Abstract

Despite considerable fiscal and structural support for youth service programs, research has not demonstrated consistent outcomes across participants or programs, suggesting the need to identify critical program processes. The present study addresses this need through preliminary examination of the role of program empowerment in promoting positive identity development in inner-city, African American youth participating in a pilot school-based service program. Results suggest that participants who experienced the program as empowering experienced increases in self-efficacy, sense of civic responsibility, and ethnic identity, over and above general engagement and enjoyment of the program. Preliminary exploration of differences based on participant gender suggests that some results may be stronger and more consistent for males than females. These findings provide preliminary support for the importance of theoretically grounded program processes in producing positive outcomes for youth service participants.

Keywords: empowerment, adolescent identity, positive development, community service

In 2011, federal legislation allocated over one billion dollars to service in the United States, a large percentage of which went directly to youth-focused programs (Corporation for National and Community Service, 2011). Many states also include community service requirements in their education standards and goals (Education Commission of the States, 2011) and young people have been estimated to contribute over 1.3 billion hours of service in a single year (Corporation for National and Community Service, 2006). Beyond direct benefits to the recipients, engaging youth in community service is expected to increase assets and prevent or mitigate negative outcomes in the young volunteers themselves (National Youth Leadership Council, 2010).

Unfortunately, empirical examination of program outcomes and procedures has lagged behind the proliferation of youth service programming among our nation’s youth (Billig, 2004). Further, findings from existing program evaluations are mixed (Reingold & Lenkowsky, 2010), suggesting that youth engagement in community service is not consistently beneficial and highlighting the need to examine specific factors that influence program impact (Hart, Atkins, & Donnelly, 2006). The present study is intended to address this need through preliminary evaluation of theoretically based intervention processes in a school-based community service program implemented with sixth grade African American youth attending school in a high poverty inner-city neighborhood. Specifically, we examined the extent to which youth experienced the program as empowering and how participant experience within the program related to significant change from pretest to posttest on key developmental outcomes.

Identifying and Monitoring Key Program Processes

Historically, program evaluations have focused on measuring outcomes, that is, assessing changes that occurred as a result of the intervention. While important, this emphasis on if participants change has often come at the expense of understanding how change occurs (Perepletchikova, Treat, & Kazdin, 2007). Yet evaluating program processes—how programs are implemented and received—is critical to understanding and maximizing the impact of interventions, as it promotes understanding of the relative influence of different program components and facilitates interpretation of both significant and nonsignificant findings (Steckler & Linnan, 2002). For example, if researchers find that youth engagement in a service program does not lead to an expected increase in empathy from pretest to posttest, they may conclude that the program was ineffective. However, these findings are uninformative as to why the program was ineffective, for example, was it because of the nature of the service activity, the attitude of the adult facilitators, characteristics of the young participants, a combination of each of these factors? Similarly, if significant changes in empathy from pretest to posttest were observed, one is still left with the question of what specific program components led to these significant changes.

While understanding the impact of program processes is important for all interventions, it is particularly important for service programs, as they tend to vary widely in both activities and context, each of which can play a role in what participants learn, see, and do. As such, identification of the “active ingredient” for service programs is even more complex than other types of interventions. For example, some youth service programs might have participants join a larger service effort (e.g., a walk/run to raise money for cancer research) whereas another group might design and carry out a service activity entirely on their own (e.g., write and perform a play for children suffering from cancer). Thus, service can address a range of issues, might or might not involve direct contact with those served, and might or might not be organized by the youth themselves. Because what youth actually do across service programs is likely to differ greatly, how it is done (i.e., program processes) becomes the critical point of intervention.

Defining the Critical Components of Youth Service Programs

“Youth voice” has been identified as an essential element in quality youth service programs (National Youth Leadership Council, 2008). Defined by the National Youth Leadership Council as giving young participants “a strong voice in planning, implementing, and evaluating service-learning experiences with guidance from adults,” the importance of this recommended practice has been widely accepted, yet inconsistently implemented across programs (Leeper, 2010; RMC Research Corporation, 2007). For example, service programs designed to emphasize youth voice may let youth have input, but ultimately disempower participants by placing final decision making authority with adults. Or a program might put youth in control of all elements of the service activity and neglect to recognize the need for guidance and support to maximize success. It follows that accurately implementing and evaluating this identified critical component requires that the theoretical basis be clearly articulated.

A theoretical construct closely related to youth voice is empowerment. In recent years, the term “empowerment” has been linked to success across a variety of contexts and situations and is identified as critical to youth service in particular. For example, Cargo, Grams, Ottoson, Ward, and Green (2003) documented the process by which youth involved in a service program became empowered through collaborative engagement with supportive adults. Several studies have also highlighted youth service that promotes empowerment of ethnic minorities or economically at-risk populations (e.g., Bloomberg, Ganey, Alba, Quintero, & Alcantara, 2003, Kegler et al., 2005) and there is preliminary evidence for the mediating role of program empowerment on service outcomes (Lakin & Mahoney, 2006). Research on closely associated constructs (e.g., self-efficacy, locus of control, problem solving skills, academic engagement), also supports a potential association between empowerment and positive development (Linnenbrink & Pintrich, 2002). Although this research is promising, empirical evaluations of programs grounded in empowerment theory are needed to determine the nature and extent of this construct as a mediator of program impact.

Empowerment theory

Popular views of empowerment often limit the concept to an individual’s feelings of influence and control, equating empowerment with constructs such as self-efficacy and esteem. Theories of psychological empowerment go beyond self-perceived strength to also include knowledge, skills, and behavior. Zimmerman (1995, 2000) defined psychological empowerment as composed of three components: (a) intrapersonal—one’s sense of control; (b) interactional—understanding the social/political environment and mechanisms behind power; and (c) behavioral—actions or efforts to exert control. This suggests that empowerment occurs not just on an emotional level (intrapersonal empowerment), or only through action itself (behavioral empowerment) but also through understanding systems of power and knowing how to access resources to support success (interactional empowerment; Speer & Hughey, 1995). In other words, one must know how to translate a feeling of efficacy into effective action to be truly empowered (Speer & Peterson, 2000). For example, a teenager might decide to write the mayor a letter expressing her frustration over a recent problem in her neighborhood. If writing the letter does not result in a change, the teen’s belief in her capacity to exert influence might be eroded and she will actually be less likely to engage in future civic action. As such, her limited knowledge of the factors that influence change may actually result in her feeling less empowered.

