Abstract

Context:

Classical congenital adrenal hyperplasia (CAH) due to 21-hydroxylase deficiency can cause life-threatening adrenal crises as well as severe hypoglycemia, especially in very young children. Studies of CAH patients 4 years old or older have found abnormal morphology and function of the adrenal medulla and lower levels of epinephrine and glucose in response to stress than in controls. However, it is unknown whether such adrenomedullary abnormalities develop in utero and/or exist during the clinically high-risk period of infancy and early childhood.

Objective:

The objective of the study was to characterize adrenomedullary function in infants with CAH by comparing their catecholamine levels with controls.

Design/Settings:

This was a prospective cross-sectional study in a pediatric tertiary care center.

Main Outcome Measures:

Plasma epinephrine and norepinephrine levels were measured by HPLC.

Results:

Infants with CAH (n = 9, aged 9.6 ± 11.4 d) had significantly lower epinephrine levels than controls [n = 12, aged 7.2 ± 3.2 d: median 84 [(25th; 75th) 51; 87] vs 114.5 (86; 175.8) pg/mL, respectively (P = .02)]. Norepinephrine to epinephrine ratios were also significantly higher in CAH patients than controls (P = .01). The control infants had primary hypothyroidism, but pre- and posttreatment analyses revealed no confounding effects on catecholamine levels.

Conclusions:

This study demonstrates for the first time that infants with classical CAH due to 21-hydroxylase deficiency have significantly lower plasma epinephrine levels than controls, indicating that impaired adrenomedullary function may occur during fetal development and be present from birth. A longitudinal study of adrenomedullary function in CAH patients from infancy through early childhood is warranted.

Classical congenital adrenal hyperplasia (CAH) due to 21-hydroxylase deficiency is the most common cause of primary adrenal insufficiency in children, affecting 1:10 000–25 000 newborns (1). In this condition, there is deficient cortisol and aldosterone production, potentially leading to life-threatening adrenal crises. Although typically thought of as a disease of the adrenal cortex, CAH also affects the morphology and function of the adrenal medulla in children as young as 4 years old (2–4). Normal development of the medulla, the major site of production of epinephrine, depends on exposure to cortisol produced from the cortex, with important crosstalk occurring between cells of the cortex and medulla (5, 6). From early fetal life onward, intraadrenal cortisol induces phenylethanolamine N-methyltransferase, the enzyme responsible for converting norepinephrine to epinephrine in the chromaffin cells of the medulla (7, 8). Epinephrine and cortisol are both part of the stress response and, as counterregulatory hormones, also help to prevent hypoglycemia.

Lower levels of epinephrine in CAH children correlate with increased rates of hospitalization for adrenal crises (2). When subjected to the stress of moderate- to high-intensity exercise, CAH adolescents with a partial epinephrine deficiency show lower epinephrine and glucose levels as a physiological response than controls (9, 10). Like children with CAH, the 21-hydroxylase-deficient mouse exhibits severely impaired catecholamine production, as well as structural abnormalities of the medulla and cortex, as early as 1 week of age (11). Thus, both human and animal studies suggest that CAH children are likely to have abnormal adrenomedullary development from an early age. The neonate has a physiological catecholamine surge in response to the stress of normal delivery and exposure to cold. Although the surge consists predominantly of norepinephrine, epinephrine is known to be the major regulator of gluconeogenesis and glycogenolysis in the counterregulatory response to hypoglycemia in newborns (12). Further studies are needed to understand adrenomedullary morphology and function in very young children, especially those with CAH, who are at greater risk for seizures, cognitive impairment (13–15), and increased mortality (16) due to severe hypoglycemia associated with illness. Therefore, we undertook the first study of plasma catecholamine levels in infants with and without CAH. We hypothesize that infants with CAH, due to impaired fetal adrenal development, have lower epinephrine levels than age-matched controls.

Study Participants and Methods

The study was cross-sectional and approved by the Children's Hospital Los Angeles Institutional Review Board. Parents of infants gave written informed consent.

