Abstract

Background

The burden of hypertension is high in Africa, and due to rapid population growth and ageing, the exact burden on the continent is still far from being known. We aimed to estimate the prevalence and awareness rates of hypertension in Africa based on the cut off “≥140/90 mm Hg”.

Methods

We conducted a systematic search of Medline, EMBASE and Global Health. Search date was set from January 1980 to December 2013. We included population-based studies on hypertension, conducted among people aged ≥15 years and providing numerical estimates on the prevalence of hypertension in Africa. Overall pooled prevalence of hypertension in mixed, rural and urban settings in Africa were estimated from reported crude prevalence rates. A meta-regression epidemiological modelling, using United Nations population demographics for the years 1990, 2000, 2010 and 2030, was applied to determine the prevalence rates and number of cases of hypertension in Africa separately for these four years.

Results

Our search returned 7680 publications, 92 of which met the selection criteria. The overall pooled prevalence of hypertension in Africa was 19.7% in 1990, 27.4% in 2000 and 30.8% in 2010, each with a pooled awareness rate (expressed as percentage of hypertensive cases) of 16.9%, 29.2% and 33.7%, respectively. From the modelling, over 54.6 million cases of hypertension were estimated in 1990, 92.3 million cases in 2000, 130.2 million cases in 2010, and a projected increase to 216.8 million cases of hypertension by 2030; each with an age-adjusted prevalence of 19.1% (13.9, 25.5), 24.3% (23.3, 31.6), 25.9% (23.5, 34.0), and 25.3% (24.3, 39.7), respectively.

Conclusion

Our findings suggest the prevalence of hypertension is increasing in Africa, and many hypertensive individuals are not aware of their condition. We hope this research will prompt appropriate policy response towards improving the awareness, control and overall management of hypertension in Africa.

Introduction

Hypertension and other cardiovascular diseases rank among the leading causes of disabilities and deaths from non-communicable diseases (NCDs) in Africa [1], [2], with rising prevalence and death rates now observed more in young and active adults [3]. Recently, the African Union (AU) reported that hypertension is one of the greatest health challenges after HIV/AIDS in the continent [4]. This is in fact a priority globally as conclusions from the 2011 United Nations high level meeting on NCDs focus on a reduction of hypertension and other NCDs, especially in Africa, where the burden is rising at a faster rate compared to other parts of the world [5]. Worldwide, cardiovascular diseases account for about 17 million deaths, with complications from poorly controlled hypertension resulting in over 7.5 million deaths and 57 million disability adjusted life years (DALYS) [6].

The relatively higher prevalence of hypertension in Africa has been linked to population growth and ageing, rising urbanization, mass migration from rural to urban areas, and an increased uptake of western lifestyles including tobacco and alcohol consumption [3], [7]. Public health response from the governments of many African nations still remains low, as research findings show that a high number of hypertensive individuals are currently unaware of their condition [8]. Many African countries are yet to implement high blood pressure awareness and control programmes on a population-wide scale, even to people with very high risk of cardiovascular complications [9]. Even with a widely popularised availability of hypertension treatments in some African countries [10], reports show that many rural dwellers are still faced with lack of antihypertensive medications and poor management of cases of hypertension [11]. The WHO has recommended a need for strong public health policies, multisectoral approach, and available and affordable treatment options toward reducing this growing burden of hypertension in Africa [2].

Despite reports of a higher prevalence of hypertension in Africa compared to other world regions [2], public health experts believe the real burden is still far from being known [12]. Many studies in the 1980s and early 1990s were based on the old definition of hypertension (≥160/95 mm Hg) [8], [12]. These surveys may possibly underestimate the prevalence of hypertension in Africa in comparison to newer surveys based on ≥140/90 mm Hg. Moreover, even within studies based on similar case definitions, the variations in reported estimates still suggest the need for more systematic and accurate estimates from larger number of studies towards appropriately informing health service planning and a better response to hypertension in Africa. For example, the World Health Organization (WHO) reported that the prevalence of hypertension in the African region was highest globally in 2008, with an estimated prevalence of 46% [13]. This, though vital for instituting relevant public health response in the continent, elucidates a conflicting state of data in comparison to other hypertension prevalence estimates in Africa which are relatively lower [14], [15]. Thus, with an increased research output on hypertension in Africa in the last two decades, a systematic review of population-based studies was conducted towards providing an improved continent-wide estimate of the prevalence and awareness rate of hypertension in Africa, which hopefully may encourage healthy public health policy for a value-added management of hypertension in the region.

Methods

Search strategy

After identifying Medical Subject Headings (MESH) and keywords, a final search strategy was developed. Searches were conducted on three main databases: Medline, EMBASE and Global Health. The search date was set from January 1980 to December 2013. African countries were as listed on the World Bank list of economies (July 2012) [16]. See Table 1 for details of the search terms.

Table 1. Search terms.

| # | Search terms |

| 1 | africa/ or africa, northern/ or algeria/ or egypt/ or libya/ or morocco/ or africa, central/ or cameroon/ or central african republic/ or chad/ or congo/ or “democratic republic of the congo”/ or equatorial guinea/ or gabon/ or africa, eastern/ or burundi/ or djibouti/ or eritrea/ or ethiopia/ or kenya/ or rwanda/ or somalia/ or sudan/ or tanzania/ or uganda/ or africa, southern/ or angola/ or botswana/ or lesotho/ or malawi/ or mozambique/ or namibia/ or south africa/ or swaziland/ or zambia/ or zimbabwe/ or africa, western/ or benin/ or burkina faso/ or cape verde/ or cote d'ivoire/ or gambia/ or ghana/ or guinea/ or guinea-bissau/ or liberia/ or mali/ or mauritania/ or niger/ or nigeria/ or senegal/ or sierra leone/ or togo/ |

| 2 | exp vital statistics/ or exp incidence/ |

| 3 | (incidence* or prevalence* or morbidity or mortality).tw. |

| 4 | (disease adj3 burden).tw. |

| 5 | exp “cost of illness”/ |

| 6 | exp quality-adjusted life years/ |

| 7 | QALY.tw. |

| 8 | Disability adjusted life years.mp. |

| 9 | (initial adj2 burden).tw. |

| 10 | exp risk factors/ |

| 11 | 2 or 3 or 4 or 5 or 6 or 7 or 8 or 9 or 10 |

| 12 | cardiovascular diseases/ or heart diseases/ or exp hypertension/ or peripheral vascular diseases/ |

| 13 | Hypertensive heart disease.mp. [mp = title, abstract, subject headings, heading word, drug trade name, original title, device manufacturer, drug manufacturer, device trade name, keyword] |

| 14 | 12 or 13 |

| 15 | 1 and 11 and 14 |

| 16 | limit 15 to (humans and yr = “1980 -Current”) |

Selection criteria and case definitions

Cross-sectional population- and/or community-based studies on hypertension were included, published on or after 1980, conducted among people aged ≥15 years, and providing numerical estimates on the prevalence of hypertension in Africa. Studies conducted before 1980, hospital-based, without numerical estimates, on non-human subjects, and that were mainly reviews were all excluded. There were no language restrictions.

Case definitions of hypertension across retained studies comply with the following:

systolic blood pressure (≥140 mm Hg) and/or diastolic blood pressure (≥90 mm Hg) and/or self-reported use of antihypertensive medications;

the sixth and seventh report of the Joint National Committee on prevention, detection, evaluation, and treatment of high blood pressure (JNC 6 & 7) [17], [18]; and

the 1999 and 2003 World Health Organization/International Society of Hypertension (WHO/ISH) definitions and classification of blood pressure levels [19]

See Table 2 for details. For the definition of the awareness rate of hypertension in this study, we included studies estimating the prevalence of hypertension based on the definitions above, with awareness rate also being estimated among all identified cases of hypertension and defined as self-report by respondents of any prior diagnosis of hypertension by a doctor or certified health care professional, and excluding women diagnosed during pregnancy, as described by the WHO [19].

Table 2. Classification of blood pressure for adults.

| Category | JNC | WHO/ISH | ||||||

| 6 | 7 | 1999 | 2003 | |||||

| SBP | DBP | SBP | DBP | SBP | DBP | SBP | DBP | |

| Optimal | <120 | and <80 | - | - | <120 | <80 | - | - |

| Normal | 120–129 | and 80–84 | <120 | and <80 | <130 | <85 | - | - |

| Borderline (JNC)/or High Normal (WHO/ISH) | 130–139 | or 85–89 | 120–139 (Pre-hypertension) | or 80–89 (Pre-hypertension) | 130–139 | 85–89 | - | - |

| Hypertension (JNC)/Grade 1 (WHO/ISH) | ≥140 | or ≥90 | ≥140 | or ≥90 | 140–159 | 90–99 | 140–159 | 90–99 |

| Stage 1 (JNC)/or Subgroup Borderline (WHO/ISH) | 140–159 | or 90–99 | 140–159 | or 90–99 | 140–149 | 90–94 | - | - |

| Stage 2 (JNC)/or Grade 2 (WHO/ISH) | 160–179 | or 100–109 | ≥160 (Stage 2) | or ≥100 (Stage 2) | 160–179 | 100–109 | 160–179 | 100–109 |

| Stage 3 (JNC)/or Grade 3 (WHO/ISH) | ≥180 | or ≥110 | - | - | ≥180 | ≥110 | ≥180 | ≥110 |

JNC: Joint National Committee on prevention, detection, evaluation, and treatment of high blood pressure, WHO/ISH: World Health Organization/International Society of Hypertension, SBP: systolic blood pressure, DBP: diastolic blood pressure.

Quality criteria

Studies retained were assessed for the following quality:

Study design: Under this, flaws in the design and execution of study were examined. Basically, this assesses methods of estimation of sample size and sampling methods across studies, and the methods of dealing with design specific issues such as: training of study investigators, adherence to standardized protocol for blood pressure measurement, pre-testing and reviewing questionnaires before data entry, and addressing recall and interviewer's bias appropriately;

Study analysis: This assessed the appropriateness of statistical and analytical methods employed across studies in the estimation of hypertension prevalence;

Generalizability to the African population: This broadly assessed if the sample size was representative of a larger population that can be generalized to the total African population

An adaptation of the Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation (GRADE) guidelines was applied in the final quality grading of studies [20]. See Box S1, Table S1 and Table S2 in File S1 for details.

Data extraction and analysis

All extracted data were stored in Microsoft Excel file format. A parallel search and double extraction were conducted by the authors. Data were abstracted systematically on sample size, mean age or age range, number of hypertension cases, and the respective age- and sex-specific prevalence rates. These were sorted into mixed, urban and rural settings (based on studies that reported them). For studies conducted on the same study site, population or cohort, the first chronologically published study was retained, and all additional data from other studies were included in the selected paper.

From all studies, reported crude prevalence rates of hypertension (all expressed as percentages) were pooled, and reported separately for north Africa and sub-Saharan Africa (central, east, south and west), and with rates for urban and rural settings estimated. These were further categorized into 1990, 2000 and 2010, as obtained from studies conducted before 1995, from 1995 to 2004, from 2005 to 2013, respectively. As noted above, awareness rate of hypertension was estimated as number of people who reported being hypertensive, expressed as a percentage of total number of people in the study population having hypertension. Pooled awareness rates of hypertension for 1990, 2000, and 2010, and rates across mixed, urban and rural settings were estimated, respectively.

