Abstract

In rabbit proximal tubular cells, ANG II type 2-receptor (AT2)-induced arachidonic acid release is PLA2 coupled and dependent of G protein βγ (Gβγ) subunits. Moreover, ANG II activates ERK1/2 and transactivates EGFR via a c-Src-dependent mechanism. Arachidonic acid has been shown to mimic this effect, at least in part, by an undetermined mechanism. In this study, we determined the effects of ANG II on fibronectin expression in cultured rabbit proximal tubule cells and elucidated the signaling pathways associated with such expression. We found that ANG II and transfection of Gβγ subunits directly increased fibronectin protein expression, and this increase was inhibited by overexpression of β-adrenergic receptor kinase (βARK)-ct or DN-Src. Moreover, ANG II-induced fibronectin protein expression was significantly abrogated by the AT2 receptor antagonist PD123319. In addition, inhibition of cystolic PLA2 diminished ANG II-induced fibronectin expression. Endogenous arachidonic acid mimicked ANG II-induced fibronectin expression. We also found that overexpression of Gβγ subunits induced c-Src, ERK1/2, and EGFR tyrosine phosphorylation, which can be inhibited by overexpression of βARK-ct or DN-Src. Gβγ also induced c-Src SH2 domain association with the EGFR. Supporting these findings, in rabbit proximal tubular epithelium, immunoblot analysis indicated that βγ expression was significant. Interestingly, arachidonic acid- and eicosatetraenoic acid-induced responses were preserved in the presence of βARK-ct. This is the first report demonstrating the regulation of EGFR, ERK1/2, c-Src, and fibronectin by Gβγ subunits in renal epithelial cells. Moreover, this work demonstrates a role for Gβγ heterotrimeric proteins in ANG II, but not arachidonic acid, signaling in renal epithelial cells.

Keywords: arachidonic acid; angiotensin II; c-Src, epidermal growth factor receptor transactivation; carboxyl terminus of β-adrenergic receptor kinase-1; mitogen-activated protein kinase; Gβγ

the signaling function of G proteins was once attributed only to the Gα subunit. However, it is now clear that G protein βγ (Gβγ) dimer subunits of the heterotrimeric G proteins directly couple to G protein-coupled receptors (GPCRs) and many structural diverse effectors to transmit signals from GPCRs to effectors. Indeed, Gβγ subunits have been implicated in GPCR-induced transactivation of tyrosine kinase receptors. Transactivation of tyrosine kinase receptors, such as EGFR, by GPCRs has been suggested to involve signaling linked to the GTP-binding Gβγ subunits to facilitate cross talk between these distinct receptor systems. In fact, the EGFR was recently identified as a signal transducer in response to activation of the Gαq-coupled ANG II receptor or Gαi-coupled lysophosphatidic acid (LPA) receptor in cultured aortic smooth muscle cells (47) and rat-1 fibroblasts (11). In COS-7 cells, the transiently expressed Gαi-coupled M2 muscarinic acetylcholine receptor and Gαq-coupled bombesin receptor were used to demonstrate that Gαi and Gαq cooperatively mediated GPCR-induced EGFR transactivation (10). Moreover, in rat-1 fibroblast and Cos 7 cells, dominant negative mutants of the EGFR were used to demonstrate that the EGFR is important for linking GPCR activation with the activation of MAPK/p44/42 MAPK (ERK1/2) (11, 29). In fact, in many cells, the EGFR kinase inhibitor AG1478 inhibited GPCR-mediated ERK1/2 activation (6, 13, 14, 29). It is now well documented that Gβγ subunits are also able to transmit signals to the effector molecules in renal epithelial cells (19, 30). This novel discovery has raised many interesting questions that need to be answered timely and clearly. For example, how are the Gβγ subunits activated, and are there any cooperative relationships between Gα and Gβγ subunits with respect to signal transduction in renal epithelia? We have found that within the kidney, the ANG II type 2B (AT2B) receptor follows a paradigm wherein Gβγ subunits mediate PLA2 activation, arachidonic acid release, and EGFR transactivation (19). Arachidonic acid has been documented to mimic this transactivation at least in part by an undetermined mechanism.

A growing body of data indicates that the Src family of protein tyrosine kinases (PTKs) functionally interacts with Gβγ subunits and a variety of nonreceptor and receptor PTKs, particularly the EGFR. For example, in smooth muscle cells, ANG II (AT1)-induced PLCγ, p21Ras, and ERK1/2 activation have been suggested to be mediated at least in part by c-Src since introduction of c-Src antiserum and dominant negative mutants blocked these effects (24, 35, 40). Of interest is the fact that no direct physical association has been documented between PLCγ and c-Src following ANG II activation in smooth muscle cells. It was observed that in cells deficient in the Src-related tyrosine kinase Lyn, ERK1/2 activation by the Gαq-coupled M1 muscarinic acetylcholine receptor was blocked, whereas the Gαi-coupled M2 muscarinic acetylcholine receptor was unaffected. In cells deficient in the Src-related tyrosine kinase Syk, both M1 and M2 muscarinic acetylcholine receptors failed to stimulate ERK1/2 activation (21, 48). In this context, Luttrell et al. (33, 34) have shown that in Cos 7 cells Gβγ subunits directly activate c-Src receptors and that c-Src activation mediates Ras-dependent activation of ERK1/2. In addition, we have recently observed that ANG II induces ERK1/2 activation and transactivates EGFR in primary cultures of rabbit proximal tubule cells via an ANG II (AT2)-induced activated c-Src and Src homology 2 (SH2) domain association with the EGFR (3). Although Gβγ seems to play an important role in both Gαi- and Gαq-mediated ERK1/2 activation in response to stimulation of GPCRs, the molecular mechanisms involved in regulating proximal tubule c-Src activation by ANG II and arachidonic remain largely unknown.

In the present study, we investigated whether arachidonic acid-induced fibronectin protein expression and c-Src, ERK1/2, and EGFR tyrosine phosphorylation are subject to G protein regulation. The data showed that stimulation of proximal tubule cells with Gβγ subunits resulted in significant fibronectin synthesis and ERK1/2 and EGFR tyrosine phosphorylation via the activation of c-Src and SH2 associations with the EGFR. In addition, both ANG II and arachidonic acid induced significant time-dependent increases in fibronectin protein expression in rabbit proximal tubule cells. Whereas ANG II appears to elicit its effects through coupling of Gβγ subunits, the mechanisms involved in the activation of the above cascade by arachidonic acid appear to be independent of Gβγ subunits. Thus a novel pathway has been identified wherein arachidonic acid induces c-Src-dependent transactivation of the EGFR, association of the EGFR with c-Src, and the sequential downstream activation of ERK1/2 and fibronectin synthesis independently of Gβγ signaling. In addition, these data demonstrate that Gβγ mediates ANG II-induced fibronectin expression and c-Src and ERK1/2 activation in a PLC- and PKC-independent manner and that c-Src acts sequentially upstream of EGFR in rabbit proximal tubule cells. Moreover, we present for the first time an alternative paradigm to Gβγ-induced transactivation of a kinase receptor, whereby Gβγ subunits can activate cystolic (c) PLA2 to increase the amount of arachidonic acid present, ultimately inducing fibronectin synthesis and c-Src, EGFR, and ERK1/2 activity. Thus these observations are important, as they have established an alternative signal transduction pathway between GPCRs and the activation of c-Src, EGFR, and ERK1/2, mediated by arachidonic acid, a fatty acid released on activation of a variety of signaling mediators (PLA2, PLC, PLD, etc.). In addition, the involvement of Gβγ in this AT2 signaling paradigm is novel with respect to ANG II receptor subtypes for this and other locations.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Materials.

Cell culture media, serum, cell culture supplements, and Lipofectamine 2000 transfection reagent were purchased from Invitrogen. Arachidonic acid was purchased from MP Biomedical. ANG II, eicosatetraenoic acid (ETYA), losartan, PD123319, and GF 109203X hydrochloride were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich. [3H]arachidonic acid was purchased from American Radiolabeled Chemicals. Antibodies against EGFR, phosphotyrosine (PY20), sheep IgG horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-conjugated goat anti-mouse, rabbit IgG, and U73122 were purchased from Calbiochem. Antibodies against phospho-c-Src (Tyr416), phospho-cPLA2 (Ser505), phospho-p42MAPK (Try202)/p44MAPK (Try204; ERK1/2), p42MAPK (Try202)/p44MAPK (Try204), cPLA2, and c-Src were purchased from Cell Signaling Technology. Antibodies against fibronectin, β-actin, Gβ1, Gβ2, Gβ3, Gβ4, and Gγ2 were purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology. Arachidonyl trifluoromethyl ketone (AACOCF3), methyl arachidonyl fluorophosphonate (MAFP), oleyloxyethyl phosphorylcholine (OPC), and bromoenol lactone (BEL) were purchased from Cayman Chemical. All other chemicals were of best available quality, usually analytic grade.

Cell culture and reagents.

All procedures were performed according to protocols approved by the Institutional Committee for Use and Care of Laboratory Animals. Primary culture of proximal tubule cells was isolated from male New Zealand White rabbits and cultured as described previously (2). Cells were maintained for 9–14 days in DMEM/F-12 medium (1:1) supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum (Invitrogen), 5 μg/ml insulin (Sigma), 5 μg/ml transferrin (Sigma), 0.5 μg/ml hydrocortisone (Sigma), 100 U/ml of penicillin, and 100 μg/ml streptomycin (Life Technology). Subconfluent monolayers of first-passage cells were employed for experiments. Cells were grown in 100-mm dishes (for preparation of immunoblots) and six-well plates (for arachidonic acid release assay).

Transfections.

Transfection was carried out by using Lipofectamine 2000 transfection reagent (Invitrogen) using 10 μg of plasmid DNA (e.g., 5 μg β1 plus 5 μg γ2) in 30 μl of transfection reagent/100-mm dish or six-well plate to rabbit proximal tubule cells at 75% confluence. The transfection mixture remained in the medium for 4 h. Afterward, cells were grown in standard growth medium for 20 h and subsequently serum restricted for 24 h. For mock-transfection, the pCMV5 vector (10 μg) without the cDNA inserts was employed.

c-Src glutathione-S-transferase-SH2 fusion protein pull-down assay.

pGEX vectors containing the cDNA sequences encoding the SH2 and SH3 domains of c-Src were retrieved from chicken c-Src cDNA plasmid by PCR. The sequence of both strands was verified by Cleveland Genomic LT, with ABI PRISM, model 377. A standard protocol (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech) was employed to prepare the glutathione-S-transferase (GST) fusion protein conjugated with glutathione-Sepharose 4B beads (Sigma). Twelve microliters of GST fusion proteins noncovalently coupled to Sepharose beads were incubated with 1 mg of cell lysates prepared in SDS/RIPA buffer for 2 h at 4°C. After binding, the sample was centrifuged for 30 s at 4°C and the Sepharose beads were washed three times with lysis buffer. Bound proteins were boiled in 25 μl Laemmli's sample buffer (2×) for 5 min and resolved by SDS-PAGE, transferred to polyvinylidene difluoride (PVDF) membranes, blocked in 5% nonfat dry milk in PBS-Tween 20 (0.1%) for 1 h at room temperature, and subsequently incubated with anti-EGFR sheep polyclonal antibody (1:1,000 dilution, Sigma) overnight at 4°C. The blot was washed three times in PBS-T (0.1% Tween 20) for 30 min each and immunoblotted with horseradish peroxidase-conjugated anti-sheep IgG (1:2,000 dilution, Calbiochem). The immunoreactive proteins were detected by enhanced chemiluminescence (ECL; Amersham Pharmacia Biotech). The exposed autoradiograph was analyzed by Un-Scan-It gel version 5.1 (Silk Scientific) to obtain densitometry data. Protein contents were determined by BCA assay (Pierce).