Nine infants with CAH were enrolled. CAH was diagnosed based on positive newborn filter paper screening (California Department of Health Services) with elevated confirmatory serum 17-hydroxyprogesterone (17-OHP) level, increased serum androgen and plasma renin levels, hyperpigmentation, and ambiguous genitalia in eight females. Genotyping was not performed due to limitations on blood volume (2 mL/kg) with the clinically indicated blood draw. Our control group consisted of infants with congenital primary hypothyroidism (n = 12), diagnosed by a positive newborn screen (elevated TSH) and confirmatory serum testing, with no other medical problems. Of note, our institutional review board did not allow blood draws in completely healthy infants unless clinically indicated. Participants were recruited at the pediatric endocrinology clinic or ward. Both groups consisted of full-term infants (except for one 36.3 week old CAH baby), appropriate for gestational age, with no statistically significant difference in age, weight, or length (birth/study visit), head circumference, or vital signs (Table 1). There was a female preponderance in both groups; all CAH females had ambiguous genitalia (12% Prader 2, 25% Prader 3, and 63% Prader 4). Four CAH infants had mild electrolyte disturbances (Na 132.5 ± 1.3 mEq/L, K 6.23 ± 0.9 mEq/L) but were not acutely ill. One CAH baby diagnosed at age 1 week had a congenital heart defect repair at age 2 weeks (3 wk prior to the study visit) but was not acutely ill or on medications known to interfere with the catecholamine assay.

Table 1.

Clinical Characteristics of Newborns With CAH due to 21-Hydroxylase Deficiency and Controls

| CAH | Control | |

|---|---|---|

| n | 9 | 12 |

| Gender (female) | 8 | 12 |

| Gestational age, wka | 38.9 ± 0.5 | 39.6 ± 0.4 |

| Birth weight, kga | 3.27 ± 0.51 | 3.52 ± 0.47 |

| Birth length, cma | 50.06 ± 1.74 | 50.11 ± 1.97 |

| Age at visit, da | 9.56 ± 11.35 | 7.17 ± 3.16 |

| Visit weight, kga | 3.17 ± 0.47 | 3.56 ± 0.42 |

| Visit length, cma | 50.04 ± 2.14 | 49.63 ± 1.58 |

| Head circumference, cma | 34.8 ± 1.75 | 35.27 ± 3.23 |

| Heart rate, beats/mina | 130.2 ± 14.69 | 130.9 ± 19.32 |

| Systolic blood pressure, mm Hga | 78.63 ± 10.82 | 89.58 ± 17.5 |

| Diastolic blood pressure, mm Hga | 48.00 ± 5.2 | 55.50 ± 9.15 |

| Newborn screen 17-OHP, ng/dLb | 6256 (4708; 14899) | <30 |

No significant difference between groups was seen (mean ± SD).

Median with interquartile range (25th; 75th percentiles); to convert 17-OHP to SI units, multiply by 0.0302 = nanomoles per liter.

All infants had a history and physical examination, including length, weight, head circumference, heart rate, and blood pressure measurements. Plasma catecholamines and serum cortisol were drawn in the supine position at the time of a clinically indicated blood test. Four participants had cortisol treatment initiated prior to the study visit.

In addition to the main cross-sectional comparison, longitudinal follow-up of the control group was performed to assess hypothyroid infants after treatment with levothyroxine (LT4; 10–12 μg/kg·d). They returned for follow-up in 48 ± 19 days for a history, physical examination, and repeat blood tests.

Fractionated plasma catecholamine levels were quantified by HPLC (Quest Diagnostics Nichols Institute). Interassay and intraassay coefficients of variation were less than 5%. The limit of detection was less than 40 pg/mL with normative ranges derived from published data (17). Serum cortisol was quantified by liquid chromatography/tandem mass spectrometry (Quest Diagnostics Nichols Institute).

