Abstract

The full-length gene encoding the histone deacetylase (HDAC)-like amidohydrolase (HDAH) from Bordetella or Alcaligenes (Bordetella/Alcaligenes) strain FB188 (DSM 11172) was cloned using degenerate primer PCR combined with inverse-PCR techniques and ultimately expressed in Escherichia coli. The expressed enzyme was biochemically characterized and found to be similar to the native enzyme for all properties examined. Nucleotide sequence analysis revealed an open reading frame of 1,110 bp which encodes a polypeptide with a theoretical molecular mass of 39 kDa. Interestingly, peptide sequencing disclosed that the N-terminal methionine is lacking in the mature wild-type enzyme, presumably due to the action of methionyl aminopeptidase. Sequence database searches suggest that the new amidohydrolase belongs to the HDAC superfamily, with the closest homologs being found in the subfamily assigned acetylpolyamine amidohydrolases (APAH). The APAH subfamily comprises enzymes or putative enzymes from such diverse microorganisms as Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Archaeoglobus fulgidus, and the actinomycete Mycoplana ramosa (formerly M. bullata). The FB188 HDAH, however, is only moderately active in catalyzing the deacetylation of acetylpolyamines. In fact, FB188 HDAH exhibits significant activity in standard HDAC assays and is inhibited by known HDAC inhibitors such as trichostatin A and suberoylanilide hydroxamic acid (SAHA). Several lines of evidence indicate that the FB188 HDAH is very similar to class 1 and 2 HDACs and contains a Zn2+ ion in the active site which contributes significantly to catalytic activity. Initial biotechnological applications demonstrated the extensive substrate spectrum and broad optimum pH range to be excellent criteria for using the new HDAH from Bordetella/Alcaligenes strain FB188 as a biocatalyst in technical biotransformations, e.g., within the scope of human immunodeficiency virus reverse transcriptase inhibitor synthesis.

Class 1 and 2 histone deacetylases (HDACs) (19), acetoin utilization proteins, and acetylpolyamine amidohydrolases (APAH) are members of the same superfamily (17) and may very well descend from a common ancestor (14). Sequence comparison reveals that all three classes of proteins share a number of common motifs. Additionally, they show significant functional similarities such as recognition of acetylated aminoalkyl groups and the removal of the acetyl moiety by cleaving an amide bond. Interestingly, the biological role of APAH is still a matter of speculation, although these enzymes are thought to be involved in degradative pathways of polyamines (20), particularly in the deacetylation of acetylpolyamines (23). However, experimental evidence to support this idea is still rather scarce. To date, only the APAH from Mycoplana ramosa has been described in detail. While some APAH were reported to cleave only acetylputrescine in vitro, M. ramosa APAH was described as less specific in the same experiments (23). Besides having a role in the degradative pathways of polyamines, APAH could, in principle, also be involved in the regulation of other cellular processes (7), e.g., through the modification of proteins. Indeed, our data along with two recent findings by other groups indicate that not only eukaryotes but also eubacteria (22) and archaea (3) contain proteins with biological activities that are eventually regulated through ɛ-acetylation of lysine residues. In Escherichia coli, deacetylation of the chemotaxis response regulator protein CheY affects signal generation (22). In the archaeon Sulfolobus solfataricus P2 (3), deacetylation of the acetylated form of the DNA-binding protein Alba is realized by Sir2, a protein belonging to the Sir class of HDACs unrelated to members of the HDAC superfamily such as the one described herein.

Here, we describe the cloning, nucleotide sequence, and overexpression as well as the characterization of a novel HDAC-like amidohydrolase (HDAH) from Bordetella or Alcaligenes (Bordetella/Alcaligenes) strain FB188 (DSM 11172). This FB188 HDAH was isolated in an industrial screening program for new biocatalysts that could be used to synthesize cis-(1S,4R)-(4-aminocyclopent-2-enyl) methanol (AA), a precursor substance in the synthesis of human immunodeficiency virus-reverse transcriptase inhibitor abacavir (13). The new FB188 HDAH gene is organized very similarly to the APAH gene (aphA) from M. ramosa. In contrast to the homologous APAH from M. ramosa, however, the novel FB188 HDAH is a monomer. Furthermore, this FB188 HDAH is a Zn2+-dependent protein deacetylase rather than an APAH. Preliminary results indicate that the FB188 HDAH recognizes an acetylated 65-kDa protein from Bordetella/Alcaligenes strain FB188 (DSM 11172) as a target of deacetylation.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains, plasmids, and oligonucleotides.

E. coli strains XL1-Blue and BL21 were purchased from Stratagene (La Jolla, Calif.). Alcaligenes/Bordetella species FB188 (DSM 11172) was obtained from Lonza AG (Visp, Switzerland). Methanosarcina mazei was a kind gift from R. Schmitz-Streit (University of Goettingen, Goettingen, Germany). Plasmids pUC19 and pBluescript were purchased from Stratagene. Plasmid pQEB-MCS was described previously (21). Plasmid preparations were performed using QIAprep (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany). Oligonucleotide primers were obtained from Metabion GmbH (Martinsried, Germany). Oligonucleotide sequences are listed in Table 1.

TABLE 1.

Oligonucleotide primers used in this study

| Primer | Sequencea |

|---|---|

| BOCA3I | 5′-GAYGGIATHACIATGATGGG-3′ |

| BOCA5B | 5′-CCRCARAANGGNAGRTARTG-3′ |

| Lon1B | 5′-CGGAATTCCGGATCCAGCATGCTGGCATCGAA-3′ |

| Lon2A | 5′-GCGAATTCGGATCCGCTGGCGCGCATGAT-3′ |

| PQEB-RV | 5′-AATTCAAGCTTATCAGCGGATATCCGCCAGCAG-3′ |

| PQEB-FW | 5′-CTGAATTCATTAAAGAGGAGAAATTAAGCATGGCCATCGGATATGTTTGG-3′ |

| PQEB-(N-His)FW | 5′-CTGAATTCATTAAAGAGGAGAAATTAAGCATGCATCACCATCACCATCACGCCATCGGATATGTTTGG-3′ |

N = A, G, C, or U; Y = U or C; H = T, C, or A; R = A or G; I = inosine.

Materials.

Restriction enzymes and T4 DNA ligase were purchased from MBI Fermentas (St. Leon-Rot, Germany), and AmpliTaq was from Perkin-Elmer (Boston, Mass.). Rat liver HDAC was obtained from Calbiochem (Bad Soden, Germany). AMC (7-amino-4-methyl-coumarin) was from Avocado (ABCR, Karlsruhe, Germany). Acetylchloride and propionylchloride were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (Deisenhofen, Germany). Boc-Lys(ɛ-acetyl)-4-methyl-coumaryl-7-amide (MCA) was prepared as described previously (10). Z-His-Arg-Lys(ɛ-acetyl)-MCA, Ac-Arg-Gly-Lys(ɛ-acetyl)-MCA, Ac-Gly-Ala-Lys(ɛ-acetyl)-MCA, Tos-Gly-Pro-Lys(ɛ-acetyl)-MCA, and Ac-Gly-Gly-Lys(ɛ-acetyl)-MCA were synthesized as published previously (30). Rabbit antiserum against the keyhole limpet hemocyanin-coupled N-terminal 15-mer peptide of the FB188 amidohydrolase was obtained from Eurogentec (Cologne, Germany). Prior to use it was incubated with total protein from E. coli BL21 for 5 min at room temperature (RT) followed by centrifugation for 10 min at 15,000 rpm (Biofuge; Hereaus-Kendro, Osterode, Germany) at RT. The supernatant was taken for further experiments. Suberoylanilide hydroxamic acid (SAHA) and its carboxylic acid analogue were prepared as described previously (27).

Screening for NAA-degrading microorganisms.