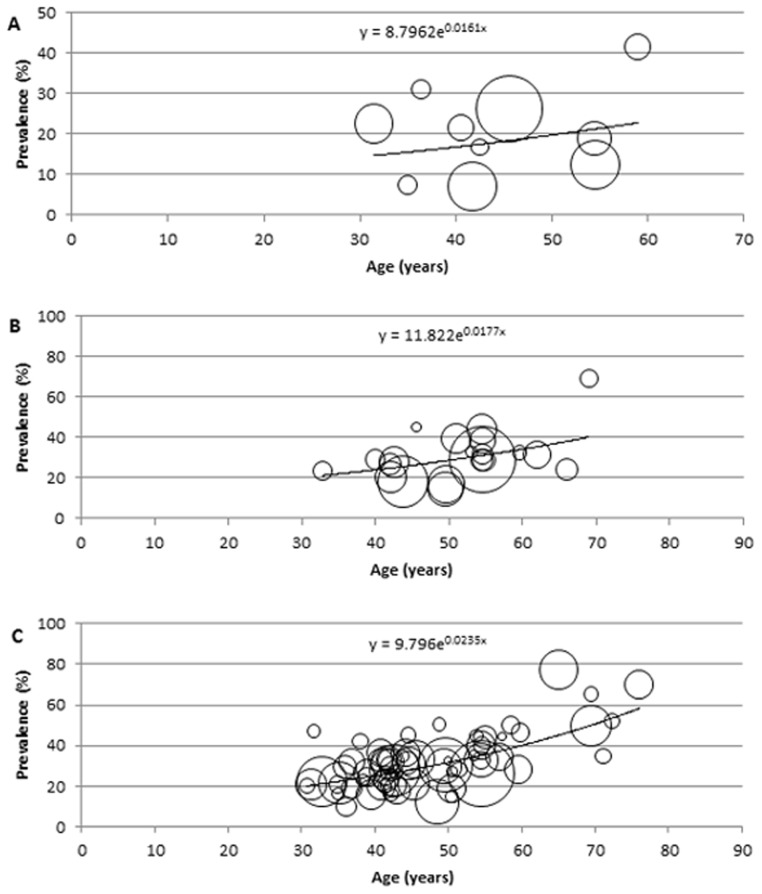

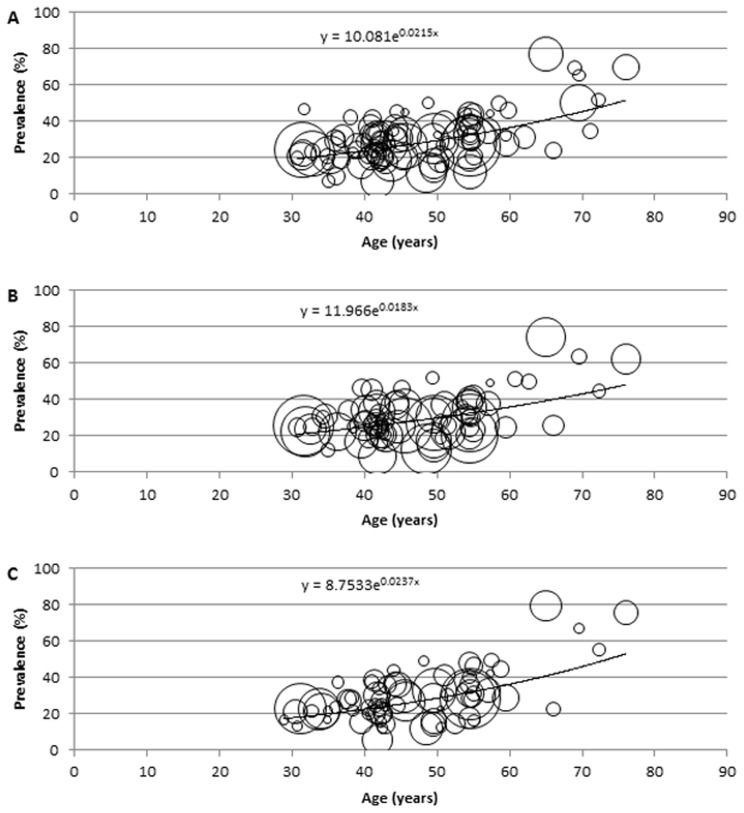

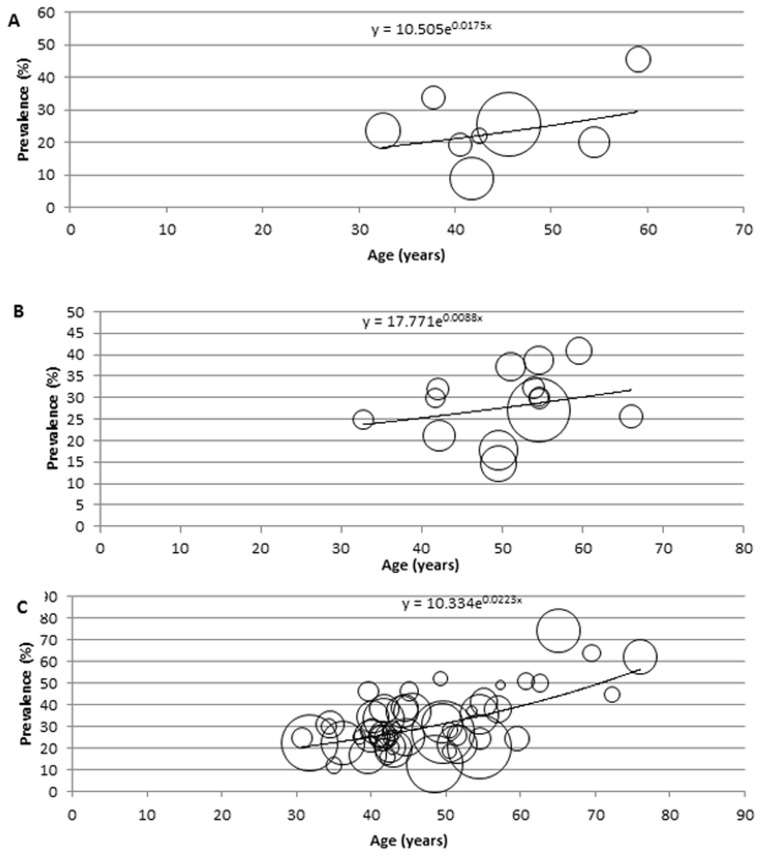

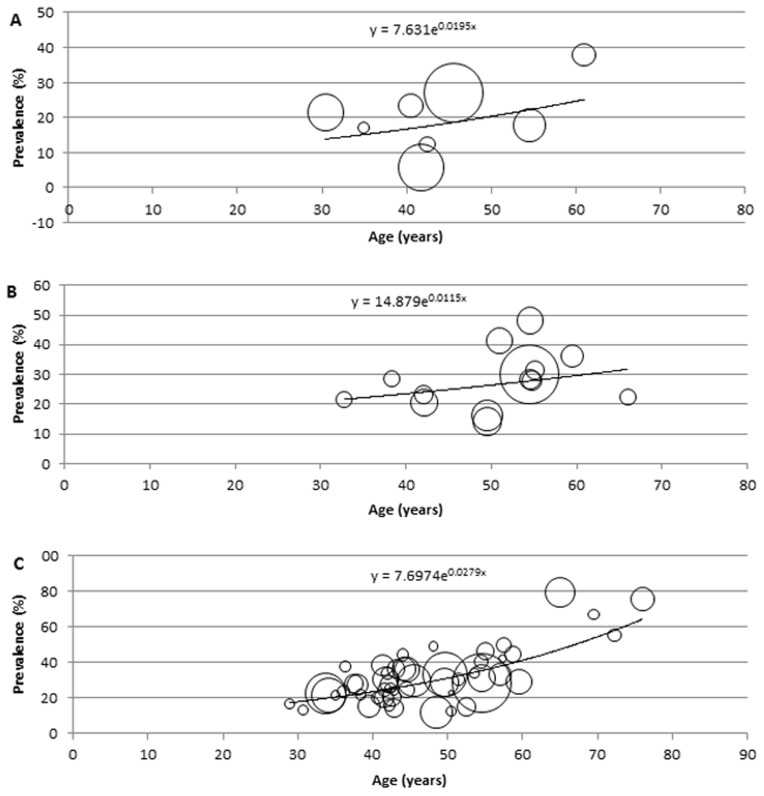

Description of the modelling

For the modelling and estimation of the total cases of hypertension in Africa, a meta-regression epidemiological model was developed, and applied on crude prevalence rates, sample sizes and respective mean age from all data points. In this model, all data points (mainly the crude prevalence rates and mean age) were plotted on a graph on Microsoft Excel, with all extracted crude prevalence rates plotted on the y-axis, i.e. dependent variable, and mean ages corresponding to each prevalence rate are plotted on the x-axis, i.e. independent variable. To account for variation in sample sizes from each data point, bubbles were generated on the graph, with the size of each bubble corresponding to the respective sample size reported. Although, it is well known that the prevalence of hypertension in the population significantly increases with age [21], the relationship between age and the disease may not be necessarily linear. Therefore, we experimented with the models based on linear, logarithmic, exponential, Poisson, polynomial, power function and moving average statistical analyses, respectively, and chose the one which was the most predictive, i.e. in which the proportion of variance (R2) of the disease prevalence explained by age was the greatest. On the model therefore, the fitted curve explaining the largest proportion of variance (best fit) was applied. The equation generated from the fitted curve was then used to determine the prevalence of hypertension in Africa at midpoints of the United Nations (UN) population 5-year age-group population estimates for Africa, for the years 1990, 2000, 2010, respectively [22], while an overall model was developed from all data points (1980–2013) and used to predict the number of hypertension cases and prevalence rates for 2030. All statistical analyses were conducted on Microsoft Excel and Stata 13.1 (Copyright 1985–2013 Stata Corp LP).

Results

Systematic review

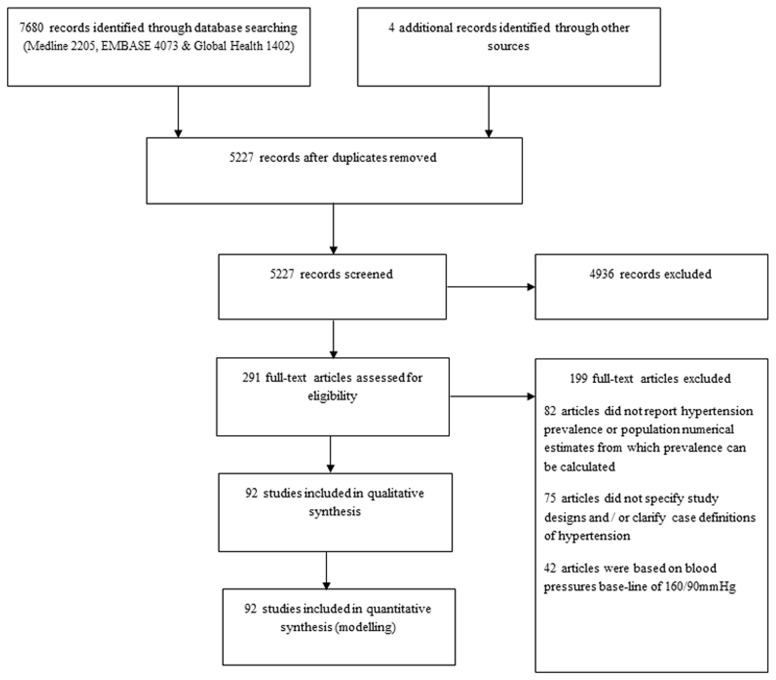

The search returned 7680 publications: Medline (2205), EMBASE (4073) and Global Health (1402). An additional 3 studies were included from other sources (Google Scholar and reference list of relevant reviews). After excluding duplicates, 5227 studies remained. On screening titles for relevance (hypertension studies conducted primarily in an African population setting), 4936 articles were excluded, giving a total of 291 full texts that were assessed. 82 articles did not report hypertension prevalence or population denominators from which prevalence rates can be calculated, 75 articles did not specify study designs and/or clarify case definitions of hypertension, and 42 articles were based on blood pressures base-line of 160/90 mm Hg. A total of 92 studies were finally retained for qualitative synthesis and quantitative analysis ( Figure 1 ).

