease (diagnosis codes 441.3 – 441.7, 443.9, 444.0, 444.2); and congestive heart failure (diagnosis codes 428.xx, 402.xx, 398.91). Incident MI (ICD-9-CM code 410.xx), HF and stroke events were defined using the primary ICD-9 codes from a discharge from an inpatient stay.

Other comorbidities included in the analysis were diabetes, chronic kidney disease (CKD) and lipid disorders. Diabetes was defined by: a) two outpatient diagnoses or one primary inpatient discharge diagnosis of diabetes (ICD-9-CM Code 250.x); or b) prescription for any anti-diabetic medication other than metformin or thiazolidinediones; or c) prescription for metformin or a thiazolidinedione plus a diagnosis of diabetes; or d) hemoglobin A1c value >7% or two fasting plasma glucose values ≥ 126 mg/dL on separate dates. CKD was defined as two consecutive serum creatinine values that yield estimated glomerular filtration rates (eGFRs) <60 ml/min; or by an ICD-9 diagnostic code for CKD (ICD-9-CM codes: 585.1–585.9). Lipid disorders were identified by ICD-9-CM codes 272.x.

Study Population

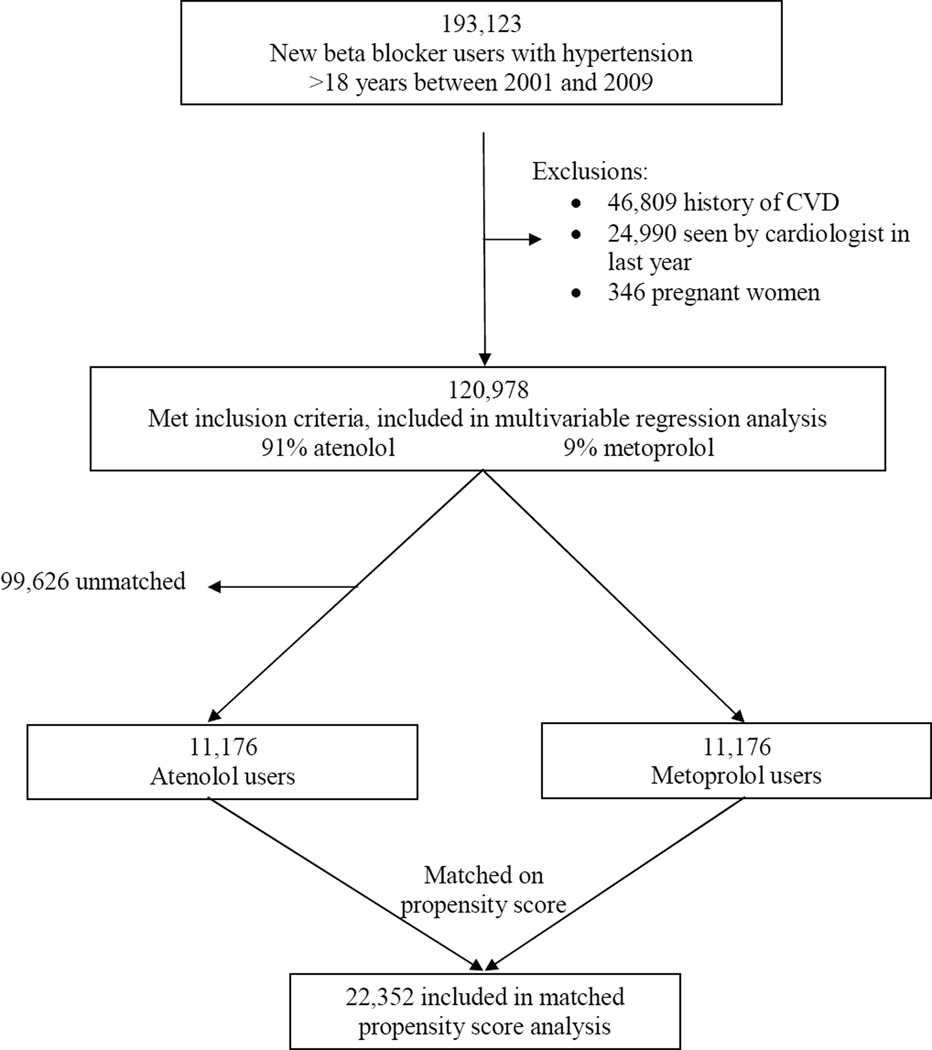

We employed a new user design, which restricts the analysis to persons under observation at the start of the current course of treatment.21 The study population included all patients 18 years or older with hypertension during 2000–2009 who were started on either atenolol or metoprolol tartrate after the date of first diagnosis with no prior use of any beta blocker for at least 12 months (n=193,123). Previous use of any other class of antihypertensive drug was not an exclusion. Prescription databases were searched as far back as 1996 or to health plan enrollment if that occurred after 1996. Other beta blockers, including metoprolol succinate, were not used frequently enough during the years of the study to be included in the analysis. We excluded pregnant women (n=346). Additionally, we excluded 46,809 patients who had evidence of CVdisease before starting atenolol or metoprolol tartrate. These exclusions were based on the CV diagnosis codes described above as well as procedure codes for cardiac bypass surgery (CPT codes 33510–23, 33533–36 and percutaneous coronary interventions (CPT codes 92980–92996). In order to exclude patients with suspected CV disease, we also excluded 24,990 patients with a visit to cardiology specialist within the year prior to starting the beta blocker, leaving 120,978 patients for this analysis (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Selection of patients for analyses.