A sample of wastewater was enriched on liquid medium and on agar plates containing cis-(±)-N-[4-(hydroxymethyl)cyclopent-2-enyl]acetamide (NAA) as a single carbon source. Microbial growth or colonies appeared after 48 h of incubation at 37°C. Concomitant strains were characterized by the Deutsche Sammlung von Mikroorganismen und Zellkulturen GmbH. One strain (FB188; DSM 11172) was classified (mainly by partial 16S ribosomal DNA sequencing and fatty acid analysis) as belonging to the Alcaligenes/Bordetella group.

Purification of the amidohydrolase from FB188.

FB188 was aerobically grown overnight in 10 liters of medium A [78.7 mM MgCl2, 3.95 mM CaCl2, 0.118 mM FeCl3, 15.4 mM (NH4)2SO4, 14.1 mM Na2HPO4, 7.3 mM KH2PO4, 34.2 mM NaCl, 1 ml of vitamin stock solution (25), and a final concentration of 10 mM NAA]. Cells were harvested by centrifugation, resuspended in 50 mM Tris-HCl buffer (pH 8.0), and disrupted using a French press (16,000 to 20,000 lb/in2). The homogenate was centrifuged at 15,000 × g for 30 min at RT. A total of 3,000 ml of cell extract containing 23.25 g of protein was loaded onto a Poros 50 HQ column (Perseptive Biosystems, Clearwater, Fla.) (column volume, 500 ml; capacity, 25 g of protein) equilibrated with 50 mM Tris buffer containing 1 mM dithiothreitol (DTT), pH 8.0. The column was washed with the same buffer, and the bound proteins were eluted with a linear gradient (0 to 100%) of 50 mM Tris buffer containing 1 mM DTT and 1 M NaCl (pH 7.0) in 3,000 ml at a flow rate of 10 ml/min. Active fractions from this column were pooled, diluted with 50 mM Tris buffer containing 1 mM DTT (pH 8.5) until the NaCl concentration was less than 50 mM, and loaded onto a Q-Sepharose HiLoad 26/10 column (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech AG, Freiburg, Germany) equilibrated with the same buffer. After being washed with this buffer followed by a linear gradient ranging from 0 to 20% of 50 mM Tris buffer containing 1 mM DTT and 1 M NaCl (pH 8.5) in 150 ml, the bound proteins were eluted with a linear gradient of 20 to 50% of the same buffer in 600 ml at a flow rate of 5 ml/min. A 2-ml aliquot of the pooled, concentrated fractions (protein concentration, 27.2 mg/ml) was loaded onto a Sephacryl S-100 HR column (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech AG) (column volume, 100 ml; void volume, 25 ml; capacity, 11 ml) equilibrated with 50 mM Tris buffer containing 100 mM NaCl and 1 mM DTT, pH 8.5. The flow rate was 0.5 ml/min. The active fractions were pooled, and the buffer was exchanged to 10 mM potassium phosphate, pH 6.8. From this, 3 ml was loaded onto a Bio-Scale CHT5-1 hydroxyapatite column (Bio-Rad Laboratories AG, Reinach, Switzerland) equilibrated with 10 mM potassium phosphate buffer containing 1 mM DTT (pH 6.8). The amidohydrolase was eluted by washing with 10 ml of the same buffer at a flow rate of 0.3 ml/min and loaded onto a Uno Q column (Bio-Rad Laboratories AG) (column volume, 1.3 ml; capacity, 20 mg of protein) equilibrated with the same buffer. After washing with the same buffer, bound proteins were eluted with a linear gradient (0 to 30%) of Tris buffer containing 1 mM DTT and 0.5 M NaCl (pH 6.5) in 30 ml. The flow rate was 1 ml/min. Active fractions that were still slightly impure after this step were run a second time on this column, in which case they were first diluted with 50 mM Tris buffer containing 1 mM DTT (pH 7.5) to reduce the NaCl concentration and to achieve the appropriate pH value. The final enzyme preparation proved to be pure according to sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) analysis (see Fig. 5).

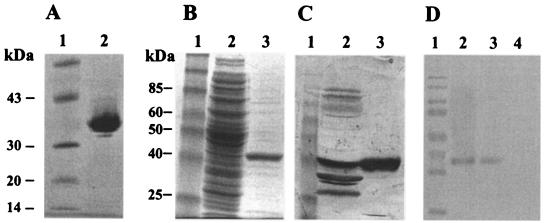

FIG. 5.

SDS gel electrophoretic analysis of cell lysates and purified enzyme fractions. (A) Native FB188 HDAH purified from Bordetella/Alcaligenes strain FB188 (DSM 11172). Lane 1, protein marker (purified FB188 HDAH prior to amino acid sequence analysis). (B) FB188 HDAH purified by IMAC from E. coli BL21 harboring pQEB-AH-NHis. A benchmark prestained protein ladder (Gibco-Life Science, Karlsruhe, Germany) (lane 1), crude cell extract (lane 2), and purified protein (lane 3) were fractionated on an SDS-10% polyacrylamide gel. Protein bands were visualized by Coomassie staining. (C) Western blotting using the anti-AHFB188 antibody (lanes are as described for panel B). (D) Western blot analysis of FB188 crude cell extract with anti-AHFB188 antibody. Lane 1, benchmark prestained protein ladder; lane 2, purified recombinant FB188 HDAH; lane 3, FB188 cell extract; lane 4, E. coli XL1-Blue cell extract.

Amino acid sequence analysis.

Purified amidohydrolase was subjected to protein sequence analysis (Edman sequencing and mass spectrometry) using standard methods (18). Internal peptides were obtained by trypsin digestion and high-pressure liquid chromatography purification prior to direct sequencing using an automatic gas-phase sequencer (catalog no. 470A; Applied Biosystems, Weiterstadt, Germany).

Preparation of genomic DNA and Southern blot analysis.

Genomic DNA was prepared according to standard methods (24). A total of 10 to 50 μg of genomic DNA was used for endonuclease digestion with PstI, KspI, DraII, EcoRI, or combinations of the enzymes. Digested DNA was ethanol precipitated, and DNA fragments were separated by agarose gel electrophoresis. Southern blot analysis was carried out according to standard methods (24) using an EcoRI fragment from pBOCA3.5 radioactively labeled with [γ-32P]ATP as a probe.

PCR amplification and cloning of the amidohydrolase gene.

Genomic DNA (50 μg) was digested with 20 U of PstI in the appropriate buffer (0+) (MBI Fermentas). DNA fragments were separated by electrophoresis on an agarose gel and visualized by ethidium bromide staining. DNA bands of approximately 2.4 to 2.6 kb in length were cut out with a sharp razor blade. The DNA was recovered using a Qiagen extraction kit. About 0.2 μg of the DNA was circularized in a 10-μl ligation reaction mixture as described previously (5). Different aliquots of the ligation reaction mixture were used directly as a template in subsequent standard PCRs using AmpliTaq along with Lon1B and Lon2A as primers. PCR products were analyzed by agarose gel electrophoresis. Two products (800 and 2,300 bp) could be traced. The 2,300-bp product was extracted from the gel with a Qiagen extraction kit. The PCR product was digested with EcoRI and ligated into an EcoRI-digested plasmid (pUC19). The insert was then subjected to automated sequence analysis using an ABI 373A apparatus.

Sequence analysis of the amidohydrolase gene.

BlastP (P < 2e-09) (1) was used to search the nonredundant peptide sequence database at the National Center for Biotechnology Information for proteins similar to FB188 amidohydrolase. A multiple alignment has been produced as published by Leipe and Landsman (17) with DNasis software. RNA secondary structure prediction was based on algorithms provided by Vienna RNA software (9).

Expression and purification of recombinant amidohydrolase.

The DNA sequence of the full-length gene was amplified using either primers PQEB-RV and PQEB-FW or primers PQEB-RV and PQEB-(N-His)FW (see Table 1), with FB188 genomic DNA as a template. The PCR products were double digested with EcoRI/HindIII and ligated into an EcoRI/HindIII double-digested plasmid (pQEB-MCS) (21). The constructs were used to transform E. coli strains XL1-Blue and BL21. The identities of all constructs were confirmed by automated sequence analysis using an ABI 373A apparatus.

