Abstract

The tumor suppressor retinoblastoma protein (pRb) is inactivated in a wide variety of cancers. While its role during cell cycle is well characterized, little is known about its properties on apoptosis regulation and apoptosis-induced cell responses. pRb shorter forms that can modulate pRB apoptotic properties, resulting from cleavages at caspase specific sites are observed in several cellular contexts. A bioinformatics analysis showed that a putative caspase cleavage site (TELD) is found in the Drosophila homologue of pRb (RBF) at a position similar to the site generating the p76Rb form in mammals. Thus, we generated a punctual mutant form of RBF in which the aspartate of the TELD site is replaced by an alanine. This mutant form, RBFD253A, conserved the JNK-dependent pro-apoptotic properties of RBF but gained the ability of inducing overgrowth phenotypes in adult wings. We show that this overgrowth is a consequence of an abnormal proliferation in wing imaginal discs, which depends on the JNK pathway activation but not on wingless (wg) ectopic expression. These results show for the first time that the TELD site of RBF could be important to control the function of RBF in tissue homeostasis in vivo.

Introduction

The Retinoblastoma gene, Rb, was first identified as the tumor suppressor gene mutated in a rare childhood eye cancer, and its product (pRb) is often functionally inactivated in many human cancers by mutation or hyperphosphorylation [1], [2]. pRb is a member of the pocket protein family. These proteins possess specific A and B domains that form the pocket domain, required for their interactions with many transcription factors or co-factors in order to modulate the transcription of various genes (reviewed in [3], [4]). One of the major roles of pRb is to inhibit cell cycle progression by repressing the transcription of genes required for the G1-S transition, such as cyclin E or genes necessary for DNA synthesis, through binding and regulation of the E2F/DP transcription factors [5]. In addition, Rb has also been involved in chromosome dynamics during the M phase (rewieved in [6]).

Besides its roles on cell cycle, pRb regulates a variety of cellular processes, including angiogenesis, senescence, differentiation and apoptosis [7], [8]. In opposition to its well-established effects on cell cycle regulation, pRb role in apoptosis appears to be complex. Indeed, on the one hand pRb inactivation, partly by increasing free E2F1 DNA binding activity can induce cell cycle S phase entry and apoptosis, involving p53-dependent or –independent pathways [9], [10], which shows that pRb can be anti-apoptotic. On the other hand, several studies have shown that pRb can also be pro-apoptotic in several cellular contexts [11], [12], [13], [14], [15], [16], [17]. Although it has been shown that pRb localizes to mitochondria [18] where it induces apoptosis directly [19], little is known about the mechanisms that regulate pRb apoptotic functions. Many studies in mammals cells have shown that the pRb protein can be cleaved at several sites during apoptosis [20], [21], [22], [23], [24]. A cleavage at the C-terminus of pRb generates the p100Rb form [25], and a more internal cleavage generates two forms: p48Rb and p68Rb [26]. These cleavages are realized by specific caspases at consensus cleavage sites ending by an aspartate [25], [26]. In addition, we previously described another cleavage of pRb by caspase 9 at a LExD site, which generates the p76Rb form [13]. These cleavages are certainly part of a poorly understood regulation process of pRb functions. Indeed, pRb cleavage can often be observed when apoptosis is induced by different ways, and impairing pRb C-terminus cleavage reduces apoptosis [23], [27]. We have shown that p76Rb is pro-apoptotic in several human cell lines [28] but possesses anti-apoptotic properties in rat embryonic fibroblasts [13]. This discrepancy could be related to a differential regulation of apoptotic genes by pRb in human versus rodent cells [29]. Altogether, these results show that cleavage of pRb can exert specific activities on the control of apoptosis.

Drosophila is a powerful model for genetic studies, which can be used to better understand apoptosis regulation by pocket proteins, and modes of regulation of these proteins in vivo. Components of the E2F/pRb pathway are highly conserved and simpler in Drosophila than in mammals. In Drosophila, only one DP (dDP), two E2F proteins (dE2F1, dE2F2) and two pRb family proteins (RBF, RBF2) have been described [30], [31]. As in mammals, RBF binds to and inhibits the transcription factor dE2F1 [32], thus impairing its ability to induce transcription of genes whose products are necessary for cell cycle progression, like cyclin E [33]. In Drosophila, loss of function clones for RBF display an increased sensitivity to irradiation-induced apoptosis [34], [35], [36], and an increased level of apoptosis is observed in RBF−/− embryos [37]. According to these studies, RBF has an anti-apoptotic role in Drosophila. Despite this prevalent view, we have recently shown that RBF can also exert a pro-apoptotic effect in proliferating cells, in a caspase-dependent manner [38], which is more in acquaintance with its tumor-suppressor role. Thus, the complexity of pRb effects on apoptosis is conserved in Drosophila.

In this paper, we identified a TELD site in RBF sequence, which is most probably equivalent to the LExD site of mammalian pRb. In order to determine if RBF TELD site can modulate RBF properties on apoptosis, we generated a mutant form of RBF, RBFD253A, in which the aspartate of the cleavage site, which is necessary for caspase recognition, is switched into an alanine. We observed that RBFD253A expression remains pro-apoptotic in proliferating cells of the wing imaginal disc, the adult wing primordium, and that this process depends on the activation of JNK pathway. Interestingly, RBFD253A expression also induces ectopic proliferation and overgrowth in the wing tissue, which also depend on the JNK pathway but not on wg ectopic expression. This overgrowth was never observed when RBF was expressed. Therefore, mutating the TELD caspase cleavage site modulates the properties of RBF and affects tissue homeostasis. This result indicates that RBF cleavage by caspases in vivo could be important to control its effects on cell fate during development.

Materials and Methods

Fly stocks and breeding conditions

Flies were raised on standard medium. The UAS-RBF and vg-Gal4 strains were generous gifts from J. Silber. The en-Gal4, ptc-Gal4 and UAS-EGFP strains were generous gifts from L. Théodore. The C96-Gal4 strain was a generous gift from F. Agnes. The UAS-bsk-RNAi strain was a generous gift from S. Netter. The UAS-mtGFP, UAS-p35 and the hepr75 strains come from the Bloomington stock center, and the UAS-wg-RNAi strain comes from the Vienna Drosophila Resource Center. A Canton S w1118 line was used as the reference strain. All crosses using the Canton S w1118, UAS-RBF and UAS-RBFD253A(B18) strains were performed at 25°C and all crosses using the UAS-RBFD253A(B2.3) were performed at 21°C to induce production of similar protein levels. In these conditions both lines exhibit similar phenotypes.

Generation of transgenic flies

The rbf full-length cDNA was provided by N. Dyson. We generated the non-cleavable form of RBF by changing the aspartate 253 to an alanine. Mutagenesis was conducted with the Quikchange Site-Directed Mutagenesis kit (Stratagen#200518) by using sens RBFmut903 5′CTGGACGGAGCTGGCATTTCGTCACAATCCG3′ and antisens RBFmut903 5′CGGATTGTGACGAAATGCCAGCTCCGTCCAG3′ primers. The Not1/Kpn1 insert was then subcloned into the pUAST vector to produce the pUAST-RBFD253A vector and sequenced to verify its integrity. The pUAST-RBFD253A construct was injected into Canton S w1118 fly embryos following standard procedures to obtain transgenic Drosophila strains. Independent transgenic lines were characterized and used for further experiments.

TUNEL staining of imaginal discs

C96-Gal4, vg-Gal4 and ptc-Gal4 females were crossed with w1118, UAS-RBF, UAS-RBFD253A or UAS-bsk-RNAi males for apoptosis detection. Wing imaginal discs of the progeny were dissected in PBS pH 7.6, fixed in PBS/formaldehyde 3.7%, washed three times for 20 min in PBT (1X PBS, 0.5% Triton). Discs were then dissected, TUNEL staining was performed following manufacturer's instructions (ApopTag Red in situ apoptosis detection kit, Chemicon), and discs were mounted in CitifluorTM (Biovalley) and observed with a conventional Leica DMRHC research microscope using the N2.1 filter. For quantification experiments, discs were observed with a Leica SPE upright confocal microscope. White patches in the wing pouch were counted for at least 30 wing imaginal discs per genotype. Student's tests were performed and results were considered to be significant when α<5%.

Histochemistry

The following antibodies were used: anti-RBF (rabbit polyclonal anti-RBF, 1∶500, Custom antibody), anti-Wg (mouse monoclonal antibody, DSHB, clone number 4D4, 1∶100), anti-◯P-JNK (rabbit polyclonal antibody, 1∶500, Promega number V7931). Third instar larvae were dissected in PBS pH 7.6, fixed in PBS/3.7% formaldehyde, washed three times for 20 min each in PBT (1X PBS, 0.3% Triton) and incubated with the primary antibody overnight at 4°C in PBT/FCS (1X PBS, 0.3% Triton, 10% FCS). Incubation with the secondary antibody was carried in PBT/FCS for 2 hours at room temperature. Larvae were then washed thrice in PBT and placed in PBS/glycerol (1∶1) overnight at 4°C. Finally, discs were mounted in Citifluor™ (Biovalley) and observed with a conventional Leica DMRHC research microscope, using the L5 filter to detect green fluorescence, the N2.1 filter for the red fluorescence.

