Abstract

Objective

To compare the effectiveness of mobile phone text messaging and that of traditional health worker training in communicating clinical recommendations to health workers in China.

Methods

A cluster-randomized controlled trial (Chinese Clinical Trial Register: ChiCTR-TRC-09000488) was conducted in 100 township health centres in north-western China between 17 October and 25 December 2011. Health workers were allocated either to receive 16 text messages with recommendations on the management of viral infections affecting the upper respiratory tract and otitis media (intervention group, n = 490) or to receive the same recommendations through the existing continuing medical education programme – a one-day training workshop (control group, n = 487). Health workers’ knowledge of the recommendations was assessed before and after messaging and traditional training through a multiple choice questionnaire. The percentage change in score in the control group was compared with that in the intervention group. Changes in prescribing practices were also compared.

Findings

Health workers’ knowledge of the recommendations increased significantly in the intervention group, both individually (0.17 points; 95% confidence interval, CI: 0.168–0.172) and at the cluster level (0.16 points; 95% CI: 0.157–0.163), but not in the control group. In the intervention group steroid prescriptions decreased by 5 percentage points but antibiotic prescriptions remained unchanged. In the control group, however, antibiotic and steroid prescriptions increased by 17 and 11 percentage points, respectively.

Conclusion

Text messages can be effective for transmitting medical information and changing health workers' behaviour, particularly in resource-limited settings.

Résumé

Objectif

Comparer l'efficacité du texting par téléphone portable et celle de la formation traditionnelle des professionnels de la santé en matière de communication des recommandations cliniques aux professionnels de la santé en Chine.

Méthodes

Un essai contrôlé randomisé par grappes (numéro d'enregistrement des essais cliniques chinois: ChiCTR-TRC-09000488) a été mené dans 100 centres de santé communaux dans le nord-ouest de la Chine entre le 17 octobre et le 25 décembre 2011. Les professionnels de la santé ont reçu soit 16 messages textuels contenant des recommandations sur la gestion des infections virales affectant les voies respiratoires supérieures et des otites moyennes (groupe d'intervention, n = 490), soit les mêmes recommandations, mais par le biais du programme de formation continue médicale existant – un atelier de formation d'une journée (groupe témoin, n = 487). Les connaissances des professionnels sur ces recommandations ont été évaluées avant et après la réception des messages textuels et la formation traditionnelle par le biais d'un questionnaire à choix multiples. La variation en pourcentage du score obtenu par le groupe témoin a été comparée à celle du groupe d'intervention. Les changements dans les pratiques de prescription ont également été comparés.

Résultats

Les connaissances des professionnels de la santé sur les recommandations ont augmenté significativement dans le groupe d'intervention, à la fois individuellement (0,17 point; intervalle de confiance de 95%, IC de 95%: 0,168–0,172) et au niveau de la grappe (0,16 point; IC de 95%: 0,157–0,163), mais pas dans le groupe témoin. Dans le groupe d'intervention, les prescriptions de stéroïdes ont diminué de 5 points de pourcentage, mais les prescriptions d'antibiotiques sont restées constantes. Dans le groupe témoin cependant, les prescriptions d'antibiotiques et de stéroïdes ont augmenté respectivement de 17 et 11 points de pourcentage.

Conclusion

Les messages textuels peuvent être efficaces pour transmettre des informations médicales et changer le comportement des professionnels de la santé, en particulier dans les endroits où les ressources sont limitées.

Resumen

Objetivo

Comparar la eficacia de los mensajes de texto por teléfono móvil y la de la formación tradicional del personal sanitario en la comunicación de las recomendaciones clínicas al personal sanitario en China.

Métodos

Se llevó a cabo un ensayo controlado aleatorio de grupos (registro chino de ensayos clínicos: ChiCTR-TRC-09000488) en 100 centros de salud de municipios situados en el noroeste de China entre el 17 de octubre y el 25 diciembre de 2011. Se determinó que el personal sanitario recibiría bien 16 mensajes de texto con recomendaciones sobre el tratamiento de las infecciones víricas que afectan a las vías respiratorias superiores y otitis media (grupo de intervención, n = 490) o bien las mismas recomendaciones a través del programa de educación médica continua existente - un taller de capacitación de un día de duración (grupo de control, n = 487). Los conocimientos del personal sanitario se evaluaron antes y después del envío de los mensajes de texto y de la formación tradicional por medio de un cuestionario de respuestas múltiples. Se comparó el porcentaje de cambio en la puntuación del grupo de control con el del grupo de intervención, así como los cambios en las prácticas de prescripción.