Empowerment theory shares characteristics with other important cognitive and motivational theories. For instance, the bidirectional relationship between self-perception and action is consistent with Albert Bandura’s (1978) theory of triadic reciprocity, wherein characteristics of the person and the situation affect behavior, but that behavior also influences one’s sense of self and perceptions/actions of others. Empowerment theory also shares similarities with Deci and Ryan’s (1985) self-determination theory which highlights the importance of the environment in enhancing or hindering one’s efforts toward competence and autonomy. Empowerment is distinct from these cognitive and motivational theories, however, in its emphasis on information, awareness, and skill. Specifically, feeling efficacious and having the opportunity to exert influence are necessary but not sufficient factors in promoting empowerment; one must also have the knowledge and ability to act effectively. Interventions to increase empowerment must therefore promote a strong sense of self through opportunities for control and action, but emphasis must be placed on increasing knowledge of the sociopolitical environment and skills to successfully navigate systems of power.

Empowering Youth to Change Their World: The Kids for Action Program

The program evaluated in the present study, Kids for Action, is a classroom-wide intervention intended to promote positive development in urban, minority adolescents through an empowerment-based community service project (Gullan, 2008). The manual-based program involves youth learning about community problems or concerns, identifying an issue the students want to address, and developing and carrying out a group service activity related to the issue. The goal of the program is to empower young adolescents from traditionally disenfranchised populations to successfully design and complete a collective service project across twenty 45-minute sessions over the course of one semester.

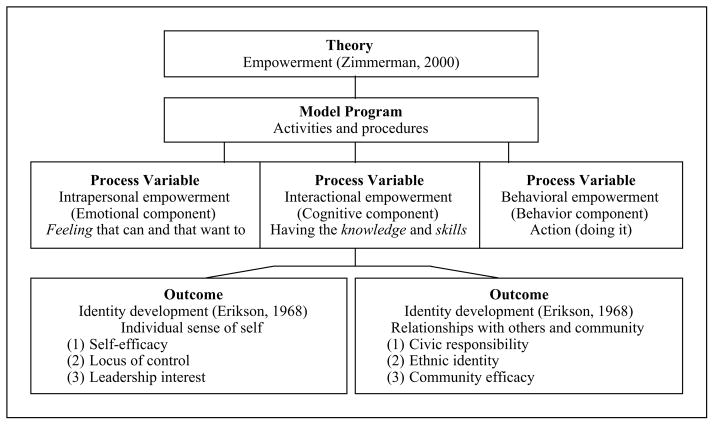

Program components and procedures are framed around each of the three aspects of Zimmerman’s psychological empowerment model, with the expectation that a community service program carried out in the framework of empowerment theory will relate to positive adolescent identity development (Figure 1; Gullan, 2008). First, the intrapersonal component of empowerment (feeling that one can be effective) is supported through helping youth identify their personal strengths and applying these skills to the design and execution of the service project. Second, interactional empowerment (having the knowledge and skills necessary for success) is addressed through teaching students strategies to garner resources and access systems of power and providing opportunities to practice these skills. Specifically, youth are taught that effective movement from feelings (a desire to do something) to action (doing something) is accomplished through the acronym PIPES, which stands for People, Ideas, Power, Events, and Stuff. People refers to the importance of collective action. For instance, a student might increase the probability of successfully starting a basketball program in his school if he is joined by his peers in the endeavor. Ideas relates to the importance of influencing how others think and feel about the issue. In the above example, this might be convincing parents and school personnel that a basketball program would be a good investment. Power is the ability to recognize people who have the greatest control over the issue, e.g., the principal would be a more effective ally than a peer for a student trying to start a school basketball program. Events reflects the need to identify and capitalize on things that happen to help or hinder your cause. Accordingly, one might be more successful in starting a basketball program after recent problems in the community highlight the need for students to have somewhere to go after school. Stuff signifies the need to identify and gather the material resources necessary for success. Thus, one would need to get basketballs, gym space, and other materials to successfully carry out the program. Finally, the behavioral component of empowerment (acting in an empowered way) is supported through allowing youth decision-making power at each stage of the process and facilitating the successful completion of the service project.

Figure 1.

Model of youth service program and desired outcomes.

Due to the variable nature of the service projects themselves, Kids for Action can appear different across classrooms, while the overall empowerment framework remains consistent. For instance, one class might choose to raise awareness about animal abuse, while another class might decide to put together care packages for soldiers. As such, activities during any given session might differ, but the process by which the youth are supported in choosing, designing, and carrying out their projects is the same (Table 1).

Table 1.

Kids for Action Program Outline: Session, Topic and Primary Activities, and Type of Empowerment Addressed.

| Session | Topic and primary activities | Type of empowerment |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Introduction to program Activity to recognize unique skills and strengths that each person brings to the table |

Intrapersonal |

| 2 | Video and discussion of African Americans who have achieved social change | Intrapersonal |

| 3 | Community mapping; understanding community problems | Behavioral |

| 4 | Introduction to “PIPES”- how to influence things that matter in your community | Interactional |

| 5 | PIPES Skill: Ideas Learn about and practice general skill building in how to influence others’ thinking Activity: Group research and presentation to class on issue they care about and want to be the focus of class service activity; each group tries to persuade others to adopt their issue |

Interactional |

| 6 | Choosing a community problem Activity: Students “put their money where their mouth is”: use play money to vote for the issue they want to address as a class |

Behavioral |

| 7 | PIPES Skill: People Discuss the importance of collective action Activity: Evaluate when one chooses to be a leader or a follower Activity: Perspective taking activity to practice empathy and working together |

Interactional |

| 8 | PIPES Skill: Politics Discuss systems of power, highlighting race and poverty and other barriers to power Activity: Practice identifying key influencers/power players in different issues |

Interactional |

| 9 | PIPES Skill: Events Learn about timing action to fit with events that happen to further (or hinder) the cause Activity: Identifying when to act and when to wait |

Interactional |

| 10 | PIPES Skill: Stuff Explore creative ways to obtain necessary material resources – considering donations, borrowing, sponsors, or fund raising |

