Abstract

Objective

To synthesize the data available – on costs, efficiency and economies of scale and scope – for the six basic programmes of the UNAIDS Strategic Investment Framework, to inform those planning the scale-up of human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) services in low- and middle-income countries.

Methods

The relevant peer-reviewed and “grey” literature from low- and middle-income countries was systematically reviewed. Search and analysis followed Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analyses guidelines.

Findings

Of the 82 empirical costing and efficiency studies identified, nine provided data on economies of scale. Scale explained much of the variation in the costs of several HIV services, particularly those of targeted HIV prevention for key populations and HIV testing and treatment. There is some evidence of economies of scope from integrating HIV counselling and testing services with several other services. Cost efficiency may also be improved by reducing input prices, task shifting and improving client adherence.

Conclusion

HIV programmes need to optimize the scale of service provision to achieve efficiency. Interventions that may enhance the potential for economies of scale include intensifying demand-creation activities, reducing the costs for service users, expanding existing programmes rather than creating new structures, and reducing attrition of existing service users. Models for integrated service delivery – which is, potentially, more efficient than the implementation of stand-alone services – should be investigated further. Further experimental evidence is required to understand how to best achieve efficiency gains in HIV programmes and assess the cost–effectiveness of each service-delivery model.

Résumé

Objectif

Synthétiser les données disponibles - sur les coûts, l'efficacité et les économies d'échelle et d'envergure - pour les six programmes de base du Cadre d'investissement stratégique de l'ONUSIDA, afin d'informer les responsables de la planification de l'élargissement des services de lutte contre le virus de l'immunodéficience humaine (VIH) dans les pays à revenu faible et intermédiaire.

Méthodes

Des pairs des pays à revenu faible et intermédiaire ont systématiquement examiné la documentation pertinente «grise» et révisée. La recherche et l'analyse ont appliqué les directives PRISMA (éléments de rapport préférés pour les examens systématiques et les méta-analyses).

Résultats

Des 82 études de coûts et de rendement empiriques identifiées, neuf fournissaient des données sur les économies d'échelle. L'échelle expliquait en grande partie la variation des coûts de plusieurs services anti-VIH, en particulier ceux de la prévention ciblée du VIH dans les populations clés et ceux du dépistage et du traitement du VIH. Il existe certaines preuves d'économies d'envergure, résultant de l'intégration de services de conseil et de dépistage du VIH avec plusieurs autres services. La rentabilité peut également être améliorée en réduisant les prix des intrants, en déléguant des tâches et en améliorant l'adhésion des clients.

Conclusion

Les programmes anti-VIH doivent optimiser l'échelle de prestation des services pour être efficaces. Les interventions qui peuvent améliorer le potentiel des économies d'échelle comprennent l'intensification des activités de création de la demande, la réduction des coûts pour les utilisateurs des services, l'expansion des programmes existants plutôt que la création de nouvelles structures, et la réduction de l'attrition des utilisateurs des services existants. Les modèles de prestation des services intégrés, qui sont potentiellement plus efficaces que la mise en œuvre de services autonomes, doivent faire l'objet d'études approfondies. D'autres éléments de preuve expérimentaux sont requis pour trouver la meilleure façon d'obtenir des gains en termes d'efficacité dans les programmes anti-VIH, mais aussi pour évaluer le rapport coût-efficacité de chaque modèle de prestation de services.

Resumen

Objetivo

Sintetizar los datos disponibles sobre los costes, la eficacia y las economías de escala y alcance de los seis programas básicos del Marco Estratégico de Inversión de ONUSIDA e informar a los responsables de la planificación de la ampliación de los servicios del virus de la inmunodeficiencia humana (VIH) en países con ingresos bajos y medios.

Métodos

Se examinó sistemáticamente la literatura revisada por homólogos y «gris» relevante de países con ingresos bajos y medios. La búsqueda y el análisis se realizaron según las pautas de Ítems de Informe Preferidos para Evaluaciones Sistemáticas y Meta-Análisis.

Resultados

De los 82 estudios empíricos sobre costes y eficacia identificados, nueve de ellos proporcionaron datos sobre las economías de escala. La escala explicó gran parte de la variación de los costes en numerosos servicios de VIH, en particular en aquellos dirigidos a la prevención del VIH en poblaciones clave y las pruebas y el tratamiento del VIH. Hay alguna evidencia de economías de alcance que integran el asesoramiento sobre el VIH y los servicios de pruebas con muchos otros servicios. También sería posible aumentar la costo-eficacia mediante la reducción de los precios de los insumos, la delegación de funciones y la mejora de la fidelidad de los clientes.

Conclusión

Los programas de VIH deben optimizar la escala de prestación de servicios para conseguir ser eficaces. Las intervenciones pueden mejorar el potencial de las economías de escala, por ejemplo, al intensificar las actividades de promoción de demanda, reducir los costes para los usuarios, expandir los programas existentes en lugar de crear estructuras nuevas y reducir el abandono de los usuarios existentes de los servicios. Se deben investigar más los modelos de prestación de servicios integrados, que son posiblemente más eficaces que la implementación de servicios independientes. Es necesario obtener más evidencia experimental para comprender cómo es posible lograr mayor eficacia en los programas de VIH y evaluar la costo-eficacia de cada modelo de prestación de servicios.

ملخص

الغرض

توليف البيانات المتاحة - بشأن التكاليف والكفاءة ووفورات الحجم والنطاق - المتعلقة بالبرامج الأساسية الستة لإطار الاستثمار الاستراتيجي لبرنامج الأمم المتحدة المشترك لمكافحة الإيدز، بغية توفير المعلومات لمن يقومون بتخطيط زيادة حجم خدمات فيروس العوز المناعي البشري في البلدان المنخفضة الدخل والبلدان المتوسطة الدخل.

الطريقة

تم إجراء استعراض منهجي للمنشورات التي خضعت للاستعراض الجماعي والمؤلفات "غير الرسمية" ذات الصلة من البلدان المنخفضة الدخل والبلدان المتوسطة الدخل. واتبع البحث والتحليل البنود المتعلقة بتقديم التقارير المفضلة للمبادئ التوجيهية للاستعراضات المنهجية والتحليلات الوصفية.

النتائج

قدمت تسع دراسات، من إجمالي 82 دراسة تجريبية للتكلفة والكفاءة تم تحديدها، بيانات عن وفورات الحجم. وفسر النطاق الكثير من التفاوت في تكاليف العديد من خدمات فيروس العوز المناعي البشري، لاسيما تلك المتعلقة بالوقاية المستهدفة من فيروس العوز المناعي البشري في الفئات السكانية الرئيسية واختبارات فيروس العوز المناعي البشري وعلاجه. وهناك بعض البيّنات حول وفورات الحجم المستمدة من دمج استشارات فيروس العوز المناعي البشري وخدمات الاختبارات مع عدة خدمات أخرى. ويمكن كذلك تحسين خفض التكاليف عن طريق تقليل أسعار المدخلات وإعادة توزيع المهام وتحسين التزام العميل.

الاستنتاج

يتعين على برامج فيروس العوز المناعي البشري تحسين نطاق تقديم الخدمات بغية تحقيق الكفاءة. وتشمل التدخلات التي يمكنها تعزيز إمكانيات وفورات الحجم تكثيف أنشطة إيجاد الطلب، وتقليل التكاليف التي يتحملها مستخدمو الخدمات، وتوسيع البرامج القائمة بدلاً من إنشاء هياكل جديدة، وتقليل التناقص في مستخدمي الخدمات القائمة. وينبغي إجراء مزيد من التحري لنماذج الإيتاء المتكامل للخدمات، التي يحتمل أن تكون أكثر كفاءة من تنفيذ خدمات قائمة بذاتها. وثمة حاجة لمزيد من البيّنات التجريبية بغية فهم كيفية تحقيق مكاسب الكفاءة في برامج فيروس العوز المناعي البشري وتقييم مردودية كل نموذج من نماذج إيتاء الخدمة.

摘要

目的

综合联合国艾滋病规划署战略投资框架的六种基本规划可用的成本、效率、经济规模和范围的相关数据,为在中低收入国家开展的扩大艾滋病病毒(HIV)服务计划提供信息。

方法

系统评价了中低收入国家相关同行评议的“灰色”文献。根据系统评价和荟萃分析指南的优先报告条目执行搜索和分析。

结果

在所识别的82项实证成本和效率研究中,有九项研究提供了规模经济相关数据。规模解释了数种HIV服务成本的很多变化,尤其是有针对性的重点人群HIV预防和HIV检测和治疗的成本变化。在HIV咨询和测试服务和其他若干服务整合的服务中有一些范围经济的证据。也可以通过降低输入价格、任务切换和提高客户忠诚度来改进成本效益。

结论

HIV计划需要最优化服务提供的规模以实现效益。可提高规模经济潜力的干预措施包括强化需求创建活动、降低服务用户的成本、扩大现有的项目(而不是创建新的结构)以及减少现有服务用户的脱失。整合服务交付模型可能比实施独立服务更有效,需要对其进行进一步的调查。需要进一步的实验证据来理解如何在HIV计划中最好地实现增效以及评估每个服务交付模型的成本效益。

Резюме

Цель

Сопоставить доступные данные по расходам, эффективности и экономии на масштабах и объемах по шести основным программам Рамочной программы стратегических инвестиций ЮНЭЙДС и предоставить информацию тем, кто планирует расширение масштабов оказания услуг, связанных с вирусом иммунодефицита человека (ВИЧ), в странах с низким и средним уровнями доходов.

