Abstract

Targeted gene therapy is a promising approach for treating prostate cancer after the discovery of prostate cancer-specific promoters such as prostate-specific antigen, rat probasin, and human glandular kallikrein. However, these promoters are androgen-dependent, and after castration or androgen ablation therapy, they become much less active or sometimes inactive. Importantly, the disease will inevitably progress from androgen-dependent (ADPC) to castration-resistant prostate cancer (CRPC) at which treatments fail and high mortality ensues. Therefore, it is critical to develop a targeted gene therapy strategy that is effective in both ADPC and CRPC to eradicate recurrent prostate tumors. The human telomerase reverse transcriptase-VP16-Gal4-WPRE integrated systemic amplifier composite (T-VISA) vector we previously developed which targets transgene expression in ovarian and breast cancer is also active in prostate cancer. To further improve its effectiveness based on androgen response in ADPC progression, the ARR2 element (two copies of androgen response region from rat probasin promoter) was incorporated into T-VISA to produce AT-VISA. Under androgen analog (R1881) stimulation, the activity of AT-VISA was increased to a level greater than or comparable to the cytomegalovirus (CMV) promoter in ADPC and CRPC cells, respectively. Importantly, AT-VISA demonstrated little or no expression in normal cells. Systemic administration of AT-VISA-BikDD encapsulated in liposomes repressed prostate tumor growth and prolonged mouse survival in orthotopic animal models as well as in the transgenic adenocarcinoma mouse prostate model, indicating that AT-VISA-BikDD has therapeutic potential to treat ADPC and CRPC safely and effectively in preclinical setting.

Introduction

For patients with advanced, metastatic prostate cancer, which is initially androgen dependent, hormonal ablation is the primary choice of therapy (1). However, this modality eventually fails because prostate cancer frequently develops to an castration-resistant state within 2 years (1). Castration-resistant prostate cancer (CRPC), formerly known as androgen-independent prostate cancer, is an untreatable form of prostate cancer in which the normal dependence on androgen for growth and survival has bypassed (2) and is also a lethal form of prostate cancer that progresses and metastasizes. Thus, it is critical to develop an alternative strategy for treating not only androgen-dependent prostate cancer (ADPC) but also metastatic and recurrent CRPC.

Prostate-specific promoters, such as prostate-specific antigen (3-5), rat probasin (6-8), and human glandular kallikrein (9, 10), have been developed for prostate cancer gene therapy. The activities of these promoters are androgen-dependent with the possibility of targeting transgene expression to the AR+ tissues including normal prostate epithelial cells and AR+ prostate cancer cells. However, this strategy may not be useful for the treatment of CRPC because binding of androgen-androgen receptor (AR) complex is required for activation of these promoters, and the activities of these promoters are much weaker compared with the non-specific ubiquitous cytomegalovirus (CMV) promoter widely used in gene therapy.

The VISA (VP16-Gal4-WPRE integrated systemic amplifier) vector was developed and successfully shown to selectively amplify the transcriptional activity of promoters in multiple cancer types (11-15). More recently, the hTERT-promoter-based VISA (also referred to as T-VISA) vector that we developed for ovarian cancer also drives transgene expression in breast cancer (16) with activities higher than or comparable to the CMV promoter. Since the hTERT promoter activity is activated in more than 85% human cancers, including prostate cancer, but absent in normal somatic cells (17), we also tested the T-VISA vector for its activity in prostate cancer and found that T-VISA is active in both CRPC and ADPC. In most early-stage prostate cancers, the AR gene is amplified or overexpressed (18, 19). Therefore, the therapeutic index can be greatly improved if the activity of a targeted expression vector is stimulated by androgen. To further improve the therapeutic index in ADPC, we fused the ARR2 element (two copies of androgen response region from rat probasin promoter) derived from plasmid ARR2PB (20, 21) to the hTERT promoter in T-VISA to produce an AT-VISA composite. We then used AT-VISA expression vector to deliver the apoptotic gene BikDD (a mutant form of proapoptotic Bik) (22), which has been used in breast, pancreatic, liver, and lung cancer and shown to strongly induce apoptosis and inhibit cell proliferation (11-13, 15, 16). Systemic administration of AT-VISA-BikDD: liposome complexes repressed prostate tumor growth and prolonged mouse survival in orthotopic animal models of LNCaP-Luc and PC-3-Luc cells as well as in the transgenic adenocarcinoma mouse prostate (TRAMP) model. Thus, our study demonstrates an effective targeted gene therapy to treat both ADPC and CRPC.

Materials and Methods

Cell lines

Androgen-responsive human prostate adenocarcinoma cell line LNCaP, castration-resistant prostate cancer cell lines, PC-3 and DU145, and normal lung fibroblast WI-38 cell line were obtained from the American Type Culture Collection (ATCC, Manassas, VA). Normal prostate epithelial cells (PrEC) and normal human vascular endothelial cells (HUVEC) were also purchased from ATCC. AR-positive castration-resistant prostate cancer cell line LAPC-4 was kindly provided by Dr. Charles Sawyers (Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center, New York). Cell lines were validated by STR DNA fingerprinting using the AmpFlSTR Identifiler kit according to manufacturer instructions (Applied Biosystems). The STR profiles were compared to known ATCC fingerprints (ATCC.org), to the Cell Line Integrated Molecular Authentication database (CLIMA) version 0.1.200808 (Nucleic Acids Research 37:D925-D932 PMCID: PMC2686526) and to the MD Anderson fingerprint database. The STR profiles matched known DNA fingerprints or were unique. All cells were maintained according to the supplier’s instructions. Charcoal/dextran-treated FBS (Hyclone, Logan, UT) was substituted for general FBS in androgen-inducibility experiments.

Constructs

Plasmids pGL3-hTERT-Luc (T-Luc), pGL3-hTERT-Luc-WPRE (T-P-Luc), pGL3-hTERT-TSTA-Luc (T-T-Luc), pGL3-hTERT-TSTA-Luc-WPRE (T-VISA-Luc), pGL3-CMV-Luc (CMV-Luc), and pUK21-CMV-BikDD were constructed as previously described (15, 16). The ARR2 element derived from plasmid ARR2PB (20, 21) was fused to the hTERT promoter of hTERTp-TSTA-Luc and hTERTp-TSTA-Luc-WPRE, to produce plasmid pARR2-hTERTp-TSTA-Luc (AT-T-Luc) and pARR2-hTERTp-TSTA-Luc-WPRE (AT-VISA-Luc). pGL3-ARR2PB-Luc was described previously (20, 21). The AT-VISA fragment was released and inserted into the pUK21 to get pUK21-AT-VISA-BikDD.

Cell transfections

Transient transfections were performed as described previously (15, 16). In brief, cells were transiently cotransfected with 1 μg of the luciferase reporter plasmid DNA and 0.1 μg of pRL-TK in 12-well plates using liposome HLDC, an extruded DOTAP/cholesterol liposome and produced in our laboratory according to the previously published protocol (15, 16), to evaluate the promoter activities. To determine the in vitro killing effect, a panel of cell lines was transiently cotransfected with 2 μg of pUK21-CMV-BikDD, pUK21-AT-VISA-BikDD, or pUK21-AT-VISA plus 0.1 μg of pGL3-CMV-Luc. Synthetic androgen methyltrienolone (R1881, NEN/Dupont, CA) was added at indicated concentrations.

Stable cell lines expressing firefly luciferase

LNCaP and PC-3 cells were transfected with pEF1a-Luc-Neo and selected with G418 (Invitrogen). G418-resistant clones, designated as LNCaP-Luc and PC-3-Luc, were collected, identified, and maintained.