Interaction |

| 11–20 | Use personal strengths of each class member (intrapersonal) and skills learned/practiced (interactional) in previous sessions to develop an action plan and carry out collective service activity (behavioral empowerment) | Intrapersonal, interactional, and behavioral |

The Present Study

The present study addresses the need to identify and assess critical processes of youth service programs through preliminary evaluation of Kids for Action across two pilot classrooms in a predominantly African American elementary school situated in a high poverty, inner-city neighborhood. The goal of the study was to measure the extent to which the program was experienced as empowering by participants and to examine how this theoretically based program process related to participant change from pretest to posttest on measures of key developmental outcomes. Specifically, the degree to which young participants in Kids for Action experienced the program as empowering was hypothesized to increase two primary developmental needs of adolescence, as defined by Erikson (1968): (a) to enhance personal goals, strengths, and directedness (individual component) and (b) to develop a sense of themselves in relation to others and the larger community (community component; see Figure 1 for model). Erikson’s psychosocial theory of adolescent identity development served as the framework for outcomes in the present study because this theory has consistently been identified as the foundation for research on positive outcomes in the target age group (i.e., early adolescents; Finkenauer, Engels, Meeus, & Oosterwegel, 2002). Further, positive identity development has also been linked to long-term academic, behavioral, social, and psychological outcomes, particularly for minority youth (Clements & Seidman, 2002; Spencer, 1999). Differential effects based on child gender were also explored.

The present study is unique from prior studies of youth service programs because of its focus on empirically examining the relation between a key theoretically based implementation factor (empowerment) and participants’ developmental outcomes. It was anticipated that the extent to which participants experienced the program as intended (i.e. empowering) would significantly predict targeted outcomes when controlling for preintervention scores. Process empowerment was also expected to predict outcomes over and above participants’ enjoyment and engagement in the program (i.e. acceptability). Findings from this pilot study are expected to inform the development and implementation of future school-based youth service programs.

Method

Procedures

Prior to the start of the program, all sixth grade students across two classroom at an inner-city elementary school were told about the Kids for Action program and letters from the school principal and the primary investigator were sent home to parents detailing the program and asking permission for their child to participate in the evaluation component. While all students took part in the program as part of the academic curriculum, only those who provided both parent consent and student assent completed pre- and postintervention measures. Students and parents were assured that their choice regarding participation in the evaluation component would not affect their role in the program itself or their grades or standing in school in any way.

For those with written assent/consent, a series of surveys were administered immediately prior to the program start. Each student with consent/assent then completed the same surveys immediately after 10-week, 20-session program was complete, as well as postintervention surveys of program acceptability and process empowerment. The measure of process empowerment evaluated the extent to which participants experienced the program as promoting intrapersonal, interactional, and behavioral empowerment, that is, the key factor expected to produce successful outcomes.

Participants

Fifty-seven sixth grade students participated in Kids for Action as part of their academic curriculum. Of these, pre- and postintervention surveys completed by 48 students with written parent consent and student assent were used to for program evaluation (88% consent/assent rate; 96% retention rate for those providing consent/assent). Participants were mostly African American (92%), with the remaining self-identifying as biracial. Fifty-four percent of the participants were female, and participants were 10 to 12 years of age at pretest. The majority of students lived at or below poverty level, as evidenced by community demographics and data indicating that all students at the participating school qualified for free lunches.

Outcome Measurement

Outcome measures were administered at pre- and postintervention and were intended to measure the impact of program participation on the two primary components of Erikson’s (1968) theory of youth identity development. Each of the six outcome measures was theoretically and empirically identified as belonging to one of one of these two factors (individual or community), while also representing a distinct construct (see Table 2 for preintervention correlations).

Table 2.

Correlation Between Dependent Variables at Preintervention.

| Individual factor

|

Community Factor

|

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Self-efficacy | LOC | Leadership | Community Efficacy | Civic Responsibility | Ethnic Identity | |

| Individual factor | ||||||

| Self-efficacy | — | .43** | .38** | .05 | .30* | −.02 |

| Locus of control | — | .39** | .11 | −.03 | −.02 | |

| Leadership | — | .02 | .14 | −.02 | ||

| Community factor | ||||||

| Community efficacy | — | .39** | .53** | |||

| Civic responsibility | — | .30* | ||||

| Ethnic identity | — | |||||

Note.

p ≤ .10.

p ≤ .05.

p ≤ .01.

Measures assessing individual factor

Youth development of personal strengths, goals, and directedness was assessed with self-report measures of (a) self-efficacy, (b) locus of control, and (c) leadership competence. These measures were identified to reflect adolescents striving to develop a sense of themselves as unique individuals with something to contribute to the world.

Self-efficacy was measured with the Self-Efficacy Scale (Cowen et al., 1991), a 19-item, 5-point Likert-type scale that assesses children’s feelings that they will be able to successfully manage challenges across different domains. The scale has demonstrated high internal reliability (Cowen et al., 1991) and has been found to correlate with multiple child outcomes (Hoeltje, Zubrick, Silburn, & Garton, 1996) and detect intervention impact (Lakin & Mahoney, 2006). Pilot data with students in a previous sixth grade cohort at the target school found marginal internal consistency (α = .72), high acceptability and high ease of understanding. Internal consistency in the present study was similar to prior research (α = .72).

Locus of control was measured with the Nowicki-Strickland Locus of Control Scale (NSLCS)-Short Version (Nowicki & Strickland, 1973), a 21-item survey with a bimodal (Yes/No) response scale that assesses self-perceived personal and social control. It has been widely used across different cultures (Li & Lopez, 2004) and has demonstrated validity with inner-city African American youth (Wood, Hillman, & Sawilowsky, 1996). The Kuder-Richardson-20 coefficient for the present sample was relatively low (α = .54).

Leadership interest and skills were assessed with an 8-item, 5-point Likert-type scale measure based on the leadership subscale of Zimmerman and Zahniser’s (1991) Intrapersonal Empowerment Scale for Adults. Items assess the extent to which participants are and desire to be leaders (e.g., “Other people usually follow my ideas” and “I would prefer to be a leader rather than a follower”). The scale has been used in previous research with adults and children (Lakin & Mahoney, 2006) and demonstrated high acceptability and ease of understanding during pilot administration to a cohort of sixth grade students from a previous year at the target school. The internal consistency coefficient in the present study was .63.