Методы

Был проведен систематический обзор соответствующей рецензируемой и внеиздательской («серой») литературы из стран с низким и средним уровнями доходов. В процессе поиска и анализа соблюдались положения Руководства по предпочтительным позициям отчетности для систематических обзоров и мета-анализов.

Результаты

Из 82 выявленных эмпирических исследований расчета затрат и эффективности в девяти содержались данные об экономии на масштабах. Масштабом объяснялась большая часть различий в стоимости нескольких ВИЧ-услуг, в особенности тех услуг, которые охватывали профилактику ВИЧ среди целевых групп населения, тестирование на ВИЧ и лечение ВИЧ. Имеется ряд доказательств экономии на масштабах при объединении услуг консультирования по ВИЧ и тестирования на ВИЧ с некоторыми другими услугами. Экономическую эффективность также можно повысить за счет снижения цен на ресурсы, перераспределения задач и повышения уровня лояльности клиентов.

Вывод

В рамках программ по ВИЧ необходимо оптимизировать масштабы предоставления услуг для повышения их эффективности. К числу мер, которые могут повысить потенциал экономии на масштабах, относится более активное проведение мероприятий по стимулированию спроса, снижение затрат пользователей услуг, расширение существующих программ вместо создания новых структур, а также сокращение потерь пользователей существующих услуг. Требуется дальнейшее изучение моделей комплексного оказания услуг, что потенциально является более эффективным, чем оказание отдельных услуг. Требуются дополнительные экспериментальные доказательства для определения наилучших путей достижения эффективности программ по ВИЧ и оценки экономической эффективности каждой модели предоставления услуг.

Introduction

To reach the Millennium Development Goals for human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection1 and the targets of the Political Declaration on HIV and Acquired Immunodeficiency Syndrome (AIDS),2 many low- and middle-income countries still need to scale up essential HIV services. Given the scarce financial resources available and competing donor priorities, methods to improve efficiency in the delivery of HIV services are gaining increased global attention.3–6

In general, an “efficient” HIV service cannot be improved without the further use of existing resources and cannot be maintained at its current level with fewer resources. The word “efficiency” has several dimensions when applied to HIV services. For example, economic theory distinguishes between efficiency from improving social welfare – the “allocative” efficiency that is often assessed in the health sector in terms of cost–effectiveness – and a more contained definition of efficiency that examines how best to use resources to provide individual services – the “technical” efficiency that is commonly assessed in terms of the unit costs of a service. Two potential areas for improving technical efficiency are service scale and service scope. “Economies of scale” are the reductions in the unit cost of a service that might be achieved when the volume of that service’s provision is increased, whereas “economies of scope” are the reductions in the unit cost of a service that might be observed when that service is provided jointly with other services.3,4,7–12

There have been several recent reviews of the data available on the costs and cost–effectiveness of HIV interventions.3,4,7–13 Most of these reviews were focused on allocative efficiency.3,4,7,9,12 The results of the few previous studies on the technical efficiency of HIV services indicate not only that there is considerable variation – between service providers and between settings – in the unit costs of providing similar HIV services, but also that there is, in general, much scope for improving the technical efficiency of HIV services.7,9,14 However, these reviews are outdated or were only partial in their coverage of possible interventions.

Given the current interest of policy-makers in reducing the costs of HIV services, there is now an urgent need to update and synthesize the data on the technical efficiency of HIV services. We therefore present here a systematic literature review of the costs of the six basic programmatic activities of the Strategic Investment Framework of the Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS): antiretroviral therapy (ART) and counselling and testing; “key-population” programmes – that is, programmes that target groups of individuals who are at particularly high risk of HIV infection; condom distribution and social marketing; voluntary medical male circumcision; programmes to eliminate HIV infections among children and to keep their mothers alive; and programmes of behaviour-change communications targeted at young adults and the general population.15

Methods

Search strategy and selection criteria

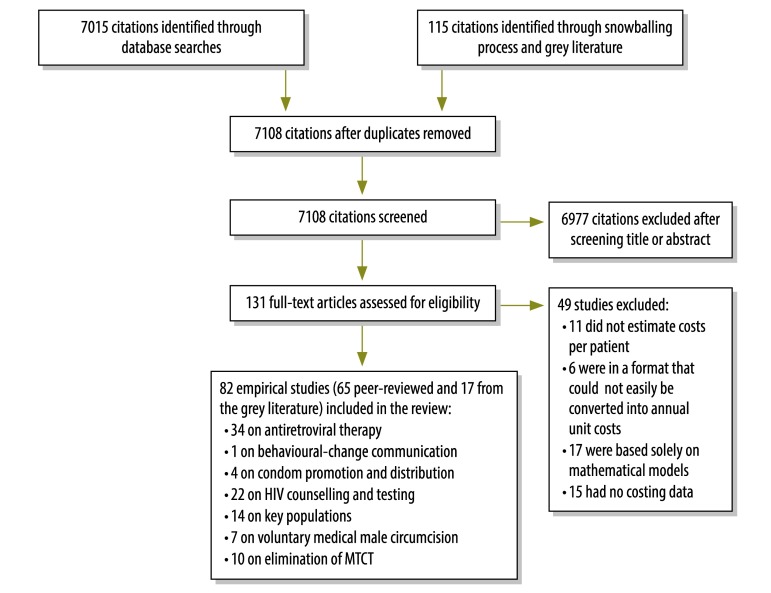

We conducted a systematic review of the peer-reviewed and “grey” literature on HIV services in low- and middle-income countries by following the search and analysis process recommended in the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analyses guidelines.16 The PubMed and Eldis databases and the Cochrane library were searched, using AIDS, HIV, acquired immunodeficiency syndrome, cost, cost analysis, efficiency, economies of scale and economies of scope as the search terms. Searches were limited to English-language articles published between January 1990 and October 2013. Manual searches of the web sites of key organizations were also carried out to identify grey literature and minimize the risk of publication bias (Fig. 1).17 The World Bank’s definitions were used to categorize countries as low- or middle-income.18 Although conference abstracts, editorials, commentaries and “letters to the editor” were used to identify related studies – through a “snowballing” process – any data found only in such publications were excluded from the systematic review. Studies of mathematical models that provided no primary data on costs were also excluded. Bibliographies and previous systematic reviews were examined to identify additional studies of relevance. Authors were contacted directly if the full text of a published paper, unpublished paper or report was not available to us. Two researchers screened the identified citations, reviewed the full texts of potentially eligible articles and selected the final articles for inclusion. Data were extracted by one researcher before being checked by another researcher. Whenever there was uncertainty or disagreement about the inclusion of a study, the authors discussed the study until a consensus was reached.

Fig. 1.

Flowchart for the selection of studies on costs of the six basic programmes of UNAIDS Strategic Investment Framework

MTCT: elimination of mother-to-child transmission; HIV: human immunodeficiency virus.

Note: Some studies included costing data on more than one type of intervention.

Data on the unit costs of the HIV services of interest were available for seven upper-middle-income countries, 14 lower-middle-income countries and 12 low-income countries. Most of the included studies were categorized as cost analyses but cost data were also extracted from cost–effectiveness and cost–benefit analyses, resource-needs estimations and broad evaluation studies. Authors of only 30 of the included studies undertook sensitivity analyses to assess the levels of uncertainty in their cost estimates.

Data extraction and quality of studies

The quality of studies was assessed using Drummond’s checklist.19 Additional criteria for the assessment of study quality were included whether all relevant costs were included, the source of the cost estimates, whether a sensitivity analysis was conducted and, if so, what type of sensitivity analysis was used, and the scale of the study – in terms of the number of sites for which costings were made. As we wished to evaluate the overall quality of studies, we included all studies with some empirical basis, irrespective of their quality. However, we took study quality into account when reporting the strength of the evidence.

We used the unit costs of service provision – at the health-provider level – as our primary comparative statistic. However, we also noted whether the data from each study included other, “above-service” costs, such as the out-of-pocket expenses of clients using a particular HIV service. We took a narrative approach in our data synthesis, as has been recommended for reviews of health systems and organizational interventions.17

For the purposes of the systematic review, all reported costs were adjusted to United States dollar (US$) values for the year 2011.

Results

Summary of studies

We identified 7108 unique citations of potential relevance and selected 131 of these for full-text review (Fig. 1). Overall, 82 studies met the inclusion criteria: 65 reported in peer-reviewed journals and 17 reported in the grey literature (Table 1). Most (n = 63) of the included studies were classified as fully empirical and 34 included all relevant costs. Costing methods varied between studies but included a “top-down” approach, a “bottom-up” approach and a combination of both of these approaches. Together, the 82 included studies covered 92 unit-cost analyses that related to ART (n = 34), key population programmes (n = 14), HIV counselling and testing (n = 22), programmes to eliminate HIV infections among children and to keep their mothers alive (n = 10), male circumcision (n = 7), condom distribution (n = 4) or behaviour-change communications (n = 1). Many studies were excluded because they did not relate to core HIV or AIDS services, were not conducted in a low- or middle-income country or did not report empirical costs.

