Abstract

Native aortic valve or its prosthetic valve endocarditis can extend to the adjacent periannular areas and erode into nearby cardiac chambers, leading to pseudoaneurysm and aorta-cavitary fistulas respectively. The later usually leads to acute cardiac failure and hemodynamic instability requiring an urgent surgical intervention. However rarely this might pass unnoticed and the patient might present later with cardiac murmur. Percutaneous device closure of aortic pseudoaneurysm, ruptured sinus of Valsalva aneurysm, aorta-pulmonary window, paravalvular leaks, and aorta-cavitary fistula have been reported. We present a 59-year-old female who developed a large aortic root pseudoaneurysm with biventricular communication aorta-cavitary fistulas presenting late following aortic prosthetic valve endocarditis. She underwent successful percutaneous device closure of her pseudoaneurysm and aorta-cavitary fistulas using two Amplatzer Duct Occluders. This case illustrates a challenging combination of aortic root pseudoaneurysm and biventricular aorta-cavitary fistulas that was successfully treated with percutaneous procedure.

Keywords: Pseudoaneurysm, Aorta-cavitary fistula, Device closure, Endocarditis

1. Introduction

Native aortic valve or its prosthetic valve endocarditis can invade the periannular tissue causing tissue destruction and abscess formation.1,2 This might lead to aortic pseudoaneurysm (PA) formation and more rarely erode into adjacent cardiac chambers, leading to an aorta-cavitary fistula (ACF).1,2 In a large study of infective endocarditis, cavitary fistula occurred in 2.2% of all endocarditis and 3.5% of prosthetic valve endocarditis.2 These PA and ACF are generally treated surgically.3,4 Of late, cases of percutaneous device closure of both ascending aortic and aortic root PA is reported.5,6 In addition, percutaneous device closure of ruptured sinus of Valsalva aneurysm, aorta-pulmonary window, paravalvar leaks, and ACF have been reported.7–11 We present a challenging case of aortic prosthetic valve endocarditis with a large aortic root PA with biventricular communication which underwent successful percutaneous device closure.

2. Case report

A 59-year-old female, hypertensive, non-diabetic with history of prosthetic aortic valve replacement (21 Carbomedic mechanical valve) implanted 12 years earlier for severe aortic stenosis, presented to a regional hospital with fever. Prior to this presentation she was doing well on daily warfarin therapy and a target INR of 2.5 with an annual echocardiogram showing normally functioning prosthetic valve with good left ventricular (LV) systolic function. She presented with persistent fever of 38 °C and all the three blood cultures taken grew Beta Hemolytic Streptococci. Clinically she was not in heart failure and there were no signs of infective endocarditis. Her ECG showed sinus rhythm with normal intervals. She underwent transthoracic and a transesophageal echocardiogram (TTE/TEE) at the regional hospital which reported normally functioning prosthetic valve and a suspicious tricuspid valve vegetation. She was treated with 2 weeks of gentamycin and 4 weeks of ceftriaxone with fever subsiding over 2–3 weeks period and was discharged. After 4 weeks of discharge she was seen in cardiology clinic at our institute and she was doing well with no symptoms. However, clinical auscultation revealed a precordial grade 3/6 continuous murmur. Prosthetic valve clicks were well heard. There were no signs of heart failure.

A TTE/TEE done in our institute demonstrated non dilated chambers with prosthetic aortic valve-in-situ with peak and mean gradient of 39 and 20 mmHg, respectively. There was no significant valvar leak. There was a large paravalvar PA adjacent to the right coronary cusp measuring 2.8 × 1.0 cm communicating with right ventricle (RV) and LV (Fig. 1A, B and C, arrowheads). There was no clear-cut ventricular septal defect noted. She underwent CT angiogram of aorta which confirmed TEE findings with demonstration of a large aortic root PA involving anterior sinus extending from just next to aortic prosthesis at the level of annulus with a tract communicating this PA to the RV and LV (Fig. 2 A, B and C, arrowheads). She was offered percutaneous device closure or high risk surgery, but the patient and family needed time for discussion and finally elected an attempt of percutaneous device closure. Hence she underwent percutaneous device closure 4 months after index event.