Measures assessing community factor

Youth reported on their sense of themselves in relation to others and the larger community with measures of (a) community efficacy, (b) civic responsibility, and (c) ethnic identity and pride. These measures were identified to assess the second primary goal of adolescent development, per Erikson’s (1968) psychosocial development theory: a feeling that one has a place in the world and in relation to others. Due to the nature of the intervention (service) and the target population (minority, inner-city youth), measures related to civic engagement and ethnic belonging were the focus of this construct. Thus, it was expected that these aspects of one’s relationship to broader society would be most important and most impacted in a service program for urban, African American youth.

Community efficacy (participant sense of personal power in community issues) was measured with a 10-item, 4-point Likert-type scale created for the present study. Items address the extent to which respondents feel they are able to impact community problems or issues (e.g., “I can do something about problems with gun violence” and “I can do something about litter, graffiti or dirtiness”). Pilot data with sixth grade students from a previous year in the target school found borderline internal consistency (α = .72), high acceptability, significant correlations with related constructs (e.g., trust and policy control) and high ease of understanding. Internal consistency in the present study was moderate (α = .83).

Civic responsibility was measured with a 10-item measure asking respondents to indicate on a 5-point Likert-type scale their feelings of personal responsibility for helping those in need or working for worthy causes. This scale was previously used in published research (Lakin & Mahoney, 2006). Pilot data with sixth grade students from a previous year in the target school demonstrated moderate internal consistency (α = .82), high acceptability, strong correlations with measures of related constructs (e.g., leadership, collective action), and high ease of understanding. Internal consistency in the present study was borderline (α = .69).

Ethnic identity was measured with the 12-item version of Phinney’s Multigroup Ethnic Identity Measure (MEIM; Roberts, Phinney, Masse, Chen, Roberts, & Romero, 1999). This is a 4-point Likert-type scale measure that assesses youth engagement and pride in their ethnic identity (e.g., “I have a clear sense of my ethnic background and what it means to me” and “I am happy that I am a member of the group I belong to”). The scale has been widely used across numerous studies and populations (Phinney, 1992; Roberts et al., 1999). Pilot data with sixth grade students from a previous year in the target school found satisfactory internal consistency (α = .77), strong correlations with other measures of ethnic identity, high acceptability, and high ease of understanding. Internal consistency in the present study was satisfactory (α = .76).

Process Measurement

Process measures were administered at posttest only, with the goal of assessing the extent to which the program was experienced as intended and to evaluate the relation between these factors and program outcomes.

Key process factor: Program empowerment

The extent to which the program was experienced by participants as empowering was assessed with a measure of process empowerment developed for the present study. First, items were created to reflect the three components of Zimmerman’s (2000) empowerment theory (intrapersonal, interactional, and behavioral) with wording chosen to be appropriate for young adolescents and relevant to youth engaged in a collective community service program. Items were then reviewed by two experts in theory, assessment, and community-based interventions related to positive development in high risk youth. Youth representatives from the target population also provided extensive feedback on readability and content area. Information from these key stakeholders was integrated into a final 21-item measure assessing process empowerment on a 4-point Likert-type scale used in the present study. Seven items assessed participants’ perception of the program’s success in promoting intrapersonal empowerment (personal control and influence), for example, “In Kids for Action, I had a say in how things went” and “In Kids for Action, I was able to get others to see my point of view” (α = .64). Eleven items assessed interactional empowerment (learning how to access resources), for example, “In Kids for Action, I learned how to get others to help me accomplish my goals” and “In Kids for Action, I learned how to get the necessary materials to accomplish my goals, such as money or supplies” (α = .87). Three items assessed behavioral empowerment (doing things that are empowering), for example, “In Kids for Action, I did things to impact my school or community” and “I was active member of Kids for Action” (α = .73).

Correlations between factors were significant for intrapersonal and interactional empowerment (r = .47, p < .01) and intrapersonal and behavioral empowerment (r = .51, p < .01), but not between interactional and behavioral empowerment (r = .09, p = .54). Internal consistency for the overall scale was moderate (α = .86).

Overall interest and engagement in the program

Program acceptability was measured with an 18-item, 4 point Likert scale based on Leff et al.’s program acceptability measure, which has demonstrated reliability and validity across numerous studies (Leff et al., 2010). General items were the same as in previous research (e.g., “I am glad that this program was part of my regular school week”). For items assessing program-specific content, question stems remained the same (e.g., “I liked … “), while the activity was specific to Kids for Action (e.g., “ … talking with my classmates about different issues that affect my community”). Internal consistency for the scale was moderate (α = .88).

Results

Pre- to Posttest Change

Initial paired-sample t-tests were conducted for each outcome variable (self-efficacy, locus of control, leadership competence, community efficacy, civic responsibility, and ethnic identity) as a preliminary evaluation of change from pre- to postintervention on each variable.

For five out of the six outcomes, there was no significant change from pre- to postintervention, adjusting for multiple comparisons (p < .001). For one outcome, civic responsibility, the t-test was significant, but with an effect opposite of what was expected, that is, showing a decline in participants’ self-reported civic responsibility from pre- to postintervention (pretest M: 41.3(5.3); posttest M: 38.3(6.3); t = 3.7, p < .001).

Program Process Experience and Outcome Findings

Results related to overall process empowerment

Separate hierarchical linear regression analyses were conducted for each outcome variable in order to evaluate the relationship between participants’ self-reported experience of the program as promoting empowerment and posttest ratings of all outcome measures, controlling for pretest scores, and overall program acceptability. To account for the effect of preintervention scores, pretest rating on the outcome variable (self-efficacy, locus of control, leadership, civic responsibility, community efficacy, or ethnic identity) was entered as an independent variable in block one. Postintervention reports on program acceptability were also entered in as an independent variable in block one. Thus, while program acceptability was a process variable, it was expected that controlling for overall program acceptability would create a more rigorous test of program empowerment. As such, participant report on the program empowerment process variable was entered as an independent variable in block two. The dependent variable was the corresponding report on the outcome variable at posttest. It was hypothesized that participant report on the extent to which they experienced the program as empowering would predict posttest scores on the dependent variables over and above their pretest scores on the same measure as well as their rating of overall program acceptability. Hierarchical regression analyses were also run separately for boys versus girls as a preliminary investigation of potential differences based on child gender.