BrdU labeling of wing discs

ptc-GAL4 or en-GAL4 females were crossed with UAS-RBF and UAS-RBFD253A males, and with w1118 males for the control. Larvae were fed for 2 h on medium supplemented with 1 mg/ml BrdU. They were then dissected in 1X PBS pH 7.6, and fixed in PBT/formaldehyde (PBS 1X/5% formaldehyde/0.3% Triton X-100) for 20 min at room temperature, washed three times for 31min in PBT, denatured in 2.2 N HCl/0.1% Triton X-100 by two 15 minute-long incubations, neutralized with 100 mM sodium tetraborate (Borax) by two 5 minute-long incubations. For immunohistochemistry, larvae were blocked by incubation in PBT/10% fetal calf serum (FCS) for 45 min, incubated with mouse anti-BrdU monoclonal antibody (1: 200, DSHB) overnight at 4°C and washed thrice in PBT/FCS. Discs were then incubated with anti-mouse IgG-FITC (1: 200, Jackson Immuno Research) and washed thrice in PBT. Discs were mounted in Citifluor™ and observed with a Leica SP2 upright confocal microscope.

Results

Generation of RBFD253A, a mutant form of RBF affecting a consensus conserved caspase cleavage site

We have used the CASVM web server [39] to scan the full length RBF for potential caspase cleavage sites predicted by the support vector machines (SVM) algorithm [40]. This was done with the P14P10′ window (tetrapeptide cleavage sites with ten additional upstream and downstream flanking sequences) which has the highest accuracy. Using this window, only one caspase cleavage site was found in RBF (Figure S1A in File S1). This unique conserved cleavage site, TELD, fulfills the criteria of substrate specificity reported for Dronc, the Drosophila homologue of Caspase 9 [41], [42]. Furthermore, the TELD sequence is located in position 253 of RBF in the region containing the LExD site that leads to the generation of the p76Rb form in mammals [13] and a consensus caspase cleavage site, LEND, can also been found in the C. elegans homolog at the same position (Figure S1B in File S1). The conservation of a caspase cleavage site through evolution suggests a physiological role for RBF cleavage in this region including in Drosophila.

Using western blot analysis we were unable to consistently observe a band at the expected apparent molecular weight of the cleaved form. We explain this difficulty by the incapacity of the only available antibody to reveal cleaved forms. To by-pass this problem, vectors allowing the expression of C-terminal HA-tagged forms of RBF and RBFp76, the C-terminal part of RBF expected to result from a cleavage at the putative caspase site were transfected into S2 cells. Western blot experiments reveal the presence of cleaved forms of RBF (Figure S1C in File S1). One of these has the expected size of RBFp76. This result shows that RBF can be cleaved in the TELD region.

As caspases recognize specific motifs ending by an aspartate, we generated a mutant form of RBF, RBFD253A, in which aspartate 253 is switched into an alanine. This mutation should impair a cleavage of the RBF protein at the TELD site by caspases. This kind of approach was successfully conducted in mammals to generate a cleavage-resistant form of pRb at a C-terminus consensus cleavage site by caspases [25]. Indeed, the expression of the HA-tagged form of RBFD253A in S2 cells does not seem to generate the cleaved form (Figure S1C in File S1). In order to determine if the RBF consensus caspase cleavage site could have a physiological relevance in regulating RBF functions in vivo, we generated several independent transgenic fly strains carrying the RBFD253A mutant form under control of the UAS transcription regulating sequence.

Expression of RBF or RBFD253A induces different phenotypes

To determine if the mutation of the TELD site modifies RBF activity, we tested if expression of RBF and RBFD253A could result in different adult phenotypes. Since the random insertion locus of transgenes in Drosophila transgenic strains can induce different expression rates of a same transgene in independent transgenic strains, we have studied two independent RBFD253A transgenic strains. The phenotypes were similar for both transgenic lines (data not shown). To compare RBF and RBFD253A effects, we first verified by RT-qPCR and western blot that RBF mRNA level and full-length RBF protein rates were similar in RBF and RBFD253A transgenic strains (Figure S2 in File S1).

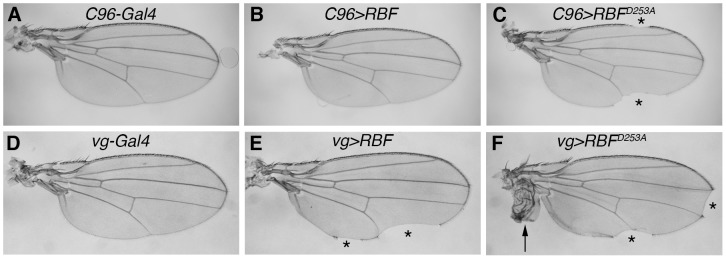

Since our previous results have shown that RBF expression is pro-apoptotic in cycling cells whereas it is not in post-mitotic cells [38], we used various wing specific drivers allowing an expression in cycling or non-cycling cells of the wing imaginal disc. In agreement with our previous results, we observed that RBF expression in non-cycling cells of the dorso-ventral boundary (ZNC) did not affect wing development, as adult C96>RBF wings showed wild type phenotype similar to C96-Gal4/+ control wings (Fig. 1, A, B). On the contrary, C96>RBFD253A wings presented notches at their margin (Fig. 1 C, asterisks) that resulted from tissue loss. Thus, the mutant and wild-type forms of RBF display different properties in non-cycling cells, which indicates that mutating the TELD site modifies RBF properties in these cells.

Figure 1. RBF and RBFD253A induce different phenotypes in adult wings.

Transgenes were expressed in non-proliferating cells of the ZNC during wing development (A–C) or proliferating cells along the dorso-ventral boundary (D–F). (A) C96-Gal4/+ control wings show a continuous wing margin. (B) C96-Gal4/UAS-RBF adult wings are similar to control wings. (C) In UAS-RBFD253A/+; C96-Gal4/+ flies, RBFD253A induces notches at the wing margin (asterisks). (D) vg-Gal4/+ control wings display a continuous wing margin. (E) In vg-Gal4/+; UAS-RBF/+ flies, RBF expression induces notches at the wing margin (asterisks). (F) In vg-Gal4/UAS-RBFD253A flies, RBFD253A expression provokes not only notches (asterisks) but also the apparition of hyperplastic tissue in the wing (arrow).

We have previously shown that RBF expression in cycling cells, under vg-Gal4 driver, generates notches in the wing margin, which result from RBF induced-apoptosis during third larval instar in the vg-Gal4 expression domain of the wing imaginal disc. To test the effects of RBFD253A expression in proliferating wing cells, we also used the vg-Gal4 driver. Expression of RBF under control of the vg-Gal4 driver led to notches at the wing margin (Fig. 1E, asterisks) and RBFD253A conserved this property (Fig. 1 F). Strikingly, using several independent transgenic strains, we also observed a phenotype of ectopic tissue next to the hinge of the wing, in up to 30% of the vg>RBFD253A flies (Fig. 1F, arrow). This phenotype is probably the consequence of abnormal cell proliferation and is specific of the RBFD253A form as it was never observed when wild type RBF was expressed at equivalent levels.

Finally, we tested the effects of ubiquitous expression of RBF and RBFD253A under control of the da-Gal4 driver. Such expression of RBF at 25°C induced notches on the wing margin (data not shown). Ubiquitous expression of RBFD253A was lethal when flies were raised at 25°C as well as at lower temperature (21°C) to reduce RBFD253A quantity. In contrast, RBF ubiquitous expression never revealed lethal, even at higher levels when flies were raised at 29°C.

Altogether, these results show that RBFD253A properties differ from RBF properties, both in cycling and non-cycling cells during development. Therefore, a cleavage of RBF at the TELD site may be important to regulate its functions in different cellular contexts.

RBFD253A induces more apoptosis than RBF in the wing imaginal disc

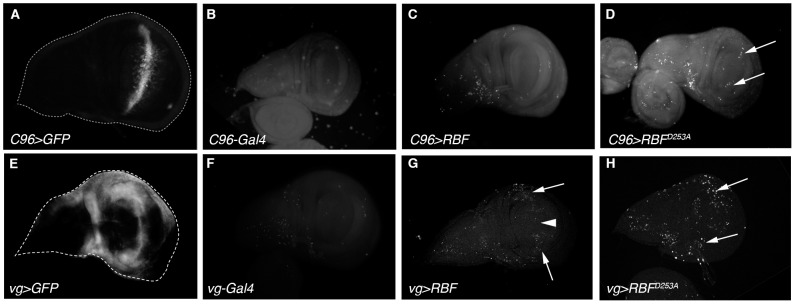

We have previously shown that RBF expression in proliferative cells induces apoptosis, including in the wing tissue. To check if RBFD253A-induced notch phenotype was also correlated with apoptosis induction, we performed TUNEL staining on larvae wing imaginal discs expressing UAS-RBF or UAS-RBFD253A under the control of C96-Gal4 or vg-Gal4 drivers (Fig. 2). The expression domains of these drivers were visualized in control wing discs by inducing UAS-mtGFP (Fig. 2A,E). In C96-Gal4 and vg-Gal4 control discs (Fig. 2B and F), developmental apoptosis was rare (few white bright dots). In C96>RBF wing discs (Fig 2 C), TUNEL staining was similar to control discs, which shows that RBF does not induce apoptosis in cells of the ZNC, in acquaintance with the absence of notches in C96>RBF adult wings (Fig 1 B). On the contrary, in C96>RBFD253A wing discs, some cells located at the center of the pouch in the zone corresponding to the ZNC were TUNEL labeled (Fig 2 D, arrows). Similar results were observed using Acridine Orange (AO) staining (Figure S3 in File S1) indicating that RBFD253A expression induces apoptosis in this region, leading to the appearance of notches in adult wings (Fig 1 C). In vg>RBF and vg>RBFD253A wing discs, apoptotic cells were observed within the driver expression domains (Fig. 2 G, H white arrows). Interestingly, RBF did not induce apoptosis at the center of the pouch in vg>RBF discs (Fig 2 G, arrow head) whereas RBFD253A is pro-apoptotic in this area that includes the ZNC. These observations are coherent with the fact that, contrarily to RBF, RBFD253A is pro-apoptotic in non-proliferating cells as observed with the C96-Gal4 driver.

