Abstract

Background & Aims

Although esophageal motor disorders are associated with chest pain and dysphagia, minimal data support a direct relationship between abnormal motor function and symptoms. This study investigated whether high resolution manometry (HRM) metrics correlate with symptoms.

Methods

Consecutive HRM patients without previous surgery were enrolled. HRM studies included 10 supine liquid, 5 upright liquid, 2 upright viscous, and 2 upright solid swallows. All patients evaluated their esophageal symptom for each upright swallow. Symptoms were graded on a 4 point likert score (0-none, 1-mild, 2-moderate, 3-severe). The individual liquid, viscous or solid upright swallow with the maximal symptom score was selected for analysis in each patient. HRM metrics were compared between groups with and without symptoms during the upright liquid protocol and the provocative protocols separately.

Results

269 patients recorded symptoms during the upright liquid swallows and 72 patients had a swallow symptom score of 1 or greater. 116 of the 269 patients recorded symptoms during viscous or solid swallows. HRM metrics were similar between swallows with and without associated symptoms in the upright, viscous, and solid swallows. No correlation was noted between HRM metrics and symptom scores among swallow types.

Conclusions

Esophageal symptoms are not related to abnormal motor function defined by HRM during liquid, viscous or solid bolus swallows in the upright position. Other factors beyond circular muscle contraction patterns should be explored as possible causes of symptom generation.

INTRODUCTION

The generation of esophageal symptoms during swallowing is a multifactorial phenomenon. Although the pathway of the esophageal perception has been linked to mechanical and chemical receptors in the esophageal wall, vagal and spinal nerves, and the cerebral cortex; the determinants of perception of discomfort in the esophagus are not yet known. Sifrim and colleagues attempted to analyze the correlation between objective esophageal function assessment (with manometry and impedance) and perception of bolus passage in healthy volunteers and GERD patients (1). They were unable to show an agreement between objective measurements of esophageal function and subjective perception of bolus passage. In a similar study, Chen et al obtained comparable results with a similar study design among patients with dysphagia (2). Thus, it appears that the symptom of dysphagia does not correlate with metrics that describe esophageal motor function and bolus transit on impedance.

The primary goal of high-resolution manometry (HRM) is to define esophageal motor function with a greater degree of detail and accuracy than possible with conventional manometry. This has led to the description of clinically relevant phenotypes of esophageal motor dysfunction and the definition of new metrics to assess esophageal function, focused on intrabolus pressure patterns and more comprehensive assessments of contractility and propagation. However, it is unclear whether the detail provided by this new methodology can explain the phenomenon of why measurements of esophageal function during single swallows in the course of standard manometric protocols are not correlated with symptoms in patients with dysphagia. We hypothesized that new metrics utilized in HRM may be better able to elucidate a relationship between symptoms and abnormal motor function during a swallowing protocol. Thus, the aim of the current study was to assess the relationship between HRM metrics and symptom generation during a standard swallow protocol that also included provocative viscous and solid swallows.

METHODS

Subjects and study protocol

Patients referred to the Esophageal Center at Northwestern from September, 2011 to May, 2012 for HRM were prospectively enrolled in the study. Patient’s demographic data including weight, height, body mass index (BMI), main complaint, upper endoscopy findings and past history of surgery were recorded. Patients were excluded if they had a history of esophageal or proximal stomach surgery (fundoplication, Heller myotomy, gastric bypass, lap-band, sleeve gastrectomy), esophagitis (Los Angeles B or higher), esophageal stricture, or findings consistent with eosinophilic esophagitis (rings, narrow caliber).

High resolution manometry was performed in every patient. All the patients were asked to evaluate their level of discomfort after every swallow in the upright position using a 4-point likert scale: 0, none; 1, mild; 2, moderate; 3 severe. They were carefully instructed to distinguish discomfort related to the catheter from the discomfort related to the swallow event in the esophagus. The study protocol was approved by the Northwestern University Institutional Review Board.