Arachidonic acid release assay.

Arachidonic acid release was determined as previously described (1). Briefly, cells grown on six-well plates to subconfluence were labeled with 0.5 μCi·ml−1·well−1 [3H]arachidonic acid (American Radiolabeled Chemicals) for 4 h before treatment. They were washed three times with DMEM containing 1 mg/ml fatty acid-free bovine serum albumin to remove free labels. After treatment of cells, the medium was removed and the released arachidonic acid was determined by scintillation counting. Each data point is the average from at least three wells repeated at least four times.

Immunoblotting.

After stimulation, cells were lysed in RIPA buffer, adjusted to an equal amount of protein (30 μg) and equal volume, boiled in 2× Laemmli's sample buffer, and protein extracts were separated by SDS-PAGE. The proteins were then transferred to a PVDF membrane by electroblotting at 300 mÅ for 1.5 h. After electrophoresis, nonspecific binding was blocked by incubation with 5% (wt/vol) nonfat milk in PBS/T (0.1% Tween 20) for 1 h and probed with designated antibodies. After 24-h incubation at 4°C, the membrane was washed three times with PBS-T and incubated for 1 h at room temperature with horseradish peroxidase-conjugated goat anti-mouse (Calbiochem) or goat anti-rabbit IgG (Calbiochem). After washing, blots were developed with an ECL. Intensities of immunoreactive protein bands were quantified using Un-Scan-It gel, version 5.1, to obtain densitometry data. Protein contents were determined by BCA assay (Pierce).

Coimmunoprecipitation analysis was performed using confluent rabbit proximal tubule cells treated with vehicle or stimulated with the agonist of interest, or transfected with empty vector (mock) or Gβ1γ2 subunits. After stimulation, cells were lysed in RIPA buffer, adjusted to an equal amount of protein (100–500 μg) and equal volume. A designated antibody (IgG) was added, and samples were incubated overnight at 4°C. Immune complexes were recovered by the addition of 100 μl of protein A/G PLUS-Agarose (Santa Cruz Biotechnology). Samples were incubated for 2 h with gentle agitation at 4°C. The immunoprecipitates were washed once with lysis buffer and twice with ice-cold PBS. The immunoprecipitated proteins were eluted with 50 μl 2× Laemmli's sample buffer (Santa Cruz Biotechnology), boiled for 5 min, subjected to SDS-PAGE, transferred to a PVDF membranes, probed with specific antibodies, and developed with ECL. The exposure autoradiograph was analyzed by Un-Scan-It gel, version 5.1, to obtain densitometry data. Protein contents were determined by BCA assay.

Drug treatments.

cPLA2 inhibitors AACOCF3 and MAFP, secretory (s) PLA2 inhibitor OPC, and Ca2+-independent (i) PLA2 inhibitor BEL (Cayman Chemical) were dissolved in ethanol at 10 mmol/l for stock and used as 10 μmol/l; PLC inhibitor U73122 (Calbiochem) and PKC inhibitor GF 109203X hydrochloride (Sigma) were prepared as 10 mmol/l stocks in DMSO and finally used as 1 and 10 μmol/l, respectively.

Statistical analysis.

Data expressed as means ± SE were analyzed with a one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by a Student-Newman-Keuls multiple comparison post-hoc test or with a two-tailed Student's t-test when appropriate. A value of P < 0.05 was considered significant.

RESULTS

Gβy subunits mediate ANG II-induced c-Src, EGFR, and ERK1/2 phosphorylation.

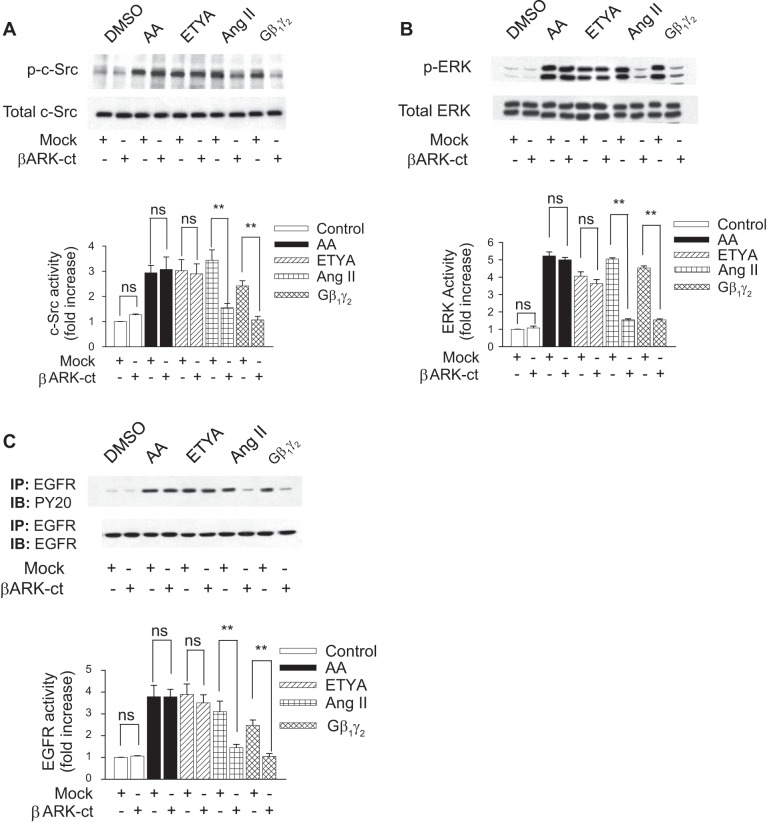

Our previous studies have shown that both ANG II and arachidonic acid induce EGFR, c-Src, and ERK1/2 phosphorylation in rabbit renal proximal tubules (3), effects which were readily abrogated by pretreatment with the Src family kinase inhibitor 3-(4-chlorophenyl)1-(1,1-dimethylethyl)-1H-pyrazolo[3,4-d]pyrimidin-4amine (PP2) or by transfection of rabbit proximal tubule cells with dominant-negative (DN) c-Src (DN-Src). Previous work by Haithcock and colleagues (19) indicates that Gβ1γ2 subunits enhance ANG II-dependent arachidonic acid release and that sequester of endogenous free Gβγ subunits, by the carboxyl terminus of the β-adrenergic receptor kinase 1 (βARK-ct), abrogates ANG II-induced arachidonic acid release in these same cells, but whether Gβ1γ2 subunits mediate arachidonic acid-induced EGFR, c-Src, and ERK1/2 phosphorylation is not known. Figure 1, A, B, and C, respectively, shows that the overexpression of Gβ1γ2 increased c-Src, ERK1/2, and EGFR activation by 2.41-, 4.53-, and 2.46-fold, respectively, compared with controls. Transfection of βARK-ct significantly reduced Gβ1γ2-induced c-Src, ERK1/2, and EGFR activation, indicating that both exogenous and endogenous Gβγ subunits could activate c-Src, ERK1/2, and EGFR. In addition, the transfection of βARK-ct significantly attenuated ANG II-induced c-Src (3.44–1.55-fold) (Fig. 1A), ERK1/2 (5.04–1.54-fold) (Fig. 1B), and EGFR phosphorylation (3.10–1.45-fold) (Fig. 1C), indicating endogenous Gβγ regulation of ANG II-induced c-Src, ERK1/2, and EGFR phosphorylation in rabbit renal proximal tubules. By contrast, arachidonic acid-induced c-Src, ERK1/2, and EGFR phosphorylation was unaffected in the presence of βARK-ct, confirming that arachidonic acid activates c-Src, ERK1/2, and EGFR independently of Gβγ subunits. Similar results were demonstrated with 5,8,11,14-ETYA, a nonmetabolized arachidonic acid analog. This suggests that the mechanism of action for arachidonic acid is different compared with that induced by ANG II and that endogenous Gβγ subunits might be a direct effector of c-Src, ERK1/2, and EGFR activation in rabbit proximal tubular cells.

Fig. 1.

Gβγ mediates ANG II-induced c-Src, ERK, and EGFR receptor (EGFR) activity. β-Adrenergic receptor kinase (βARK-ct) or empty vector (mock) plasmids were transfected into rabbit proximal tubule cells 24 h before assay. Proximal tubule cells were treated with 0.1% DMSO (vol/vol), arachidonic acid (AA; 15 μmol/l), eicosatetraenoic acid (ETYA; 15 μmol/l), or ANG II (1 μmol/l) for 5 min or with plasmids encoding β1 and γ2, (5 μg each) for 24 h. Extracts from cells were analyzed by Western blotting using anti-phospho-c-Src (Tyr416), anti-phospho-p42MAPK (Try202)/p44MAPK (Try204) (ERK1/2), p42MAPK (Try202)/p44MAPK (Try204), and anti-EGFR antibodies. Equal protein loading was confirmed by membrane reprobing with anti-c-Src, anti-ERK, and anti-EGFR antibodies. The corresponding bands were scanned, and intensities were normalized to anti-c-Src, anti-ERK, and anti-EGFR from the same tubular cell protein extract. One representative Western blot is shown for every experiment. A: phosphorylation of c-Src (p-c-Src; top) compared with total expression of c-Src (bottom). B: phosphorylation of ERK (p-ERK; top) compared with total expression of ERK (bottom). C: phosphorylation of EGFR (top) compared with total expression of EGFR (bottom). Bar graphs depict the quantitative densitometry analysis for Western blot densitometry data. Values are means ± SE of 4 independent experiments. ns, Not significant compared with control. **P < 0.01 for comparison with control.

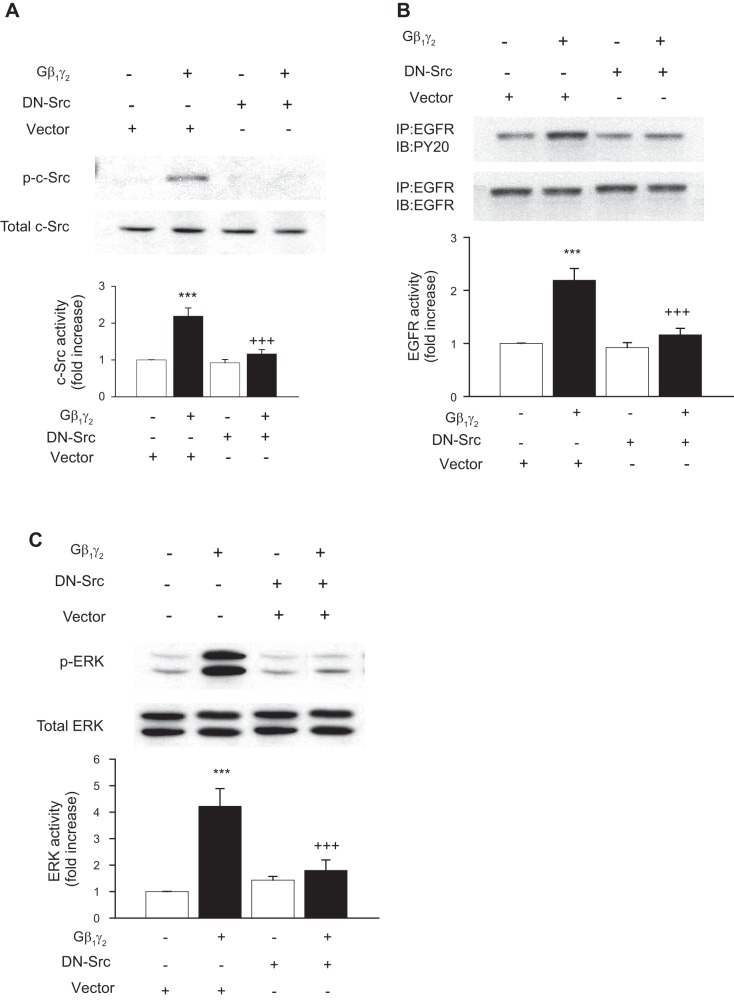

Effect of different Gβγ combinations on EGFR, c-Src, and ERK1/2 activity.