Table 1. Quality of studies included in the systematic review.

| Quality criterion | No. of studies |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Antiretroviral therapy | Behaviour-change communication | Condom promotion and distribution | Elimination of MTCT | HIV counselling and testing | Key populations | Voluntary medical male circumcision | |

| Publication type | |||||||

| Peer-reviewed article | 28 | 1 | 4 | 8 | 16 | 14 | 1 |

| Grey literature | 6 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 6 | 0 | 6 |

| Focus of study | |||||||

| Cost–effectiveness analysis | 7 | 1 | 2 | 4 | 5 | 5 | 6 |

| Cost–benefit analysis | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Cost analysis | 20 | 0 | 1 | 5 | 15 | 8 | 0 |

| Cost analysis and resource-needs estimation | 5 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Programme evaluation | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Resource-needs estimation | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 1 | 0 |

| Costing scale | |||||||

| National models | 0 | 0 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 4 | 0 |

| Single site | 15 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 5 | 0 | 0 |

| Small sample (≤ 30 sites) | 15 | 1 | 2 | 9 | 16 | 9 | 7 |

| Large sample (> 30 sites) | 4 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Empirical or modelled costs | |||||||

| Empirical | 24 | 1 | 4 | 5 | 17 | 10 | 3 |

| Modelled from empirical study data | 10 | 0 | 0 | 5 | 5 | 4 | 4 |

| Costs included | |||||||

| Single cost category (e.g. drugs) | 3 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 7 |

| Salaries and recurrent costs | 13 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 8 | 3 | 0 |

| Salary, non-salary and capital costs | 12 | 1 | 3 | 5 | 8 | 8 | 0 |

| Upstream support and systems costs | 5 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 3 | 0 | 4 |

| Uncertainty analysis | |||||||

| None | 28 | 0 | 2 | 6 | 15 | 6 | 5 |

| Univariate sensitivity analysis | 3 | 0 | 0 | 4 | 4 | 6 | 1 |

| Univariate and multivariate sensitivity analyses | 3 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 0 |

| Results of sensitivity analysis not shown | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 |

MTCT: mother-to-child transmission; HIV: human immunodeficiency virus.

Table 2, Table 3, Table 4, Table 5, Table 6, Table 7 and Table 8 provide summaries of costs reported in the literature that we reviewed. Further details can be found in Table 9, Table 10, Table 11, Table 12, Table 13, Table 14 and Table 15 (available at: http://www.who.int/bulletin/volumes/92/7/13-127639) and in Appendix A (available at: http://researchonline.lshtm.ac.uk/1620414/). The costs reported in the included studies were generally restricted to the unit costs of one or more HIV services at site level. The reporting of “above-service” costs varied and was always only partial. Most studies included the costs of activities such as training and supervision,36,37 but the costs of several other activities, such as the maintenance of a drugs supply chain, transportation and technical support, were rarely included.

Table 2. Summary of selected mean unit costs of antiretroviral therapy.

| Region and referencea | Country | Cost per patient-year, US$b |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pre-ART | ART |

|||||

| Drugs excluded | Regimen unclear | First-line | Second-line | |||

| Africa – eastern and southern | ||||||

| Menzies et al. (2011)20 | Botswana | 200.16 | 343.87c | |||

| Bikilla et al. (2009)21 | Ethiopia | 137.09 | 82.70 | 305.50d | ||

| Kombe et al. (2005)22 | Ethiopia | 268.01 | 812.15 | |||

| Marseille et al. (2011)23 | Ethiopia | 147.81 | ||||

| Menzies et al. (2011)20 | Ethiopia | 153.97 | 170.40c | 660.03c | ||

| Cleary et al. (2007)24 | Lesotho | 18.00 | 33.57e or 41.28f | 900.50c | 1285.90c | |

| Cleary et al. (2006)25 | South Africa | 566.46 | 944.51c,g | 914.99c | 1746.31c | |

| Deghaye et al. (2006)26 | South Africa | 745.66 | 1325.81 | |||

| Harling et al. (2007)27 | South Africa | 545.60 | ||||

| Harling and Wood (2007)28 | South Africa | 444.97 | 1323.59h,i,j | 2010.82h,i,j | ||

| Rosen et al. (2008)29 | South Africa | 545.42 | 1033.98 | |||

| Vella et al. (2008)30 | South Africa | 107.34h | 207.30h | |||

| Kevany et al. (2009)31 | South Africa | 1815.98d | ||||

| Martinson et al. (2009)32 | South Africa | 1206.91 | 773.26k | 1849.45k | ||

| Long et al. (2010)33 | South Africa | 311.50 | 1087.65 | |||

| Long et al. (2011)34 | South Africa | 565.59 | ||||

| Babigumira et al. (2009)35 | Uganda | 525.37l | ||||

| Jaffar et al. (2009)36 | Uganda | 415.80m | 855.33m | |||

| Menzies et al. (2011)20 | Uganda | 145.76 | 186.82 | 972.08c | ||

| Bratt et al. (2011)37 | Zambia | 359.62n | ||||

| Africa – western and central | ||||||

| Hounton et al. (2008)38 | Benin | 398.26 | 1347.88o | |||

| Renaud et al. (2009)39 | Burundi | 701.78 | 1017.07j | |||

| Kombe et al. (2004)40 | Nigeria | 443.02 | 879.00 | |||

| Partners for Health Reformplus (2004)41 | Nigeria | 761.13 | 1881.20 | |||

| Menzies et al. (2011)20 | Nigeria | 265.86 | 347.98c | 883.80c | ||

| Aliyu et al. (2012)42 | Nigeria | 210.70p | ||||

| Asia and Pacific | ||||||

| Gupta et al. (2009)43 | India | 191.63 | 380.00 | |||

| John et al. (2006)44 | India | 130.87 | 451.44 | |||

| Kitajima et al. (2003)45 | Thailand | 42.99i | 407.26d | |||

| Menzies et al. (2011)20 | Viet Nam | 176.56 | 144.73 | 948.47c | ||

| Caribbean | ||||||

| Koenig et al. (2008)46 | Haiti | 580.45 | 1151.46j | |||

| Latin America | ||||||

| Marques et al. (2007)47 | Brazil | 2757.65 | 5875.46 | |||

| Aracena-Genao et al. (2008)48 | Mexico | 8536.18 | 8065.84 | 7145.01 | ||

| Bautista et al. (2003)49 | Mexico | 835.00 | 1047.87 | 4278.00q | ||

| Contreras-Hernandez et al. (2010)50 | Mexico | 2006.58d | ||||

| Northern Africa and Middle East | ||||||

| Loubiere et al. (2008)51 | Morocco | 415.72r | 1155.85r | |||

ART: antiretroviral therapy; US$: United States dollars.

a The regions shown are those defined and commonly used by the Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS.

b Adjusted to the dollar values for the year 2011.

c Mean annualized costs for established adult ART patients.

d Mean inpatient and outpatient costs.

e First-line regimen.

f Second-line regimen.

g Mean value excluding costs of first- and second-line drugs and other health services – such as hospitalization.

h Per patient-year of observation.

i Mean annual cost of first 2 years of post-ART care.

j Based on both first- and second-line regimens.

k Excluding first month of initiation.

l Cost of ART was assumed to be the mean cost of first-line drugs, which was estimated – in the values for 2007 – at US$ 237.50 per patient-year.

m Mean costs of home- and facility-based care.

n Mean for first year ART across all drug regimens and facility types.

o Based on a mean number of 1000 people treated per year and annual provision of services to 14 000.

p Based on the assumption that 78% of patients were on the first-line regimen.

q Mean annual cost of first 3 years of post-ART care.

r Mean value across different CD4+ T-lymphocyte count groups.

Table 3. Summary of selected mean unit costs of behaviour-change communications.

| Region and referencea | Country | Cost per person reached, US$b |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Billboards | Peer education | Magazines | Radio broadcasts | Public outreach events | ||

| Africa – western and central | ||||||

| Hsu et al. (2013)52 | Benin | 25.73 | 39.98 | 18.62 | 4.62 | 2.35 |

US$, United States dollars.

a The region shown is one defined by the UNAIDS (Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS).

b Adjusted to the dollar values for the year 2011. For magazines, radio broadcasts and public outreach events, the corresponding costs per person reporting systematic condom use were US$ 22.83, US$ 25.73 and US$ 31.94, respectively.