Resultados

El conocimiento del personal sanitario acerca de las recomendaciones aumentó significativamente en el grupo de intervención, tanto a nivel individual (0,17 puntos, IC del 95%: 0,168–0,172) como a nivel del grupo (0,16 puntos; intervalo de confianza del 95%: 0,157–0,163), pero no en el grupo de control. En el grupo de intervención, las prescripciones de esteroides disminuyeron en 5 puntos porcentuales, aunque las de antibióticos no presentaron cambios. En el grupo de control, sin embargo, aumentaron las prescripciones de esteroides y de antibióticos en, respectivamente, 17 y 11 puntos porcentuales.

Conclusión

Los mensajes de texto pueden ser eficaces para transmitir información médica y cambiar el comportamiento del personal sanitario, especialmente en entornos con recursos limitados.

ملخص

الغرض

مقارنة فعالية الرسائل النصية عبر الهواتف المحمولة بفعالية التدريب التقليدي للعاملين الصحيين في نقل التوصيات السريرية إلى العاملين الصحيين في الصين.

الطريقة

تم إجراء تجربة عشوائية عنقودية في بيئة مراقبة (سجل التجارب السريرية الصيني: ChiChiCTR-TRC-09000488) في 100 مركز صحيً بالمدن في شمال غرب الصين في الفترة من 17 تشرين الأول/ أكتوبر إلى 25 كانون الأول/ ديسمبر 2011. وتم تخصيص العاملين الصحيين إما لتلقي 16 رسالة نصية تتضمن توصيات بشأن التدبير العلاجي للعدوى الفيروسية التي تؤثر على المسالك التنفسية العلوية والتهاب الأذن الوسطى (فئة التدخل، العدد = 490) أو لتلقي التوصيات ذاتها من خلال برنامج التعليم الطبي المستمر القائم - حلقة عمل تدريبية لمدة يوم واحد (الفئة الشاهدة، العدد = 487). وتم تقييم معرفة العاملين الصحيين بالتوصيات قبل وبعد تسليم الرسائل والتدريب التقليدي من خلال استبيان متعدد الخيارات. وتم مقارنة تغير النسبة المئوية في الدرجة المحققة في الفئة الشاهدة بالتغير في فئة التدخل. وتم كذلك مقارنة التغيرات في ممارسات وصف الأدوية.

النتائج

زادت معرفة العاملين الصحيين بالتوصيات على نحو كبير في فئة التدخل، على نحو فردي (0.17 نقطة؛ فاصل الثقة 95 % فاصل الثقة: من 0.168 إلى 0.172) وكذلك على المستوى العنقودي (0.16 نقطة؛ فاصل الثقة 95 %، فاصل الثقة: من 0.157 إلى 0.163)، ولكنها لم تزد في الفئة الشاهدة. وانخفضت وصفات الستيرويدات في فئة التدخل بمقدار 5 نقاط مئوية ولكن وصفات المضادات الحيوية ظلت دون تغيير. ومع ذلك، زادت وصفات المضادات الحيوية والستيرويدات في الفئة الشاهدة بمقدار 17 و11 نقطة مئوية، على التوالي.

الاستنتاج

من الممكن أن تكون الرسائل النصية فعالة في إرسال المعلومات الطبية وتغيير سلوكيات العاملين الصحيين، لاسيما في البيئات محدودة الموارد.

摘要

目的

比较手机短信和传统继续医学教育方式在培训医务工作者利用循证推荐意见方面的有效性。

方法

2011年10月17日至12月25日期间,在中国西北100所乡镇卫生院实施群随机对照试验(中国临床试验注册中心 :ChiCTR-TRC-09000488)。将医务工作人员分为两组,一组接收有关影响上呼吸道病毒感染和中耳炎的循证推荐意见(干预组,n = 490),另一组通过现有的继续医学教育方式(为期一天的培训班)接收同样的推荐意见(对照组,n = 487)。通过多项选择问卷调查评估发送短消息和传统培训前后医务工作者在推荐意见方面的知识。将对照组的分数百分比变化与干预组进行比较。另外还比较了两组医疗实践处方在干预前后的变化。

结果

干预组中卫生工作者在个人(0.17分;95% CI:0.168–0.172)和群组层面(0.16分;95% CI:0.157–0.163)上在循证推荐意见方面的知识都显著增加,但对照组则没有。在干预组,类固醇处方数量减少5个百分点,但抗生素处方无变化。但在对照组,抗生素和类固醇处方分别增加17和11个百分点。

结论

短信对于传播医学推荐意见和改变医务工作者行为来说可能行之有效,在资源有限的国家和地区尤其如此。

Резюме

Цель

Сравнить эффективность передачи клинических рекомендаций медицинским работникам в Китае путем отправки текстовых сообщений на мобильный телефон и путем традиционного обучения работников здравоохранения.