Statistical analysis

Patient characteristics of CAH and control infants were compared using an independent t test or χ2 test for continuous and categorical characteristics, respectively. Descriptive statistics and comparisons of demographics were used. Given the small sample size, Mann-Whitney U tests (Tukey box and whisker plot) were used to compare catecholamine levels between infant groups to avoid undue influence of potential outliers. Wilcoxon signed-rank tests were used to compare visits 1 and 2 within the control group. Data are reported as medians (25th percentile; 75th percentile) and were analyzed using SPSS (V.21; IBM Corp) (for all analyses, α = .05).

Results

In the CAH group, the median newborn screen 17-OHP level was 6256 ng/dL (4708; 14 899), with confirmatory 17-OHP of 8149 ng/dL (1856; 20 544) (SI unit conversion × 0.0302 = nanomoles per liter); T 52 ng/dL (21; 585) (SI unit conversion × 0.0347 = nanomoles per liter); and androstenedione 258.5 ng/dL (83.3; 11 211) (SI unit conversion × 0.0349 = nanomoles per liter). There was no correlation between epinephrine and newborn screen 17-OHP (P = .6), confirmatory 17-OHP (P = .7), T (P = .6), or (17-OHP + androstenedione)/cortisol (P = .7) prior to treatment. The CAH patients were not sick or in distress at their study visit and had cortisol 2.1 μg/dL (1.2; 5.7) (SI unit conversion × 27.6 = nanomoles per liter).

Control infants were not in distress at either visit [cortisol visit 1: 7.5 μg/dL (3.0; 9.3) vs visit 2: 3.0 (1.5; 6.0), P = .2] and were no longer hypothyroid by visit 2 on LT4 treatment [visit 1: free T4 0.8 ng/dL (0.2; 2.0) (reference 2.2–5.3) and TSH 160 μU/mL (75.2; 230.5) (reference 3.2–35); visit 2: free T4 4.0 ng/dL (1.4; 4.7) (reference 1.6–3.8 < 2 wk, 0.9–2.2 ng/dL > 2 wk), and TSH 1.2 μIU/mL (0.5; 10.8) (reference 1.70–9.10 < 1 mo, 0.80–8.20 ≥ 1 mo); SI unit conversion × 12.87 = picomoles per liter].