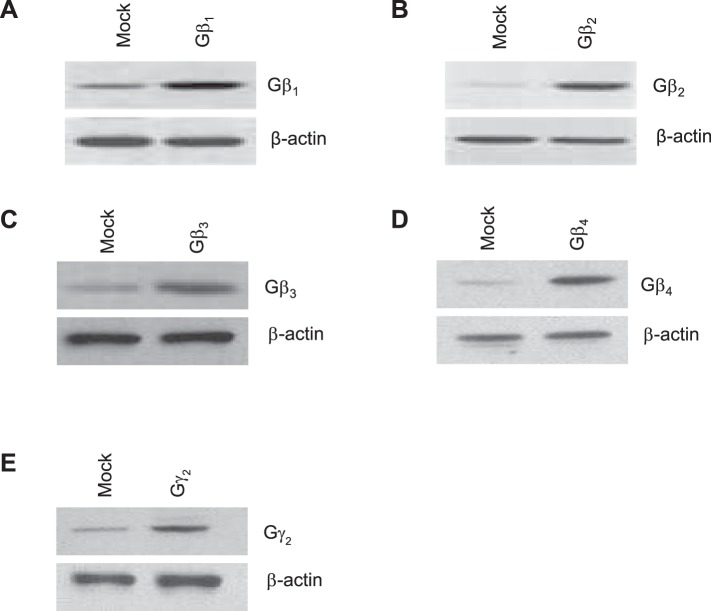

Next, we studied the possibility that Gβγ dimers in addition to Gβ1γ2 activate EGFR, c-Src, and ERK1/2. Figure 2 shows that rabbit proximal tubule epithelium expresses endogenous Gβ1, Gβ2, Gβ3, and Gβ4, of which the β1 is the predominant isoform. In addition, as a positive control for the anti-Gβ1–Gβ4, Gβ1–Gβ4 subunits were transfected into rabbit proximal tubule cells and the expression levels of Gβ1–Gβ4 were determined by Western blot analysis (Fig. 2). Moreover, results in Fig. 3 show that, in contrast to the significant stimulatory effect of Gβ1γ2 on EGFR, c-Src, and ERK1/2 activity, these effects were not observed in proximal tubular cells transfected with equal amounts of DNA for expression of Gβ2γ2, Gβ3γ2, or Gβ4γ2. Taken together, these results indicate, by overexpression, that the stimulatory effect of Gβγ on EGFR, c-Src, and ERK1/2 activity is isoform specific in rabbit proximal tubular cells and that only Gβ1γ2 was able to induce a significant increase in the phosphorylation of EGFR, c-Src, and ERK1/2. The activation of EGFR, c-Src, and ERK1/2 in proximal tubules by GβY subunits is novel.

Fig. 2.

Endogenous expression of different Gβγ subunits. Rabbit proximal tubule cells were transiently transfected with empty vector (mock) or 10 μg each of the expression plasmids for Gβ1, Gβ2, Gβ3, Gβ4, or Gγ2. Equal amounts of cell lysates (30 μg) were resolved by SDS-PAGE followed by Western blotting with the specified antibodies. Equal protein loading was confirmed by membrane reprobing with an anti-β-actin antibody. The blot shown is representative of 4 independent experiments.

Fig. 3.

Effect of different Gβγ combinations on EGFR, c-Src, and ERK activity. Rabbit proximal tubule cells were transiently transfected without (mock) or with 10 μg of the expression plasmids for Gβ1, Gβ2, Gβ3, Gβ4, or Gγ2. Equal amounts of cell lysates (30 μg) were resolved by SDS-PAGE followed by Western blotting with anti-EGFR, anti-phospho-c-Src (Tyr416), and anti-phospho-p42MAPK (Try202)/p44MAPK (Try204) (ERK1/2), and p42MAPK (Try202)/p44MAPK (Try204) antibodies. Equal protein loading was confirmed by membrane reprobing with anti-EGFR, anti-c-Src, or anti-ERK antibodies. The corresponding bands were scanned, and intensities were normalized to anti-EGFR, anti-c-Src, and anti-ERK from the same tubular cell protein extract. One representative Western blot is shown for every experiment. A: phosphorylation of EGFR (top) compared with total expression of EGFR (bottom). B: phosphorylation of c-Src (p-c-Src; top) compared with total expression of c-Src (bottom). C: phosphorylation of ERK (p-ERK; top) compared with total expression of ERK (bottom). Bar graphs depict the quantitative densitometry analysis for Western blot densitometry data. Values are means ± SE of 4 independent experiments. ***P < 0.001, **P < 0.01 for comparison with control.

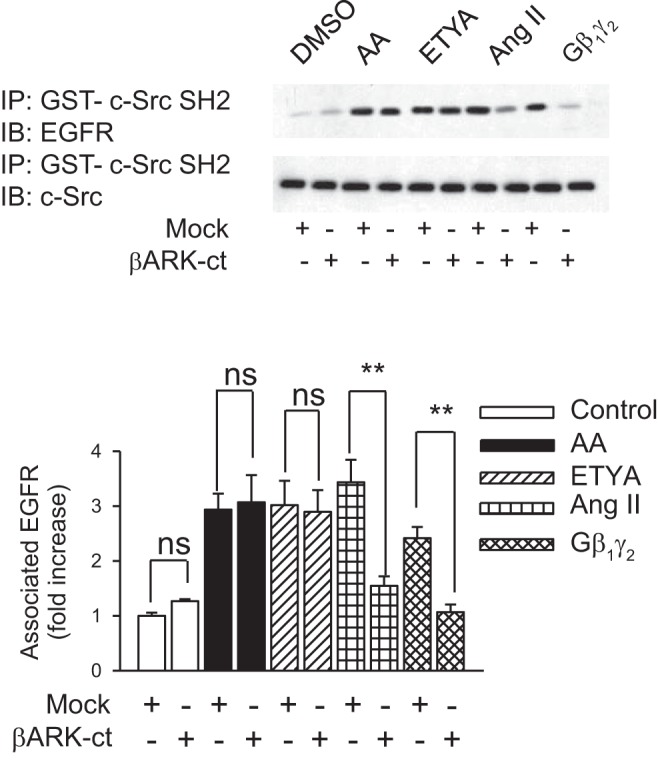

Gβγ induces binding of EGFR with the SH2 domain GST fusion protein.

To determine whether Gβ1γ2 also induced binding of EGFR with the SH2 domain fusion protein, cell lysates were immunoprecipitated with a c-Src SH2 domain GST fusion protein and subsequently immunoblotted with monoclonal anti-EGFR antibodies. As shown in Fig. 4, ANG II, arachidonic acid, and ETYA induced an association of c-Src SH2- domain with EGFR in a manner similar to Gβ1γ2. Overexpression of βARK-ct totally abrogated Gβ1γ2- and ANG II-induced association of EGFR with the SH2 domain GST fusion protein, while having no effect on arachidonic acid- and ETYA-induced association of EGFR with the SH2 domain GST fusion protein.

Fig. 4.

Gβγ induces binding of EGFR with the SH2 domain of c-Src kinase. βARK-ct or empty vector (mock) plasmids were transfected into rabbit proximal tubule cells 24 h before assay. Proximal tubule cells were treated with 0.1% DMSO (vol/vol), AA (15 μmol/l), ETYA (15 μmol/l), or ANG II (1 μmol/l) for 5 min or plasmids encoding β1 and γ2 (5 μg each) for 24 h. At these treatments, interaction of the EGFR with glutathione-S-transferase (GST)-c-Src SH2 and GST-c-Src SH3 was performed by pull-down of GST fusion protein (IP) and immunoblotted (IB) with anti-EGFR antibody (top). The membrane was stripped and reprobed with an anti-c-Src monoclonal antibody (bottom). Comparable amounts of proteins were detected in immunoprecipitates of all the above experiments. Quantitation of EGFR phosphorylation was determined semiquantitively by densitometric scanning of each Western blot. Bar graphs depict the quantitative densitometry analysis for Western blot densitometry data. Values are means ± SE of 4 independent experiments. **P < 0.01 for comparison with control.

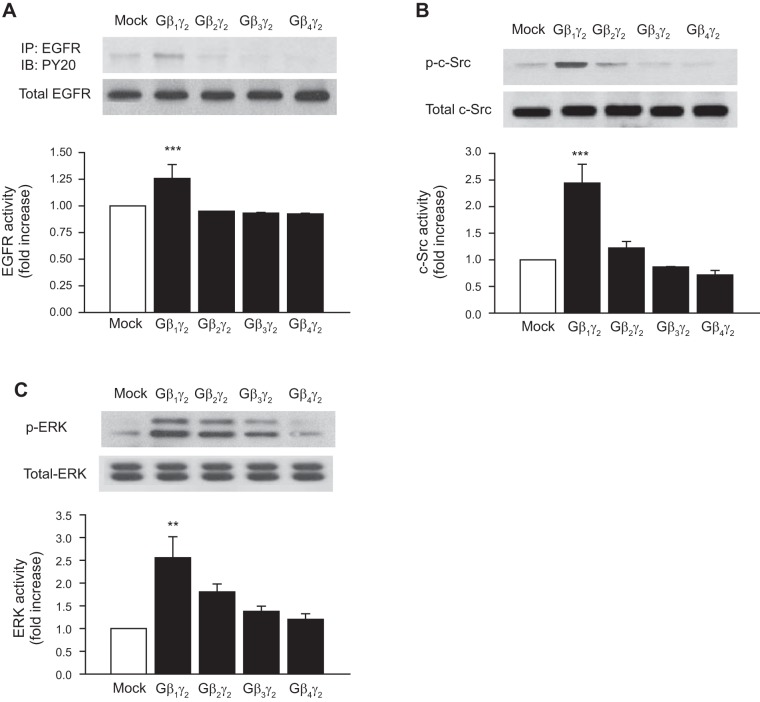

Gβ1γ2 induces EGFR and ERK1/2 phosphorylation in a c-Src-dependent manner.

We previously showed that pretreatment of proximal tubule cells with PP2, a Src family tyrosine kinase inhibitor, or transfection of proximal tubule cells with DN-Src, did not affect the ability of EGF to stimulate EGFR and ERK1/2 activation, but significantly reduced ANG II- and arachidonic acid-induced c-Src, EGFR, and ERK1/2 activation (3). We now demonstrate that transfection of DN-Src significantly decreased Gβ1γ2-induced c-Src, EGFR, and ERK1/2 activation (Fig. 5, A, B, and C, respectively). Collectively, these data demonstrate that, in early passages of kidney epithelial cells, Gβ1γ2, ANG II, and arachidonic acid induce EGFR, c-Src, and ERK1/2 activation. Moreover, c-Src appears to be upstream of EGFR and ERK1/2, and the induced transactivation of EGFR appears to occur via inducing the association of EGFR with the SH2 domain of the Src protein.

Fig. 5.

Involvement of c-Src in Gβγ-induced EGFR transactivation and ERK activation in rabbit proximal tubule cells. Rabbit proximal tubule cells were transiently cotransfected with pCMV5 (empty vector) or a dominant negative Src mutant (DN-Src) in combination with Gβ1 and Gγ2. The expression and phosphorylation of EGFR, c-Src, and ERK1/2 were analyzed by Western blotting of tubular cell protein extract. One representative Western blot is shown for every experiment. A: phosphorylation of c-Src (p-c-Src; top) compared with total expression of c-Src (bottom). B: phosphorylation of EGFR (top) compared with total expression of EGFR (bottom). C: phosphorylation of ERK1/2 (p-ERK; top) compared with total expression of ERK1/2 (bottom). Bar graphs depict the quantitative densitometry analysis for Western blot densitometry data. Values are means ± SE of 4 independent experiments. ***P < 0.001 indicates significant difference compared with nonstimulated control cells. +++P < 0.001 indicates significant difference compared with the respective values of cells transfected with Gβ1γ2 alone.

cPLA2 inhibition attenuates ANG II- and Gβ1γ2-induced arachidonic acid release and c-Src and ERK1/2 activation.