Statistical Analysis

All statistical analyses were completed using SAS v9.2 (SAS Institute, Inc, Cary, NC). Baseline characteristics were compared between patients started on atenolol versus metoprolol tartrate using means and standard deviations for continuous variables and percents for categorical and binary variables. Cox proportional hazards models were used to compare time to outcome events between atenolol and metoprolol tartrate. Follow-up time was computed in days from the day following the first dispensing of the new beta blocker to the date of the first observed outcome event, termination of enrollment or December 31, 2009, whichever occurred first. Patients who were lost to follow up were censored at the last point of contact. Multivariable models were adjusted for year of beta blocker initiation, age, gender, number of visits in prior year, systolic BP at start of beta blocker, lipid disorder, diabetes, chronic kidney disease, and use of other antihypertensive medications. In a supplemental analysis of 68,882 patients in whom we had follow-up blood pressure data, we used linear regression to examine the effect of atenolol and metoprolol on systolic and diastolic blood pressure lowering 6 months after the start of the beta blocker.

Because this is an observational study and patients were not randomized to receive either treatment, we also used alternative strategies to minimize confounding by indication. In order to minimize confounding by indication, we also ran a conditional logistic regression matched on propensity score. A logistic model (which included all the variables in Table 1 except for diastolic blood pressure), was used to generate a propensity score for the probability of being prescribed metoprolol. We then used a 5 digit greedy 1:1 matching algorithm22 to match metoprolol users to atenolol users based on propensity score. After conducting the propensity matching, there were 99,626 unmatched patients leaving 22,352 matched patients for statistical analyses of adverse cardiovascular events and 13,908 matched patients with 6 month follow-up blood pressures for the analyses of blood pressure lowering. The selection of patients for the analyses in shown in Figure 1. A second alternative strategy was to conduct a sensitivity analysis excluding patients who had events in the first 12 months of follow-up so as to exclude those with CV disease not excluded by diagnosis codes or visits to a cardiologist that could have had an impact on prescribing behavior.

Table1.