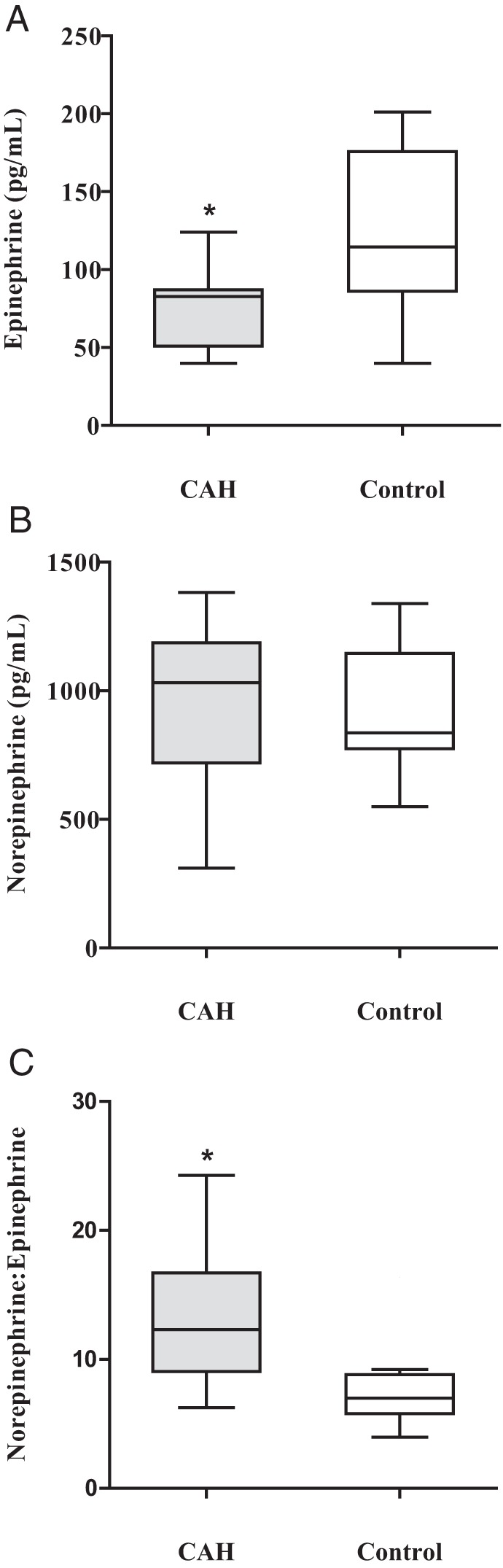

The main finding of this study was significantly lower plasma epinephrine levels in CAH infants than controls [Figure 1A; 84 (51; 87) vs 114.5 (86; 175.8) pg/mL, respectively, P = .02]. Plasma norepinephrine levels did not differ between groups [Figure 1B; CAH 1031 (719; 1187) vs controls 836 (774; 1145) pg/mL, P = .6], although the norepinephrine to epinephrine ratio was significantly higher in CAH infants than controls [Figure 1C; CAH 12.3 (9.1; 16.7) vs controls 7.0 (5.8; 8.8), P = .01].

Figure 1.

Baseline plasma catecholamine concentrations in newborns with classical CAH due to 21-hydroxylase deficiency compared with control newborns. A, Epinephrine. B, Norepinephrine. C, Norepinephrine to epinephrine ratio. Data are shown as box (median and interquartile range 25th to 75th percentiles)-and-whisker (Tukey method) plots. *, P < .05. To convert to SI units, multiply epinephrine by 5.454 = picomoles per liter, and norepinephrine by 5.914 = picomoles per liter.

In controls, a longitudinal analysis showed no significant changes between visits 1 and 2 in either epinephrine [114.5 (86; 175.8) vs 100 (87; 119) pg/mL, P = .8] or norepinephrine levels [836 (774; 1145) vs 1109 (838.8; 1410) pg/mL, P = .2].

Discussion

This study demonstrates that infants with CAH have significantly lower plasma epinephrine levels than age-matched controls, which carries significance for prediction of disease severity at an early stage in life (18). When stressed, infants and toddlers with CAH are at high risk for morbidity and mortality from adrenal crises and severe hypoglycemia, with epinephrine deficiency possibly contributing to further risk (19). There is a paucity of studies on catecholamine levels in infants, and to our knowledge, there are no published studies on catecholamine levels in infants with CAH.

A normal adrenal cortex is necessary for adrenomedullary development and function in the fetus (5–8), and although older patients with CAH have an adrenal medulla that is morphologically and functionally abnormal (2, 9, 10), it is not known when this adrenomedullary disruption begins. Based on our finding of decreased plasma epinephrine levels in CAH infants shortly after birth, it is reasonable to speculate that abnormal adrenomedullary development may begin in utero and is most likely due to intraadrenal cortisol deficiency, limiting the survival and function of the developing medullary chromaffin cells (5, 8).

We and others have found that, although plasma epinephrine levels are low in CAH, norepinephrine is not affected (2, 9, 10), likely due to reduced phenylethanolamine N-methyltransferase activity in the adrenal medulla (7, 8), but also because norepinephrine is primarily derived from sympathetic nerve endings (9). A large CAH study has shown increased plasma norepinephrine compared with controls (3), consistent with increased production of norepinephrine from the sympathetic nervous system (SNS), as occurs in patients with acquired adrenal insufficiency (20). Given the complexity of the stress system [SNS, hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal cortex, and sympathoadrenal (medulla) system], the SNS could overcompensate for impaired adrenomedullary function through the shared activation of the adrenal medulla and SNS by sympathetic neurons (21). In support of this concept, our study showed a greater norepinephrine to epinephrine ratio in infants with CAH than controls, although it is possible that this is more of a reflection of decreased epinephrine levels. The sympathoadrenal system helps adapt to stress, involving close communication with the adrenocortical system (22), and perhaps playing an even more important role during fetal and infant life than during later years (11, 12). Therefore, more studies are needed to understand how the impaired sympathoadrenal and adrenocortical components of the stress system affect the SNS and the ability of the young CAH patient to adapt to stress.