Figure 1. Flow diagram of search results.

Study characteristics

There were 92 studies conducted across 101 study sites in 31 African countries. Central Africa had 10 study sites, Eastern Africa 21, Northern Africa 12, Southern Africa 15, and Western Africa 43. Nigeria had the highest number of publications with 26 study sites; Ghana and South Africa follow with 7 study sites each, while Cameroon, Tanzania and Tunisia had 6 study sites each (see Tables 3 and 4 ).

Table 3. Study distribution.

| Country | Study sites |

| Central | |

| Cameroon | 6 |

| Chad | 1 |

| DR Congo | 2 |

| Rwanda | 1 |

| East | |

| Eritrea | 1 |

| Ethiopia | 5 |

| Kenya | 3 |

| Seychelles | 1 |

| Sudan | 1 |

| Tanzania | 6 |

| Uganda | 4 |

| North | |

| Algeria | 3 |

| Egypt | 2 |

| Morocco | 1 |

| Tunisia | 6 |

| South | |

| Angola | 2 |

| Madagascar | 1 |

| Malawi | 2 |

| Mozambique | 1 |

| Namibia | 1 |

| South Africa | 7 |

| Zambia | 1 |

| West | |

| Benin | 1 |

| Burkina Faso | 1 |

| Gambia | 1 |

| Ghana | 7 |

| Guinea | 2 |

| Liberia | 1 |

| Nigeria | 26 |

| Senegal | 2 |

| Togo | 2 |

| Duration of study | |

| <1 year | 74 |

| 1–3 years | 22 |

| >3 years | 5 |

| Sample size | |

| <1000 | 54 |

| 1001–3000 | 37 |

| >3000 | 10 |

| Study setting | |

| Rural | 47 |

| Urban | 50 |

| Mixed (sites overlap with urban and rural) | 33 |

Table 4. Summary of data from all studies.

| Country, Setting | Study period | Diagnostic criteria | Mean age (years) | Prevalence % (all) | Prevalence % (men) | Prevalence % (women) |

| CENTRAL | ||||||

| Cameroon, Mixed [44] | 1995 | ≥140/90 mmHg | 49.5 | 16.9 | 17.7 | 16.3 |

| Cameroon, Mixed [45] | 1991 | ≥140/90 mmHg | 41.75 | 7.07 | 8.92 | 5.69 |

| Cameroon, Mixed [46] | 1994 | ≥140/90 mmHg | 54.5 | 18.8 | 20.2 | 17.8 |

| Cameroon, Mixed [46] | 2003 | WHO/ISH 1999 | 54.5 | 38.34 | 40.9 | 36.5 |

| Cameroon, Urban) [47] | 2003 | WHO/ISH 1999 | 31.35 | 24.6 | 25.6 | 23.1 |

| Cameroon, Urban [47] | 2004 | WHO/ISH 1999 | 31.35 | 20.8 | - | - |

| Chad, Rural [48] | 2004 | WHO/ISH 2003 | 35 | 16.4 | 12.2 | 21.8 |

| DR Congo, Mixed [49] | 2009–10 | WHO/ISH 2003 | 54.5 | 40.2 | - | - |

| DR Congo, Urban [50] | 1983–84 | ≥140/90 mmHg | 42.5 | 16.7 | 22.1 | 12.4 |

| Rwanda, Rural [51] | 2007 | JNC 7 | 42.2 | 16.0 | 16.0 | 16.0 |

| EAST | ||||||

| Eritea, Mixed [52] | 2004 | ≥140/90 mmHg | 39.5 | 16.0 | 16.88 | 15.28 |

| Ethiopia, Mixed [28] | 2008 | JNC 7, WHO/ISH 2003 | 36.08 | 9.9 | - | - |

| Ethiopia, Urban [53] | 2012 | JNC 7 | 51.4 | 28.3 | 26 | 30.3 |

| Ethiopia, Urban [54] | 2009 | ≥140/90 mmHg | 50.5 | 19.1 | 22 | 14.9 |

| Ethiopia, Urban [55] | 2006 | ≥140/90 mmHg | 49.5 | 30.0 | 31.5 | 28.9 |

| Ethiopia, Urban [56] | 2009–2010 | JNC 7 | 42.9 | 17.7 | 20.0 | 14.3 |

| Kenya, Rural [57] | 2009–11 | WHO/ISH 2003 | 40.9 | 20.2 | - | - |

| Kenya, Mixed [58] | 2007–08 | ≥140/90 mmHg | 69.5 | 50.1 | - | - |

| Kenya, Urban [59] | 2009–09 | ≥140/90 mmHg | 48.5 | 12.3 | 12.7 | 12 |

| Seychelles, Mixed [60] | 2004 | ≥140/90 mmHg | 44.5 | 31.6 | 38.4 | 24.8 |

| Sudan, Urban [27] | 1988–89 | ≥140/90 mmHg | 35 | 7.5 | - | - |

| Tanzania, Urban [61] | 1998–99 | WHO/ISH 1999 | 54.5 | 28.9 | 27.1 | 30.2 |

| Tanzania, Rural [51] | 2007 | JNC 7 | 42.8 | 27 | 28 | 24 |

| Tanzania, Rural [24] | 2009–2010 | WHO/ISH 2003 | 76 | 69.9 | 62.2 | 75.8 |

| Tanzania, Rural [62] | 1996 | WHO/ISH 1999 | 39.95 | 29.2 | 30 | 28.6 |

| Tanzania, Rural | 1996 | ≥140/90 mmHg | 54.5 | 31.9 | 32.2 | 31.5 |

| Tanzania, Urban [57] | 2009–11 | WHO/ISH 2003 | 36.8 | 19 | - | - |

| Uganda, Rural [63] | 2008–09 | ≥140/90 mmHg | 32.75 | 22.3 | 22.5 | 22.6 |

| Uganda, Rural [64] | 2011 | ≥140/90 mmHg | 42.5 | 20.5 | 20.7 | 20.4 |

| Uganda, Mixed [65] | 2012 | ≥140/90 mmHg | 35.15 | 21.8 | 22.3 | 21.7 |

| Uganda, Rural [66] | 2006 | ≥140/90 mmHg | 42 | 30.4 | 25.4 | 34 |

| NORTH | ||||||

| Algeria, Rural) [67] | 2010 | WHO/ISH 2003 | 58.5 | 50.2 | 51.3 | 49.7 |

| Algeria, Urban [68] | 2004–05 | ≥140/90 mmHg | 54.5 | 32.7 | 24.5 | 40.6 |

| Algeria, Peri-urban [69] | 2006–07 | ≥140/90 mmHg | 55 | 44 | 41.2 | 46.7 |

| Egypt, Mixed [70] | 1991–93 | ≥140/90 mmHg | 45.6 | 26.3 | 25.7 | 26.9 |

| Egypt, Rural [71] | 1999–00 | ≥140/90 mmHg | 42.5 | 27.9 | - | - |

| Morocco, Mixed [72] | 2000 | ≥140/90 mmHg | 51 | 39.6 | 37.2 | 41.3 |

| Tunisia, Mixed [73] | 2004–05 | JNC 7 | 44.6 | 31.07 | 25.0 | 36.1 |

| Tunisia, Mixed [74] | 2004–05 | ≥140/90 mmHg | 49.6 | 30.6 | 27.3 | 33.1 |

| Tunisia, Mixed [75] | 2002–03 | ≥140/90 mmHg | 54.5 | 44.3 | 38.7 | 48.2 |

| Tunisia, Urban [76] | 1995 | ≥140/90 mmHg | 54.5 | 28.9 | 30 | 28.4 |

| Tunisia, Rural [77] | 2008–09 | WHO/ISH 2003 | 72.3 | 52 | 45 | 55.5- |

| Tunisia, Mixed [25] | 2002–03 | ≥140/90 mmHg | 69 | 69.3 | - | - |

| SOUTH | ||||||

| Angola, Urban [78] | 2009–10 | JNC 7 | 44.5 | 45.2 | 46.3 | 44.2 |

| Angola, Mixed [79] | 2011 | ≥140/90 mmHg | 41.5 | 23 | 26.4 | 19.8 |

| Madagascar, Urban [80] | 1996–97 | ≥140/90 mmHg | 32.75 | 23.3 | 24.9 | 21.7 |

| Malawi, Rural [51] | 2007 | JNC 7 | 38.4 | 23 | 24.5 | 22 |

| Malawi, Mixed [81] | 2009 | ≥140/90 mmHg | 45.5 | 33.2 | 36.9 | 29.9 |

| Mozambique, Mixed [82] | 2005 | WHO/ISH 1999 | 54.5 | 33.1 | 35.7 | 31.2 |

| Namibia, Urban [57] | 2009–11 | WHO/ISH 2003 | 36.9 | 32 | - | - |

| South Africa, Rural [83] | 2004–05 | ≥140/90 mmHg | 59.5 | 28.0 | 24.5 | 29.2 |

| South Africa, Rural [84] | 2010 | ≥140/90 mmHg | 54.5 | 26.2 | 20.8 | 28.5 |

| South Africa, Mixed [23] | 2008 | ≥140/90 mmHg | 65 | 77.3 | 74.4 | 79.6 |

| South Africa, Mixed [85] | 1982 | ≥140/90 mmHg | 41 | 41.6 | 45.6 | 37.75 |

| South Africa, Mixed [86] | 1990 | ≥140/90 mmHg | 40.5 | 21.5 | 19.2 | 23.4 |

| South Africa, Peri-urban [87] | 1996 | ≥140/90 mmHg | 42 | 27.1 | 31.9 | 23.4 |