Orthotopic animal models of prostate cancer xenografts and systemic delivery of plasmid DNA

Athymic male BALB/c nu/nu mice (Charles River Laboratories, Wilmington, MA) 6-8 weeks of age were used as hosts for human xenografts. TRAMP (C57BL/6 background) mice and C57BL/6 mice were purchased from The Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, ME). All mice were maintained in a specific pathogen-free environment in compliance with The MD Anderson Cancer Center policy, and all animal procedures were conducted under approved protocol. Plasmid DNA:liposome complexes were prepared as described previously (15, 16).

To test specificity and activity of the promoters in vivo, we established orthotopic models of AR+ (LNCaP) and AR- (PC-3) prostate cancer. Cells in logarithmic-phase growth were trypsinized and washed with PBS twice. Suspensions of LNCaP or PC-3 cells were inoculated into the ventral parts of the prostate as previously described (23). Twenty-one days after inoculation, the mice were injected with 100 μl of DNA:liposome complexes containing 50 μg of DNA through the tail vein using a 29-gauge needle. Mice were imaged every other day by an in vivo imaging system (IVIS, Xenogen, Alameda, CA).

To test antitumor effect of BikDD driven by AT-VISA and CMV promoter in vivo, we established orthotopic models of LNCaP-Luc and PC-3-Luc cells. Suspensions of LNCaP-Luc cells or PC-3-Luc cells were inoculated into the prostate as described above. Twenty-one days after inoculation, mice were imaged by IVIS and randomized into groups. DNA:liposome (100 μl) complexes containing 15 μg of pUK21-AT-VISA-BikDD, pUK21-CMV-BikDD, or pUK21 without BikDD (control) were delivered by intravenous injection twice a week for three consecutive weeks. The growth and metastasis of tumors were monitored by IVIS.

The TRAMP heterozygotic positive mice were bred with wild-type male C57BL/6 mice at the institution and the transgenic progeny was genotyped by PCR analysis of tail DNA isolated from 3-week-old litters (24). Male TRAMP mice at 12 weeks of age were treated by intravenous injection with indicated DNA:liposome complexes as described above once a week for 10 weeks. At 30 weeks of age, randomized mice from each group were sacrificed and necropsies were performed. The urogential system, draining lymph nodes, and major organs were removed and weighed. Tissues were dissected for histological analysis.

Luciferase assays

Forty-eight hours after transient transfection, cells were lysed and assayed for luciferase activity using the Dual-Luciferase® Reporter Assay System (Promega, Madison, WI) following the manufacturer protocol with a TD 20/20 luminometer (Turner Designs, Sunnyvale, CA). The dual-luciferase ratio was defined as the firefly luciferase activity of the tested plasmids over the Renilla luciferase activity of pRL-TK and expressed as the mean of triplicate transfections (15, 16), which were repeated at least four times. Percentage represents ratio of tested plasmid over CMV.

To determine the tissue distribution of luciferase expression, animals were euthanized and dissected. Tissue specimens from tumor and other organs including pancreas, lung, heart, liver, spleen, kidney, brain, intestine, muscle, and ovary, were harvested and homogenized (15, 16). Specimens were centrifuged at 8,000 rpm for 5 min and placed temporarily on ice. The luciferase activity of the cell lysates was measured with a Lumat LB9507 luminometer (Berthod, Bad Wildbad, Germany), and the protein concentration was determined using the detergent compatible (DC) protein assay system (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA) with MRX microplate reader (Dynex technologies, Chantilly, VA). The luminescence results were reported as relative light units (RLU) per milligram of protein.

Quantification of bioluminescence imaging

Mice were anesthetized with a mixture of oxygen and isoflurane and intraperitoneally injected with 100 μl of D-luciferin (30 mg/ml in PBS; Xenogen, Alemeda, CA). Ten minutes after injection, mice were imaged with IVIS (25). Imaging parameters were maintained for comparative analysis. The images were analyzed using the Living Imaging software version 2.11 (Xenogen). A region of interest (ROI) was manually selected over relevant regions of signal intensity. The area of the ROI was kept constant and the intensity was recorded as the maximum number of photon counts within an ROI (25). In vivo cell imaging was performed 5 min after addition of D-luciferin at a final concentration of 5 ng/ml.

Western blotting

To identify BikDD expression and PARP cleavage after transduction, LNCap, PC-3, and WI-38 cells transiently transfected with indicated plasmids and then stimulated with R1881 at 1 nM in medium containing charcoal/dextran-treated FBS. Protein lysates were prepared using RIPA cell lysis buffer 18 h after transfection. The membranes were blocked with 5% nonfat dry milk in PBS containing 0.05% Tween 20 and incubated with primary goat anti-Bik polyclonal antibody (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA), primary rabbit cleaved PARP antibody (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA), or monoclonal antibody anti-actin as internal control (Santa Cruz Biotechnology), followed by polyclonal horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-conjugated goat or rabbit anti-mouse secondary antibody (Bio-RAD). Bands were detected with SuperSignal chemiluminescent substrate (Pierce, Rockford, IL).

Cell growth and viability assay

Cells were plated in 96-well plates at 5×103 per well in a final volume of 100 μL and transfected with 0.25 μg control, CMV-BikDD, T-VISA-BikDD, or AT-VISA-BikDD and then stimulated with or without R1881 (1 nM) in medium containing charcoal/dextran-treated FBS. The cells were then cultured for 48 h in a humidified incubator at 37 °C with 5% CO2. After incubation, MTT (3-(4, 5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2-5 diphenyl tetrazolium bromide) was added to the cells. After a 4-h incubation, the supernatant was removed, and the insoluble formazan crystals were dissolved in 200 μL of dimethyl sulfoxide. The absorbance was determined at 570 nm by SpectraMax M5 Microplate Reader (Molecular Devices, USA). The results were expressed as percentage inhibition relative to the control cells (set as 100 %).

Histological and immunohistochemical examination

The dissected prostatic tumors and other tissues indicated above were fixed overnight in 10% formaldehyde and embedded in paraffin wax. Sections of 5-μm thickness were cut and stained with hematoxylin and eosin. Immunostaining for firefly luciferase was performed as previously described (26) by using goat anti-firefly luciferase antibody (Abcam, Hartford, CT) and HRP-conjugated avidin biotin complex (Vectastin Elites ABC Kit, Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA). Peroxidase activity was determined by using AEC chromogen (Vector Laboratories) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Finally, sections were washed in distilled water to terminate the reaction, counterstained with hematoxylin, dehydrated, and mounted.

In vivo apoptosis assays

To identify cells undergoing apoptosis after BikDD expression, we performed in situ terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase-mediated dUTP nick end labeling (TUNEL) assay (Promega) and PARP cleavage Western blot analysis. Tumor or tissue samples were fixed and sectioned as described above. The percentage of apoptotic cells was analyzed by randomly selecting four fields.

Analysis of acute toxicity

Male C57BL/6 (6-8-week old) mice were analyzed for acute toxicities induced by systemic administration. DNA:liposome complexes (100 μl) were injected through tail vein at single doses of 50 μg or 100 μg plasmid DNA (~2.5 mg/kg or 5 mg/kg body weight, respectively). After 48 h, four mice per group were anesthetized and blood was collected by retro-orbital bleeding using a heparinized microcapillary tube. Serum aspartate aminotransferase (AST) and alanine aminotransferase (ALT) levels were measured by automatic analyzer (Roche Cobas Mira Plus, Roche, Mannheim, Germany).

Statistical analyses

An analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used to compare the difference among the groups. Survivals were analyzed by log-rank test (Mantel-Cox test) using SSPS software. The significance level was set at p < 0.05.