Методы

Кластерное рандомизированное контролируемое исследование (номер в Реестре клинических исследований Китая: ChiCTR-TRC-09000488) проводилось в 100 поселковых медицинских центрах на северо-западе Китая в период с 17 октября по 25 декабря 2011 года. В ходе исследования медицинские работники должны были либо получить 16 текстовых сообщений с рекомендациями по лечению среднего отита и вирусных инфекций в области верхних дыхательных путей (экспериментальная группа, n = 490), либо получить те же рекомендации через существующую программу медицинского образования в виде однодневного учебного семинара (контрольная группа, n = 487). Знание работниками здравоохранения рекомендаций оценивалось с помощью многовариантного вопросника до и после получения сообщений и прохождения традиционного обучения . После чего процентное изменение в баллах в контрольной группе сравнивалось с изменениями в экспериментальной группе. Также сравнивались изменения в назначенном лечении.

Результаты

Знание работниками здравоохранения рекомендаций значительно увеличилось в экспериментальной группе, как индивидуально (0,17 пункта; 95% ДИ: 0,168–0,172), так и на уровне кластера (0,16 пункта; 95% доверительный интервал, ДИ: 0,157–0,163), в отличие от контрольной группы. В экспериментальной группе назначение стероидных препаратов снизилось на 5 процентных пунктов, а назначение антибиотиков осталось без изменений. В контрольной группе, напротив, назначение антибиотиков и стероидных препаратов увеличилась на 17 и 11 процентных пунктов соответственно.

Вывод

Текстовые сообщения могут быть эффективным средством для передачи медицинской информации и изменения рецептурной практики работников здравоохранения, особенно в условиях ограниченных ресурсов.

Introduction

Health workers in rural China do not receive systematic, qualified medical education and training1,2 because, unlike their urban counterparts, they face constraints such as inadequacies in transport and funding and they are largely unaware of the need for education.3,4 Gansu Province has 16 853 health workers (including family physicians, nurses, public health practitioners, pharmacists, midwives and laboratory technicians) in 1333 township health centres, distributed across 14 regions.5 Most of the health centres are located in remote mountainous areas, and thus providing continuing medical education to these health workers is a major challenge.6

Mobile text messages have been used to improve health outcomes in a wide range of contexts because of their low cost and convenience.7,8 For instance, text messages have been used in health programmes for smoking cessation,9 disease management10–12 and weight reduction13 and to improve adherence to medication14 and attendance at health-care appointments.15 Since Chinese mobile phone users send high volumes of messages – 79 billion messages, equivalent to 73 per user – in September 2012 alone16 – we hypothesized that such messages could be useful for communicating medical information to rural health workers in China.

In general, text messages seem to be effective for communicating information in a health-care context and have been well accepted by users.17,18 Research also indicates that text messages could serve as a powerful tool for behaviour change,19–21 both in developed and developing countries.22 However, so far research has focused almost exclusively on the sending of health messages to patients rather than to health workers, and on the use of messages as patient reminders rather than for the delivery of evidence-based information. In this study, we tested whether text messages sent to rural health workers containing evidence-based recommendations could improve knowledge and influence prescribing medical practice.

Methods

Study design, participants and recruitment

The study was undertaken in the Gansu province in north-western China from 17 October to 25 December 2011. It was designed as a “before” and “after” randomized controlled trial. The intervention group was sent text messages on the management of viral infections affecting the upper respiratory tract and otitis media, and the control group was given the same messages in the context of a regular continuing medical education programme. In preparation for the trial, we undertook several surveys and conducted two pilot studies in seven health centres in Gaolan county, Gansu province, between November 2009 and April 2011. Information on these pilot studies, which were conducted to choose the best content and delivery of the text messages and to conduct a power analysis for the trial, can be obtained from the corresponding author on request.

To be eligible for recruitment individuals had to be health workers in a township health centre in Gansu province. The term “health worker” was used broadly to include family physicians, nurses, public health practitioners, pharmacists, midwives and laboratory technicians. Only physicians could prescribe drugs, but other health workers were also sent text messages because of their potential influence on physician behaviour. In addition, the pilot studies showed that confining text messages to physicians made other health workers feel excluded. Health workers who did not own a mobile phone or whose mobile phone could not receive text messages were excluded from the trial.

Sample size

The power calculations were based on the results of two pilot studies and the formula outlined by Donner and Klar23 for cluster randomized trials with a binary study outcome. The analysis of variance estimator of the intra-cluster correlation coefficient was calculated as 0.15. We initially calculated the minimum sample size to be 76 health centres with a total of 742 participants, allowing for a 40% loss-to-follow-up. However, in light of higher rates of loss to follow-up in the pilot studies, we increased the number of health centres to 100 to improve statistical power.

Randomization

We used the health centre as the unit of randomization. A cluster design was used to avoid biases arising from the possible conveyance of information by members of the intervention group to members of the control group if both were located at the same health centre. Randomization was done in two stages. First, with the help of the health administration department of Gansu province, we sent invitation letters to all 1333 health centres in Gansu province. By the deadline, 163 health centres had agreed to participate in our study. From these centres we randomly selected 100 for inclusion in the trial; we then used a computer-generated random sequence to select the clusters for intervention. To minimize the potential for selection bias, cluster allocation was masked from statisticians until the analyses were completed.