| South Africa, Rural [88] | 2002 | JNC 7 | 59.5 | 32.6 | - | - |

| Zambia, Urban [89] | 2009–10 | WHO/ISH 2003 | 57 | 34.8 | 38 | 33.3 |

| WEST | ||||||

| Benin, Mixed [90] | 2008 | ≥140/90 mmHg | 42.7 | 27.9 | - | - |

| Burkina Faso, Urban [91] | 2004 | ≥140/90 mmHg | 54.5 | 40.2 | - | - |

| Gambia, Mixed [92] | 1998–99 | ≥140/90 mmHg | 43.7 | 18.4 | - | - |

| Ghana, Rural [93] | 2004–05 | ≥140/90 mmHg | 42.4 | 25.4 | 24.1 | 25.9 |

| Ghana, Mixed [94] | 2004 | ≥140/90 mmHg | 35.9 | 29.4 | 31.04 | 28.07 |

| Ghana, Rural [95] | 2003 | ≥140/90 mmHg | 53 | 32.8 | - | - |

| Ghana, Mixed [96] | 2001 | ≥140/90 mmHg | 54.7 | 28.7 | 29.9 | 28 |

| Ghana, Rural [97] | 2006–07 | ≥140/90 mmHg | 53.5 | 35 | 37.2 | 34.1 |

| Ghana, Rural [98] | 2002–10 | JNC 7. WHO/ISH 2003 | 66 | 24.1 | 25.7 | 22.5 |

| Ghana, Rural [99] | 2012 | ≥140/90 mmHg | 53.84 | 44.7 | - | - |

| Guinea, Mixed [100] | 2003 | ≥140/90 mmHg | 62 | 31.4 | - | - |

| Guinea, Rural [101] | 2001 | ≥140/90 mmHg | 45.5 | 45.2 | - | - |

| Liberia, Rural [102] | 1991–92 | ≥140/90 mmHg | 54.5 | 12.5 | - | - |

| Nigeria, Mixed [103] | 2010–11 | JNC 6 | 71.1 | 34.7 | - | - |

| Nigeria, Semi-urban [104] | 2007–08 | JNC 7 | 44.2 | 36.57 | 36.79 | 36.39 |

| Nigeria, Semi-urban [105] | 2011–12 | JNC 7, WHO/ISH 2003 | 41.5 | 25.2 | 24.7 | 24.7 |

| Nigeria, Rural [106] | 2010–11 | ≥140/90 mmHg | 57.3 | 44.5 | 49.3 | 42.3 |

| Nigeria, Rural [107] | 2012–13 | JNC 7 | 41.3 | 20.2 | 20.5 | 20.1 |

| Nigeria, Urban [108] | 2006–10 | JNC 7 | 41.9 | 33 | 38.3 | 27.8 |

| Nigeria, Mixed [109] | 2008 | JNC 7 | 48.7 | 50.5 | 52 | 49.3 |

| Nigeria, Rural [110] | 2011 | JNC 7 | 49.7 | 13.2 | 15 | 11.9 |

| Nigeria, Urban [111] | 1987–88 | ≥140/90 mmHg | 36.35 | 31.1 | 34 | 17 |

| Nigeria, Mixed [44] | 1995 | ≥140/90 mmHg | 49.5 | 14.5 | 14.7 | 14.3 |

| Nigeria, Rural [112] | 2005–06 | WHO/ISH 2003 | 59.8 | 46.4 | 50.2 | 44.8 |

| Nigeria, Semi-urban [113] | 2012 | ≥140/90 mmHg | 31.7 | 47 | 30.1 | 16.8 |

| Nigeria, Mixed [114] | 2009 | ≥140/90 mmHg | 34.9 | 21.1 | - | - |

| Nigeria, Semi-urban [115] | 2002–03 | JNC 6, WHO/ISH 1999 | 55 | 21 | 23.3 | 16.4 |

| Nigeria, Rural [57] | 2009–11 | WHO/ISH 2003 | 45.3 | 21 | - | - |

| Nigeria, Mixed [116] | 2009–10 | JNC 7 | 38.9 | 24.8 | 25.9 | 23.6 |

| Nigeria, Semi-urban [117] | 2011–12 | ≥140/90 mmHg | 50 | 32.5 | - | - |

| Nigeria, Urban [118] | 2009–10 | ≥140/90 mmHg | 43.88 | 34.8 | - | - |

| Nigeria, Mixed [119] | 2011–12 | ≥140/90 mmHg | 41.7 | 31.8 | 33.5 | 30.5 |

| Nigeria, Urban [120] | 2006–07 | ≥140/90 mmHg | 50.5 | 27.1 | 28.4 | 22.9 |

| Nigeria, Rural [121] | 2002–05 | JNC 7 | 42.1 | 20.8 | 21.1 | 20.5 |

| Nigeria, Urban) [122] | 2007–08 | ≥140/90 mmHg | 41.6 | 33 | 28.1 | 36.4 |

| Nigeria, Rural [123] | 2004–05 | ≥140/90 mmHg | 30.7 | 20.2 | 24.8 | 13.2 |

| Nigeria, Semi-urban [124] | 2011 | JNC 7 | 50.5 | 15 | 18.8 | 12.5 |

| Nigeria, Mixed [125] | 2007–08 | ≥140/90 mmHg | 40.8 | 32.8 | - | - |

| Nigeria, Mixed [126] | 2009–10 | WHO/ISH 2003 | 38.02 | 42.2 | 46.3 | 37.7 |

| Senegal, Urban [127] | 1989–90 | ≥140/90 mmHg | 31.45 | 22.5 | 23.6 | 21.5 |

| Senegal, Urban [26] | 2009 | ≥140/90 mmHg | 69.5 | 65.4 | 63.9 | 67.1 |

| Togo, Urban [128] | 2009–10 | ≥140/90 mmHg | 39 | 26.6 | 25.7 | 27.6 |

| Togo, Urban [129] | 2011 | ≥140/90 mmHg | 40.8 | 36.7 | 34.6 | 38.4 |

JNC: Joint National Committee on prevention, detection, evaluation, and treatment of high blood pressure, WHO/ISH: World Health Organization/International Society of Hypertension.

73% of studies were completed within a one year, with over 50% carried out in urban settings. The overall sample size from all retained studies was 197734, with a mean and median of 1958 and 1200 respectively. From all studies, the weighted mean systolic and diastolic blood pressures were 129.6 mm Hg and 78.0 mm Hg respectively. Studies were mostly conducted on people aged ≥20 years, with an estimated overall mean age of 47.4 years, ranging from 30.7 to 76 years. For the age determination of subjects across selected studies, birth certificates were mostly employed, and in the absence of valid age-verification documents, subjects' age were determined from historical landmarks.

Prevalence and awareness rates of hypertension in Africa

Across all study settings, an elderly South African setting recorded the highest prevalence of hypertension in 2008 (77.3%, mean age 65 years) [23]. Other settings reporting higher prevalence rates of hypertension were also in older adult population surveys in Tanzania in 2010 (69.9%, mean age 76 years), Tunisia in 2003 (69.3%, mean age 69 years), and Senegal in 2009 (65.4%, mean age 69.5 years) respectively [24]–[26]. The lowest prevalence rates of hypertension were recorded in Sudan (7.5%, mean age 35 years) and Ethiopia (9.9%, mean age 36.1 years) in 1989 and 2008 respectively [27], [28] (See Table 4 for overall study characteristics).

The pooled crude prevalence in Northern Africa was higher than in sub-Saharan Africa (SSA), with hypertension prevalence of 33.3% in Northern Africa and 27.8% in sub-Saharan Africa. In other parts of SSA, Southern Africa recorded the highest prevalence, with a prevalence of 34.6% (males 35.4%, females 34.2%). Western Africa had a prevalence of 27.3% (males 29.6, females 28.2), Central Africa recorded 21.1% (males 21.5%, females 19.3%), and Eastern Africa had 26.8% (males 25.0, females 26.1) (see Table 5 for details). The overall pooled crude prevalence (weighted means) of hypertension for Africa was 19.7% (males 23.0%, females 20.2%) in 1990, 27.4% (males 26.9, females 28.4) in 2000, and 30.8% (males 29.7, females 31.4). There were not huge differences in hypertension prevalence between urban and rural dwellers, with the exception of 1990, where urban dwellers recorded a prevalence of 17.2% (males 21.1, females 15.1), compared to 11.1% (males 9.4%, females 8.3%) recorded among rural dwellers (with urban and rural dwellers having prevalence of 26.1% versus 26.3% in 2000 and 29.6% versus 29.0% in 2010 respectively) (see Table 6 for details).

Table 5. Regional pooled hypertension prevalence rates and mean blood pressures in Africa.

| Main study characteristics | Prevalence and awareness of hypertension (%) | Weighted mean blood pressure (mm Hg) | ||||||

| Region | Sample size | Mean age | Both sexes (se) | Male (se) | Female (se) | Awareness rate (se) | Mean systolic BP (se) | Mean diastolic BP (se) |

| North | 28046 | 54.3 | 33.3 (2.6) | 29.6 (2.1) | 35.5 (2.6) | 36.2 (9.2) | 129.6 (1.6) | 78.0 (0.8) |

| SSA | 169688 | 46.4 | 27.8 (1.4) | 27.8 (1.6) | 27.8 (1.7) | 30.6 (3.1) | 125.6 (0.9) | 78.9 (0.5) |

| Central | 24206 | 43.7 | 21.1 (2.7) | 21.5 (3.1) | 19.3 (2.9) | 25.1 (4.2) | 119.2 (1.8) | 75.4 (0.9) |

| East | 53312 | 46.0 | 26.8 (2.9) | 25.0 (2.8) | 26.1 (3.4) | 40.9 (6.9) | 127.5 (2.2) | 79.3 (0.8) |

| South | 34753 | 47.5 | 34.6 (4.2) | 35.4 (5.1) | 34.2 (4.6) | 26.4 (7.0) | 123.5 (2.3) | 79.4 (0.9) |

| West | 57417 | 46.9 | 27.3 (1.5) | 29.6 (1.8) | 28.2 (1.9) | 21.7 (2.7) | 128.2 (0.9) | 79.8 (0.8) |

SSA: sub-Saharan Africa, se: standard error.

Table 6. Pooled crude prevalence and awareness of hypertension from all studies.

| Main study characteristics | Prevalence and awareness of hypertension (%) | Weighted mean blood pressure (mm Hg) | ||||||

| Setting | Sample size | Mean age | Both sexes (se) | Male (se) | Female (se) | Awareness rate (se) | Systolic (se) | Diastolic (se) |

| 1990 | ||||||||

| Mixed | 21416 | 44.1 | 19.7 (2.9) | 23.0 (3.3) | 20.2 (3.5) | 16.9 (3.9) | 123.8 (2.2) | 77.5 (1.1) |

| Urban | 6925 | 39.4 | 17.2 (3.5) | 21.1 (4.0) | 15.1 (3.5) | - | - | - |

| Rural | 5796 | 48.8 | 11.1 (2.1) | 9.4 (3.0) | 8.3 (4.4) | - | - | - |

| 2000 | ||||||||

| Mixed | 38294 | 51.2 | 27.4 (2.1) | 26.9 (2.1) | 28.4 (2.5) | 29.2 (4.5) | 126.9 (1.8) | 77.2 (0.9) |

| Urban | 20898 | 45.7 | 26.1 (1.9) | 26.8 (1.5) | 23.9 (1.9) | - | - | - |

| Rural | 11377 | 55.2 | 26.3 (2.3) | 24.5 (3.2) | 25.7 (3.1) | - | - | - |

| 2010 | ||||||||

| Mixed | 126754 | 47.1 | 30.8 (1.6) | 29.7 (1.9) | 31.4 (2.1) | 33.7 (3.9) | 126.9 (1.1) | 79.4 (0.5) |

| Urban | 44114 | 47.4 | 29.6 (2.1) | 28.2 (2.3) | 28.4 (2.5) | - | - | - |

| Rural | 46669 | 48.6 | 29.0 (2.3) | 26.9 (2.7) | 30.1 (2.9) | - | - | - |

se: standard error.

Across selected studies, there is evidence suggesting the awareness of hypertension among people living with the disease has been increasing since 1990; however, the overall awareness rate still remains relatively low in many parts of Africa. From the pooled analysis, a weighted awareness rate (expressed as a percentage of cases of hypertension) of 16.9% was estimated in 1990, 29.2% in 2000 and 33.7% in 2010 (see Tables 5 and 6 for details).

