Parkinson disease (PD) is a disabling neurodegenerative disease for which current treatments are suboptimal. As exercise is generally safe, inexpensive, and associated with secondary benefits, interest in exercise as a treatment for the motorsymptomsof thedisease is increasing. In this issue of the journal, Shulman and colleagues1 offer compelling evidence that exercise can improve gait and fitnessamongindividuals with PD. This research adds to the evidence regarding the value of interventions for PD beyond medications and surgery and offers an opportunity for patients to be active participants in their care.

Shulman et al performed a comparative, prospective, randomized, single-blinded clinical trial of 3 types of exercise among patients with PD and gait impairment. Sixtyseven patients were randomized to either lower-intensity treadmill exercise, higher-intensity treadmill exercise, or a combination of stretching and resistance training. For their primary outcome of gait speed, all training types increased distance walked in 6 minutes at 4 months, but lower-intensity treadmill exercise led to the greatest increases. For their secondary outcome of cardiovascular fitness, both treadmill groups demonstrated improvement. In contrast, the stretching-resistance group improved muscle strength and motor scores on the Unified Parkinson Disease Rating Scale. The authors conclude that all 3 types of exercise have benefits, and patients may benefit most from a combination of lower-intensity training and stretching and resistance.

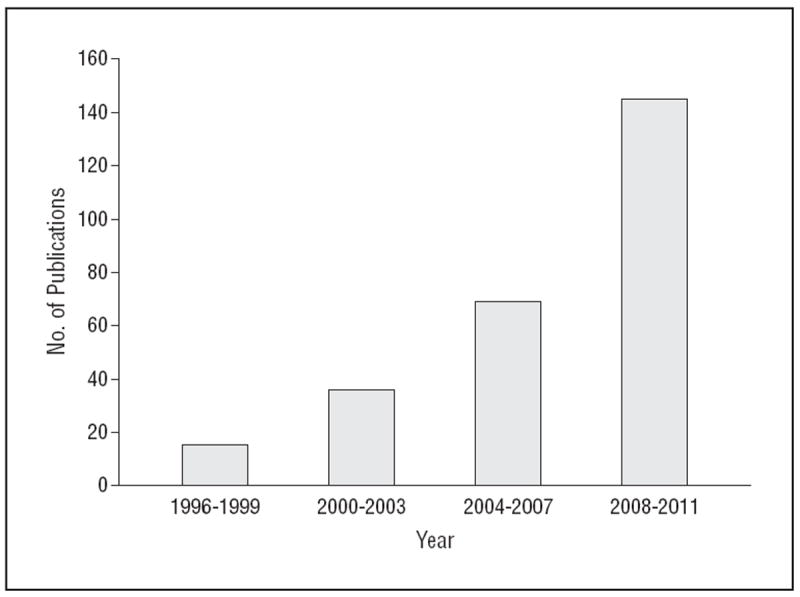

The investigation by Shulman et al adds to the growing body of literature demonstrating the value of exercise in PD (Figure).2 In 2001, the Cochrane Collaboration examined randomized controlled trials that compared physiotherapy to placebo, and only 11 trials were eligible for their systematic review. At that time, authors concluded that there was “insufficient evidence to support or refute the efficacy of physiotherapy in Parkinson’s disease.”3 By 2012, the evidence had increased, and Cochrane’s updated review included 33 trials and discussed 6 additional ongoing studies.4 Using these new data, the authors concluded that while differences between physiotherapy and placebo groups in motor performance and other measures were small, they would be clinically meaningful to patients. The Table highlights the results of select randomized controlled trials from recent reviews4-12 or that were conducted. While the investigation by Shulman et al certainly stands out in its rigorous method and large patient participation, each study demonstrates the importance of exercise in improving the health and well-being of individuals with PD.

Figure.