Figure 2. RBFD253A is pro-apoptotic in the ZNC and induces more apoptosis than RBF in third instar larvae wing imaginal discs.

(A, E) C96-Gal4 and vg-Gal4 expression patterns are visualized by UAS-mtGFP expression in third instar larvae wing imaginal discs. (B-D, F-H) Apoptotic cells are labeled by TUNEL in wing imaginal discs; specific staining of apoptotic cells corresponds to bright white patches. (B, F) C96-Gal4/+ and vg-Gal4/+ control discs have few apoptotic cells. (C) C96-Gal4/UAS-RBF wing discs are similar to control. (D) Some apoptotic cells are observed within the C96-Gal4 expression domain in UAS-RBFD253A/X; C96-Gal4/+ discs (white arrow). (G, H) Apoptotic cells are observed within the vg-Gal4 expression domain in vg-Gal4/+; UAS-RBF/+ and UAS-RBFD253A/X; vg-Gal4/+ wing discs (white arrows). (G) The white arrowhead indicates a zone at the center of the pouch where cells are not TUNEL-labeled in vg-Gal4/+; UAS-RBF/+ wing discs. All discs are shown with posterior to the top.

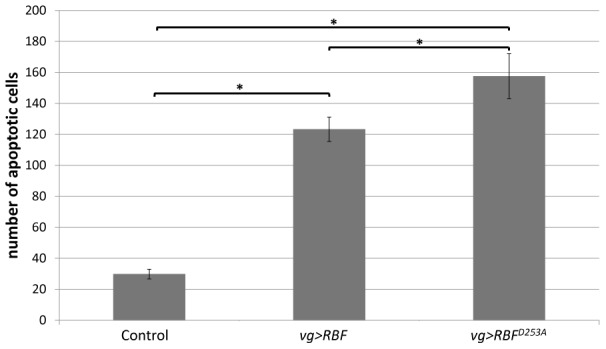

We also tested the effects of RBF and RBFD253A expression in cycling cells in a different and more restricted expression domain. Using ptc-Gal4 we drove RBF and RBFD253A expression at the antero-posterior boundary of the wing imaginal disc. Similar experiments on ptc>RBF and ptc>RBFD253A wing discs also showed that RBF and RBFD253A expression was associated with apoptosis (Figure S4 in File S1), confirming that both forms are pro-apoptotic in proliferating cells. In these experiments using vg-Gal4 and ptc-Gal4 to drive the expression of both RBF forms, it seemed that more cells were apoptotic in RBFD253A -expressing discs. To test if RBFD253A induced significantly more apoptosis than RBF, we have quantified TUNEL staining of vg>RBF or vg>RBFD253A wing imaginal discs. Staining patches in the wing pouch were counted for at least 30 imaginal discs per genotype (Fig 3). We observed that RBFD253A induced significantly more apoptosis than RBF (α<5%).

Figure 3. RBFD253A is more pro-apoptotic than RBF in third instar larvae wing imaginal discs.

Apoptotic cells were visualized by TUNEL staining of wing imaginal discs of vg-Gal4/+; UAS-RBF/+ or vg-Gal4/UAS-RBFD253A genotypes. TUNEL positive cells in the wing pouch were quantified. Asterisks indicate a statistically significant difference between two genotypes (Student's test, p<0,05).

RBFD253A induces increased proliferation of neighboring cells

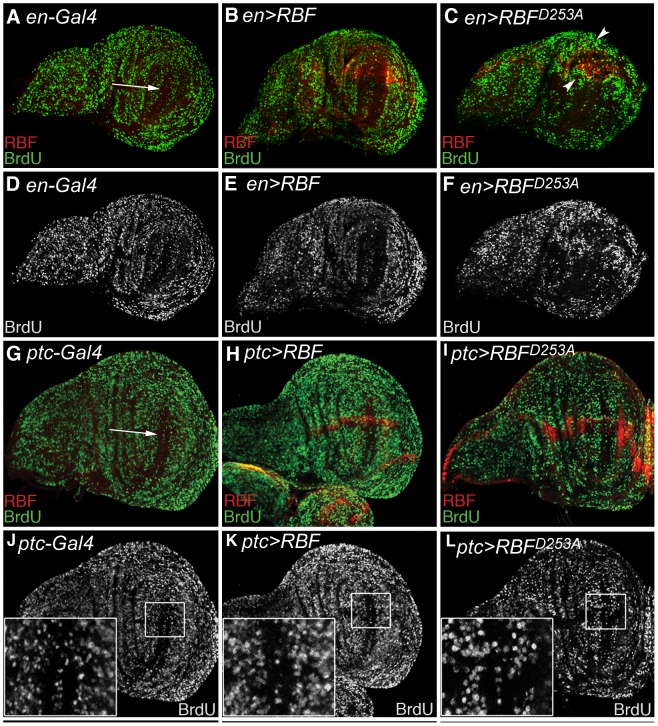

In order to check if the overgrowth observed in wings of RBFD253A expressing flies was due to an enhanced proliferation, we performed a BrdU incorporation assay to label cells in the S phase of the cell cycle in wing imaginal discs. As this tissue is highly proliferative, BrdU incorporation occurred throughout the whole disc. Only a small population of cells is arrested in the cell cycle and forms the ZNC, which is situated at the center of the wing pouch (Fig. 4A,G, white arrows). We used the en-Gal4 driver to express RBF forms in the posterior part of the discs, allowing the use of the anterior compartment as an internal control. Over-expression of RBF and RBFD253A was visualized by RBF staining (red) (Fig. 4B, C). The BrdU incorporation profile was similar in both RBF-expressing and control discs (Fig. 4A,B and D,E). On the contrary, a more intense BrdU staining was observed in the most posterior part of discs expressing RBFD253A, but also in cells located near the antero-posterior border, a region that did not express RBFD253A in these discs (Fig. 4C, see arrowheads). Therefore, RBFD253A expression specifically induces abnormal proliferation of cells in a non-autonomous way.

Figure 4. RBFD253A expression induces proliferation of neighboring cells.

(A–F) From left to right, phenotypes of the larvae are: en-Gal4/+, en-Gal4/+; UAS-RBF/+ and UAS-RBFD253AX; en-Gal4/+. (A–C) S phase staining by BrdU (green), and RBF immuno-staining (red). (D–F) BrdU staining (white) of the discs shown in (A–C). (B, E) In RBF expressing discs, as in the control disc shown in (A,D), BrdU staining is homogeneous in the whole disc, except in the ZNC (Zone of Non-proliferating Cells) (white arrow). (C–F) In RBFD253A expressing discs, cells surrounding the strong RBF staining exhibit an enhanced BrdU staining, indicating that these cells have an increased proliferation rate. (G–L) From left to right, genotypes of the larvae are: ptc-Gal4/+, ptc-Gal4/UAS-RBF, and UAS-RBFD253A X; ptc-Gal4/+. (G–I) S phase staining by BrdU (green), and RBF staining (red). (J–L) BrdU staining (white) of the discs shown in (G–I) with enlarged view of boxed area. (G, J) BrdU staining is homogeneous in the whole disc, except in the ZNC (white arrow). (I–L) In ptc>RBFD253A discs, cells within the ZNC that are adjacent to RBFD253A expressing cells are labeled with BrdU, indicating an abnormal proliferation of these cells. All discs are shown with posterior to the top.

As en-Gal4 is expressed throughout the whole posterior part of the discs, we used the ptc-Gal4 driver to reduce possible alterations of the disc morphology when RBFD253A is expressed. In ptc>RBFD253A discs, RBFD253A is expressed along the antero-posterior boundary that crosses the ZNC at its center. Non-cycling cells of the ZNC do not incorporate BrdU, thus abnormal BrdU staining in these cells is easy to detect. In ptc>RBF wing discs, BrdU staining was similar to control discs (Fig. 4G,H). None of the cells of the ZNC, whether they expressed RBF or not, displayed abnormal staining (Fig. 4J,K boxed areas showing the intersection of the ZNC with the antero-posterior boundary). On the contrary, in ptc>RBFD253A discs, we observed BrdU-labeled cells within the ZNC in the posterior side. This abnormal proliferation was adjacent to RBFD253A-expressing cells (Fig. 4 I,L boxed area). We observed that these cells localized in the posterior compartment along the antero-posterior boundary expressed ectopically the dorso-ventral boundary marker wg, and thus normally belong to the ZNC (Figure S5 in File S1). Therefore, these observations suggest that cells of the ZNC that do not express RBFD253A are induced to proliferate when this mutant form is expressed along the antero-posterior border of the disc. These results confirm that RBFD253A expression is able to induce abnormal proliferation of neighboring cells, even in a domain in which cells are normally arrested in the G1 phase of the cell cycle.