Manometric studies were done with the patients in the supine position after at least a 6-h fast. The HRM catheters were 4.2 mm outer diameter solid-state assemblies with 36 circumferential sensors at 1-cm intervals (Given Imaging, Los Angeles, CA). Transducers were calibrated at 0 and 300 mmHg using externally applied pressure. The manometric assemblies were placed transnasally and positioned to record from the hypopharynx to the stomach with at least three intragastric sensors. The manometry was carried out with the patients in the supine position (flat on the back at 0–10 degrees) for ten 5ml liquid swallows, then in the upright position (raised up in a chair at 75–90 degrees) for an additional five 5ml liquid swallows, 2 viscous (apple compote) and 2 solid (marshmallow) swallows chewed for 15 seconds.

Data Analysis

HRM studies were analyzed with Manoview analysis software (Given Imaging, Duluth GA, USA). HRM metrics analyzed including integrated relaxation pressure (IRP), distal contractile integral (DCI), contractile front velocity (CFV), distal latency (DL) and intrabolus pressure (IBP) as previous defined (3). The individual swallow type was categorized and the diagnosis of the esophageal pressure topography (EPT) plots was made according to the most recent Chicago Classification (4).

For the symptom score, the individual upright swallow with the maximal symptom score in each patient was selected; if more than one upright swallow had the maximal score, the first was selected. The same selection method was applied to viscous and solid swallows. This approach was taken to maintain independence of the data set so that each swallow represented an independent observation for comparison.

Statistical analysis

Demographic data including age and BMI were presented as mean ± SD. Non-parametric data were presented as median (interquartile range, IQR). Comparison between groups was performed using student t-test or Mann-Whitney U test, while the comparison among groups was performed using Kruskal-Wallis H test. Chi-square was used to compare percentages among the groups. All P values were two-tailed with the level of significance defined at 0.05.

Results

Demographic characteristics of the study population

From September, 2011 untill May, 2012, 499 patients completed HRM studies. Three hundred and forty-one out of the 499 patients had upright swallow symptom scores marked. Two hundred and sixty-nine out of the 341 patients were eligible for analysis; among them 72 patients had a swallow symptom score ≥1 for at least one swallow. Demographic characteristics are presented in Table 1. The indication for manometry and the diagnosis of supine esophageal manometry were similar between these groups.

Table 1.

Demographic characteristic of the 269 patients with upright swallow symptom score

| With symptoms during swallow (n=72) | Without symptoms during swallow (n=197) | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Male/female | 17/55 | 68/129 | 0.09 |

| Age(years) | 54.9±19.6 | 53.6±16.7 | 0.61 |

| BMI(kg/m2) | 26.9±5.9 | 26.7±7.2 | 0.85 |

| Indication for HRM (n) (%) | 0.42 | ||

| Dysphagia | 30 (41.7%) | 63 (32.0%) | |

| Chest pain | 7 (9.7%) | 19 (9.6%) | |

| GERD | 24 (33.7%) | 71 (36.0%) | |

| Others | 11 (15.3%) | 44 (22.3%) | |

| Supine HRM diagnosis (n) (%) | 0.67 | ||

| Achalasia/EGJ OO | 12 (16.7%) | 27 (13.7%) | |

| Motility Disorders | 5 (6.9%) | 11 (5.6%) | |

| Peristaltic abnormalities | 36 (50.0%) | 92 (46.7%) | |

| Normal | 19 (26.4%) | 67 (34.0%) |

HRM metrics including IRP, DCI, CFV, DL, IBP and the diagnosis based on the 5 upright swallows using Chicago Classification were compared between the groups of patients with and without symptoms during upright swallows (Table 2). There were no differences in the upright HRM metrics between the two groups.

Table 2.

