Abstract

Purpose

To characterize prospective neurodevelopmental changes in brain structure in children with new and recent onset epilepsy compared to healthy controls.

Methods

34 healthy controls (mean age = 12.9) and 38 children with new/recent onset idiopathic epilepsy (mean age = 12.9) underwent 1.5T MRI at baseline and two years later. Prospective changes in total cerebral and lobar gray and white matter volumes were compared within and between groups.

Results

Prospective changes in gray matter volume were comparable for the epilepsy and control groups with significant (p<.0001) reduction in total cerebral gray matter, due primarily to significant (p<.001) reductions in frontal and parietal gray matter. Prospective white matter volume changes differed between groups. Controls exhibited a significant (p=.0012) increase in total cerebral white matter volume due to significant (p<.001) volume increases in the frontal, parietal and temporal lobes. In contrast, the epilepsy group exhibited nonsignificant white matter volume change in the total cerebrum (p=.51) as well as across all lobes (all p’s > .06). The group by white matter volume change interactions were significant for total cerebrum (p=.04) and frontal lobe (p=.04).

Discussion

Children with new and recent onset epilepsy exhibit an altered pattern of brain development characterized by delayed age appropriate increase in white matter volume. These findings may affect cognitive development through reduced brain connectivity and may also be related to the impairments in executive function commonly reported in this population.

Keywords: MRI, epilepsy, longitudinal

INTRODUCTION

Longitudinal quantitative magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) investigations of healthy children have demonstrated age and region-specific declines in cerebral gray matter volume along with concomitant increases in cerebral white matter volume (Giedd et al., 1999; Gogtay et al., 2004; Hua et al., 2009; Lenroot and Giedd 2006; Paus et al., 1999; Shaw et al., 2008; Sowell et al., 2003, 2004; Toga et al., 2006; Wilke et al., 2006), a preponderance of these changes occurring in the frontal and parietal regions in late childhood and adolescence (Giedd et al., 2009; Marsh et al., 2008; Paus et al., 2008; Sowell et al., 2003, 2004), and related to patterns of normal cognitive development (Shaw et al., 2006a). Against this backdrop, prospective neuroimaging investigations have identified a diversity of altered and abnormal patterns of brain development in youth with disorders such as childhood schizophrenia (Greenstein et al., 2006; Rapoport et al., 1999), autism (Gogtay et al., 2008; Wassink et al., 2007), ADHD (Castellanos et al., 2002; Shaw et al., 2006b, 2007), very low birthweight (Ment et al., 2009), and bipolar disorder (Gogtay et al., 2007; Lazaro et al., 2009).

While epilepsy is a prevalent neurological disorder of childhood (Hauser 1995; Shinnar and Pellock 2002), but the number of prospective quantitative MRI studies examining trajectories of brain development compared to healthy controls is extraordinary small and limited to regions of interest (Provenzale et al., 2008). Cross-sectional studies of children with chronic localization related epilepsy using traditional morphometrics and voxel based morphometrics have revealed distributed abnormalities in the overall cerebrum, cerebellum, frontal and temporal lobes, hippocampus, amygdala, and thalamus (Lawson et al., 1997, 1998, 2000; Cormack et al., 2005; Daley et al., 2006, 2007, 2008; Guimaraes et al., 2007; Caplan et al., 2008). Similar cross-sectional investigations of children with idiopathic generalized epilepsies including childhood absence and juvenile myoclonic epilepsy have revealed distributed patterns of abnormality predominantly affecting thalamus and frontal lobe (Betting et al., 2006a,b,c; Pardoe et al., 2008; Pulsipher et al., 2009), but also with reports of abnormal volumes of the amygdala and regions of the temporal and frontal lobes (Caplan et al., 2009; Schreibman et al., 2009). Collectively, these studies clearly indicate a neurodevelopmental contribution to anatomic abnormalities that have been observed in adults with these syndromes of epilepsy (c.f., Hermann et al., 2008), but the onset and course of their emergence remains uncertain.

Controlled prospective investigations initiated at or near epilepsy onset are best suited to characterize the nature, timing, and course of neuroimaging abnormalities in pediatric epilepsy—or their natural history. In this report we provide the first characterization of prospective volumetric changes in total cerebral and lobar gray and white matter in children with recent onset idiopathic epilepsies who were examined at the time of diagnosis and two years later.

METHODS

Subjects

Research participants included children with new/recent onset epilepsy (n=38) and healthy first-degree cousin controls (n=34), aged 8-18 years, all attending regular schools. Initial selection criteria included: 1) diagnosis of epilepsy within the past 12 months, 2) chronological age between 8-18 years, 3) no other neurological disorders (e.g., autism), and 4) normal clinical MRI. Epilepsy participants met criteria for classification of idiopathic epilepsy in that they had normal neurological examinations, no identifiable lesions on MR imaging, and no other signs or symptoms indicative of neurological abnormality (Engel 2001). Control participants were age and gender-matched first-degree cousins. Criteria for controls included no histories of: 1) any initial precipitating events (e.g., simple or complex febrile seizures, preor perinatal insults, cerebral infections, non-cerebral disease with prolonged hospitalization, or closed head injuries with loss of consciousness greater than 5 minutes), 2) any seizure-like episode, 3) diagnosed neurological disease, or 4) other family history of a first-degree relative with epilepsy or febrile convulsions. 94% of the initial cohort was retained and returned for prospective evaluation.

This study was reviewed and approved by the Institutional Review Boards of both institutions and on the day of study participation families and children gave informed consent and assent and all procedures were consistent with the Declaration of Helsinki (1991).

Quantitative MRI

MRI Acquisition

Images were obtained on a 1.5 Tesla GE Signa MR scanner. Sequences acquired for each participant included: (i) T1-weighted, three-dimensional SPGR acquired with the following parameters: TE = 5ms, TR = 24ms, flip angle = 40deg, NEX = 1, slice thickness = 1.5 mm, slices = 124, plane = coronal, FOV = 200mm, matrix = 256×256; (ii) proton density (PD) and (iii) T2-weighted images are acquired with the following parameters: TE = 36ms (for PD) or 96 msec (for T2), TR = 3000 ms, NEX = 1, slice thickness = 3.0 mm, slices = 64, slice plane = coronal, FOV = 200mm, matrix = 256×256.