To address the potential limitation posed by congenital hypothyroidism in the control infants, we measured catecholamine levels before and after treatment with LT4. According to studies in older patients, hypothyroidism increased norepinephrine levels (23) but did not significantly affect epinephrine (24, 25). In our controls with congenital hypothyroidism, there were no differences in catecholamine levels between the hypo- and euthyroid states, thus eliminating a potential confounding effect of hypothyroidism on catecholamine levels.

Although the small cohort size is an obvious limitation, catecholamine studies in older CAH children have used similar sample sizes (9, 10) and show similarly significant findings, implying sufficient power with these sample sizes. We surmise that the 18% difference in basal epinephrine levels between CAH and control infants would become increasingly relevant during times of high metabolic stress, such as severe illness (10). Four of our subjects were on hydrocortisone treatment for a brief time prior to catecholamine collection. However, our subanalysis of subjects before and after treatment showed no difference in catecholamines (data not shown). Physiological replacement of glucocorticoids and even typical supraphysiological stress doses do not appear to affect epinephrine or glucose measurements in patients with CAH (26), and catecholamine studies in older CAH patients have been conducted with subjects on hydrocortisone treatment (9, 10, 26). Thus, it is reasonable to conclude that hydrocortisone would not have a significant effect on epinephrine levels in subjects already started on replacement therapy. Due to the limited amount of blood that could safely be obtained from infants (2 mL/kg), metanephrine and normetanephrine levels, and CYP21A2 gene analysis to assess phenotype-genotype correlation, were not performed.

We conclude that infants with CAH have impaired adrenomedullary function that may affect their early postnatal health. This study begins a needed exploration of the stress response in young patients with adrenal insufficiency to develop a more thorough understanding of catecholamine physiology in these patients, particularly during times of severe illness. A larger prospective, longitudinal study of catecholamine levels and their metabolites in CAH patients from infancy is warranted to explore potential changes in adrenal function with age and in response to stress.

Acknowledgments

We gratefully thank our patients and their families for their participation. We also thank Norma Castaneda, Anh Dao-Tran, MPH, Carol Winkelman, and the Children's Hospital Los Angeles Clinical Trials Unit for their assistance and support.

The contents of this study are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

This work was supported by Southern California Clinical and Translational Science Institute (National Institutes of Health/National Center for Research Resources/National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences) through Grant KL2TR000131 (to M.S.K.), the Children's Hospital Los Angeles Clinical and Translational Science Institute Clinical Trials Unit Grant 1UL1RR031986, and The Abell Foundation.

Disclosure Summary: The authors have nothing to disclose.

Footnotes

- CAH

- classical congenital adrenal hyperplasia

- LT4

- levothyroxine

- 17-OHP

- 17-hydroxyprogesterone

- SNS

- sympathetic nervous system.

References

- 1. Kim MS, Donohoue PA. Adrenal disorders. In: Kappy MS, Allen DB, Geffner ME, eds. Pediatric Practice Endocrinology. 2nd ed. New York: McGraw-Hill Professional; 2014 [Google Scholar]

