Abstract

Atrial fibrillation (AF) is the most common arrhythmia targeted by catheter ablation. Despite significant advances in our understanding of AF, ablation outcomes remain suboptimal, and this is due in large part to an incomplete understanding of the underlying sustaining mechanisms of AF. Recent developments of patient-tailored and physiology-based computational mapping systems have identified localized electrical spiral waves, or rotors, and focal sources as mechanisms that may represent novel targets for therapy. This report provides an overview of Focal Impulse and Rotor Modulation (FIRM) mapping, which reveals that human AF is often not actually driven by disorganized activity but instead that disorganization is secondary to organized rotors or focal sources. Targeted ablation of such sources alone can eliminate AF and, when added to pulmonary vein isolation, improves long-term outcome compared with conventional ablation alone. Translating mechanistic insights from such patient-tailored mapping is likely to be crucial in achieving the next major advances in personalized medicine for AF.

Keywords: Atrial fibrillation, Ablation, Focal sources, Rotors, Substrate, Trigger

Introduction

Atrial fibrillation (AF) is the most common sustained arrhythmia in the world, whose accelerating incidence and association with stroke, heart failure, dementia, and death make its management a top priority. However, recent clinical trials have questioned the value of pharmacologic agents both to limit ventricular rate [1] and to maintain sinus rhythm [2, 3•]. Conversely, great strides have been made in nonpharmacologic therapies for AF. Catheter-based ablation has been shown to be more effective than medications in patients with paroxysmal AF [4•,5•] and persistent AF [6], although outcomes are suboptimal with multicenter randomized controlled trials showing 40 %–50 % single procedure to 70 % multiprocedure success rates at 1 year for paroxysmal AF [4•,5•,7, 8] and lower success in persistent AF [9, 10].

One major limitation to substantial advances in outcome is our incomplete understanding of the mechanisms that underlie AF. As with other arrhythmias, AF initiates when a “trigger” (eg, premature beat from the pulmonary veins or elsewhere) interacts with “substrate” (eg, atrial tissue with abnormal anatomic/functional characteristics that sustains AF). However, while it is well understood that AF is triggered from sinus rhythm by premature atrial contractions or rapid tachycardias [9], it is less well-understood what occurs next ie, what mechanisms initiate or sustain AF? As such, current catheter-based ablation strategies have been based on the elimination of potential triggers at the pulmonary veins. Although it is widely accepted that mapping the AF substrate is necessary for the next stages of catheter ablation [9, 11], this has not been easily accomplished.

In this section, we will review recent technical advances in mapping patient-specific electrical substrates, which in many patients comprise spiral waves (rotors) or focal sources. Such sources show parallels to AF-sustaining rotors shown for decades in animal models of fibrillation [12, 13, 14•] and, in patients, were identified using novel computational approaches [15–17] after defining the spatio-temporal dynamics of atrial repolarization and conduction [18–20]. Focal impulse and rotor mapping (FIRM) enables near-real time mapping of the atria at the time of electrophysiological study to identify rotors and other patient-specific AF mechanisms for ablation, then remapping to confirm elimination. In clinical trials, FIRM-guided ablation has been shown to eliminate AF on long-term follow-up with no other ablation [21], validating the physiological role of identified sources, and when combined with traditional pulmonary vein isolation [22••].

Mechanisms Driving Human AF

Mapping AF is challenging because its activation is complex with considerable spatio-temporal variability when assessed clinically. Paradoxically, AF also exhibits underlying spatial-temporal reproducibility or organization by many analyses [23–27]. Several mechanisms for AF have been proposed in the classical literature, highlighting a dichotomy between localized mechanisms (rapidly-firing ectopic atrial drivers or single-circuit reentry) or spatially nonlocalized mechanisms (multiple wavelet reentry) that have existed for over a century.

Localized sources for AF were postulated by Garrey, Mines, and Lewis in the early 20th century, and reported in seminal canine studies by Schuessler, Cox, and Boineau [13, 28] who showed that AF is often sustained by stable, relatively large drivers. Using optical mapping in sheep studies, Jalife et al [14•,29] for the first time revealed electrical spiral waves, or rotors that perpetuate fibrillation. In recent canine studies, direct ablation of rotors was shown to suppress AF [30•]. Clinically, although rotors had not been identified or located until recently, multiple observations have strongly supported the existence of localized sources in patient subsets. These observations include the ability of a single ablation lesion to terminate persistent AF resistant to cardioversion [31] and recently various types of AF [22••, 31–33], and the ability of catheter pressure at a specific location to reproducibly terminate AF [32]. Indirect evidence for sources in human AF include reports of spatiotemporal stability [24], localized regions of stable high dominant frequency [23, 25, 26, 34], and reproducible vectors of AF propagation over time [35].

Multiple wavelet reentry, conversely, postulates that AF comprises meandering wavelets that collide and extinguish one another [36] and sustain AF without underlying driving sources. This hypothesis has become the prevailing conceptual model, but in many patients is unlikely to be the driving mechanism. For instance, nonlocalized mechanisms cannot readily explain clinical observations that favor localized sources including acute AF termination by single or very few ablation lesions at pulmonary veins (PVs) or other sites [22••, 31–33]. Moreover, while the Maze surgery is often taken as evidence in favor of nonlocalized mechanisms, Maze may also limit the tissue available for rotors or stable reentrant circuits as conceived by Cox, Schuessler, et al. at Washington University when developing the Maze procedure [13, 28]. Other limitations of work supporting nonlocalized mechanisms are that it mapped <10 % of atrial areas measured by MRI [37] in relatively few patients (n=49) [38, 39] and that recordings from many regions, when obtained, were not synchronized in time that limits spatial analysis. Perhaps most importantly, interventions to prove causality were not used so that disorganization could represent bystander activity. Finally, numerous groups have now shown organized ‘rotors’ of various durations in surgical [27] and electrophysiological [33, 40••, 41, 42•] studies of human AF.