Standard Work-Up

MRIs were processed using the Brains2 software package (Andreasen et al., 1996; Harris et al., 1999; Magnotta et al., 2002; Magnotta et al., 1999). MR processing staff was blinded to the clinical, sociodemographic and neuropsychological characteristics of the participants. The T1 weighted images were resampled to 1.0mm cubic voxels, then spatially normalized so that the anterior-posterior axis of the brain was realigned to the anterior-posterior commissural (AC-PC) line, and the interhemispheric fissure was aligned on the other two axes. A piecewise linear transformation was defined providing the ability to warp the standard Talairach atlas space (Talairach 1988) onto the re-sampled image. Images from the three pulse sequences were then co-registered using a local adaptation of automated image registration software (Woods et al., 1998). Following alignment of the image sets, the PD and T2 images were re-sampled into 1mm cubic voxels after which an automated algorithm classified each voxel into gray matter, white matter, CSF, blood, or unclassified (Harris et al., 1999). The brains were then “removed” from the skull using a neural network application that had been trained on a set of manual traces (Magnotta et al., 2002). Manual inspection and correction of the output of the neural network tracing was conducted. The brain images were then volume rendered using local utilities, producing tissue volumes for regions of interest within the brain. The six outer boundaries of the brain forms a bounding box that along with the AC-PC line produces a volumetric grid based on the Talairach divisions. Each lobar volume measured is defined in this proportional coordinate system. Thus all measurements are obtained in the image space of the subject without morphing the image to fit a standard brain atlas. This research imaging was performed within one year of the diagnosis of epilepsy which was completed at the same visit where the neuropsychological and psychiatric evaluations were performed.

Longitudinal Work-Up

Time two follow-up scans are acquired using the same MR scanning parameters as the baseline scan. The T1 weighted follow up scan is sampled into cubic voxels and re-aligned into the same orientation as the previously processed baseline scan. The resulting transform is saved as an initialization file for the image registration of the follow-up scan to the baseline scan. The final fitting between baseline and follow up scan uses a linear affine transformation that generates the best fit between the two scans without altering the image dimensions. The Talairach parameters which define the bounding box for measurements are copied from the time one workup and checked for accuracy on the time two scan. The remainder of the time two workup is the same as that used for time one. The T2 and PD weighted images are fit to the realigned T1 image followed by tissue segmentation, and measurement.

A required change to another 1.5T GE scanner was made during the course of the study, but an equal proportion of children with epilepsy (57.4%) and healthy controls (51.2%) were involved in this change and, in addition, phantom studies revealed < 1% volume difference between the GE machines.

Statistical Analysis

Differences between the epilepsy and control groups were examined using linear regression models in which the dependent variable was the change in segmented gray or white matter volume in cm3. Gray matter and white matter were examined separately. Overall change was examined using standard linear regression models in which group (epilepsy, controls) was treated as a factor. Changes in lobar volumes (frontal, parietal, temporal, occipital) were examined using linear mixed-effects models in which group (epilepsy, control), lobe, and their interaction were included as factors and a random intercept for each subject was included to take into account the within-subject correlation across lobes. This model allows one to take advantage of the multiple measures on the same subject and test the changes across all four lobes within the same model. Each model was fit twice, once including the fixed intercept term in order to evaluate the statistical significance of the difference between the control and epilepsy groups, and once eliminating this fixed intercept term and including indicators for both the control and epilepsy groups (and in the lobar models, their interactions with lobe) in order to evaluate the significance of the change in volume between time one and time two results in both groups. The significance levels of the changes over time found using the latter model fit are the critical equivalent of testing the joint significance of the intercept and appropriate group, lobe, and interaction terms. These two model fits are statistically equivalent parameterizations of the model, but allow us to examine different aspects of the model fit, that is, the differences across groups and changes over time.

Additional covariates were examined including subject age, gender, and intracranial volume at baseline. There were no differences across any of these covariates in regard to change in gray matter volume. When change in white matter volume was examined, there was evidence of a nonlinear relationship between age and the volume change. Further analyses suggested that the natural log of age provided the best fit for this relationship. In order to make the results of the white matter analyses more easily interpretable and more directly comparable to those of the changes in gray matter, the effect of age was centered at age 13, the mean age of the sample, by subtracting the natural log of 13 from the natural log of age. This adjusted measure was included as a covariate in all of the analyses of change in white matter volume presented in this paper.

RESULTS

Table 1 provides the demographic characteristics of the research participants at baseline. There were no significant differences between the epilepsy and control groups in age, gender, height, weight, head circumference or grade (all p’s >.45). The children were followed up as close as possible 24 months following their baseline scan. The epilepsy group contained 21 children with localization-related epilepsy and 17 with idiopathic generalized epilepsy.

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics

| Controls (n = 34) Mean (SD) |

Epilepsy (n = 38) Mean (SD) |

|

|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 12.94 (3.2) | 12.97 (3.3) |

| Gender (M/F) | 18/20 | 19/15 |

| Head Circumference (cm) | 55.3 (2.6) | 55.2 (2.8) |

| Height (inches) | 61.5 (6.3) | 60.4 (5.3) |

| Weight (lbs) | 118.9 (40.8) | 119.2 (47.5) |

| Age at diagnosis (years) | - | 12.3 (3.6) |

| Duration of epilepsy (months) | - | 8.9 (4.3) |

| Localization-related epilepsies | - | 21 |

| Generalized epilepsies | - | 17 |

| Number of AEDs | ||

| 0 | - | 7 |

| 1 | - | 31 |

| 2 | - | 0 |

Table 1 shows that 7 children were not on medications. The children who were not on medications were diagnosed with BECTS (n=5) and absence epilepsy (n=2). The absence of medications was due to two factors. First, treating clinicians discussed potential adverse effects of AEDs with parents and their choice in some of these cases was not to treat. Second, some of the clinicians did not treat if there were no further detectable daytime clinical seizures and 3HzGSW occurred only during sleep. Seizure frequency was evaluated at the follow-up visit. Seizure control was quite favorable in this group overall. At follow-up, 53% (n=20) were seizure free the past year and 34% (n=13) reported only one seizure the past year. A minority of children/families reported monthly (5%, n=2), weekly (5%, n=2), or daily (3%, n=1) seizures. There was not a significant difference between the LRE and IGE groups in overall seizure frequency (X2 p=.55).