Table 4. Summary of selected mean unit costs of condom promotion and distribution.

| Region and referencea | Country | Cost, US$b |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Per person reached | Per condom sold | Per condom distributed | ||

| Africa – eastern and southern | ||||

| Söderlund et al. (1993)53 | Uganda | 0.34 | ||

| Terris-Prestholt et al. (2006)54 | Uganda | 0.12 | ||

| Terris-Prestholt et al. (2006)55 | United Republic of Tanzania | 1.54 | ||

| Söderlund et al. (1993)53 | Zimbabwe | 0.97 | 0.16 | |

| Africa – western and central | ||||

| Söderlund et al. (1993)53 | Cameroon | 0.54 | ||

| Söderlund et al. (1993)53 | Democratic Republic of the Congo | 0.18 | ||

| Söderlund et al. (1993)53 | Ghana | 0.13 | ||

| Asia and Pacific | ||||

| Dandona et al. (2010)56 | India | 1.54 | ||

| Söderlund et al. (1993)53 | Indonesia | 0.07 | ||

| Caribbean | ||||

| Söderlund et al. (1993)53 | Dominican Republic | 0.21 | ||

| Latin America | ||||

| Söderlund et al. (1993)53 | Bolivia | 0.72 | ||

| Söderlund et al. (1993)53 | Brazil | 1.12 | ||

| Söderlund et al. (1993)53 | Côte d’Ivoire | 0.24 | ||

| Söderlund et al. (1993)53 | Ecuador | 0.29 | ||

| Söderlund et al. (1993)53 | Mexico | 0.41 | ||

| Northern Africa and Middle East | ||||

| Söderlund et al. (1993)53 | Morocco | 0.81 | ||

US$: United States dollars.

a The regions shown are those defined and commonly used by the Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS.

b Adjusted to the dollar values for the year 2011.

Table 5. Summary of selected mean unit costs of human immunodeficiency virus counselling and testing.

| Region and referencea | Country | Cost, US$b |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Per client | Per person tested | ||

| Africa – eastern and southern | |||

| Kombe et al. (2005)22 | Ethiopia | 4.97 | |

| Twahir et al. (1996)57 | Kenya | 15.02 | |

| Sweat et al. (2000)58 | Kenya | 35.20 | |

| Forsythe et al. (2002)59 | Kenya | 61.72 | |

| John et al. (2008)60 | Kenya | 7.25c | |

| Liambila et al. (2008)61 | Kenya | 21.60 | |

| Negin et al. (2009)62 | Kenya | 6.77 | |

| Grabbe et al. (2010)63 | Kenya | 22.10 | |

| Obure et al. (2012)64 | Kenya | 7.96 | |

| McConnel et al. (2005)65 | South Africa | 72.35 | |

| Hausler et al. (2006)66 | South Africa | 2.64d | 3.42 |

| Obure et al. (2012)64 | Swaziland | 11.52 | |

| Terris-Prestholt et al. (2006)54 | Uganda | 32.62e | |

| Menzies et al. (2009)67 | Uganda | 14.33 | |

| Tumwesigye et al. (2010)68 | Uganda | 7.52 | |

| Sweat et al. (2000)58 | United Republic of Tanzania | 38.21 | |

| Bratt et al. (2011)37 | Zambia | 18.82 | |

| Africa – western and central | |||

| Kombe et al. (2004)40 | Nigeria | 8.89 | |

| Aliyu et al. (2012)42 | Nigeria | 7.52 | |

| Asia and Pacific | |||

| Dandona et al. (2005)69 | India | 9.76e | |

| Das et al. (2007)70 | India | 2.61 | |

US$: United States dollars.

a The regions shown are those defined and commonly used by the Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS.

b Adjusted to the dollar values for the year 2011.

c Mean cost of individual and “couple” counselling of all women.

d Per client pre- and post-test counselled.

e Per client post-test counselled.

Table 6. Summary of selected mean unit costs of key-population programmes.

| Region and referencea | Country | Cost per person reached, US$b |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Commercial sex workers | Men who have sex with men | Truck drivers | Injecting drug users | Peer health workers | Prisoners | ||

| Africa – eastern and southern | |||||||

| Moses et al. (1991)71 | Kenya | 123.36 | |||||

| Chang et al. (2013)72 | Uganda | 16.21c | |||||

| Asia and Pacific | |||||||

| Guinness et al. (2010)73 | Bangladesh | 9.93 | |||||

| Dandona et al. (2005)74 | India | 16.52 | |||||

| Guinness et al. (2005)75 | India | 23.25 | |||||

| Fung et al. (2007)76 | India | 101.88 | |||||

| Dandona et al. (2008)77 | India | 24.02 | |||||

| Kumar et al. (2009)78 | India | 2.78 | 2.78 | ||||

| Chandrashekar et al. (2010)79 | India | 185.06d | |||||

| Dandona et al. (2010)56 | India | 35.81 | 8.64 | 2.78 | |||

| Siregar et al. (2011)80 | Indonesia | 40.90 | 68.17 | 24.12 | |||

| Eastern Europe and central Asia | |||||||

| Kumaranayake et al. (2004)81 | Belarus | 70.29 | |||||

| Vickerman et al. (2006)82 | Ukraine | 5.36 | |||||

US$, United States dollars.

a The regions shown are those defined and commonly used by the Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS.

b Adjusted to the dollar values for the year 2011.

C US$ 9.16 per person reached, if the costs of supervision are excluded.

d US$ 149.38 per person receiving sexually-transmitted-infection services.

Table 7. Summary of selected mean unit costs of voluntary medical male circumcision.

| Region and referencea | Country | Cost per circumcision performed, US$b |

|---|---|---|

| Africa – eastern and southern | ||

| Futures Institute83 and Kioko, personal communication (2010) | Kenya | 36.26c |

| Binagwaho et al. (2010)84 | Rwanda | 15.67d or 61.65e |

| Martin et al. (2007)85 | Lesotho | 60.84 |

| USAID (2010)86 | South Africa | 70.48 |

| USAID (2010)87 | Uganda | 20.71 |

| Futures Institute83 and Chiwevu, personal communication (2010) | Zambia | 74.10 |

| USAID (2010)88 | Zimbabwe | 66.18 |

US$, United States dollars, USAID, United States Agency for International Development.

a The region shown is one defined and commonly used by the Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS.

b Adjusted to the dollar values for the year 2011.

c Mean value for the static and outreach sites.

d For a hypothetical cohort of 150 000 neonates.

e For a hypothetical cohort of 150 000 adolescents and adults.

Table 8. Summary of selected mean unit costs of the elimination of mother-to-child transmission of human immunodeficiency virus.

| Region and referencea | Country | Cost, US$b |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Per visit | Per patient-year | Per pregnant women | Per mother–neonate pair | Per person counselledc | Per person tested | ||

| Africa – eastern and southern | |||||||

| Orlando et al. (2010)89 | Malawi | 395.17 | |||||

| Desmond et al. (2004)90 | South Africa | 567.36d | 96.22 | 103.82 | |||

| Bratt et al. (2011)37 | Zambia | 42.23d | |||||

| Asia and Pacific | |||||||

| Dandona et al. (2008)91 | India | 257.52 | |||||

US$, United States dollars.

a The regions shown are those defined and commonly used by the Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS.

b Adjusted to the dollar values for the year 2011.

c Both pre- and post-testing.

d Including costs of prenatal and postnatal visits.

Table 9. Studies on antiretroviral therapy included in the systematic review.

| Region and referencea | Last year of data collection | Country | Location | No. and type of sites | Description of intervention or model | Empirical or modelled | Costing scope | Costing method | Mean unit cost(s), US$ (range)b |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Africa – eastern and southern | |||||||||

| Hounton (2008)38 | 2006 | Benin | Urban | 1 public university hospital | Set in the outpatient treatment centre of the National University Hospital. The centre, which was solely devoted to care and support for people living with HIV, received technical support from an NGO. HIV care consisted of physical examination, laboratory checks (CD4 counts, blood cell counts and blood biochemistry) and counselling four times a year and monthly procurement of ART and OI drugs | Empirical (primary cost data from facility) and modelled (over 10 years for 12 outpatient treatment centres and 48 peripheral treatment centres) | Economic, full, societal perspective | Micro-costing, top-down | 1348 (1293–1403) |

| Renaud (2009)39 | 2007 | Burundi | Urban | 1 primary health-care centre run by NGO | The Bujumbura health centre of the Society for Women against AIDS in Africa provided care only to people living with HIV. ART was delivered to 668 people in 2007, making it the fourth largest ART clinic in Burundi. HIV care included outpatient visits, a laboratory and pharmacy, VCT, adherence counselling and psychosocial and food support | Mostly empirical (primary cost and patient-use data; secondary data used for drug prices, CD4 counts, assays of viral load and hospital costs) | Economic, full, provider perspective | Combined top-down and bottom-up micro-costing | 1017 (795–1409) |

| Kombe (2005)22 | 2005 | Ethiopia | National | 6 public hospitals | Set in government-certified hospitals that provided ART, eMTCT and VCT services as stand-alone activities (national guidelines stipulated that these services should be fully integrated in hospital care). Costing of ART services included costs of ARV drugs and clinical monitoring but excluded treatment of OIs | Empirical (primary cost data, with estimates of patient use based on experts’ opinions and protocols) | Financial, incremental, provider perspective | Gross costing, bottom-up | 812 |

| Bikilla (2009)21 | 2006 | Ethiopia | Rural | 1 HIV clinic within a regional public hospital | The HIV unit in the Arba Minch Hospital provided free first-line ART on an outpatient basis, although AIDS patients with severe clinical manifestations could be admitted. CBC counts and clinical chemistry were standard laboratory tests for HIV patients and CD4 counts were introduced in 2005. Final services in relation to HIV care included outpatient consultations, laboratory tests, imaging, drug provision and inpatient services for both non-ART and ART patients | Empirical (data on primary costs and use of inpatient and outpatient services) | Economic, full, provider perspective | Combined bottom-up and top-down micro-costing (with ingredient approach) | 142 (112–178) for non-ART, 308 (301–318) for ART |

