Introduction

The success of Mycobacterium tuberculosis is due in large part to its unique metabolism, which provides the capability to survive in the host environment, resist treatment and resume growth to relapse disease. It is widely accepted that tuberculosis is a dynamic disease that results from a combination of phenotypically diverse populations of bacilli in a continually changing host environment. This phenotypic capacity is encoded within the bacterial genome and is derived from an orchestrated expression of genes and ORFs tailored to specific alternative growth conditions encountered in the host.

The sequencing of complete genomes has accelerated biomedical research by providing an understanding of the metabolic diversity encoded by an organism. TB research was ushered into the post-genomic era in 1998 with completion of the whole genome sequence and annotation 1. Genomic information is now an integral part of the research workflow, and impacts all aspects of TB research including drug discovery, diagnostics, vaccine development and epidemiology. The greatest benefit of genome sequence is that it provides the foundational information about the extent of coding capacity. In combination with next generation sequencing technologies, investigators are now able to sequence genomes, including clinical isolates of interest in a few weeks making accurate and comprehensive genome annotation more important than ever.

The original annotation of the M. tuberculosis H37Rv genome resulted in the identification of 3,924 ORFs, with ∼60% assigned to specific metabolic functions, and the remaining ORFs categorized as conserved hypothetical proteins (∼25%) or hypothetical proteins or encoding proteins of unknown function (∼16%) 1. In 2002, the M. tuberculosis genome was reannotated. Eighty-two new protein-coding sequences (CDS) were included and 22 of these had an annotated function. In addition, supporting information including more than 300 gene names and over 1,000 publications were added to support the annotation. With this version of the annotation, it was possible to assign a function to 2,058 proteins (∼52% of the 3,995 proteins predicted) and only 376 putative proteins shared no homology with known proteins 2.

The TB research community is now at the beginning of the next phases of post-genomics; namely reannotation and functional characterization by targeted experimentation. Arguably, this is the most significant time for basic microbiology in recent history. The objective of the Tuberculosis Community Annotation Project (TBCAP) jamboree, and the development of a TBCAP community is not to overwrite the original annotation and re-assign all the ORFs encoded in the M. tuberculosis genome, but rather provide additional information for previous annotations, and refine and substantiate the functional assignment of ORFs and genes within metabolic pathways, and to assign ORFs to gaps in metabolic pathways. Over the course of the last year, two NIAID-funded Centers, the Genomic Sequencing Center for Infectious Diseases at the Broad Institute and the Bacterial Bioinformatics Resource Center PATRIC, joined forces with the Gates-funded Tuberculosis Database (TBDB), and members of the TB research community to plan and support a collaborative TBCAP to achieve a full reannotation of the M. tuberculosis genome based on currently available information. The overall goal of TBCAP is to gather and compile various data types and use this information with oversight from the scientific community to provide additional information to support the functional annotations of encoding genes. Another objective of this effort is to standardize the publicly accessible M. tuberculosis reference sequence and its annotation. This report describes the results of TBCAP 2012 Jamboree of the group of curators collectively known as the metabolism working group, and key metabolic areas of contemporary importance.

Methods

Information used by TBCAP for assignment of gene function

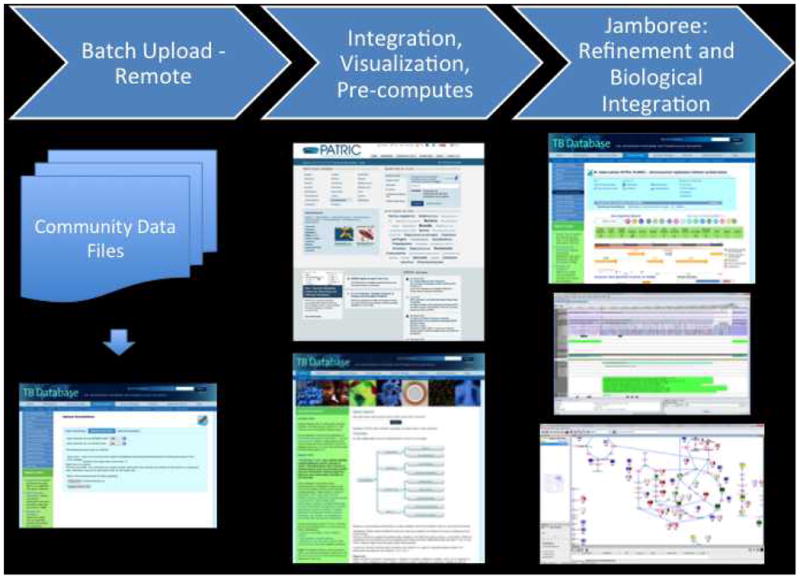

Select mycobacterial investigators participated in the TBCAP jamboree 2012. TBCAP participants performed manual annotations in their respective areas of expertise. Information substantiating each annotation consisted of up to five parts: (1) an ontology term that described the function of the gene, (2) an evidence code that described the kind of experiment performed to determine the function, (3) a citation to a publication that described the experiment in detail, (4) a free text comment, and (5) the name of the curator who submitted the annotation. Curators uploaded annotations and information to the Basecamp content management system. The discussion boards of Basecamp are used to communicate additional information and comments. All the annotation information received was parsed and formatted using python. The resulting formatted annotation information was uploaded to the Tuberculosis Database (TBDB website at http://tbdb.org) and automatically integrated with previous annotations. These annotations then served as the foundation and the functional annotations were projected onto a metabolic chart generated by Pathway-tools. The information can be searched, viewed, and exported from the TBDB interface. The annotations can be searched, viewed and exported from TBDB and PATRIC (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Tuberculosis Database interface (TBDB website at http://tbdb.org).

The TBCAP is a “collaborative investigator community” of experts to share current functional annotation in there respective areas of interest

Since the TBCAP 2012 meeting, the TBCAP has transitioned to a supervised dispersed community annotation project 3. The leaders of each of the working groups serve as points of contact to coordinate future functional annotation efforts.

Results and Discussion

The impact of the TB genome sequence and annotation ultimately depends on functional characterization. Indeed, being able to substantiate the functional annotation of genes is the next hurdle that the TB scientific community faces. To address this critical need, the TB Community Annotation Project (TBCAP) was created to bring together TB investigators to contribute expertise to define the function of encoded gene products. TBCAP promises to power the functional assignment of genes and importantly, make the information rapidly accessible to all investigators. Whether this transition from information being generated by bioinformatics analysis alone to involving the greater research community is being driven from the diminishing return of functional knowledge from homology-based comparative genomics is not the focus. Rather, the importance of experimental information and its rapid dissemination, and how this information is maintained is the goal. Ultimately, the conception behind the TBCAP is continuing community investment.

Developments in analytical techniques and in genetic methodologies allowing for the expression and disruption of genes in M. tuberculosis combined with the definition of the genome of this bacterium in 1998 have stimulated a rapid evolution of knowledge resulting in a relatively thorough understanding, not only of the basic metabolic tendencies and capabilities, and the structure of the mycobacterial cell envelope, but also its biosynthesis and underlying genetics. The availability of the genome sequence of M. tuberculosis, however, also inevitably has resulted in the annotation of a multitude of ORFs for which biochemical or genetic evidence substantiating function is still lacking.

While the exact experimental evidence required for a functional annotation is debatable, it is generally agreed that a combination of experimental information about essentiality, phenotype, enzymatic or structural role, protein-protein interaction, protein localization and conditions of expression and production is needed. Towards the functional annotation of the encoded gene products of M. tuberculosis, TBCAP assembled all the available information including ontology, EC number, PubMed citations for each gene (Figure 2). This provided a framework for assignment of a gene to a categorization based on extent of information and grouped genes into one of 3-categories (Categories I-III) indicating functional annotation or metabolic function (Category IV).

Figure 2.

Representative pathway information.

More than 30,000 annotations were contributed from 83 annotators using 13 kinds of experimental evidence from 1,104 publications. Together, 5,246 unique ontology terms, 1,171 different gene symbols, 1,230 specific gene names and 2,714 free text comments have been identified for 2,183 genes in M. tuberculosis (Table 1), derived by numerous sources. Functional gaps in pathways of contemporary importance such as cell envelope macromolecular synthesis, cholesterol synthesis, septum formation and cell division regulation and toxin-antitoxin loci were then targeted for subsequent focused functional curation.

Table 1.

Statistics of the TBCAP 2012 Annotation Jamboree.

| Unique annotations | 30,092 |

| Unique loci | 2,183 |

| Unique gene symbols | 1,171 |

| Unique gene functions | 1,230 |

| Unique ontology terms | 5,246 |

| Unique evidence codes | 13 |

| Unique Pubmed citations | 1,104 |

| Unique free text comments | 2,714 |

| Unique annotators | 83 |

Category I. Metabolic functions assigned to genes

Assignment of a gene to this category is based on information of standard ontology including EC number, MetaCyc or KEGG. Evidence for assignment includes at least one PubMed citation, along with an evidence code from a standard ontology that specifies the type of experiment performed, a free text associated with the annotation, and contact information for the annotator.

Category II. Non-enzymatic metabolic functions assigned to genes

Assignment of each non-metabolic gene function is from a standard ontology, such as GO, supported by at least one PubMed publication, along with an evidence code from a standard evidence ontology. The Metabolism working group did not curate these genes because their functional assignment was strongly supported by previous annotation efforts.