Focal Impulse and Rotor Mapping (FIRM)

Rationale for Wide-Area Contact Mapping

One reason for our incomplete understanding of AF mechanisms lies in the challenges of mapping its complex spatio-temporal activity that varies on visual inspection, yet shows surprising spatiotemporal reproducibility on mathematical quantification. The major challenge has been to separate potentially reproducible elements (principal components) from disorganized activation in a clinically meaningful fashion.

Each of the existing mapping modalities has important limitations for AF. First, bipolar recordings may not accurately indicate local activation in AF, whether signals are fractionated or not (Figs. 1, 2 and 3 in [43•]), due to AF signal cancellation or augmentation between the poles of a bipole or between a unipole and its reference electrode. These issues may be compounded in mathematically inferred electrograms [44]. Surgical epicardial mapping is precise, but typically covers limited atrial areas [38] and may thus, miss organization outside a priori selected mapping regions. High-resolution optical mapping is theoretically ideal yet limited by dye toxicity in humans [11, 45•], and most maps have recorded for only short-durations that limits the ability to evaluate temporal and spatial stability or to remap after ablation to identify mechanism. Inability to separate bystander from mechanistic activation is well known to confuse the diagnosis and ablation of even simple electrophysiological disorders [46], and is likely just as relevant for AF.

We set out to map human AF using monophasic action potentials (MAPs), which may most faithfully represent local depolarization and repolarization than clinical alternatives, and thus, mitigate some of the above limitations [47]. A series of studies described the spatiotemporal dynamics of repolarization and conduction in human atria, and methods to physiological filter noise so to separate “principal components” of activation in AF from bystander disorganization. Features on resulting AF maps were then tested by ablation to prove whether they indicated AF- mechanisms (with improved patient outcomes) or bystanders.

Practical Approach to FIRM Mapping

Focal Impulse and Rotor Modulation (FIRM) mapping is a novel technique to identify patient-specific AF mechanisms, by recording AF electrograms in a wide field-of-view across the majority of both atria then using physiologically-directed computational methods to produce maps of AF propagation [16, 22••]. FIRM has revealed electrical rotors sustaining human AF for the first time, and has also enabled visualization of focal sources.

FIRM records AF in both atria using direct contact electrodes, the gold standard particularly for low-amplitude AF electrograms, in the form of 64-pole basket catheters each of 8 splines containing 8 electrodes. Basket catheters are advanced from the femoral vein into the right atrium (RA) or, transseptally, to the left atrium (LA). Recordings are made sequentially using 1 basket in each atrium in turn. Electrodes are separated by 4–6 mm along each spline and by 4–10 mm between splines. Catheters are manipulated to ensure good electrode contact and electrode locations are verified within the atrial geometry using fluoroscopy or electroanatomic mapping [22••]. It was predicted [48] and recently demonstrated [17] that human atria can support 1:1 activation in a shortest reentrant path of ~5 cm, requiring a minimum electrode spacing of ~10 mm for which these clinical catheters should be sufficient.

AF is recorded for 1 minute then exported for analysis using RhythmView (Topera, Palo Alto, CA). Native AF is mapped when possible, but when required, induced by burst pacing from the coronary sinus using a continuous incremental pacing protocol from cycle lengths 500 ms, continuously decrementing to 450 ms, 400 ms, 350 ms, 300 ms, then in 10 ms steps to AF. If required, isoproterenol is infused and pacing repeated. Recent data has shown that induced and spontaneous AF show very similar intra-atrial rates [49] and spatial propagation patterns [16] in the same patient.

Interpretation of FIRM Computational Maps of AF

Traditional a priori rules to include electrograms based on presumed minimum F-F intervals [50] or signal shape [39] are not clearly tailored to human atrial physiology. Therefore, computational mapping (FIRM) examines patient-specific AF electrograms based upon rate-dependent refractoriness (“restitution”) [51, 52] and conduction slowing [20]. AF electrograms resulting from such physiological filtering are used to construct propagation paths across both atria. Phase mapping is applied to identify regions that activate coherently (ie, together).

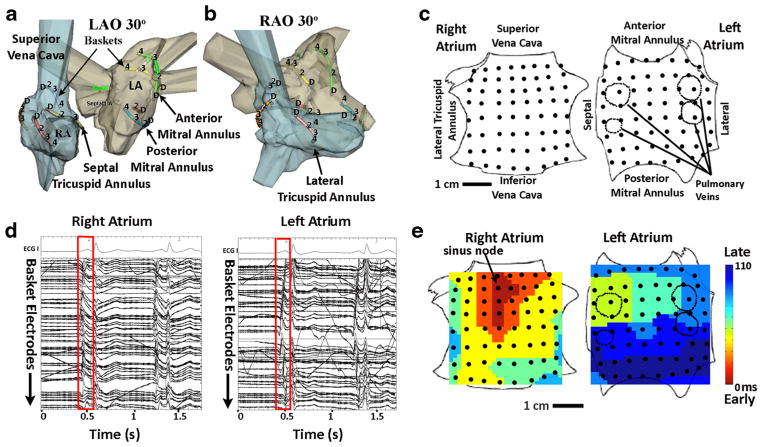

FIRM mapping results in movies of AF propagation that are the primary diagnostic tools in a case. Such movies are summarized in this manuscript as isochronal maps [19, 51, 53, 54]. An example isochronal map of a sinus beat is shown in Fig. 1, which also illustrates the nomenclature of FIRM maps. The LA is opened at its “equator” through the mitral valve, and the RA is opened along a central meridian through the tricuspid valve.

Fig. 1.

