Abstract

Context:

Development of novel strategies in the treatment of advanced thyroid cancer are needed. Our laboratory has previously identified a role for nuclear factor κB (NF-κB) signaling in human thyroid cancer cell growth, survival, and invasion.

Objective:

Our goal was to establish the role of NF-κB signaling on thyroid cancer growth and metastases in vivo and to begin to dissect mechanisms regulating this effect.

Setting and Design:

We examined tumor formation of five thyroid cancer cell lines in an in vivo model of thyroid cancer and observed tumor establishment in two of the cell lines (8505C and BCPAP).

Results:

Inhibition of NF-κB signaling by overexpression of a dominant-negative IκBα (mIκBα) significantly inhibited thyroid tumor growth in tumors derived from both cell lines. Further studies in an experimental metastasis model demonstrated that NF-κB inhibition impaired growth of tumor metastasis and prolonged mouse survival. Proliferation (mitotic index) was decreased in 8505C tumors, but not in BCPAP tumors, while in vitro angiogenesis and in vivo tumor vascularity were significantly inhibited by mIkBα only in the BCPAP cells. Cytokine antibody array analysis demonstrated that IL-8 secretion was blocked by mIκBα expression. Interestingly, basal NF-κB activity and IL-8 levels were significantly higher in the two tumorigenic cell lines compared with the nontumorigenic lines. Furthermore, IL-8 transcript levels were elevated in high-risk human tumors, suggesting that NF-κB and IL-8 are associated with more aggressive tumor behavior.

Conclusions:

These studies suggest that NF-κB signaling is a key regulator of angiogenesis and growth of primary and metastatic thyroid cancer, and that IL-8 may be an important downstream mediator of NF-κB signaling in advanced thyroid cancer growth and progression.

Asignificant minority of thyroid cancers are unresponsive to standard therapies, and nearly 2000 patients die each year in the United States from advanced thyroid cancer, supporting the need for new directed therapies (1, 2). Our laboratory has focused on the role of nuclear factor κB (NF-κB) in advanced thyroid cancer, given its function as a critical mediator in many of the hallmarks of cancer (3). We have previously demonstrated a role for NF-κB in thyroid cancer cell proliferation, survival, and invasion in advanced thyroid cancer cell lines (4). Visconti (5) was the first to show high NF-κB activity in thyroid cancer cell lines and that inhibition of NF-κB signaling reduced colony formation. Pacifico (6) demonstrated nuclear p65 staining in thyroid cancer tissue compared with normal thyroid tissue as well as more intense staining in anaplastic thyroid cancer, suggesting that the NF-κB pathway is important in tumor aggressiveness. Vasko (7) confirmed this observation using RNA microarray to show that the NF-κB pathway was increased in the invasive front of papillary thyroid cancer (PTC) tissue. Although the effect of NF-κB inhibition on these aspects of tumor biology remains important, targeting of other NF-κB-regulated mechanisms, such as its role in tumor angiogenesis, may be a more effective therapeutic strategy. Furthermore, the role of the NF-κB-regulated cytokine, IL-8, is poorly understood in thyroid cancer biology.

In this study, we examined the effect of NF-κB inhibition on thyroid tumor growth using in vivo orthotopic and metastatic mouse models of advanced thyroid cancer expressing a selective genetic inhibitor of NF-κB (mIκBα). We have also begun to dissect mechanisms by which NF-κB signaling in thyroid cancer cells interacts with the microenvironment to cause growth and metastases in advanced thyroid cancer.

Materials and Methods

Cell culture

The BCPAP (8), SW1736 (9), C643 (10), TPC1 (11), and 8505C (12) thyroid cancer cell lines were kindly provided and maintained as previously described (4). The BOSC cell line, kindly provided by Dr. H. Ford (University of Colorado School of Medicine) was maintained for 3–5 passages at 37 C and 5% CO2 in DMEM (Invitrogen) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) (Hyclone) and 5 mg/mL L-glutamine (Gemini). The HUVEC cell line was maintained for 10–20 passages at 37 C and 5% CO2 in Endothelial Growth Medium Complete Medium (Lonza). Thyroid cancer cell lines were routinely profiled by Short Tandem Repeat analysis at the University of Colorado Cancer Center (UCCC) DNA Sequencing and Analysis Core and are consistent with our previously published profiles (13).

Measurement of secreted IL-8 levels and angiogenesis antibody array

Thyroid cancer cells (5.0 × 105) were transduced with either Ad-GFP or Ad-mIκBα as described previously (4). On the following day, the media was replaced with fresh Roswell Park Memorial Institute (RPMI) (0.1% FBS). Twenty-four hours later, secreted IL-8 levels were assessed with the Human CXCL8/IL-8 Quantikine ELISA Kit (R&D Systems) according to the manufacturer's protocol. For the antibody arrays, conditioned media was collected from transduced SW1736 cells as described above, and levels of secreted proteins were assessed using a human angiogenesis antibody array (R&D Systems) according to the manufacturer's protocol. Densitometry was then performed to obtain a relative measure of secreted protein differences.

HUVEC tubule formation assays

Thyroid cancer cells (5.0 × 105) were transduced with either Ad-GFP or Ad-mIκBα as described (4). On the following day, the media was replaced with fresh Endothelial Basal Medium (Lonza) supplemented with 0.5% FBS. Twenty-four hours later, the media was collected and centrifuged at 1000 rpm for 5 minutes to pellet remnant cells and debris. HUVECs (4.0 × 104) were then resuspended in 1 mL conditioned media, plated in 24-well dishes coated with 150 μL Matrigel (phenol-red free; BD Biosciences, 356237), and incubated at 37 C with 5% CO2 for 12 hours. Three images of each well under ×100 magnification were then captured with a Zeiss microscope and analyzed using AxioVision software as described previously (14).

Generation of stable cell lines

pQCXIP-mIκBα

The mutant IκB plasmid pCMX IκB alpha M (IκBαM) (Addgene plasmid 12329) was kindly provided by Dr. I. Verma (The Salk Institute for Biological Studies). The mIκBα cDNA was isolated by EcoRI digestion and cloned into EcoRI-digested pQCXIP expression vector to generate the pQCXIP-mIκBα retroviral expression vector. Generation of the appropriate directional construct was confirmed by sequencing at the UCCC DNA Sequencing and Analysis Core.