Fig. 1.

Transesophageal echocardiogram (TEE) showing a large aortic root pseudoaneurysm involving right coronary cusp extending from aortic valve prosthesis in a patient with aortic valve prosthetic endocarditis (A, arrowheads). Note pseudoaneurysm to biventricular fistulous connection (B, arrowheads) with color Doppler flow across these fistulous tracts (C, arrowheads). LA, Left atrium; RA, Right atrium; LV, Left ventricle; RV, Right ventricle; AO, Aorta; AVP, Aortic valve prosthesis.

Fig. 2.

Computed Tomography scan of chest demonstrating a large aortic root paravalvular pseudoaneurysm in a patient with aortic valve prosthetic endocarditis (A, arrowheads). Note pseudoaneurysm to left and right ventricular fistula connections (B and C, arrowheads, respectively).

The procedure was done under general anesthesia along with fluoroscopy and TEE guidance. 6000 IU of unfractionated heparin was given intravenously. The right femoral artery and vein (7F) and left femoral artery (6F) accesses were obtained. Ascending aortic angiogram was performed with a pigtail catheter (5F) from the left femoral artery access, which demonstrated a large PA with a narrow neck from aorta along with a 10 mm LV (Fig. 3A, arrowheads) and a 5 mm RV fistulous communications (Fig. 3B, arrowheads). The prosthetic valve ring was forming the superior medial wall of the PA and the roof of the PA-LV communication. The LV fistula connection was crossed with right Judkins catheter to the LV through the PA. Then a coronary wire was placed and the catheter was removed. A 12 × 40 mm Tyshak II balloon (NuMED, Hopkinton, New York) was used to confirm the size of the PA-LV connection (Fig. 3C). The right Judkins catheter and a 260 cm 0.035″ Terumo wire (Terumo Medial Corp., Somerset, NJ) were used to cross the PA to the RV fistula and subsequently advanced to the left pulmonary artery. A 5F Swan–Ganz catheter was advanced from the venous access to the left pulmonary artery. This was advanced through the tricuspid valve while its balloon was inflated. The Swan–Ganz catheter was replaced with 6F Multipurpose catheter (Cordis Corp., Miami Lakes, FL). The Terumo wire was snared out of right femoral vein to establish a stable “arteriovenous loop” using 15 mm PFM snare through the Multipurpose catheter.

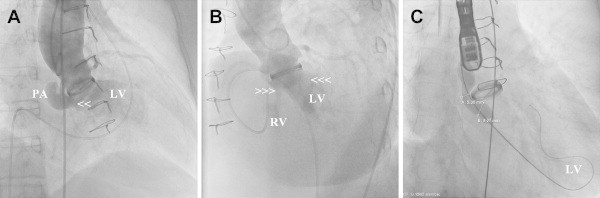

Fig. 3.

Aortogram demonstrates paraprosthetic kidney shaped pseudoaneurysm with fistulous connection to left ventricle (A, arrowheads) and right ventricle (B, right arrowheads) in a patient with aortic valve prosthetic endocarditis. (C) Fluoroscopy demonstrating balloon sizing of the pseudoaneurysm neck measuring 5 mm and the PA to left ventricular fistula connection measuring 10 mm. LV, Left ventricle; RV, Right ventricle; PA, pseudoaneurysm.