The intervention

For the main trial, we created 18 text messages. Of these messages, 16 contained evidence-based recommendations for the management of the infections affecting the upper respiratory tract and middle ear that are most common in rural Gansu – the common cold, influenza, pharyngitis, tonsillitis – and of otitis media, a frequent complication of upper respiratory infections. The recommendations were mainly sourced from Clinical evidence24 and the Cochrane Library.25,26 Senior physicians from the First Hospital of Lanzhou University revised the language of the recommendations to ensure that health workers in rural areas could understand the messages clearly. All text messages were within 280 Chinese characters in length, the maximum for most mobile phones in China.

The intervention was carried out from 15 November to 24 December 2011. A computer sent the text messages to the intervention group three times a week (on Tuesdays, Thursdays and Saturdays) at 20:30. The control group received the recommendations through the traditional method, a one-day training programme delivered by two senior physicians from the First Hospital of Lanzhou University, held on 3 December 2011.

Data collection

Health workers were interviewed by telephone and asked questions to test their knowledge of disease management – for the five selected acute respiratory conditions – before and after the intervention and the traditional training workshop. The difference between the intervention and control group in the percentage point change in average test score was the main study outcome. A secondary outcome was the difference between the intervention and control group, expressed in percentage points, in the average number of antibiotic and steroid prescriptions issued by family physicians.

Telephone surveys were conducted on 5 and 6 November 2011 (before the intervention) and on 24 and 25 December 2011 (after the intervention) using a computer-assisted telephone interviewing system based on random dialing. Participants were asked 10 multiple-choice questions on the appropriate treatment of the selected diseases and complications. All questions were scored as one point per correct response and zero points for an incorrect response. We assumed that scores reflected health workers’ ability to identify the appropriate action when confronted with a specific medical problem. Scores were averaged as a percentage of questions answered correctly at both the individual and cluster level. An additional questionnaire was administered to record participant satisfaction with both the intervention and the educational methods used in the control group.

To assess family physicians’ prescription practices, random sampling using a computer-generated randomization procedure was used to select 10 health centres in each cluster for the collection of prescriptions. Investigators then collected drug prescriptions for upper respiratory infections in these health centres from 1 December 2011 to 28 February 2012. As a comparator, they also obtained the prescriptions issued over the same period one year before the trial (i.e. from 1 December 2010 to 28 February 2011). Prescriptions for upper respiratory infections were chosen for the trial because: (i) viral infections affecting the upper respiratory tract are very common in rural China, especially during late autumn and winter; (ii) health workers at township health centres often inappropriately prescribe antibiotics and steroids for these viral infections.27,28

Statistical analysis

Analysis was by intention to treat. All statistical analyses were conducted using SAS software, version 9.2 (SAS Institute, Cary, USA). At the cluster level, we calculated the average knowledge score for each cluster (i.e. health centres) and used it as the outcome. An independent t-test was conducted to compare the difference in average scores between the intervention and control groups, with a 95% CI of the average score difference. At the individual level, a linear mixed model (mixed procedure in SAS) was performed to evaluate the intervention effect. The cluster was chosen as a random effect to account for the dependence of individuals within the same cluster. The model contained the study groups (intervention versus control), sex and baseline score as fixed effects. Missing values were entered by the cluster mean input method.29 Sensitivity analysis was performed by analysing the observed outcomes only. Statistical significance was defined as P < 0.05.

Ethics and consent

The trial was registered with the Chinese Clinical Trial Register on 15 August 2009 (registration number ChiCTR-TRC-09000488) and received approval by the Chinese Ethics Committee of Registering Clinical Trials (ChiECRCT-2012026). Informed consent was obtained via telephone survey and all calls were recorded automatically by the computer-assisted telephone interviewing system.

Results

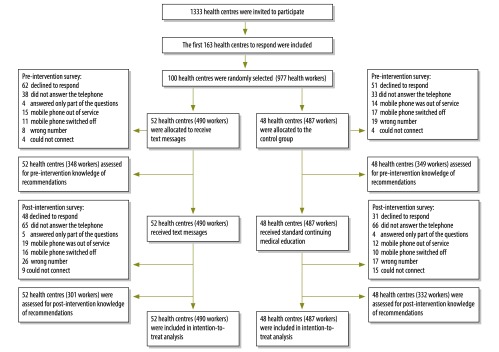

Of the 1333 health centres invited to participate in the trial, 163 health centres agreed, and of these 100 were chosen at random and allocated either to the intervention group (490 health workers at 52 health centres) or the control group (487 health workers at 48 health centres) (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Flowchart showing the selection of participants for study on the use of text messaging to communicate clinical recommendations to health workers, Gansu province, China, 2011

The first telephone survey to assess knowledge of the recommendations before the intervention was successfully conducted with 348 people in the intervention group, and 349 in the control group. The second telephone survey to assess knowledge after the intervention was successfully completed with 301 people in the intervention group, and 332 in the control group. An analysis of baseline characteristics showed no statistically significant differences between the two groups (Table 1).