Category III. Genes with no metabolic function assigned

Genes are assigned to this category because there is limited functional information. A gene can leave category III when it has been assigned a function from a standard ontology, and the evidence for the assignment comes from an experiment that has been published.

Category IV. Metabolic functions not represented by annotated genes

For each metabolic function where there are no assigned genes, each reaction is indicated by chemical structures, so that there is no ambiguity as to the missing reaction or function. Substantiation of a reaction being encoded in M. tuberculosis, for which no genes that catalyze the reaction are known, should come from at least one publication and have an evidence code that specifies the type of experiment performed.

The goal of this report is to present the TBCAP approach of functional annotation of genes involved in metabolic pathways to the greater TB research community and to introduce the guidelines for functional assignment of genes, which will become critically important as the research community is confronted with increasing amounts of data in this post-genomic era. The following describes the areas of contribution from the TBCAP 2012 jamboree.

Areas of contribution to Category I. Metabolic functions assigned to genes

The structural integrity of the mycobacterial cellular envelope contributes to its pathogenicity, and its complexity plays a significant role in in vivo survival. Moreover, the assembly of its unique components is responsible for mycobacterial characteristics such as its low permeability and inherent resistance to common therapeutics. Although the infrastructure of the mycobacterial cell wall “core”, which consists of peptidoglycan, arabinogalactan, and mycolic acids, and unique lipids is well characterized, all the genes encoding the processes for the intricate assembly remained to be defined. Another defining feature of M. tuberculosis is its ability to subsist in a non-replicating persistent state in the host for long periods under alternative nutrient conditions. The ability for this is encoded in pathways such as cholesterol metabolism, regulation of septum formation, cell division and cell cycle progression and adaptation to stress. Using the genome of M. tuberculosis H37Rv as the reference, experts in these processes of mycobacteria applied the following criteria to assign function: (1) A clear differentiation of what has been experimentally proven and documented from what is merely predicted; (2) The type of experimental evidence associated to an annotated gene (e.g., enzymatic or phenotypic). (3) Accurate PubMed references where the experimental evidence can be found; (4) General information about the end-product or pathway in which the gene of interest is involved.

Cell envelope biosynthetic enzymes

The cell envelope of M. tuberculosis contains unique lipids and (lipo)polysaccharides important from the perspective of host-pathogen interactions and as potential targets for new drug development against TB. The involvement of putative genes in lipid or glycoconjugate metabolism is most of the time inferred from the presence of signature motifs within their sequence or their homology to [more or less] characterized genes from other species; these genes are usually not assigned to any particular biosynthetic pathway. This wealth of sometimes insufficiently curated information combined with the complexity of the pathways leading to the biogenesis of all of the unique chemical structures found in the cell envelope of M. tuberculosis can make it difficult for the end-point user to accurately interpret genomic data.

The result of the TBCAP reannotation of cell envelope-related biosynthetic pathways is presented in Table 2. As evidenced by this Table, despite the considerable progress made in deciphering the biosynthesis of key cell envelope precursors and end-products since the genome sequence of M. tuberculosis was first released, many pathways are still incomplete. For instance, as of February 2012, only 13 enzymes involved in the synthesis of PIM, LM and LAM have been identified and at least partially characterized; eleven enzymes only have been involved in the biosynthesis of polymethyl-branched acyltrehaloses. Gaps in our understanding of the biosynthesis of the M. tuberculosis major cell envelope glycolipids and (lipo)polysaccharides were highlighted in a recent publication4 and will thus not be detailed here. The exact number of genes missing in each of these pathways is difficult to estimate as some of the enzymes involved in the biosynthetic pathways of arabinogalactan (AG) or lipoarabinomannan (LAM), for example, were found to be endowed with more than one catalytic function (e.g., Rv2181) 4, to elongate iteratively biosynthetic precursors (e.g., GlfT1, GlfT2) 4, or to participate in the biosynthesis of both AG and LAM (e.g., the arabinosyltransferases AftC and AftD) 4-7. Conversely, evidence for what appears to be gene redundancy was found in some pathways such as that of mycolic acids (e.g., mycoloyltransferases) and α-1,4-D-glucans (e.g., α-1,4-glucosyltransferases) 4.

Table 2.

Biogenesis of the major cell envelope components of M. tuberculosis H37Rv.

| Biosynthetic pathway | # Genes | Evidence | # Refs | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Phenotypic | Enzymatic | Homology | |||

| Non-mevalonate isopentenyl diphosphate synthesis | 5 | 0 | 5 | 0 | 12 |

| Prenyl diphosphate synthases | 4 | 0 | 4 | 0 | 7 |

| Peptidoglycan synthesis and turnover / cell division | 69 | 28 | 24 | 34 | 89 |

| Arabinogalactan synthesis | 28 | 10 | 22 | 0 | 33 |

| Fatty acids, mycolic acids, TMM and TDM (synthesis, transport, regulation, and processing) | 66 | 31 | 30 | 27 | 67 |

| Phospholipid biosynthesis | 6 | 1 | 2 | 4 | 2 |

| Triglyceride biosynthesis | 16 | 2 | 16 | 0 | 3 |

| PIM, LM and LAM biosynthesis | 13 | 13 | 10 | 0 | 24 |

| Methylglucose lipopolysaccharides*, glycogen* and capsular α-glucans | 13 | 9 | 7 | 3 | 13 |

| Polymethylbranched fatty acid-containing acyltrehaloses | 12 | 11 | 5 | 1 | 10 |

| Phthiocerol dimycocerosates, phenolic glycolipids and p-hydroxybenzoic acid derivatives | 27 | 27 | 9 | 0 | 31 |

| Mannosyl-β-1-phosphomycoketides | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 2 |

The number of genes that were annotated per major biosynthetic pathways during the TB CAP exercise, and the evidence and number of PMID references on which the annotation was based are shown. The experimental evidence for the annotation of a gene may either be ‘enzymatic’ (i.e., an enzymatic activity was associated to the gene's product in vitro) or ‘phenotypic’ (i.e., the annotation results from the biochemical analysis of mycobacterial recombinant strains – e.g., knock-out / knock-down mutants, complemented mutant strains, overexpressors - or from the functional complementation of defined E. coli mutants). In some cases, the function of a gene is exclusively based on its homology to other known (myco)bacterial genes. TMM, trehalose monomycolates; TDM, trehalose dimycolates.

Glycogen and methylglucose lipopolysaccharides were included in the analysis because they share common biosynthetic genes with capsular α-glucan. They are, however, cytosolic (lipo)polysaccharides.

The analysis of common prokaryotic pathways such as that of peptidoglycan (PG) also highlighted some intriguing mycobacterial particularities. The PG-related genes described in Table 2 have been organized according to the following pathways or groups: precursor synthesis, assembly/maturation, turnover, cell division, and β-lactam resistance enzymes. While M. tuberculosis shares, overall the same basic precursor genes with other bacteria (an exception is namH), no genes have been identified for the amidation of D-glutamate or meso-DAP in the mycobacterial PG peptides. PG assembly, maturation and turnover enzymes were first identified by homology and more work needs to be done to understand their role in PG physiology. Likewise, cell division gene assignments were essentially based upon homology, but with additional confirmatory work for key genes. Interestingly, mycobacteria lack the lateral wall PG machinery seen in other rod-shaped bacteria and thus there may be additional genes, specific to mycobacteria, which are required for cell growth and division that remain to be discovered. Most enigmatic is the β-lactamase/esterase/peptidase group. Although the primary β-lactamase is known (rv2068c), the genome annotation suggests that other β-lactamase-like enzymes may contribute to β-lactam antibiotic resistance in M. tuberculosis although their function in cell wall metabolism is yet to be revealed.

Identification of outer membrane proteins (OMPs) in M. tuberculosis

The presence and complexity of the outer membrane (OM) in mycobacteria requires unique outer membrane proteins 8, 9. A few examples for such transport mechanisms are the secretion of proteins such as ESAT-6 via the Esx system 10, the secretion of carboxymycobactin for iron acquisition 11 or the transport of cell surface components such as lipids of the outer leaflet of the OM or some of the enigmatic PE-PGRS proteins 12. Many of these processes are required either for virulence or growth of M. tuberculosis in vitro. The same holds true for uptake of nutrients and efflux of waste products 13. OMPs, in particular porins and efflux channels, have been shown to play important roles in antibiotic resistance 14-16. This short list already shows that our knowledge about the physiology, the pathogenicity and drug resistance mechanisms of M. tuberculosis will be incomplete without the characterization of OM proteins. Unfortunately, our progress in identifying these elusive proteins has not kept pace with the increasing recognition about their importance, because sequence based analysis is not sufficient, thus requiring a combination of bioinformatics and experimentation.