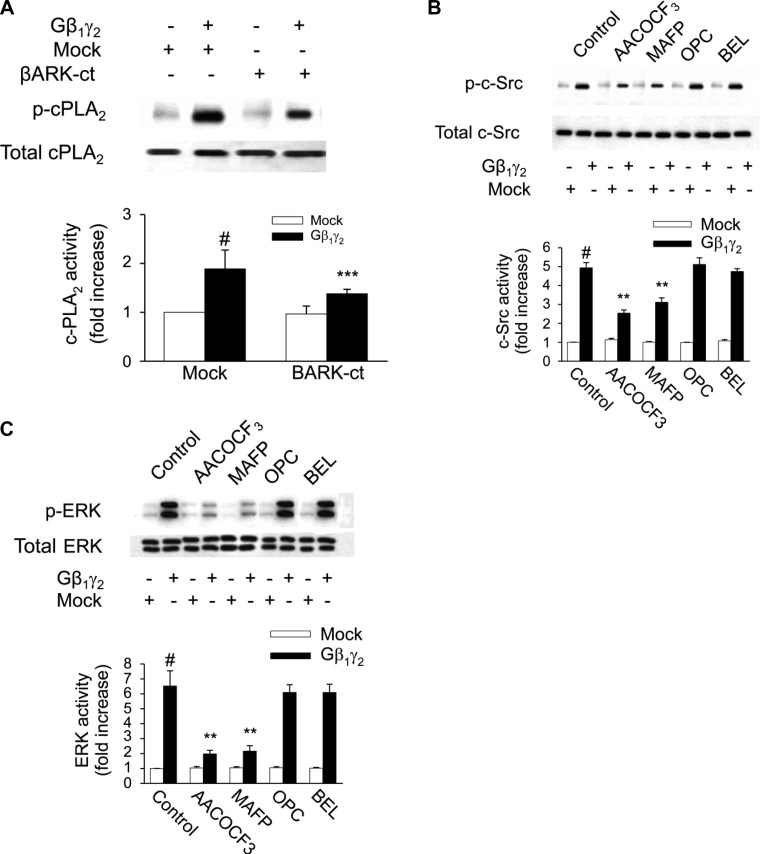

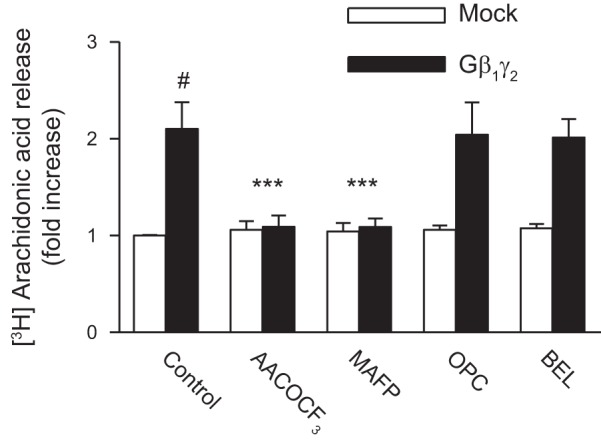

The renal epithelial AT2 receptor and PLA2 signaling complex appears to be linked to Gβγ in that overexpression of Gβ1γ2 augments ANG II-induced arachidonic acid release in proximal tubule cells and βARK-ct abrogates ANG II-induced arachidonic acid release under basal conditions and with overexpression of Gβ1γ2 (19). However, the mechanism of cPLA2 phosphorylation and arachidonic acid release is still unresolved. We show here that overexpression of Gβ1γ2 subunits activates cPLA2 in primary cultured renal proximal tubular cells (Fig. 6A), resulting in increased intracellular and extracellular arachidonic acid release (Fig. 7). The use of different PLA2 inhibitors revealed that Gβ1γ2-induced arachidonic acid release is mediated by activation of cPLA2, whereas iPLA2 or sPLA2 does not seem to be involved in the response to Gβ1γ2 (Fig. 7). Similarly, the cPLA2-specific inhibitors MAFP and AACOCF3 prevented c-Src and ERK1/2 activation of cultured epithelial cells upon Gβ1γ2 stimulation, whereas inhibitors specific for iPLA2 or sPLA2 were without effect (Fig. 6, B and C, respectively). On the other hand, neither PKC inhibitor GF1092003x nor PLC inhibitor U73122 affected the stimulatory effect of Gβ1γ2 on arachidonic acid release and cPLA2, c-Src, and ERK1/2 activity (data not shown). Accordingly, these results suggest that arachidonic acid generation by activation of cPLA2 during Gβ1γ2 stimulation plays an important role in the induction of c-Src and ERK1/2 activation in renal proximal tubular AT2 receptor signaling that is independent of both PKC and PLC.

Fig. 6.

Cystolic (c) PLA2 is involved in Gβγ-induced c-Src and ERK activity. Rabbit proximal tubule cells were treated with 2 cPLA2 inhibitors, arachidonyl trifluoromethyl ketone (AACOCF3; 10 μmol/l) and methyl arachidonyl fluorophosphate (MAFP; 10 μmol/l), sPLA2 inhibitor oleyloxyethyl phosphorylcholine (OPC; 10 μmol/l), iPLA2 inhibitor bromoenol lactone (BEL; 10 μmol/l) for 15 min or the vehicle DMSO, then transfected with Gβ1γ2 or empty vector (mock) for 24 h. At the end of incubation, the expression and phosphorylation of c-Src and ERK1/2 were analyzed by Western blotting of tubular cell protein extract. One representative Western blot is shown for every experiment. A: phosphorylation of c-PLA2 (p-cPLA2; top) compared with total expression of c-PLA2 (bottom). B: phosphorylation of c-Src (p-c-Src; top) compared with total expression of c-Src (bottom). C: phosphorylation of ERK1/2 (p-ERK, top) compared with total expression of ERK1/2 (bottom). Bar graphs depict the quantitative densitometry analysis for Western blot densitometry data. Values are means ± SE of 4 independent experiments shown as fold-increase. #P < 0.001, compared with nonstimulated control (mock) cells. **P < 0.01, compared with the respective values of cells transfected with Gβ1γ2 alone.

Fig. 7.

Effects of PLA2 inhibitors on AA release. Subconfluent proximal tubular cells were labeled with 0.5 μCi·ml−1·well−1 [3H]AA for 4 h before treatment. They were treated with10 μmol/l AACOCF3, MAFP, OPC, or BEL for 15 min or the vehicle DMSO, then transfected with Gβ1γ2 or empty vector (mock) for 24 h. At the end of incubation, an aliquot of medium was removed and counted for radioactivity. Values are means ± SE of 4 independent experiments shown as fold-increase. #P < 0.001, compared with nonstimulated control (mock) cells. ***P < 0.001, compared with the respective values of cells transfected with β1γ2 alone.

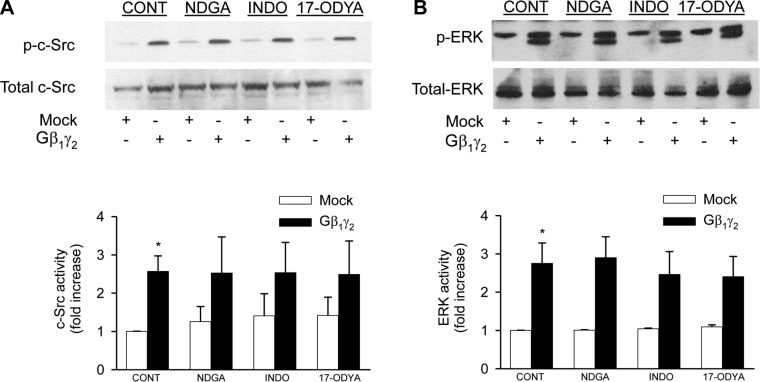

Gβ1γ2-induced EGFR, c-Src, and ERK1/2 phosphorylation is eicosanoid independent.

To assess whether the stimulatory effect of Gβ1γ2 on EGFR, c-Src, and ERK1/2 phosphorylation was mediated by arachidonic acid metabolites, inhibitors of different arachidonic acid metabolic pathways were used. Figure 8 shows that when primary proximal tubule cells were treated with 10 μmol/l 17-ODYA (a specific inhibitor of the cytochrome P-450 pathway); it had no effect on Gβ1γ2-induced stimulation of Src-Src and ERK1/2 phosphorylation. In addition, pretreatment of proximal tubular cells with either 5 μmol/l NDGA (an inhibitor of the lipoxygenase pathway) or 50 μmol/l indomethacin did not affect arachidonic acid-induced c-Src and ERK1/2 phosphorylation. Thus the fact that Gβ1γ2-induced c-Src and ERK1/2 activation was not significantly altered in the presence of the specific cytochrome P-450 inhibitor 17-ODYA, as well as in the presence of the selective lipoxygenase and cyclooxygenase inhibitors NDGA and indomethacin, respectively, indicates that Gβ1γ2-induced c-Src and ERK1/2 activation is independent of eicosanoid biosynthesis.

Fig. 8.

Gβ1γ2-induced c-Src and ERK phosphorylation is eicosanoid independent. Serum-starved proximal tubular cells were transfected with Gβ1γ2 or empty vector (mock) for 24 h. Cell lysates were immunoblotted with anti-phospho-c-Src-Tyr416 (A, top) or anti-phospho-ERK1/2 (p44/42 MAPK)-Thr202/Tyr204 (B, top) antibodies, and membranes were stripped and reprobed with anti-c-Src (A, bottom) or anti-ERK1/2 antibodies (B, bottom). Bar graphs depict the quantitative densitometry analysis for Western blot densitometry data. Values are means ± SE of 4 independent experiments. *P < 0.05 indicates a significant effect of Gβ1γ2 compared with empty vector (mock)-treated cells.

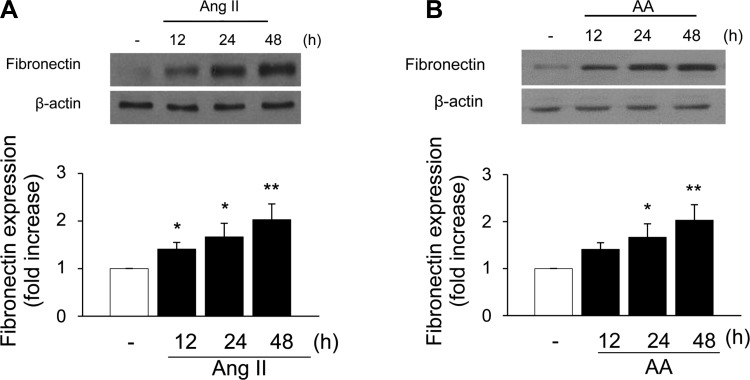

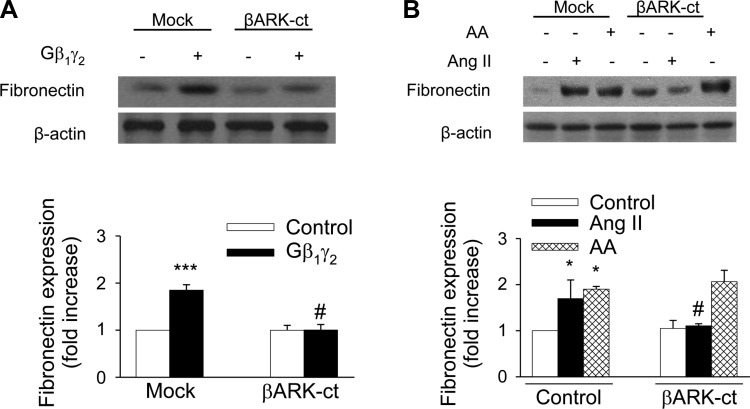

ANG II induces fibronectin protein expression via c-Src, EGFR, and ERK1/2 in renal proximal tubular cells.