For gene expression studies, BL21 clones were grown in medium A with or without 1 mM NAA as the single C source. At an optical density of 0.8 at 600 nm, the cells were collected by centrifugation. The pellet was washed twice with 100 mM sodium phosphate (pH 7.0). After the cells were resuspended in the same buffer, the suspension was sonified 3 times for 30 s at 0°C. Cell debris was collected by centrifugation, and the supernatant was subjected to immobilized-metal-ion affinity chromatography (IMAC) with Ni2+ (as described by the supplier) (Qiagen) and an imidazole gradient. Alternatively, an IMAC procedure with Zn2+ was used. In each case, fractions containing active enzyme (as judged by the hydrolysis of NAA) were pooled and dialyzed with three changes of 50 mM sodium phosphate (pH 7.5). Aliquots were analyzed by SDS--10% PAGE to reveal a purity of >95%. Protein concentration was estimated according to the method of Bradford (4), with bovine serum albumin as a standard. The final concentration was 0.800 mg/ml, and the total yield was 1 mg of protein. Western blotting analysis was performed according to standard protocols (24).

Assays for amidohydrolase activity.

Enzyme activity was measured in four different assays. First, acetate enzymatically released from acetylputrescine, acetylcadaverine, or acetylspermidine by APAH-like activity was quantified by monitoring the absorption of NADH+ at 340 nm with an acetic acid standard test (catalog no. 148261; Roche Diagnostics, Mannheim, Germany) as suggested previously (2). Briefly, acetate is converted in the presence of acetyl-coenzyme A (CoA) synthetase with ATP and CoA to acetyl-CoA. The latter reacts with oxaloacetate to citrate in the presence of citrate synthetase. The oxaloacetate required for this reaction is formed from l-malate and NAD in the presence of l-malate dehydrogenase upon reduction of NAD to NADH+. As a buffer, 100 mM sodium phosphate (pH 7.5) was used.

Second, a two-step fluorogenic HDAC assay was carried out with peptidic substrate Boc-Lys(ɛ-acetyl)-MCA (see Fig. 6) as described previously (29, 30). In the first reaction catalyzed by the FB188 enzyme, acetate is released from ɛ-acetylated lysine moieties. In the second reaction, the deacetylated peptide is recognized as a substrate by trypsin, which cleaves only after deacetylated lysine residues. The release of AMC was monitored by measuring the fluorescence at 460 nm (λex = 390 nm) with the help of a robotic workstation (CyBi-Screen-Machine; CyBio AG, Jena, Germany) including a Polarstar fluorescence reader (BMG, Offenburg, Germany). Fluorescence intensity was calibrated using free AMC. Alternative pH values or additions of different salts were used in the first step of the assay as indicated. To analyze substrate specificities of the enzyme, the assay was also carried out with Z-His-Arg-Lys(ɛ-acetyl)-MCA, Ac-Arg-Gly-Lys(ɛ-acetyl)-MCA, Ac-Gly-Ala-Lys(ɛ-acetyl)-MCA, Tos-Gly-Pro-Lys(ɛ-acetyl)-MCA, and Ac-Gly-Gly-Lys(ɛ-Ala)-MCA as substrates. With these tripeptide substrates, a novel protocol was used (29).

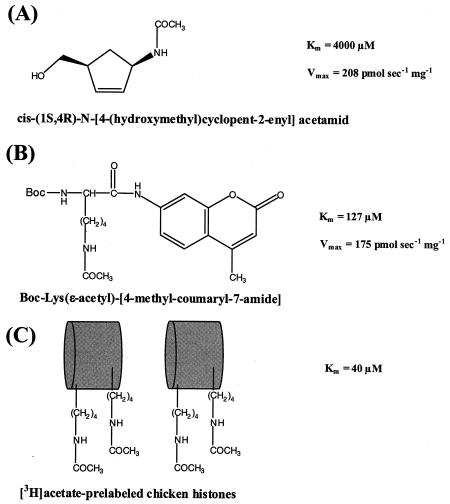

FIG. 6.

Substrates of the FB188 HDAH. Km and Vmax values were measured using different assays and the Ni-IMAC-purified enzyme. (A) Deacetylation of NAA was characterized using a standard fluorescamine assay (28). (B) For Boc-Lys(ɛ-acetyl)-MCA, the two-step HDAC assay was used (30). (C) The deacetylation of [3H]acetate-prelabeled chicken histones was analyzed as described previously (16).

Third, HDAC activity was determined using [3H]acetate-prelabeled chicken histones as described previously (16). Released radioactive acetate was extracted with ethyl acetate, and the organic phase was counted for radioactivity in a liquid scintillation cocktail.

Finally, deacetylation of NAA (see Fig. 6) was monitored in an assay based on the reaction of fluorescamine with primary amino groups (28). In a final volume of 100 μl, 2 μl of enzyme in 100 mM phosphate buffer (pH 7.5) was incubated at 37°C for 30 min, with a final concentration of 1 to 2,500 mM NAA. Subsequently, a 90-μl aliquot was transferred into the well of a microplate and mixed with 10 μl of 0.3% fluorescamine in acetone. After 3 min at RT, fluorescence was measured at a wavelength of 460 nm (λex = 390 nm). This fourth type of assay was used throughout the purification of the enzyme to monitor enzymatic activity in fractions of eluates.

Western blot analysis of total soluble protein from FB188.

Lysates from E. coli XL1-Blue (Stratagene), FB188, and M. mazei were obtained using a combination of a French press (SLM Instruments, Urbana, Ill.) and a sonifier (Branson, Heusenstamm, Germany). Lysates were centrifuged for 10 min at 4°C, and the supernatants were stored at 4°C until analysis. Aliquots of the supernatants were treated for 1 h at 37°C with 0.2 μg of purified recombinant FB188 amidohydrolase/μl. Equal amounts of amidohydrolase-treated or untreated total cellular protein were loaded and electrophoresed on SDS-polyacrylamide gels, and the separated proteins were transferred onto an Immobilon-P membrane (Millipore, Eschborn, Germany). An acetylated proteins antibody (ab193; Abcam, Cambridge, United Kingdom) was used that recognizes the ɛ-acetyl-lysine residue as an epitope and cross-reacts with a variety of acetylated proteins (acetylated proteins antibody [ab193] data sheet; Abcam, 1998). Immune complexes were detected with phosphatase-conjugated anti-rabbit immunoglobulin G (catalog no. A-8025; Sigma, Taufkirchen, Germany) and 5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolyl phosphate as a substrate.

Nucleotide sequence accession number.

The nucleotide sequence of the amidohydrolase gene from FB188 and the encoded amino acid sequence have been deposited in the EMBL nucleotide database under accession number AJ580773.

RESULTS

Amino acid sequence analysis of the FB188 HDAH.

Purified HDAH was subjected to protein sequence analysis. Direct analysis of the N terminus yielded the peptide N terminus (AIGYVWNTLYGWVDTGTGSLAAANL). Thus, the N-terminal peptide did not start with a methionine. For further analysis, two internal sequences were obtained after generation of peptides by trypsin digestion and high-pressure liquid chromatography purification, yielding peptide sequences T-7 (VSNLPTGGDTGDGITMMGNGGLEIAR) and T-16 (IVFVQEGGYSPHYLPFCGLAVIEELTGVR).

Cloning of the HDAH gene from FB188.