Modelled estimates of hypertension prevalence and number of cases in Africa

The modelling indicated the overall cases and prevalence of hypertension in Africa have been increasing since 1990. In adults aged ≥20 years, 54.6 million cases of hypertension were estimated in 1990 with an age-adjusted prevalence of 19.1% (13.9, 25.5), 92.3 million cases in 2000 with an age-adjusted prevalence of 24.3% (23.3, 31.6), 130.2 million cases in 2010 with an age-adjusted prevalence of 25.9% (23.5, 34.0), and a projected increase to 216.8 million cases of hypertension by 2030 with an age-adjusted prevalence of 25.3% (24.3, 39.7). The general sex distribution revealed the prevalence and number of cases of hypertension were higher among men than women. Among men, the prevalence and number of hypertension cases were both projected to increase between 2010 and 2030. About 29.8 million cases of hypertension were estimated in 1990 (21.2%, 95%CI: 16.5–29.6), 46.8 million cases in 2000 (25.1%, 95%CI: 22.9–31.0), 64.8 million cases in 2010 (26.1%, 95%CI: 23.6–33.6), and a projected increase to 112.1 million cases of hypertension by 2030 (26.4%: 24.5–41.1). However, there was a drop in prevalence among women between 2010 and 2030. 24.8 million cases of hypertension were estimated in 1990 (17.1%, 95%CI: 13.4–27.0), 45.5 million cases in 2000 (23.6%, 95%CI: 21.5–33.3), 65.4 million cases in 2010 (25.7%, 95%CI: 21.7–35.4), and a projected increase to 104.7 million cases of hypertension by 2030, with a drop in prevalence to 24.3% (95%CI: 22.4–38.9) (see Tables 7 – 9 and Figures 2 – 5 ).

Table 7. Estimated hypertension prevalence rates and cases in Africa in both sexes (estimates derived from epidemiological model and UN population demographics).

| Age (years) | 1990 | 2000 | 2010 | 2030 | ||||

| Prevalence (%) = 8.7962e0.0161x | Hypertension cases (000) | Prevalence (%) = 11.822e0.0177x | Hypertension cases (000) | Prevalence (%) = 9.796e0.0235x | Hypertension cases (000) | Prevalence (%) = 10.081e0.0215x | Hypertension cases (000) | |

| 20–24 | 12.5 | 6961.279 | 17.5 | 13134.411 | 16.4 | 15969.503 | 16.2 | 24372.870 |

| 25–29 | 13.6 | 6319.733 | 19.1 | 11761.160 | 18.5 | 15499.070 | 18.0 | 23390.362 |

| 30–34 | 14.7 | 5722.049 | 20.8 | 10540.253 | 20.8 | 14395.931 | 20.1 | 22549.551 |

| 35–39 | 15.9 | 5125.030 | 22.8 | 9662.284 | 23.4 | 12993.072 | 22.3 | 21855.722 |

| 40–44 | 17.3 | 5293.178 | 24.9 | 8844.815 | 26.3 | 11868.440 | 24.9 | 21339.520 |

| 45–49 | 18.7 | 4770.732 | 27.2 | 7956.942 | 29.6 | 11178.983 | 27.7 | 20226.663 |

| 50–54 | 20.3 | 4416.345 | 29.7 | 7076.878 | 33.2 | 10531.041 | 30.8 | 18005.650 |

| 55–59 | 22.0 | 4015.862 | 32.4 | 6135.655 | 37.4 | 9602.545 | 34.3 | 15692.831 |

| 60–64 | 23.9 | 3546.226 | 35.4 | 5372.853 | 42.1 | 8458.233 | 38.2 | 13671.611 |

| 65–69 | 25.9 | 2935.649 | 38.7 | 4436.133 | 47.3 | 6989.765 | 42.6 | 11683.620 |

| 70–74 | 28.0 | 2333.696 | 42.3 | 3326.293 | 53.2 | 5546.874 | 47.4 | 9193.002 |

| 75–80 | 30.4 | 1713.440 | 46.2 | 2078.889 | 59.8 | 3809.200 | 52.9 | 7714.551 |

| 80+ | 35.7 | 1462.513 | 55.1 | 1997.851 | 75.7 | 3327.737 | 65.4 | 7132.029 |

| Total 20+ (95% CI) | 19.1 (13.9–25.5) | 54615.730 | 24.3 (23.3–31.6) | 92324.390 | 25.9 (23.5–34.0) | 130170.401 | 25.3 (24.2–39.7) | 216828.010 |

x = mid-point of UN population 5-year age group.

Table 9. Estimated hypertension prevalence rates and cases in Africa among women (estimates derived from epidemiological model and UN population demographics).

| Age (years) | 1990 | 2000 | 2010 | 2030 | ||||

| Prevalence (%) = 7.631e0.0195x | Hypertension cases (000) | Prevalence (%) = 14.879e0.0115x | Hypertension cases (000) | Prevalence (%) = 7.6974e0.0279x | Hypertension cases (000) | Prevalence (%) = 8.7533e0.0237x | Hypertension cases (000) | |

| 20–24 | 11.7 | 3253.603 | 19.2 | 7188.909 | 14.2 | 6879.980 | 14.7 | 11003.651 |

| 25–29 | 12.9 | 3018.326 | 20.3 | 6265.350 | 16.3 | 6839.885 | 16.6 | 10705.340 |

| 30–34 | 14.2 | 2791.264 | 21.5 | 5463.243 | 18.8 | 6477.360 | 18.7 | 10444.901 |

| 35–39 | 15.7 | 2548.505 | 22.8 | 4870.534 | 21.6 | 5970.342 | 21.0 | 10247.020 |

| 40–44 | 17.3 | 2320.801 | 24.1 | 4347.172 | 24.8 | 5617.575 | 23.7 | 10144.220 |

| 45–49 | 19.1 | 2108.716 | 25.5 | 3814.806 | 28.7 | 5480.796 | 26.7 | 9787.847 |

| 50–54 | 21.1 | 1978.743 | 27.1 | 3309.921 | 32.8 | 5355.558 | 30.0 | 8847.015 |

| 55–59 | 23.2 | 1800.967 | 28.7 | 2818.021 | 37.8 | 5053.976 | 33.8 | 7864.990 |

| 60–64 | 25.6 | 1593.129 | 30.4 | 2429.126 | 43.4 | 4600.255 | 38.0 | 7056.223 |

| 65–69 | 28.2 | 1289.237 | 32.2 | 1960.988 | 49.9 | 3955.928 | 42.8 | 6247.986 |

| 70–74 | 31.1 | 976.8551 | 34.1 | 1457.391 | 57.4 | 3280.345 | 48.2 | 5124.622 |

| 75–80 | 34.3 | 630.250 | 36.1 | 906.116 | 65.9 | 2970.846 | 54.3 | 3631.026 |

| 80+ | 41.6 | 519.756 | 40.5 | 707.961 | 87.2 | 2887.797 | 68.8 | 3609.290 |

| Total 20+ years (95% CI) | 17.1 (13.4–27.0) | 24830.150 | 23.6 (21.5–33.3) | 45539.541 | 25.7 (21.7–35.4) | 65370.642 | 24.3 (22.4–38.9) | 104714.131 |

x = mid-point of UN population 5-year age group.

Figure 2. Epidemiological model showing distribution of hypertension prevalence according to age in both sexes, with size of bubble corresponding to respective sample size (A: 1990, B: 2000, C: 2010).

Figure 5. Epidemiological model showing distribution of hypertension prevalence according to age (projections for 2030), with size of bubble corresponding to respective sample size (A: both sexes, B: men, C: women).

Figure 3. Epidemiological model showing distribution of hypertension prevalence according to age among men, with size of bubble corresponding to respective sample size (A: 1990, B: 2000, C: 2010).

Figure 4. Epidemiological model showing distribution of hypertension prevalence according to age among women, with size of bubble corresponding to respective sample size (A: 1990, B: 2000, C: 2010).

Table 8. Estimated hypertension prevalence rates and cases in Africa among men (estimates derived from epidemiological model and UN population demographics).

| Age (years) | 1990 | 2000 | 2010 | 2030 | ||||

| Prevalence (%) = 10.505e0.0175x | Hypertension cases (000) | Prevalence (%) = 17.771e0.0088x | Hypertension cases (000) | Prevalence (%) = 10.334e0.0223x | Hypertension cases (000) | Prevalence (%) = 11.966e0.0183x | Hypertension cases (000) | |

| 20–24 | 15.4 | 4287.483 | 21.6 | 8141.867 | 16.9 | 8241.670 | 17.9 | 13606.260 |

| 25–29 | 16.9 | 3901.526 | 22.5 | 6946.029 | 18.9 | 7934.829 | 19.6 | 12816.871 |

| 30–34 | 18.4 | 3542.458 | 23.6 | 5932.465 | 21.1 | 7345.081 | 21.5 | 16039.680 |

| 35–39 | 20.1 | 3187.968 | 24.6 | 5185.153 | 23.6 | 6596.039 | 23.6 | 11574.670 |

| 40–44 | 21.9 | 2865.689 | 25.7 | 4513.438 | 26.4 | 5943.763 | 25.8 | 11090.801 |

| 45–49 | 23.9 | 2535.072 | 26.8 | 3859.029 | 29.5 | 5490.843 | 28.3 | 10275.230 |

| 50–54 | 26.1 | 2303.794 | 28.1 | 3261.431 | 32.9 | 5063.796 | 30.9 | 8962.983 |

| 55–59 | 28.5 | 2061.997 | 29.3 | 2667.812 | 36.8 | 4529.248 | 34.0 | 7618.278 |

| 60–64 | 31.1 | 1755.050 | 30.7 | 2197.312 | 41.2 | 3918.656 | 37.2 | 6406.076 |

| 65–69 | 33.9 | 1365.244 | 32.0 | 1718.733 | 46.0 | 3154.577 | 40.8 | 5243.806 |

| 70–74 | 37.0 | 978.408 | 33.5 | 1201.287 | 51.5 | 2424.530 | 44.7 | 3917.635 |

| 75–80 | 40.4 | 589.023 | 34.9 | 695.730 | 57.5 | 2238.964 | 48.9 | 2538.670 |

| 80+ | 48.2 | 411.868 | 38.2 | 464.571 | 71.9 | 1917.733 | 58.8 | 2022.895 |

| Total 20+ (95% CI) | 21.2 (16.5–29.6) | 29785.580 | 25.1 (22.9–31.0) | 46784.860 | 26.1 (23.6–33.6) | 64799.730 | 26.4 (24.5–41.1) | 112114.210 |

x = mid-point of UN population 5-year age group.

Discussion

This review provides an improved continent-wide estimate of the prevalence and awareness rates of hypertension in Africa using epidemiological modelling adjusted for age and sample size of the population. Having included studies conducted across various parts of Africa, the estimates may provide a close representation of the prevalence and the number of cases of hypertension in the continent.

From all studies, we estimated weighted mean systolic and diastolic blood pressures of 129.6 mm Hg and 78.0 mm Hg, respectively, with an overall mean age of 47.4 years. Our estimate is comparable with the estimates reported by Danaei and colleagues on the global trends of systolic blood pressure, with an overall mean SBP in SSA ranging 129.2–132.7 mm Hg and 132.6–134.8 mm Hg among men and women, respectively, between 1981 and 2008 [29]. This study further supports our finding of a high prevalence of hypertension in Africa, with the highest value of SBP globally estimated in SSA (along with central and eastern Europe) [29].