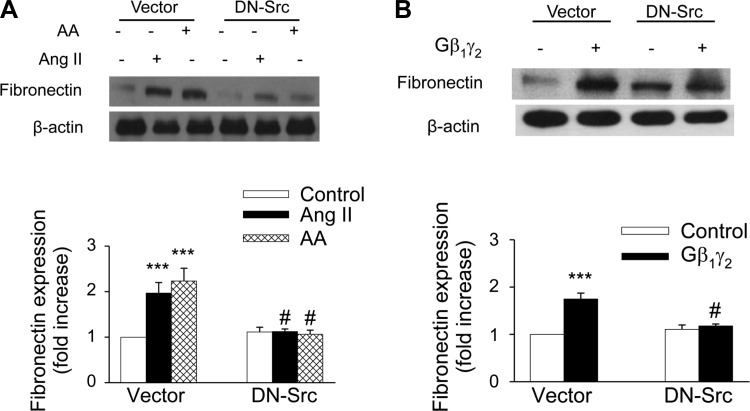

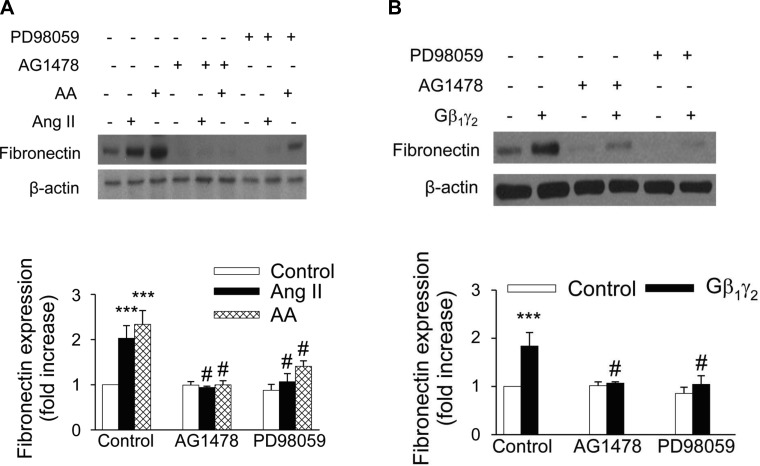

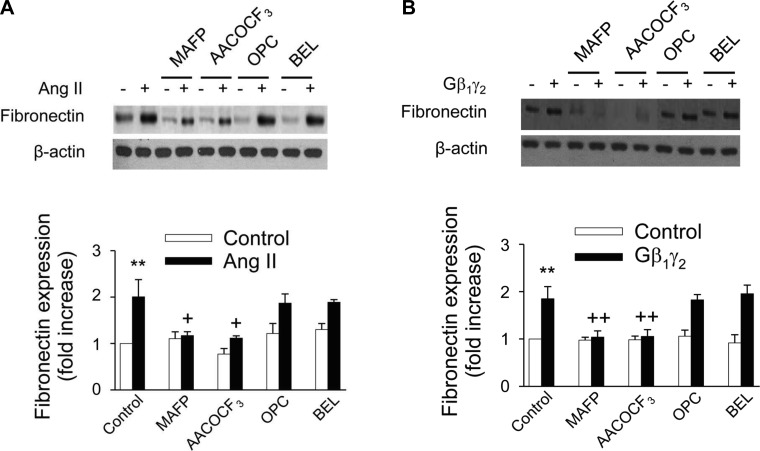

ANG II has been reported to be associated with the development of renal interstitial fibrosis through the stimulation of fibronectin protein expression (8, 41, 42, 49). However, the molecular mechanisms of the ANG II-induced fibronectin in renal proximal tubule cells have not been extensively studied. Moreover, the role of G protein βγ in mediating the effects of ANG II has not been investigated. We recently reported that ANG II-induced ERK1/2 and c-Src activation in kidney epithelium occurs via AT2 receptor-dependent signaling pathways and that ANG II evokes arachidonic acid release by stimulating cPLA2 in rabbit proximal tubule cells (3, 12). To assess the effect of ANG II on fibronectin expression, proximal tubular cells were treated with 1 μmol/l ANG II for various time periods. ANG II induced a significant increase in fibronectin protein expression (1.41-fold compared with control) within 12 h, and the expression was sustained until 48 h (Fig. 9A). Arachidonic acid mimicked the effect of ANG II on fibronectin protein expression, in that direct stimulation of proximal tubular cells with arachidonic acid (15 μmol/l) induced the expression of fibronectin protein in a time-dependent manner, corresponding to the kinetic of fibronectin expression after exposure to ANG II (Fig. 9B). In addition, overexpression of proximal tubule cells with Gβ1γ2 induced fibronectin protein expression (Fig. 10A), which was inhibited by transient transfection of proximal tubular cells with βARK-ct. Transfection of βARK-ct prevented ANG II, but not arachidonic acid, upregulation of fibronectin protein expression (Fig. 10B). Furthermore, expression of a dominant negative mutant of c-Src abrogated ANG II-, arachidonic acid-, and Gβ1γ2-induced fibronectin protein expression (Figs. 11, A and B, respectively). Similar inhibition was demonstrated by the EGFR kinase inhibitor AG1478 and MEK inhibitor PD 98059 (Fig. 12, A and B, respectively).

Fig. 9.

ANG II and AA induce fibronectin protein expression in rabbit proximal tubular epithelial cells. A: serum-starved proximal tubular cells were incubated in the absence (open bar) or presence (closed bars) of 1 μmol/l ANG II for the indicated times, cell lysates were fractionated on SDS-PAGE, and fibronectin protein expression was assessed by direct immunoblotting of cell lysates (top). B: serum-starved proximal tubular cells were incubated in the absence (open bar) or presence (closed bars) of 15 μmol/l AA for the indicated times, cell lysates were fractionated on SDS-PAGE, and fibronectin protein expression was assessed by direct immunoblotting of cell lysates (top). Actin was included as a control for loading and the specificity of change in protein expression. A representative blot from 6 independent experiments is shown. Bar graph at the bottom represents the ratio of the intensity of the fibronectin band quantified by densitometry factored by the densitometric measurements of the actin band. Values are means ± SE from 6 independent experiments. **P < 0.01 and *P < 0.05 vs. control.

Fig. 10.

Gβγ subunits mediate ANG II-induced fibronectin expression. βARK-ct or empty vector (mock) plasmids (10 μg each) were transfected into rabbit proximal tubule cells 24 h before assay. Proximal tubule cells were treated with control [0.1% DMSO (vol/vol)], ANG II (1 μmol/l), AA (15 μmol/l), or plasmids encoding β1 and γ2, (5 μg each) for 48 h. Cell lysates were fractionated on SDS-PAGE, and fibronectin protein expression was assessed by direct immunoblotting of cell lysates (top). Actin was included as a control for loading and the specificity of change in protein expression. A representative blot from 6 independent experiments is shown. Bar graph at the bottom represents the ratio of the intensity of the fibronectin band quantified by densitometry factored by the densitometric measurements of the actin band. Values are means ± SE from 6 independent experiments. *P < 0.05, ***P < 0.001 vs. control. #P < 0.001 vs. βARK-ct.

Fig. 11.

ANG II-, AA-, and Gβ1γ2-induced fibronectin expression is dependent on c-Src. Cells were transfected (10 μg) with a plasmid carrying a c-Src dominant negative (DN-Src) construct or an empty vector before incubation with or without ANG II (1 μmol/l) or AA (15 μmol/l; A) or before transfection with plasmids encoding β1 and γ2, (5 μg each; B) for 48 h. Cell lysates were fractionated on SDS-PAGE, and fibronectin protein expression was assessed by direct immunoblotting of cell lysates (top). Actin was included as a control for loading and the specificity of change in protein expression. A representative blot from 4 independent experiments is shown. Bar graph at the bottom represents the ratio of the intensity of the fibronectin band quantified by densitometry factored by the densitometric measurements of the actin band. Values are means ± SE from 4 independent experiments. ***P < 0.001 vs. control. #P < 0.001 vs. DN-Src.

Fig. 12.

EGFR and ERK mediate ANG II-, AA-, and Gβ1γ2-induced fibronectin expression. Serum-starved proximal tubule cells were incubated with ANG II (1 μmol/l) or AA (15 μmol/l; A) or plasmids encoding β1 and γ2 (5 μg each; B) for 48 h in the absence or presence of MAP kinase kinase (MEK) inhibitor PD98059 (50 μmol/l) or EGFR kinase inhibitor AG1478 (100 nmol/l) for 48 h. Cell lysates were fractionated on SDS-PAGE, and fibronectin protein expression was assessed by direct immunoblotting of cell lysates (top). Actin was included as a control for loading and the specificity of change in protein expression. A representative blot from 4 independent experiments is shown. Bar graph at the bottom represents the ratio of the intensity of the fibronectin band quantified by densitometry factored by the densitometric measurements of the actin band. Values are means ± SE from 4 independent experiments. ***P < 0.001 vs. control. #P < 0.001 vs. ANG II-, AA-, or Gβ1γ2-treated cells.

cPLA2 inhibitors attenuated ANG II- and Gβ1γ2-induced fibronectin protein expression.

Since we have found that the cPLA2-specific inhibitors MAFP and AACOCF3 prevented c-Src and ERK1/2 activation in these cells (Fig. 6, B and C, respectively), we were interested in examining whether PLA2 could be involved in ANG II- and Gβ1γ2-induced fibronectin expression. Proximal tubular cells were preincubated without or with 10 μmol/l of MAFP, AACOCF3, BEL, or OPC followed by 1 μmol/l ANG II for 48 h. Western blot analysis showed that the two cPLA2 inhibitors MAFP and AACOCF3 strongly suppressed ANG II-induced fibronectin protein expression. Conversely, the iPLA2 inhibitor BEL and sPLA2 inhibitor OPC (Fig. 13A) did not affect fibronectin expression. Moreover, the effects of both ANG II and Gβ1γ2 on fibronectin protein expression were not attenuated by pretreatment of proximal tubular cells with 17-ODYA, NDGA, or indomethacin (data not shown). These observations document a mechanism of ANG II- and Gβ1γ2-induced fibronectin expression, mediated by cPLA2-dependent arachidonic acid release and independent of eicosanoid biosynthesis.

Fig. 13.

Blocking cPLA2 but not Ca2+-independent (i) PLA2 or secretory (s) PLA2 reversed the effects of ANG II and Gβ1γ2 on fibronectin expression. Renal proximal tubular cells were treated with 10 μmol/l AACOCF3, MAFP, OPC, or BEL for 15 min or the vehicle DMSO, then stimulated with ANG II (1 μmol/l; A) or transfected with plasmid encoding β1 and γ2 (5 μg each) or empty vector (mock, 10 μg; B) for 48 h. At the end of incubation, cell lysates were fractionated on SDS-PAGE, and fibronectin protein expression was assessed by direct immunoblotting of cell lysates (top). Actin was included as a control for loading and the specificity of change in protein expression. A representative blot from 6 independent experiments is shown. Bar graph at the bottom represents the ratio of the intensity of the fibronectin band quantified by densitometry factored by the densitometric measurements of the actin band. Values are means ± SE from 6 independent experiments. **P < 0.001 vs. control. ++P < 0.001, +P < 0.05 vs. ANG II- or Gβ1γ2-treated cells.