Upright HRM metrics of the 269 patients with upright swallow symptom score ≥1

| With symptoms during swallow (n=72) | Without symptoms during swallow (n=197) | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| HRM metrics (median(IQR)) | |||

| Integrated Relaxation Pressure IRP (mmHg) | 5.6 (3.1, 9.1) | 6.3 (2.8, 10.3) | 0.64 |

| Distal Contractile integral DCI (mmHg-cm-s) | 832 (398, 2008) | 894 (462, 1768) | 0.78 |

| Contractile Front Velocity CFV (mm/s) | 4.5 (3.4, 6.0) | 3.9 (3.2, 5.2) | 0.09 |

| Distal Latency DL (s) | 6.6 (6.0, 7.5) | 6.8 (6.1, 7.6) | 0.29 |

| Intrabolus Pressure IBP (mmHg) | 10.6 (6.4, 17.3) | 10.8 (6.5, 15.4) | 0.86 |

| Upright HRM diagnosis (n) (%) | 0.56 | ||

| Achalasia/EGJ OO | 13 (18.1%) | 34 (16.8%) | |

| Motility Disorders | 2 (2.8%) | 15 (7.6%) | |

| Peristaltic abnormalities | 41(56.9%) | 108 (54.8%) | |

| Normal | 16 (22.2%) | 41 (20.8%) |

HRM metrics in patients with and without symptoms during the upright liquid swallows

The individual upright swallow with maximal symptom score during the upright liquid swallow in each patient was selected for further analysis. Thus, 269 individual swallows were analyzed. Similar to the comparison at the patient level, the individual swallow analysis did not indicate any difference in HRM metrics or swallow type among swallows with different symptom scores (Table 3).

Table 3.

Upright HRM metrics among 269 patients grouped by upright swallow symptom score

| Maximal symptom scores | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 (n=202) | 1 (n=29) | 2 (n=27) | 3 (n=11) | P value | |

| HRM metrics in the individual swallow (median(IQR)) | |||||

| Integrated Relaxation Pressure IRP (mmHg) | 6.9 (3.1, 12.0) | 7.5 (2.4, 9.6) | 5 (2.9, 7.7) | 5.9 (4.8, 12.6) | 0.42 |

| Distal Contractile Integral DCI (mmHg-cm-s) | 818 (96, 2136) | 446 (164,1848) | 868 (18, 1948) | 718 (297, 1246) | 0.89 |

| Contractile Front Velocity CFV (mm/s) | 3.9 (3.2, 5.0) | 4.4 (3.1, 5.8) | 3.4 (2.8, 6.1) | 4.1 (3.6, 5.1) | 0.77 |

| Distal Latency DL (s) | 6.6 (5.9, 7.5) | 6.8 (6.2, 7.4) | 6.6 (5.9, 7.1) | 6.7 (6.2, 7.1) | 0.94 |

| Intrabolus Pressure IBP (mmHg) | 10.8 (6.5, 15.3) | 8.9 (4.4, 15.7) | 6.5 (10.1,15.5) | 12.7 (10.5, 22.3) | 0.42 |

| Upright swallow type (n) (%) | 0.18 | ||||

| Outflow obstruction (IRP>15) and pressurization | 13 (6.4%) | 2 (6.9%) | 0 | 1 (9.1%) | |

| Hypercontractile (DCI>8000) | 1 (0.5%) | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Hypertensive (DCI>5000) | 0 | 1 (3.4%) | 0 | 0 | |

| Premature contraction (DL<4.5S) | 2 (1.0%) | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Rapid contraction (CFV>9cm/s) | 3 (1.5%) | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Failed contraction (Minimal integrity(<3cm)) | 34 (16.8%) | 3 (10.3%) | 7 (25.9%) | 1 (9.1%) | |

| Weak contraction (IBC break>2cm) | 66 (32.7%) | 16 (55.2%) | 11 (40.7%) | 8 (72.7%) | |

| Normal | 83 (50.1%) | 7 (24.1%) | 9 (33.3%) | 1 (9.1%) | |

Subgroup analysis in patients with dysphagia

There were 93 patients with dysphagia among the 269 patients. HRM metrics including IRP, DCI, CFV, DL and IBP were similar between patients with or without dysphagia (p>0.05). Among the 93 dysphagia patients, 27 of them had symptoms during upright liquid swallows and the other 66 patients reported no symptoms. Comparison of the HRM metrics between symptomatic and asymptomatic dysphagia patients showed no difference (p>0.05).