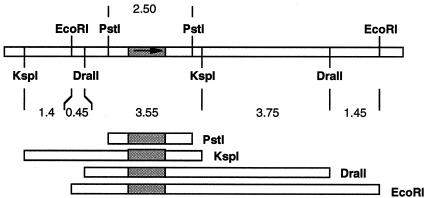

Two degenerated primers (see Table 1), BOCA3I and BOCA5B, were designed according to the amino acid sequences of peptides T-7 and T-16. PCR using these primers and FB188 genomic DNA as a template revealed a 675-bp product. The PCR product was fused to EcoRI linkers, digested with EcoRI, and ligated into an EcoRI-digested plasmid, pBluescript, generating plasmid pBOCA3.5. Sequencing of the pBOCA3.5-insert revealed gene sequences extending the primer sequences into T-7 and T-16 encoding sequences, as expected. The EcoRI fragment radioactively labeled with [γ-32P]ATP was used as a probe in Southern blot analysis to identify complementary genomic DNA restriction fragments. Separate digestions of genomic DNA by EcoRI, DraII, KspI, and PstI each revealed a single band of 9.2, 7.3, 5.4, and 2.5 kb, respectively. Additionally, double digests with the aforementioned restriction endonucleases were carried out to reveal a map of the coding region (Fig. 1). PstI fragments (2.4 to 2.6 kb) of genomic DNA were then isolated from an agarose gel. The DNA was circularized and used as a template for inverse PCR (5) using Lon1B and Lon2A (see Table 1) as primers. A 2,300-bp PCR product was digested with EcoRI and ligated into an EcoRI-digested plasmid pUC19. The insert was then subjected to automated sequence analysis using an ABI 373A apparatus. Two primers (PQEB-RV and PQEB-FW; see Table 1) were designed on the basis of the obtained sequence and used to amplify the full-length gene by PCR with genomic FB188 DNA as a template. The PCR product was ligated into plasmid pQEB-MCS (21), and the construct was used to transform E. coli strain XL1-Blue. Out of 10 clones analyzed, two clones (pQEB-AH6.6 and pQEB-AH6.8) carried the correct insertion, as confirmed by automated sequence analysis. Alternatively, primers PQEB-RV and PQEB-(N-His)FW were used to amplify the gene containing an additional N-terminal His tag. Cloning of the extended gene into plasmid pQEB-MCS and subsequent transformation of E. coli strain BL21 revealed clone pQEB-AH-NHis. The correct insertion was confirmed by automated sequence analysis.

FIG. 1.

Restriction map of the chromosomal DNA fragment from FB188 which carries the HDAH gene. EcoRI, DraII, KspI, and PstI each revealed a single band hybridizing with the pBOCA3.5 probe. The region of DNA sequence analysis tallies with the PstI fragment. The HDAH open reading frame is depicted as a gray-shaded box with an arrow pointing from the start to the stop codon.

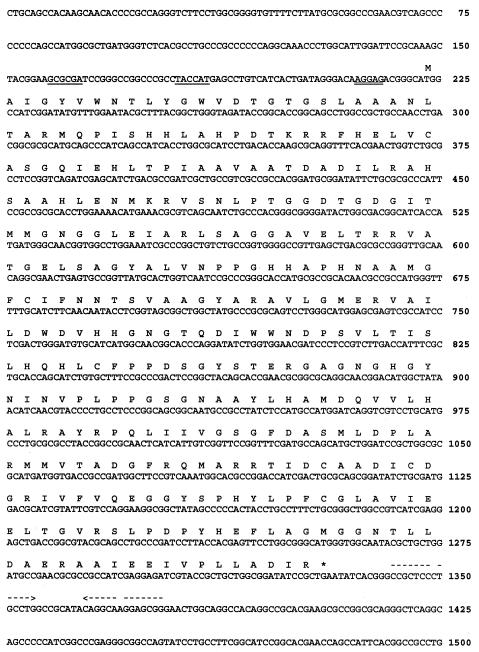

In Fig. 2, the complete nucleotide sequence of the amidohydrolase gene is depicted, starting with the upstream PstI site. The 1,110-bp open reading frame encodes a protein of 369 amino acids with a calculated molecular mass of 39.421 kDa, which is in rather good agreement with the value of approximately 35 kDa estimated by SDS-PAGE and by gel filtration experiments (data not shown).

FIG. 2.

Nucleotide and deduced amino acid sequences of the HDAH gene. The first 1,500 bp from the PstI fragment of the genomic DNA are shown. A putative promoter sequence is underlined; the putative RBS is double underlined. A long inverted repeat is indicated by arrows.

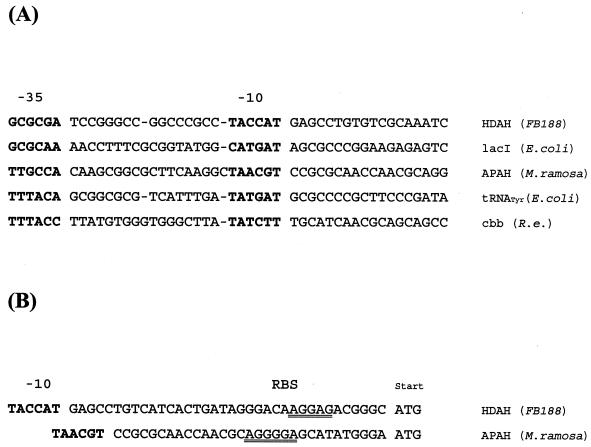

The analysis of the sequence upstream of the ATG triplet revealed significant sequence homology to the respective region of the M. ramosa gene (Fig. 3). A putative ribosomal binding site (RBS) was located 8 bp of nucleotides upstream of the start codon (Fig. 3B). In addition, sequence comparison with known bacterial promoters revealed a promoter-like sequence upstream of the putative RBS (Fig. 3A). The sequence (5′-GCGCGA-16bp-TACCAT-3′) closely resembles the E. coli lacI promoter sequence (5′-GCGCAA-16bp-CATGAT-3′) and exhibits some similarity to the promoter sequence (5′-TTTACC-16bp-TATCTT-3′) of the cbb operon from Ralstonia eutropha H16 (formerly Alcaligenes eutrophus). Analysis of the sequence downstream of the stop codon revealed a long inverted-repeat sequence, which was predicted by RNA secondary structure analysis (9) to form a stable hairpin loop in the context of the concomitant mRNA and thus may act as a transcription terminator. A similar observation was reported for the aphA gene of M. ramosa (23).

FIG. 3.

Sequence comparison of putative regulatory elements. (A) Structure of the promoter region from the HDAH gene of FB188, E. coli lacI, M. ramosa aphA, E. coli tRNATyr, and R. eutropha cbbL [cbb (R.e.)]. (B) Putative ribosomal binding sequences (underlined) of M. ramosa aphA and the FB188 genes.

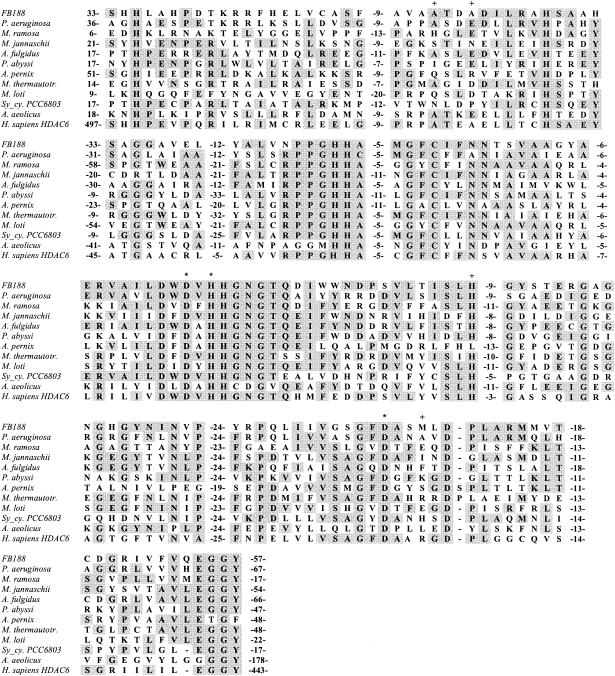

With all the data taken together, the FB188 enzyme fits very well in the group of so-called APAH of the HDAC superfamily (Fig. 4), with the most significant sequence homologies to the putative enzymes from Pseudomonas aeruginosa (47% identity over 328 residues) and Archaeoglobus fulgidus (41% identity over 221 residues). It shares 35% identity over 291 residues with human HDAC6, a putative tubulin deacetylase (32).