Results

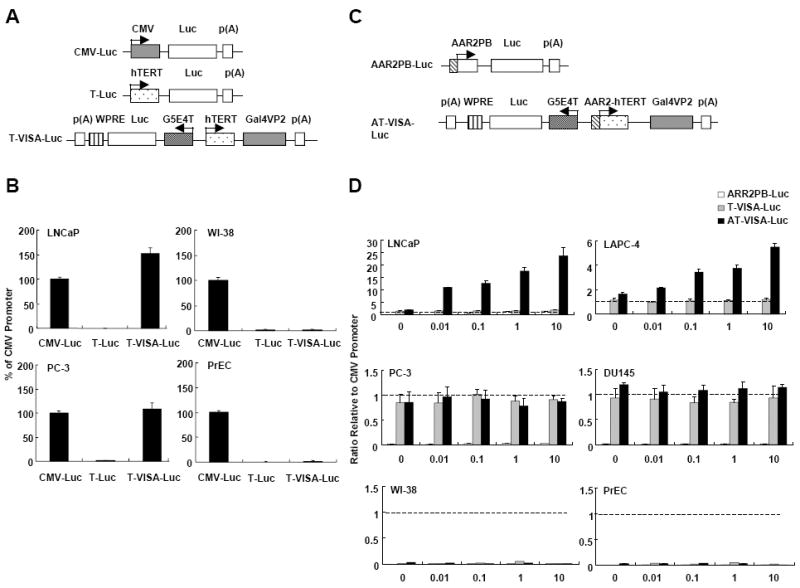

T-VISA is robust and specific in prostate cancer cells

Previously, we engineered the T-VISA expression vector (14) to increase the transgene expression under the hTERT promoter (Fig. 1A), which had much lower activity than the commonly used strong CMV promoter. We measured the activity the T-VISA-Luc and control T-Luc vector in AR+ (LNCaP) and AR- (PC-3) prostate cancer cells as well as in human normal lung fibroblast cells (WI-38) and normal prostate epithelial cells (PrEC). As shown in Figure 1B, the activity of T-Luc in both LNCaP and PC-3 cells was less than 1% compared with the CMV promoter. In contrast, the activity of T-VISA-Luc was increased to a level comparable to CMV in PC-3 cells and even higher in LNCaP cells. Importantly, T-VISA remained inactive in both WI-38 and PrEC compared with CMV-Luc (Fig. 1B), indicating that this vector targeted prostate cancer cells.

Figure 1. T-VISA has robust activities in prostate cancer, and ARR2 element in T-VISA enhances response to androgen stimulation.

(A) Schematic diagram of reporter constructs. CMV-Luc (pGL3-CMV-Luc); T-Luc, (pGL3-hTERT-Luc), and T-VISA-Luc (pGL3-hTERT-TSTA-Luc-WPRE). (B) Prostate cancer cells (LNCaP and PC-3), normal lung fibroblast (WI-38) and normal prostate epithelial cells (PrEC) were transiently co-transfected with the indicated plasmid DNA (1 μg) plus the internal control pRL-TK (0.1 μg). Forty-eight hours later, dual luciferase ratio was measured and then normalized to CMV. (C) Schematic diagram of reporter constructs with androgen responsive element ARR2 placed upstream of hTERT in T-VISA. ARR2PB-driven Luc was included as a control. (D) AR+ prostate cancer (LNCaP and LAPC-4), AR- prostate cancer (PC-3 and DU145), and normal (PrEC, WI-38) cells were transiently co-transfected with the indicated plasmid DNA (1 μg) with the internal control pRL-TK (0.1 μg). Forty-eight hours after R1881 treatment at increasing concentrations in medium containing charcoal/dextran-treated FBS, dual luciferase ratio was measured and normalized to CMV (dashed line). The data represent the mean of four independent experiments. Error bars, SD.

ARR2-hTERT promoter is stimulated by androgen

To enhance the promoter’s response to androgen stimulation, we inserted the ARR2 element upstream of the hTERT promoter to generate AT-VISA-Luc (Fig. 1C). ARR2PB-Luc was used as a control and CMV-Luc for comparison. ARR2PB promoter alone was relatively inactive in all four prostate cancer cell lines tested compared with CMV (Fig. 1D). As expected, the activity of AT-VISA was increased in an androgen-dependent manner in AR+ CRPC LAPC-4 and AR+ ADPC LNCaP cells to 5.5- and 23.8-fold higher than the CMV promoter at concentration of 10 nM R1881. In contrast, the activity of AT-VISA was neither stimulated nor inhibited by R1881 in AR- CRPC PC-3 and DU145 cells (Fig. 1D). In all four cell lines tested, the activity of AT-VISA was comparable to the CMV promoter in AR- CRPC (PC-3 and DU145) cells and even much stronger in AR+ ADPC (LNCaP) and AR+ CRPC (LAPC-4) cells but inactive in normal cell lines such as WI-38 and PrEC. These results indicate that AT-VISA vector can be used for both ADPC and CRPC and enhanced by androgen receptor ligand stimulation for ADPC.

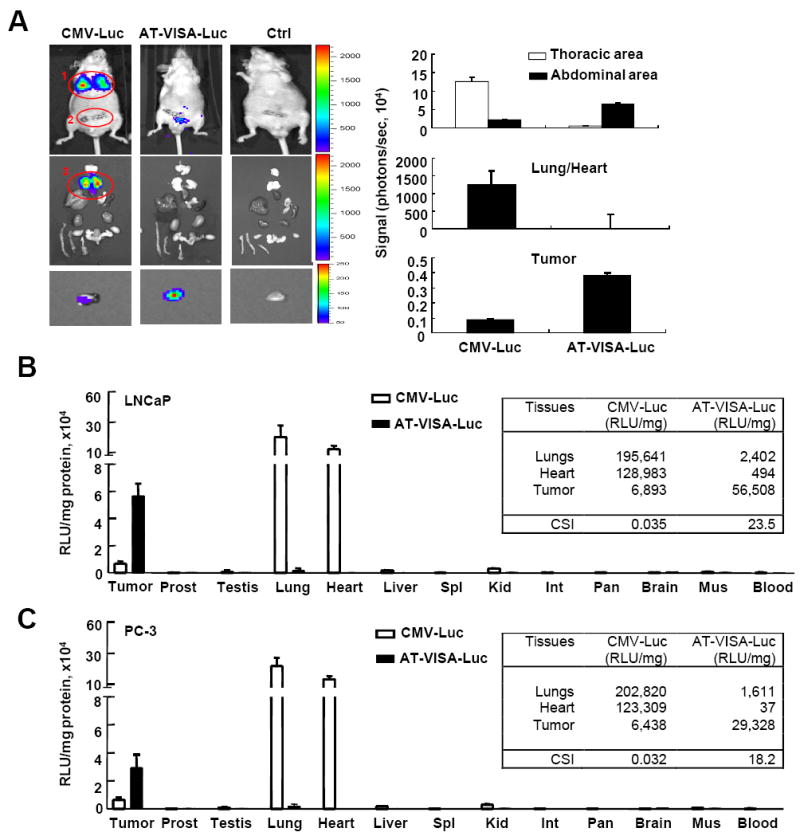

AT-VISA is robust and prostate cancer-specific in orthotopic animal models

To further determine whether the activity and specificity of AT-VISA can be maintained in vivo, we established male BABL/c nu/nu mouse models of orthotopic LNCaP and PC-3 xenografts. Normal male BABL/c nu/nu mice (control) and those bearing LNCaP or PC-3 tumors were injected intravenously with 50 μg of AT-VISA-Luc, CMV-Luc, or control complexed with liposomes once a day for three consecutive days. Mice bearing LNCaP tumors were imaged in vivo for 2 min every day and sacrificed 24 h after the last injection. Bioluminescence signals were detected mainly in the thoracic area (circle #1) corresponding to the lungs and heart of mice treated with CMV-Luc, as they are the first target organs after tailvein injection (representative images shown; Fig. 2A). The signal densities in the thoracic area were significantly higher in the CMV-Luc- than AT-VISA-Luc-treated mice (p < 0.003; Fig. 2A, top right bar graph) whereas those in the lower abdominal area (circle #2; Fig. 2A) were significantly higher in the AT-VISA-Luc- than in CMV-Luc-treated mice (p < 0.005; Fig.2A, top right bar graph).