HRM metrics in patients with and without symptoms during the provocative swallows

Among the 269 patients, there were 116 patients who had a symptom score ≥1 recorded during the provocative swallows (viscous or solid). Comparing individual viscous and solid swallows with the maximal symptom score ≥1 and swallows of patients with symptom scores of 0, found no significant difference in the HRM metrics (Table 4).

Table 4.

HRM metrics among 116 patients with vs without provocative swallow symptom score

| Viscous swallow | Solid swallow | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| With symptoms (n=41) | Without symptoms (n=75) | With symptoms (n=40) | Without symptoms (n=76) | |

| HRM metrics in the individual swallow (median(IQR)) | ||||

| Integrated Relaxation Pressure IRP (mmHg) | 5.0 (3.1, 9.2) | 5.1 (2.1, 10.7) | 5.4 (2.6, 10.1) | 5.2 (2.5, 9.7) |

| Distal Contractile Integral DCI (mmHg-cm-s) | 534 (111, 1119) | 695 (224,2199) | 958 (336, 1762) | 779 (328, 1977) |

| Contractile Front Velocity CFV (mm/s) | 3.6 (2.5, 4.7) | 3.3 (2.5,4.2) | 3.8 (2.9, 5.3) | 3.5 (2.5, 5.7) |

| Distal Latency DL (s) | 7.3 (6.6, 8.8) | 7.7 (6.5, 8.7) | 6.6 (5.7, 8.2) | 7.3 (6.2, 8.3) |

| Intrabolus Pressure IBP (mmHg) | 11.5 (7.9,17.8) | 9.4 (4.4,15.8) | 15.6 (10.2, 20.1) | 13.4 (8.6,19.4) |

| Swallow type (n) (%) | ||||

| Outflow obstruction (IRP>15) and pressurization | 2 (4.9%) | 3 (4.0%) | 2 (5.0%) | 3 (3.9%) |

| Hypercontractile (DCI>8000) | 0 | 0 | 1 (2.5%) | 1 (1.3%) |

| Hypertensive (DCI>5000) | 0 | 1 (1.3%) | 0 | 4 (5.2%) |

| Premature contraction (DL<4.5S) | 1 (2.5%) | 1 (1.3%) | 0 | 0 |

| Rapid contraction (CFV>9cm/s) | 2 (4.9%) | 3 (4.0%) | 1 (2.5%) | 4 (5.3%) |

| Failed contraction (Minimal integrity (<3cm)) | 9 (22.0%) | 30 (40.0%) | 6 (15.0%) | 16 (21.1%) |

| Weak contraction (IBC break>2cm) | 18 (43.9%) | 27 (36.0%) | 19 (47.5%) | 26 (34.2%) |

| Normal | 9 (22.0%) | 10 (13.3%) | 11 (27.5%) | 22 (28.9%) |

| Indication for HRM (n) (%) | ||||

| Dysphagia | 14 (34.1%) | 18 (24.0%) | 15 (37.5%) | 17 (22.4%) |

| Chest pain | 1(2.4%) | 13 (17.3%) | 2 (5.0%) | 12 (15.8%) |

| GERD | 18 (43.9%) | 27 (36.0%) | 17 (42.5%) | 29 (38.2%) |

| Other | 8 (19.5%) | 17 (22.7%) | 6 (15.0%) | 18 (23.7%) |

Correlation between upright HRM metrics and symptom score

The correlation between the upright HRM metrics including mean IRP, DCI, CFV, DL and IBP and upright symptom scores were investigated individually. There was no significant correlation between symptom score and individual HRM metric (p>0.05). Among the 269 patients, 37 patients were diagnosed as achalasia or EGJ outflow obstruction. The correlation of the mean IRP of upright swallows and the total upright symptom scores were evaluated in this group and there was no correlation between the mean upright IRP and the upright symptom score (p=0.88). The correlation of HRM metrics from the provocative (viscous and solid) swallows including mean IRP, DCI, CFV, DL, IBP and the symptom scores was also assessed among patients with a symptom score ≥1 during provocative swallows and none correlated (p>0.05).