Virus was produced by transfection (Effectene; Qiagen) of BOSC cells with pQCXIP-mIκBα or pQCXIP in combination with pCL-Ampho, according to manufacturer's recommendations. The transfection mixture was combined with BOSC medium and added to BOSC cells. Media containing viral particles was collected 48, 72, and 96 hours post-transfection, and each collection was aliquoted and snap-frozen.

The 8505C and BCPAP cell lines were virally transduced to generate the 8505C-vector, 8505C-mIκBα, BCPAP-vector, and BCPAP-mIκBα sublines. Selection of cells stably expressing the vector control or mIκBα constructs was initiated the following day by treating cells with 1 μg/mL puromycin (Sigma) for 7 days. Cells were then cultured for 2 weeks prior to injecting into mice.

Xenograft orthotopic and metastatic mouse models of thyroid cancer

Cells were transfected (Lipofectamine 2000; Invitrogen) with the vector pEGFP-N1-luciferase (Clontech). G418 selection was initiated 24 hours post-transfection in the BCPAP and 8505C cell lines with 0.25 mg/mL and 0.5 mg/mL G418, respectively. GFP-positive cells were pooled following fluorescence-activated cell sorting analysis at the UCCC Flow Cytometry Core after 7 days of G418 selection.

All animal studies (orthotopic and metastatic) were carried out under approval and supervision of the University of Colorado Animal Care and Use Committee.

Athymic nude mice (Harlan; 25–30 g; 5–7 weeks old) were used in the orthotopic model. Under Avertin anesthesia, surgery was performed to exopse the thyroid and 500,000 cells suspended in 5 μL PBS were delivered via injection with a 25 μL Hamilton syringe as previously described (15–18). Tumor establishment and progression were monitored at days 7, 14, 21, and 28 by assessing luciferase bioluminescence with the IVIS 200 system (Caliper) in the UCCC Small Animal Imaging Core. D-Luciferin (1.5 mg; Xenogen) was delivered by ip injection in a 200-μL volume to each mouse. Five minutes later, isofluorane was administered as an anesthetic for the duration of 5 minutes, and images were captured. Tumor bioluminescence was quantified with Living Image Software (Caliper). After 4 weeks, the mice were killed, and tumors, lungs, and lymph nodes were collected. Final tumor volume was assessed by measurement with calipers using the following formula: tumor volume = (length × width × height)/0.5236.

Male athymic nude mice (Harlan; 25 g; 5 weeks old) received D-luciferin (3 mg) via ip injection and were anesthetized using isofluorane after 5 minutes. 105 cells (BCPAP-vector and BCPAP-mIκBα sublines transfected with pEGFP-N1-luciferase as above) in 100 μL PBS were injected into the left ventricle (LV) of nude mice using a 26-gauge needle, as previously described (18, 19). Metastatic progression was monitored weekly by IVIS imaging.

The study was designed as a survival study. Mice were removed from the study due to death or morbid endpoints (weight loss >15%, decreased mobility, inability to eat or drink adequately, or inability to ambulate properly).

Tumor processing and histological analysis

Dissected tumor samples from human thyroid cancer cell lines in the mouse xenograft models were fixed in 10% buffered-formalin. Samples were embedded in paraffin by the UCCC Pathology Core. The sections were then stained with hematoxylin and eosin according to a standardized protocol. The mitotic index of five tumors in each group was determined by counting the number of mitotic figures in 10 fields of view under ×500 magnification of H&E stained sections. The percent of tumor necrosis of five tumors in each group was scored. The microvessel density of five tumors in each group was determined by counting the number of vessel lumens in 5 fields of view under ×500 magnification of H&E stained sections. Each parameter was assessed by blinded pathologist.

Measurement of IL-8 mRNA levels in cells and tissue

Thyroid cancer cells were transduced with either Ad-GFP (as an appropriate control) or Ad-mIκBα. Total RNA was isolated from the cells after 48 hours using the PerfectPure RNA Cultured Cell Kit (5 Prime) as per the manufacturer's protocol. Snap-frozen tumor RNA was collected by homogenization in TriReagent (Sigma) according to manufacturer's specifications. The aqueous layer containing tumor RNA was then further purified using the RNA Easy purification system (Qiagen) according to manufacturer's protocol.

Snap-frozen human thyroid tissue was obtained from consented patients (18 PTC tumors, 11 from patients at high risk for recurrence and 7 from patients with low risk for recurrence) prior to surgery according to the Internal Review Board–approved Thyroid Tumor Bank Protocol (protocol No. 07–0562). RNA was prepared using the PerfectPure RNA Tissue Kit (5 Prime) according to manufacturer's instructions. RNA from three samples of tall-cell thyroid carcinoma were also generously provided by Dr Herbert Chen (University of Wisconsin).

The mRNA levels of IL-8 were measured by real-time quantitative reverse transcription PCR using ABI PRISM 7700 with the following primers: IL-8; Sense-GCCGTGGC TCTCTTGGC; Antisense-GCACTCCTTGGCAAAACTGC; Probe-TCCTGAT TTCTGCAGCTCTGTGTGAAGG.

Amplification reactions and thermal cycling conditions were optimized for each primer-probe set and carried out by the University of Colorado Cancer Center Gene Expression Core. A standard curve was generated using the fluorescent data from the 10-fold serial dilutions of control RNA. This was then used to calculate the transcripts levels of IL-8 in the RNA samples. Quantities of the IL-8 mRNA in samples were normalized to the corresponding 18S rRNA (PE ABI, P/N 4308310).

Comparative IL-8 mRNA expression in papillary vs. anaplastic thyroid cancer tissue were obtained from published Affymetrix HG_U133A microarray set (20), GEO accession: GSE27155, probe set 202859_x_at) that includes 51 papillary carcinoma and four anaplastic carcinoma samples.

IL-8 promoter activity

IL-8 promoter regulation was investigated using dual-luciferase reporter assay. IL-8 promoter firefly luciferase reporter construct (based on pGL3-Basic vector, Promega) and internal control (pBA-RL) containing a full-length renilla luciferase gene under the control of a human β-actin promoter were kindly provided by Dr Xie (21). Both constructs were cotransfected into BCPAP cells (∼70% confluence) using X-tremeGene 9 DNA transfection reagent (Roche Diagnostics) at a DNA ratio of 3:1. After 24 hours' incubation, firefly and renilla luciferase activities were measured using Dual-Reporter Luciferase Assay System (Promega). Cells were treated with either vehicle (phosphate buffered saline) or TNF-alpha (TNFα) at 10 ng/mL.