Changes in Total Cerebral Gray and White Matter

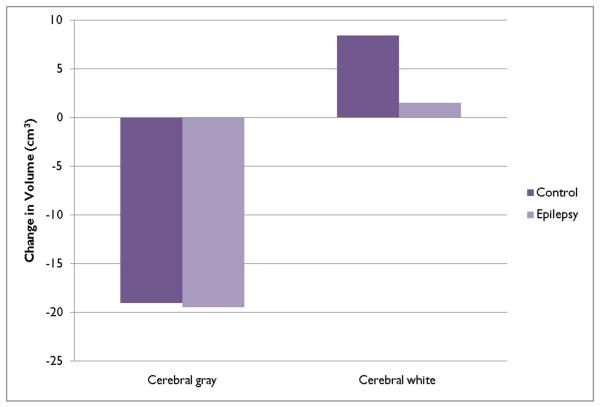

Table 2 provides a summary of the volumetric changes in total cerebral gray and white matter volumes for the epilepsy and control children and Figure 1 provides a schematic summary of the developmental trends at the mean age of the sample.

Table 2.

Prospective change in total cerebral tissue volumes.

| Gray Matter | White Matter | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Value | Std Err | p-value | Ep-Con | Std Err | p-value | Value | Std Err | p-value | Ep-Con | Std Err | p-value | |

| Control | −19.00 | 4.21 | <0.0001 | −0.44 | 5.74 | 0.9385 | 8.47 | 2.49 | 0.0012 | −6.96 | 3.39 | 0.0443 |

| Epilepsy | −19.44 | 3.91 | <0.0001 | 1.51 | 2.31 | 0.5158 | ||||||

| ln(T1 Age) | −20.10 | 6.63 | 0.0035 | |||||||||

Figure 1.

Prospective changes in cerebral gray and white matter volumes.

The second column of Table 2 (value) provides the mean change in cerebral gray matter for the control and epilepsy groups estimated from the regression analysis. The volume of total cerebral gray matter declined among both the controls and children with epilepsy. The decline among the control group was 19.0 cm3 (p < 0.0001) while the decline among children with epilepsy was 19.44 cm3 (p< 0.0001). The difference between the control and epilepsy groups was negligible and not statistically significant (p=0.94). There was no effect of age, suggesting that this decline was similar across children of different ages.

The changes in cerebral white matter volume differed between the epilepsy and controls groups. Table 2 and Figure 1 characterize the change in white matter volume at the mean age of the sample as predicted in the regression model. The increase in the controls was 8.47 cm3 (p=0.0012) while the increase among children with epilepsy was much smaller, 1.51 cm3, and not significantly different from baseline volume (p=0.52). The difference in white matter growth between the epilepsy and control groups was statistically significant (p=0.0443).

The change in white matter volume declined across age, such that older children exhibited smaller increases in white matter volume than younger children, a rate of change that was steeper at younger than at older ages. Among children who were 8 years old at baseline, white matter volume increased by 11.3 cm3 among the epilepsy group and 18.2 cm3 among the controls. Both of these increases were statistically significant at the p<0.01 level. Among older children, the increases in white matter were smaller, such that 14 year-old children in the epilepsy group saw no increases in white matter volume and those over age 14 saw declines. No interaction between age and epilepsy status was found, which suggests that the difference between the control and epilepsy groups was similar across age. As a result, even the oldest children in the control group showed an increase in white matter volume between the two time points, though this increase was smaller and not statistically significant. We examined differences within the epilepsy group by syndrome (partial versus generalized) and medication status (no medication versus at least one medication). There was no evidence of a difference by syndrome or medication status.

Changes in Lobar Gray and White Matter

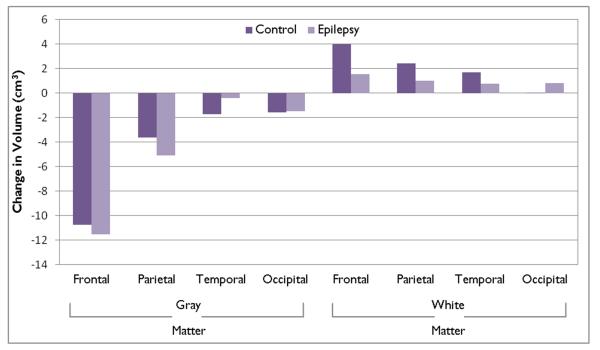

Table 3 provides a summary of the predicted changes in lobar gray and white matter volumes for the epilepsy and control groups while Figure 2 provides a schematic summary of these developmental trends.

Table 3.