Predictor of the symptom score

Stepwise multiple regression models were performed in the 269 patients to find the predictors for positive upright symptom scores. Included variables in this model were age, BMI, supine diagnosis, patients’ indication for HRM, and HRM metrics. The analysis found that none of the above factors was predictive of symptoms during upright swallows.

Discussion

Study of the generation of esophageal symptoms is fundamental to informing therapeutic options for patients with dysphagia and esophageal chest pain. Previous studies have tried to elucidate the pathogenesis of these symptoms by assessing the motor and biomechanical properties of the esophageal wall (5). Given that esophageal motor diseases were defined by abnormalities of contractility and deglutitive inhibition, it would be logical that these abnormalities would correlate with symptoms. However, multiple studies have revealed a disconnect between motor patterns and symptoms suggesting that the tools utilized were not sensitive enough or that symptoms were related to phenomena other than the pattern of circular muscle function (1, 2). Although we hypothesized that the improved accuracy of HRM and the new measurements developed for HRM for defining pressure dynamics through the esophagus could help link symptoms with abnormal motor function, our results suggest that there was no correlation between perceived symptoms and esophageal function with the more detailed and accurate manometric system.

The lack of correlation between findings on manometry and symptoms is not surprising as previous data focused on assessing the response to smooth muscle relaxants in nutcracker esophagus and DES had not shown a significant relationship between symptom reduction and reduced contractility (6). Anecdotally, it is rare for patients to describe symptoms during swallows with overt abnormalities during routine manometry. Although this could be rationalized to be related to the artificial scenario of the study protocol or the limited sample of 10–20 swallows, it is still interesting that even severe contractions or overt failure of peristalsis does not elicit some symptom response during the event. These issues stimulated further research into this issue by attempting to correlate symptoms with more specific measures of abnormal bolus transit and function. Lazarescu et al performed a study assessing whether perception of bolus passage was associated with strength of esophageal contraction and completeness of bolus transit in GERD patients and healthy volunteers (1). Their analysis found no correlation between perception of bolus passage and impedance determination of bolus transit or the effectiveness of the contraction. We speculated that the improved accuracy of defining contractility using the peristaltic breaks and the DCI would be more likely to distinguish abnormalities associated with symptoms. However, our results were in line with the findings of Lazarescu et al showing no correlation between HRM parameters and symptoms.

We further speculated that assessing viscous and solid swallows may be associated with a higher yield to determine a symptom correlation with manometric abnormalities and thus, we incorporated viscous and solid swallows into the manometric protocol. Unfortunately, this did not prove useful, as there was no evident relationship between HRM metrics and symptoms during these provocative swallows. This is also in line with a previous study using combined manometry and impedance to assess the relationship between symptoms and abnormalities of esophageal function. Chen et al incorporated viscous swallows into their evaluation of dysphagia correlates during combined manometry and impedance and they also found no correlation between symptoms, bolus clearance on impedance, and esophageal motor abnormalities (2).

The lack of agreement between contractile abnormalities and symptom perception suggests that manometrically defined esophageal motor disorders represent an epiphenomenon that correlates with a pathogenic process directly related to symptom generation. Interestingly, our data did support that the best predictor of symptoms during the protocol was the underlying manometric diagnosis, alternatively suggesting that these abnormalities predispose patients to the development of symptoms. However, the mechanism behind symptom generation is unclear and likely involves multiple factors. Recent studies suggest a potential role of hypersensitivity for esophageal symptom perception (7), potentially related to peripheral mechanisms or abnormalities in central processing of sensory input. Additionally, psychosocial factors, such as anxiety, depression and somatization could also be implicated as these factors can induce a hypervigilance for esophageal functional events.