Publications of randomized controlled trials of exercise and Parkinson disease, 1996-2011. Databased on a MEDLINE search of Parkinson disease, Parkinson, or Parkinson’s and exercise conducted on August 21, 2012. The search was restricted to randomized controlled trials using a standardized search strategy from the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions.2

Table. Select Randomized Controlled Trials of Exercise as Treatment for Symptoms of Parkinson Disease.

| Source | Funder | Intervention | No. | Primary Outcomes | Primary Conclusion |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Shulman et al,1 2012 | Michael J. Fox Foundation | High-or low-intensity treadmill or stretching and resistance training | 67 | Gait speed | High-or low-intensity treadmill and stretching and resistance improves gait speed |

| Li et al,5 2012 | National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke | Tai chi, resistance training, or stretching | 195 | Balance testing | Tai chi improves balance |

| Ashburn et al,6 2007 | Action Medical Research, John and Lucille Van Geest Foundation | Home physiotherapy | 142 | Falling rates | Physiotherapy had a trend toward a reduction in falls |

| Schmitz-Hübsch et al,7 2006 | German Parkinson patients’ organization (dPV) | Qigong | 56 | UPDRS | Qigong improved UPDRS scores |

| Ellis et al,8 2005 | Not reported | Physiotherapy and medication | 68 | Health questionnaire including mobility subscale | Physiotherapy improves mobility subscale of health questionnaire |

| Protas et al,9 2005 | Veteran Affairs | Gait training | 18 | Gait parameters and reports of falls | Gait training improves gait and balance and reduced falls |

| Hirsch et al,10 2003 | Not reported | Balance and resistance training or balance training alone | 15 | Balance and muscle strength | Balance and resistance training improves balance and strength |

| Schenkman et al,11 1998 | National Institute of Health, Claude D. Pepper Older Americans Independence Center, National Center for Research Resources | Relaxation with muscle activation | 51 | Spinal flexibility and physical performance | Relaxation, muscle activation improves flexibility, physical performance |

Abbreviation: UPDRS, Unified Parkinson Disease Rating Scale.

Beyond its benefits on physical health, exercise gives patients amore active role in the management of their PD. Patients are thirsting for such a role, which is consistent with a patient-centered care model in which health care is “closely congruent with and responsive to patients’ wants, needs, and preferences.”13(p152) Patients with PD specifically want more information about nonpharmacological interventions and are not satisfied with the information that they receive.14 The study by Shulman et al provides physicians and patients with evidence about what patients can do to improve and take charge of their health.

In 2001, the Institute of Medicine raised patientcentered care to a national priority by identifying patientcentered care as 1 of 6 core needs for health care.15 The Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act of 201016 took patient-centered care to a research and funding level by creating the Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute. In a 2012 JAMA article, the directors of the newly created Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute emphasized the importance of the patient in assessing health care options, saying, “Engagement of patients at every step of the research process is viewed as essential, including in the selection of research questions, study design, conduct, analysis, and implementation of findings.”17(p1636)

The study by Shulman et al directly engages patients in research and in their health. Exercise programs among those with neurological disorders increase the patients’ sense of self-efficacy,18 their sense of involvement in their care and overall belief in their abilities to perform certain activities. In addition, patient involvement leads to higher satisfaction with care, and greater likelihood of following provider recommendations.19 In essence, exercise puts the patient—not a pill—at the center of care, which is exactly where patients want and ought to be.

Acknowledgments

Conflict of Interest Disclosures: Dr Dorsey is a consultant to Lundbeck and Medtronic and receives research support from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, Lundbeck, and Prana Biotechnology. Dr Rosenthal receives research support from clinical research training grant 5KL2RR025006-05.

References

- 1.Shulman LM, Katzel LI, Ivey FM, et al. Randomized clinical trial of 3 types of physical exercise for patients with Parkinson disease. JAMA Neurol. 2013;70(2):183–190. doi: 10.1001/jamaneurol.2013.646. published online November 5, 2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lefebvre C, Manheimer E, Glanville J. Chapter 6: Searching for studies. Higgins JP, Green S, editors. The Cochrane Collaboration. [September 2, 2012];Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions Version 5.1.0 (updated March 2011) 2011 http://www.cochrane-handbook.org.