Across selected studies, higher prevalence rates of hypertension were reported with increasing age of subjects. This is underpinned by previous research findings where increasing age is associated with significant increase in the prevalence of hypertension, especially in people aged ≥60 years [12], [21]. For example, a higher prevalence of hypertension was reported in Northern Africa with a pooled prevalence of 33.3% compared to a prevalence of 27.8% in SSA. This could be partly explained by age difference, with a mean age of 54.3 years in Northern Africa, compared to 46.4 years in SSA. In the 2009 hospital-based Epidemiological Trial of Hypertension in North Africa (ETHNA), a high prevalence (45.4%, mean age 49.2 years) was also reported for Northern Africa [30]; this further supports findings of this study.

A higher prevalence of hypertension was noted among urban dwellers from the pooled estimates mainly in 1990 (urban 17.2%, rural 11.1%), while the prevalence was virtually the same in years 2000 and 2010. The narrowing of prevalence gaps between urban and rural dwellers in years 2000 and 2010 could be due to a possible reverse rural-urban migration, which has been reported when urban dwellers fail to cope with the economic challenges and vulnerabilities associated with urban life, and may prefer to return to natural resource-rich rural settlements [31]. In addition, there are reports that even in rural settings, the apparent remote and traditional styles do not seem to protect them again, as more of these rural settings are gradually becoming semi-urbanized [3]. Opie and colleagues also argued that many site-specific hypertension prevalence estimates in Africa may not truly reflect the burden in these settings, as there are still doubts on the proportion of Africans that truly reside in rural settings [32].

Meanwhile, an increasing, yet low, awareness rate of hypertension in Africa was reported, with pooled weighted awareness rate of 16.9% in 1990, 29.2% in 2000 and 33.7% in 2010. This estimate, to the best knowledge of our knowledge, remains the first weighted continent-wide awareness rate of hypertension reported in Africa, and thus forms an important finding of this study. The low awareness rate reported may still reflect a poor response to management of hypertension in the continent [33]. Kayima et al. corroborates this, reporting a very low awareness rate of hypertension ranging between 8% and 10% in Africa in the early 2000s [8].

In this review, the general sex distribution showed that the prevalence and cases of hypertension were higher among men than women. This is also in line with many reports in Africa [3], [8].This may be because the overall mean age from all selected studies was 47.4 years, which is just about a reported mean menopause age of 49.4 years among African women [34], and there is established evidence of a steeper blood pressure rise in men than women before the age of menopause [35]. We further estimated that there was a drop in hypertension prevalence among women between 2010 and 2030; Danaei and colleagues reported similar findings between 1981 and 2008, where, in contrast to a predominant rise in mean SBP among men, the mean SBP among women increased only in two countries globally between 1981 and 2008 [29]. Our estimate may therefore just be reflective of a continuation in this trend. Still, from the modelling, over 54.6 million cases of hypertension were estimated in 1990 (19.1%), 92.3 million cases in 2000 (24.3%), 130.2 million cases in 2010 (25.9%), and a projected increase to 216.8 million cases of hypertension by 2030 (25.3%). These estimates are higher than the 20 million reported by WHO African regional office (AFRO) in 2005 [36]. The WHO AFRO estimate was based on ≥160/95 mm Hg and this is probably the reason for the low hypertension cases reported. However, reports show that this figure has often been quoted in many official documents as the number of hypertension cases in Africa [4]. Meanwhile, Twagirumukiza et al. estimated about 75 million cases (16.2%) of hypertension among people aged ≥15 years in SSA in 2008, and projected to increase to 125.5 million cases (17.4%) in 2025 ( Table 10 ) [15]. These figures are relatively low compared to the current estimates. It is understandable that these estimates were for SSA and that the mean age was low (40 years), they may yet not reflect the true burden of hypertension in the continent, as their review and analysis mainly included studies from 11 countries in Africa. In addition, another reviewer also noted these concerns, and agreed the estimates were very low compared to recent prevalence rates reported in Africa, and may be erroneously interpreted that the burden of hypertension in the continent is low [37]. However, Kearney et al. reported higher hypertension estimates, with about 79.8 million hypertension cases (27.6%) estimated among people aged ≥20 years in 2000 and projected to reach about 150.7 million cases (27.7%) in 2025 [6]. These prevalence rates are comparable with the current estimates, but the difference in the number of hypertension cases may be due to the fact that demographic changes as reported by the United Nations population projections were considered. Kearney et al. also reported a minimal change in hypertension prevalence rates between 2000 and 2025 (27.6% versus 27.7%) [6], which is also comparable with the current estimates for 2000 and 2030 (24.3% versus 25.3%) ( Table 10 ). This may be due to a potentially better public health response to the overall management of hypertension in many African countries.

Table 10. Comparable estimates of hypertension prevalence rates from selected studies.

| Current Study* | Kearney et al.* [6] | Twagirumukiza et al.** [15] | |||||

| 2000 | 2010 | 2030 | 2000 | 2025 | 2008 | 2025 | |

| Prevalence rate (%) | 24.3 | 25.9 | 25.3 | 27.6 | 27.7 | 16.2 | 17.4 |

*20years (all Africa),

**15+years (sub-Saharan Africa).

Study limitations

The study aims to provide an improved continent-wide estimate of hypertension in Africa using current definitions (cut off “≥140/90 mm Hg”). However, the study has some important limitations. First, the modelling was age-dependent, we understand there are other important social and health determinants that could have resulted in varying estimates if considered, including, but not limited to the overall population characteristics, socio-economic factors and general living conditions [38]. In addition, the overall mean age was 47.4 years, which could also have resulted in a lower prevalence estimate, as research evidences show significant increase in hypertension prevalence in people aged ≥60 years [21]. Second, all studies included in our modelling were based on the blood pressure cut off “≥140/90 mm Hg”; notwithstanding, some studies have varying designs and blood pressure measuring protocols, which could have affected the quality of the current estimates. Moreover, while we ensured all studies that were graded as high and moderate quality were included in the quantitative analysis, some low quality studies were also included in the quantitative analysis on the basis of good study designs, which could potentially affect our overall estimates (See Box S1, Table S1 and Table S2 in File S1).

Third, not all studies reported age- and sex- specific estimates, including urban or rural site-specific estimates, as an epidemiology of the prevalence of hypertension in these sub-groups could have been further helpful. Furthermore, the incompleteness of data across many studies prevented us from providing estimates on the control and treatment of hypertension in Africa. We still hope that providing a continent-wide estimate of the awareness rate of hypertension may further give a general view of the public health response to the disease in the continent. However, we extracted data from 92 studies conducted in 31 African countries (having overall sample size of 197734), and with a consideration of the United Nations population demographics in the epidemiological modelling. The current estimates may therefore provide fair representation of the overall African population and better reflect the prevalence and number of cases of hypertension in the continent.

Challenges and public health response to hypertension in Africa

Recent reports show that the World Heart Federation, supported by the Pan African Society of Cardiology (PASCAR), has been actively building capacities across Africa to address the rising burden of hypertension and other cardiovascular diseases in the continent [39]. However, collaborations and response within Africa remains poor, as hypertension still ranks low among health priorities, owing to competition for the limited resources from a co-existing high burden of infectious diseases [5]. Moreover, in countries with some levels of care for hypertension, the standards of health service delivery is poor [3]. Many cases of hypertension are detected late, treatments rarely follow standard guidelines, and the costs of medications are generally high [35]. Besides, health care seeking behaviour has also been affected, with people often preferring low-cost substandard health facilities [40]. This is particularly a problem in rural settings where the prevalence of hypertension has been reported to be on a gradual increase [8]. Further reports show that even with a relatively lower prevalence of hypertension among rural dwellers, the detection and overall management are poor in comparison to urban dwellers [3]. Additionally, many African countries are yet to implement population-wide control measures to address risk factors for hypertension [41], even with confirmed reports of high salts and fats consumption in the region and evidence showing cost-effectiveness of interventions targeting this [42], [43]. The WHO now recommends country-specific initiatives and legislation concerning food labelling and products formulation, including sodium and saturated fats content in processed foods [2], [39].

Conclusions

This study suggests a high prevalence of hypertension in Africa, and the awareness of the disease, though increasing, still remains low. Hypertension deserves to be on the health priority lists of African nations, and problems with funding may possibly be reduced by partnering with leading international bodies for cardiovascular diseases. Essentially, policy makers and stakeholders in the health sector need to institute nationwide population-based strategies towards creating awareness on hypertension and educating people on the main risk factors such as smoking, harmful use of alcohol, sedentary lifestyles and unhealthy diets. It is hoped that the findings of this review may prompt appropriate policy response at country level towards improved detection, control and overall management of hypertension in Africa.

Supporting Information

PRISMA Checklist.

(DOC)

Box S1, Brief details of quality criteria of retained studies on hypertension in Africa. (This is a description of how studies were graded and assessed). Table S1, Quality assessment and grading of retained hypertension studies in Africa. (This shows the grading of each study). Table S2. Overall study characteristics with site identification numbers. (This shows all retained study sites with identification numbers used for grading)

(DOCX)

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank Jennifer Falconer and ‘Funke Davies-Adeloye for proof-reading the manuscript.

Funding Statement

The authors have no support or funding to report.

References

- 1. Lawes CMM, Vander Hoorn S, Law MR, Elliott P, MacMahon S, et al. (2006) Blood pressure and the global burden of disease 2000. Part 1: Estimates of blood pressure levels. Journal of Hypertension 24 3: 413–422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.World Health Organization (2013) A global brief on Hypertension: silent killer, global public health crises (World Health Day 2013). Geneva: WHO. [Google Scholar]

- 3. Opie LH, Seedat YK (2005) Hypertension in sub-Saharan African populations. Circulation 112: 3562–3568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.WHO Regional Office for Africa (2006) The health of the people: the African regional health report (2006). Geneva: WHO. [Google Scholar]

- 5. Beaglehole R, Bonita R, Alleyne G, Horton R, Li L, et al. (2011) UN High-Level Meeting on Non-Communicable Diseases: addressing four questions. Lancet 378: 449–455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Kearney PM, Whelton M, Reynolds K, Muntner P, Whelton PK, et al. (2005) Global burden of hypertension: analysis of worldwide data. Lancet 365: 217–223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. de-Graft Aikins A, Unwin N, Agyemang C, Allotey P, Campbell C, et al. (2010) Tackling Africa's chronic disease burden: From the local to the global. Globalization and Health 6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Kayima J, Wanyenze RK, Katamba A, Leontsini E, Nuwaha F (2013) Hypertension awareness, treatment and control in Africa: a systematic review. BMC Cardiovascular Disorders 13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. MacMahon S, Alderman MH, Lindholm LH, Liu L, Sanchez RA, et al. (2008) Blood-pressure-related disease is a global health priority. Lancet 371: 1481–1483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Mohan V, Seedat YK, Pradeepa R (2013) The rising burden of diabetes and hypertension in southeast Asian and African regions: Need for effective strategies for prevention and control in primary health care settings. International Journal of Hypertension 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Perkovic V, Huxley R, Wu Y, Prabhakaran D, MacMahon S (2007) The burden of blood pressure-related disease: a neglected priority for global health. Hypertension 50: 991–997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Addo J, Smeeth L, Leon DA (2007) Hypertension in sub-saharan Africa: a systematic review. Hypertension 50: 1012–1018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.World Health Organization (2011) Global status report on noncommunicable diseases 2010. Geneva: WHO. [Google Scholar]