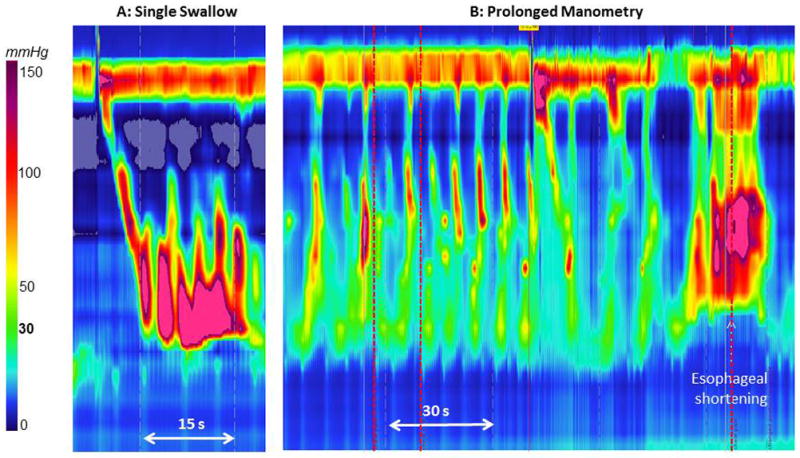

Another explanation for the lack of correlation between motor abnormalities and symptom perception may be related to the fact that we are not evaluating the relevant motor abnormality or have not determined a method to adequately assess the correct parameter. Along this line, there has been substantial interest in the esophageal longitudinal muscle in the generation of esophageal symptoms and the San Diego group have provided provocative evidence to support a role of longitudinal muscle contraction in the generation of heartburn and chest pain (8). This does provide a biologically plausible mechanism for symptom generation and more attention should be focused on this aspect of esophageal contractility. Figure 1 represents an example of a patient diagnosed with jackhammer esophagus who exhibits chest pain with retrograde spastic appearing contractions and an episode of substantial esophageal shortening associated with hypercontractility. Of note, the patient did not report any symptoms during the standard HRM study and there was no evidence of shortening or retrograde contraction during the 10-swallow test protocol. This suggests that the jackhammer pattern may be a surrogate for a secondary abnormality that is directly responsible for symptom generation.

Figure 1.

Example of a symptomatic swallow in a patient diagnosed with jackhammer esophagus who reported chest pain during this swallow with retrograde spastic appearing contraction and substantial esophageal shortening associated with hypercontractility.

Similarly, esophageal manometry does not provide an adequate assessment of the mechanical properties of the esophageal wall and thus, other analysis paradigms or techniques may be helpful. Our data suggested that patients who developed symptoms during the viscous and solid swallows were more likely to have elevated IBP suggesting that esophageal strain may be important in symptom generation. It is possible that new methodology utilizing combined impedance and manometry (AIM) to assess intrabolus pressure may help further clarify the role of elevated intrabolus pressure in dysphagia. Alternatively, a completely new technology, such as impedance planimetry combined with pressure evaluation may also help to better distinguish the relationship between esophageal body mechanics and symptoms.

There are limitations in the current study. Firstly, the symptom score used to evaluate the esophageal symptom has not been validated and might not reflect the patient’s symptoms severity accurately. However, the score should have been able to distinguish some level of discomfort and therefore, the data are likely real. Secondly, it is important to consider that the catheter could have influenced symptom reporting, as this may inadvertently shift the patients’ attention toward the discomfort of the catheter and away from esophageal discomfort. Unfortunately, this cannot be avoided with this technology. Finally, the small number of swallows may be viewed as a small sample size to correlate with the entire number of swallows occurring throughout the day. However, we were looking at a direct correlation between motor abnormalities and symptoms and the fact that significant motor events were not associated with symptoms suggests that there is no correlation between motor function and symptoms.

