Abstract

Archaea are prokaryotic organisms that lack endomembrane structures. However, a number of hyperthermophilic members of the Kingdom Crenarchaea, including members of the Sulfolobus genus, encode homologs of the eukaryotic endosomal sorting system components Vps4 and ESCRT-III (endosomal sorting complex required for transport - III). We found that Sulfolobus ESCRT-III and Vps4 homologs underwent regulation of their expression during the cell cycle. The proteins interacted and we established the structural basis of this interaction. Furthermore, these proteins specifically localized to the mid-cell during cell division. Over-expression of a catalytically inactive mutant Vps4 in Sulfolobus resulted in the accumulation of enlarged cells, indicative of failed cell division. Thus, the archaeal ESCRT system plays a key role in cell division.

Within the archaeal domain of life, there are two principal Kingdoms, the Crenarchaea and the Euryarchaea. Studies of microbial diversity have revealed that crenarchaea are one of the most abundant forms of life on Earth (1, 2); however, we know essentially nothing about how cell division occurs in these organisms. This is of particular interest because the sequenced genomes of hyperthermophilic crenarchaeotes lack genes for members of the FtsZ/tubulin and MreB/actin superfamilies of cell division proteins (3-6). The near ubiquity of tubulins and actins underscores these proteins’ pivotal roles in cell division processes in bacteria, euryarchaea and eukarya. The absence of orthologs of these proteins in the crenarchaea has prompted us to attempt to identify the crenarchaeal cell division machinery, using species of the genus Sulfolobus as a model system. In metazoa, the ESCRT (endosomal sorting complex required for transport) system, in addition to its roles in endosomal trafficking and viral egress (7-10), plays a role in membrane abscission during cytokinesis (11-13). Most hyperthermophilic crenarchaea encode homologs of ESCRT-III components and the ATPase Vps4 (14, 15), that could potentially be involved in cell division (figs. S1 to S3). Sulfolobus encodes four ESCRT-III homologs and a single Vps4 homolog. No homologs of components of the ESCRT-0, -I or -II systems are apparent. The Vps4 gene is located within an operon-like structure with an ESCRT-III homolog and a third protein predicted to contain a coiled-coil structure (fig. S1).