It is well established that cells undergoing apoptosis in a growing tissue promote proliferation of surrounding healthy cells [43], maintaining tissue homeostasis by a process named apoptosis-induced proliferation [44], [45]. We have observed that both RBF and RBFD253A could induce apoptosis in proliferating cells and that RBFD253A induced more apoptosis than RBF when expressed at a similar rate. As RBFD253A enhanced the proliferation rate of cells adjacent to its expression domains and subsequent wing tissue overgrowth, we wondered if the apparition of ectopic tissue in the wing was a specific effect of RBFD253A expression, and not only a consequence of an increased apoptosis induced by this mutant form. For this reason, we tested if enhancing RBF-induced apoptosis could result in tissue overgrowth. As the UAS/Gal4 system efficiency depends on temperature, we increased the breeding temperature of vg>RBF flies from 25°C to 29°C to enhance RBF expression. We also elevated the dose of UAS-RBF by expressing two independent p[UAS-RBF] transgene insertions in the same flies. Under these conditions, the strength of the notch phenotype and the level of AO staining in wing discs were increased to the same level as what was observed with the RBFD253A construct, but we never observed ectopic tissue in the wings (data not shown). Thus, the effect of RBFD253A on proliferation is specific of this mutant form, which reinforces the view that RBF cleavage could be necessary to control its activities in vivo. It suggests that RBFD253A amplifies an apoptosis-induced proliferation mechanism, leading to an excessive proliferation in response to apoptosis.

Activity of the JNK pathway is necessary for RBF- and RBFD253A-induced apoptosis and for RBFD253A-induced overgrowth

The JNK pathway is implicated in both apoptotic and proliferation processes (reviewed in [46]). Among these processes, compensatory proliferation allows injured tissues to recover their original size by inducing ectopic proliferation of surviving cells. Moreover, in models involving cells induced to die by apoptosis but kept alive by the caspase inhibitor p35, the so-called “undead cells” emit persistent mitogen signaling that promotes overgrowth under control of the JNK pathway [43]. We thus tested if the JNK pathway was required for RBF- and RBFD253A-induced apoptosis and for RBFD253A-induced ectopic proliferation. The active form of the Drosophila JNK Bsk was stained with an anti-◯P-JNK antibody in ptc>RBF and ptc>RBFD253A wing discs. In ptc-Gal4/+ control discs, we did not detect any specific staining in the ptc domain, which indicates that the JNK pathway is not activated in this domain during normal development (Fig. 5 A). On the contrary, in ptc>RBF and ptc>RBFD253A discs, we observed JNK activation in the ptc-Gal4 expression domain, i.e. at the antero-posterior border of the discs (Fig. 5 B, C). This activation was strong in young third instar larvae, and decreased when larvae got older (data not shown).

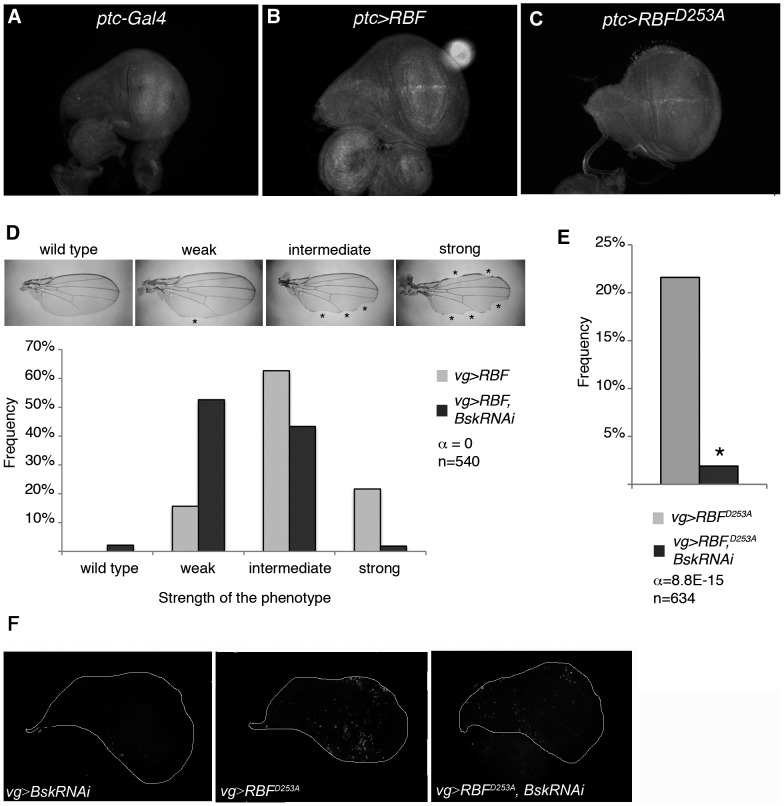

Figure 5. RBF- and RBFD253A-induced apoptosis as well as RBFD253A-induced overgrowth depend on the JNK pathway activity.

(A–C) Anti-◯P-JNK staining in young third instar larvae wing imaginal discs. (A) No staining is observed in ptc-Gal4/+ control. (B, C) UAS-RBF/ptc-Gal4 and UAS-RBFD253A/X; ptc-Gal4/+ discs present anti-◯P-JNK staining at the dorso-ventral boundary. All discs are shown with posterior to the top. (D) Notch phenotypes in adult wings of vg-Gal4/+; UAS-RBF and vg-Gal4/+; UAS-RBF/UAS-bsk-RNAi flies are grouped into four categories (wild type, weak, intermediate and strong) according to the number and size of notches observed on the wing margin (asterisks). Bsk-RNAi partially suppresses RBF-induced notch phenotypes (Wilcoxon test, α<10−15, n = 540). (E) The frequency of RBFD253A-induced ectopic tissue growth is strongly decreased in UAS-bsk-RNAi co-expressing flies (Chi2 test, α = 8.8 10−15). (F) TUNEL-labeling of apoptotic cells in wing imaginal discs; specific staining of apoptotic cells corresponds to bright patches in wing discs of vg-Gal4/+; UAS-bsk-RNAi/+ (left panel), vg-Gal4/+; UAS-RBFD253A/+ (center panel), vg-Gal4/+; UAS-RBFD253A/UAS-bsk-RNAi (right panel) larvae. RNAi-mediated knockdown of bsk strongly decreased RBFD253A-induced apoptosis. All discs are shown with posterior to the top.

To test if the JNK pathway was required for RBF-dependent apoptosis, we used a p[UAS-bsk-RNAi] transgene to disrupt the JNK pathway. Under vg-Gal4, the number and size of notches present at the wing margin is correlated with the amount of apoptosis [38]. We classified the wing phenotypes into four categories (wild type, weak, intermediate and strong) according to the number and size of notches (Fig. 5D, asterisks). In a control experiment, we verified that wings were wild type in vg>bsk-RNAi flies (data not shown). We assayed for the strength of the notch phenotype in wings of vg>RBF flies in presence or absence of UAS-bsk-RNAi (Fig. 5D). When bsk-RNAi was co-expressed with RBF, distribution of the phenotypes significantly shifted toward weaker phenotypes when compared to the expression of RBF alone (Wilcoxon test, α<10−15, n = 540) (Fig. 5D). We also disrupted the JNK pathway by using the hepr75 mutant and observed that distribution of the RBF-induced notch phenotype was weaker in the hepr75 mutant background (data not shown). These results clearly show that the JNK pathway is involved in RBF-induced apoptosis.

We also tested if the JNK pathway activation was required for RBFD253A-induced apoptosis and ectopic tissue. We counted the number of vg>RBFD253A flies presenting ectopic tissue in the wing in the presence or absence of UAS-bsk-RNAi and observed a strong decrease of their frequency: from 22.1% of vg>RBFD253A flies to only 1.9% of vg>RBFD253A, bsk-RNAi flies displaying overgrowth (Chi2 test, α = 8.8E-15) (Fig. 5E). We obtained similar results with vg>RBFD253A flies in a hepr75 heterozygous background (data not shown). In parallel, we performed TUNEL staining in vg>RBFD253A wing imaginal discs in the presence or absence of UAS-bsk-RNAi (Fig. 5F), and detected less apoptotic cells when bsk-RNAi was co-expressed. Thus, similarly to RBF, RBFD253A-induced apoptosis depends on the activity of the JNK pathway.

In conclusion, we demonstrated that RBF and RBFD253A activate the JNK pathway, that this pathway mediates both RBF and RBFD253A -induced apoptosis, and is responsible for RBFD253A-induced overgrowth.