Figure 2. AT-VISA drives robust transgene expression in ADPC and CRPC xenografts.

(A) Male nude mice bearing orthotopic LNCaP tumors were intravenously injected with 50 μg of DNA (CMV-Luc or AT-VISA-Luc):liposome complexes. Mice were anesthetized, and imaged for 2 min with an IVIS™ imaging system after intraperitoneal injection of D-luciferin. Images were taken 24 h after the last DNA:liposome complex injection. A representative mouse from each CMV-Luc, AT-VISA-Luc and control (Ctrl) group is shown (top). Mice from each group were then euthanized and microdissected. Isolated organs were imaged on luminescent-free paper. The tumors in the prostates were dissected and imaged ex vivo for 10 min, and one representative tumor from each group is shown (bottom panels). Quantitation of the signal density in the thoracic and abdominal area, the lungs/heart, and the tumor is shown on the right. (B) Tissue specimens from tumors (LNCaP) and organs as indicated were dissected and measured for luciferase activity with a luminometer. (C) Similar to the LNCaP model, male nude mice bearing orthotopic PC-3 tumors were intravenously injected with 50 μg of DNA in DNA:liposome complexes. Tissue specimens from tumors and organs as indicated were dissected and measured for luciferase activity with a luminometer. Data are presented as mean ±SD; n = 3. CSI, cancer-specific index.

To further determine the source of the signals, we sacrificed the mice immediately after imaging and dissected their major organs for ex vivo imaging. We verified that the lungs of mice treated with CMV-Luc emitted the strongest signals (circle #3, Fig. 2A) while signals from the lungs/heart of mice treated with AT-VISA-Luc were undetectable (Fig.2A, left, center panel and right center bar graph). To increase signal strength, the dissected tumors were re-imaged for additional 10 min (Fig. 2A, left, bottom panels). Tumors from mice treated with AT-VISA-Luc had stronger signals than those from mice treated with CMV-Luc (p < 0.002; Fig. 2A, right bottom bar graph).

Tissue distribution indicated that the luciferase activities were significantly higher in the lungs and heart than those in the tumor from mice treated with CMV-Luc (Fig. 2B). In contrast, luciferase activities were lower in the lungs and heart than in the tumor from mice treated with AT-VISA-Luc. The cancer-specific index (CSI; luciferase activity of the tumor over the lungs) for AT-VISA-Luc and CMV-Luc was determined to be 23.5 and 0.035, respectively (Fig. 2B). Although PC-3 cells are AR-, the signals from PC-3 tumor from mice treated with AT-VISA-Luc were still stronger compared to that from mice treated with CMV-Luc with a CSI of 18.2 and 0.031 for AT-VISA-Luc and CMV-Luc, respectively (Fig. 2C). To examine the tissue distribution in normal controls, the activities of CMV-Luc and AT-VISA-Luc were also evaluated in male BABL/c nu/nu mice not bearing tumors. Data showed that luciferase activities were significantly higher in the lungs and heart than those in normal prostate, seminal vesicles and lacrimal glands in mice treated with CMV-Luc (Supplementary Fig. S1). In contrast, luciferase activities were much lower in lungs and heart as well as in normal prostate, seminal vesicles, and lacrimal glands in mice treated with AT-VISA-Luc. Together, our data indicate that AT-VISA is able to direct gene expression in both AR+ and AR- prostate tumors, at least as efficiently as the CMV promoter in the AR- but more efficiently in AR+ prostate tumors.

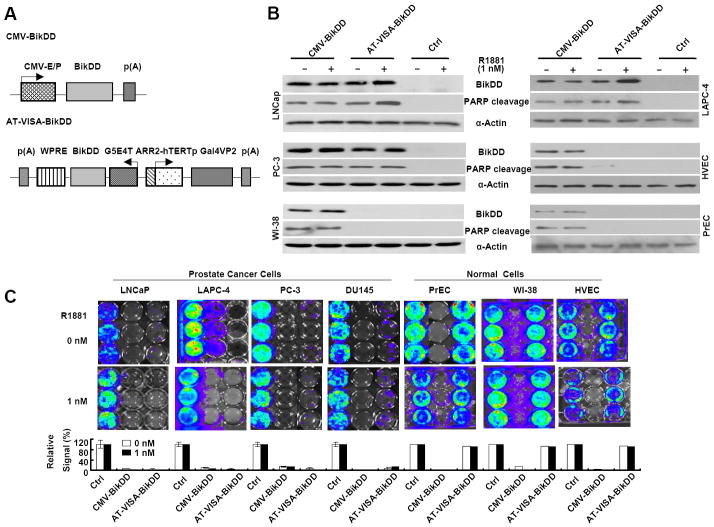

AT-VISA-BikDD effectively kills ADPC and CRPC cells

To develop a gene therapy strategy for prostate cancer using the prostate cancer specific AT-VISA expression platform, we replaced luciferase with BikDD and changed the vector backbone to pUK21 (Fig. 3A). Western blotting showed that AT-VISA expressed BikDD and induced PARP cleavage in prostate cancer cell lines but not in normal cells (Fig. 3B). The levels of BikDD expression by AT-VISA in LNCaP and PC-3 cells were comparable to CMV-BikDD and were increased in LNCaP and LAPC-4 cells in response to androgen stimulation (1 nM R1881; Fig. 3B). Both of CMV-BikDD and AT-VISA-BikDD demonstrated effective in vitro killing of AR+ ADPC LNCaP, AR+ CRPC LAPC-4, and CRPC (PC-3 and DU145) cells (Fig. 3C). Consistent with the activity of the AT-VISA promoter, the killing effect of AT-VISA-BikDD in LNCaP and LAPC-4 cells was further improved with androgen analog treatment. Importantly, while CMV-BikDD also killed normal prostate cells, AT-VISA-BikDD did not (Fig. 3C). Similar results were observed in an MTT assay to evaluate the killing effects of AT-VISA-BikDD, T-VISA-BikDD, CMV-BikDD, and control on prostate cancer cells and normal prostate cells. Compared with T-VISA-BikDD, AT-BikDD exhibited much stronger killing effects on ADPC but not on CRPC cells (Supplementary Fig. S2). Thus, these data demonstrate that AT-VISA-BikDD effectively kills both ADPC and CRPC cells without affecting normal cells and that R1881 can enhance the killing effect in ADPC.

Figure 3. AT-VISA-BikDD effectively kills ADPC and CRPC cells in vitro.