Structural bioinformatics was used to identify OMPs of M. tuberculosis 17. This approach was based on the properties of the porin MspA of M. smegmatis, which forms a β-barrel structure 18, has no hydrophobic α-helices and a signal peptide which directs export of MspA across the inner membrane via the Sec system 19. These observations were exploited in a multi-step bioinformatics approach to predict OMPs of M. tuberculosis. A secondary structure analysis was performed for 587 proteins of M. tuberculosis with a classical signal peptide. Proteins were predicted to be located in the OM if they had a high β-strand content and a high amphiphilicity of the β-strands. OMPs of gram-negative bacteria were used as reference proteins to define threshold values for these parameters. While this approach gives an indication about the propensity of a particular protein to be in the OM, it has recognized limitations: (i) The proteins were pre-selected to contain a classical signal peptide, although it is not clear whether export of OMPs could also be mediated by mechanisms other than the Sec system. (ii) Proteins with a hydrophobic helix were excluded although it is known that some OMPs of Gram-negative bacteria have hydrophobic helices. (iii) The search for putative OMPs was limited to proteins with a high β-strand content because almost all known OMPs are β-barrel proteins including MspA 20. However, OMPs which have a low β-barrel content or do not form β-barrels are known 21, 22 (iv). The threshold values for β-strand content and amphiphilicity were set arbitrarily using Gram-negative reference proteins. The lower limit for these values in mycobacterial OMPs are unknown. (iv) Lipoproteins were ignored, although some integral lipoproteins in the OM of Gram-negative bacteria are known 23. (v) This bioinformatics analysis was recently refined by fine-tuning the cut-off values and calculating a single score for OMP prediction for all proteins encoded by the genome of seven mycobacteria 24. Taken together, the prediction results are useful guides for experimental verification.

One of the intriguing properties of mycobacterial OMPs is that they need to fulfill the same basic functions in uptake and efflux processes as their counterparts in Gram-negative bacteria 25. However, proteins with different folds, probably because of the different membrane environments, apparently mediate these functions. Unfortunately, this also means that these proteins cannot be recognized by sequence or structural similarities. Rv0899 (previously named OmpATb) is an example of how sequence similarity with the periplasmic C-terminal domain of OmpA proteins of Gram-negative bacteria led to the wrong conclusion that Rv0899 is also an integral OMP in M. tuberculosis 26, 27. The NMR structure revealed that Rv0899 does not form a transmembrane domain 28 and has no detectable porin activity in mycobacteria, but binds to PG 29 and is involved in acid adaptation of M. tuberculosis 30. Another porin candidate, Rv1698, was identified as an OMP of M. tuberculosis with channel activity 17, 31. Heterologous expression of rv1698 in an M. smegmatis porin mutant partially complemented the permeability defects of the strain. However, recent experiments with M. tuberculosis and M. smegmatis mutants show that facilitation of nutrient uptake is not the physiological function of the Rv1698 pore, but rather an overexpression artifact (Wolschendorf and Niederweis, unpublished). Although it was confirmed that Rv1698 is membrane-associated, current data do not allow us to distinguish between the inner and the outer membrane.

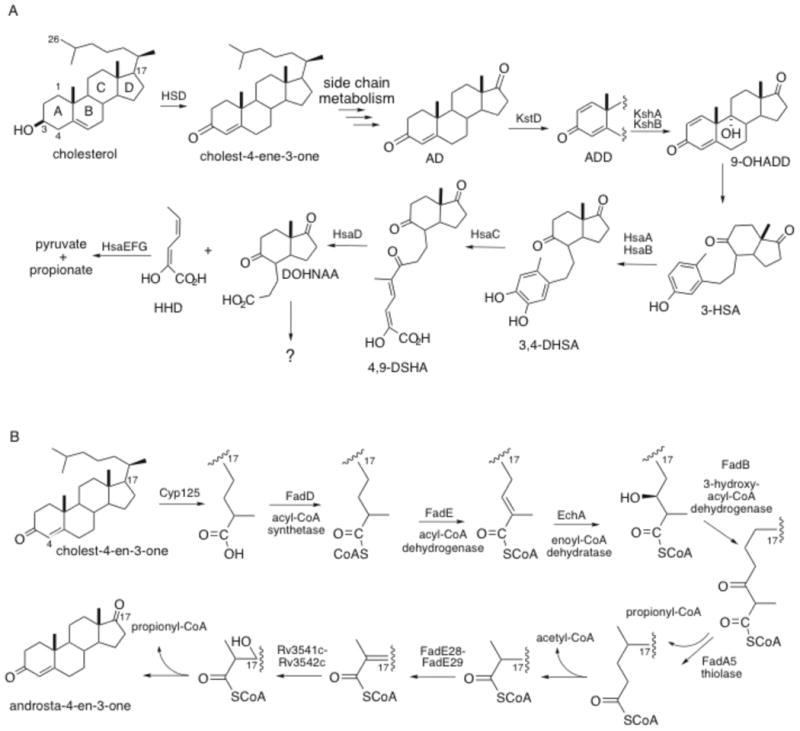

Update of the cholesterol metabolic pathway

Carbon metabolism by bacteria in vivo is a fundamental process that is key to survival and virulence 32. In general in vivo metabolism is poorly understood and M. tuberculosis metabolism is no exception 33. Many genes annotated as being involved in M. tuberculosis lipid and fatty acid metabolism have not been experimentally studied and their function remains to defined. A growing body of evidence indicates that M. tuberculosis utilizes cholesterol during persistent infection in vivo and this ability may be important for disease progression and development of non-replicating persistance. M. tuberculosis genes involved in cholesterol metabolism have been identified from the set of over 250 computationally annotated lipid metabolizing genes by a combination of transcriptional profiling 34 and global phenotypic profiling experiments 35. Despite recent reports, genes encoding required steps in the cholesterol metabolic pathway have not been fully defined. Elucidating the pathway is necessary to understand the role of this pathway in mycobacterial survival and infection as well as to define novel targets for drug development.

Cholesterol ring metabolism occurs via aromatization of the A ring followed by meta-cleavage of the B ring. The enzymes involved have been characterized to varying extents (Table 3). The first step is the oxidation and isomerization of cholesterol to cholest-4-ene-3-one by 3β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase, 3β-HSD 36, 37. The A ring then undergoes 1,2-desaturation catalyzed by a 3-ketosteroid Δ1–dehydrogenase, KstD 38. Next the two-component Rieske oxygenase, 3-ketosteroid-9α-hydroxylase KshAB catalyzes the hydroxylation at C9, which leads to aromatization of the A ring and opening of ring B forming 3-hydroxy-9,10-seconandrost-1,3,5(10)triene-9,17-dione (3-HSA) 39. 3-HSA-hydroxylase HsaAB hydroxylates 3-HSA to the catechol 3,4-dihydroxy-9,10-seconandrost-1,3,5(10)-triene-9,17-dione (3,4-DSHA) 40. Meta-cleavage of the A ring proceeds by extradiol dioxygenes HsaC 41, 42. Next, hydrolase HsaD catalyzes the cleavage of 4,5-9,10-diseco-3-hydroxy-5,9,17-trioxoandrosta-1(10), 2-diene-4-ioc acid(4,9-DSHA) forming 2-hydroxy-hexa-2,4-dienoic acid (HDD) and 9,17-dioxo-1,2,3,4,10,19-hexanoandrostan-5-ioc acid (DOHNAA) 42, 43.

Table 3.

Genes involved in the metabolism of cholesterol by M. tuberculosis and the experiments conducted for each gene.

| Gene name | Mtb gene number | Putative function | Studies performed | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| hsd | Rv1106c | 3β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase | B, C, D, E, G, H | 36, 37 |