RBFD253A-induced overgrowth does not depend on wg ectopic expression

As previously indicated, the JNK pathway is essential to both RBFD253A-induced overgrowth, and over-proliferation induced by “undead cells”. Its over-activation in “undead cells” leads to ectopic synthesis and secretion of the mitogenic proteins Wg and Dpp in a long lasting manner, leading to an over-proliferation of neighboring cells and overgrowth phenotypes [43]. Since RBFD253A-induced overgrowth depends on JNK pathway activation, we wondered if this process was provoked by a similar mechanism. We thus co-expressed RBF and p35 in wing discs to generate undead cells depending on RBF-induced apoptosis, and compare the wg expression pattern in these discs to wg expression in RBFD253A expressing discs. In vg>RBF, p35 flies raised at 25°C, only one wing observed displayed overgrowth out of 123 flies counted. Therefore, even in the presence of p35, RBF does not seem to induce an overgrowth phenotype that would result from the presence of undead cells. However, at 29°C, more wings co-expressing RBF and p35 presented overgrowth phenotype (10 wings out of 35), but in such extreme conditions only few flies hatched. We tested if the Wg pattern was altered in these conditions as it has been observed in the presence of “undead cells”. We used the en-Gal4 driver and compared the Wg staining in the control anterior compartment and in the posterior compartment that expresses RBF. en>RBF wing discs displayed a wild type Wg pattern similar to what was observed in en-Gal/+ control discs (data not shown). In en>RBF, p35 wing discs, the Wg pattern in the posterior compartment is altered when compared to control en>p35 disc (Figure S6 panel D,E in File S1). Ectopic patches were observed outside the normal wg expression domain (Figure S6 panel E, white arrows in File S1) as was reported in studies of undead cells-induced overgrowth [47]. In en>RBFD253A discs, the wg expression pattern is also altered, but is different from what is observed in en>RBF, p35 discs. We did not observe any ectopic Wg patch in en>RBFD253A wing discs, but an enlargement of the Wg pattern in the posterior part of the disc (Figure S6 panel F in File S1). Thus, the wg expression pattern in en>RBF, p35 and in en>RBFD253A wing discs is clearly different.

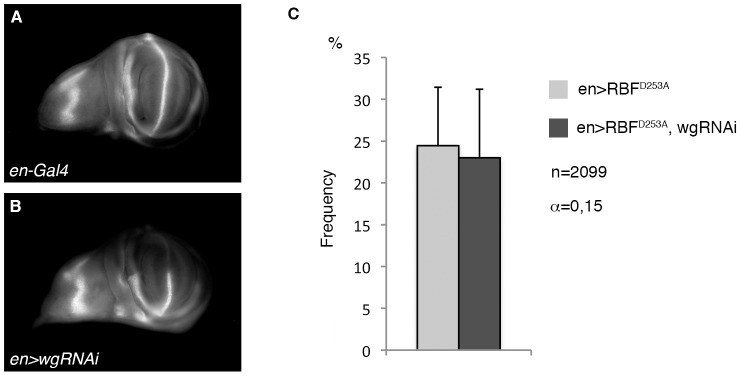

We also tested if Wg was required for RBFD253A-induced overgrowth by using a UAS-wg-RNAi construct. In en>wg-RNAi wing discs, the Wg staining observed after immuno-detection was strongly decreased in the posterior compartment, indicating that this wg-RNAi construct efficiently abolished wg translation (Fig. 6 A, B). We did not observe any significant difference in the frequency of overgrowth phenotype between vg>RBFD253A and vg>RBFD253A, wg-RNAi flies (Fig. 6 C). Taken together, these results show that co-expression of RBF and p35 induces hyperplastic proliferation and wg ectopic expression as described previously for other pro-apoptotic genes in undead cells. In a distinct manner, RBFD253A expression seems to induce overgrowth that would implicate the JNK pathway but not wg ectopic expression. These results suggest that a mutation of the TELD sequence of RBF deregulates apoptosis-induced proliferation, in a JNK-dependent and Wg-independent way.

Figure 6. RBFD253A-induced overgrowth does not depend on Wg.

(A, B) Anti-Wg staining in wing imaginal discs of control (A) or en-Gal4, UAS-wg-RNAi third instar larvae (B). No staining is observed in the posterior compartment of discs that express wg-RNAi. (C) The frequency of RBFD253A-induced ectopic tissue growth is not affected in UAS-wg-RNAi co-expressing flies (Chi2 test, α = 0.15). All discs are shown with posterior to the top.

Discussion

In this study, we have generated transgenic Drosophila strains expressing a RBFD253A mutant form under control of the UAS/Gal4 system. We observed that this form has an increased pro-apoptotic activity compared to RBF and induces abnormal non-cell autonomous proliferation. This different effect of RBFD253A cannot be explained by a modulation in level of the full-length RBF protein. In the wing imaginal disc, RBFD253A, but not RBF, induces apoptosis in non-proliferative cells of the ZNC. One can hypothesize that RBFD253A is more stable than RBF, and that an increased level of full-length protein in these cells is pro-apoptotic. In this model, excessive wild type RBF would be cleaved in cells of the ZNC in order to maintain a physiological level of this form, preventing an apoptotic effect of accumulated full-length protein. However, we have controlled by western blot that levels of RBF higher than RBFD253A levels do not induce apoptosis in cells of the ZNC (data not shown) which rules out this hypothesis. Moreover, RBFD253A ubiquitous expression is lethal whereas it is not the case even for higher levels of wild-type RBF. Therefore, these results suggest that the mutant form displays specific properties.

Mutation of the TELD site could modify the interactions between RBF and some of its partners and thus modulate its activity. This site is located in the N-terminal domain of the protein. The crystal structure of the Rb N-terminal domain (RbN) has revealed a globular entity formed by two rigidly connected cyclin-like folds [48]. By analogy, we can assume that the TELD sequence of RBF is located in a proteolytically labile linker important for its conformation and its binding to partners.

Furthermore, the effect of RBFD253A on proliferative tissue differs from that of RBF, as it can induce abnormal non-cell autonomous proliferation. We observed that vg>RBFD253A adult wings present an overgrowth phenotype that was never observed when RBF was expressed, even at high levels. This overgrowth was correlated to some excessive proliferation induced in wing imaginal discs by RBFD253A expression.

We hypothesize that the lethality associated with RBFD253A ubiquitous expression could be a consequence of this excessive proliferation. Altogether, our results show that the TELD site is important for RBF properties, in the control of both apoptosis and apoptosis-induced proliferation.

Our results suggest that the mechanism involved in the RBFD253A-induced overgrowth phenotype depends on the JNK pathway as inhibition of this pathway by expressing bsk-RNAi or in a hepr75 heterozygous mutant background abrogated almost completely RBFD253A-induced overgrowth. Nevertheless, a simple activation of the JNK pathway in the RBFD253A-induced overgrowth phenotype is not sufficient to explain the different effects of RBF and RBFD253A on proliferation, as RBF is also able to induce JNK activation but without any overgrowth phenotype. The JNK pathway is involved in both RBF- and RBFD253A-induced apoptosis, thus we cannot exclude that the inhibition of RBFD253A-induced overgrowth phenotype is a consequence of the decrease of apoptosis in bsk-RNAi expressing and hepr75 contexts. Indeed, RBFD253A-induced overgrowth phenotype could result from a misregulation of an apoptosis-induced proliferation process. But this cellular process, by which apoptotic cells promote proliferation of surrounding living cells, also depends on the JNK pathway. Similarly in the literature, “undead cells”, which are kept alive by the caspase inhibitor p35 after induction of apoptosis by a pro-apoptotic gene, induce non-cell autonomous proliferation by a persistent activation of the JNK pathway [43], [47], [49], [50], [51]. Since the JNK pathway is essential for RBFD253A-induced overgrowth, it is possible that this cleavage-resistant form of RBF possesses an increased ability to activate the JNK in a manner that could enhance the JNK non-apoptotic functions.

Further investigation will be necessary to clarify the consequences of the JNK pathway activation by RBF and RBFD253A, and why this activation could lead to different phenotypes. One could also hypothesize that RBF and RBFD253A do not activate the JNK pathway through the same upstream components, which could lead to different effects.

We showed that contrarily to what is observed in the presence of undead cells, RBFD253A-induced overgrowth does not require Wg activity. In undead cells, the JNK pathway activation has been shown to lead to ectopic wg expression that is responsible for the observed overgrowth [43], [47], [49], [52]. Moreover, the secretion of Wg is not limited to undead cells, but also occurs in “genuine” apoptotic cells [53]. We hypothesized that RBFD253A-induced overgrowth could result from a misregulation of apoptosis-induced cell proliferation through Wg signaling. We rejected this hypothesis since the inhibition of wg expression with a wg-RNAi construct, that in our experiment completely abrogates the detection of wg protein, did not reduce overgrowth. Furthermore, the wg expression pattern in en>RBFD253A wing discs was different form the pattern observed in en>RBF, p35 discs that contained undead cells and displayed typical ectopic patches of wg-expressing cells. In en>RBFD253A and ptc>RBFD253A wing discs, more cells seemed to express wg, leading to an enlargement or a deformation of the pattern, but we did not observe ectopic patches of wg expression. This enlargement could be due to proliferation of wg-expressing cells in response to RBFD253A expression, rather than being a cause of this proliferation as it is reported in the presence of undead cells. These results show that RBFD253A is able to induce ectopic proliferation in a JNK-dependent manner that does not require wg ectopic expression and that is therefore different from the characterized mechanism induced by the presence of undead cells in a tissue.

Altogether, our data show that RBFD253A expression misregulates tissue homeostasis by inducing hyper-proliferation and overgrowth, in a Wg-independent manner. It has been shown that regulation of tissue homeostasis by compensatory proliferation or proliferation in response to massive damage during development does not require wg expression [43], [54]. One could hypothesize that RBFD253A-associated overgrowth phenotype could be the reflection of a misregulation of the compensatory proliferation mechanism by strongly enhancing proliferation of neighboring cells. Thus, the identification of RBFD253A partners could provide a new opportunity to discover regulators of compensatory proliferation, which molecular mechanisms have not yet been elucidated. Besides, understanding how RBFD253A can lead to overgrowth could be of great interest to better characterize the tumor suppressor effect of the pocket protein family members.