(A) Schematic diagram of BikDD constructs CMV-BikDD (pUK21-CMV-BikDD), AT-VISA-BikDD (pUK21-AT-VISA-BikDD) and control (ctrl; pUK21-AT-VISA). (B) LNCaP, PC-3, and WI-38 cells transiently transfected with indicated plasmids and then stimulated with R1881 at 1 nM in medium containing charcoal/dextran-treated FBS. After transfection, cell lysates were subjected to Western blotting to detect the expression of BikDD (left). Quantitation is shown on the right. (C) In vitro killing effect of BikDD. A panel of AR+ prostate cancer (LNCaP and LAPC-4), AR- prostate cancer (PC-3 and DU145) and normal (PrEC, WI-38 and HUVEC) cells were transiently co-transfected with 2 μg of CMV-BikDD, AT-VISA-BikDD or control, plus 100 ng of CMV-Luc as indicated and then stimulated with R1881 at 1 nM in medium containing charcoal/dextran-treated FBS. Forty-eight hours post transfection, cells were imaged for 30 seconds by the IVIS™ Imaging System to determine the luciferase reporter activity 5 min following the addition of 5 ng/ml of D-luciferin. Top, representative images. Bottom, quantitation of the signals relative to negative control (set as 100%). The data represent the mean of three independent experiments. Error bars, SD.

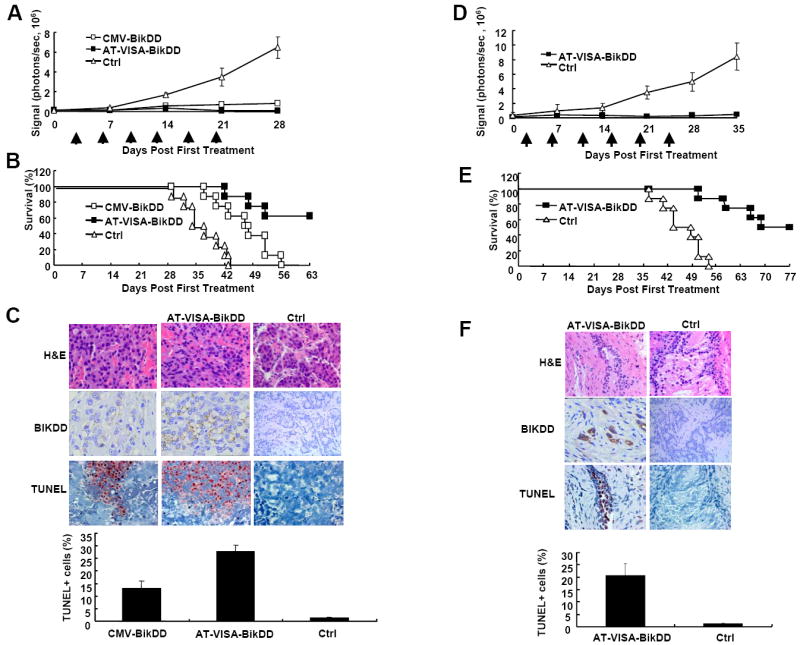

AT-VISA-BikDD inhibits tumor growth and prolongs mouse survival in an orthotopic model of ADPC xenografts

A more rigorous test for the effect of BikDD in a gene therapy setting is an orthotopic prostate tumor model by intravenous injection. In order to monitor the growth and metastasis (if any) of prostate cancer in a real-time manner, we first established prostate cancer cell lines that stably express firefly luciferase (LNCaP-Luc and PC-3-Luc). This step is critical for real-time monitoring of the antitumor effect of AT-VISA-BikDD on prostate cancer in orthotopic mouse models. To investigate whether AT-VISA-BikDD has a potent therapeutic effect in vivo, we treated orthotopic LNCAP-Luc tumor-bearing mice through systemic delivery of AT-VISABikDD encapsulated in liposomes 21 days after cell implantation and monitored tumor growth by live imaging (IVIS). In contrast to the control mice, in which the strength of the luciferase signals increased over time, signals from mice treated with CMV-BikDD or AT-VISA-BikDD significantly decreased 14 days after first treatment (p < 0.01 and p < 0.009, respectively, vs. control; Supplementary Fig. S3 and Fig. 4A). In addition, AT-VISA-BikDD decreased the signals from mice more effectively than CMV-BikDD (p < 0.05 on day 21 and p < 0.02 on day 28), indicating that AT-VISA-BikDD inhibited the tumor growth more potently than CMV-BikDD. While CMV-BikDD significantly prolonged the median survival time of mice compared to the control (40 ± 3 days vs. 30 ± 2 days, p < 0.0003), AT-VISA-BikDD prolonged the longest survival (p < 0.01; Fig. 4B). The signals in five of eight mice in the AT-VISA-BikDD group were barely detectable, indicating that their tumors were almost eradicated. To further validate the effect of the treatments, mice were sacrificed two days after two administrations and their tumors were sectioned for apoptosis detection by TUNEL assay analysis (Fig. 4C; representative images shown on top). Consistent with tumor growth and mouse survival, both AT-VISA-BikDD and CMV-BikDD induced tumor cell apoptosis with AT-VISA-BikDD having more apoptosis-inducing potential than CMV-BikDD (p < 0.002; Fig. 4C, bottom).

Figure 4. AT-VISA-BikDD inhibits tumor growth and prolongs mouse survival in LnCAP and PC-3 orthotopic mouse models.

Male nude mice bearing orthotopic tumors were administered 15 μg of DNA in DNA:liposome complexes via tail vein injection twice per week for 3 weeks. (A) LnCaP-Luc tumor growth in mice was measured weekly by live imaging before and after treatment. All photon signals were quantified using the IVIS™ imaging software (n = 8). (B) Kaplan-Meier survival analysis from (A). (C) Male nude mice bearing LNCaP-Luc tumors were administered DNA:liposome complexes as described above. Two day later after last injection, mice were sacrificed and tumors excised, fixed, and sectioned for apoptosis detection by TUNEL assay analysis and photomicrography (left, x200). The percentage of apoptotic cells (TUNEL+) from ten fields of the indicated tissues is shown below. (D) PC-3-Luc tumor growth in mice was measured weekly by live imaging before and after treatment. All photon signals were quantified using the IVIS™ imaging software (n = 8). (E) Kaplan-Meier survival analysis from (D). (F) Male nude mice bearing PC-3-Luc tumors were administered DNA:liposome complexes as described above. Two day later after last injection, mice were sacrificed and tumors excised, fixed, and sectioned for apoptosis detection by TUNEL assay analysis and photomicrography (left, x200). The percentage of apoptotic cells (TUNEL+) from ten fields of the indicated tissues is shown below.

AT-VISA-BikDD inhibits tumor growth and prolongs mouse survival in an orthotopic model of CRPC xenografts

To further evaluate whether AT-VISA-BikDD is also effective treating CRPC in vivo, male nude mice bearing orthotopic PC-3-Luc prostate tumors were systemically treated as described above for the ADPC orthotopic model. As shown in Figure 4D, AT-VISA-BikDD significantly decreased the luciferase signals from the treated mice compared to the control mice just after the last treatment (on day 21; p < 0.0001). Similar to the ADPC model, AT-VISA-BikDD also significantly prolonged the median survival time of mice compared to the control (p < 0.004; Fig. 4E). Furthermore, the signals in four of eight mice in the AT-VISA-BikDD group were almost undetectable, indicating that their tumors were almost eliminated. Three mice per group were sacrificed two days after two administrations, and their tumors were sectioned for apoptosis detection by TUNEL assay analysis (Fig. 4F; representative images shown on top). Similar to the results from ADPC model, we also demonstrated that AT-VISA-BikDD induced substantial apoptosis of PC-3 tumors as compared to the control (p < 0.007; Fig. 4F, bottom).