Prospective change in total lobar volumes

| Gray Matter | White Matter | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Value | Std Err | p-value | Ep-Con | Std Err | p-value | Value | Std Err | p-value | Ep-Con | Std Err | p-value | |

| Frontal | ||||||||||||

| Control | −10.77 | 1.35 | 0.0000 | −0.75 | 1.85 | 0.6847 | 3.97 | 0.88 | 0.0000 | −2.42 | 1.20 | 0.0475 |

| Epilepsy | −11.53 | 1.26 | 0.0000 | 1.54 | 0.82 | 0.0602 | ||||||

| Parietal | ||||||||||||

| Control | −3.61 | 1.35 | 0.0083 | −1.50 | 1.85 | 0.4208 | 2.42 | 0.88 | 0.0065 | −1.40 | 1.20 | 0.2463 |

| Epilepsy | −5.11 | 1.26 | 0.0001 | 1.02 | 0.82 | 0.2151 | ||||||

| Temporal | ||||||||||||

| Control | −1.71 | 1.35 | 0.2083 | 1.32 | 1.85 | 0.4772 | 1.71 | 0.88 | 0.0344 | −0.97 | 1.20 | 0.4209 |

| Epilepsy | −0.39 | 1.26 | 0.7573 | 0.74 | 0.82 | 0.3673 | ||||||

| Occipital | ||||||||||||

| Control | −1.58 | 1.35 | 0.2446 | 0.11 | 1.85 | 0.9534 | 0.03 | 0.88 | 0.9710 | −1.24 | 1.20 | 0.3056 |

| Epilepsy | −1.47 | 1.26 | 0.2428 | −1.21 | 0.82 | 0.1411 | ||||||

| In(T1 Age) | −4.72 | 1.65 | 0.0057 | |||||||||

Figure 2.

Prospective changes in lobar gray and white matter volumes.

Table 3 provides information regarding the mean change in gray matter across each of the four lobes separately by group. Among both the control and the epilepsy groups, there was a decline in the volume of gray matter in the frontal and parietal lobes, but not the temporal and occipital lobes. The volume of frontal lobe gray matter declined by 10.8 cm3 among the control group (p<0.0001) and by 11.5 cm3 among the children with epilepsy (p<0.0001), while parietal lobe gray matter volume declined by 3.6 cm3 among the controls (p=0.0083) and by 5.1 cm3 among the epilepsy group (p=0.0001). The mean declines in temporal and occipital lobes were less than 2 cm3 and did not reach statistical significance. The declines in cerebral gray matter did not vary by age of the subject.

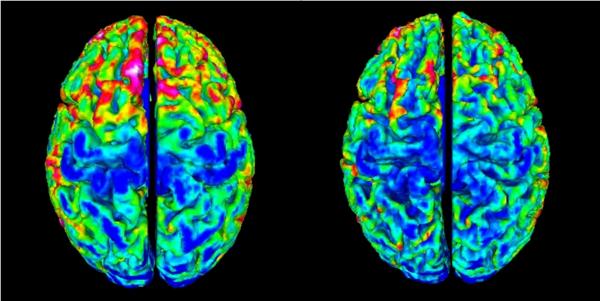

The changes in cerebral gray matter can be appreciated visually via a map of cortical depth (Figure 3) for one child at baseline (left panel) and two years later (right panel). Thinning of the gray matter can be appreciated over the interval, particularly evident in frontal and parietal regions.

Figure 3.

Cortical thickness maps for an individual child over the two year interval. Especially evident is decreased thickness in frontal regions (red-yellow = increased thickness, green-blue = decreased thickness).

Table 3 (value) reports the mean change in white matter for each lobe at the mean age of the sample. The control group exhibited widespread increases including an increase of 4.0 cm3 in the frontal lobe (p<0.0001), 2.4 cm3 in the parietal lobe (p=0.0065), and 1.7 cm3 in the temporal lobe (p= 0.0344). No change was observed in the occipital lobe. In contrast, the increases in white matter volume in the children with epilepsy were much smaller and not significant including 1.5 cm3 in the frontal lobe (p=0.0602), 1.0 cm3 in the parietal lobes (p=0.2151), and 0.7 cm3 in the temporal lobe (p=0.3673). Cerebral white matter declined by 1.2 cm3 in the occipital lobe, but this decline did not reach statistical significance (p=0.1411). Only the difference in the frontal lobe between the epilepsy and control group reached statistical significance (p=0.0475).

As was observed regarding change in total cerebral white matter, the increase in lobar white matter was smaller among older than younger children. Though 8-year olds in both the epilepsy and control groups experienced an increase in white matter between baseline and two year follow-up, by 3.8 cm3 and 6.3 cm3 respectively, the increase in white matter declined among older children such that by age 18, the epilepsy group experienced no change, while white matter increased by only 2.5 cm3 among the controls.

Supplemental analyses

Additional analyses were undertaken to address two issues. The first concerned possible prospective differences between the LRE and IGE groups in white matter development. In terms of total cerebral white matter, there was a small difference between the groups in mean change, but this appeared to be due to the 2.8 year difference in average age. When differences in age were controlled there was no significant difference between the LRE and IGE groups and neither group showed a significant increase in white matter over time (LRE p= .31, IGE p= .85). Regarding change in specific lobar white matter volumes, there were no increases by either group in the parietal, temporal, or occipital lobes (all p’s >0.17), and in the frontal lobe the IGE showed no interval increase while LRE showed an increase (p =.034). After adjusting for differences in age, there was no difference between the control and LRE epilepsy groups in the interval increase, but the IGE group showed less interval growth than either of these growths (p<0.04). This suggests differences between the control and epilepsy groups in the change in frontal lobe white matter were driven by slowed growth within the IGE epilepsy group.

The second issue concerned the possible confounding effects of neurobehavioral comorbidities on the white matter findings. Some neurobehavioral comorbidities with associated baseline imaging volumetric abnormalities are common in children with epilepsy including academic problems and ADHD. To rule out the possibility that the comorbidity groups were accounting for the abnormal white matter development, those children with epilepsy without ADHD or academic problems were examined specifically. Children with “epilepsy only” showed no significant increase in total cerebral white matter or any lobar volume (all p’s >.07). Thus, children with epilepsy with neurobehavioral complications were not responsible for the reported findings.

Discussion

Two core findings emerge from this investigation. First, prospective changes (reductions) in cerebral gray matter volumes appear to be proceeding at a normal rate in children with epilepsy compared to healthy controls. Second, and in contrast, there appears to be a significant delay in the rate of white matter volume increase among children with epilepsy compared to controls.