- 2. Merke DP, Chrousos GP, Eisenhofer G, et al. Adrenomedullary dysplasia and hypofunction in patients with classic 21-hydroxylase deficiency. N Engl J Med. 2000;343:1362–1368 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Tutunculer F, Saka N, Arkaya SC, Abbasoglu S, Bas F. Evaluation of adrenomedullary function in patients with congenital adrenal hyperplasia. Horm Res. 2009;72:331–336 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Charmandari E, Eisenhofer G, Mehlinger SL, et al. Adrenomedullary function may predict phenotype and genotype in classic 21-hydroxylase deficiency. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2002;87:3031–3037 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Ehrhart-Bornstein M, Breidert M, Guadanucci P, et al. 17α-Hydroxylase and chromogranin A in 6th week human fetal adrenals. Horm Metab Res. 1997;29:30–32 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Schinner S, Bornstein SR. Cortical-chromaffin cell interactions in the adrenal gland. Endocr Pathol. 2005;16:91–98 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Wong DL. Epinephrine biosynthesis: hormonal and neural control during stress. Cell Mol Neurobiol. 2006;26:891–900 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Axelrod J, Reisine TD. Stress hormones: their interaction and regulation. Science. 1984;224:452–459 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Weise M, Mehlinger SL, Drinkard B, et al. Patients with classic congenital adrenal hyperplasia have decreased epinephrine reserve and defective glucose elevation in response to high-intensity exercise. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2004;89:591–597 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Green-Golan L, Yates C, Drinkard B, et al. Patients with classic congenital adrenal hyperplasia have decreased epinephrine reserve and defective glycemic control during prolonged moderate-intensity exercise. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2007;92:3019–3024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Bornstein SR, Tajima T, Eisenhofer G, Haidan A, Aguilera G. Adrenomedullary function is severely impaired in 21-hydroxylase-deficient mice. FASEB J. 1999;13:1185–1194 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Jackson L, Williams FL, Burchell A, Coughtrie MW, Hume R. Plasma catecholamines and the counterregulatory responses to hypoglycemia in infants: a critical role for epinephrine and cortisol. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2004;89:6251–6256 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Hinde FR, Johnston DI. Hypoglycaemia during illness in children with congenital adrenal hyperplasia. Br Med J (Clin Res Ed). 1984;289:1603–1604 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Mackinnon J, Grant DB. Hypoglycaemia in congenital adrenal hyperplasia. Arch Dis Child. 1977;52:591–593 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Donaldson MD, Thomas PH, Love JG, Murray GD, McNinch AW, Savage DC. Presentation, acute illness, and learning difficulties in salt wasting 21-hydroxylase deficiency. Arch Dis Child. 1994;70:214–218 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Swerdlow AJ, Higgins CD, Brook CG, et al. Mortality in patients with congenital adrenal hyperplasia: a cohort study. J Pediatr. 1998;133:516–520 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Candito M, Albertini M, Politano S, Deville A, Mariani R, Chambon P. Plasma catecholamine levels in children. J Chromatogr. 1993;617:304–307 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Speiser PW. Adrenomedullary function may predict phenotype and genotype in classic 21-hydroxylase deficiency. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2002;87:3029–3030 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Keil MF, Bosmans C, Van Ryzin C, Merke DP. Hypoglycemia during acute illness in children with classic congenital adrenal hyperplasia J Pediatr Nurs. 2010;25:18–24 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Zuckerman-Levin N, Tiosano D, Eisenhofer G, Bornstein S, Hochberg Z. The importance of adrenocortical glucocorticoids for adrenomedullary and physiological response to stress: a study in isolated glucocorticoid deficiency. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2001;86:5920–5924 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Bornstein SR, Chrousos GP. Clinical review 104: adrenocorticotropin (ACTH)- and non-ACTH-mediated regulation of the adrenal cortex: neural and immune inputs. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1999;84:1729–1736 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Goldstein DS. Adrenal responses to stress. Cell Mol Neurobiol. 2010;30:1433–1440 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Coulombe P, Dussault JH, Walker P. Catecholamine metabolism in thyroid disease. II. Norepinephrine secretion rate in hyperthyroidism and hypothyroidism. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1977;44:1185–1189 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Coulombe P, Dussault JH, Walker P. Plasma catecholamine concentrations in hyperthyroidism and hypothyroidism. Metabolism. 1976;25:973–979 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Stoffer SS, Jiang NS, Gorman CA, Pikler GM. Plasma catecholamines in hypothyroidism and hyperthyroidism. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1973;36:587–589 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Weise M, Drinkard B, Mehlinger SL, et al. Stress dose of hydrocortisone is not beneficial in patients with classic congenital adrenal hyperplasia undergoing short-term, high-intensity exercise. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2004;89:3679–3684 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]