In terms of the individual factor of identity development (self-efficacy, locus of control, and leadership competence), results indicated that participant reports on program empowerment overall (intrapersonal, interactional, and behavioral empowerment combined) predicted 9% of the variance in participants’ postintervention self-efficacy, over and above pretest self-efficacy and participant ratings of overall program acceptability (Table 3). Participant reports on program empowerment did not significantly predict additional variance in posttest scores on locus of control or leadership competence. When results were compared for boys versus girls, it appeared that the effects on self-efficacy were stronger for females (11% predicted variance, p < .10) than males (1% predicted variance, n.s.; Table 3).

Table 3.

Beta Coefficients and Change in R2 Representing Impact of Program Empowerment After Controlling for Overall Program Acceptability in Hierarchical Regression Analyses.

| Total sample (N = 48)

|

Females (N = 26)

|

Males (N = 22)

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| β | R2 Δ | β | R2 Δ | β | R2 Δ | |

| Individual factor | ||||||

| Leadership | −.05 | .00 | .02 | .00 | −.18 | .01 |

| Self-efficacy | .35* | .09* | .37† | .11† | .11 | .01 |

| Locus of control | .00 | .07 | .19 | .04 | −.31 | .04 |

| Community factor | ||||||

| Community efficacy | .08† | .05† | −.11 | .01 | .54* | .13* |

| Civic responsibility | .31** | .08** | .13 | .02 | .46* | .10* |

| Ethic identity | .29* | .07* | .24 | .06 | .67* | .18* |

Note.

p ≤ .10.

p ≤ .05.

p ≤ .01.

Results on the community factor of identity development (civic responsibility, ethnic identity, and community efficacy) indicated that participant reports on program empowerment overall predicted 8% additional variance in participants’ postintervention scores on civic responsibility (intent to be involved in future community action), after controlling for pretest scores and overall program acceptability (Table 3). Participant ratings on program empowerment also predicted 7% additional variance in ethnic identity with a trend toward predicting community efficacy (feeling that one can make a difference related to community problems and issues; 5% additional variance explained, p < .10). Preliminary exploration of gender differences indicated that results for all three components of the community factor were significant for males (13%, 10%, and 18% of variance predicted in community efficacy, civic responsibility, and ethnic identity, respectively; p < .05 for each) but not females (n.s. for all three variables).

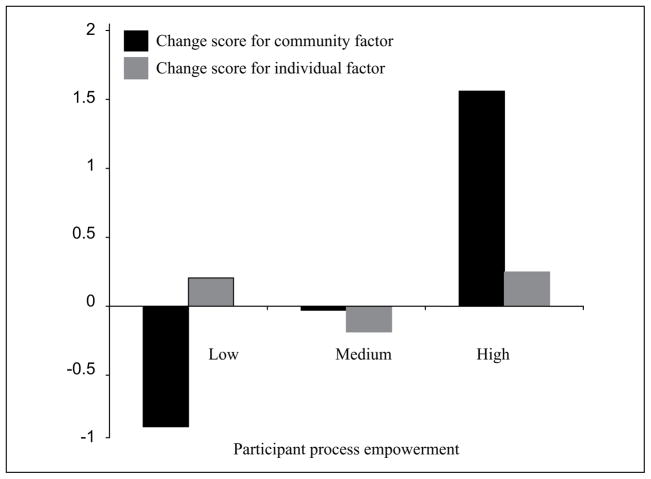

To further illustrate the importance of program empowerment, the impact of this key theoretical component across each factor is illustrated in Figure 2, which depicts change in both individual and community factors for youth who experienced the program as low, medium, or high on empowerment. Thus, mean scores on all three community variables and all three individual variables were converted into z-scores and combined with other measures in the factor. Mean outcomes for participants who reported experiencing the program as low, medium, or high in promoting empowerment were then charted. Across both factors, positive change from pre to posttest appeared greater for individuals who experienced the program as highly empowering.

Figure 2.

Mean z-score change from pre- to posttest on individual and community factors for participants low, medium, and high in empowerment.

Results related to three factors of process empowerment

As a preliminary examination of specific aspects of the empowering process, hierarchical regression analyses were conducted for each outcome variable with participant ratings of the extent to which the program promoted intrapersonal, interactional, and behavioral empowerment entered separately in block 2. Results of these analyses were used as a preliminary means to explore the relative importance of the three types of empowerment.

When evaluating the role of program empowerment separately for intrapersonal, interactional, and behavioral empowerment, participants’ experience of the program as promoting behavioral empowerment (i.e. provided opportunities to act in an empowered way) was the strongest and most consistent predictor of overall posttest scores on the individual factor (controlling for pretest scores; Table 4). Behavioral empowerment also predicted civic responsibility. Participant experience of the program as promoting intrapersonal empowerment (allowed personal control and influence during the project) was a significant predictor of postintervention self-efficacy and ethnic identity. Participant experience of the program as promoting the interactional component of empowerment (i.e. increased knowledge and skills to promote effectiveness) did not significantly predict posttest scores when controlling for pretest.

Table 4.

Beta Coefficients Representing Impact of Three Components of Program Empowerment in Hierarchical Regression Analyses.

| Outcome | Intrapersonal empowerment

|

Interactional empowerment

|

Behavioral empowerment

|

|---|---|---|---|

| β | β | β | |

| Individual factor | |||

| Leadership | .10 | −.18 | .24† |

| Self-efficacy | .32* | −.04 | .37** |

| Locus of control | .29 | −.11 | −.06 |

| Community factor | |||

| Community efficacy | .03 | .20 | .28† |

| Civic responsibility | .25† | .03 | .40*** |

| Ethic identity | .37* | .08 | .03 |

Note.

p ≤ .10.

p ≤ .05.

p ≤ .01.

p ≤ .001.

Discussion

The present study addresses the need to identify effective practices in school-based community service programs through preliminary evaluation of key program processes in a service program piloted across two classrooms. The program was intended to influence youth sense of themselves (i.e., self efficacy, locus of control, and leadership) and connection to others (i.e., community efficacy, civic responsibility, and ethnic identity), two primary components of Erik Erikson’s (1968) theory of adolescent identity development.