Table 1. Baseline characteristics of health workers in study on the use of text messaging to communicate clinical recommendations to health workers, Gansu province, China, 2011.

| Demographic characteristics | First telephone survey |

Second telephone survey |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control group (n = 349) | Intervention group (n = 348) | Control group (n = 332) | Intervention group (n = 301) | ||

| Mean age, in years (SD) | 31.59 (8.30) | 31.18 (8.09) | 32.32 (8.47) | 31.68 (8.98) | |

| Mean length of service, in years (SD) | 8.15 (9.08) | 7.94 (8.64) | 8.88 (9.31) | 8.44 (9.67) | |

| Sex, no. (%) | |||||

| Male | 234 (67.0) | 237 (68.1) | 225 (67.8) | 207 (68.8) | |

| Female | 115 (33.0) | 111 (31.9) | 107 (32.2) | 94 (31.2) | |

| Type of health centre, no. (%) | |||||

| General | 32 (66.7) | 32 (61.5) | 32 (68.1) | 37 (71.2) | |

| Key | 16 (33.3) | 20 (38.5) | 15 (31.9) | 15 (28.8) | |

| Health workers, by type of health centre, no. (%) | |||||

| General | 212 (60.7) | 197 (56.6) | 203 (61.1) | 198 (65.8) | |

| Key | 137 (39.3) | 151 (43.4) | 129 (38.9) | 103 (34.2) | |

| Health worker grade,a no. (%) | |||||

| Senior | 11 (3.15) | 3 (0.9) | 9 (2.7) | 3 (1.0) | |

| Intermediate | 57 (16.33) | 45 (12.93) | 60 (18.1) | 50 (16.7) | |

| Junior | 174 (49.86) | 199 (57.18) | 172 (52.0) | 161 (53.7) | |

| Other | 63 (18.05) | 59 (16.95) | 53 (16.0) | 59 (19.7) | |

| Unclear | 44 (12.61) | 42 (12.07) | 37 (11.2) | 27 (9.0) | |

| Medical training, no. (%) | |||||

| Undergraduate | 97 (30.0) | 87 (25.0) | 100 (30.1) | 73 (24.3) | |

| Post-secondary education | 209 (60.0) | 212 (60.9) | 190 (57.2) | 180 (60.0) | |

| Vocational and technical education | 43 (10.0) | 49 (14.1) | 42 (12.6) | 47 (15.7) | |

| Family physicians, no.(%) | 204 (58.5) | 183 (52.6) | 200 (60.2) | 160 (53.2) | |

| Other health workers, no. (%) | 145 (41.5) | 165 (47.4) | 132 (39.8) | 141 (46.8) | |

SD: standard deviation.

a This refers to the category of title obtained after passing a qualifying test. “Other” includes non-physicians, primarily public health workers engaged in disease prevention and control and allied health professionals, who are usually medical technicians.

After receiving text messages, the average score in the intervention group increased significantly more than in the control group, both at the cluster and the individual level (Table 2). In subgroup analyses, family physicians’ scores in the intervention group increased significantly more than scores in the control group, both individually and at the cluster level (Table 2).

Table 2. Average scores obtained by health workers, at the cluster and individual level, on knowledge of the management of viral infections affecting the upper respiratory tract and middle ear, Gansu province, China, 2011.

| Health worker type | Average scorea, mean (SD) |

Differenceb (95% CI) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| First telephone survey |

Second telephone survey |

|||||

| Control group | Intervention group | Control group | Intervention group | |||

| Allc | (n = 487) | (n = 490) | (n = 487) | (n = 490) | ||

| Cluster level | 0.33 (0.07) | 0.32 (0.6) | 0.32 (0.06) | 0.47 (0.08) | 0.16 (0.157–0.163) | |

| Individual level | 0.33 (0.13) | 0.32 (0.12) | 0.31 (0.11) | 0.47 (0.16) | 0.17 (0.168–0.172) | |

| Family physiciansc | (n = 236) | (n = 243) | (n = 236) | (n = 243) | ||

| Cluster level | 0.35 (0.08) | 0.32 (0.9) | 0.32 (0.07) | 0.45 (0.12) | 0.16 (0.158–0.162) | |

| Individual level | 0.34 (0.13) | 0.33 (0.12) | 0.31 (0.11) | 0.46 (0.16) | 0.16 (0.149–0.171) | |

CI: confidence interval; SD: standard deviation.

a A correct response received 1 point; an incorrect response received 0 points.

b This represents the difference between the intervention and control group in change in average test score between surveys. For example, the difference for all health workers at the cluster level (0.16) was calculated by subtracting the difference in the control group from the difference in the intervention group, as follows (0.47 − 0.32) − (0.32 − 0.33).

c Missing values are imputed.