Descriptive Characteristic of patients initiating beta blocker us, 20012013;2007 the CVRN Hypertension Registry

| Total (n=120,978) |

Matched (n=22,352) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Means (SD) or % | Atenolol 109,798 |

Metoprolol 11180 |

Atenolol 11176 |

Metoprolol 11176 |

| Year of beta blocker initiation, % | ||||

| 2000 | 14 14 | 10 | 8 7 | 10 |

| 2001 | 11 | 6 | 7 | 6 |

| 2002 | 15 | 9 | 9 | 9 |

| 2003 | 15 | 10 | 10 | 10 |

| 2004 | 14 | 12 | 12 | 12 |

| 2005 | 12 | 15 | 16 | 15 |

| 2006 | 10 | 16 | 16 | 16 |

| 2007 | 8 | 14 | 14 | 14 |

| 2008 | 2 | 5 | 5 | 5 |

| 2009 | 2 | 4 | 4 | 4 |

| Age, mean (SD), y | 60.8 (13.0) | 65.1 (13.6) | 65.0 (13.4) | 65.2 (13.6) |

| Age Category (%) | ||||

| <50 yrs | 20 | 13 | 14 | 13 |

| 50–59 | 27 | 21 | 20 | 21 |

| 60–69 | 25 | 25 | 25 | 25 |

| 70–79 | 20 | 26 | 26 | 26 |

| 80+ | 7 | 15 | 15 | 15 |

| Male, % | 43 | 44 | 43 | 44 |

| Race/ethnicity, % | ||||

| White | 62 | 66 | 63 | 66 |

| African-American | 10 | 11 | 12 | 11 |

| Asian | 9 | 7 | 8 | 8 |

| Hispanic non-white | <1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Other/multi/unknown | 19 | 14 | 15 | 14 |

| Median Ambulatory Visits in Prior Year | 5.0 | 7.0 | 7.0 | 7.0 |

| Insurance payer, % | ||||

| Commercial | 79 | 71 | 70 | 71 |

| Government | 21 | 29 | 28 | 29 |

| Systolic BP at Start of Beta Blocker, mm Hg | 148.5 (20.2) | 144.0 (21.5) | 144.8 (20.4) | 144.0 (21.5) |

| Diastolic BP at Start of Beta Blocker, mm Hg | 84.5 (13.2) | 82 (12.5) | 82.1 (12.6) | 80.9 (12.9) |

| Lipid Disordera, % | 32 | 42 | 47 | 42 |

| Diabetesb, % | 21 | 31 | 30 | 30 |

| Chronic Kidney Diseasec, % | 12 | 28 | 28 | 28 |

| ACE or ARB use within 6 months prior to beta blocker initiation, % | 36 | 46 | 47 | 46 |

| Calcium channel blocker use within 6 months prior to beta blocker initiation, % | 14 | 23 | 17 | 23 |

| Diuretic use within 6 months prior to beta blocker initiation, % | 51 | 49 | 54 | 49 |

| Other anti-hypertensive Medication use within 6 months prior to beta blocker initiation, % | 7 | 13 | 9 | 13 |

| Count of anti-hypertensive medications within 6 months prior to beta blocker initiation | ||||

| 0 | 32 | 26 | 26 | 26 |

| 1 | 26 | 31 | 32 | 31 |

| 2 | 26 | 30 | 32 | 30 |

| 3 | 6 | 11 | 8 | 11 |

| 4 | <1 | 2 | 1 | 2 |

Note: percents may not add to 100 because of rounding.

Lipid disorders were identified by ICD-9-CM codes 272.x

Diabetes was defined by: a) two outpatient diagnoses or one primary inpatient discharge diagnosis of diabetes (ICD-9-CM Code 250.x); or b) prescription for any anti-diabetic medication other than metformin or thiazolidinediones; or c) prescription for metformin or a thiazolidinedione plus a diagnosis of diabetes; or d) hemoglobin A1c value >7% or two fasting plasma glucose values ≥ 126 mg/dL on separate dates.