Prospective change in gray matter

Cerebral gray matter volumes declined significantly in the epilepsy and control groups over the prospective two year period, the changes virtually identical in both groups, with statistically significant declines in total cerebral gray matter volume. Inspection of total lobar regions indicated similar region-specific patterns of change, with significant reductions in frontal and parietal lobes, but not temporal or occipital lobes. Importantly, there were no significant group differences in the rate of gray matter volume change across any measure total or lobar gray matter. In summary, in this group of children with new/recent onset idiopathic epilepsies, there were no significant differences compared to healthy controls in the prospective 2-year pattern of change in total cortical gray matter volume.

Prospective change in white matter

Total cerebral white matter volume increased significantly in the healthy controls over the two year period but was clearly attenuated in the children with epilepsy, resulting in a significant group difference in the two year neurodevelopmental trajectory. Again, there was a region specific pattern of white matter volume increase in the controls, with significantly increased volumes in the frontal, parietal and temporal but not occipital lobes. In contrast, the epilepsy group showed no significant prospective change in any lobar volume. There was a significant group by lobe interaction in the frontal lobes where white matter volume was significantly lagging.

We previously suggested that white matter volume abnormalities observed in chronic epilepsy reflected a neurodevelopmental vulnerability associated with an early insult to the developing brain which affected subsequent development of normal brain connectivity (Hermann et al., 2002; Seidenberg et al., 2005). Cross-sectional investigations of specific white matter tracks such as the corpus callosum were consistent with this hypothesis (Hermann et al., 2003; Weber et al., 2007), but the timing of the effect remained uncertain. In this investigation, direct evidence of slowed white matter development in the context of childhood onset epilepsy was obtained.

Several additional lines of evidence point to the presence of white matter abnormalities in childhood epilepsy. Recent investigations of white matter microstructure using diffusion tensor imaging in children has characterized distributed/bilateral abnormality in the context of lateralized localization-related epilepsies. Govindan et al.(2008) reported decreased anistrophy in all four white matter tracks investigated (corticospinal track and the uncinate, arcuate and inferior longitudinal fasciculi) both ipsilateral and contralateral to side of seizure onset in children with left temporal lobe epilepsy. In addition, an association was detected between duration of epilepsy with 3 of 4 tracks ipsilateral to side of onset suggesting a progressive component. Nilsson et al. (2008) reported bilaterally increased parallel and perpindicular diffusivity with preserved FA in the white matter of temporal lobe and cingulate gyrus in children with temporal lobe epilepsy. Lastly, we reported previously (Hermann et al., 2006) that while baseline white matter volumes were comparable in new onset epilepsy and control groups, the significant associations between cognition and white matter volume observed in controls were completely absent in new/recent onset epilepsy. This dissociation raised the hypothesis that abnormalities in white matter microstructure may be present in the context of normal white matter volumes in new onset childhood epilepsy, a hypothesis that was recently confirmed (Hutchinson et al., In press). Interestingly, radial but not axial diffusivity was altered in some areas of interest (e.g., posterior corpus callosum). Although there is no definitive microstructural change certain to underlie this pattern, there are a growing number of DTI studies relating altered Drad to myelination abnormalities (Budde et al., 2007; Song et al., 2005) and showing a reduction of Drad during normal white matter development in humans thought to correspond to compacting fibers and myelination (Alexander et al., 2007; Hasan et al., 2009; Snook et al., 2005). It is possible that the myelination of axons in the children with epilepsy was slowed by the epileptogenic process or that there was seizure-related damage to the posterior corpus callosum myelin sheath surrounding the onset of epilepsy.

Limitations

Several potential limitations of this investigation and areas for future research should be mentioned. Case ascertainment was determined by the onset of spontaneous unprovoked seizures, normal clinical imaging, attendance at regular school, and a diagnosis of epilepsy—children characterized by Oostrom et al (2003) as “epilepsy only”. Cohorts of this type provide the advantage of investigating brain development in the absence of severe etiological insults, brain lesions, and other complicating factors associated with other common but more severe childhood epilepsies. The relative impact of these more severe epilepsies to developmental brain changes remains to be determined. The presence of even subtle MR abnormalities identified at the onset of epilepsy (Doescher et al., 2006) has been found to be associated with baseline cognitive abnormalities (Byars et al., 2007), and whether differential effects are associated with subsequent brain development is uncertain.

While variable prospective trajectories were evident in gray and white matter across groups, the duration of the follow-up period was modest (2 years). Longer follow-up would be of particular interest to determine whether some children with epilepsy might demonstrate accelerated change, eventually matching or “catching up” with controls as has been described in some neurodevelopmental disorders (Shaw et al., 2007).

Significant changes are occurring in the cognitive development of children within the age range represented in this investigation (8-18 years). Very little is known about how subtle neurodevelopmental alterations in brain development affect cognition in epilepsy. There should be a degree of symmetry between patterns of neurocognitive change and age-appropriate brain development and this area of research remains to be addressed in childhood epilepsy.

Finally, we examined white and gray matter volumes based on total lobar measurements. Subsequent and more specific investigations using sophisticated techniques such as diffusion tensor imaging with tractography, examining more specific patterns of connectivity, and changes in early versus later developing fiber tracts, would advance understanding of these neurodevelopmental effects, as would closer characterization of changes in cortical morphology (thickness, curvature, complexity) within lobar regions along with examination of subcortical structures and cerebellum.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This manuscript was supported in part by NIH RO1 44351. We confirm that we have read the Journal’s position on issues involved in ethical publication and affirm that this report is consistent with those guidelines.