| kstD | Rv3537 | ketosteroid Δ1-dehydrogenase | B, C, D, E, H | 38, 93 |

| kshA | Rv3526 | 3-Ketosteroid 9α-hydroxylase | B, D, E, F, H | 39, 94, 95 |

| kshB | Rv3571 | 3-Ketosteroid 9α-hydroxylase | B, D, E, F, H | 39, 94, 95 |

| hsaA | Rv3570c | 3-HSA-hydroxylase | B, D, E, H | 40 |

| hsaB | Rv3567c | 3-HSA-hydroxylase | B, D, E | 40 |

| hsaC | Rv3568c | 2,3-dehydroxyphenyl dioxygenase | B, E, F, H | 41 |

| hsaD | Rv3569c | 4,9-DSHA hydrolase | B, E, H | 96 |

| hsaE | Rv3536c | hydratase | A, E | 42 |

| hsaF | Rv3534c | aldolase | A, E | 42 |

| hsaG | Rv3535c | acetaldehyde dehydrogenase | A, E | 5 |

| cyp125 | Rv3545c | cytochrome P450 | B, D, F | 50, 51, 54, 97-99 |

| cyp142 | Rv3518c | cytochrome P450 | B | 52, 100 |

| fadD3 | Rv3561 | acyl-CoA synthetase | D, E | |

| fadD17 | Rv3506 | acyl-CoA synthetase | A,E | |

| fadD18 | Rv3513c | acyl-CoA synthetase | A,E | |

| fadD19 | Rv3515c | acyl-CoA synthetase | D, E | |

| fadD36 | Rv1193 | acyl-CoA synthetase | D | |

| fadE5 | Rv0244c | acyl-CoA dehydrogenase | D, E | |

| fadE14 | Rv1346 | acyl-CoA dehydrogenase | E | |

| fadE17 | Rv1934c | acyl-CoA dehydrogenase | E | 54, 55, 99 |

| fadE18 | Rv1933c | acyl-CoA dehydrogenase | E | 54, 55, 99 |

| fadE25 | Rv3274c | acyl-CoA dehydrogenase | D | |

| fadE26 | Rv3504 | acyl-CoA dehydrogenase | E | |

| fadE27 | Rv3505 | acyl-CoA dehydrogenase | E | |

| fadE28 | Rv3544c | acyl-CoA dehydrogenase | B, C, D, E, F | 54, 55, 99 |

| fadE29 | Rv3543c | acyl-CoA dehydrogenase | B, C, D, E, F | 54, 55, 99 |

| fadE30 | Rv3560c | acyl-CoA dehydrogenase | D, E | |

| fadE31 | Rv3562 | acyl-CoA dehydrogenase | D, E | |

| fadE32 | Rv3563 | acyl-CoA dehydrogenase | D, E | |

| fadE33 | Rv3564 | acyl-CoA dehydrogenase | D, E | |

| fadE34 | Rv3573c | acyl-CoA dehydrogenase | D, E | |

| echA9 | Rv1071c | (S)-enoyl-CoA hydratase | D | |

| echA19 | Rv3516 | (S)-enoyl-CoA hydratase | E, G | |

| echA20 | Rv3550 | (S)-enoyl-CoA hydratase | E | |

| Rv3541c | (R)-enoyl-CoA hydratase | C, D, E, F | 54, 55, 99 | |

| Rv3542c | (R)-enoyl-CoA hydratase | C, D, E, F | 54, 55, 99 | |

| fadA5 | Rv3546 | thiolase | B, C, D, E, F | 34 |

| fadA6 | Rv3556c | thiolase | E |

. Bioinformatic annotation

. Recombinant expression and enzymatic function confirmed

. Function examined with mutant strain in vivo

. Required for growth on cholesterol 35

. Upregulated by cholesterol 34

. Growth phenotype in vivo

. No growth phenotype in vivo

. Growth phenotype in macrophages 101

The genes encoding proteins required for the metabolism of 2-hydroxy-hexa-2,4-dienoic acid have been proposed to be HsaEFG based on the high amino acid identity to TesEGF responsible for the formation of pyruvate and propionate via 4-hydroxy-2-oxohexanoic acid in C. testosteroni 42, 44. The activities of HsaEFG have not been verified and gene mutants reveal that hsaEFG are not required for growth on cholesterol 35. The metabolic fate of DOHNAA in M. tuberculosis is unknown. Studies in Rhodococcus equi suggest the propionate moiety of DOHNAA is metabolized by β-oxidation 45, 46. FadE30 is hypothesized to be the acyl-CoA dehydrogenase responsible for the dehydrogenation step of DOHNAA 46. It has been suggested that metabolism of the C and D rings initiates by lactonization of the cyclic carbonyl by a Baeyer-Villiger monooxygenase (BVMO) 42. The BVMO in M. tuberculosis has not been identified and the cholesterol regulon lacks an obvious gene candidate, therefore requiring furhter functional characterization studies.

In the 1960s, Sih et al. characterized partially metabolized side chain intermediates from Nocardia cultured with cholesterol 47-49. These studies established that complete metabolism of the cholesterol side chain proceeds through C24 and C22 β-oxidation intermediates (Figure 3), however little is known of the genes encoding the enzymes involved in the oxidation of the side chain because early studies lacked protein sequence information. Even with sequence data now available, gene assignment is complicated due to the large number of annotated fatty acid oxidation genes 42. In order for the side chain to undergo β-oxidation it must first be activated and converted to a CoA thioester. The side chain is first activated by conversion to the carboxylic acid by cytochrome P450 Cyp125 50, 51. However, in some M. tuberculosis strains Cyp142 can compensate for loss of Cyp125 52. The acyl-CoA synthetase responsible for the subsequent conversion to the CoA thioester has not been identified. Bacterial β-oxidation includes four enzymatic steps including an acyl-CoA dehydrogenase (FadE), an enoyl-CoA-hydratase (EchA), a 3-hydroxy-acyl-CoA-dehydrogenase (FadB), and a 3-keto-acyl-CoA thiolase (FadA). Similar to other actinomycetes, it has been impossible to assign specific genes to β-oxidation of the cholesterol side chain from sequence data alone. Indeed, the M. tuberculosis genome contains a broad family of β-oxidation genes consisting of 36 acyl-CoA dehydrogenase (fadE), 21 (S)-specific enoyl-CoA hydratase (echA), four 3-hydroxy-acyl-CoA dehydrogenase (fadB), and six 3-keto-acyl-CoA thiolase (fadA) genes 1. In addition, there are 36 acyl-CoA ligases (fadD) that generate the acyl-CoA thioester that enters into the β-oxidation cycle. The number of functionally-redundant enzymes prohibits assignment of enzymes to specific steps in cholesterol metabolism. Thiolase, FadA5, is required for full metabolism of the side chain of cholesterol and in vitro catalyzes thiolysis of acetoacetyl-CoA 34.

Figure 3.

Cholesterol metabolism in mycobacteria.

The intracellular growth (igr) operon is required for growth of M. tuberculosis on cholesterol and growth of igr operon-disrupted mutant strain is attenuated in resting macrophages and early in the infection process in immunocompetent mice 53, 54. FadE28 and FadE29, encoded by two cistronic genes residing in the igr operon, are annotated as potential acyl-CoA dehydrogenases. Investigation of the biochemical function of the igr operon demonstrated that FadE28 and FadE29 form a quaternary complex 55 resulting in a functional acyl-CoA dehydrogenase, which is specific for steroid-derived substrates. This is the first report of a heteromeric ACAD complex forming a single acyl-CoA dehydrogenase enzyme. All known ACADs form homotetrameric assemblies comprised of ∼43 kDa monomers. One exception is the sub-families of very long chain ACADs (VLCAD and VLCAD2) that form a homodimer from ∼73 kDa monomers 56, 57. In addition Rv3541c and Rv3542c, encoded by the igr operon, with similarity to (R)-specific enoyl-CoA hydratases, form a heteromeric complex 55. It is an active hydratase and we have solved the three-dimensional structure by X-ray crystallography (Yang, Thomas, Garcia-Diaz, Sampson, personal communication). We have undertaken a fuller bioinformatic analysis to investigate conservation of individual residues in binding sites in annotated β-oxidation enzymes. In combination with operonic context, we have successfully identified additional heteromeric complexes that are encoded by cholesterol-regulated genes (Wipperman, Thomas, Yang, Sampson, personal communication). Notably, these studies, as well as other ongoing studies, indicate that one enzyme function is often encoded by at least two genes that encode two chains in a single protein complex. This paradigm is in contrast to the classical, well-characterized b-oxidation enzymes of eukaryotes that are homomeric, thus requiring functional characterization.

Areas of contribution to Category II. Non-metabolic functions assigned to genes

Regulation of septum formation

While homology searches of the M. tuberculosis genome identified many of the septum components needed for cell division, the lack of verified homologs of typically conserved cell division proteins in M. tuberculosis indicates that either the M. tuberculosis division-system is unique and consists of fewer or uncharacterized proteins, or that these components cannot be identified via sequence similarity approaches. Notably, the proteins that have not yet been identified fall into two groups, those that interact with FtsZ and regulate septum site selection and modulation of Z-ring formation, and those that play a structural role in tethering the septal ring to the cell wall. The inability of sequence similarity-based annotation efforts to identify genes encoding these proteins indicates that the corresponding M. tuberculosis proteins share limited global similarity to counterparts in other bacterial and model organisms. Since identity alone is insufficient for the identification of these proteins, cell division apparatus assembly was identified as an area of focus by TBCAP.

Septum assembly at the step of FtsZ polymerization is controlled by direct interaction with a number of proteins including ZipA, ZapA, FtsA, Min-protein complex, EzrA, MipZ and SulA. A multidisciplinary experimental approach consisting of bioinformatics modeling, and transcriptional mapping and experimental evaluation was required to identify and substantiate gene candidates that are involved in septum regulation (Table 4). For example the protein Ssd encoded by rv3660c has been shown to be septum site determining protein involved in a unique response that includes the dormancy regulon and alternative sigma factors 58. The protein encoded by rv1708 is a SoJ-like protein that negatively regulates cell division and elicits adaptive responses including a toxin-antitoxin loci (Slayden & Crew, Unpublished). Similarly, rv2216 encodes a protein that show similarity with the SOS response regulator SulA over the epimerase domain, but has an additional C-terminal p-fam #DUF 1731 domain characteristic of proteins implicated in inhibition of cell division (Slayden & Crew, Unpublished). Experimental studies in mycobacteria support the functional annotation that rv2216 encodes a protein involved in cell division regulation, but its precise regulatory role remains undefined. While the genes encoding these proteins appear to be distant homologs they are all capable of halting cell cycle progression and coupling cell cycle progression with alternative growth conditions. Notably, experimental observations of these cell cycle regulatory elements indicates that they participate in modulating cell cycle progression and overall growth in response to stress and alternative growth conditions

Table 4.