| Marseille (2011)23 | 2009 | Ethiopia | Urban | 14 ART-delivery sites in three provinces | The management of ART cases at risk of poor adherence was investigated in 14 sites supported by the I-TECH collaboration between the Universities of Washington and California. The management consisted of adherence counselling and support, health education, peer support and referral of clients to CBOs who were equipped to address specific barriers to adherence (such as malnutrition, substance abuse and material needs for clothing, rent and food) | Empirical | Financial, incremental, provider perspective (included regional and national overhead costs but excluded costs of ARV drugs) | Micro-costing, bottom-up | 148 (41–591) |

| Cleary (2007)24 | 2006 | Lesotho | Rural | 1 public hospital and 14 primary health centres | MSF and the MoH implemented a joint pilot programme with Scott Hospital Health Service Area to decentralize free HIV/AIDS care and treatment, including ART, to the primary health-care level. The programme provided comprehensive HIV services – including eMTCT services and HIV DNA testing by PCR – for early diagnosis of HIV in infants, HIV care (including management of opportunistic infections and other HIV-related conditions), and ART | Empirical (primary cost data on service utilization and programme-level costs, modelling of ARV and laboratory costs based on utilization according to clinical protocols) | Financial, partial, provider perspective | Micro-costing, bottom-up | 18 (11–24) for pre-ART, 1093 (214–1587) for ART |

| Kombe (2004)40 | 2004 | Nigeria | National | 5 public specialized and teaching hospitals providing ART | The provision of ART to HIV patients is a major component of Nigeria’s National HIV/AIDS Emergency Action Plan. The study determined the costs of ART (including ARV drugs and clinical monitoring but excluding treatment of opportunistic infections) in a hospital setting | Empirical (primary and secondary data) | Financial, incremental, provider perspective | Gross costing, bottom-up | 879 |

| Partners for Health Reformplus (2004)41 | 2004 | Nigeria | National | 15 ART clinic and ART centres and 51 private clinics and faith-based and NGO programmes | Assessment of HIV treatment commissioned by USAID and Nigeria Mission. Aims were to understand current status, challenges and costs of providing HIV/AIDS services in public sector (federal government programme) and private sector (corporations, private clinics, faith-based and NGO programmes) | Empirical (secondary data) | Financial, provider perspective | Bottom-up | 1081 in the public sector, 2680 in the private |

| Aliyu (2012)42 | 2010 | Nigeria | Urban and rural | 7 secondary public hospitals and 1 tertiary (4 urban and 4 rural) | HIV services assumed to be integrated. A typical comprehensive site provided a package of HIV testing, prevention, treatment, care and support. The delivery points for ART and HIV testing and counselling were used as cost centres because each was an operational unit that contributed towards the overall cost of HIV/AIDS services in the study hospitals | Empirical | Financial, provider perspective, costing analysis | Micro-costing, top-down | 211 overall; 206 in secondary hospitals, 341 in tertiary, 230 in urban, 203 in rural |

| Cleary (2006)25 | 2002 | South Africa | Periurban | 3 public HIV clinics | HIV clinics, within existing public-sector clinics, provided ART, treatment and prophylaxis of HIV-related and opportunistic infections and events, and counselling and support groups for HIV-positive people. Acute infections were managed at the clinics but severely ill patients were referred to secondary and tertiary hospitals. Suspected TB cases were referred. Both non-ART (actually pre-ART) and ART patients were considered | Empirical (primary cost data for HIV-clinic services and secondary data for part of the cost of TB services and inpatient care at referral hospitals) | Economic, full, provider perspective | Micro-costing, bottom-up | 945 (713–1176) for non-ART, 1483 (831–2696) for ART |

| Deghaye (2006)26 | 2004 | South Africa | Urban and periurban | 2 state-subsidized hospitals | The hospitals provided HAART to their staff members through preferential access or as part of their service package, following national guidelines. HIV testing, counselling and treatment were done on a one-to-one basis with the staff doctor – to preserve staff confidentiality and encourage staff to take up HIV treatment | Empirical (primary cost and patient-use data were collected) | Financial and economic, full and incremental, provider perspective | Micro-costing, bottom-up | 1326 (1045–1607) |

| Harling (2007)28 | 2004 | South Africa | Periurban | 1 ART clinic run by NGO | As above | Empirical | As above | Micro-costing, bottom-up | 2153 (1626–2963) |

| Kevany (2009)31 | 2005 | South Africa | Periurban | 1 public hospital | Set in a secondary hospital with an ARV referral unit designed as a referral service for complex cases from the hospital’s ARV clinic and five local primary ART clinics. The unit provided specialist-directed investigation and treatment, including comprehensive outpatient care and consultation services to patients in the hospital’s medical wards | Empirical (primary cost and resource-use data, with pharmaceutical and procedure costs sourced from government’s drug price list and fee schedule) | Economic, incremental, provider perspective | Combined bottom-up micro-costing (patient-specific costs) and top-down micro-costing (shared costs) | 2782 |

| Martinson (2009)32 | 2005 | South Africa | Urban | One HIV clinic | The perinatal HIV research unit is a research organization located on the campus of the Chris Hani Baragwanath Hospital, but is not administratively integrated within the hospital (no shared costs). It provides a free-of charge ART service. Patients are referred from other programmes in the perinatal HIV research unit or self-refer and are started on ART based on national treatment guidelines. a) Pre-ART visits include baseline CD4, viral load, liver function and haematology tests and symptom-based screening for TB. b) ART: CD4 cell count and viral load are measured every six months, haematology and liver function tests every three months |

Empirical – primary cost and patient service use data |

Economic Full costing Provider perspective |

Combination of top-down and bottom-up |

1207 (893–1521) for pre-ART 2415 (1849–2981) for ART |

| Harling (2007)27 | 2006 | South Africa | Periurban | 1 ART clinic run by NGO | Clinic based at the Gugulethu Day Hospital and jointly run by the Desmond Tutu HIV Centre, the charity Crusaid and the provincial government of the Western Cape. Eligibility criteria for the clinic included a CD4 count of < 200 cells/ml or a history of an AIDS-defining illness. Counsellors were employed from the local community and responsible for up to 50 patients each, providing pre-treatment counselling, group education on living on ART, home visits to monitor adherence and ongoing treatment support | Empirical | Financial, full, provider perspective | Combined top-down micro-costing and bottom-up gross costing | 546 (518–573) |

| Vella (2008)30 | 2006 | South Africa | National | 32 public ART delivery clinics | ART delivery sites had the following profiles: a) Part-time doctor and part-time senior professional nurse with less than 200 new patients per doctor per year; b) Same staff as above but with 200 or more new patients per doctor per year; c) Full-time doctor and senior professional nurse with less than 200 new patients per doctor per year; and d) Same staff as above but with 200 or more new patients per doctor per year |

Empirical cost data from site financial and resource use records and registers |

Financial partial cost (excluding costs of other health services and hospitalisation) Provider perspective |

Top-down micro-costing |

207 |

| Rosen (2008)29 | 2007 | South Africa | 1) Urban 2) Urban 3) Rural 4) Periurban |

1) One public referral hospital 2) One private general practitioners 3) One NGO AIDS clinic 4) One NGO primary care clinic |

Site 1 is a large academic and referral hospital. Its HIV clinic has an associated research unit and donor financial support. Site 2 is a donor-funded, NGO managed programme that contracts private general practitioners to provide ART to indigent patients who would otherwise rely on the public sector. Drug and laboratory regimens, clinic visit schedules and reimbursement conditions are set by the NGO. Site 3 provides ART as well as other facility and community-based HIV⁄AIDS services. It is unusual in being a dedicated, stand-alone HIV/AIDS clinic. Site 4 serves informal settlements on the edge of a large city (Entirely donor funded and has an integrated HIV clinic providing ART and other HIV⁄AIDS services). Each model included a different mix of VCT, palliative care, OI treatment, pre-ART, ART, monitoring visits, laboratory tests and adherence counselling |