Footnotes

We have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

References

- World Medical Association World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki. The Journal of Law, Medicine & Ethics. 1991;19:264–265. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alexander AL, Lee JE, Lazar M, Boudos R, DuBray MB, Oakes TR, Miller JN, Lu J, Jeong EK, McMahon WM, Bigler ED, Lainhart JE. Diffusion tensor imaging of the corpus callosum in Autism. Neuroimage. 2007;34:61–73. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2006.08.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andreasen NC, Rajarethinam R, Cizadlo T, Arndt S, Swayze VW, 2nd, Flashman LA, O’Leary DS, Ehrhardt JC, Yuh WT. Automatic atlas-based volume estimation of human brain regions from MR images. J Comput Assist Tomogr. 1996;20:98–106. doi: 10.1097/00004728-199601000-00018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Betting LE, Mory SB, Li LM, Lopes-Cendes I, Guerreiro MM, Guerreiro CA, Cendes F. Voxel-based morphometry in patients with idiopathic generalized epilepsies. Neuroimage. 2006a;32:498–502. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2006.04.174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Betting LE, Mory SB, Lopes-Cendes I, Li LM, Guerreiro MM, Guerreiro CA, Cendes F. MRI reveals structural abnormalities in patients with idiopathic generalized epilepsy. Neurology. 2006b;67:848–852. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000233886.55203.bd. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Betting LE, Mory SB, Lopes-Cendes I, Li LM, Guerreiro MM, Guerreiro CA, Cendes F. MRI volumetry shows increased anterior thalamic volumes in patients with absence seizures. Epilepsy Behav. 2006c;8:575–580. doi: 10.1016/j.yebeh.2006.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Budde MD, Kim JH, Liang HF, Schmidt RE, Russell JH, Cross AH, Song SK. Toward accurate diagnosis of white matter pathology using diffusion tensor imaging. Magn Reson Med. 2007;57:688–695. doi: 10.1002/mrm.21200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Byars AW, deGrauw TJ, Johnson CS, Fastenau PS, Perkins SM, Egelhoff JC, Kalnin A, Dunn DW, Austin JK. The association of MRI findings and neuropsychological functioning after the first recognized seizure. Epilepsia. 2007;48:1067–1074. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1167.2007.01088.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caplan R, Levitt J, Siddarth P, Taylor J, Daley M, Wu KN, Gurbani S, Shields WD, Sankar R. Thought disorder and frontotemporal volumes in pediatric epilepsy. Epilepsy Behav. 2008;2008:593–9. doi: 10.1016/j.yebeh.2008.06.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caplan R, Levitt J, Siddarth P, Wu KN, Gurbani S, Sankar R, Shields WD. Frontal and temporal volumes in childhood absence epilepsy. Epilepsia. 2009;50:2466–72. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1167.2009.02198.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castellanos FX, Lee PP, Sharp W, Jeffries NO, Greenstein DK, Clasen LS, Blumenthal JD, James RS, Ebens CL, Walter JM, Zijdenbos A, Evans AC, Giedd JN, Rapoport JL. Developmental trajectories of brain volume abnormalities in children and adolescents with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Jama. 2002;288:1740–1748. doi: 10.1001/jama.288.14.1740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cormack F, Gadian DG, Vargha-Khadem F, Cross JH, Connelly A, Baldeweg T. Extra-hippocampal grey matter density abnormalities in paediatric mesial temporal sclerosis. Neuroimage. 2005;27:635–643. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2005.05.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daley M, Ott D, Blanton R, Siddarth P, Levitt J, Mormino E, Hojatkashani C, Tenorio R, Gurbani S, Shields WD, Sankar R, Toga A, Caplan R. Hippocampal volume in childhood complex partial seizures. Epilepsy Res. 2006;72:57–66. doi: 10.1016/j.eplepsyres.2006.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daley M, Levitt J, Siddarth P, Mormino E, Hojatkashani C, Gurbani S, Shields WD, Sankar R, Toga A, Caplan R. Frontal and temporal volumes in children with epilepsy. Epilepsy Behav. 2007;10:470–6. doi: 10.1016/j.yebeh.2007.02.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daley M, Siddarth P, Levitt J, Gurbani S, Shields WD, Sankar R, Toga A, Caplan R. Amygdala volume and psychopathology in childhood complex partial seizures. Epilepsy Behav. 2008;13:212–217. doi: 10.1016/j.yebeh.2007.12.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doescher JS, deGrauw TJ, Musick BS, Dunn DW, Kalnin AJ, Egelhoff JC, Byars AW, Mathews VP, Austin JK. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and electroencephalographic (EEG) findings in a cohort of normal children with newly diagnosed seizures. J Child Neurol. 2006;21:491–495. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Engel J., Jr A proposed diagnostic scheme for people with epileptic seizures and with epilepsy: report of the ILAE Task Force on Classification and Terminology. Epilepsia. 2001;42:796–803. doi: 10.1046/j.1528-1157.2001.10401.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giedd JN, Blumenthal J, Jeffries NO, Castellanos FX, Liu H, Zijdenbos A, Paus T, Evans AC, Rapoport JL. Brain development during childhood and adolescence: a longitudinal MRI study. Nat Neurosci. 1999;2:861–863. doi: 10.1038/13158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giedd JN, Lalonde FM, Celano MJ, White SL, Wallace GL, Lee NR, Lenroot RK. Anatomical brain magnetic resonance imaging of typically developing children and adolescents. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2009;48:465–470. doi: 10.1097/CHI.0b013e31819f2715. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gogtay N, Giedd JN, Lusk L, Hayashi KM, Greenstein D, Vaituzis AC, Nugent TF, 3rd, Herman DH, Clasen LS, Toga AW, Rapoport JL, Thompson PM. Dynamic mapping of human cortical development during childhood through early adulthood. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:8174–8179. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0402680101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gogtay N, Lu A, Leow AD, Klunder AD, Lee AD, Chavez A, Greenstein D, Giedd JN, Toga AW, Rapoport JL, Thompson PM. Three-dimensional brain growth abnormalities in childhood-onset schizophrenia visualized by using tensor-based morphometry. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:15979–15984. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0806485105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gogtay N, Ordonez A, Herman DH, Hayashi KM, Greenstein D, Vaituzis C, Lenane M, Clasen L, Sharp W, Giedd JN, Jung D, Nugent TF, 3rd, Toga AW, Leibenluft E, Thompson PM, Rapoport JL. Dynamic mapping of cortical development before and after the onset of pediatric bipolar illness. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2007;48:852–862. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2007.01747.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Govindan RM, Makki MI, Sundaram SK, Juhasz C, Chugani HT. Diffusion tensor analysis of temporal and extra-temporal lobe tracts in temporal lobe epilepsy. Epilepsy Res. 2008;80:30–41. doi: 10.1016/j.eplepsyres.2008.03.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenstein D, Lerch J, Shaw P, Clasen L, Giedd J, Gochman P, Rapoport J, Gogtay N. Childhood onset schizophrenia: cortical brain abnormalities as young adults. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2006;47:1003–1012. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2006.01658.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guimaraes CA, Bonilha L, Franzon RC, Li LM, Cendes F, Guerreiro MM. Distribution of regional gray matter abnormalities in a pediatric population with temporal lobe epilepsy and correlation with neuropsychological performance. Epilepsy Behav. 2007;11:558–566. doi: 10.1016/j.yebeh.2007.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris G, Andreasen NC, Cizadlo T, Bailey JM, Bockholt HJ, Magnotta VA, Arndt S. Improving tissue classification in MRI: a three-dimensional multispectral discriminant analysis method with automated training class selection. J Comput Assist Tomogr. 1999;23:144–154. doi: 10.1097/00004728-199901000-00030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hasan KM, Kamali A, Iftikhar A, Kramer LA, Papanicolaou AC, Fletcher JM, Ewing-Cobbs L. Diffusion tensor tractography quantification of the human corpus callosum fiber pathways across the lifespan. Brain Res. 2009;1249:91–100. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2008.10.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hauser WA. Epidemiology of epilepsy in children. Neurosurg Clin N Am. 1995;6:419–429. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hermann B, Hansen R, Seidenberg M, Magnotta V, O’Leary D. Neurodevelopmental vulnerability of the corpus callosum to childhood onset localization-related epilepsy. Neuroimage. 2003;18:284–292. doi: 10.1016/s1053-8119(02)00044-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hermann B, Jones J, Sheth R, Dow C, Koehn M, Seidenberg M. Children with new-onset epilepsy: neuropsychological status and brain structure. Brain. 2006;129:2609–2619. doi: 10.1093/brain/awl196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hermann B, Seidenberg M, Bell B, Rutecki P, Sheth R, Ruggles K, Wendt G, O’Leary D, Magnotta V. The neurodevelopmental impact of childhood-onset temporal lobe epilepsy on brain structure and function. Epilepsia. 2002;43:1062–1071. doi: 10.1046/j.1528-1157.2002.49901.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hermann B, Seidenberg M, Jones J. The neurobehavioural comorbidities of epilepsy: can a natural history be developed? The Lancet Neurology. 2008;7:151–160. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(08)70018-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hua X, Leow AD, Levitt JG, Caplan R, Thompson PM, Toga AW. Detecting brain growth patterns in normal children using tensor-based morphometry. Hum Brain Mapp. 2009;30:209–219. doi: 10.1002/hbm.20498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hutchinson B, Pulsipher D, Dabbs K, Myers y Gutierrez A, Sheth R, Jones J, Seidenberg M, Meyerand ME, Hermann BP. Children with new onset epilepsy exhibit diffusion abnormalities in cerebral white matter in the absence of volumetric differences. Epilepsy Res. doi: 10.1016/j.eplepsyres.2009.11.011. (In press) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lawson JA, Cook MJ, Bleasel AF, Nayanar V, Morris KF, Bye AM. Quantitative MRI in outpatient childhood epilepsy. Epilepsia. 1997;38:1289–1293. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1157.1997.tb00066.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lawson JA, Nguyen W, Bleasel AF, Pereira JK, Vogrin S, Cook MJ, Bye AM. ILAE-defined epilepsy syndromes in children: correlation with quantitative MRI. Epilepsia. 1998;39:1345–1349. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1157.1998.tb01335.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lawson JA, Vogrin S, Bleasel AF, Cook MJ, Bye AM. Cerebral and cerebellar volume reduction in children with intractable epilepsy. Epilepsia. 2000;41:1456–1462. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1157.2000.tb00122.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lazaro L, Bargallo N, Castro-Fornieles J, Falcon C, Andres S, Calvo R, Junque C. Brain changes in children and adolescents with obsessive-compulsive disorder before and after treatment: a voxel-based morphometric MRI study. Psychiatry Res. 2009;172:140–146. doi: 10.1016/j.pscychresns.2008.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lenroot RK, Giedd JN. Brain development in children and adolescents: insights from anatomical magnetic resonance imaging. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2006;30:718–729. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2006.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Magnotta VA, Harris G, Andreasen NC, O’Leary DS, Yuh WT, Heckel D. Structural MR image processing using the BRAINS2 toolbox. Computerized Medical Imaging and Graphics. 2002;26:251–264. doi: 10.1016/s0895-6111(02)00011-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Magnotta VA, Heckel D, Andreasen NC, Cizadlo T, Corson PW, Ehrhardt JC, Yuh WT. Measurement of brain structures with artificial neural networks: two- and three-dimensional applications. Radiology. 1999;211:781–790. doi: 10.1148/radiology.211.3.r99ma07781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marsh R, Gerber AJ, Peterson BS. Neuroimaging studies of normal brain development and their relevance for understanding childhood neuropsychiatric disorders. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2008;47:1233–1251. doi: 10.1097/CHI.0b013e318185e703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ment LR, Kesler S, Vohr B, Katz KH, Baumgartner H, Schneider KC, Delancy S, Silbereis J, Duncan CC, Constable RT, Makuch RW, Reiss AL. Longitudinal brain volume changes in preterm and term control subjects during late childhood and adolescence. Pediatrics. 2009 doi: 10.1542/peds.2008-0025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nilsson D, Go C, Rutka JT, Rydenhag B, Mabbott DJ, Snead OC, 3rd, Raybaud CR, Widjaja E. Bilateral diffusion tensor abnormalities of temporal lobe and cingulate gyrus white matter in children with temporal lobe epilepsy. Epilepsy Res. 2008;81:128–135. doi: 10.1016/j.eplepsyres.2008.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oostrom KJ, Smeets-Schouten A, Kruitwagen CL, Peters AC, Jennekens-Schinkel A. Not only a matter of epilepsy: early problems of cognition and behavior in children with “epilepsy only”--a prospective, longitudinal, controlled study starting at diagnosis. Pediatrics. 