Genes encoding cell division regulatory and cell division machinery proteins in M. tuberculosis.

| ORF | gene name | Additional information | Bibliography | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| rv2150c | FtsZ | Cell division protein, Z-ring complex Ib | PMID: 19656808,PMID: 18479968,PMID: 18436955,PMID: 17644520,PMID: 16735741,PMID: 15774900 | |

| rv3102c | FtsE | Cell division protein, Z-ring complex Ia | PMID: 21336990,PMID: 16416128 | |

| rv3101c | FtsX | Cell division protein, Z-ring complex Ib | PMID: 16416128 | |

| rv2748c | FtsK | Cell division protein, Z-ring complex Ib | ||

| rv2345 | ZipA-like | Cell division protein, Z-ring complex Ib | PMID: 16735741 | |

| rv3835 | ZipA-like | Cell division protein, Z-ring complex Ib | PMID: 16735741 | |

| rv3645 | FtsA-like | Cell division protein, Z-ring complex Ib | PMID: 16735741 | |

| rv2151c | FtsQ | Cell division protein, QLB complex | ||

| rv2164c | FtsL | Cell division protein, QLB complex | PMID: 17427288 | |

| rv1024 | FtsB | Cell division protein, QLB complex | ||

| rv2154 | FtsW | Cell division protein, PG complex | PMID: 17427288,PMID: 17427288 | |

| rv2163c | FtsI | Cell division protein, PG complex | PMID: 19109339 | |

| rv3660c | Ssd | Septum site determining protein, ssd | PMID: 16735741,PMID: 21504606 | |

| rv1708 | Soj-like protein | Initiation inhibition protein, septum site regulation | PMID: 16735741 | |

| rv2216 | cdr | septum site regulation, cdi cell division inhibitor | ||

| rv2719c | ChiZ | cell wall hydrolase | PMID: 22094151,PMID: 16942606 | |

| rv0019c | FipA | FtsZ-interacting protein A, FipA | PMID: 20066037 | |

| rv0011c | CrgA | Cell division protein, PG complex | PMID: 21531798 | |

Many of the genes that encode proteins that remain to be functionally characterized play a structural role or participate in localization and cell wall remodeling of the septum site. The seemingly lack of key cell division proteins is interesting considering that cell division septum protein complexes are preassembled and then recruited to complete the cell division apparatus. The first proteins to interact are FtsZ, FtsA and ZipA to form the Z-ring complex on the cytoplasmic side of the plasma membrane 59, 60. Obvious FtsA and ZipA homologs have yet to be described in M. tuberculosis. The best ZipA candidates in M. tuberculosis are encoded by rv2345 and rv3835, and are annotated as hypothetical proteins. It has been demonstrated that both FtsA and ZipA are necessary in recruitment of many of the remaining cell division complexes. Some confusion arises because early studies suggested that FtsA and ZipA can be bypassed for recruitment of other division proteins, however it is now thought that these proteins serve an important function by facilitating assembly of the Z-ring by preventing disassembly and allowing association with other cell division components and complexes. Overall, bioinformatics analysis of the M. tuberculosis genome reveals that M. tuberculosis lacks critical components involved in site determination and each of the subcomplexes that ultimately form the complete division-system. It is important to remember that all Fts-proteins impact the bacteria's ability to divide properly, which is why absence of any individual component results in compromised cell division and filamentation. The enigma in the biology of M. tuberculosis cell division in the absence of experimental information is, how does cell division occur properly when so many Fts-proteins appear to be lacking?

TA loci in mycobacteria

Increasingly, toxin:antitoxin (TA) loci have been implicated for their role in stress responses in bacteria 61. Although TA loci were originally described as plasmid maintenance factors 62, 63, seven distinct types of TA families categorized by molecular mechanism have now been described (ccd, relBE, parDE, higBA, mazEF, phd/doc, vapBC) in bacterial systems61. Although TA pairs are widely found throughout prokaryotic genomes studied to date 64, they are present in unusually high numbers in the M. tuberculosis genome. A recent and comprehensive study predicts 88 putative TA loci, while demonstrating that 30 of these are capable of inhibiting growth in M. smegmatis (approximately 66% of those studied belonging to the Vap family, and the remaining 34% belonging to the Hig, Maz, Rel, and novel TA families) 65. The TBCAP jamboree annotated 77 TA loci from 5 families. Further, the high number of TA loci in mycobacteria seems to be restricted to those species within the Mycobacterium tuberculosis Complex (MTBC) and present only in significantly lower numbers in other mycobacterial species, suggesting that they may have a role in adaptation to growth, non-replicating persistence and clinical latency 65. This raises intriguing questions: Why does M. tuberculosis contain so many TA loci, what instigates their activity, and what advantage do they provide to the bacterium during the infection and disease process? The recent finding that ten of the mRNAse encoding TA loci in Escherichia coli could be knocked out successively, gradually decreasing the level of persister cell formation with each deletion, suggests that there is some degree of functional redundancy 66.

There are different types of TA loci that stall translation by inhibiting rRNA function. The best characterized is the RelE toxin which binds 16S rRNA and associates with the A site of the ribosome, stalling translation and preferentially cleaving ribosomal associated mRNA at the stop codon 67, 68. A closely related member to RelE is the YoeB toxin. These two toxins appear to be similar at the structural level yet, YoeB functions by binding the 50S ribosomal subunit to inhibit translation initiation 69. Both of these toxins show mRNase activity dependent upon ribosomal binding and several orthologues of YoeB in E. coli have shown ribosomal-independent mRNase activity 69, 70. A third member in this grouping is the Doc toxin. In E. coli, Doc mimics the RelE toxin in that it binds the 30S ribosomal subunit and inhibits translation elongation 71. It is quite unique in comparison to the RelE toxin because it lacks any capacity for RNA degradation and in fact has been shown to assist in the preservation of ribosomal bound mRNA 71. These three paralogs in M. tuberculosis have only recently been characterized and may contain mechanistic components from each of the three previously described types. In sharp contrast, the three cognate antitoxins, RelB, YefM, and PhD, are believed to operate through a mechanism known as the order-disorder binding model 72, 73. Their sequence suggests a rather unstructured protein, but upon binding a stabilized three-dimensional structure forms which inhibits ribosomal binding of the toxin through steric hindrance and enhances the stability of the antitoxin. Most importantly, the redundancy of these operons in the M. tuberculosis genome suggests that they are vital in regulation at the translational level and post-transcriptional level as it pertains to the persistent lifestyle of M. tuberculosis.

The non-growing, dormant phenotype of bacterial persistence has now been widely associated with the non-replicating persistent state that is characteristic of M. tuberculosis infection 74. Only quite recently have studies been able to demonstrate that TA loci, specifically those with mRNAse activity, are responsible for reversible bacterial persistence in the E. coli model 66. In E. coli, accumulation of MazF is induced by amino acid starvation and other nutritional stresses 75, 76. However, the specific circumstance(s) responsible for induction of specific TA loci has not been thoroughly evaluated for all bacterial species, including M. tuberculosis. The TA loci of M. tuberculosis have been the focus of increasing attention 65, 77-79, however a thorough examination of the regulation and function of these loci has not been carried out and relatively little is known about which environmental conditions result in the induction of TA loci and which cellular processes they are associated with resulting in specific phenotypic outcomes. Several studies have examined the induction of specific TA loci in response to a specific stress or stresses 65, 80, or global transcriptional changes in response to several types of stress 81. However, a difficult aspect of M. tuberculosis research is that in vitro conditions may not completely or accurately reflect all of the conditions and stresses encountered in the host during infection.

Areas of contribution to Category III. Genes with no metabolic function assigned

An area of functional annotation that requires attention in the future is functional assignment of ORFs grouped to category III. Category III contains a large number of ORFs currently described as conserved hypothetical proteins (n=883), conserved membrane protein (N=220), conserved membrane transport protein (n=7), conserved secreted protein (n=12), hypothetical exported protein (n=19), hypothetical protein (n=256), membrane protein (n=45), PE-PGRS and PPE (n=163), transcriptional activator (n=113) and transmembrane protein (n=16) in addition to other ORFs with limited information about function. While, many of the ORFs in this category may be rapidly assigned to a metabolic process, experimental evidence discerning its precise role in that process is still limiting. In the upcoming years, it is anticipated that experimental studies will significantly contribute to assigning the ORFs in this category; serving in many was as a metric for successful reannotation.

Areas of contribution to Category IV. Metabolic functions or pathways or end-products not fully defined in terms of responsible genes and corresponding enzymes

Many of the well-known metabolic pathways of Mycobacterium spp qualify under this definition in that not all functions have been accounted for. For instance, in the well known biosynthetic pathway of LAM and related glycoconjugates not all of the acyl functions have been defined genetically and enzymatically, nor the exact roles of EmbC (Rv3793) or AftD (Rv0236c) 5. Likewise, the biosynthetic precursors of such cell wall products as LAM and related arabinogalactan (AG), and most of the phthiocerol-containing lipids, must traverse the cytoplasmic/inner membrane. However, little is known of the responsible transporters. Only in the case of trehalose monomycolate (TMM), the precursor of trehalose dimycolate (TDM) and the mycolates of the cell wall core (mAGP) is there definite evidence that MmpL is the responsible transporter 82, 83. Also, a small drug resistant (SMR)-like transporter Rv3789 appears to be involved in the reorienting of decaprenol phosphate arabinose to the periplasm 84. There is the possibility that some of the enzymes involved in glycosyl chain elongation and encoded by known genes, at least in the case of LAM/LM, such as rv2174, rv1459c, and embC(rv3793) in the context of Araf additions, may themselves have transport roles. It should be noted that rv1459c (MptB in Corynebacterium glutanicum) is part of an operon consisting of several ORFs (rv1459c; rv1457c; rv1456c) encoding an ABC transporter, raising the possibility of a functional coupling of the glycosyltransferases with ABC transporters 85. Functional and genetic definition of the transporters involved in the membranous and extra-membranous events of de novo cell wall synthesis and assembly is the next great challenge in this epic odyssey. Indeed, crucial events in final cell wall assembly, the ligation of the polyprenyl-P linked arabinogalactan complex to nascent peptidoglycan and definition of the stage at which the mycolates are attached, await genetic and biochemical explanation.