FIG. 4.

Multiple sequence alignment of the regions of significant similarity in APAH, FB188 HDAH, and human HDAC6. Consensus residues are indicated in shaded boxes. Numbers between dashes indicate the numbers of residues that have been omitted to improve the alignment as proposed by Leipe and Landsman (17). The following sequences are included in the alignment: HDAH (FB188), HDAH from Bordetella/Alcaligenes FB188; APAH (P. aeruginosa), putative APAH from proteobacterium P. aeruginosa; APAH (M. ramosa), APAH from proteobacterium M. ramosa; APAH (M. jannaschii), putative APAH from archaeon M. jannaschii; APAH (A. fulgidus), putative APAH from A. fulgidus; APAH (“Pyrococcus abyssi”), putative APAH from “P. abyssi”; APAH (Aeropyrum pernix), putative APAH from A. pernix; APAH (M. thermautotr.), putative APAH from M. thermautotrophicus; APAH (Mesorhizobium loti), putative APAH from M. loti; APAH (Sy_cy. PCC6803), putative APAH from cyanobacterium Synechocystis sp. strain PCC6803; APAH (A. aeolicus) APAH from A. aeolicus; HDAC6 from H. sapiens (AF132609_1). The positions of putative zinc-binding amino acids in the M. ramosa enzyme (+) according to Sakurada et al. (23) and zinc-coordinating amino acids (*) in the structure of the A. aeolicus enzyme (6) are marked.

Expression of the FB188 HDAH in E. coli.

E. coli strain BL21 harboring pQEB-AH6.6, pQEB-AH6.8, or pQEB-AH-NHis produced the FB188 HDAH in the presence of IPTG (isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside), suggesting that expression was driven by the lac promoter on the vector. From 1 liter of bacterial culture of BL21/pQEB-AH-Nhis, about 1 mg of pure enzyme was obtained after IMAC purification (Fig. 5B and C). For the His-tagged recombinant HDAH, an apparent molecular mass of 40 kDa was estimated by SDS-PAGE. A protein of similar size was also identified in FB188 crude extract by Western blot analysis with an anti-AHFB188 antibody (Fig. 5D), indicating that the full-length gene had indeed been cloned.

Properties of the FB188 HDAH.

The purified recombinant enzyme was first characterized in terms of substrate specificity. As already expected from the selection procedure that yielded strain FB188, NAA (Fig. 6) proved to be a good substrate for HDAH from strain FB188. For this substrate, the Km and Vmax values were determined to be 4,000 μM and 208 pmol s−1 mg−1, respectively. In contrast, the (1R,4S)-enantiomer was cleaved at a >100-fold-reduced rate (data not shown).

To shed some light on the biological role of this enzyme, we first examined its APAH activity in a coupled assay. In a first step, enzymatic hydrolysis of acetylpolyamine was carried out. In a second step, the released acetate was determined in a standard acetate assay. With acetylputrescine, acetylcadaverine, and acetylspermidine as substrates, 1 mg of the FB188 HDAH was able to cleave 0.66, 0.48, and 0.24 μmol, respectively, in 1 h; these values compare to Vmax values of 29.1, 28, and 17.4 μmol min−1 mg−1 (Km of 0.19, 0.08, and 0.25 mM), respectively, for the enzyme from M. ramosa (23). This suggests a biological role of the FB188 HDAH different from that of the APAH from M. ramosa.

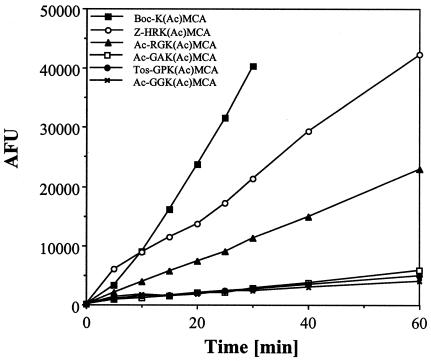

Since the FB188 enzyme exhibited significant sequence similarities with HDACs, we next used standard HDAC assays to investigate any acetylprotein deacetylase activity. Interestingly, peptidic HDAC substrates proved to be substrates for the FB188 HDAH. For Boc-Lys(ɛ-acetyl)-MCA (Fig. 6), the Km and Vmax values were determined to be 127 ± 24 μM and 175 ± 20 pmol s−1 mg−1, respectively, compared to 3.7 ± 1.7 μM and 4.41 ± 0.10 pmol s−1 mg−1 (30) for rat liver HDAC. To further characterize the sequence specificity of the enzyme, time-dependent cleavage reactions were carried out for different peptidic substrates, including Z-His-Arg-Lys(ɛ-acetyl)-MCA, Ac-Arg-Gly-Lys(ɛ-acetyl)-MCA, Ac-Gly-Ala-Lys(ɛ-acetyl)-MCA, Tos-Gly-Pro-Lys(ɛ-acetyl)-MCA, and Ac-Gly-Gly-Lys(ɛ-acetyl)-MCA (Fig. 7). Here, Z-His-Arg-Lys(ɛ-acetyl)-MCA and Ac-Arg-Gly-Lys(ɛ-acetyl)-MCA also turned out to be good substrates for the enzyme. However, the turnover was diminished compared to that of Boc-Lys(ɛ-acetyl)-MCA. All other tripeptidic substrates proved to be poor substrates for the enzyme. In contrast, rat liver HDAC, which contains mainly HDAC-3 (D. Wegener and A. Schwienhorst, unpublished results), demonstrates a good turnover for all tripeptidic substrates, with a slight preference for Ac-Gly-Ala-Lys(ɛ-acetyl)-MCA (30). The HDAC-like activity of the FB188 amidohydrolase could also be detected by incubation of the enzyme with acetate-radiolabeled histones within the scope of the most widely distributed type of HDAC assay (15). In this case, the FB188 HDAH was able to deacetylate [3H]acetate-prelabeled chicken histones with a Km of 40 μM whereas true HDACs of eukaryotic origin revealed Km values mostly between 30 and 82 μM (16). Interestingly, acetylated tubulin was able to act as a competitive inhibitor in the same assay (P. Loidl, unpublished results). Similarities with HDACs could be extended to inhibition of the latter by certain specific inhibitors. For trichostatin A (TSA), a known HDAC inhibitor (31), the FB188 HDAH showed a 50% inhibitory concentration (IC50) of 1.20 ± 0.12 μM compared to 1.4 nM for rat liver HDAC (30). For the Aquifex aeolicus enzyme, however, an IC50 of 0.4 μM (similar to that of the FB188 HDAH) has been determined previously (6).

FIG. 7.

Sequence specificity of the FB188 HDAH. The deacetylation reactions of Boc-Lys(ɛ-acetyl)-MCA, Z-His-Arg-Lys(ɛ-acetyl)-MCA, Ac-Arg-Gly-Lys(ɛ-acetyl)-MCA, Ac-Gly-Ala-Lys(ɛ-acetyl)-MCA, Tos-Gly-Pro-Lys(ɛ-acetyl)-MCA, and Ac-Gly-Gly-Lys(ɛ-acetyl)-MCA were analyzed using the two-step HDAC assay (30). Standard reaction mixtures contained 125 μM of the respective substrates in HDP buffer (15 mM Tris-HCl [pH 8.1], 250 μM EDTA, 250 mM NaCl, 0.1% PEG 8000) and 4 μg of amidohydrolase. After deacetylation, deacetylated substrate molecules were cleaved by trypsin, which at the same time releases fluorescent 7-amino-4-methylcoumarin. Fluorescence measurement is conducted at a λex of 390 nm and a λem of 460 nm. AFU, arbitrary fluorescence units.