Mapping of the human atria. (a) Basket catheter splines are represented as colored lines within the right atrium (blue) and left atrium (grey) in the left anterior oblique and (b) right anterior oblique projections. For clarity, only alternate splines are shown. (c) Schematic representation of both atria as if opened through its poles (RA) or its equator (LA), with black dots representing electrode positions. (d) ECG leads and electrograms of 1 sinus rhythm beat (red box) recorded by baskets in the right and left atrium. (e) Isochronal maps of sinus rhythm activation, originating in the high right atrium (sinus node) and propagating to the lateral left atrium. Adapted with permission from: Narayan SM, Krummen DE, Enyeart MW, Rappel WJ. Computational mapping identifies localized mechanisms for ablation of atrial fibrillation. PloS One. 2012;7:e46034) [60]

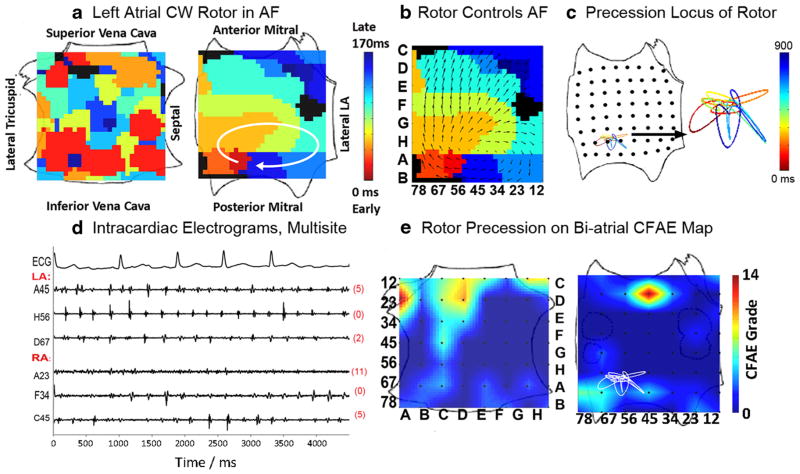

Rotors are defined as phase singularities with emanating spiral waves that disorganize in surrounding tissue. The core is often not precisely resolved, but bracketed between surrounding electrodes as one would clinically bracket an accessory pathway between adjacent coronary sinus electrodes. Repetitive focal drivers, the other AF-sustaining mechanism identified by FIRM mapping, are defined as activation emanating centrifugally from a source region. Multiple 1-minute epochs are typically analyzed over 5–10 minutes.

Clinically, rotors or focal drivers observed in FIRM maps are diagnosed as AF sources only if they lie in a spatially reproducible location (ie, showing spatial stability) for minutes (ie, showing temporal stability) [55]. This definition excludes transient or migratory activity that would be difficult to target for ablation. Figure 2a demonstrates an AF rotor in the low posterior LA, with disorganized and fibrillatory conduction in the RA.

Fig. 2.

Stable left atrial fibrillation (AF) rotor overlying minimal complex fractionated atrial electrograms (CFAE). (a) Left atrial rotor during AF (time bar=1 second), which (b) controls the direction of activation in surrounding atrium. (c) The path (locus) undertaken by rotor precession, with a color-coded time line. (d) Electrograms showing low CFAE score (=6) at the rotor site, referenced to (e). (e) Locus of AF rotor precession superimposed upon a CFAE map, demonstrating that the rotor overlies only a low-grade CFAE (yellow, 4–6). Adapted with permission from: Narayan SM, Shivkumar K, Krummen DE, Miller JM, Rappel W-J. Panoramic electrophysiological mapping but not individual electrogram morphology identifies sustaining sites for human atrial fibrillation (AF rotors and focal sources relate poorly to fractionated electrograms). Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol. 2013;6 [59•]

FIRM-Guided Ablation and Clinical Outcomes

Direct Ablation at AF Sources Identified by FIRM Maps

The spatial and temporal stability of sources makes them suitable ablation targets. Once rotors or focal sources are identified, they are directly targeted for ablation energy using any clinically indicated catheter. The rationale for localized ablation has been analogous to ablation of microreentrant focal atrial tachycardia, for which localized ablation is highly successful. In multicenter studies, FIRM ablation has been accomplished with a 3.5 mm tip irrigated catheter (Thermocool, Biosense-Webster, Diamond Bar, CA), an 8 mm tip nonirrigated catheter (Blazer, Boston Scientific, Natick, MA), or cryoablation. The ablation catheter is maneuvered to the location of the rotor core, as identified by fluoroscopy and/or electroanatomic mapping.

Multiple ablation lesions are placed typically over the source for ~2–3 cm2 of atrial tissue, via 5–10 ablations lesions each ~0.25 cm2 in area. This covers the area of rotor or focal source precession (Fig. 2c shows that this area can be quantified by phase mapping). These areas are small relative both current ablation approaches, and current estimates of atrial area from MRI of >100 cm2 [37]. The endpoint of FIRM guided ablation is elimination of all AF rotors/focal sources remapping, which is performed after each set of lesions.

Typically, 2–3 concurrent rotors are identified in each patient, requiring a total FIRM ablation time of ~15–20 minutes and ~5 cm2 ablation. FIRM ablation is commonly added to PV isolation, but if performed alone as recently demonstrated [21], results in a small ablated areas compared with conventional AF ablation.

The CONFIRM Trial

The CONFIRM trial was performed to test whether human AF may be sustained by localized sources—either electrical rotors or repetitive focal drivers—the elimination of which by FIRM ablation would improve outcomes compared with convention al AF ablation [22••].

For this study we recruited 92 subject undergoing 107 consecutive ablation procedures for drug-refractory AF, who were referred for ablation to the Veterans Affairs and University of California Medical Centers in San Diego, under IRB-approved protocol. Cases were prospectively enrolled a 2-arm design: FIRM-guided patients underwent ablation sources followed by conventional ablation (n=36), whereas FIRM-blinded patients underwent conventional ablation only (n=71) with FIRM mapping performed off-line and not used to guide ablation.