Supporting Information

Figure S1 in File S1. RBF contains a consensus site of caspase cleavage. (A) RBF sequence was scanned for potential caspase cleavage site(s) using the CASVM web server (http://www.casbase.org/). This was done with the P14P10′ window (tetrapeptide cleavage sites with ten additional upstream and downstream flanking sequences) which have the highest accuracy. Only one predicted caspase cleavage site was found in RBF: TELD-253. (B) Amino acid sequences alignment of retinoblastoma protein homologs. Amino acid sequences of proteins from H. sapiens (top), C. elegans (middle), D. melanogaster (bottom) were aligned using the Clustal Omega program. Dashes represent gaps in the sequence. Amino acid sequences shown in boxes correspond to consensus caspase cleavage sites. (C) RBF and RBF cleaved forms analysed by Western Blot. Proteins extracts are made from S2 cells transfected with pActine Gal4 vector or pUAS RBFp76-HA (RBFp76-HA), pUAS RBF-HA (RBF-HA) or pUAS RBFD253A-HA (RBFD253A-HA) (Effecten kit, Quiagen). 2.106 cells were cryolysed in PBS pH 7.6 and homogenized in buffer containing 50 mM Tris-Cl pH = 7,4, 150 mM NaCl, 1% NP40, 1 mM DTT, AEBSFSC. Proteins were separated in 4–12% Bis-Tris polyacrylamide gels according to the manufacturer's instructions (BioRad) and transferred onto PVDF membrane (Millipore). Blots were incubated with mouse anti-HA (HA.11, Covance) and rabbit polyclonal anti-Actin (1∶500, Sigma). Arrow shows wholes RBF forms and dotted-line arrow shows RBFp76. Figure S2 in File S1. Quantification of RBF and RBFD253A protein rates and rbf mRNA. (A) RBF and RBFD253A protein rates detected by Western blot analysis. Protein extracts were prepared from embryos carrying the da-Gal4 driver to induce UAS-RBF and UAS-RBFD253A expressions ubiquitously. Three genotypes were tested: da-Gal4/+ (control), da-Gal4/UAS-RBF, UAS-RBFD253A/+; da-Gal4/+ at 25°C. Actin was used as a loading control, and an RBF antibody was used to detect RBF and RBFD253A (rabbit polyclonal anti-RBF,1∶500, Custom antibody, Proteogenix and rabbit polyclonal anti-Actin, 1∶500, Sigma). Immunoreactive bands were detected by Immobilon™ Western Chemiluminescent HRP Substrate (Millipore) with facilities of ChemiDoc MP System (BioRad). (B) Immunoreactive bands were quantified using the Quantity One software. Under these conditions, the level of RBF protein is significantly higher in embryos expressing UAS-RBF and UAS-RBFD253A than in control embryos (asterisk, ANOVA, p = 7.6E-3); furthermore, there is no significant difference between RBF and RBFD253A protein expression levels (ANOVA, p = 0.48). (C) Quantification of rbf mRNA by RT-qPCR in wing imaginal discs. Fifty wing imaginal discs per genotype were dissected on ice. Total RNAs were extracted from each sample using the RNeasy Mini kit (QIAGEN), RT was performed on each sample using random primer oligonucleotides (Invitrogen) with Recombinant Taq DNA Polymerase (Invitrogen). Real-time PCR analysis was performed using the C1000 Touch™ Thermal cycler (Biorad). Data are normalized against rp49 and correspond to the mean of three independent experiments. Error bars are the S.E.M. Asterisks indicate statistical significant difference between two genotypes (Student test, p<0,05). Figure S3 in File S1. RBFD253A is pro-apoptotic in the ZNC and induces more apoptosis than RBF in third instar larvae wing imaginal discs. (A, E) C96-Gal4 and vg-Gal4 expression patterns are visualized by UAS-mtGFP expression in third instar larvae wing imaginal discs. (B–D, F–H) Apoptotic cells are labeled with Acridine Orange in wing imaginal discs (2 min in 100 ng/ml AO, Molecular Probes); specific staining of apoptotic cells corresponds to bright white patches. (B, F) C96-Gal4/+ and vg-Gal4/+ control discs have few apoptotic cells. (C) C96-Gal4/UAS-RBF wing discs are similar to control. (D) Some apoptotic cells are observed within the C96-Gal4 expression domain in UAS-RBFD253A/X; C96-Gal4/+ discs (white arrows). (G, H) Apoptotic cells are observed within the vg-Gal4 expression domain in vg-Gal4/+; UAS-RBF/+ and UAS-RBFD253A/X; vg-Gal4/+ wing discs (white arrows). (G) The white arrowhead indicates a zone at the center of the pouch where cells are not AO-labeled in vg-Gal4/+; UAS-RBF/+ wing discs. All discs are shown with posterior to the top. Discs were mounted in AO and observed with a conventional Leica DMRHC research microscope using the L5 filter to detect AO fluorescence. Figure S4 in File S1. RBFD253A expression at the antero-posterior boundary of wing imaginal discs induces more apoptosis than RBF, but adult phenotypes are similar. (A–C) Distances between veins 3 and 4 (dv3-v4) were measured at the posterior third of the wings using the Adobe Photoshop CS3 software, as indicated by the black lines. 20 wings were measured to estimate the average distance between veins 3 and 4 (dv3-v4±s.e.m) for each genotype: (A) ptc-Gal4/+ control wings, (B) ptc-Gal4/UAS-RBF flies, (C) UAS-RBFD253A; ptc-Gal4 flies. UAS-RBF as well as UAS-RBFD253A expression under the control of ptc-Gal4 brings veins 3 and 4 closer. (D) ptc-Gal4 expression pattern is visualized by UAS-mtGFP expression in third instar larvae wing imaginal discs. Apoptotic cells are labeled with TUNEL (E–G) or Acridine Orange (H–J) in the wing imaginal discs; specific staining of apoptotic cells corresponds to bright white patches. (E, H) Few apoptotic cells are observed in ptc-Gal4/+ control discs. (F, G, I, J) In ptc-Gal4/UAS-RBF and UAS-RBFD253A/+; ptc-Gal4/+ discs, apoptotic cells are observed within the ptc-Gal4 expression domain (white arrows). More apoptotic cells are observed in UAS-RBFD253A/+; ptc-Gal4/+ discs. All discs are shown posterior to the top. Discs were observed with a conventional Leica DMRHC research microscope using the L5 filter to detect AO fluorescence and using the N2.1 filter to detect TUNEL. Figure S5 in File S1. RBFD253A expression at the antero-posterior boundary of wing discs alters the Wg pattern. (A–C) anti-Wg (green) and anti-RBF (red) staining with enlarged views of boxed areas. (A) Wg pattern in control ptc-Gal4/+ wing disc. (B) ptc-Gal4/UAS-RBF discs have the same Wg pattern than control discs. (C) In UAS-RBFD253A/X; ptc-Gal4/+ discs, the Wg pattern is altered (white arrowhead) when compared to control discs. More wg expressing cells adjacent to the RBFD253A expression domain in the posterior compartment are observed. All discs are shown with posterior to the top. Discs were observed with a conventional Leica DMRHC research microscope using the L5 filter to detect Wg-associated fluorescence and using the N2.1 filter to detect RBF-associated fluorescence. Figure S6 in File S1. Expression of RBFD253A and co-expression of RBF and p35 lead to different Wg patterns. (A–C) RBF immuno-staining (red). (D–F) anti-Wg immuno-staining (green). (D) Control Wg pattern in UAS-p35/X; en-Gal4/+ wing disc. (E) In UAS-p35/X; en-Gal4/+; UAS-RBF/+ wing discs, the Wg pattern is altered when compared to control discs: ectopic patches are observed in the posterior compartment (arrows and box b). (F) In UAS-RBFD253A/X; en-Gal4/+ wing discs, the Wg pattern is altered when compared to the control, and an enlargement of this pattern is observed in the posterior compartment (box a). All discs are shown with posterior to the top. Discs were observed with a conventional Leica DMRHC research microscope using the L5 filter to detect Wg and the N2.1 filter to detect RBF associated fluorescence.

(ZIP)

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to S. Gaumer and V. Rincheval for their critical reading of the manuscript. We wish to thank M.N. Soler, for expert support with confocal microscopy and N. Boggetto for expert support with flow cytometry. The Imaging and Cell Biology facility of the IFR87 (FR-W2251) “La plante et son environnement” is supported by Action de Soutien à la Technologie et la Recherche en Essonne, Conseil de l'Essonne. The flow cytometry facility of the Jacques Monod Institute is supported by the Ligue Nationale contre le Cancer (Comité Ile de France) (#R03/75-79).