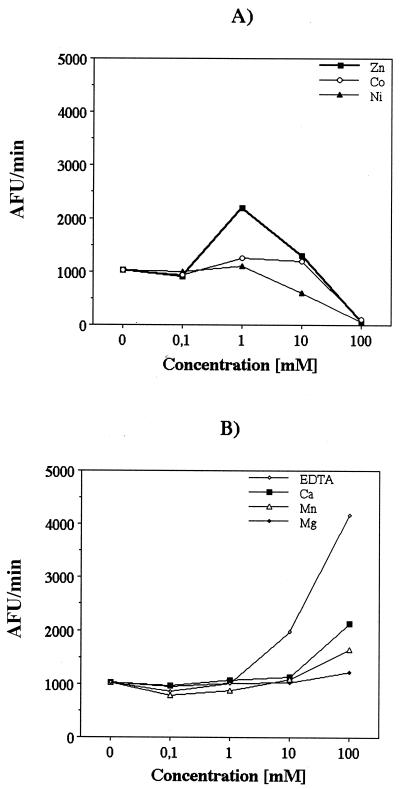

Since class 1 and 2 HDACs contain Zn2+ in the active site, we subjected the FB188 enzyme to a thorough analysis concerning possible metal cofactors. First, the concentration of zinc cations in active recombinant enzyme preparations from standard Ni-IMAC purification was determined by inductively coupled plasma (ICP) spectrometry using a Spectro Modula ICP apparatus (Spectro, Kleve, Germany). Three independent measurements revealed a concentration of 0.19 mol of Zn2+ per mol of enzyme (and an additional 1.17 mol Ni2+). As a control, recombinant HDAC8 (cloned and purified as described previously) (11) revealed a concentration of 5.9 mol of Zn2+ per mol of enzyme. To further examine the possible role of bivalent cations, the relative enzymatic activity levels in the presence of 0 to 100 mM of EDTA, ZnSO4, CoCl2, NiCl2, CaCl2, MgCl2, and MnCl2 were determined using a two-step HDAC assay with Boc-Lys(ɛ-acetyl)-MCA as a substrate (Fig. 8). As a control, the hydrolysis of Boc-Lys-MCA was monitored under the same conditions to exclude a significant inhibition of trypsin in the second step of the assay. Concerning the influence on FB188 HDAH activity, metal cofactors fell into two classes. Only ZnSO4, CoCl2, and NiCl2 were able to increase the catalytic activity (2.2-, 1.3-, and 1.1-fold, respectively) at the relatively low concentration of 1 mM, whereas higher concentrations showed an inhibitory effect. In contrast, MgCl2, MnCl2, and CaCl2 had no significant effect on activity of the FB188 HDAH at concentrations between 0 and 10 mM. At 100 mM concentrations, these compounds exhibited increases in catalytic activity of between 1.2- and 2.1-fold. With EDTA, a similar effect was observed, with an increase in activity of 4.1-fold at 100 mM.

FIG. 8.

Effect of bivalent cations on amidohydrolase activity. The two-step HDAC assay (30) was used to analyze the effect of ZnCl2, CoCl2, and NiCl2 (A) and CaCl2, MgCl2, MnCl2, and EDTA (B) on the activity of the recombinant FB188 HDAH. AFU, arbitrary fluorescence units.

The stimulatory effect of additions of (in particular) Zn2+ ions as well as the results of the ICP measurements could (in principle) indicate that, e.g., as a result of the Ni-IMAC purification only part of the enzyme preparation contains Zn2+ in the active site and thus is catalytically active. We therefore repeated the IMAC purification, replacing Ni2+ ions with Zn2+ ions. The resulting enzyme preparation showed increased specific activity. For Boc-Lys-(ɛ-acetyl)-MCA, the Km and Vmax values were determined to be 14 ± 3 μM and 136 ± 22 pmol s−1 mg−1, respectively. ICP analysis of the Zn-IMAC-purified enzyme revealed a concentration of 19.7 mol of Zn2+ per mol of enzyme.

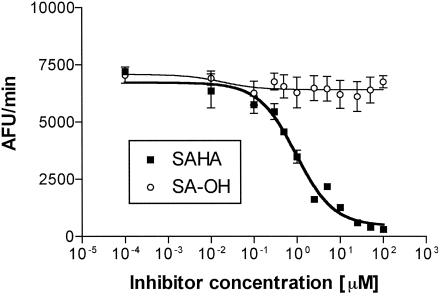

In the complexes of TSA or SAHA with HDAC-like enzyme from A. aeolicus, hydroxamic acid coordinates a zinc in the active site through its carbonyl and hydroxyl groups, contributing significantly to the strong binding of the inhibitor (6). It is known from comparative studies of hydroxamic acids and “parent” carboxylic acids (e.g., butyryl-hydroxamate and butyrate) that carboxylic acid derivatives reveal a >30-fold increase in IC50 values compared to those of the corresponding hydroxamates (26). Thus, using the two-step assay to reveal whether Zn2+ ions are also part of the active site of FB188 HDAH, we studied the inhibition of the enzyme by HDAC inhibitor SAHA and its carboxylic acid analogue SA-OH (Fig. 9). For SAHA, an IC50 of 0.95 ± 0.06 μM was determined with Zn-IMAC-purified enzyme. The carboxylic acid analogue SA-OH was only a very weak inhibitor (less than 10% inhibition at 100 μM) of FB188 HDAH.

FIG. 9.

IC50 measurements (using FB188 HDAH) for SAHA and its carboxylic acid analogue SA-OH. Inhibitory activity was determined in the two-step assay (30) with inhibitor concentrations between 0.0001 and 100 μM. The Zn-IMAC-purified enzyme was used. Similar results were obtained with the Ni-IMAC-purified enzyme (data not shown). AFU, arbitrary fluorescence units.

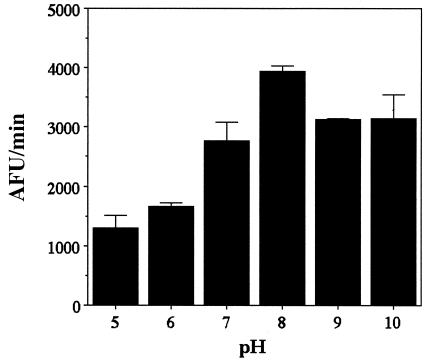

The two-step HDAC assay was also used to analyze the pH dependence of the enzyme (Fig. 10). The pH profile is bell shaped, with a maximum value at pH 8.0, as in the case of the M. ramosa enzyme (23).

FIG. 10.

pH dependency of amidohydrolase activity. The two-step HDAC assay (30) was used to analyze the effect of pH on the activity of the recombinant FB188 HDAH. AFU, arbitrary fluorescence units.

To directly assess the natural target of the FB188 HDAH, total protein from Bordetella/Alcaligenes species FB188 (DSM 11172) and a number of other bacteria was analyzed by Western blotting with acetylated proteins antibody ab193, recognizing ɛ-acetyl-lysine residues (ab193 detects acetylated proteins that possibly become deacetylated upon incubation of total cell protein with recombinant FB188 HDAH). Indeed, a number of presumably acetylated proteins could be detected in total cell protein from FB188, E. coli, Bacillus subtilis, and M. mazei. Preliminary Western blotting results revealed that only one band corresponding to an acetylated protein of approximately 65 kDa in the total protein of FB188 disappeared upon treatment with FB188 HDAH (data not shown). The same band also vanished upon treatment with trypsin or pepsin but was not affected by treatment with FB188 genomic DNA, tRNA, RNase A, DNase I, or ethidium bromide (data not shown). Studies using, e.g., specific high-affinity inhibitors of FB188 HDAH are under way to verify these results and to further characterize the presumable protein target of FB188 HDAH.