2003;112:1338–1344. doi: 10.1542/peds.112.6.1338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pardoe H, Pell GS, Abbott DF, Berg AT, Jackson GD. Multi-site voxel-based morphometry: methods and a feasibility demonstration with childhood absence epilepsy. Neuroimage. 2008;42:611–616. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2008.05.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paus T, Keshavan M, Giedd JN. Why do many psychiatric disorders emerge during adolescence? Nat Rev Neurosci. 2008;9:947–957. doi: 10.1038/nrn2513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paus T, Zijdenbos A, Worsley K, Collins DL, Blumenthal J, Giedd JN, Rapoport JL, Evans AC. Structural maturation of neural pathways in children and adolescents: in vivo study. Science. 1999;283:1908–1911. doi: 10.1126/science.283.5409.1908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Provenzale JM, Barboriak DP, VanLandingham K, MacFall J, Delong D, Lewis DV. Hippocampal signal hyperintensity after febrile status epilepticus is predictive of subsequent mesial temporal sclerosis. AJR American Journal of Radiology. 2008;190:976–983. doi: 10.2214/AJR.07.2407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pulsipher DT, Seidenberg M, Guidotti L, Tuchscherer VN, Morton J, Sheth RD, Hermann B. Thalamofrontal circuitry and executive dysfunction in recent-onset juvenile myoclonic epilepsy. Epilepsia. 2009;50:1210–1219. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1167.2008.01952.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rapoport JL, Giedd JN, Blumenthal J, Hamburger S, Jeffries N, Fernandez T, Nicolson R, Bedwell J, Lenane M, Zijdenbos A, Paus T, Evans A. Progressive cortical change during adolescence in childhood-onset schizophrenia. A longitudinal magnetic resonance imaging study. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1999;56:649–654. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.56.7.649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schreibman Cohen A, Daley M, Siddarth P, Levitt J, Loesch IK, Altshuler L, Ly R, Shields WD, Gurbani S, Caplan R. Amygdala volumes in childhood absence epilepsy. Epilepsy Behav. 16:436–41. doi: 10.1016/j.yebeh.2009.08.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seidenberg M, Kelly KG, Parrish J, Geary E, Dow C, Rutecki P, Hermann B. Ipsilateral and contralateral MRI volumetric abnormalities in chronic unilateral temporal lobe epilepsy and their clinical correlates. Epilepsia. 2005;46:420–430. doi: 10.1111/j.0013-9580.2005.27004.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaw P, Eckstrand K, Sharp W, Blumenthal J, Lerch JP, Greenstein D, Clasen L, Evans A, Giedd J, Rapoport JL. Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder is characterized by a delay in cortical maturation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:19649–19654. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0707741104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaw P, Greenstein D, Lerch J, Clasen L, Lenroot R, Gogtay N, Evans A, Rapoport J, Giedd J. Intellectual ability and cortical development in children and adolescents. Nature. 2006a;440:676–679. doi: 10.1038/nature04513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaw P, Kabani NJ, Lerch JP, Eckstrand K, Lenroot R, Gogtay N, Greenstein D, Clasen L, Evans A, Rapoport JL, Giedd JN, Wise SP. Neurodevelopmental trajectories of the human cerebral cortex. J Neurosci. 2008;28:3586–3594. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5309-07.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaw P, Lerch J, Greenstein D, Sharp W, Clasen L, Evans A, Giedd J, Castellanos FX, Rapoport J. Longitudinal mapping of cortical thickness and clinical outcome in children and adolescents with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2006b;63:540–549. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.63.5.540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shinnar S, Pellock JM. Update on the epidemiology and prognosis of pediatric epilepsy. J Child Neurol. 2002;17(Suppl 1):S4–17. doi: 10.1177/08830738020170010201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Snook L, Paulson LA, Roy D, Phillips L, Beaulieu C. Diffusion tensor imaging of neurodevelopment in children and young adults. Neuroimage. 2005;26:1164–1173. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2005.03.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song SK, Yoshino J, Le TQ, Lin SJ, Sun SW, Cross AH, Armstrong RC. Demyelination increases radial diffusivity in corpus callosum of mouse brain. Neuroimage. 2005;26:132–140. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2005.01.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sowell ER, Peterson BS, Thompson PM, Welcome SE, Henkenius AL, Toga AW. Mapping cortical change across the human life span. Nat Neurosci. 2003;6:309–315. doi: 10.1038/nn1008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sowell ER, Thompson PM, Leonard CM, Welcome SE, Kan E, Toga AW. Longitudinal mapping of cortical thickness and brain growth in normal children. J Neurosci. 2004;24:8223–8231. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1798-04.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Talairach J, Tournoux P. Co-planar stereotaxic atlas of the human brain. Thieme Medical; New York, NY: 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Toga AW, Thompson PM, Sowell ER. Mapping brain maturation. Trends Neurosci. 2006;29:148–159. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2006.01.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wassink TH, Hazlett HC, Epping EA, Arndt S, Dager SR, Schellenberg GD, Dawson G, Piven J. Cerebral cortical gray matter overgrowth and functional variation of the serotonin transporter gene in autism. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2007;64:709–717. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.64.6.709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weber B, Luders E, Faber J, Richter S, Quesada CM, Urbach H, Thompson PM, Toga AW, Elger CE, Helmstaedter C. Distinct regional atrophy in the corpus callosum of patients with temporal lobe epilepsy. Brain. 2007;130:3149–3154. doi: 10.1093/brain/awm186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilke M, Krageloh-Mann I, Holland SK. Global and local development of gray and white matter volume in normal children and adolescents. Exp Brain Res. 2006 doi: 10.1007/s00221-006-0732-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woods RP, Grafton ST, Holmes CJ, Cherry SR, Mazziotta JC. Automated image registration: I. General methods and intrasubject, intramodality validation. J Comput Assist Tomogr. 1998;22:139–152. doi: 10.1097/00004728-199801000-00027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]