Statistical analysis

For in vitro studies, statistical significance between groups was determined using the two-tailed t test (GraphPad Prism) unless indicated otherwise in figure legend. Statistical significance between groups in in vivo studies was calculated using the Mann-Whitney U test (GraphPad Prism) unless indicated otherwise in figure legend.

Results

Establishment of an in vivo orthotopic nude mouse model of thyroid cancer

Two PTC and three ATC cell lines characterized by the presence of activating mutations in the mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) pathway (Supplemental Table 1) were injected into the right thyroid lobe of the mouse, and tumor formation was assessed weekly for up to 16 weeks. To confirm the in vivo tumorigenicity of our thyroid cancer cell lines, we attempted to establish thyroid tumors in at least eight mice with each cell line. Interestingly, only the BCPAP (11/12) and 8505C (12/12) cell lines demonstrated robust tumor formation (Supplemental Table 1). Both of these cell lines have the BRAFV600E mutation. SW1736 (BRAF V600E) and TPC1 (RET/PTC1) cells did not form tumors in mice. C643 (HRasG13R) cells formed tumors in only 1 of 8 mice.

Effect of NF-κB inhibition on in vivo tumor growth

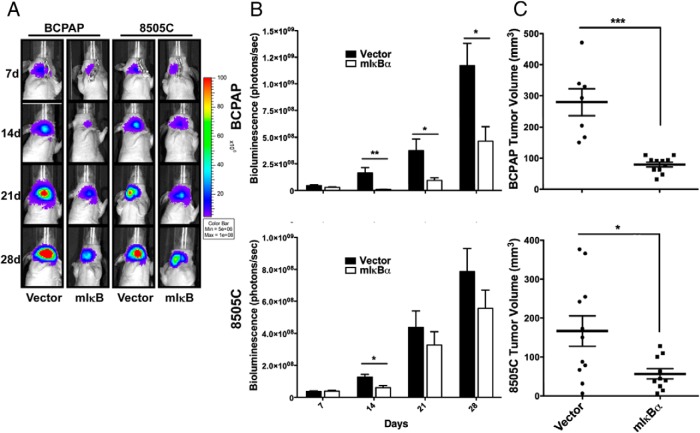

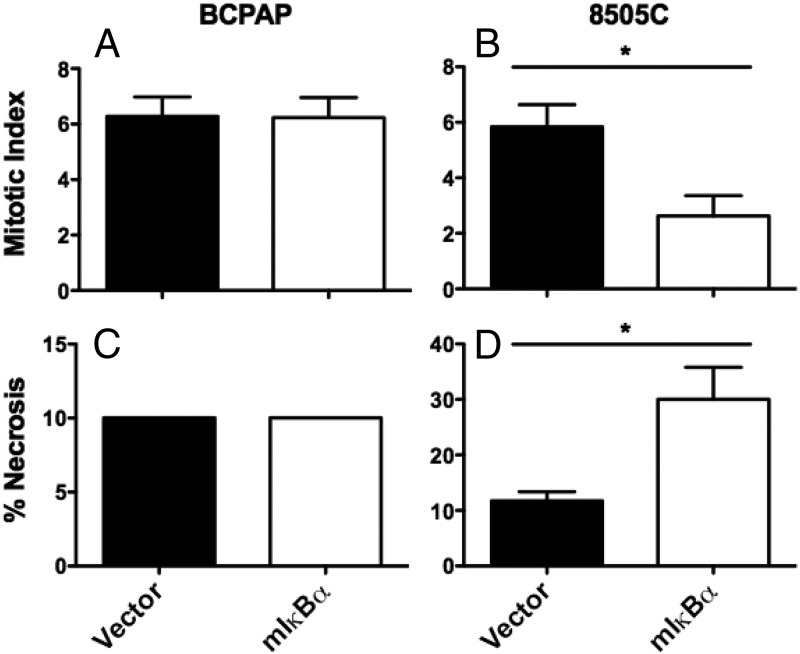

We next established pools of BCPAP and 8505C cell lines stably expressing either vector control or mIκBα to inhibit endogenous NF-κB signaling. NF-κB inhibition resulted in a significant decrease in tumor growth of the BCPAP cell line, as determined by both weekly measurement of in vivo bioluminescence and final tumor volume [vector-control (279.5 mm3) vs. mIκBα (79.2 mm3); P = .0006] (Figure 1). NF-κB inhibition also resulted in a significant decrease in final tumor volume of the 8505C cell line [vector-control (166.7 mm3) vs. mIκBα (56.8 mm3); P = .0411] (Figure 1, B and C), but no significant change in in vivo biolumiescence. Histological examination revealed that NF-κB inhibition had no effect on necrosis or mitotic index in BCPAP tumors (Figure 2, A and C). In contrast, 8505C-mIκBα tumors demonstrated a 2-fold decrease in mitotic index as well as increased necrosis when compared with 8505C control tumors (Figure 2, B and D). These findings are consistent with our previous studies, in which NF-κB-dependent regulation of in vitro proliferation was observed only in 8505C cells (4).

Figure 1.

NF-κB inhibition attenuates orthotopic tumor growth by BCPAP and 8505C cell lines. 500,000 BCPAP (n = 12) and 8505C (n = 12) cells stably expressing a GFP-luciferase fusion protein and either vector-control or mIκBα were injected into the right thyroid lobe of an athymic nude mouse. A) Tumor establishment and progression was monitored weekly via bioluminescent imaging (IVIS) for 4 weeks, and representative images are shown here. B) Bioluminescent imaging (IVIS) was quantified using Living Image Software (Caliper Life Sciences). Data are represented as photons/s, and mean ± SEM is reported. [P < .05 (*); P < .01 (**); P < .001 (***)]. C) Tumors were collected after 4 weeks and measured in three dimensions with calipers. Final tumor volume was calculated with the following equation: volume (mm3) = L × W × D × 0.5236. Mean ± SEM is reported. [P < .05 (*); P < .01 (**); P < .001 (***)].

Figure 2.