A question posed by TBCAP participants is whether products and pathways long associated with NTMs (non-tuberculosis mycobacteria) but apparently absent from M. tuberculosis based on lack of chemical evidence, do in fact have a genetic basis and can account for some of the many non-annotated genes. The glycosyl diacylglycerols have long been a hallmark of Gram positive bacteria and were never found in Gram positive bacteria or mycobacteria. Yet, Hunter et al. 86 described a 1,2-diacyl-[β-D-glucopyranosyl(1”- 6′)- β-D-glucopyranosyl(1′-3)]-sn-glycerol. The genes responsible for the expected steps in the biosynthesis of this diglucosyl diacylglycerol have not been identified. Likewise the hallmarks of all members of the M. avium complex are the so-called C-mycoside glycopeptidolipids, and most of the rapidly growing NTMs are characterized by the trehalose-containing lipooligosaccharides (LOS) 87. Although there is no chemical evidence of these in M. tuberculosis growing under a variety of conditions, preliminary data indicates that some of the unannotated glycosyltransferases of the GT-A or –B or C classes may encode chemically undetectable amounts of these products.

Another topic of mycobacterial physiology awaiting full gene annotation is the intriguing cytoplasmic polymethylated polysaccharides (PMPs) composed of two classes, fully chemically characterized, the 3-O-methylmannose polysaccharides (MMPs) and the 6-O-methyglucose lipopolysaccharides (MGLPs); apparently M. tuberculosis is devoid of the PMPs. The existence of two clusters of genes dedicated to the biosynthesis of MGLP and other α-(1-4) glucans in M. tuberculosis has been reported (9). However, only the partial functional characterization of three genes, rv3032, rv1208 and rv3030, has been achieved. Putative functions have been attributed to other genes in the clusters. MGLPs are unique in the acylation of the non-reducing end by a combination of small aliphatic acids, acetate, propionate, isobutyrate, octonate, succinate, features awaiting full genetic and metabolic definition.

Another perspective on the topic of Category IV genes is to review the older literature on the physiology of M. tuberculosis, an era mostly devoted to chemical definition of products, such as the work from the 1940s-1980s, by such as Rudolph J. Anderson, Jean and Cecile Asselineau, Edgar Lederer, and so on. Substances were identified in these days no longer mentioned such as Wax A, Wax B, Wax C, Wax D 88. It is now clear that the main components of Wax A are the phthiocerol-containing lipids with some triacyl glycerols and free mycolic acids; Wax B consists mainly of triacyl glycerols; Wax C is mainly trehalose dimycolate/cord factor. Wax D, noted for its adjuvant activity, is also a heterogeneous mixture of now known mycobacterial products, but dominated by oligomeric components of the cell wall core. Thus, the only true waxes or cerides is restricted to the Wax A, the diesters of phthiocerol and the methyl branched fatty acids. The genetics of the synthesis of all of these products are now classified under Categories I-III.

The question of whether M. tuberculosis is not at all chromogenic or marginally so has not been fully decided; they are not constitutively chromogenic. Intensive work on the structures of mycobacterial carotenoids extends back to such as E. Chargaff in 1930 and the topic has been well reviewed from structural, biosynthetic and functional perspectives 89. The genetics of mycobacterial carotenoid biosynthesis has long defied definition. However, there has been recent preliminary progress in annotation of genes thought to be responsible for known enzymatic transformations 90.

Conclusions

It was once thought that genomic information alone would present all the information needed and in combination with bioinformatics provide sufficient detail into functional characterization of processes encoded in the M. tuberculosis genome. In recent years, it has become clear that the next steps in the post-genomic era are community re-annotation efforts and curation, and experimental verification of gene function. This is particularly important because functional characterization provides a foundation for further characterization of metabolic pathways, the role of moonlighting proteins, and the intricate regulation that allows phenotypic diversity under alternative growth conditions. Considering all the existing gene annotations and experimental information, previously undefined genes encoding proteins can continue to be assigned to biological functions in context with the overall coding capacity.

One of the biggest challenges in completing the annotation of the cell envelope-related processes encoded by the M. tuberculosis genome beyond the identification of the missing biosynthetic enzymes, will be the identification of the transporters, including OM proteins, required for the import of nutrients and translocation of biosynthetic precursors or end-products from their site of production, for the most part cytoplasmic, to their final location in the cell envelope, either on the periplasmic side of the plasma membrane, in the periplasm or in the OM and ‘capsule’. More than 148 transport associated proteins belonging to 33 major transporter families were identified in the genome of M. tuberculosis H37Rv (http://www.membranetransport.org/). The present genome annotation was also updated with 134 bioinformatically-predicted OM proteins. Inherent to all bioinformatics studies, however, these predictions come with a number of potential inaccuracies, but serve as a guide for experimental verification. Nevertheless, it is becoming increasingly clear from the current genome annotation and the analysis of the few mycobacterial transporters characterized to date that, most likely due to the particular structure and composition of its cell envelope, M. tuberculosis is endowed with transporters that are relatively restricted to Mycobacteria, both for the import of exogenous substrates and the export of some particular families of proteins and (glyco)lipids (e.g., the Mce proteins, the ESX secretion systems, the MmpL proteins). The transporters involved in uptake and efflux processes, including those required for the building of the cell envelope, are thus to be found in a long and diverse list of candidate genes with or without any homologs in other prokaryotes. Other challenges include the apparently very low expression levels of OMPs, which makes their identification by proteomic approaches difficult.

Another area where much remains to be done is in understanding the genetic basis underlying the cell envelope's constant remodeling (including degradation and recycling) which accompanies cell division or any changes in the metabolism and lifestyle of the bacterium following host infection or exposure to various environmental stresses. Key to the understanding of these processes will be the identification of the regulatory elements controlling these changes. Evidence gathered from the phenotypic analysis of mutants deficient in transcriptional regulators or the study of biosynthetic enzymes suggests that this regulation occurs both at the transcriptional and at the post-translational levels 91, 92.

The bacterial cell cycle involves the organization of cell wall and macromolecular synthesis, with septum formation and cell wall remodeling. Each of these processes is coordinated through complex regulatory networks. The lack of M. tuberculosis orthologs of the E. coli or B. subtilis cell division complexes and regulatory networks indicates that there are several unidentified “checkpoints” and that chromosome replication and cell division are coordinated as early as at the level of Z-ring assembly in M. tuberculosis. It is likely that M. tuberculosis encodes FtsZ regulating mechanisms that fulfill these functions, but they are not overtly obvious from DNA sequence alone, thus functionally equivalent M. tuberculosis orthologs or functional cognates remain to be identified. Recent experimental studies have identified several related cell division inhibitory proteins that are controlled through regulatory coupling with other cell cyle processes. Importantly, these proteins utilize similar regulatory mechanims althought they are part of different bacterial responses. Clearly, the regulation and underlying molecular mechanisms are just beginning to emerge in M. tuberculosis. Many questions about the regulation of DNA replication/segregation and septum formation remain unsolved, even largely uninvestigated, particularly in pathogenic organisms such as M. tuberculosis. Questions concerning the mycobacterial cell cycle in terms of what regulatory components [annotated or unannotated] in M. tuberculosis play a role in the complex regulatory network governing cell cycle progression, what promoter sequences and motifs are responsible for temporal timing of events, and what is the mechanism by which initiation of cell division is coordinated and coupled with DNA replication still remain to be answered.

An area that has become more recognized in M. tuberculosis research in recent years pertains to the role toxin:antitoxin loci play in regulation and stress responses. It is generally thought that chromosomally encoded TA loci participate with other regulatory mechanisms to create rapid responses to stresses. For example, there is increasing evidence that TA loci particpate in regulation through targeted transcriptional degradtion and proteome remodeling. Uniquely, M. tuberculosis appears to encode a large number of TA loci in multiple families. The large number of TA loci results in a complexity that is difficult to address with basic molecular approaches. Arguably, the multiple TA loci in each family provides finite control under diverse growth conditions. In addition, it appears that orphan TA components are also encoded in the TB genome. Characterization of the TA loci networks and the specific role they play in adaptive metabolism in M. tuberculosis promises to be a major challenge in coming years.

The Aim of TBCAP 2012 was to launch the concept of a community curation project. The goal of TBCAP is not to overwrite previous annotation efforts, but rather it is to spur all of us towards completion of the functional annotation of the M. tuberculosis genome. For this to be completed in a timely manner, it will require effort from all in the TB research community. Therefore, a major goal in the upcoming years is to expand the TBCAP community, curate the data in transparent ways, and insist on accurate experimental functional characterization of genes. The information from this approach promises to significantly impact the development of new drugs, effective vaccines, and improve diagnostics for M. tuberculosis.