Chronic kidney disease (CKD) was defined as two consecutive serum creatinine values that yield estimated glomerular filtration rates (eGFRs) <60 cc/min when the MDRD equation (11) is applied; or by an ICD-9 diagnostic code for CKD (ICD-9-CM codes: 585.1–585.9).

RESULTS

The baseline characteristics for this cohort of new beta blocker users are shown in Table 1. A total of 120,978 patients without history of cardiovascular disease events from the CVRN Hypertension Registry initiated treatment with either atenolol or metoprolol between 2000–2009. During this period atenolol was used in about 10-fold more patients than metoprolol tartrate. Patients who filled a prescription for metoprolol tended to be older, have a government insurance payer, and have more ambulatory visits. Metoprolol users had slightly lower systolic and diastolic blood pressures at the start of beta blocker treatment, were more likely to be on other anti-hypertensive medications and more often had lipid disorders, diabetes and chronic kidney disease.

During the follow-up period (median 5.2 years), there were 3,517 incident MIs, 3,272 incident HF hospitalizations, and 3,664 incident strokes. Multivariable Cox proportional hazards regression yielded hazard ratios of 0.99, 0.99, 0.99, and 0.98 and narrow confidence intervals that included the null value for MI, HF, stroke, and any CV event, respectively (Table 2). In the propensity-matched Cox proportional hazards models, the hazard ratios for MI, HF, stroke, and any CV event were virtually identical to the multivariable results with narrow confidence intervals that included the null value (Table 2). In sensitivity analyses excluding patients who had events in the first 12 months of follow-up, the hazard ratios were virtually unchanged (data not shown).

Table 2.

Incident cardiovascular events associated with metoprolol tartrate compared with atenolol.

| Multivariablea | Propensity Matchedb | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. of Events |

Person years |

Hazard Ratio |

95% CI | No. of Events |

Person years |

Hazard Ratio |

95% CI | |

| MI | 3517 | 631,403 | 0.99 | (.97 to 1.01) | 712 | 94,261 | .99 | (.97 to 1.02) |

| HF | 3272 | 633,987 | .99 | (.97 to 1.01) | 831 | 94,257 | .99 | (.96 to 1.01) |

| Stroke | 3664 | 632,386 | .99 | (.97 to 1.01) | 773 | 94,346 | .99 | (.97 to 1.02) |

| Any CV event | 9353 | 616028 | .98 | (.99 to 1.00) | 2064 | 91,191 | .98 | (.95 to 1.00) |

Multivariate model adjusted for year of beta blocker initiation, age, gender, number of visits in prior year, systolic BP at start of bb, lipid disorder, diabetes, chronic kidney disease, and if on other anti hypertensive medications.

Matched on propensity score. Propensity score adjusted for year of beta blocker start year, age, gender, number of visits in prior year, systolic BP at start of beta blocker, lipid disorder, diabetes, chronic kidney disease, and if on other anti hypertensive medications.

Estimates and standard errors of the supplemental analysis of blood pressure lowering effects of the two beta blockers in the subgroup with follow-up measures are shown in Table 3. In multivariable analysis of new beta blocker users, at baseline there were statistically significant differences between atenolol and metoprolol users in systolic blood pressures (149 and 145 mm Hg, respectively, p= <.0001) and diastolic blood pressures (84 and 83, respectively, p<.0001). At 6 months follow-up, systolic blood pressures were 137 and 138 in the atenolol and metoprolol patients, respectively (p=0.8163). Diastolic blood pressure at 6 months was 77 and 78 in the atenolol and metoprolol patients, respectively (p=0.0047). There was no difference in change in systolic blood pressure, and a small, but statistically significant difference in change in diastolic blood pressure (5.9 and 5.5 for atenolol and metoprolol, respectively p=.0047). The propensity-matched analysis of blood pressure lowering had similar results comparing new atenolol and metorpolol tartrate users in systolic (144 and 143 mm Hg, respectively, p=0.0073) and diastolic blood pressures (81 and 80, respectively, p<.0001). At 6 months follow-up, there were no statistically significant differences between atenolol and metoprolol tartrate users in systolic or diastolic blood pressure. In the propensity matched model, the mean blood pressure lowering was slightly greater in atenolol verses metorpolol tartrate users (8 and 7 mm Hg, respectively, p = 0.0152). Atenolol lowered diastolic BP slightly more than metoprolol (5 and 3 mm Hg, respectively, p <.0001).