As a control, the expression of BikDD in prostate tissues was also examined by hematoxylin and eosin and immunohistochemical staining in normal male nude mice treated with CMV-BikDD, AT-VISA-BikDD or control. BikDD expression was found in the prostate tissue of mice treated with CMV-BikDD but not in the prostate tissues of those treated with AT-VISA-BikDD or control (Supplementary Fig. S4). Collectively, these results indicate that systemic delivery of AT-VISA-BikDD:liposome complexes inhibits tumor growth and prolongs mouse survival in both ADPC and CRPC xenograft models.

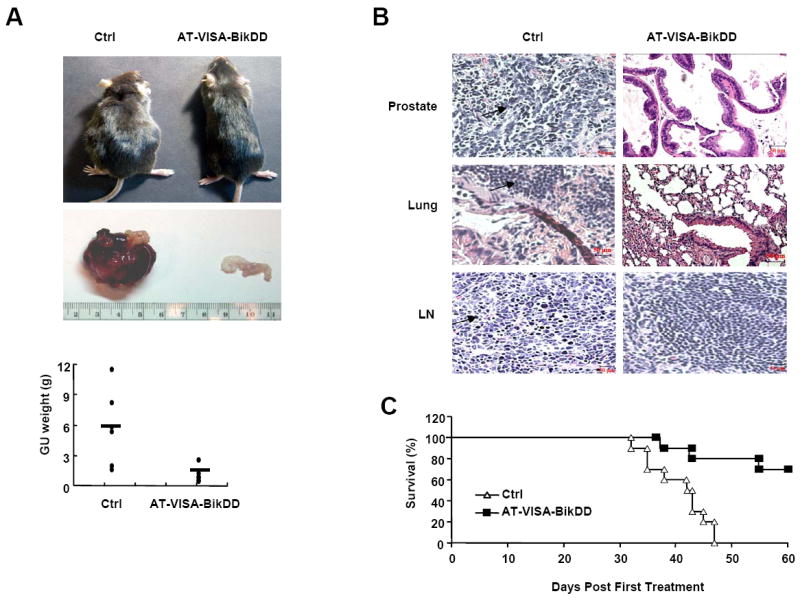

AT-VISA-BikDD effectively kills prostate cancer in TRAMP model

The autochthonous TRAMP model has a number of distinct advantages over xenograft model. The tumor progressive stage and tissue histology resemble the human prostate cancer. We also tested the therapeutic effect of AT-VISA-BikDD in this model. Before the start of therapy, we examined what percentage of mice at 12 weeks had prostate cancer. Ten TRAMP mice were randomly selected from all and sacrificed to determine the stage of cancer progression in their prostates. After dissection and pathologic confirmation, we found that 3 (30%) mice developed prostatic intraepithelial neoplasia and 7 (70%) developed well-differentiated prostate cancer. These findings were consistent with previous studies (24, 27, 28) in which the percentage of prostatic intraepithelial neoplasia and well-differentiated prostate cancer in TRAMP mice was reported to be 33% and 67% respectively. Mice were randomized into two groups and treated by intravenous injection with DNA:liposome (100 μl) complexes containing 15 μg of AT-VISA-BikDD (pUK21-AT-VISA-BikDD) or control (pUK21-AT-VISA without BikDD) once a week for 10 weeks. At 30 weeks of age, mice treated with AT-VISA-BIKDD overall appeared healthier than the control mice (Fig. 5A, top) compared to those untreated. We then sacrificed mice from each group and found that tumor growth based on the genitourinary (GU) weight was significantly inhibited by AT-VISA-BikDD compared with the control (Fig. 5A, middle and bottom). To further determine status of tumor and metastasis, organs such the prostates, lungs, and lymph nodes were dissected, paraformaldehyde-fixed, paraffin-embedded, and processed for pathological analysis. The sections were stained with hematoxylin and eosin. In AT-VISA-BikDD- treated mice, we observed only few tumor cells in the prostates with normal morphological characteristic and none in the lungs or the lymph nodes. In contrast, in control mice treated with pUK21-AT-VISA, tumors were solid and the normal morphological characteristics of the prostates were dismissed. The lungs and lymph nodes were also extensively infiltrated with tumor cells with morphological changes (black arrows, Fig. 5B). Consistently with the results from the orthotopic models described above, AT-VISA-BikDD also significantly prolonged mouse survival compared with the control (p < 0.004; Fig. 5C). Together, these results further validate the tumor inhibitory effect of AT-VISA-BikDD in a transgenic mouse model of prostate cancer.

Figure 5. AT-VISA-BikDD inhibits tumor growth and prolongs mouse survival in TRAMP model.

Male TRAMP mice were treated with AT-VISA-BikDD or AT-VISA (Ctrl) in DNA:liposome complexes via tail vein injection once a week for 10 weeks. (A) Top, representative image of treated mice at 30 weeks. Middle, representative set of the genitourinary (GU) system from the mice treated with AT-VISA-BikDD and control. Bottom, the weight of the urogential system from the mice treated with AT-VISA-BikDD and control (6 mice per group; p < 0.01). (B) Histological analysis of the prostate, lungs, and draining lymph nodes (LN). The arrows indicate prostate cancer cells or islands in the prostate, lungs, and lymph nodes. (C) Kaplan-Meier survival analysis of mice treated with AT-VISA-BikDD and control (10 mice per group; p < 0.001).

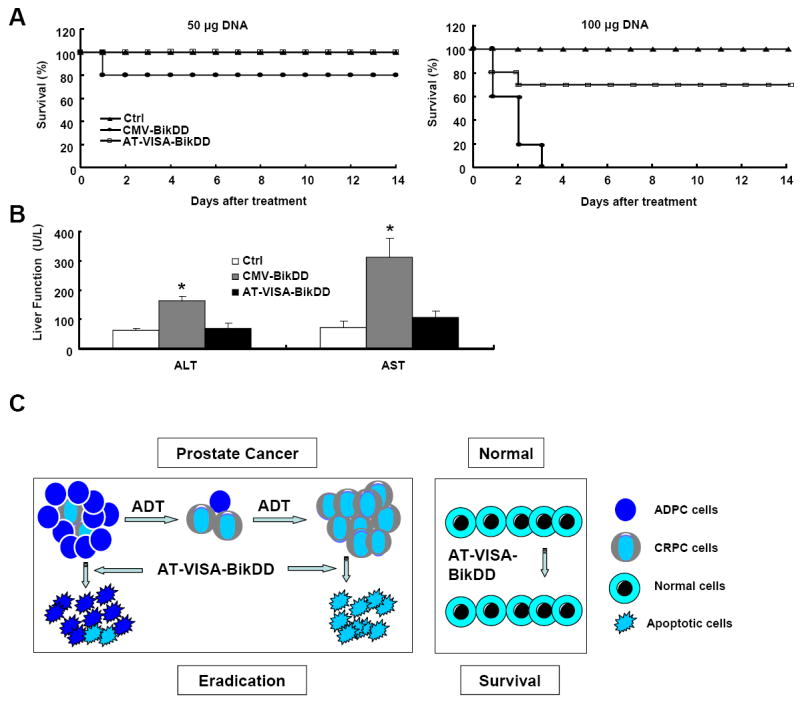

Systemic administration of AT-VISA-BikDD induces much less acute toxicities than CMV-BikDD in C57BL/6 mice

To determine whether AT-VISA-BikDD is safer than CMV-BikDD in preclinical studies and has the potential to be translated to clinical trials, systemic toxicities were evaluated in female C57BL/6 mice. Mice were administered 100 μl of DNA:liposome complexes via tail vein injection at single doses of 50 or 100 μg plasmid DNA. At a single dose of 50 μg, 20% of mice treated with CMV-BikDD died on the following day; however, none of the mice treated with AT-VISA-BikDD died within 14 days after injection (Fig. 6A, left). The survival rate of mice treated with the higher dose (100 μg) of AT-VISA-BikDD was significantly longer compared with mice treated with a same dose of CMV-BikDD (all mice treated with CMV-BikDD died after 3 days; p < 0.001; Fig. 6A, right). There were no accidental deaths as all deaths were caused by toxicity or disease progression. To assess the effects of the DNA:liposome complexes on liver function, blood samples from mice treated with 50 μg DNA were collected to determine the serum levels of liver AST and ALT. Mice treated with CMV-BikDD had significantly elevated AST and ALT levels but not those treated with AT-VISA-BikDD, which showed similar levels to the control mice (Fig. 6B). These results indicate that AT-VISA-BikDD treatment is much safer and exerts only limited systemic toxicity.