Acknowledgments

The top annotators (100 annotations or more) are sorted by number of annotations contributed:

yamir.moreno: 7423

shahanup86: 2424

hibeeluck: 2232

jhum4u2006: 2054

singhpankaj2116: 1745

njamshidi: 1423

sourish10: 1355

ashwinigbhat: 1057

priti.priety: 935

mjackson: 777

rslayden: 731

priyadarshinipriyanka2001: 646

ahal4789: 631

extern:JZUCKER: 531

jlew: 507

jjmcfadden: 482

kholia.trupti: 429

akankshajain.21: 393

harsharohiratruefriend: 375

vmevada102: 259

gaurisd10: 238

yashabhasin: 233

vashishtrv: 224

gaat3s: 204

aparna.vchalam: 201

prabhakarsmail: 184

vijayachitra: 178

swetha.r: 168

ravirajsoni: 138

vmizrahi: 131

kaveri.verma: 117

dreamsbeyondinfinity: 117

Most of the top annotators were from the OSDD. Exceptions were

Yamir Moreno (PLoSONE article on the transcriptional regulatory network of Mtb),

Njamshidi (MTB metabolic model),

Johnjoe McFadden (MTB metabolic model)

Jeremy Zucker TBDB

Richard Slayden CSU

Val Mizrahi (HHMI)

Mary Jackson CSU

Contributor Information

Richard A. Slayden, Colorado State University, Fort Collins, CO

Mary Jackson, Colorado State University, Fort Collins, CO.

Jeremy Zucker, Broad Institute of MIT and Harvard.

Melissa V. Ramirez, Colorado State University, Fort Collins, CO

Clinton Dawson, Colorado State University, Fort Collins, CO.

Nicole Sampson, Stony Brook University, Fort Collins, CO.

Suzanne T. Thomas, Stony Brook University, Fort Collins, CO

Neema Jamshidi, University of California, San Diego.

Peter Sisk, Broad Institute of MIT and Harvard.

Ron Caspi, SRI International.

Dean C. Crick, Colorado State University, Fort Collins, CO

Michael R. McNeil, Colorado State University, Fort Collins, CO

Martin S. Pavelka, University of Rochester Medical Center, Rochester, NY

Michael Niederweis, University of Alabama at Birmingham, AL.

Axel Siroy, University of Alabama at Birmingham, AL.

Valentina Dona, NIH/NIAID, Bethesda.

Johnjoe McFadden, University of Surrey, Guildford, UK.

Helena Boshoff, NIH/NIAID, Bethesda.

References

- 1.Cole ST, Brosch R, Parkhil J, Garnier T, Churcher C, Harris D, Gordon SV, Eiglmeier K, Gas S, Barry CE, 3rd, Tekaia F, Badcock K, Basham D, Brown D, Chillingworth T, Connor R, Davies R, Devlin K, Feltwell T, Gentles S, Hamlin N, Holroyd S, Hornsby T, Jagels K, Krogh A, McLean J, Moule S, Murphy L, Oliver K, Osborne J, Quail MA, Rajandream MA, Rogers J, Rutter S, Seeger K, Skelton J, Squares R, Squares S, Sulston JE, Taylor K, Whitehead S, Barrell BG. Deciphering the biology of Mycobacterium tuberculosis from the complete genome sequence. Nature. 1998;393:537–544. doi: 10.1038/31159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Camus JC, Pryor MJ, Medigue C, Cole ST. Re-annotation of the genome sequence of Mycobacterium tuberculosis H37Rv. Microbiology. 2002;148:2967–2973. doi: 10.1099/00221287-148-10-2967. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mazumder R, Natale DA, Julio JA, Yeh LS, Wu CH. Community annotation in biology. Biol Direct. 5:12. doi: 10.1186/1745-6150-5-12. doi: 1745-6150-5-12[pii] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kaur D, Guerin ME, Skovierova H, Brennan PJ, Jackson M. Chapter 2. Biogenesis of the cell wall and other glycoconjugates of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Adv Appl Microbiol. 2009;69:23–78. doi: 10.1016/S0065-2164(09)69002-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kaur D, Guerin ME, Skovierova H, Brennan PJ, Jackson M. Chapter 2: Biogenesis of the cell wall and other glycoconjugates of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Advances in applied microbiology. 2009;69:23–78. doi: 10.1016/S0065-2164(09)69002-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Birch HL, Alderwick LJ, Bhatt A, Rittmann D, Krumbach K, Singh A, Bai Y, Lowary TL, Eggeling L, Besra GS. Biosynthesis of mycobacterial arabinogalactan: identification of a novel a(1->3) arabinofuranosyltransferase. Mol Microbiol. 2008;69:1191–1206. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2008.06354.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Birch HL, Alderwick LJ, Appelmelk BJ, Maaskant J, Bhatt A, Singh A, Nigou J, Eggeling L, Geurtsen J, Besra GS. A truncated lipoglycan from mycobacteria with altered immunological properties. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107:2634–2639. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0915082107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zuber B, Chami M, Houssin C, Dubochet J, Griffiths G, Daffe M. Direct visualization of the outer membrane of mycobacteria and corynebacteria in their native state. J Bact. 2008;190:5672–5680. doi: 10.1128/JB.01919-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hoffmann C, Leis A, Niederweis M, Plitzko JM, Engelhardt H. Disclosure of the mycobacterial outer membrane: cryo-electron tomography and vitreous sections reveal the lipid bilayer structure. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105:3963–3967. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0709530105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Simeone R, Bottai D, Brosch R. ESX/type VII secretion systems and their role in host-pathogen interaction. Current Opinion in Microbiology. 2009;12:4–10. doi: 10.1016/j.mib.2008.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Banerjee S, Farhana A, Ehtesham NZ, Hasnain SE. Iron acquisition, assimilation and regulation in mycobacteria. Infect Genet Evol. 2011;11:825–838. doi: 10.1016/j.meegid.2011.02.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tian C, Jian-Ping X. Roles of PE_PGRS family in Mycobacterium tuberculosis pathogenesis and novel measures against tuberculosis. Microb Pathog. 2010;49:311–314. doi: 10.1016/j.micpath.2010.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Niederweis M. Nutrient acquisition by mycobacteria. Microbiology. 2008;154:679–692. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.2007/012872-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pages JM, James CE, Winterhalter M. The porin and the permeating antibiotic: a selective diffusion barrier in Gram-negative bacteria. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2008;6:893–903. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro1994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Danilchanka O, Pavlenok M, Niederweis M. Role of porins for uptake of antibiotics by Mycobacterium smegmatis. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2008;52:3127–3134. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00239-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sharff A, Fanutti C, Shi J, Calladine C, Luisi B. The role of the TolC family in protein transport and multidrug efflux. From stereochemical certainty to mechanistic hypothesis. Eur J Biochem. 2001;268:5011–5026. doi: 10.1046/j.0014-2956.2001.02442.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Song H, Sandie R, Wang Y, Andrade-Navarro MA, Niederweis M. Identification of outer membrane proteins of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Tuberculosis. 2008;88:526–544. doi: 10.1016/j.tube.2008.02.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Faller M, Niederweis M, Schulz GE. The structure of a mycobacterial outer-membrane channel. Science. 2004;303:1189–1192. doi: 10.1126/science.1094114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Guo XV, Monteleone M, Klotzsche M, Kamionka A, Hillen W, Braunstein M, Ehrt S, Schnappinger D. Silencing essential protein secretion in Mycobacterium smegmatis by using tetracyclin repressors. J Bacteriol. 2007;189:4614–4623. doi: 10.1128/JB.00216-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wimley WC. The versatile beta-barrel membrane protein. Curr Opin Struct Biol. 2003;13:404–411. doi: 10.1016/s0959-440x(03)00099-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Koronakis V, Eswaran J, Hughes C. Structure and function of TolC: the bacterial exit duct for proteins and drugs. Annu Rev Biochem. 2004;73:467–489. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.73.011303.074104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Collins RF, Derrick JP. Wza: a new structural paradigm for outer membrane secretory proteins? Trends Microbiol. 2007;15:96–100. doi: 10.1016/j.tim.2007.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Akama H, Kanemaki M, Yoshimura M, Tsukihara T, Kashiwagi T, Yoneyama H, Narita S, Nakagawa A, Nakae T. Crystal structure of the drug discharge outer membrane protein, OprM, of Pseudomonas aeruginosa: dual modes of membrane anchoring and occluded cavity end. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:52816–52819. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C400445200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mah N, Perez-Iratxeta C, Andrade-Navarro MA. Outer membrane pore protein prediction in mycobacteria using genomic comparison. Microbiology. 2010;156:2506–2515. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.040089-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Niederweis M, Danilchanka O, Huff J, Hoffman C, Engelhardt H. Mycobacterial outer membranes: in search of proteins. Trends Microbiol. 2010;18:109–116. doi: 10.1016/j.tim.2009.12.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Raynaud C, Papavinasasundaram KG, Speight RA, Springer B, Sander P, Bottger EC, Colston MJ, Draper P. The functions of OmpATb, a pore-forming protein of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Mol Microbiol. 2002;46:191–201. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2002.03152.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Senaratne RH, Mobasheri H, Papavinasasundaram KG, Jenner P, Lea EJ, Draper P. Expression of a gene for a porin-like protein of the OmpA family from Mycobacterium tuberculosis H37Rv. J Bacteriol. 1998;180:3541–3547. doi: 10.1128/jb.180.14.3541-3547.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Teriete P, Yao Y, Kolodzik A, Yu J, Song H, Niederweis M, Marassi FM. Mycobacterium tuberculosis Rv0899 adopts a mixed alpha/beta-structure and does not form a transmembrane beta-barrel. Biochemistry. 2010;49:2768–2777. doi: 10.1021/bi100158s. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yao Y, Barghava N, Kim J, Niederweis M, Marassi FM. Molecular structure and peptidoglycan recognition of Mycobacterium tuberculosis ArfA (Rv0899) J Mol Biol. 2012;416:208–220. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2011.12.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Song H, Huff J, Janik K, Walter K, Keller C, Ehlers S, Bossmann SH, Niederweis M. Expression of the ompATb operon accelerates ammonia secretion and adaptation of Mycobacterium tuberculosis to acidic environments. Mol Microbiol. 2011;80:900–918. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2011.07619.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Siroy A, Mailaender C, Harder D, Koerber S, Wolschendorf F, Danilchanka O, Wang Y, Heinz C, Niederweis M. Rv1698 of Mycobacterium tuberculosis represents a new class of channel-forming outer membrane proteins. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:17827–17837. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M800866200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Eisenreich W, Dandekar T, Heesemann J, Goebel W. Carbon metabolism of intracellular bacterial pathogens and possible links to virulence. Nature reviews Microbiology. 2010;8:401–412. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro2351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rhee KY, de Carvalho LP, Bryk R, Ehrt S, Marrero J, Park SW, Schnappinger D, Venugopal A, Nathan C. Central carbon metabolism in Mycobacteriumtuberculosis: an unexpected frontier. Trends in microbiology. 2011;19:307–314. doi: 10.1016/j.tim.2011.03.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Nesbitt N, Yang X, Fontán P, Kolesnikova I, Smith I, Sampson NS, Dubnau E. A thiolase of M tuberculosis is required for virulence and for production of androstenedione and androstadienedione from cholesterol. Infect Immun. 2010;78:275–282. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00893-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Griffin JW, Gawronski JD, DeJesus MA, Ioerger TR, Akerley BJ, Sassetti CM. High-resolution phenotypic profiling defines genes essential for mycobacterial growth and cholesterol catabolism. PLoS Pathog. 2011;7:e1002251. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Yang X, Dubnau E, Smith I, Sampson NS. Rv1106c from Mycobacterium tuberculosis is a 3β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase. Biochemistry. 2007;46:9058–9067. doi: 10.1021/bi700688x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Yang X, Gao J, Smith I, Dubnau E, Sampson NS. Cholesterol is not an essential source of nutrition for Mycobacterium tuberculosis during infection. J Bacteriol. 2011;193:1473–1476. doi: 10.1128/JB.01210-10. doi: JB.01210-10 [pii] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Knol J, Bodewits K, Hessels GI, Dijkhuizen L, van der Geize R. 3-Keto-5α-steroid Δ1-dehydrogenase from Rhodococcus erythropolis SQ1 and its orthologue in Mycobacterium tuberculosis H37Rv are highly specific enzymes that function in cholesterol catabolism. Biochem J. 2008;410:339–346. doi: 10.1042/BJ20071130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Capyk JK, D'Angelo I, Strynadka NC, Eltis LD. Characterization of 3-ketosteroid 9α -hydroxylase, a Rieske oxygenase in the cholesterol degradation pathway of Mycobacteriumtuberculosis. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:9937–9946. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M900719200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Dresen C, Lin LY, D'Angelo I, Tocheva EI, Strynadka N, Eltis LD. A flavin-dependent monooxygenase from Mycobacterium tuberculosis involved in cholesterol catabolism. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:22264–22275. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.099028. doi: M109.099028 [pii] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Yam KC, D'Angelo I, Kalscheuer R, Zhu H, Wang JX, Sneickus V, Ly LH, Converse PJ, Jacobs WR, Jr, Strynadka N, Eltis LD. Studies of a ring-cleaving dioxygenase illuminate the role of cholesterol metabolism in the pathogenesis of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. PLoS Pathog. 2009;5:e1000344. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Van der Geize R, Yam K, Heuser T, Wilbrink MH, Hara H, Anderton MC, Sim E, Dijkhuizen L, Davies JE, Mohn WW, Eltis LD. A gene cluster encoding cholesterol catabolism in a soil actinomycete provides insight into Mycobacterium tuberculosis survival in macrophages. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2007;104:1947–1952. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0605728104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lack NA, Yam KC, Lowe ED, Horsman GP, Owen RL, Sim E, Eltis LD. Characterization of a carbon-carbon hydrolase from Mycobacterium tuberculosis involved in cholesterol metabolism. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:434–443. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.058081. doi: M109.058081 [pii] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Horinouchi M, Hayashi T, Koshino H, Kurita T, Kudo T. Identification of 9,17-dioxo-1,2,3,4,10,19-hexanorandrostan-5-oic acid, 4-hydroxy-2-oxohexanoic acid, and 2-hydroxyhexa-2,4-dienoic acid and related enzymes involved in testosterone degradation in Comamonas testosteroni TA441. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2005;71:5275–5281. doi: 10.1128/AEM.71.9.5275-5281.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Miclo A, Germain P. Hexahydroindanone derivatives of steroids formed by Rhodococcus equi. Applied microbiology and biotechnology. 1992;36:456–460. [Google Scholar]