In conclusion, esophageal symptoms are not related to abnormal motor function defined by HRM during liquid, viscous or solid bolus swallows in the upright position. The role of visceral hypersensitivity, hypervigilance, and psychosocial factors should be explored as potential primary generators and modifiers of symptoms. Additionally, new techniques should also be explored that may improve our ability to assess longitudinal muscle function and study the mechanical components of bolus transit.

Study highlights.

What is the current knowledge?

Esophageal motor disorders are associated with chest pain and dysphagia.

There are little data to support a direct relationship between abnormal motor function and the generation of symptoms.

What is new here?

Esophageal symptoms are not related to abnormal motor function defined by high-resolution manometry during various swallow protocols.

Other factors beyond circular muscle contraction patterns should be explored as possible causes of symptom generation.

Acknowledgments

Financial support: This work was supported by R01 DK079902 (JEP) and R01 DK56033 (PJK) from the Public Health Service.

Footnotes

Guarantor of the article: John E. Pandolfino M.D.

Conflict of interest: John E. Pandolfino [Given imaging (consulting, educational)], Sabine Roman [Given imaging (consulting); No other conflicts for remaining authors (YX, PJK, FN, ZL)

Specific author contributions: Study concept, acquisition of data, analysis, drafting, study supervision: Yinglian Xiao; Study concept, acquisition of data, analysis, drafting, study supervision, finalizing the manuscript: Peter J. Kahrilas; Acquisition of data and analysis, finalizing the manuscript: Frédéric Nicodème and Sabine Roman; Technical support: Zhiyue Lin; Study concept, acquisition of data, analysis, drafting, study supervision, finalizing the manuscript: John E. Pandolfino.

References

- 1.Lazarescu A, Karamanolis G, Aprile L, De Oliveira RB, Dantas R, Sifrim D. Perception of dysphagia: lack of correlation with objective measurements of esophageal function. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2010;22(12):1292–7. e336–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2982.2010.01578.x. Epub 2010/08/20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chen CL, Yi CH. Clinical correlates of dysphagia to oesophageal dysmotility: studies using combined manometry and impedance. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2008;20(6):611–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2982.2008.01086.x. Epub 2008/02/27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pandolfino JE, Ghosh SK, Rice J, Clarke JO, Kwiatek MA, Kahrilas PJ. Classifying esophageal motility by pressure topography characteristics: a study of 400 patients and 75 controls. Am J Gastroenterol. 2008;103(1):27–37. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2007.01532.x. Epub 2007/09/29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bredenoord AJ, Kahrilas PJ, Pandolfino JE, Schwizer W, Smout AJPM. Chicago classification criteria of esophageal motility disorders defined in high resolution esophageal pressure topography. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2012;24(S1):57–65. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2982.2011.01834.x. Epub 16 Jan 2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Barlow JD, Gregersen H, Thompson DG. Identification of the biomechanical factors associated with the perception of distension in the human esophagus. Am J Physiol. 2002;282(4):G683–9. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00134.2001. Epub 2002/03/19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pimentel M, Chow EJ, Lin HC. Peppermint oil improves the manometric findings in diffuse esophageal spasm. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2001;33(1):5. doi: 10.1097/00004836-200107000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nasr I, Attaluri A, Hashmi S, Gregersen H, Rao SS. Investigation of esophageal sensation and biomechanical properties in functional chest pain. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2010;22(5):520–6. e116. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2982.2009.01451.x. Epub 2010/01/14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hong SJ, Bhargava V, Jiang Y, Denboer D, Mittal RK. A unique esophageal motor pattern that involves longitudinal muscles is responsible for emptying in achalasia esophagus. Gastroenterology. 2010;139(1):102–11. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2010.03.058. Epub 2010/04/13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]