Fig. 6. AT-VISA-BikDD induces less systemic acute toxicities than CMV-BikDD.

The female C57/BL6 mice were administered the indicated plasmid DNA in DNA:liposome complexes via the tail vein. (A) Kaplan-Meier survival analysis of mice treated with 50 μg (left) or 100 μg (right) control, CMV-BikDD or AT-VISA-BikDD DNA complexed with liposomes (n = 10). (B) Serum AST and ALT levels of mice from 50 μg DNA two days after treatment. Values represent the means of 4 animals per group. Error bars, SD; *p = 0.001. (C) A model of the AT-VISA-BikDD system. Prostate cancer is comprised of androgen dependent (ADPC) and castration-resistant (CRPC) prostate cancer cells. Androgen-deprived therapy (ADT) could treat ADPC but not CRPC whereas AT-VISA-BikDD system has the potential to eliminate not only ADPC but also CRPC without affecting normal cells.

Discussion

A safe and effective gene therapeutic strategy for cancer depends greatly on two key determinants: tumor specificity and efficient transgene expression. With the goal of developing a prostate cancer-specific vector with robust activity, we selected the hTERT promoter. Telomerase activation is observed in approximately 90% of human cancers, irrespective of tumor type, while most normal tissues contain inactivated telomerase (26), and its promoter has been used in many types of cancer, including ovarian and breast (14, 16). Our data showed that the minimal promoter fragment of hTERT is active in both ADPC and CRPC cells but has much lower activity than CMV promoter. To overcome the lack of strong activities in tissue specific promoters, we used VISA expression system that has been successfully applied to other cancer types (11, 13-16).

In most cases of recurrent or metastatic prostate cancer through ADPC to CRPC progression, the AR gene is amplified and/or overexpressed and binds to androgen (or androgen analog) for subsequent binding to the androgen response element (ARE), resulting in transcriptional activation. In this regard, the therapeutic index should be greatly improved if the promoter contains ARE for androgen (or androgen analog)/AR complex binding to stimulate therapeutic gene expression. The AT-VISA described here contains an ARE (AAR2) and was shown to increase the activity of T-VISA vector in an androgen-dependent manner under R1881 stimulation. Interestingly, AT-VISA is also active in CRPC, suggesting that this newly designed vector could broadly target both ADPC and CRPC with the advantage that the therapeutic index can be amplified in ADPC by ligand stimulation.

We utilized several cell lines (AR+ ADPC, AR+ CRPC, and AR- CRPC) as well as animal models, including the EZC-prostate, orthotopic xenograft, and TRAMP model to study the AT-VISA vector. The EZC-prostate model in which prostate cancer cell lines (LNCaP-Luc and PC-3-Luc) stably expressing firefly luciferase enzyme facilitated live imaging of established orthotopic prostate cancer xenografts (25, 29) and enabled real-time monitoring of prostate tumor growth and metastases without having to sacrifice the animals. An orthotopic model by injecting tumor cells into the prostate better mimics the prostate cancer in clinics than a subcutaneous model. The use of autochthonous TRAMP model has a number of distinct advantages over existing xenograft models (28, 30-32): TRAMP model can spontaneously develop prostate tumor close to the human disease and holds intact immune system instead of nude mice in which the T-cell immune system is compromised. In addition, this model’s histopathology and molecular changes of prostate adenocarcinoma associated with progression have been well characterized. It is anticipated that the establishment of the TRAMP model will facilitate many new avenues of research towards better prevention, diagnosis and treatment of prostate cancer. Together, all three models, EZC-prostate, orthotopic, and TRAMP provided reliable and reproducible results to support further clinical development of the AT-VISA vector.

In the early stage, prostate cancer cells are mostly AR+ ADPC and sensitive to androgen-deprived therapy (ADT), and thus hormonal ablation is the primary choice of treatment. However, after a period of ADT, prostate cancer progresses to CRPC that is advanced, resistant to ADT, metastatic, and lethal (2). The progression from ADPC to CRPC was demonstrated by Isaacs and Coffey (33) by a selection model in which the preexisting castration-resistant tumor cells in a heterogeneous population of cells containing both androgen-dependent and castration-resistant tumor cells continue to grow exponentially following castration and death of androgen-dependent cells. The AT-VISA-BikDD system has the potential to eliminate not only androgen-dependent but also metastatic and recurrent hormonal refractory prostate cancer without affecting normal cells due to its selectivity (Fig. 6C).

Early gene therapy for prostate cancer based on non-specific promoters, such as cytomegalovirus (CMV) and Rous sarcoma virus (RSV) promoters, usually cause severe toxicity to normal tissues. Therefore, to minimize systemic toxicity when expressing therapeutic gene, prostate-specific promoters have been developed for prostate cancer-targeted therapies, including those of prostate-specific antigen (PSA), probasin (PB), mouse mammary tumor virus (MMTV LTR), prostate-specific membrane antigen (PSMA), human glandular kallikrein-2 (hK2), and prostatic steroid-binding protein C3 (34). Although they are selective, most are androgen-dependent. Compare with these, AT-VISA exhibits more selectivity, robust efficiency, and less systemic toxicity.

In summary, we report that AT-VISA, an expression vector active in both ADPC and CRPC, induces stronger transgene expression than the CMV promoter-based expression vector in vitro and in vivo. Expression of proapoptotic BikDD by AT-VISA after systemic liposome-mediated delivery significantly reduced prostate tumor growth and prolonged survival in multiple orthotopic xenograft models of prostate tumors as well as in the TRAMP model with little or no toxicity. Overall, our study demonstrates the feasibility of AT-VISA-BikDD:liposome complex as a novel, safe and highly effective gene therapy strategy for both ADPC and CRPC, holding a great promise for prostate cancer patients suffering from recurrence and metastasis.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Financial Support

MD Anderson Cancer Center Support Grant (National Institutes of Health; CA16672; to M.-C. Hung); Center for Biological Pathways (to M.-C. Hung); The University of Texas MD Anderson-China Medical University and Hospital Sister Institution Fund (to M.-C. Hung); Cancer Research Center of Excellence (MOHW103-TD-B-111-03, Taiwan; to M.-C. Hung); The Key Program of National Natural Science Foundation of China (31030061; to X. Xie); and National Natural Science Foundation of China (81272514; to X. Xie).