Mutant IκBα expression inhibits proliferation and induces necrosis in 8505C tumors but not in BCPAP tumors. A,B) The mitotic index of five tumors in each group was determined by counting the number of mitotic figures in 10 fields of view under ×500 magnification. Data are reported as mitotic index and presented as the mean ± SEM. C,D) The percent of tumor necrosis of five tumors in each group was scored. Data are reported as percent necrosis and presented as the mean ± SEM. [P < .05 (*)].

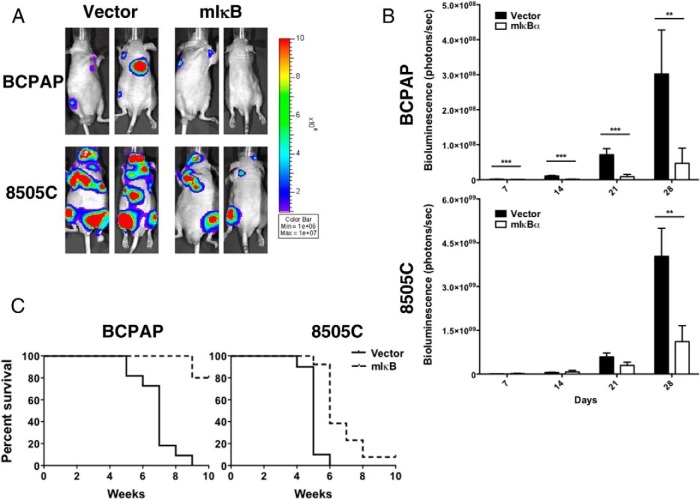

To determine whether NF-κB inhibition resulted in impaired tumor metastasis, we used an experimental metastasis model in which tumor cells (BCPAP and 8505c) expressing either control vector or mIκB were injected into the LV of the nude mouse heart, as previously demonstrated by our laboratory (18).

Consistent with our in vivo orthotopic tumor data, Figure 3 demonstrates an 85% and 72% reduction in metastatic burden in BCPAP and 8505C cells expressing mIκB, respectively, over the course of 4 weeks. Moreover, mouse survival was significantly improved by NF-κB inhibition in the BCPAP and 8505C mice (Figure 3C). Eighty percent of mice injected with BCPAP cells expressing mIκB survived to at least 10 weeks, compared with vector-expressing cells in which 50% died by 7 weeks and all mice had died by 9 weeks. Inhibition of NF-κB signaling improved 50% survival in mice harboring the 8505C cells from 5 to 6 weeks (P < .0001).

Figure 3.

NF-κB inhibition attenuates tumor mestasis by BCPAP and 8505C cells In an experimental metastasis model. 500,000 BCPAP and 8505C cells stably expressing a GFP-luciferase fusion protein and either vector-control or mIκBα were injected into the LV of an athymic nude mouse. A) Metastasis establishment and progression was monitored weekly via bioluminescent imaging (IVIS) for 4 weeks, and representative images are shown here. B) Bioluminescent imaging (IVIS) was quantified using Living Image Software (Caliper Life Sciences). Data are represented as photons/s, and Mean ± SEM. is reported. [P < .05 (*); P < .01 (**); P < .001 (***)]. C) Kaplan-Meier survival plots (BCPAP P < .0001; 8505C P < .0001)

Effect of NF-κB inhibition in an in vitro model of angiogenesis

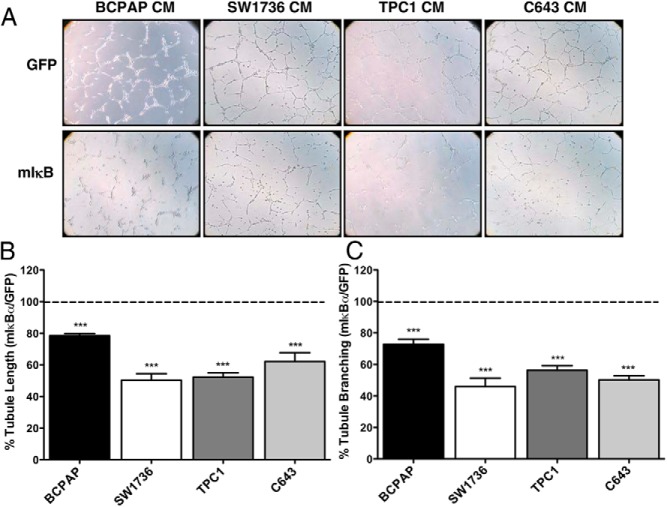

Our previous studies have shown that in vitro NF-κB inhibition in the BCPAP cell line had no effect on proliferation or survival (4), yet we observed a significant inhibition of in vivo tumor growth (Figures 1 and 2). We therefore predicted that NF-κB may regulate angiogenesis in this tumor model. To test this hypothesis, we used an in vitro angiogenesis assay with conditioned media from thyroid cancer cells (BCPAP, SW1736, TPC1, C643) transduced with either control Ad-GFP or Ad-mIκBα. The 8505C cell line was not used in these studies because the cell cycle arrest observed in vitro following NF-κB inhibition led to such reduced cell numbers that assessment of secreted proteins would be limited (4, 14, 22). Significant inhibition of HUVEC tubule formation was observed with NF-κB inhibition in each of the four thyroid cancer cell lines tested (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

NF-κB inhibition in thyroid cancer cells decreases tubule formation by endothelial cells in an in vitro model of angiogenesis. Conditioned media (CM) was prepared from cells (BCPAP, SW1736, TPC1, and C643) that were transduced with either Ad-GFP or Ad-mIκBα for 48 hours prior to collection. HUVEC cells were then resuspended in CM, and A) images were acquired 8 hours after application of the cell suspension to Matrigel-coated 24-well plates. B) Total tubule length was quantified using Axiovision Software (Zeiss), and C) branch points were counted in three ×100 fields/well. Data are represented as B) percent tubule branching or C) percent tubule length in response to CM from mIκBα-expressing cells compared with GFP-expressing cells. Tubule formation observed in response to CM from GFP-expressing cells is normalized to 100%. Mean ± SEM of two independent experiments performed in duplicate is reported. [P < .001 (***)].