Patients had symptomatic AF, either paroxysmal or persistent, and by design, we included patients both at first ablation and a minority with prior unsuccessful conventional ablation The goal of broad inclusion was to test how AF-sustaining mechanisms (substrates) differ in patients with and without prior ablation, and with various presentations. The only exclusion criterion was an unwillingness or inability to provide informed consent. Supplemental Table 1 displays the clinical characteristics of the patient populations. Of note, persistent AF was present in 81 % of the FIRM-guided group, and 66 % of the FIRM-blinded group.

The primary long-term endpoint was defined as freedom from AF for up to 2 years after a single procedure, defined <1 % burden using continuous implanted ECG monitors, AF <30 seconds on quarterly event monitors (ie, monitoring for ≤28 days or 7.8 % of the year). The safety endpoint was comparison of adverse events between groups.

CONFIRM Results

Localized Sources are Highly Prevalent in Human AF

We found AF sources in 97 % of cases (98 of 101) with sustained AF, each subject demonstrating 2.1±1.0 sources (median 2, interquartile range [IQR] 1–3), of which 70 % were rotors and 30 % focal drivers. The number of simultaneous AF sources was higher in persistent than paroxysmal AF (2.2±1.0 vs 1.7±0.9; median 2.0 vs 1.0; P=0.03). Source numbers were unrelated to duration of AF (r=0.13; P=0.20) or whether patients did or did not have prior conventional ablation (2.0±0.8 vs 2.1±1.1; P=0.71).

Stable AF sources lay at diverse patient-specific locations in the LA (76 %) and RA (24 %). Left atrial sources were found at widespread locations, including sites outside the PVs, as well as the posterior, inferior, and roof regions. RA sources included the inferolateral, posterior, and septal regions but lay away from the superior vena cava.

Total FIRM-guided ablation time at all sources was 16.1± 9.8 minutes (median 18.5, IQR: 7.9–24.5). Total ablation time was similar in both arms since FIRM-ablation time lay within the typical variation of a conventional ablation procedure.

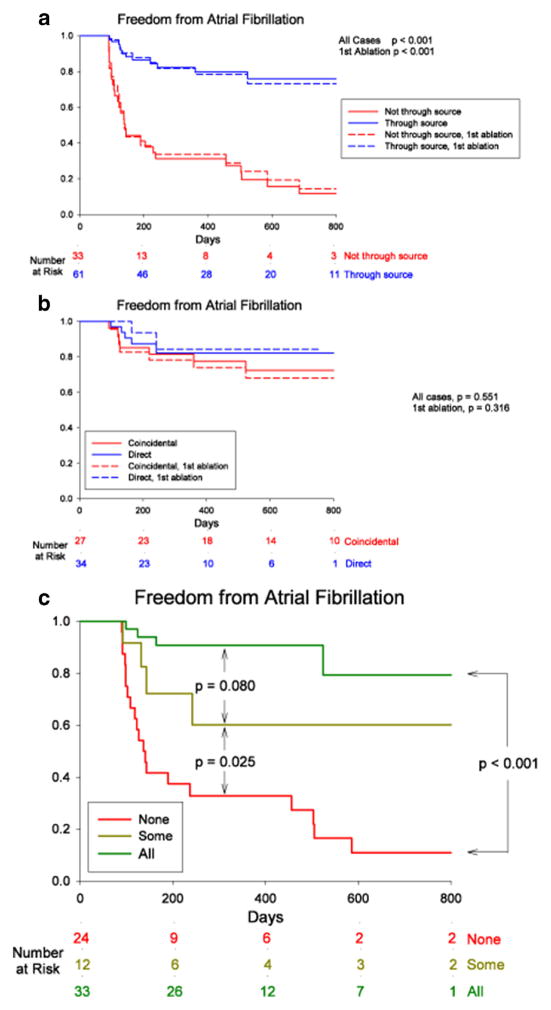

Long-Term Results

By intention-to-treat analysis, freedom from AF after a single procedure was higher for FIRM-guided than conventional ablation (82.4 % vs 44.9 %; P=0.001) after median 273 days (IQR: 132–681 days). Freedom after a single procedure from any atrial tachyarrhythmia was also higher in FIRM-guided than FIRM-blinded cases (70.6 % vs 39.1 %; P=0.003). These results were achieved despite more rigorous follow-up (implantable loop recorders in 88.2 % vs 26.1 %) and more persistent AF (81 % vs 66 %) in FIRM-guided than FIRM-blinded patients.

Recent work shows that the benefits of FIRM-guided over conventional ablation are maintained over 3–4 years of follow-up, as FIRM-guided ablation may prevent late AF recurrence [56].

Finally, multicenter experiences of FIRM ablation in >200 patients at >10 independent laboratories have recently confirmed the acute results of FIRM and long-term results from FIRM-guided ablation [40••, 57].

Relationship of Rotors to Ablation Lesions

Importantly, freedom from AF was higher in patients in whom ablation passed through sources—whether directly or coincidentally—than in those in whom ablation missed all sources. Upon analysis of electroanatomic and FIRM maps in each patient, ablation lesions were deemed to pass through an AF source if ablation lesion markers on the mapping system lay within one-half interelectrode spacing of the electrode targeted as the rotor core. “Source ablation” was defined if ≥1 source was ablated, whether directly by FIRM-guided ablation or coincidentally by anatomic lesion sets (eg, PVI), and assignments were performed independently and blinded to outcomes. Long-term efficacy was higher for patients in source ablation groups than in nonsource ablation groups (P<0.001) [58•]. Freedom from AF was highest when all sources were eliminated, intermediate when some were eliminated, and lowest when all sources were missed (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Cumulative freedom from AF, based on whether (a) ablation did (blue) or did not (red) pass through AF sources, or whether (b) source ablation was direct (FIRM-guided, blue) or coincidental (FIRM-blinded, red). Solid lines represent entire populations and dashed lines first-ablation patients only. (c) Elimination of all (green), some (yellow), or no (red) stable AF sources, in patients with bi-atrial baskets. P values reflect the complete follow-up periods. (Adapted with permission from: Narayan SM, Krummen DE, Clopton P, Shivkumar K, Miller JM. Direct Or Coincidental Elimination of Stable Rotors or Focal Sources May Explain Successful Atrial Fibrillation Ablation: On-Treatment Analysis of the CONFIRM (CONventional ablation for AF with or without Focal Impulse and Rotor Modulation) Trial. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2013) [58•]