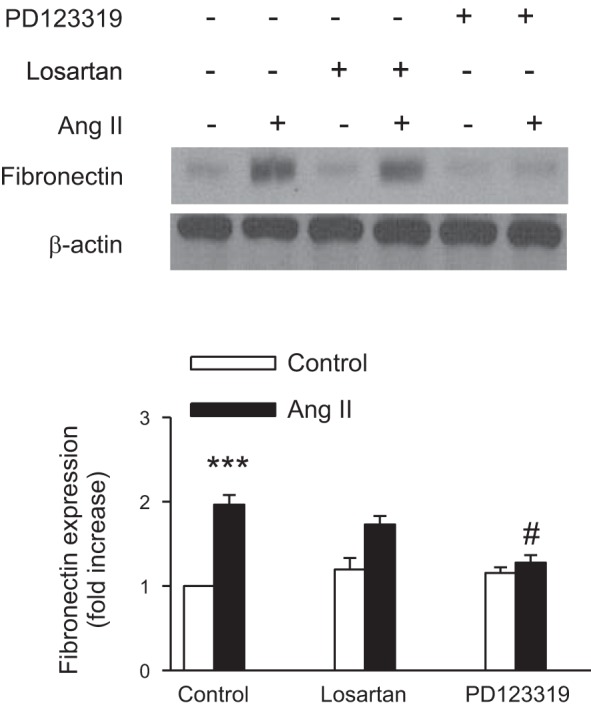

ANG II induces fibronectin expression via the AT2 receptor.

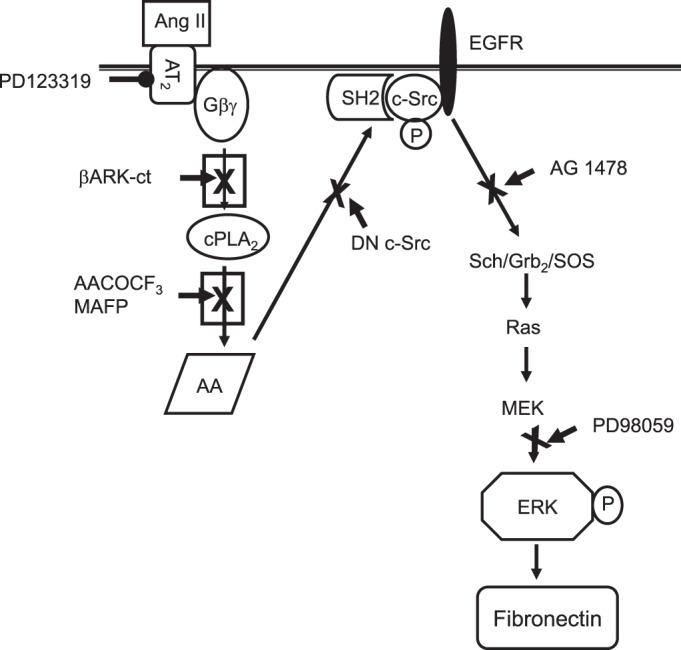

To discriminate which ANG II receptor subtype was involved in fibronectin expression, both AT1 and AT2 receptor blockers were used. The AT2-selective antagonist PD123319, but not the AT1-selective antagonist losartan, inhibited ANG II-induced fibronectin synthesis (Fig. 14). These results support a role for the AT2 receptor as a mediator of fibronectin synthesis. The observations with Gβγ and βARK-ct as described and discussed herein suggest a model for ANG II- and arachidonic acid-induced fibronectin synthesis and EGFR, c-Src, and ERK1/2 activation, as depicted in Fig. 15.

Fig. 14.

ANG II induces fibronectin expression via the AT2 receptor. Rabbit proximal tubule cells were treated with losartan (1 μmol/l), an AT1 receptor antagonist, or PD123319 (10 μmol/l), an AT2 receptor antagonist, for 60 min or the vehicle DMSO, then stimulated with ANG II (1 μmol/l) for 48 h. At the end of incubation, cell lysates were fractionated on SDS-PAGE, and fibronectin protein expression was assessed by direct immunoblotting of cell lysates (top). Actin was included as a control for loading and the specificity of change in protein expression. A representative blot from 4 independent experiments is shown. Bar graph at the bottom represents the ratio of the intensity of the fibronectin band quantified by densitometry factored by the densitometric measurements of the actin band. Values are means ± SE from 4 independent experiments. ***P < 0.001 vs. control. #P < 0.001 vs. ANG II- treated cells.

Fig. 15.

Schematic diagram outlines a signaling pathway that may mediate ANG II- and AA-induced ERK activation and fibronectin synthesis from G protein-coupled receptors and receptor tyrosine kinase in rabbit proximal tubule cells consistent with our present and previous observations. Both ANG II and AA induce tyrosine phosphorylation of the autophosphorylation site and the SH2 domain of c- Src. However, ANG II, but not AA, leads to Gβγ-dependent c-Src activation, leading to association of Src kinase with EGFR via the SH2 domain. The association of c-Src (through Src SH2 domain) with EGFR results in the mutual stimulation of c-Src catalytic activity and enhanced phosphorylation of Shc/Grb2/Sos and p21Ras, which leads to the activation of ERK and increased fibronectin protein synthesis.

DISCUSSION

Renal fibrosis is characterized by increased synthesis and deposition of ECM proteins, which result in increased fibrotic tubular damage, an effect attributed to increased tubular fibronectin production, leading to end-stage renal disease (ESRD) (32). ANG II has important non-hemodynamic effects that have been implicated in the pathogenesis of chronic kidney disease (CKD), including stimulating the production of fibronectin (27). It has been shown in renal mesangial cells that the expression of fibronectin induced by ANG II involves both ERK1/2 and Akt/PKB pathways (5, 20) and that this effect can be blocked by the AT1 receptor antagonist losartan. Fang et al. (15) found that ANG II induced the expression of fibronectin in renal tubular cells through activation of 5′-AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK) and cAMP pathways. Our present work documents a critical role of Gβγ, cPLA2, and c-Src as alternative mechanisms of ANG II-induced fibronectin expression in renal tubular cells. Thus inhibition of arachidonic acid release by MAFP and AACOCF3, two selective cPLA2 inhibitors, attenuated ANG II- and Gβ1γ2-induced fibronectin expression in proximal tubular cells (Fig. 13, A and B, respectively) and arachidonic acid at low (15 μM/l) concentrations mimicked the effect of ANG II on fibronectin synthesis with a striking parallel in time course (Fig. 9B). Moreover, expression of Gβ1γ2 subunits stimulated expression of fibronectin in renal tubular cells to nearly the same extent as ANG II and arachidonic acid (Fig. 10A). Overexpression of the carboxy terminus of βARK-ct, an endogenous scavenger of Gβγ, resulted in inhibition of fibronectin expression induced by Gβ1γ2 (Fig. 10A) and ANG II (Fig. 10B). In contrast, overexpression of βARK-ct did not inhibit arachidonic acid-induced fibronectin expression (Fig. 10B). Furthermore, expression of a dominant negative mutant of Src markedly inhibited Gβ1γ2-, ANG II-, and arachidonic acid-induced fibronectin expression (Fig. 11, A and B, respectively). In addition, our work demonstrates that ANG II-induced expression of fibronectin was inhibited by the AT2 receptor blocker PD123319, but not by the AT1 receptor blocker losartan (Fig. 14). Additional studies form this laboratory have documented that cPLA2-mediated signaling is linked to the relatively low-affinity AT2 ANG II receptor (3, 19, 25, 26) that is pharmacologically distinct from the AT2 receptor cloned previously (22, 36). Moreover, this apical AT2 receptor mediates ANG II-induced arachidonic acid release and downstream events such as Shc/Grb2/Sos and p21ras association, and c-Src and ERK1/2 activation (3, 12, 25, 26). Thus this represents an additional signaling model for AT2 receptor subtypes and G protein-coupled receptors as well.

Molecular biological observations validate the existence of two major ANG II receptor subtypes (AT1 and AT2). These receptor subtypes are pharmacologically distinct and share only ∼30% sequence homology. While the AT1 receptor has been considered to subserve many of the biological functions linked to ANG II, emerging evidence indicates that the adult AT2 receptor may also mediate significant biological responses as well. Renal proximal tubular cells express a novel complement of both AT1 (basolaterally oriented) and AT2 (apically oriented) receptor subtypes that mediate many renal functions in responses to ANG II. Notable differences exist between the ANG II receptor subtypes expressed in the kidney and other locations: 1) the kidney epithelial AT2 receptor (AT2B) differs from cloned fetal AT2 (AT2A) in that G protein coupling was demonstrated pharmacologically in vitro; 2) binding affinity for losartan, PD123319, and CGP42112a differed between AT2A and AT2B; 3) signaling linked to AT2B is through a membrane-associated PLA2, arachidonic acid release, and activation of the MAPK superfamily (ERK1/2, p38 MAPK, and c-JNK), while AT2A is linked to a MAPK phosphatase (MKP) and/or PP2A and, by contrast, inhibition of MAPK phosphorylation; 4) the renal epithelial AT2 receptor-PLA2 signaling complex appears to be linked to G protein βγ, in that overexpression of Gβ1γ2 subunits augments ANG II-induced arachidonic acid release, and βARK-ct abrogates ANG II-induced arachidonic acid release under basal conditions and with overexpression of Gβ1γ2; and 5) the renal AT1 receptor differs from the vascular AT1 receptor as its signaling is linked primarily to adenyl cyclase rather than inositol-specific PLC, and receptor expression is upregulated in high ambient ANG II concentration rather than downregulated. Thus there are substantial differences in binding, G protein interaction, signaling, and MAPK regulation between the cloned AT2A and the epithelial isoform AT2B. Hence, to date, the role of the AT2 receptor in renal fibrosis remains elusive. In human renal fibroblasts, Schuttertet et al. (41) and Hua et al. (20) showed that ANG II-mediated effect on fibronectin synthesis was diminished in the presence of the AT1 receptor blocker losartan, while no inhibition was observed using the AT2 receptor blocker PD123319. Ray et al. (38), in human fetal mesangial cells, obtained similar results. Based on the data presented in this paper, we propose a role for the AT2 receptor in the synthesis of fibronectin, in that the increased fibronectin response to ANG II was completely inhibited by the AT2 receptor antagonist PD123319, while the AT1 receptor antagonist losartan had no effect. Despite the fact that several studies have suggested that ANG II-induced fibronectin synthesis is mediated by AT1 rather than AT2 signaling, the interpretation relied on use of pharmacological concentrations of losartan that can compete at high concentrations for AT2 receptor sites (38, 41, 51). Moreover, this is the first study to investigate the role of ANG AT1 and AT2 receptors in ANG II-induced fibronectin synthesis in cultured proximal tubular epithelial cells. Furthermore, ANG II-AT2-induced fibronectin synthesis in rabbit proximal tubular cells appears to be mediated at least in part by EGFR, c-Src, and ERK1/2 activation, since introduction of pharmacological inhibitors and dominant negative mutants blocked this effect. While these data suggest that ANG II, operating through the AT2 receptor, exerts an antifibrotic effect on the kidney in vitro, they do not negate the beneficial effects of losartan and other AT1 receptor antagonists on cells other than rabbit proximal tubule or different models of renal injury. The composite mechanism and relationship to AT2 receptor and downstream events leading to fibronectin synthesis is depicted in Fig. 15.