NF-κB-dependent modulation of cytokines involved in regulating angiogenesis

Regulation of angiogenesis by cancer cells is mediated by the secretion of soluble factors. To investigate the regulation of these secreted factors by NF-κB, we collected conditioned media from SW1736 cells (largest suppression of angiogenesis by mIkBα) transduced with either control Ad-GFP or Ad-mIκBα and assessed the levels of these factors using a human angiogenesis antibody array (R&D). Control vector SW1736 cells secreted nine measurable angiogenesis/cytokine proteins out of 55 possible proteins in this antibody array (Supplemental Table 2 and Figure 5A). Only thrombospondin-1 (TSP-1), IL-8, dipeptidyl peptidase-4 (DPPIV), and insulin-like growth factor binding protein (IGFBP)-3 proteins levels were affected by NF-κB inhibition. IL-8, a potent chemoattractant and angiogenic stimulant, demonstrated the highest degree of suppression by inhibiting NF-κB signaling (Figure 5A). Interestingly, vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) was secreted into the conditioned media of SW1736 cells, but was not inhibited by mIkBα blockade of NFκB signaling (Supplemental Table 2 and Figure 5A). MMP-8, PAI-1, TIMP-1, and uPA were also secreted by the SW-1736 cells, but levels were unaffected by mIkBα (Supplemental Table 2).

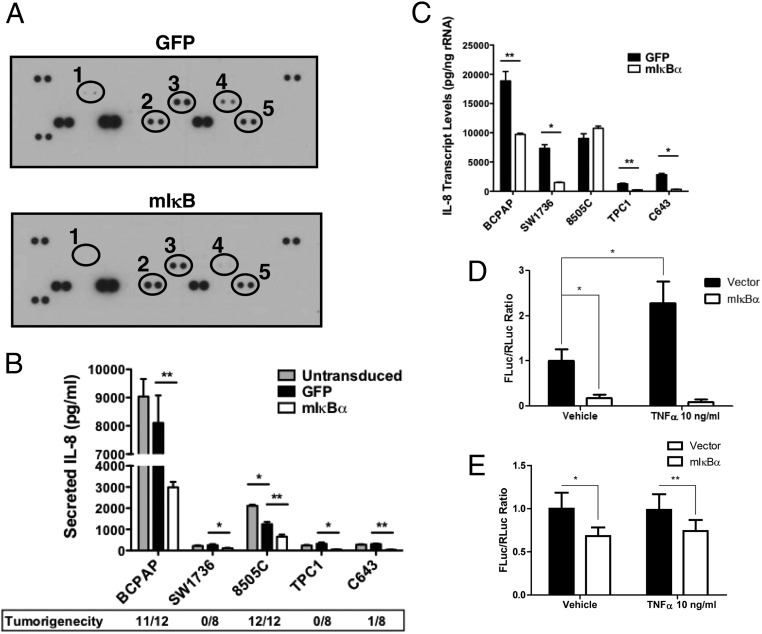

Figure 5.

An analysis of secreted angiogenesis-regulating factor demonstrates that secreted IL-8 levels are decreased in response to NF-κB inhibition. A) Conditioned media (CM) was prepared from SW1736 cells that were transduced with either Ad-GFP or Ad-mIκBα for 48 hours prior to collection. Secreted factors were assessed in conditioned media from GFP- and mIκBα-expressing cells with a human angiogenesis antibody array (R&D Systems). Densitometry was performed to quantify fold change. 1) DPPIV (−3.4-fold); 2) Thrombospondin-1 (2.2-fold); 3) IGFBP-3 (-2.3-fold); 4) IL-8 (−9.2-fold); and 5) VEGF (no change). B) Conditioned media was collected from untransduced, Ad-GFP, and Ad-mIκB-transduced cells (BCPAP, SW1736, 8505C, TPC1, and C643) 48 hours after transduction. IL-8 levels were then determined via ELISA (R&D Systems). Data are represented as pg/mL, and Mean ± SEM is reported. [P < .05 (*); P < .01 (**); P < .001 (***)]. C) Quantitative real-time PCR was performed to analyze the regulation of IL-8 expression in response to mIκBα expression. BCPAP, SW1736, 8505C, TPC1, and C643 cells were transduced 48 hours prior to harvesting total RNA. Data are represented as picograms target mRNA corrected for nanograms rRNA (internal standard). Mean ± SEM of three independent experiments performed in duplicate is reported. [P < .05 (*); P < .01 (**); P < .001 (***)]. D,E) IL-8 promoter regulation by NF-κB. D) BCPAP cells and E) 8505C cells were cotransfected with IL-8 promoter firefly luciferase reporter construct and internal control expressing renilla luciferase. Data are presented as normalized firefly (FLuc)/renilla (RLuc) ratio (Mean ± SD). P < .001 (*), P < .01 (**)

NF-κB-dependent regulation of IL-8

To determine whether regulation of IL-8 by NF-κB represented a broader phenomenon in thyroid cancer cell lines, we analyzed IL-8-secreted protein and mRNA levels by ELISA (Figure 5B) and quantitative RT-PCR (Figure 5C), respectively, in our panel of five cell lines. The BCPAP and 8505C cell lines secreted the highest levels of IL-8 (∼10,000 and ∼2000 pg/mL, respectively), whereas the cell lines that did not establish tumors in mice secreted significantly lower levels (∼250 pg/mL) (Figure 5B). This finding is intriguing given the direct correlation between high IL-8 secretion, NF-κB activity, and tumorigenicity (Figure 5B, Supplemental Table 1).

Secreted IL-8 levels were reduced by at least 2-fold in response to NF-κB inhibition in the BCPAP, SW1736, TPC1, and C643 cell lines (Figure 5B). Our studies further showed a strong correlation between secreted IL-8 levels and mRNA expression (Figure 5, B and C). High mRNA levels (∼19,000 pg/ng rRNA) were seen in the BCPAP cell line whereas moderate levels (∼7,000–9,000 pg/ng rRNA) were seen in the 8505C and SW1736 cell lines. The TPC1 and C643 cell lines exhibited the lowest transcript levels (∼1,250–2800 pg/ng rRNA). IL-8 mRNA levels were decreased by at least 2-fold in response to NF-κB inhibition in all cell lines, with the exception of the 8505C cell line (Figure 5C). The lack of NF-κB-dependent IL-8 mRNA levels in the 8505C cell line suggests that the decrease in secreted levels of IL-8 observed in the mIκBα-expressing cells is likely an artifact of the proliferative arrest observed in this cell line in response to NF-κB inhibition (4).