- 14. Kengne AP, Ntyintyane LM, Mayosi BM (2012) A systematic overview of prospective cohort studies of cardiovascular disease in sub-Saharan Africa. Cardiovascular Journal of Africa 23: 103–112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Twagirumukiza M, De Bacquer D, Kips JG, de Backer G, Stichele RV, et al. (2011) Current and projected prevalence of arterial hypertension in sub-Saharan Africa by sex, age and habitat: an estimate from population studies. Journal of Hypertension 29: 1243–1252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.World Bank (2012) World bank list of economies (July 2012). Washington DC, USA: World Bank. [Google Scholar]

- 17.U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (1997) The Sixth Report of the Joint National Committee on Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Pressure (JNC 6). Wahington DC: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. [Google Scholar]

- 18. Chobanian AV, Akris GL, Black HR, Cushman WC, GReen LA, et al. (2003) The Seventh Report of the Joint National Committee on Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Pressure (JNC 7). JAMA 289: 2560–2572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Whitworth JA (2003) World Health Organization (WHO)/International Society of Hypertension (ISH) statement on management of hypertension. J Hypertens 21: 1983–1992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Balshem H, Helfand M, Schunemann HJ, Oxman AD, Kunz R, et al. (2011) GRADE guidelines: 3. Rating the quality of evidence. J Clin Epidemiol 64: 401–406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Anderson GH (1999) Effect of age on hypertension: analysis of over 4,800 referred hypertensive patients. Saudi J Kidney Dis Transpl 10: 286–297. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.United Nations (2013) World Population Prospects: The 2012 Revision. New York City: United Nations. [Google Scholar]

- 23. Peltzer K, Phaswana-Mafuya N (2013) Hypertension and associated factors in older adults in South Africa. Cardiovascular Journal of Africa 24 3: 66–71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Dewhurst MJ, Dewhurst F, Gray WK, Chaote P, Orega GP, et al. (2013) The high prevalence of hypertension in rural-dwelling Tanzanian older adults and the disparity between detection, treatment and control: A rule of sixths? Journal of Human Hypertension 27 6: 374–380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Laouani Kechrid C, Hmouda H, Ben Naceur MH, Ghannem H, Toumi S, et al. (2004) [High blood presure for people aged more than 60 years in the distrct of Sousse]. Tunisie Medicale 82: 1001–1005. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Macia E, Duboz P, Gueye L (2012) Prevalence, awareness, treatment and control of hypertension among adults 50 years and older in Dakar, Senegal. Cardiovascular Journal of Africa 23: 265–269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Ahmed ME (1990) Blood pressure in a multiracial urban Sudanese community. Journal of Human Hypertension 4: 621–624. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Giday A, Tadesse B (2011) Prevalence and determinants of hypertension in rural and urban areas of southern Ethiopia. Ethiopian Medical Journal 49: 139–147. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Danaei G, Finucane MM, Lin JK, Singh GM, Paciorek CJ, et al. (2011) National, regional, and global trends in systolic blood pressure since 1980: systematic analysis of health examination surveys and epidemiological studies with 786 country-years and 5·4 million participants. Lancet 377: 568–577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Nejjari C, Arharbi M, Chentir M-T, Boujnah R, Kemmou O, et al. (2013) Epidemiological Trial of Hypertension in North Africa (ETHNA): an international multicentre study in Algeria, Morocco and Tunisia. Journal of Hypertension 31: 49–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Institute for Security Studies (2010) Reverse Rural-urban Migrations: An Indication of Emerging Patterns in Africa? Pretoria, South Africa: ISS. [Google Scholar]

- 32. Opie LH, Mayosi BM (2005) Cardiovascular disease in sub-Saharan Africa. Circulation 112: 3536–3540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Seedat YK, Rosenthal T (2006) Meeting the challenges of hypertension in sub-Saharan Africa. Cardiovascular Journal of South Africa 17 2: 47–48. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Ozumba BC, Obi SN, Obikili E, Waboso P (2004) Age, symptoms and perception of menopause among Nigerian women. J Obstet Gynecol Ind 54: 575–578. [Google Scholar]

- 35. Hajar I, Kotchen JM, Kotchen TA (2006) Hypertension: trends in prevalence, incidence, and control. Annu Rev Public Health 27: 465–490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.WHO AFRO (2005) Report of Regional Director: Cardiovascular diseases in the African region: current situation and perpectives; 2005 17 June 2005; Maputo, Mozambique. Thw WHO Regional Office for Africa.

- 37. Poulter NR (2011) Current and projected prevalence of arterial hypertension in sub-Saharan Africa by sex, age and habitat: An estimate from population studies. Journal of Hypertension 29 7: 1281–1282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Negin J, Cumming R, de Ramirez SS, Abimbola S, Sachs SE (2011) Risk factors for non-communicable diseases among older adults in rural Africa. Tropical Medicine and International Health 16 5: 640–646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.World Heart Federation (2008) Africa: The burden of CVD and Hypertension and the World Heart Federation involvement. Geneva, Switzerland: WHF. [Google Scholar]

- 40. Suhrcke M, Boluarte TA, Niessen L (2012) A systematic review of economic evaluations of interventions to tackle cardiovascular disease in low- and middle-income countries. BMC Public Health 12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. van der Sande MA, Coleman RL, Schim van der Loeff MF, McAdam KP, Nyan OA, et al. (2001) A template for improved prevention and control of cardiovascular disease in sub-Saharan Africa. Health Policy & Planning 16: 345–350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Mezue K (2013) The increasing burden of hypertesnsion in Nigeria- can dietary salt reduction strategy change the trend? Perspect Public Health Epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Gaziano TA, Steyn K, Cohen DJ, Weinstein MC, Opie LH (2005) Cost-effectiveness analysis of hypertension guidelines in South Africa: absolute risk versus blood pressure level. Circulation 112: 3569–3576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Cooper R, Rotimi C, Ataman S, McGee D, Osotimehin B, et al. (1997) The prevalence of hypertension in seven populations of west African origin. American Journal of Public Health 87: 160–168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Cruickshank JK, Mbanya JC, Wilks R, Balkau B, Forrester T, et al. (2001) Hypertension in four African-origin populations: current ‘Rule of Halves’, quality of blood pressure control and attributable risk of cardiovascular disease. Journal of Hypertension 19: 41–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Fezeu L, Kengne AP, Balkau B, Awah PK, Mbanya JC (2010) Ten-year change in blood pressure levels and prevalence of hypertension in urban and rural Cameroon. Journal of Epidemiology & Community Health 64: 360–365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Kamadjeu RM, Edwards R, Atanga JS, Unwin N, Kiawi EC, et al. (2006) Prevalence, awareness and management of hypertension in Cameroon: Findings of the 2003 Cameroon Burden of Diabetes Baseline Survey [3]. Journal of Human Hypertension 20 1: 91–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Dionadji M, Boy B, Mouanodji M, Batakao G (2010) Prevalence of diabetes mellitus on rural area in Chad. [French]. Revue Medecine Tropicale 70: 414–415. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Katchunga PB, M'Buyamba-Kayamba J-R, Masumbuko BE, Lemogoum D, Kashongwe ZM, et al. (2011) [Hypertension in the adult Congolese population of Southern Kivu: Results of the Vitaraa Study]. Presse Medicale 40: e315–323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. M'Buyamba-Kabangu JR, Fagard R, Lijnen P, Staessen J, Ditu MS, et al. (1986) Epidemiological study of blood pressure and hypertension in a sample of urban Bantu of Zaire. Journal of Hypertension 4: 485–491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. de Ramirez SS, Enquobahrie DA, Nyadzi G, Mjungu D, Magombo F, et al. (2010) Prevalence and correlates of hypertension: a cross-sectional study among rural populations in sub-Saharan Africa. Journal of Human Hypertension 24: 786–795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Mufunda J, Mebrahtu G, Usman A, Nyarango P, Kosia A, et al. (2006) The prevalence of hypertension and its relationship with obesity: results from a national blood pressure survey in Eritrea. Journal of Human Hypertension 20: 59–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Awoke A, Awoke T, Alemu S, Megabiaw B (2012) Prevalence and associated factors of hypertension among adults in Gondar, Northwest Ethiopia: a community based cross-sectional study. BMC Cardiovascular Disorders 12: 113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Nshisso LD, Reese A, Gelaye B, Lemma S, Berhane Y, et al. (2012) Prevalence of hypertension and diabetes among Ethiopian adults. Diabetes & Metabolic Syndrome 6: 36–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Tesfaye F, Byass P, Wall S (2009) Populationbased prevalence of high blood pressure among adults in Addis Ababa: Uncovering a silent epidemic. BMC Cardiovascular Disorders 9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Tran A, Gelaye B, Girma B, Lemma S, Berhane Y, et al. (2011) Prevalence of metabolic syndrome among working adults in Ethiopia. International Journal of Hypertension 2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Hendriks ME, Wit FWNM, Roos MTL, Brewster LM, Akande TM, et al. (2012) Hypertension in sub-Saharan Africa: cross-sectional surveys in four rural and urban communities. PLoS ONE [Electronic Resource] 7: e32638. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Mathenge W, Foster A, Kuper H (2010) Urbanization, ethnicity and cardiovascular risk in a population in transition in Nakuru, Kenya: a population-based survey. BMC Public Health 10: 569. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Van De Vijver SJM, Oti SO, Agyemang C, Gomez GB, Kyobutungi C (2013) Prevalence, awareness, treatment and control of hypertension among slum dwellers in Nairobi, Kenya. Journal of Hypertension 31 5: 1018–1024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Bovet P, Shamlaye C, Gabriel A, Riesen W, Paccaud F (2006) Prevalence of cardiovascular risk factors in a middle-income country and estimated cost of a treatment strategy. BMC Public Health 6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Bovet P, Ross AG, Gervasoni J-P, Mkamba M, Mtasiwa DM, et al. (2002) Distribution of blood pressure, body mass index and smoking habits in the urban population of Dar es Salaam, Tanzania, and associations with socioeconomic status. International Journal of Epidemiology 31: 240–247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Edwards R, Unwin N, Mugusi F, Whiting D, Rashid S, et al. (2000) Hypertension prevalence and care in an urban and rural area of Tanzania. Journal of Hypertension 18: 145–152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Maher D, Waswa L, Baisley K, Karabarinde A, Unwin N (2011) Epidemiology of hypertension in low-income countries: a cross-sectional population-based survey in rural Uganda. Journal of Hypertension 29: 1061–1068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Mayega RW, Makumbi F, Rutebemberwa E, Peterson S, Ostenson C-G, et al. (2012) Modifiable socio-behavioural factors associated with overweight and hypertension among persons aged 35 to 60 years in eastern Uganda. PLoS ONE [Electronic Resource] 7: e47632. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Musinguzi G, Nuwaha F (2013) Prevalence, awareness and control of hypertension in Uganda. PLoS ONE 8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Wamala JF, Karyabakabo Z, Ndungutse D, Guwatudde D (2009) Prevalence factors associated with hypertension in Rukungiri district, Uganda–a community-based study. African Health Sciences 9: 153–160. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Hamida F, Atif ML, Temmar M, Chibane A, Bezzaoucha A, et al. (2013) Prevalence of hypertension in El-Menia oasis, Algeria, and metabolic characteristics in population. [French]. Annales de Cardiologie et d'Angeiologie 62 3: 172–178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Latifa BH, Kaouel M (2007) [Cardiovascular risk factors in Tlemcen (Algeria)]. Sante 17: 153–158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Temmar M, Labat C, Benkhedda S, Charifi M, Thomas F, et al. (2007) Prevalence and determinants of hypertension in the Algerian Sahara. Journal of Hypertension 25: 2218–2226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Ibrahim MM, Rizk H, Appel LJ, El Aroussy W, Helmy S, et al. (1995) Hypertension prevalence, awareness, treatment, and control in Egypt: Results from the Egyptian National Hypertension Project (NHP). Hypertension 26 6 I: 886–890. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Mohamed MR, Shafek M, El Damaty S, Seoudi S (2000) Hypertension control indicators among rural population in Egypt. Journal of the Egyptian Public Health Association 75: 391–401. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Tazi MA, Abir-Khalil S, Chaouki N, Cherqaoui S, Lahmouz F, et al. (2003) Prevalence of the main cardiovascular risk factors in Morocco: results of a National Survey, 2000. Journal of Hypertension 21: 897–903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Allal-Elasmi M, Feki M, Zayani Y, Hsairi M, Haj Taieb S, et al. (2012) Prehypertension among adults in Great Tunis region (Tunisia): A population-based study. Pathologie Biologie 60: 174–179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Ben Romdhane H, Ben Ali S, Skhiri H, Traissac P, Bougatef S, et al. (2012) Hypertension among Tunisian adults: results of the TAHINA project. Hypertension Research - Clinical & Experimental 35: 341–347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Ben Romdhane H, Skhiri H, Bougatef S, Ennigrou S, Gharbi D, et al. (2005) [Hypertension prevalence, awareness, treatment and control: results from a community based survey]. Tunisie Medicale 83 Suppl 5: 41–46. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Ghannem H, Fredj AH (1997) Epidemiology of hypertension and other cardiovascular disease risk factors in the urban population of Soussa, Tunisia. Eastern Mediterranean Health Journal 3: 472–479. [Google Scholar]