Previous studies have documented that the Gβγ subunits mediate α2-adrenergic- and lysophosphatidic acid LPA-induced activation of c-Src in transfected Cos-7 cells as a mechanism of Gαi-coupled receptor recruitment of the Shc-Grb2-Sos complex and activation of members of MAPK, including the ERK1/2 pathway (33). These observations have relevance to our current kidney epithelial cell signaling model in that we have documented that an apical AT2-receptor subtype mediates ANG II-induced ERK1/2 activation by transactivation of EGFR (13). Moreover, this AT2 signaling involves Gβγ-mediated PLA2 activation, arachidonic acid release, and downstream events linked to Shc-Grb2-Sos and p21Ras rather than PKC, as reported previously for ANG II receptors (19, 26). In addition, ANG II activates c-Src and in these epithelial cells (3). The involvement of Gβγ subunits in this AT2 receptor signaling paradigm is novel with respect to ANG II receptor subtypes, for this and other locations, as other studies have focused on a linkage to G protein α subunits including Gαq, Gα2, and Gα3 (45, 50). Even more important, the involvement of arachidonic acid in this AT2 receptor signaling paradigm is unique from the perspective that this common lipid second messenger mimics all ANG II events evaluated to date in these epithelial cells. The activation of c-Src is no exception, as it too is activated by arachidonic acid, analogous to ANG II (3). However, unresolved questions persist as to the mechanism(s) whereby arachidonic acid, a fatty acid, is linked to the receptor tyrosine kinase and non-tyrosine kinase pathways. In the present study, we further extend our previous findings by demonstrating that exogenously expressed Gβ1γ2 subunits lead to tyrosine phosphorylation of both c-Src and EGFR, association of EGFR with the SH2 domain of c-Src, stimulation of the ERK1/2 signaling cascade, and fibronectin production in rabbit proximal tubule cells. Conversely, reducing free endogenous Gβγ concentrations by exogenous expression of βARK-ct, which contains only the C-terminal Gβγ-binding domain of βARK (28, 37), significantly inhibits Gβ1γ2 subunit-induced phosphorylation of c-Src, EGFR, and ERK1/2 and fibronectin protein expression. Inhibition of endogenous Src family kinase activity by overexpression of a dominant negative kinase-inactive mutant of c-Src inhibits Gβ1γ2 subunit-induced phosphorylation of EGFR, c-Src, and ERK 1/2 and fibronectin production. Although we show that Gβγ is required for the transactivation of EGFR, activation of c-Src and ERK1/2, and expression of fibronectin by ANG II, we also demonstrate that Gβγ subunits do not significantly contribute to the transactivation of EGFR, activation of c-Src and ERK1/2, and expression of fibronectin by arachidonic acid.

Membrane phospholipids, acted upon by PLA2 or PLC, form arachidonic acid, an essential, unsaturated, 20-carbon fatty acid, which can be further metabolized by one of three enzyme pathways into various prostaglandins (by cyclooxygenase), leukotrienes (by lipoxygenase), or epoxyeicosatrienoic acids (EETs) and hydroxyeicosatetraenoic acid (HETEs; by cytochrome P-450), which themselves have potent biological activity. The latter constitutes the main pathway of arachidonic acid metabolism in renal proximal tubular epithelium. It is now well documented that arachidonic acid activates many protein kinases in a variety of cells and tissues and that this action can be either dependent or independent of cyclooxygenase-, lipoxygenase-, and cytochrome P-450-derived eicosanoids. Specifically, in the kidney, Chen et al. (7) reported that exogenous exposure of the eicosanoid 14,15- EET activates phosphoinositide 3-kinase, ERK1/2, and c-Src in rat glomerular mesangial cells (7). However, arachidonic acid was without effect. In contrast, Gorin et al. (18) showed that arachidonic acid-induced PKB/Akt activation in mesangial cells is independent of eicosanoid metabolism. By comparison, our previous studies demonstrated a role for arachidonic acid and other fatty acids in signaling linked to the MAPK superfamily and c-Src in rabbit proximal tubular epithelium without the necessity of conversion to cytochrome P-450 metabolites (2).

The renal epithelial AT2 receptor and PLA2 signaling complex appears to be linked to Gβγ in that overexpression of Gβ1γ2 subunits augments ANG II-induced arachidonic acid release in mouse proximal tubule cells and overexpression of βARK-ct abrogates ANG II-induced arachidonic acid release under basal conditions and with overexpression of Gβγ (19). However, the mechanism of cPLA2 phosphorylation and arachidonic acid release is still unresolved. In the present study, we have used MAFP and AACOCF3, two known inhibitors of cPLA2 phosphorylation and activation in the kidney (1, 2), to study the mechanism of arachidonic acid release and c-Src and ERK1/2 activation and fibronectin synthesis in rabbit proximal tubular cells. Previous results obtained with these same cells, within this laboratory, have revealed that Gβ1γ2 is a potent stimulator of arachidonic acid release (19); however, the relative roles of PLA2 isoforms under these conditions have not been analyzed in detail. Therefore, to gain further insight into the mechanism of Gβγ-mediated arachidonic acid release, activation of c-Src and ERK1/2, and fibronectin synthesis, the relative roles of different PLA2 isoforms were analyzed. Here, we show that transfection with Gβ1γ2 resulted in the phosphorylation and activation of cPLA2 and increased arachidonic acid release in rabbit proximal tubule cells. Moreover, the existence of other PLA2 family members, such as sPLA2 and iPLA2, could not be detected in these cells by immunoblotting (data not shown). In addition, βARK-ct markedly suppressed Gβ1γ2-enhanced cPLA2 phosphorylation and arachidonic acid release. In addition, Gβ1γ2-stimulated arachidonic acid release, c-Src and ERK1/2 activation, and fibronectin expression were significantly inhibited by the cPLA2 inhibitors MAFP and AACOCF3. By contrast, BEL and OPC, inhibitors of iPLA2 and sPLA2, respectively, had no inhibitory effect on arachidonic acid release, c-Src and ERK1/2 activity, and fibronectin expression, suggesting the PLA2 activity was attributable to cPLA2. In addition, the Gβ1γ2-stimulatory effects on c-Src and ERK1/2 activation in renal proximal tubular cells appear to be direct and independent of arachidonic acid metabolism. Supporting data derived from the fact that inhibitors of the cyclooxygenase, lipoxygenase, and cytochrome P-450 pathways were ineffective in blocking Gβ1γ2-induced c-Src and ERK1/2 activation. In addition, ETYA, a nonmetabolizable analog of arachidonic acid that blocks all arachidonic acid-metabolizing enzymes, was effective at stimulating these kinases, which is consistent with direct fatty acid-mediated effects on arachidonic acid as the primary effector.

Gβγ subunits have been implicated in a variety of signaling pathways. Direct effects of Gβγ have been documented on PLC (PLCβ1, PLCβ2, PLCβ3,) adenylate cyclase, and type I PLA2 (9, 17, 31, 52). The effector signaling molecules possess pleckstrin homology domains that bind βγ to initiate downstream events (23). By contrast, several studies have suggested that there are indirect effects of Gβγ, which require activation of α subunits. Examples include the requirement of Gαq/11 protein for βγ amplification of PLA2 and arachidonic acid release (43) and c-Src activation (34, 44), the need for activation of Gαs subunit for expression of activation of adenylate cyclase type II and IV (16), and the expression of Gαi protein for the activation of c-Src (33). Additionally, the G protein βγ and α subunits can transactivate EGFR (4, 39) and mediate ANG II-induced EGFR phosphorylation and c-Src and ERK1/2 activity (46). In line with these findings, this laboratory has reported that the Gβγ subunit is involved in activation of arachidonic acid release by ANG II stimulation of AT2B receptors in mouse renal tubular epithelial cells (19). These observations have been supported herein utilizing early passaged proximal tubule epithelial cells employing ANG II and/or arachidonic acid (without the necessity of overexpression of receptors). We observed that overexpression of the Gβγ subunit or stimulation with ANG II and arachidonic acid significantly increased c-Src activity in these cells. Moreover, expressing βARK-ct inhibited Gβγ- and ANG II-stimulated tyrosine phosphorylation of EGFR and c-Src SH2 domain fusion protein and their accompanied increased association. A critical contrast relates to the observation that coexpression of βARK-ct abrogated Gβγ- and ANG II-induced association of c-Src SH2 domain with EGFR and c-Src and ERK1/2 activation, but had no effect on arachidonic acid- and 5,8,11,14-ETYA-induced association and c-Src and ERK1/2 activation. In addition, the effects of GβY on c-Src and ERK1/2 activity and fibronectin synthesis were significantly blocked by overexpression of the dominant negative c-Src mutant (c-Src K298M). While our data with ANG II AT2 receptor signaling support the original model linking the GPCR, βγ, and ERK1/2 pathway, our data with arachidonic acid and its analogs document for the first time that arachidonic acid and ETYA transactivates EGFR via inducing association of the SH2 domain of c-Src with EGFR and induces ERK1/2 activation independent of Gβγ subunits. Moreover, our studies have the potential to provide a novel signaling paradigm for transactivation of kinase receptors following GPCR activation, which may apply to activation of a variety of phospholipases that release fatty acids. The observations with Gβγ and βARK-ct as described and discussed herein suggest a model for ANG II- and arachidonic acid-induced EGFR, c-Src, and ERK1/2 activation and fibronectin synthesis, as depicted in Fig. 15.

In summary, the present studies present interrelated, yet independent mechanisms that mediate the effects of ANG II vs. arachidonic acid on fibronectin synthesis, EGFR transactivation, and c-Src and ERK1/2 activation. Herein, we propose two independent mechanisms for the activation of c-Src to mediate ERK1/2 activation and fibronectin expression, one through Gβγ and the other through GPCR-independent pathways. We implicate Gβγ subunits as targets of ANG II in EGFR, c-Src, and ERK1/2 signaling pathways, whereas arachidonic acid-initiated signaling to EGFR transactivation and c-Src and ERK1/2 pathways is independent of these proteins. Collectively, we were able to show that renal the epithelial AT2 receptor has novel binding and signaling properties that involve Gβγ subunits, cPLA2, and arachidonic acid as critical upstream mediators. In addition, we show for the first time that EGFR, c-Src, and ERK1/2 are directly activated by a mechanism involving cPLA2 mediated- arachidonic acid release initiated by the release of βγ dimers in rabbit proximal tubule cells. Moreover, our results identify a new and novel alternative mechanism involving arachidonic acid-induced transactivation of EGFR via inducing association of the SH2 domain of c-Src with EGFR, independently of Gβγ subunits. This represents an important alternative paradigm whereby GPCRs linked to phospholipases may activate a tyrosine kinase pathway through arachidonic acid independently of a Gβγ subunit.

GRANTS

This work was supported by National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute Grant HL 04363. L. D. Alexander is a National Center on Minority Health and Health Disparities (NCMHD) Scholar.