In the intervention group, no change in the prescription of antibiotics was found; however, prescriptions for steroids fell by 21 percentage points (Table 3). In the control group, prescriptions for antibiotics and steroids increased by 17 and 11 percentage points, respectively.

Table 3. Changes in antibiotic and steroid prescriptions in the control and intervention groups of study on the use of text messaging to communicate clinical recommendations to health workers, Gansu province, China, 2011 .

| Period | No./total (%) |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intervention group |

Control group |

||||

| Antibiotics | Steroids | Antibiotics | Steroids | ||

| 1 Dec 2010 to 28 Feb 2011 | 681/999 (68) | 242/999 (24) | 153/306 (50) | 17/306 (6) | |

| 1 Dec 2011 to 28 Feb 2012 | 568/831 (68) | 154/831 (19) | 299/446 (67) | 76/446 (17) | |

| Percentage point differencea (95% CI) | 0 (0) | −5 (−2 to −9) | +17 (10 to 24) | +11 (7 to 16) | |

CI: confidence interval; Dec: December; Feb: February.; Dec: December.

During the follow-up survey on attitudes towards the text messages containing evidence-based recommendations, one third of the health workers in the intervention group reported that they frequently adopted the recommendations in their clinical decision-making and 95% wanted to continue receiving the text messages (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Attitudes towards text messaging as a means of communicating clinical recommendations to health workers,a Gansu province, China, 2011

a The number of respondents varies slightly for each question because some respondents failed to respond to all questions.

b The degree to which the recommendation is credible or evidence-based.

Discussion

This study shows that compared with traditional methods of medical education, text messages are more effective in leading to a greater understanding of recommendations, especially for family physicians, a result that was shown by changes in prescribing practices.

Several reasons explain the success of text messages in transmitting medical information. First, for the majority of health workers, text messages were the only way they obtained the latest and best clinical knowledge. In our pilot studies, we found that continuing medical education in Gansu Province consisted primarily of training sessions hosted by higher-level health departments.6 However, due to constraints in time and resources, such training sessions happen infrequently, and only reach a small number of health workers throughout the province. Thus, 80% of family physicians relied on medical textbooks to guide the diagnosis and treatment of patients, most of which contained outdated and incorrect recommendations.5

Second, compared to textbooks and printed learning materials, text messages were easier to carry, retrieve and remember. Moreover, our pilot study showed that, of alternative means of communicating medical information, such as television, radio, newspapers, or blackboards in health centres, health workers ranked text messages as their preferred method.30

Third, text messages were tailored to the local disease context and edited on the basis of feedback to suit health workers’ clinical needs. The slight difference in the results at the individual and cluster level could be due to minimal texting between health workers in the same health centre.

Text messages delivered during the intervention were perhaps the first time that some health workers became aware of evidence-based recommendations, given limited opportunities for continued medical education. Yet research has shown that medical education and physicians’ knowledge of the latest recommendations can have a direct influence on the prescription of antibiotics.31 In our study, text messages may have prevented family physicians from prescribing antibiotics and steroids for viral infections affecting the upper respiratory tract. This is of critical importance, since the use of antibiotics has increased at an average annual rate of around 15% in China from 2000 to 2011, 32,33 a finding supported by the prescribing practices of the control group in this study.

Health workers reported that the biggest advantage of using text messages was the ease in receiving and retrieving information. Preliminary research found that health workers had limited time to study medical information, with 62% of health workers having less than 3 hours per week to read medical literature.6 Health workers also reported a preference for information delivery platforms that were more convenient and easier to use. Text messages are limited to only 280 characters, however, which prevent the dissemination of highly detailed recommendations. This weakness could be overcome by increasing the frequency that text messages are sent. An open-access database for health workers that included detailed information on the treatment of each disease could further resolve this issue. Text messages received high scores for their validity and applicability, which suggested that recommendations should be both evidence-based and suited to the local disease context. Nearly all participants in the intervention group (95%) wanted to continue receiving text messages.

A major benefit of using text messages is the cost-effectiveness, which is a key consideration in resource-poor settings. Each text message costs approximately 0.1 Yuan (United States dollars, US$ 0.016) to send. In this study, total expenditure on text messages for the intervention group was less than 1000 Yuan (US$ 160.64), or less than 2 Yuan (US$ 0.32) per health worker. In comparison, the one-day training for the control group cost an average of 560 Yuan (US$ 89.96) per health worker, for printed materials, accommodation and transportation costs. This amounts to a 280-fold difference per person. While not discounting the advantages of traditional medical education, such as the face-to-face interactions, discussions, and communication between trainees and trainers, the use of text messages provides an effective low-cost alternative that can reach a larger audience of health workers more frequently.