Empirical – primary cost and patient service use data |

Economic full costing Provider perspective |

Bottom-up micro-costing | 843 for urban public referral hospital 999 for urban private general practitioners 1039 for rural NGO AIDS clinic 1255 for periurban NGO PC clinic |

| Long (2010)33 | 2007 | South Africa | Urban | 1 public HIV clinic | Set in large outpatient HIV clinic that was in an academic referral hospital and funded by the provincial DoH and USAID. The resource use of adult patients who had begun second-line therapy was considered, including drugs, laboratory tests, outpatient visits to the clinic and a pharmacy, infrastructure and other fixed costs | Empirical (primary cost and resource-use data) | Economic, full, provider perspective | Combined top-down (shared fixed cost) and bottom-up micro-costing (direct costs) | 1088 |

| Long (2011)34 | 2009 | South Africa | Urban | 1 treatment-initiation site and 1 down-referral site | Study designed to evaluate the implications of a down-referral strategy for treatment outcomes and costs | Empirical | Financial, provider perspective, cost–effectiveness analysis | Macro-costing approach (total site-level costs were estimated for each patient type) | 566 at treatment-initiation site, 505 at down-referral site |

| Babigumira (2009)35 | 2008c | Uganda | National (primary data from rural settings) | 2 public clinics (for primary cost data) | National provision of ART and related care through facility-, mobile-clinic- or home-based programmes | Secondary data used for cost of ARVs, empirical primary data for indirect recurrent costs of facility- and mobile-clinic-based care | Financial, full and incremental, provider perspective | Combined bottom-up and top-down | 337, 502 and 738 for facility-, mobile-clinic- and home-based programmes, respectively |

| Jaffar (2009)36 | 2009 | Uganda | Urban, rural and periurban | 1 clinic run by NGO | Large AIDS Support Organisation clinic offered counselling and social and clinical services to people with HIV, based on national guidelines. Eligible patients were prepared for therapy by staff during three clinic visits, which were usually spread over 4 weeks. Information and counselling were provided in groups and in one-to-one sessions. Participants were given drugs for 28 days of treatment and issued with a pill box and a “buffer” supply for 2 days. Patients were encouraged to identify a “medicine companion” to provide adherence support. During a trial, after they had initiated ART, 1453 patients were randomly assigned either to home-based HIV care (with lay workers delivering ART and monitoring patients) or facility-based HIV counselling, ART and monitoring visits | Empirical (primary cost data from organizational accounts) | Economic, full, societal perspective (including supervision costs) | Top-down for provider costs and bottom-up for patient costs | 832 for home-based care, 879 for facility-based |

| Bratt (2011)37 | 2009 | Zambia | Urban and rural | 12 facilities supported by the Zambian Prevention, Care and Treatment Partnership. From these, 6 hospitals and 4 health centres provided human immune-deficiency virus counselling and testing services. Services were integrated |

Initiating, improving and scaling up eMTCT, HCT and clinical-care services, for people living with HIV, during Antenatal Care and Perinatal Care in urban and rural settings | Empirical (resource use estimated from primary data) | Economic, full, provider perspective (including upstream supervision and support costs) |

Combined top-down and bottom-up | 362 for hospital-based sites d 358 for health-centre based sitesd |

| Asia and Pacific | |||||||||

| John (2006)44 | 2005 | India | Urban | 1 NGO site | The Freedom Foundation centre provides care and support for people living with HIV, including HAART and laboratory monitoring. The NGO receives government grants and in-kind support, including essential and TB drugs, NGO staff remuneration, food for inpatients and one-time infrastructure support. Other donors fund the majority of the HIV treatment programme and most clients must pay for their own HAART (medicines and laboratory monitoring). Costs were estimated for patients who were eligible for HAART but could not afford it (who only had their opportunistic infections managed) and patients who were on HAART | Empirical (primary data) | Financial, full, NGO perspective (system costs, ARV costs and other costs borne by government excluded) | Micro-costing, bottom-up (50 patients) | 356 for non-HAART patients, 37 for HAART |

| Gupta (2009)43 | 2006 | India | Urban | 7 multi-specialty public hospitals | In India, the rollout of the National Free ART programme began in 2004 and covered three groups: pregnant women, children aged < 15 years and AIDS patients who sought treatment in large public-sector hospitals. The rollout started in six high-prevalence states and the capital. It was put in place in government hospitals and medical colleges and consisted of a comprehensive range of services (ART, treatment of opportunistic infections, diagnostic tests and outpatient and inpatient services) | Empirical (primary data) | Financial, full, programme perspective (excluded capital costs) | Micro-costing, top-down | 380 (287–545) |

| Kitajima (2003)45 | 2002 | Thailand | Rural | 2 hospitals | The Khon Kaen Regional Hospital was a referral hospital for both the community hospitals in the province and general hospitals in neighbouring provinces. It had a follow-up clinic for HIV-positive patients and provided admission services to them. The North-east Regional Infectious Hospital was a specialized hospital for infectious diseases, focusing on 19 provinces in north-eastern Thailand. It had an HIV clinic and an inpatient ward for HIV-positive patients | Empirical (primary cost and resource- use data plus secondary data for costs of routine outpatient and inpatient service) and modelling (of province-wide and annual unit costs) | Financial (assumed), full, provider perspective | Micro-costing, bottom-up | 4749 |

| Caribbean | |||||||||

| Koenig (2008)46 | 2004 | Haiti | Urban | 1 HIV clinic run by NGO | The Haitian Study Group for Kaposi’s Sarcoma and Opportunistic Infections, which was formed in 1982, provided clinical services and training and conducted research on HIV/AIDS. Specifically, it provided free HIV counselling, testing, STI screening, TB evaluation, ART, laboratory tests, adherence counselling (patients were given pre-paid telephone cards to contact clinic staff), management of opportunistic infections and nutritional supplementation | Empirical (primary data for cohort of 218 patients) | Economic, full, societal perspective | Micro-costing, bottom-up | 1137 |

| Latin America | |||||||||

| Marques (2007)47 | 2001 | Brazil | Urban | 1 public university teaching hospital | Set in a children’s institute that provided clinical services for children exposed to – or infected with HIV – in ambulatory, day-hospital and infirmary units | Empirical (primary data from cohort of 140 HIV-infected patients) | Financial, full, provider perspective | Micro-costing, bottom-up | 5875 (2060–10 732) |

| Bautista (2003)49 and Bautista-Arredondo (2008)92 | 2001 | Mexico | Urban | 11 public facilities, including specialized tertiary care, secondary care and specialized HIV outpatient clinics | Mexico’s five national social-security institutions offered free HIV/AIDS care from specialists in tertiary hospitals and/or secondary hospitals that had specialists. The MoH ran a national programme to cover HIV care and treatment for the uninsured. The costs of HIV/AIDS treatment (including those related to drugs for inpatient and outpatient care, laboratory tests and surgical procedures) for the MoH, the social-security institutions and the National Institute of Health were estimated | Empirical (primary data, for cohort of 1003 HIV-positive patients) | Financial, full, provider perspective | Micro-costing, bottom-up (medication and laboratory costs) | 835 (256–1356) for pre-HAART, 4097 (3729–4820) for HAART |

| Contreras-Hernandez (2010)50 | 2005 | Mexico | Urban | 9 hospitals | Hospital care for HIV/AIDS patients consisted of routine HIV care (for both inpatients and outpatients), ART, tropism testing, treatment of adverse events associated with ART, acute and prophylactic treatment of opportunistic infections, CD4 cell counts, HIV test, and palliative care preceding death for both HIV and opportunistic infections | Empirical (data on hospital unit costs, plus primary resource-use, data based on cohort of 637 patients treated for HIV in one hospital) and modelled (patient-level costs) | Financial, partial (drug costs only), provider perspective | Micro-costing, bottom-up | 2007 (1649–2467) for empirical data, 13 389 (5180–28 494) for modelled |

| Aracena-Genao (2008)48 | 2006 | Mexico | Urban | 1 public hospital | Ambulatory HIV services included outpatient visits, ART drugs, medications used to treat or prevent opportunistic infections and laboratory diagnostic and monitoring tests. Hospitalization activities including inpatient days, drugs, laboratory tests and radiological or surgical procedures. | Empirical (primary cost data) and modelling (for dynamic cohort of 797 HIV patients in care between 1982 and 2006) | Financial, full, provider perspective | Micro-costing, bottom-up | 8536 for non-ART patients, 9407 (7145–13 011) for ART |

| North Africa and Middle East | |||||||||

| Loubiere (2008)51 | 2002 | Morocco | Urban | 1 public hospital | Set in the Infectious Diseases Unit in the Ibn Rochd Hospital – the major facility treating HIV-1 patients in Morocco – which served indigent patients referred from primary health-care facilities | Empirical (primary data from a cohort of 286 HIV-positive patients) | Financial, full, provider perspective, intention-to-treat analysis | Micro-costing, bottom-up | 416 (305–664) for non-HAART, 1156 (1125–1177) for HAART |

| Global | |||||||||

| Menzies (2011)20 | 2007 | Botswana, Ethiopia, Nigeria, Uganda and Viet Nam | National | 7 (Uganda) or 9 outpatient clinics per country | Costs estimated for pre-ART (supportive care, regular clinical and laboratory monitoring) and ART (outpatient first- and second-line regimens), regular clinical and laboratory monitoring, prophylaxis against opportunistic infections, treatment for HIV-related conditions, nutritional support and adherence and other related interventions | Empirical | Financial and economic, full, provider perspective | Micro-costing, top-down | 200 for pre-ART and 514 (344–751) for ART in Botswana, 154 for pre-ART and 842 (660–1048) for ART in Ethiopia, 266 for pre-ART and1263 (884–1818) for ART in Nigeria, 146 for pre-ART and 736 (384–993) for ART in Uganda, 177 for pre-ART and 898 (729–986) for ART in Viet Nam |

| Menzies (2012)93 | 2007 | Botswana, Ethiopia, Nigeria, Uganda and Viet Nam | National | 7 (Uganda) or 9 outpatient clinics per country | Costs estimated for pre-ART (supportive care, regular clinical and laboratory monitoring) and ART (outpatient first- and second-line regimens), regular clinical and laboratory monitoring, prophylaxis against opportunistic infections, treatment for HIV-related conditions, nutritional support and adherence and other related interventions | Empirical, assessed proximal determinant of per-patient costs | Financial and economic, full, provider perspective | Micro-costing, top-down | See Menzies et al. (2011)20 |