The enzyme obtained from FB188 exhibited essentially the same biochemical properties as the recombinant enzyme purified from E. coli, e.g., catalytic activity in the presence of metal cofactors, optimum pH, substrate specificity towards peptidic substrates, and a Km for Boc-Lys(ɛ-acetyl)-MCA of 92 ± 31 μM compared to 127 ± 24 μM for the recombinant Ni-IMAC-purified enzyme.

DISCUSSION

Here, we present the nucleotide sequence of a new amidohydrolase gene from Bordetella/Alcaligenes species FB188 (DSM 11172). Putative regulatory sequences have been identified on the basis of sequence comparison and certainly need verification by a thorough experimental analysis. A comparison of the deduced amino acid sequence and the N-terminal protein sequence revealed that the N-terminal methionine is lacking in the wild-type enzyme. As known from studies of E. coli methionine aminopeptidase, N-terminal methionines are efficiently processed when the penultimate amino acid is small, as it is the case with alanine in the FB188 HDAH (8). Comparison of the deduced amino acid sequence with those in the National Center for Biotechnology Information databases revealed a number of homologs, all belonging to the subgroup of APAH of the HDAC superfamily (Fig. 2). The closest homolog among human HDACs is HDAC6, a presumptive tubulin deacetylase (12).

To facilitate a thorough biochemical characterization, the FB188 HDAH has been cloned and overexpressed in E. coli. Purification has been expedited by introducing an N-terminal His tag into the mature protein. Interestingly, a protein variant with a C-terminal His tag revealed a 5- to 10-fold-lower activity level (data not shown). The purified recombinant enzyme shows biochemical properties essentially the same as those of the natural enzyme from Bordetella/Alcaligenes species FB188 (DSM 11172), as determined for pH optimum, substrate specificity, and cation requirements.

In agreement with findings concerning the enzymes from M. ramosa and A. aeolicus, several lines of evidence indicate that the new enzyme is only catalytically active in the presence of bivalent cations such as Zn2+. First, a comparative sequence analysis has been carried out to look for amino acids that possibly could form a metal-binding site in the FB188 HDAH. On the basis of sequence similarities with carboxypeptidases A, A1, and A2, the metal-binding site in the M. ramosa enzyme has been proposed to consist of four putative zinc binding amino acids (8), two of which are lacking in the FB188 HDAH (Fig. 4). With the first crystal structure of an enzyme from the HDAC superfamily (6), however, the metal-binding site now can be identified far more reliably. Assuming that the FB188 enzyme folds into a structure very similar to that of the homologous enzyme from A. aeolicus, all amino acids responsible for zinc binding appear to be present in the FB188 HDAH. In conclusion, a putative metal-binding site may be present in the FB188 HDAH.

Second, Zn2+ (and, to a smaller extent, Co2+ and Ni2+ also) was able to increase the catalytic activity at relatively low concentrations of 1 mM whereas higher concentrations revealed an inhibitory effect. An inhibitory effect of higher Zn2+ concentrations has also been observed for the APAH from M. ramosa, which was suggested to be an indication for a site-specific inhibitory binding of Zn2+ to the M. ramosa enzyme (8). It is noteworthy at this point that (in comparison to the Ni-IMAC-purified enzyme) the FB188 HDAH purified by Zn-IMAC presumably kept more Zn2+ ions in the active site, since it showed higher specific activity and a significant decrease in the Km value for Boc-Lys(ɛ-acetyl)-MCA. Third, in contrast to the results seen with Co2+, Ni2+, and Zn2+, EDTA (as well as MgCl2, MnCl2, and CaCl2) had a stimulatory effect on catalytic activity at high concentrations (100 mM). We are inclined to interpret these results as an unspecific effect of the presence of a high electrolyte concentration. At this point, it is interesting that in addition to EDTA, imidazole (which had also been used at concentrations of up to 200 mM in the IMAC purification procedure) was obviously unable to inactivate the FB188 HDAH, e.g., through extraction of bivalent metals. The same behavior is known from HDACs and the M. ramosa enzyme (23), which release Zn2+ from the active site only under relatively harsh conditions. In contrast, the enzyme from A. aeolicus was reported to lose its metal cofactor completely during the purification procedure and has to be incubated with zinc chloride to gain catalytic activity (6).

Finally, hydroxamates like TSA and SAHA (known to inhibit HDAC-like enzymes by interacting with zinc in the active site) have been shown to inhibit the FB188 HDAH. Although FB188 HDAH inhibition was observed at IC50 values increased by a factor of 1,000 compared to those measured for eukaryotic HDACs, this fact does not necessarily support the view that zinc is absent from the active site of the enzyme. Alternatively, the increase in IC50 could be explained by a different shape of the active site that results in the loss of optimal inhibitor binding. This is presumably also the case for the A. aeolicus enzyme (6), which contains zinc in the active site and shows IC50 values very similar to those measured for the FB188 HDAH. Further evidence for the presence of zinc in the active site of the FB188 enzyme comes from inhibition studies with SAHA and its carboxylic acid analogue SA-OH; with regard to IC50 values, the latter was a less active inhibitor by a factor of >100 compared to SAHA. In the absence of zinc, very similar inhibition constants would have to be expected. In conclusion, the catalytically active form of the enzyme almost certainly contains a zinc ion in the active site, as is known for class 1 HDACs. Ongoing crystallographic studies should reveal whether similarities with other HDAC-like enzymes can be extended to the geometry of the active site and the binding mode of HDAC inhibitors.

The independence of cofactors, the broad optimum pH range, and the large substrate spectrum lead us to suggest using the new HDAH from Bordetella/Alcaligenes strain FB188 as a biocatalyst in technical biotransformations. Indeed, feasibility of the new HDAH as an enantioselective, technical biocatalyst was demonstrated using NAA, a precursor of certain new anti-human immunodeficiency virus drugs (13), as a substrate.

To narrow down the possible characteristics of the biological role of this novel enzyme, a number of different substrates were analyzed. Surprisingly, acetylpolyamines were rather poor substrates, indicating that the enzyme might not play a significant role in the degradative pathway of acetylpolyamines in FB188 but might rather be involved in the regulation of other cellular processes. Since the sequence of the FB188 HDAH showed significant homologies to those of HDACs, we tested the enzyme for a possible HDAC-like activity in a variety of assays. Indeed, the enzyme exhibited significant levels of protein deacetylase activity comparable to those of eukaryotic HDACs in assays with both fluorogenic peptidic substrates and acetate-radiolabeled histones. The acetate-radiolabeled histone assays revealed that the FB188 HDAH is able to accept proteins with ɛ-acetylated lysine residues as substrates. Further, [3H]acetate-prelabeled chicken histones are deacetylated with Km values comparable to those of eukaryotic HDACs. Interestingly, tubulin was able to act as a competitive inhibitor in these assays (P. Loidl, unpublished), adding further evidence for a similarity between the FB188 HDAH and HDAC6 (32). With tripeptidic substrates, only Z-His-Arg-Lys(ɛ-acetyl)-MCA and Ac-Arg-Gly-Lys(ɛ-acetyl)-MCA proved to be superior substrates, suggesting that the FB188 HDAH (in contrast to rat liver HDAC) might have a certain sequence specificity with a preference for positive charges in the vicinity of the cleavage site. Similarities with eukaryotic HDACs, however, could be further extended by showing that classical HDAC inhibitors such as TSA and SAHA were able to specifically inhibit the FB188 HDAH.

To shed some light on a possible biological role of the FB188 HDAH, we thought of further testing the enzyme for its inherent protein deacetylase activity by identifying a possible natural target of the FB188 HDAH. Therefore, total protein of Bordetella/Alcaligenes species FB188 (DSM 11172), E. coli XL1-Blue, and M. mazei was analyzed by Western blotting with an antibody (ab193) recognizing ɛ-acetyl-lysine residues, e.g., in a number of different proteins (acetylated proteins antibody [ab193] datasheet, Abcam, 1998). In each case, we assumed that acetylated proteins were detected. Preliminary experiments concerning the treatment of total protein with FB188 HDAH revealed that (specifically) one protein band at approximately 65 kDa in the total protein of FB188 disappeared upon treatment with FB188 HDAH. The same band also vanished after incubation of total cell protein with trypsin or pepsin but not by treatment with tRNA, genomic double-stranded DNA, RNase A, DNase I, or ethidium bromide, thus suggesting that the target is a protein that is not strongly bound to nucleic acid.