Funding Statement

This work was supported by the Université de Versailles Saint-Quentin-en-Yvelines and by grants from the Association pour la Recherche contre le Cancer and the Ligue Nationale Contre le Cancer. Cécile Milet held successive fellowships from the Ministère de l'Education Nationale, de l'Enseignement Supérieur et de la Recherche and the Ecole Pratique des Hautes Etudes. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

References

- 1. Lee WH, Bookstein R, Hong F, Young LJ, Shew JY, et al. (1987) Human retinoblastoma susceptibility gene: cloning, identification, and sequence. Science 235: 1394–1399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Classon M, Harlow E (2002) The retinoblastoma tumour suppressor in development and cancer. Nat Rev Cancer 2: 910–917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Morris EJ, Dyson NJ (2001) Retinoblastoma protein partners. Adv Cancer Res 82: 1–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Du W, Pogoriler J (2006) Retinoblastoma family genes. Oncogene 25: 5190–5200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Cobrinik D (2005) Pocket proteins and cell cycle control. Oncogene 24: 2796–2809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Bosco G (2010) Cell cycle: Retinoblastoma, a trip organizer. Nature 466: 1051–1052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Burkhart DL, Sage J (2008) Cellular mechanisms of tumour suppression by the retinoblastoma gene. Nat Rev Cancer 8: 671–682. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Acharya P, Negre N, Johnston J, Wei Y, White KP, et al. (2012) Evidence for autoregulation and cell signaling pathway regulation from genome-wide binding of the Drosophila retinoblastoma protein. G3 2: 1459–1472. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Tsai KY, Hu Y, Macleod KF, Crowley D, Yamasaki L, et al. (1998) Mutation of E2F-1 suppresses apoptosis and inappropriate S phase entry and extends survival of Rb-deficient mouse embryos. Mol Cell 2: 293–304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Morgenbesser SD, Williams BO, Jacks T, DePinho RA (1994) p53-dependent apoptosis produced by Rb-deficiency in the developing mouse lens. Nature 371: 72–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Hsieh JK, Chan FS, O'Connor DJ, Mittnacht S, Zhong S, et al. (1999) RB regulates the stability and the apoptotic function of p53 via MDM2. Mol Cell 3: 181–193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Ianari A, Natale T, Calo E, Ferretti E, Alesse E, et al. (2009) Proapoptotic function of the retinoblastoma tumor suppressor protein. Cancer Cell 15: 184–194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Lemaire C, Godefroy N, Costina-Parvu I, Rincheval V, Renaud F, et al. (2005) Caspase-9 can antagonize p53-induced apoptosis by generating a p76(Rb) truncated form of Rb. Oncogene 24: 3297–3308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Berge EO, Knappskog S, Geisler S, Staalesen V, Pacal M, et al. (2010) Identification and characterization of retinoblastoma gene mutations disturbing apoptosis in human breast cancers. Mol Cancer 9: 173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Sharma A, Comstock CE, Knudsen ES, Cao KH, Hess-Wilson JK, et al. (2007) Retinoblastoma tumor suppressor status is a critical determinant of therapeutic response in prostate cancer cells. Cancer research 67: 6192–6203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Bowen C, Spiegel S, Gelmann EP (1998) Radiation-induced apoptosis mediated by retinoblastoma protein. Cancer Res 58: 3275–3281. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Knudsen KE, Weber E, Arden KC, Cavenee WK, Feramisco JR, et al. (1999) The retinoblastoma tumor suppressor inhibits cellular proliferation through two distinct mechanisms: inhibition of cell cycle progression and induction of cell death. Oncogene 18: 5239–5245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Ferecatu I, Le Floch N, Bergeaud M, Rodriguez-Enfedaque A, Rincheval V, et al. (2009) Evidence for a mitochondrial localization of the retinoblastoma protein. BMC cell biology 10: 50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Hilgendorf KI, Leshchiner ES, Nedelcu S, Maynard MA, Calo E, et al. (2013) The retinoblastoma protein induces apoptosis directly at the mitochondria. Genes & development 27: 1003–1015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Janicke RU, Walker PA, Lin XY, Porter AG (1996) Specific cleavage of the retinoblastoma protein by an ICE-like protease in apoptosis. Embo J 15: 6969–6978. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Fattman CL, An B, Dou QP (1997) Characterization of interior cleavage of retinoblastoma protein in apoptosis. J Cell Biochem 67: 399–408. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Chen WD, Geradts J, Keane MM, Lipkowitz S, Zajac-Kaye M, et al. (1999) The 100-kDa proteolytic fragment of RB is retained predominantly within the nuclear compartment of apoptotic cells. Mol Cell Biol Res Commun 1: 216–220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Boutillier AL, Trinh E, Loeffler JP (2000) Caspase-dependent cleavage of the retinoblastoma protein is an early step in neuronal apoptosis. Oncogene 19: 2171–2178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Bertin-Ciftci J, Barre B, Le Pen J, Maillet L, Couriaud C, et al. (2013) pRb/E2F-1-mediated caspase-dependent induction of Noxa amplifies the apoptotic effects of the Bcl-2/Bcl-xL inhibitor ABT-737. Cell death and differentiation 20: 755–764. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Tan X, Martin SJ, Wang JYJ (1997) Degradation of Retinoblastoma protein in Tumor Necrosis Factor- and CD95-induced Cell Death. J Biol Chem 272: 9613–9616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Fattman CL, An B, Sussman L, Dou QP (1998) p53-independent dephosphorylation and cleavage of retinoblastoma protein during tamoxifen-induced apoptosis in human breast carcinoma cells. Cancer Lett 130: 103–113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Borges HL, Bird J, Wasson K, Cardiff RD, Varki N, et al. (2005) Tumor promotion by caspase-resistant retinoblastoma protein. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 102: 15587–15592. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Le Floch N, Rincheval V, Ferecatu I, Ali-Boina R, Renaud F, et al. (2010) The p76(Rb) and p100(Rb) truncated forms of the Rb protein exert antagonistic roles on cell death regulation in human cell lines. Biochemical and biophysical research communications 399: 173–178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Young AP, Longmore GD (2004) Differential regulation of apoptotic genes by Rb in human versus mouse cells. Oncogene 23: 2587–2599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. van den Heuvel S, Dyson NJ (2008) Conserved functions of the pRB and E2F families. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 9: 713–724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Chen HZ, Tsai SY, Leone G (2009) Emerging roles of E2Fs in cancer: an exit from cell cycle control. Nat Rev Cancer 9: 785–797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Frolov MV, Dyson NJ (2004) Molecular mechanisms of E2F-dependent activation and pRB-mediated repression. J Cell Sci 117: 2173–2181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Dimova DK, Stevaux O, Frolov MV, Dyson NJ (2003) Cell cycle-dependent and cell cycle-independent control of transcription by the Drosophila E2F/RB pathway. Genes Dev 17: 2308–2320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Moon NS, Di Stefano L, Dyson N (2006) A gradient of epidermal growth factor receptor signaling determines the sensitivity of rbf1 mutant cells to E2F-dependent apoptosis. Mol Cell Biol 26: 7601–7615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Moon NS, Di Stefano L, Morris EJ, Patel R, White K, et al. (2008) E2F and p53 induce apoptosis independently during Drosophila development but intersect in the context of DNA damage. PLoS Genet 4: e1000153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Tanaka-Matakatsu M, Xu J, Cheng L, Du W (2009) Regulation of apoptosis of rbf mutant cells during Drosophila development. Dev Biol 326: 347–356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Du W, Dyson N (1999) The role of RBF in the introduction of G1 regulation during Drosophila embryogenesis. Embo J 18: 916–925. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Milet C, Rincheval-Arnold A, Mignotte B, Guenal I (2010) The Drosophila retinoblastoma protein induces apoptosis in proliferating but not in post-mitotic cells. Cell Cycle 9: 97–103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Wee LJ, Tan TW, Ranganathan S (2007) CASVM: web server for SVM-based prediction of caspase substrates cleavage sites. Bioinformatics 23: 3241–3243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Wee LJ, Tan TW, Ranganathan S (2006) SVM-based prediction of caspase substrate cleavage sites. BMC Bioinformatics 7 Suppl 5S14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Hawkins CJ, Yoo SJ, Peterson EP, Wang SL, Vernooy SY, et al. (2000) The Drosophila caspase DRONC cleaves following glutamate or aspartate and is regulated by DIAP1, HID, and GRIM. J Biol Chem 275: 27084–27093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Snipas SJ, Drag M, Stennicke HR, Salvesen GS (2008) Activation mechanism and substrate specificity of the Drosophila initiator caspase DRONC. Cell death and differentiation 15: 938–945. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Perez-Garijo A, Shlevkov E, Morata G (2009) The role of Dpp and Wg in compensatory proliferation and in the formation of hyperplastic overgrowths caused by apoptotic cells in the Drosophila wing disc. Development 136: 1169–1177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Worley MI, Setiawan L, Hariharan IK (2012) Regeneration and transdetermination in Drosophila imaginal discs. Annual review of genetics 46: 289–310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Ryoo HD, Bergmann A (2012) The role of apoptosis-induced proliferation for regeneration and cancer. Cold Spring Harbor perspectives in biology 4: a008797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Igaki T (2009) Correcting developmental errors by apoptosis: lessons from Drosophila JNK signaling. Apoptosis 14: 1021–1028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Ryoo HD, Gorenc T, Steller H (2004) Apoptotic cells can induce compensatory cell proliferation through the JNK and the Wingless signaling pathways. Dev Cell 7: 491–501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Hassler M, Singh S, Yue WW, Luczynski M, Lakbir R, et al. (2007) Crystal structure of the retinoblastoma protein N domain provides insight into tumor suppression, ligand interaction, and holoprotein architecture. Molecular cell 28: 371–385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Perez-Garijo A, Martin FA, Morata G (2004) Caspase inhibition during apoptosis causes abnormal signalling and developmental aberrations in Drosophila. Development 131: 5591–5598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Perez-Garijo A, Martin FA, Struhl G, Morata G (2005) Dpp signaling and the induction of neoplastic tumors by caspase-inhibited apoptotic cells in Drosophila. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 102: 17664–17669. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Wells BS, Yoshida E, Johnston LA (2006) Compensatory proliferation in Drosophila imaginal discs requires Dronc-dependent p53 activity. Curr Biol 16: 1606–1615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Huh JR, Guo M, Hay BA (2004) Compensatory proliferation induced by cell death in the Drosophila wing disc requires activity of the apical cell death caspase Dronc in a nonapoptotic role. Curr Biol 14: 1262–1266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Mollereau B, Perez-Garijo A, Bergmann A, Miura M, Gerlitz O, et al. (2013) Compensatory proliferation and apoptosis-induced proliferation: a need for clarification. Cell death and differentiation 20: 181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Herrera SC, Martin R, Morata G (2013) Tissue homeostasis in the wing disc of Drosophila melanogaster: immediate response to massive damage during development. PLoS genetics 9: e1003446. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Figure S1 in File S1. RBF contains a consensus site of caspase cleavage. (A) RBF sequence was scanned for potential caspase cleavage site(s) using the CASVM web server (http://www.casbase.org/). This was done with the P14P10′ window (tetrapeptide cleavage sites with ten additional upstream and downstream flanking sequences) which have the highest accuracy. Only one predicted caspase cleavage site was found in RBF: TELD-253. (B) Amino acid sequences alignment of retinoblastoma protein homologs. Amino acid sequences of proteins from H. sapiens (top), C. elegans (middle), D. melanogaster (bottom) were aligned using the Clustal Omega program. Dashes represent gaps in the sequence. Amino acid sequences shown in boxes correspond to consensus caspase cleavage sites. (C) RBF and RBF cleaved forms analysed by Western Blot. Proteins extracts are made from S2 cells transfected with pActine Gal4 vector or pUAS RBFp76-HA (RBFp76-HA), pUAS RBF-HA (RBF-HA) or pUAS RBFD253A-HA (RBFD253A-HA) (Effecten kit, Quiagen). 2.106 cells were cryolysed in PBS pH 7.6 and homogenized in buffer containing 50 mM Tris-Cl pH = 7,4, 150 mM NaCl, 1% NP40, 1 mM DTT, AEBSFSC. Proteins were separated in 4–12% Bis-Tris polyacrylamide gels according to the manufacturer's instructions (BioRad) and transferred onto PVDF membrane (Millipore). Blots were incubated with mouse anti-HA (HA.11, Covance) and rabbit polyclonal anti-Actin (1∶500, Sigma). Arrow shows wholes RBF forms and dotted-line arrow shows RBFp76. Figure S2 in File S1. Quantification of RBF and RBFD253A protein rates and rbf mRNA. (A) RBF and RBFD253A protein rates detected by Western blot analysis. Protein extracts were prepared from embryos carrying the da-Gal4 driver to induce UAS-RBF and UAS-RBFD253A expressions ubiquitously. Three genotypes were tested: da-Gal4/+ (control), da-Gal4/UAS-RBF, UAS-RBFD253A/+; da-Gal4/+ at 25°C. Actin was used as a loading control, and an RBF antibody was used to detect RBF and RBFD253A (rabbit polyclonal anti-RBF,1∶500, Custom antibody, Proteogenix and rabbit polyclonal anti-Actin, 1∶500, Sigma). Immunoreactive bands were detected by Immobilon™ Western Chemiluminescent HRP Substrate (Millipore) with facilities of ChemiDoc MP System (BioRad). (B) Immunoreactive bands were quantified using the Quantity One software. Under these conditions, the level of RBF protein is significantly higher in embryos expressing UAS-RBF and UAS-RBFD253A than in control embryos (asterisk, ANOVA, p = 7.6E-3); furthermore, there is no significant difference between RBF and RBFD253A protein expression levels (ANOVA, p = 0.48). (C) Quantification of rbf mRNA by RT-qPCR in wing imaginal discs. Fifty wing imaginal discs per genotype were dissected on ice. Total RNAs were extracted from each sample using the RNeasy Mini kit (QIAGEN), RT was performed on each sample using random primer oligonucleotides (Invitrogen) with Recombinant Taq DNA Polymerase (Invitrogen). Real-time PCR analysis was performed using the C1000 Touch™ Thermal cycler (Biorad). Data are normalized against rp49 and correspond to the mean of three independent experiments. Error bars are the S.E.M. Asterisks indicate statistical significant difference between two genotypes (Student test, p<0,05). Figure S3 in File S1. RBFD253A is pro-apoptotic in the ZNC and induces more apoptosis than RBF in third instar larvae wing imaginal discs. (A, E) C96-Gal4 and vg-Gal4 expression patterns are visualized by UAS-mtGFP expression in third instar larvae wing imaginal discs. (B–D, F–H) Apoptotic cells are labeled with Acridine Orange in wing imaginal discs (2 min in 100 ng/ml AO, Molecular Probes); specific staining of apoptotic cells corresponds to bright white patches. (B, F) C96-Gal4/+ and vg-Gal4/+ control discs have few apoptotic cells. (C) C96-Gal4/UAS-RBF wing discs are similar to control. (D) Some apoptotic cells are observed within the C96-Gal4 expression domain in UAS-RBFD253A/X; C96-Gal4/+ discs (white arrows). (G, H) Apoptotic cells are observed within the vg-Gal4 expression domain in vg-Gal4/+; UAS-RBF/+ and UAS-RBFD253A/X; vg-Gal4/+ wing discs (white arrows). (G) The white arrowhead indicates a zone at the center of the pouch where cells are not AO-labeled in vg-Gal4/+; UAS-RBF/+ wing discs. All discs are shown with posterior to the top. Discs were mounted in AO and observed with a conventional Leica DMRHC research microscope using the L5 filter to detect AO fluorescence. Figure S4 in File S1. RBFD253A expression at the antero-posterior boundary of wing imaginal discs induces more apoptosis than RBF, but adult phenotypes are similar. (A–C) Distances between veins 3 and 4 (dv3-v4) were measured at the posterior third of the wings using the Adobe Photoshop CS3 software, as indicated by the black lines. 20 wings were measured to estimate the average distance between veins 3 and 4 (dv3-v4±s.e.m) for each genotype: (A) ptc-Gal4/+ control wings, (B) ptc-Gal4/UAS-RBF flies, (C) UAS-RBFD253A; ptc-Gal4 flies. UAS-RBF as well as UAS-RBFD253A expression under the control of ptc-Gal4 brings veins 3 and 4 closer. (D) ptc-Gal4 expression pattern is visualized by UAS-mtGFP expression in third instar larvae wing imaginal discs. Apoptotic cells are labeled with TUNEL (E–G) or Acridine Orange (H–J) in the wing imaginal discs; specific staining of apoptotic cells corresponds to bright white patches. (E, H) Few apoptotic cells are observed in ptc-Gal4/+ control discs. (F, G, I, J) In ptc-Gal4/UAS-RBF and UAS-RBFD253A/+; ptc-Gal4/+ discs, apoptotic cells are observed within the ptc-Gal4 expression domain (white arrows). More apoptotic cells are observed in UAS-RBFD253A/+; ptc-Gal4/+ discs. All discs are shown posterior to the top. Discs were observed with a conventional Leica DMRHC research microscope using the L5 filter to detect AO fluorescence and using the N2.1 filter to detect TUNEL. Figure S5 in File S1. RBFD253A expression at the antero-posterior boundary of wing discs alters the Wg pattern. (A–C) anti-Wg (green) and anti-RBF (red) staining with enlarged views of boxed areas. (A) Wg pattern in control ptc-Gal4/+ wing disc. (B) ptc-Gal4/UAS-RBF discs have the same Wg pattern than control discs. (C) In UAS-RBFD253A/X; ptc-Gal4/+ discs, the Wg pattern is altered (white arrowhead) when compared to control discs. More wg expressing cells adjacent to the RBFD253A expression domain in the posterior compartment are observed. All discs are shown with posterior to the top. Discs were observed with a conventional Leica DMRHC research microscope using the L5 filter to detect Wg-associated fluorescence and using the N2.1 filter to detect RBF-associated fluorescence. Figure S6 in File S1. Expression of RBFD253A and co-expression of RBF and p35 lead to different Wg patterns. (A–C) RBF immuno-staining (red). (D–F) anti-Wg immuno-staining (green). (D) Control Wg pattern in UAS-p35/X; en-Gal4/+ wing disc. (E) In UAS-p35/X; en-Gal4/+; UAS-RBF/+ wing discs, the Wg pattern is altered when compared to control discs: ectopic patches are observed in the posterior compartment (arrows and box b). (F) In UAS-RBFD253A/X; en-Gal4/+ wing discs, the Wg pattern is altered when compared to the control, and an enlargement of this pattern is observed in the posterior compartment (box a). All discs are shown with posterior to the top. Discs were observed with a conventional Leica DMRHC research microscope using the L5 filter to detect Wg and the N2.1 filter to detect RBF associated fluorescence.

(ZIP)