- 3.Deane KH, Jones D, Playford ED, Ben-Shlomo Y, Clarke CE. Physiotherapy for patients with Parkinson’s disease: a comparison of techniques. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2001;(3) doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD002817. CD002817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tomlinson CL, Patel S, Meek C, et al. Physiotherapy vs placebo or no intervention in Parkinson’s disease. CochraneDatabase of System Rev. 2012;(8) doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD002817.pub3. CD002817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Li F, Harmer P, Fitzgerald K, et al. Tai chi and postural stability in patients with Parkinson’s disease. N Engl J Med. 2012;366(6):511–519. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1107911. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ashburn A, Fazakarley L, Ballinger C, Pickering R, McLellan LD, Fitton C. A randomised controlled trial of a home-based exercise programme to reduce the risk of falling among people with Parkinson’s disease. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2007;78(7):678–684. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.2006.099333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Schmitz-Hübsch T, Pyfer D, Kielwein K, Fimmers R, Klockgether T, Wüllner U. Qigong exercise for the symptoms of Parkinson’s disease: a randomized, controlled pilot study. Mov Disord. 2006;21(4):543–548. doi: 10.1002/mds.20705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ellis T, de Goede CJ, Feldman RG, Wolters EC, Kwakkel G, Wagenaar RC. Efficacy of a physical therapy program in patients with Parkinson’s disease: a randomized controlled trial. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2005;86(4):626–632. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2004.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Protas EJ, Mitchell K, Williams A, Qureshy H, Caroline K, Lai EC. Gait and step training to reduce falls in Parkinson’s disease. NeuroRehabilitation. 2005;20(3):183–190. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hirsch MA, Toole T, Maitland CG, Rider RA. The effects of balance training and high-intensity resistance training on persons with idiopathic Parkinson’s disease. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2003;84(8):1109–1117. doi: 10.1016/s0003-9993(03)00046-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Schenkman M, Cutson TM, Kuchibhatla M, et al. Exercise to improve spinal flexibility and function for people with Parkinson’s disease: a randomized, controlled trial. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1998;46(10):1207–1216. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1998.tb04535.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Goodwin VA, Richards SH, Taylor RS, Taylor AH, Campbell JL. The effectiveness of exercise interventions for people with Parkinson’s disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Mov Disord. 2008;23(5):631–640. doi: 10.1002/mds.21922. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Laine C, Davidoff F. Patient-centered medicine. A professional evolution. JAMA. 1996;275(2):152–156. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dorsey ER, Voss TS, Shprecher DR, et al. A U.S. survey of patients with Parkinson’s disease: satisfaction with medical care and support groups. Mov Disord. 2010;25(13):2128–2135. doi: 10.1002/mds.23160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Committee on Quality of Health Care in America and the Institute of Medicine. Crossing the quality chasm: a new health system for the 21st century. [August 28, 2012]; http://www.iom.edu/~/media/Files/Report%20Files/2001/Crossing-the-Quality-Chasm/Quality%20Chasm%202001%20%20report%20brief.pdf.

- 16.Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act, Pub L No. 111-148, 124 Stat 727, §6301.

- 17.Methodology Committee of the Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute (PCORI) Methodological standards and patient-centeredness in comparative effectiveness research: the PCORI perspective. JAMA. 2012;307(15):1636–1640. doi: 10.1001/jama.2012.466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Grosset KA, Grosset DG. Patient-perceived involvement and satisfaction in Parkinson’s disease: effect on therapy decisions and quality of life. Mov Disord. 2005;20(5):616–619. doi: 10.1002/mds.20393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Haworth J, Young C, Thornton E. The effects of an “exercise and education” programme on exercise self-efficacy and levels of independent activity in adults with acquired neurological pathologies: an exploratory, randomized study. Clin Rehabil. 2009;23(4):371–383. doi: 10.1177/0269215508101728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]