Venous introducer was removed and a 7F Amplatzer Duct Occluder I (ADO I) delivery sheath (AGA medical corporation, Golden Valley, MN) was then passed over the guide wire from the right femoral vein into the RV and into the PA. The dilator and the wire were then removed. A 16/14 mm ADO I device (AGA Medical Corporation, Golden Valley, Minneapolis, USA) was advanced via this system. Under fluoroscopic and TEE guidance the delivery system was gradually withdrawn until the aortic disc of the ADO device was deployed in the PA and the pulmonary disc deployed in the RV checking that prosthetic valve function was not blocked (Fig. 4A, arrowheads). Aortic root angiogram through pigtail catheter demonstrated no flow across the PA to RV as well as PA to LV fistulas, essentially blocking both fistulous connections (Fig. 4B, arrowheads). From right femoral artery approach, a 6F Multipurpose catheter was passed into the PA and exchanged with 7F ADO I delivery sheath. A second ADO I 12/10 mm device as advanced and the aortic disc were deployed in the PA interlocking the first device and the pulmonary disc was deployed into the PA-ascending aorta connection (Fig. 4C, arrowheads). Repeated angiogram in the ascending aorta was done to ensure the proper positions of the two devices with no interference to the prosthetic valve function. When this was ensured the devices were released (Fig. 5A, arrowheads). TEE demonstrated aortic disc of both devices inside the PA with a tiny flow into the PA from aortic end but no flow across the PA to RV or LV (Fig. 5B, arrowheads). The post procedure recovery was uneventful. TTE done post procedure next day showed both devices in situ with no flow or leak and normally functioning aortic prosthetic valve and native mitral valve. Patient was discharged after adjusting her warfarin dose. At 6 months follow up patient was doing well with TTE findings similar to post procedure findings.

Fig. 4.

Fluroscopy showing the deployment of Amplatzer Duct Occluder I (ADO I) aortic disc in the paravalvular pseudoaneurysm and the pulmonary disc into the right ventricle (A, arrowheads). (B) Control aortography showing complete occlusion of the aortic paravalvular pseudoaneurysm to right ventricular as well as left ventricular fistula connections. (C) A second ADO I device (C, right arrowheads) as advanced from right femoral artery and the aortic disc was deployed in the pseudoaneurysm interlocking the first device and the pulmonary disc was deployed into the pseudoaneurysm-ascending aorta connection.

Fig. 5.

(A) Fluoroscopy demonstrating released two Amplatzer Duct Occluder I (ADO I) devices inside a paravalvular pseudoaneurysm with biventricular fistulas occluding both the fistulous tracts. (B) TEE demonstrating both the ADO I devices inside the paravalvular pseudoaneurysm (arrowheads) thus excluding the pseudoaneurysm as well as the biventricular fistula connections. LA, Left atrium; RA, Right atrium; AO, Aorta.

3. Discussion

Anguera et al reported that 60% of ACF present with acute cardiac failure and hemodynamic instability requiring an urgent surgical intervention.2 While PA may be asymptomatic with incidental finding on an imaging study or may present symptomatically (compression of surrounding structures) either during an acute episode (of endocarditis or post-surgery) or months to years later.3,4 This patient probably had aortic root abscess initially that was not picked up, which later formed PA with biventricular fistulas. However, patient was asymptomatic. In diagnosing PA and ACF various imaging modalities are described including echocardiography, computed tomography, magnetic resonance imaging and conventional angiography which are complimentary to each other as observed in this patient to detect exact pathology.1–4