This concept was recently tested prospectively in the PRECISE trial (Precise Rotor Elimination without Concomitant pulmonary vein Isolation for the Successful Elimination of Paroxysmal AF), a multicenter single-arm trial of FIRM ablation at sources only (ie, without trigger ablation (PVI)) in patients with paroxysmal AF. Preliminary results from PRECISE showed that FIRM-only ablation provided >80 % elimination of paroxysmal AF [21]. These results strongly support localized sources as a primary mechanism for AF, and provide an alternative paradigm for clinical ablation that is currently being tested in randomized multicenter trials.

Finally, sites of localized rotors/sources do not show a specific electrogram fingerprint, with an inconsistent relationship to complex fractionated atrial electrograms (CFAE) sites [59•]. Even in cases where rotors overlay CFAE, additional sites of more marked CFAE were frequently noted at distant locations.

Limitations of FIRM Mapping and Ablation

CONFIRM and recent confirmatory multicenter studies of FIRM ablation were not randomized, although patients were enrolled, mapped, and treated prospectively for prespecified endpoints. In CONFIRM, the FIRM-guided group had more patients with persistent AF, higher comorbidities, and more intense monitoring than FIRM-blinded patients, thus, potentially underestimating the benefit of FIRM-guided ablation. Second, current baskets may map large atria suboptimally—specifically the septal aspect of the large LA—and it is possible that improved designs may reduce this technical limitation. Third, as with any new technology, interpreting FIRM maps requires a learning curve, although this was relatively short in the recent multicenter experience [57]. Finally, the mechanism(s) by which targeted ablation eliminates rotors is unclear; however, it likely involves the alteration of functional or anatomic tissue properties.

Clinical Implications and Future Studies

The identification of stable rotors in human AF reconciles several clinical observations in the context of previously proposed AF mechanisms. First, despite its complexity AF can be terminated by targeted interventions [31, 32], which supports localized mechanisms in a majority of patients. Second, the observation that human AF is sometimes terminated by anatomic lesions before they are complete, such as pulmonary vein isolation (PVI) or a left atrial roof line, is consistent with stable sources, and is supported by the on-treatment analysis of CONFIRM [58•]. In persistent AF, the diversity of AF source locations provides a mechanism for the efficacy of extensive ablation [58•] that eventually ‘hits’ a source, as opposed to the often cited “reduction in critical mass”, which does not explain AF termination early during ablation.

Conclusions

The AF epidemic necessitates dramatic improvements in treatment and ultimately prevention, which can be achieved only by a thorough understanding of arrhythmia mechanisms. A rapidly growing body of evidence shows that wide field-of-view, physiologic-based mapping (ie, FIRM) identifies electrical rotors in diverse, stable, and patient-specific locations. Ablation of these locations with or without conventional ablation substantially increases single procedure success. These data establish rotors as sustaining mechanisms and, most importantly, show that patient-tailored mechanistic ablation can improve outcomes while reducing unnecessary ablation. Patient-specific mapping of AF-sustaining mechanisms (substrates) is likely to become the future cornerstone of AF therapy, as it has become for essentially all other arrhythmias.

Table 1.

Clinical characteristics of patients in the CONFIRM trial

| Characteristic | Conventional ablation (n=71) | FIRM-guided ablation (n=36) | P |

|---|---|---|---|

| AF presentation | 0.12 | ||

| Paroxysmal | 24 (34 %) | 7 (19 %) | |

| Persistent | 47 (66 %) | 29 (81 %) | |

| Age (y) | 61±8 | 63±9 | 0.34 |

| Gender (male/female) | 68/3 | 34/2 | 1.00 |

| Non-white race | 9 (13 %) | 6 (17 %) | 0.57 |

| History of AF (mos) | 45 (18–79) | 52 (38–110) | 0.04 |

| Left atrial diameter (mm) | 43±6 | 48±7 | 0.001 |

| LVEF (%) | 55±12 | 53±15 | 0.59 |

| CHADS2 score | |||

| 0 or 1 | 38 (54 %) | 13 (36 %) | 0.09 |

| 2 or more | 33 (46 %) | 23 (64 %) | |

| Previously failed >1 AAD | 16 (23 %) | 16 (44 %) | <0.05 |

Values are number (%), mean±SD, or median (interquartile range)

Adapted with permission from: Narayan SM, Krummen DE, Shivkumar K, Clopton P, Rappel W-J, Miller J. Treatment of Atrial Fibrillation by the Ablation of Localized Sources: The Conventional Ablation for Atrial Fibrillation With or Without Focal Impulse and Rotor Modulation: CONFIRM Trial. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2012;60:628–36. [22••]

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grants to S. Narayan from the NIH (HL70529, HL83359, HL103800) and the Doris Duke Charitable Foundation.

Footnotes

Compliance with Ethics Guidelines

Human and Animal Rights and Informed Consent This article does not contain any studies with human or animal subjects performed by any of the authors.

This article is part of the Topical Collection on Invasive Electrophysiology and Pacing

Conflict of Interest Amir A. Schricker and Gautam G. Lalani declare that they have no conflict of interest.