Initial findings indicated no significant pre- to postintervention change on key outcome variables, with the exception of civic responsibility, which actually declined over time. The interpretation of these findings related to overall change from pre- to postintervention is in part limited by the absence of a comparison group. Therefore it is possible that students may naturally decline in these variables over time, and that the program prevented or mitigated these natural declines. In addition, these preliminary analyses did not take into account individual differences at pretest and differences in how the program was experienced across participants. Thus, findings from the hierarchical regression analyses allow us to more closely examine what may be happening, controlling for pretest scores on outcome variables and highlighting the role of process variables in producing significant change. Findings from this more nuanced evaluation suggest that the extent to which participants experienced the program as empowering predicted a significant amount of the variance in posttest scores across a number of developmental outcomes. In addition, the role of the empowering process was found to relate to participant outcomes over and above their enjoyment and engagement in the program (i.e., acceptability). These findings support the expectation that it is not taking part in a program alone that produces effects (all participants completed the program), but instead it is how the program is experienced by the participant (i.e., empowerment process) that is critical to its influence. In other words, findings from this study support the contention that program processes matter, and that evaluating outcomes alone can be uninformative or even misleading.

Additional analyses were conducted as a preliminary means of examining the relative influence of each of the three components of Zimmerman’s (2000) empowerment construct. Results pointed to behavioral empowerment as the strongest and most consistent predictor of outcomes, particularly within the individual factor. Thus, participants who reported actively participating in making a difference through the service program also reported greater self-efficacy and leadership competence at posttest (controlling for pretest scores and program acceptability). Behavioral empowerment was also a relatively strong predictor of community efficacy and civic responsibility, two key community-related outcomes. Intrapersonal empowerment (feeling that one had control and influence in how the activity was carried out) was a predictor of both individual and community outcomes. Interactional empowerment, however, was not a predictor of individual or community outcomes. In other words, the extent to which participants reported that the program taught them the skills to be successful (e.g., how to access resources, the importance of collective action, and how to persuade others) did not predict significant variance in posttest scores. These results should be interpreted with great caution, however, given the small sample size and potential for error when considering multiple predictors.

Finally, preliminary investigation on differences based on gender suggested that the impact of program empowerment on females may have driven the findings for self-efficacy while program empowerment related strongly and consistently to components of the community factor (community efficacy, civic responsibility, and ethnic identity) for males, but not females. Given that previous research on service programs, empowerment, and related constructs has demonstrated significant effects across genders and that the present program was implemented with males and females together, it is unclear why there may have been differential effects based on the gender of the participant. One possibility is that within the context of this already high risk population, males are particularly vulnerable (Thomas & Stevenson, 2009). With vulnerability, however, may also come the opportunity for greatest benefit. Thus, the empowering aspect of the program might have wielded a particularly strong prosocial influence on males who may be less likely to have such an experience in school or other contexts. While compelling, these findings are based on a very small sample of males and future research is needed to validate and explore potential reasons for these findings.

Implications for Practice

The proliferation of service programs across our nation necessitates a clear understanding of the process by which these programs should be implemented. Theoretical-grounding is particularly critical to guiding program activities and maximizing impact. Identifying and measuring what happens within the context of the program itself not only has the potential to enhance results, but is critical to comprehensive understanding of program outcomes (Bellg et al., 2004). Findings from the present study illustrate this point: while program participants did not appear to change based on pre- and postintervention measure of outcome variables, examining the role of participant report on their experience in the program revealed that those who felt the program was empowering actually did improve on a number of outcome measures, even when controlling for their overall enjoyment and engagement in the program. These findings suggest that in addition to ensuring that participants are engaged and interested in the program (i.e., acceptability), those designing and implementing service interventions might benefit from carrying out the program in a way that is empowering for the participating youth. Examination of more specific aspects of program empowerment (intrapersonal, interactional, and behavioral) further informed our understanding, as it provided information on the precise aspects of program empowerment that seemed to matter the most.

Findings related to empowerment may be particularly relevant to programs for youth from traditionally disenfranchised populations, such as the urban poor. Males from these high risk neighborhoods might also be a key target population. The fact that not all participants in the present study experienced the program as empowering and individual experience related to posttest ratings on outcome measures also suggests that one cannot assume empowerment has been achieved simply because it is intended. Indeed, the program evaluated in the present study was specifically designed to be carried out in an empowering way, yet not all participants experienced it as such. Thus, while even the most carefully planned programs will not be received similarly across all participants, efforts to increase the number of participants that experience the program as intended as well as evaluation of the extent to which this occurs should be ongoing. Indeed, the present findings highlight the need to extend the evaluation of process variables even further, such that researchers and interventionist can fully understand how programs are implemented and received by participants.

Limitations and Future Directions

The present study provides important preliminary information on factors related to effective youth service program design and implementation. However, several methodological limitations caution against over-interpretation of the findings. First, there was no comparison group, thereby precluding isolation of program effects. Indeed, while the program did not produce overall increases in outcome variables from pre- to postintervention, it is possible that participation prevented natural declines that often occur for youth in the target age range (Lakin & Mahoney, 2006). Second, while the measures used in the present study had previously established reliability and validity across diverse populations, some had borderline acceptable levels of internal reliability in the present study (ranging from .69 to .83) and the measure assessing locus of control had a particularly low reliability coefficient (.54). It is possible that the binary nature of the locus of control scale placed an artificial boundary on this measurement, and utilizing the short version of the scale might have also limited its alpha coefficient (Schmitt, 1996). Regardless, this limited internal consistency should be considered when interpreting results.

An additional methodological limitation is that the posttest evaluation of outcome and process variables was done concurrently, making it is impossible to establish direction of effect. Finally, the study sample is limited in both size and participant characteristics and it is possible that factors identified as critical to students from a traditionally disenfranchised population (e.g., empowerment for inner-city, minority youth) might be less relevant for youth from a different ethnic/racial or socioeconomic background. Replication of this pilot study with a larger sample of classrooms across a range of schools is needed to validate these preliminary findings. A larger sample would also allow for further exploration of the role of participant gender.