Aortic PA may rupture into cardiac chamber with fistula formation; the site of origin of the fistulous tract is equally distributed between the three sinuses of Valsalva and the four cardiac chambers are also equally involved as receiving chambers.1,2 Even though, surgery is generally indicated in aortic PA with or without fistula, recently in non-surgical candidates, percutaneous device closure of ascending aortic/aortic root PA as well as pathologies like ruptured sinus of Valsalva aneurysm, aorta-pulmonary window, paravalvular leaks, and aorta-cavitary fistula have been reported.5–11 In majority of these rare cases Amplatzer Duct Occluder (AGA Medical Corporation) which is commonly used for transcatheter occlusion of a moderate to large patent arterial duct is useful as demonstrated in this patient. The advantage of this device as noted by Lebreiro et al is the ‘windsock’ like morphology of the device with a broader aortic end which is best suited for excluding these type of PA and simultaneously closing ACF which usually have narrow necks.11 This case was unusually having a large PA along with dual ventricular communication; wide communication between the PA and the LV and a small communication to RV. It represented a technical challenge to us because of its wide opening to LV with absence of any native tissue between it and the prosthetic valve ring as well as between the later and the paravalvar fistulous leaks. A large device from aortic side would have interfered with prosthetic valve function and a small device might have embolized to LV. However our approach of oversizing the device and to occlude PA-RV fistula first secured and excluded the PA-LV connection and provided a support for the second device deployment and stability. Both these devices aortic discs filled most of the PA cavity and sealed the PA-LV connection while the pulmonary artery disc from each device occluded the PA-RV and PA-ascending aorta connections accordingly. Therefore we demonstrated that in a single sitting percutaneous closure of a complex biventricular communicating ACF is feasible, safe and effective using multiple ADO I devices without causing interference to the prosthetic aortic valve function.

In conclusion, this case illustrates a challenging combination of paraprosthetic aortic PA with multiple communications of ACF that was successfully treated with percutaneous procedure using two Amplatzer Duct Occluders. In these kinds of PA and fistulas we recommend use of this device as an alternative to surgery. However, long term follow up of these patients is needed.

Conflicts of interest

All authors have none to declare.

References

- 1.Kanemitsu S., Tanabe S., Ohue K., Miyagawa H., Miyake Y., Okabe M. Aortic valve destruction and pseudoaneurysm of the sinus of valsalva associated with infective endocarditis. Ann Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2010;16:142–144. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Anguera I., Miro J.M., Vilacosta I. Aorto-cavitary fistulous tract formation in infective endocarditis: clinical and echocardiographic features of 76 cases and risk factors for mortality. Eur Heart J. 2005;26:288–297. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehi034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Katayama Y., Minato N., Sakaguchi M., Nakashima A., Hisajima K. Surgical treatment of pseudoaneurysm of the sinus of valsalva after aortic valve replacement for active infective endocarditis. Ann Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2005;11:419–423. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hori D., Noguchi K., Nomura Y., Tanaka H. Perivalvular pseudoaneurysm caused by streptococcus dysgalactiae in the presence of prosthetic aortic valve endocarditis. Ann Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2012;18:262–265. doi: 10.5761/atcs.cr.11.01750. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Agarwal M., Ray M., Pallavi M. Device occlusion of pseudoaneurysm of ascending aorta. Ann Pediatr Cardiol. 2011;4:195–199. doi: 10.4103/0974-2069.84675. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fine N.M., Booker J.D., Pislaru S.V., Williamson E.E., Rihal C.S. Percutaneous device closure of a large aortic root graft pseudoaneurysm using 3-dimensional transesophageal echocardiographic guidance. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2011;58:e33. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2011.03.071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kerkar P., Lanjewar C., Mishra N., Nyayadhish P., Mammen I. Transcatheter closure of ruptured sinus of valsalva aneurysm using the amplatzer duct occluder: immediate results and midterm follow-up. Eur Heart J. 2010;31:2881–2887. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehq323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Trehan V., Nigam A., Tyagi S. Percutaneous closure of nonrestrictive aortopulmonary window in three infants. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv. 2008;71:405–411. doi: 10.1002/ccd.21366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rihal C.S., Sorajja P., Booker J.D., Hagler D.J., Cabalka A.K. Principles of percutaneous paravalvular leak closure. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2012;5:121–130. doi: 10.1016/j.jcin.2011.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Khoury A., Khatib I., Halabi M., Lorber A. Transcatheter closure of ruptured right-coronary aortic sinus fistula to right ventricle. Ann Pediatr Cardiol. 2010;3:178–180. doi: 10.4103/0974-2069.74052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lebreiro A.M., Silva J.C. Transcatheter closure of an iatrogenic aorto-right ventricular fistula. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv. 2012;79:448–452. doi: 10.1002/ccd.23222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]