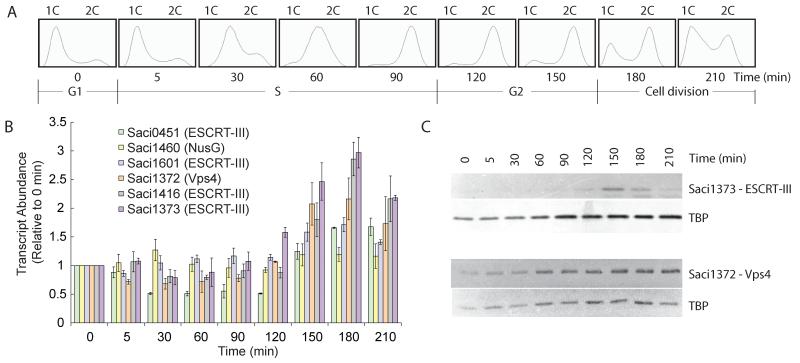

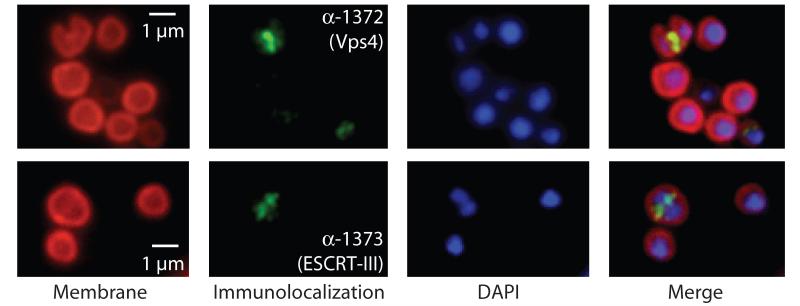

First, we profiled the cell-cycle expression of the Sulfolobus ESCRT machinery in synchronised cultures of Sulfolobus acidocaldarius (16, 17) (Fig. 1A and B). Transcripts of Saci1372 (Vps4) and ESCRT-III homologs Saci1373, −0451 and −1416 underwent a characteristic modulation, with lowest levels in S-phase-enriched populations (30-min time point) and levels peaking between three and four times higher in populations enriched for dividing cells (180 min). In agreement with this result, levels of Saci1373 (ESCRT-III) protein were highest in dividing cell populations (Fig. 1C, upper panel). In contrast, Vps4 protein remained nearly constant across the cell cycle (Fig. 1C, middle panel). Immunostaining with anti-Saci1373 (ESCRT-III) antibodies revealed a distinct sub-cellular localisation of the protein. More specifically, in cells where the two nucleoids had separated, a band or belt of Saci1373 (ESCRT-III) was detected between the two nucleoids, correlating with the site of membrane ingression (Fig. 2, figs. S5 and S6 and movie S1). Similar results are observed for Vps4 localization, although in addition to the strong staining at mid-cell, we generally observe a weaker, diffuse background distributed throughout the cell body (Fig. 2). The highly specific localisation of these proteins to the mid-cell in dividing cells suggested a role in cell division-related processes.

Fig. 1.

(A) Flow cytometric analysis of samples taken at the indicated time points during the progression of a synchronised culture of S. acidocaldarius. The positions of peaks corresponding to one chromosome content (1C) and 2C genome contents are indicated. The cell-cycle stages are indicated at the bottom.

(B) Real-time PCR measurements of transcript abundance of the indicated ESCRT-III homologs, Vps4 and a housekeeping control (the nusG transcription elongation factor). Experiments were performed in triplicate, and the standard deviation (SD) is indicated by the error bars. All samples were normalised to the level detected at 0 min.

(C) Western blot analysis of the levels of Saci1373 (ESCRT-III), Vps4 and the general transcription factor TATA box binding protein (TBP) proteins across the cell cycle. Samples were taken at the indicated times during the growth of synchronised S. acidocaldarius cultures.

Fig. 2.

Localisation of (Top) Saci1372 (Vps4) and (bottom) Saci1373 (ESCRT-III). Representative images are shown. Images show the FM4-64X staining for membrane (red), DAPI staining for DNA (blue), antibody labelling of ESCRT-III or Vps4 (green) and merged images. Scale bar, 1 μm. Additional images are shown in figs. S6 and S7 and movie S1.