In our study, we assessed the effectiveness of text messages as tools to both increase knowledge of evidence-based recommendations, and positively affect physician practices. The main strengths of this study include the pragmatic design, the large numbers of participants, and the subjective and objective outcomes tested. All recommendations sent to health workers came from evidence-based resources, such as the Clinical Evidence and the Cochrane Library. Recommendations were further reviewed and modified by senior physicians from the First Hospital of Lanzhou University to ensure readability and utility. The cluster-randomized trial was preceded by pilot studies conducted at seven health centres over the course of two years. These pilot studies assessed the viability and applicability of text messages for continued medical education, and found that using text messages as a knowledge translation tool could change physician knowledge and behaviour.

However, our results should be considered within the limitations of the study. First, although we evaluated the long-term effects (i.e. one year) of the intervention in our pilot study, only the short-term effects (i.e. three months) were evaluated by telephone survey in the main trial. Future studies should address the long-term utility of text messages as a tool of knowledge translation. Second, the causal relationship between text messages and physicians’ behaviour change remains ambiguous, and could not be fully addressed in this study. Third, although health workers’ scores were higher, on average, after the intervention, their scores remained poor. This suggests that text messaging may be an improvement over the traditional educational method but that its role in continuing medical education needs to be researched further. Fourth, the complexities of behaviour change might not have been fully captured by this study. We assumed that prescriptions were reflective of behaviour, and that physicians were important loci of change, given their authoritative role in health centres. Future studies could build on our findings by developing them through behaviour change theories.34

On the basis of our pilot studies and this cluster-randomized trial, our findings showed that text messages offer a convenient, inexpensive, and effective method to disseminate evidence-based recommendations with the effect of increasing rural health workers’ clinical knowledge and positively impacting their prescription practices.

Acknowledgements

We thank Xiaojuan Xiao, Zehao Wang and Qi Wang for their great help in data collection and telephone surveys. We thank Hairong Bao and Xiaoju Liu for their work in reviewing and revising the text messages. We are also thankful to Emilio Dirlikov and Yngve Falck-Ytter for their comments and revisions on earlier drafts of our trial.

Funding:

This study was funded by grants from the China Medical Board, Grant No. 09-944. The funder had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Competing interests:

None declared.

References

- 1.Wang GR, Tong XH, Ouyang SG, Jiang M, Gong YL, Mei RL. Analysis on requirements of education and training of medical worker in township hospitals in rural areas. Chin J Primary Health Care. 2003;17:17-9 [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ji LQ, Xi B, Zhang DR, Cai JN, Guo JH, Jiang ZW, et al. An investigation of health stuff setup in 189 THCs and status quo of on the job training. Chin J Rural Health Service Administration. 2003;23:21-4 [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wang X, Liang, FX, Feng LL, Zhang Y, Yuan R, Guo Y, et al. [A survey on the education background of health workers in township health centres in Gaolan]. Gansu Sci Technol. 2011;27:149-51 Chinese. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Li SY, Le H, Yu XM. Analysis on the actuality of training and the need of health professionals in township health centers in the poor areas of a province. Med Soc. 2007;20:24-6 [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wang ZH, Feng LL, Zhao YY, Xiao XJ, Yao L, Wang Q, et al. Clinical decision-making by doctors in township hospitals in Gaolan: a questionnaire survey. Chin J Evid-based Med. 2012;12:740-2 [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wei ZP, Guo YM, Chen YL, Lu FS, Si FQ, Tian JH, et al. A Survey on the continuing medical education for village doctors in Gaolan county. Chin J Gansu Med. 2009;28:429-30 [Google Scholar]

- 7.Krishna S, Boren SA, Balas EA. Healthcare via cell phones: a systematic review. Telemed J E Health. 2009;15(3):231-40 10.1089/tmj.2008.0099 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lim MS, Hocking JS, Hellard ME, Aitken CK. SMS STI: a review of the uses of mobile phone text messaging in sexual health. Int J STD AIDS. 2008;19(5):287-90 10.1258/ijsa.2007.007264 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chen YF, Madan J, Welton N, Yahaya I, Aveyard P, Bauld L, et al. Effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of computer and other electronic aids for smoking cessation: a systematic review and network meta-analysis. Health Technol Assess. 2012;16(38):1-205, iii-v [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Holtz B, Lauckner C. Diabetes management via mobile phones: a systematic review. Telemed J E Health. 2012;18(3):175-84 10.1089/tmj.2011.0119 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Militello LK, Kelly SA, Melnyk BM. Systematic review of text-messaging interventions to promote healthy behaviors in pediatric and adolescent populations: implications for clinical practice and research. Worldviews Evid Based Nurs. 2012;9(2):66-77 10.1111/j.1741-6787.2011.00239.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Krishna S, Boren SA. Diabetes self-management care via cell phone: a systematic review. J Diabetes Sci Technol. 2008;2(3):509-17 10.1177/193229680800200324 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Stephens J, Allen J. Mobile phone interventions to increase physical activity and reduce weight: a systematic review. J Cardiovasc Nurs. 2013;28(4):320-9 10.1097/JCN.0b013e318250a3e7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Horvath T, Azman H, Kennedy GE, Rutherford GW. Mobile phone text messaging for promoting adherence to antiretroviral therapy in patients with HIV infection. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;3:CD009756. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Car J, Gurol-Urganci I, de Jongh T, Vodopivec-Jamsek V, Atun R. Mobile phone messaging reminders for attendance at healthcare appointments. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;7:CD007458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.China Statistical Database [Internet]. Total number of text messages in September, 2012. Beijing: National Bureau of Statistics of China; 2013. Available from: http://data.stats.gov.cn/ [cited 2012 Nov 1]. Chinese.