In addition to addressing the methodological limitations, there were two unexpected findings in the present study that might be informative to future intervention and research related to youth service. First, results within the present sample suggest that the program did not impact all participants equally, as the extent to which participants experienced the program as empowering was a predictor of several outcomes. While this supports the primary hypothesis for the study (that process empowerment matters in producing outcomes), it raises the question of why some students experienced the program as intended, while others did not. Although one might say that it is the nature of interventions that engagement levels will vary, the finding that process empowerment predicted outcomes over and above overall program acceptability suggests that promoting empowerment is distinct from general engagement and enjoyment. Future research should explore what factors predict participants’ experience of the program as empowering and how these might be addressed. For example, interviews or focus groups with participants across the spectrum of empowerment might provide insight on factors that influence student experience in the program. This information could then be used to develop interventions that more effectively engage and empower all participants.

Another unexpected finding was that analyses conducted separately for each of the three aspects of empowerment suggested minimal relation between participant ratings of interactional empowerment and program outcomes. In other words, the extent to which participants reported that the program taught them how to identify resources and overcome barriers to effectively navigate systems of power did not uniquely relate to developmental outcomes. One potential reason for this is that the questions used to assess interactional empowerment might not have effectively captured the construct. Further research is needed to establish the psychometric properties of the process empowerment measure developed for the present study and make the necessary changes to improve reliability and validity of each of the subscales.

It is also possible that the service activities within the present study did not require extensive interactional empowerment skills. Specifically, students in one intervention classroom chose to conduct a food drive for a local homeless shelter and students in the other made gifts and wrote and performed a play for residents of a local senior center. While each project was entirely student-led and required gathering of resources and obtaining permission from authority figures, these activities did not necessitate navigating complex systems of power or overcoming significant barriers. Projects related to political or civic action that involves more controversial or systemic change might relate to greater influence of this aspect of empowerment. Thus, had students decided they wanted to address school policy or a “hot button” political issue, the cognitive component of empowerment might have been more relevant and impactful.

Summary and Conclusion

The present study is a preliminary effort to understand the role of a key intervention process—the extent to which the program was experienced as empowering—in predicting outcomes of a service program for inner-city, minority youth. Findings from this study suggest that participant empowerment was an important aspect of the program, over and above general enjoyment and engagement. As such, youth who experienced the service program as promoting their sense of control and influence and providing opportunities for active engagement experienced more positive developmental effects. In contrast, youth who reported a less program empowerment did not appear to experience the same benefit, despite participating in—and often liking—the program itself.

These preliminary findings suggest that for the tremendous amount of time and resources put into youth service programs in our schools and across our nation is to be used effectively, it is imperative that close attention be paid not only to outcomes, but to the process by which programs are implemented and received. Empowerment may be a particularly important process factor, especially for youth from high risk populations. Indeed consideration of the empowering process in service program design and evaluation will not only benefit young participants in service, but will also lead to more effective use of the tremendous time and resources dedicated to this type of programming across our nation.

Acknowledgments

Funding

The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: The present study was funded by Dr. Gullan’s Kirschstein National Service Award from the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development/National Institutes of Health (F32 HD052579-01), which she received as a postdoctoral fellow at The Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia.

Biographies

Rebecca L. Gullan, PhD, is an assistant professor of psychology in the Division of Behavioral and Social Sciences at Gwynedd-Mercy College. She served on the Editorial Board of School Psychology Quarterly and is an ad hoc reviewer for several journals. Her research focuses on identity, empowerment, and sense of belonging in adolescents and young adults.

Thomas J. Power is a professor of school psychology in the Department of Pediatrics at the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia and the University of Pennsylvania School of Medicine. He has been the principal investigator for grants funded by the National Institutes of Health and the Department of Education and was the editor of School Psychology Review. He also serves as the director for the Center for the Management of ADHD and chief psychologist of the Department of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences at The Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia.

Stephen S. Leff, PhD, is an associate professor of clinical psychology in the Department of Pediatrics at the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia and the University of Pennsylvania School of Medicine. He has been the principal investigator of four NIH-funded grants, all of which related to the use of partnership-based methods in the development, implementation, and evaluation of aggression prevention programs and assessment tools in the urban schools. He also serves as a coinvestigator for the CDC-funded Philadelphia Collaborative Violence Prevention. He is on the Editorial Board of School Psychology Review and is an ad hoc reviewer for several journals.

Footnotes

Reprints and permissions: sagepub.com/journalsPermissions.nav

Declaration of Conflicting Interests

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

References

- Bandura A. The self system in reciprocal determinism. American Psychologist. 1978;33:344–358. doi: 10.1037//0003-066X.33.4.344. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bellg AJ, Borrelli B, Resnick B, Hecht J, Minicucci DS, Ory M, Czajkowski S. Enhancing treatment fidelity in health behavior change studies: Best practices and recommendations from the NIH behavior change consortium. Health Psychology. 2004;23:443–451. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.23.5.443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Billig SH. National Youth Leadership Council, editor. Growing to greatness 2004. St. Paul, MN: NYLC; 2004. Heads, hearts, hands: The research on K-12 service-learning; pp. 12–25. [Google Scholar]

- Bloomberg L, Ganey A, Alba V, Quintero G, Alcantara LA. Chicano-Latino youth leadership institute: An asset-based program for youth. American Journal of Health Behavior. 2003;27(Supplement 1):S45–S54. doi: 10.5993/AJHB.27.1.s1.5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cargo M, Grams GD, Ottoson JM, Ward P, Green LW. Empowerment as fostering positive youth development. American Journal of Health Behavior. 2003;27(Supplement 1):S66–S79. doi: 10.5993/AJHB.27.1.s1.7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clements P, Seidman E. The ecology of middle grades schools and possible selves. In: Brinthaupt TM, Lipka RP, editors. Understanding early adolescent self and identity: Applications and interventions. Albany: SUNY Press; 2002. pp. 133–164. [Google Scholar]

- Corporation for National and Community Service. Educating for active citizenship: Service-learning, school-based service, and civic engagement. Washington, DC: 2006. Mar, (Brief 2 in the Youth Helping America Series) [Google Scholar]

- Corporation for National and Community Service. Fiscal year 2011 budget. 2011 Apr 15; Retrieved from www.nationalservice.org/about/budget/2011.asp.