David E. Krummen has received fellowship support from Biosense-Webster, Biotronik, Medtronic, and St. Jude Medical and consultant’s fees from Boston Scientific. Sanjiv Narayan is co-author of intellectual property owned by the University of California Regents and licensed to Topera Inc. Topera does not sponsor any research, including that presented here. S. Narayan holds equity in Topera; has received honoraria and fellowship support from Biotronik, Medtronic, and St. Jude Medical; has received consultant’s fees from the American College of Cardiology and Elsevier; and has received royalties from UpToDate.

References

Papers of particular interest, published recently, have been highlighted as:

• Of importance

•• Of major importance

- 1.Van Gelder IC, Groenveld HF, Crijns HJ, et al. Lenient vs strict rate control in patients with atrial fibrillation. N Engl J Med. 2010;362:1363–73. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1001337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Roy D, Talajic M, Nattel S, et al. Rhythm control vs rate control for atrial fibrillation and heart failure. N Engl J Med. 2008;358:2667–77. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0708789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3•.Saksena S, Slee A, Waldo AL, et al. Cardiovascular outcomes in the AFFIRM Trial (Atrial Fibrillation Follow-Up Investigation of Rhythm Management). An assessment of individual antiarrhythmic drug therapies compared with rate control with propensity score-matched analyses. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2011;58:1975–85. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2011.07.036. This study emphasizes the side-effects from pharmacologic approaches to maintain sinus rhythm, including an increase in hospitalization and mortality compared with ventricular rate control. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4•.Wilber DJ, Pappone C, Neuzil P, et al. Comparison of antiarrhythmic drug therapy and radiofrequency catheter ablation in patients with paroxysmal atrial fibrillation: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2010;303:333–40. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.2029. This landmark multicenter randomized clinical trial shows that catheter ablation for AF, while more effective than anti-arrhythmic drug therapy, yields a 70% multiprocedure efficacy with a lower single procedure efficacy in this study of patients with early paroxysmal AF. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5•.Packer DL, Kowal RC, Wheelan KR, et al. Cryoballoon ablation of pulmonary veins for paroxysmal atrial fibrillation: first results of the North American Arctic Front (STOP AF) pivotal trial. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2013;61:1713–23. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2012.11.064. This multicenter trial confirms that PV isolation using a different energy source (cryoballoon ablation) produces a single-procedure 1 year freedom from AF of ≈58%. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Oral H, Pappone C, Chugh A, et al. Circumferential pulmonary-vein ablation for chronic atrial fibrillation. N Engl J Med. 2006;354:934–41. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa050955. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Morillo C, Verma A, Kuck KH, et al. Radiofrequency Ablation vs Antiarrhythmic Drugs as First-Line Therapy of Atrial Fibrillation (RAAFT 2) trial (abstract) Heart Rhythm. 2012 Abstract. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nielsen JC, Johannessen A, Raatikainen P, et al. Radiofrequency Ablation as Initial Therapy in Paroxysmal Atrial Fibrillation. N Engl J Med. 2012;367:1587–95. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1113566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Calkins CH. 2012 HRS/EHRA/ECAS Expert consensus statement on catheter and surgical ablation of atrial fibrillation: recommendations for patient selection, procedural techniques, patient management and follow-up, definitions, endpoints, and research trial design. Heart Rhythm. 2012;9:632–96. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Parkash R, Tang AS, Sapp JL, Wells G. Approach to the catheter ablation technique of paroxysmal and persistent atrial fibrillation: a meta-analysis of the randomized controlled trials. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. 2011;22:729–38. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-8167.2011.02010.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nattel S. New ideas about atrial fibrillation 50 years on. Nature. 2002;415:219–26. doi: 10.1038/415219a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Allessie MA, Bonke FI, Schopman FJ. Circus movement in rabbit atrial muscle as a mechanism of tachycardia. III. The “leading circle” concept: a new model of circus movement in cardiac tissue without the involvement of an anatomical obstacle. Circ Res. 1977;41:9–18. doi: 10.1161/01.res.41.1.9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Schuessler RB, Grayson TM, Bromberg BI, Cox JL, Boineau JP. Cholinergically mediated tachyarrhythmias induced by a single extrastimulus in the isolated canine right atrium. Circ Res. 1992;71:1254–67. doi: 10.1161/01.res.71.5.1254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14•.Pandit SV, Jalife J. Rotors and the dynamics of cardiac fibrillation. Circ Res. 2013;112:849–62. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.111.300158. This is a contemporary review on the basic science and history of rotors, from the laboratory that has pioneered studies to define their role. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Narayan SM, Krummen DE, Kahn AM, Karasik PL, Franz MR. Evaluating fluctuations in human atrial fibrillatory cycle length using monophasic action potentials. Pacing Clin Electrophysiol. 2006;29:1209–18. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-8159.2006.00525.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Narayan SM, Krummen DE, Rappel WJ. Clinical mapping approach to diagnose electrical rotors and focal impulse sources for human atrial fibrillation. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. 2012;23:447–54. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-8167.2012.02332.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rappel WJ, Narayan SM. Theoretical considerations for mapping activation in human cardiac fibrillation. Chaos. 2013;23:023113. doi: 10.1063/1.4807098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Narayan SM, Bode F, Karasik PL, Franz MR. Alternans of atrial action potentials as a precursor of atrial fibrillation. Circulation. 2002;106:1968–73. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000037062.35762.b4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Narayan SM, Franz MR, Clopton P, Pruvot EJ, Krummen DE. Repolarization alternans reveals vulnerability to human atrial fibrillation. Circulation. 2011;123:2922–30. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.110.977827. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lalani G, Schricker A, Gibson M, Rostamanian A, Krummen DE, Narayan SM. Atrial conduction slows immediately before the onset of human atrial fibrillation: a bi-atrial contact mapping study of transitions to atrial fibrillation. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2012;59:595–606. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2011.10.879. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Narayan SM, Krummen DE, Donsky A, Swarup V, Miller JM. Precise Rotor Elimination without Concomitant pulmonary vein Isolation for the Successful Elimination of Paroxysmal Atrial Fibrillation. PRECISE-PAF. Heart Rhythm. 2013;10:LBCT4. [Google Scholar]