- 17.Yeager VA, Menachemi N. Text messaging in health care: a systematic review of impact studies. Adv Health Care Manag. 2011;11:235-61 10.1108/S1474-8231(2011)0000011013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wei J, Hollin I, Kachnowski S. A review of the use of mobile phone text messaging in clinical and healthy behaviour interventions. J Telemed Telecare. 2011;17(1):41-8 10.1258/jtt.2010.100322 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cole-Lewis H, Kershaw T. Text messaging as a tool for behavior change in disease prevention and management. Epidemiol Rev. 2010;32(1):56-69 10.1093/epirev/mxq004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Webb TL, Joseph J, Yardley L, Michie S. Using the internet to promote health behavior change: a systematic review and meta-analysis of the impact of theoretical basis, use of behavior change techniques, and mode of delivery on efficacy. J Med Internet Res. 2010;12(1):e4 10.2196/jmir.1376 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lau PW, Lau EY, Wong P, Ransdell L. A systematic review of information and communication technology-based interventions for promoting physical activity behavior change in children and adolescents. J Med Internet Res. 2011;13(3):e48 10.2196/jmir.1533 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Déglise C, Suggs LS, Odermatt P. SMS for disease control in developing countries: a systematic review of mobile health applications. J Telemed Telecare. 2012;18(5):273-81 10.1258/jtt.2012.110810 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Donner A, Klar N. Design and analysis of cluster randomisation trials in health research. New York (NY): Oxford University Press; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Clinical evidence [Internet]. Learn, teach, and practise evidence-based medicine. London: BMJ Publishing Group; 2014. Available from: http://clinicalevidence.bmj.com/x/index.html [cited 2009 Jun 31].

- 25.Arroll B, Kenealy T. Antibiotics for the common cold and acute purulent rhinitis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2005;3(3):CD000247 10.1002/14651858.CD000247.pub3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jefferson T, Jones MA, Doshi P, Del Mar CB, Heneghan CJ, Hama R, et al. Neuraminidase inhibitors for preventing and treating influenza in healthy adults and children. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;1:CD008965.http://dx.doi:10.1002/14651858 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Feng X, Ren R. Analysis on revenue and expenditure of medicine and prescription drug of township hospitals in rural areas of west of China. Chin J Primary Health Care. 2003;17:14-6 [Google Scholar]

- 28.Shu F. Analysis on the use of antibiotics with children suffering acute upper respiratory tract in township hospitals in rural areas. Chin J Med Information. 2009;22:1624-5 [Google Scholar]

- 29.Taljaard M, Donner A, Klar N. Imputation strategies for missing continuous outcomes in cluster randomized trials. Biom J. 2008;50(3):329-45 10.1002/bimj.200710423 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Xiao XJ, Wang ZH, Zhao YY, Yao L, Yang KH, Guo YM, et al. A survey on the continuing medical education based on short message service for village doctors in Gaolan county. Chin J Evid-based Med. 2011;11:261-4 [Google Scholar]

- 31.Davis DA, Thomson MA, Oxman AD, Haynes RB. Changing physician performance. A systematic review of the effect of continuing medical education strategies. JAMA. 1995;274(9):700-5 10.1001/jama.1995.03530090032018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ding C. Retrospective analysis of antibiotics application in department of urinary surgery on recent 10 Years. Chinese J Clin Rational Drug Use. 2012;5:30-1 [Google Scholar]

- 33.Liang YL, Huang XC. Use of carbopenem antibacterials in our hospital during 2000-2006. China Pharmacy. 2007;18:2744-5 [Google Scholar]

- 34.Teixeira Rodrigues A, Roque F, Falcão A, Figueiras A, Herdeiro MT. Understanding physician antibiotic prescribing behaviour: a systematic review of qualitative studies. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2013;41(3):203-12 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2012.09.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]