- 77. Hammami S, Mehri S, Hajem S, Koubaa N, Frih MA, et al. (2011) Awareness, treatment and control of hypertension among the elderly living in their home in Tunisia. BMC Cardiovascular Disorders 11: 65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. Capingana DP, Magalhaes P, Silva ABT, Goncalves MAA, Baldo MP, et al. (2013) Prevalence of cardiovascular risk factors and socioeconomic level among public-sector workers in Angola. BMC Public Health 13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. Pires JE, Sebastiao YV, Langa AJ, Nery SV (2013) Hypertension in Northern Angola: prevalence, associated factors, awareness, treatment and control. BMC Public Health 13: 90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80. Mauny F, Viel JF, Roubaux F, Ratsimandresy R, Sellin B (2003) Blood pressure, body mass index and socio-economic status in the urban population of Antananarivo (Madagascar). Annals of Tropical Medicine and Parasitology 97 6: 645–654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81. Msyamboza KP, Kathyola D, Dzowela T, Bowie C (2012) The burden of hypertension and its risk factors in Malawi: Nationwide population-based STEPS survey. International Health 4 4: 246–252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82. Damasceno A, Azevedo A, Silva-Matos C, Prista A, Diogo D, et al. (2009) Hypertension prevalence, awareness, treatment, and control in mozambique: urban/rural gap during epidemiological transition. Hypertension 54: 77–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83. Alberts M, Urdal P, Steyn K, Stensvold I, Tverdal A, et al. (2005) Prevalence of cardiovascular diseases and associated risk factors in a rural black population of South Africa. European Journal of Cardiovascular Prevention & Rehabilitation 12: 347–354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84. Malaza A, Mossong J, Barnighausen T, Newell M-L (2012) Hypertension and obesity in adults living in a high HIV prevalence rural area in South Africa. PLoS ONE [Electronic Resource] 7: e47761. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85. Steyn K, Jooste PL, Fourie JM, Parry CD, Rossouw JE (1986) Hypertension in the coloured population of the Cape Peninsula. South African Medical Journal Suid-Afrikaanse Tydskrif Vir Geneeskunde 69: 165–169. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86. Steyn K, Fourie J, Lombard C, Katzenellenbogen J, Bourne L, et al. (1996) Hypertension in the black community of the Cape Peninsula, South Africa. East African Medical Journal 73: 758–763. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87. Steyn K, Levitt NS, Hoffman M, Marais AD, Fourie JM, et al. (2004) The global cardiovascular diseases risk pattern in a peri-urban working-class community in South Africa. The Mamre study. Ethnicity & Disease 14: 233–242. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88. Thorogood M, Connor M, Tollman S, Lewando Hundt G, Fowkes G, et al. (2007) A cross-sectional study of vascular risk factors in a rural South African population: data from the Southern African Stroke Prevention Initiative (SASPI). BMC Public Health 7: 326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89. Goma FM, Nzala SH, Babaniyi O, Songolo P, Zyaambo C, et al. (2011) Prevalence of hypertension and its correlates in Lusaka urban district of Zambia: A population based survey. International Archives of Medicine 4 1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90. Houinato DS, Gbary AR, Houehanou YC, Djrolo F, Amoussou M, et al. (2012) Prevalence of hypertension and associated risk factors in Benin. Revue d Epidemiologie et de Sante Publique 60: 95–102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91. Niakara A, Fournet F, Gary J, Harang M, Nebie LVA, et al. (2007) Hypertension, urbanization, social and spatial disparities: a cross-sectional population-based survey in a West African urban environment (Ouagadougou, Burkina Faso). Transactions of the Royal Society of Tropical Medicine & Hygiene 101: 1136–1142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92. van der Sande MA, Milligan PJ, Nyan OA, Rowley JT, Banya WA, et al. (2000) Blood pressure patterns and cardiovascular risk factors in rural and urban gambian communities. Journal of Human Hypertension 14: 489–496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93. Addo J, Amoah AGB, Koram KA (2006) The changing patterns of hypertension in Ghana: a study of four rural communities in the Ga District. Ethnicity & Disease 16: 894–899. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94. Agyemang C (2006) Rural and urban differences in blood pressure and hypertension in Ghana, West Africa. Public Health 120: 525–533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95. Burket BA (2006) Blood pressure survey in two communities in the Volta region, Ghana, West Africa. Ethnicity & Disease 16: 292–294. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96. Cappuccio FP, Micah FB, Emmett L, Kerry SM, Antwi S, et al. (2004) Prevalence, detection, management, and control of hypertension in Ashanti, West Africa. Hypertension 43: 1017–1022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97. Cook-Huynh M, Ansong D, Steckelberg RC, Boakye I, Seligman K, et al. (2012) Prevalence of hypertension and diabetes mellitus in adults from a rural community in Ghana. Ethnicity & Disease 22: 347–352. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98. Koopman JJE, van Bodegom D, Jukema JW, Westendorp RGJ (2012) Risk of cardiovascular disease in a traditional African population with a high infectious load: a population-based study. PLoS ONE [Electronic Resource] 7: e46855. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99. Williams EA, Keenan KE, Ansong D, Simpson LM, Boakye I, et al. (2013) The burden and correlates of hypertension in rural Ghana: A cross-sectional study. Diabetes and Metabolic Syndrome: Clinical Research and Reviews 7 3: 123–128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100. Balde MD, Balde NM, Kaba ML, Diallo I, Diallo MM, et al. (2006) [Hypertension: epidemiology and metabolic abnormalities in Foutah-Djallon in Guinea]. Mali Medical 21: 19–22. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101. N'Gouin-Claih AP, Donzo M, Barry AB, Diallo A, Kabine O, et al. (2003) [Prevalence of hypertension in Guinean rural areas]. Archives des Maladies du Coeur et des Vaisseaux 96: 763–767. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102. Giles WH, Pacque M, Greene BM, Taylor HR, Munoz B, et al. (1994) Prevalence of hypertension in rural west Africa. American Journal of the Medical Sciences 308: 271–275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103. Abegunde KA, Owoaje ET (2013) Health problems and associated risk factors in selected urban and rural elderly population groups of South-West Nigeria. Annals of African Medicine 12: 90–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104. Adedoyin RA, Mbada CE, Balogun MO, Martins T, Adebayo RA, et al. (2008) Prevalence and pattern of hypertension in a semiurban community in Nigeria. European Journal of Cardiovascular Prevention & Rehabilitation 15: 683–687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105. Adedoyin RA, Mbada CE, Ismaila SA, Awotidebe OT, Oyeyemi AL, et al. (2012) Prevalence of cardiovascular risk factors in a low income semi-Urban community in the north-east Nigeria. TAF Preventive Medicine Bulletin 11 4: 463–470. [Google Scholar]

- 106. Ahaneku GI, Osuji CU, Anisiuba BC, Ikeh VO, Oguejiofor OC, et al. (2011) Evaluation of blood pressure and indices of obesity in a typical rural community in eastern Nigeria. Annals of African Medicine 10: 120–126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107. Alikor CA, Emem-Chioma PC, Odia OJ (2013) Hypertension in a rural community in Rivers State, Niger Delta region of Nigeria: Prevalence and Risk Factors. Nigerian Health Journal 13: 18–25. [Google Scholar]

- 108. Amira CO, Sokunbi DOB, Sokunbi A (2012) The prevalence of obesity and its relationship with hypertension in an urban community: data from world kidney day screening programme. International Journal of Medicine and Biomedical Research 1: 104–110. [Google Scholar]

- 109. Amole IO, OlaOlorun AD, Odeigah LO, Adesina SA (2011) The prevalence of abdominal obesity and hypertension amongst adults in Ogbomoso, Nigeria. African Journal of Primary Health Care and Family Medicine 3. [Google Scholar]

- 110. Asekun-Olarinmoye EO, OAkinwusi P, Adebimpe WO, Isawumi MA, Hassan MB, et al. (2013) Prevalence of hypertension in the rural adult population of Osun State, southwestern Nigeria. International Journal of General Medicine 6: 317–322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111. Bunker CH, Ukoli FA, Nwankwo MU, Omene JA, Currier GW, et al. (1992) Factors associated with hypertension in Nigerian civil servants. Preventive Medicine 21: 710–722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112. Ejim EC, Okafor CI, Emehel A, Mbah AU, Onyia U, et al. (2011) Prevalence of cardiovascular risk factors in the middle-aged and elderly population of a nigerian rural community. Journal of Tropical Medicine [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113. Ekanem US, Opara DC, Akwaowo CD (2013) High blood pressure in a semi-urban community in south-south Nigeria: a community-based study. African Health Sciences 13: 56–61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114. Ekwunife OI, Udeogaranya PO, Nwatu IL (2010) Prevalence, awareness, treatment and control of hypertension in a Nigerian population. Health 2: 731–735. [Google Scholar]

- 115. Erhun WO, Olayiwola G, Agbani EO, Omotoso NS (2005) Prevalence of hypertension in a university community in South West Nigeria. African Journal of Biomedical Research 8: 15–19. [Google Scholar]

- 116. Isezuo SA, Sabir AA, Ohwovorilole AE, Fasanmade OA (2011) Prevalence, associated factors and relationship between prehypertension and hypertension: a study of two ethnic African populations in Northern Nigeria. Journal of Human Hypertension 25: 224–230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117. Mbah BO, Eme PE, Ezeji J (2013) Prevalence and Risk Factors of Hypertension Among Middle-Aged Adults in Ahiazu Mbaise Local Government Area, Imo State, Nigeria. International Journal of Basic & Applied Sciences 13: 26–30. [Google Scholar]