In order to determine whether inhibition of IL-8 mRNA by mIκBα occurs at the transcriptional level, BCPAP cells were transfected with a IL-8 promoter–firefly luciferase reporter construct (21). mIκBα inhibited IL-8 basal promoter activity and blunted TNFα-stimulated promoter activity in BCPAP cells (Figure 5D), indicating that regulation of IL-8 by NFκB signaling occurs, at least in part, through regulation of gene transcription. mIkBα has less of an effect on IL-8 promoter activity in the 8505C cells compared with the BCPAP cells, which is consistent with the mRNA data (Figure 5C).

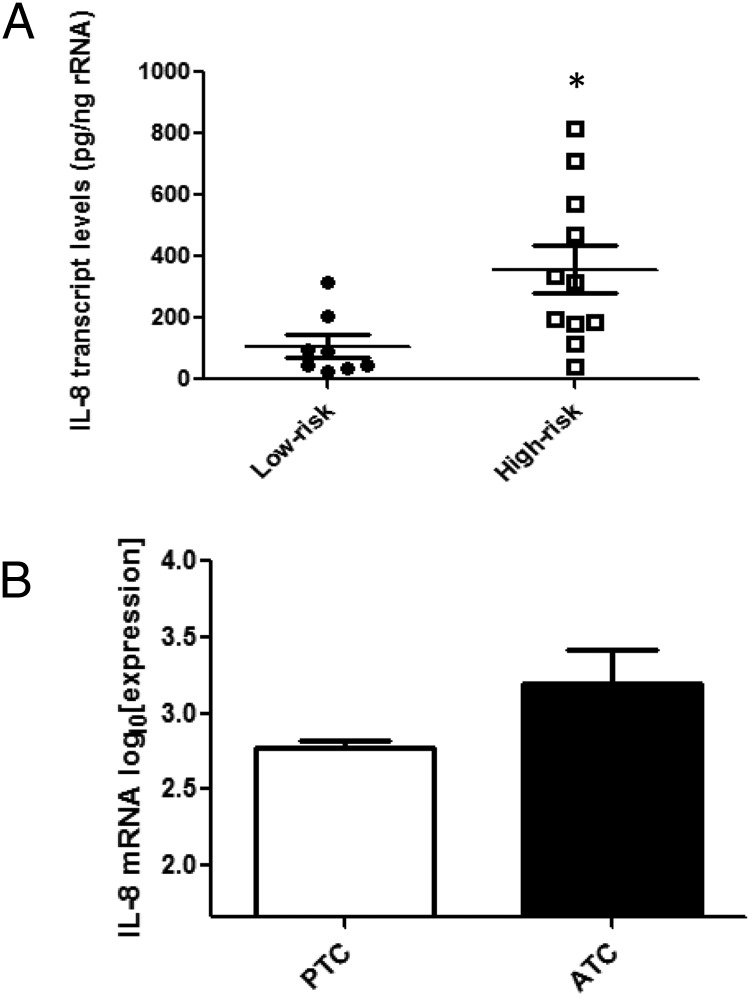

IL-8 expression in human tumor samples

We analyzed IL-8 expression levels in high-risk and low-risk human PTC tumors by quantitative RT-PCR. High-risk tumors were characterized by aggressive features, including extrathyroidal invasion and extensive (>50%) lymph node metastases; three of these tumors were tall-cell variant. Interestingly, high-risk tumors demonstrated IL-8 mRNA levels that were 6-fold higher than those found in low-risk tumors, adding correlative evidence for a potential role of NF-κB-IL8 signaling in human thyroid cancer aggressiveness and progression (Figure 6A). We attempted to correlate serum IL8 levels with tumor aggressiveness in these patients, but serum IL8 was very low in most patients and did not correlate with tumor aggressiveness, suggesting effects at a local tumor microenvironment level (data not shown). In order to compare PTC with ATC, we analyzed microarray data from Giordano and colleagues (20). There was a trend toward higher IL-8 mRNA levels in ATC compared with PTC, but this did not reach statistical significance (Figure 6B, P = .052). The number of ATC samples was small (n = 4).

Figure 6.

Intratumoral IL-8 mRNA levels are higher in more aggressive thyroid cancer. A) Intratumoral IL-8 transcript levels in high-risk (n = 11) and low risk (n = 7) tumors were assessed by quantitative real-time PCR. RNA was isolated from snap-frozen human tumor samples obtained at surgery. Data are represented as picograms target mRNA corrected for nanograms rRNA (internal standard). Mean ± SEM of is reported. [P = .018 (*)]. B) Analysis of microarray data comparing IL-8 mRNA in PTC (n = 51) vs. ATC (n = 4) (20). Statistical significance was evaluated with two-tailed t test [P = .052].

Discussion

In this study, we have used a selective genetic inhibitor of NF-κB to investigate the role of NF-κB signaling in thyroid tumorigenesis in orthotopic and metastatic nude mouse models of thyroid cancer. Inhibition of NF-κB signaling reduces orthotopic and metastatic tumor growth in these models and could be a useful target of directed pharmacotherapy. Bortezomib, a proteasome inhibitor that is approved for multiple myeloma and mantle cell lymphoma, can inhibit NF-κB signaling but has many other targets. Newer drugs, including GO-Y030, which targets IKKβ, may prove to be more specific and effective NF-κB inhibitors. Distinct mechanisms seem to govern NF-κB-dependent tumor growth in two of the thyroid cancer cell lines in our studies (Supplemental Table 3). NF-κB signaling is critical for direct effects on cell proliferation in tumors derived from the 8505C cell line, which is supported by decreased mitotic index in these tumors and previously demonstrated in vitro reduction of viable cells only in this cell line (4). Conversely, the mechanism by which NFkB signaling affects tumor growth in the BCPAP cell line seems to not be by direct effects on cell proliferation but through secretion of proteins that affect the microenvironment and angiogenesis. This angiogenesis mechanism of NF-κB signaling seems to be an important mechanism in thyroid cancer that the direct effect on cell proliferation, because all four cell lines tested had reduced in vitro angiogenesis in response to NF-κB signaling inhibition (Supplemental Table 3).

Without the ability to promote neovascularization, cancers are unable to grow beyond a volume of 1–2 mm3 (23). Pathological angiogenesis favors the secretion of excess proangiogenic factors, the tumor vasculature is functionally and structurally abnormal, resulting in an excessively branched and hemorrhagic blood supply (24).