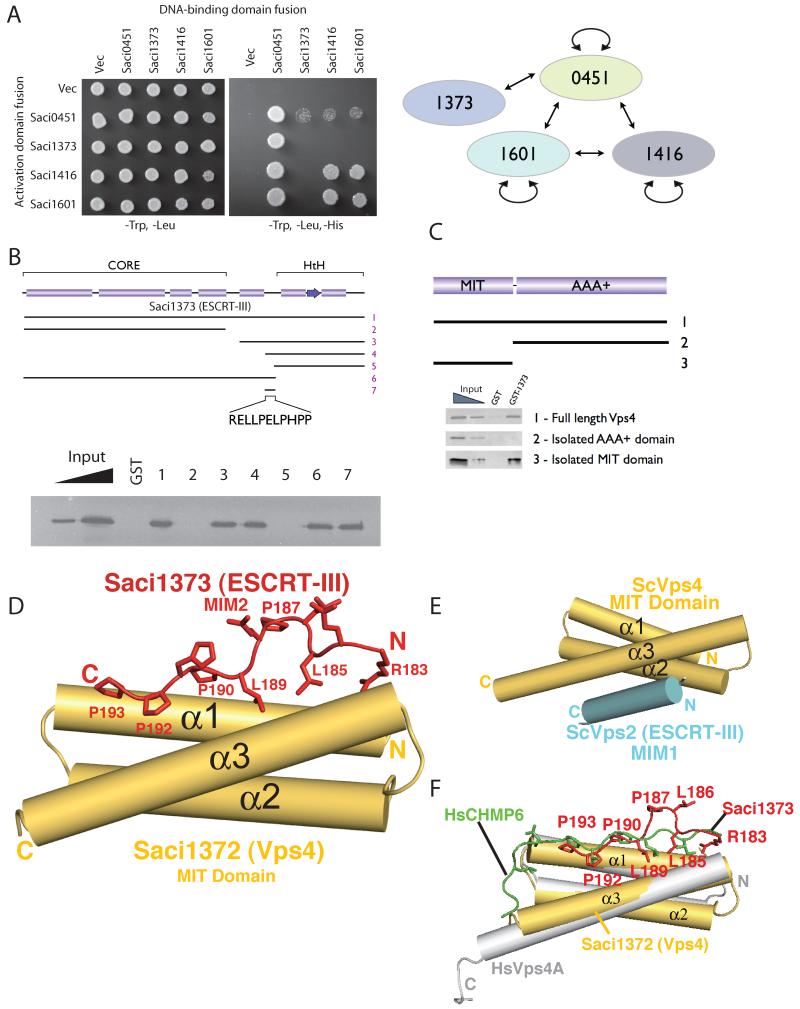

In eukaryotes, ESCRT-III family proteins are capable of both homo- and hetero-multimeric interactions resulting in the generation of protein lattices. We tested the ability of the four Sulfolobus ESCRT-III homologs to interact with one another using yeast 2-hybrid assays (Fig. 3A). A series of interactions between these proteins was detected, indicating the archaeal ESCRT-III proteins have the capacity to form an extended lattice. In eukaryotes, Vps4 plays a pivotal role in disassembling the ESCRT-III lattice and has been shown to interact with ESCRT-III proteins via the MIT domain of Vps4 and the C-terminal tails of ESCRT-IIIs. We tested whether the Saci1373 (ESCRT-III) and Vps4 proteins interact directly. Full-length (residues 1-261) Saci1373 (ESCRT-III) and Saci1372 (Vps4) did indeed interact (Fig. 3, B and C). The minimal interaction sites comprised residues 183 to 193 of Saci1373 (ESCRT-III), a notably hydrophobic and proline-rich region (Fig. 3B), and the MIT domain of Saci1372 (Vps4) (Fig. 3C). To better understand the basis of this interaction, we determined the co-crystal structure of the MIT domain of Saci1372 (Vps4) with a peptide corresponding to residues 183 to 193 of Saci1373 (ESCRT-III). The MIT domain forms a three-helix bundle and the peptide binds in an extended configuration to the groove formed between helices α1 and α3 (Fig. 3D). The residues interacting with the MIT domain constitute part of a 183-(R/K)xLLP(D/E)LPxPP-193 motif (18) present in most orthologs of Saci1373. Among the four Saci ESCRT-III-like subunits, only Saci1373 has this MIT-binding motif (fig. S2). Two other ESCRT-III-like subunits (Saci1416 and Saci0451) bound the Saci1372 (Vps4) MIT domain with lower affinity, whereas Saci1601 does not bind (fig. S7). Pro187 of this motif is a cis-Pro that forces a sharp kink in the bound peptide so that Leu186 and Pro187 have only limited contact with the MIT domain. The core residues in contact with the MIT domain (189-LP-190) are essential for maintaining interaction with the MIT domain in solution (figs. S2 and S8). This mode of interaction is distinct from the previously characterised structures of complexes of yeast and human Vps4 MIT domains with interacting peptides [MIMs (MIT-Interacting Motifs)] derived from ESCRT-III family members Vps2 and human CHMP1A and 2B (14, 19). In those structures, the MIM formed an amphipathic alpha helix that binds between α2 and α3 of the MIT domain (Fig. 3E). However, the MIM in human CHMP6 (termed MIM2) binds in an extended configuration along the groove formed by helices 1 and 3 of the MIT domain (20). Although the CHMP6 MIM2 lacks the cis-Pro equivalent of Saci1373 Pro187 and the corresponding kink of the main chain, the residues interacting with the Vps4 MIT domain and the extended main-chain conformations for these residues are essentially the same as we observe for the Saci1373 binding to the Saci1372 (Vps4) (Fig. 3F). Despite the two billion-year evolutionary gulf between Sulfolobus Saci1373 (ESCRT-III) and human CHMP6, the sequences of the MIT-interacting peptides of these two proteins are clearly conserved at the primary sequence level.

Fig. 3.

(A) Interactions between ESCRT-III proteins detected by yeast 2-hybrid analyses. Yeast containing the indicated plasmids were plated in media lacking leucine and tryptophan to select for plasmids and additionally lacking histidine to score for interactions.

(B) Identification of the minimal interaction site on Saci1373 (ESCRT-III) for binding Vps4. Glutathione S-transferase (GST) fusions of ESCRT-III fragments were used in pull-down assays with the full-length Vps4. The results of the pull-downs are shown in the lower panel. The input lanes contain 25 and 5% of input.

(C) Identification of the interaction domain of Vps4 that binds Saci1373 (ESCRT-III). GST-Saci1373 (ESCRT-III) was used in pull-down assays with the full-length (1), C-terminal AAA+ domain (2) or isolated MIT domain (3) of Vps4.