- Cowen EL, Work WC, Hightower AD, Wyman PA, Parker GR, Lotyczewski BS. Toward the development of a measure of perceived self-efficacy in children. Journal of Clinical Child Psychology. 1991;20:169–178. doi: 10.1207/s15374424jccp2002_8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Deci EL, Ryan RM. Intrinsic motivation and self-determination in human behavior. New York, NY: Plenum; 1985. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Education Commission of the States. Service-learning/community service in standards and/or frameworks. 2011 Retrieved from http://www.ecs.org/html/educationIssues/ServiceLearning/SLDB_intro_sf.asp.

- Erikson EH. Identity: Youth and crisis. Oxford, UK: Norton & Co; 1968. [Google Scholar]

- Finkenauer C, Engels RC, Meeus W, Oosterwegel A. Self and identity in early adolescence. In: Brinthaupt TM, Lipka RP, editors. Understanding early adolescent self and identity: Applications and interventions. Albany: SUNY Press; 2002. pp. 25–56. [Google Scholar]

- Gullan RL. Developing empirically-based community service programs for diverse youth: An illustration; Paper presented at the National Association of School Psychologists Annual Convention; New Orleans. 2008. Feb, [Google Scholar]

- Hart D, Atkins R, Donnelly TM. Community service and moral development. In: Killen M, Smetana J, editors. Handbook of moral development. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Earlbaum; 2006. pp. 633–656. [Google Scholar]

- Hoeltje CO, Zubrick SR, Silburn SR, Garton AF. Generalized self-efficacy: Family and adjustment correlates. Journal of Clinical Child Psychology. 1996;25:446–453. [Google Scholar]

- Kegler MC, Williams C, Cassell CM, Santelli J, Kegler SR, Montgomery SB, Hunt SC. Mobilizing communities for teen pregnancy prevention: Associations between coalition characteristics and perceived accomplishments. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2005;37:S31–S41. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2005.05.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lakin R, Mahoney A. Empowering youth to change their world: Identifying key components of a community service program to promote positive development. Journal of School Psychology. 2006;44:513–531. doi: 10.1016/j.jsp.2006.06.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Leeper TJ. Youth voice research: Findings, gaps and trends. 2010 Retrieved from http://lift.nylc.org/

- Leff SS, Waasdorp TE, Paskewich B, Gullan RL, Jawad A, MacEvoy JP, Power TJ. The preventing relational aggression in schools everyday (PRAISE) program: A preliminary evaluation of acceptability and impact. School Psychology Review. 2010;39:569–587. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li HCW, Lopez V. Chinese translation and validation of the Nowicki-Strickland locus of control scale for children. International Journal of Nursing Studies. 2004;41:463–469. doi: 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2003.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steckler A, Linnan L. Process evaluation for public health interventions and research. In: Steckler A, Linnan L, editors. Process evaluation for public health interventions and research. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass; 2002. pp. 1–23. [Google Scholar]

- Linnenbrink EA, Pintrich R. Motivation as an enabler of academic success. School Psychology Review. 2002;31:313–327. doi: 10.1016/B978-012750053-9/50012-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Muscott HS. A review and analysis of service-learning programs involving students with emotional/behavioral disorders. Education and Treatment of Children. 2000;23:346–368. [Google Scholar]

- National Youth Leadership Council. Growing to greatness 2010. 2010 Retrieved from www.nylc.org.

- National Youth Leadership Council. K-12 service-learning standards for quality practice. 2008 Retrieved from www.nylc.org.

- Nowicki S, Strickland B. A locus of control scale for children. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1973;42:148–155. doi: 10.1037/h0033978. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Perepletchikova F, Treat TA, Kazdin AE. Treatment integrity in psychotherapy research: Analysis of the studies and examination of the associated factors. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2007;75:829–841. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.75.6.829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phinney JS. A multigroup ethnic identity measure: A new scale for use with diverse groups. Journal of Adolescent Research. 1992;7:156–176. doi: 10.1177/074355489272003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Reingold DA, Lenkowsky L. The future of national service. Public Administration Review. 2010;70:S114–S121. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-6210.2010.02253.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- RMC Research Corporation. Improving outcomes for K-12 service learning participants. Scotts Valley, CA: National Service-Learning Clearinghouse; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Roberts R, Phinney JS, Masse CL, Chen YR, Roberts CR, Romero A. The structure of ethnic identity of young adolescents from diverse ethnocultural groups. Journal of Early Adolescence. 1999;19:301–322. doi: 10.1177/0272431699019003001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Schmitt N. Uses and abuses of coefficient alphas. Psychological Assessment. 1996;8:350–353. doi: g10.1037//1040-3590.8.4.350. [Google Scholar]

- Speer PW, Hughey J. Community organizing: An ecological route to empowerment and power. American Journal of Community Psychology. 1995;23:729–748. doi: 10.1007/BF02506989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Speer PW, Peterson NA. Psychometric properties of an empowerment scale: Testing cognitive, emotional, and behavioral domains. Social Work Research. 2000;24:109–118. doi: 10.1093/swr/24.2.109. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Spencer MB. Social and cultural influences on school adjustment: The application of an identity-focused cultural ecological perspective. Educational Psychologist. 1999;34(1):43–57. doi: 10.1207/s15326985ep3401_4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas D, Stevenson HC. Gender risks and education: The particularly classroom challenges of urban, low-income African American boys. Review of Research in Education. 2009;33:160–180. doi: 10.3102/0091732X08327164. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wood PC, Hillman SB, Sawilowsky SS. Locus of control, self-concept, and self-esteem among at-risk African-American adolescents. Adolescence. 1996;31(123):597–604. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zimmerman MA. Psychological empowerment: Issues and illustrations. American Journal of Community Psychology. 1995;23:581–599. doi: 10.1007/BF02506983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zimmerman MA. Empowerment theory. In: Rappaport J, Seidman E, editors. Handbook of community psychology. New York, NY: Kluwer Academic/Plenum; 2000. pp. 43–63. [Google Scholar]

- Zimmerman MA, Zahniser JH. Refinements of sphere-specific measures of perceived control: Development of a sociopolitical control scale. Journal of Community Psychology. 1991;19:189–204. doi: 10.1002/1520-6629(199104)19:2<189::AID-JCOP2290190210>3.0.CO;2-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]