Thyroid cancer angiogenesis and tumorigenesis is likely mediated by NF-κB-dependent regulation of secreted proteins. In the present study, we have begun to define the NF-κB-dependent ”secretome” in advanced thyroid cancer. Thrombospondin (TSP-1) secretion was increased by NF-κB inhibition in our model. TSP-1 exerts its angiostatic functions through its interaction with CD36 and β1-integrins on the surface of endothelial cells, resulting in inhibition of endothelial cell migration (25). Conversely, secretion of IGFBP-3 and DPPIV, both of which represent proangiogenic factors, were decreased in response to NF-κB inhibition. The former has been shown to induce angiogenesis in both in vitro and in vivo angiogenesis assays (26), whereas the latter has been implicated in the proteolytic processing of several proangiogenic factors (27). These secreted proteins were not further analyzed in this study but are interesting potential mechanistic and therapeutic targets in thyroid cancer growth and progression. In this study, we chose to focus on IL-8, given its high degree of regulation by NF-κB in many thyroid cancer cell lines. An association between IL-8 secretion and tumorigenesis has been previously shown in non–small-cell lung cancer (28). Here, we demonstrate similar findings in a panel of five thyroid cancer cell lines, three of which secrete very low levels of IL-8 and are not capable of forming tumors in vivo. The other two cell lines (BCPAP and 8505C) are highly tumorigenic and secrete levels of IL-8 that are 10–50 times higher than the nontumorigenic cell lines.

The above data linking IL-8 with aggressive tumor formation in mouse models suggests that IL-8 may be a useful prognostic indicator in predicting aggressive cancers. In breast cancer, IL-8 has been shown to correlate with tumor burden, progression, and nodal metastases (29). Similarly, in hepatocellular carcinoma, plasma IL-8 has been shown to correlate with tumor size and stage, vascular invasion, as well as decreased disease-free and overall survival (30). In this report, we show that intratumoral levels of IL-8 mRNA are significantly higher in patients with high-risk thyroid cancer compared with those with low-risk disease, and we observe a trend in higher IL-8 mRNA levels in ATC compared with PTC tumors. These data would support the association of IL-8 with aggressive behavior in thyroid cancer.

NF-κB serves as an important regulator of IL-8 mRNA levels and secretion in four different thyroid cancer cell lines. Furthermore, we have demonstrated that this regulation occurs, at least in part, through IL-8 promoter regulation. Similar findings have been observed in melanoma cells (31). Alternatively, NF-κB does not regulate IL-8 transcript levels in the 8505C cell line, indicating the presence of an alternative mechanism of regulation in this cancer cell line. Indeed, numerous mechanisms of IL-8 regulation independent of NF-κB have been described, including the AP-1, HIF-1α, and MAPK pathways (32–36).

In summary, we show that inhibition of NF-κB signaling reduces thyroid cancer cell growth through distinct mechanisms (Supplemental Table 3), inhibition of proliferation, and inhibition angiogenesis (potentially through IL-8 transcription and secretion). Indeed, inhibition of NF-κB signaling has been shown to attenuate tumor growth via suppression of tumor angiogenesis (37–39), and this finding has been linked to down-regulation of IL-8 and VEGF. IL-8 seems to be a marker of tumor aggressiveness and NF-κB activity in advanced thyroid cancer. This cytokine may also be an important therapeutic target.

Acknowledgments

We thank Drs Jeffrey Myers and Maria Gule for their guidance with establishing the orthotopic thyroid cancer model, and Xiao-Min Yu and Dr Herbert Chen for providing RNA from tissue of patients with advanced tall cell thyroid carcinoma.

This work was supported by NIH/NCI (research grant R01 CA100560) and the Mary Rossick Kern and Jerome H Kern Endowment for Endocrine Neoplasms Research. RT-PCR studies were performed by the University of Colorado Cancer Center Gene Expression Core. UCCC DNA Sequencing and Analysis Core, UCCC Pathology Core, and Small Animal Imaging Core are supported by NCI Cancer Center, grant P30 CA046934.

Disclosure Summary: The authors have nothing to disclose.

Footnotes

- DPPIV

- dipeptidyl peptidase-4

- FBS

- fetal bovine serum

- IGFBP

- insulin-like growth factor binding protein

- LV

- left ventricle

- MAPK

- mitogen-activated protein kinase

- NF-κB

- nuclear factor κB

- PTC

- papillary thyroid cancer

- TSP-1

- thrombospondin-1

- VEGF

- vascular endothelial growth factor.