(D) A schematic representation of the interaction of Saci1373 (red) with the Saci1372 Vps4 MIT domain (yellow).

(E) An illustration of the interaction of yeast Vps4 MIT domain (yellow) with the C-terminal MIM1 motif (blue) of the yeast Vps2 ESCRT-III subunit. The MIM1 motif slots between MIT helices α2 and α3 (14).

(F) The Saci1373 MIM2 (red)/ Saci1372 MIT (yellow) interaction is closely related in structure with the CHMP6 MIM2 (green, extended)/VPS4A MIT (gray helices) interaction (20).

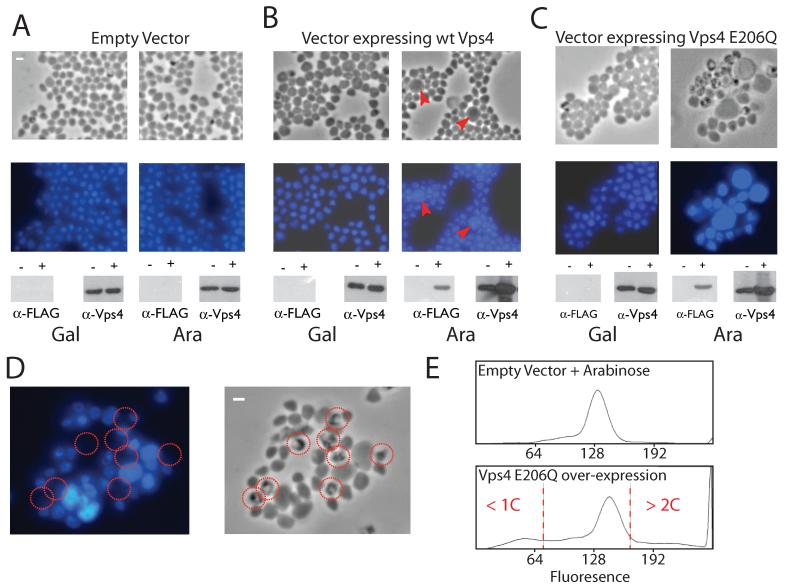

Thus, archaeal ESCRT components are cell-cycle regulated, interact via an evolutionary conserved interface, and show specific subcellular localisation to the site of membrane ingression during archaeal cell division. To test further the in vivo role of the Sulfolobus ESCRT components, we generated an episomal vector to direct arabinose-inducible expression of a target gene in Sulfolobus solfataricus (21) (figs. S9 to S11). We transformed S. solfataricus with either an empty vector or vector containing wild-type Vps4 or an ATPase defective (E206Q – “Walker B”) mutant of Vps4 (Fig. 4, A to C).

Fig. 4.

(A to C) Phase contrast and fluorescent microscopy of DAPI stained S. solfataricus cells containing either vector pRYS1 (A), pRYS1-wtVps4 (B) or pRYS1-Vps4 E206Q (C). In each panel, the left-hand images show cells grown in the repressing conditions (in the presence of galactose) and the right-hand images show cells in which expression of the plasmid-encoded gene is induced by the addition of arabinose. Red arrow-heads in (B) indicate enlarged cells with elevated DNA content. The lower panels show the results of western blotting with either antiserum to FLAG or antiserum to Vps4. The antiserum to FLAG detects only the plasmid-encoded Vps4; the antiserum to Vps4 detects both plasmid and chromosomally encoded Vps4. The − and + symbols correspond to cells before and after the addition of either galactose (Gal) or arabinose (Ara).

(D) An enlarged image of cells over-expressing Vps4 E206Q (phase contrast image on the left, fluorescent DAPI image on the right). Cells lacking discernable DAPI staining are circled in red.

(E) Flow cytometric profile of cells grown in arabinose containing either empty vector or vector over-expressing Walker B (E206Q) Vps4. Cells with less than 1C or more than 2C genome content are indicated.

Over-expression of wild-type Vps4 results in the appearance of only a small proportion of enlarged cells with elevated DNA content, indicated by red triangles in Fig. 4B. Induction of the mutant Vps4 E206Q results in a far more dramatic phenotype (Fig. 4, C and D). Considerably enlarged cells, up to four times the diameter of wild-type cells, were observed that showed intense 4′,6′-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) staining, indicative of elevated DNA content. In addition, a large number of “ghost” cells lacking DNA were seen (Fig. 4D). Flow cytometry of the cells containing over-expressed Vps4 (E206Q) revealed an aberrant profile with a significant proportion of the cells containing less than one or more than two genome equivalents. The cells with more than 2 chromosomes formed a broad continuum with non-integral genome contents, indicating that, in the absence of proper cell division, DNA replication is misregulated.