Table 3.

Comparison of blood pressure lowering effects at 6 months in new beta blocker users.

| Multivariablea linear regression | Propensity-matchedb linear regression | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Blood pressure estimate (standard error) |

Atenolol n=61,869 |

Metoprolol tartrate n=7,013 |

p | Atenolol n=6,907 |

Metoprolol tartrate n=7010 |

p |

| Baseline SBP and DBP | ||||||

| SBP | 148.5 (0.25) | 145.4 (0.33) | <.0001 | 144.2 (0.25) | 143.3 (0.25) | 0.0073 |

| DBP | 84.2 (0.15) | 82.5 (0.20) | <.0001 | 81.3 (0.15) | 80.2 (0.15) | <.0001 |

| SBP and DBP at 6 months post beta blocker initiation | ||||||

| SBP | 137.4 (0.23) | 137.5 (0.30) | 0.8163 | 136.5 (0.23) | 136.6 (0.23) | 0.8460 |

| DBP | 77.3 (0.13) | 77.7 (0.17) | 0.0047 | 76.6 (0.13) | 76.7 (0.13) | 0.4066 |

| Change in SBP and DBP over 6 months follow-up | ||||||

| SBP | 9.8 (0.23) | 9.8 (0.30) | 0.8163 | 7.7 (0.29) | 6.7 (0.29) | 0.0152 |

| DBP | 5.9 (0.13) | 5.5 (0.17) | 0.0047 | 4.7 (0.16) | 3.4 (0.16) | <.0001 |

Multivariable model adjusted for year of beta blocker initiation, age, gender, number of visits in prior year, systolic BP at start of bb, lipid disorder, diabetes, chronic kidney disease, and if on other anti hypertensive medications.

Matched on propensity score. Propensity score adjusted for year of beta blocker initiation, start year, age, gender, number of visits in prior year, systolic BP at start of beta blocker, lipid disorder, diabetes, chronic kidney disease, and if on other anti hypertensive medications.

DISCUSSION

The objective of this study was to assess the comparative effectiveness of two beta blockers, atenolol and metoprolol tartrate, in patients without a history of cardiovascular disease. This study is among the first to address this important clinical question. In this retrospective cohort study comparing patients initiating beta blocker treatment with either atenolol or metoprolol tartrate, there were no statistically significant differences in rates of incident MI, HF, or stroke after adjusting for potential confounders. Additionally, there were no statistically significant differences in systolic blood pressure lowering effects comparing atenolol and metoprolol tartrate.

Until recently, beta blockers had been widely recommended as first-line therapy for hypertension,1–5 but many of the trials supporting their use had given investigators the choice of using either a thiazide diuretic or beta blocker alone or in combination as “conventional therapy”. The combination compared favorably against other antihypertensive drugs classes for prevention of CV events.1, 23 The use of beta blockers as first-line therapy has recently been challenged based on evidence of a weak effect on stroke,24 and the absence of an effect on CHD24–26 compared with placebo, as well as inferiority compared with other treatments for total mortality, CHD, and stroke.6–7, 27 Meta-analyses and a Cochrane review of recent trials that looked specifically at beta blockers used as monotherapy or as the first-line drug in a stepped care approach concluded that the evidence did not support use of beta blockers as first line therapy.11 Based on these findings, recently issued guidelines have relegated beta blockers to third- or fourth-line treatment for uncomplicated hypertension.28