- 22••.Narayan SM, Krummen DE, Shivkumar K, Clopton P, Rappel W-J, Miller J. Treatment of atrial fibrillation by the ablation of localized sources: the Conventional Ablation for Atrial Fibrillation With or Without Focal Impulse and Rotor Modulation: CONFIRM Trial. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2012;60:628–36. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2012.05.022. This study provides the first identification of electrical rotors as sustaining mechanisms for human AF, demonstrating rotors in 97% of patients with paroxysmal, persistent and longstanding persistent AF, where directed ablation (Focal Impulse and Rotor Modulation) improved long-term AF-freedom vs conventional ablation alone on rigorous follow-up. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lazar S, Dixit S, Marchlinski FE, Callans DJ, Gerstenfeld EP. Presence of left-to-right atrial frequency gradient in paroxysmal but not persistent atrial fibrillation in humans. Circulation. 2004;110:3181–6. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000147279.91094.5E. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gerstenfeld EP, Sahakian AV, Swiryn S. Evidence for transient linking of atrial excitation during atrial fibrillation in humans. Circulation. 1992;86:375–82. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.86.2.375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wu T-J, Doshi RN, Huang H-LA, et al. Simultaneous bi-atrial computerized mapping during permanent atrial fibrillation in patients with organic heart disease. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. 2002;13:571–7. doi: 10.1046/j.1540-8167.2002.00571.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sahadevan J, Ryu K, Peltz L, et al. Epicardial mapping of chronic atrial fibrillation in patients: preliminary observations. Circulation. 2004;110:3293–9. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000147781.02738.13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lee G, Kumar S, Teh A, et al. Epicardial wave mapping in human long-lasting persistent atrial fibrillation: transient rotational circuits, complex wavefronts, and disorganized activity. Eur Heart J. 2013;35:86–97. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/eht267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cox JL, Canavan TE, Schuessler RB, et al. The surgical treatment of atrial fibrillation. II. Intraoperative electrophysiologic mapping and description of the electrophysiologic basis of atrial flutter and atrial fibrillation. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 1991;101:406–26. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Davidenko JM, Pertsov AV, Salomonsz R, Baxter W, Jalife J. Stationary and drifting spiral waves of excitation in isolated cardiac muscle. Nature. 1992;355:349–51. doi: 10.1038/355349a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30•.Chou CC, Chang PC, Wen MS, et al. Epicardial ablation of rotors suppresses inducibility of acetylcholine-induced atrial fibrillation in left pulmonary vein-left atrium preparations in a beagle heart failure model. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2011;58:158–66. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2011.02.045. This study reports on mapping rotors in a canine model of AF, with interventions to ablate rotors causing AF suppression. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Herweg B, Kowalski M, Steinberg JS. Termination of persistent atrial fibrillation resistant to cardioversion by a single radiofrequency application. Pacing Clin Electrophysiol. 2003;26:1420–3. doi: 10.1046/j.1460-9592.2003.t01-1-00203.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tzou WS, Saghy L, Lin D. Termination of persistent atrial fibrillation during left atrial mapping. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. 2011;22:1171–3. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-8167.2011.02079.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Haissaguerre M, Hocini M, Shah AJ, et al. Noninvasive panoramic mapping of human atrial fibrillation mechanisms: a feasibility report. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. 2012;24:711–717. doi: 10.1111/jce.12075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sanders P, Berenfeld O, Hocini M, et al. Spectral analysis identifies sites of high-frequency activity maintaining atrial fibrillation in humans. Circulation. 2005;112:789–97. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.104.517011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gerstenfeld E, Sahakian A, Swiryn S. Evidence for transient linking of atrial excitation during atrial fibrillation in humans. Circulation. 1992;86:375–82. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.86.2.375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Moe GK, Rheinboldt WC, Abildskov JA. A computer model of atrial fibrillation. Am Heart J. 1964;67:200–20. doi: 10.1016/0002-8703(64)90371-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Jadidi AS, Cochet H, Shah AJ, et al. Inverse relationship between fractionated electrograms and atrial fibrosis in persistent atrial fibrillation - a combined MRI and high density mapping. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2013 doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2013.03.081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Konings KT, Kirchhof CJ, Smeets JR, Wellens HJ, Penn OC, Allessie MA. High-density mapping of electrically induced atrial fibrillation in humans. Circulation. 1994;89:1665–80. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.89.4.1665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.de Groot NM, Houben RP, Smeets JL, et al. Electropathological substrate of longstanding persistent atrial fibrillation in patients with structural heart disease: epicardial breakthrough. Circulation. 2010;122:1674–82. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.910901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40••.Shivkumar K, Ellenbogen KA, Hummel JD, Miller JM, Steinberg JS. Acute termination of human atrial fibrillation by identification and catheter ablation of localized rotors and sources: first multicenter experience of Focal Impulse and Rotor Modulation (FIRM) ablation. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. 2012;23:1277–85. doi: 10.1111/jce.12000. This study reports the acute results of the first multicenter validation of FIRM mapping to identify rotors and focal sources in human AF. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lin YJ, Lo MT, Lin C, et al. Prevalence, characteristics, mapping, and catheter ablation of potential rotors in nonparoxysmal atrial fibrillation. Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol. 2013;6:851–8. doi: 10.1161/CIRCEP.113.000318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42•.Ghoraani B, Dalvi R, Gizurarson S, et al. Localized rotational activation in the left atrium during human atrial fibrillation: relationship to complex fractionated atrial electrograms and low-voltage zones. Heart Rhythm. 2013;10:1830–8. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2013.09.007. This study reports the acute results of the first multicenter validation of FIRM mapping to identify rotors and focal sources in human AF. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43•.Narayan SM, Wright M, Derval N, et al. Classifying fractionated electrograms in human atrial fibrillation using monophasic action potentials and activation mapping: evidence for localized drivers, rate acceleration, and nonlocal signal etiologies. Heart Rhythm. 2011;8:244–53. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2010.10.020. This study uses detailed monophasic action potential recordings to demonstrate how clinically recorded AF bipolar signals often do not indicate local activation in AF. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kadish A, Hauck J, Pederson B, Beatty G, Gornick C. Mapping of atrial activation with a noncontact, multi-electrode catheter in dogs. Circulation. 1999;99:1906–13. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.99.14.1906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45•.Vaquero M, Calvo D, Jalife J. Cardiac fibrillation: from ion channels to rotors in the human heart. Heart Rhythm. 2008;5:872–9. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2008.02.034. This study uses detailed monophasic action potential recordings to demonstrate how clinically recorded AF bipolar signals often do not indicate local activation in AF. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Zipes DP, Jalife J, editors. Cardiac Electrophysiology from Cell to Bedside. Chapter 107. Philadelphia: Saunders; 2009. Catheter Ablation of Supraventricular Arrhythmias; pp. 1083–1092. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Franz MR, Chin MC, Sharkey HR, Griffin JC, Scheinman MM. A new single catheter technique for simultaneous measurement of action potential duration and refractory period in vivo. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1990;16:878–86. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(10)80336-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Rensma PL, Allessie MA, Lammers WJ, Bonke FI, Schalij MJ. Length of excitation wave and susceptibility to reentrant atrial arrhythmias in normal conscious dogs. Circ Res. 1988;62:395–410. doi: 10.1161/01.res.62.2.395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Calvo D, Atienza F, Jalife J, et al. High-rate pacing-induced atrial fibrillation effectively reveals properties of spontaneously occurring paroxysmal atrial fibrillation in humans. Europace. 2012;14:1560–6. doi: 10.1093/europace/eus180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Nademanee K, McKenzie J, Kosar E, et al. A new approach for catheter ablation of atrial fibrillation: mapping of the electrophysiologic substrate. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2004;43:2044–53. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2003.12.054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Narayan SM, Kazi D, Krummen DE, Rappel W-J. Repolarization and activation restitution near human pulmonary veins and atrial fibrillation initiation: a mechanism for the initiation of atrial fibrillation by premature beats. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2008;52:1222–30. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2008.07.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Krummen DE, Bayer JD, Ho J, et al. Mechanisms of human atrial fibrillation initiation: clinical and computational studies of repolarization restitution and activation latency. Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol. 2012;5:1149–59. doi: 10.1161/CIRCEP.111.969022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Klos M, Calvo D, Yamazaki M, et al. Atrial septopulmonary bundle of the posterior left atrium provides a substrate for atrial fibrillation initiation in a model of vagally mediated pulmonary vein tachycardia of the structurally normal heart. Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol. 2008;1:175–83. doi: 10.1161/CIRCEP.107.760447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Lalani G, Gibson M, Schricker A, Rostamanian A, Krummen DE, Narayan SM. Dynamic conduction slowing precedes human atrial fibrillation initiation: insights from bi-atrial basket mapping during burst pacing. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2011b [Google Scholar]