- 46.van der Geize R, Grommen AW, Hessels GI, Jacobs AA, Dijkhuizen L. The steroid catabolic pathway of the intracellular pathogen Rhodococcus equi is important for pathogenesis and a target for vaccine development. PLoS Pathog. 2011;7:e1002181. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002181. PPATHOGENS-D-10-00358 [pii] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Sih CJ, Tai HH, Tsong YY. The mechanism of microbial conversion of cholesterol into 17-keto steroids. J Am Chem Soc. 1967;89:1957–1958. doi: 10.1021/ja00984a039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Sih CJ, Tai HH, Tsong YY, Lee SS, Coombe RG. Mechanisms of steroid oxidation by microorganisms. XIV. Pathway of cholesterol side-chain degradation. Biochemistry. 1968;7:808–818. doi: 10.1021/bi00842a039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Sih CJ, Wang KC, Tai HH. Mechanisms of steroid oxidation by microorganisms. XIII. C22 acid intermediates in degradation of cholesterol side chain. Biochemistry. 1968;7:796–807. doi: 10.1021/bi00842a038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Capyk JK, Kalscheuer R, Stewart GR, Liu J, Kwon H, Zhao R, Okamoto S, Jacobs WR, Jr, Eltis LD, Mohn WW. Mycobacterial cytochrome P450 125 (Cyp125) catalyzes the terminal hydroxylation of C27-steroids. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:35534–35542. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.072132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Ouellet H, Guan S, Johnston JB, Chow ED, Kells PM, Burlingame AL, Cox JS, Podust LM, de Montellano PR. Mycobacterium tuberculosis CYP125A1, a steroid C27 monooxygenase that detoxifies intracellularly generated cholest-4-en-3-one. Mol Microbiol. 2010;77:730–742. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2010.07243.x. doi: MMI7243 [pii] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Driscoll MD, McLean KJ, Levy C, Mast N, Pikuleva IA, Lafite P, Rigby SE, Leys D, Munro AW. Structural and biochemical characterization of Mycobacterium tuberculosis CYP142: evidence for multiple cholesterol 27-hydroxylase activities in a human pathogen. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:38270–38282. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.164293. doi: M110.164293 [pii] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Chang JC, Harik NS, Liao RP, Sherman DR. Identification of mycobacterial genes that alter growth and pathology in macrophages and in mice. J Infect Dis. 2007;196:788–795. doi: 10.1086/520089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Chang JC, Miner MD, Pandey AK, Gill WP, Harik NS, Sassetti CM, Sherman DR. igr Genes and Mycobacteriumtuberculosis cholesterol metabolism. J Bacteriol. 2009;191:5232–5239. doi: 10.1128/JB.00452-09. doi: JB.00452-09 [pii] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Thomas ST, VanderVen BC, Sherman DR, Russell DG, Sampson NS. Pathway profiling in Mycobacterium tuberculosis: elucidation of cholesterol-derived catabolite and enzymes that catalyze its metabolism. J Biol Chem. 2011;286:43668–43678. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.313643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Zhang J, Zhang W, Zou D, Chen G, Wan T, Zhang M, Cao X. Cloning and functional characterization of ACAD-9, a novel member of human acyl-CoA dehydrogenase family. Biochemical and biophysical research communications. 2002;297:1033–1042. doi: 10.1016/s0006-291x(02)02336-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Souri M, Aoyama T, Hoganson G, Hashimoto T. Very-long-chain acyl-CoA dehydrogenase subunit assembles to the dimer form on mitochondrial inner membrane. FEBS letters. 1998;426:187–190. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(98)00343-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.England K, Crew R, Slayden RA. Mycobacterium tuberculosis septum site determining protein, Ssd encoded by rv3660c, promotes filamentation and elicits an alternative metabolic and dormancy stress response. BMC microbiology. 2011;11:79. doi: 10.1186/1471-2180-11-79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Slayden RA, Knudson DL, Belisle JT. Identification of cell cycle regulators in Mycobacterium tuberculosis by inhibition of septum formation and global transcriptional analysis. Microbiology. 2006;152:1789–1797. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.28762-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]