Beta blockers differ in selectivity for the β1 and β2 and α adrenergic receptors, lipophilicity, penetration across the blood-brain barrier, duration of action, vasodilation properties and type 3 antiarrhythmic activity.14–15, 29 Different types of beta blockers may be indicated depending on patient profiles and tolerances. Given that most of the evidence comes from trials where atenolol was the beta blocker used,11 it is unclear if the observed effects of beta blockers in comparison to other antihypertensive medications are due to properties of atenolol or the entire class of beta blockers. However, there have been no trials comparing the different sub-types of beta blockers. While both atenolol and metoprolol tartrate are both β1-adrenergic receptors, they differ in lipophilicity, bioavailability, and metabolism.10–11, 30 Metoprolol is lipid soluble, tends to have highly variable bioavailability and short plasma half-life. In contrast, atenolol is more water soluble, shows less variance in bioavailability and has longer plaasma half-life. Despite these differences, both drugs have the effect of increasing vagal tone and causing a reduction in sympathetic outflow, likely via peripheral beta adrenergic blockade.31–32 Our findings that there are no differences between atenolol and metoprolol tartrate in event rates and effectiveness at blood pressure lowering in a cohort of adults without prior cardiovascular events suggest that the unfavorable trial data with atenolol may also apply to other beta blockers.

As with any observational study, there are potential limitations and caveats. We were unable to compare atenolol to any beta blocker other than metoprolol tartrate due to low usage of other agents in our study population during the years of observation. The use of metoprolol succinate, a once-daily drug that may have better adherence rates compared to twice-daily metoprolol tartrate, has been increasing due to the availability of generic versions in recent years, but the shift away from beta blockers after 2007 may make comparative effectiveness analyses more difficult.

Most importantly, patients were not randomly assigned to treatment with either atenolol or metoprolol tartrate. The decision on the part of the clinician to choose one drug over another may be related to patient characteristics associated with blood pressure control or cardiovascular risk or physician characteristics associated with differences in quality of care. In order to reduce the potential bias related to confounding by indication, we took two approaches: 1) we employed a new user design21, 33 and restricted the sample to those patients with no evidence of diagnosed or suspected cardiovascular disease33; and 2) we used propensity score matching to ensure that patients were comparable with regard to baseline covariates and the probability of receiving each treatment.

Despite these robust methods, no observational study can rule out the impact of unmeasured confounding. If unmeasured variables associated with poorer prognosis were more common in patients prescribed metoprolol, it could mask a beneficial effect of metoprolol. We excluded patients who had seen a cardiologist in the 12 months prior to beta blocker initiation, but this strategy may have been insufficient to rule out suspected CVdisease. However, in a recent study using data from one of the study sites, we found no evidence of suspected heart disease in audits of physician chart notes in 240 patients lacking specific ICD-9 codes for heart disease (410–414, 420–429).34 Other important potential unmeasured confounders that are not available in electronic medical records include behavioral or environmental risk factors, such as poor diet, low level of physical activity, or exposure to second hand smoke, although we have no reason to believe that patients with these risk factors would be more likely to be prescribed metoprolol rather than atenolol.

In conclusion, we found no differences in cardiovascular event rates or blood pressure lowering comparing patients without history of cardiovascular events who were initiating treatment with either atenolol or metoprolol tartrate. These findings suggest that hypertension trial outcomes with atenolol may not relate to unfavorable characteristics of this particular drug. These results should be interpreted cautiously as there have been no trials comparing these two beta blockers directly.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This project was funded by the National Heart Lung and Blood Institute, grant NIH/NHLBI/U19 HL091179 (Alan Go, Principal Investigator) and subcontract to HealthPartners Research Foundation (Patrick O’Connor, Site Principal Investigator).

Footnotes

There are no financial disclosures.