In conclusion, we would like to suggest that there is a possibility that the FB188 HDAH from Bordetella/Alcaligenes species FB188 (DSM 11172) is the first example of a well-characterized bacterial protein deacetylase that (in vivo) specifically deacetylates a protein that presumably is not related to the functional context of DNA binding, as is the case for Alba, an acetylatable 10-kDa protein from the archaeon S. solfataricus P2 (3). More far-reaching studies have now been started to further characterize the presumable substrate protein of the FB188 HDAH to illuminate what now seems to be a novel biological role of HDAC-like enzymes.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported in part by BioFuture grant 0311852 and grant 0311816 from the Bundesministerium für Forschung und Technologie.

We are grateful to A. Kriegel from the Institut fuer Bodenkunde und Waldernaehrung, Georg-August University of Goettingen, for assistance concerning ICP spectrometry. We also thank H. Brass and R. Willmott for many fruitful discussions and for reading the manuscript. Technical support from Cybio AG and BMG GmbH is gratefully acknowledged.

REFERENCES

- 1.Altschul, S. F., and D. J. Lipman. 1990. Protein database searches for multiple alignments. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 87:5509-5513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Baumann, M., R. Stürmer, and U. T. Bornscheuer. 2001. A high-throughput-screening method for the identification of enantioselective hydrolases. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 40:4201-4204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bell, S. D., C. H. Botting, B. N. Wardleworth, S. P. Jackson, and M. F. White. 2002. The interaction of Alba, a conserved archaeal chromatin protein, with Sir2 and its regulation by acetylation. Science 296:148-151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bradford, M. M. 1976. A rapid and sensitive method for the quantitative of microgram quantities of protein utilizing the principle of protein dye binding. Anal. Biochem. 72:248-254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Collins, F. S., and S. M. Weissman. 1984. Directional cloning of DNA fragments at a large distance from an initial probe: a circularization method. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 81:6812-6816. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Finnin, M. S., J. R. Donigian, A. Cohen, V. M. Richon, R. A. Rifkind, P. A. Marks, R. Breslow, and N. P. Pavletich. 1999. Structures of a histone deacetylase homologue bound to TSA and SAHA inhibitors. Nature 401:188-193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Grozinger, C. M., and S. L. Schreiber. 2002. Deacetylase enzymes: biological functions and the use of small-molecule inhibitors. Chem. Biol. 9:3-16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hirel, P.-H., J.-M. Schmitter, P. Dessen, G. Fayat, and S. Blanquet. 1989. Extent of N-terminal methionine excision from Escherichia coli proteins is governed by the side-chain length of the penultimate amino acid. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 86:8247-8251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hofacker, I. L., W. Fontana, and P. F. Stadler. 1994. Fast folding and comparison of (RNA) secondary structures. Monatsh. Chem. 125:167-188. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hoffmann, K., G. Brosch, P. Loidl, and M. Jung. 2000. First non-radioactive assay for in vitro screening of histone deacetylase. Pharmazie 55:601-606. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hu, E., Z. Chen, T. Fredrickson, Q. Zhu, R. Kirkpatrick, G.-F. Zhang, K. Johanson, C.-M. Sung, R. Liu, and J. Winkler. 2000. Cloning and characterization of a novel human class I histone deacetylase that functions as a transcriptional repressor. J. Biol. Chem. 275:15254-15264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hubbert, C., A. Guardiola, R. Shao, Y. Kawaguchi, A. Ito, A. Nixon, M. Yoshida, X.-F. Wang, and T.-P. Yao. 2002. HDAC6 is a microtubule-associated deacetylase. Nature 417:455-458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Huff, J. R. 1999. Abacavir sulfate. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 7:2667-2669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Khochbin, S., and A. P. Wolffe. 1997. The origin and utility of histone deacetylase. FEBS Lett. 419:157-160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kölle, D., G. Brosch, T. Lechner, A. Lusser, and P. Loidl. 1998. Biochemical methods for analysis of histone deacetylases. Methods 15:323-331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lechner, T., A. Lusser, G. Brosch, A. Eberharter, M. Goralik-Schramel, and P. Loidl. 1996. A comparative study of histone deacetylases of plant, fungal and vertebrate cells. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1296:181-188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Leipe, D. D., and D. Landsman. 1997. Histone deacetylases, acetoin utilization proteins and acetylpolyamine amidohydrolases are members of an ancient protein superfamily. Nucleic Acids Res. 25:3693-3697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Link, A. J. 1999. 2-D Proteome analysis protocols. Humana Press, Totowa, N.J.

- 19.Marmorstein, R. 2001. Structure of histone deacetylases: insights into substrate recognition and catalysis. Structure 9:1127-1133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Marton, L. J., and A. E. Pegg. 1995. Polyamines as targets for therapeutic intervention. Annu. Rev. Pharmacol. Toxicol. 35:55-91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ninkovic, M., R. Dietrich, G. Aral, and A. Schwienhorst. 2001. High fidelity in vitro recombination using a proofreading polymerase. BioTechniques 30:530-536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ramakrishnan, R., M. Schuster, and R. B. Bourret. 1998. Acetylation at Lys-92 enhances signaling by the chemotaxis response regulator protein CheY. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 95:4918-4923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sakurada, K., T. Ohta, K. Fujishiro, M. Hasegawa, and K. Aisaka. 1996. Acetylpolyamine amidohydrolase from Mycoplana ramosa: gene cloning and characterization of the metal-substituted enzyme. J. Bacteriol. 178:5781-5786. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sambrook, J., E. F. Fritsch, and T. Maniatis. 1989. Molecular cloning, 2nd ed. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y.

- 25.Schlegel, H. G. 1985. Allgemeine Mikrobiologie. Thieme Verlag, Stuttgart, Germany.

- 26.Skarpidi, E., H. Cao, B. Heltweg, B. F. White, R. L. Marhenke, M. Jung, and G. Stamatoyannopoulos. 2003. Hydroxamide derivatives of short-chain fatty acids are potent inducers of human fetal globin gene expression. Exp. Hematol. 31:197-203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Stowell, J. C., R. I. Huot, and L. Van Voast. 1995. The synthesis of N-hydroxy-N′-phenyloctanediamide and its inhibitory effect on proliferation of AXC rat prostate cells. J. Med. Chem. 38:1411-1413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Udenfriend, S., S. Stein, P. Böhlen, W. Dairman, W. Leimgruber, and M. Weigele. 1972. Fluorescamine: a reagent for assay of amino acids, peptides, proteins, and primary amines in the picomole range. Science 178:871-872. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wegener, D., C. Hildmann, D. Riester, and A. Schwienhorst. 2003. Improved fluorogenic histone deacetylase assay for high-throughput-screening applications. Anal. Biochem. 321:202-208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wegener, D., F. Wirsching, D. Riester, and A. Schwienhorst. 2003. A fluorogenic histone deacetylase assay well suited for high-throughput activity screening. Chem. Biol. 10:61-68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yoshida, M., M. Kijima, M. Akita, and T. Beppu. 1990. Potent and specific inhibition of mammalian histone deacetylase both in vivo and in vitro by trichostatin A. J. Biol. Chem. 265:17174-17179. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zhang, Y., N. Li, C. Caron, G. Matthias, D. Hess, S. Khochbin, and P. Matthias. 2003. HDAC-6 interacts with and deacetylates tubulin and microtubules in vivo. EMBO J. 22:1168-1179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]