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest

The authors disclose no potential conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Harris WP, Mostaghel EA, Nelson PS, Montgomery B. Androgen deprivation therapy: progress in understanding mechanisms of resistance and optimizing androgen depletion. Nature clinical practice Urology. 2009;6:76–85. doi: 10.1038/ncpuro1296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sharifi N, Gulley JL, Dahut WL. Androgen deprivation therapy for prostate cancer. JAMA : the journal of the American Medical Association. 2005;294:238–44. doi: 10.1001/jama.294.2.238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jia L, Coetzee GA. Androgen receptor-dependent PSA expression in androgen-independent prostate cancer cells does not involve androgen receptor occupancy of the PSA locus. Cancer Res. 2005;65:8003–8. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-3679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lee SJ, Kim HS, Yu R, Lee K, Gardner TA, Jung C, et al. Novel prostate-specific promoter derived from PSA and PSMA enhancers. Molecular therapy : the journal of the American Society of Gene Therapy. 2002;6:415–21. doi: 10.1006/mthe.2002.0682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yin H, Radomska HS, Tenen DG, Glass J. Down regulation of PSA by C/EBPalpha is associated with loss of AR expression and inhibition of PSA promoter activity in the LNCaP cell line. BMC cancer. 2006;6:158. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-6-158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Maffey AH, Ishibashi T, He C, Wang X, White AR, Hendy SC, et al. Probasin promoter assembles into a strongly positioned nucleosome that permits androgen receptor binding. Molecular and cellular endocrinology. 2007;268:10–9. doi: 10.1016/j.mce.2007.01.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Trujillo MA, Oneal MJ, McDonough S, Qin R, Morris JC. A probasin promoter, conditionally replicating adenovirus that expresses the sodium iodide symporter (NIS) for radiovirotherapy of prostate cancer. Gene therapy. 2010;17:1325–32. doi: 10.1038/gt.2010.63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yu D, Jia WW, Gleave ME, Nelson CC, Rennie PS. Prostate-tumor targeting of gene expression by lentiviral vectors containing elements of the probasin promoter. The Prostate. 2004;59:370–82. doi: 10.1002/pros.20010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Briganti A. Role of hK2 in predicting clinically insignificant prostate cancer. European urology. 2007;52:1297–9. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2007.08.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Xie X, Zhao X, Liu Y, Young CY, Tindall DJ, Slawin KM, et al. Robust prostate-specific expression for targeted gene therapy based on the human kallikrein 2 promoter. Human gene therapy. 2001;12:549–61. doi: 10.1089/104303401300042483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lang JY, Hsu JL, Meric-Bernstam F, Chang CJ, Wang Q, Bao Y, et al. BikDD eliminates breast cancer initiating cells and synergizes with lapatinib for breast cancer treatment. Cancer cell. 2011;20:341–56. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2011.07.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Li LY, Dai HY, Yeh FL, Kan SF, Lang J, Hsu JL, et al. Targeted hepatocellular carcinoma proapoptotic BikDD gene therapy. Oncogene. 2011;30:1773–83. doi: 10.1038/onc.2010.558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sher YP, Tzeng TF, Kan SF, Hsu J, Xie X, Han Z, et al. Cancer targeted gene therapy of BikDD inhibits orthotopic lung cancer growth and improves long-term survival. Oncogene. 2009;28:3286–95. doi: 10.1038/onc.2009.187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Xie X, Hsu JL, Choi MG, Xia W, Yamaguchi H, Chen CT, et al. A novel hTERT promoter-driven E1A therapeutic for ovarian cancer. Molecular cancer therapeutics. 2009;8:2375–82. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-09-0056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Xie X, Xia W, Li Z, Kuo HP, Liu Y, Li Z, et al. Targeted expression of BikDD eradicates pancreatic tumors in noninvasive imaging models. Cancer cell. 2007;12:52–65. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2007.05.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Xie X, Li L, Xiao X, Guo J, Kong Y, Wu M, et al. Targeted expression of BikDD eliminates breast cancer with virtually no toxicity in noninvasive imaging models. Molecular cancer therapeutics. 2012;11:1915–24. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-12-0191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hiyama E, Hiyama K. Telomerase as tumor marker. Cancer Lett. 2003;194:221–33. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3835(02)00709-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cohen MB, Rokhlin OW. Mechanisms of prostate cancer cell survival after inhibition of AR expression. Journal of cellular biochemistry. 2009;106:363–71. doi: 10.1002/jcb.22022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Waltering KK, Urbanucci A, Visakorpi T. Androgen receptor (AR) aberrations in castration-resistant prostate cancer. Molecular and cellular endocrinology. 2012;360:38–43. doi: 10.1016/j.mce.2011.12.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Andriani F, Nan B, Yu J, Li X, Weigel NL, McPhaul MJ, et al. Use of the probasin promoter ARR2PB to express Bax in androgen receptor-positive prostate cancer cells. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2001;93:1314–24. doi: 10.1093/jnci/93.17.1314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Xie X, Zhao X, Liu Y, Zhang J, Matusik RJ, Slawin KM, et al. Adenovirus-mediated tissue-targeted expression of a caspase-9-based artificial death switch for the treatment of prostate cancer. Cancer research. 2001;61:6795–804. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Li YM, Wen Y, Zhou BP, Kuo HP, Ding Q, Hung MC. Enhancement of Bik antitumor effect by Bik mutants. Cancer Res. 2003;63:7630–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wen Y, Giri D, Yan DH, Spohn B, Zinner RG, Xia W, et al. Prostate-specific antitumor activity by probasin promoter-directed p202 expression. Mol Carcinog. 2003;37:130–7. doi: 10.1002/mc.10129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Greenberg NM, DeMayo F, Finegold MJ, Medina D, Tilley WD, Aspinall JO, et al. Prostate cancer in a transgenic mouse. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1995;92:3439–43. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.8.3439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Xie X, Luo Z, Slawin KM, Spencer DM. The EZC-prostate model: noninvasive prostate imaging in living mice. Mol Endocrinol. 2004;18:722–32. doi: 10.1210/me.2003-0316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kim NW, Piatyszek MA, Prowse KR, Harley CB, West MD, Ho PL, et al. Specific association of human telomerase activity with immortal cells and cancer. Science. 1994;266:2011–5. doi: 10.1126/science.7605428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gingrich JR, Barrios RJ, Morton RA, Boyce BF, DeMayo FJ, Finegold MJ, et al. Metastatic prostate cancer in a transgenic mouse. Cancer Res. 1996;56:4096–102. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gingrich JR, Barrios RJ, Kattan MW, Nahm HS, Finegold MJ, Greenberg NM. Androgenindependent prostate cancer progression in the TRAMP model. Cancer Res. 1997;57:4687–91. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ou-Yang F, Lan KL, Chen CT, Liu JC, Weng CL, Chou CK, et al. Endostatin-cytosine deaminase fusion protein suppresses tumor growth by targeting neovascular endothelial cells. Cancer research. 2006;66:378–84. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-1578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Adhami VM, Siddiqui IA, Syed DN, Lall RK, Mukhtar H. Oral infusion of pomegranate fruit extract inhibits prostate carcinogenesis in the TRAMP model. Carcinogenesis. 2012;33:644–51. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgr308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hurwitz AA, Foster BA, Allison JP, Greenberg NM, Kwon ED. The TRAMP mouse as a model for prostate cancer. In: Coligan JohnE, et al., editors. Current protocols in immunology. Unit 20 5. Chapter 20. 2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Konijeti R, Henning S, Moro A, Sheikh A, Elashoff D, Shapiro A, et al. Chemoprevention of prostate cancer with lycopene in the TRAMP model. The Prostate. 2010;70:1547–54. doi: 10.1002/pros.21190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Isaacs JT, Coffey DS. Adaptation versus selection as the mechanism responsible for the relapse of prostatic cancer to androgen ablation therapy as studied in the Dunning R-3327-H adenocarcinoma. Cancer Res. 1981;41:5070–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lu Y. Transcriptionally regulated, prostate-targeted gene therapy for prostate cancer. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2009;61:572–88. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2009.03.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.