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the authors.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Author contributions: L.D.A. provided conception and design of research; L.D.A., Y.D., S.A., and X.C. performed experiments; L.D.A., Y.D., S.A., and X.C. analyzed data; L.D.A., Y.D., S.A., and X.C. interpreted results of experiments; L.D.A. prepared figures; L.D.A. drafted manuscript; L.D.A. and X.C. edited and revised manuscript; L.D.A. approved final version of manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1.Alexander LD, Alagarsamy S, Douglas JG. Cyclic stretch-induced cPLA2 mediates ERK 1/2 signaling in rabbit proximal tubule cells. Kidney Int 65: 551–563, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Alexander LD, Cui XL, Falck JR, Douglas JG. Arachidonic acid directly activate members of the MAPK superfamily in rabbit proximal tubule cells. Kidney Int 59: 2039–2053, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Alexander LD, Ding Y, Alagarsamy S, Cui XL, Douglas JG. Arachidonic acid induces ERK activation via Src SH2 domain association with the epidermal growth factor receptor. Kidney Int 69: 1823–1832, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bakken AM, Protack CD, Roztocil E, Nicholl SM, Davies MG. Cell migration in response to the amino-terminal fragment of urokinase requires epidermal growth factor receptor activation through an ADAM-mediated mechanism. J Vasc Surg 49: 1296–1303, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Block K, Ricono JM, Lee DY, Bhandari B, Choudhury GG, Abboud HE, Gorin Y. Arachidonic acid-dependent activation of a p22(phox)-based NAD(P)H oxidase mediates angiotensin II-induced mesangial cell protein synthesis and fibronectin expression via Akt/PKB. Antioxid Redox Signal 8: 1497–1508, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bokemeyer D, Schmitz U, Kramer HJ. Angiotensin II-induced growth of vascular smooth muscle cells requires an Src-dependent activation of the epidermal growth factor receptor. Kidney Int 58: 549–558, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chen JK, Capdevila J, Harris RC. Overexpression of C-terminal Src kinase blocks 14, 15-epoxyeicosatrienoic acid-induced tyrosine phosphorylation and mitogenesis. J Biol Chem 275: 13789–13792, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chow BS, Kocan M, Bosnyak S, Sarwar M, Wigg B, Jones ES, Widdop RE, Summers RJ, Bathgate RA, Hewitson TD, Samuel CS. Relaxin requires the angiotensin II type 2 receptor to abrogate renal interstitial fibrosis. Kidney Int. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Clark MJ, Linderman JJ, Traynor JR. Endogenous regulators of G protein signaling differentially modulate full and partial mu-opioid agonists at adenylyl cyclase as predicted by a collision coupling model. Mol Pharmacol 73: 1538–1548, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Daub H, Wallasch C, Lankenau A, Herrlich A, Ullrich A. Signal characteristics of G protein-transactivated EGF receptor. EMBO J 16: 7032–7044, 1997 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Daub H, Weiss FU, Wallasch C, Ullrich A. Role of transactivation of the EGF receptor in signalling by G-protein-coupled receptors. Nature 379: 557–560, 1996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dulin NO, Alexander LD, Harwalkar S, Falck JR, Douglas JG. Phospholipase A2-mediated activation of mitogen-activated protein kinase by angiotensin II. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 95: 8098–8102, 1998 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dulin NO, Sorokin A, Douglas JG. Arachidonate-induced tyrosine phosphorylation of epidermal growth factor receptor and Shc-Grb2-Sos association. Hypertension 32: 1089–1093, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Eguchi S, Numaguchi K, Iwasaki H, Matsumoto T, Yamakawa T, Utsunomiya H, Motley ED, Kawakatsu H, Owada KM, Hirata Y, Marumo F, Inagami T. Calcium-dependent epidermal growth factor receptor transactivation mediates the angiotensin II-induced mitogen-activated protein kinase activation in vascular smooth muscle cells. J Biol Chem 273: 8890–8896, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fang F, Liu GC, Kim C, Yassa R, Zhou J, Scholey JW. Adiponectin attenuates angiotensin II-induced oxidative stress in renal tubular cells through AMPK and cAMP-Epac signal transduction pathways. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 304: F1366–F1374, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Federman AD, Conklin BR, Schrader KA, Reed RR, Bourne HR. Hormonal stimulation of adenylyl cyclase through Gi-protein beta gamma subunits. Nature 356: 159–161, 1992 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ferry X, Eichwald V, Daeffler L, Landry Y. Activation of betagamma subunits of Gi2 and Gi3 proteins by basic secretagogues induces exocytosis through phospholipase Cbeta and arachidonate release through phospholipase Cgamma in mast cells. J Immunol 167: 4805–4813, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gorin Y, Kim NH, Feliers D, Bhandari B, Choudhury GG, Abboud HE. Angiotensin II activates Akt/protein kinase B by an arachidonic acid/redox-dependent pathway and independent of phosphoinositide 3-kinase. FASEB J 15: 1909–1920, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Haithcock D, Jiao H, Cui XL, Hopfer U, Douglas JG. Renal proximal tubular AT2 receptor: signaling and transport. J Am Soc Nephrol 10, Suppl 11: S69–S74, 1999 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hua P, Feng W, Rezonzew G, Chumley P, Jaimes EA. The transcription factor ETS-1 regulates angiotensin II-stimulated fibronectin production in mesangial cells. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 302: F1418–F1429, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Igishi T, Gutkind JS. Tyrosine kinases of the Src family participate in signaling to MAP kinase from both Gq and Gi-coupled receptors. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 244: 5–10, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Inagami T, Guo DF, Kitami Y. Molecular biology of angiotensin II receptors: an overview. J Hypertens Suppl 12: S83–S94, 1994 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Inglese J, Koch WJ, Touhara K, Lefkowitz RJ. G beta gamma interactions with PH domains and Ras-MAPK signaling pathways. Trends Biochem Sci 20: 151–156, 1995 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ishida M, Ishida T, Thomas SM, Berk BC. Activation of extracellular signal-regulated kinases (ERK1/2) by angiotensin II is dependent on c-Src in vascular smooth muscle cells. Circ Res 82: 7–12, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jacobs LS, Douglas JG. Angiotensin II type 2 receptor subtype mediates phospholipase A2-dependent signaling in rabbit proximal tubular epithelial cells. Hypertension 28: 663–668, 1996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jiao H, Cui XL, Torti M, Chang CH, Alexander LD, Lapetina EG, Douglas JG. Arachidonic acid mediates angiotensin II effects on p21ras in renal proximal tubular cells via the tyrosine kinase-Shc-Grb2-Sos pathway. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 95: 7417–7421, 1998 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kagami S, Border WA, Miller DE, Noble NA. Angiotensin II stimulates extracellular matrix protein synthesis through induction of transforming growth factor-beta expression in rat glomerular mesangial cells. J Clin Invest 93: 2431–2437, 1994 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Koch WJ, Inglese J, Stone WC, Lefkowitz RJ. The binding site for the beta gamma subunits of heterotrimeric G proteins on the beta-adrenergic receptor kinase. J Biol Chem 268: 8256–8260, 1993 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kraus S, Benard O, Naor Z, Seger R. c-Src is activated by the epidermal growth factor receptor in a pathway that mediates JNK and ERK activation by gonadotropin-releasing hormone in COS7 cells. J Biol Chem 278: 32618–32630, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kuang Y, Wu Y, Smrcka A, Jiang H, Wu D. Identification of a phospholipase C beta2 region that interacts with Gbeta-gamma. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 93: 2964–2968, 1996 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kurrasch-Orbaugh DM, Parrish JC, Watts VJ, Nichols DE. A complex signaling cascade links the serotonin 2A receptor to phospholipase A2 activation: the involvement of MAP kinases. J Neurochem 86: 980–991, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lee HB, Ha H. Plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 and diabetic nephropathy. Nephrology (Carlton) 10, Suppl: S11–S13, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Luttrell LM, Della Rocca GJ, van Biesen T, Luttrell DK, Lefkowitz RJ. Gbetagamma subunits mediate Src-dependent phosphorylation of the epidermal growth factor receptor. A scaffold for G protein-coupled receptor-mediated Ras activation. J Biol Chem 272: 4637–4644, 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Luttrell LM, Hawes BE, van Biesen T, Luttrell DK, Lansing TJ, Lefkowitz RJ. Role of c-Src tyrosine kinase in G protein-coupled receptor- and Gbetagamma subunit-mediated activation of mitogen-activated protein kinases. J Biol Chem 271: 19443–19450, 1996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Marrero MB, Schieffer B, Paxton WG, Schieffer E, Bernstein KE. Electroporation of pp60c-src antibodies inhibits the angiotensin II activation of phospholipase C-gamma 1 in rat aortic smooth muscle cells. J Biol Chem 270: 15734–15738, 1995 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mukoyama M, Nakajima M, Horiuchi M, Sasamura H, Pratt RE, Dzau VJ. Expression cloning of type 2 angiotensin II receptor reveals a unique class of seven-transmembrane receptors. J Biol Chem 268: 24539–24542, 1993 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Pitcher JA, Touhara K, Payne ES, Lefkowitz RJ. Pleckstrin homology domain-mediated membrane association and activation of the beta-adrenergic receptor kinase requires coordinate interaction with G beta gamma subunits and lipid. J Biol Chem 270: 11707–11710, 1995 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ray PE, Bruggeman LA, Horikoshi S, Aguilera G, Klotman PE. Angiotensin II stimulates human fetal mesangial cell proliferation and fibronectin biosynthesis by binding to AT1 receptors. Kidney Int 45: 177–184, 1994 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Razandi M, Pedram A, Park ST, Levin ER. Proximal events in signaling by plasma membrane estrogen receptors. J Biol Chem 278: 2701–2712, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Schieffer B, Paxton WG, Chai Q, Marrero MB, Bernstein KE. Angiotensin II controls p21ras activity via pp60c-src. J Biol Chem 271: 10329–10333, 1996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Schuttert JB, Liu MH, Gliem N, Fiedler GM, Zopf S, Mayer C, Muller GA, Grunewald RW. Human renal fibroblasts derived from normal and fibrotic kidneys show differences in increase of extracellular matrix synthesis and cell proliferation upon angiotensin II exposure. Pflügers Arch 446: 387–393, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sekine S, Nitta K, Uchida K, Yumura W, Nihei H. Possible involvement of mitogen-activated protein kinase in the angiotensin II-induced fibronectin synthesis in renal interstitial fibroblasts. Arch Biochem Biophys 415: 63–68, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Selbie LA, King NV, Dickenson JM, Hill SJ. Role of G-protein beta gamma subunits in the augmentation of P2Y2 (P2U)receptor-stimulated responses by neuropeptide Y Y1 Gi/o-coupled receptors. Biochem J 328: 153–158, 1997 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Shajahan AN, Tiruppathi C, Smrcka AV, Malik AB, Minshall RD. Gbetagamma activation of Src induces caveolae-mediated endocytosis in endothelial cells. J Biol Chem 279: 48055–48062, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Smith RD, Baukal AJ, Dent P, Catt KJ. Raf-1 kinase activation by angiotensin II in adrenal glomerulosa cells: roles of Gi, phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase, and Ca2+ influx. Endocrinology 140: 1385–1391, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ushio-Fukai M, Alexander RW, Akers M, Lyons PR, Lassegue B, Griendling KK. Angiotensin II receptor coupling to phospholipase D is mediated by the betagamma subunits of heterotrimeric G proteins in vascular smooth muscle cells. Mol Pharmacol 55: 142–149, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Voisin L, Foisy S, Giasson E, Lambert C, Moreau P, Meloche S. EGF receptor transactivation is obligatory for protein synthesis stimulation by G protein-coupled receptors. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 283: C446–C455, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Wan Y, Kurosaki T, Huang XY. Tyrosine kinases in activation of the MAP kinase cascade by G-protein-coupled receptors. Nature 380: 541–544, 1996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Yiu WH, Pan CJ, Ruef RA, Peng WT, Starost MF, Mansfield BC, Chou JY. Angiotensin mediates renal fibrosis in the nephropathy of glycogen storage disease type Ia. Kidney Int 73: 716–723, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Zhang J, Pratt RE. The AT2 receptor selectively associates with Gialpha2 and Gialpha3 in the rat fetus. J Biol Chem 271: 15026–15033, 1996 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Zhou L, Xue H, Yuan P, Ni J, Yu C, Huang Y, Lu LM. Angiotensin AT1 receptor activation mediates high glucose-induced epithelial-mesenchymal transition in renal proximal tubular cells. Clin Exp Pharmacol Physiol 37: e152–e157, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Zhou Y, Sondek J, Harden TK. Activation of human phospholipase C-eta2 by Gbetagamma. Biochemistry 47: 4410–4417, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]