AIDS: acquired immunodeficiency syndrome; ART: antiretroviral therapy; ARV: antiretroviral; CBC: complete blood-cell; CBO: community based organization; CD4: cluster of differentiation 4; DNA: deoxyribonucleic acid; DoH: Department of Health; eMTCT: elimination of mother-to-child transmission; HAART; highly-active antiretroviral therapy; HCT: human immunodeficiency virus counselling and testing; HIV: human immunodeficiency virus; MoH: Ministry of Health; MSF: Médecins Sans Frontières; NGO: nongovernmental organization; OI: opportunistic infection; PC: primary health care; PCR: polymerase chain reaction; STI: sexually transmitted infection; TB: tuberculosis; US$: United States dollars; USAID: United States Agency for International Development; VCT: voluntary counselling and testing.

a The regions shown are those defined and commonly used by the Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS. For brevity, only the first author of each publication is shown. The publications generally provide much more detail about costings, the assumptions made in evaluating costs and the drug regimens involved than can be neatly summarized here.

b Costs are shown per patient-year. They have been adjusted to the dollar values for the year 2011 and then rounded to integer values. They are financial unless indicated otherwise.

c Although the published results of this study do not state when data were collected, the published costs are given as values for the year shown here.

d Mean for first year ART across all drug regimens.

Table 10. Study on behaviour-change communications included in the systematic review.

| Region and referencea | Last year of data collection | Country | Location | No. and type of sites | Description of interventions | Empirical or modelled | Costing scope | Costing method | Mean unit cost(s), US$ (range)b |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Africa – western and central | |||||||||

| Hsu et al. (2013)52 | 2009 | Benin | National | 29 communes in 7 departments across Benin. Services assumed to be integrated | Interventions to promote safer sexual behaviour and the systematic use of condomsc | Empirical | Economic, provider perspective, costing analysis | Capital and recurrent cost framework | 26, 40, 19, 5 and 2 – per person reached – using billboards, peer education, magazines, radio and public outreach events, respectively; 23, 26 and 32 – per person reporting systematic condom use –using magazines, radio and public outreach events, respectively |

US$: United States dollars.

a The region shown is one defined and commonly used by the Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS.

b Costs have been adjusted to the dollar values for the year 2011 and then rounded to integer values.

c Interventions included billboards (56 billboard sides featuring messages regarding the prevention of human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) and adverts for condoms displayed for a period of 6 months in major cities and along highways), peer education (one-to-one or small group discussions held 5–10 times a month, led by one of 200 trained sex workers or youth peer educators, designed to raise awareness of prevention and transmission of HIV and to encourage behaviour change), a magazine (youth-oriented magazine issued about six times a year, of approximately 15 pages, covering sexual and reproductive health topics such as delaying the onset of sexual activity, fidelity, contraception and other means to prevent transmission, and communicating with partners and parents), radio broadcasts by 10 contracted radio stations (150 short broadcasts per month, each of about 30 s, on HIV prevention and transmission per month, plus themed talk show, of about 45 min, broadcast about twice a week and targeting youth and covering a variety of sexual and reproductive health topics) and public outreach events (held in local communities, hosted by a network of 16 contracted nongovernmental organizations, designed to disseminate messages via theatrical sketches, condom-use demonstrations and the projection of short videos)

Table 11. Studies on condom distribution included in the systematic review.

| Region and referencea | Last year of data collection | Country | Location | No and types of sites | Description of intervention | Empirical or modelled | Costing scope | Costing method | Mean unit cost(s), US$ (range)b |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Africa – eastern and southern | |||||||||

| Terris-Prestholt (2006)54 | 2001 | Uganda | Rural | 18 parishes with an approximate combined population of 96 000. Services were integrated | Between 1994 and mid-2000, a range of HIV-prevention interventions was evaluated as part of the Masaka intervention trial. The aim of this three-armed randomized controlled trial was to measure and compare the impact of IEC alone and IEC with STI management on reducing the incidence of HIV and other STIs at community level. All arms received VCT and the social marketing of condoms. The condom promoter distributed condoms monthly to established commercial outlets in all 18 parishes, for resale. Costings were provided for 1 495 570 condoms distributed over 4 years (1996–1999) | Empirical (primary data) | Economic, incremental, provider perspective | Step-down | 0.12 (0.10–0.16) per condom soldc |

| Terris-Prestholt (2006)55 | 2001 | United Republic of Tanzania | Rural | 10 communities, each formed of 5 or 6 villages. Overall,186 school-years, 54 health-facility participation years and 30 community years were costed. Services were integrated | The Mema kwa Vijana intervention trial was implemented by an international NGO and designed to estimate the incremental impact of an intensively developed youth intervention. The intervention had four main components: ASRH education for 3 years of primary school (in-school), community-mobilization activities and youth-friendly services to improve youth access to sexual health services, and community-based peer condom promotion and distribution. Results were provided for 3 years of intervention implementation (1999–2001) | Empirical (primary data) | Economic and financial, incremental and full, provider perspective | Combination of top-down and bottom-up | 1.87 (financial) and 1.94 (economic) per condom sold |

| Asia and Pacific | |||||||||

| Dandona (2010)56 | 2006 | India | National | 1 HIV-prevention intervention programme serving 190 599 people over 4 years | One public-funded HIV-prevention programme based on condom promotion and targeted at groups at high risk of HIV infection | Empirical (primary data) | Economic, provider perspective | Combination of top-down and bottom-up | 1.54 per person reached |

| Global | |||||||||

| Söderlund (1993)53 | 1986–1992 | Bolivia, Brazil, Cameroon, Côte d’Ivoire, Democratic Republic of the Congo, Dominican Republic, Ecuador, Ghana, Indonesia, Mexico, Morocco, Uganda, Zimbabwe | National | Not available | Case studies of operating programmes designed to promote safer sexual behaviours and condom use, either by person-to-person education or by the social marketing of condoms | Empirical | Financial, provider perspective | Capital and recurrent cost framework | 1.12, 0.54, 0.34 and 0.16 per condom distributed in Brazil, Cameroon, Uganda and Zimbabwe, respectively; 0.72, 0.24, 0.18, 0.21, 0.29, 0.13, 0.07, 0.41, 0.81 and 0.97 per condom sold in Bolivia, Côte d’Ivoire, Democratic Republic of the Congo, Dominican Republic, Ecuador, Ghana, Indonesia, Mexico, Morocco and Zimbabwe, respectively |

ASRH: adolescent sexual and reproductive health; HIV: human immunodeficiency virus; IEC: information, education and communication; NGO: nongovernmental organization; STI: sexually transmitted infection; US$: United States dollars; VCT: voluntary counselling and testing.

a The regions shown are those defined and commonly used by the Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS. For brevity, only the first author of each publication is shown. The publications generally provide much more detail about costings and the assumptions made in evaluating costs than can be neatly summarized here.

b Costs have been adjusted to the dollar values for the year 2011 and are financial unless indicated otherwise.

c The range shows the variation in annual values.

Table 12. Studies on human immunodeficiency virus counselling and testing included in the systematic review.

| Region and referencea | Last year of data collection | Country | Location | No. and type of sites | Description of interventions and models | Empirical or modelled | Costing scope | Costing method | Mean unit cost(s), US$ (range)b |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Africa – eastern and southern | |||||||||

| Kombe (2005)22 | 2005c | Ethiopia | National | 6 hospitals | Pre-test counselling, drawing blood, testing and post-test counselling | Empirical | Financial, incremental, provider perspective (costs of labour, training and supplies included) | Bottom-up | 5 per client per episode |

| Twahir (1996)57 | 1994 | Kenya | Urban | 2 clinics | A case study in which the process of applying an integrated model (in which STI and HIV/AIDS services were integrated with existing services for maternal and child health and family planning) was compared with that of applying a non-integrated model | Empirical | Financial, incremental, provider perspective | Combined top-down and bottom-up | 12 and 18 per client-visit in the integrated and non-integrated models, respectively |

| Forsythe (2002)59 | 1999 | Kenya | Rural and urban | 3 health centres | Health centres provided rapid, same-day testing. NGO-paid counsellors drew blood and then performed an initial HIV test using the Immunocomb test kit. Positive results were confirmed with the Capillus test | Empirical | Full economic and incremental financial, provider perspective (head-office and research costs included in full costs) | Top-down | 62 (economic) and 21 (financial) per VCT client |

| John (2008)60 | 2003 | Kenya | Urban | 1 ANC clinic | HCT included health education, testing and pre- and post-test counselling. Women attending their first antenatal visit were provided information, as a group, on HIV-1 infection and eMTCT interventions, and were then asked to return in 7 days, with their partners, for HIV-1 counselling and testing. Following pre-test counselling, blood was collected for rapid HIV-1 testing on site and results were disclosed on the same day. Two models were investigated: standard VCT in an ANC clinic and couple counselling for eMTCT | Empirical | Financial, incremental, provider perspective (upstream system costs and fixed costs such as rental and utilities excluded) | Bottom-up | 7·(6–9) and7 (6–9) per woman in ANC and the standard VCT and couple counselling, respectively |