References

- 1. Haugen BR, Sherman SI. Evolving approaches to patients with advanced differentiated thyroid cancer. Endocr Rev. 2013;34(3):439–455 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Pfister DG, Fagin JA. Refractory thyroid cancer: a paradigm shift in treatment is not far off. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26(29):4701–4704 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Hanahan D, Weinberg RA. The hallmarks of cancer. Cell. 2000;100(1):57–70 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Bauerle KT, Schweppe RE, Haugen BR. Inhibition of nuclear factor-kappa B differentially affects thyroid cancer cell growth, apoptosis, and invasion. Mol Cancer. 2010;9:117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Visconti R, Cerutti J, Battista S, et al. Expression of the neoplastic phenotype by human thyroid carcinoma cell lines requires NFkappaB p65 protein expression. Oncogene. 1997;15(16):1987–1994 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Pacifico F, Mauro C, Barone C, et al. Oncogenic and anti-apoptotic activity of NF-kappa B in human thyroid carcinomas. J Biol Chem. 2004;279(52):54610–54619 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Vasko V, Espinosa AV, Scouten W, et al. Gene expression and functional evidence of epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition in papillary thyroid carcinoma invasion. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104(8):2803–2808 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Fabien N, Fusco A, Santoro M, Barbier Y, Dubois PM, Paulin C. Description of a human papillary thyroid carcinoma cell line. Morphologic study and expression of tumoral markers. Cancer. 1994;73(8):2206–2212 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Xu X, Quiros RM, Gattuso P, Ain KB, Prinz RA. High prevalence of BRAF gene mutation in papillary thyroid carcinomas and thyroid tumor cell lines. Cancer Res. 2003;63(15):4561–4567 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Gustavsson B, Hermansson A, Andersson AC, et al. Decreased growth rate and tumour formation of human anaplastic thyroid carcinoma cells transfected with a human thyrotropin receptor cDNA in NMRI nude mice treated with propylthiouracil. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 1996;121(2):143–151 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Tanaka J, Ogura T, Sato H, Hatano M. Establishment and biological characterization of an in vitro human cytomegalovirus latency model. Virology. 1987;161(1):62–72 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Ito T, Seyama T, Iwamoto KS, et al. In vitro irradiation is able to cause RET oncogene rearrangement. Cancer Res. 1993;53(13):2940–2943 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Schweppe RE, Klopper JP, Korch C, et al. Deoxyribonucleic acid profiling analysis of 40 human thyroid cancer cell lines reveals cross-contamination resulting in cell line redundancy and misidentification. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2008;93(11):4331–4341 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Singh RP, Dhanalakshmi S, Agarwal C, Agarwal R. Silibinin strongly inhibits growth and survival of human endothelial cells via cell cycle arrest and downregulation of survivin, Akt and NF-kappaB: implications for angioprevention and antiangiogenic therapy. Oncogene. 2005;24(7):1188–1202 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Ahn SH, Henderson Y, Kang Y, et al. An orthotopic model of papillary thyroid carcinoma in athymic nude mice. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2008;134(2):190–197 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Kim S, Park YW, Schiff BA, et al. An orthotopic model of anaplastic thyroid carcinoma in athymic nude mice. Clin Cancer Res. 2005;11(5):1713–1721 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Wood WM, Sharma V, Bauerle KT, et al. PPARgamma Promotes Growth and Invasion of Thyroid Cancer Cells. PPAR Res. 2011;2011:171765. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Chan CM, Jing X, Pike LA, et al. Targeted inhibition of Src kinase with dasatinib blocks thyroid cancer growth and metastasis. Clin Cancer Res. 2012;18(13):3580–3591 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Kang Y. Analysis of cancer stem cell metastasis in xenograft animal models. Methods Mol Biol. 2009;568:7–19 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Giordano TJ, Kuick R, Thomas DG, et al. Molecular classification of papillary thyroid carcinoma: distinct BRAF, RAS, and RET/PTC mutation-specific gene expression profiles discovered by DNA microarray analysis. Oncogene. 2005;24(44):6646–6656 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Le X, Shi Q, Wang B, et al. Molecular regulation of constitutive expression of interleukin-8 in human pancreatic adenocarcinoma. J Interferon Cytokine Res. 2000;20(11):935–946 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Staton CA, Reed MW, Brown NJ. A critical analysis of current in vitro and in vivo angiogenesis assays. Int J Exp Pathol. 2009;90(3):195–221 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Hillen F, Griffioen AW. Tumour vascularization: sprouting angiogenesis and beyond. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 2007;26(3–4):489–502 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Jain RK. Normalization of tumor vasculature: an emerging concept in antiangiogenic therapy. Science. 2005;307(5706):58–62 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Tabruyn SP, Griffioen AW. Molecular pathways of angiogenesis inhibition. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2007;355(1):1–5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Granata R, Trovato L, Lupia E, et al. Insulin-like growth factor binding protein-3 induces angiogenesis through IGF-I- and SphK1-dependent mechanisms. J Thromb Haemost. 2007;5(4):835–845 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Bauvois B. Transmembrane proteases in cell growth and invasion: new contributors to angiogenesis? Oncogene. 2004;23(2):317–329 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Arenberg DA, Kunkel SL, Polverini PJ, Glass M, Burdick MD, Strieter RM. Inhibition of interleukin-8 reduces tumorigenesis of human non-small cell lung cancer in SCID mice. J Clin Invest. 1996;97(12):2792–2802 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Benoy IH, Salgado R, van Dam P, et al. Increased serum interleukin-8 in patients with early and metastatic breast cancer correlates with early dissemination and survival. Clin Cancer Res. 2004;10(21):7157–7162 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Ren Y, Poon RT, Tsui HT, et al. Interleukin-8 serum levels in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma: correlations with clinicopathological features and prognosis. Clin Cancer Res. 2003;9(16 Pt 1):5996–6001 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Huang S, Deguzman A, Bucana CD, Fidler IJ. Level of interleukin-8 expression by metastatic human melanoma cells directly correlates with constitutive NF-kappaB activity. Cytokines Cell Mol Ther. 2000;6(1):9–17 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Kunsch C, Rosen CA. NF-kappa B subunit-specific regulation of the interleukin-8 promoter. Mol Cell Biol. 1993;13(10):6137–6146 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Wolf JS, Chen Z, Dong G, et al. IL (interleukin)-1alpha promotes nuclear factor-kappaB and AP-1-induced IL-8 expression, cell survival, and proliferation in head and neck squamous cell carcinomas. Clin Cancer Res. 2001;7(6):1812–1820 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Arsura M, Panta GR, Bilyeu JD, et al. Transient activation of NF-kappaB through a TAK1/IKK kinase pathway by TGF-beta1 inhibits AP-1/SMAD signaling and apoptosis: implications in liver tumor formation. Oncogene. 2003;22(3):412–425 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Cane G, Ginouves A, Marchetti S, et al. HIF-1alpha mediates the induction of IL-8 and VEGF expression on infection with Afa/Dr diffusely adhering E. coli and promotes EMT-like behaviour. Cell Microbiol. 2010;12(5):640–653 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Sooranna SR, Engineer N, Loudon JA, Terzidou V, Bennett PR, Johnson MR. The mitogen-activated protein kinase dependent expression of prostaglandin H synthase-2 and interleukin-8 messenger ribonucleic acid by myometrial cells: the differential effect of stretch and interleukin-1{beta}. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2005;90(6):3517–3527 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Duffey DC, Chen Z, Dong G, et al. Expression of a dominant-negative mutant inhibitor-kappaBalpha of nuclear factor-kappaB in human head and neck squamous cell carcinoma inhibits survival, proinflammatory cytokine expression, and tumor growth in vivo. Cancer Res. 1999;59(14):3468–3474 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Xiong HQ, Abbruzzese JL, Lin E, Wang L, Zheng L, Xie K. NF-kappaB activity blockade impairs the angiogenic potential of human pancreatic cancer cells. Int J Cancer. 2004;108(2):181–188 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Fujioka S, Sclabas GM, Schmidt C, et al. Inhibition of constitutive NF-kappa B activity by I kappa B alpha M suppresses tumorigenesis. Oncogene. 2003;22(9):1365–1370 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]