- 55.Ganesan AN, Kuklik P, Lau DH, et al. Bipolar electrogram shannon entropy at sites of rotational activation: implications for ablation of atrial fibrillation. Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol. 2013;6:48–57. doi: 10.1161/CIRCEP.112.976654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Narayan SM, Baykaner T, Clopton P, Schricker A, Lalani GG, Krummen DE, et al. Ablation of rotor and focal sources reduces late recurrence of atrial fibrillation compared with trigger ablation alone: extended follow-up of the CONFIRM trial (Conventional Ablation for Atrial Fibrillation With or Without Focal Impulse and Rotor Modulation) J Am Coll Cardiol. 2014;63(17):1761–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2014.02.543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Miller JM, Kowal RC, Swarup V, Daoud E, Day J, Ellenbogen K, et al. Initial Independent Outcomes from Focal Impulse and Rotor Modulation Ablation for Atrial Fibrillation: Multicenter FIRM Registry. J Cardiovascular Electrophysiology. 2014 doi: 10.1111/jce.12474. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58•.Narayan SM, Krummen DE, Clopton P, Shivkumar K, Miller JM. Direct or coincidental elimination of stable rotors or focal sources may explain successful atrial fibrillation ablation: on-treatment analysis of the CONFIRM (CONventional ablation for AF with or without Focal Impulse and Rotor Modulation) Trial. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2013:58–67. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2013.03.021. This study shows that rotor ablation – whether performed directly by FIRM or unintentionally during conventional anatomic ablation lesions—greatly improves outcomes compared with ablation that does not pass through rotors. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59•.Narayan SM, Shivkumar K, Krummen DE, Miller JM, Rappel W-J. Panoramic electrophysiological mapping but not individual electrogram morphology identifies sustaining sites for human atrial fibrillation (af rotors and focal sources relate poorly to fractionated electrograms) Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol. 2013;6 doi: 10.1161/CIRCEP.111.977264. This study shows that localized AF sources—where the rotor core or focal source demonstrates spatial precession—is not well correlated with bipolar electrogram amplitude or traditionally defined fractionation. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Narayan SM, Krummen DE, Enyeart MW, Rappel WJ. Computational mapping identifies localized mechanisms for ablation of atrial fibrillation. PLoS One. 2012;7:e46034. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0046034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]