| Negin (2009)62 | 2005c | Kenya | Rural | 1 local community-based organization | A 3-month curriculum for training in HIV counselling and testing. Counsellors were registered by the Government of Kenya’s National AIDS and STI Control Programme. Rapid ELISA-based testing for HIV antibodies was conducted. Home-based VCT was offered to all interested household members. Tests were conducted independently for each individual except for couples who requested to be tested together. The post-test counselling that was provided depended on the results of the HIV tests | Empirical | Financial, provider perspective | Bottom-up | 7 per person tested |

| Grabbe (2010)63 | 2006 | Kenya | National | 6 stand-alone and 6 mobile sites | Following standardized procedures, the HCT delivered by trained counsellors was free, voluntary and confidential. Finger-prick samples of blood were collected and checked for antibodies to HIV in rapid tests. Counsellors, who delivered pre-test counselling to individuals, couples, families or groups, discussed basic HIV/AIDS information, explained the HIV testing process, and discussed the clients’ risk behaviours. Immediately following rapid testing, post-test counselling was conducted with all clients to explain test results, develop personalized prevention strategies, discuss partner testing and disclosure, and offer appropriate referrals. HCT provided at free-standing, fixed centres (mostly urban or periurban and not attached to a health facility) or at mobile sites (semi-mobile containers or a fully mobile truck) | Empirical | Financial, full and incremental, provider perspective (upstream system costs excluded) | Top-down | 29 (fixed sites) and 15 (mobile sites) per HCT client |

| Liambila (2008)61 | 2007 | Kenya | Rural, urban and periurban | 23 health facilities | Two models of integrating HCT into FP services were pilot tested. The “testing” model was implemented in Nyeri district (an area with relatively few VCT sites). In this model, FP clients were educated about HIV prevention generally and HCT in particular and were then offered HCT during the same consultation, by the FP provider. The “referral” model was implemented in Thika district (an area with good accessibility to VCT services). In this model, FP clients were educated about HCT and those interested were referred to a specialized HCT service (within the same facility, at another health facility or at a stand-alone HCT centre) | Empirical | Financial, incremental, provider perspective | Combined top-down and bottom-up | 10 and 33 per client tested in the testing and referral models, respectively |

| Obure (2012)64 | 2009 | Kenya and Swaziland | Urban and rural | 28 public and private not-for-profit hospitals, health centres and SRH clinics (20 sites in Kenya, 8 in Swaziland) | HCT was provider-initiated (incorporated into routine health care – including general primary care, maternal and child health care, care for STIs and inpatient services – with pre- and post-test counselling provided by a nurse and testing conducted either by the same nurse or by a laboratory technician or lay counsellor, and counselling sometimes in groups) or client-initiated (through VCT centres, with counselling and testing provided by a lay counsellor or a nurse and generally involving one-to-one or couples counselling) | Empirical | Financial and economic, full, provider perspective (upstream system costs excluded) | Combined top-down and bottom-up | 8 (5–16) and 12 (7–20) per person tested in the provider- and client-initiated HCT, respectively |

| Sweat (2000)58 | 1998 | Kenya and United Republic of Tanzania | Urban | 1 free-standing VCT clinic in each country | Clinic-based VCT provided according to the CDC’s client-centred HIV-1 counselling model. Included personalized risk assessment and development of personalized risk-reduction plans. Serum samples tested for HIV-1 in commercial ELISA. All positive samples confirmed with a second ELISA. Inconclusive test results confirmed by western blot or immunofluorescence assay. Clients asked to return for results and counselling after 2 weeks. Additional counselling for participants who did not agree to be tested. Condom demonstration and role play provided as part of HCT. Demand created through posters, flyers and short, weekly, radio commercials | Empirical | Economic, incremental, provider perspective | Top-down | 35 (23–50) and 38 (22–63) per client in Kenya and United Republic of Tanzania, respectively |

| McMennamin (2007)94 | 2007 | Rwanda | Rural and periurban | 5 rural health centres and 1 periurban | A costing study to inform performance-based financing and contracting for HIV services in Rwanda, including unit costs for eMTCT, VCT and OI services for 2005 | Empirical | Financial, provider perspective | Bottom-up | 5 per consultation |

| Hausler (2006)66 | 2002 | South Africa | Urban and periurban | 12 community health centres, 1 primary health-care clinic and 1 STI clinic | The costs and cost–effectiveness of the ProTEST package of TB and HIV interventions were investigated in health-care facilities in Cape Town | Empirical | Economic and financial, provider perspective | Ingredients approach | 3 (2–4) and 2 (1–3) per person pre- and post-test counselled, respectively |

| McConnel (2005)65 | 2003 | South Africa | Periurban | 1 church-based, non-profit organization | Within a 2-hours period, clients received pre-test counselling, an HIV test and test results in a post-test counselling session. The results of initial tests (Efoora) were confirmed with another rapid test (Abbott Determine), eliminating expenditure on laboratory-based testing | Empirical | Financial and economic, provider perspective | Combined top-down and bottom-up | 72 (34–159) per client (financial) and 114 (49–255) (economic) |

| Terris-Prestholt (2006)54 | 1999 | Uganda | Rural | 18 parishes with community-based interventions | A three-armed randomized controlled trial in 18 parishes of the impact of the following HIV-prevention interventions: IEC (both community- and school-based); strengthened STI services; social marketing of condoms; and VCT. VCT consisted of two trained counsellors visiting communities, to provide VCT services, twice per month. From 1996–1998, HIV testing was done centrally and clients were required to return for results after 2 weeks. In 1999, rapid tests were introduced, and results were provided to clients at the same visit | Empirical | Economic, full, provider perspective (central support costs included) | Top-down | 35 (22–46) per client receiving post-test counselling |

| Tumwesigye (2010)68 | 2005 | Uganda | Rural | Homes | Home-based HCT was provided by 29 outreach teams, each consisting of a laboratory assistant and a counsellor offering HIV education and HCT. Participants could choose to be tested and receive results as individuals or as couples. In addition,170 resident parish mobilizers and village chairmen mobilized communities, supported the outreach teams, provided follow-up post-test support, encouraged the formation of parish-based HIV post-test clubs and referred those diagnosed with HIV infection to relevant service organizations | Empirical | Financial, provider perspective | Top-down | 8 per person reached with bundled services |

| Menzies (2009)67 | 2009 | Uganda | National | 4 models | In each model, HIV testing was provided in a single session using a serial HIV rapid-test algorithm. Pre-test and post-test counselling were provided, covering basic HIV/AIDS information, the testing process, risk-reduction strategies, the interpretation of positive or negative test results, partner communication and disclosure, and voluntary consent. Referral for HIV care and treatment were provided for clients found HIV-positive. Testing was free, voluntary and private, and clients were encouraged to be tested with their partners. The four models investigated were “stand-alone” (client-initiated HCT at free-standing centres), “hospital-based” (provider-initiated HCT via an opt-out approach for inpatients and outpatients), “door-to-door” (home-based, provider-initiated HCT via mobile teams) and “household-member” (same as door-to-door but targeting members of households of HIV-positive patients) | Empirical | Economic, full, provider perspective | Top-down | 21, 13, 9 and 15 per client in the standalone, hospital-based, door-to-door and household-member models, respectively |

| Bratt (2011)37 | 2009 | Zambia | Rural and urban | 12 facilities supported by the Zambian Prevention, Care and Treatment Partnership. From these 5 hospitals and 6 health centres provided human immune-deficiency virus counselling and testing services. Services were integrated | Initiating, improving and scaling up eMTCT, HCT and clinical-care services, for people living with HIV, during Antenatal Care and Perinatal Care in urban and rural settings | Empirical (resource use estimated from primary data) | Economic, full, provider perspective (costs of upstream supervision and support included) |

Combined top-down and bottom-up | 15 (9–22) and 22 (15–31) per HCT outpatient visit in the hospitals and health centres, respectively |

| Africa – western and central | |||||||||

| Kombe (2004)40 | 2004c | Nigeria | National | 5 ART sites | A programme of VCT in which initial testing was based on an ELISA and positive results were confirmed with an ELISA, a Genie2 rapid test or an Abbott Determine rapid test | Empirical (secondary data on prices of test kits) | Financial, incremental, provider perspective (upstream costs excluded) | Bottom-up | 5 per HIV-negative client and 13 per HIV-positive |

| Aliyu (2012)42 | 2010 | Nigeria | Urban and rural | 7 secondary public hospitals and 1 tertiary (4 urban and 4 rural). Services assumed to be integrated | A typical comprehensive site provided a package of HIV testing, prevention, treatment, care and support. HCT and ART service delivery points were used as cost centres for this study because each was an operational unit, contributing towards the overall cost of HIV/AIDs services in the study facilities | Empirical | Financial, provider perspective, costing analysis | Top down | 8 per client (6, 19, 6 and 10 in the secondary, tertiary, urban and rural hospitals, respectively) |

| Asia and Pacific | |||||||||