Here we have shown that Sulfolobus ESCRT system homologs play a role in the cell division process. The ESCRT system in human cells is involved in membrane abscission at the final stages of cytokinesis (12, 13). However, there is no evidence of yeast ESCRT proteins being involved in cell division, leading to speculation that this role in human cells may be a recent evolutionary acquisition. Our findings suggest that the role of the ESCRT proteins in cell division may pre-date the divergence of the crenarchaeal and eukaryotic lineages and thus be reflective of the ancestral role of this complex. Just as mammalian ESCRT-III subunits appear to have multiple roles in cell biology, the role of the archaeal ESCRT-III subunits may not be limited to cell division. Dominant-negative mammalian ESCRT-III subunits block HIV-1 budding and release (10, 22). Indeed a recent report revealed that the S. solfataricus ESCRT-III-like subunit Sso0881, the ortholog of Saci1416 (fig. S1 to 3), is associated with viral particles of the Sulfolobus turretted icosahedral virus (STIV) (23). Finally, the reduced complexity of the archaeal ESCRT apparatus provides a simplified model with which to investigate the core mechanisms of lattice formation and breakdown by this system.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank O. Perisic and I. Duggin for advice and helpful discussions, C. Mueller-Dieckmann for help with ESRF beamline ID29 and S. McCallum for flow cytometry. The work was supported by the Wellcome Trust (Grant 083639/Z/07/Z to RLW), the Edward Penley Abraham Trust (SDB) and the MRC (RLW and SDB). The coordinates for the structure reported in this work have been deposited in the Protein Data Bank (accession number 2w2u).

References

- 1.Karner MB, DeLong EF, Karl DM. Nature. 2001;409:507. doi: 10.1038/35054051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Santelli CM, et al. Nature. 2008;453:653. doi: 10.1038/nature06899. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pogliano J. Curr. Op. Cell Biol. 2008;20:19. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2007.12.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dye NA, Shapiro L. Trends Cell Biol. 2007;17:239. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2007.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Margolin W. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2005;6:862. doi: 10.1038/nrm1745. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Carballido-Lopez R, Errington J. Trends Cell Biol. 2003;13:577. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2003.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Martin-Serrano J. Traffic. 2007;8:1297. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0854.2007.00609.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Williams RL, Urbe S. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2007;8:355. doi: 10.1038/nrm2162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Piper RC, Katzmann DJ. Ann. Rev. Cell. Dev. Biol. 2007;23:519. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.23.090506.123319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hurley JH, Emr SD. Ann. Rev. Bioph. Biomol. Struct. 2006;35:277. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biophys.35.040405.102126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Spitzer C, et al. Development. 2006;133:4679. doi: 10.1242/dev.02654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Carlton JG, Martin-Serrano J. Science. 2007;316:1908. doi: 10.1126/science.1143422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Morita E, et al. EMBO J. 2007;26:4215. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601850. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Obita T, et al. Nature. 2007;449:735. doi: 10.1038/nature06171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hobel CFV, Albers SV, Driessen AJM, Lupas AN. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 2008;36:94. doi: 10.1042/BST0360094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Duggin IG, McCallum S, Bell SD. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. (USA) 2008;105:16737. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0806414105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.See supplementary methods on Science Online.

- 18.Single-letter abbreviations for the amino acid residues are as follows: D, Asp; E, Glu; H, His; K, Lys; L, Leu; P, Pro; R, Arg; and X, any amino acid.

- 19.Stuchell-Brereton MD, et al. Nature. 2007;449:740. doi: 10.1038/nature06172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kieffer C, et al. Developmental Cell. 2008;15:62. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2008.05.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Research Misconduct Found]

- 21.Lubelska JM, Jonuscheit M, Schleper C, Albers SV, Driessen AJM. Extremophiles. 2006;10:383. doi: 10.1007/s00792-006-0510-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fujii K, Hurley JH, Freed EO. Nat. Rev. Micro. 2007;5:912. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro1790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Maaty WSA, et al. J. Virol. 2006;80:7625. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00522-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.