REFERENCES

- 1.Turnbull F. Effects of different blood-pressure-lowering regimens on major cardiovascular events: results of prospectively-designed overviews of randomised trials. Lancet. 2003 Nov 8;362(9395):1527–1535. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(03)14739-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Psaty BM, Smith NL, Siscovick DS, et al. Health outcomes associated with antihypertensive therapies used as first-line agents: A systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA. 1997;277:739–745. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Messerli FH, Grossman E, Goldbourt U. Are beta-blockers efficacious as first-line therapy for hypertension in the elderly? JAMA. 1998;279:1903–1907. doi: 10.1001/jama.279.23.1903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mancia G, De Backer G, Dominiczak A, et al. 2007 Guidelines for the management of arterial hypertension: The Task Force for the Management of Arterial Hypertension of the European Society of Hypertension (ESH) and of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) Eur. Heart J. 2007 Jun;28(12):1462–1536. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehm236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chobanian A, Bakris G, Black H, et al. The Seventh Report of the Joint National Committee on Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Pressure: The JNC 7 Report. JAMA. 2003;289:2560–2571. doi: 10.1001/jama.289.19.2560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dahlof B, Devereux R, Kjeldsen S, et al. Cardiovascular morbidity and mortality iin the Losartan Intervention For Endpoint reduction in hypertension study (LIFE): a randomised trial against atenolol. The Lancet. 2002;359:995–1003. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)08089-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dahlof B, Sever PS, Poulter NR, et al. Prevention of cardiovascular events with an antihypertensive regimen of amlodipine adding benazepril as required versus atenolol adding bendroflumethazide as required, in the Anglo-Scandinavian Cardiac Outcomes Trial - Blood Pressure Lowering Arm (ASCOT-BPLA): a multicentre randomized controlled trial. The Lancet. 2005;366:895–906. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)67185-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Messerli FH, Beevers DG, Franklin SS, Pickering TG. beta-Blockers in hypertension-the emperor has no clothes: an open letter to present and prospective drafters of new guidelines for the treatment of hypertension. Am J Hypertens. 2003 Oct;16(10):870–873. doi: 10.1016/s0895-7061(03)01017-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lindholm LH, Carlberg B, Samuelsson O. Should beta blockers remain first choice in the treatment of primary hypertension? A meta-analysis. Lancet. 2005 Oct-Nov;366(9496):1545–1553. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)67573-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ong HT. Beta blockers in hypertension and cardiovascular disease. BMJ. 2007 May 5;334(7600):946–949. doi: 10.1136/bmj.39185.440382.47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wiysonge CS, Bradley H, Mayosi BM, et al. Beta-blockers for hypertension. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2007;(1):CD002003. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD002003.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Beevers DG. The end of beta blockers for uncomplicated hypertension? Lancet. 2005 Oct-Nov;366(9496):1510–1512. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)67575-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Massie BM. Review: Available evidence does not support the use of beta blockers as first line treatment for hypertension. Evid Based Med. 2007 Aug;12(4):112. doi: 10.1136/ebm.12.4.112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Reid JL. Optimal features of a new beta-blocker. Am Heart J. 1988 Nov;116(5 Pt 2):1400–1404. doi: 10.1016/0002-8703(88)90130-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Drayer DE. Lipophilicity, hydrophilicity, and the central nervous system side effects of beta blockers. Pharmacotherapy. 1987;7(4):87–91. doi: 10.1002/j.1875-9114.1987.tb04029.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ho PM, Zeng C, Tavel HM, et al. Trends in first-line therapy for hypertension in the Cardiovascular Research Network Hypertension Registry, 2002–2007. Arch. Intern. Med. 2010 May 24;170(10):912–913. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2010.102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Magid DJ, Shetterly SM, Margolis KL, et al. Comparative effectiveness of angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors versus beta-blockers as second-line therapy for hypertension. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2010 Sep;3(5):453–458. doi: 10.1161/CIRCOUTCOMES.110.940874. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Schmittdiel J, Selby JV, Swain B, et al. Missed opportunities in cardiovascular disease prevention?: low rates of hypertension recognition for women at medicine and obstetrics-gynecology clinics. Hypertension. 2011 Apr;57(4):717–722. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.110.168195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Selby JV, Lee J, Swain BE, et al. Trends in time to confirmation and recognition of new-onset hypertension, 2002–2006. Hypertension. 2010 Oct;56(4):605–611. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.110.153528. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Selby JV, Peng T, Karter AJ, et al. High rates of co-occurrence of hypertension, elevated low-density lipoprotein cholesterol, and diabetes mellitus in a large managed care population. Am J Manag Care. 2004 Feb;10(2 Pt 2):163–170. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ray WA. Evaluating Medication Effects Outside of Clinical Trials: New-User Designs. Am. J. Epidemiol. 2003 Nov 1;158(9):915–920. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwg231. 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Parsons L. Proceedings of the Twenty-Sixth Annual SAS Users group International Conference. Cary, NC: SAS Institute, Inc; 2001. Reducing bias in a propensity score matched-pair sample using greedy matching techniques; pp. 214–226. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Blood Pressure Lowering Treatment Trialists’ Collaboration. Effects of ACE inhibitors, calcium antagonists, and other bloodpressure-lowering drugs: Results of prospectively designed overviews of randomised trials. The Lancet. 2000;355:1955–1964. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(00)03307-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Coope J, Warrender TS. Randomised trial of treatment of hypertension in elderly patients in primary care. Br. Med. J. (Clin. Res. Ed) 1986 Nov 1;293(6555):1145–1151. doi: 10.1136/bmj.293.6555.1145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.MRC trial of treatment of mild hypertension: principal results. Medical Research Council Working Party. Br. Med. J. (Clin. Res. Ed) 1985 Jul 13;291(6488):97–104. doi: 10.1136/bmj.291.6488.97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cardiovascular risk and risk factors in a randomized trial of treatment based on the beta-blocker oxprenolol: the International Prospective Primary Prevention Study in Hypertension (IPPPSH). The IPPPSH Collaborative Group. J. Hypertens. 1985 Aug;3(4):379–392. doi: 10.1097/00004872-198508000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.MRC Working Party. Medical Research Council trial of treatment of hypertension in older adults: principal results. BMJ. 1992;304:405–412. doi: 10.1136/bmj.304.6824.405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.NICE Clinical Guideline 127 - Hypertension: clinical management of primary hypertension in adults. London: National Insititue for Health and Clinical Excellence; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Weber MA. The role of the new beta-blockers in treating cardiovascular disease. Am. J. Hypertens. 2005 Dec;18(12 Pt 2):169S–176S. doi: 10.1016/j.amjhyper.2005.09.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wikstrand J, Kendall M. The role of beta receptor blockade in preventing sudden death. Eur. Heart J. 1992 Sep;13(Suppl D):111–120. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sandrone G, Mortara A, Torzillo D, La Rovere MT, Malliani A, Lombardi F. Effects of beta blockers (atenolol or metoprolol) on heart rate variability after acute myocardial infarction. Am. J. Cardiol. 1994 Aug 15;74(4):340–345. doi: 10.1016/0002-9149(94)90400-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tuininga YS, Crijns HJ, Brouwer J, et al. Evaluation of importance of central effects of atenolol and metoprolol measured by heart rate variability during mental performance tasks, physical exercise, and daily life in stable postinfarct patients. Circulation. 1995 Dec 15;92(12):3415–3423. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.92.12.3415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Psaty BM, Siscovick DS. Minimizing bias due to confounding by indication in comparative effectiveness research: the importance of restriction. JAMA. 2010 Aug 25;304(8):897–898. doi: 10.1001/jama.2010.1205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kottke T, Baechler C, Parker E. The Accuracy of Heart Disease Prevalence Estimated from Claims Data Compared to Electronic Health Record. Preventing Chronic Disease. doi: 10.5888/pcd9.120009. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]